1. Introduction

Osteoarthritis (OA) is a degenerative joint disorder and a leading cause of disability world-wide [

1], which poses a growing health burden due to aging populations and rising obesity rates [

2]. Unfortunately, current treatment options are inadequate with no approved disease-modifying pharmacological drugs, and generic analgesics that exhibit limited efficacy and significant adverse side effects when taken chronically. Improved understanding of the molecular and cellular mechanisms that mediate OA is therefore a necessity so that more efficacious and targeted interventions can be developed to improve patients’ quality of life.

In attempting to develop new therapeutics it is now recognised that OA is a complex heterogeneous condition involving multiple tissues of the joint, including articular cartilage degradation, remodelling of the subchondral bone, and synovial inflammation [

3,

4]. Emerging perspectives suggest that this heterogeneity is underpinned by distinct molecular endotypes [

5,

6], including “low repair”, “bone-cartilage”, “metabolic” and “inflammatory” sub-types. Amongst these, the inflammatory sub-type, which is characterised by significant synovial fluid inflammation, is of particular interest due to the potential for synovial inflammation to exacerbate cartilage degeneration and to promote joint pain

via the sensitisation of peripheral nociceptors [

7]. Therefore, better understanding of the cross-cellular molecular signalling pathways that mediate and propagate the effects of synovial inflammation within the joint may provide the rationale for the development of novel targeted anti-inflammatory drugs in specific OA populations exhibiting an inflammatory endotype.

To this end, extracellular vesicles (EVs), which are small, lipid membrane-bound particles released by nearly all cell types into the extracellular environment, have emerged as novel candidate mediators of cellular cross-talk in OA. Classified by their size, EVs include exosomes, microvesicles, and apoptotic bodies, and are capable of transporting bioactive molecules including proteins, lipids, and nucleic acids to recipient cells, influencing various biological processes [

8]. In the context of OA, EVs have been implicated in disease pathogenesis, mediating cartilage degradation, inflammation and nociception [

9,

10,

11,

12].

Asghar et al. (2024) [

13] demonstrated that synovial fibroblast EVs contain distinct miRNA profiles, which contribute to chondrocyte damage. Furthermore, Cao et al. (2024) [

10] revealed that EVs from the infrapatellar fat pad in OA patients impair cartilage metabolism and induce senescence. Distler et al. (2005) [

14] showed that EVs contain OA-relevant proteases, including matrixmetalloproteases (MMPs) that promote cartilage degradation, and pro-inflammatory cytokines including IL-1β, and TNFα, which induce cartilage degeneration and are associated with peripheral pain sensitisation.

However, despite these insights the characterisation of EVs that are present in OA synovial fluid and their role in mediating OA joint pathology remains poorly understood. This study had two main objectives. First, to comprehensively characterise synovial fluid extracellular vesicles (SFEVs) from patients with knee OA across different severity levels. Second, to investigate the functional effects of SFEVs derived from patients with severe or mild/moderate OA on the phenotype of articular chondrocytes, aiming to uncover novel mechanisms of SFEV-mediated communication within the OA joint.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Patient Recruitment and Sample Collection

Articular cartilage and synovial joint fluid were collected from OA patients undergoing joint surgery (NRES 17/SS/0456) at the Royal Orthopaedic Hospital, Birmingham (United Kingdom) and Russell’s Hall Hospital, Dudley (United Kingdom). Patients completed Oxford Knee Score (OKS), a visual analogue scale (VAS) of pain severity and EQ5D questionnaires to capture OA joint severity and quality of life.

2.2. Isolation and Culture of Primary Human OA Chondrocytes

Fresh cartilage was dissected into 1-3mm3 pieces, and digested using 2mg/ml collagenase (Merck, C9891) in DMEM (Merck, D6429) for 5-15 hours at 37˚C. Digested cartilage was filtered through a 70µm cell strainer, the resultant filtrate centrifuged at 400 g for 5 min, and then resuspended and cultured in chondrocyte growth media (DMEM, 10% FCS, 1% NEAA, 2 mM L-glutamine (ThermoFisher Scientific, Gloucester, UK, 25030024), 1% penicillin and streptomycin (100 U/mL penicillin and 100µg/mL streptomycin) (Merck, P4333), 2.5ug/ml amphotericin B (Merck, A2942)). Growth media was replaced every 3–4 days and cells were passaged upon reaching 70% confluency.

2.3. Synovial Fluid EV Isolation and Characterisation

Synovial fluid was mixed with 1mg/ml hyaluronidase (Merck, H3506) in PBS at 1:11, vortexed gently for 3 min and incubated at 37˚C for 30 min. The hyaluronidase treated synovial fluid was then centrifuged at 10,000 g for 10 min, and the supernatant ultracentrifuged at 100,000 g for 16 h to pellet EVs [

15], which were resuspended in PBS.

EVs from synovial fluid (n = 13 patients) were analysed by Nanoparticle Tracking Analysis using the NSPro (Malvern Panalytical, Malvern, United Kingdom) to determine size and concentration. Samples were diluted PBS (Merck, D8537). Optimal dilutions were determined via NanoSight NS Xplorer software utilising the software’s automated detection threshold and focus. Five videos capturing 400 tracks were taken of each sample at 25˚C with a syringe pump speed of 3μl/min.

EVs were further characterised using the ExoView R100 reader (Unchained Labs, Malvern, United Kingdom) to analyse size, concentration, and CD9, CD63 and CD81 tetraspanin markers using the Leprechaun Exosome Human Plasma Kits (251-1045, Unchained Labs, Malvern, United Kingdom), as previously described [

16]. Chips were imaged using the ExoView R100 reader using ExoViewer 3.14 software and analysed using ExoView Analyser 3.0. Fluorescence gating was based on mouse IgG capture control and sizing thresholds were set from a diameter of 50 to 200 nm.

2.4. RNA Isolation and Bulk RNA Sequencing

Total RNA was extracted using a RNeasy Mini kit according to manufacturer’s instructions (Qiagen). RNA quantity and purity was determined by Nanodrop One (ThermoFisher); all isolated RNA samples had A260/A280 ratios of 1.8-2.0. Library preparation and RNA-sequencing were performed by Beijing Genomics Institute (Hong Kong) using the DNBSEQ platform. Reads were mapped to the hg38 reference human genome using Bowtie. Differentially expressed genes (DEGs) were identified through DESEQ analysis and results analysed further by Ingenuity Pathway Analysis (IPA).

2.5. Luminex and ELISA

The concentrations of MMP1, MMP3, MMP13, BDNF, IL-6 and NGF proteins in conditioned media, synovial fluid or SFEV lysates were quantified using a customised Luminex assay (Bio-Techne, United States), whilst TIMP3 and ICAM1 were quantified by ELISA (TIMP3: A717-96, antibodies.com; ICAM1: A1716-96, antibodies.com). Prior to protein quantification, hyaluronidase-treated synovial fluid samples and isolated SFEVs were lysed with 0.5% TritonX, and diluted 1:2 with dilution buffer.

2.6. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism v10, with p-values of <0.05 considered to be statistically significant, and FDR <0.05 considered significant when analysing RNA sequencing data. Where appropriate, linear regressions were performed to test associations between variables. Two-way ANOVA was performed on ExoView data with Bonferroni post-hoc tests to determine statistical significance between severe OA and mild/moderate OA tetraspanin expression. One-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparison post-hoc tests were performed on RNA sequencing count data and Luminex/ELISA data.

4. Discussion

This study provides evidence for a functional relationship between the characteristics of synovial fluid EVs (SFEVs), chondrocyte phenotype and OA severity. For the first time, we demonstrate that size, concentration and tetraspanin marker expression of SFEVs is related to OA severity. Furthermore, we demonstrate that SFEVs from severe OA patients drive a distinct catabolic inflammatory articular chondrocyte phenotype.

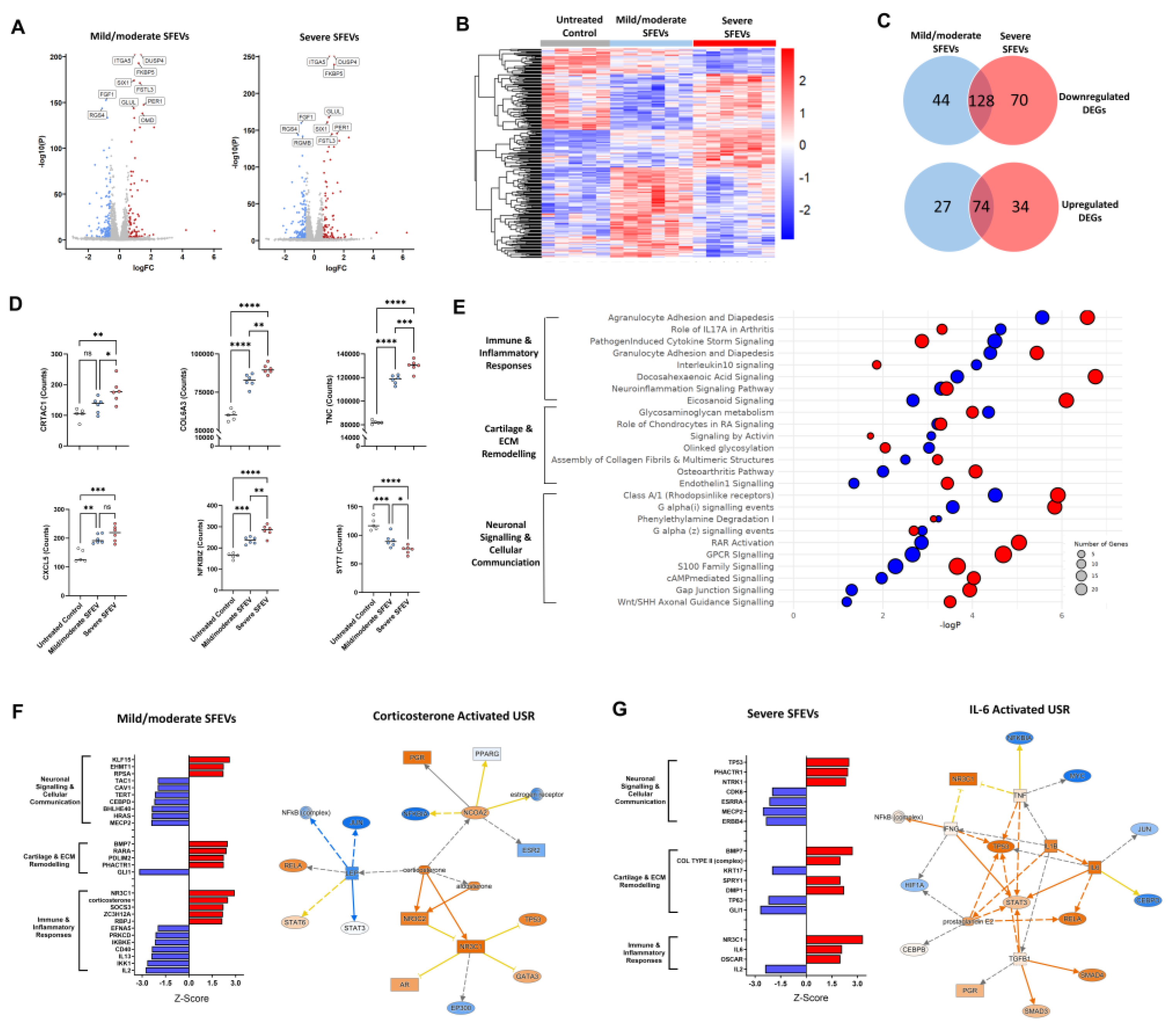

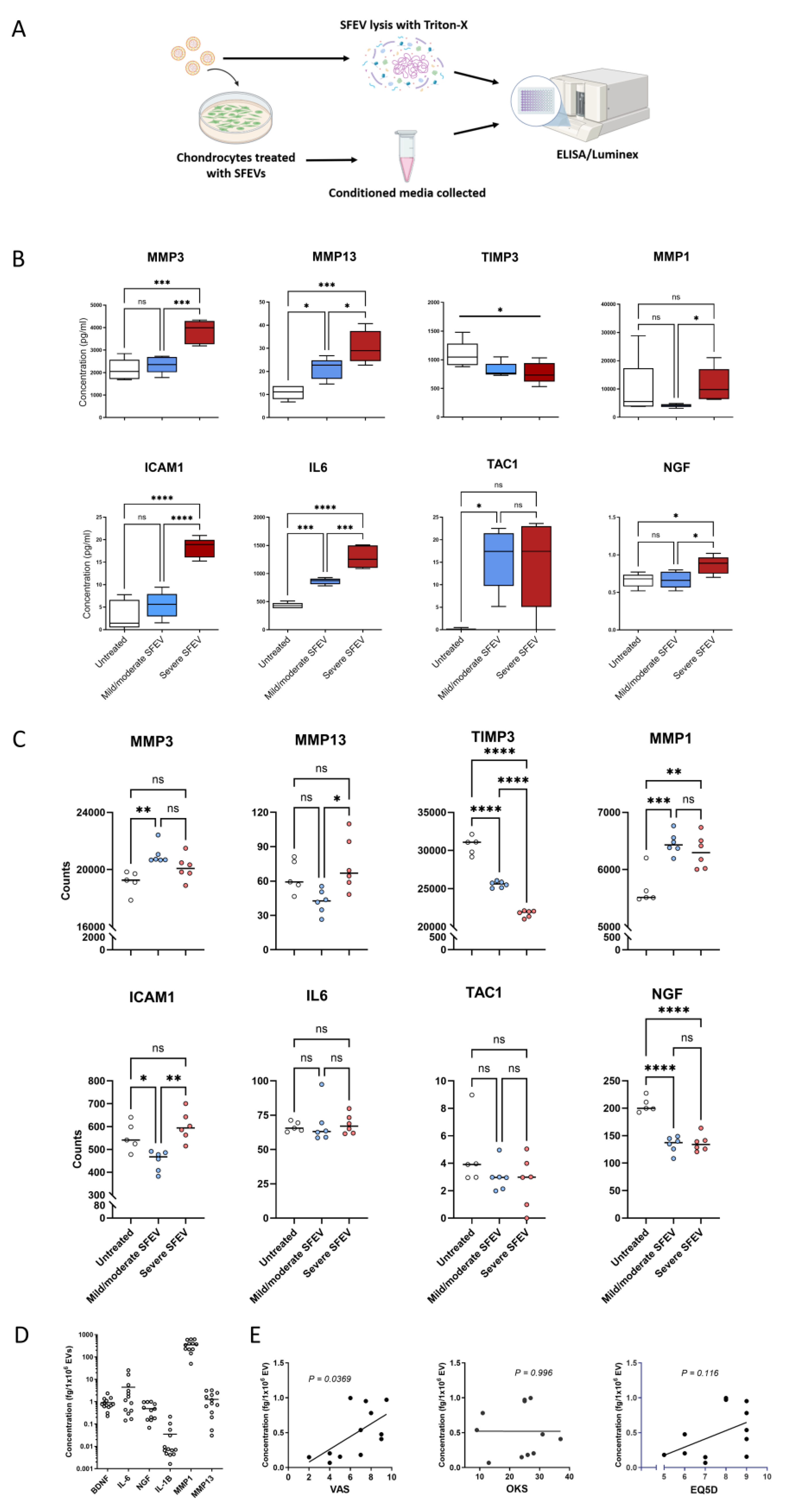

Synovial inflammation in OA is considered a driver of both cartilage degeneration and pain sensitisation. Therefore, our finding that SFEVs can promote the expression and release not only of cartilage catabolic mediators including CRTAC1, TNC, COL6A3, MMP3 and MMP13 but also pro-inflammatory mediators such as TAC1 (Substance P), CXCL5 and IL-6 in articular chondrocytes suggests that SFEVs may contribute to both cartilage degeneration and pain sensitisation in the joint. Notably, the induction of many of these pro-catabolic and pro-inflammatory effects was significantly greater in chondrocytes subjected to SFEVs from more severe OA, compared to SFEVs from mild/moderate OA, aligning with the previous study by Zhang et al. (2023) [

17], who reported that EVs in severe OA contain pro-inflammatory cytokines that exacerbate joint damage. Furthermore, potentially compounding the pro-catabolic effect of SFEV-induced MMPs on cartilage, we also found that SFEVs reduced the expression of the tissue inhibitor of MMPs, TIMP3. Reduced TIMP3 expression may lead to unchecked MMP activity, tipping the balance towards cartilage matrix degradation.

In addition to the induction of these well-established pro-inflammatory catabolic mediators, pathway analysis of the RNA sequencing transcriptomic data revealed that SFEVs modulated a number of canonical inflammatory signalling pathways that regulate immune and inflammatory responses, cartilage and ECM remodelling and neuronal signalling. For example, chondrocytes subjected to SFEVs exhibited increased expression of DUSP4, which is a known regulator of MAPK inflammatory signalling in chondrocytes [

18], and ITGA5, a receptor for fibronectin, supporting the potential for SFEVs to shape the inflammatory joint microenvironment. Recently, ITGA5+ synovial fibroblasts were shown to exacerbate inflammatory joint pathology in a collagen-induced arthritis model [

19].

We also found that SFEVs mediated transcriptional changes in several genes that mediate vascular biology. Importantly, angiogenesis is a hallmark of OA progression, driven by chronic inflammation and oxidative stress [

20,

21]. Unlike healthy cartilage, which is avascular, OA cartilage undergoes aberrant neovascularization [

20], a process facilitated by the induction of pro-angiogenic factors such as VEGF [

22,

23] and ICAM1, which is induced in chondrocytes by IL-1β and found in areas of damaged cartilage [

24]. The presence of new vasculature is thought to exacerbate inflammation and pain by supplying nutrients and inflammatory mediators to the joint. Here, we observed no change in expression of VEGF with SFEVs from either mild/moderate OA or severe OA. However, SFEVs from severe OA patients induced increased expression of ANGPTL7, SOD2 and increased expression and secretion of ICAM1 in articular chondrocytes. ANGPTL7, a member of the angiopoietin-like family, promotes angiogenesis. Previously, it was reported that the expression of ANGPTL7 in the joint is induced by mechanical stimuli, whilst functionally its over-expression promotes chondrocytes proliferation and calcification [

25]. SOD2 is an antioxidant enzyme that regulates reactive oxygen species (ROS) production [

26], which is a known to promote angiogenic and inflammatory signalling [

27,

28]. Interestingly, ablation of SOD2 in models of mechanical joint loading promoted cartilage degeneration, and its expression, similarly to other superoxide dismutases (e.g., SOD1 and SOD3) is downregulated in human OA cartilage [

29,

30] and decreased during disease progression in a spontaneous OA animal model [

29]. Notably, previous studies have reported that EVs can transport pro-angiogenic factors [

31], supporting the potential role of SFEV in actively contributing to neovascularization in, and our findings here would support that concept.

Increasing evidence suggests that peripheral pain sensitisation in OA is associated with synovitis [

7,

32,

33] and, in part mediated by the interactions between chondrocytes, immune cells and synovial fibroblasts within the synovial tissue [

7], leading to the production of cytokines and growth factors that are capable of sensitising nociceptors directly or activating neuronal signalling pathways [

34,

35,

36].

Notably, we found that the secretion of NGF protein was significantly increased in chondrocytes stimulated with SFEVs from patients with severe OA. Furthermore, TAC1 (Substance P) secretion was increased approximately 18-fold in chondrocytes exposed to SFEVs from either mild/moderate or severe OA. NGF is a well-established mediator of OA pain, which

via binding to TrkA, sensitizes peripheral nociceptors, promotes sprouting, and drives chronic pain states within the joint [

37]. Indeed, NGF inhibition has been shown to significantly reduce pain in OA models and in clinical trials [

38,

39]. Similarly, Substance P, a neuropeptide encoded by TAC1, plays a pivotal role in neurogenic inflammation and pain signalling by activating neurokinin-1 (NK1) receptors on sensory afferent neurons [

40]. It has been detected at elevated levels in OA synovial fluid [

41], NK1-receptor antagonists have shown analgesic efficacy in rodent models of arthritis [

42], and TAC1 SNPs are associated with symptomatic knee OA pain [

43]. Thus, together, these findings suggest that SFEVs within the OA joint may contribute to the establishment and amplification of pain signalling networks in cartilage through the induction of NGF and Substance P.

Collectively, SFEVs from severe OA patients elicited more pronounced effects on chondrocytes than SFEVs from patients with mild/moderate OA. Indeed, upstream regulator analysis revealed a striking divergence in the predicted upstream mediators of SFEV action depending on OA severity. The chondrocyte transcriptome induced by SFEVs from mild/moderate OA patients was associated with the upstream activation of corticosterone, a potent anti-inflammatory mediator, suggesting that in less severe disease, SFEVs may help maintain a homeostatic balance, supporting both anabolic and anti-inflammatory responses in chondrocytes. This contrasts with SFEVs from severe OA patients, where IL-6, a well-known pro-inflammatory cytokine, emerged as a key activated upstream regulator of the chondrocyte transcriptome, aligning with the broader pro-inflammatory and catabolic gene and protein expression profiles we observed.

Together, these data suggest that in healthy or mildly affected joints, SFEVs might play a regulatory role, modulating chondrocyte responses in a way that resembles the homeostatic functions of healthy synovial fluid. However, as OA progresses to a severe stage, this balance appears to be shifted towards promoting inflammation and matrix degradation, potentially exacerbating cartilage degeneration and pain. However, it should be noted that these effects were markedly different to the effect of synovial fluid on chondrocytes. Suggesting therefore that although SFEVs likely contribute to driving inflammation and cartilage degeneration, additional non-EV encapsulated synovial fluid factors have a predominant effect on chondrocytes. To this end, it would have been invaluable to include an EV-depleted synovial fluid control to account for the effects of other components in the fluid. However, at present, no reliable methods exist for efficient EV depletion from synovial fluid.

Further supporting the role of SFEVs as active mediators of OA pathology, targeted protein analysis revealed that key catabolic (MMP1, MMP3, MMP13) and neurotrophic (NGF, BDNF) factors were detectable within SFEV lysates following detergent lysis. Notably, NGF and MMP1 were significantly enriched in SFEVs compared to whole synovial fluid, suggesting that these factors may be selectively packaged into EVs rather than freely circulating in the synovial fluid joint environment. This targeted enrichment highlights a potential role for SFEVs in the direct delivery of pro-catabolic and neuro-inflammatory signals to chondrocytes and other joint-resident cells, which may help explain their strong functional effects. Moreover, the observed positive correlation between SFEV NGF concentration and patient-reported pain severity (VAS scores) provides further evidence that SFEVs may contribute to peripheral pain sensitisation in OA. Given that NGF plays a key role in OA pain via sensitization of nociceptive neurons, these findings raise the intriguing possibility that SFEVs serve as vehicles for nociceptive signalling, actively influencing pain perception in severe OA.

Several limitations should be considered in this study. First, the isolation method used for EVs from synovial fluid was ultracentrifugation, which, although widely used, may not be ideal as it can co-precipitate other molecules, such as lipids. This is a common issue with many EV isolation techniques, and while it could affect the purity of the EV fraction, ultracentrifugation remains one of the most effective methods currently available. Another limitation is that our study did not fully profile EV cargo such as RNAs or protein, since the volume of synovial fluid limited this possibility. Previous studies have reported that EVs from both the infrapatellar fat pad [

11] and synovial fluid [

17] in OA patients, particularly those with advanced disease, contain a higher concentration of pro-inflammatory cargo. Therefore, such analyses, together with EV surface marker expression, could lead to the identification of candidate signatures as biomarkers of OA severity or help to stratify OA patient molecular endotype, as well as provide more mechanistic understanding of the EV mediated functional effects on articular chondrocytes reported here. Finally, the relatively small sample size in this study, a consequence of using human samples, is an inherent limitation. Future studies with larger sample sizes would be beneficial to confirm and extend these findings.

Figure 1.

(A) Stratification of patients into “mild/moderate OA” and “severe OA” groups based on linear regression analysis between EQ5D and Oxford Knee Score (OKS) (p < 0.0001, r² = 0.3287). (B) Schematic of the experimental workflow. Synovial fluid was collected from patients with severe OA or mild/moderate OA, and extracellular vesicles (EVs) were isolated by ultracentrifugation. EVs were characterised using Nanoparticle Tracking Analysis (NTA) and ExoView. (C) Histogram showing size distribution of synovial fluid extracellular vesicles (SFEVs) isolated by centrifugation, as measured by NTA (n = 13). (D) Linear regression analysis of EV concentration (particles/ml) measured by NTA with EQ5D, OKS and VAS patient-reported scores (n=13 patients). (E) Linear regression of SFEV mean particle size measured by NTA with EQ5D, OKS and VAS scores (n=13 patients). (F) Representative ExoView image of SFEVs. Tetraspanin markers are CD9 (blue), CD63 (red), and CD81 (green). (G) Two-way ANOVA analysis of tetraspanin expression (CD9, CD63, CD81) on SFEVs from severe OA and mild/moderate OA patients, as measured by ExoView (p = 0.004, n=13).

Figure 1.

(A) Stratification of patients into “mild/moderate OA” and “severe OA” groups based on linear regression analysis between EQ5D and Oxford Knee Score (OKS) (p < 0.0001, r² = 0.3287). (B) Schematic of the experimental workflow. Synovial fluid was collected from patients with severe OA or mild/moderate OA, and extracellular vesicles (EVs) were isolated by ultracentrifugation. EVs were characterised using Nanoparticle Tracking Analysis (NTA) and ExoView. (C) Histogram showing size distribution of synovial fluid extracellular vesicles (SFEVs) isolated by centrifugation, as measured by NTA (n = 13). (D) Linear regression analysis of EV concentration (particles/ml) measured by NTA with EQ5D, OKS and VAS patient-reported scores (n=13 patients). (E) Linear regression of SFEV mean particle size measured by NTA with EQ5D, OKS and VAS scores (n=13 patients). (F) Representative ExoView image of SFEVs. Tetraspanin markers are CD9 (blue), CD63 (red), and CD81 (green). (G) Two-way ANOVA analysis of tetraspanin expression (CD9, CD63, CD81) on SFEVs from severe OA and mild/moderate OA patients, as measured by ExoView (p = 0.004, n=13).

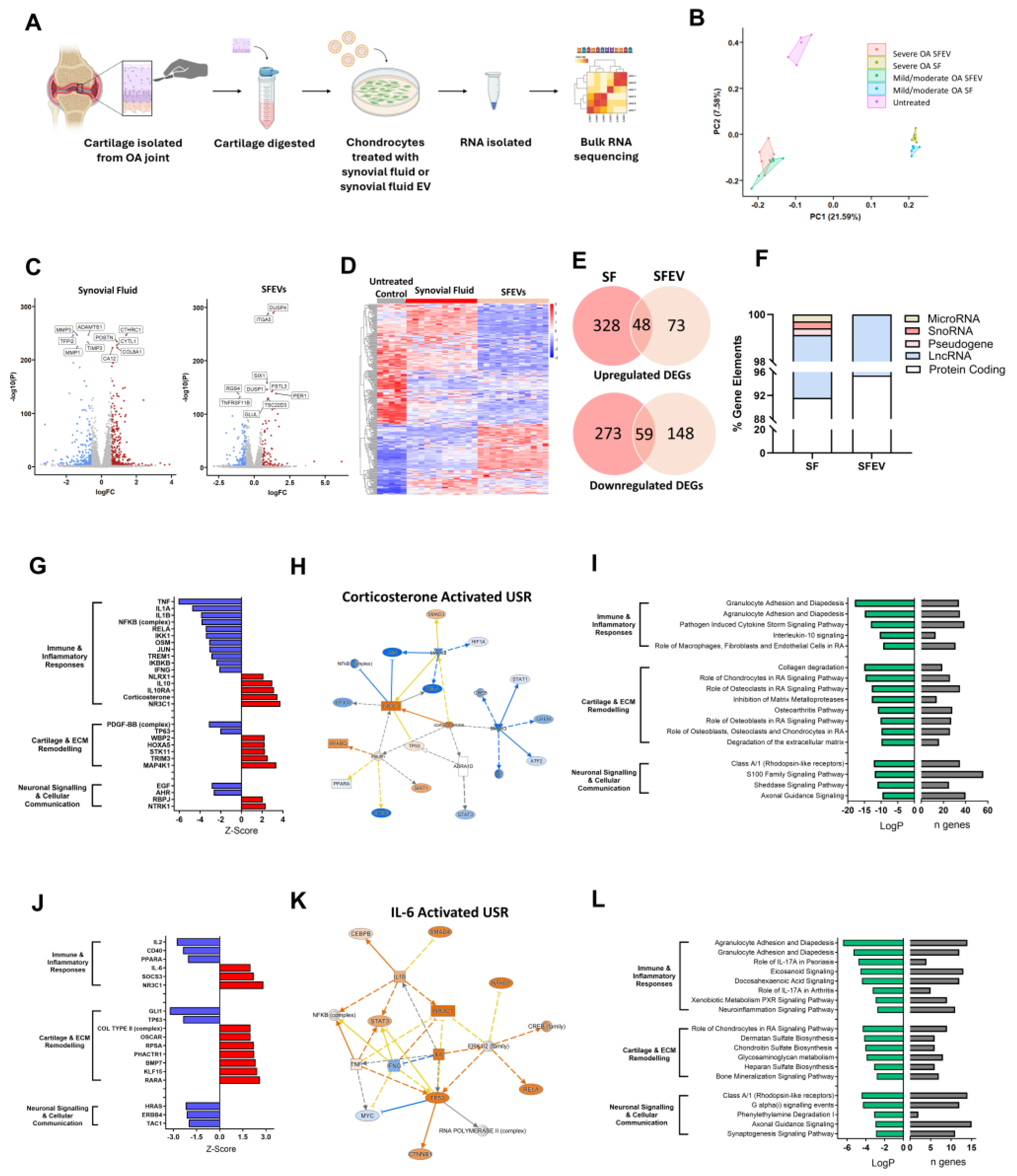

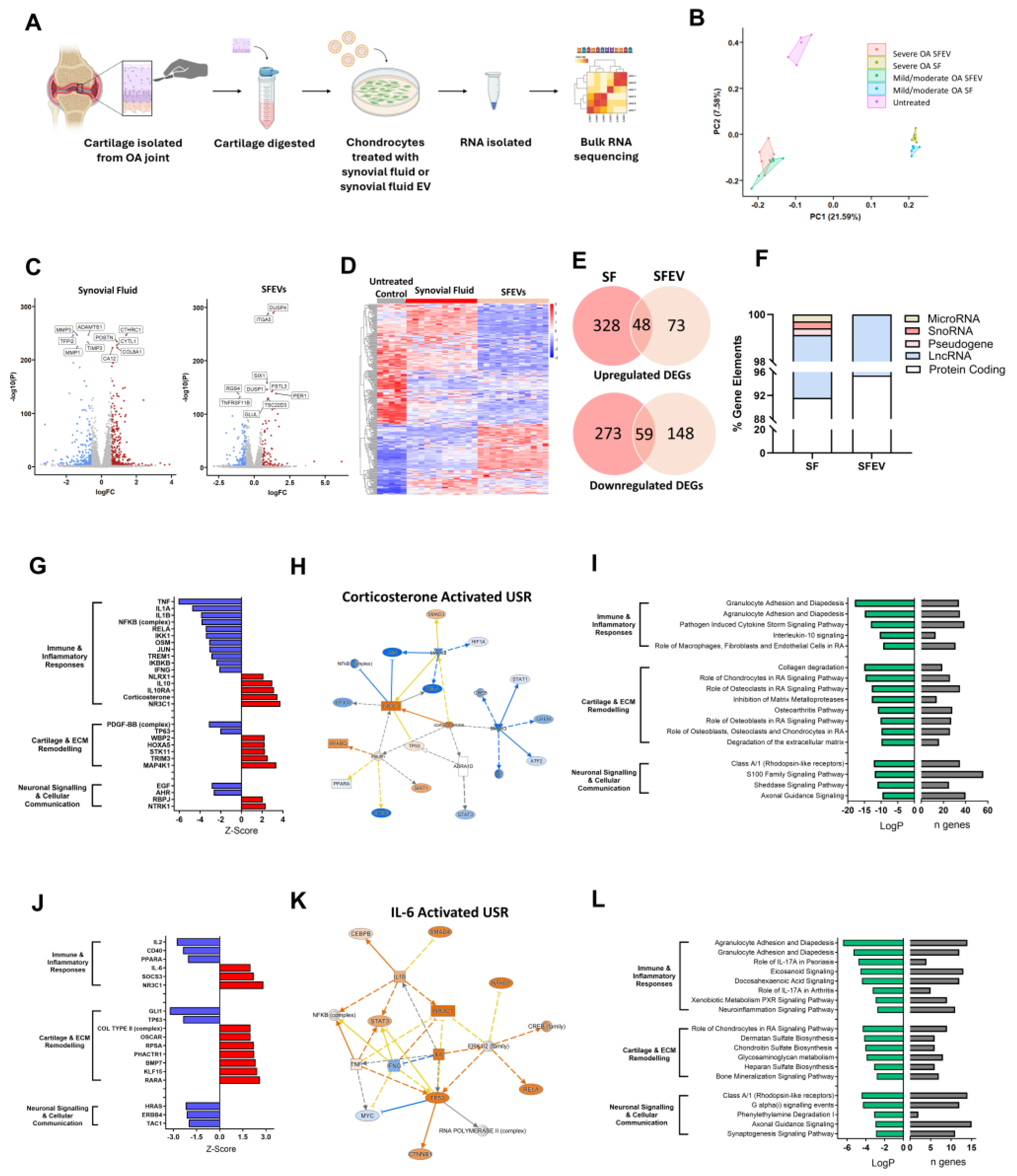

Figure 2.

(A) Schematic of the experimental workflow. Cartilage from OA patients was collagenase digested. Isolated primary chondrocytes were cultured for 24h in the presence of either synovial fluid (SF) or isolated SFEVs (n=6) from the same patients, or left untreated. Total RNA was extracted and subjected to bulk RNA sequencing. (B) Principal Component Analysis (PCA) plot demonstrating distinct clustering of samples following RNA sequencing. (C) Volcano plots highlighting DEGs (FDR < 0.05, FC > 1.5) in SF-treated vs. untreated and SFEV-treated vs. untreated chondrocytes. (D) Heatmap displaying the differential chondrocyte n between SF-treated and SFEV-treated and untreated chondrocytes. (E) Venn diagrams illustrating the common and unique upregulated and downregulated DEGs of SF-treated and SFEV-treated chondrocytes compared to untreated. (F) Percentage distribution of the different gene elements of DEGs identified in SF-treated and SFEV-treated chondrocytes. (G) Z-scores of identified upstream regulators of the transcriptome induced by SF-treated chondrocytes, as identified by IPA. Positive z-scores ≥2 (red bars) represent “activated regulators, negative z-scores ≤-2 (blue bars) represent “inhibited regulators. (H) Molecular network map of the activated upstream regulator corticosterone with connections to DEGs in SF-treated chondrocytes. (I) Top significantly dysregulated canonical signalling pathways in SF-treated chondrocytes as identified by IPA, showing LogP significance and number of DEGs (n) in the dataset aligned to each pathway. (J) Z-scores of identified upstream regulators of the transcriptome induced by SFEV-treated chondrocytes, as identified by IPA. Positive z-scores ≥2 (red bars) represent “activated regulators, negative z-scores ≤-2 (blue bars) represent “inhibited regulators. (K) Molecular network map of the activated upstream regulator IL6 with connections to DEGs in SFEV-treated chondrocytes. (L) Top significantly dysregulated canonical signalling pathways in SFEV-treated chondrocytes as identified by IPA, showing LogP significance and number of DEGs.

Figure 2.

(A) Schematic of the experimental workflow. Cartilage from OA patients was collagenase digested. Isolated primary chondrocytes were cultured for 24h in the presence of either synovial fluid (SF) or isolated SFEVs (n=6) from the same patients, or left untreated. Total RNA was extracted and subjected to bulk RNA sequencing. (B) Principal Component Analysis (PCA) plot demonstrating distinct clustering of samples following RNA sequencing. (C) Volcano plots highlighting DEGs (FDR < 0.05, FC > 1.5) in SF-treated vs. untreated and SFEV-treated vs. untreated chondrocytes. (D) Heatmap displaying the differential chondrocyte n between SF-treated and SFEV-treated and untreated chondrocytes. (E) Venn diagrams illustrating the common and unique upregulated and downregulated DEGs of SF-treated and SFEV-treated chondrocytes compared to untreated. (F) Percentage distribution of the different gene elements of DEGs identified in SF-treated and SFEV-treated chondrocytes. (G) Z-scores of identified upstream regulators of the transcriptome induced by SF-treated chondrocytes, as identified by IPA. Positive z-scores ≥2 (red bars) represent “activated regulators, negative z-scores ≤-2 (blue bars) represent “inhibited regulators. (H) Molecular network map of the activated upstream regulator corticosterone with connections to DEGs in SF-treated chondrocytes. (I) Top significantly dysregulated canonical signalling pathways in SF-treated chondrocytes as identified by IPA, showing LogP significance and number of DEGs (n) in the dataset aligned to each pathway. (J) Z-scores of identified upstream regulators of the transcriptome induced by SFEV-treated chondrocytes, as identified by IPA. Positive z-scores ≥2 (red bars) represent “activated regulators, negative z-scores ≤-2 (blue bars) represent “inhibited regulators. (K) Molecular network map of the activated upstream regulator IL6 with connections to DEGs in SFEV-treated chondrocytes. (L) Top significantly dysregulated canonical signalling pathways in SFEV-treated chondrocytes as identified by IPA, showing LogP significance and number of DEGs.

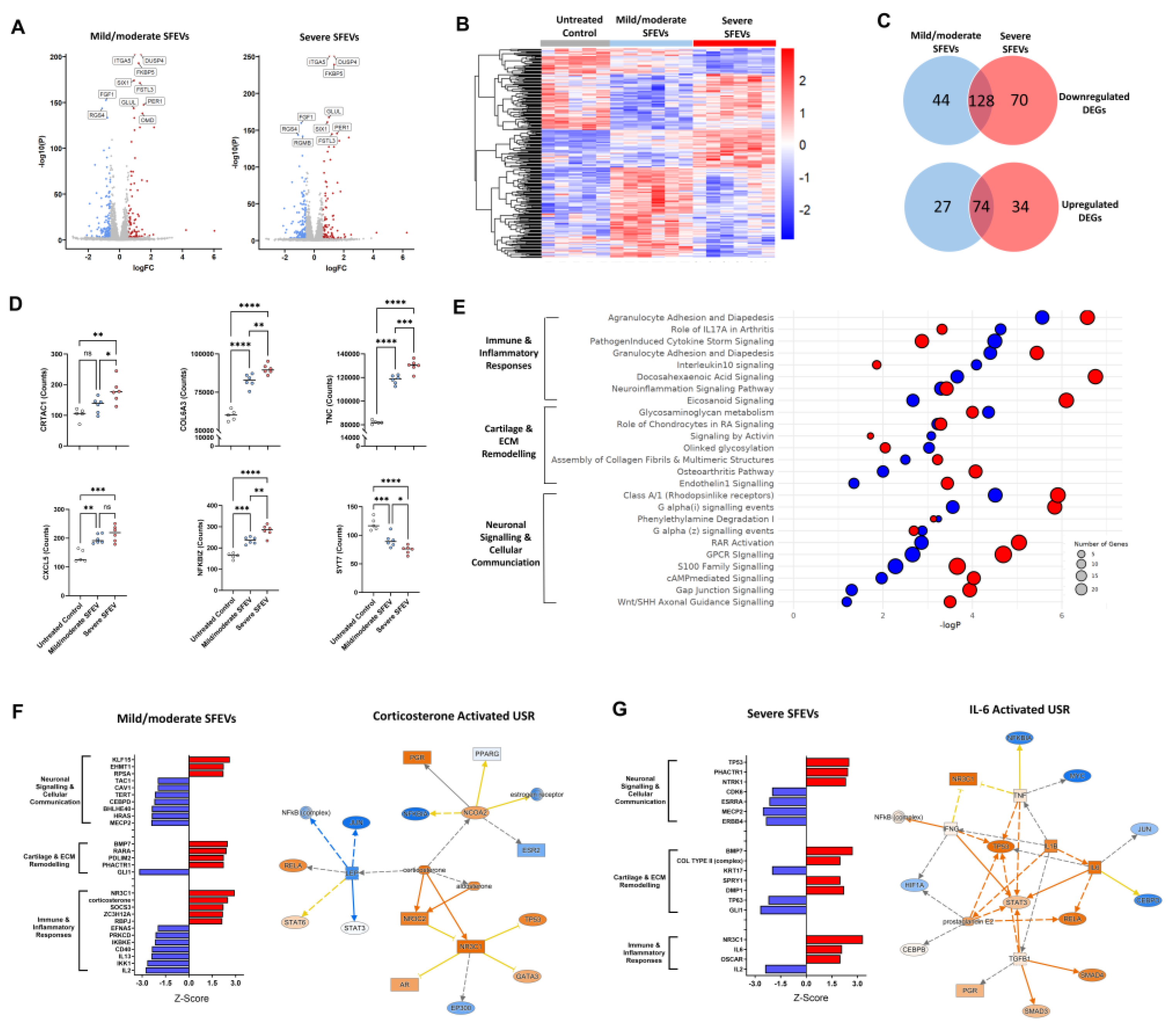

Figure 3.

(A) Volcano plots highlighting DEGs (FDR < 0.05, FC > 1.5) in chondrocytes treated with mild/moderate SFEV vs. untreated and severe SFEV vs. untreated. (B) Heatmap displaying differential transcriptome of untreated, mild/moderate SFEV-treated, and severe SFEV-treated chondrocytes. (C) Venn diagrams illustrating the common and unique upregulated and downregulated DEGs genes of mild/moderate SFEV-treated and severe SFEV-treated chondrocytes. (D) Normalised counts from bulk RNA sequencing for CRTAC1, COL6A3, TNC, CXCL5, NFKBIZ, and SYT7. Data points represent individual sample values for untreated (n=5), mild/moderate SFEV-treated (n=6), and severe SFEV-treated (n=6) conditions, with bar showing mean value. Statistical analysis was performed using 1-way ANOVA with Tukey multiple comparisons post-hoc tests applied (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p <0.0001). (E) Bubble plot of canonical signalling pathway enrichment for the DEGs from mild/moderate SFEV-treated (blue bubbles) and severe SFEV-treated (red bubbles) chondrocytes, with -LogP significance represented on the x-axis and bubble size reflecting the number of DEGs aligned to each pathway. (F) Z-scores of identified upstream regulators of the transcriptome induced by mild/moderate SFEV-treated chondrocytes, as identified by IPA. Positive z-scores ≥2 (red bars) represent “activated regulators, negative z-scores ≤-2 (blue bars) represent “inhibited regulators. Molecular network map shows the activated upstream regulator corticosterone with connections to DEGs in mild/moderate SFEV-treated chondrocytes. (G) Z-scores of identified upstream regulators of the transcriptome induced by severe SFEV-treated chondrocytes, as identified by IPA. Positive z-scores ≥2 (red bars) represent “activated regulators, negative z-scores ≤-2 (blue bars) represent “inhibited regulators. Molecular network map shows the activated upstream regulator IL-6 with connections to DEGs in severe SFEV-treated chondrocytes.

Figure 3.

(A) Volcano plots highlighting DEGs (FDR < 0.05, FC > 1.5) in chondrocytes treated with mild/moderate SFEV vs. untreated and severe SFEV vs. untreated. (B) Heatmap displaying differential transcriptome of untreated, mild/moderate SFEV-treated, and severe SFEV-treated chondrocytes. (C) Venn diagrams illustrating the common and unique upregulated and downregulated DEGs genes of mild/moderate SFEV-treated and severe SFEV-treated chondrocytes. (D) Normalised counts from bulk RNA sequencing for CRTAC1, COL6A3, TNC, CXCL5, NFKBIZ, and SYT7. Data points represent individual sample values for untreated (n=5), mild/moderate SFEV-treated (n=6), and severe SFEV-treated (n=6) conditions, with bar showing mean value. Statistical analysis was performed using 1-way ANOVA with Tukey multiple comparisons post-hoc tests applied (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p <0.0001). (E) Bubble plot of canonical signalling pathway enrichment for the DEGs from mild/moderate SFEV-treated (blue bubbles) and severe SFEV-treated (red bubbles) chondrocytes, with -LogP significance represented on the x-axis and bubble size reflecting the number of DEGs aligned to each pathway. (F) Z-scores of identified upstream regulators of the transcriptome induced by mild/moderate SFEV-treated chondrocytes, as identified by IPA. Positive z-scores ≥2 (red bars) represent “activated regulators, negative z-scores ≤-2 (blue bars) represent “inhibited regulators. Molecular network map shows the activated upstream regulator corticosterone with connections to DEGs in mild/moderate SFEV-treated chondrocytes. (G) Z-scores of identified upstream regulators of the transcriptome induced by severe SFEV-treated chondrocytes, as identified by IPA. Positive z-scores ≥2 (red bars) represent “activated regulators, negative z-scores ≤-2 (blue bars) represent “inhibited regulators. Molecular network map shows the activated upstream regulator IL-6 with connections to DEGs in severe SFEV-treated chondrocytes.

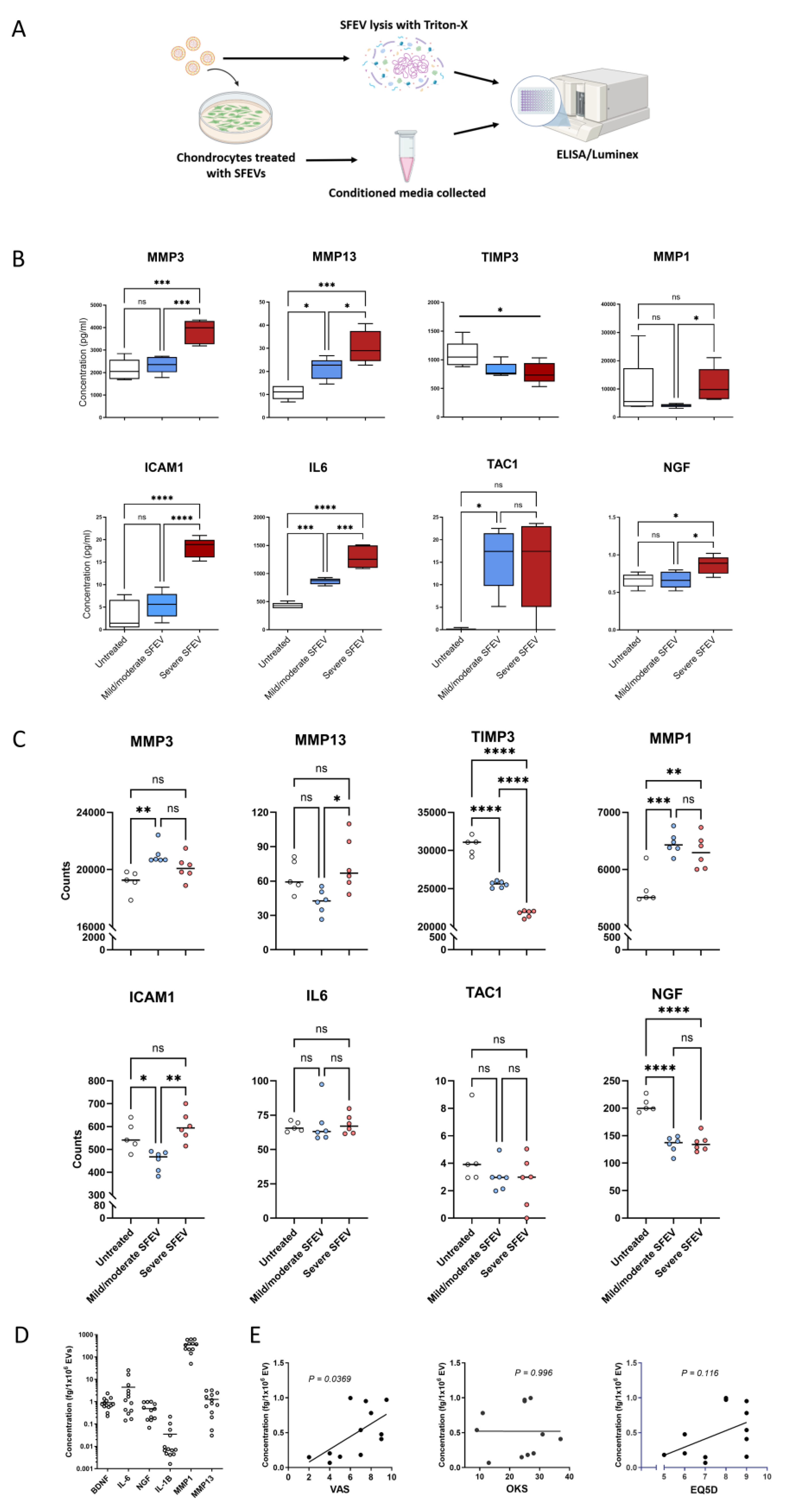

Figure 4.

(A) Schematic of the experimental workflow. Primary human OA chondrocytes, isolated by collagenase digestion of articular cartilage were cultured for 24h with SFEVs from either mild/moderate or severe OA patients, or left untreated. Conditioned media was collected, and protein analyte concentrations quantified using Luminex (MMP1, MMP3, MMP13, IL-6, and NGF) or ELISA (TAC1, TIMP3, and ICAM1). Synovial fluid and SFEVs were lysed with Triton-X and protein analytes were quantified using a customised Luminex (MMP1, MMP3, MMP13, BDNF, NGF, IL-6 and IL-1β). (B) Box and whisker plots showing protein concentrations (pg/ml) of MMP3, MMP13, TIMP3, and MMP1 (cartilage and ECM remodelling response genes), ICAM1 and IL-6 (immune and inflammatory response genes), and TAC1 and NGF (neuronal signalling and cellular communication genes) in untreated (n = 5), mild/moderate SFEV-treated (n = 6), and severe SFEV-treated (n = 6) chondrocytes, as measured by Luminex and ELISA. Boxes represents the interquartile range (IQR; 25th to 75th percentiles), with the line indicating mean and whiskers representing minimum to maximum values. (C) Normalised counts from bulk RNA sequencing for MMP1, MMP3, MMP13, TIMP3, ICAM1, IL6, TAC1, and NGF in untreated (n = 5), mild/moderate SFEV-treated (n = 6), and severe SFEV-treated (n = 6) chondrocytes. Statistical analysis was performed using 1-way ANOVA with Tukey post-hoc multiple comparison tests applied as appropriate. Significance levels: *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001. (D) Scatter plots of the protein concentration (pg/ml) of the analytes BDNF, IL-6, NGF, IL1β, MMP1 and MMP13 in SFEV lysates. The concentration of the analyte MMP3 is not shown as its concentration exceeded the upper limit of the standard curve. (E) Linear regression analysis of SFEV NGF protein concentration with VAS, EQ5D and OKS patient-reported scores (n = 13 patients). NGF protein was quantified by ELISA of SFEVs lysed with 0.5% Triton-X. Data points represent individual sample values, and bars show the mean.

Figure 4.

(A) Schematic of the experimental workflow. Primary human OA chondrocytes, isolated by collagenase digestion of articular cartilage were cultured for 24h with SFEVs from either mild/moderate or severe OA patients, or left untreated. Conditioned media was collected, and protein analyte concentrations quantified using Luminex (MMP1, MMP3, MMP13, IL-6, and NGF) or ELISA (TAC1, TIMP3, and ICAM1). Synovial fluid and SFEVs were lysed with Triton-X and protein analytes were quantified using a customised Luminex (MMP1, MMP3, MMP13, BDNF, NGF, IL-6 and IL-1β). (B) Box and whisker plots showing protein concentrations (pg/ml) of MMP3, MMP13, TIMP3, and MMP1 (cartilage and ECM remodelling response genes), ICAM1 and IL-6 (immune and inflammatory response genes), and TAC1 and NGF (neuronal signalling and cellular communication genes) in untreated (n = 5), mild/moderate SFEV-treated (n = 6), and severe SFEV-treated (n = 6) chondrocytes, as measured by Luminex and ELISA. Boxes represents the interquartile range (IQR; 25th to 75th percentiles), with the line indicating mean and whiskers representing minimum to maximum values. (C) Normalised counts from bulk RNA sequencing for MMP1, MMP3, MMP13, TIMP3, ICAM1, IL6, TAC1, and NGF in untreated (n = 5), mild/moderate SFEV-treated (n = 6), and severe SFEV-treated (n = 6) chondrocytes. Statistical analysis was performed using 1-way ANOVA with Tukey post-hoc multiple comparison tests applied as appropriate. Significance levels: *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001. (D) Scatter plots of the protein concentration (pg/ml) of the analytes BDNF, IL-6, NGF, IL1β, MMP1 and MMP13 in SFEV lysates. The concentration of the analyte MMP3 is not shown as its concentration exceeded the upper limit of the standard curve. (E) Linear regression analysis of SFEV NGF protein concentration with VAS, EQ5D and OKS patient-reported scores (n = 13 patients). NGF protein was quantified by ELISA of SFEVs lysed with 0.5% Triton-X. Data points represent individual sample values, and bars show the mean.

Table 1.

Characteristics of OA patient cohort for SFEV analyses.

Table 1.

Characteristics of OA patient cohort for SFEV analyses.

| |

Mild/moderate OA |

Severe OA |

p value |

| |

n = 7 |

n = 4 |

|

| OKS1

|

26.8 ± 3.3 |

15.25 ± 3.38 |

*p = 0.0443 |

| EQ5D(sum) 2

|

7.6 ± 0.48 |

8.750 ± 0.63 |

p = 0.1722 |

| VAS3

|

6.6 ± 0.93 |

5.667 ± 1.86 |

p = 0.6106 |

| Age |

64.0 ± 6 |

57.5 ± 6 |

p = 0.5037 |

| Sex (male: female) |

5: 2 |

1: 3 |

|

| BMI4

|

32.2 ± 2.3 |

35.2 ± 2.5 |

p = 0.4217 |