1. Introduction

In the early 1990s, many science education researches [

1] described a clear situation of crisis concerning science teaching. Science education researchers explained this datum underlying: teaching methods centered on simple contents transmission [

2]; the lack of connections with daily life and the resulting students’ difficulty in transferring scientific knowledge from school context to new situations [

3]. Concerning the last point, Howard Gardner stated that “the capacity to take knowledge learned in one setting and apply it appropriately in a different setting is the most basic definition of understanding” [

4]. Obviously, this capacity requires an interdisciplinary vision of the topics covered; that explains why studies on the importance of interdisciplinarity have increased over the years.

Currently, scholars agree in considering the use of the interdisciplinarity a fruitful strategy. The interdisciplinary approach does not require a science syllabus organized by single contents, but it specifies some general topics across the disciplines. In this way, detailed syllabuses are substituted by output-oriented standards focused on problem-solving, analysis and communication skills. There are many definitions of interdisciplinary character, for example, “the capacity to integrate knowledge and modes of thinking drawn from two or more disciplines in order to answer a question, solve a problem or address a topic that is too complex to be dealt with adequately by a single discipline” [

5]. The idea of combining disciplines appeared for the first time in curricular contexts in the 1920s; in 1958 Bloom advocated for an inquiry-oriented integrated curriculum. Some curricular integrations were fully realized, like combined courses in natural and social sciences [

6].

Integrated curricula realization tried to deal with several issues: the criticism of isolated disciplines, perceived as distant from everyday life; the inclusion of personal points of view or experiences as relevant to the learning development; the importance of inquiry skills; the view that forming connections between different fields of knowledge is an essential educational need for success in the 21st century [

7]. Morin insisted on the last point in the framework of his theories on complexity applied to education. According to Morin, “the education of the future is faced with this universal problem because our compartmentalized, piecemeal, disjointed learning is deeply and drastically inadequate to grasp realities and problems which are ever more global, transnational, multidimensional, transversal, poly-disciplinary and planetary”. Therefore, information and data must be placed in their context to have meaning. Consequently, education must encourage “general intelligence” apt to refer to the complex, the context, in a multidimensional way, within a global conception [

8].

Establishing Bachelor’s and Master’s courses, such as those offered by the London Interdisciplinary School, demonstrates considerable progress. At the secondary school level, the application of the interdisciplinary approach is complicated by the necessity of reconciling it with core concepts of learning. Chemistry provides a meaningful example: it needs an interdisciplinary approach to be more attractive and to make clear its essential role in implementing sustainable practices; nevertheless, in order to avoid disappointing chemistry learning outcomes, context-based chemical education requires special precautions. Outcomes of context-based approaches can be positive from an affective development perspective, but they are somewhat disappointing from a cognitive development point of view [

9]. Therefore, criteria for selecting adequate contexts are needed: they should be well-known and relevant for students; they should not distract students’ attention from related chemistry concepts; they should not be too complicated for students or confuse them [

9].

It is also necessary to overcome the “myths” of interdisciplinarity: among these is the belief that an interdisciplinary approach applied to environmental issues can be obtained mainly from problem-solving, underestimating the hermeneutic methods of humanities [

10]. Besides, the interdisciplinary approach requires either strong disciplinarian knowledge or some knowledge of other domains, with a clear perception of one’s limits: even when a project is developed as a team, each member must not limit himself to his own field and totally delegate some aspects to the other members; it is important that the individual (for example, a teacher) has extensive culture and an open mind [

10]. For example, chemistry must be reformulated so as to embrace the different dimensions of sustainability; there is a need for teachers’ training to take into account a broad social-political framework [

11].

Implementing context-oriented chemistry teaching requires particular attention because of the nature of chemistry knowledge, characterised by continuous links between macroscopic and microscopic levels. Focusing on students’ everyday experiences, there is the risk of not dealing with the microscopic level with due attention, as well as non-scientific fields can potentially create difficulties in gaining disciplinary content knowledge.

Based on these considerations, this work describes a sequence aimed at a gradual implementation of some activities revolving around a current problem of global scope that implies the multiple dimensions of sustainability: the production and use of palm oil.

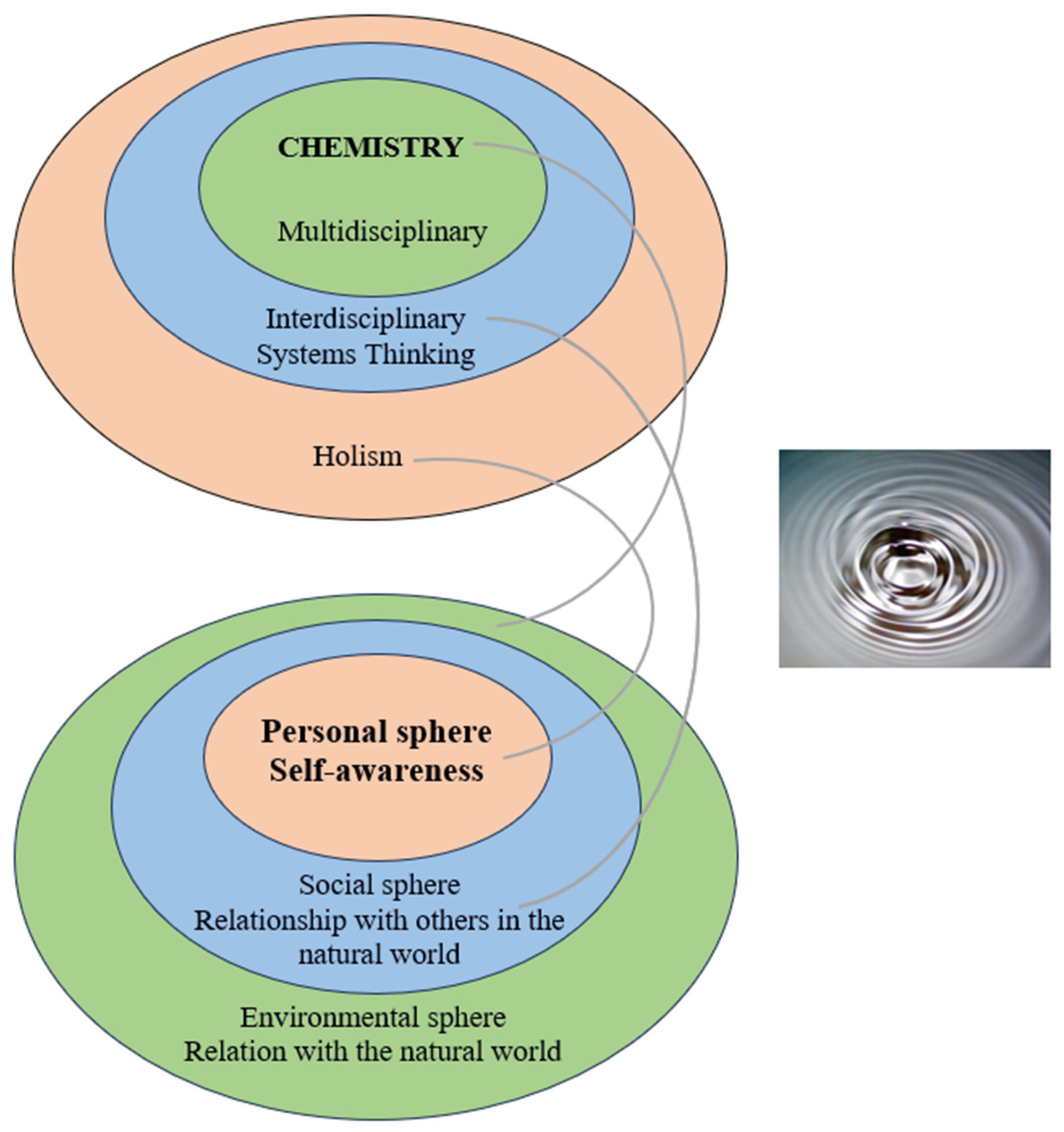

The sequence is divided into three main parts, starting from chemical concepts and gradually broadening (

Figure 1): in the first part, a multidisciplinary approach is adopted, starting from chemical knowledge; in the second part, students afford the issues involved from an interdisciplinary-systemic point of view, the bridge that connects disciplinary and holistic knowledge [

12]; in the last part, the holistic dimension is addressed. The phases listed correspond to a progressive penetration of knowledge into the personal sphere so that it can be internalized without remaining at an epidermal level [

13], as shown in

Figure 1. This is possible thanks to the emphasis placed on ethical issues, which play a key role in any discussion on sustainability [

14].

2. Palm Oil: A Short Overview

Palm oil is a vegetable oil derived from the mesocarp of the fruits of the oil palms. This oil is highly saturated and semi-solid at room temperature; like all the other oils and fats, palm oil is composed of fatty acids esterified with glycerol, with a high concentration (44% by weight) of palmitic acid, a 16-carbon saturated fatty acid. There are various types of palm oil depending on the parts of the plant processed, the extraction process, the degree of refining and other factors.

From December 2014, in the European Union, the use of the generic term “vegetable oil/fat” is not allowed because palm oil must be clearly indicated in the ingredients list on food packaging [

15]. Palm oil’s low price and its chemical and physical properties make it particularly suitable for the confectionery industry (where it substitutes animal butter); about 50% of common consumer products contain palm oil, for example, cookies, chocolate and different snacks. Moreover, approximately 70% of personal care products and household detergents contain products derived from palm oil.

Several studies linked palm oil to cardiovascular diseases [

16], even if other oils have a saturated fats percentage higher than palm oil: coconut oil, very used in the food industry, is 86% saturated, whereas in the oil palm saturated fats percentage is about 49% by weight; in the animal butter, the percentage is around 51%, in the cocoa butter approximately 60% [

17]. Therefore, other oils and fats are saturated more than palm oil. In the presented didactic sequence students are invited to reflect upon that, but the main issue presented is related to another risk lately considered linked to palm oil: cancer onset.

In March 2016, the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) published a study carried out by the EFSA Panel on Contaminants in the Food Chain [

18]; the study concerns risks to human health related to the presence of some chemicals, including 3- and 2-monochloropropanediol (MCPD). These chemicals are originated during the food processing of vegetable oils and fats at temperatures up to 200 °C (higher than usual temperatures in the confectionery industry). Oil palm contains a percentage of 2- and 3- MCPD higher than the related percentages of other vegetable oils and fats. Such chemicals can cause cancer in vitro at very high concentrations, showing evidence of genotoxic potential (in the same way as caffeine or alcohol); however, concentrations involved in genotoxic effects evaluation are not usual in normal nutrition.

In the big picture, the real risk is linked to the frequency and number of consumptions of food containing palm oil; this applies to all types of potentially carcinogenic food, not only palm oil [

17]. Moreover, cancer is not the only disease involved: as specified above, cardiovascular diseases can also be caused by a poorly balanced diet, even if palm oil is replaced by other oils/fats.

In order to produce all the oil palm needed by the food industry, many countries gave up other cultivations, sometimes causing deforestation. That constitutes a serious problem in Southeastern Asia, the geographical area exposed to the risk of reducing drastically biodiversity [

19]. Furthermore, the poorest farmers convert their cultivations to oil palms, profitable but not useful to nourish adequately local populations. In 2004 the Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil (RSPO) established international standards for sustainable palm oil production, but some aspects of RSPPO certification have been disapproved [

20]. It should be specified that the production of coconut oil and cocoa butter presents similar problems in producing countries because of the environmental and economic issues involved. In conclusion, the oil palm case study shows very complex issues involved in evaluating food when considering all factors at play.

3. Materials and Methods

This didactic sequence has been implemented with 4th - 5th-year high school Italian students over the course of about two months; it was repeated three times, in 2021, 2022, 2023, making some improvements from year to year. Italian high school lasts five years, so it is attended by students from 14 to 19 years old; therefore, 4th-5th year Italian high school students are aged 18-19, whereas corresponding students within K-12 system attending the final two years of secondary level (eleventh-twelfth grade of K-12 system) are 17-18 years old.

The teaching sequence starts with three questions asked to the students:

1 Why do claims of different brands of biscuits leave out palm oil content on the packaging?

2 Can palm oil cause cancer?

3 Does palm oil use damage biodiversity?

The didactic sequence is structured in three sections (Sections 1–4), each corresponding to one of the questions above; each section is organized into three phases, according to a work scheme already tested with two other case studies [

21,

22]. Contents involved, phases and activities are specified in

Table 1 and

Table 2 and described in detail in the file attached; this file (named “S1”) contains all the students’ worksheets needed, in reference to the different sections and phases mentioned above. The Sections relating to the three questions reported are described in the following paragraphs.

4. Section 1—Question 1: Palm Oil Content in Food

For this section, 6 h of class time and individual study are required. The students’ worksheets 1–6 in S1 describe in detail the activities carried out. They are aimed at developing students’ skills in relating ingredients and claims of different brands of cookies and understanding the choices underlying advertising messages that involve oil content.

4.1. Phase I

The teacher leads students in analysing four different brands of biscuits showing different lists of ingredients and various claims related to oils/fats content (worksheet 1). Then, students carry out research about the very large use of palm oil in food and the reasons for that (worksheet 2). It is noted that palm oil content is always left out in the product claims, whereas the presence and the percentage values of other oils (sunflower oil, olive oil) are highlighted.

4.2. Phase II

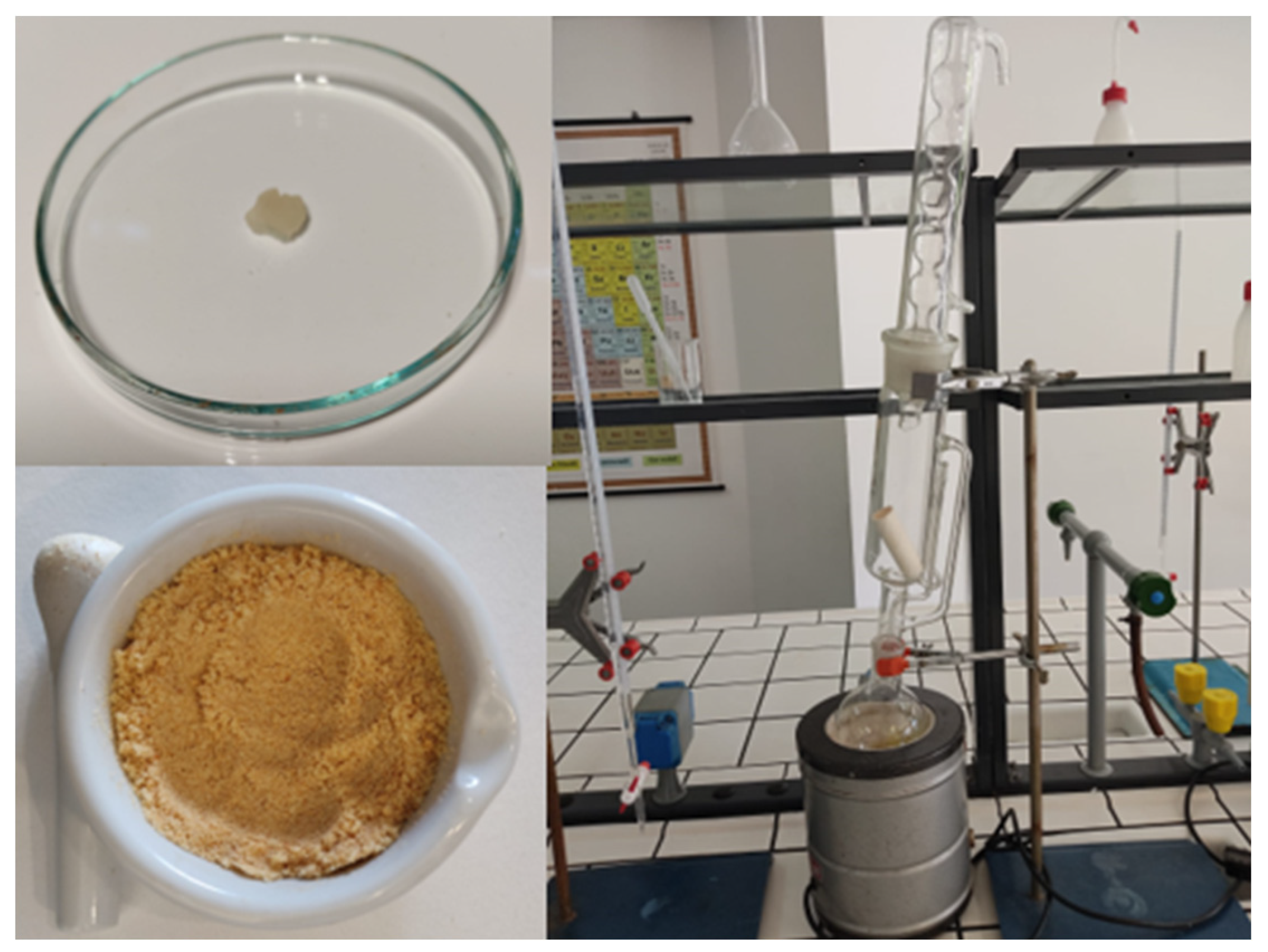

Palm oil is extracted by the Soxhlet extractor (worksheet 3 of S1) of

Figure 2 (which also depicts the ground biscuit sample and the extracted oil) from the biscuits sample (no. 1, worksheet 1 of S1) [

23] containing only this type of oil. The oil extracted can be characterized at least by aspect, density and smoke point to evaluate its degree of chemical purity. The length of the fatty acid carbon chains and the number of their double bonds affect the lipids’ melting point; students have to explain changes in the melting points in terms of intermolecular interactions (worksheet 4).

If extraction is not possible, the average percentage value of palm oil resulting from the scientific literature can be considered in subsequent activities; according to the data collected, the weight percentage of palm oil can reach 2% or more [

24].

The quantities of oil isolated occasionally ranged from 1.5 to 2.8 g for the same type of biscuits. Smoke point and density measurements were also not uniform, presumably due to impurities. However, it should be noted that there are various types of palm oil depending on geographical origin, processing, etc.; a comparison with the data present in scientific literature is, therefore, difficult, as food packaging generally does not indicate the type of palm oil used. Indeed, at an industrial level, it is very common to use mixtures of different oils, even though they can be classified generically as “palm oil”. In any case, the weights obtained are suitable for the subsequent activity on toxic substances in palm oil.

Because saturated fats in food are related to cardiovascular diseases, students are asked to compare saturation degrees of palm oil, animal butter and vegetable butter (cocoa butter), three common ingredients of many foods. In particular, frequent palm oil use in the food industry has been a source of concern in recent years because of well-known reasons brought to students’ attention (worksheet 5).

4.3. Phase III

The students read other time ingredients and claims reported in worksheet 1 and express their considerations in light of the previous activities (worksheet 6); in this way, they pay attention to some advertising strategies not well understood at first glance.

5. Section 2—Question 2: Correlation with Cancer Onset

This section requires 4 h of class time and individual study. The students’ worksheets 7–9 in S1 describe in detail the activities carried out. This section deals with the quantitative evaluation concerning the correlation between food containing palm oil and its potential genotoxic effects

5.1. Phase I

The highest occurrence values of the toxic compounds 2- and 3-MCPD were found in the food group ‘Fats and oils’, with ‘Palm oil/fat’ showing a mean middle bound (MB) level of 2,912 µg/kg for 3-MCPD (from esters), 1,565 µg/kg for 2-MCPD (from esters). In the opinion of toxicologists, the daily dose of 3-MCPD wouldn’t have to exceed 0,8 µg/kg body weight; toxicological information is too limited in order to establish a safe level for 2-MCPD [

18]. The meaning of MB, LB, and UB has to be previously explained during the class of mathematics. Considering the values of 3-MCPD related to different oils and fats (including palm oil), every student can present his oral contribution during a collective discussion about one or more of the following issues (worksheet 7):

- The usual temperatures of food processing in the confectionery industry (where palm oil is largely used).

- All the oils/fats that can develop carcinogenic substances.

- The typical diseases caused by nutrition characterized by large amounts of oils and fats (is cancer the most probable disease?).

- The presence of palm oil among infant formula ingredients.

- The claim “palm oil free” used as an advertisement.

5.2. Phase II

Taking into account the amount of palm oil extracted in the laboratory and their body weight, the students calculate how many biscuits (sample no. 1, worksheet 1 of S1) need to be eaten per day in order to take the maximum amount of 3-MCPD allowed in the opinion of toxicologists (worksheet 8). It is easy to verify that the quantity of this toxic chemical necessary to trigger a possible malignant effect would require too high doses of food containing palm oil.

5.3. Phase III

On the basis of the activities carried out, the students are guided in conceiving some concise recommendations to consumers about biscuits’ purchasing, including considerations about health effects and economic interests.

6. Section 3—Question 3: Concerns about Biodiversity

For this section, 3 h of class time and individual study are required. The students’ worksheets 10–12 in S1 describe in detail the activities carried out. In this section loss of biodiversity and social impacts of palm oil production are presented. Oil palm cultivation caused deforestation in some geographical areas. Primary forests have been cleared and replaced by palm oil plantations. Many palm oil plantations have been developed without agreements with local communities and displacing people from their land. Violations of workers’ rights have also occurred. Other types of plantations allowing vegetable oil extraction entail similar problems, but oil palm is the most convenient oil because palm trees produce 4-10 times more oil than other crops per unit of cultivated land [

25].

6.1. Phase I

A collective discussion can take place in order to deal with the environmental and social impact of oil palm plantations (worksheet 10). Some hints could be:

- Do other types of plantations for vegetable oil industrial production raise similar problems?

- Many people residing in the exploited lands earn their living from the palm oil production industry.

During the following activity, students analyze and comment on a diagram extracted from a scientific article [

19] about palm tree plantations (worksheets 11); the diagram (shown in S1) shows how plantation lands are situated mainly in Malaysia and Indonesia. This poses serious dangers for biodiversity and human rights in these geographical areas. This exercise stimulates the skills necessary to interpret visual representations as simple charts, gathering all the implications on the basis of the acquired knowledge.

6.2. Phase II

A subsequent brainstorming could be realized in order to suggest measures aimed at minimizing palm oil production’s negative consequences (worksheet 12)

6.3. Phase III

Sustainable oil palm production is a possible solution in order to contain the negative consequences of the palm oil business. Students analyze shortly all the different aspects involved in sustainable palm oil certification.

7. Considerations on Multidisciplinary Activities Outcomes

The didactic sequences here described involve several issues: oil chemistry, deforestation and biodiversity loss, conditions for agricultural production, health problems, human rights and laws of the market. Teachers must be particularly proficient in focusing on chemistry content, avoiding dispersive activities. That requires not only ongoing further training centered on multidisciplinary methods, but also a strong preparation on disciplinary contents. This last point involves problematic issues in Italy, where most science teachers do not have the cultural background adequate in order to teach chemistry. In many Italian secondary schools, a single teacher - in general with poor academic preparation in chemistry - teaches earth sciences, life sciences and chemistry. Probably, the low interdisciplinary character of science education in Italy is connected to this prevailing academic profile. In fact, while it is true that some university qualifications (e.g., forestry, earth science, agronomy, food science, etc.) guarantee an overall view of the natural world particularly effective, chemistry is the “central science” [

26] acting as linkage with different fields because its privileged position.

8. Interdisciplinary-Systemic Approach

System thinking is crucial in order to develop sustainability competencies [

27] and, in general, complex issues needed for reaching the goals of the UN 2030 Agenda conceived on a global scale [

28]. An essential condition of authentic systemic thinking in understanding global dynamics is the acquisition of the concept of global citizenship. Global citizenship implies conceiving oneself as part of a multitude committed to developing the needed skills in nurturing the sustainability of the physical, psychological and spiritual sides of planet Earth [

29].

Western students should develop a clear perception of the weight of the factors at play: the European Union constitutes less than 6% of the world population, and the inhabitants of the entire West are around 13%. Making our limited world coincide with the extended world is a typical mistake of Western people, generating idealistic, self-centered considerations and, therefore, bearers of a distorted vision of reality [

30].

Global Citizenship Education refers to a complex system of relationships and actions [

31,

32]. The current distorted geopolitics of knowledge is causing ethical destabilization of global school ecosystems [

33,

34]. Systemic thinking is a useful tool to broaden horizons and begin to acquire a global mindset. After an introduction to the different Systems Thinking graphical tools, simplified causal loop diagrams are used [

35], fitting well the needs of students dealing with Systems Thinking diagrams for the first time.

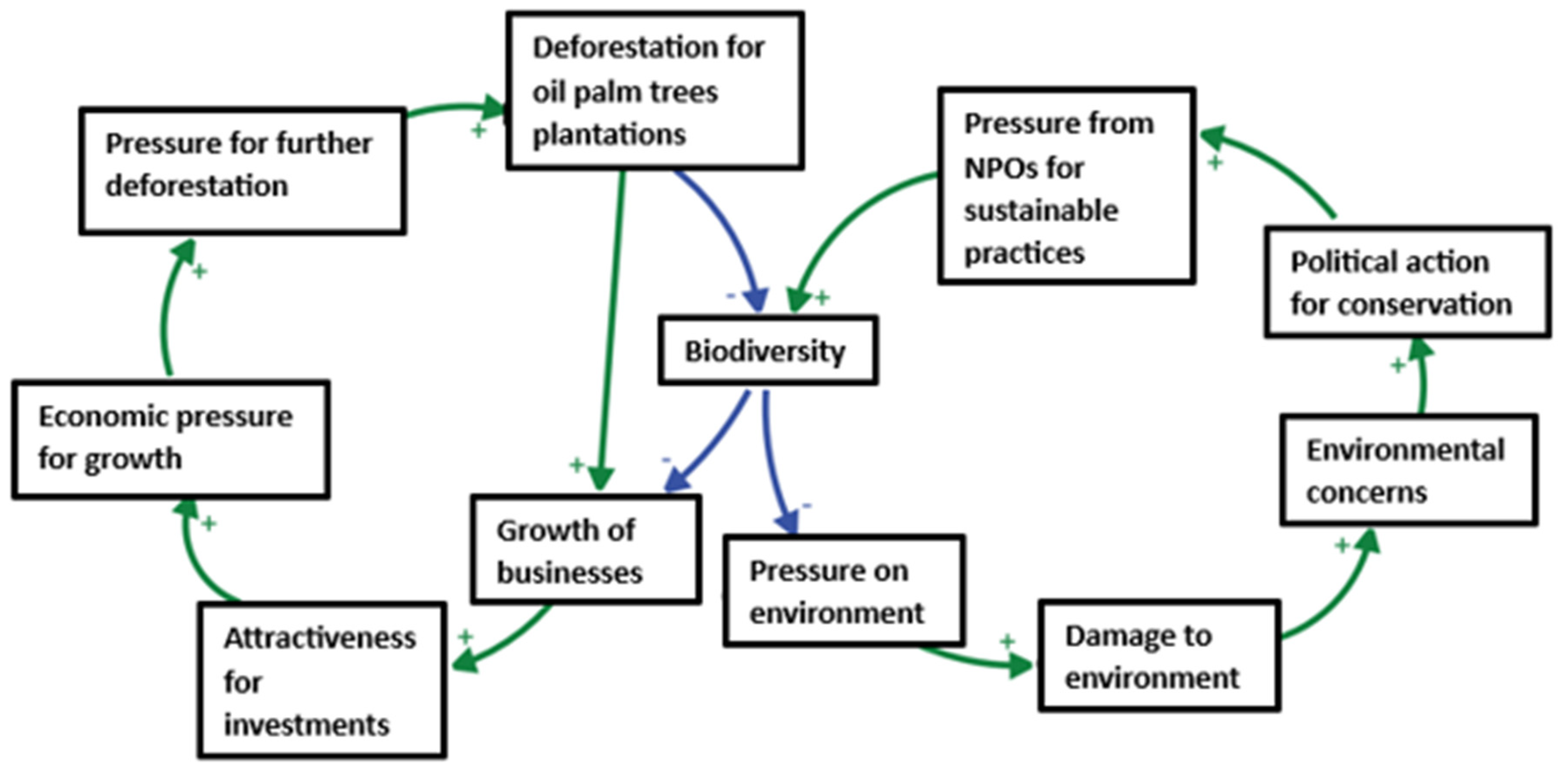

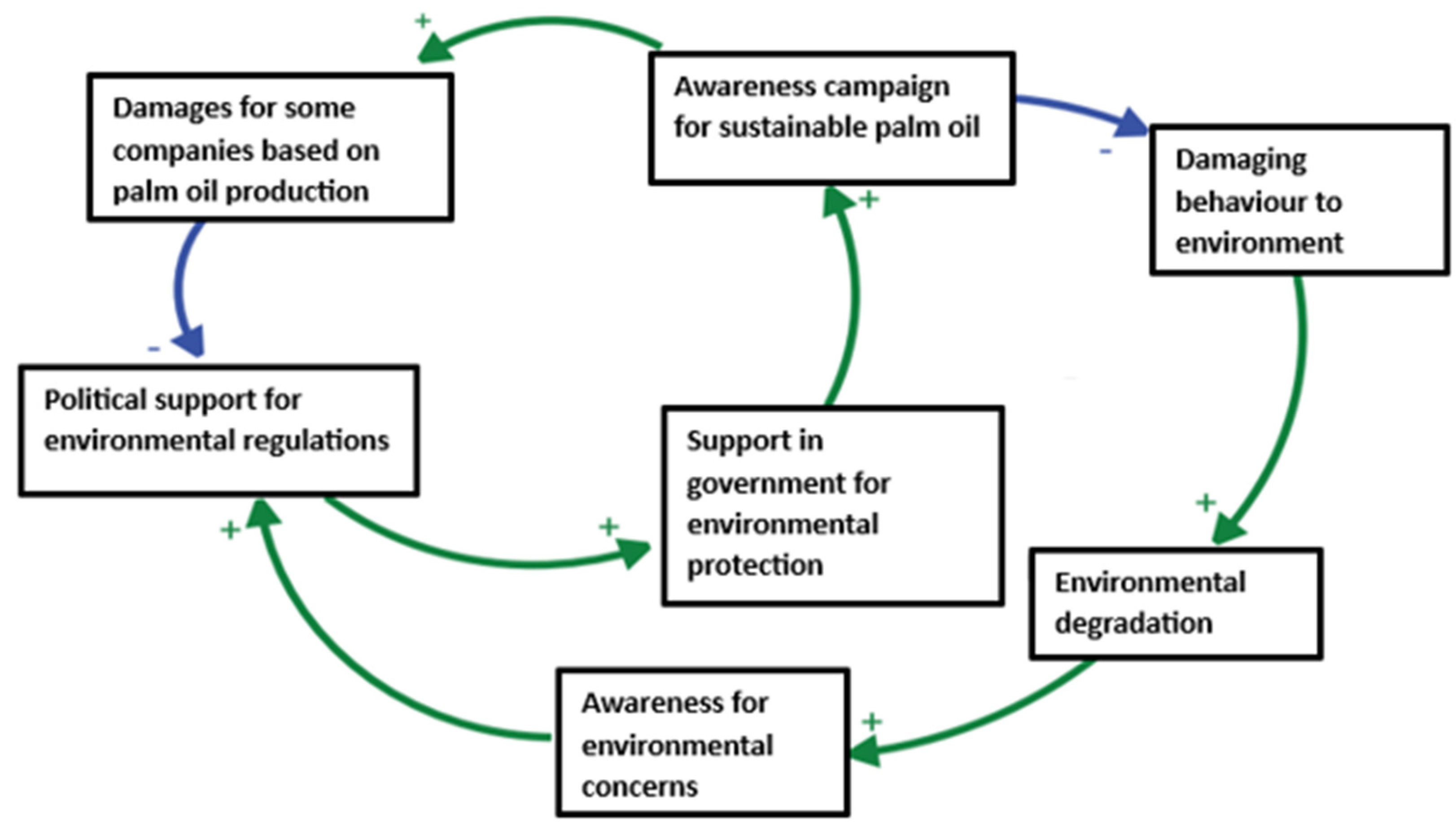

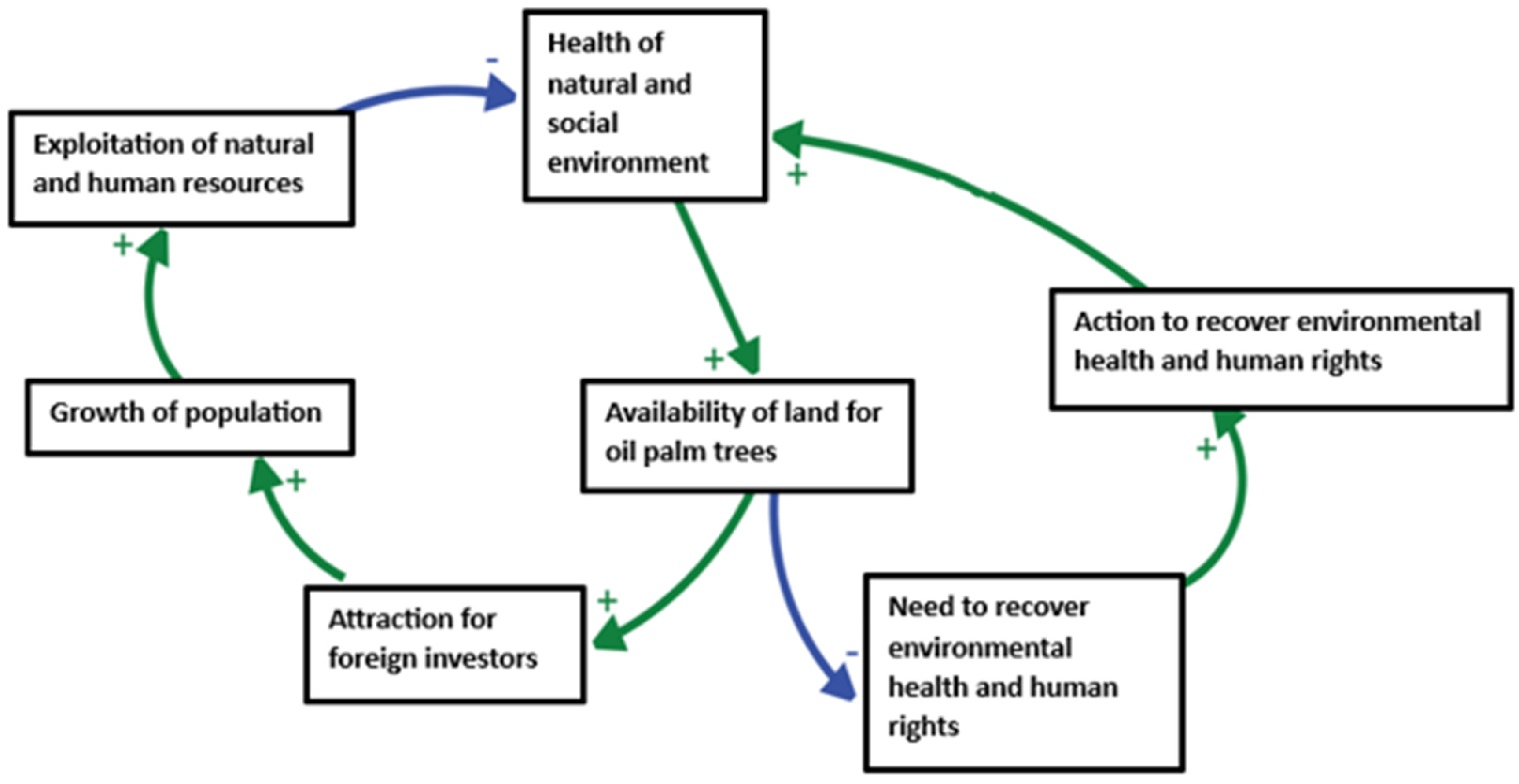

Figure 3,

Figure 4,

Figure 5 and

Figure 6 show some diagrams made by the students’ groups. The arrows indicate the directionality of connections and the presence of feedback loops; the positive sign indicates a strengthening of the variable in the direction of the arrow, while the negative sign indicates a decrease.

9. Holistic Approach

Education for sustainable development can benefit from Two-Eyed Seeing (TES), which combines a holistic and a scientific perspective [

36]. TES was originally introduced to bring together the strengths of Indigenous and Western knowledge. The holistic aspect is important to give value to the psychological and spiritual dimensions of global citizenship [

29], not considered in an exclusively scientific reference context. The analysis of some documents clearly explains the emotional value of palm oil, especially among African populations. The novels “Red Palm Oil Love” [

37] and “The Palm Oil Stain” [

38] refer to this oil in a symbolic way, associating it with romantic or nostalgic feelings. A Nigerian author writes [

39]:

“As an undergraduate student in the U.S., I’d often come across many student demonstrations on campus calling for palm oil boycotts. I was confused at the time to learn that palm oil is a villain in the story of impending climate catastrophe […].

It’s still odd to me to think of this gorgeous and delicious oil that stains most things it touches—many plastic containers have been permanently dyed reddish-orange from storing palm oil–heavy foods, many shirts have had to be bleached—as the same thing found in toothpaste, shampoo or even peanut butter.

I’m still in love with palm oil, though. Not because I would like to ignore facts in order to enjoy my guilty pleasures in peace or because I don’t care about orangutans and other endangered species. I truly do. I’m still in love with it because I understand that the problem isn’t palm oil and its various potential uses. The massive scale in which it’s harvested and refined and all the harrowing ways that the environment and workers are exploited in the process are more about the capitalist proliferation of everything and much less about palm oil itself.”

These words are extremely representative of the conflict between two worlds, allowing us to take the point of view of a person who has lived in two very distant geographical areas. The entire article [

39] synthetically and effectively calls into question the affective dimension, concern for the environment and economic interests at stake in a free-market system. Starting from these considerations, it is possible to best interpret texts that also deal with the topic from an anthropological point of view [

40]: for example, palm tree crops can be considered “racialized” as they might perpetuate some forms of slavery, even though slavery has been legally abolished.

Historical dynamics help to understand why current global citizenship education is dominated by Western values and does not capture the values of other Western-dominated populations such as Africans. While within the context of Africa, the citizen concept is all-encompassing (it includes community, terrestrial and extra-terrestrial world), in ancient Greece, the citizen was conceived at first as belonging to the city-state, then extended to terrestrial and extra-terrestrial dimensions [

41]. Subsequently, the capitalism previously confined to the West has now overrun the globe; so, typical Western global citizenship education seems to equip learners in order to acquire the intellectual tools that would enable them to justify the

status quo and understand any act that may have global repercussions [

41]. While Western and modern global citizenship education derived its birth and sustenance from the effects of the world built over the past centuries, ancient African global citizenship education is timeless, focused on the inner values belonging to the soul of humanity; this soul is the intrinsic source of a moral foundation which perceives humanity as a brotherhood [

41]. Since Western civilization has provided an important and decisive contribution to scientific-technological advancement, globally improving living conditions (albeit with large disparities), it would be necessary to merge the scales of values for the benefit of everyone’s progress.

Other interesting considerations come from ethnographic research combined with the environmental history of western and central African countries: according to these studies, oil palms demonstrate the versatility and sustainability of local farming practices; in this area, forests have probably been advancing for the past 1,000 years despite the periods of drought, perhaps due to the “construction” of palm tree forests by local populations [

42]. This is documented, for example, by the testimonies of colonial foresters who, about a century ago, spoke with the indigenous people, who recounted the habits of their ancestors [

42]. Even today, in Southeast Asia, an NGO is trying to make agreements with palm oil growers to make this crop beneficial for nature [

43]. In addition, it must be considered that alternative vegetable oil crops could be more environmentally harmful because of the lower yield for the same land needed [

25].

Oil palms have always been significant in material culture, not just culinary; they shape not only the environment but also history, nowadays through labor rights violations [

44,

45].

Therefore, palm tree plantations could be sustainable as long as all aspects of sustainability are considered [

46]. That implies critical thinking skills in consumers, especially from Western countries [

47], also in light of the fact that sustainable palm oil is still far from having a truly incisive impact [

48].

10. Conclusion

The sequence described was qualitatively evaluated based on the students’ considerations, their degree of participation and their attention to the proposed contents.

While carrying out activities obviously aimed at student learning, the teaching dimension was emphasized in the sense indicated by Gert Biesta [

49]: the establishment of a dialogic and trusting relationship within the classes allowed for a relaxed and collaborative climate, where it was not important to demonstrate that you had learned more knowledge than others through verification tests. The teacher chose to aim at developing authentic interest, so as to solicit non-simplistic ethical considerations; in this way it is possible to attempt a Global Citizenship Education as a transition towards complexity, an unavoidable topic in teacher training today [

50].

During the first part, characterized by experimental work, stoichiometric calculations and multidisciplinary connections closely connected to chemical contents, the students deduced that the damage caused by palm tree plantations essentially concerns biodiversity and human rights; they also declared that they did not have sufficient elements to assume particular dangers to human health (health dangers appear comparable to those caused by animal-based butter). Usually, biscuit brands do not report considerations on the natural environment, instead highlighting the presence of oils considered healthier than palm oil: perhaps this can be explained with a commercial strategy. Since palm oil plantations have the highest yield in terms of oil produced per hectare, they represent the least-worst alternative compared to other types of crops [

25]. So - the students said - perhaps highlighting the absence of palm oil responds to a boycott strategy of some food companies? In this way, everything could be traced back to a competition mechanism typical of capitalist logic.

In the second part, the Systems Thinking diagrams allowed us to further broaden our view of different types of dynamics at play. The discussions in the working groups were lively, demonstrating the students’ interest in this type of dynamic concept maps. Generating a System Thinking diagram helps to develop a global vision and better understand the underlying logic of the processes. Global Citizenship Education is based primarily on understanding interconnections, visible or hidden.

The third part produced an increased students’ awareness. Other documents were analyzed, introducing new and more complex points of view with the important contribution of humanities. At this stage, the moral sentiments likely to have emerged are based on a well-rounded vision of sustainability, not seen from an exclusively scientific perspective. In any case, the entire path described started from the examination of chemical contents and concepts of fundamental importance. Systems Thinking diagrams have been a bridge between disciplinary contents and a holistic view of reality.

Supplementary materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org, S1: Students’ worksheets.

Author contributions

Conceptualization, T.C.; methodology, T.C.; resources, T.C.; writing—original draft preparation, T.C.; writing—review and editing, P.L.G.; supervision, P.L.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

The students who designed the systems diagrams are gratefully acknowledged.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- De Vecchi, G.; Giordan, A. L’enseignement scientifique: comment faire pour que «ça marche»? Z’Editions: Nice, France, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Fourez, G.; Englebert-Lecompte, V.; Grootaers, D.; Mathy, P.; Tilman, F. Alphabétisation scientifique et technique - Essai sur les finalités de l’enseignement des sciences; De Boeck-Université: Bruxelles, Belgium, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Hewitt, P. Lessons from Lily on the Introductory Course. Phys. Today 1995, 48, 85–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandt, R. On teaching for understanding: A conversation with Howard Gardner. Educ. Leadership 1993, 50, 4–7. [Google Scholar]

- Klein, J.T.; Newell, W.H. Directions For Reform Across The Disciplines. In Handbook of the Undergraduate Curriculum: A Comprehensive Guide to Purposes, Structures, Practices, and Change; Gaff, J., Ratcliff, J. & Associates, Eds, Eds.; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, US, 1997; pp. 373–415. [Google Scholar]

- Mathison, S.; Freeman, M. The Logic of Interdisciplinary Studies. In Proceedings of the Annual Meeting of the American Educational Research Association, Chicago, US, 24-28 March 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Gentili, P.L. Designing and teaching a novel interdisciplinary course on complex systems to prepare new generations to address 21st-century challenges. J Chem Educ 2019, 96, 2704–2709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morin, E. Les sept savoirs nécessaires à l’éducation du futur; UNESCO: Paris, France, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- De Jong, O. Context-based chemical education: how to improve it? In Proceedings of the 19th ICCE, Seoul, Korea, 12-17 August 2006. http://old.iupac.org/publications/cei/vol8/0801xDeJong.pdf (accessed on 05 May 2024). [Google Scholar]

- Toadvine, T. Six myths of interdisciplinarity. Thinking Nature https://www.academia.edu/2440706/Six_Myths_of_Interdisciplinarity_2011_ (accessed on 05 May 2024).. 2011, 1, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Marques, C.A.; Marcelino, L.V.; Dias, É.; Rüntzel, P.; Souza, L.; Machado, A. Green Chemistry Teaching for Sustainability in Papers Published by the Journal of Chemical Education. Quim. Nova 2020, 43, 1510–1521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabrera, D.; Cabrera, L. Systems thinking made simple. New hope for solving wicked problems, eBook edition; Plectica: US, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Sauvé, L.; Godmaire, H. Environmental health education: A participatory holistic approach. Ecohealth 2004, 1, 35–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCrory, A.; Reiss, M.J. The Place of Ethics in Science Education: Implications for Practice, eBook edition; Bloomsbury Publishing: London-New York-Dublin: UK-US-Ireland, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- European Parliament and EU Council. Regulation (Eu) No. 1169/2011 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 25 October 2011. OJEU 2011, L. 304, 22 November 2011, 18-63. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=OJ:L:2011:304:0018:0063:en:PDF (accessed on 05 May 2024).

- Kabagambe, E.K.; Baylin, A.; Ascherio, A.; Campos, H. The Type of Oil Used for Cooking Is Associated with the Risk of Nonfatal Acute Myocardial Infarction in Costa Rica J. Nutr. 2005, 135, 2674–2679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AIRC. Available on line: https://www.airc.it/cancro/informazioni-tumori/corretta-informazione/vero-lolio-palma-contiene-composti-cancerogeni-possono-aumentare-rischio-sviluppare-un-tumore?_gl=1*1lbybir*_up*MQ..*_ga*MTQyMjQ5NDgxNC4xNzE0OTE3MzMw*_ga_LHV7BFH9WN*MTcxNDkxNzMyOS4xLjEuMTcxNDkxNzM2OS4wLjAuMA. (accessed on 05 May 2024).

- CONTAM Panel. Risks for human health related to the presence of 3- and 2-monochloropropanediol (MCPD), and their fatty acid esters, and glycidyl fatty acid esters in food. EFSA Journal 2016, 14, 4426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilbert, N. Palm-oil boom raises conservation concerns. Nature 2012, 487, 14–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agritrade. Available online: https://agritrade.cta.int/Agriculture/Commodities/Oil-crops/Growing-pressure-for-stricter-palm-oil-standards.html (accessed on 05 May 2024).

- Celestino, T.; Marchetti, F. The Chemistry of Cat Litter: Activities for High School Students to Evaluate Commercial Product’s Properties and Claims Using the Tools of Chemistry . J Chem Educ 2015, 92, 1359–1363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Celestino, T.; Lombardi, D.S. Designing and Developing High School Student Activities to Understand Chelating Action by Foam Properties, J Chem Educ 2024, 101, 1469–1479. [CrossRef]

- Yanty, N.A.M.; Marikkar, J.M.N.; Abdulkarim, S.M. Determination of types of fat ingredient in some commercial biscuit formulations Int. Food Res. J. 2014, 21, 277–282. [Google Scholar]

- Rovellini, P.; Berneri, B.; Cotti Piccinelli, E.; Piro, R.; Miano, B.; Sangiorgi, E. Determination of the palm oil addition in food. Riv. Ital. Sostanze Gr. 2019, 96, 215–222. [Google Scholar]

- BBC. Available online: https://www.bbc.co.uk/sounds/play/m000bp49 (accessed on 05 May 2024).

- Balaban, A.T.; Klein, D.J. Is chemistry ‘The Central Science’? How are different sciences related? Co-citations, reductionism, emergence, and posets. Scientometrics 2006, 69, 615–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demssie, Y.N.; Biemans, H.J.A.; Wesselink, R.; Mulder, M. Fostering students’ systems thinking competence for sustainability by using multiple real-world learning approaches. Environ. Educ. Res. 2023, 29, 261–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gentili, P.L. Why is Complexity Science valuable for reaching the goals of the UN 2030 Agenda? Rend. Fis. Acc. Lincei 2021, 32, 117–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO. Global Citizenship Education. Preparing learners for the challenges of the 21st century, eBook; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2014. https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000227729 (accessed on 05 May 2024).

- Fagan, P. La funzione adattativa della cultura sistemico-complessa ad un mondo sempre più’ complesso. Riflessioni sistemiche https://www.aiems.eu/pubblicazioni/riflessioni-sistemiche_o/rs28_o (accessed on 05 May 2024). 2022, 27, 54–66. [Google Scholar]

- 31 Ferguson, C.; Brett, P. Teacher and student interpretations of global citizenship education in international schools. Educ. Citizsh. Soc. Justice 2023, 0, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarozzi, M. ECG: dal “che cosa” al “come mi posiziono”. 4 Idealtipi di ECG. In GLOCITED - Editorial Series on Global Citizenship Education; Tarozzi, M., Ed.; Alma Mater Studiorum University: Bologna, Italy, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Bosio, E. Meta-Critical Global Citizenship Education: Towards a Pedagogical Paradigm Rooted in Critical Pedagogy and Value-pluralism. Global Comparative Education: Journal of the WCCES https://www.theworldcouncil.net/gce-vol-6-no-2-dec-2022.html (accessed on 05 May 2024). 2022, 6, 3–19. [Google Scholar]

- Elkorghli, E.A.B.; Bagley, S.S. Cognitive mapping of critical global citizenship education: Conversations with teacher educators in Norway. Prospects 2023, 53, 371–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aubrecht, K.B.; Dori, Y.J.; Holme, T.A.; Lavi, R.; Matlin, S.A.; Orgill, M.; Skaza-Acosta, H. Graphical Tools for Conceptualizing Systems Thinking in Chemistry Education. J. Chem. Educ. 2019, 96, 2888–2900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeyer, A. Scientific Holism: A Synoptic (“Two-Eyed Seeing”) Approach to Science Transfer in Education for Sustainable Development, Tested with Pre-Service Teachers. Sustainability 2024, 16, 2279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernard, L. Red Palm Oil Love: A Novel, eBook; Lionel Bernard, 2017.

- Maddy, N. The Palm Oil Stain, eBook; Nadia Maddy, 2012.

- Chatelaine. Available online: https://chatelaine.com/food/red-palm-oil-memoir/ (accessed on 05 May 2024).

- Li, T.M.; Semedi, P. Plantation Life: Corporate Occupation in Indonesia’s Oil Palm Zone. Duke University Press: Durham and London, UK, 2021.

- Biao, I. African values as natural drivers of global citizenship. J. Adult Contin. Educ. 2024, 0, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robins, J.E. Oil Palm: A Global History; The University of North Carolina Press: Chapel Hill, US, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- BBC. Available online: https://www.bbc.co.uk/sounds/play/w3ct4xzm (accessed on 05 May 2024).

- Mei, L.; Newing, H.; Smith, O.A.; Colchester, M.; McInnesn, A. Identifying the Human Rights Impacts of Palm Oil: Guidance for Financial Institutions and Downstream Companies; Forest Peoples Programme: Moreton-in-Marsh, UK, 2022. https://globalcanopy.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/FPP-Palm-Oil-Report-FINAL52.pdf (accessed on 05 May 2024).

- Muttaqien, W.; Ramdlaningrum, H.; Aidha, C.N.; Armintasari, F.; Ningrum, D.R. Labour Rights Violation in Palm Oil Plantation: Case Study in West Kalimantan and Central Sulawesi; Perkumpulan PRAKARSA: Jakarta, Indonesia, 2021. https://repository.theprakarsa.org/media/publications/352627-labour-rights-violation-in-palm-oil-plan-26dbd9c7.pdf (accessed on 05 May 2024).

- Rosner, H. Palm oil is unavoidable. Can it be sustainable? Nat. Geo. 2018, 12. https://www.nationalgeographic.com/magazine/article/palm-oil-products-borneo-africa-environment-impact (accessed on 05 May 2024).

- Vergura, D.T.; Zerbini, C.; Luceri, B. ““Palm oil free” vs “sustainable palm oil”: the impact of claims on consumer perception”. Br. Food J. 2019, 121, 2027–2035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mongabay. Available online: https://news.mongabay.com/2023/12/as-rspo-celebrates-20-years-of-work-indigenous-groups-lament-unresolved-grievances/ (accessed on 05 May 2024).

- Biesta, G. Against learning. Reclaiming a language for education in an age of learning. Nordisk Pedagogik https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/17044413.pdf (accessed on 05 May 2024).. 2005, 25, 54–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerrato, M. La educación para la ciudadanía global como transición hacia la complejidad. Pensamiento sistémico y competencias transformadoras en la formación del profesorado. Aula 2024, 30, 51–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).