1. Introduction

Interdisciplinary teaching approach fosters students in creating a coherent body of knowledge, rather than fragmented islands of knowledge corresponding to different disciplines. Many scientific concepts should be faced through investigations across different fields, in order to be understood in depth or to know about their different interpretations.

A great support to interdisciplinary studies is provided by those studies that examine a discipline such as chemistry from historical, philosophical or social points of view. In the last case, students analyze the social, environmental or economic impact of some chemical processes or products. In those studies, context plays a fundamental role: students are encouraged to evaluate particular situations, usually in response to ethical questions, while learning at the same time the key concepts of chemistry and the related laboratory practices.

Historical studies can also be considered “context studies”, because they show chemistry as a human enterprise, revealing its great influence in guiding governments’ decisions, promoting social progress, influencing artistic production. Overall, the contribution of the history of chemistry to chemical education research is to convey the dynamism of the discovery and to foster a well-rounded understanding of key concepts following their evolution over time.

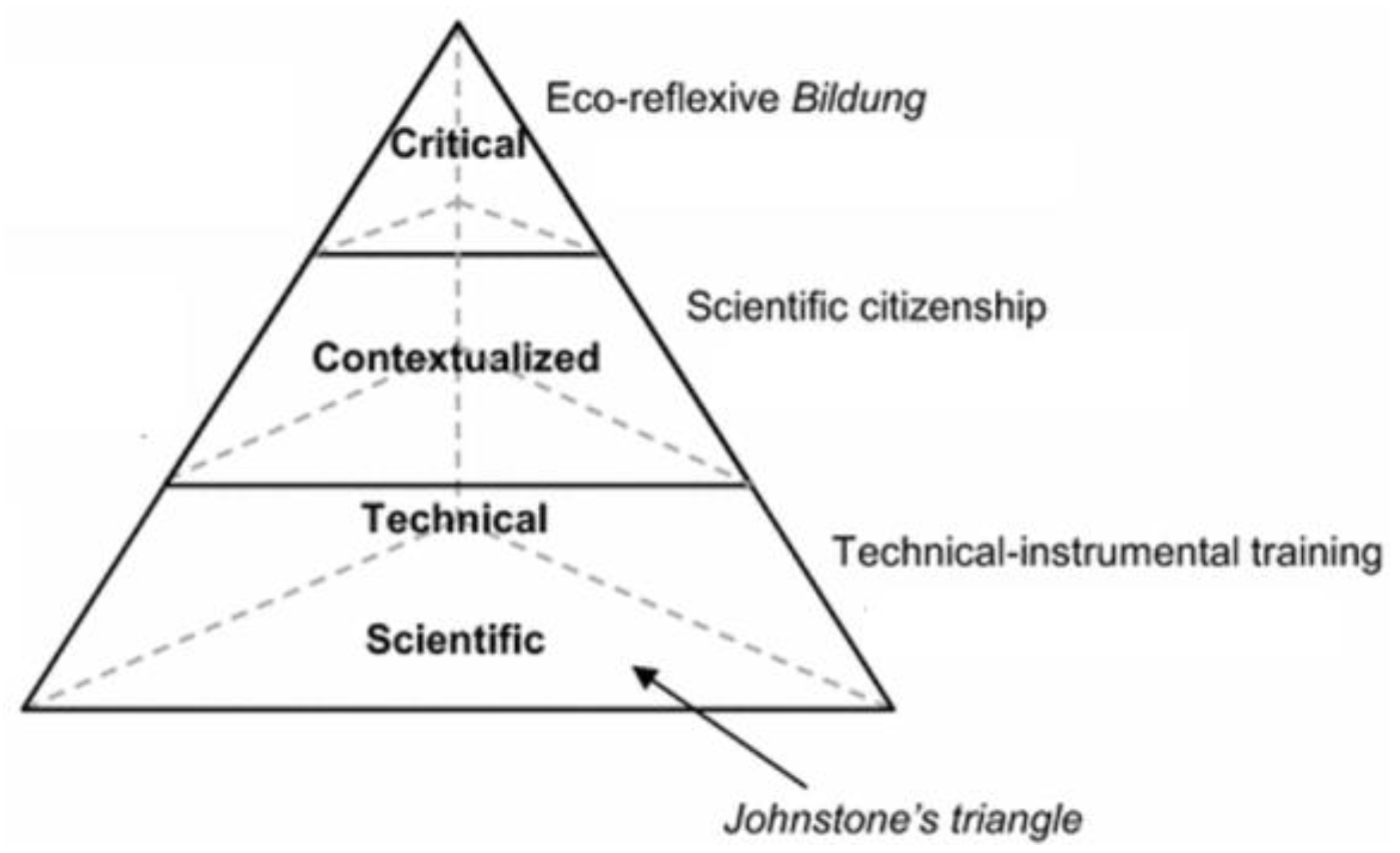

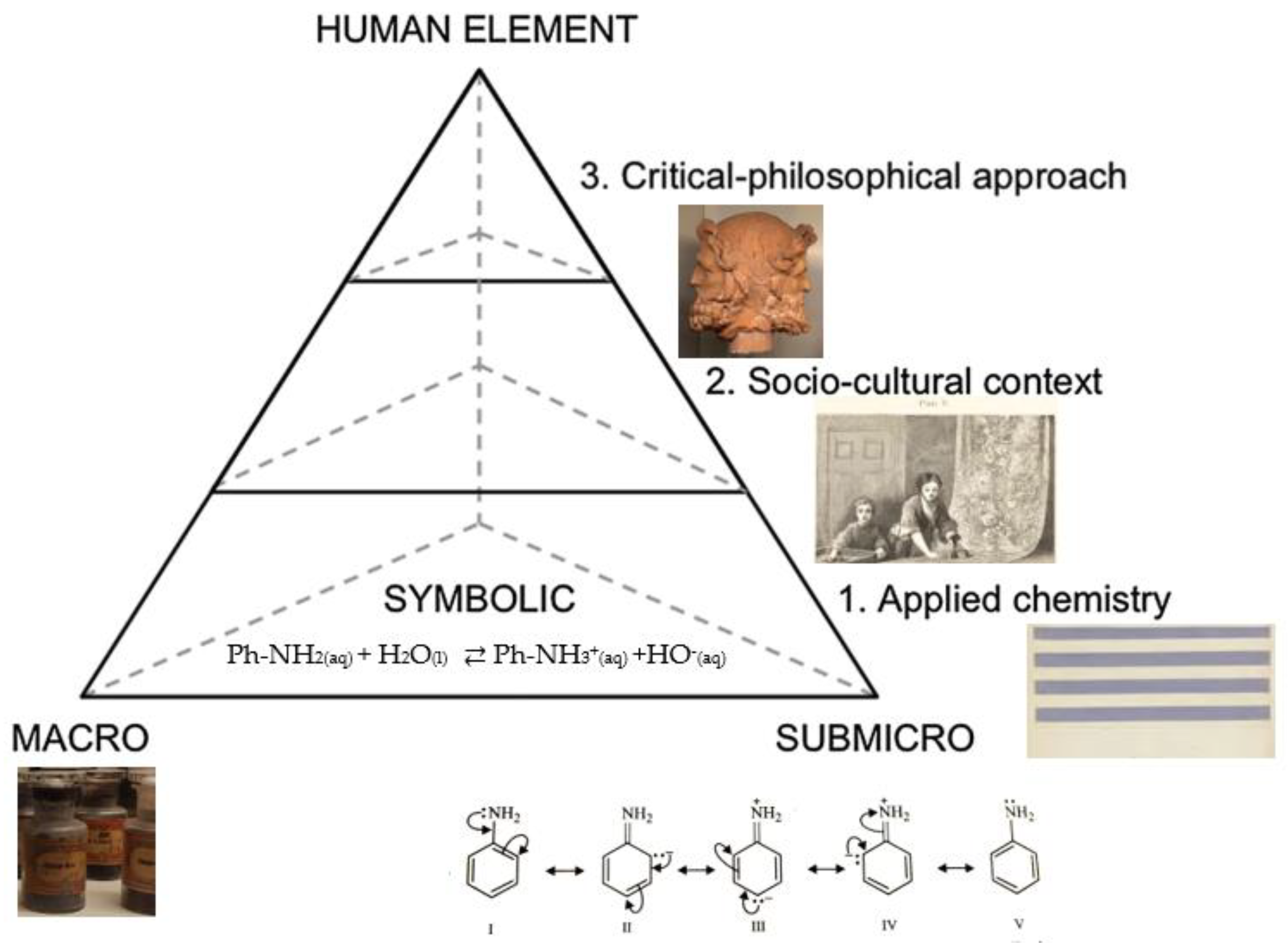

Teaching chemistry in a so wide context must not deprive this discipline of its intrinsic peculiarity. Chemistry shares many features with other sciences, but it has various unique features [

1]. It is therefore appropriate to begin the discussion of a topic starting from the three main levels of representation typical of chemistry: macroscopic, sub-microscopic and symbolic levels [

2]. Afterwards, it is possible to expand the range of action by a tetrahedron model based on this triangle, where the top represents the human element [

3]. Subsequently, the top can be subdivided into three other levels: applied chemistry, socio-cultural context, and critical–philosophic approach [

4]. This working scheme translates into six levels of analysis, represented in

Figure 1, where “technical-instrumental training”, “scientific citizenship”, and “eco-reflexive Bildung” refer to the corresponding levels within a general chemical education framework.

The aim of this work is to analyze through these six levels the nature and impact of aniline (and other synthetic dyes) in various fields. The synthetic dyes discovery and industry [

5] is particularly important for a Bildung-focused chemistry education [

6], because of its profound influence on society, economy, health, art. The educational theory of Bildung, with its rich history spanning over two centuries, has evolved significantly in both its theoretical and practical applications. While its integration into international science education literature has been gradual, the escalating ecological and technological complexities of modern society, coupled with the proliferation of misinformation, underscore the urgent need to re-examine and apply the principles of Bildung within science education [

7]. The path illustrated here on aniline (

Figure 2) can be used, with various additions and/or subtractions, as a teaching sequence in secondary school, in Bachelor’s introductory organic chemistry or within the courses of history, philosophy and ethics of chemistry - unfortunately not very widespread in higher education despite the need for them [

8]. Obviously, this article does not claim to be exhaustive; rather, it can be used as a framework to adapt teaching action to different levels and contexts. It contains also some examples that can be used as exercises in order to further clarify some concepts.

2. Macroscopic Level

In particular for secondary students, the macroscopic level is the most useful for a first approach to organic synthetic dyes.

2.1. Physical and Chemical Properties

Aniline (or aminobenzene or phenylamine) is the simplest of the aromatic amines; it is a colorless, oily liquid that darkens in air (when stored for a long period, it can take on a more or less dark yellow color).

Table 1 lists some physical and chemical properties [

9]:

Aniline is harmful to the environment and human health if ingested or inhaled [

9]; as shown by

Figure 3 from left to right, it is: toxic (by skin contact, by ingestion, by inhalation), corrosive (it causes skin burns and serious eye damage), carcinogenic and teratogenic, dangerous for the environment.

As the coloring of the litmus paper shows, aniline has a weak basic character (it forms stable, water-soluble salts with acids). Aniline and water are partially miscible and form a heterogeneous azeotrope. At p = 778 mmHg, the azeotrope concentrations are: 3.64 mol% of aniline in vapor, 1.48 mol% of aniline in liquid aqueous phase, 62.8 mol% of aniline in liquid organic phase [

10].

The thermal analysis curve (cooling from 150 °C to 80 °C under 1013 hPa) of a water-aniline mixture with heteroazeotropic composition shows a horizontal plateau: the temperature does not vary, since there are no degrees of freedom.

2.2. Some Typical Reactions and Analytical Methods

Aniline exhibits the typical chemical behavior of aromatic amines. There are numerous chromatic reactions, also used for analytical purposes: with sodium hypochlorite you get violet color (Runge's essay) [

11], with acetic acid and furfural it turns red [

12], with potassium dichromate and sulfuric acid a characteristic blue-green shade is obtained [

13].

The residual water content in the prepared aniline is determined by titrating the water using the Karl Fischer (1901-1958) method [

14]. This method is based on the reduction of iodine by sulfur dioxide, a reduction that requires the presence of water. In practice, using an automatic burette, the Karl Fischer titrant (a reagent containing iodine and sulfur dioxide dissolved in methanol) is added to the sample whose mass composition in water is to be determined. Before the equivalence, there is still water in solution, so the iodine is completely consumed and the solution remains colorless. After the equivalence, the iodine is added in excess and no longer reacts. The solution takes on the color of the titrant solution.

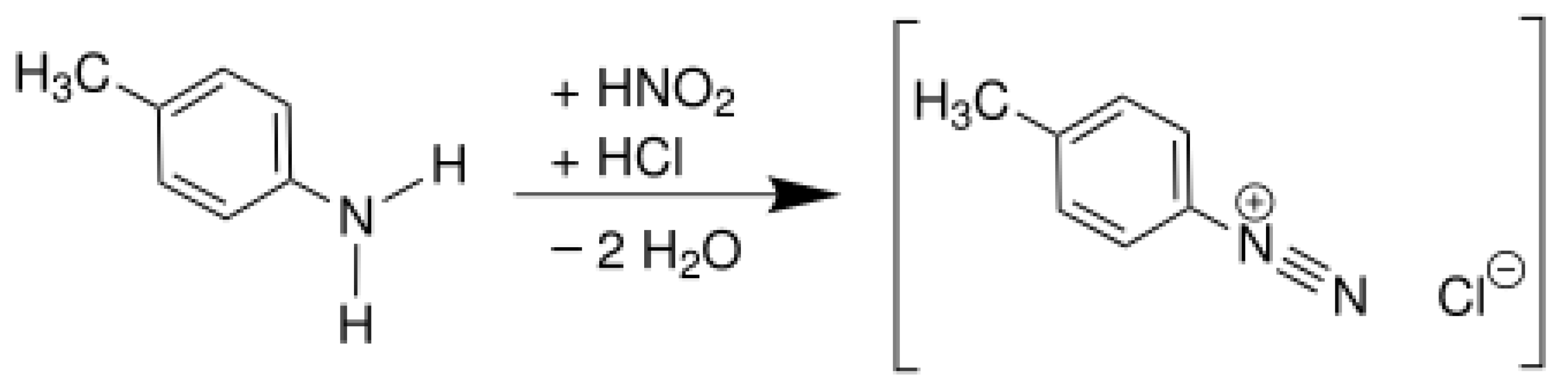

The diazotization reaction [

15] to obtain colored species is carried out by the action of nitrous acid on aniline. Nitrous acid is not a stable species in aqueous solution, it is prepared just before use by reacting cold hydrochloric acid or sulfuric acid with a sodium nitrite solution.

There is experimental evidence for the formation of charged species when iodomethane reacts with excess of aniline. If the aniline is not in excess, the reaction yield is very low and the presence of by-products is noted.

2.3. Methods of Preparation

Today aniline is prepared according to various industrial processes; the most important are the following:

- reduction of nitrobenzene with iron and aqueous hydrochloric acid, according the method of Pierre J. A. Béchamp (1816-1908) [

16] (in industrial practice, only 1/50 of the quantity of hydrochloric acid stoichiometrically required is used, since ferrous chloride - one of the products of the reaction - contributes to the reduction of nitrobenzene);

- reaction of nitrobenzene with concentrated hydrochloric acid and tin [

17];

- hydrogenation of nitrobenzene in the gas phase by passing it with hydrogen over copper-based catalysts at 200-350°C [

18];

- ammonolysis of phenol at 300-600°C on a vanadium oxide catalyst supported on alumina-silica [

18];

- ammonolysis of chlorobenzene under pressure at 200°C with concentrated ammonia solution in the presence of cuprous salts [

18];

- reaction at low temperatures (- 33°C) of bromobenzene with potassium amide [

19].

2.4. Some Historical Notes

Aniline was discovered in 1826 by the young pharmacist Otto Unverdorben (1806-1873) by dry distillation of indigo; it was isolated by distillation of coal tar in 1834 by Friedlieb F. Runge (1794-1867) [

20]; in 1840 Carl Julius Fritzsche (1808-1871) synthesized it by reacting indigo with potash (hence the coining of the name from anil, the Sanskrit term for the indigo plant); in 1841 Nikolaj Nikolaevič Zinin (1812-1880) obtained it by reduction of nitrobenzene [

21,

22]. However, until Perkin obtained mauveine from aniline by oxidation with dichromate in 1856, «this substance remained a mere laboratory curiosity, devoid of industrial application» [

23] (p. 171). The characteristic color of mauveine, the first synthetic dye, depends on the action of oxidizing agents on aqueous solutions of commercial aniline salts; this oxidation produces a mix of four compounds: A, B, B2, C. At the time, Perkin did not know the structure of these compounds, much less the reason for their color; when mauveine was first introduced to the market, its chemistry was still a mystery. Therefore, Perkin was able to advance the production of mauveine and other synthetic dyes without fully understanding their chemical structures and properties. The discovery of mauveine paved the way for the synthesis of many other synthetic dyes in a wide range of colors; it was even possible to predict the color of a compound before it was produced [

24]. The aniline used by Perkin in the first synthesis of mauveine was not pure, but consisted of a mixture of “anilines” (different aromatic amines) and toluidines. The composition of this mixture was not identified until 1994, with advanced analytical techniques [

24]. Perkin also synthesized a dye from pure aniline and called it “pseudo-mauveine”, but its color was neither as bright nor as attractive as that of the original mauveine [

24].

The case of obtaining mauveine falls into the category of serendipity. Perkin had set himself the goal of artificially producing quinine, an antimalarial drug whose high costs were due to the extraction process from the plant. Hofmann suggested Perkin try to synthesize it starting from substances contained in fossil coal. Perkin began to try to synthesize quinine from substances contained in coal, but he obtained only a bluish slurry and not a crystalline product. Instead of throwing it away, Perkin tried to perform an extraction with methanol, obtaining a red-violet solution that persisted on tissues: Perkin had obtained a synthetic dye [

25].

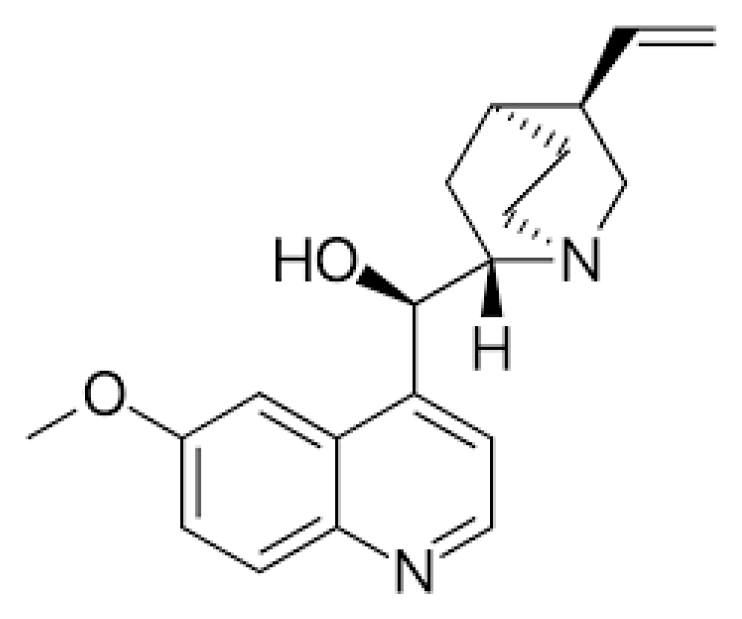

3. Symbolic Level

3.1. Formula, Basic Character, Diagrams

Aniline (molecular formula C

6H

7N, structural formula in

Figure 4), is widely used because it has a very rich reactivity, due to the simultaneous presence of a benzene cycle and an amine function.

Figure 5 shows the formula of quinine, the compound desired by Perkin: it is clear that Perkin could never have synthesized it with the means available at the time.

As reported in the § 2.1, aniline has a basic character:

Ph-NH2(aq) + H2O(l) ⇄ Ph-NH3+(aq) + HO-(aq)

Due to its lower basicity compared to ammonia, an aniline solution has a lower pH than an ammonia solution with the same concentration.

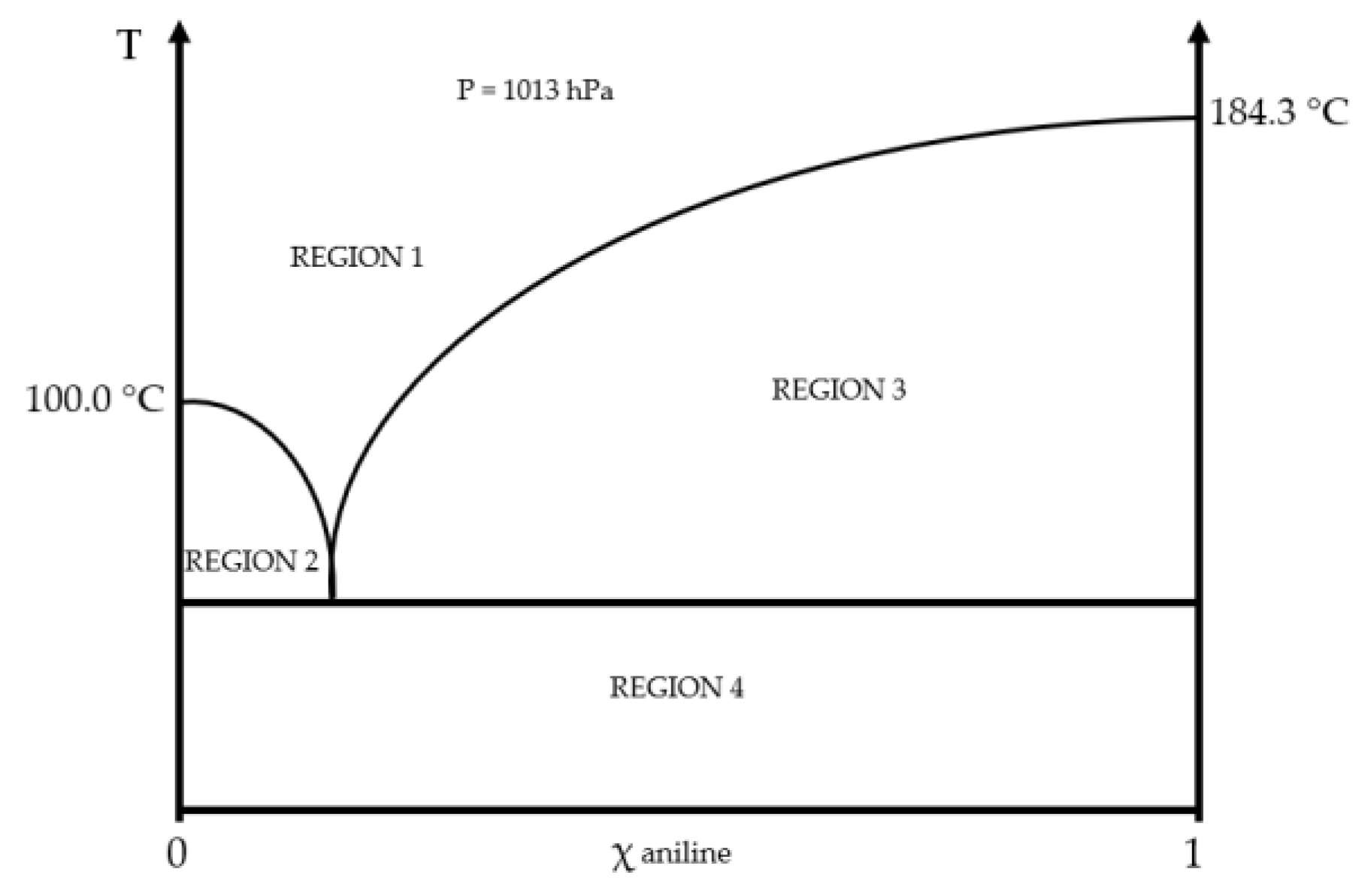

Assuming that water and aniline are totally immiscible in the liquid state,

Figure 6 represents the shape of the binary liquid/vapor water-aniline diagram, where:

T = f(xaniline) at P = 1013 hPa.

It is possible to identify four regions in the diagram: region 1 indicates a vapor phase with water and aniline; region 2 indicates a vapor phase with water and aniline, and a liquid phase that contains only water; region 3 indicates a vapor phase with water and aniline, and a liquid phase that contains only aniline; zone 4 indicates two liquid phases, one containing only water and the other containing only aniline.

If the partial miscibility of water and aniline, even if minimal, is considered, it is known that the two substances form a heterogeneous azeotrope. At ambient pressure, the azeotrope concentrations are: 3.64 mol% of aniline (in vapor phase), 1.48 mol % of aniline (in liquid aqueous phase), 62.8 mol% of aniline (in liquid organic phase). The thermal analysis curve (cooling from 150 °C to 80 °C under 1013 hPa) of a water-aniline mixture with heteroazeotropic composition shows a horizontal plateau. This plateau can be justified by calculating the number of degrees of freedom. The system composed of liquid water, water vapor, liquid aniline, aniline vapor is considered. There are 5 intensive parameters (Z):

P, T, X(l H2O), X(v H2O), X(l aniline), X(v aniline)

and 5 relationships between them (Y):

X(v H2O) + X(v aniline) = 1; X(l H2O) = 1; X(l aniline) = 1

H2O(l) → H2O(g) K°(T) = Qr,eq = X(v H2O) · P/ (X(l H2O) · P°)

Ph-NH2(l) → Ph-NH2(g) K°(T) = Qr,eq = X(v aniline) · P/ (X(l aniline) · P°)

The variance v is:

v = Z – Y = 1

Since the pressure is fixed at the value P = 1013 hPa, v = 0.

Therefore, there are no degrees of freedom: the temperature cannot vary, hence the observed plateau.

3.2. Reactions

The following reactions are involved in Karl Fischer method described in § 2.2, commonly used for the determination of water content in organic solvents such as aniline. The procedure is based on the oxidation of sulfur dioxide by iodine observed by Robert Bunsen (1811-1899) [

26]:

I2 + SO2 + 2 H2O → 2 HI + H2SO4

The titration is carried out in an anhydrous solvent (such as methanol) in the presence of a base that neutralizes the sulfuric acid produced by the reaction and giving rise to a buffer solution stabilizing the pH values between 5 and 7.

RN represents a generic basic molecule, for example aniline:

CH3OH + SO2 + RN → [RNH]SO3CH3

[RNH]SO3CH3 + I2 + H2O + 2 RN → [RNH]SO4CH3 + 2 [RNH]I

When the iodine has reacted with all the water, its color is no longer visible. The reaction, rapid and highly selective (only water reacts), is used in a titration procedure whose endpoint is generally detected by voltammetric or amperometric means.

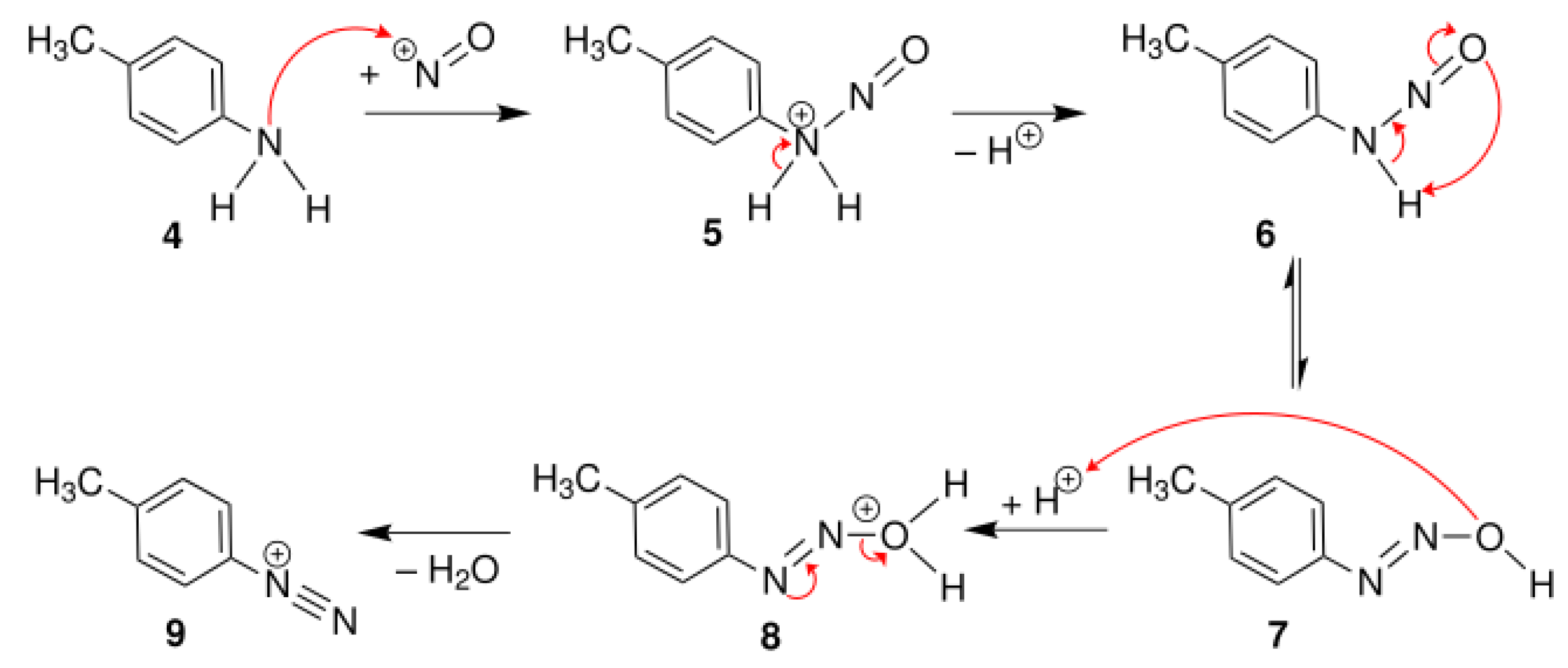

In 1858, Johann P. Grieß (1829-1888) was the first to succeed in the diazotisation reaction, which produces the characteristic azo group (-N=N-) that gives the name to this dye class. Grieß discovered that the synthetic reaction between phenol and diazonium salt (obtained by the diazotization reaction reported in

Figure 7) produced a colored molecule, the first azo dye.

Aromatic diazonium salts are stable and are used as intermediates for the synthesis of numerous aromatic compounds. They are synthesized by the reaction of primary aromatic amines (such as p-methylaniline) with nitrous acid (

Figure 7).

Since nitrous acid is not stable in aqueous solution, it is prepared just before use by reacting cold hydrochloric acid or sulfuric acid with a sodium nitrite solution. This can be explained reasoning about the electronic structure of nitrous acid and using thermodynamic constants. The dismutation reaction of nitrous acid is reported as the sum of two half-reactions, with their respective free energy values:

- (1)

HNO2 + H+ + e- → NO + H2O ΔrG°1 = - F∙E°1

- (2)

-

NO3- + 3 H+ + 2 e- → HNO2 + H2O ΔrG°2 = - 2F∙E°2

Linear combination 2(1) – (2):

- (3)

3 HNO2(aq) → H+(aq) + NO3-(aq) + 2 NO(g) + H2O(l) ΔrG°3 = - R∙T∙lnK°

The linear combination used to determine the equilibrium thermodynamic constant associated with disproportionation is:

(3) = 2(1) – (2) → ΔrG°3 = 2 ΔrG°1 - ΔrG°2

→ - R∙T∙lnK° = - 2F∙E°1 + 2F∙E°2 → R∙T∙lnK° = 2F∙ (E°1 - E°2)

logK° = 2(E°1 - E°2)/0.06 = 2 ∙ (0.98 – 0.94)/0.06 = 1,33 → K° = 21

The reaction is slightly in favor of the products, so nitrous acid is not stable. For this reason, it is best to prepare it just before use. The mechanism of diazotization reaction is reported in § 4.1.

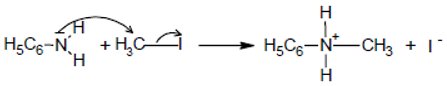

When placed in the presence of a haloalkane, amines can undergo alkylation reactions. In § 2.2, reference is made to the reaction of iodomethane with excess of aniline [

27]; monomethylated aniline and anilinium iodide are formed:

2 C6H5 -NH2 + CH3I → C6H5 -NH(CH3) + C6H5 -NH3+ I –

The mechanism of this reaction explains the dependence of its rate on the amount of aniline introduced; il will be shown in the next section (§ 4.2) dedicated to the submicroscopic level.

3.3. Synthesis

Béchamp reaction [

16] (§ 2.3) is:

Nitrobenzene was obtained by reacting benzene and nitric acid. Since nitric acid was too expensive, Perkin used a mixture of Chilean nitrate (NaNO3) and sulfuric acid, from which he obtained nitric acid. In addition, sulfuric acid also served as a catalyst for the reaction, in addition to serving as a reagent in the subsequent reaction to obtain aniline.

To reduce nitrobenzene, also concentrated hydrochloric acid and tin can be used to form the phenyl ammonium ion [

17]. The entire reaction can be derived from the two half-reactions:

C6H5-NO2 + 7 H+ + Cl- + 6 e- → C6H5-NH3+Cl- + 2 H2O

[SnCl6]2- + 4 e- → Sn + 6 Cl-

Hence the reaction equation modeling the reduction of nitrobenzene by tin:

2 C6H5-NO2(aq) + 14 H+(aq) + 20 Cl-(aq) + 3 Sn(s)→ 2 C6H5-NH3+Cl-(aq) + 3 [SnCl6]2-(aq) + 4 H2O(l)

The reaction of hydrogenation of nitrobenzene in the gas phase [

18] (by passing it with hydrogen over copper-based catalysts at 200-350°C) is:

C6H5-NO2 + 3 H2 → C6H5-NH2 + 2 H2O

Aniline can be prepared by direct amination of phenol with ammonia in vapor phase [

18], in presence of a solid, heterogenous catalyst (on a vanadium oxide catalyst supported on alumina-silica):

C6H5OH + NH3 → C6H5NH2 + H2O

A similar reaction (under different conditions) involves chlorobenzene [

18]. The reaction at low temperatures (- 33°C) of bromobenzene with potassium amide in liquid ammonia [

19] is:

C6H5Br + KNH2 → C6H5NH2 + KBr

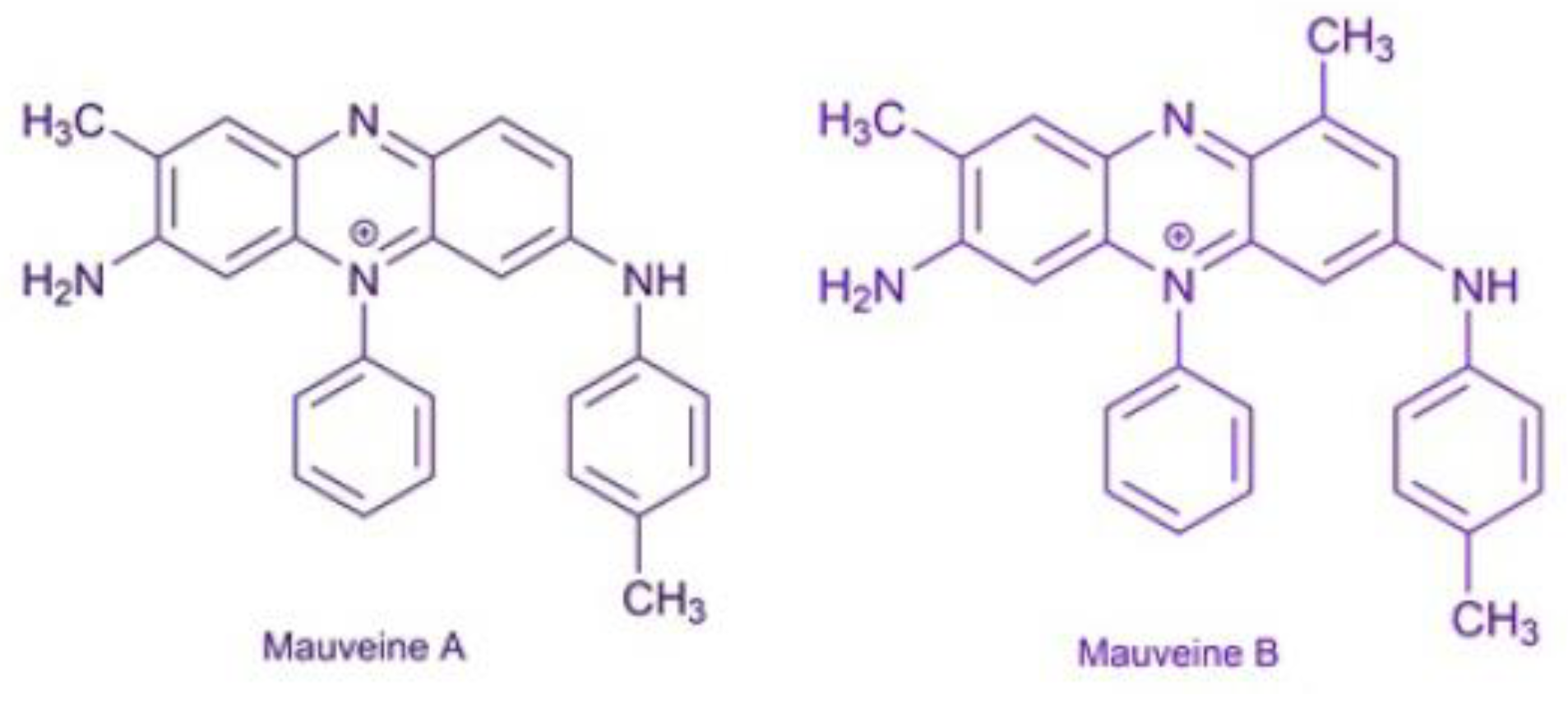

3.4. The Mauveine

Mauveine has been studied and analyzed since the 1960s for its historical interest, however the definitive structures of its chromophores were determined for the first time with NMR only in 1994. The study led to the determination of the mixture of two main chromophores present in the commercial dye, called mauveine A and mauveine B [

24], shown in

Figure 8.

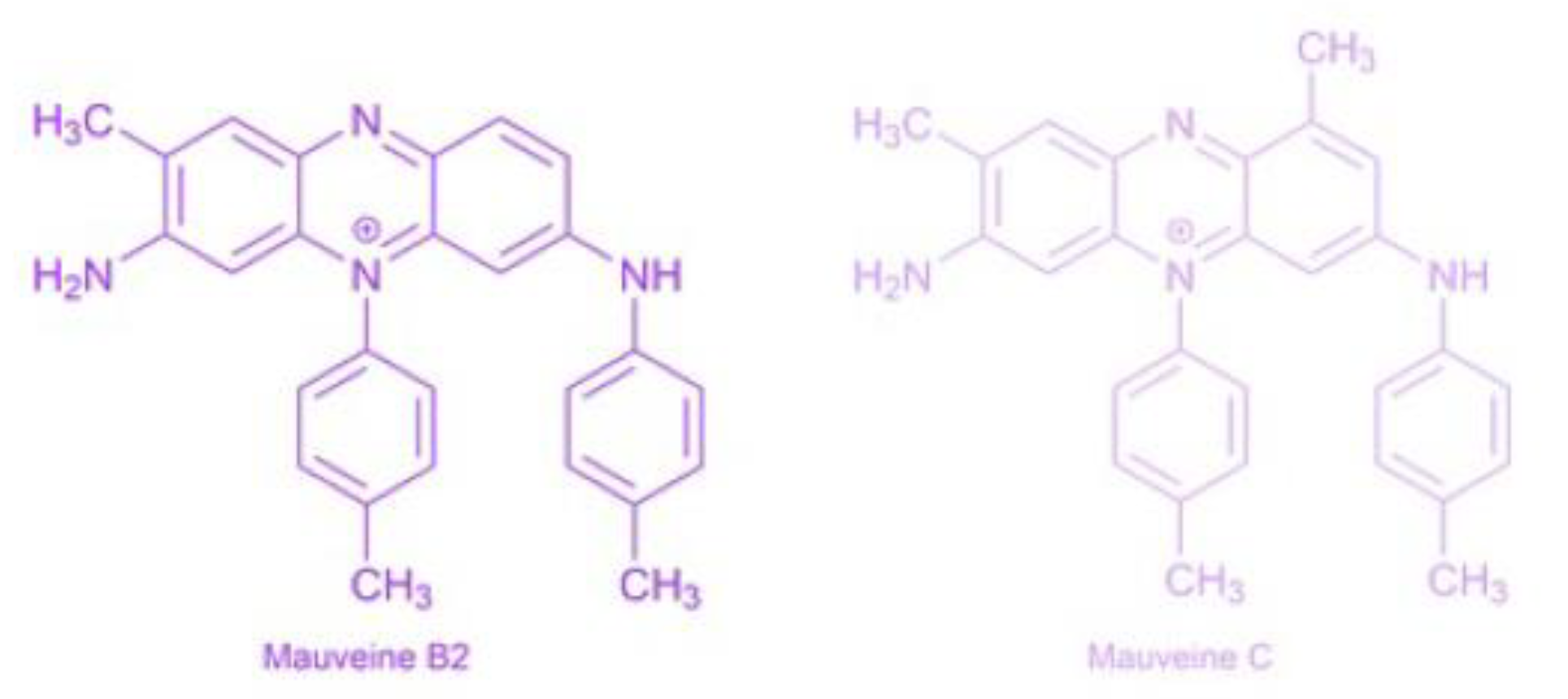

More recent studies conducted in 2007 revealed the presence of four main chromophores: in addition to the already known mauveines A and B, also mauveines B2 and C (

Figure 9), in a mixture of at least thirteen methyl derivatives, from C

24 to C

28 [

24].

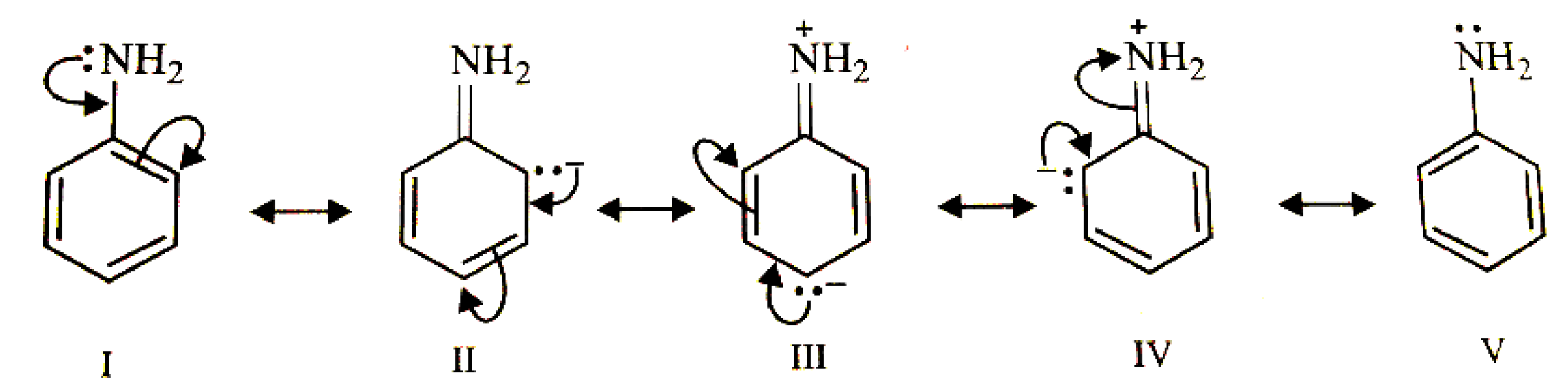

4. Sub-Microscopic Level

Aniline is a Lewis base, but it is less basic than primary amines because the electron pair on nitrogen is partially shared with the aromatic ring by resonance, and is therefore less available to be a proton acceptor behaving as a Brønsted-Lowry base:

Figure 10.

Some resonance structures of aniline.

Figure 10.

Some resonance structures of aniline.

4.1. Diazotization Reaction

The identification of the structure of the aniline was fundamental to understanding the mechanics of its reactions, for example alkylation or diazotization.

Figure 7 shows the diazotization reaction mechanism. This reaction occurs through the action of nitrous acid on methylated aniline. As for the mechanism of the nitration reaction, it is well known: first the formation of the nitrosyl cation occurs (

Figure 11); subsequently, the lone pair of the nitrogen atom on the arylamine attacks the positively charged nitrogen atom of the nitrosyl cation. This results in deprotonation and rearrangement leading to the formation of a diazohydroxide. The latter is protonated on the oxygen atom and, with the elimination of a water molecule, an aryldiazonium cation is formed (

Figure 12).

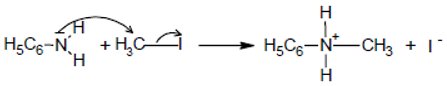

4.2. Preparation of Ammonium Salts

Let us now consider the mechanism of the following reaction:

2 C6H5 -NH2 + CH3I → C6H5 -NH(CH3) + C6H5 -NH3+ I –

The first reaction is the SN2 type; it leads to the formation of a secondary ammonium salt:

C6H5-NH2 + CH3I → C6H5-NH2(CH3)+ I-

The mechanism is:

The secondary ammonium salt is deprotonated by a base present in the environment. As aniline is introduced in excess, this molecule plays the basic role:

C6H5-NH2 + C6H5-NH2(CH3)+ I- → C6H5-NH(CH3) + C6H5-NH3+ I-

If aniline is not present in excess, secondary, tertiary, quaternary ammonium salts, and a tertiary amine, are formed.

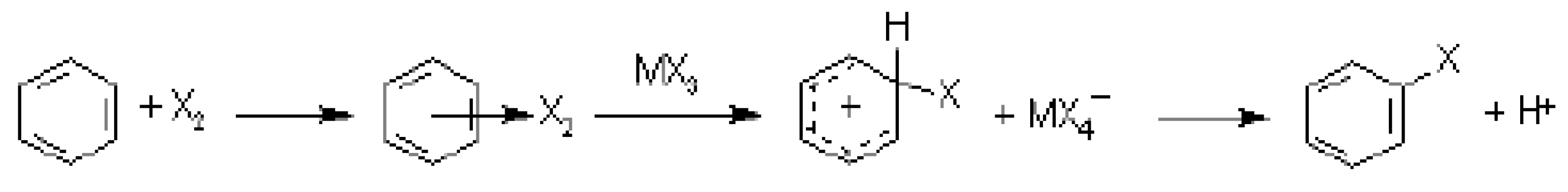

4.3. Electrophilic Aromatic Substitutions

Finally, some considerations on the synthesis of aniline. One of the most used methods is the nitration of benzene (originally obtained from coal) and the subsequent reduction of the nitrobenzene obtained. The nitration of benzene is an electrophilic aromatic substitution reaction, according to the following mechanism:

Figure 13.

The mechanism of the electrophilic aromatic substitution reaction.

Figure 13.

The mechanism of the electrophilic aromatic substitution reaction.

As can be observed, the electrophile is bound to a nucleophile (Y), from which it detaches (alone or with the help of a catalyst) forming the species Y-. The reaction proceeds with a two-stage mechanism: in the first the aromatic ring attacks the electrophile E

+ losing its aromaticity (slow stage); in the second the intermediate loses the hydrogen ion H

+ regaining its aromaticity. The species Y behaves as a base acquiring the H+ ion and forming the species YH. The reaction is made possible by the stability of the carbocation intermediate, of which three resonance forms are reported. In the case of nitration, the electrophile is the NO

2+ ion, which in turn derives from nitric acid HNO

3. In old textbooks, other hypotheses of mechanism appear, now abandoned [

28]. The formation of the carbocation intermediate (called σ-complex) is now accredited. However, it has been shown experimentally that, before forming the σ -complex, some electrophiles form a π-complex with the aromatic system (

Figure 14). The formation of this complex can sometimes modify the kinetics of the reaction, because this step (and not the formation of the σ-complex) can become the slow step of the reaction [

28].

The effect of substituents on electrophilic aromatic substitution has also been one of the most controversial topics from an interpretative point of view. It is known that some substituents activate the aromatic nucleus towards this type of reaction and orient the reaction in the ortho and para positions (such as the -NH

2 group). Others deactivate the ring and orient it in meta (such as the -NO

2 group). Still others deactivate the ring but orient the reaction in ortho and para (such as the halogens). A past theory was based on the study of the effect of the substituent on the electron density of the substrate (alternating polarity theory) [

28]. This theory presented some contradictions, therefore it was abandoned in favor of the one accepted today: the electron-donating or electron-attracting substituents stabilize or destabilize the carbocation intermediate in different ways, so that both the kinetics and the position of the second substituent are influenced.

However, also this approach is not free from problems: for example, it does not allow to distinguish the reactivity of some heterocyclic compounds [

28]. One of the problematic aspects of the most widely used theory today to explain electrophilic aromatic substitutions is the neglect of the characteristics of the electrophile (often the graphs do not specify at all which electrophile is used and, in any case, no role of the entering group is hypothesized in the stabilization of the σ-complex). In rather recent times a theoretical hypothesis has been formulated which refers to the Klopman-Salem equation [

28]: it explains how the interaction between the two reagents can be influenced by electrostatic interactions, or by the interaction between the HOMO and LUMO orbitals of the reagents. Since mauveines are heterocycles, maybe their reactivity could also be further clarified through this theory, which is not antithetical to the commonly accepted one, but allows to describe the reaction mechanisms at higher levels of complexity.

5. Applied Chemistry

Following the discovery of mauveine in 1856, the Badische Anilin & Sodafabrik, which later became BASF, was founded in Germany in 1865. Aniline was then widely used on an industrial scale for the production of dyes such as fuchsin. These dyes were quickly supplanted by a new type of molecule: azo dyes, initially obtained from aniline through diazotization reactions, represent a wide range of organic compounds of great importance in fields such as the textile industry [

29]. Today, aniline remains a key organic compound. The majority of the tonnage produced is used in polymer chemistry, particularly for the preparation of the diisocyanate monomer used in the synthesis of polyurethane. Black aniline-based dyes are still used for dyeing leather, in printing inks, and for marking linens. Aniline continues to be used in the rubber vulcanization process, as well as in the pharmaceutical field for the development of bactericidal agents such as sulfanilamide derivatives. In recent years, aniline has experienced a revival in the field of innovative materials. Indeed, by polymerizing aniline, the polyaniline is obtained, a conductive polymer which can be used for a wide range of applications such as a conductive coating for fabrication of smart and flexible textiles [

30,

31].

The impact of dyes on fashion has been disruptive. From the second half of the nineteenth century, the fashion industry developed rapidly especially in France, consolidating the position of chemistry as a science of social change [

32]. According to Charles C. Gillispie (1918-2015) [

33], the connection between scientists and industries in France was shaped by the country's centralized cultural development, particularly in Paris. This centralization gave the French government significant influence over the Académie des sciences, which was tasked with both advancing scientific knowledge and providing expert evaluations for industrial projects. However, Gillispie concluded that the transformation of the French textile industry resulted primarily from the arrival of skilled English and Scottish craftspeople, rather than from direct scientific influence [

33].

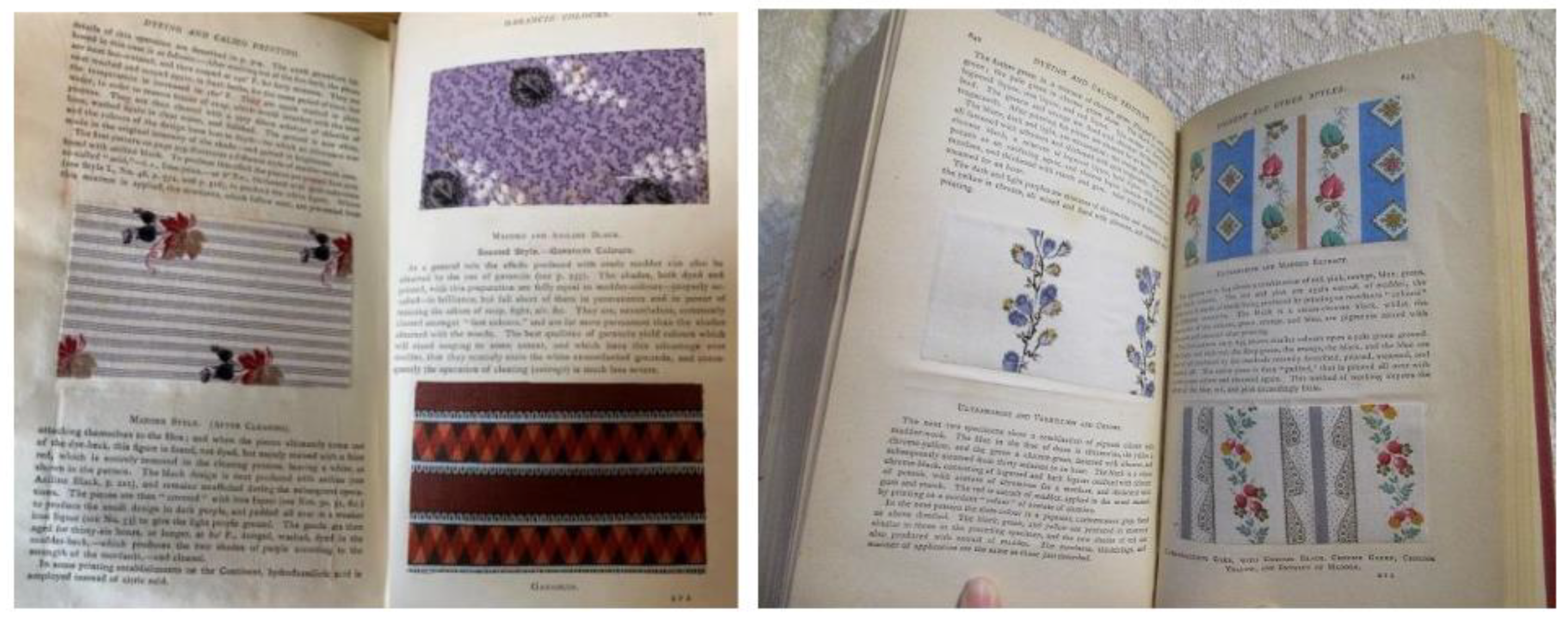

An eloquent example of the great development of the English dye industry and the related artisanal techniques is given by William Crookes's manual "A practical handbook of dyeing and calico-printing" [

23,

34], where the author lists methods of extraction, synthesis and processing of natural and synthetic dyes, with particular attention to aniline derivatives (

Figure 15).

Of little scientific value, the manual has an eminently practical purpose. The monetization of science typical of the spirit of Crookes is evident from the preface: the author declares himself aware of the difficulty of doing justice to such a vast and constantly evolving subject; however, he sincerely trusts that, despite the inevitable defects, the compendium can indicate to students profitable fields of research useful for their future profession, as well as contributing to the development of British industry [

23] (p. VI).

Crookes' great attention to trade is also evident in his enthusiasm for the synthesis of alizarin, «an important national discovery, the money value of which may be reckoned by millions» [

35]; in reality, the synthesis of the dye was carried out by the Germans Carl Gräbe (1841-1927) and Carl Theodore Liebermann (1842-1914). If alizarin had been synthesized in Great Britain, Crookes would have benefited greatly, given his position as director of the «Alizarine and Anthracene Company», a company involved in the supply of raw materials for the growing British dye industry. Unfortunately for the English industrialists, not the synthesis, but only the chemistry of alizarin (and madder root colors) had been developed in Manchester by Henry Edward Schunck (1820-1903). The great development of German organic chemistry made competition with Great Britain inevitable also in the field of dyes. For example, it was the German chemist Grieß who pioneered the synthesis of azo dyes. The first azo dyes include Aniline Yellow (1862), Bismarck Brown (1863), and Chrysoidine (1875). The series of orange azo dyes and Scarlet Reds were developed during the period 1875–1878. At the end of the 19th century, about 70% of the dyes belonged to the azo dye class [

36].

6. Socio-Cultural Context

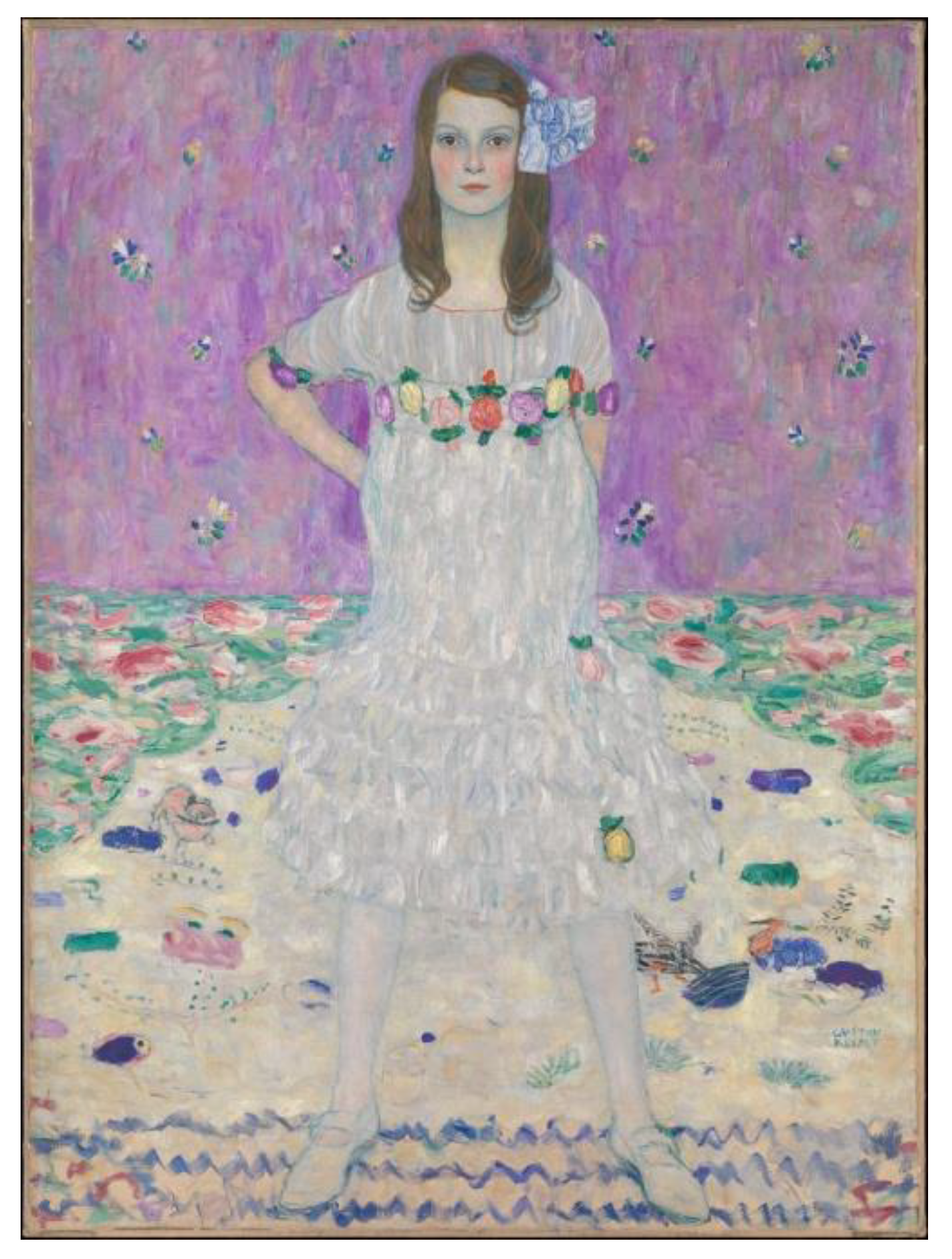

The dye industry has certainly contributed to creating induced needs: today we all consider the use of artificially colored clothes as normal. However, the influence of artificial dyes has extended far beyond customs, influencing workplace safety, medicine, political movements, and art for long time [

37] (

Figure 16).

An eloquent example is given by the term "Mauve Decade", primarily refers to the 1890s, particularly in American culture. It's a period that's been captured and defined in popular consciousness, most notably by Thomas Beer's book, "The Mauve Decade: American Life at the End of the Nineteenth Century” [

38]. The term clearly refers to mauveine, which led to a surge in the color's popularity in fashion and interior design during the 1890s. The Art Nouveau movement was also gaining popularity during this time, and the flowing lines and organic forms of Art Nouveau were often displayed in the popular mauve color [

39] (p. 101). Beer's book portrays the 1890s as a time of contradictions, with both opulence and underlying social tensions: the Mauve Decade was a time of significant social and cultural change, a period marked by rapid industrialization, wealth, and social inequality, not only in America.

Some novels [

40] and the first systematic studies of occupational medicine [

41] have amply documented the distortions that the new organization of factories was generating, such as child exploitation. It is enough to observe, in Crookes's manual on dyes [

23] (p. 192)

1, the representations of some production phases presumably inside private homes (an example in

Figure 17). It is evident, observing the subjects depicted, that the housework carried out by women and children was not considered illegal nor immoral, but rather constituted a privilege compared to work in mines and factories. The harmful effects of many synthetic dyes were not known, and the regulations for the protection of workers were still in an embryonic stage to say the least [

41]. For example, it is widely demonstrated that the production of fuchsin, a magenta dye obtained from aniline, causes the development of bladder tumors among production workers.

While the link between cancer risk and the production of certain synthetic dyes has been elucidated over a very long period of time, occupational safety concerns were already evident at the time of the first aniline plants started up under Perkin's direction. The reactions used were exothermic, therefore they involved a continuous increase in temperature of the reaction environment. Therefore, it was necessary to continuously cool the containers so that the temperature did not exceed 50-60°C. Once this threshold was exceeded, the nitration proceeded more than it should, with the consequent formation of by-products and a decrease in the reaction yield; one of these unwanted secondary products was particularly dangerous: trinitrotoluene, an explosive that could be originated by the nitration of toluene [

25] (p. 59). Furthermore, nitrous fumes polluted the air, but at that time ecological awareness was non-existent and the extent of the damage was limited, except for the workers who were forced to stay near the plants for many hours with the risk of explosions and fires. Not only the production, but also the trade of products containing mauveine was repeatedly hampered by safety issues. The use of these products in fact posed numerous public health problems [

25] (pp. 101-116).

Synthetic colors expanded the range of shades to be used in symbols for propaganda purposes or for social claims. It is no coincidence that the workers' movement and trade union organizations, already born in Europe during the Industrial Revolution of the late 18th and early 19th centuries, in some countries such as Italy began to gain ground towards the end of the nineteenth century, using means of diffusion such as posters, flyers or postcards whose cheap coloring became possible thanks to the mass production of printing dyes [

42]. An example is constituted by the posters and gadgets of the feminist movement "Dignity, Purity, Hope" led by Emmeline Pankhurst (1858-1928), colored in purple, green and white [

43].

7. Critical-Philosophical Approach

Gillispie claimed that the connection between science and industry was far more intricate than a simple exchange between artisans and scientists. He proposed that the application of science to industry should be understood as a sophisticated intellectual development, deeply rooted in the broader historical context of the Enlightenment, rather than merely a direct replacement of traditional methods with scientific theories [

33]. The invention of synthetic dyes was certainly a turning point in the history of science and society, paving the way for a myriad of discoveries. It stimulated research in areas such as pharmacology, leading to the synthesis of life-saving drugs, and contributed to the development of new materials and technologies. It made colors more accessible, transforming the textile industry and art. However, many synthetic dyes have been found to be toxic, causing health problems such as allergies, skin irritation, and in some cases, more serious illnesses. Exposure to certain chemicals used in the production of dyes has been linked to an increased risk of cancer. The production and disposal of synthetic dyes has contributed to water and soil pollution. Some persistent chemicals accumulate in the environment, causing long-term damage to ecosystems.

The image of chemistry as a two-faced Janus, with one face offering progress and the other revealing dangers [

44], is a powerful and appropriate metaphor, even in the case of artificial dyes. It is essential to find a balance between technological progress and the protection of human health and the environment, as is already happening in textile industry [

29], through green and sustainable chemistry [

45].

Scientists, engineers, and policymakers must acknowledge that technology is not unilaterally positive. It possesses a 'dialectical' quality, meaning it can both improve and degrade human life. The myth of Hubris and Nemesis illustrates this: hubris, or overconfidence, leads to actions defying established norms, and Nemesis is the resulting punishment. Applying this to synthetic dyes, ignoring potential negative impacts (Hubris) invites undesirable consequences (Nemesis) [

46].

The case of artificial dyes is emblematic of the social implications of the distinction between natural and synthetic. The distinction between natural and synthetic chemicals is often considered meaningless among chemists, but is widely used among the general public. Consumers tend to associate the term "natural" with positive health and environmental effects, while "synthetic" is often seen as more risky or harmful. This perception can influence purchasing decisions and preferences for products labeled as natural. Improper use of the distinction can lead to stigmatizing synthetic products, even when they are safe and effective.

To evaluate whether a substance is "natural" one must consider several factors: material origin, context of production, purpose, material distribution, impact, ethical and aesthetic issues, and non-metaphysical arbitrariness (in the debate over natural kinds, "natural" is contrasted with "arbitrary," indicating that a distinction follows the structure of the natural world)[

47]. Furthermore, the adjective "natural" can only be applied to samples of a substance, not to the substance as a whole. Naturalness is best understood as a statement about material origin [

47]. In this sense, even so-called "natural" dyes, such as compounds that impart an indigo or purple color, can be considered artificial if obtained otherwise than by extracting plants or mollusks, or according other criteria [

47]. Reflection on the natural-artificial dichotomy in light of the categories highlighted by recent philosophical reflection, could greatly improve the attitude towards chemicals, helping to consider multiple facets and developing critical thinking.

8. Conclusions

In this study, the case of aniline was examined using Sjöström's six-level framework. The educational path presented is designed to be adaptable across different educational settings, including secondary schools, Bachelor’s level organic chemistry, and courses in the history, philosophy, and ethics of chemistry. It offers a foundational structure that can be expanded or condensed as needed. The discovery of aniline and other synthetic dyes provides a compelling example of why a Bildung-focused chemistry education is essential, given its far-reaching impact on society, the economy, health, and art. Indeed, the influence of artificial dyes has been transformative, shaping everything from consumer habits to workplace safety, medicine, political movements, and artistic expression. A Bildung-oriented approach is therefore vital for developing informed and critical citizens.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Note

| 1 |

The tables referred to are found on an unnumbered page, between p. 292 and p. 293. |

References

- Scerri, E.R.; McIntyre, L. The Case for the Philosophy of Chemistry. Synthese 1997, 111, 213–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnstone, A.H. Thinking about Thinking. International Newsletter of Chemical Education 1991, 36, 7–10. [Google Scholar]

- Mahaffy, P. The Future Shape of Chemistry Education. Chem. Educ. Res. Pract 2004, 5, 229–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sjöström, J. Towards Bildung-Oriented Chemistry Education. Sci. Educ. 2013, 22, 1873–1890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagan, E.; Poulin, J. Statistics of the Early Synthetic Dye Industry. Herit. Sci. 2021, 9, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sjöström, J. The Discourse of Chemistry (and Beyond). HYLE 2007, 2, 83–97., J. The Discourse of Chemistry (and Beyond). Hyle 2007, 2, 83–97. [Google Scholar]

- Sjöström, J.; Eilks, I. Correction to: The Bildung Theory—From von Humboldt to Klafki and Beyond. In Science Education in Theory and Practice: An Introductory Guide to Learning Theory; Akpan, B., Kennedy, T.J., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2020; pp. C1–C1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schummer, J. Why Chemists Need Philosophy, History, and Ethics. Substantia 2, 5–6. [CrossRef]

- National Center for Biotechnology Information. PubChem Compound Summary for CID 6115, Aniline, 2025. Available online: https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/compound/Aniline (accessed on 13 March 2025).

- Griswold, J.; Andres, D.; Arnett, E.F.; Garland, F.M. Liquid–Vapor Equilibrium of Aniline–Water. Ind. Eng. Chem. 1940, 32, 878–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, N. The Oxidation of Aromatic Amines by Sodium Hypochlorite, University of Surrey, Guildford, 1970.

- Friedemann, T.E.; Keegan, P.K.; Witt, N.F. Determination of Furan Aldehydes. Reaction with Aniline in Acetic and Hydrochloric Acid Solutions. Anal. Biochem. 1964, 8, 300–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

-

Dichromate Test for Aniline | Acidified Potassium Dichromate Reaction With Aniline; BMH Learning. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=X181RA8G4sM (accessed on 13 March 2025).

- Meyer, A.S.; Boyd, C.M. Determination of Water by Titration with Coulometrically Generated Karl Fischer Reagent. Anal. Chem. 1959, 31, 215–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yates, E.; Yates, A. Johann Peter Griess FRS (1829–88): Victorian Brewer and Synthetic Dye Chemist. Notes Rec. 2016, 70, 65–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wisniak, J. Pierre Jacques Antoine Béchamp. Contributions to Chemistry. Rev. CENIC Cienc. Quím. 2020, 51, 114–125. [Google Scholar]

- Clark, J. Preparation of Phenylamine Compounds. Available online: https://chem.libretexts.org/@go/page/3993?pdf (accessed on 14 March 2025).

- Anilina. Chimica; Le garzantine; Garzanti: Milano, 2002; p. 77. [Google Scholar]

- Farmer, S.; Kennepohl, D.; Kabrhel, J.; Roberts, J.; Caserio, M.C. Benzyne. Available online: https://chem.libretexts.org/@go/page/31580?pdf (accessed on 14 March 2025).

- Maar, J.H. Friedlieb Ferdinand Runge (1794-1867) – An Unusual Chemist. Substantia 2025, 9, 73–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Califano, S. Storia Della Chimica. Vol. II. Dalla Chimica Fisica Alle Molecole Della Vita, Digital edition.; Bollati Boringhieri: Torino.

- Plater, M.J.; Raab, A. Who Made Mauveine First: Runge, Fritsche, Beissenhirtz or Perkin? Journal of Chemical Research 2016, 40, 758–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crookes, W. A Practical Handbook of Dyeing and Calico-Printing; Longmans, Green and Co.: London (UK), 1874. [Google Scholar]

- Iuliano, A. The dye that revolutionised chemistry: Perkin and the discovery of mauveine. Research for Cultural Heritage. Available online: https://researcheritage-eng.blogspot.com/2019/07/Perkin-and-the-discovery-of-mauveine.html (accessed on 14 March 2025).

- Garfield, S. Il Malva Di Perkin. Storia Del Colore Che Ha Cambiato Il Mondo; Garzanti: Milano, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Sella, A. Karl Fischer’s Titrator. Chemistry World. December 3, 2012. Available online: https://www.chemistryworld.com/opinion/karl-fischers-titrator/5695.article (accessed on 14 March 2025).

-

Excess Aniline Undergoes Alkylation with Methyl Iodide to Yield Which of the Following?; doubtbut by Allen. Available online: https://www.doubtnut.com/qna/256666655 (accessed on 13 March 2025).

- D’Auria, M. L’evoluzione Del Pensiero Nello Studio Delle Reazioni Di Sostituzione Elettrofila Aromatica. Thought Evolution in the Study of Electrophilic Aromatic Substitution Reactions Proposed Different. Chim. Sc. 2002, No. 2, 53–56. [Google Scholar]

- Emanuele, L.; D’Auria, M. The Use of Heterocyclic Azo Dyes on Different Textile Materials: A Review. Organics 2024, 5, 277–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chauhan, N.P.S.; Mozafari, M. Chapter 1 - Polyaniline: An Introduction and Overview. In Fundamentals and Emerging Applications of Polyaniline; Mozafari, M., Chauhan, N.P.S., Eds.; Elsevier, 2019; pp 1–15. [CrossRef]

- Abu-Thabit, N.Y. Chemical Oxidative Polymerization of Polyaniline: A Practical Approach for Preparation of Smart Conductive Textiles. J. Chem. Educ. 2016, 93, 1606–1611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinsen, H.E.H. Fashionable Chemistry: The History of Printing Cotton in France in the Second Half of the Eighteenth and First Decades of the Nineteenth Century, University of Toronto, Toronto (CA), 2015.

- Gillispie, C.C. The Natural History of Industry. Isis 1957, 48, 398–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Celestino, T. A Practical Handbook of Dyeing and Calico-Printing: Il Secolo Del Colore Si Mostra al Mondo. Rend Accad Naz XL 2024, V (1), 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Crookes, W. A Recent Triumph of Synthetical Chemistry. Quartely Journal of Science, 1869; 360–362. [Google Scholar]

- Tamburini, D.; Sabatini, F.; Berbers, S.; van Bommel, M.R.; Degano, I. An Introduction and Recent Advances in the Analytical Study of Early Synthetic Dyes and Organic Pigments in Cultural Heritage. Heritage 2024, 7, 1969–2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romagnoli, A. William Perkin e Il Colora Malva: La Prima Tinta Sintetica. Available online: https://www.missdarcy.it/william-perkin-e-il-color-malva-la-prima-tinta-sintetica/ (accessed on 14 March 2025).

- Beer, T. The Mauve Decade: American Life at the End of the Nineteenth Century; Alfred A. Knopf: New York, 1926. [Google Scholar]

- Daniel, G. Decorative Arts. In Art nouveau: art and design at the turn of the century; Selz, P., Constantine, M., Eds.; The Museum of Modern Art: New York, 1959; pp. 86–121. [Google Scholar]

- Dickens, C.J.H. Oliver Twist; Richard Bentley, 1838.

- Di Martiis, M.S. Lavoro e Salute in Europa Prima Della Rivoluzione Industriale. RIMP 2010, No. 1, 119–162. [Google Scholar]

- Franchini, E. Manifesti e Fogli Volanti Del Movimento Operaio Del Primo Novecento, 2013. Available online: https://filstoria.hypotheses.org/9924 (accessed on 14 March 2025).

- Polanská, K. The Legacy of Emmeline Pankhurst in the British Society, Univerzita Palackého v Olomouci, Olomouc, 2016.

- Hoffmann, R. The Same and Not the Same; Columbia University Press: New York, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Celestino, T. High School Sustainable and Green Chemistry: Historical–Epistemological and Pedagogical Considerations. Sustainable Chemistry 2023, 4, 304–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ethics of Chemistry From Poison Gas to Climate Engineering, Digital Edition. ; Schummer, J., Børsen, T., Eds.; World Scientific Publishing: Singapore, Hackensack, London, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Riesmeier, M. Can Chemical Substances Be Natural? Ambix 2025, 72, 58–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Figure 1.

The tetrahedron of Sjöström.

Figure 1.

The tetrahedron of Sjöström.

Figure 2.

The tetrahedron of Sjöström for aniline.

Figure 2.

The tetrahedron of Sjöström for aniline.

Figure 3.

Chemical Hazard Symbols for Aniline.

Figure 3.

Chemical Hazard Symbols for Aniline.

Figure 4.

The formula of aniline, Ph-NH2..

Figure 4.

The formula of aniline, Ph-NH2..

Figure 5.

The formula of quinine.

Figure 5.

The formula of quinine.

Figure 6.

The binary liquid/vapor water-aniline diagram.

Figure 6.

The binary liquid/vapor water-aniline diagram.

Figure 7.

A diazotization reaction (synthesis of methyl benzene diazonium chloride).

Figure 7.

A diazotization reaction (synthesis of methyl benzene diazonium chloride).

Figure 8.

Mauveine A and B.

Figure 8.

Mauveine A and B.

Figure 9.

Mauveine B2 and C.

Figure 9.

Mauveine B2 and C.

Figure 11.

First three steps of the diazotization reaction: the formation of the nitrosyl cation. Source: Wikimedia Commons (2012).

Figure 11.

First three steps of the diazotization reaction: the formation of the nitrosyl cation. Source: Wikimedia Commons (2012).

Figure 12.

The remaining six steps of the diazotization reaction for the formation of the aryldiazonium cation. Source: Wikimedia Commons (2012).

Figure 12.

The remaining six steps of the diazotization reaction for the formation of the aryldiazonium cation. Source: Wikimedia Commons (2012).

Figure 14.

The mechanism of the electrophilic aromatic substitution reaction with the π-complex.

Figure 14.

The mechanism of the electrophilic aromatic substitution reaction with the π-complex.

Figure 15.

Some examples of dyed fabric samples contained in W. Crookes' handobook. Photos reproduced by kind permission of the Society of Dyers and Colourist Textile Collection, Perkin House, Longlands Street, Bradford (UK).

Figure 15.

Some examples of dyed fabric samples contained in W. Crookes' handobook. Photos reproduced by kind permission of the Society of Dyers and Colourist Textile Collection, Perkin House, Longlands Street, Bradford (UK).

Figure 16.

Portrait of Geltrude Mäda Primavesi, Public domain, via The Metropolitan Museum of Art website.

Figure 16.

Portrait of Geltrude Mäda Primavesi, Public domain, via The Metropolitan Museum of Art website.

Figure 17.

Plate from W. Crookes's handbook showing a woman and child busy spreading color. Photos reproduced by kind permission of the Society of Dyers and Colourists Textile Collection, Perkin House, Longlands Street, Bradford (UK).

Figure 17.

Plate from W. Crookes's handbook showing a woman and child busy spreading color. Photos reproduced by kind permission of the Society of Dyers and Colourists Textile Collection, Perkin House, Longlands Street, Bradford (UK).

Table 1.

Some chemical-physical properties of aniline.

Table 1.

Some chemical-physical properties of aniline.

| Properties |

Values |

| Molar mass |

93.14 g/mol |

| d (25 °C) |

1.022 g/cm3

|

| Teb (1013 hPa) |

184,3 °C |

| Tfus (1013 hPa) |

- 6.2 °C |

| Solubility in water (25 °C) |

36 g/l |

| pKa (25 °C) |

4.6 |

| pKb (25 °C) |

9.4 |

| Flame point |

76 °C |

| Explosion limits |

1.2 - 11% vol. |

| Autoignition temperature |

540 °C |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).