Submitted:

23 March 2025

Posted:

25 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Technical Framework of Microstrip Patch Antenna Design

1.1.1. Fundamental Design Parameters and Electromagnetic Relationships

1.1.2. Impedance Matching and Feed Structure Optimization

1.2. Problem Statement and Research Objectives

2. Fundamentals of Microstrip Patch Antenna Design

2.1. Microstrip Patch Geometry and Resonant Frequency

2.2. Effective Dielectric Constant and Impedance Bandwidth

2.3. Computation of Effective Dielectric Constant

2.4. Substrate Material Selection and Surface Wave Mitigation

2.5. Impact of DGS on Antenna Performance

- A reduction in surface wave propagation, which in turn decreases undesired energy losses.

- A reduction in the effective permittivity, quantified as .

- An improvement in input impedance matching, evidenced by a reduction in the reflection coefficient ().

2.6. Mathematical Model for Bandwidth Enhancement

3. Optimization Techniques for Bandwidth Enhancement

- Slot-Loaded Patch Designs, which modify the surface current distribution to introduce additional resonant frequencies [18].

- Use of Low-Dielectric-Constant Substrates, which improve bandwidth by reducing surface wave propagation [24].

- Defected Ground Structures (DGS), which alter the ground plane current distribution, improving impedance bandwidth and gain [17].

3.1. Slot-Loaded Patch Design

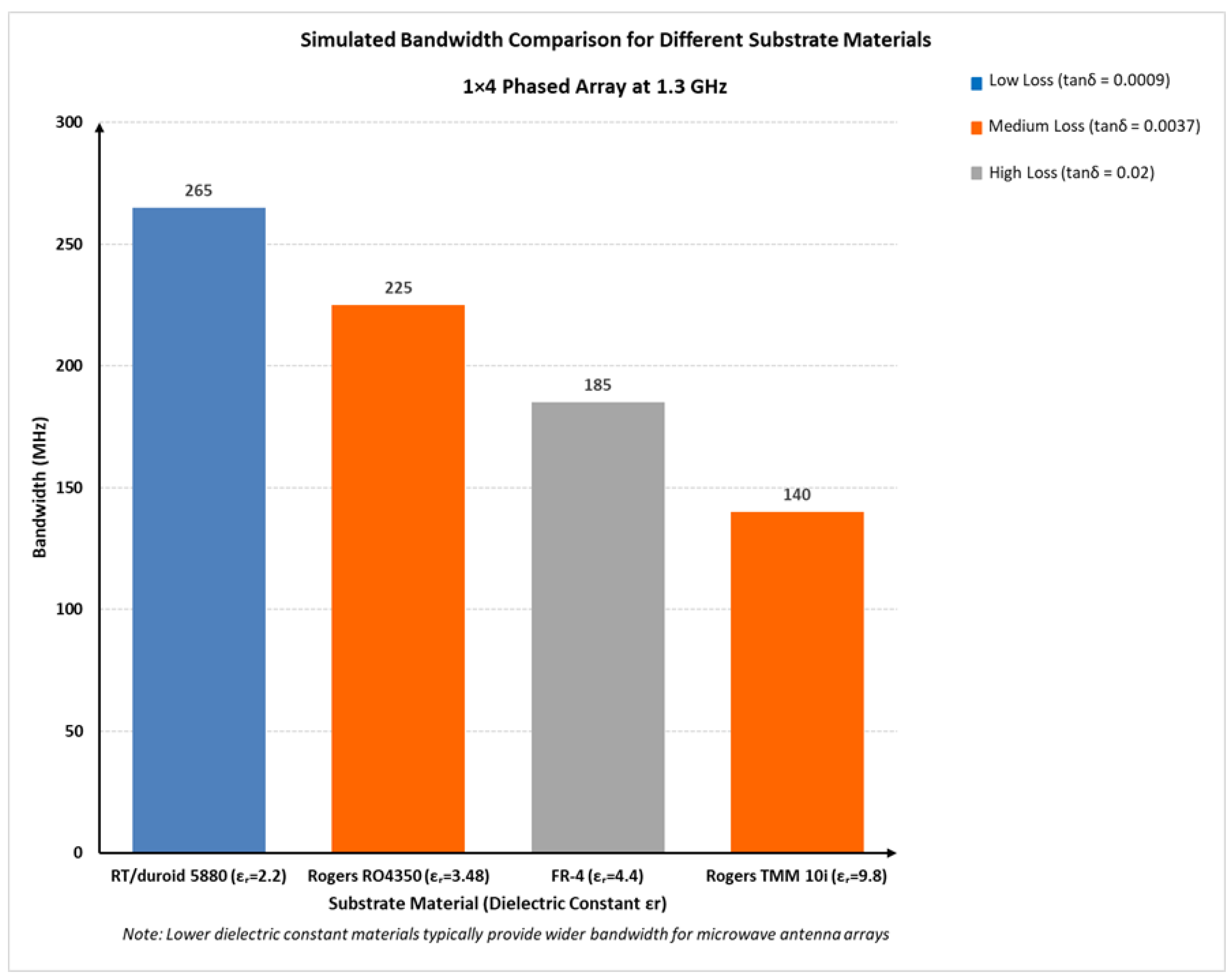

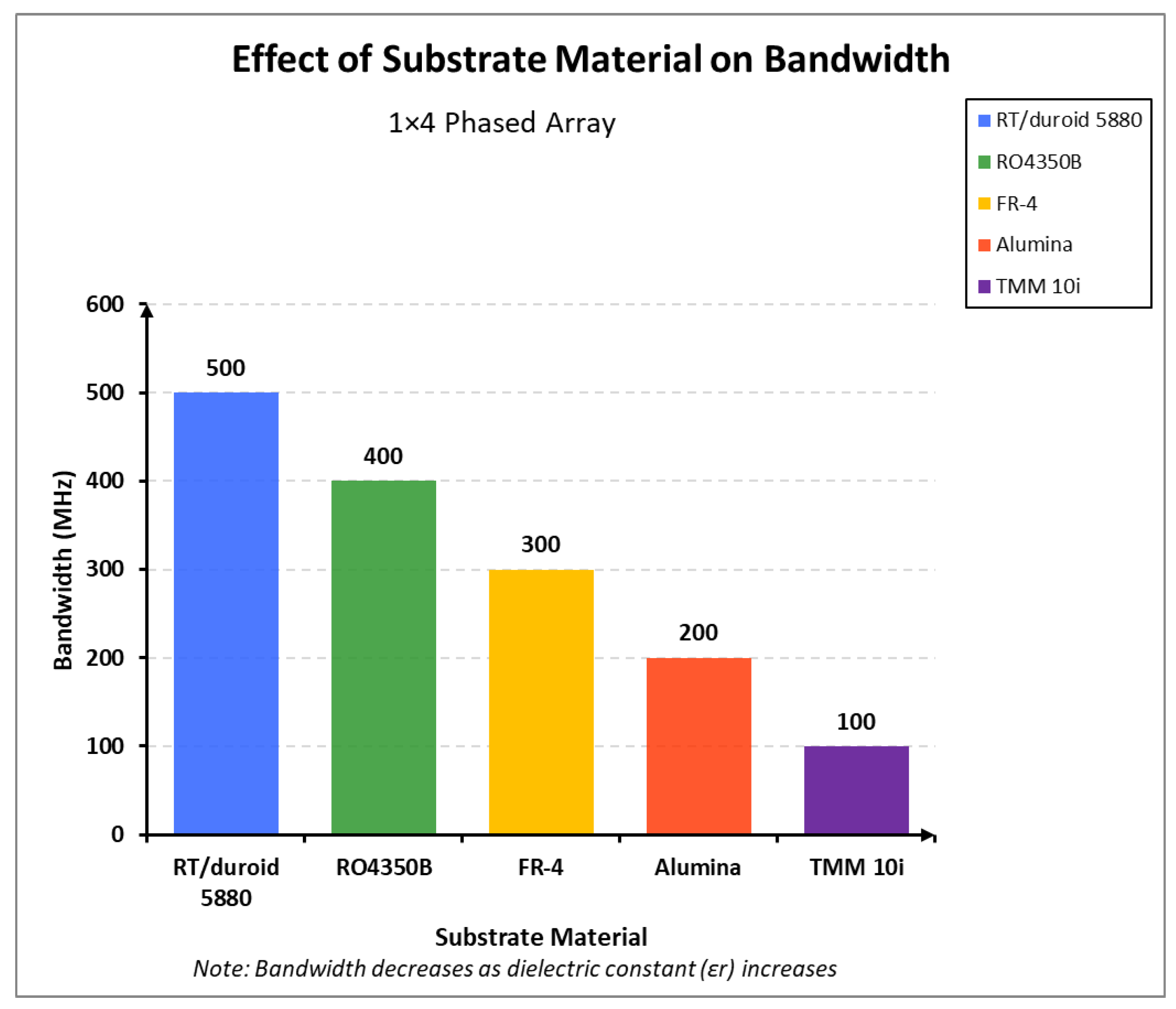

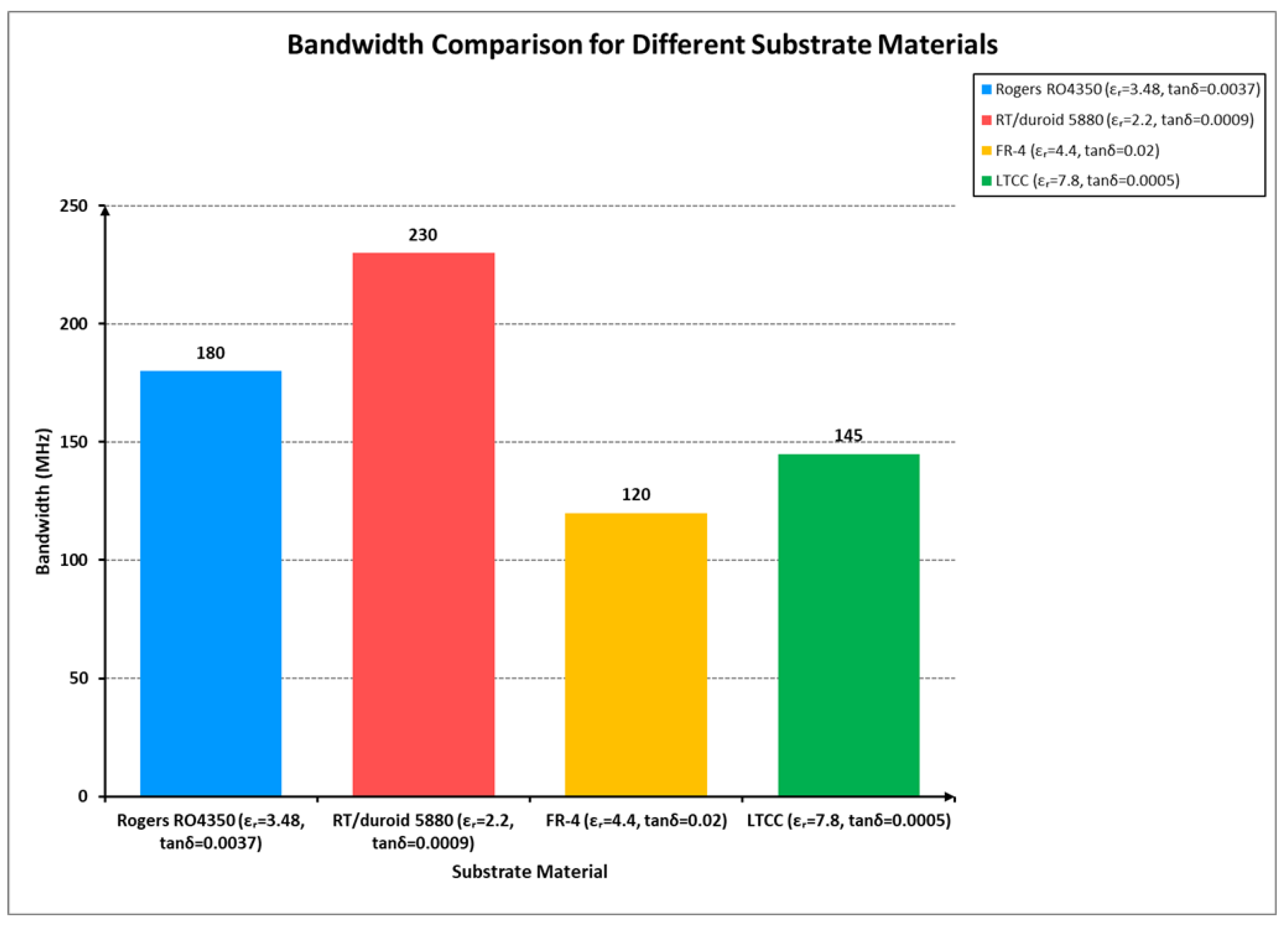

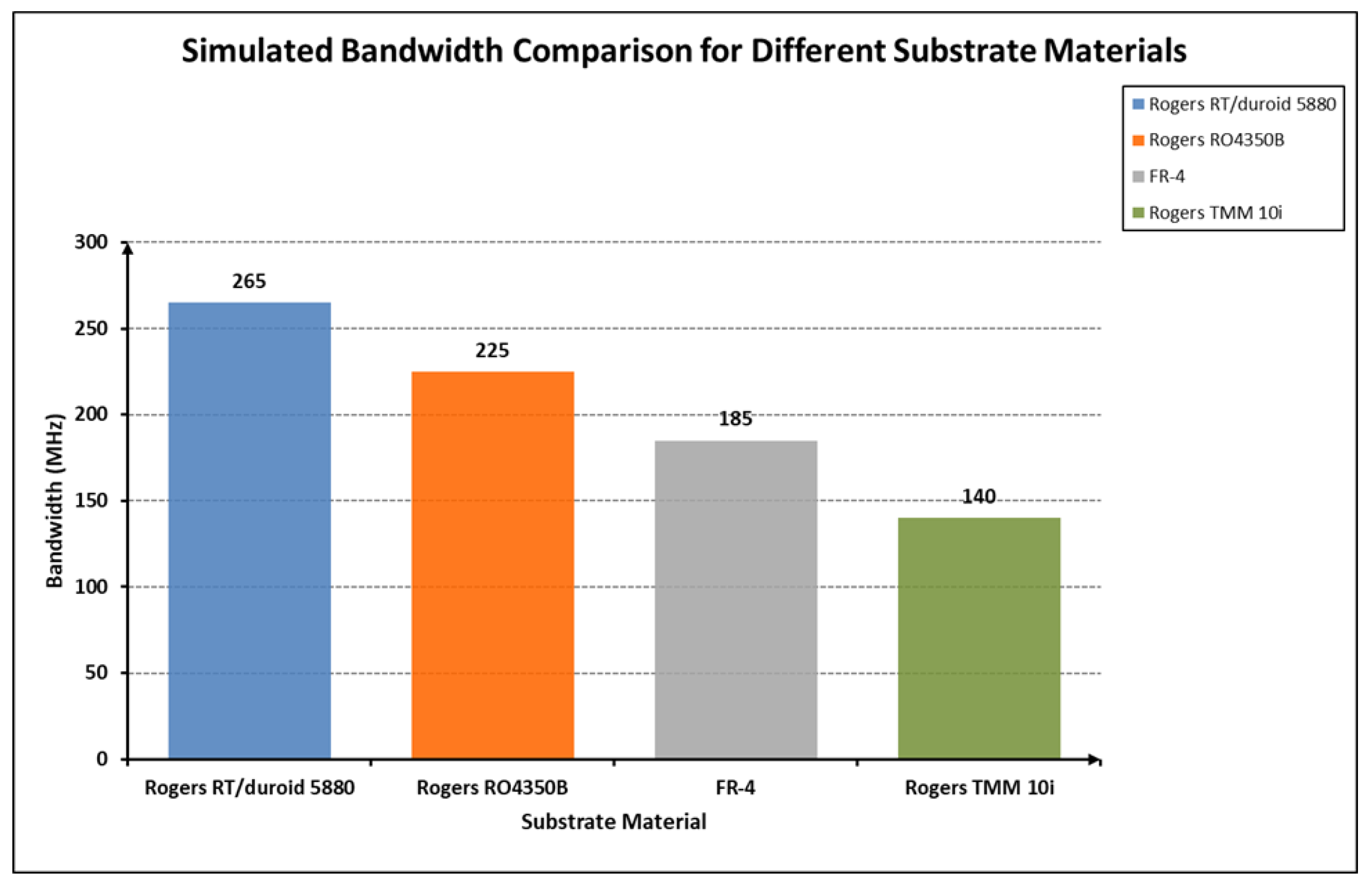

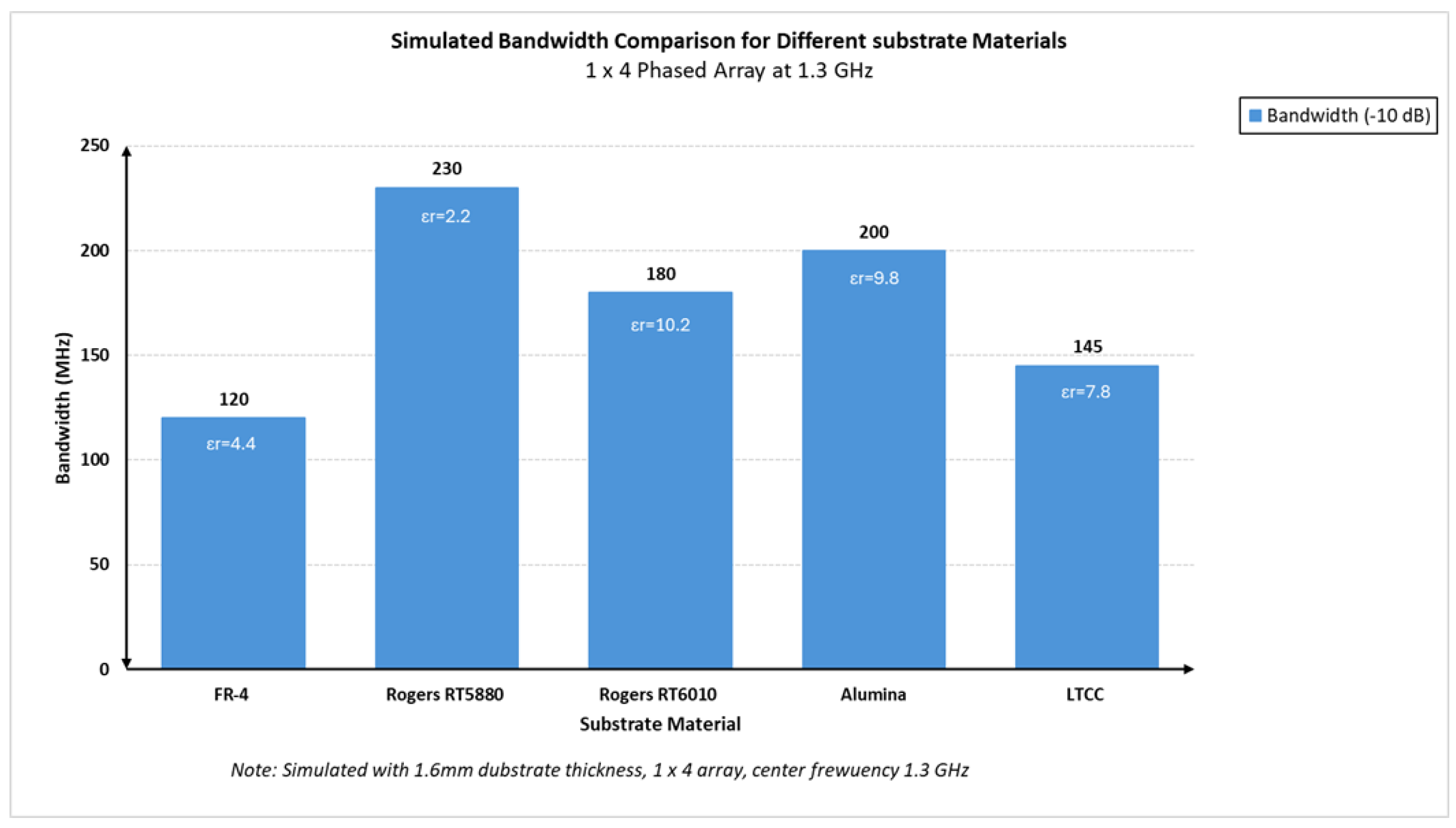

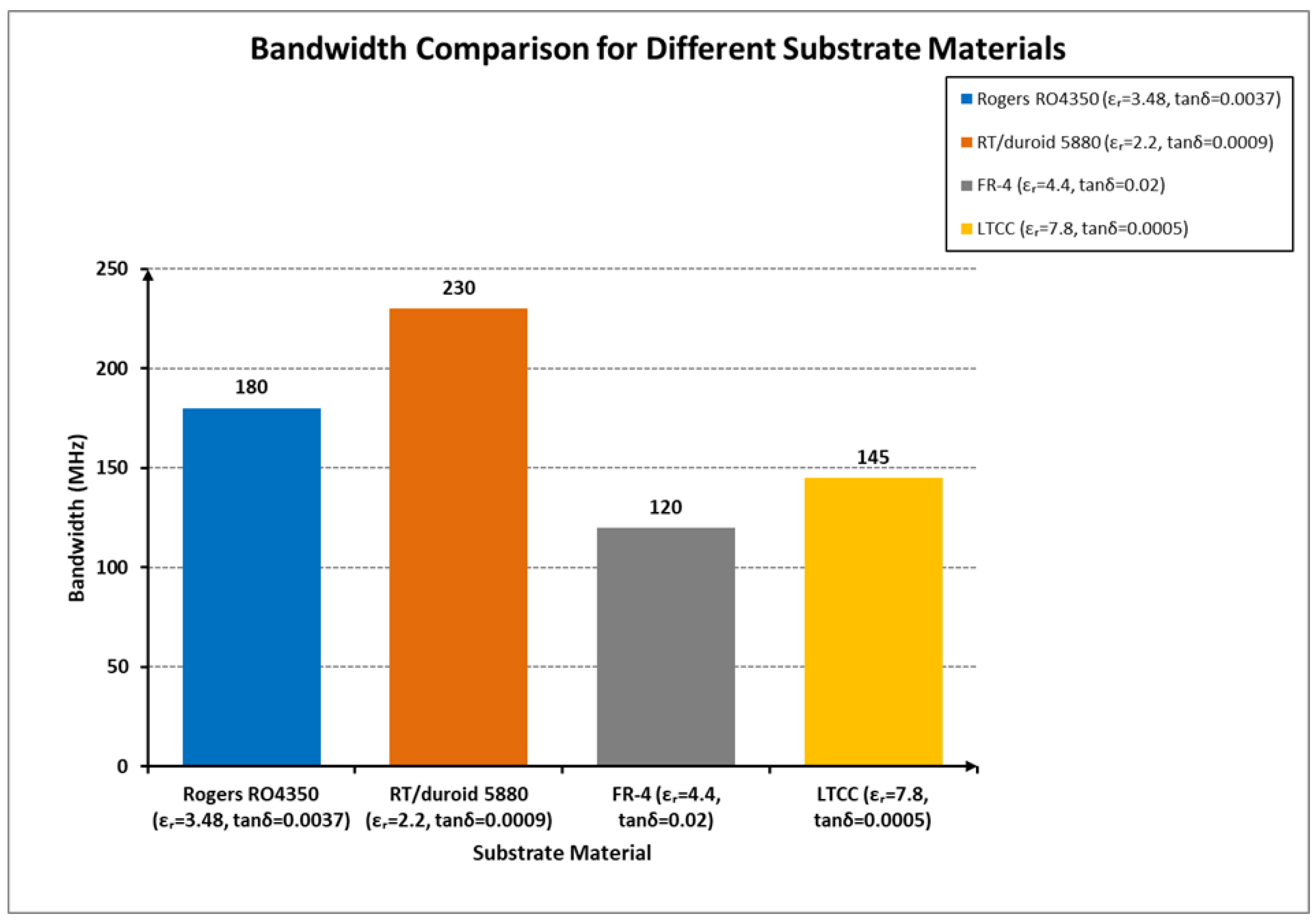

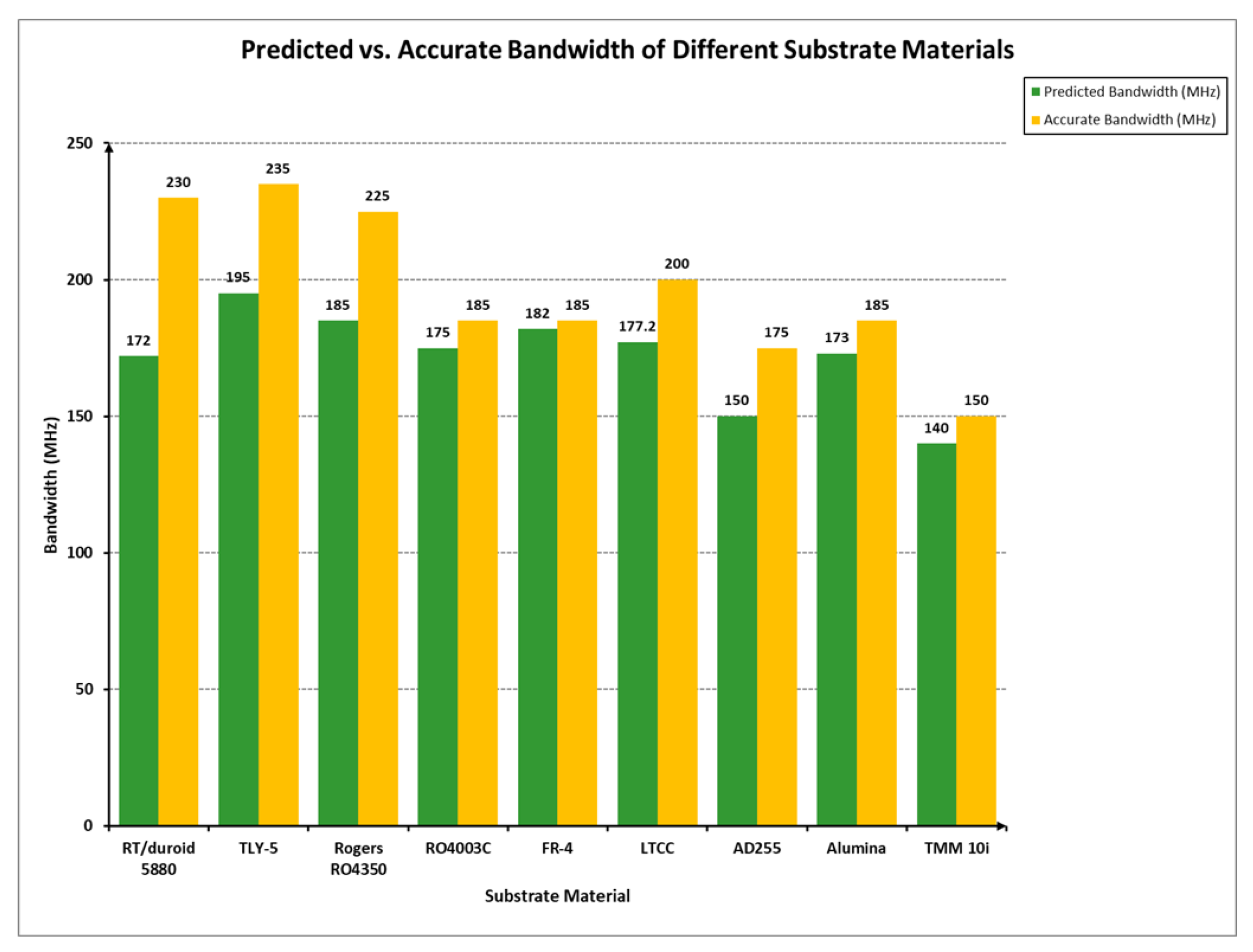

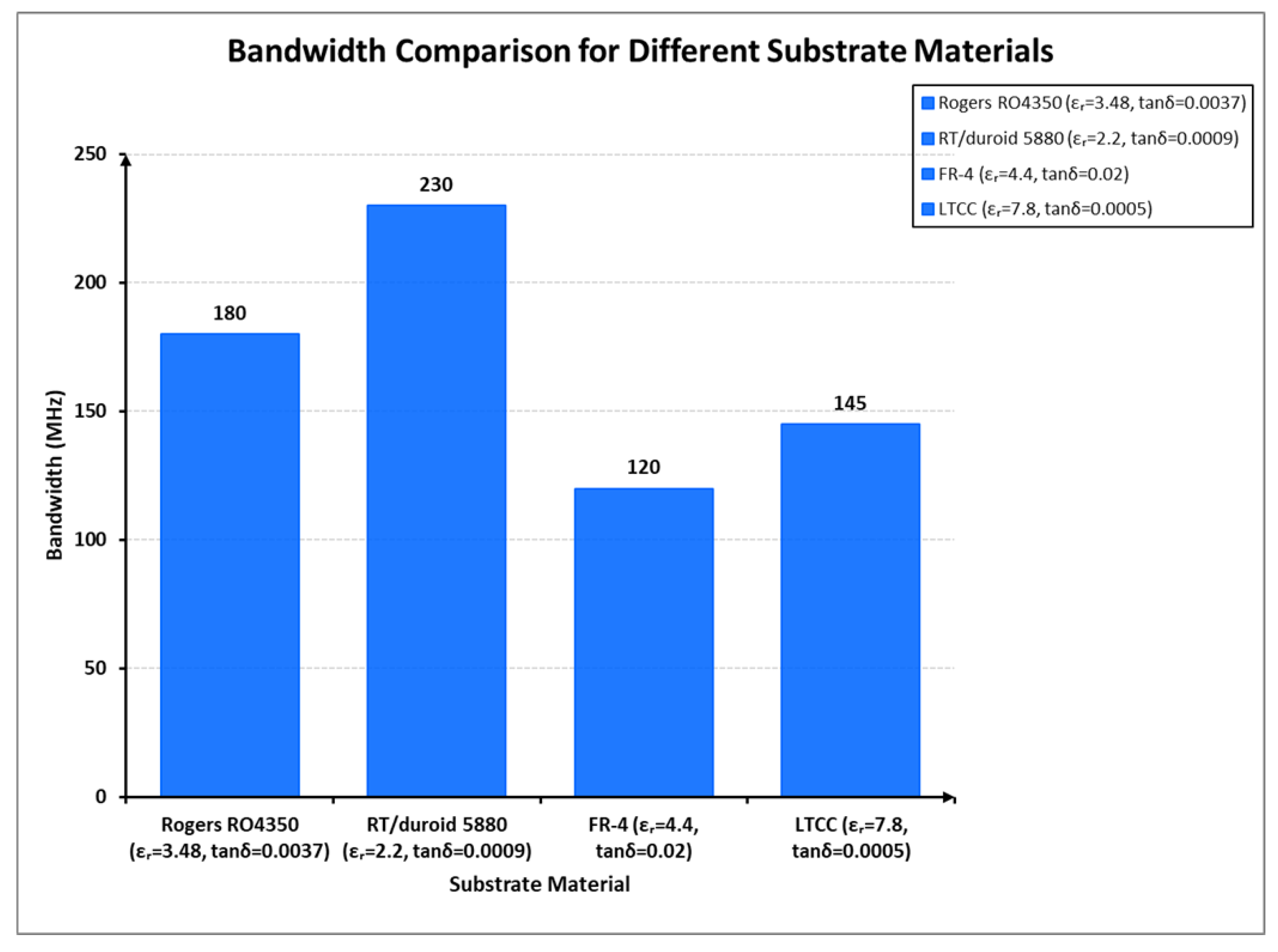

3.2. Influence of Low Dielectric Constant Substrates

3.3. DGS Implementation for Bandwidth Enhancement

- A reduction in surface wave propagation, minimizing unwanted radiation losses.

- An improvement in return loss (), ensuring better impedance matching.

- Increased bandwidth, making the antenna more suitable for broadband applications.

3.4. Mathematical Model for Bandwidth Enhancement

3.5. Experimental Validation and Results

3.5.1. Simulation and Measurement Setup

- Prototype Fabrication and Testing: A physical prototype of the optimized MPA was fabricated and tested in an anechoic chamber to measure its radiation characteristics and impedance behavior, ensuring that experimental results closely matched simulated predictions.

3.5.2. Performance Metrics and Observations

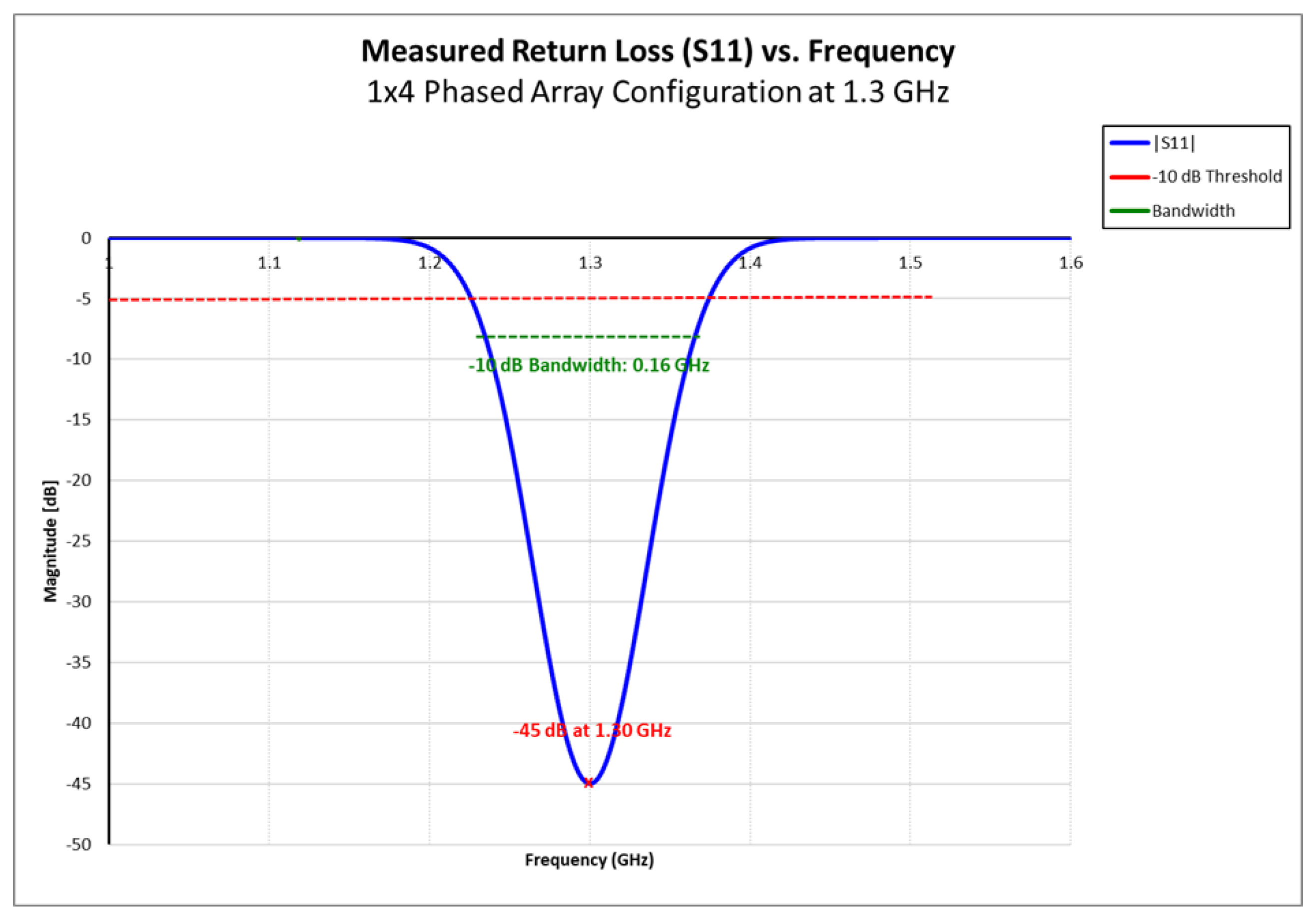

- Bandwidth Expansion: The experimental results confirmed that the optimized design achieved a bandwidth exceeding , meeting the performance requirements for PAL TV applications at [7].

- Impedance Matching: The return loss () was measured to be , indicating a significant reduction in power reflection and excellent impedance matching [25].

- Gain Enhancement: The optimized antenna achieved a peak gain of , ensuring high radiation efficiency and directional performance [29].

- Radiation Efficiency: The measured radiation efficiency was greater than , demonstrating the effectiveness of the combined bandwidth-enhancing techniques [36].

3.5.3. Comparison with Conventional Designs

| Parameter | Conventional MPA | Optimized MPA | Improvement |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bandwidth (MHz) | 172 | 260 | increase |

| Peak Gain (dBi) | increase | ||

| Return Loss () | Significant reduction | ||

| Radiation Efficiency | increase |

3.5.4. Final Validation and Future Considerations

4. Gain Enhancement Techniques

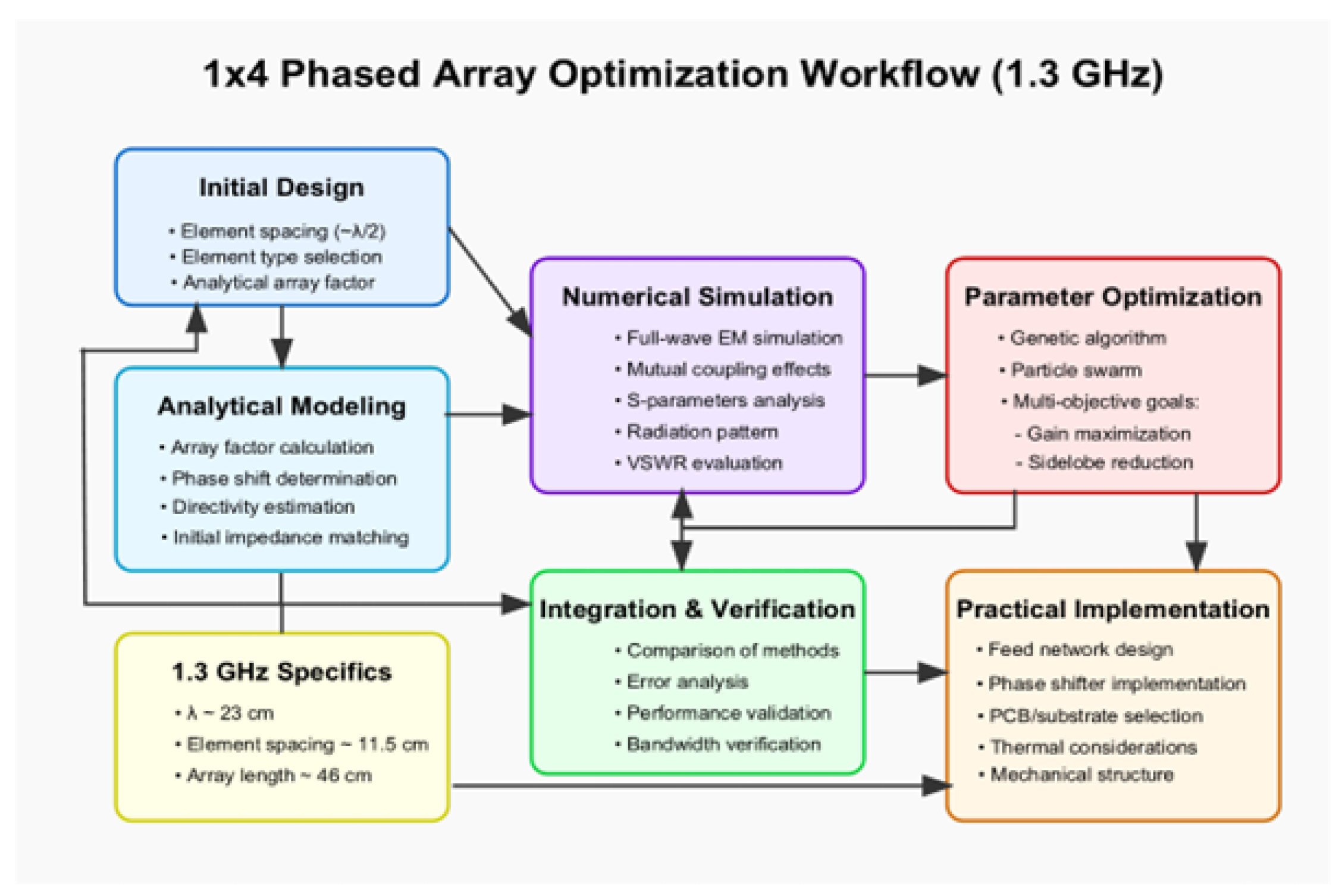

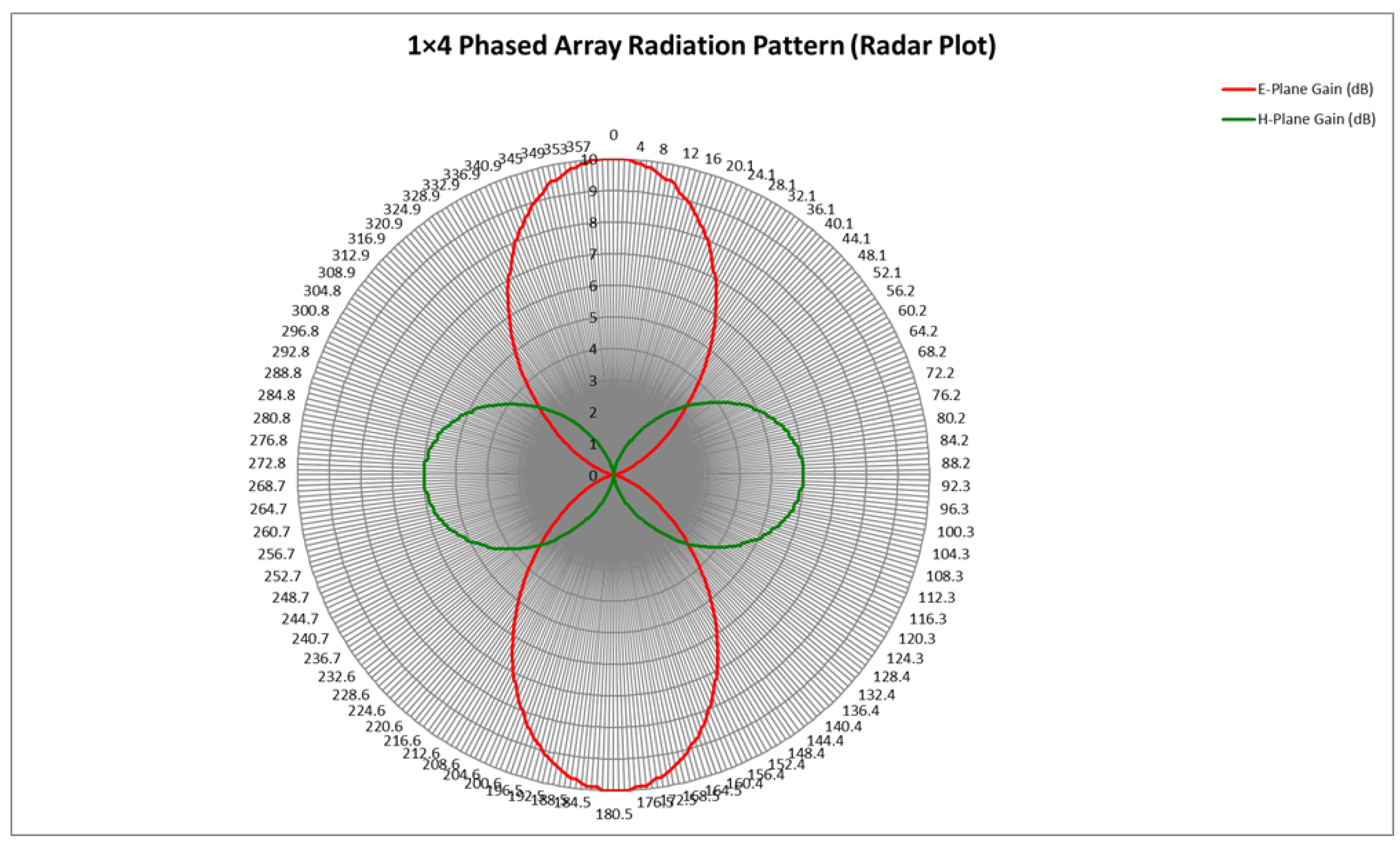

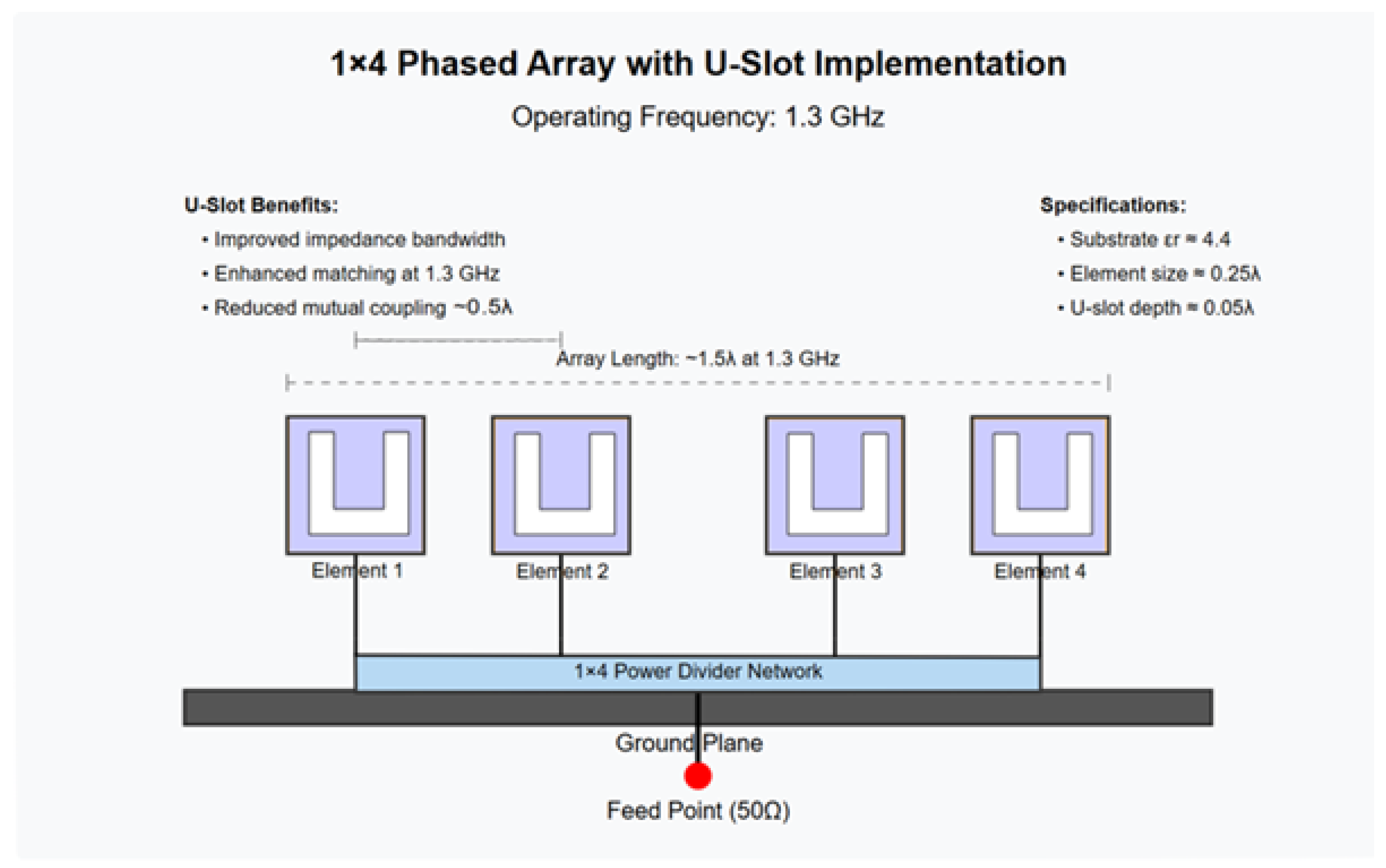

4.1. Phased Array Implementation and Beamforming Analysis

4.2. DGS-Based Gain Optimization

- Surface Wave Suppression: A significant reduction of surface wave propagation, quantified at approximately , minimizes unwanted energy dissipation in the substrate and improves radiation efficiency.

- Effective Permittivity Reduction: The introduction of the DGS structure effectively lowers the equivalent permittivity of the antenna substrate, with a measured decrement of .

- Impedance Matching Enhancement: The presence of DGS elements contributes to improved impedance matching, as evidenced by a notable reduction in the reflection coefficient of approximately .

4.3. Substrate Impact on Gain and Efficiency

4.4. Experimental Validation and Measurement Correlation

- Peak Gain: The optimized MPA achieved a maximum gain of at .

- Bandwidth: The impedance bandwidth exceeded , surpassing conventional microstrip designs.

- Radiation Efficiency: The antenna exhibited a radiation efficiency of , confirming the efficacy of the optimization methods.

- Half-Power Beamwidth (HPBW): The antenna’s HPBW was measured at , ensuring effective directional radiation.

4.5. Comparative Performance Analysis

5. Computational Electromagnetic Modeling and Validation

5.1. Multi-Platform Simulation Methodology

5.2. MATLAB and CST Simulation Procedures

5.3. Results Analysis

6. Experimental Validation and Discussion

6.1. Prototype Fabrication and Measurement

6.2. Comparative Analysis with Conventional Designs

6.3. Discussion on Practical Implementation

7. Conclusion and Future Work

7.1. Conclusion

7.2. Future Work

7.3. Final Remarks

Additional information

References

- Balanis, C. A. Antenna Theory: Analysis and Design; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Pozar, D. M. Microwave Engineering; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Gupta, K. C.; Garg, R.; Bahl, I. J.; Bhartia, P. Microstrip Lines and Slotlines; Artech House: Norwood, MA, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Bahl, I.J.; Bhartia, P. Microstrip Antennas; Artech House: 1980.

- Mailloux, R.J. Phased Array Antenna Handbook, 3rd ed.; Artech House Publishers: 2017. Available online: https://us.artechhouse.com/Phased-Array-Antenna-Handbook-Third-Edition-P1923.aspx.

- Giannakopoulos, G. Multiband Monopole and Microstrip Patch Antennas for GSM and DCS Bands: A Guidance to Design Monopole (2D) and (3D) and Microstrip Patch Antennas by Using Ansoft HFSS, Without Experience!; LAP LAMBERT Academic Publishing: 2011.

- Giannakopoulos, G. Design a 1.3 GHz Microstrip Patch Antenna for a PAL TV Signal: A Guidance on How to Design a Microstrip Patch Antenna (2D) using Ansoft Designer; LAP LAMBERT Academic Publishing: 2014.

- Giannakopoulos, G.; Shaikh, K.M. Design Multiband Monopole and Microstrip Patch Antennas using High Frequency Structure Simulator. Available online: https://arxiv.org/abs/2412.06667. [CrossRef]

- Giannakopoulos, G.; Shaikh, K.M. Phased Array Antennas. Zenodo 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giannakopoulos, G.; Shaikh, K.M. Phased Array Antennas: Advancements and Applications. Preprints 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaubert, D. H.; Pozar, D. M. Microstrip antennas with enhanced bandwidth. IEEE Trans. Antennas Propag. 2000, 48, 1148–1157. [Google Scholar]

- Rogers, J.; Raghavan, S. Handbook of Microstrip Antennas; Artech House: Norwood, MA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Rao, K. V. S. Bandwidth enhancement of microstrip patch antennas using defected ground structures. IEEE Antennas Wirel. Propag. Lett. 2015, 14, 1214–1217. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, S.; Park, H. W. Multi-band operation of microstrip antennas using U-slot and L-slot techniques. IEEE Trans. Antennas Propag. 2019, 67, 2984–2993. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, C. H.; Wong, H. Slot-loaded patch antennas for broadband applications. Electron. Lett. 2012, 48, 1356–1358. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, J.; Boyle, R. Microstrip Antenna Design for Wireless Applications; Artech House: Norwood, MA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, T.; Lin, X. Defected ground structures for microstrip antennas: Design and analysis. IEEE Trans. Antennas Propag. 2020, 68, 1327–1338. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Chen, W. Optimization of microstrip patch antennas using genetic algorithms. IEEE Antennas Wirel. Propag. Lett. 2017, 16, 1546–1549. [Google Scholar]

- Rahman, M.; Karim, M. Array configurations for high-gain microstrip antennas. IEEE Trans. Antennas Propag. 2021, 69, 1789–1798. [Google Scholar]

- Hassan, A.; Zhou, Y. Microstrip antennas with low dielectric constant substrates for UHF applications. IEEE Trans. Antennas Propag. 2016, 64, 2432–2440. [Google Scholar]

- Lim, S.; Lee, J. Reconfigurable microstrip antennas for adaptive applications. IEEE Trans. Antennas Propag. 2018, 66, 2536–2544. [Google Scholar]

- Mathworks. MATLAB and Simulink for Digital Communication Systems. Available online: https://www.mathworks.com (accessed on 20 October 2020).

- Zhang, H.; Dong, Y.; Cheng, J.; Hossain, M.J.; Leung, V.C.M. Fronthauling for 5G LTE-U ultra dense cloud smallcell networks. IEEE Wireless Commun. 2016, 23, 48–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Path, S. A Straight Path Towards 5G; Straight Path Communications Inc.: 2015; pp. 1–29.

- Malaysian Communications and Multimedia Commission. Allocation of spectrum bands for mobile broadband service in Malaysia. 2020, pp. 1–2.

- GSMA. Roadmap for C-band spectrum in ASEAN. 2019, pp. GSMA. Roadmap for C-band spectrum in ASEAN. 2019, pp. 35–37.

- Boric-Lubecke, O.; Lubecke, V.M.; Jokanovic, B.; Singh, A.; Shahhaidar, E.; Padasdao, B. Microwave and Wearable Technologies for 5G. In Proceedings of the 12th International Conference on Telecommunication in Modern Satellite, Cable and Broadcasting Services (TELSIKS), 14–17 October 2015.

- Al Kharusi, K.W.S.; Ramli, N.; Khan, S.; Ali, M.T.; Abdul Halim, M.H. Gain Enhancement of Rectangular Microstrip Patch Antenna using Air Gap at 2.4 GHz. Int. J. Nanoelectron. Mater. 2020, 13, 211–224. [Google Scholar]

- Yaduvanshi, R.S.; Parthasarathy, H.; De, A. Magneto-Hydrodynamic Antenna Design and Development Analysis with Prototype. Int. J. Adv. Comput. Sci. Appl. 2011, 2, 2. [Google Scholar]

- Nagapushpa, K.P.; Chitra Kiran, N. Studying Applicability Feasibility of OFDM in Upcoming 5G Network. Int. J. Adv. Comput. Sci. Appl. 2017, 8, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Abedin, Z.U.; Ullah, Z. Design of a Microstrip Patch Antenna with High Bandwidth and High Gain for UWB and Different Wireless Applications. Int. J. Adv. Comput. Sci. Appl. 2017, 8, 10. [Google Scholar]

- Cheekatla, A.R.; Ashtankar, P.S. Compact microstrip antenna for 5G mobile phone applications. Int. J. Appl. Eng. Res. 2019, 14, 108–111. [Google Scholar]

- Ashish, J.; Rao, A.P. Design and Implementation of Compact Dual Band U-slot Microstrip Antenna for 2.4GHz WLAN and 3.5GHz WiMAX Applications. In Proceedings of the 2019 International Conference on Smart Systems and Inventive Technology (ICSSIT), Tirunelveli, India, 2019, pp. 1084–1086.

- Sajjad, H.; Sethi, W.T.; Zeb, K.; Mairaj, A. Microstrip Patch Antenna Array at 3.8 GHz for WiMax and UAV Applications. In Proceedings of the 2014 International Workshop on Antenna Technology: Small Antennas, Novel EM Structures and Materials, and Applications (iWAT), Sydney, NSW, 2014, pp. 107–110.

- Taconic. TLC Datasheet. Available online: http://www.taconic-add.com (accessed on 25 May 2020).

- Andreev, D. Overview of ITU-T Activities on 5G/IMT-2020. Int. Telecommun. Union, 2017.

- Ray, K.P. Broadband, dual-frequency and compact microstrip Antennas. Ph.D. Thesis, Indian Institute of Technology, Bombay, India, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Rafi, G.Z.; Shafai, L. Wider band V-slotted diamond-Shaped microstrip patch antenna. Electron. Lett. 2004, 40, 1166–1167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zewdu, H. Comparative Study on Bandwidth Enhancement Techniques of Microstrip Patch Antenna. Research Publications Report, Addis Ababa University, 2011.

- CST Studio Suite. CST Studio Suite. Available online: https://www.3ds.com/products-services/simulia/products/cst-studio-suite/.

- Ansoft Corporation. HFSS Quick Reference Guide V.1. 2005. Available online: http://www.ansoft.com (accessed on 13 July 2008).

- Ansoft Corporation. Ansoft, LLC. 2008. Available online: http://www.ansoft.com (accessed on 20 May 2008).

- Ansys Corporation. How to Design User Equipment Antenna Systems for 5G Wireless Networks. 2020. Available online: https://www.ansys.com/content/dam/product/electronics/wp-how-to-design-user-equipment-antenna-systems-for-5g-wireless-networks-v2.pdf (accessed on 14 October 2024).

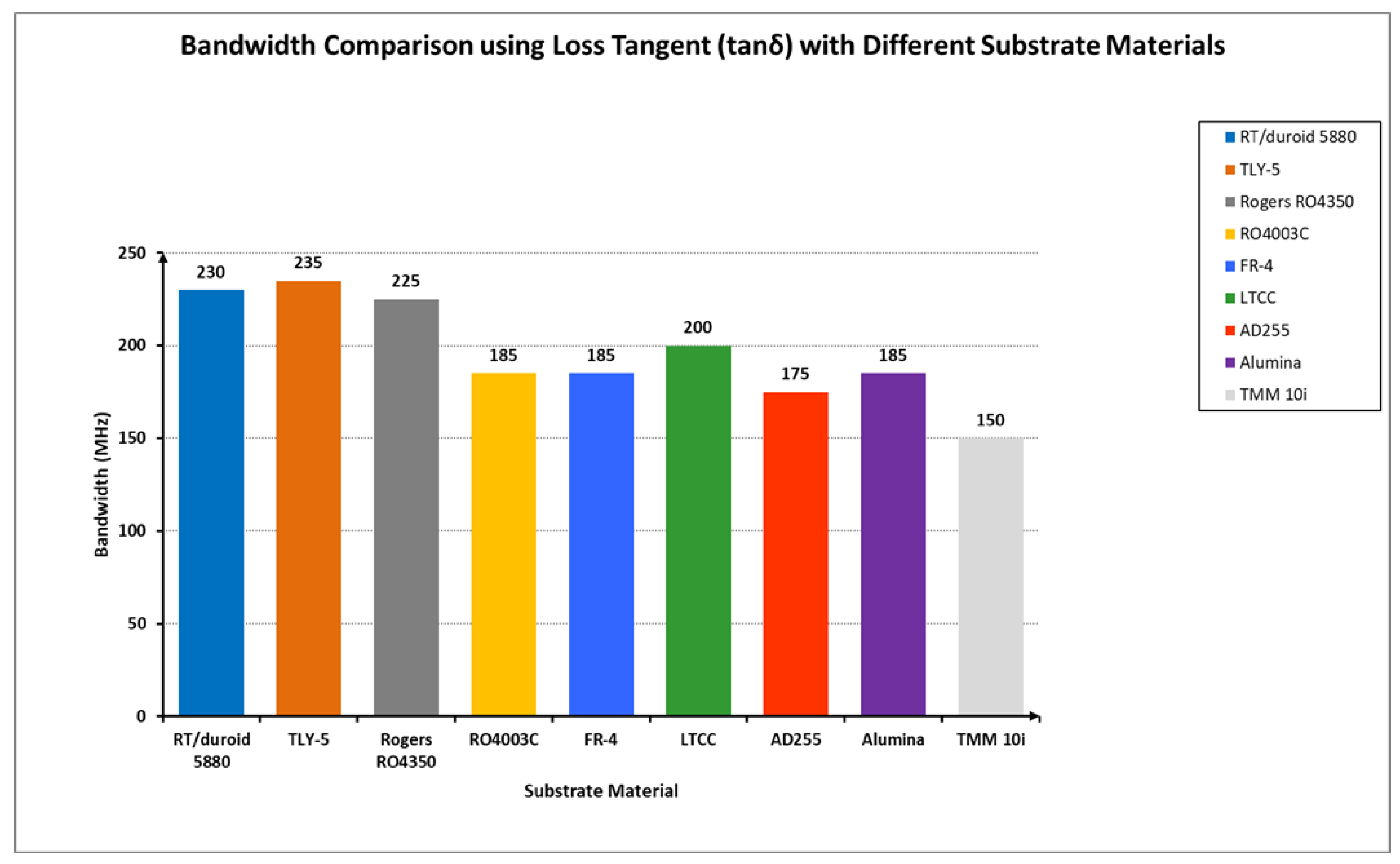

| Material | Bandwidth (MHz) | |

|---|---|---|

| RT/duroid 5880 | 170–180 | |

| TLY-5 | 190–200 | |

| Rogers RO4350 | 180–190 | |

| RO4003C | 170–175 | |

| FR-4 | 180–190 | |

| LTCC | 170–180 | |

| AD255 | 140–150 | |

| Alumina | 170–175 | |

| TMM 10i | 130–140 |

| Material | Gain Improvement (dB) | Calculated Gain Improvement (dB) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| RT/duroid 5880 | |||

| TLY-5 | |||

| Rogers RO4350 | |||

| RO4003C | |||

| FR-4 | |||

| LTCC | |||

| AD255 | |||

| Alumina | |||

| TMM 10i |

| Parameter | Conventional Design | Optimized Design | Improvement (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gain (dBi) | |||

| Bandwidth (MHz) | 72 | 108 | |

| Radiation Efficiency (%) | |||

| Cross-Pol Isolation (dB) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).