1. Introduction

When the expression “Islamic Mathematics” comes to mind, it often conjures up memories of the Golden Age of Islam (c.8th-14th centuries), a period of extraordinary intellectual efflorescence. Scholars like Muhammad ibn Musa al-Khwarizmi, whose name bequeathed ‘algorithm’ and whose book title Al-Jabr gave us ‘algebra’, and Omar Khayyam, who developed geometric solutions to cubic equations, made foundational contributions that were transmitted to Europe and shaped the course of global science (Frasser, 2024). However(Chande, 2024), the contemporary movement known as the ‘Islamization of Mathematics’ is a distinct phenomenon. It is not a historical descriptor but a modern philosophical and educational project, born from the wider intellectual current of the ‘Islamization of Knowledge’ (IoK).

The IoK movement emerged in the latter half of the 20th century as a response to the perceived intellectual and cultural dominance of the West, which was seen as a legacy of colonialism (Jain, 2023). Its proponents argue that modern Western knowledge systems are built upon a secular, materialist epistemology that is fundamentally at odds with an Islamic worldview. The IoK project, therefore, seeks to “recast knowledge as it is currently constituted” by re-integrating it with Islamic ethical and metaphysical principles (Chande, 2023; Musa, 2021).

This paper explores the specific application of this ambitious project to the discipline of mathematics. It will argue that the Islamization of Mathematics is less about altering established mathematical axioms or theorems and more about fundamentally reorienting the philosophy, pedagogy, and ultimate purpose of mathematical education. This paper will investigate the philosophical underpinnings of this movement, analyse its critique of conventional mathematics, detail its proposed curricular manifestations, and critically evaluate the challenges and debates it engenders.

2. The Philosophical Foundations: The Islamization of Knowledge

To understand the call to Islamize mathematics, one must first grasp the principles of the broader IoK movement, championed by two key figures: the Palestinian American scholar Ismail al-Faruqi and the Malaysian philosopher Syed Muhammad Naquib al-Attas(Chande, 2023; Musa, 2021).

Although their approaches differ in emphasis, both identified a ‘malady of the ummah’ (global Muslim community) rooted in an educational dualism that separates religious and secular knowledge (Usman, 2022; Ashimi, 2022).

For Al-Faruqi and his intellectual home, the International Institute of Islamic Thought (IIIT), the core task is to master modern disciplines, identify their underlying secular assumptions, and then infuse them with Islamic values and perspectives (Usman, 2022; Ashimi, 2022). On the other hand, emphasizes the problem’s psychological, spiritual, and linguistic components, claiming that the major challenge is the secular ‘de-sacralization’ of knowledge and nature (Dhaifi et al., 2022; Idris and Yanti, 2023; Suandi, 2024).

Tawhid—Allah’s absolute oneness and sovereignty—is the unifying principle embraced by all IoK proponents. Tawhidism holds that there is no ultimate distinction between the holy and profane, the spiritual and material. All of creation is a sign (ayah) pointing to the Creator, hence all knowledge, whether of natural occurrences or abstract relations, leads to knowing Allah (Choudhury, 2020; Ozalp, 2023).

The order, pattern, and harmony discovered by mathematics are not mere coincidences of a random universe but are manifestations of the divine order and wisdom (mizan) mentioned in the Qur’an (55:7-9). Thus, the pursuit of mathematical knowledge should be an act of reverence and contemplation (Sunarya et al., 2021).

3. Critiquing ‘Western’ Mathematics: A Crisis of Values

Proponents of Islamized mathematics contest the widely held belief that mathematics is a purely objective, universal, and value-free discipline. While they are not skeptical of the validity of mathematical proofs (e.g., 2 + 2 = 4), they contend that the philosophy and pedagogy surrounding their teaching are imbued with unspoken secular-humanist principles (Skovsmose, 2023; Baker, 2023; Müller, 2025). This viewpoint has similarities in Western critical mathematics education, which contends that mathematics is not culturally neutral but carries latent values.

The critique from an IoK perspective operates on several levels. First, it targets the perceived utilitarianism of modern mathematics education. Students are often taught to view mathematics primarily as a tool for economic gain, technological advancement, and material control over nature (Putawa, 2024; Istanto et al., 2025; Uddin and Ushama, 2024). This instrumentalist approach, it is argued, detaches mathematics from any higher ethical or spiritual purpose, reducing it to a problem-solving mechanism for a consumerist society.

Second, it critiques the implicit philosophy of pure rationalism that underpins mathematical practice. The epistemology presented in a typical mathematics classroom suggests that human reason is the ultimate arbiter of truth, independent of revelation or divine reality (Fakhrurrazi et al.,2024). This anthropocentric view can lead to intellectual arrogance and a vision of the cosmos as a soulless machine understandable and controllable by humanity alone, a perspective fundamentally opposed to the Islamic view of humanity as a vicegerent (khalifah) of Allah, entrusted with stewardship of the Earth (Hussien, 2022). As Ziauddin Sardar provocatively states (Butt,2022) “conventional mathematics is an imperialistic enterprise of a single culture.”

4. Envisioning an Islamized Mathematics Curriculum

The practical application of the Islamization of Mathematics is not about creating a new set of axioms but about pedagogical and curricular re-framing. It is an attempt to change the consciousness of the student and teacher, embedding the learning process within an Islamic matrix of meaning (Abdullah, 2020). This can be actualised in several ways:

Axiological Integration: This involves explicitly linking mathematical study to core Islamic values (akhlaq). The harmony and symmetry in geometry can be presented as reflections of divine beauty (jamal) and perfection (itqan). The precision of mathematics can be tied to the Islamic value of justice (‘adl) and balance (mizan) (Busti and Saputra, 2024). Word problems can be re-contextualized from scenarios of stock market gains to calculations involving Islamic inheritance law (fara’id), charitable donations (zakat), or pilgrimage logistics (Herindar and Shikur, 2023).

Epistemological Reframing: An Islamized curriculum would begin by positing Allah as the ultimate source of all order and rationality. Mathematics laws are not human inventions, but rather human discoveries of an already existing divine design (Sunarya et al., 2021). Muslim mathematicians such as al-Khwarizmi, al-Battani, and Thabit ibn Qurra’s contributions would be taught as instances of how a Tawhidic worldview inspired scientific inquiry (Ashraf et al., 2023), rather than as historical footnotes.

Thematic Integration: Mathematical issues can be linked to Islamic theological teachings. The study of infinity in calculus can serve as a springboard for discussions on Allah’s infinite attributes versus the finitude of creation(Naim and Widjayanto, 2024). The concepts of probability and statistics can be explored in relation to the theological concepts of divine decree (

qadar) and human free will (

ikhtiyar) (Zain, 2010). The geometric patterns prevalent in Islamic art and architecture, from mesmerising tessellations to complex muqarnas, can be analysed not just as artistic expressions but as mathematical explorations of unity in multiplicity, a core theme of

Tawhid (Moradzadeh and Ebrahimi, 2020; Hillenbrand, 2024). Visual illustrations are portrayed through

Figure 1,

Figure 2,

Figure 3,

Figure 4,

Figure 5,

Figure 6,

Figure 7,

Figure 8,

Figure 9,

Figure 10,

Figure 11,

Figure 12 and

Figure 13 (c.f., Moradzadeh and Ebrahimi, 2020). In principle, Islamic geometric patterns involve fractal patterns, which are entwined with Fractal geometry(Mageed and Bhat 2022; Mageed and Mohamed, 2023; Mageed, 2023; Mageed and Nazir, 2024; Mageed, 2024 a-m; Mageed, 2025 a-c).

5. Challenges, Debates, and Criticisms

The process of Islamizing mathematics has considerable hurdles and outspoken opponents, including many Muslim intellectuals and scientists. The most formidable objection concerns mathematics’ universality. Critics argue that mathematical truths are objective, cross-cultural, and unaffected by religious or philosophical constraints, a universally established theorem.

From this viewpoint, attempting to “Islamize” a universal language is not only redundant but also risks ghettoizing Muslim students by presenting them with a parochial version of a global discipline (Ringer, 2020). Pervez Hoodbhoy, a prominent physicist and critic, argues that this approach confuses the context of discovery with the context of justification, and that attaching religious labels to science and mathematics is a “linguistic trick” that produces no new knowledge (Khan, 2024).

A second major concern is the risk of dogmatism. If mathematics is taught as a direct manifestation of divine will, could this stifle the very spirit of critical inquiry and creative exploration that drives mathematical progress? A student might hesitate to question axioms or explore non-intuitive mathematical spaces if such activities are perceived as questioning a divinely sanctioned order (Çoruh, 2020). This could subordinate mathematical reason to theological doctrine, potentially hampering rather than fostering intellectual excellence.

Third, there are immense practical hurdles. The project calls to produce fresh textbooks, instructional materials, and, perhaps most significantly, the training of teachers fluent in both mathematics and Islamic philosophy (Mahmudulhassan et al., 2024). This is still a specialized area, and the institutional ability to carry out such a curriculum on a wide scale is now constrained. Last of all, the IoK movement itself is not homogenous. Those who support a thorough, philosophical integration (the ‘Al-Attas school’) are constantly at odds with those who favour a more practical approach of just contextualising issues and honouring historical contributions (a frequent reading of the ‘Al-Faruqi school’). Other Muslim thinkers argue that the whole project is off target; instead, they contend that Muslims should only aim for excellence within the current universal frameworks of science and mathematics, believing that an honest faith is totally compatible with these goals without the need for an explicit ‘Islamization’ label (Naim and Widjayanto, 2024).

6. Conclusion

The Islamization of Mathematics is a complex and ambitious intellectual project that seeks to do more than just add historical footnotes or religious word problems to a curriculum. It’s a deeply philosophical effort to fix a felt conflict between knowledge and values, between reason and revelation. Its supporters see a pedagogy whereby the investigation of numbers, patterns, and forms turns into a means of spiritual reflection and the development of a Allah-conscious worldview. They hope to turn mathematics from a simple instrument of material dominance into a way of appreciating the divine order of the cosmos by setting it inside the unifying idea of Tawhid(the unwavering belief in the oneness and uniqueness of Allah). But strong criticisms of the project include the universality of mathematical truth, the possibility for dogma, and the great practicalities of application abound. Still open is the conflict between the need to develop a spiritually whole education and the abstract, universal character of math. In the end, the main contribution of the Islamization of mathematics could not be the development of a new mathematical paradigm but rather its function as a trigger for a far more extensive and critical dialogue. Do all educations provide the same level of value, regardless of whether they are Muslim or not? By doing so, it emphasizes the never-ending search for meaning as well as truth in our search of information.

References

- Abdullah, M. A. The intersubjective type of religiosity: Theoretical framework and methodological construction for developing human sciences in a progressive muslim perspective. Al-Jami’ah: Journal of Islamic Studies 2020, 58(1), 63–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashimi, T. A. Islam and secularism: Compatible or incompatible. International Journal of Social Science Research 2022, 4(1), 46–57. [Google Scholar]

- Ashraf, A.; Saeed, H. M.; Awan, M. I. Muslims Scientists’ Works and The Western Approach: A Short Review. AL-IDA’AT Research Journal 2023, 3(2). [Google Scholar]

- Baker, M. The Western mathematic and the ontological turn: Ethnomathematics and cosmotechnics for the pluriverse. In Indigenous knowledge and ethnomathematics; Springer International Publishing; Cham, 2023; pp. 243–276. [Google Scholar]

- Busti, I.; Saputra, R. The Axiological Foundations of Knowledge: A Comparison of Western and Islamic Perspectives and Their Integration in Supporting the Achievement of SDGs. Profetika: Jurnal Studi Islam 2024, 25(02), 421–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chande, A. Global politics of knowledge production: The challenges of Islamization of knowledge in the light of tradition vs secular modernity debate. Nazhruna: Jurnal Pendidikan Islam 2023, 6(2), 271–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choudhury, M. A. Tawhid and Shari’ah: a transdisciplinary methodological enquiry; Springer Nature, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Çoruh, H. Relationship between religion and science in the Muslim modernism. Theology and Science 2020, 18(1), 152–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhaifi, I.; Zakariya, Z.; Salehudin, M. Islamic Education Optimized Towards the Essence of Education in Islamic Teachings. Review of Islamic Studies 2022, 1(2), 137–145. [Google Scholar]

- Fakhrurrazi, F.; Wasilah, N.; Jaya, H. Islam and knowledge: Harmony between sciences and faith. Journal of Modern Islamic Studies and Civilization 2024, 2(01), 45–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frasser, C. E. A Course of Algebra (PART I). arXiv 2024, arXiv:2411.11873. [Google Scholar]

- Herindar, E.; Shikur, A. A. Islamic finance and sustainable development goals (SDGs): text analytics using R. Finance and Sustainability 2023, 1(1). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hillenbrand, R. Islamic art and architecture. Thames & Hudson. 2024.

- Hussien, S. Islamic religious education and multiculturalism in Malaysia: University students’ perspectives. The Bloomsbury handbook of religious education in the global south 2022, 353. [Google Scholar]

- Idris, M. A.; Yanti, C. M. Basic Concepts of Islamic Education According to Abuddin Nata. ISTIFHAM: Journal Of Islamic Studies 2023, 274–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Istanto, D.; Zarkasyi, H. F.; Arroisi, J.; Rachim, D. K. N.; Rusli, R. A. Al-Faruqi’s Islamization of Science in Sardar’s Critical Perspective. Jurnal Filsafat 2025, 35(1). [Google Scholar]

- Jain, S. Epistemological Perspectives on IOK (Islamization of Knowledge) in the Western World, and Its Implications for the Judeo-Christian Milieu. Epistemological Perspectives on IOK (Islamization of Knowledge) in the Western World, and Its Implications for the Judeo-Christian Milieu (June 13, 2023), 2023.

- Khan, H. U. Science and Religion: The Relationship between Islamic Teachings and Modern Cosmology. International Journal of the Universe and Humanity in Islamic Vision and Perspective 2024, 1(1), 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Mageed, I. A. Fractal Dimension (Df) of Ismail’s Fourth Entropy (with Fractal Applications to Algorithms, Haptics, and Transportation. In 2023 international conference on computer and applications (ICCA); IEEE, November 2023a; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Mageed, I. A. The Fractal Dimension Theory of Ismail’s Third Entropy with Fractal Applications to CubeSat Technologies and Education. Complexity Analysis and Applications 2024a, 1(1), 66–78. [Google Scholar]

- Mageed, I. A. Fractal Dimension of the Generalized Z-Entropy of The Rényian Formalism of Stable Queue with Some Potential Applications of Fractal Dimension to Big Data Analytics, 2024b.

- Mageed, I. A. Fractal Dimension (Df) Theory of Ismail’s Entropy (IE) with Potential Df Applications to Structural Engineering. Journal of Intelligent Communication 2024c, 3(2), 111–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mageed, I. A. A Theory of Everything: When Information Geometry Meets the Generalized Brownian Motion and the Einsteinian Relativity. J Sen Net Data Comm 2024d, 4(2), 01–22. [Google Scholar]

- Mageed, I. A. The Generalized Z-Entropy’s Fractal Dimension within the Context of the Rényian Formalism Applied to a Stable M/G/1 Queue and the Fractal Dimension’s Significance to Revolutionize Big Data Analytics. J Sen Net Data Comm 2024e, 4(2), 01–11. [Google Scholar]

- Mageed, I. A. Do You Speak The Mighty Triad?(Poetry, Mathematics and Music) Innovative Teaching of Mathematics. MDPI preprints. 2024j.

- Mageed, I. A. Fractals Across the Cosmos: From Microscopic Life to Galactic Structures, 2025c.

- Mageed, I. A. The Hidden Poetry & Music of Mathematics for Teaching Professionals: Inspiring Students through the Art of Mathematics: A Guide for Educators; Eliva Press, 2025a; Available online: https://www.elivabooks.com/en/book/book-1450104825.

- Mageed, I. A.; Bhat, A. H. Generalized Z-Entropy (Gze) and fractal dimensions. Appl. math 2022, 16(5), 829–834. [Google Scholar]

- Mageed, I. A.; Mohamed, M. Chromatin can speak Fractals: A review, 2023.

- Mageed, I.A. Do You Speak The Mighty Triad?(Poetry, Mathematics and Music) Innovative Teaching of Mathematics. MDPI Preprints. 2024f.

- Mageed, I.A. The Mathematization of Puzzles or Puzzling Mathematics Innovative Teaching of Mathematics. Preprints 2024g. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mageed, I.A. Let’s All Dance and Play Mathematics Innovative Teaching of Mathematics. Preprints 2024h. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mageed, I.A. AI-Generated Abstract Expressionism Inspiring Creativity Through Ismail A Mageed’s Internal Monologues in Poetic Form. Preprints 2024i. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mageed, I.A. The Mathematization of Puzzles or Puzzling Mathematics Innovative Teaching of Mathematics. Preprints 2024k. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mageed, I.A. Let’s All Dance and Play Mathematics Innovative Teaching of Mathematics. Preprints 2024l. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mageed, I.A. AI-Generated Abstract Expressionism Inspiring Creativity Through Ismail A Mageed’s Internal Monologues in Poetic Form. Preprints 2024m. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mageed, I.A. The Hidden Dancing & Physical Education of Mathematics for Teaching Professionals; Eliva Press, 2025b; Available online: https://www.elivabooks.com/en/book/book-7724827898.

- Mageed, I.A.; Nazir, A.R. AI-Generated Abstract Expressionism Inspiring Creativity through Ismail A Mageed’s Internal Monologues in Poetic Form. Annals of Process Engineering and Management 2024, 1(1), 33–85. [Google Scholar]

- Mahmudulhassan, M.; Waston, W.; Muthoifin, M.; Khondoker, S. U. A. Understanding the Essence of Islamic Education: Investigating Meaning, Essence, and Knowledge Sources. Solo Universal Journal of Islamic Education and Multiculturalism 2024, 2(01), 27–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moradzadeh, S.; Nejad Ebrahimi, A. Islamic geometric patterns in higher dimensions. Nexus Network Journal 2020, 22(3), 777–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, D. Towards a critical pragmatic philosophy of sustainable mathematics education. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2504.17149. [Google Scholar]

- Musa, M. F. Naquib Al-Attas’ Islamization of Knowledge; ISEAS-Yusof Ishak Institute, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Naim, S.; Widjayanto, F. R. Muslim Nobel Laureates in science: The legacy of redefining the nexus of Islam and modernity. In Religion, Education, Science and Technology towards a More Inclusive and Sustainable Future; Routledge, 2024; pp. 37–43. [Google Scholar]

- Ozalp, M. Allah in Islamic Theology: Tawhid in Classical Islamic Theology and Said Nursi’s Risale-i Nur; Rowman & Littlefield, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Putawa, R. A. Islamization of science: Ziauddin sardar’s critique of the universality of science. Dharmakirti: International Journal of Religion, Mind and Science 2024, 1(2), 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ringer, M. M. Islamic Modernism and the Re-Enchantment of the Sacred in the Age of History; Edinburgh University Press, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Skovsmose, O. Critique of Mathematics. In Critical Mathematics Education; Springer International Publishing; Cham, 2023; pp. 145–154. [Google Scholar]

- Suandi, H. H. The Concept Of Islamic Education According To Ibn Khaldun, 2024.

- Sunarya, P. A.; Lutfiani, N.; Santoso, N. P. L.; Toyibah, R. A. The importance of technology to the view of the Qur’an for studying natural sciences. Aptisi Transactions on Technopreneurship (ATT) 2021, 3(1), 58–67. [Google Scholar]

- Uddin, H.; Ushama, T. An Analysis of Ziauddin Sardar’s Approach to Integration of Knowledge. Journal of Islam in Asia (E-ISSN 2289–8077) 2024, 21(3), 257–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usman, Z. A. Changes And Development Of The Meaning Of Secularism In Islamic Thought. Al-Risalah: Jurnal Studi Agama Dan Pemikiran Islam 2022, 13(1), 16–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

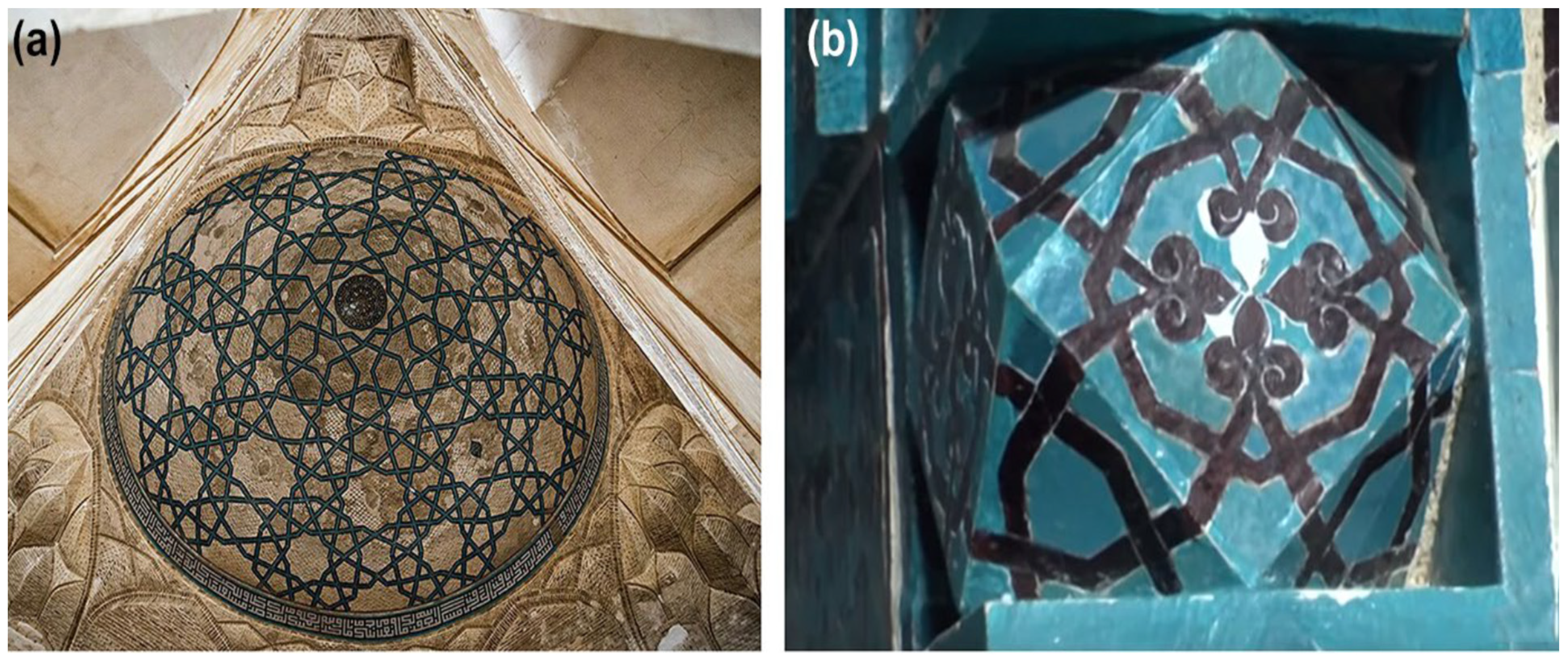

Figure 1.

Planar pattern historical advancements include an Islamic pattern projection on the inner dome of Iran’s Jameh Mosque of Saveh. Projected obtuse pattern on octahedron at the Mehrab of Eşrefoğlu Mosque, Konya, Turkey.

Figure 1.

Planar pattern historical advancements include an Islamic pattern projection on the inner dome of Iran’s Jameh Mosque of Saveh. Projected obtuse pattern on octahedron at the Mehrab of Eşrefoğlu Mosque, Konya, Turkey.

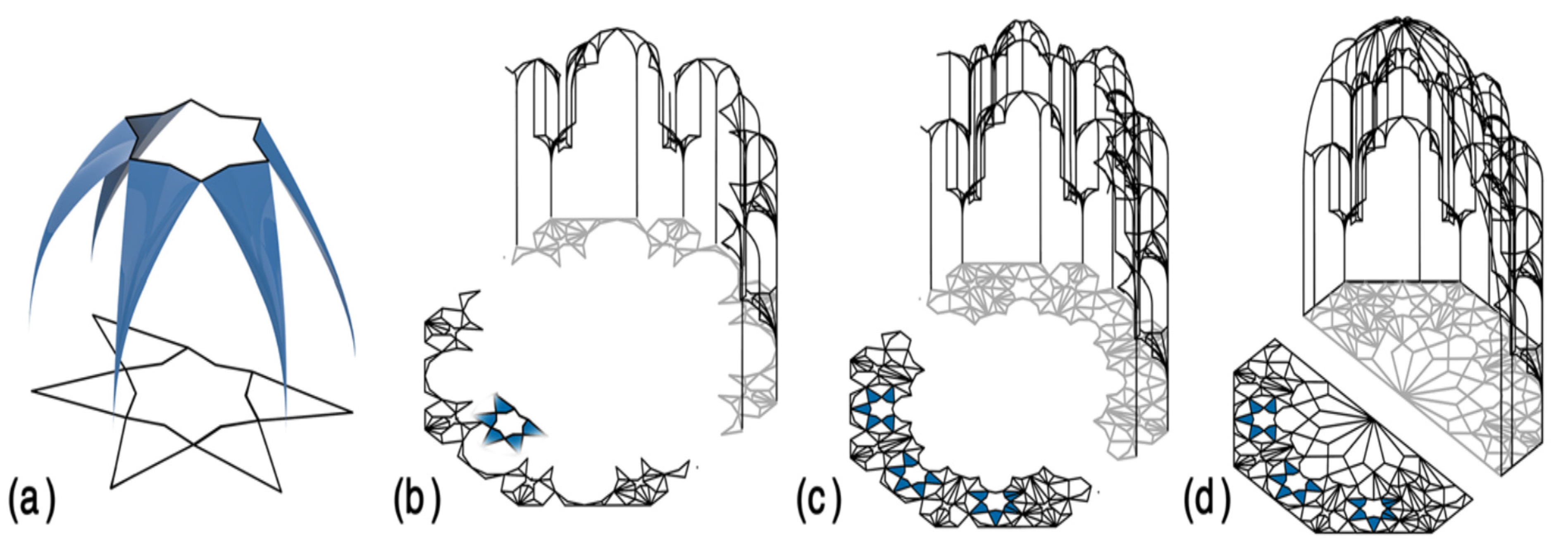

Figure 2.

The four stages involved in building a Muqarnas vault from a plan a defining component; b establishing vault levels; c building vaults; d showing the main vaults in three dimensions.

Figure 2.

The four stages involved in building a Muqarnas vault from a plan a defining component; b establishing vault levels; c building vaults; d showing the main vaults in three dimensions.

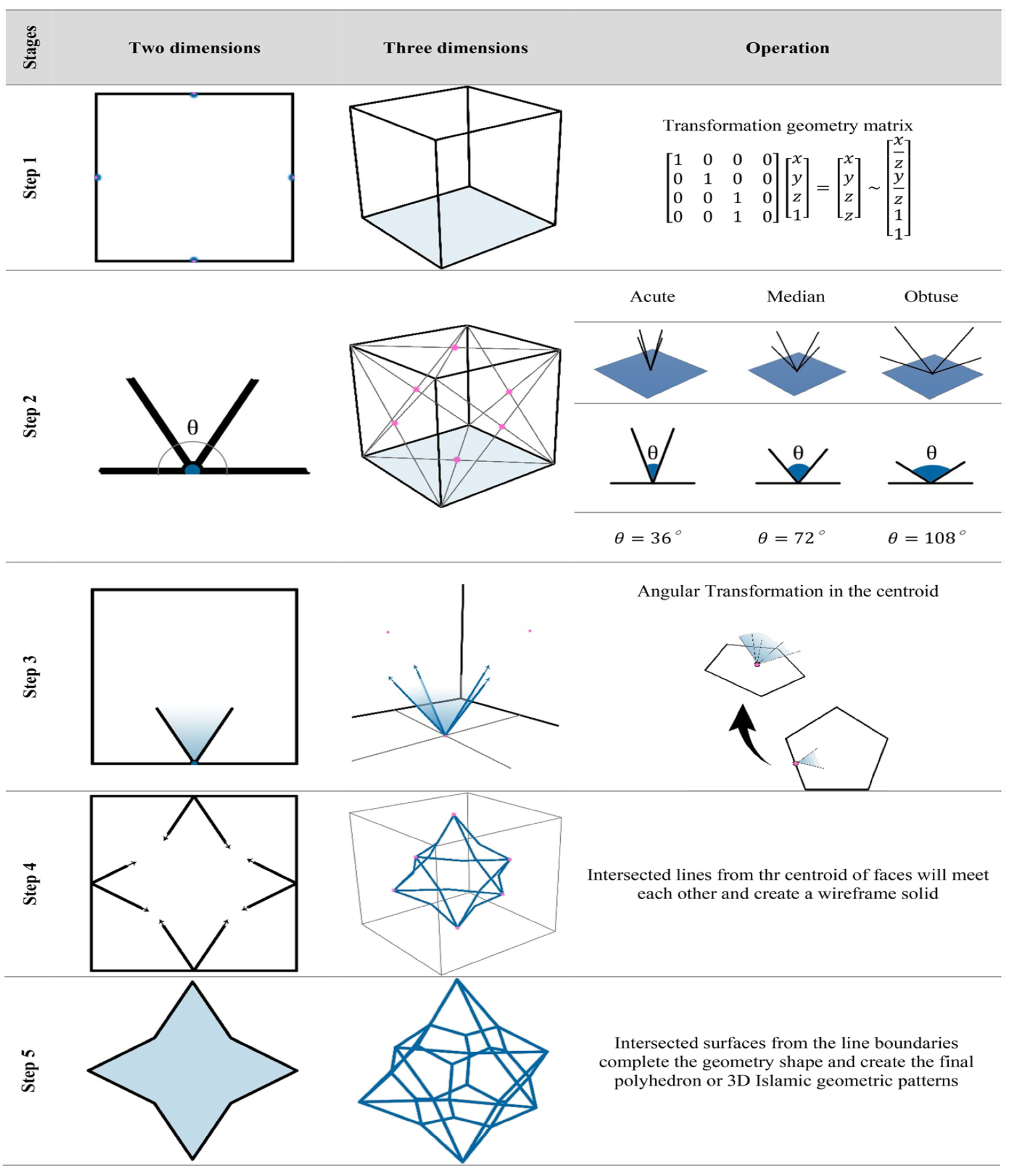

Figure 3.

Methodical procedure for converting 2D Islamic geometric motifs into 3D.

Figure 3.

Methodical procedure for converting 2D Islamic geometric motifs into 3D.

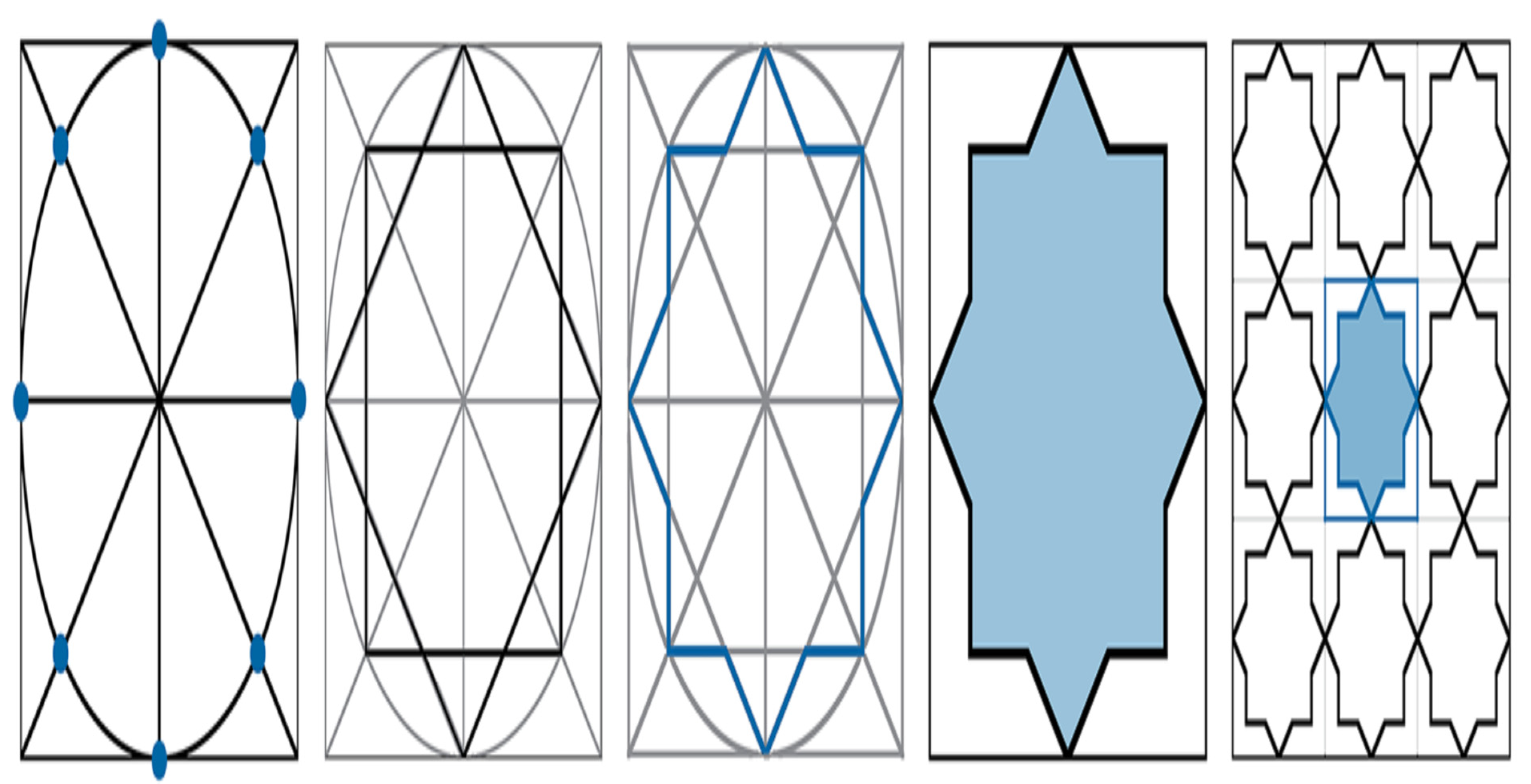

Figure 4.

Point-joint technique with an eight-pointed star design.

Figure 4.

Point-joint technique with an eight-pointed star design.

Figure 5.

The identical pattern in

Figure 4 is transformed into three dimensions using the spatial point-joined approach.

Figure 5.

The identical pattern in

Figure 4 is transformed into three dimensions using the spatial point-joined approach.

Figure 6.

The cube, truncated octahedron, elongated dodecahedron, rhombic dodecahedron, and hexagonal prism are tessellated to create a 3D repeating unit of Islamic geometric motifs.

Figure 6.

The cube, truncated octahedron, elongated dodecahedron, rhombic dodecahedron, and hexagonal prism are tessellated to create a 3D repeating unit of Islamic geometric motifs.

Figure 7.

Aperiodic tiling is the outcome of Islamic geometric designs with Schmitt–Conway–Danzer biprism repeat unit tessellation.

Figure 7.

Aperiodic tiling is the outcome of Islamic geometric designs with Schmitt–Conway–Danzer biprism repeat unit tessellation.

Figure 8.

a side attracts, b the middle attracts, and c the attraction curve is the attraction method for modified parquet deformation.

Figure 8.

a side attracts, b the middle attracts, and c the attraction curve is the attraction method for modified parquet deformation.

Figure 9.

Islamic geometric designs in three dimensions Parquet deformation using unit cells in an elevation view.

Figure 9.

Islamic geometric designs in three dimensions Parquet deformation using unit cells in an elevation view.

Figure 10.

Islamic geometric designs in three dimensions Parquet deformation using unit cells in an elevation view.

Figure 10.

Islamic geometric designs in three dimensions Parquet deformation using unit cells in an elevation view.

Figure 11.

The Islamic geometric patterns’ 4D (tesseract) repeat unit in various photographed shadows.

Figure 11.

The Islamic geometric patterns’ 4D (tesseract) repeat unit in various photographed shadows.

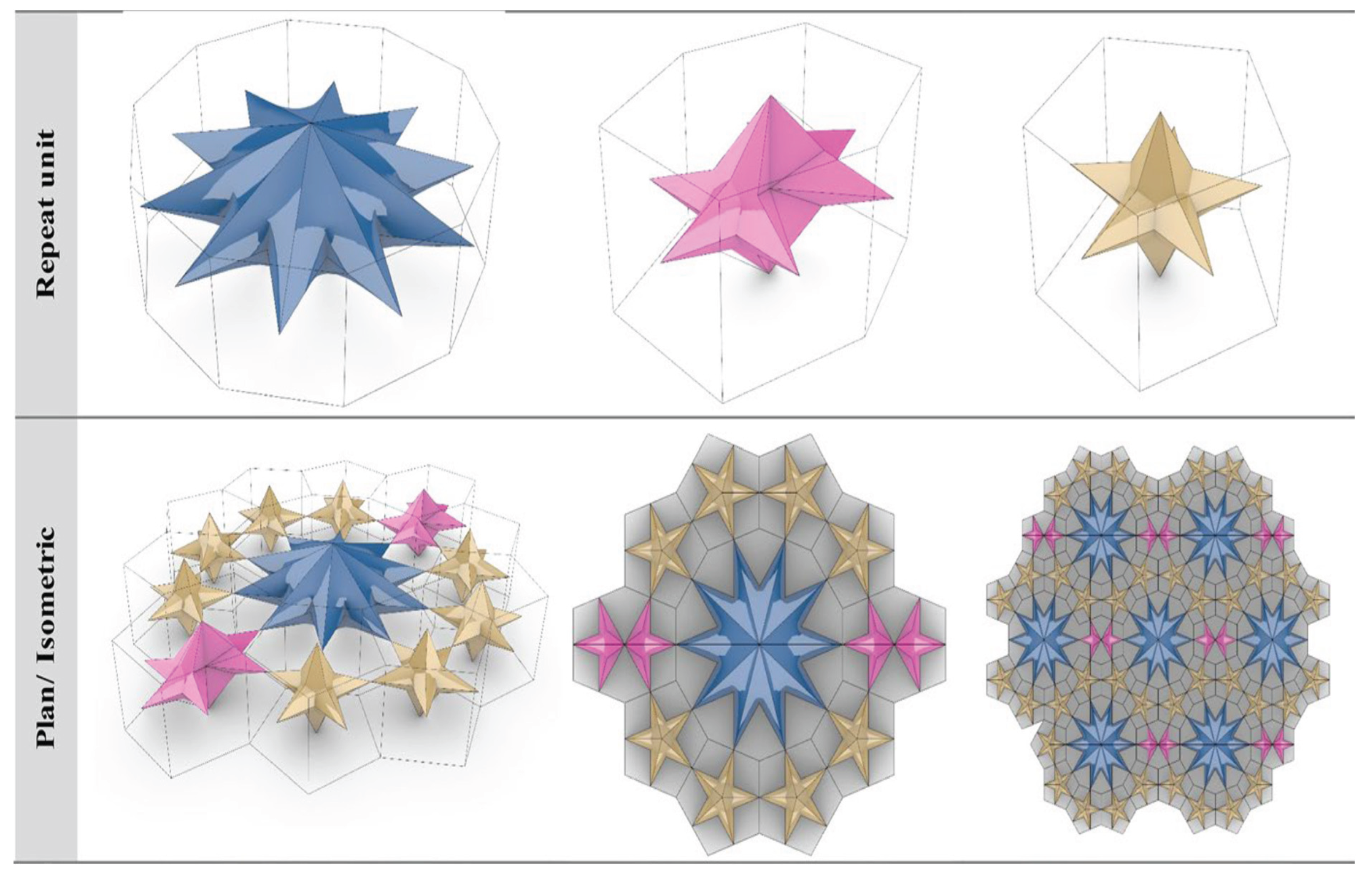

Figure 12.

The ten-pointed star, barrel-shaped hexagon, and five-pointed star are examples of Islamic geometric pattern repetition units with regular and irregular tessellations.

Figure 12.

The ten-pointed star, barrel-shaped hexagon, and five-pointed star are examples of Islamic geometric pattern repetition units with regular and irregular tessellations.

Figure 13.

Islamic geometric pattern repetition units and associated tessellations include the five-pointed star, barrel-shaped hexagon, and ten-pointed star.

Figure 13.

Islamic geometric pattern repetition units and associated tessellations include the five-pointed star, barrel-shaped hexagon, and ten-pointed star.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).