1. Introduction

Hamstring muscle strain injury (HSI) is the most prevalent noncontact muscle injury among recreational and professional athletes engaged in sports involving sprinting (Biz et al., 2021; Gomes Neto et al., 2023; Lambert et al., 2022). This particular injury results in more missed days of participation than other sports-related injuries, with its treatment and recovery incurring substantial costs (Freeman et al., 2021; C. J. B. Kenneally-Dabrowski et al., 2019; Lambert et al., 2022; Tabben et al., 2022). Various studies have elucidated the mechanisms and risk factors associated with HSIs and have proposed preventive strategies (Bisciotti et al., 2019; Danielsson et al., 2020; Huygaerts et al., 2020a; Kalema et al., 2021; Rudisill et al., 2023; Yu et al., 2017). However, according to some recent studies, the decline in the HSI incidence rate has been insignificant (Ekstrand et al., 2023; Gudelis et al., 2023; Katagiri et al., 2023). The lack of incidence decline indicates that potential gaps between research and clinical implementation may exist, or the possibility that current studies ignore certain aspects of the HSI mechanism and risk factors.

For HSI prevention, it is important to consider the kinetic aspect. According to previous studies, the movements of the lower extremities during sprinting are controlled by all torque components that simultaneously act on each joint over the movement time (Huang et al., 2013). The net joint torque comprises the muscle-generated torque (MST), ground reaction force acting torque, gravity acting torque, and motion-dependent torque (MDT). Notably, MDT during the swing phase of the running cycle, which encompasses the torque generated by lower-limb segment movements and their mechanical interactions, has been identified as a potential risk factor for HSI due to the increased load on the hamstring muscles, particularly in the late swing phase (Huang et al., 2013; C. Kenneally-Dabrowski et al., 2019; Sun et al., 2015; Zhong et al., 2017). Specifically, excessive MDT results in exaggerated hip flexion and knee extension during the late swing phase, resulting in increased strain on the hamstring muscles. Therefore, substantial MST output from the hamstring muscles is required to counterbalance the excessive MDT at the hip and knee. Moreover, the late swing phase has been identified as the most hazardous phase in terms of HSIs. This phase is characterized by the sudden occurrence of HSI mechanisms, including excessive strain during eccentric contractions, the highest level of muscle activation, and explosive muscle force (Danielsson et al., 2020; C. J. B. Kenneally-Dabrowski et al., 2019; Yu et al., 2017). Thus, effective management of excessive MDT may help reduce the risk of HSI during the late swing phase (Huygaerts et al., 2020b; Kalema et al., 2021; C. Kenneally-Dabrowski et al., 2019; Mendiguchia et al., 2022). However, previous studies primarily inferred the effects of MDT on HSI by analyzing lower-extremity joint torques, without providing direct evidence of the relationship between MDT and HSI during the late swing phase of the running cycle. Therefore, further research is needed to establish a direct link between MDT and HSI occurrence.

A detailed analysis of the MDT revealed that shank angular acceleration (SAA) was the largest contributor to MDT at both the hip and knee joints during the swing phase of the running cycle. Specifically, SAA accounted for approximately 80% and 90% of MDT at the hip and knee joints, respectively, during the late swing phase(Huang et al., 2013; Sun et al., 2015; Zhong et al., 2017). This suggests that SAA may be a primary factor contributing to exaggerated hip flexion and knee extension torques during the late swing phase, increasing the torque demand on the hamstring muscle potentially elevating the risk of HSI. Therefore, examining the relationship between SAA and hamstring muscle activity during the late swing phase may help clarify the role of MDT as a risk factor for HSI.

On the other hand, previous studies have suggested a positive relationship between the angular acceleration of the lower-extremity segments during the swing phase and the maximum running speed. For instance, Clark et al. reported a high correlation between the maximum thigh angular acceleration during the swing phase of steady-state running and top speed (Clark et al., 2021). However, no study has specifically examined the relationship of SAA and maximum running speed. Clarifying the contribution of SAA to maximum running speed may provide valuable insights into the balance between performance enhancement and injury prevention in the context of hamstring function. This may be important given the possibility that higher-intensity shank movements may push the hamstrings beyond their physiological capacity, increasing the risk of injury (Buckthorpe et al., 2019). Therefore, recognizing the relationship between the SAA, hamstring muscle activity, and maximum speed may contribute to informed clinical decisions. This understanding may inform the development of more effective training programs aimed at maximizing hamstring ability while minimizing injury risk factors.

This study had three aims. First, we aimed to elucidate the pattern of SAA during the swing phase of the running cycle in treadmill sprinting. Second, we examined the relationship between the SAA and peak activation of the hamstring muscles during the swing phase. Finally, we aimed to investigate the relationship between the SAA and maximum speed. Three hypotheses were formulated to correspond to these aims: first, that the peak extension value of the SAA would align with the peak of the MDT during the late swing phase; second, the increased SAA might significantly enhance hamstring muscle activation during the swing phase; and finally, that peak values of SAA would positively correlate with maximum speed.

2. Methods

2.1. Participants

Twenty recreational players (including soccer, athletics) involving sprinting with no history of thigh muscle injuries and lower limb joint injuries in the previous six months were recruited. The participants gave their written informed consent (age: 25.75 ± 4.04 years, height:167.90 ± 6.98 cm, and weight: 62.95 ± 6.04 kg). This study was approved by the ethics committee of our institution.

An a priori sample size calculation was conducted (G*Power, version 3.1.9.6) to determine the necessary sample size for detecting an alternative correlation coefficient value, with α = 0.05, β = 0.2, H0 = 0 and H1 = 0.6. It was determined that a minimum of 19 participants were required to achieve 80% power.

2.2. Data Collections

All the trials were conducted in the motion analysis laboratory at our institution. The participants completed three sprints at 100% of their maximum speed on a treadmill, with each sprint lasting 10 s and a 5-min rest period between trials. Prior to the sprinting trials, participants wore their favorite running shoes and underwent a 10-min warm-up before running at maximum effort to record the maximum speed. To normalize the hamstring electromyography (EMG) data obtained during sprinting, the participants performed maximum voluntary isometric contraction tests (MVIC) following the warm-up protocol (Hegyi et al., 2019). Foot-strike and toe-off moments were recorded using force plates with a ground reaction force threshold of 30 N (Advanced Mechanical Technology, Inc., United States).

An inertial movement unit (IMU) comprising two 3-dimensional accelerometers (Trigno Avanti sensor; Delsys Inc., United States) was used to record shank linear acceleration during sprinting at a sampling rate of 144 Hz. The IMU was affixed to a 200 mm hard plastic board, with a 50 mm spacing distance between the two accelerometers, before being positioned on the lateral side of the shank. The placement location was determined by aligning it with the line connecting the centers of the knee and ankle joints, which were positioned approximately 50 mm above the lateral malleolus (Liu et al., 2009; Niswander et al., 2020; Rueterbories et al., 2013). Simultaneously, two electrodes (Trigno Avanti sensor; Delsys Inc., United States) were used to record the hamstring EMG data from the same leg at a sampling rate of 2000 Hz. The electrodes were placed at the midpoint of the line connecting the ischial tuberosity to the medial epicondyle of the tibia for the semitendinosus (ST), whereas the electrode for the biceps femoris long head (BF) was placed at the midpoint of the line connecting the ischial tuberosity to the lateral epicondyle of the tibia (Higashihara et al., 2018).

2.3. Data Processing

The EMG data were subjected to a bandpass filter in the range 20–450 Hz (Trigno software; Delsys Inc., United States). Subsequently, the band-pass-filtered EMG was rectified and processed with a low-pass digital filter at a cutoff frequency of 20 Hz to estimate the linear envelope EMG waveforms. Thereafter, these waveforms were normalized by dividing them by the mean MVIC amplitude (Hegyi et al., 2019; Higashihara et al., 2018).

To calculate the SAA using only accelerometer data, we employed the double-sensor difference-based algorithm outlined in

Appendix A, as recommended in previous studies (Liu et al., 2009; Rueterbories et al., 2013). Because hamstring muscle torque primarily counters MDT in the sagittal plane, which involves flexion and extension, this study analyzed the SAA within this plane.

2.4. Data Analysis

The running cycle data (comprising swing phase duration, stride length, stride frequency, SAA, and hamstring muscle activation) for each participant were derived from the mean of three trials, each consisting of five continuous cycles from the measurement leg. All data were normalized as a percentage of the swing phase duration (0−100%) and averages were calculated for all participants.

Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient (rho) was used to examine the relationship between the SAA and hamstring muscle activation. Specifically, the relationship between SAA values at three time points during the swing phase (peak flexion, peak extension, and foot strike) and the peak activation levels of both the BF and ST were analyzed. The significance level was set at 0.05. This approach was extended to assess the relationship between SAA and maximum speed, along with stride length and frequency. Interpretation of the relationships was guided by the absolute magnitude of rho, where values in the range 0.10−0.39 indicate a weak relationship, 0.40−0.69 a moderate relationship, 0.70−0.89 a strong relationship, and 0.90−1.00 a very strong relationship, following recommendations from previous studies(Schober & Schwarte, 2018). Additionally, the relationship between stride length, frequency, and maximum speed was analyzed to assess the strategy for maximizing speed.

All data analyses were performed in Python 3.10 (Python Software Foundation,

https://www.python.org/). All statistical analyses were performed using the R version 4.2.2 (R Core Team; R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Austria).

3. Results

The mean maximum speed for all participants was 4.15 ± 0.51 m/s (range = 3.33–5.00 m/s). The mean swing phase duration accounted for 27.90 ± 3.29% of the running cycle. The mean stride length and stride frequency were 2.76 ± 0.33 m and 1.50 ± 0.06 strides/s, respectively. In addition, in this study, the maximum speed exhibited a very strong positive relationship only with the stride length (p < 0.001, rho = 0.860), whereas no significant relationship with stride frequency was observed.

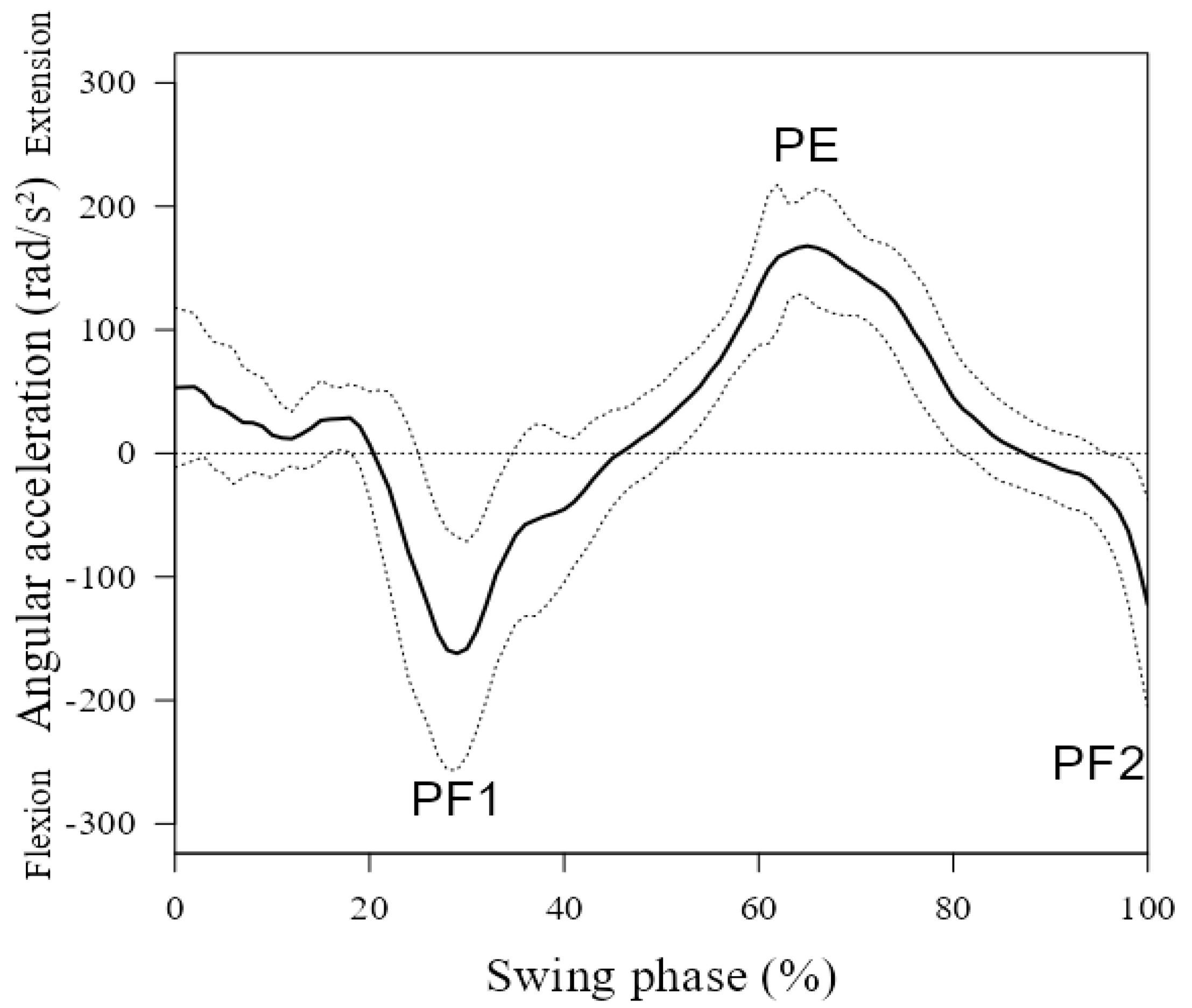

3.1. SAA During the Swing Phase

During the swing phase of the running cycle in maximum speed sprinting, the SAA exhibited an alternation pattern between flexion and extension. The SAA reached its initial peak flexion value (PF1) at approximately 30% of the swing duration, before attaining the maximum extension value (PE) at approximately 70% of the swing duration. Towards the end of the swing phase, the SAA again reached PF2 at the foot-strike (

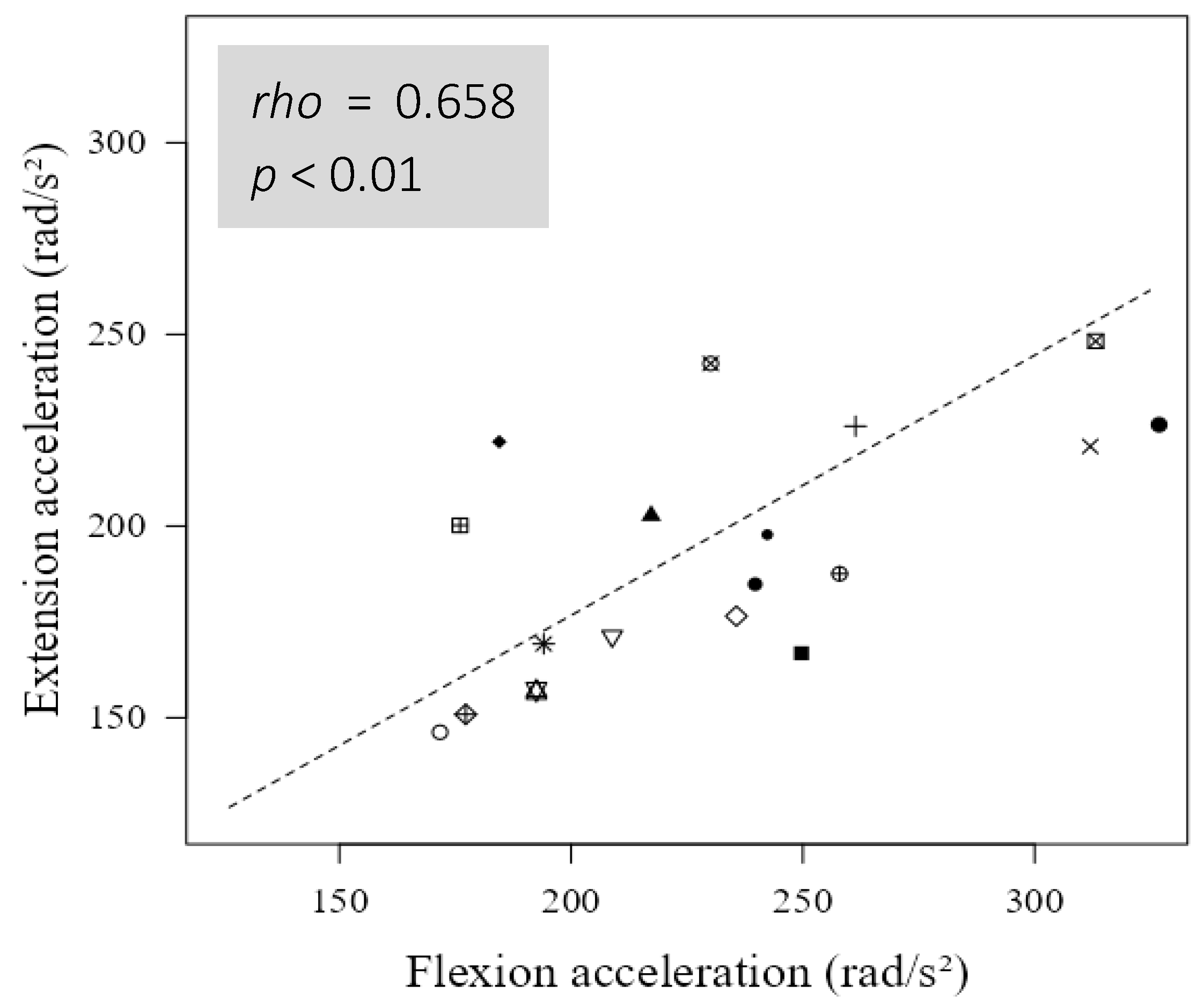

Figure 1). For a more detailed analysis of the SAA, a moderately positive relationship was observed between PF1 and PE during the swing phase (

p < 0.01,

rho = 0.658;

Figure 2).

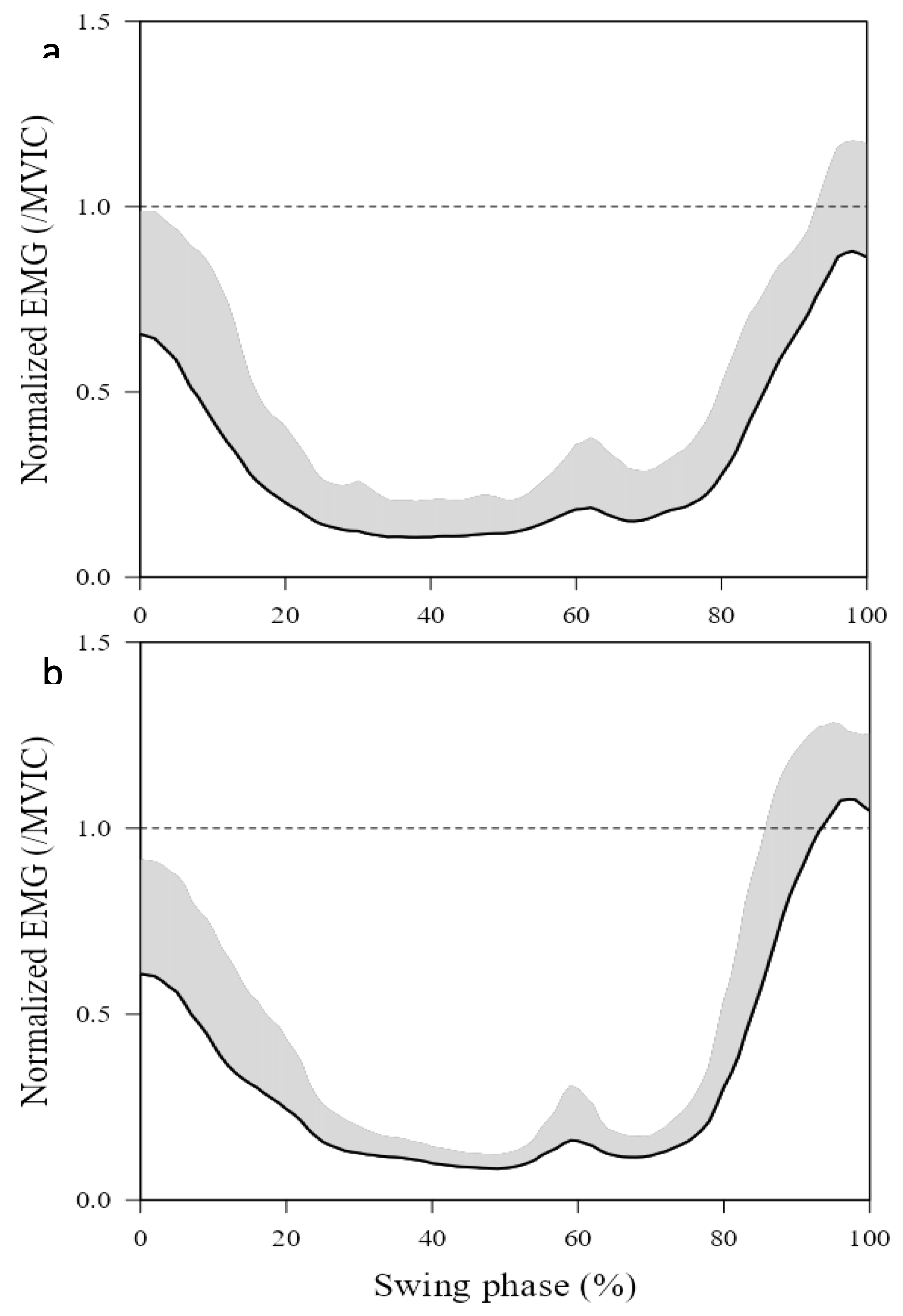

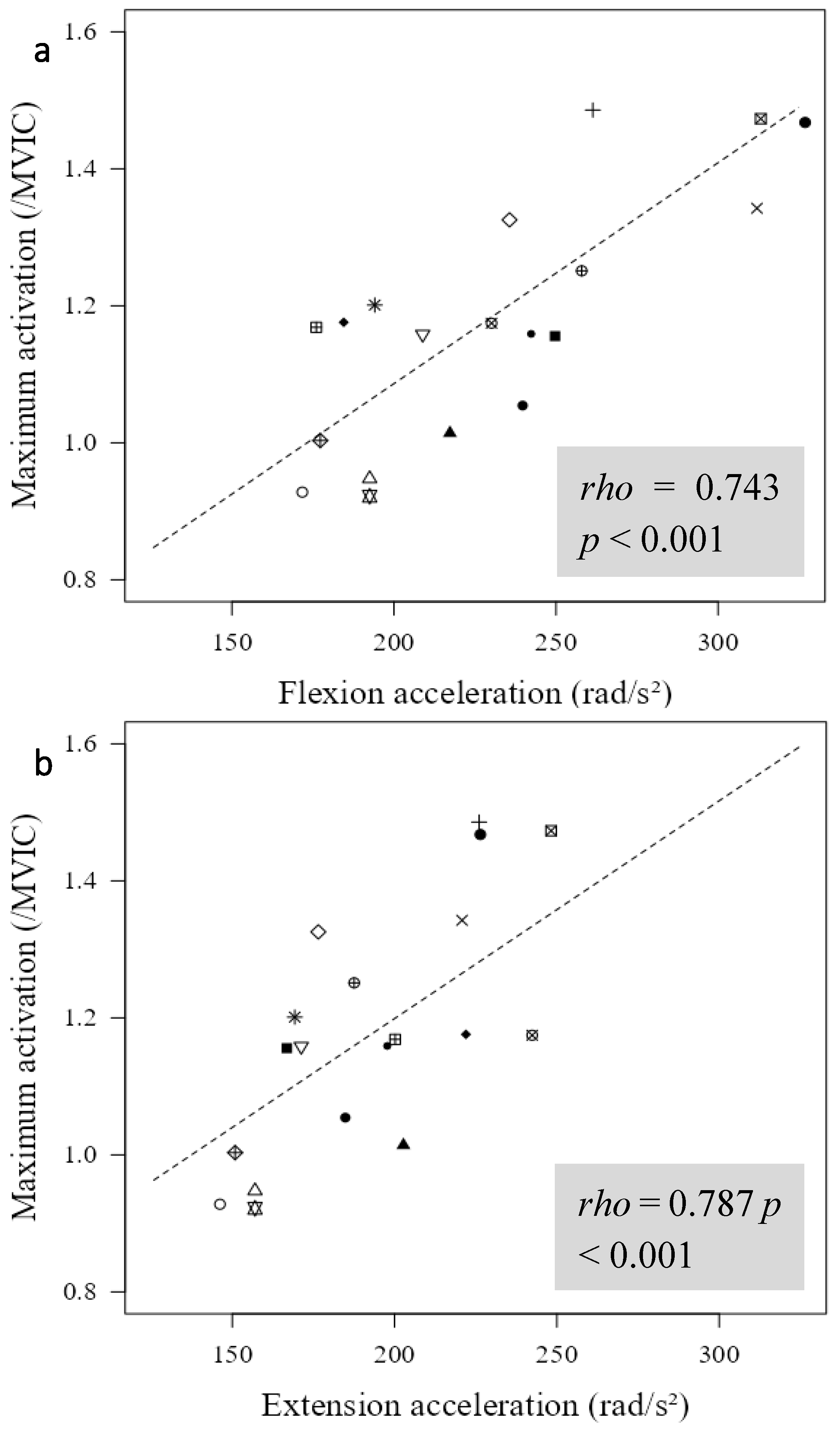

3.2. SAA and Hamstring Muscle Activation

Both hamstring muscles (BF and ST) were activated during the initial and late swings (the first 20% and last 20% of the swing duration, respectively), with peak activation in the late swing (

Figure 3). The peak activation of the ST was significantly higher than that of the BF during the late swing (

p < 0.05), whereas no significant differences were observed in muscle activation between the BF and ST during the initial swing (

p > 0.05). Strong positive relationships between PF1 and PE of SAA and peak activation of ST were observed (

p < 0.001,

rho = 0.737 for PF1, and

rho = 0.787 for PE), whereas no significant correlation between SAA and peak activation of BF was observed (

Figure 4).

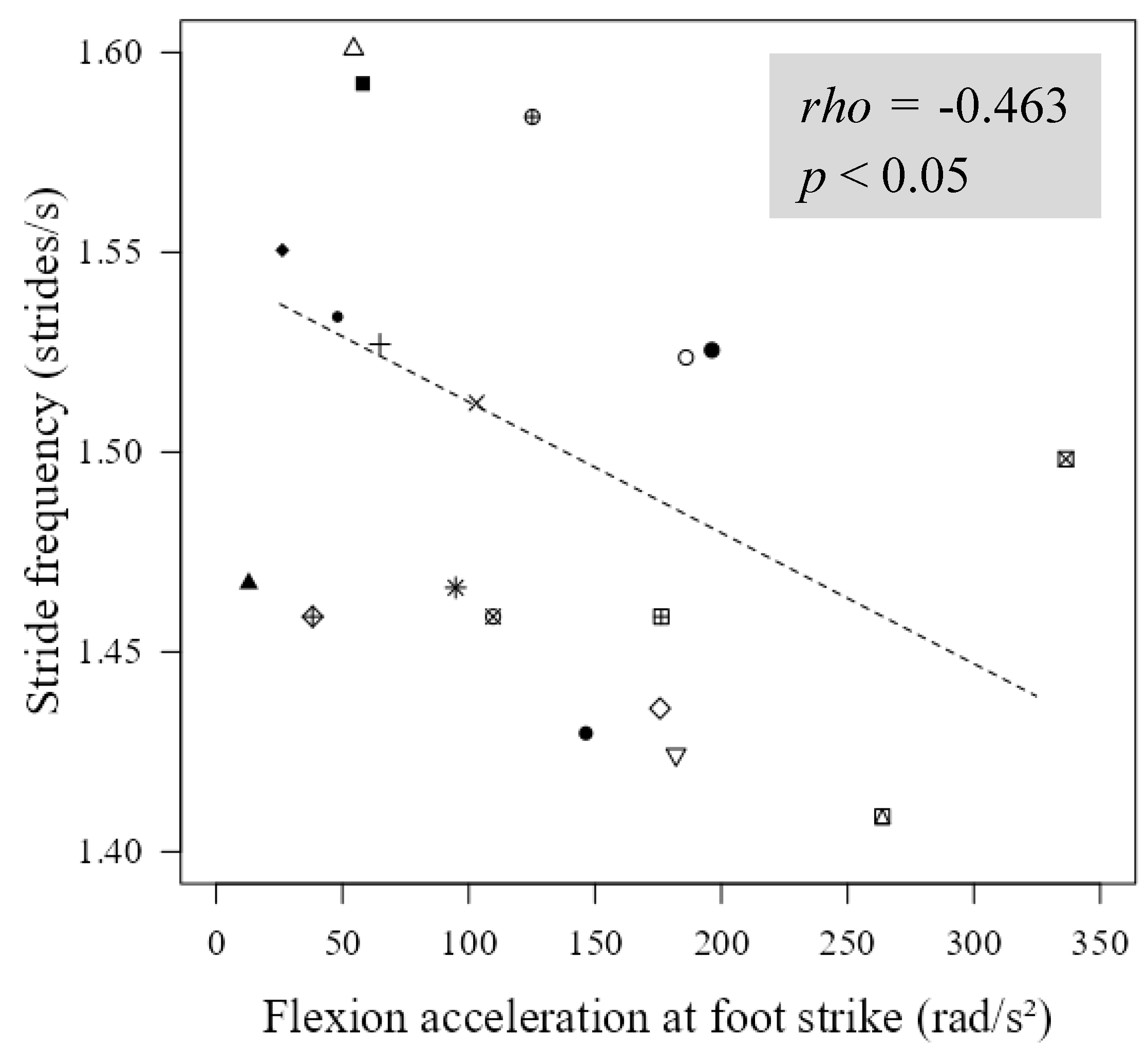

3.3. SAA and Maximum Speed

No significant relationship was observed between the SAA and maximum speed. However, a moderate negative relationship was observed between stride frequency and PF2 of SAA during maximum speed sprinting (

p < 0.05,

rho = -0.463;

Figure 5), while no significant relationship between stride length and SAA was observed.

4. Discussions

This study aimed to elucidate the pattern of SAA during the swing phase of maximum speed sprinting, examine its relationship with peak hamstring muscle activation during this period, and investigate its association with maximum running speed. The findings of this study support the first and second hypotheses, revealing an alternative pattern between flexion and extension of the SAA during the swing phase, with peak values corresponding to the peak of MDT. In addition, statistically significant positive relationships between the SAA and hamstring muscle activation. However, the third hypothesis was contradictory, as no relationship was observed between peak SAA values and maximum speed.

This study is the first to elucidate the SAA pattern during the swing phase of maximum-speed sprinting. The observed SAA pattern aligns with previous findings of MDT patterns in the knees and hips (Sun et al., 2015; Zhong et al., 2017). The PF1 of the SAA (occurring at approximately 30% of the swing phase) corresponds with a previous report on the peak MDT in the knee flexion direction (during 30−40% of the swing phase). Conversely, the PE of the SAA (observed at approximately 70% of the swing phase) aligned with the peak MDT in the knee extension and hip flexion direction during 70−80% of the swing phase (Huang et al., 2013; Sun et al., 2015; Zhong et al., 2017). Given the main role of the hamstring muscle in counterbalancing the MDT during the late swing period, the period around the PE of the SAA may be particularly hazardous for HSI. This is because the hamstring muscles undergo heavy loading to extend the hip and flex the knee in preparation for the next foot strike during this period (Huygaerts et al., 2020b; Yu et al., 2017; Zhong et al., 2017).

Moreover, the positive correlation between PF1 and PE in the SAA pattern indicated that greater shank flexion acceleration in the first half tended to exhibit higher shank extension acceleration in the second half of the swing. The corresponding increases in PF1 and PE observed in this study could be attributed to suboptimal coordination in the thigh anteroposterior muscles during the swing phase of maximum-speed sprinting, as previously identified as a risk factor for HSI and negative effects on running speed (Clark et al., 2021; Kakehata et al., 2021). A delay in transitioning from hamstring to rectus femoris activity following toe-off may result in higher PF1 during the first half of the swing. This delay can prolong the backside movement of the thigh and shank, potentially increasing the total stride time. Furthermore, this delayed transition may result in prolonged activation time of the rectus femoris, which is responsible for moving the swing leg forward in the latter half of the swing phase. This prolonged activation impedes subsequent hamstring activation and contributes to increased PE. These factors may predispose patients to a high-risk pattern of HSI, characterized by greater demand loading on the hamstring muscles and longer foot-ground contact distance ahead of the center of mass (Bramah et al., 2023; Clark et al., 2021; Kakehata et al., 2021).

Strong positive correlations between PF1 and PE with peak ST activation during the late swing phase indicate that SAA contributes significantly to increased hamstring muscle loading, increasing the risk of HSI. This study provides concrete evidence supporting previous reports on the relationship between the SAA and HSI, which were previously assumed through the analysis of lower-limb joint torque (Huang et al., 2013; Sun et al., 2015; Zhong et al., 2017). Additionally, our findings align with existing perspectives, indicating an association between the decreased ability to decelerate shank extension during the late swing phase and HSI(Huygaerts et al., 2020b; Kalema et al., 2022; C. Kenneally-Dabrowski et al., 2019). Consequently, the amalgamation of the obtained results with those of previous research underscores the heightened risk of HSI associated with excessive SAA during the swing phase.

Among the hamstring muscles, our findings support prior research emphasizing the significant role of the ST over the BF during the late swing in mitigating excessive thigh and shank movements (Higashihara et al., 2010, 2018). Specifically, the ST plays a crucial role in generating muscle torque to counteract the effects of SAA and facilitate rapid shank repositioning for the subsequent foot strike. Consequently, excessive SAA may impose heavier loads on the ST during the late swing phase. The observed effect of SAA on ST activation in this study sheds light on the more frequent injury occurrence in the ST compared to the BF, despite the BF displaying a larger peak muscle-tendon strain than the ST during the late swing phase, as reported in recent studies (Hassid et al., 2023; Lempainen et al., 2021). Moreover, our findings, in conjunction with existing research, provide additional insights into the mechanism of injury to the distal part of the ST during sprinting. Excessive SAA may contribute to increased tension across the distal tendon of the ST by elevating the MDT in the knee during the late swing phase. This increased tension could predispose the distal tendon of the ST to tear or rupture (McGarvey et al., 2022; Metcalf et al., 2019). Conversely, enhancing the muscle torque generated by the ST could improve the ability to decelerate the swing leg during the late swing phase, addressing improper eccentric control of the hamstrings, which is an essential component in designing HSI prevention programs (Kalema et al., 2022).

In this study, no significant relationship was observed between the PF1 and PE of the SAA with maximum speed, even when considering stride length and frequency. Additionally, we observed a moderate negative correlation between stride frequency and PF2 of the SAA. This indicates that higher shank flexion acceleration at foot strike may result in increased flexion moment and power absorption at the knee, owing to MDT during the swing-stance transition. This pattern could contribute to a greater ground contact time and reduced leg stiffness, which are factors known to decrease stride frequency (Haugen et al., 2019; Huang et al., 2013; Hunter et al., 2004). Therefore, our findings offer direct evidence supporting the notion that effectively managing excessive SAA may be a viable strategy for reducing hamstring muscle overloading during the late swing phase without significantly affecting maximum running speed (Kalema et al., 2022; C. Kenneally-Dabrowski et al., 2019; Sun et al., 2015; Zhong et al., 2017).

This study had some limitations that should be considered when interpreting its findings. First, the task of this study was investigating treadmill sprinting in a laboratory room; therefore, these conditions may cause some slight differences in sprinting kinematics and kinetics when compared to overground sprinting on regular surfaces such as grass and running fields (Sinclair et al., 2013). Second, all participants were recreational players with no experience in professional training or playing. Therefore, professional players may experience several differences in sprinting techniques after undergoing professional training.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, SAA in the swing phase exhibited a significant correlation with hamstring muscle activation, whereas no significant relationship was observed with maximum speed. These results indicated that the effective management of SAA during the swing phase may help reduce hamstring muscle load in the late swing phase without significantly affecting maximum speed. Moreover, the effect of SAA varied among different muscles, highlighting the potential need for targeted training methods to prevent hamstring injury. This information may be valuable for informing clinical decision-making by coaches and players when developing training programs.

Ethics approval: All participants provided informed consent prior to participation. The present study was reviewed and approved by the ethical committee of our institution.

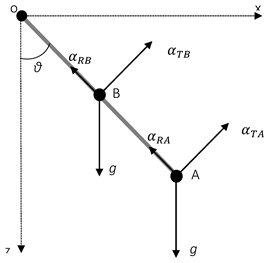

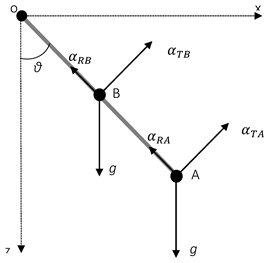

Measurement method using a double-sensor difference-based algorithm: The global reference frame XOZ was used, with O as the center of rotation of the knee (OX represents the anteroposterior direction and OZ represents the vertical direction). Two accelerometers (labeled A and B) were attached along the shank at two different positions in the corresponding directions. Consequently, the nonangular accelerations acting on these two sensors remained identical. The term

g denotes the gravitational acceleration,

αTA and

αTB are tangential acceleration measuring in A and B positions, respectively,

αRA and

αRB are radial acceleration measuring in A and B positions, respectively, and

θ is the rotational angular displacement of the shank. The SAA can subsequently be derived through vectorial subtraction of the directly observed acceleration signals from the two accelerometers. The equation required to solve this problem is expressed as follows:

where

denotes the distance between the two accelerometers A and B;

is the angular acceleration of the shank in the sagittal plane; and

and

are the tangential and radial acceleration observed from accelerometers A and B, respectively.

References

- Bisciotti, G. N.; Chamari, K.; Cena, E.; Carimati, G.; Bisciotti, A.; Bisciotti, A.; Quaglia, A.; Volpi, P. Hamstring Injuries Prevention in Soccer: A Narrative Review of Current Literature. Joints 2019, 07(03), 115–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biz, C.; Nicoletti, P.; Baldin, G.; Bragazzi, N. L.; Crimì, A.; Ruggieri, P. Hamstring strain injury (Hsi) prevention in professional and semi-professional football teams: A systematic review and meta-analysis. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2021, 18(16). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bramah, C.; Mendiguchia, J.; Dos’Santos, T.; Morin, J.-B. Exploring the Role of Sprint Biomechanics in Hamstring Strain Injuries: A Current Opinion on Existing Concepts and Evidence. Sports Medicine 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buckthorpe, M.; Wright, S.; Bruce-Low, S.; Nanni, G.; Sturdy, T.; Gross, A. S.; Bowen, L.; Styles, B.; Della Villa, S.; Davison, M.; Gimpel, M. Recommendations for hamstring injury prevention in elite football: Translating research into practice. In British Journal of Sports Medicine; BMJ Publishing Group, 2019; Vol. 53, Issue 7, pp. 449–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, K. P.; Meng, C. R.; Stearne, D. J. Evaluation of maximum thigh angular acceleration during the swing phase of steady-speed running. Sports Biomechanics 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danielsson, A.; Horvath, A.; Senorski, C.; Alentorn-Geli, E.; Garrett, W. E.; Cugat, R.; Samuelsson, K.; Hamrin Senorski, E. The mechanism of hamstring injuries-A systematic review. BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders 2020, 21(1), 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekstrand, J.; Bengtsson, H.; Waldén, M.; Davison, M.; Khan, K. M.; Hägglund, M. Hamstring injury rates have increased during recent seasons and now constitute 24% of all injuries in men’s professional football: the UEFA Elite Club Injury Study from 2001/02 to 2021/22. British Journal of Sports Medicine 2023, 57(5), 292–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, B. W.; Talpey, S. W.; James, L. P.; Young, W. B. Sprinting and hamstring strain injury: Beliefs and practices of professional physical performance coaches in Australian football. Physical Therapy in Sport 2021, 48, 12–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes Neto, M.; Fossati Metsavaht, L.; Luciano Arcanjo, F.; de Souza Guimarães, J.; Conceição, C. S.; Guadagnin, E. C.; Carvalho, V. O.; de Oliveira Lomelino Soares, G. L. Epidemiology of Lower-extremity Musculoskeletal Injuries in Runners: An Overview of Systematic Reviews. Current Emergency and Hospital Medicine Reports 2023, 11(2), 74–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gudelis, M.; Pruna, R.; Trujillano, J.; Lundblad, M.; Khodaee, M. Epidemiology of hamstring injuries in 538 cases from an FC Barcelona multi sports club. Physician and Sportsmedicine 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassid, B. V.; Warrick, A. E.; Ray, J. W. Hamstring Strain Ultrasound Case Series: Semitendinosus Injuries Dominant in NCAA Division I Athletes. Journal of Athletic Training 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haugen, T.; McGhie, D.; Ettema, G. Sprint running: from fundamental mechanics to practice—a review. European Journal of Applied Physiology 2019, 119(6), 1273–1287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hegyi, A.; Gonçalves, B. A. M.; Finni, T.; Cronin, N. J. Individual Region-and Muscle-specific Hamstring Activity at Different Running Speeds. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise 2019, 51(11), 2274–2285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Higashihara, A.; Nagano, Y.; Ono, T.; Fukubayashi, T. Differences in hamstring activation characteristics between the acceleration and maximum-speed phases of sprinting. Journal of Sports Sciences 2018, 36(12), 1313–1318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higashihara, A.; Ono, T.; Kubota, J.; Okuwaki, T.; Fukubayashi, T. Functional differences in the activity of the hamstring muscles with increasing running speed. Journal of Sports Sciences 2010, 28(10), 1085–1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.; Liu, Y.; Wei, S.; Li, L.; Fu, W.; Sun, Y.; Feng, Y. Segment-interaction and its relevance to the control of movement during sprinting. Journal of Biomechanics 2013, 46(12), 2018–2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hunter, J. P.; Marshall, R. N.; McNair, P. J. Segment-interaction analysis of the stance limb in sprint running. Journal of Biomechanics 2004, 37(9), 1439–1446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huygaerts, S.; Cos, F.; Cohen, D. D.; Calleja-González, J.; Guitart, M.; Blazevich, A. J.; Alcaraz, P. E. Mechanisms of hamstring strain injury: Interactions between fatigue, muscle activation and function. In Sports; MDPI AG, 2020a; Vol. 8, Issue 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huygaerts, S.; Cos, F.; Cohen, D. D.; Calleja-González, J.; Guitart, M.; Blazevich, A. J.; Alcaraz, P. E. Mechanisms of hamstring strain injury: Interactions between fatigue, muscle activation and function. In Sports; MDPI AG, 2020b; Vol. 8, Issue 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kakehata, G.; Goto, Y.; Iso, S.; Kanosue, K. Timing of Rectus Femoris and Biceps Femoris Muscle Activities in Both Legs at Maximal Running Speed. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise 2021, 53(3), 643–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalema, R. N.; Duhig, S. J.; Williams, M. D.; Donaldson, A.; Shield, A. J. Sprinting technique and hamstring strain injuries: A concept mapping study. Journal of Science and Medicine in Sport 2022, 25(3), 209–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalema, R. N.; Schache, A. G.; Williams, M. D.; Heiderscheit, B.; Trajano, G. S.; Shield, A. J. Sprinting biomechanics and hamstring injuries: Is there a link? a literature review. Sports 2021, 9(10), 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katagiri, H.; Forster, B. B.; Engebretsen, L.; An, J. S.; Adachi, T.; Saida, Y.; Onishi, K.; Koga, H. Epidemiology of MRI-detected muscle injury in athletes participating in the Tokyo 2020 Olympic Games. British Journal of Sports Medicine 2023, 57(4), 218–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenneally-Dabrowski, C.; Brown, N. A. T.; Warmenhoven, J.; Serpell, B. G.; Perriman, D.; Lai, A. K. M.; Spratford, W. Late swing running mechanics influence hamstring injury susceptibility in elite rugby athletes: A prospective exploratory analysis. Journal of Biomechanics 2019, 92, 112–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kenneally-Dabrowski, C. J. B.; Brown, N. A. T.; Lai, A. K. M.; Perriman, D.; Spratford, W.; Serpell, B. G. Late swing or early stance? A narrative review of hamstring injury mechanisms during high-speed running. Scandinavian Journal of Medicine and Science in Sports 2019, 29(8), 1083–1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambert, C.; Reinert, N.; Stahl, L.; Pfeiffer, T.; Wolfarth, B.; Lachmann, D.; Shafizadeh, S.; Ritzmann, R. Epidemiology of injuries in track and field athletes: a cross-sectional study of specific injuries based on time loss and reduction in sporting level. Physician and Sportsmedicine 2022, 50(1), 20–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lempainen, L.; Kosola, J.; Pruna, R.; Sinikumpu, J. J.; Valle, X.; Heinonen, O.; Orava, S.; Maffulli, N. Tears of biceps femoris, semimembranosus, and semitendinosus are not equal—a new individual muscle-tendon concept in athletes. Scandinavian Journal of Surgery 2021, 110(4), 483–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, K.; Liu, T.; Shibata, K.; Inoue, Y.; Zheng, R. Novel approach to ambulatory assessment of human segmental orientation on a wearable sensor system. Journal of Biomechanics 2009, 42(16), 2747–2752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McGarvey, C. R.; Montgomery, J. R.; Spicer, P. J. Isolated distal semitendinosus tendon tear in a collegiate athlete. Radiology Case Reports 2022, 17(12), 4723–4726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mendiguchia, J.; Castano-Zambudio, A.; Jimenez-Reyes, P.; Morin, J. B.; Edouard, P.; Conceicao, F.; Tawiah-Dodoo, J.; Colyer, S. L. Can We Modify Maximal Speed Running Posture? Implications for Performance and Hamstring Injury Management. International Journal of Sports Physiology and Performance 2022, 17(3), 374–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metcalf, K. B.; Knapik, D. M.; Voos, J. E. Damage to or Injury of the Distal Semitendinosus Tendon During Sporting Activities: A Systematic Review. In HSS Journal; Springer New York LLC, 2019; Vol. 15, Issue 2, pp. 185–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niswander, W.; Wang, W.; Kontson, K. Optimization of IMU sensor placement for the measurement of lower limb joint kinematics. Sensors (Switzerland) 2020, 20(21), 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudisill, S. S.; Varady, N. H.; Kucharik, M. P.; Eberlin, C. T.; Martin, S. D. Evidence-Based Hamstring Injury Prevention and Risk Factor Management: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. American Journal of Sports Medicine 2023, 51(7), 1927–1942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rueterbories, J.; Spaich, E. G.; Andersen, O. K. Characterization of gait pattern by 3D angular accelerations in hemiparetic and healthy gait. Gait and Posture 2013, 37(2), 183–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schober, P.; Schwarte, L. A. Correlation coefficients: Appropriate use and interpretation. Anesthesia and Analgesia 2018, 126(5), 1763–1768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sinclair, J.; Richards, J.; Taylor, P. J.; Edmundson, C. J.; Brooks, D.; Hobbs, S. J. Three-dimensional kinematic comparison of treadmill and overground running. Sports Biomechanics 2013, 12(3), 272–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, Y.; Wei, S.; Zhong, Y.; Fu, W.; Li, L.; Liu, Y. How joint torques affect hamstring injury risk in sprinting swing-stance transition. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise 2015, 47(2), 373–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabben, M.; Eirale, C.; Singh, G.; Al-Kuwari, A.; Ekstrand, J.; Chalabi, H.; Bahr, R.; Chamari, K. Injury and illness epidemiology in professional Asian football: Lower general incidence and burden but higher ACL and hamstring injury burden compared with Europe. British Journal of Sports Medicine 2022, 56(1), 18–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, B.; Liu, H.; Garrett, W. E. Mechanism of hamstring muscle strain injury in sprinting. In Journal of Sport and Health Science; Elsevier B.V, 2017; Vol. 6, Issue 2, pp. 130–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, Y.; Fu, W.; Wei, S.; Li, Q.; Liu, Y. Joint Torque and Mechanical Power of Lower Extremity and Its Relevance to Hamstring Strain during Sprint Running. Journal of Healthcare Engineering 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).