1. Introduction

The ever-increasing population growth, industrialization, economic growth, and as well rural to urban migration attributed to the generation of high volume of waste materials deposited on landfills, water ways and roads sites in an uncontrolled manner which in turn leads to significant environmental, economic and social challenges with a trend that will not be good for the future, couple with fossil fuel and gases emission from the industries during production processes (Gallardo et al., 2014; Hoornweg and Bhada-Tata, 2012; Onyanta, 2016; Zhou et al., 2016). However, the major cause of environmental challenges is the industrialization, urbanization and population growth. This signifies that, there is urgent need to intensifies recycling and transforming MSW into alternate source of energy, which will go a long way to lessen the gas emission to the environment.

As reported by worldometer (2023), that the world population hit up to 8.1 billion in 2023 and is expected to increase to 9 billion and 10 billion in the years 2037 and 2058, respectively. Thus, necessitate the increased in the demands for food, clothes, shelters and energy, as such generate solid wastes which emit gases to the environment couple with 84% of global energy sources were derived from fossil fuels, which releases greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions and CO2 emissions that causes ozone layer depletion, climate change, rise in sea level. Therefore, the world is looking for an alternative source of energy to meet the energy demand and replace fossil-based fuels in the future and this can only be achieved through intensive use of MSW in bio-energy generation.

Municipal solid waste (MSW) is solid waste materials discarded by the inhabitants of a given area, thus causing a negative impact on the environment. Statista (2023) reported that the generation of MSW across the globe is projected to increase by 70% and reach 3.40 billion tonnes by 2050, this is alarming because the increased rate of MSW supersede the projected rate of population growth at the same time. Thus, about 0.79 kg of solid waste is generated per capita per day (World Bank, 2020; Ayuba et al., 2013; Bakare, 2018). Therefore, there is a serious challenge in the effective management of this huge amount of waste because out of the total wastes generated, more than 70% are discarded on landfills, while 19% is recycled and only 11% is used for various energy recovery processes. Similarly, Sarigiannis et al., (2021) reported that 80% of MSW remains on the landfills, 15% is recycled, about 4.1% is composted and less than 1.1% of the MSW is used for energy recovery in Greece. Meanwhile, the deposited solid wastes in one place undergoes chemical and physical transformations thereby emitting greenhouse gases over time (Nascimento et al., 2015a; Chonattu et al., 2016). Similarly, Ngwabie et al. (2019) revealed that open dumping of MSW has high potential of releasing greenhouse gas emission into the atmosphere and polluting the environment. Moreover, MSW disposal has the potential of affecting the four main spheres of the environment, which are atmosphere, hydrosphere, lithosphere, and ultimately biosphere directly or indirectly (Butt et al., 2016).

In view of the challenges of MSW to the environment, it is imperative to reduce the volume of MSW through robust transformation into solid bio-fuels and other source of energy to minimize the environmental challenges caused by the MSW disposals (Loo and Koppejan 2008; Vasileiadou et al., 2021a). Meanwhile, solid biofuel is a renewable energy that is derived from nonfossil, organic materials, including municipal waste, plant and animal wastes which is densified and used as an alternate source of energy for heating, cooking, and electricity generation. MSW can be transformed into solid bio-fuels and use as a substitute for fossil fuel.

Many researchers have reported that solid bio-fuels produced from MSW provide high quality in terms of calorific value (Tumurulu et al., 2021; Vasileiadou et al., 2022; Ganeson and Vedagiri, 2023). Similarly, MSW briquettes made from mixtures of food and wood waste have greater calorific value of 22.53 MJ/kg, less moisture content of 6.1%, fewer emissions, and greater durability than coal (Ifa et al. 2020; Li et al. 2023). However, Krizan et al., (2011) reported that briquetting of MSW blend with organic binder greatly influence the quality. Thus, MSW has great energy potential resources due to the present of combustible materials in it (Aluri et al., 2018 and Hasan et al., 2021). Afterward, higher thermal resistance and longer conversion times was observed in a MSW pellets compared to biomass (Zhou et al., 2018). Although, the effect of pelletization on the pyrolysis process of MSW pellets have been less studied, with existing studies on MSW pyrolysis primarily focusing on MSW powder (Fernandez et al., 2020; Song et al., 2020; Bin et al., 2022).The quality, quantity and leachates of MSW vary from one region to another and depend on the climate and socioeconomic conditions (Zhu et al. 2021). Conservely, Matli et al. (2019) studied the physico chemical characteristics which includes the higher heating value, ash content and gas emissions (CO2, SO2, NOx, in kg/d) of MSW co-firing with Indian coal either including the food waste or without food waste and concluded that co-combustion with coal is an efficient process for the utilization of MSW. Similarly, Suksankraisorn et al. (2010) studied the high moisture content of MSW in co-firing with Thai lignite in fluidized bed and concluded that SO2 emissions are lower for lower waste moisture.Vamvuka et al. (2015) studied blends of 50% urban wastes (MSW and waste paper) and 50% lignite using several methods including TG/MS analysis and concluded that co-firing of such blends is an attractive approach.

2. Materials and Methods

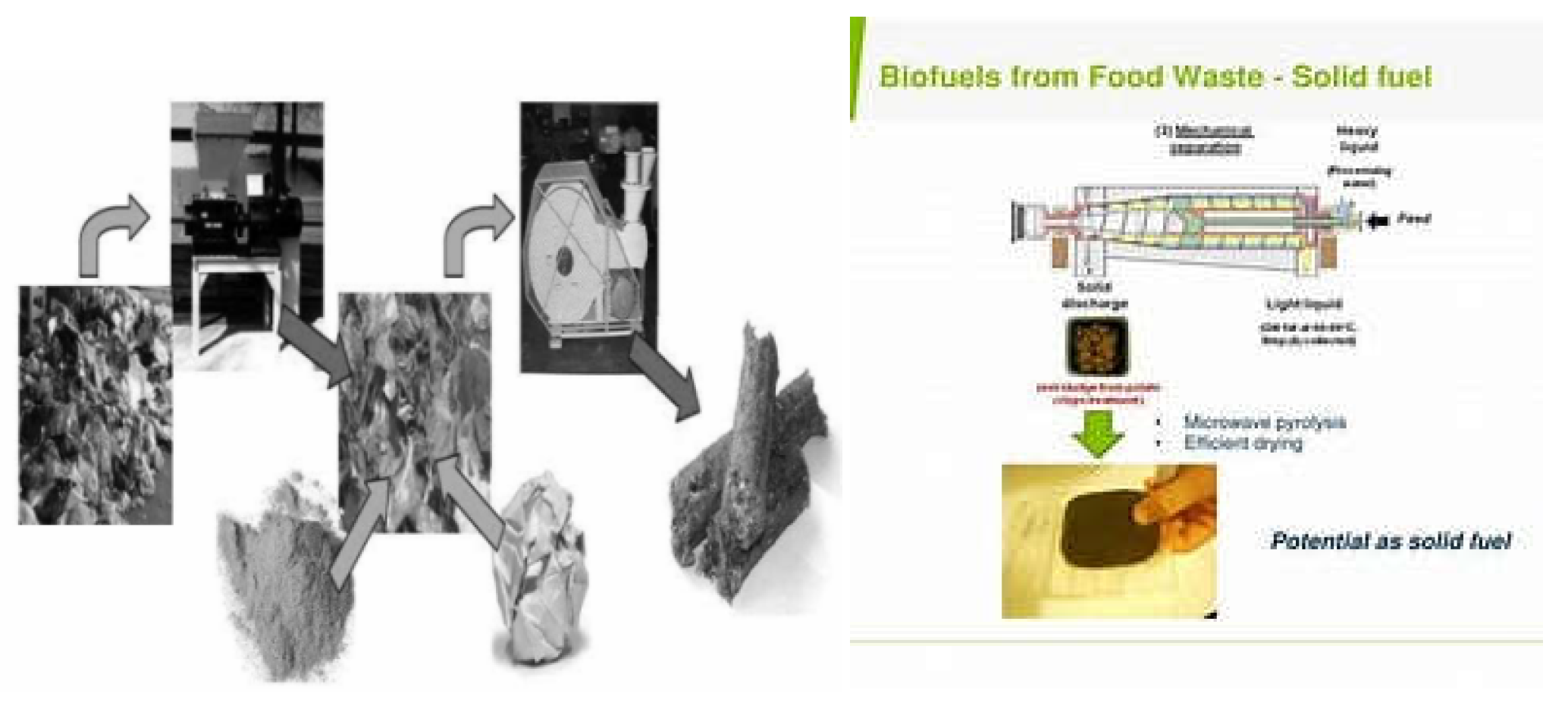

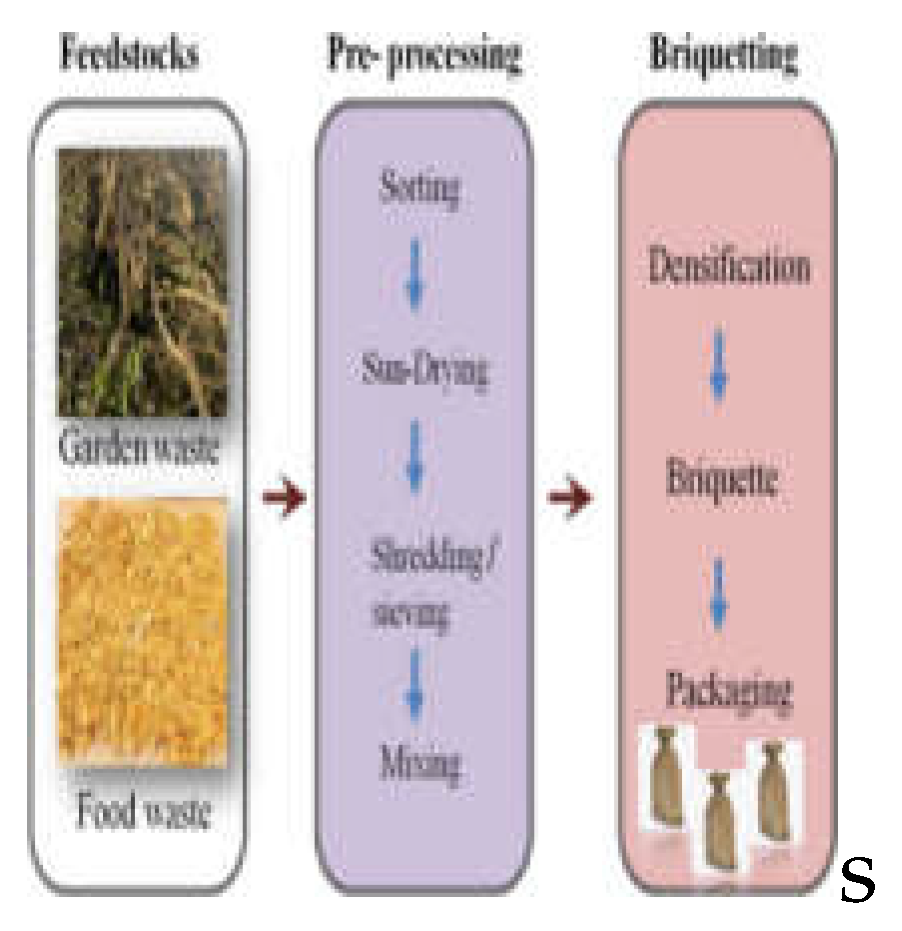

The materials used in this study includes the waste of coconut (fibre, husk and shell), Food waste, sawdust (Nikiema et al., 2022), MSW which consist of 30% plastic, 60% paper and non-corrugated cardboard, and 10% textile material (Tumurulu et al., 2021), MSW material used by Poespowati and Mustiadi, (2012) constitutes waste of fruit, vegetable, paper, plastic, glass, metal, wood, leaf, and other materials (Cassava starch, molasses, and clay were used as binders) and Ganesan and Vedagiri, (2024), uses firewood, sawdust and MSW consists of food waste and garden waste which were subjected to milling process, drying and densification.

Densified fuel obtained from MSW is called refuse-derived fuel (RDF) such as briquette or pellet. The production process involves a series of activities that includes collection, drying, crushing, mixing, and pressing along with constant energy supply (Sarquah et al., 2022). The feed stock were mixed and weighed at desired ratio and compressed under high pressure in machine and the briquettes acquires the shape of the cylinder passing through (Okwu et al. 2022; Ifa 2019),

Figure 1 and

Figure 2 illustrates the phases in briquetting process and the physical properties were determined using ASTM standard test method.

2.1. Determination of the MSW Briquettes Physical Properties

According to ASTM (American Society for Testing and Materials) D1762-84, the physical qualities that are examined include moisture content, volatile matter, fixed carbon, and Ash content.

2.2. Moisture Content

The moisture content is a ratio of the initial dry weight minus the final weight to the final weight of the solid fuel by 100% is known as the moisture content. The moisture content has a significant impact on the briquettes burning characteristics, preservation, and density endurance. The biomass was dried in a hot air oven at 105 ± 1°C to assess its moisture content, and the weight loss was recorded. The process was carried out until a constant weight is attained. The equation (1) below was used to present the moisture content.

where,

MC moisture content of sample (%), Mo mass of sample before drying (g) and Ma mass of sample after drying in oven (g).

2.3. Volatile Matter

The biofuel’s volatile matter demonstrates the carbon, oxygen, and hydrogen. As biomass remains more explosive than coal and charcoal, it burns more quickly than coal. The quantity of explosive components increases with the rate of combustion. The briquette is ground into fne particles weighing approximately 2g±0.02 mg and placed in a sealed crucible until a consistent mass is achieved. Subsequently, the briquette sample is heated in a muffle furnace at a temperature of 950 °C±10 °C for 10 min and then weighed after cooling (Nganko et al. 2024). Equation (2) is used to calculate VM, which is expressed in %.

where,

M1 mass of empty crucible in grams (g), M2 mass of empty crucible with sample in grams (g), M3 mass of sample in grams after heating in grams (g).

2.4. Ash Content

The biofuel’s ash content was determined by subjecting 2g fractions of the biofuels into a crucible of known weight and heated for 30 min at temperature of 700

oC + 50

oC in a muffle furnace (ASTM D- 3174). after that, the sample were removed and allow to cool in a dessicator and weight until constant weight is attained. Ash content (AC) is calculated using Eq. (3), and it is a byproduct that is formed when solid fuel is heated in a boiler to a constant weight.

where,

AC sample’s ash content (%), Wa weight of ash remaining (g) and Wd weight of dried sample (g).

2.5. Fixed Carbon

The amount of carbon in the biomass that remains usable for burning after the volatile matter has been completely escaped is referred to as fixed carbon and is measured in percentage (%). It was determined using the equation (4) (García et al. 2012).

2.6. Density

The density was determined by obtaining the mass of the MSW solid biofuels using electric weighing balance divided by its volume. Meanwhile, the volume was determined by measuring the diameter and height of the sample using vernier caliper made of stainless steel (Dao et al. 2022) and substituted the values in the equation (5) .

2.7. Higher Heating Value

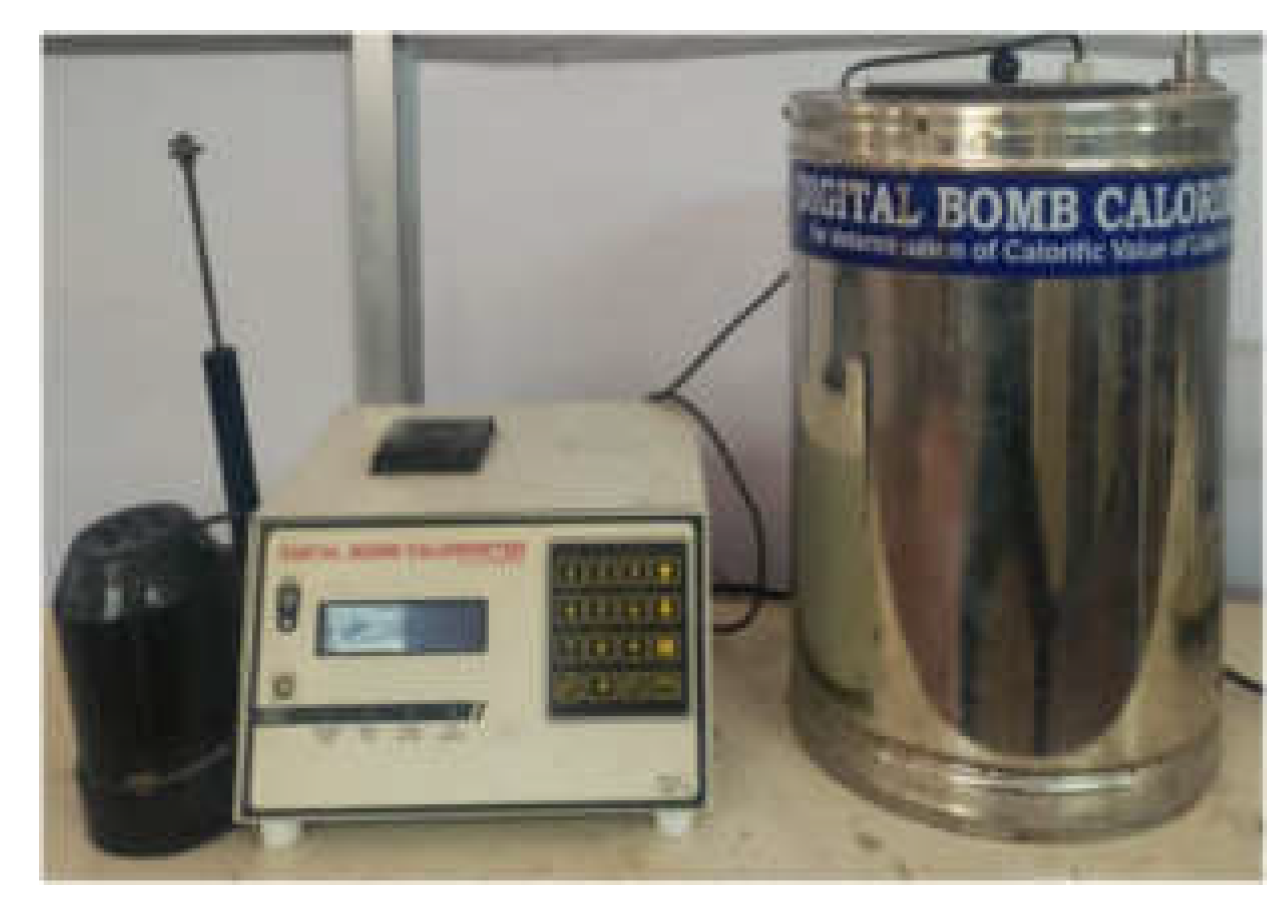

The maximum amount of energy output that may be anticipated per mass basis is indicated by the calorifc content, which is designated as higher heating value (HHV). Bomb calorimeter shown in Fig. 3 is the accepted method for determining calorifc value under pressure and in an oxygen rich atmosphere. It is a critical determinant whether biomass is a suitable fuel and a necessary component for thermal and electrical production systems. Following the ASTM guidelines, the calorifc values of feedstocks and MSW briquette were measured using a bomb calorimeter (ASTM International 2004; Trombley et al. 2023) automatically.

Figure 3.

Bomb calorimeter.

Figure 3.

Bomb calorimeter.

Figure 4.

Flue gas analyser- A DIGAS 444 N.

Figure 4.

Flue gas analyser- A DIGAS 444 N.

3. Results and Discussion

The results of the proximate analysis of MSW briquettes from various authors was presented in

Table 1. The moisture content of MSW briquettes were compared with other biofuels and observed that, higher MC of 70.60, 32.60 and 31.80% were obtained from firewood, coconut fibre and coconut husk respectively (Nikiema et al., 2022). High moisture content in briquette negatively affects energy yield (Afsal et al., 2020; Krajnc, 2015) and the results of this study proven that high MC lowered the heating value and risen the density of the briquette. Conversely, increased in MC up to 18% lower the density of briquette made from lodgepole pine (Zhang and Guo, (2014)). Meanwhile, lower MC were found in sawdust, firewood and MSW briquettes with a values of 5.40, 5.98 and 6.10% respectively (Ganesan and Vedagiri, 2024) and this falls within the ranged of 5 to 10% (Bot et al. 2021). Consequently, they will be optimal for the briquette’s combustibility, strength, storage and as well indicating good quality briquettes. However, 15% MC was reported to the best conditions for producing corn-stover, switchglass and lodgepole pine briquettes (Tumurulu, 2018).

The ash content was observed to be higher in charcoal fines and MSW briquettes as reported by Nikiema et al., (2022) and Tumurulu et al., (2021). This indicates that the material is not suitable for quality briquettes but can be blend with other feedstock to make quality briquette because charcoal has high ash content in it which make it to burn slowly, likewise the MSW briquette the high ash observed may be attributed to decomposion and bulk density of the material used. Although, Other studies conducted with FW mixed with FS, such as by Kizito et al. (2022), report high ash values, in the range of 30.4%. However, low ash content ranged between 0.40 to 6.10% were found in both studies (

Table 1), this indicates good quality briquettes which is consistent with the ranges of high quality briquette (1.0% to 12%) as reported by Akolgo et al. (2021), that ash concentrations were comparatively low and inhibition to combustion at 4.12%. At low ash percentage, high volatile matter causes high combustibility. This outcome indicates that when the MSW briquettes burn, a strong combustion will be produced and thereby can replace charcoal, coal, and wood as a source of energy for cooking, heating and steaming.

The higher percentage volatile mater in solid fuels indicates that the materials contain sufficient amount of carbon (57.0%) and oxygen (39.20%) that can lit easily and other elements like potassium (Ganesan and Vedagari, 2024). The higher volatile matter observed in this review (

Table 1) consistently with the report of Ajimotokan et al. (2019). Increase in carbon content indicates fixed carbon compositions and calorifc values in the MSW briquettes which increases the energy-efficiency as the carbonization process occurred at a high temperature (Zinla et al. 2021; Ofori 2020). The percentage fixed carbon of MSW briquettes are found to be 8.14 to 19.21% (

Table 1), this is in close range the with report of Mfomo et al. (2020), that the amount of fixed carbon in the MSW briquettes was 18.85%, indicating that the fuel had solid carbon accessible and quickly transfer heat to the briquettes’ surface. Meanwhile other materials ranged from 9.40 to 49.80% (Nikiema et al., 2022). Thus, the higher heating value or calorific value has direct relationship with the amount of fixed carbon in the fuel. Meanwhile the calorific values of MSW briquettes are higher than other sources of energy with a range of values between 18.50 to 49.55 KJ/g and this indicates the substantial energy potentials compared to other sources with a range of values between 17.60 to 18.90 KJ/g respectively (

Table 1). The HHV of the MSW briquettes falls within the permissible range of values observed for other wastes (Erol et al. 2010; Setter et al. 2021).

The flue gas emission of MSW briquettes results obtained from the available studied reviewed in this work reveals acceptable ranges as recommended by ISO 16994 (2015), National institute for occupational safety and health (NIOSH) and world health organization (WHO) that the gas emission should not exceed the limit of 99 ppm and 35 µg/m3 for a 24-h period in order to safeguard the environment and public health. The CO2 gas emission MSW briquettes ranged from 0 - 23.97 % and this is an indication that, the fuel is completely burned. While, CO gas emission MSW briquettes ranged between 0 - 2.55 % which is lower than firewood and sawdust briquettes. However, it is below the emission limit recommended by ISO 16994 (2015) and world health organization (WHO) of 7 mg/m2. Similarly, MSW briquettes produced by Maninder et al., (2012); Ifa et al. (2020); Li et al. (2023) were reported to have less flue gas emission compared to sawdust briquette due to its oxygen inhibition in the production of smoke. Conversely, Otieno et al. (2022) observed that burning of charcoal and firewood briquettes produced more than 35ppm CO concentration threshold which is harmful to human health.

Table 2.

AVL DIGAS 444 N flue gas analyzer specification.

Table 2.

AVL DIGAS 444 N flue gas analyzer specification.

| Specification |

Emission Limit (%) (Ganesan & Vedagiri, 2024) |

Emission Limit (%) (Poespowati and Mustiadi, 2012) |

Emission Limit (%) (Nikiema et al., 2022) |

| O2 |

0-15 |

2.5 – 5.88 |

- |

| CO2 |

0-20 |

1.63 – 5.75 |

5.91–23.97 |

| CO |

0-10 |

0.06 – 2.0 |

0.14 - 2.55 |

| NOx |

0-5000 ppm |

78.38 – 84.06 (N2) |

0.75–1.50 |

| Hydrocarbon (HC) |

0-25000 ppm |

- |

4.33–41.75 |

4. Conclusion and Recommendation

Based on the clear evidence and proofs from various studies justified that MSW has the energy potential and quality for use as an alternate source of energy for cooking, heating and electricity generation. Therefore, it is imperative to adopt the use of MSW as a feedstock for solid biofuel production in the various factories and industries that are using other sources of feedstock for the production of briquettes and pellets. Thus, this will go a long way in protecting environment from greenhouse gas emission challenges as was clearly proven that MSW briquette produce less flue gas emission and possessed good quality better than firewood, coal and sawdust briquettes which can used indoor with out causing more harm to human health.

It is recommended that government, non governmental organization, individuals should collective support the recircling and transformation of MSW into valuable products such as bio-fuel production. As many countries and cities around the world faced with a serious environmental challenges in one way or the other, which is directly or indirectly caused by anthropogenic activities such industrialization, population growth, fossil fuel utilization and improper disposal of municipal solid wastes, thus causes a lot of environmental degradation. However, with collective efforts of imposing proper disposal and incorporation of MSW as a feedstock in the production of solid biofuels will drastically reduced the environmental challenges. However, in the case of desert areas where vegetation are scarsed and scattered couple with high exploitation of forest resources for firewood and charcoal production as a source of energy for cooking, heating and steaming also contribute a lot to the environmental challenges and as well the presence of abundance and improper disposal of municipal solid wastes. These have significantly contributes to the climate change, global warming effects and other environmental challenges but with this study the intensity of greenhouse gas emission can be subdue by proper management and incorporating MSW in the production of solid biofuel due to its proven energy potential and quality.

References

- Afsal, A., David, R., Baiju, V., Suhail, N.M., Parvathy, U., Rakhi, R.B (2020) Experimental investigations on combustion characteristics of fuel briquettes made from vegetable market waste and saw dust. Mater. Today: Proc. 33 (7), 3826–3831. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matpr.2020.06.222. [CrossRef]

- Akolgo, G.A., Awafo, E.A., Essandoh, E.O., Owusu, P.A., Uba, F., Adu-Poku, K.A (2021) Assessment of the potential of charred briquettes of sawdust, rice and coconut husks: using water boiling and user acceptability tests. Sci. Afr. 12, e00789. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sciaf.2021.e00789. [CrossRef]

- Aluri, S., Syed, A., Flick, D.W., Muzzy, J.D., Sievers, C., Agrawal, P.K (2018) Pyrolysis and gasification studies of model refuse derived fuel (RDF) using.

- thermogravimetric analysis, Fuel Process. Technol. 179, 154–166, https://doi.org/10.1016/j. fuproc.2018.06.010. [CrossRef]

- ASTM Standard E711–87 (2004) standard test method for gross calorifc value of.

- refuse derived fuel by the bomb calorimeter. ASTM International.

- ASTM Standard D3174-12 (2018) Standard Test Method for Ash in the Analysis Sample of Coal and Coke from Coal. ASTM Internation,West Conshohocken, PA. https://doi.org/10.1520/D3174-12R18E0. www.astm.org. [CrossRef]

- ASTM Standard D3175-20 (2017) Standard Test Method for Volatile Matter in the Analysis Sample of Coal and Coke. ASTM Internation, West Conshohocken, PA. https://doi.org/10.1520/D3175-20. www.astm.org. [CrossRef]

- ASTM Standard E873 (2013) Standard Test Method for Bulk Density of Densified Particulate Biomass Fuels. ASTM International, West Conshohocken, PA. https://doi. org/10.1520/E0873-82R13. www.astm.org.

- Ayuba, K. A., Manaf, L. A., Sabrina, A. H., & Azmin, S. W. N. (2013). Current status.

- of municipal solid waste management practise in FCT Abuja. Research journal of environmental and earth sciences, 5(6), 295-304.

- Bin Y, Yu Z, Li M, Huang Z, Zhan J, Liao Y, Zheng A, Ma X (2022) Ex-situ catalytic co-pyrolysis of sawdust and municipal solid waste based on multilamellar MFI nanosheets to obtain hydrocarbon-rich bio-oil, J. Anal. Appl. Pyrolysis 167:105673, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaap.2022.105673. [CrossRef]

- Bot BV, Sosso OT, Tamba JG, Lekane E, Bikai J, Ndame MK (2021) Preparation and characterization of biomass briquettes made from banana peels, sugarcane bagasse, coconut shells and rattan waste. Biomass Convers Biorefn 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1007/ s13399-021-01762-w. [CrossRef]

- Butt, T.E., Javadi, A.A., Nunns, M.A. and Beal, C.D. (2016) ‘Development of a conceptual framework of holistic risk assessment – landfill as a particular type of contaminated land’, Sci. Total Environ., pp.569–570, pp.815–829, doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2016.04.152. [CrossRef]

- Chonattu, J., Prabhakar, K. and Pillai, H.P.S. (2016) ‘Geospatial and statistical assessment of groundwater contamination due to landfill leachate – a case study’, J. Water Resour. Prot., Vol. 8, pp.121–134, doi: 10.4236/jwarp.2016.82010. [CrossRef]

- Erol M, Haykiri-Acma H, Küçükbayrak S (2010) Calorifc value estimation of biomass from their proximate analyses data. Renew Energy 35(1):170–173. https://doi.org/10.4314/njbas.v25i2.4. [CrossRef]

- Fernandez A, Ortiz L.R, Asensio D, Rodriguez R, Mazza G (2020) Kinetic analysis and thermodynamics properties of air/steam gasification of agricultural waste, J.Environ.Chem.Eng.8(4):103829,https://doi.org/10.1016/j. jece.2020.103829. [CrossRef]

- Ganesan, S., & Vedagiri, P. (2024). Production and emission characterization of.

- briquette for sustainable development: MSW transformation. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 1-15.

- Gallardo, A., Carlos, M., Peris, M. and Colomer, F.J. (2014) ‘Methodology to design a municipal solid waste generation and composition map: a case study’, Waste Manag., Vol. 34, pp.1920–1931, doi: 10.1016/j.wasman.2014.05.014. [CrossRef]

- Guo Z, Wu J, Zhang Y, Wang, F, Guo Y, Chen K, Liu H, (2020) Characteristics of.

- biomass charcoal briquettes and pollutant emission reduction for sulfur and Nitrogen during combustion. Fuel 272,11763 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fuel.2020.117632. [CrossRef]

- Hoornweg, D and Bhada-Tata, P.(2016) Solid Waste and Climate Change. Can a City Be Sustain, p.450, Worldwatch Institute, Washington, DC.

- Ifa L (2019) Production of bio-briquette from biochar derived from pyrolysis of cashew nut waste. Ecol Environ Conserv (EEC) 25:125–131.

- Ifa, L., Yani, S., Nurjannah, N., Darnengsih, D., Rusnaenah, A., Mel, M., Mahfud, M., Kusuma, H.S., (2020) Techno-economic Analysis of Bio-Briquette from Cashew Nut Shell Waste, 6. Heliyon, p. e05009. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2020.e05009. [CrossRef]

- ISO 16994 (2015) Solid biofuels—determination of total content of sulfur and chlorine. ISO, Geneva, pp 2015.

- Hasan, M.M., Rasul, M.G., Khan, M.M.K., Ashwath, N., Jahirul, M.I (2021) Energy recovery from municipal solid waste using pyrolysis technology: a review on current status and developments, Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 145, 111073, https://doi. org/10.1016/j.rser.2021.111073. [CrossRef]

- Kizito, S., Jjagwe, J., Ssewaya, B., Nekesa, L., Tumutegyereize, P., Zziwa, A., Komakech, A.J (2022) Biofuel characteristics of non-charred briquettes from dried fecal sludge blended with food market waste: suggesting a waste-to-biofuel enterprise as a win–win strategy to solve energy and sanitation problems in slums settlements. Waste Manage. (Oxford) 140, 173–182. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. wasman.2021.11.029. [CrossRef]

- Krajnc, N., (2015) Woodfuels Handbook. Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO), Pristina, Kosovo, p. 31 p.

- Kriẑan P, Matúš M, Šooš L, Kers J, Peetsalu P, Kask Ü, Menind A, (2011) Briquetting of municipal solid waste by different technologies in order to evaluate its quality and properties. Agron. Res. 9, 115–123.

- Li G, Hu R, Hao Y, Yang T, Li L, Luo Z, Shen G (2023) CO2 and air pollutant emissions from bio-coal briquettes. Environ Tech nol Innov 29:102975. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eti.2022.102975. [CrossRef]

- Maninder, Kathuria RS, Grover S (2012) Using agricultural residues as a biomass briquetting: an alternative source of energy. J Electrical Electron Eng 1:11–15. https://doi.org/10.9790/1676-0151115. [CrossRef]

- Matli, C., Challa, B., & Kadaverugu, R. (2019). Co-firing municipal solid waste with coal-A case study of Warangal City, India. Nature Environment and Pollution Technology, 18(1), 237-245.

- Mfomo JZ, Biwolé AB, Fongzossie EF, Ekassi GT, Hubert D, Ducenne H, Mouangue R (2020) Carbonization techniques and wood species infuence quality attributes of charcoals produced from industrial sawmill residues in Eastern Cameroon. Bois For Trop 345:65–74.

- Nascimento, V.F., Silva, A.M. and Sobral, A.C. (2015a) Indicação de áreas para aterro sanitário, utilizando geoprocessamento, Novas Edições Acadêmicas, Saarbrücken.

- Nikiema, J., Asamoah, B., Egblewogbe, M. N., Akomea-Agyin, J., Cofie, O. O.,.

- Hughes, A. F., ... & Njenga, M. (2022). Impact of material composition and food waste decomposition on characteristics of fuel briquettes. Resources, Conservation & Recycling Advances, 15, 200095.

- Ngwabie NM, Wirlen YL, Yinda GS, VanderZaag AC (2019) Quantifying greenhouse gas emissions from municipal solid waste dumpsites in Cameroon. Waste Managn 87:947–953. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wasman.2018.02.048. [CrossRef]

- Ofori P (2020) Production and characterisation of briquettes from carbonised cocoa pod husk and sawdust. Open Access Library J 7(02):1.

- Onyanta, A. (2016). Cities, municipal solid waste management, and climate change:.

- Perspectives from the South. Geography Compass, 10(12), 499-513.

- Otieno AO, Home PG, Raude JM, Murunga SI, Gachanja A (2022) Heating and emission characteristics from combustion of charcoal and co-combustion of charcoal with faecal char-sawdust char briquettes in a ceramic cook stove. Heliyon 8(8). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2022.e10272. [CrossRef]

- Poespowati, T., Mustiadi, L., 2012. Municipal solid waste densification as an alternative energy. J. Energ. Tech. Pol. 2 (4), 20–25.

- Sarigiannis, D. A., Handakas, E. J., Karakitsios, S. P., & Gotti, A. (2021). Life cycle.

- assessment of municipal waste management options. Environmental Research, 193, 110307.

- Sarquah K, Narra S, Beck G, Awafo EA, Antwi E (2022) Bibliometric analysis; characteristics and trends of refuse derived fuel research. Sustainability 14(4):1994. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14041994. [CrossRef]

- Setter C, Ataíde CH, Mendes RF, De Oliveira TJP (2021) Infuence of particle size on the physico-mechanical and energy properties of briquettes produced with cofee husks. Environ Sci Pollut Res 28:8215–8223. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-020-11124-0. [CrossRef]

- Song Q, Zhao H.J, Jia, L. Yang W. Lv, Bao J, Shu X, Gu Q, Zhang P, (2020) Pyrolysis of municipal solid waste with iron-based additives: a study on the kinetic, product distribution and catalytic mechanisms, J. Clean. Prod. 258, 120682, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.120682. [CrossRef]

- Suksankraisorn, K., Patumsawad, S., & Fungtammasan, B. (2010). Co-firing of Thai.

- lignite and municipal solid waste (MSW) in a fluidised bed: Effect of MSW moisture content. Applied Thermal Engineering, 30(17-18), 2693-2697.

- Trombley JB, Wang C, Thennadil SN (2023) Model-free measurements of calorifc content and ash content of mixed garden wastes using a bomb calorimeter. Fuel 352:129105. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. fuel.2023.129105. [CrossRef]

- Tumuluru, J.S., Yancey, N.A., Kane, J.J., 2021. Pilot-scale grinding and briquetting studies on variable moisture content municipal solid waste bales – Impact on physical properties, chemical composition, and calorific value. Waste Manage. (Oxford) 125, 316–327. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wasman.2021.02.013. [CrossRef]

- Trombley JB, Wang C, Thennadil SN (2023) Model-free measurements of calorifc content and ash content of mixed garden wastes using a bomb calorimeter. Fuel 352:129105. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. fuel.2023.129105. [CrossRef]

- Tumuluru, J.S., Yancey, N.A., Kane, J.J., 2021. Pilot-scale grinding and briquetting studies on variable moisture content municipal solid waste bales – Impact on physical properties, chemical composition, and calorific value. Waste Manage. (Oxford) 125, 316–327. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wasman.2021.02.013. [CrossRef]

- Vamvuka, D., Sfakiotakis, S., & Saxioni, S. (2015). Evaluation of urban wastes as.

- promising co-fuels for energy production–A TG/MS study. Fuel, 147, 170-183.

- van Loo, T. L. S., & Koppejan, J. (2008). Biomass ash characteristics and behaviour.

- in combustion systems. UPDATE, 4(4).

- Vasileiadou, A., Zoras, S., & Iordanidis, A. (2021). Fuel Quality Index and Fuel.

- Quality Label: Two versatile tools for the objective evaluation of biomass/wastes with application in sustainable energy practices. Environmental Technology & Innovation, 23, 101739.

- Vasileiadou, A., Papadopoulou, L., Zoras, S., & Iordanidis, A. (2022). Development.

- of a total Ash Quality Index and an Ash Quality Label: Comparative analysis of slagging/fouling potential of solid biofuels. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 29(28), 42647-42663.

- WorldBank (2020) Solid Waste Management.

- Worldometers (2023) World population. http://countrymeters.info/ en/World.

- Zinla D, Gbaha P, Kof PME, Koua BK (2021) Characterization of rice, cofee and.

- cocoa crops residues as fuel of thermal power plant in Côte d’Ivoire. Fuel 283:119250. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. fuel.2020.119250. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J., Guo, Y., 2014. Physical properties of solid fuel briquettes made from Caragana korshinskii Kom. Powder Technol. 256, 293–299.

- Zhou C, Zhang Q, Arnold L, Yang W, Blasiak W (2013) A study of the pyrolysis behaviors of pelletized recovered municipal solid waste fuels, Appl. Energy 107: 173–182, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apenergy.2013.02.029. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, C., Jiang, D. and Zhao, Z. (2016) ‘Quantification of the greenhouse gas emissions from the pre-disposal stage of municipal solid waste management’, Environ. Sci. Technol., doi: 10.1021/acs.est.6b05180. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y., Zhang, Y., Luo, D., Chong, Z., Li, E., & Kong, X. (2021). A review of.

- municipal solid waste in China: characteristics, compositions, influential factors and treatment technologies. Environment, Development and Sustainability, 23, 6603-6622.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).