Submitted:

24 March 2025

Posted:

25 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

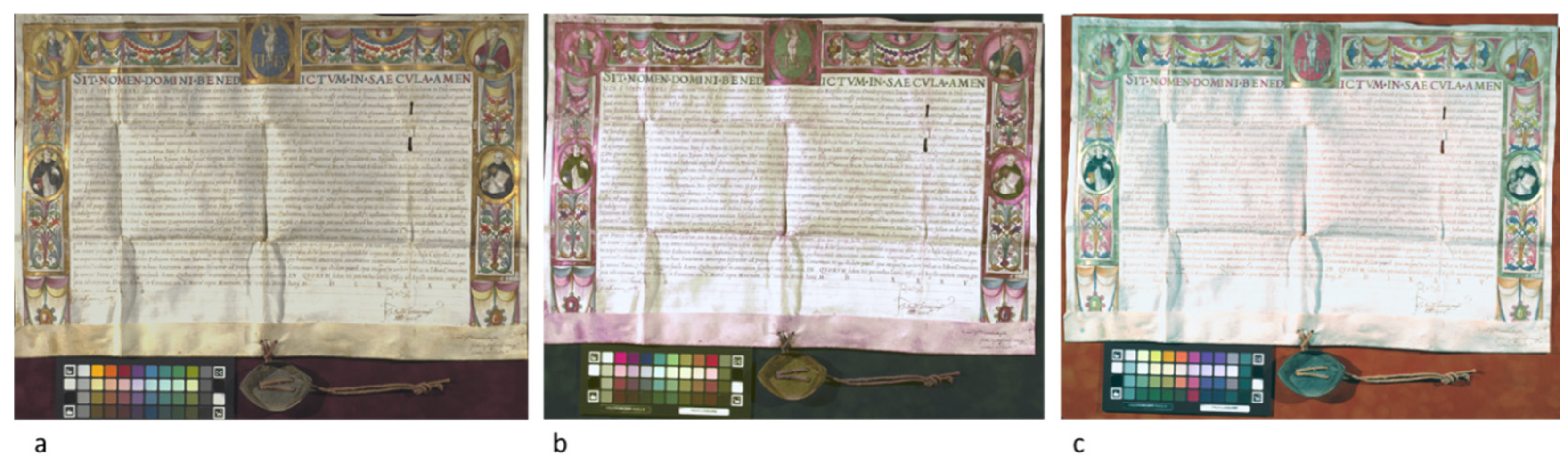

2.1. The Illuminated Parchment

- -

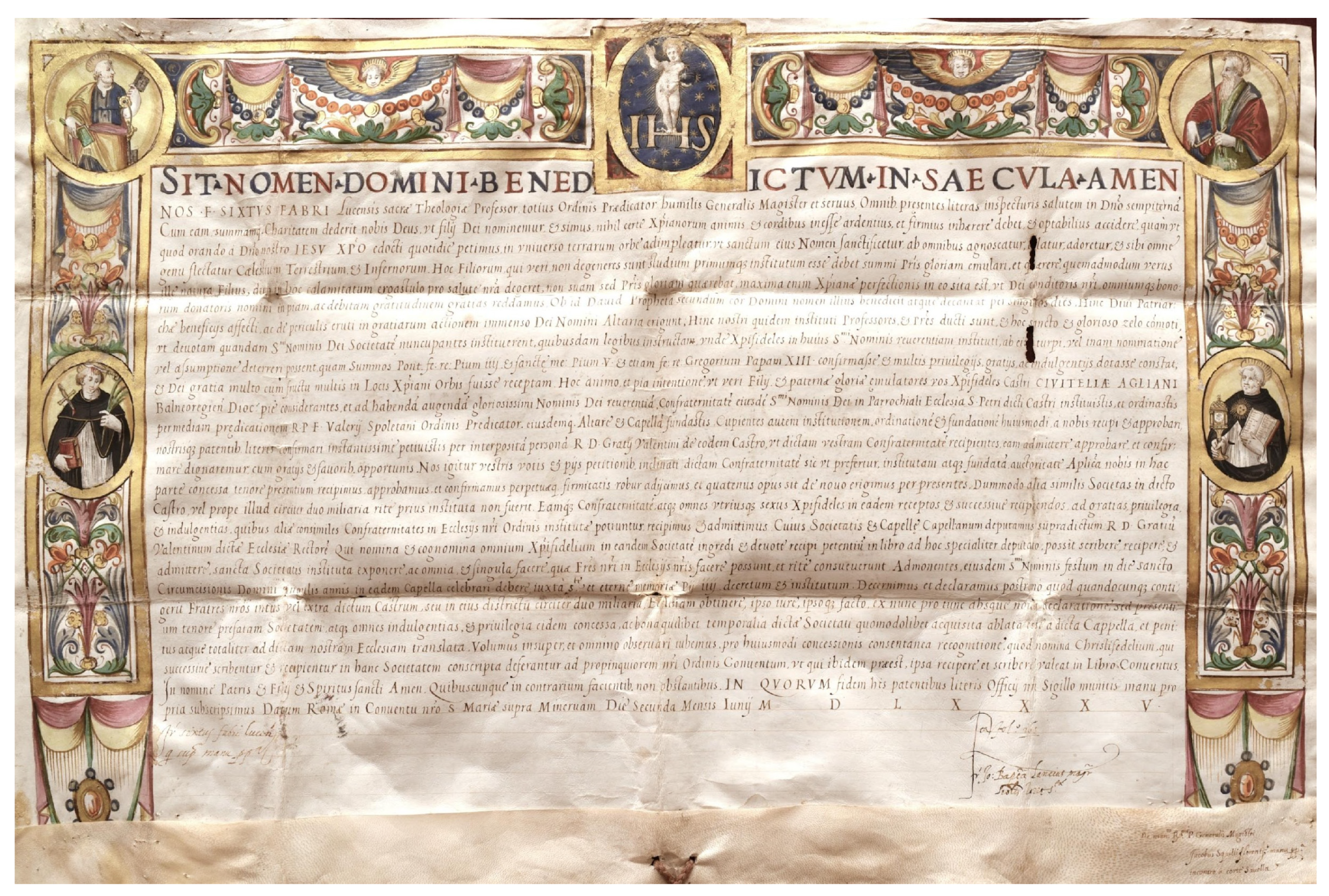

- the parchment is an important document from the Counter-Reformation period, where the strength of the orthodoxy of the Catholic Church expressed by the Dominican Order is highlighted, starting from the title (Sit Nomine Domini Benedictum in Saecula Amen; Be the Name of God Blessed Forever Amen).

- -

- the text indirectly retrieves the apprehension and insistence of the members of a small and recently established Brotherhood, the one of the Corpus Christi of Civitella di Agliano, who requested approval from the Dominicans. In fact, the members of the Brotherhood were worried of not having acted according to the expected rules, i.e. by asking the permission of the Dominicans.

- -

- the document, in response to the requests of the Brotherhood, is drawn up by Frater Sixstus Fabri Lucensis Generalis Magister of the Dominican Order and Professor of Theology. He confirmed the approval and guaranteed the authorization to constitute the Brotherhood through patentibus literis (the parchment itself), to build an altar and a chapel in the Church of San Pietro in Civitella d'Agliano in the Diocese of Bagnoregio.

2.2. Experimental Section

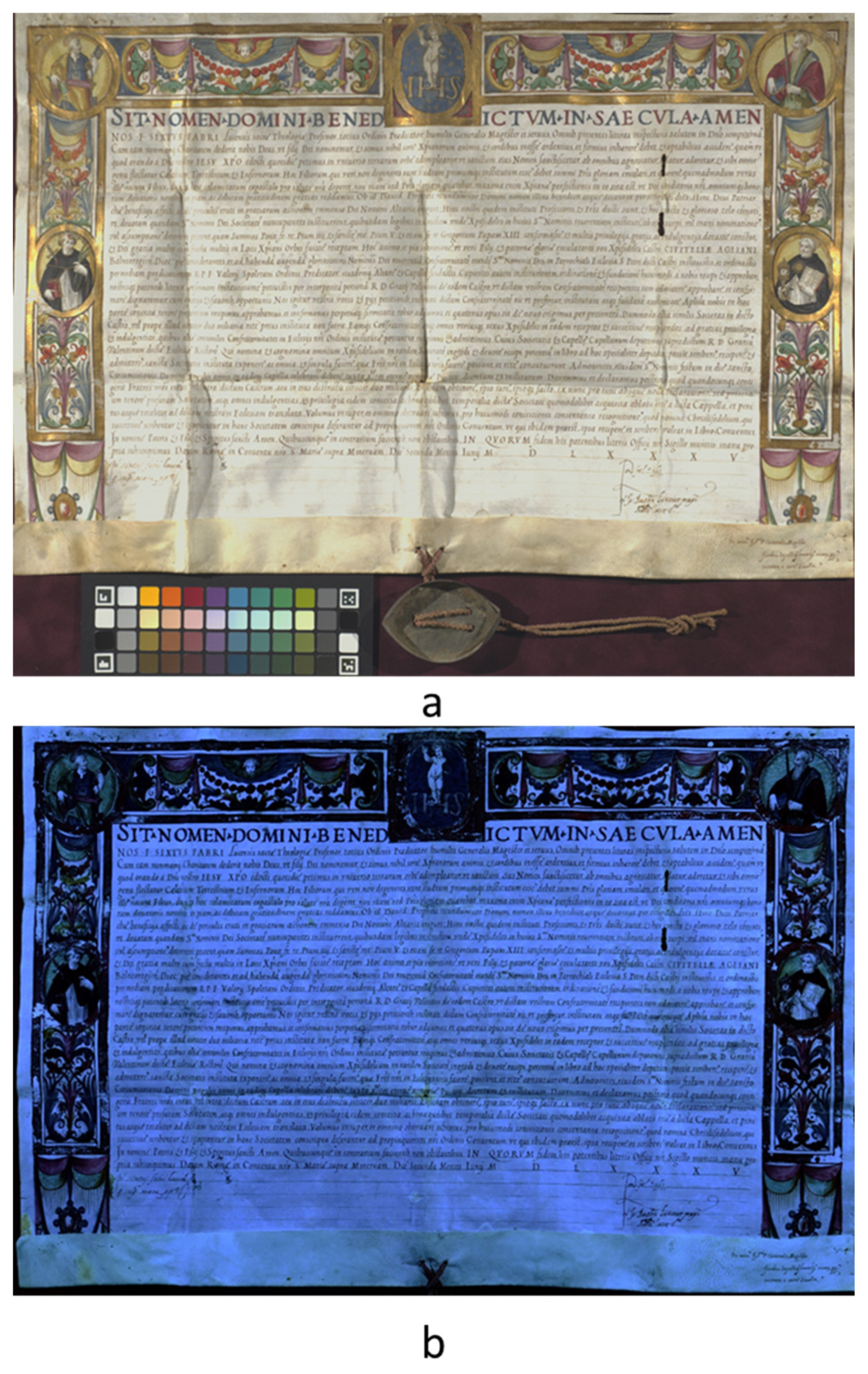

2.2.1. Hypercolorimetric Multispectral Imaging (HMI)

2.2.2. Infrared Reflectography in the 950-1700 nm Range

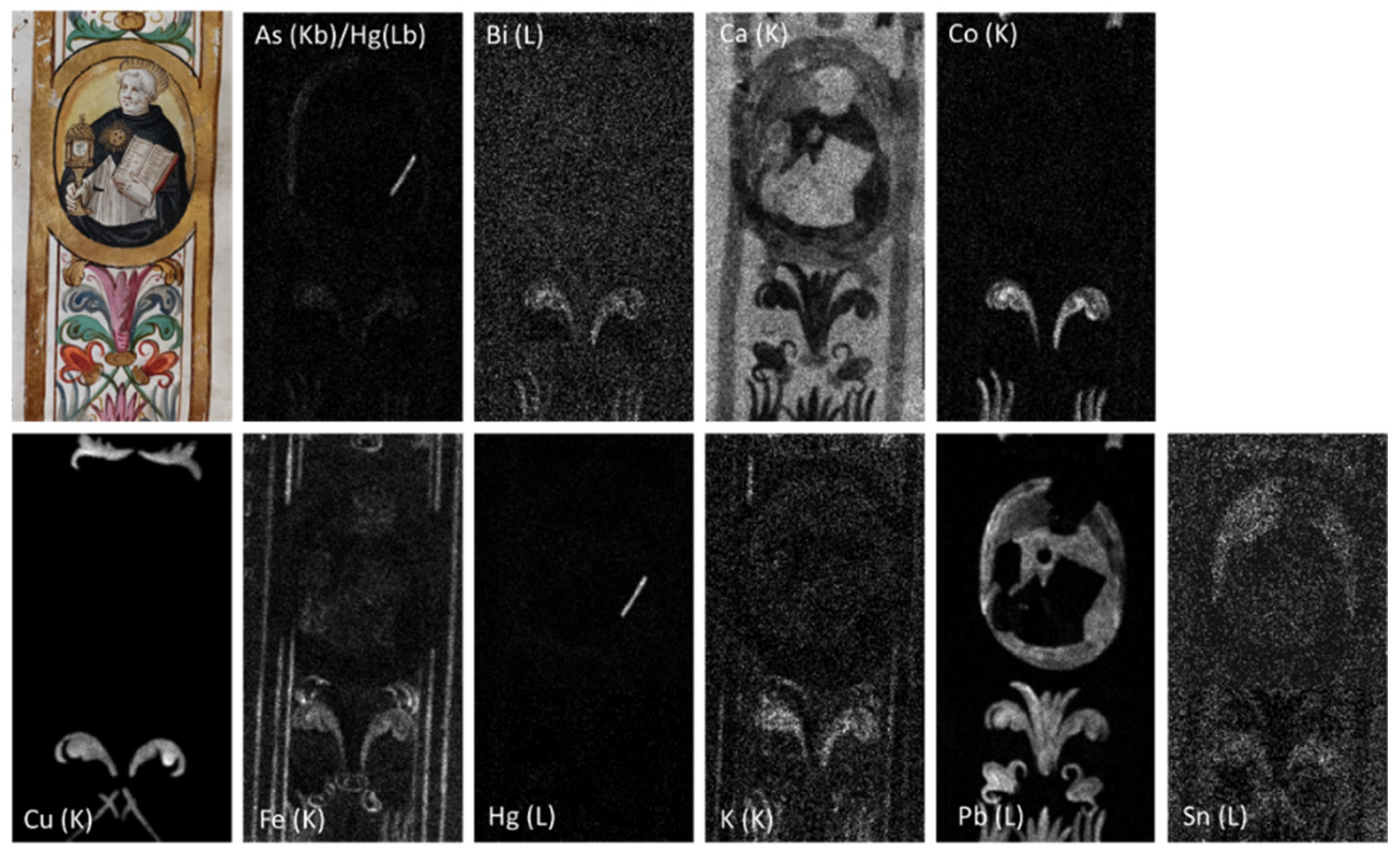

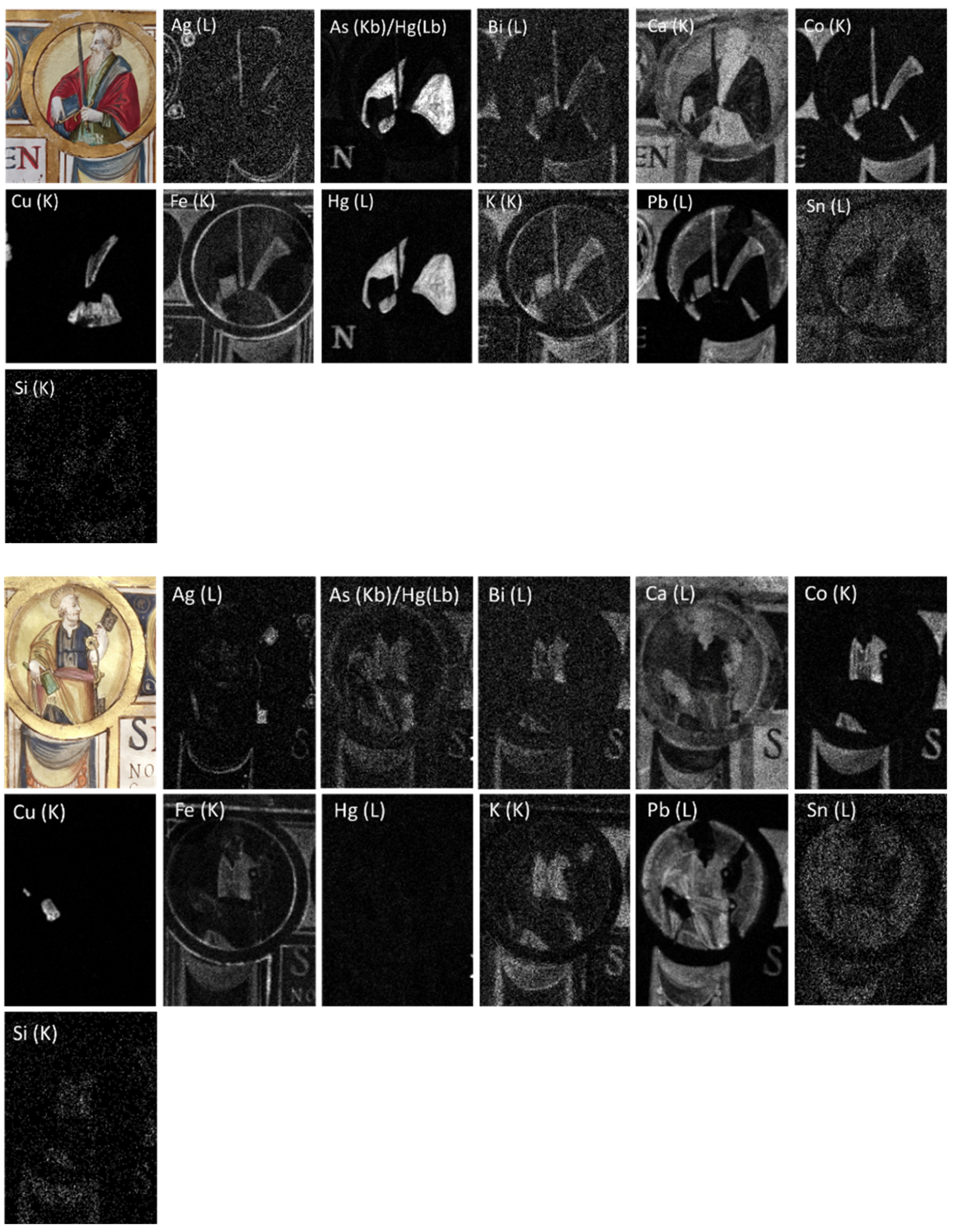

2.2.3. MA-XRF

- -

- For the illuminated parts: 38 kV anode voltage, 70 uA filament current, 10 mm/s scanning velocity and 0.5 mm step in both X and Y directions. Beam diameter on the sample surface ~1 mm, no He flow.

- -

- For the written part: 30 kV anode voltage, 95 uA filament current, 0.5 mm/s scanning velocity and 0.25 mm step in both X and Y directions. Collimator diameter 0.4 mm, no He flow.

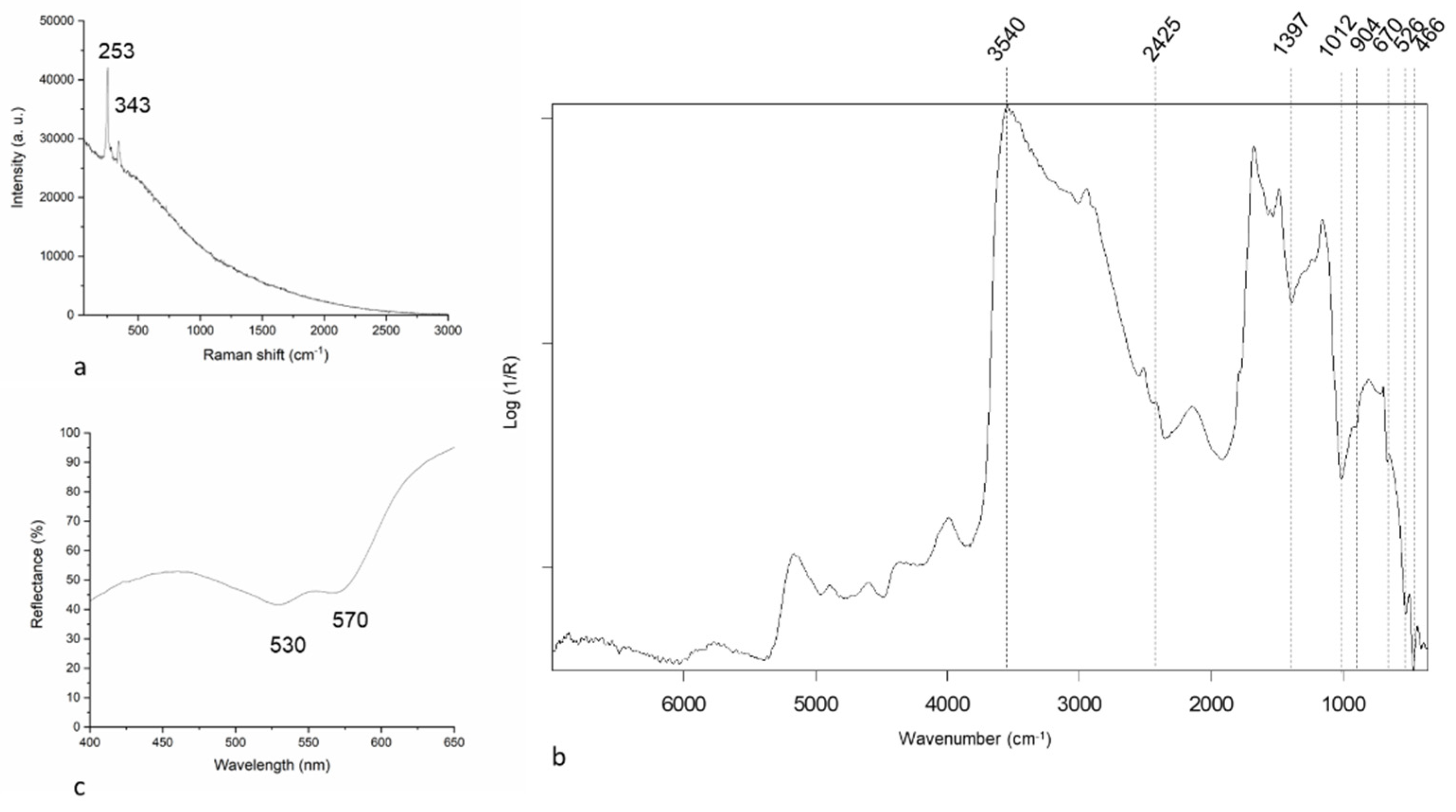

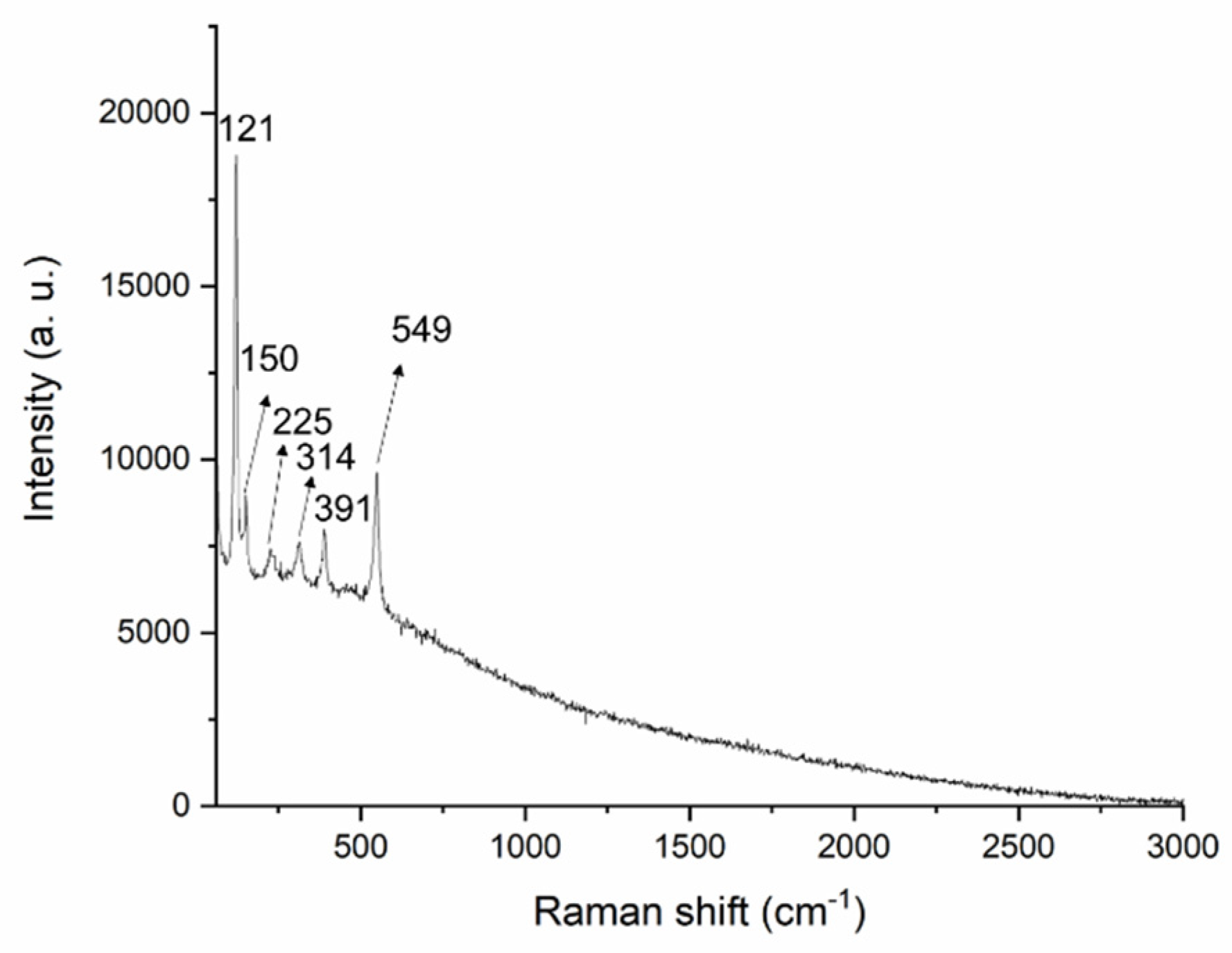

2.2.4. Raman Spectroscopy

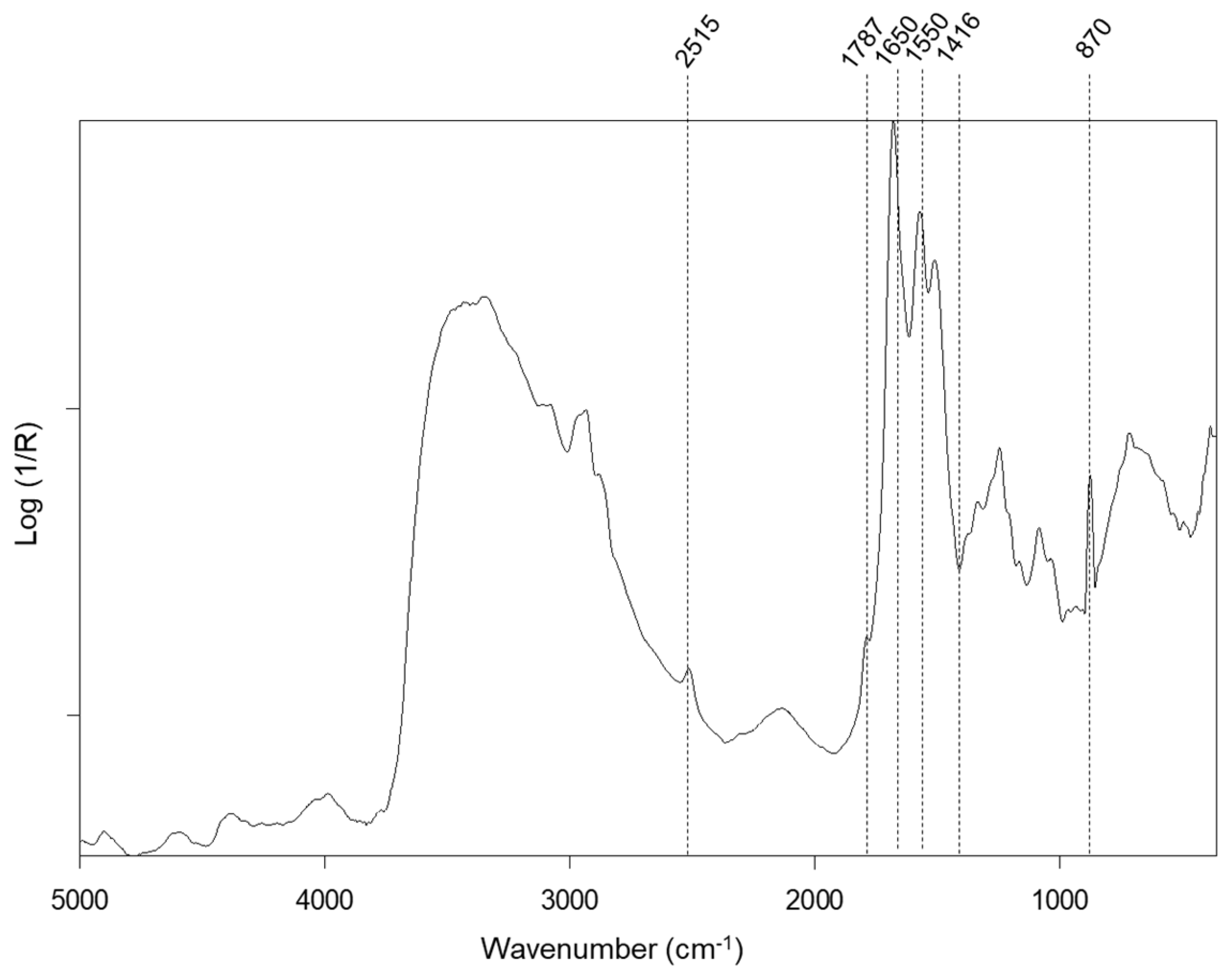

2.2.5. External Reflectance FT-IR (ER-FTIR) Spectroscopy

2.2.6. Optical Microscopy

2.2.7. Fiber Optic Reflectance Spectroscopy (FORS)

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Painting Technique

3.1.1. The Support

3.1.2. Underdrawings

3.2. Pigment Identification

3.3. Metal Layers

3.4. Written Text

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Pessanha, S.; Manso, M.; Carvalho, M.L. Application of spectroscopic techniques to the study of illuminated manuscripts: A survey. Spectrochim. Acta - Part B At. Spectrosc. 2012, 71–72, 54–61. [CrossRef]

- Chiriu, D.; Ricci, P.C.; Cappellini, G. Raman characterization of XIV–XVI centuries Sardinian documents: Inks, papers and parchments. Vib. Spectrosc. 2017, 92, 70–81. [CrossRef]

- Nodari, L.; Ricciardi, P. Non-invasive identification of paint binders in illuminated manuscripts by ER-FTIR spectroscopy: a systematic study of the influence of different pigments on the binders’ characteristic spectral features. Herit. Sci. 2019, 7. [CrossRef]

- Aceto, M.; Agostino, A.; Fenoglio, G.; Baraldi, P.; Zannini, P.; Hofmann, C.; Gamillscheg, E. First analytical evidences of precious colourants on Mediterranean illuminated manuscripts. Spectrochim. Acta - Part A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2012, 95, 235–245. [CrossRef]

- Vetter, W.; Latini, I.; Schreiner, M. Azurite in medieval illuminated manuscripts: a reflection-FTIR study concerning the characterization of binding media. Herit. Sci. 2019, 7, 1–9. [CrossRef]

- Edwards, H.G.M.; Vandenabeele, P.; Colomban, P. Analytical Raman Spectroscopy of Manuscripts and Maps: The Role of Inks. 2023, 215–231. [CrossRef]

- Pouyet, E.; Devine, S.; Grafakos, T.; Kieckhefer, R.; Salvant, J.; Smieska, L.; Woll, A.; Katsaggelos, A.; Cossairt, O.; Walton, M. Revealing the biography of a hidden medieval manuscript using synchrotron and conventional imaging techniques. Anal. Chim. Acta 2017, 982, 20–30. [CrossRef]

- Colantonio, C.; Clivet, L.; Laval, E.; Coquinot, Y.; Maury, C.; Melis, M.; Boust, C. Integration of multispectral imaging, XRF mapping and Raman analysis for noninvasive study of illustrated manuscripts: the case study of fifteenth century “Humay meets the Princess Humayun” Persian masterpiece from Louvre Museum. Eur. Phys. J. Plus 2021, 136, 958. [CrossRef]

- Cucci, C.; Delaney, J.K.; Picollo, M. Reflectance Hyperspectral Imaging for Investigation of Works of Art: Old Master Paintings and Illuminated Manuscripts. Acc. Chem. Res. 2016, 49, 2070–2079. [CrossRef]

- Titubante, M.; Giannini, F.; Pasqualucci, A.; Romani, M.; Verona-Rinati, G.; Mazzuca, C.; Micheli, L. Towards a non-invasive approach for the characterization of Arabic/Christian manuscripts. Microchem. J. 2020, 155, 104684. [CrossRef]

- Turner, N.K.; Patterson, C.S.; MacLennan, D.K.; Trentelman, K. Visualizing underdrawings in medieval manuscript illuminations with macro-X-ray fluorescence scanning. X-Ray Spectrom. 2019, 48, 251–261. [CrossRef]

- Mounier, A.; Le Bourdon, G.; Aupetit, C.; Belin, C.; Servant, L.; Lazare, S.; Lefrais, Y.; Daniel, F. Hyperspectral imaging, spectrofluorimetry, FORS and XRF for the non-invasive study of medieval miniatures materials. Herit. Sci. 2014, 2, 24. [CrossRef]

- Nastova, I.; Grupče, O.; Minčeva-Šukarova, B.; Ozcatal, M.; Mojsoska, L. Spectroscopic analysis of pigments and inks in manuscripts: I. Byzantine and post-Byzantine manuscripts (10-18th century). Vib. Spectrosc. 2013, 68, 11–19. [CrossRef]

- Mazzinghi, A.; Ruberto, C.; Castelli, L.; Ricciardi, P.; Czelusniak, C.; Giuntini, L.; Mandò, P.A.; Manetti, M.; Palla, L.; Taccetti, F. The importance of being little: MA-XRF on manuscripts on a Venetian island. X-Ray Spectrom. 2021, 50, 272–278. [CrossRef]

- Marucci, G.; Beeby, A.; Parker, A.W.; Nicholson, C.E. Raman spectroscopic library of medieval pigments collected with five different wavelengths for investigation of illuminated manuscripts. Anal. Methods 2018, 10, 1219–1236. [CrossRef]

- Faubel, W.; Staub, S.; Simon, R.; Heissler, S.; Pataki, A.; Banik, G. Non-destructive analysis for the investigation of decomposition phenomena of historical manuscripts and prints. Spectrochim. Acta Part B At. Spectrosc. 2007, 62, 669–676. [CrossRef]

- Melis, M.; Miccoli, M.; Quarta, D. Multispectral hypercolorimetry and automatic guided pigment identification: some masterpieces case studies. Opt. Metrol. 2013, 8790, 87900W. [CrossRef]

- Melis, M.; Miccoli, M.; Srl -Roma, P. Trasformazione evoluzionistica di una fotocamera reflex digitale in un sofisticato strumento per misure fotometriche e colorimetriche (oral).

- Laureti, S.; Colantonio, C.; Burrascano, P.; Melis, M.; Calabrò, G.; Malekmohammadi, H.; Sfarra, S.; Ricci, M.; Pelosi, C. Development of integrated innovative techniques for paintings examination: The case studies of The Resurrection of Christ attributed to Andrea Mantegna and the Crucifixion of Viterbo attributed to Michelangelo’s workshop. J. Cult. Herit. 2019, 40, 1–16. [CrossRef]

- Annarilli, S.; Casoli, A.; Colantonio, C.; Lanteri, L.; Marseglia, A.; Pelosi, C.; Sottile, S. A Multi-Instrument Analysis of the Late 16th Canvas Painting, “Coronation of the Virgin with the Saints Ambrose and Jerome”, Attributed to the Tuscany-Umbria Area to Support the Possibility of Bio-Cleaning Using a Bacteria-Based System. Herit. 2022, Vol. 5, Pages 2904-2921 2022, 5, 2904–2921. [CrossRef]

- Bonizzoni, L.; Caglio, S.; Galli, A.; Lanteri, L.; Pelosi, C. Materials and Technique: The First Look at Saturnino Gatti. Appl. Sci. 2023, Vol. 13, Page 6842 2023, 13, 6842. [CrossRef]

- Taccetti, F.; Castelli, L.; Czelusniak, C.; Gelli, N.; Mazzinghi, A.; Palla, L.; Ruberto, C.; Censori, C.; Lo Giudice, A.; Re, A.; et al. A multipurpose X-ray fluorescence scanner developed for in situ analysis. Rend. Lincei 2019, 30, 307–322. [CrossRef]

- Panayotova, S. The art & science of illuminated manuscripts : a handbook. 2020, 528.

- Siidra, O.; Nekrasova, D.; Depmeier, W.; Chukanov, N.; Zaitsev, A.; Turner, R. Hydrocerussite-related minerals and materials: structural principles, chemical variations and infrared spectroscopy. Acta Crystallogr. B. Struct. Sci. Cryst. Eng. Mater. 2018, 74, 182–195. [CrossRef]

- Mozgawa, W.; Handke, M.; Jastrzebski, W. Vibrational spectra of aluminosilicate structural clusters. J. Mol. Struct. 2004, 704, 247–257. [CrossRef]

- Cosentino, A. EFFECTS OF DIFFERENT BINDERS ON TECHNICAL PHOTOGRAPHY AND INFRARED REFLECTOGRAPHY OF 54 HISTORICAL PIGMENTS. 2015.

- Boust, C.; Wohlgelmuth, A. DATABASE : Pigments under UV and IR radiations. Sci. imaging Cult. Herit. 2017.

- Ricciardi, P.; Dooley, K.A.; Maclennan, D.; Bertolotti, G.; Gabrieli, F.; Patterson, C.S.; Delaney, J.K. Use of standard analytical tools to detect small amounts of smalt in the presence of ultramarine as observed in 15th - century Venetian illuminated manuscripts. Herit. Sci. 2022, 1–18. [CrossRef]

- Dehaine, Q.; Tijsseling, L.T.; Glass, H.J.; Törmänen, T.; Butcher, A.R. Geometallurgy of cobalt ores: A review. Miner. Eng. 2021, 160, 106656. [CrossRef]

- Nimis, P.; Costa, L.D.; Guastoni, A. Cobaltite-rich mineralization in the iron skarn deposit of Traversella (Western Alps, Italy). Mineral. Mag. 2014, 78, 11–27. [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, U.P. Analysis of Cellulose and Lignocellulose Materials by Raman Spectroscopy: A Review of the Current Status. Mol. 2019, Vol. 24, Page 1659 2019, 24, 1659. [CrossRef]

- Luiza Queiroz Brian M Kerins Jayprakash Yadav Fatma Farag Waleed Faisal Mary Ellen Crowley Simon E Lawrence Humphrey A Moynihan Anne-Marie Healy Sonja Vucen Abina M Crean, A.P.; P Queiroz Á B M Kerins Á F Farag Á W Faisal Á M E Crowley Á S Vucen Á A M Crean, A.L.; Yadav Á A-M Healy, J.; Lawrence Á H A Moynihan, S.E. Investigating microcrystalline cellulose crystallinity using Raman spectroscopy. Cellulose 2021, 28, 8971–8985. [CrossRef]

- Henrist, C.; Traina, K.; Hubert, C.; Toussaint, G.; Rulmont, A.; Cloots, R. Study of the morphology of copper hydroxynitrate nanoplatelets obtained by controlled double jet precipitation and urea hydrolysis. J. Cryst. Growth 2003, 254, 176–187. [CrossRef]

- Zhan, Y.; Zhou, X.; Fu, B.; Chen, Y. Catalytic wet peroxide oxidation of azo dye (Direct Blue 15) using solvothermally synthesized copper hydroxide nitrate as catalyst. J. Hazard. Mater. 2011, 187, 348–354. [CrossRef]

- Bushong, E.J.; Yoder, C.H. The Synthesis and Characterization of Rouaite, a Copper Hydroxy Nitrate. An Integrated First-Year Laboratory Project. J. Chem. Educ. 2009, 86, 80–81. [CrossRef]

- Purdy, E.H.; Critchley, S.; Clément Holé, ·; Cotte, · Marine; Kirkham, A.; Casford, · Michael; Holé, C.; Cotte, M. Characterisation of rouaite, an unusual copper-containing pigment in early modern English wall paintings, by synchrotron micro X-Ray diffraction and micro X-Ray absorption spectroscopy. Appl. Phys. A 123AD, 130. [CrossRef]

- Purdy, E.H.; Critchley, S.; Kirkham, A.; Casford, M. Illuminating the problem of blue verditer synthesis in the early modern English period: chemical characterisation and mechanistic understanding. [CrossRef]

- Fanost, A.; Gimat, A.; de Viguerie, L.; Martinetto, P.; Giot, A.C.; Clémancey, M.; Blondin, G.; Gaslain, F.; Glanville, H.; Walter, P.; et al. Revisiting the identification of commercial and historical green earth pigments. Colloids Surfaces A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2020, 584, 124035. [CrossRef]

- Burgio, L.; Manca, R.; Browne, C.; Button, V.; Horsfall Turner, O.; Rutherston, J. Orange for gold? Arsenic sulfide glass on the V&A Leman Album. J. Raman Spectrosc. 2019, 50, 1169–1176. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).