Submitted:

24 March 2025

Posted:

25 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

Background to the Study

Problem Statement

Objectives of the Study

Justification of the Study

Methodology

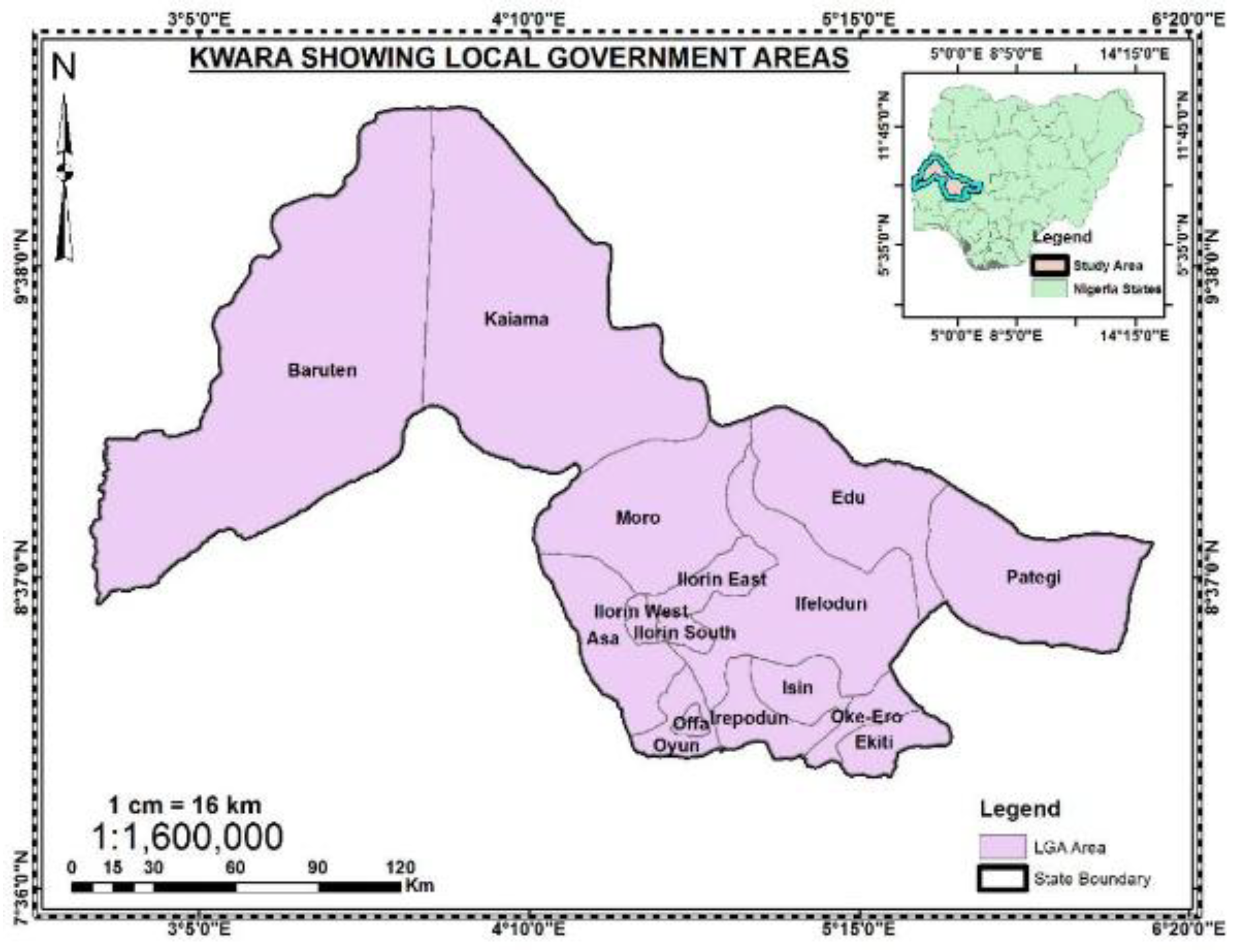

Study Area

Sources of Data/Method of Data Collection

Sampling Techniques and Sample Size

Analytical Techniques/Method of Analysis

Descriptive Statistics

Sigma Scoring Method

Logit Regression

- ➢

- X1 = Farmers' age (years);

- ➢

- X2 = Income (Naira)

- ➢

- X3 = Access to credit (1= access and 0 otherwise)

- ➢

- X4 = Level of education (years)

- ➢

- X5 = Awareness on digital technologies (1= aware and 0 otherwise)

- ➢

- X6 = Size of the household (numbers)

- ➢

- X7 = Years of farming experience

- ➢

- e = error term.

Ordinary Least Square Regression

- Where Y= Total Factor Productivity: A/TVC (Dependent Variable)

- Where A = Value of Rice output (₦)/farmer

- TVC = Total Variable Cost (₦)

- ➢

- X1= Type of digital technology used(1=mobile base extension, 2= mobile base extension market info, 3= others

- ➢

- X2= Frequency of usage of digital technology in days/week

- ➢

- X3= Purpose of usage of digital technology,(1=rice production, 0=others)

- ➢

- X4 =Age of farmers (Years)

- ➢

- X5= Number of network access/usage per farmer

- ➢

- X6= Educational level of the farmer in years.

Likert Scale Analysis

Limitations of the Study

Results and Discussion

Rice Farmers' Socio-Economic Features/Characteristics

Digital Technologies Used by Rice Farmers and How It Is Used

| Types of mobile phones used | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Android | 65 | 43.05 |

| Common phones | 51 | 33.77 |

| Android & common phones | 34 | 22.52 |

| Android & I-phone | 1 | 0.66 |

| Total | 151 | 100 |

| Years of mobile phone usage(Years) | Frequency | Percentage | Mean |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1-5 | 25 | 16.56 | 11.33 years |

| 6-10 | 67 | 44.37 | |

| 11-15 | 36 | 23.84 | |

| >15 | 23 | 15.23 | |

| Total | 151 | 100 |

Farm Level of Adoption and Uptake of Digital Technologies (N=151)

Determinant of Digital Technology Usage Among Rice Farmers (N=151)

Effect of Digital Technologies on the Productivity of Rice Farmers (N=151)

|

Variable Y= Total Factor productivity |

Co-efficient | p-value |

|---|---|---|

| Age(years) | -0.031 | 0.111 |

| Level of education(years of schooling) | -0.029 | 0.525 |

| Purpose of usage of digital technologies | 1.923*** | 0.001 |

| Number of network usage | -0.296 | 0.108 |

| Frequency of usage of digital technologies | 1.256** | 0.014 |

| Access to extension agents | 1.400** | 0.011 |

| Constant | 5.092 | 0.000 |

| R- square | 0.5451 | |

| Adjusted R- square | 0.5262 | |

| F- value | 28.76 | 0.000 |

Constraints to Rice Farmers’ Ultilization of Digital Technologies

| Constraints | Strongly Disagree | Disagree | Agree | Strongly Agree | Mean | Rank |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Little or no internet network access | 0(0.00) | 33(21.85) | 93(61.59) | 25(16.56) | 2.95 | 1st |

| Inadequate power supply | 1(0.66) | 32(21.19) | 93(61.59) | 25(16.56) | 2.94 | 2nd |

| Poor access to credit | 2(1.32) | 41(27.15) | 99(65.56) | 9(5.96) | 2.76 | 3rd |

| High cost of mobile phones | 3(1.99) | 50(33.11) | 82(54.30) | 16(10.60) | 2.74 | 4th |

| Poor access to extension agent | 1(0.66) | 116(76.82) | 30(19.87) | 4(2.65) | 2.25 | 5th |

| Lack of literacy | 3(1.99) | 133(88.08) | 14(9.27) | 1(0.66) | 2.09 | 6th |

Summary, Conclusion and Recommendations

Summary of the Major Findings

Conclusions

Recommendations

- Since digital technologies (purpose of usage and frequency of usage) had a statistically positive effect on productivity, there is a need for a targeted enlightenment campaign among farmers on the uses and benefits of engaging digital technologies for enhanced productivity.

- The Nigerian Government and development partners should create an enabling environment and improved digital rural infrastructure to enhance farmers’ adoption of digital technologies.

- For farmers to use digital technology to access modern information sources, the government should create credit facilities

References

- Abbas, A.M.; Agada, I.G.; Kolade, O. Impacts of rice importation on Nigeria’s economy. Journal of Scientific Agriculture 2018, 2, 71–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adeagbo, O.A.; Ojo, T.O.; Adetoro, A.A. Understanding the determinants of climate change adaptation strategies among smallholder maize farmers in South-west, Nigeria. Heliyon 2021, 7, e06231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adeoti, A.I.; Coster, A.S.; Akanni, T.A. Analysis of farmers’ vulnerability, perception and adaptation to climate change in Kwara State, Nigeria. International Journal of Climate Research 2016, 1, 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- African Development Bank. Nigeria: Country Food and Agriculture Delivery Compact. 2023. Available online: https://www.afdb.org/en/documents/nigeria-country-food-and-agriculture-delivery-compact.

- Agbamu, J. U Essentials of Agricultural Communication in Nigeria; Malthouse Press Limited: Lagos, 2006; pp. 34–56. [Google Scholar]

- Ali, S.; Jabeen, U.A.; Nikhitha, M. Impact of ICTs on agricultural productivity. European Journal of Business, Economics and Accountancy 2016, 4. [Google Scholar]

- Arunachalam, D.; Kumar, N.; Kawalek, J.P. Understanding big data analytics capabilities in supply chain management: Unravelling the issues, challenges and implications for practice. Transportation Research Part E: Logistics and Transportation Review 2018, 114, 416–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayinde, O.E.; Fatigun, O.; Ogunbiyi, K.; Ayinde, K.; Ambali, Y.O. Assessment of Central Bank Intervention on Rice Production in Kwara State, Nigeria: A Case-study of Anchor Borrower’s Program. In Proceedings of the 2018 Conference, Vancouver, British Columbia, 28 July 28--2 August 2018; International Association of Agricultural Economists, 277429. 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Babatunde, R.O.; Omotosho, O.A.; Sholotan, O.S. Socio–economic characteristics and food security status of farming households in Kwara State, North-Central, Nigeria. Pakistan Journal of Nutrition 2007, 6, 49–58. [Google Scholar]

- Baumüller, H. Facilitating agricultural technology adoption among the poor: The role of service delivery through mobile phones; ZEF Working Paper Series, No. 93; University of Bonn, Center for Development Research (ZEF): Bonn, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Baumüller, H. Towards smart farming? Mobile technology trends and their potential for developing country agriculture. In Handbook on ICT in Developing Countries; Skouby, K.E., Williams, I., Gyamfi, A., Eds.; River Publishers: Delft, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Baumüller, H. The Little We Know: An Exploratory Literature Review on the Utility of Mobile Phone-Enabled Services for Smallholder Farmers. Journal of International Development 2018, 30, 134–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chekene, M.B.; Chancellor, T.S.B. Factors Affecting the Adoption of Improved Rice Varieties in Borno State, Nigeria. J. Agric. Ext 2015, 19, 21–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chhachhar, A.R.; Qureshi, B.; Khushk, G.M.; Ahmed, S. Impact of Information and Communication Technologies in Agricultural Development. Journal of Basic and Applied Scientific Research 2014, 4, 281–288. [Google Scholar]

- Ehiakpor, D.S.; Danso-Abbeam, G.; Dagunga, G.; Ayambila, S.N. Impact of Zai technology on farmers’ welfare: Evidence from northern Ghana. Technology in Society 2019, 59, 101189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eitzinger, A.; Cock, J.; Atzmanstorfer, K.; Binder, C.R.; Läderach, P.; Bonilla-Findji, O.; Bartling, M.; Mwongera, C.; Zurita, L.; Jarvis, A. GeoFarmer: A monitoring and feedback system for agricultural development projects. Computers and Electronics in Agriculture 2019, 158, 109–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Federal Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development (FMARD). The Agricultural Promotion Policy (2016-2020): Building on the Successes of the ATA, Closing Key Gaps. Federal Government of Nigeria Policy and Strategy Document. 2016.

- Firouzi, S. Effect of Pre-Milling on Milled Rice Breakage – A Review. Thai Journal of Agricultural Science 2014, 47, 241–250. [Google Scholar]

- Food and Agriculture Organization. Digital Technologies in Agriculture and Rural Areas. 2018.

- Henri-Ukoha, A.; Anaeto, F.C.; Chikezie, C.; Ibeagwa, O.B.; Oshaji, L.I.; Ukoha, I.O.; Anyiam, K.H. Analysis of cassava value chain in Ideato south local government area, Imo State, South-East, Nigeria. International Journal of Life Sciences 2015, 4, 209–215. [Google Scholar]

- Jayathilake, H.A.C.K.; Jayaweera, B.P.A.; Waidyasekera, E.C.S. ICTs Adoption and Its’ Implications for Agriculture in Sri Lanka. Journal of Food and Agriculture 2008, 1, 54–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khatun, F.; Haider, M.Z. Impact of Technology Adoption on Agricultural Productivity. Journal of Agriculture and Crops 2016, 2, 87–93. [Google Scholar]

- Kituyi-Kwake, A.; Adigun, M.O. Analyzing ICTs use and access amongst rural women in Kenya. International Journal of Education and Development using Information and Communication Technology 2008, 4, 127–147. [Google Scholar]

- Kolawole, A.; Oladele, O.I.; Alarima, C.I.; Wakatsuki, T. Farmers’ Perception of Sawah Rice Production Technology in Nigeria. J. Hum. Ecol 2012, 37, 13–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwara State Agricultural Development Project (KWADP), Ilorin, Nigeria, 2007.

- Malsha, A.P.S.; Jayasinghe, A.P.R.; Wijeratne, M. Effect of ICT on Agricultural Production A Sri Lankan Case Study. Joint National Conference on Information Technology in Agriculture 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Masuka, B.; Matenda, T.; Chipomho, J.; Mapope, N.; Mupeti, S.; Tatsvarei, S.; Ngezimana, W. Mobile phone use by small-scale farmers: a potential to transform production and marketing in Zimbabwe. S. Afr. J. Agric. Ext. 2016, 44, 121–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matanmi, B.M.; Adesiji, G.B.; Owawusi, W.O.; Oladipo, F.O. Perceived factors limiting rice production in Patigi local government area of Kwara State, Nigeria. Journal of Agricultural and Social Research (JASR) 2011, 11, 40–45. [Google Scholar]

- Mohamed, K.; Temu, A. Access to credit and its effect on the adoption of agricultural technologies: The case of Zanzibar. In African Review of Money Finance and Banking; 2008; pp. 45–89. [Google Scholar]

- Musa, N.S.; Githeko, J.M.; El-siddig, K. The adoption and use of ICTS by small-scale farmers in Gezira State, Sudan. In Research Application Summary; 2012; pp. 625–633. [Google Scholar]

- Mwakaje, A.G. Information and Communication Technology for Rural Farmers Market Access in Tanzania. Journal of information Technology Impact 2010, 10, 111–128. [Google Scholar]

- Mwangi, M.; Kariuk, S. Factors Determining Adoption of New Agricultural Technology by Smallholder Farmers in Developing Countries. Journal of Economics and Sustainable Development 2015, 6. [Google Scholar]

- Nakasone, E.; Torero, M. A text message away: ICTs as a tool to improve food security. Agricultural Economics (United Kingdom) 2016, 47, 49–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Bureau of Statistics. Nigerian Gross Domestic Product Report; 2023; p. 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Nzonzo, D.; Mogambi, H. Analysis of Communication and Information Communication Technologies Adoption in Irrigated Rice Production in Mwea Irrigation Scheme, Kenya. International Journal of Education and Research 2016, 4. [Google Scholar]

- Ogunleye, M.T.; Bodunde, J.G.; Makinde, E.A.; Sobukola, O.P.; Shobo, B.A. Fertilizer type and harvest maturity index on nutritive content and proximate composition of tomato fruit. International Journal of Vegetable Science 2021, 27, 505–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okoedo-Okojie, D.U.; Omoregbee, F.E. Determinants of Access and Farmers’ use of Information and Communication Technologies (1CTs) in Edo State, Nigeria. J. Appl. Sci. Environ. Manage 2012, 16, 41–44. [Google Scholar]

- Olabode, O. Smart card identification management over a distributed database model. Journal of Computer Science 2011, 7, 1770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oladimeji, Y.U.; Abdulsalam, Z.; Abdullahi, A.N. Determinants of participation of rural farm households in non-farm activities in Kwara state, Nigeria: A paradigm of poverty alleviation. Ethiopian Journal of Environmental Studies and Management 2015, 8, 635–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oladimeji, Y.U.; Abdulsalam, Z.; Damisa, M.A.; Omokore, D.F. Estimating the determinants of poverty among artisanal fishing households in Edu and Moro local government areas of Kwara State, Nigeria. Agriculture and Biology Journal of North America 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olanrewaju, R.M. Climate and the growth cycle of yam plant in the Guinea Savannah Ecological Zone of Kwara State, Nigeria. Journal of Meteorological and Climate Science 2009, 7, 43–48. [Google Scholar]

- Omotesho, K.; Akinrinde, F.A.; Adenike, A.J.; and Awoyemi, A.O. Analysis of the Use of Information Communication Technologies in Fish Farming In Kwara State, Nigeria. Journal of Agribusiness and Rural Development 2019, 54, 327–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Opeyemi, G.; Adedeji, S.O.; Komolafe, S.E.; Arotiba, K.; Ifabiyi, J.O. Consumers’ Beliefs And Behaviours Influencing The Patronage And Consumption Of Locally Produced And Imported Rice In Niger State, Nigeria. Nigerian Journal of Agriculture, Food and Environment's 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Premium Times. Nigeria spends $2.41b on rice importation in 3 years–Emefiele. 2015. Available online: www.premiumtimesng.com/business/187406-nigeria-spends-2-4bn-on-rice-importation-in-3-years-emefiele.html.

- Saito, K.; Senthilkumar, K.; Dossou-Yovo, E.R.; Ali, I.; Johnson, J.-M.; Mujawamariya, G.; Rodenburg, J. Status quo and challenges of rice production in sub-Saharan Africa. Plant Production Science 2023, 26, 320–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samuel, M. Mobile Phone Use by Zimbabwean Smallholder Farmers: A Baseline Study. The African Journal of Information and Communication 2018, 29–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sennuga, S.O.; Conway, J.S.; Sennuga, M.A. Impact of Information and Communication technologies (ICTS) on Agricultural Productivity among smallholder farmers: Evidence from Sub-Saharan African Communities. International Journal of Agricultural Extension and Rural Development Studies 2020, 7, 27–43. [Google Scholar]

- Smit, L.C.B. Climate change, food security, and livelihoods in sub-Saharan Africa. Regional Environmental Change 2016, 385–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sodiya, C.I.; Oyediran, W.O. Contributions of melon production to livelihood sustainability of rural farming households in Oyo State, Nigeria. Journal of Biology, Agriculture and Healthcare 2014, 4, 8–18. [Google Scholar]

- Tavershima, T.; Kotur, L.N.; Tseaa, E.M. Food Security and Population Growth in Nigeria. Direct Research Journal of Agriculture and Food Science 2022, 10, 176–183. [Google Scholar]

- UNFPA. World Population Dashboard: Nigeria. 2023. Available online: https://www.unfpa.org/data/world-population/NG.

- World Bank. Agriculture Overview. 2023. Available online: https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/agriculture/overview.

- World Economic Forum. Grow back better? Here’s how digital agriculture could revolutionize rural communities affected by COVID-19. 2020. Available online: https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2020/07/digital-agriculture-technology/.

- World Economic Forum. 3 ways digital technology can be a sustainability game-changer. Davos Agenda. 2022. Available online: https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2022/01/digital-technology-sustainability-strategy/.

| LGA | COMMUNITIES | NO OF RESPONDENTS |

|---|---|---|

| Edu | Bokungi | 15 |

| Patidzuru | 15 | |

| Efu Abu | 15 | |

| Ndamaraki | 15 | |

| Takogabi | 16 | |

| Patigi | Lalagi | 15 |

| Sakpefu | 15 | |

| Dzwajiwo | 15 | |

| Godiwa | 15 | |

| Edogi-Kpansanko | 15 | |

| TOTAL = 2 | 10 | 151 |

| Variables | Frequency | Percentage | Mean |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age(years) | |||

| 20-30 | 60 | 39.74 | 35.62 years |

| 31-40 | 52 | 34.43 | |

| 41-50 | 29 | 19.21 | |

| >50 | 10 | 6.62 | |

| Total | 151 | 100.0 | |

| Gender | |||

| Male | 150 | 99.34 | |

| Female Total |

1 151 |

0.66 100.0 |

|

| Marital status | |||

| Married | 124 | 82.12 | |

| Single | 27 | 17.88 | |

| Total | 151 | 100.0 | |

| Educational status | |||

| None formal | 3 | 1.99 | |

| Primary | 10 | 6.62 | |

| Secondary | 46 | 30.46 | |

| Tertiary | 90 | 59.60 | |

| Others | 2 | 1.32 | |

| Total | 151 | 100.0 | |

| Years of schooling | |||

| 0-6 | 17 | 11.26 | 13.34 years |

| 7-12 | 43 | 28.48 | |

| 13-18 | 88 | 58.27 | |

| >18 | 3 | 1.99 | |

| Total | 151 | 100.0 | |

| Household size | |||

| 1-5 | 59 | 39.07 | 7.15 persons |

| 6-10 | 69 | 45.70 | |

| 11-15 | 9 | 5.96 | |

| >15 | 14 | 9.27 | |

| Total | 151 | 100.0 | |

| Primary occupation | |||

| Farming | 147 | 97.35 | |

| Civil servant | 4 | 2.65 | |

| Total | 151 | 100.0 | |

| General farming experience | |||

| <10 | 17 | 11.26 | 18.08 years |

| 10-20 | 95 | 62.91 | |

| >20 | 39 | 25.83 | |

| Rice farming experience | |||

| <10 | 22 | 14.57 | 17.43 years |

| 10-20 | 96 | 63.58 | |

| >20 | 33 | 21.85 | |

| Total | 151 | 100.0 | |

| Farm size(hectares) | |||

| 1-5 | 48 | 31.79 | 7.75 hectares |

| 6-10 | 82 | 54.30 | |

| >10 | 21 | 13.91 | |

| Total | 151 | 100.0 | |

| Farming status | |||

| Full time | 92 | 60.93 | |

| Part time | 59 | 39.07 | |

| Total | 151 | 100.0 | |

| Membership of cooperative | |||

| Yes | 84 | 55.63 | |

| No | 67 | 44.37 | |

| Total | 151 | 100.0 | |

| Contacts with an extension agent | |||

| 0 | 46 | 30.46 | 2.79 times |

| 1-5 | 90 | 59.61 | |

| 6-10 | 12 | 7.94 | |

| >10 | 3 | 1.99 | |

| Total | 151 | 100.0 |

| Types of digital technology used | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Mobile phones | 147 | 97.35 |

| Computers | 3 | 1.99 |

| Tablets | 3 | 1.99 |

| Drones | 0 | 0.00 |

| Total | 151 | 100 |

| Digital technologies | Frequency | Percentage | Sigma Score | Remark |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mobile Phones | 147 | 97 | 5.94 | High |

| Computers | 3 | 2 | 1.34 | Low |

| Tablets | 3 | 2 | 1.34 | Low |

| Drones | 0 | 0 | 0.00 | Low |

| Variable | Co-efficient | p-value | Odd ratio |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age(years) | -0.177*** | 0.004 | 0.838 |

| Size of households | -0.408** | 0.014 | 0.665 |

| Income from rice farming | -5.270 | 0.969 | 0.999 |

| Access to credit | 2.337** | 0.012 | 10.346 |

| Level of education(years of schooling) | 0.219 | 0.283 | 1.246 |

| Awareness of digital technologies | 2.131*** | 0.008 | 8.423 |

| Farm size | 0.102 | 0.954 | 0.989 |

| Rice farming experience | 0.144** | 0.039 | 1.155 |

| Constant | 2.082 | 0.551 | 8.019 |

| Log likelihood | -26.62227 | ||

| Pseudo R2 | 0.6875 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).