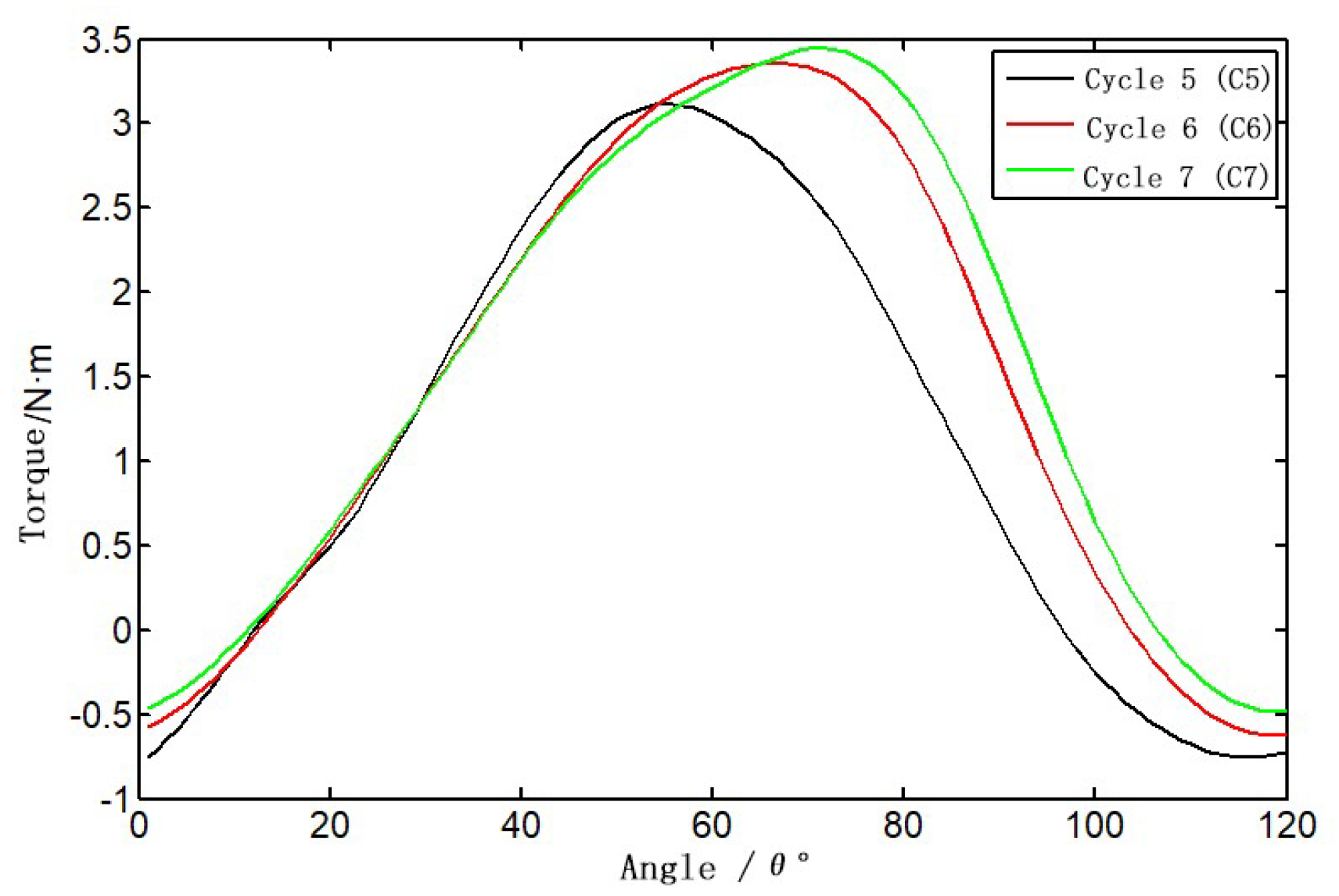

4.1. Model Validation

During numerical calculations, the wind turbine blades undergo a start-up transient phase within the first 3–5 rotational cycles, where the flow field has not yet developed stable periodic characteristics. This study employs a dynamic convergence criterion to evaluate transient results: the root-mean-square error (RMSE) of the average moment coefficient of the three blades over a single cycle is used as the convergence indicator. It is generally accepted in engineering practice that steady state is achieved when the RMSE between two consecutive cycles is less than 5%.

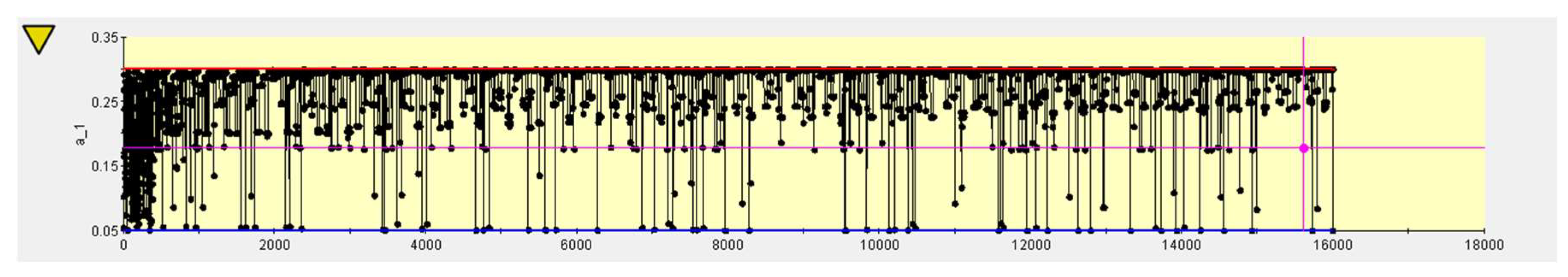

Figure 11 presents the moment coefficient curves for the fifth to seventh cycles, with average values of 1.3932, 1.3596, and 1.3266, respectively. A relative error analysis reveals a 2.4% reduction from the sixth to seventh cycle, satisfying the engineering convergence standard. Consequently, the aerodynamic data from the seventh cycle are selected as the steady-state calculation results to ensure the accuracy of subsequent optimization analyses.

Figure 11.

Fifth, sixth and seventh cycle result curves.

Figure 11.

Fifth, sixth and seventh cycle result curves.

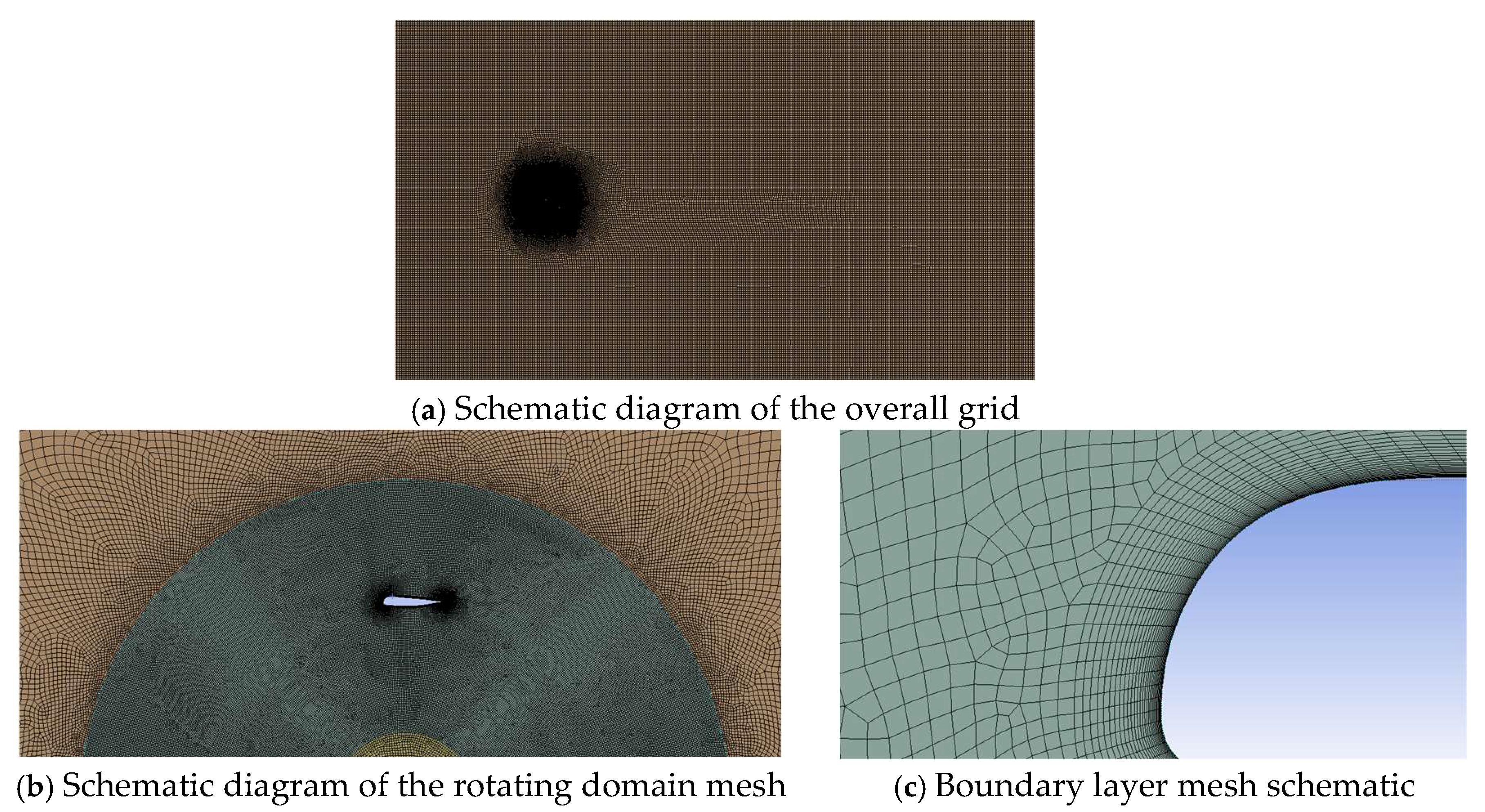

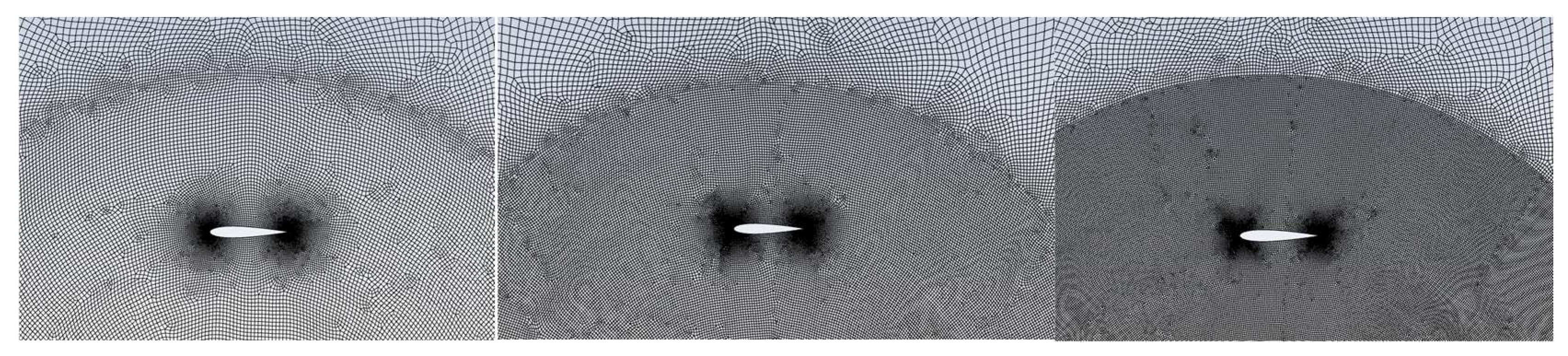

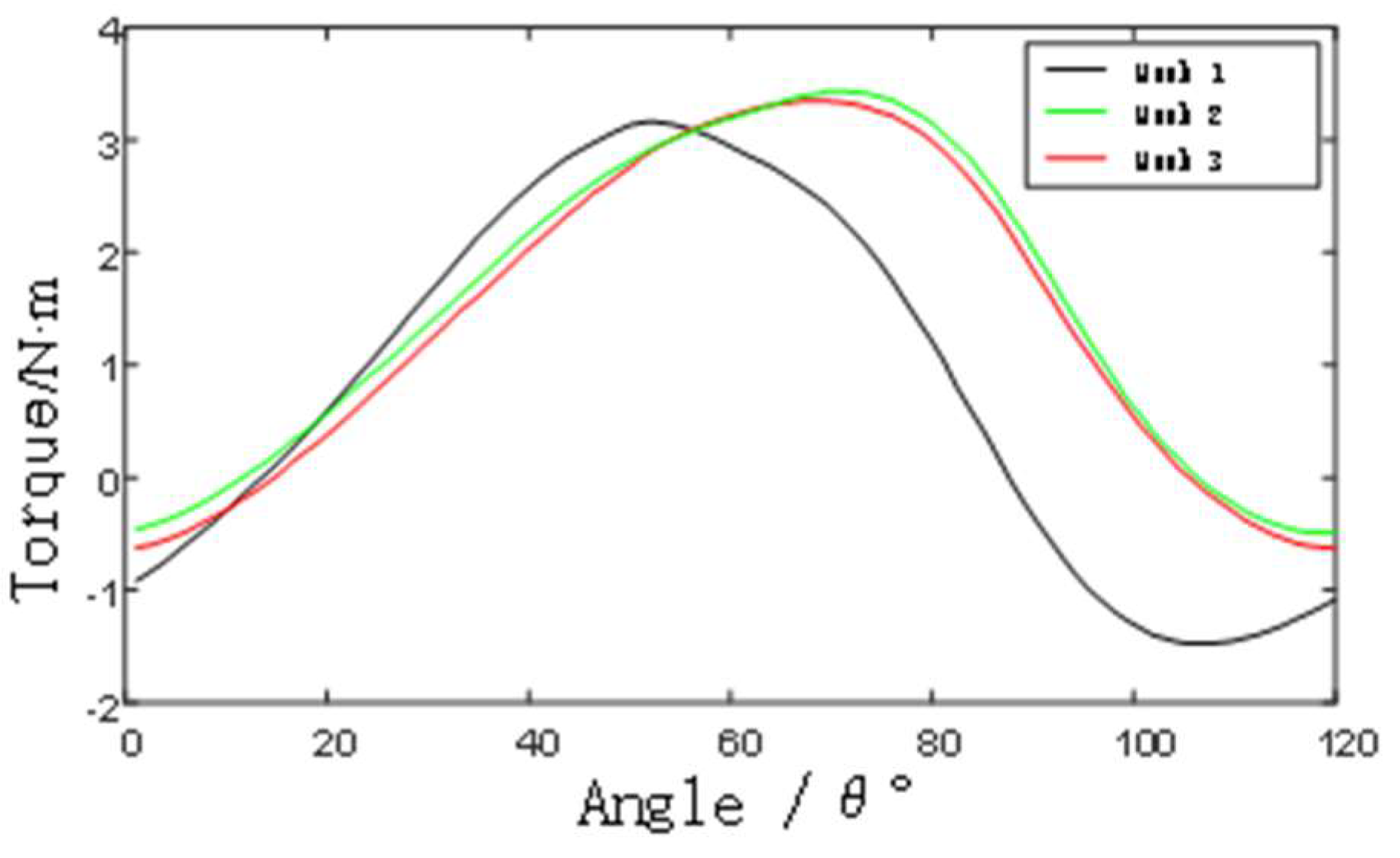

A. Grid-independent verification

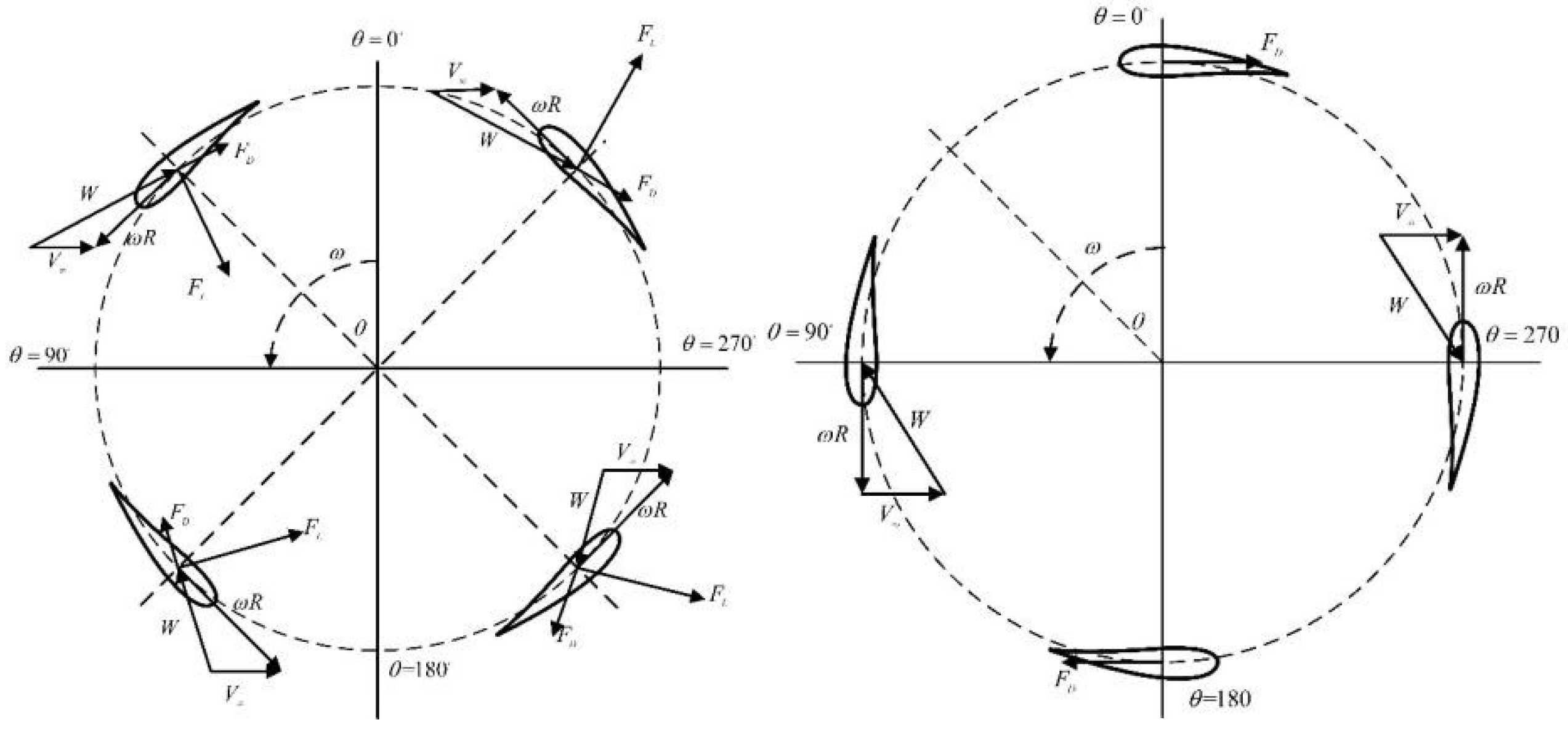

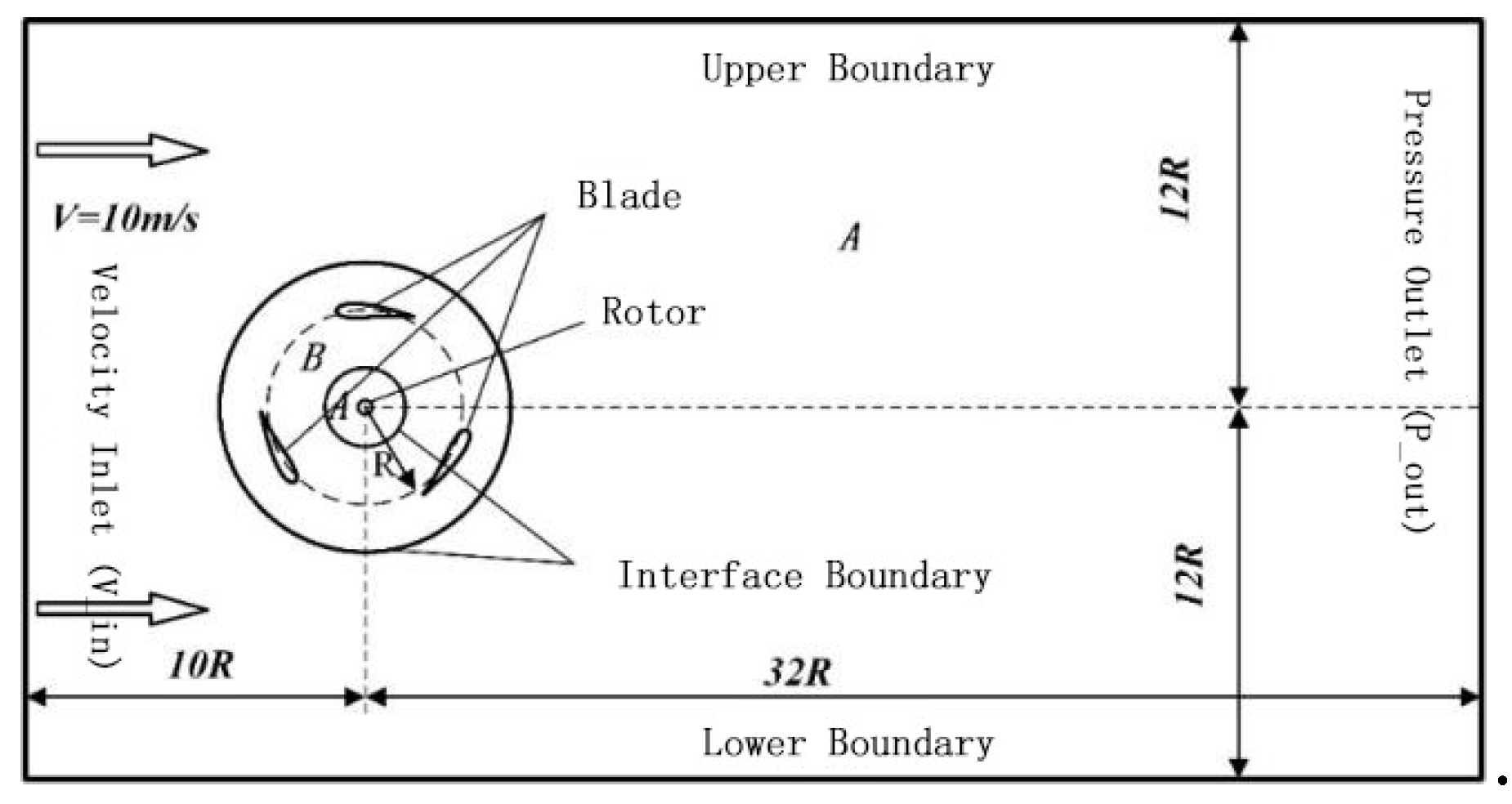

In this paper, three sets of grids are established for the model, the number of grids is 139310, 200320 and 385627, and the grid schematic is shown in

Figure 12, respectively.

The moment coefficient versus azimuth change curves for the seventh cycle of the three different grid number models are shown in

Figure 13, respectively, from which the results of the latter two sets of grid calculations basically overlap, and the gap with the first set of grids is larger. The average values of the moment coefficients of individual blades are 1.2129, 1.3266 and 1.3308, respectively, which shows that the difference of the second set of grids compared with the third set of moment coefficients is only 0.32%, and the second set of grids can satisfy the computational requirements by considering the comprehensive computational efficiency and computational accuracy.

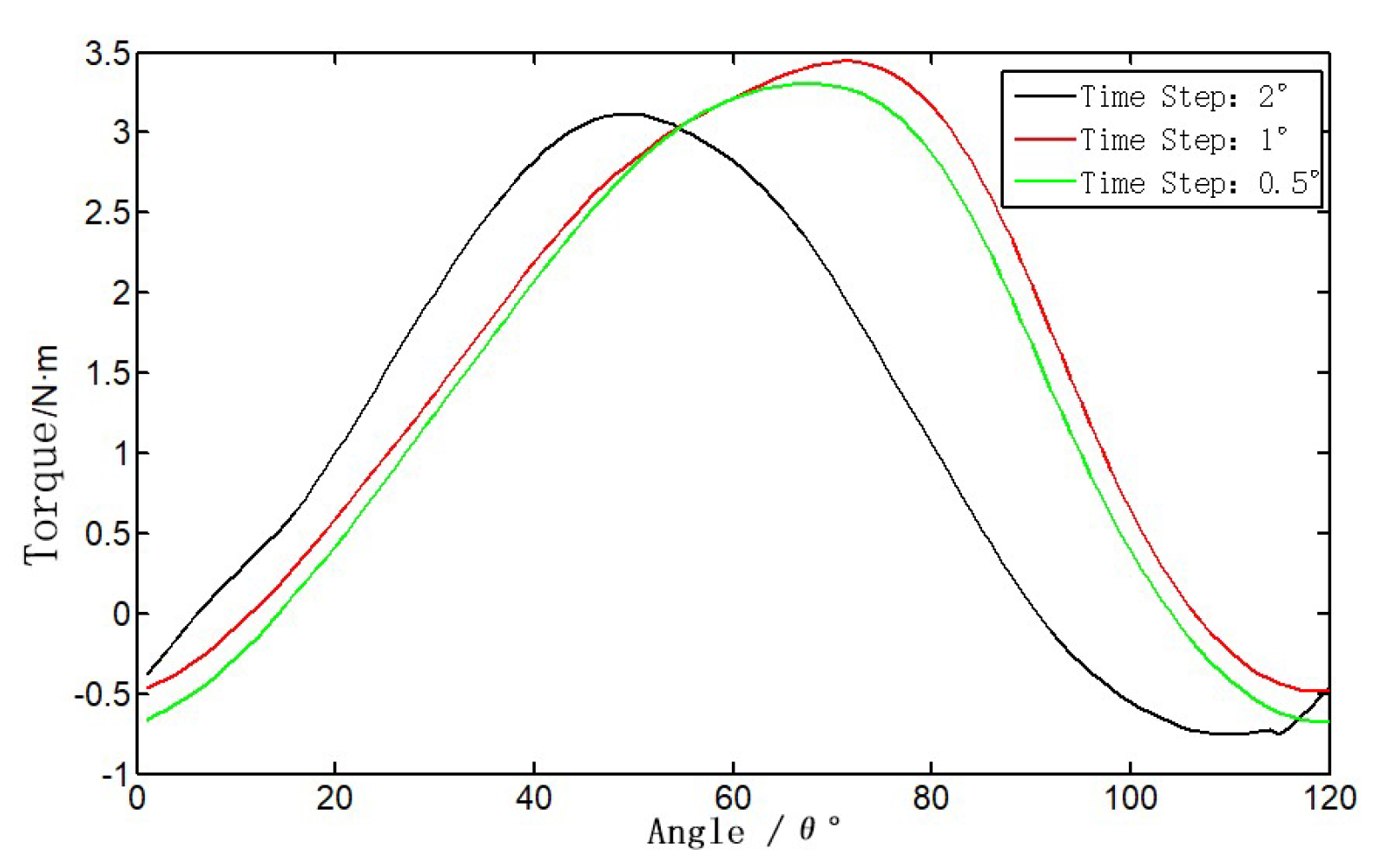

B. Verification of time-step irrelevance

In this paper, the rotating domain is simulated in a transient manner using a slip grid, and the time step also has an important influence on the accuracy of the calculation results. In this paper, for the fan tip speed ratio of 1.5 conditions, a total of three-time steps is set, and the parameters corresponding to each time step are shown in

Table 2.

The change curve of moment coefficient with the number of iterations in the seventh cycle of each time step is shown in

Figure 14, respectively. Because the number of iterations is different, the running time of the seventh cycle is chosen as the horizontal coordinate, and it can be seen from the figure that the curve of the calculated results of each time-step blade rotated by 1° and each time-step blade rotated by 0.5° is basically overlapped with that of the calculated results, and the gap is larger with that of each time-step blade rotated by 2°, but each time-step blade rotated by 0.5° increases twice the calculation time. time-step blade rotation 0.5 ° doubles the calculation time, so the final synthesis of computational efficiency and calculation accuracy considerations, choose each time-step blade rotation 1 ° as the time step used in this paper's calculations.

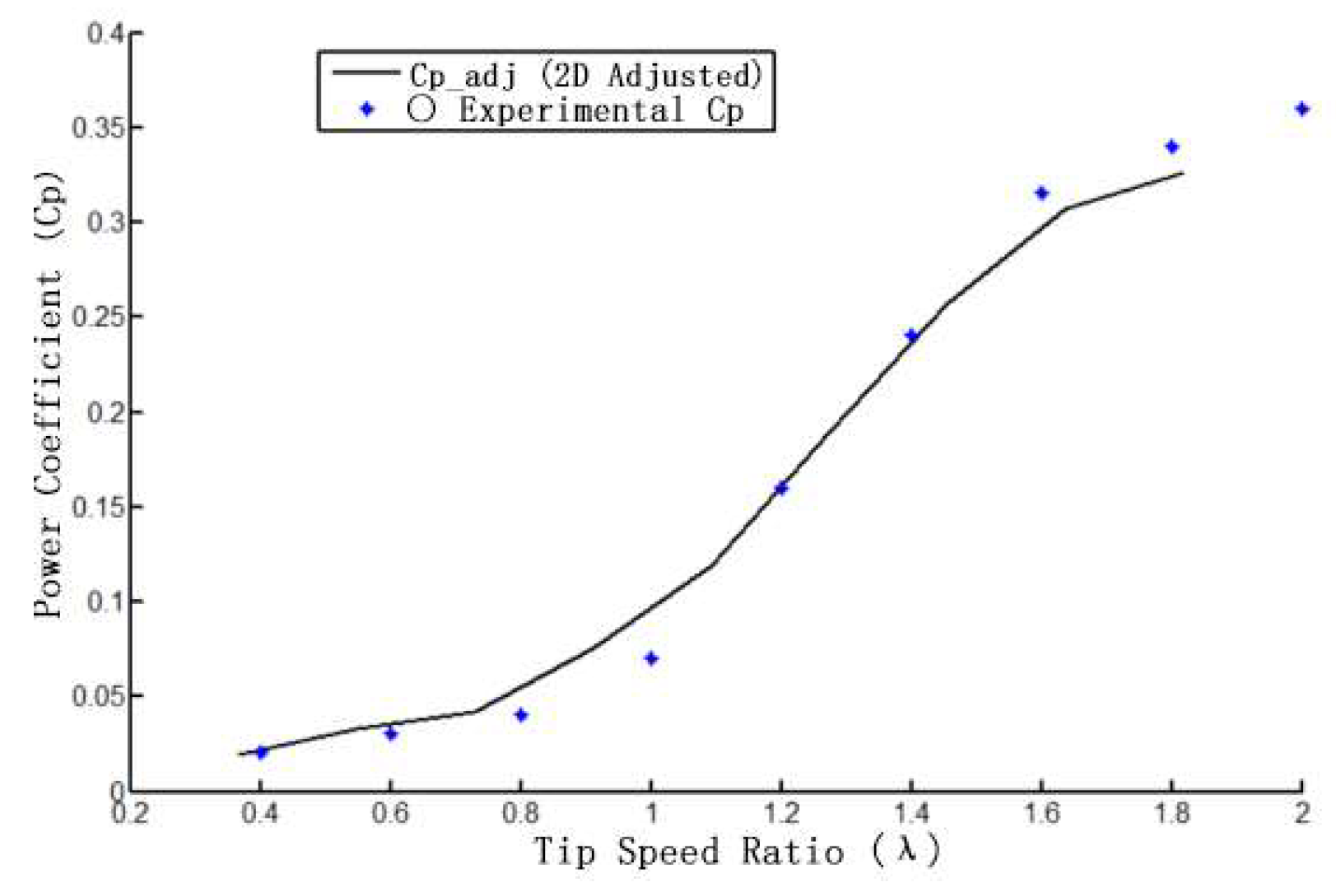

C. Comparative validation of calculation results

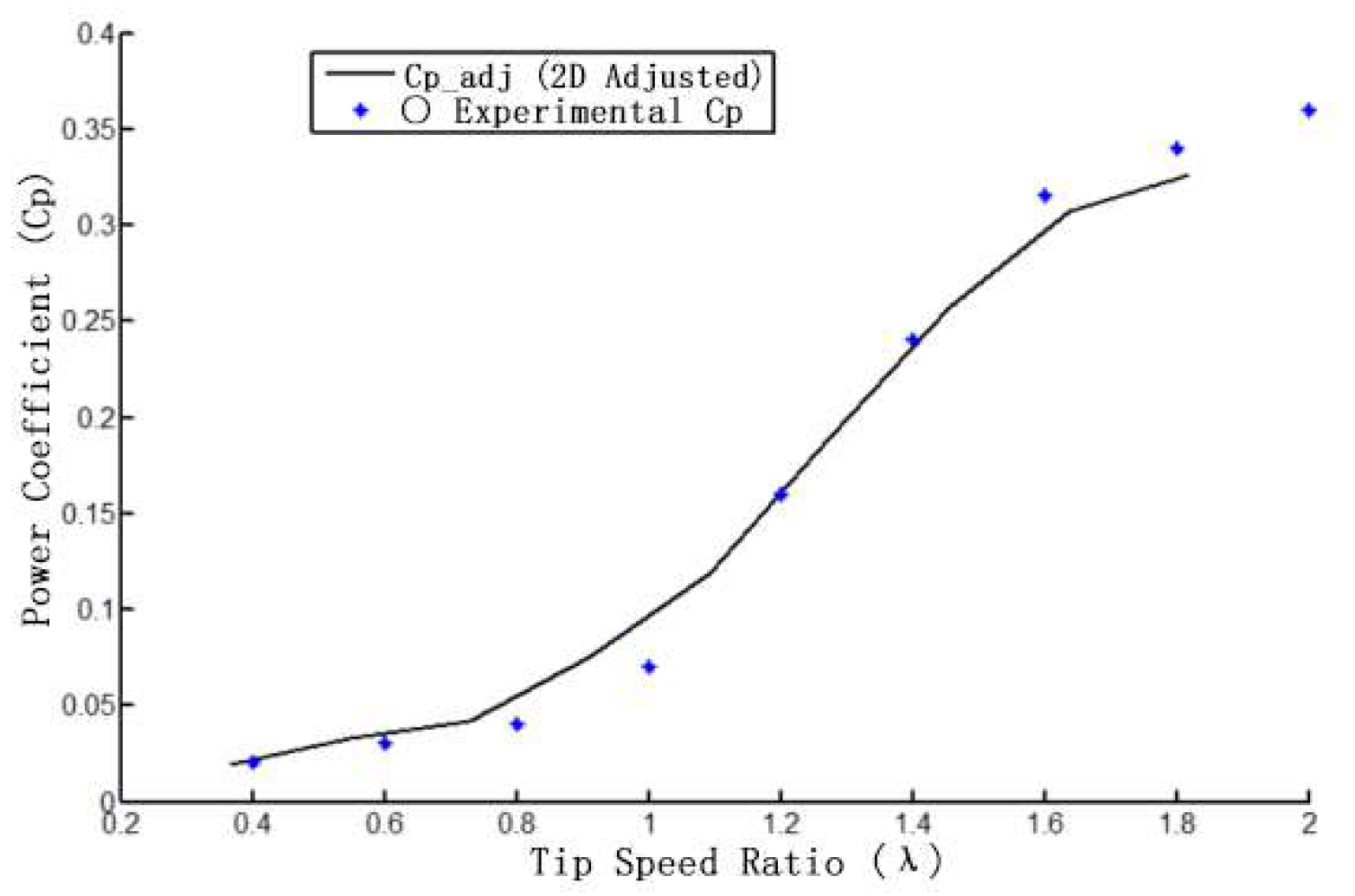

For the wind turbine tip speed ratio of 0~2, this paper adopts the established calculation model to take 5 tip speed ratio for wind turbine power coefficient calculation and get its comparison curve with the test data as shown in

Figure 15. The figure shows that the numerical calculation value is higher than the test value, and when the tip speed ratio is small, the two are closer, with the increase of the tip speed ratio, the error is getting bigger and bigger. The reason for this is that the 2D simulation assumes that the blade is of infinite length, which results in no flow along the spreading direction, while the actual wind turbine blade is of finite height, and the airflow will bypass the wingtip and flow from the surface of higher relative pressure to the surface of lower relative pressure, resulting in a pressure loss, so the test results are smaller than the simulation results is reasonable.

In response to the problem that the numerically calculated values are higher than the experimental values, Musgrove P proposed two correction factors for the turbine: one is the wind speed correction factor

k and the other is the height correction factor

τ, whose values are taken as 1.1 and 1.15, respectively, and the corrected tip-speed ratios and wind energy utilization of the turbine are:

The comparison curves of the modified power coefficient simulation values with the test values are shown in

Figure 16. From the figure, the modified two-dimensional simulation results are basically the same as the trend of change with the test values, especially the simulation values at high tip speed ratio have very little error with the test values. This further proves the accuracy of the numerical calculation method adopted in this paper.

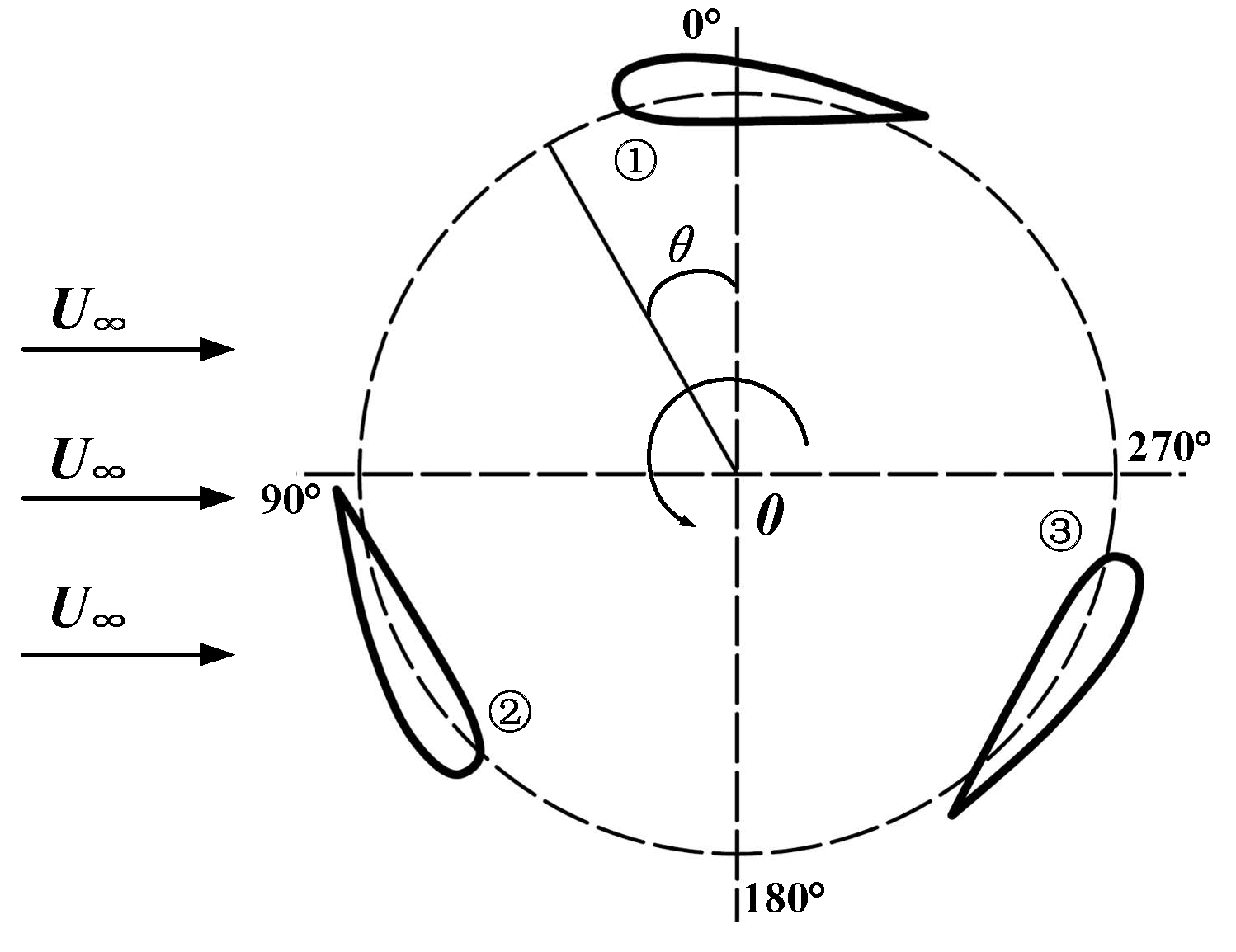

In this paper, the H-VAWT works in the high tip speed ratio working condition, comprehensive simulation analysis results and the use of installation requirements, selected the number of blades for 3, blade chord length of 0.42m, impeller rotational radius of 1.4m, this configuration as the optimization of the agent model of the basic configuration for research.

4.2. MIGA-Based H-VAWT Airfoil Optimization

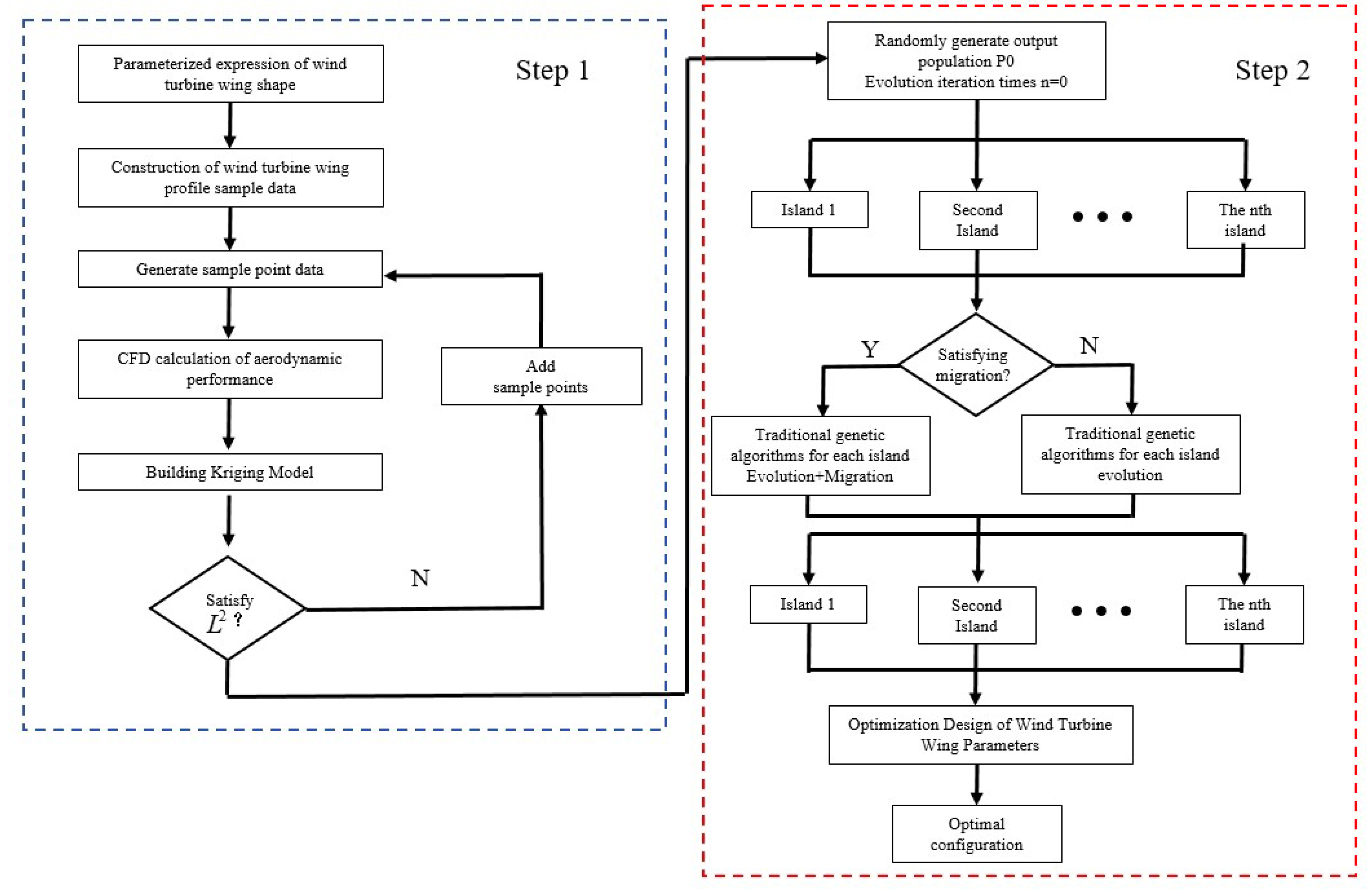

Multi-Island Genetic Algorithm (MIGA) deals with complex optimization problems by dividing the population into multiple independently evolving islands, each of which independently performs the selection, crossover and mutation operations of traditional genetic algorithms (GA). Each island independently performs the selection, crossover and mutation operations of traditional GA. Individuals migrate between islands with a certain probability, to maintain the diversity of the population and effectively avoid the phenomenon of premature convergence, thus improving the ability of global optimization. Aiming at the problem of high computational cost of CFD evaluation in wind turbine airfoil optimization, an agent model is introduced to replace CFD simulation to reduce the computational cost and improve the optimization efficiency.

The optimization process begins with the construction of CFD sample data for the wind turbine, establishing a CFD database based on the initial airfoil to provide training data. Subsequently, an initial population P0 is randomly generated, and the evolution generation count is set to n =0. During the evolutionary process, the multi-island parallel evolution mechanism enables independent GA optimization within each island. After each generation, the system determines whether to perform migration operations: if migration conditions are met, individual exchanges occur between islands to enhance global search capabilities; otherwise, independent evolution continues. This process iterates until the maximum generation limit or convergence criteria.

In the optimization process, the agent model plays a central supporting role in the evolution of the MIGA. When the genetic algorithm generates a new population, the proxy model can quickly predict the aerodynamic performance of the airfoil, thus reducing the frequency of direct calls to the CFD simulation and significantly reducing the computational cost. After the optimization is completed, the optimal individuals need to be verified by CFD to check the prediction accuracy of the proxy model. Based on the validated optimization results, the key parameters of the airfoil are further adjusted, and the optimal airfoil configuration is finally determined through comprehensive evaluation to complete the airfoil optimization design. The coefficient of determination R2 measures the accuracy of the kriging substitution model and can be expressed as:

In the formula, is the number of test sample points, is the experimental value, is the estimate of the proxy model, and is the mean of the experimental point set.

The co-optimization flow of MIGA and the proxy model is shown in

Figure 17, which demonstrates the significant advantages of the method in the airfoil optimization. MIGA significantly enhances the global search capability through the parallel evolution and migration strategy, while the introduction of the proxy model significantly reduces the frequency of CFD simulation calls. This efficient coupling method can achieve high-quality airfoil optimization under limited computational resources and provides a reliable optimization strategy for wind turbine aerodynamic design.

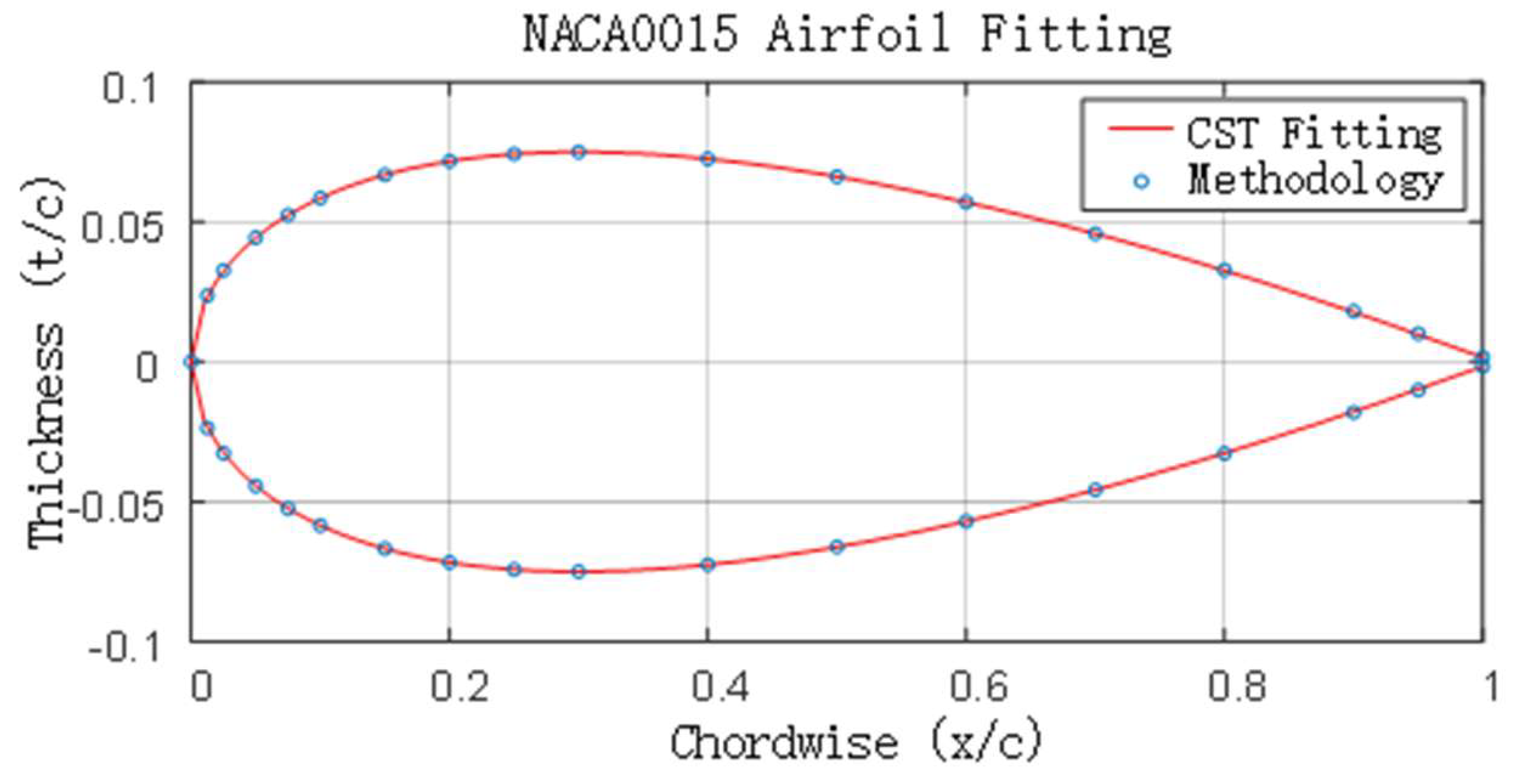

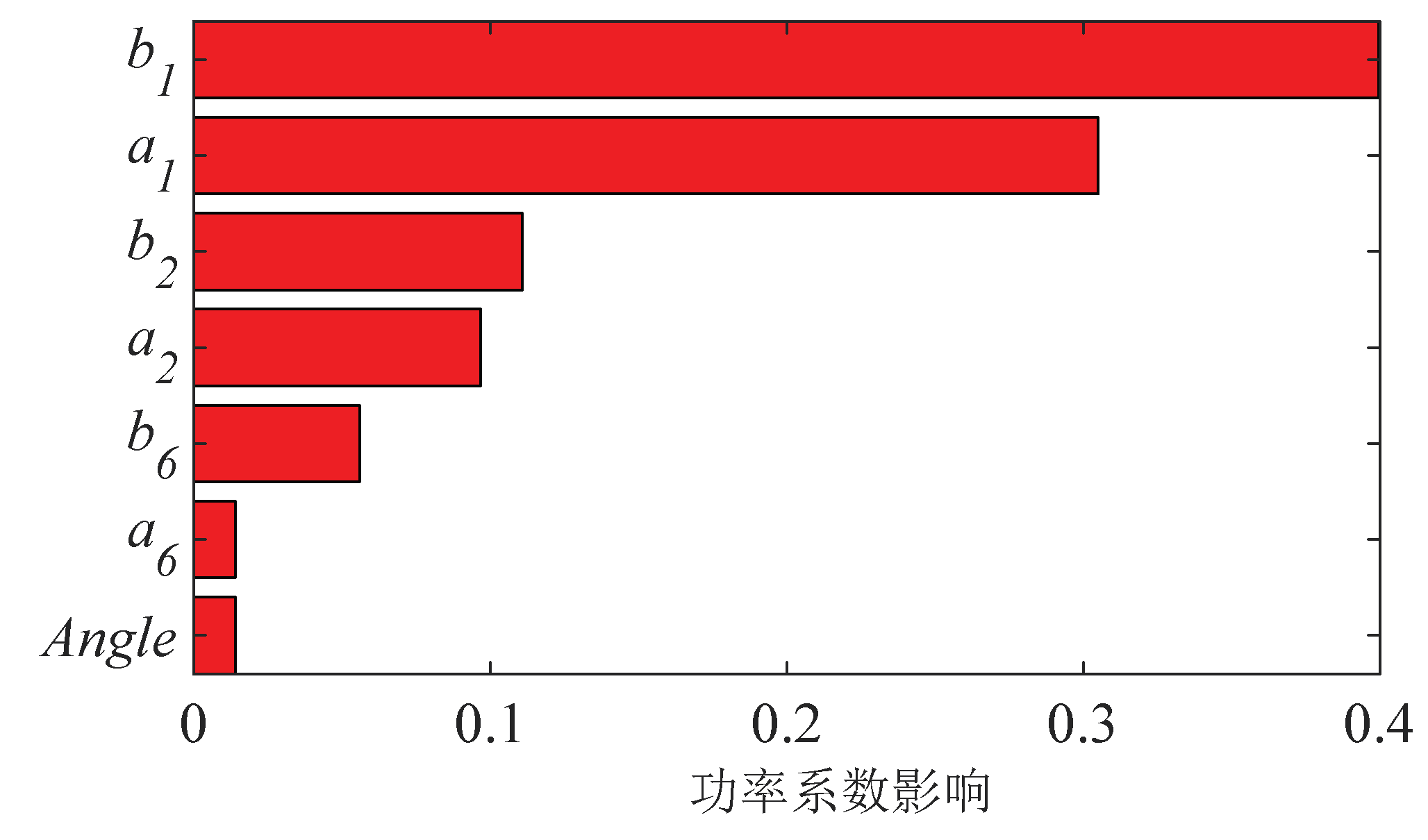

The H-VAWT airfoil in this paper contains a total of 12 parameters of the CST method and one parameter of the mounting angle, and from the previous analysis, it is known that the greater impact on the aerodynamic performance of the wind turbine is the leading edge radius, the airfoil thickness, the trailing edge shape and the mounting angle, and each parameter of the CST method has a specific meaning, so in this paper, we choose a total of seven parameters, namely, a1, a2, a6, b1, b2, b6 and the mounting angle α as the optimization variables, the sample points for agent model construction are determined as ten times the number of parameters, i.e., 70 sample points, and the error analysis points are taken as 10.

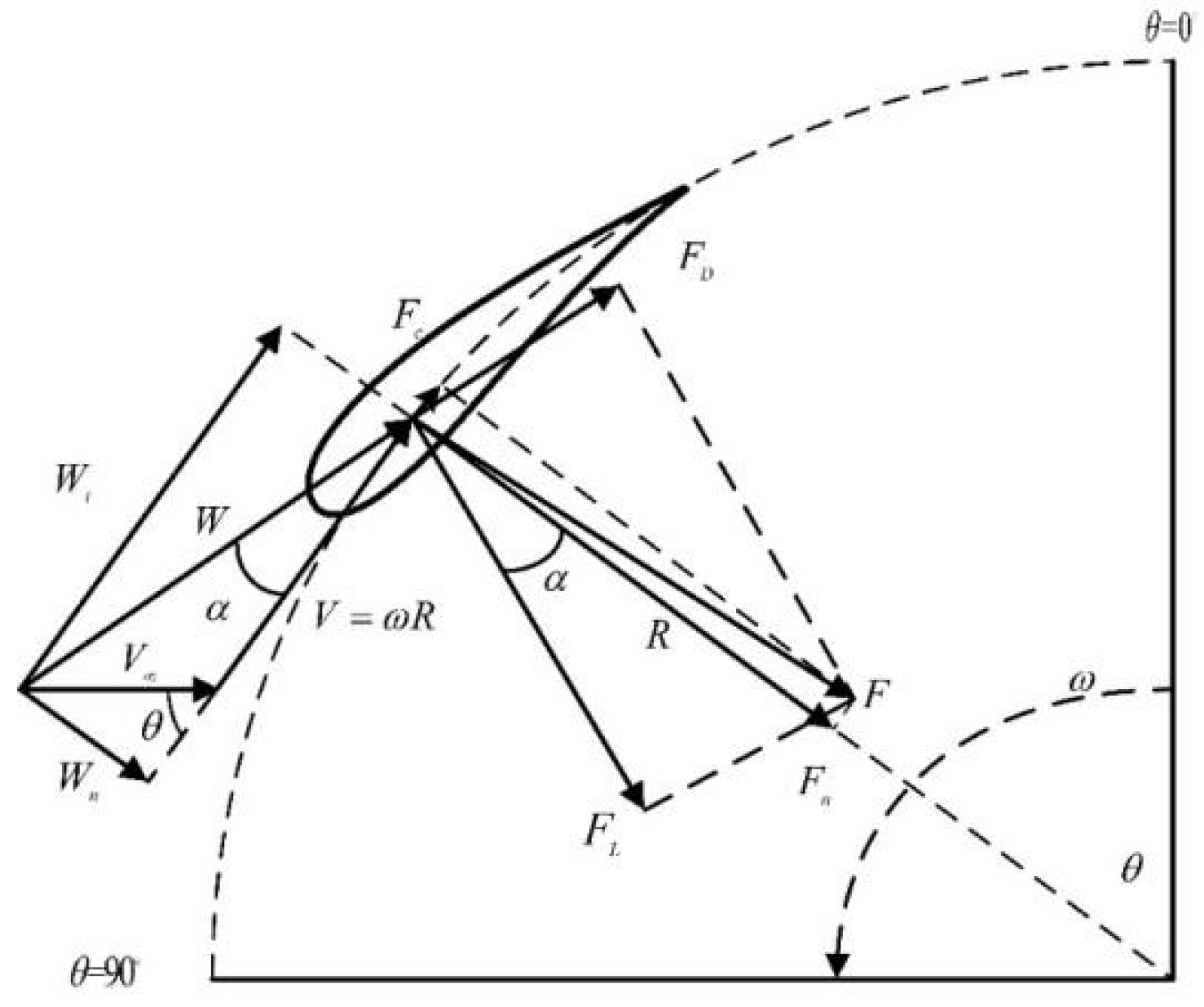

The sensitivity analysis of the influence of each parameter on the power extraction coefficient of the wind turbine is shown in

Figure 18 and

Figure 19, which shows that the power extraction coefficient is the most sensitive to the radius of the leading edge, followed by the relative thickness, and finally the shape of the trailing edge, so that the reasonable design of the radius of the leading edge is the most critical to the power extraction coefficient of the wind turbine.

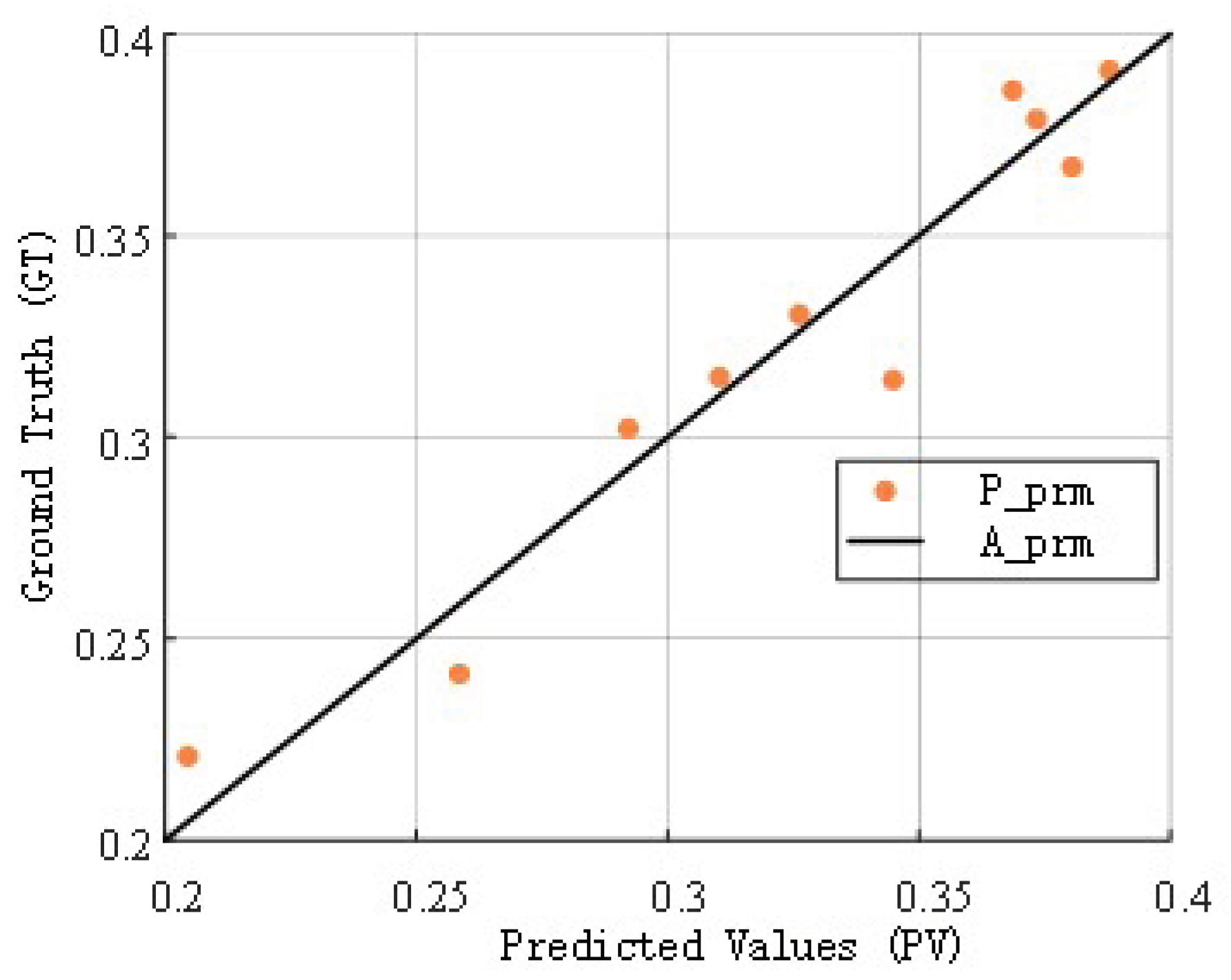

Figure 18 shows the results of the error analysis of the constructed proxy model, and the

L2 value of the error analysis is 0.91368, which is generally accepted in engineering greater than 0.8, and the results show that the fitting accuracy is high, and it can be used to optimize the design.

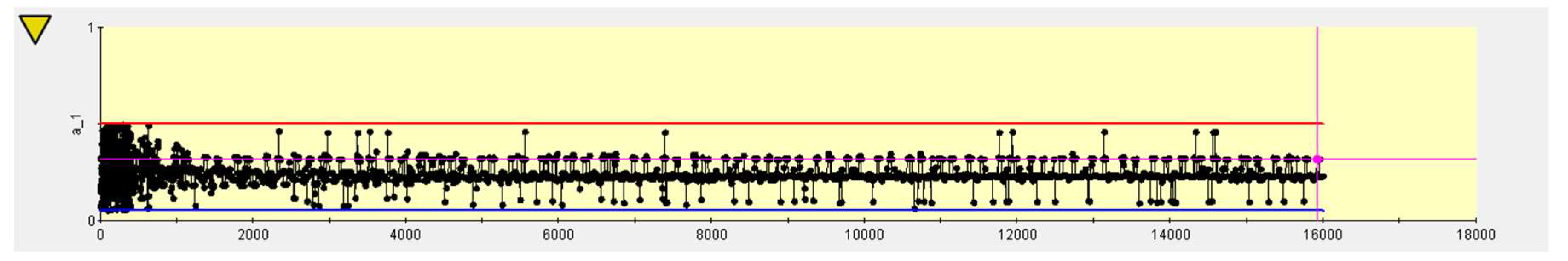

Taking 10 populations with 40 samples for each population and a total of 40 iterations, the final parameters of the two optimized configurations are shown in

Table 3, respectively. As shown in

Figure 20 and

Figure 21, the optimization was calculated for a total of 16,000 times, and basically reached convergence around the 4,000th time, compared with the original configuration, the power extraction coefficients of the optimized configuration 1 were improved by 14.2%, and the power extraction coefficients of the optimized configuration 2 were improved by 11.6%, and the two configurations both played a better optimization effect.

Figure 20.

Iterative diagram of the optimization process for optimized configuration 1.

Figure 20.

Iterative diagram of the optimization process for optimized configuration 1.

Figure 21.

Iterative diagram of the optimization process for optimized configuration 2.

Figure 21.

Iterative diagram of the optimization process for optimized configuration 2.

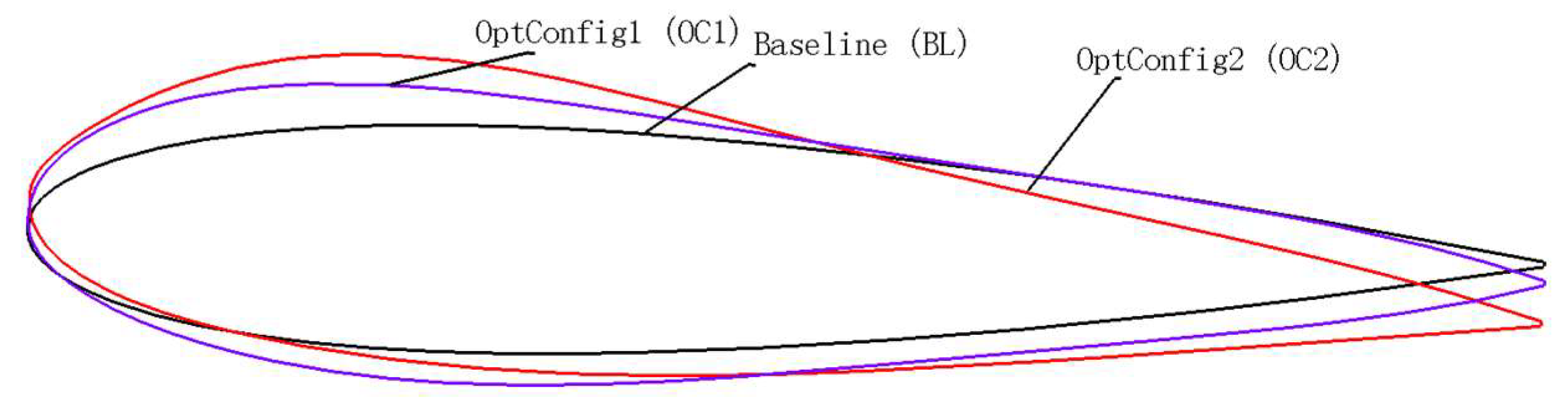

Comparison of optimized front and rear airfoil shapes is shown in

Figure 22. Compared to the original symmetric airfoil, both optimized airfoils have positive mounting angles, and the upper airfoil is fuller than the lower airfoil, and the thickness of the trailing edge is relatively larger, and the relative thickness and mounting angle of the optimized configuration 2 are smaller than those of the optimized configuration 1.

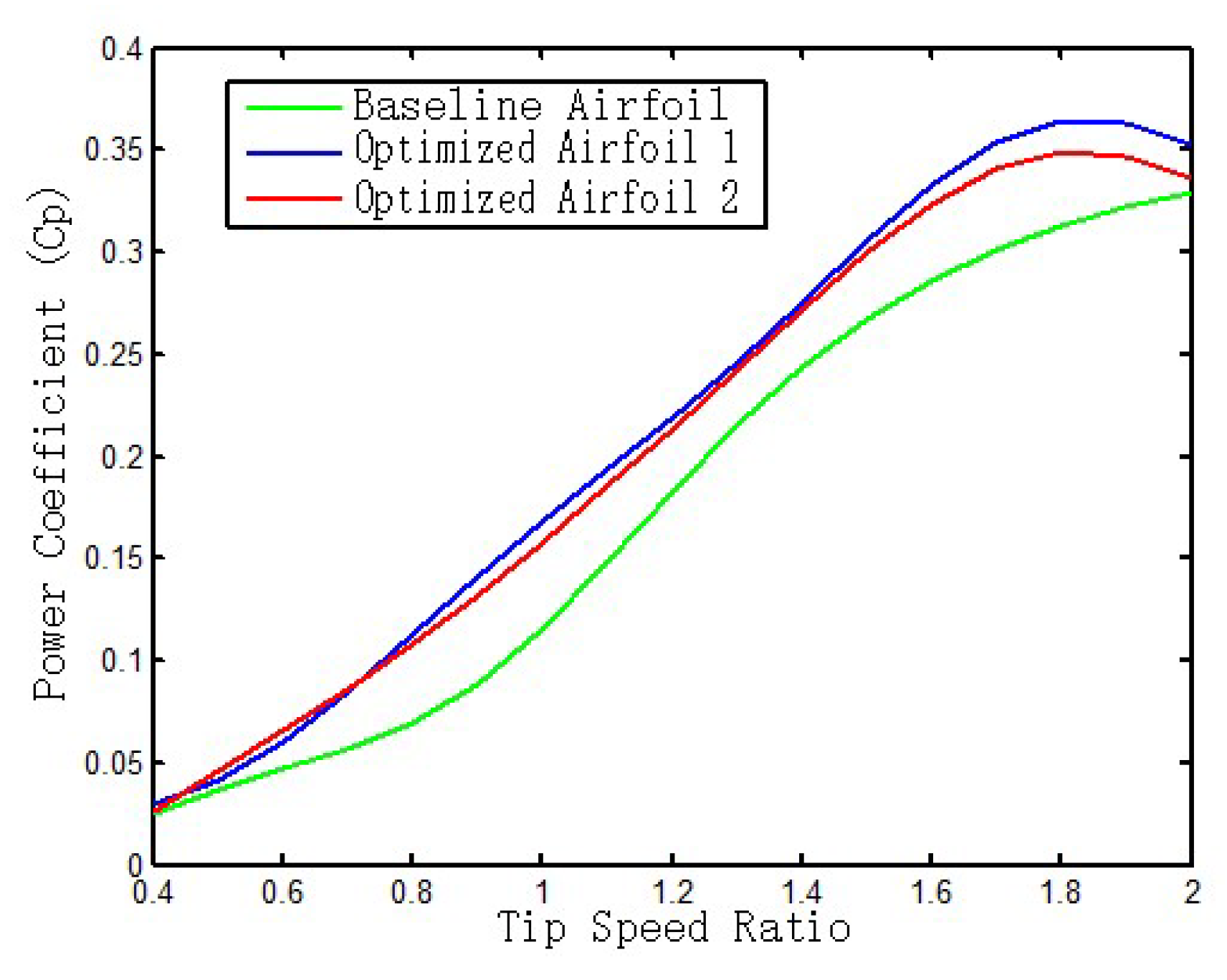

Figure 23 demonstrates the variation pattern of the wind turbine power coefficient with tip speed ratio calculated using McLaren's correction formula before and after optimization. From the figure, it can be seen that the power coefficients of both optimized airfoils are significantly better than the original airfoils in the whole range of tip speed ratios. Under the low tip speed ratio condition, the power coefficient enhancement of optimized airfoil type 1 and optimized airfoil type 2 are basically equal, but the maximum power extraction coefficient of optimized airfoil type 1 is larger than that of airfoil type 2. The results show that the two optimized airfoils have similar starting performance under low tip speed ratio conditions, but from the aerodynamic aspect of high tip speed ratio, the optimized airfoil 1 is optimized for airfoil 2.

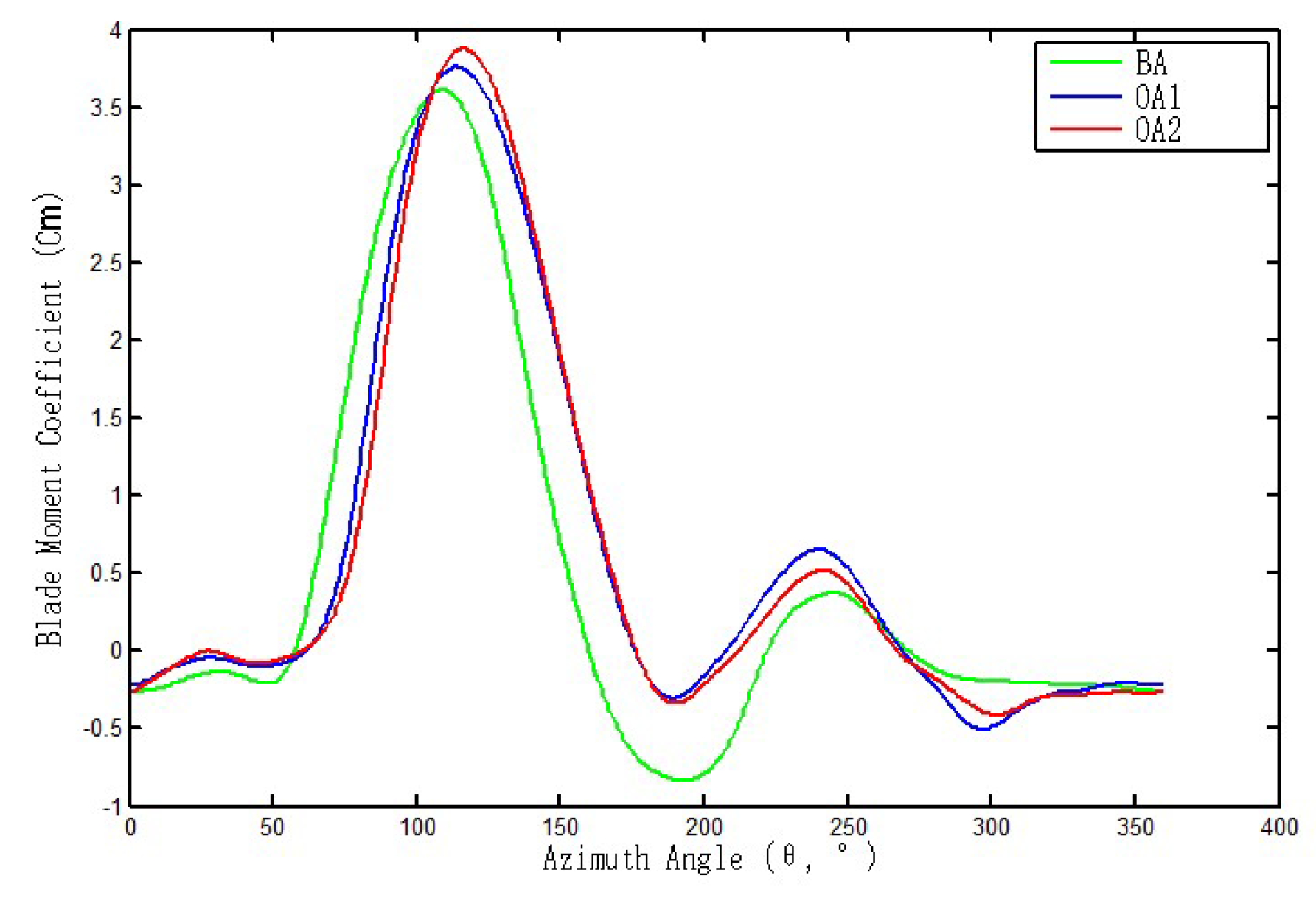

Figure 24 demonstrates the variation rule of moment coefficient with azimuth angle for individual blades before and after optimization when the tip speed ratio is 1.8, and the horizontal coordinate indicates the azimuth angle of blade rotation. The results show that the main power output of the blades is concentrated in the 50°~180° azimuth interval, and the power generated by the remaining azimuth region is smaller. Due to the cyclic rotational characteristics of the three-bladed wind turbine, each blade will enter the 50°~180° azimuth region alternately, so as to maintain the continuous operation of the wind turbine effectively. After optimization, the wind turbine not only improves the maximum moment coefficient of the blades, but also improves the moment coefficient of the blades in most of the azimuthal angles, so that the power coefficient of the wind turbine as a whole is improved.

4.3. Optimization Results Analysis

A. Comparative analysis of pressure distribution

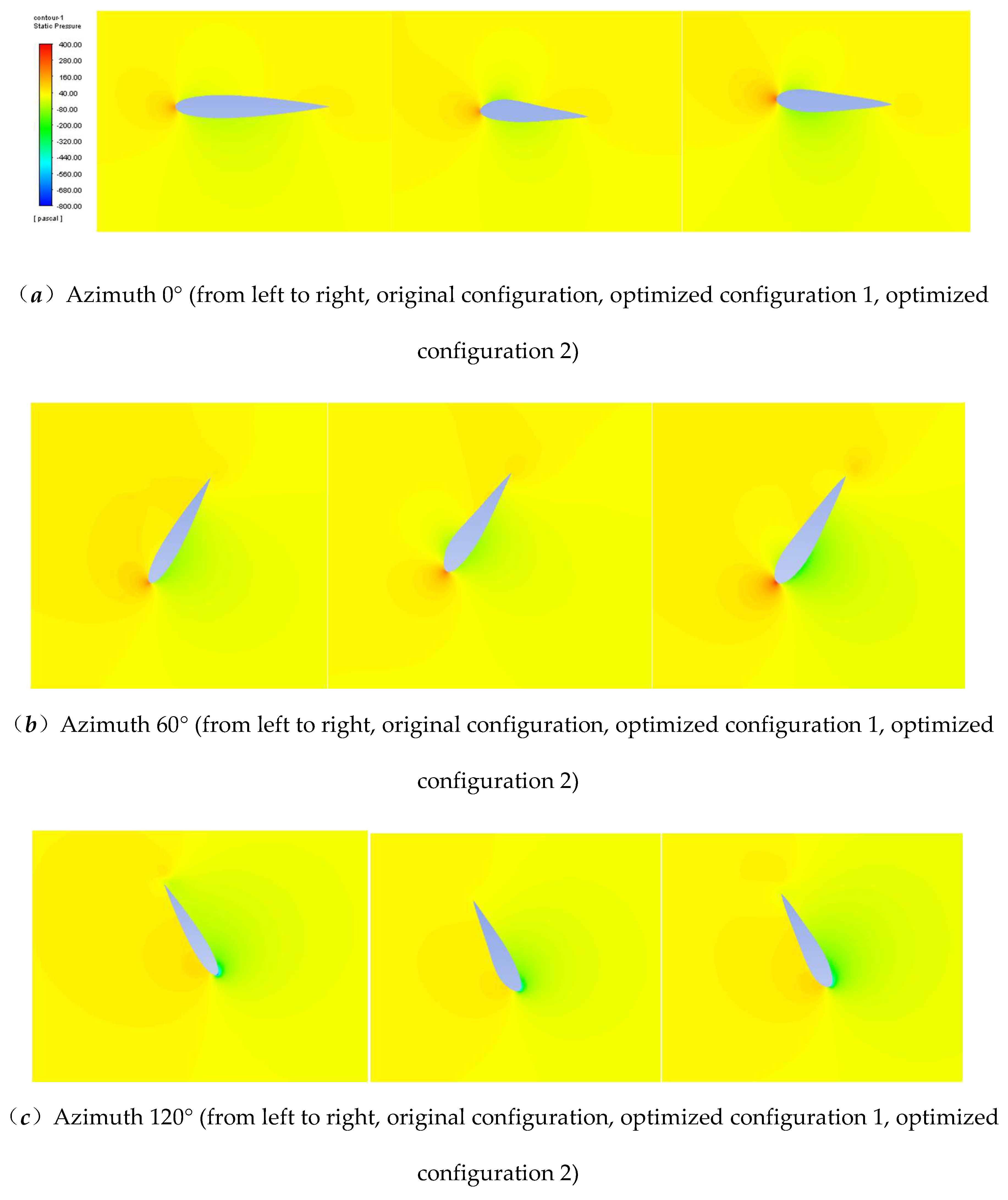

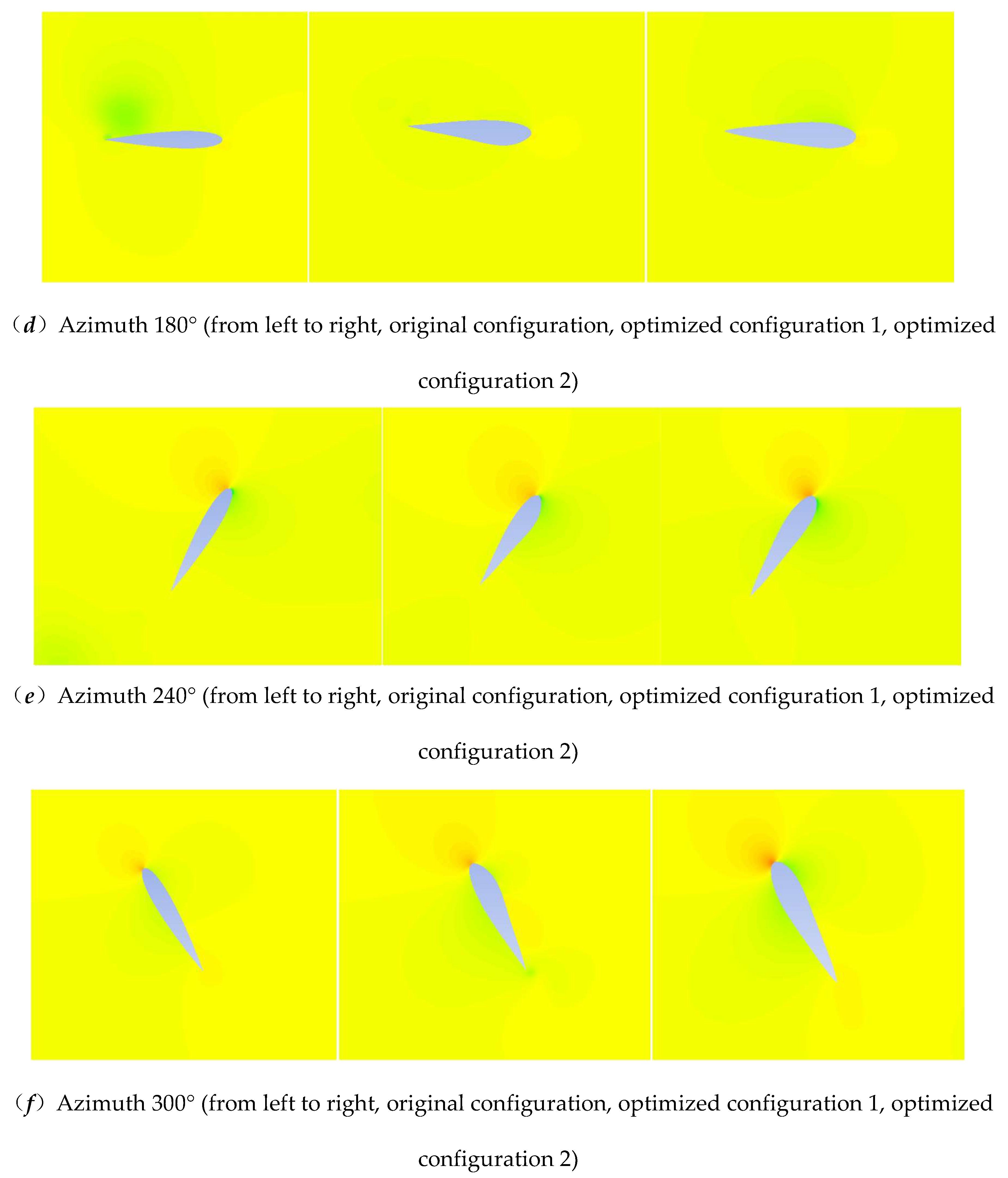

Figure 25 shows comparatively the pressure distribution clouds of the original configuration, optimized configuration 1 and optimized configuration 2 at different azimuthal angles when the tip speed ratio is 1.8, and the legends are the same in all the figures for the sake of comparison. The comparative analysis shows that the optimized H-VAWT exhibits significant aerodynamic performance enhancement at different azimuth angles. Specifically, in the range of 60°-120° key azimuth angle, the optimized blade surface pressure gradient distribution is more uniform, the leading edge high-pressure zone area is reduced, and the trailing edge low-pressure zone pressure value is increased, which effectively reduces the pressure drag loss, and overall improves the wind energy utilization of the wind turbine. At the same time, the results of the flow field diagram show that the optimized design effectively reduces the flow separation and turbulence area, the flow line is smoother, and the flow adhesion on the surface of the wind turbine blade is improved, which reduces the drag and improves the performance. These optimization results show that the improved airfoil design has significant advantages in pressure distribution and aerodynamic efficiency, which enhances the overall performance and energy capture capability of the wind turbine. The main effect of the optimization is to improve the lift effect of the airfoil in an integrated way, since the airfoil angle of approach is not changed, so the direction of the lift force remains unchanged, which in turn can provide a larger torque.

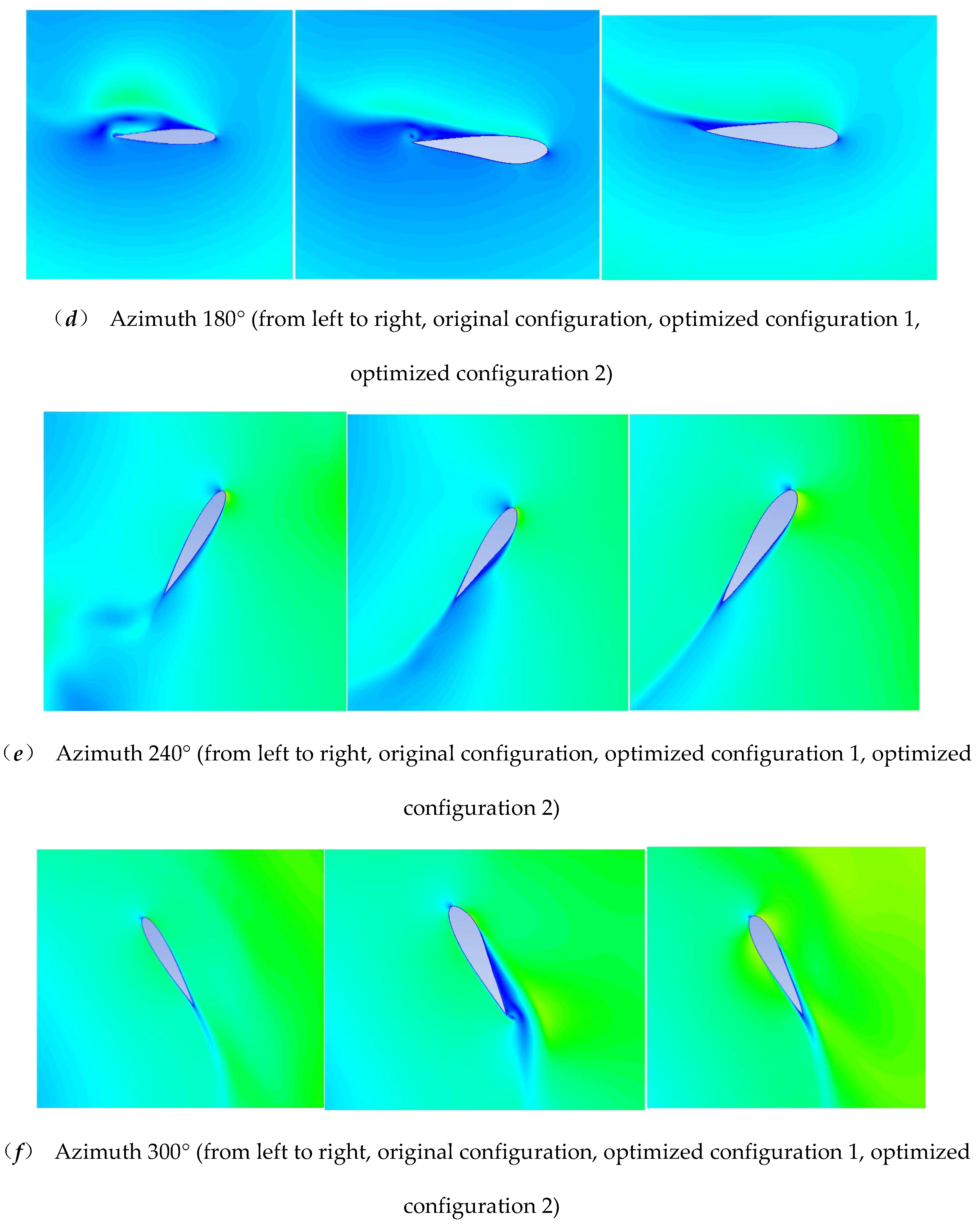

B. Comparative analysis of speed distribution

Figure 26 represents the comparison of the velocity distribution cloud plots of the original configuration, optimized configuration 1 and optimized configuration 2 at different azimuthal angles when the modified tip speed ratio is 1.8, respectively, and the legends of all the plots are the same in order to facilitate the comparison, from which it can be seen that all the three configurations are rotating for one week. According to the velocity cloud plots at different azimuthal angles, the optimized H-VAWT shows significant improvement in fluid characteristics.

The optimized design results in a more uniform flow over the blade surface, especially at the 0° and 60° positions, where the flow structure is smoother, reducing vortices and flow separation phenomena, thus reducing energy losses. At the 120° position, the optimized design significantly improves the adhesion of the flow lines, reduces unnecessary energy consumption, and enhances the aerodynamic efficiency. Further analysis of the flow distribution at azimuth angles of 180° and 240° shows that the optimized model exhibits smoother flow at the trailing edge of the blade and near-tail region, improving the wind energy conversion capability. The explanation for the more pronounced vortex shedding phenomenon of the original configuration after azimuth angle 240° may be related to the changes in the design parameters of the airfoil. Specifically, the primitive configuration at this azimuth angle may lead to accelerated changes in the airflow or increased local pressure differences, which exacerbate airflow separation and lead to more pronounced vortex shedding in the wake.

Finally, at 300°, the optimized design similarly improves the flow uniformity, reduces vortex formation, and enhances the wind energy capture capability of the blade. Overall, the optimized design reduces the flow resistance and energy loss by improving the fluid characteristics of the wind turbine, thus effectively enhancing the overall performance and efficiency of the wind turbine. With an azimuth angle greater than 90°, the airfoil appears to stall and a trailing vortex is generated at the trailing edge, which increases drag and reduces aerodynamic performance. The optimized airfoil is able to provide greater torque by improving the flow field characteristics, weakening the airflow separation, reducing drag, and reducing the negative torque generated by the drag, which also demonstrates the effectiveness of the optimized design in reducing drag and increasing torque.