1. Introduction

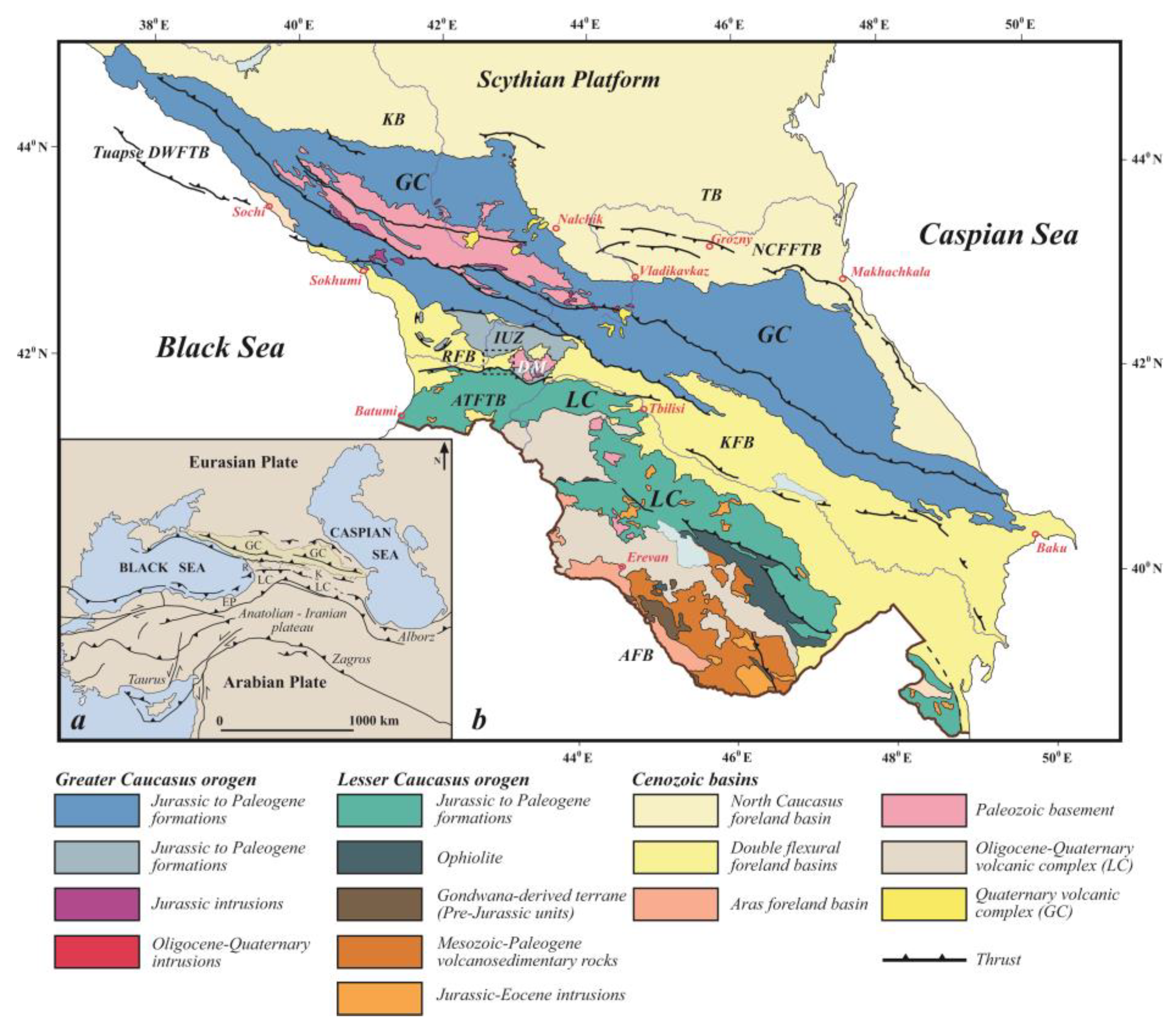

The Rioni foreland basin (RFB) in western Georgia is located between the Greater Caucasus (GC) and Lesser Caucasus (LC) orogens, situated in the far-field zone of the Arabia-Eurasia collision zone-e.g., [

1,

2] (

Figure 1a). During the Late Cenozoic time, the ongoing Arabia-Eurasia continental collision resulted in the formation of two orogens, the LC and the GC, and the development of a foreland basin between them [

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8] (

Figure 1b).

In western Georgia, the Dzirula Massif (DM) breaks a contiguous collisional foreland basin into disconnected basins, the Rioni basin to the west and the Kura basin to the east (

Figure 1b). Several structural studies have illustrated the thin-skinned tectonic styles of the Rioni and Kura basins, which were controlled by the action of two opposing orogenic fronts, the LC retro-wedge to the south and the GC pro-wedge to the north [

1,

3,

10]. During the last several years the understanding of the structure of the RFB has been the focus mainly in the western part of studies-e.g., [

1,

8,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15]. Unlike the western part, the eastern RFB (

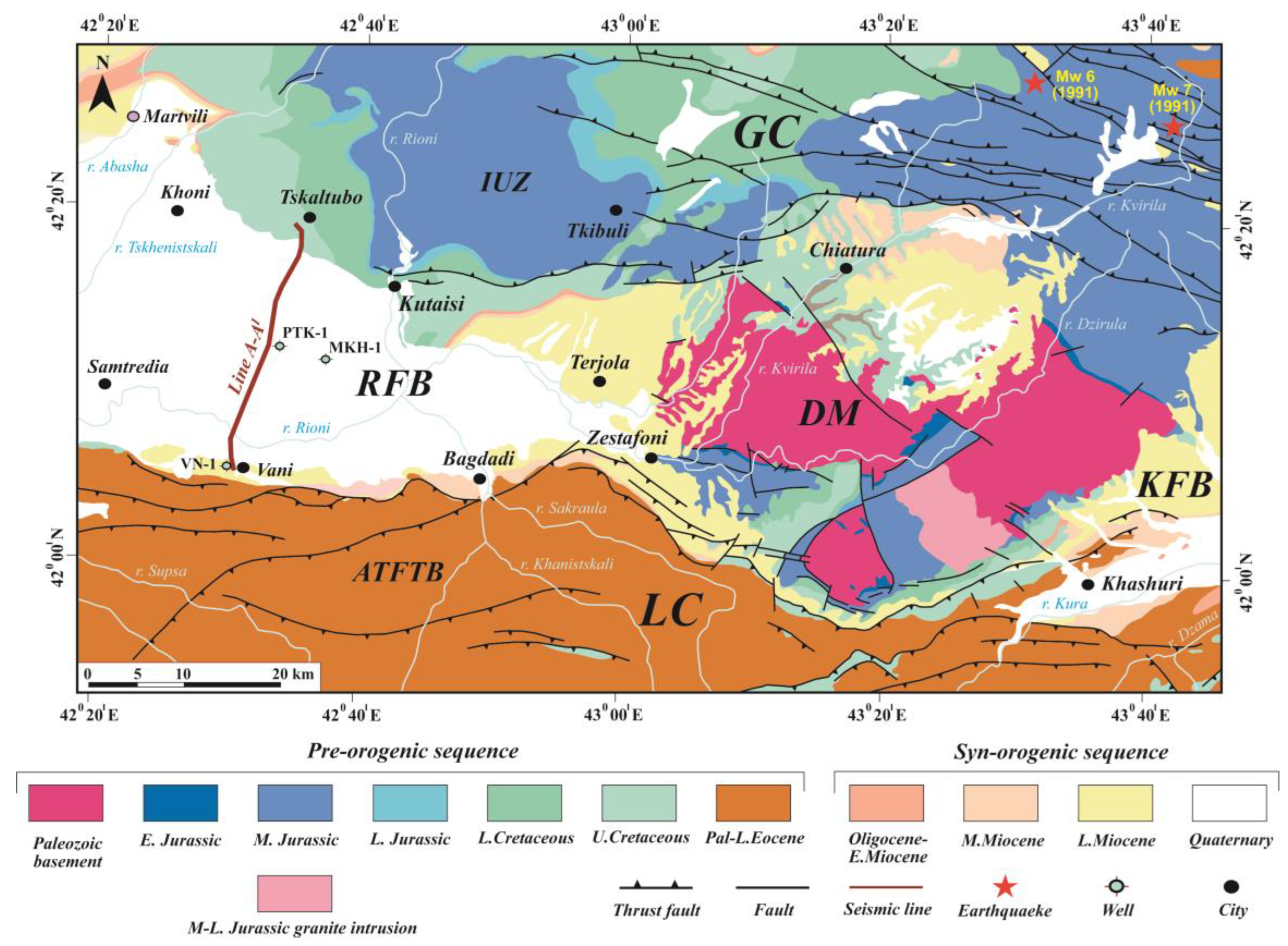

Figure 2) and its deep structure and structural relationship to the DM are still enigmatic.

In this study, we present new subsurface constraints using a seismic profile combined with the field geologic observations and deep-borehole information that define the basement geometry and deformation structural style of the eastern RFB. This study documents the controls exerted by preexisting basement structures on the eastern Rioni basin geometry during the Late Cenozoic deformation.

2. Geological Setting

Foreland basin sediment deposition in the RFB is regarded to have started during the Oligocene to Early Miocene, consistent with the onset of rapid subsidence from the south by the LC and from the north by the GC orogens [

1,

10]. The RFB narrows to the east and is separated from the Kura foreland basin (KFB) by the DM (

Figure 2). The RFB sedimentary infill (more than 4-5 km) consists of pre- and syn-orogenic sequences. The pre-Mesozoic basement of the RFB exposed in the DM (

Figure 1b,

Figure 2) comprises Hercynian granitic metamorphic rocks in its core, overlain by Devonian to Carboniferous phyllites-e.g., [

21]. Most of the pre-Mesozoic basement is intruded by middle-late Jurassic granitoid [

16]. The RFB stratigraphy reflects the evolution from the extensional basin to the RFB of the Arabia-Eurasia collision zone [

1] and is summarized in a tectonostratigraphic chart (see

Figure S1 of the

Supplementary Materials).

The pre-orogenic sequences consist of Jurassic-Late Eocene shallow- and deep-marine sedimentary strata-e.g., [

13,

20,

21]. The Early Jurassic sandstones and shales (about 1500 m thick) are exposed to the north and south of the RFB. Middle Jurassic rocks strata are represented by Bajocian debris flow deposits, sandstones, shales, and turbidities with rare intercalations of calk-alkaline andesite-basalts and the Bathonian freshwater-lacustrine coal-bearing sandy-argillaceous rocks. The Late Jurassic succession is represented by evaporites, clastic rocks, and basalts. Early Cretaceous turbidities, dolomites, limestones, and marls, with conglomerates at the base, transgressively rest on Late Jurassic rocks [

20,

21]. The Late Aptian, Albian, and Cenomanian sequence is dominated by siliciclastic rocks. Late Cretaceous, Paleocene, and Eocene deposits mainly consist of mixed carbonate-siliciclastic-volcaniclastic rocks; their thickness in some places exceeds 2000 m [

21].

The syn-orogenic sequences are composed of the foreland basin (Oligocene-Early Miocene) and syn-tectonic strata [

1]. The Oligocene-Neogene stratigraphy of the RFB is dominated by siliciclastic sequences [

11,

13]. The Oligocene-Early Miocene is represented mainly by the alternation of shales and sandstones and is underlain unconformably by the marl-dominated Eocene sequence [

13]. Middle-Late Miocene, Pliocene, and Pleistocene syn-tectonic strata are represented by shallow marine and continental, predominantly siliciclastic sedimentary rocks. The thickness of the syn-tectonic strata is about 1500-2000 m-e.g., [

1,

12].

During the middle Miocene – Pleistocene the RFB underwent shortening in two directions: S- to N-directed and N- to S-directed shortening [

10,

12,

13]. The main style of deformation within the western part of the RFB is a set of growth fault-propagation folds, triangle zones, duplexes, and a series of thrust-top basins-e.g., [

1]. The RFB is characterized by two major detachment levels. Fault-propagation folds above the upper detachment level can develop by piggyback and break-back thrust sequences in the Late Jurassic evaporites. Duplex structures above the lower detachment can develop by piggyback thrust sequences in the Early Jurassic shales [

1].

Recent GPS and earthquake data indicate that the RFB is still tectonically active [

22,

23,

24]. Earthquake focal mechanisms within western RFB show primarily thrust and reverse faulting, e.g. [

22,

24]. North-East of the RFB is located Racha 1991 (Mw 7) earthquake epicentral area (

Figure 2).

3. Data and Methods

The surface geological information was obtained from a 1:200,000 geological map of the study area [

16] (

Figure 2). To constrain the subsurface structure of the eastern RFB, we used a post-stack depth migrated (PSDM) seismic profile (A-A

I) and deep borehole data. The seismic profile (A-A

I) is nearly perpendicular to the main structures of the eastern Rioni foreland basin and has a total length of 26.7 km. (

Figure 2). We employed contractional fault-related folding and structural wedges theories-e.g., [

25,

26] to interpret the geometries of fault-related folds and wedges imaged in the seismic profile (see

Figure S2 of the

Supplementary Materials). These theories describe the geometric and kinematic evolution of structures in fold-and-thrust belts-e.g., [

25,

26]. The structural interpretation of a seismic profile was performed using the Move software.

4. Results and Discussion

Seismic reflection data (A-A

I) were acquired along a transect across the eastern RFB in western Georgia and provided information on the structural architecture down to 7 km depth (

Figure 3a, b). The seismic profile, integrated with deep-borehole data and surface geology information, has allowed us to define the structural architecture of eastern RFB. The seismic profile (

Figure 3a, b) illustrates that the sedimentary cover of the eastern RFB comprises an extensional basin succession (Jurassic to Cretaceous). This basin sequence is unconformity overlain by the middle-late Miocene growth strata.

Using seismic reflection data, we have identified five populations of tectonic structures in the eastern RFB: (1) normal faults, (2) reverse faults, (3) thrust faults, (4) duplexes, and (5) crustal-scale duplexes (

Figure 3a, b). The seismic profile reflects that the compressional deformations were controlled by the multi-level differential detachments. The shallow-level detachment developed between the Cretaceous and middle Miocene strata and is represented by north-vergent thrust. The medium-level detachment in the lower Jurassic develops imbricate thrust faults and reverse faults. The deep-level detachment in the basement develops the duplex.

The seismic profile (A-A

I) reveals the occurrence of normal faults within the pre-orogenic sedimentary strata (

Figure 2a, b). These faults are inherited from the Middle Jurassic-Cretaceous and are related to the syn-rift phase of extension-e.g., [

1,

27]. The seismic profile indicates that most normal faults are re-activated during compressional deformation and are represented by reverse faults (

Figure 3a, b). Thick-skinned structures comprise fault-bend folds moving into the sedimentary cover, mainly along lower Jurassic shales, which form crustal-scale duplexes that transfer the deformation to the south. Preexisting, basement-involved extensional faults inverted during compressive deformation produced basement-cored uplifts that transferred thick-skinned shortening southward onto the thin-skinned structures detached above the basement. The maximum uplift of the Paleozoic basement is located in the central and northern parts of the seismic profile where the upper part of the Cretaceous is eroded and overlain by middle-late Miocene growth strata. The age of the growth strata from the seismic profile suggests that the initiation of thrusting in the eastern RFB began in the Middle Miocene. These data are consistent with the results of detrital apatite fission-track data conducted in the KFB [

7,

8].

4.1. Main Problems Addressed in This Study

The interpretation of the seismic profile (

Figure 3a, b) was the key to identifying the deformation structural style of the eastern RFB and the surrounding area. The proposed model provides a basis for discussing the evidence for whether these duplexes are a western subsurface continuation of the DM. The structural models of the eastern RFB and the DM have been oversimplified in previous models.

Several authors have discussed tectonic models of the DM. Nevertheless, the structural style and uplift mechanisms of the DM in western Georgia are still a matter of debate. Until recently, three competing hypotheses existed about the uplift mechanisms and tectonic setting. The first hypothesis proposes that the DM is an autochthonous basement block submerged to the west under the RFB and to the south under the KFB-e.g., [

3,

10,

14,

17,

18]. The second hypothesis assumes that the uplift of the DM is linked to the deep-seated transverse faults-e.g., [

28]. The third hypothesis proposes that DM is a structural wedge formed in late Alpine times [

19].

The seismic reflection profile (

Figure 3a, b) shows that the uplift of the Paleozoic basement in the frontal part of the GC pro-wedge is caused by crustal-scale duplex stacking. In this work, according to our preliminary data, we suggest that the crustal-scale duplex stacking during the middle Miocene-Pliocene times was the main factor in generating two disconnected basins, the Rioni basin in the west and the Kura basin in the south. It is known that foreland basins are divided into two end-member styles [

29,

30]: (i) continuous foreland basins with thin-skin deformation and, (ii) conversely, broken foreland basins are characterized by thick-skin deformation. According to Horton et al. [

31], the basement structural inheritance of normal faults in break foreland basins is a main parameter that affects the geometry and kinematics of crustal-scale duplexes or structural wedges during compressional deformation. Using end-member styles of foreland basins [

29,

30,

31], our preliminary work illustrates that a collisional foreland basin which is located between the LC and the GC orogens and is divided by the DM into the Rioni and Kura basins, is a typical broken foreland basin. Like other broken foreland basins-e.g., [

31], the segmentation of the collisional foreland basin into the Rioni basin to the west and the Kura basin to the south by the DM within the LC-GC convergence zone may be linked commonly to flat-slab continental subduction.

Compared to previously published models, our new structural model provides a better understanding of the deep structure of the eastern RFB. Our results also highlight specific needs for better seismic hazard assessment in this region. This work, based on seismic reflection profile interpretation of thrust systems offers new perspectives for future studies of the DM. Given their structural position in the frontal part of the GC pro-wedge, that recorded crustal-scale duplex stacking offers the opportunity to study the geometry of the LC-GC orogens collision zone.

5. Conclusions

We documented the subsurface structural geology in the eastern RFB, western Georgia. From the SSW to the NNE, the seismic reflection profile (A-AI) shows: (1) thin-skinned thrust fault structures, and (2) basement-involved duplexes or thick-skinned fault-bend fold structural wedges. The formation of crustal-scale duplexes in the eastern RFB is related to the reactivation of pre-existing normal faults during compressive deformation. Our work suggests that the crustal-scale duplex revealed in the seismic profile is a western prolongation of the DM and the uplift of this crystalline massif in the frontal part of the GC pro-wedge was caused by crustal-scale fault-bend fold structural wedges (or duplexes) stacking, exhumed as part of a broken foreland basin.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, V.A.; methodology, V.A., O.E., and A.R.; software, C.C., O.E., and A.R.; validation, V.A., O.E., N.K., T.B., R.C., A.G., G.M., and A.R.; formal analysis, V.A., O.E., N.K., and T.B.; investigation, V.A., O.E., N.K., and T.B.; resources, V.A.; data collection, A.R.; data curation, V.A., O.E., N.K., and T.B..; writing—original draft preparation, V.A., O.E., N.K., and T.B.; writing—review and editing, V.A., O.E., N.K., T.B., R.C., A.G., G.M., and A.R.; supervision, V.A.; project administration, V.A., O.E., and N.K.; funding acquisition, V.A., O.E., N.K., and T.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The work was supported by the Shota Rustaveli National Science Foundation of Georgia (FR-21-26377).

Acknowledgments

We are very grateful to the Georgian State Agency of Oil and Gas for providing the seismic profile for our interpretation.

References

- Alania, V.; Melikadze, G.; Pace, P.; Fórizs, I.; Beridze, T.; Enukidze, O.; Giorgadze, A.; Razmadze, A. Deformation structural style of the Rioni foreland fold-and-thrust belt, western Greater Caucasus: Insight from the balanced cross-section. Frontiers in Earth Science 2022, 10968386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavazza, W.; Gusmeo, T.; Zattin, M.; Alania, V.; Enukidze, O.; Corrado, S.; Schito, A. Two-step exhumation of Caucasian intraplate rifts: a proxy of sequential plate-margin collisional orogenies. Geoscience Frontiers 2024, 15, 101737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nemcok, M.; Glonti, B.; Yukler, A.; Marton, B. Development history of the foreland plate trapped between two converging orogens: Kura Valley, Georgia, case study. Geol. Soc. Lond. Spec. Publications 2013, 377, 159–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forte, A.M.; Cowgill, E.S.; Whipple, K.X. Transition from a singly vergent to a doubly vergent wedge in a young orogen: The Greater Caucasus. Tectonics 2014, 33, 2077–2101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alania, V.; Chabukiani, A.; Chagelishvili, R.; Enukidze, O.; Gogrichiani, K.; Razmadze, A.; Tsereteli, N. Growth structures, piggyback basins and growth strata of Georgian part of Kura foreland fold and thrust belt: implication for Late Alpine kinematic evolution. Geol. Soc. Lond. Spec. Publications 2017, 428, 171–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alania, V.; Enukidze, O.; Razmadze, A.; Beridze, T.; Merkviladze, D.; Shikhashvili, T. Interpretation and analysis of seismic and analog modeling data of triangle zone: a case study from the frontal part of western Kura foreland fold-and-thrust belt, Georgia. Frontiers in Earth Sciences 2023, 11, 1195767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gusmeo, T.; Cavazza, C.; Alania, V.; Enukidze, O.; Zattin, M.; Corrado, S. Structural inversion of back-arc basins-The Neogene Adjara-Trialeti fold-and-thrust belt (SW Georgia) as a far-field effect of the Arabia-Eurasia collision. Tectonophysics 2021, 803, 228702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gusmeo, T.; Andrea, C.; Corrado, S.; Alania, V.; Enukidze, O.; Massimiliano, Z.; Cavazza, W. Tectono-thermal evolution of central Transcaucasia: Thermal modelling, seismic interpretation, and low-temperature thermochronology of the eastern Adjara-Trialeti and western Kura sedimentary basins (Georgia). J. As. Earth Sci. 2022, 2022 238, 105355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sosson, M.; Stephenson, S.; Sheremet, Y.; Rolland, Y.; Adamia, Sh.; Melkonian, R.; Kangarli, T.; Yegorova, T.; Avagyan, A.; Galoyan, G.; Danelian, T.; Hässig, M.; Meijers, M.; Müller, C.; Sahakyan, L.; Sadradze, N.; Alania, V.; Enukidze, O.; Mosar, J. The Eastern Black Sea-Caucasus region during Cretaceous: new evidence to constrain its tectonic evolution. Compte-Rendus Geosciences 2016, 348, 23–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banks, C.J.; Robinson, A.G.; Williams, M.P. Structure and regional tectonics of the Achara-Trialet fold belt and the adjacent Rioni and Kartli foreland basins, Republic of Georgia. Am. Ass. Pet. Geol. Memoir 1997, 68, 331–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamia, Sh.; Alania, V.; Chabukiani, A.; Chichua, G.; Enukidze, O.; Sadradze, N. Evolution of the Late Cenozoic basins of Georgia (SW Caucasus): a review. Geol. Soc. Lond. Spec. Publications 2010, 340, 239–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tibaldi, A.; Alania, V.; Bonali, F.; Enukidze, O.; Tsereteli, N.; Kvavadze, N.; Varazanashvili, O. Active inversion tectonics, simple shear folding and back-thrusting at Rioni Basin, Georgia. J. Struc. Geol. 2017, 96, 35–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tari, G.; Vakhania, D.; Tatishvili, G.; Mikeladze, V.; Gogritchiani, K.; Vacharadze, S.; Mayer, J.; Sheya, C.; Siedl, W.; M. Banon, J.J.; Trigo Sanchez, J.L. Stratigraphy, structure and petroleum exploration play types of the Rioni Basin, Georgia. Geol. Soc. Lond. Spec. Publications 2018, 464, 403–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cowgill, E.; Forte, A.M.; Niemi, N.; Avdeev, B.; Tye, A.; Trexler, C.; Javaxishvili, Z.; Elashvili, M. , Godoladze, T. Relict basin closure and crustal shortening budgets during continental collision: An example from Caucasus sediment provenance. Tectonics 2016, 35, 2918–2947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trexler, C.C.; Cowgill, E.; Spencer, J.Q.G.; Godoladze, T. Rate of active shortening across the southern thrust front of the Greater Caucasus in western Georgia from kinematic modeling of folded river terraces above a listric thrust. Earth Planet Sci. Lett. 2020, 544, 116362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamia, Sh.; Sadradze, N.; Alania, V.; Talakhadze, G.; Khmaladze, K. Geology of lithosphere of the Georgia, deep structure, geodynamics and evolution; Diagrama Press: Tbilisi State University, Georgia, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Ruppel, C.; McNutt, M. Regional compensation of the Greater Caucasus mountains based on an analysis of Bouguer gravity data. Earth Planet Sci. Lett. 1990, 98, 360–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khain, V. Structure and main stages in the tectono-magmatic development of the Caucasus: an attempt at geodynamic interpretation. Am. J. Sci. 1975, 275-A, 131–156. [Google Scholar]

- Alania, V. Late Cenozoic tectonic evolution of the Georgia (SW Caucasus). In Tectonic Crossroads: Evolving Orogens of Eurasia-Africa-Arabia, GSA Meeting, Ankara, Turkey, 4-7 October 2010.

- Beridze, M. Geosynclinal sedimentary lithogenesis as exemplified by early Mesozoic formations of the Greater Caucasus; Metsniereba: Tbilisi, Georgia, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Adamia, Sh.; Alania, V.; Chabukiani, A.; Kutelia, Z.; Sadradze, N. Great Caucasus (Cavcasioni): Longliving Northtethyan Back-Arc Basin. Turk. J. Earth Sci. 2011, 20, 611–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsereteli, N.; Tibaldi, A.; Alania, V.; Gventsadse, A.; Enukidze, O.; Varazanashvili, O.; Müller, B. I. R. Active tectonics of central-western Caucasus, Georgia. Tectonophysics 2016, 691, 328–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sokhadze, G.; Floyd, M.; Godoladze, T.; King, R.; Cowgill, E.S.; Javakhishvili, Z. Active convergence between the lesser and greater Caucasus in Georgia: constraints on the tectonic evolution of the Lesser-Greater Caucasus continental collision. Earth Planet Sci. Lett. 2018, 481, 154–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tibaldi, A.; Tsereteli, N.; Varazanashvili, O.; Babayev, G.; Barth, A.; Mumladze, T.; et al. Active stress field and fault kinematics of the Greater Caucasus. J. As. Earth Sci. 2020, 188, 104108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaw, J.H.; Connors, C.D.; Suppe, J. Seismic interpretation of contractional fault-related folds; AAPG Studies in Geology 53, USA, 2005.

- Brandes, C.; Tanner, D.C. Fault-related folding: A review of kinematic models and their application. Earth-Science Reviews 2014, 138, 352–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vincent, S.J.; W. Braham, V.A.; Lavrishchev, J.R.; Maynard, Harland, M. The formation and inversion of the western Greater Caucasus Basin and the uplift of the western Greater Caucasus: Implications for the wider Black Sea region. Tectonics 2016, 35, 2948–2962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basheleishvili, L.B. Structural Associations of the Basement and Sedimentary Cover of the Georgian Part of the Caucasus. In Basement Tectonics; Sinha, A.K., Ed.; Springer: Dordrecht, 1999; pp. 25–32. [Google Scholar]

- Strecker, M.R.; Hilley, G.E.; Bookhagen, B.; Sobel, E.R. Structural, geomorphic, and depositional characteristics of contiguous and broken foreland basins: Examples from the eastern flanks of the Central Andes in Bolivia and NW Argentina. In Tectonics of sedimentary basins: Recent advances; Cathy Busby, C., Azor, A., Eds.; Blackwell Publishing: Chichester, UK, 2012; pp. 508–521. [Google Scholar]

- Horton, B.K. Sedimentary record of Andean Mountain building. Earth-Science Reviews 2018, 178, 279–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horton, B.K.; Capaldi, T.N.; Mackaman-Lofland, C.; Perez, N.D.; Bush, M.A.; Fuentes, F.; Constenius, K.N.

- Broken foreland basins and the influence of subduction dynamics, tectonic inheritance, and mechanical triggers. Earth-Science Reviews 2022, 234, 104193. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).