Submitted:

23 March 2025

Posted:

24 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

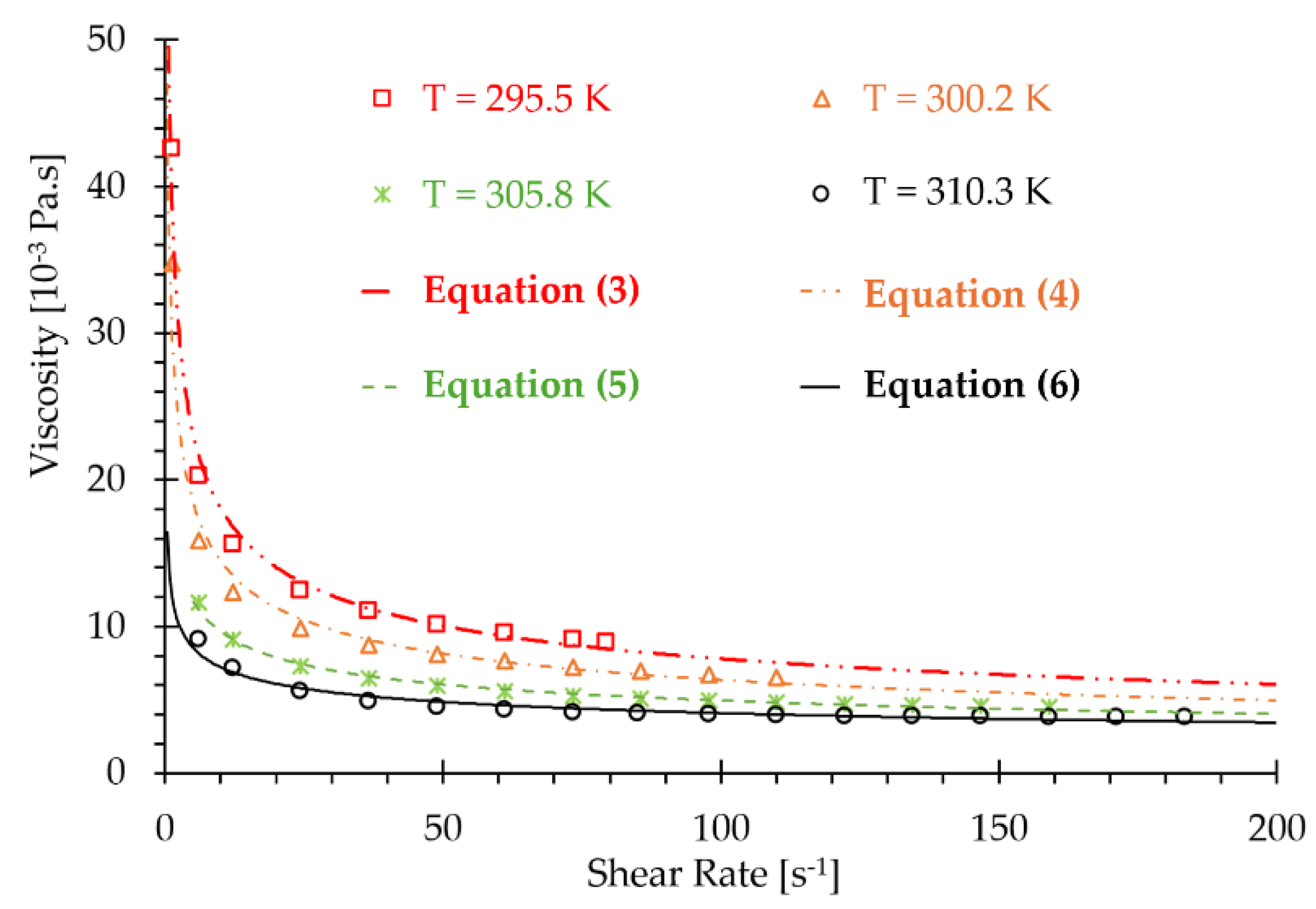

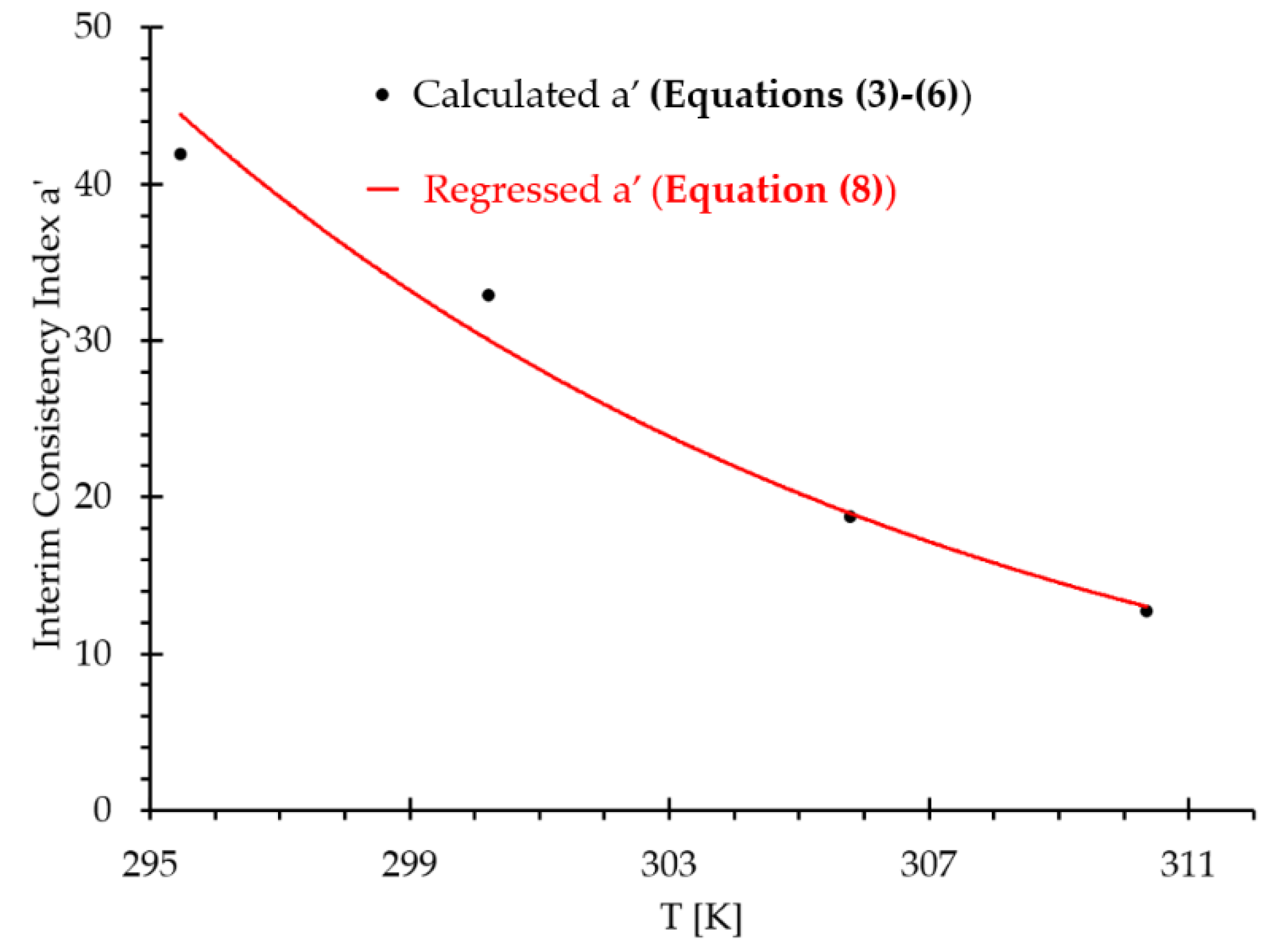

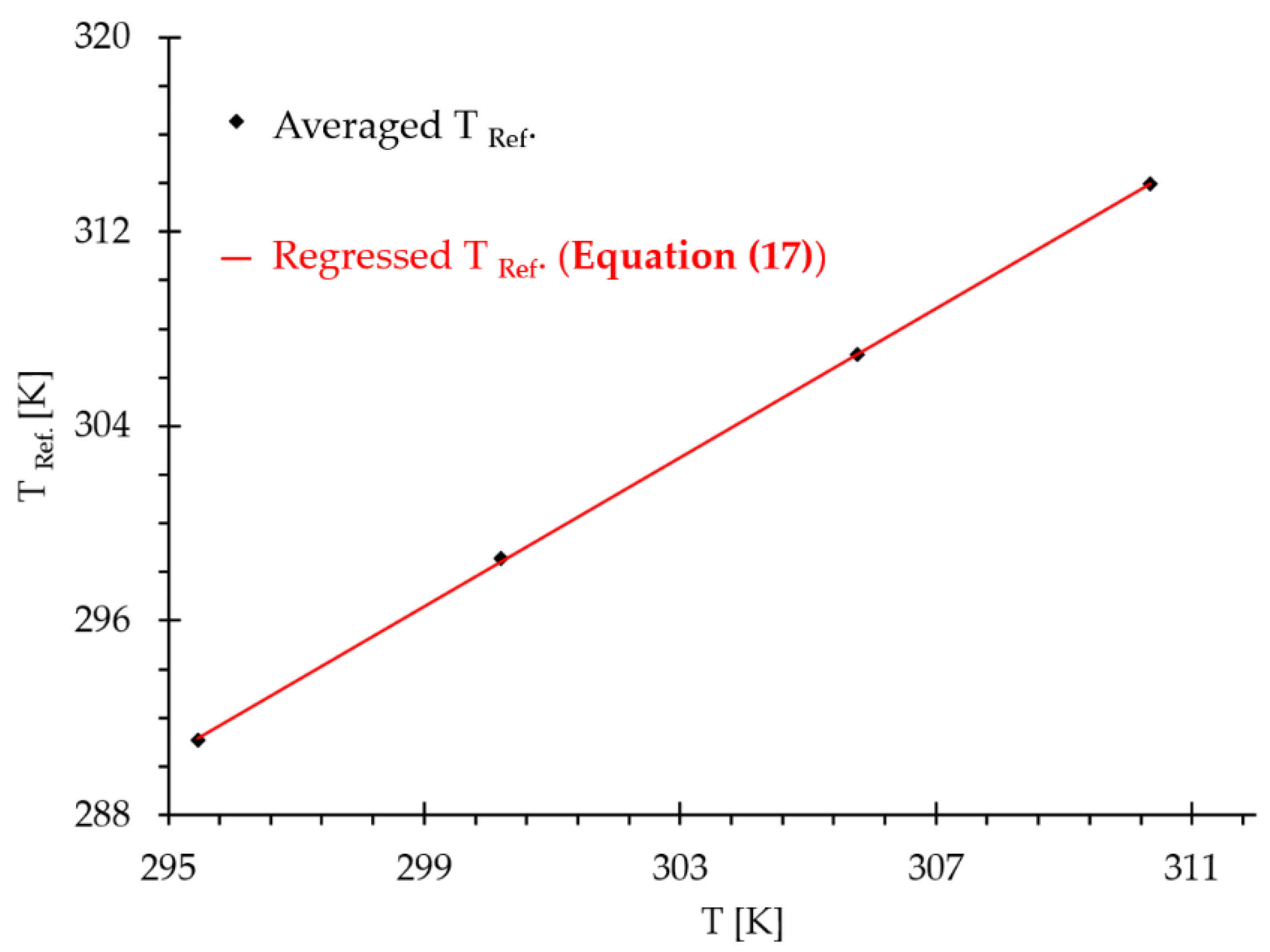

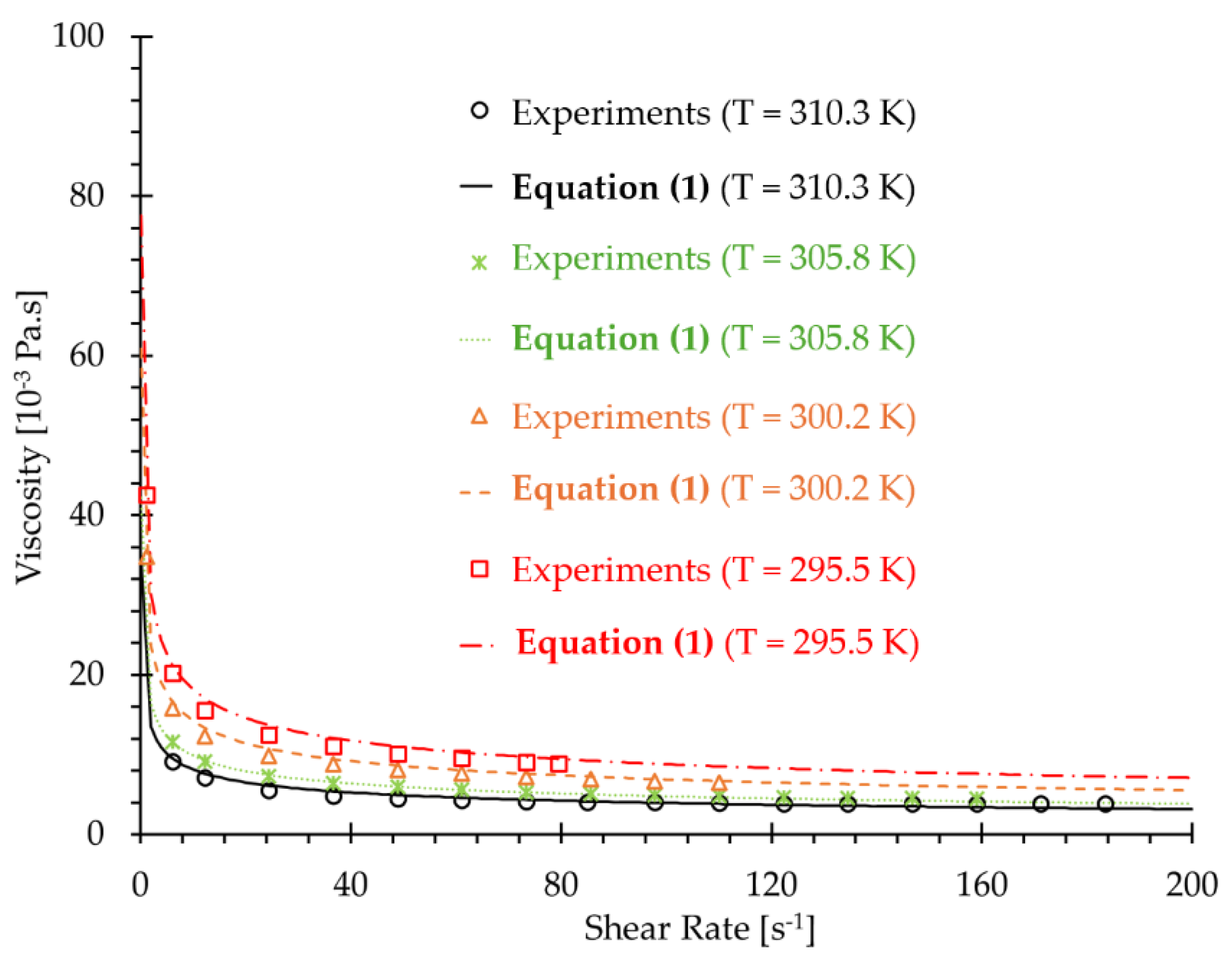

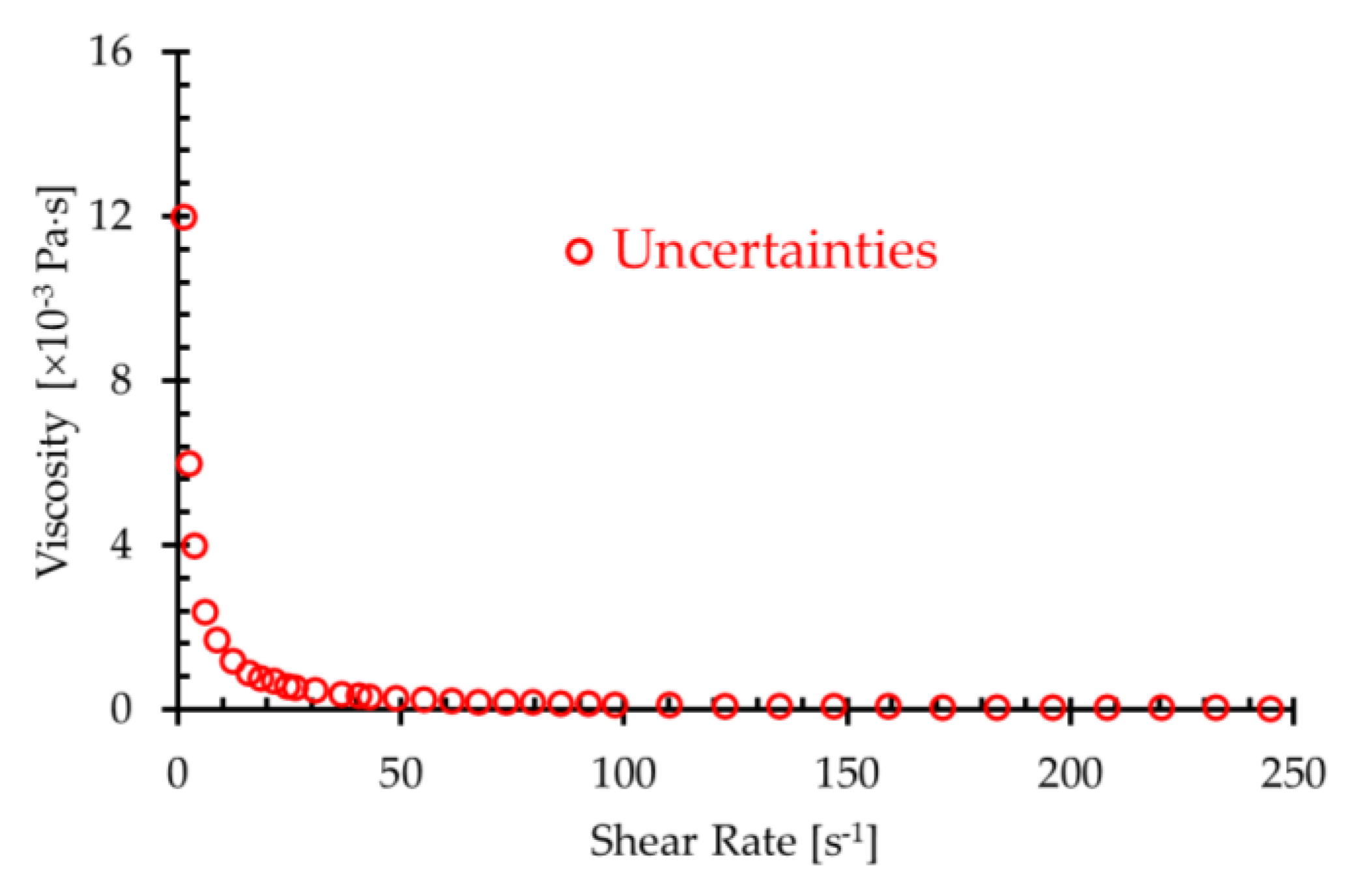

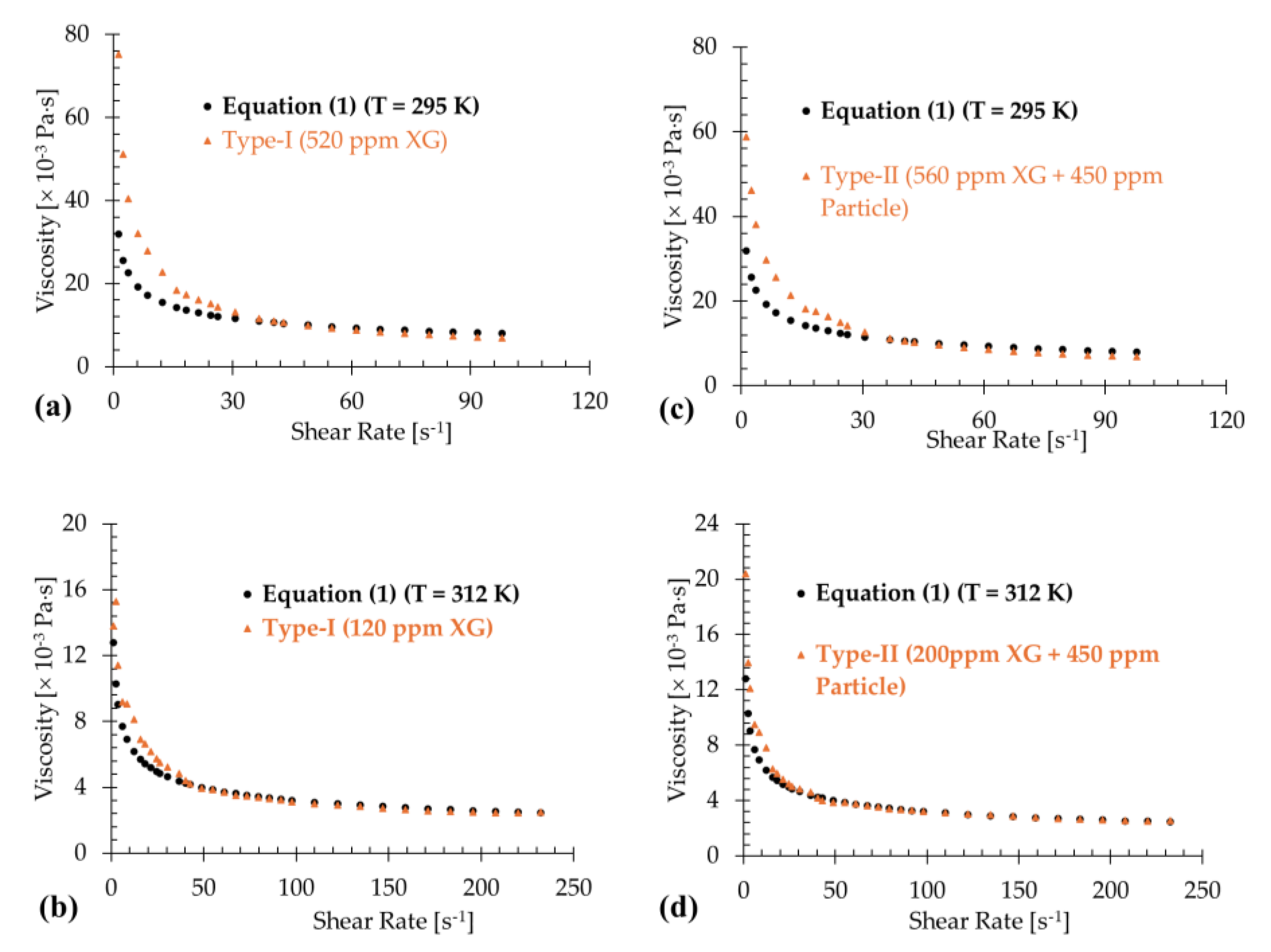

2.1. Developing a Shear-Rate and Temperatur-Dependent non-Newtonian Blood Viscosity Model

2.2. Blood Analog Generation

2.2.1. Materials

2.2.2. Experimental Setups and Measurements

3. Results

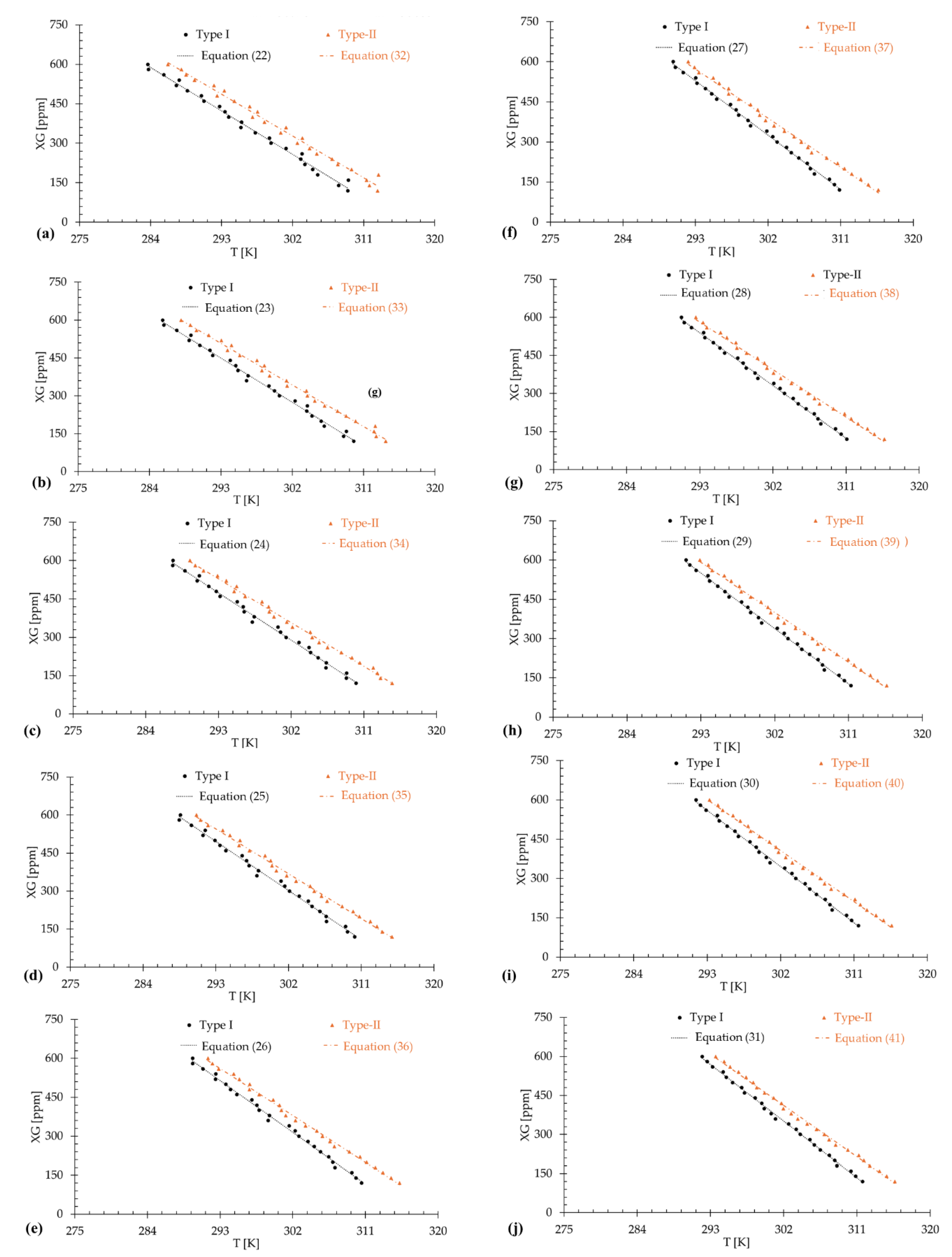

3.1. Type-I Blood Analog

3.2. Type-II Blood Analog

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| DI | Deionized |

| FRPM | Fluorescent red polyethylene microspheres |

| PIV | Particle image velocimetry |

| RCB | Red blood cell |

| RMSD | Root mean square deviation |

| XG | Xanthan gum |

References

- Merrill, E.W.; Cokelet, G.C.; Britten, A.; Wells, R.E. Non-Newtonian Rheology of Human Blood - Effect of Fibrinogen Deduced by "Subtraction". Circulation Research 1963, 13, 48–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nader, E.; Skinner, S.; Romana, M.; Fort, R.; Lemonne, N.; Guillot, N.; Gauthier, A.; Antoine-Jonville, S.; Renoux, C.; Hardy-Dessources, M.-D.; et al. Blood Rheology: Key Parameters, Impact on Blood Flow, Role in Sickle Cell Disease and Effects of Exercise. Frontiers in Physiology 2019, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynch, S.; Nama, N.; Figueroa, C.A. Effects of non-Newtonian viscosity on arterial and venous flow and transport. Sci Rep 2022, 12, 20568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, H.; Yang, Z.; Johnson, M.; Bramlage, L.; Ludwig, B. Hemodynamic characteristics in a cerebral aneurysm model using non-Newtonian blood analogues. Physics of Fluids 2022, 34, 103101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walker, A.; Johnston, C.; Rival, D. On the Characterization of a Non-Newtonian Blood Analog and Its Response to Pulsatile Flow Downstream of a Simplified Stenosis. Ann Biomed Eng 2013, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalke, B.R.; Mantini, E.L.; Kaster, R.L.; Carlson, R.G.; Lillehei, C.W. Hemodynamic features of a double-leaflet prosthetic heart valve of new design. ASAIO Journal 1967, 13, 105–110. [Google Scholar]

- Ling, S.C.; Atabek, H.B.; Fry, D.L.; Patel, D.J.; Janicki, J.S. Application of Heated-Film Velocity and Shear Probes to Hemodynamic Studies. Circulation Research 1968, 23, 789–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldwin, J.T.; Deutsch, S.; Geselowitz, D.B.; Tarbell, J.M. LDA Measurements of Mean Velocity and Reynolds Stress Fields Within an Artificial Heart Ventricle. Journal of Biomechanical Engineering 1994, 116, 190–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kempainen, R.R.; Brunette, D.D. The evaluation and management of accidental hypothermia. Respir Care 2004, 49, 192–205. [Google Scholar]

- Lell, B.; Brandts, C.H.; Graninger, W.; Kremsner, P.G. The circadian rhythm of body temperature is preserved during malarial fever. Wien Klin Wochenschr 2000, 112, 1014–1015. [Google Scholar]

- Bouchama, A.; Knochel, J.P. Heat Stroke. New England Journal of Medicine 2002, 346, 1978–1988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarkar, M.; Prabhu, V. Basics of cardiopulmonary bypass. Indian J Anaesth 2017, 61, 760–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaiswal, A.N.; Vagga, A. Cryopreservation: A Review Article. Cureus 2022, 14, e31564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, Y.; Jung, S.L. Efficacy and Safety of Thermal Ablation Techniques for the Treatment of Primary Papillary Thyroid Microcarcinoma: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Thyroid 2020, 30, 720–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, A.M.; Johnston, C.R.; Rival, D.E. On the Characterization of a Non-Newtonian Blood Analog and Its Response to Pulsatile Flow Downstream of a Simplified Stenosis. Ann Biomed Eng 2014, 42, 97–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Najjari, M.R.; Hinke, J.A.; Bulusu, K.V.; Plesniak, M.W. On the rheology of refractive-index-matched, non-Newtonian blood-analog fluids for PIV experiments. Experiments in Fluids 2016, 57, 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yousif, M.Y.; Holdsworth, D.W.; Poepping, T.L. A blood-mimicking fluid for particle image velocimetry with silicone vascular models. Experiments in Fluids 2011, 50, 769–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, K.; Katz, J. On the refractive index of sodium iodide solutions for index matching in PIV. Experiments in Fluids 2014, 55, 1704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brookshier, K.A.; Tarbell, J.M. Evaluation of a transparent blood analog fluid: Aqueous Xanthan gum/glycerin. Biorheology 1993, 30, 107–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephanova, D.I.; Kossev, A. Theoretical predication of temperature effects at 20 C-42 o C on adaptive processes in simulated amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. JIN 2018, 17, 355–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mann, D.E.; Tarbell, J.M. Flow of non-Newtonian blood analog fluids in rigid curved and straight artery models. Biorheology 1990, 27, 711–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naiki, T. Evaluation of High Polymer Solutions as Blood Analog Fluid-For the Model Study of Hemodynamics. J. Jpn. Soc. Biorheol. 1995, 9, 84–89. [Google Scholar]

- Yi, H.; Yang, Z.; Johnson, M.; Bramlage, L.; Ludwig, B. Erratum: “Hemodynamic characteristics in a cerebral aneurysm model using non-Newtonian blood analogues” [Phys. Fluids 34, 103101 (2022)]. Physics of Fluids 2023, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kannojiya, V.; Das, A.K.; Das, P.K. Simulation of Blood as Fluid: A Review From Rheological Aspects. IEEE Rev Biomed Eng 2021, 14, 327–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutmann, F.; Simmons, L.M. The Temperature Dependence of the Viscosity of Liquids. Journal of Applied Physics 1952, 23, 977–978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tajima, Y.A.; Crozier, D.G. Chemorheology of an amine-cured epoxy resin. Polymer Engineering & Science 1986, 26, 427–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roller, M.B. Rheology of curing thermosets: A review. Polymer Engineering & Science 1986, 26, 432–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanner, R.I. Engineering rheology; OUP Oxford: 2000; Volume 52.

- Szabo, F.E. M. The Linear Algebra Survival Guide, Szabo, F.E., Ed.; Academic Press: Boston, 2015; pp. 219–233. [Google Scholar]

- Kibble, J.D. The big picture physiology : medical course & step 1 review, 2nd ed.; McGraw-Hill: New York, N.Y, 2020. [Google Scholar]

| 6.11 | 12.22 | 24.45 | 36.68 | 48.91 | 61.15 | 73.37 | |

| 5078.0695 | 5076.4238 | 5642.7484 | 5753.1148 | 5735.2348 | 5484.2840 | 4880.5709 | |

| 5075.0346 | 5001.5716 | 5275.4079 | 5372.0900 | 5392.6819 | 5288.4887 | 5083.2582 | |

| 4914.6750 | 4815.3147 | 4961.1219 | 5035.4353 | 5004.6332 | 4936.2186 | 4811.9285 | |

| 5072.6236 | 4942.1073 | 4983.5841 | 5069.3949 | 5120.5499 | 5132.9445 | 5244.2778 | |

| 4845.6259 | 4704.9722 | 4673.0723 | 4732.1500 | 4695.8871 | 4704.6106 | 4782.9208 | |

| 4587.6398 | 4435.4649 | 4320.1714 | 4348.8666 | 4213.2520 | 4217.8034 | 4258.5822 | |

| [] | |||||||

| 6.11 | 12.22 | 24.45 | 36.68 | 48.91 | 61.15 | 73.37 | |

| [] | |||||||

| 295 .5 | 295.70.1 | 295 .5 | 295.70.1 | 295 .5 | 295.70.1 | 295 .5 | 295.70.1 |

| 300.2 | 298.847 | 300.2 | 298.847 | 300.2 | 298.847 | 300.2 | 298.847 |

| 305.8 | 307.289 | 305.8 | 307.289 | 305.8 | 307.289 | 305.8 | 307.289 |

| 310.3 | 314.587 | 310.3 | 314.587 | 310.3 | 314.587 | 310.3 | 314.587 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).