Submitted:

22 March 2025

Posted:

24 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

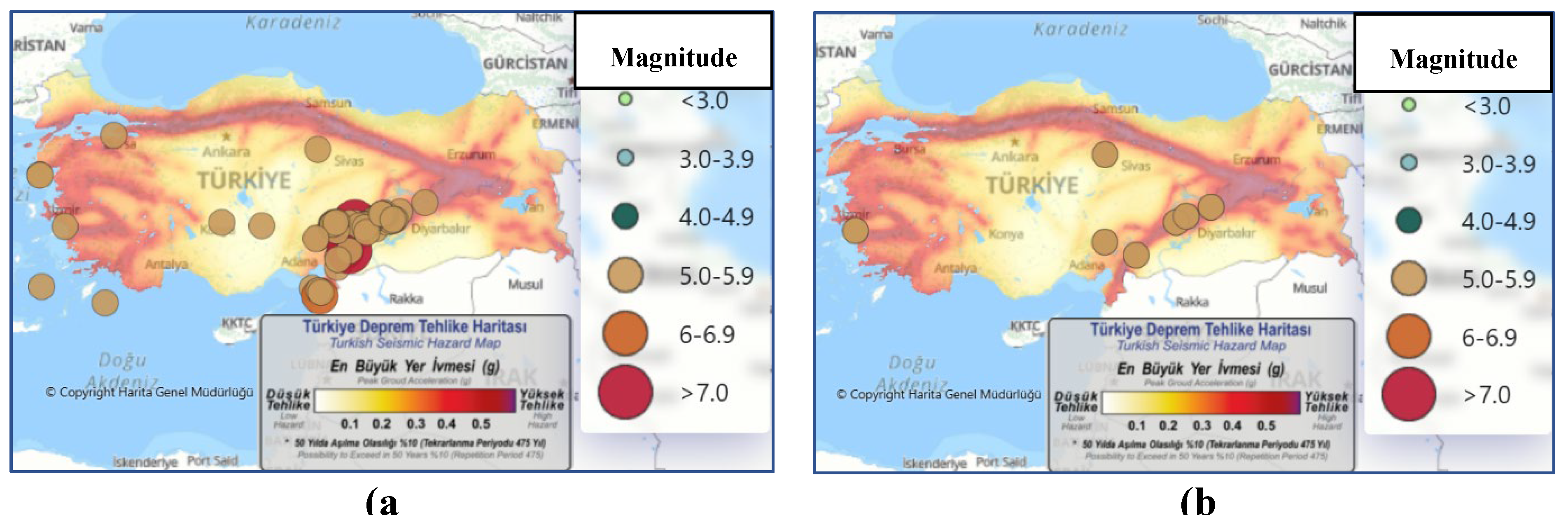

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

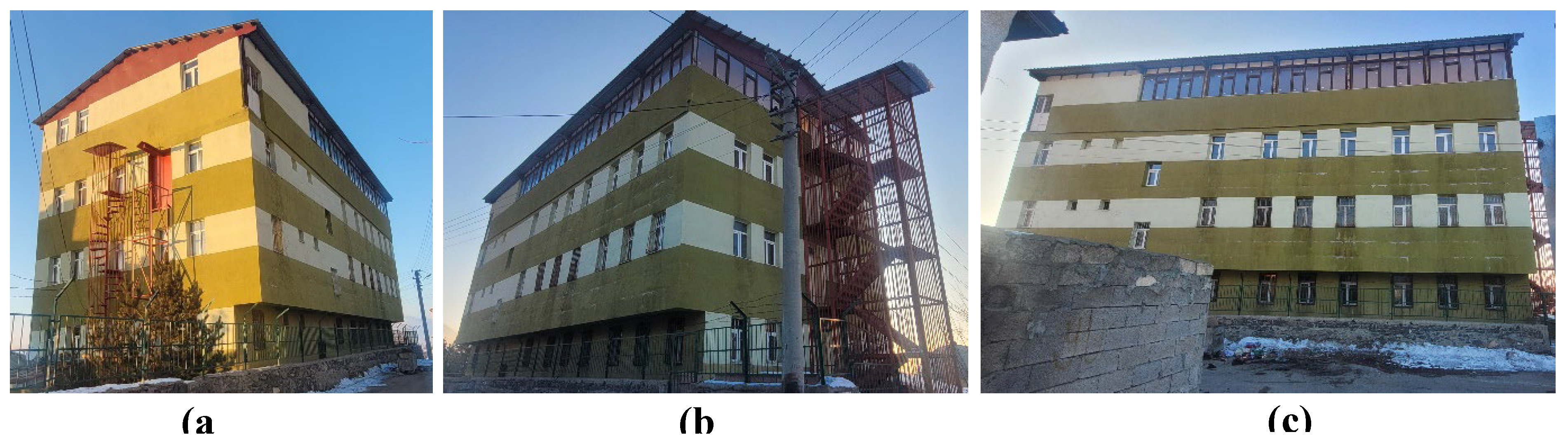

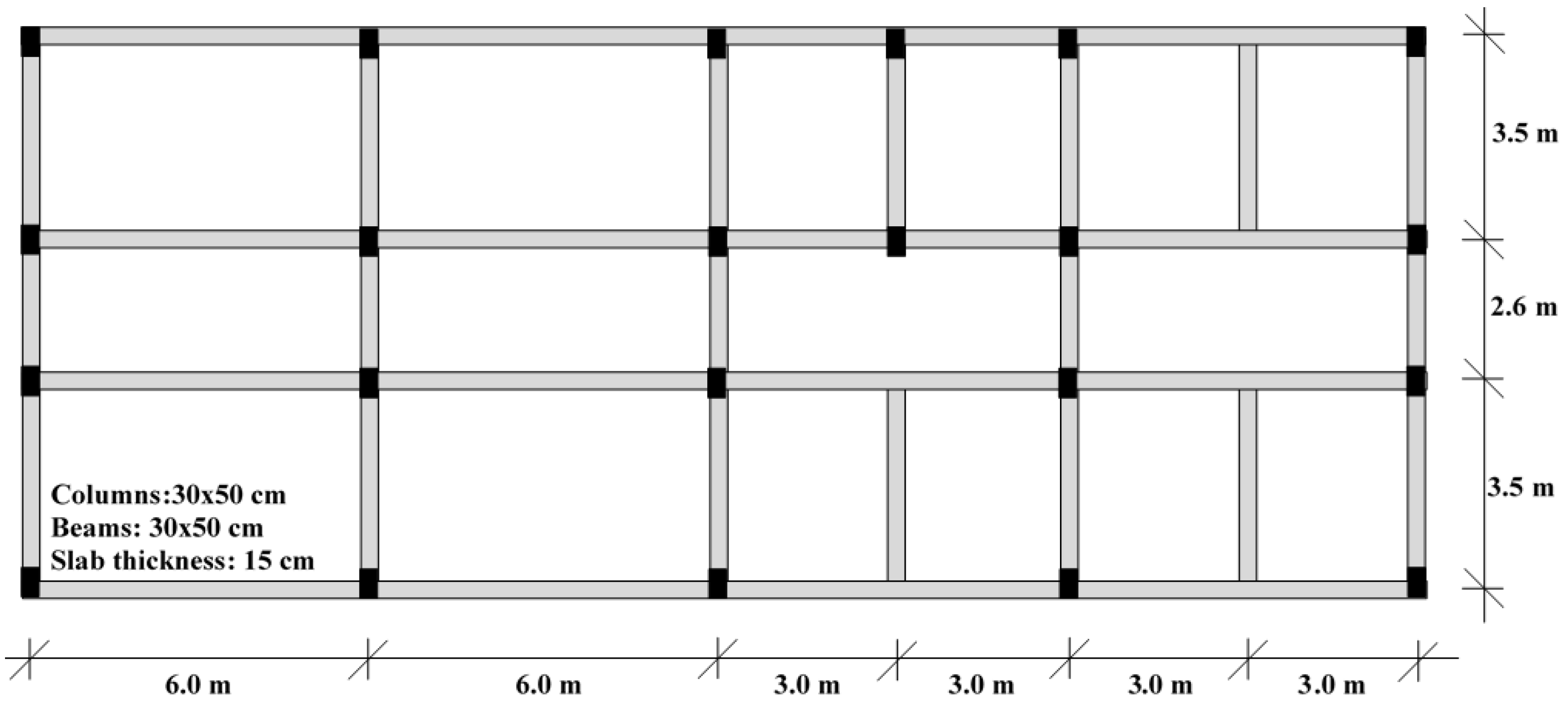

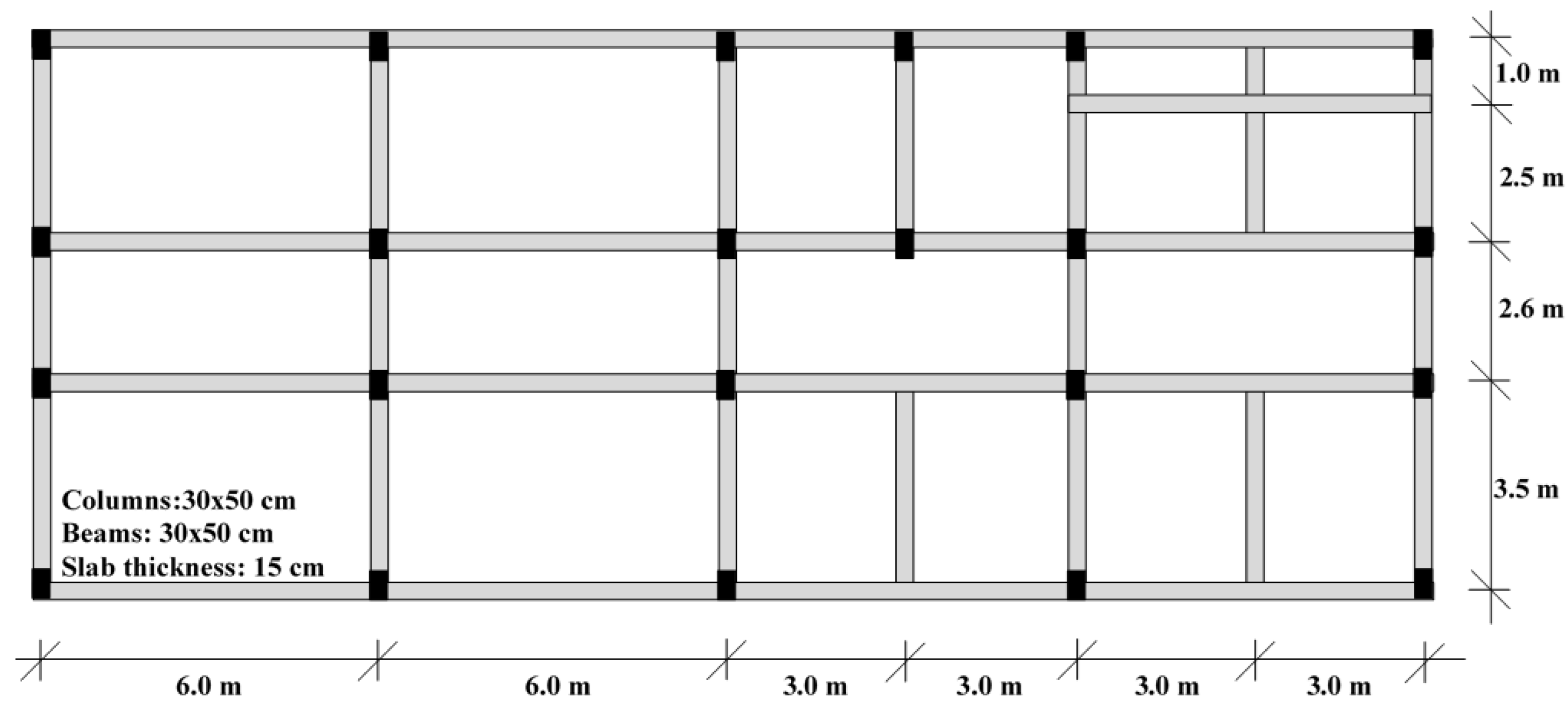

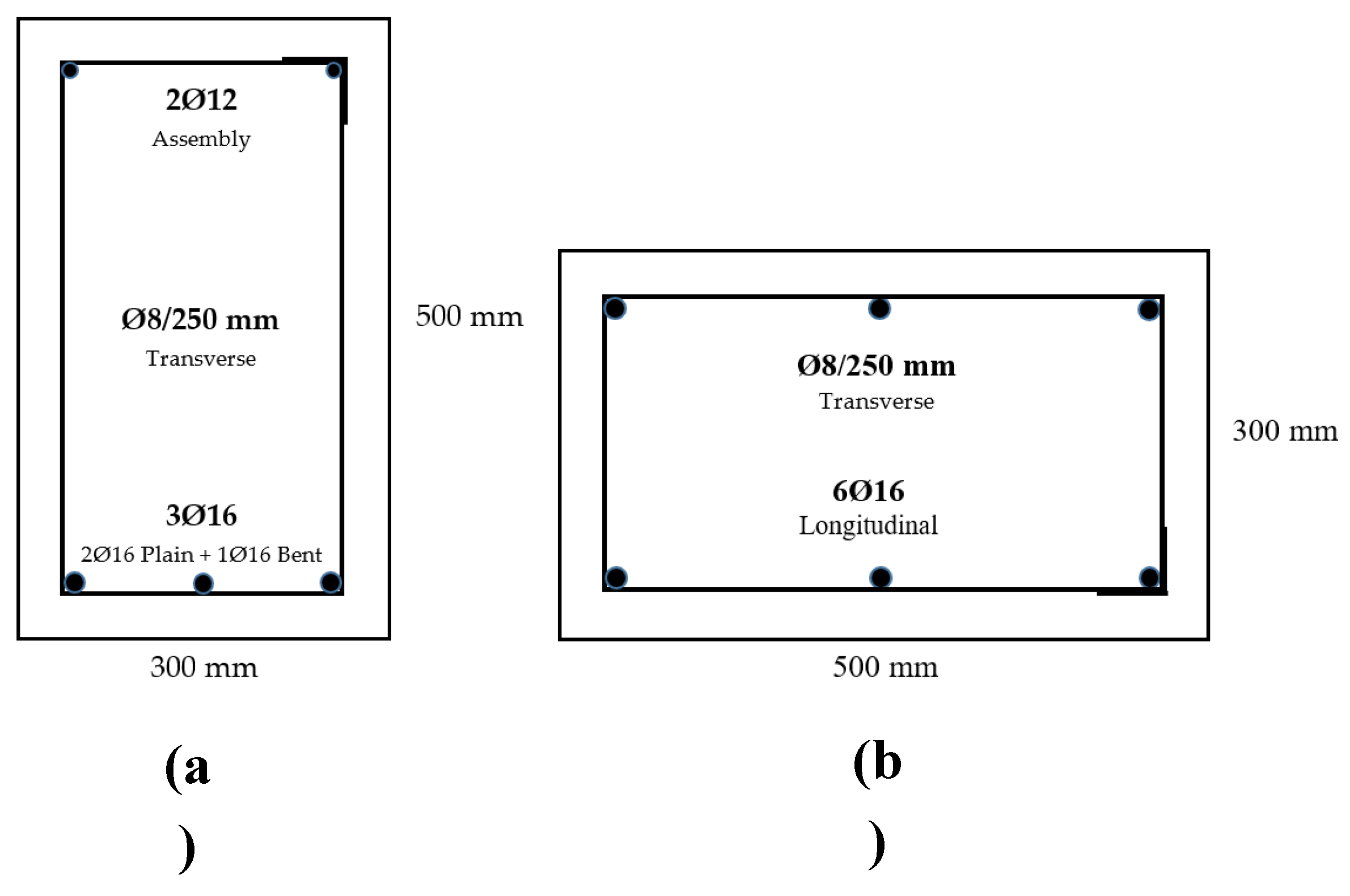

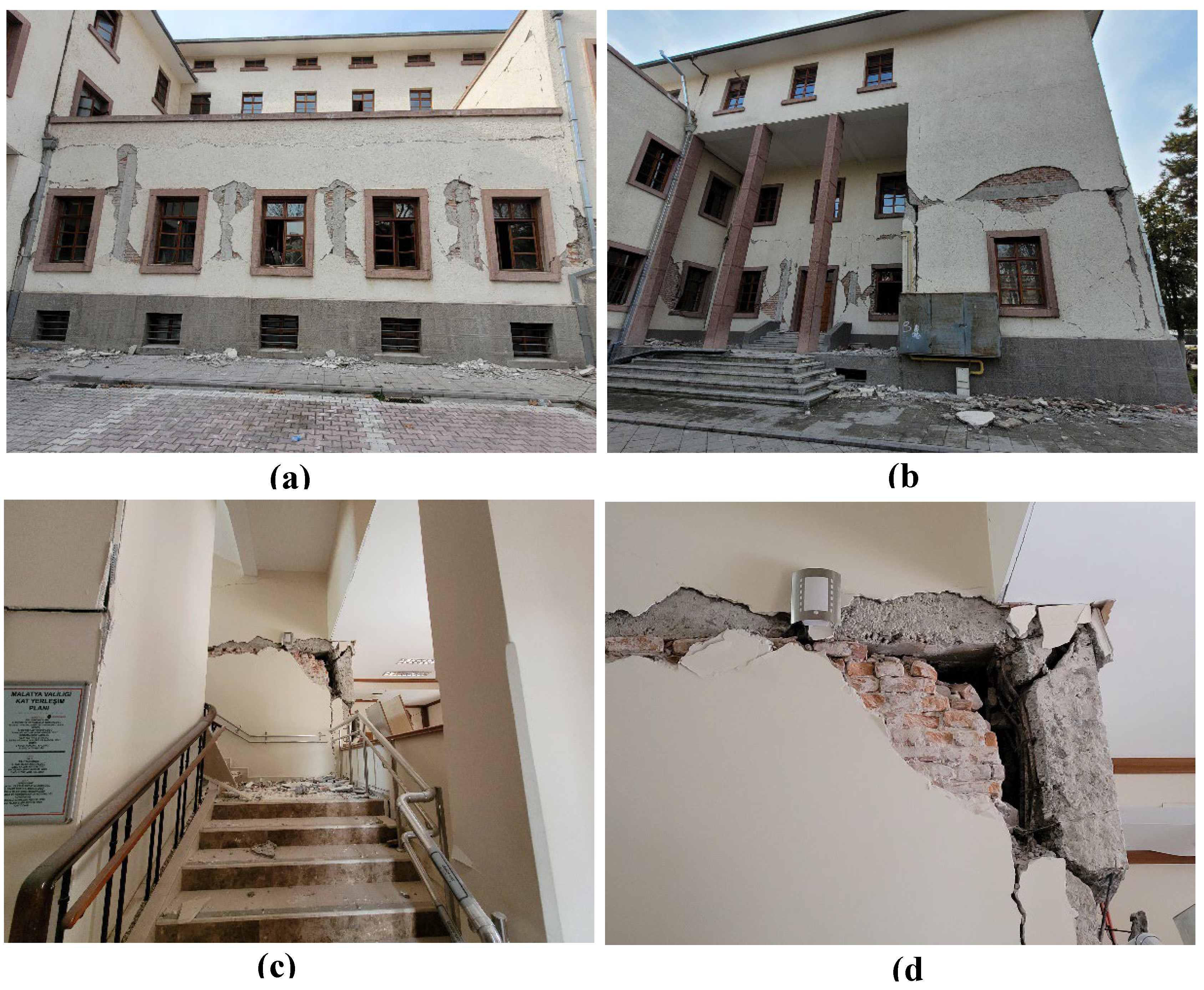

2.1. Data Collection from the Building According to RYTEİE (2019)

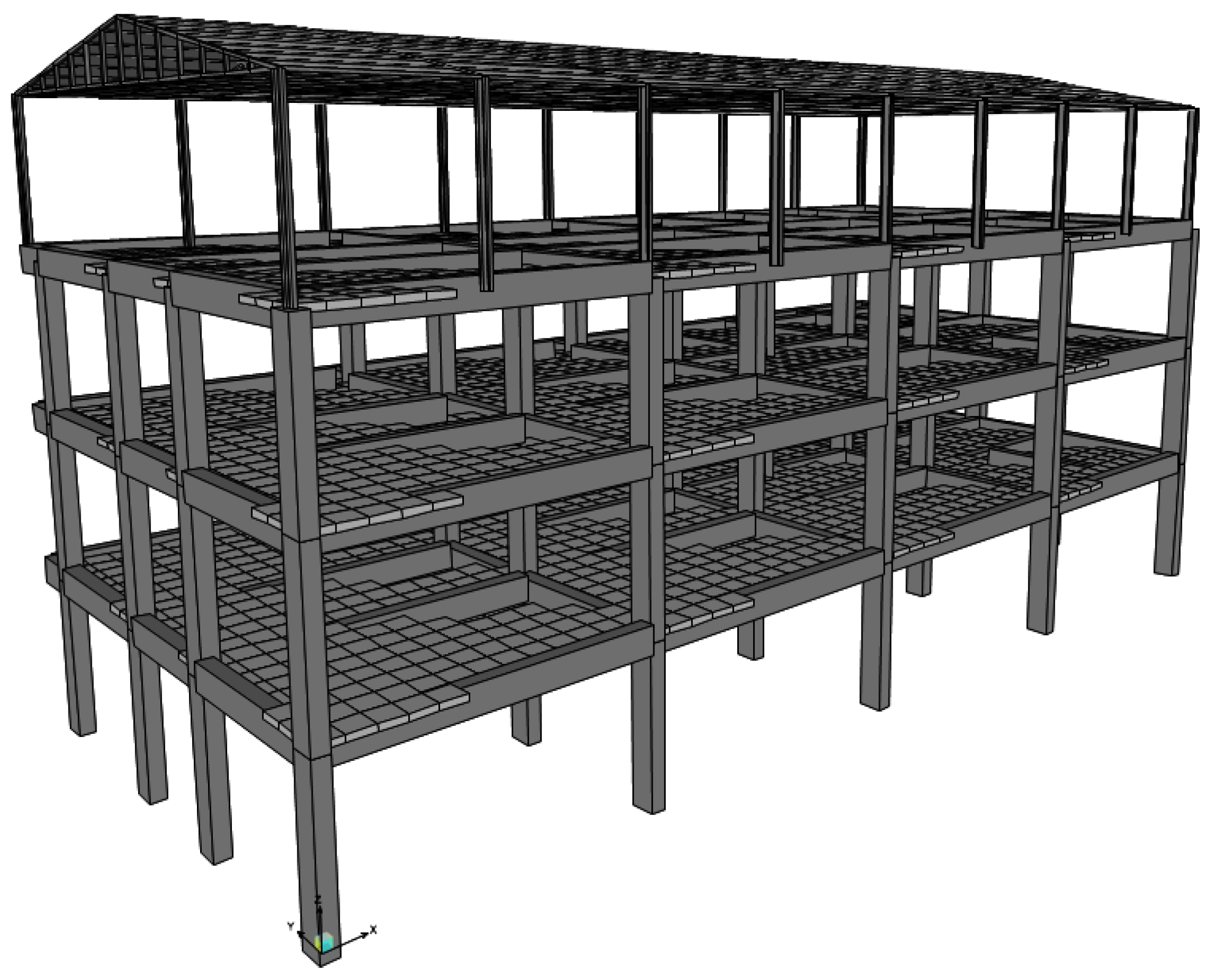

2.2. Creation of the Finite Element Model According to RYTEİE (2019)

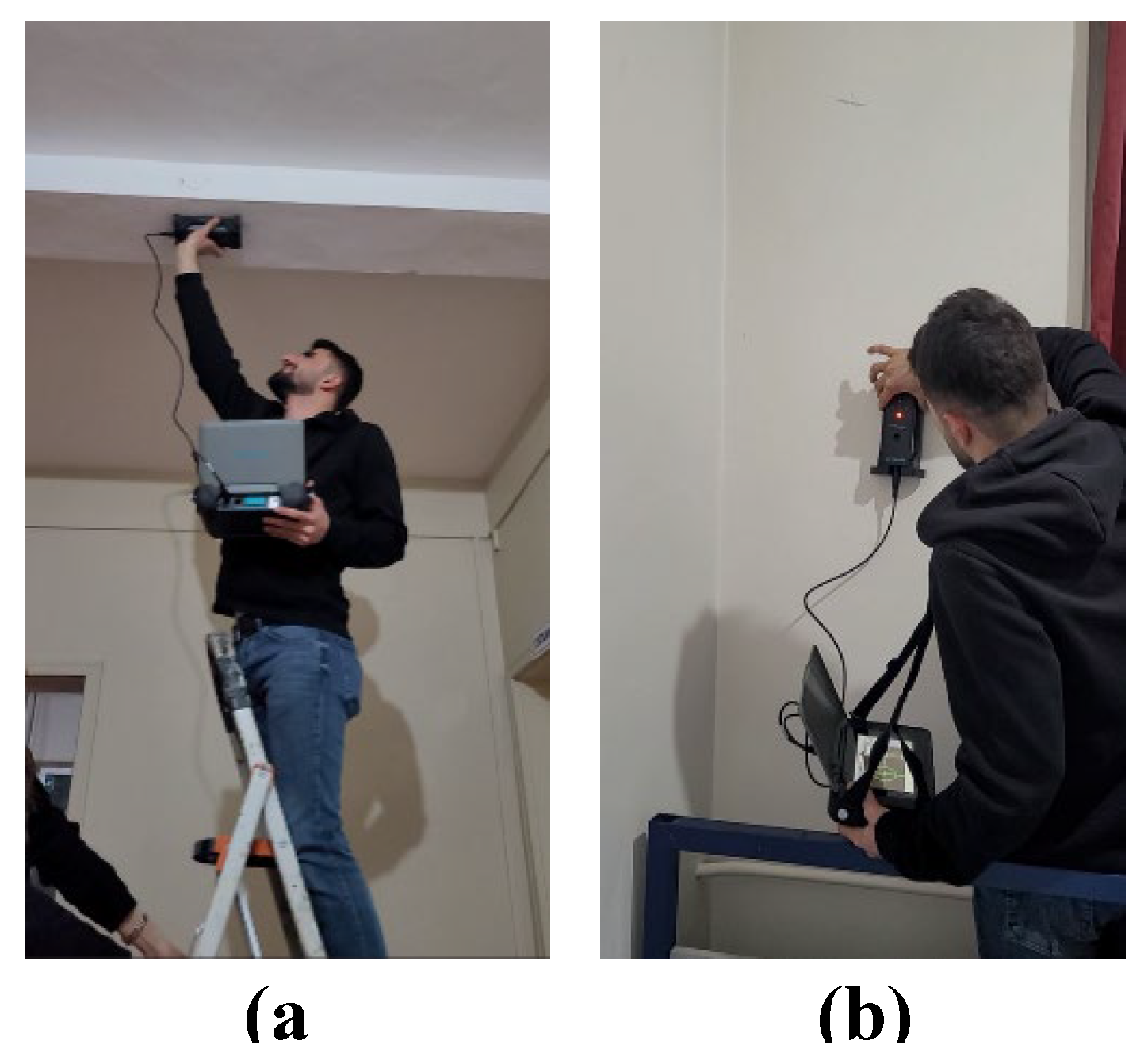

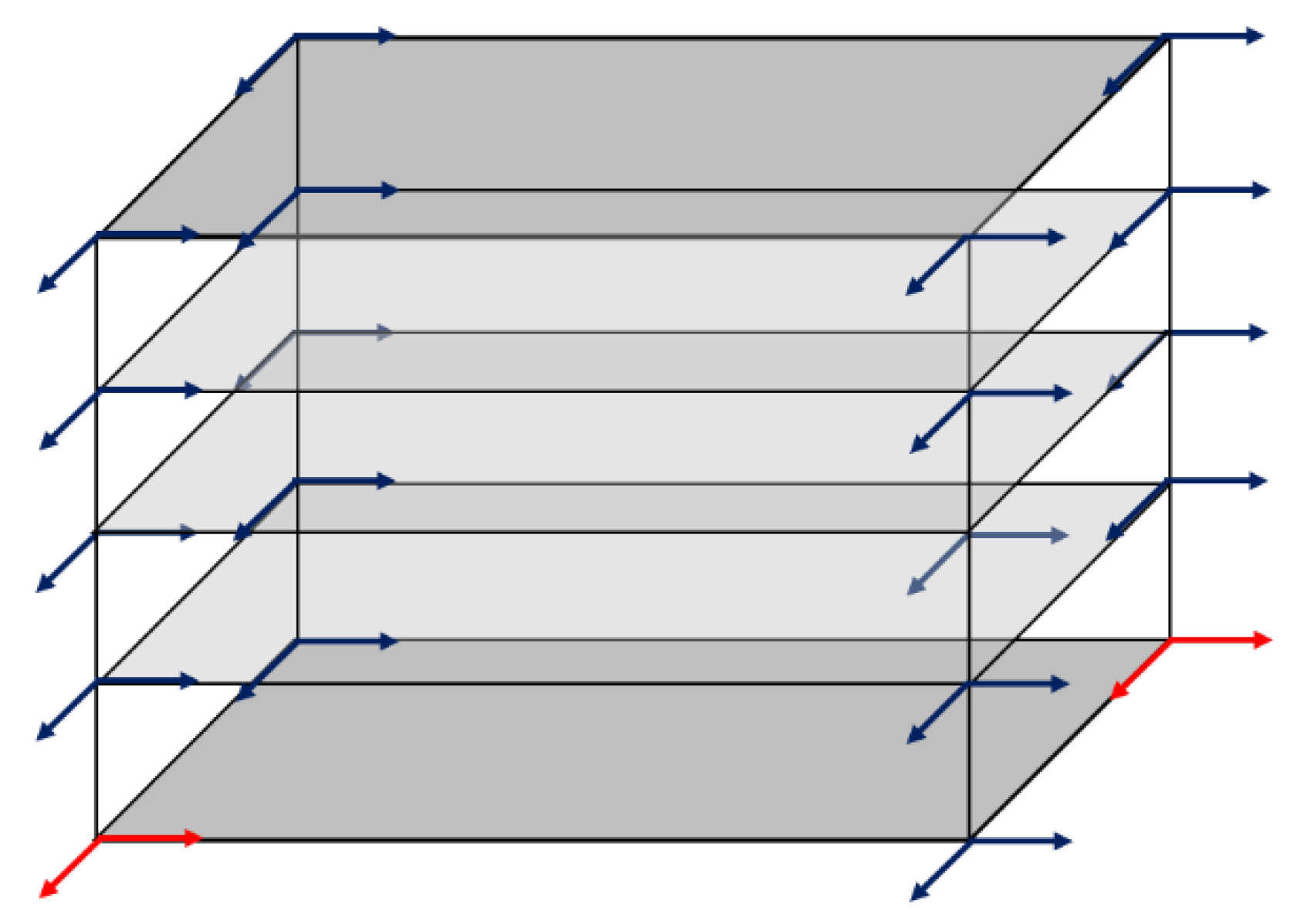

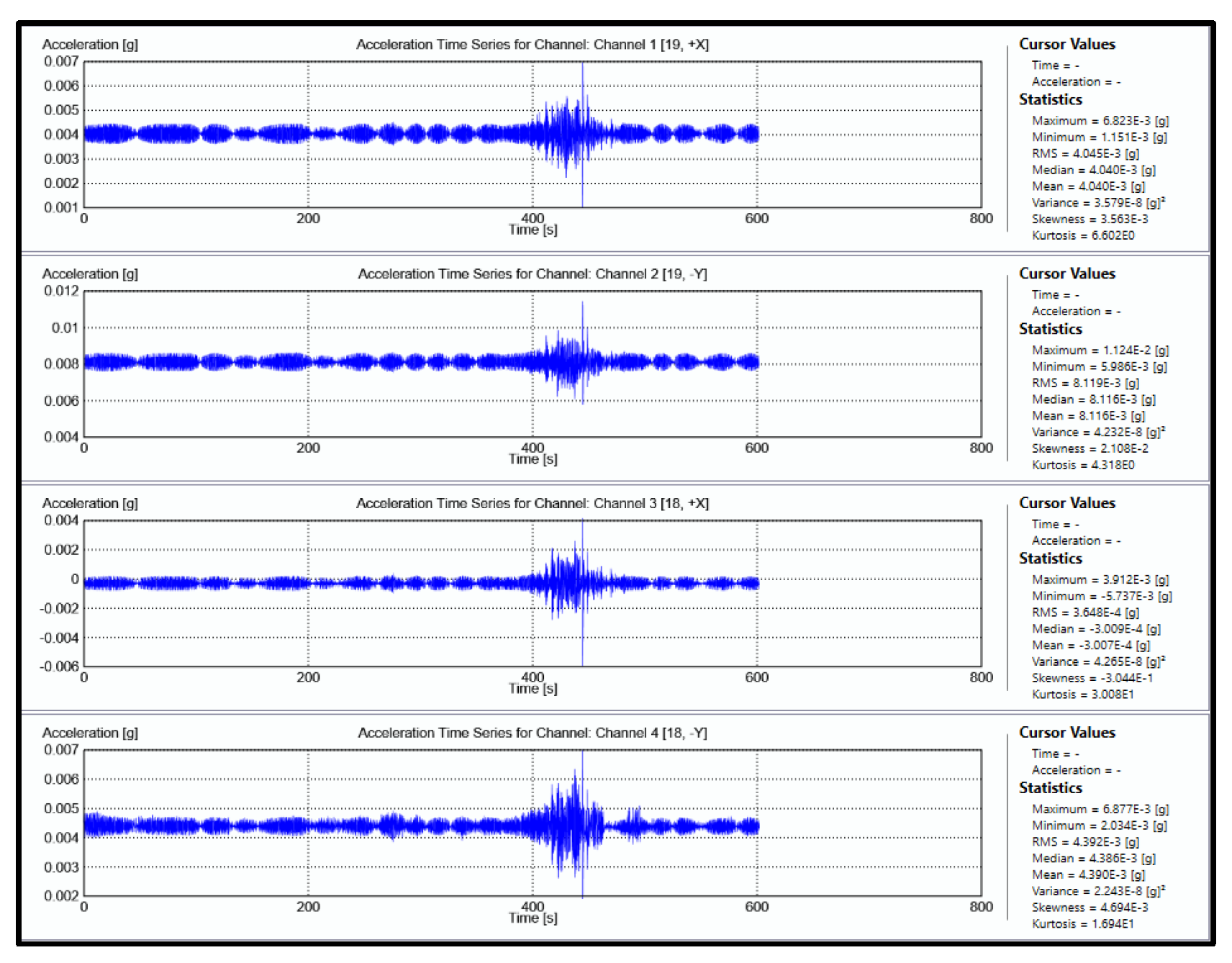

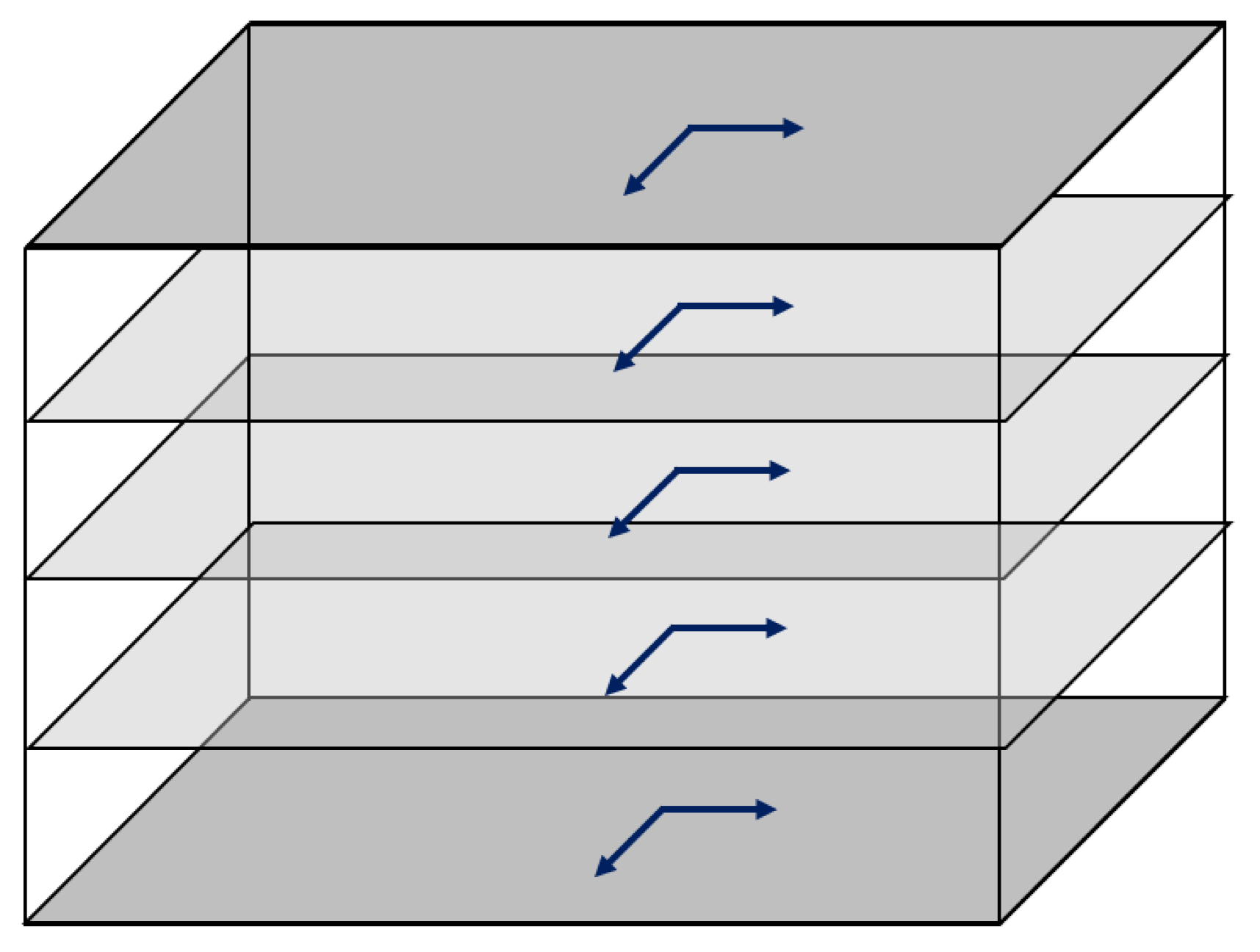

2.3. Operational Modal Analysis Applications

3. Results and Discussions

3.1. Results of Theoretical Modal Analysis

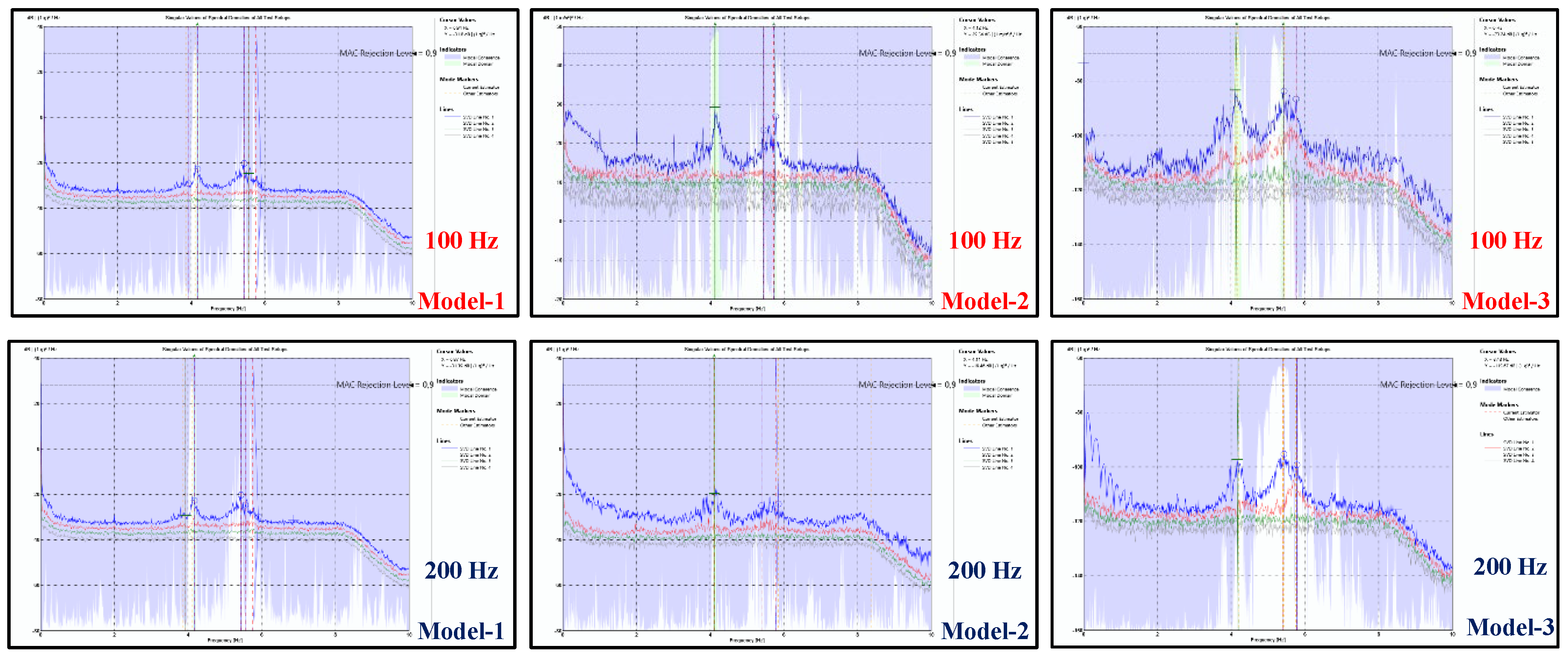

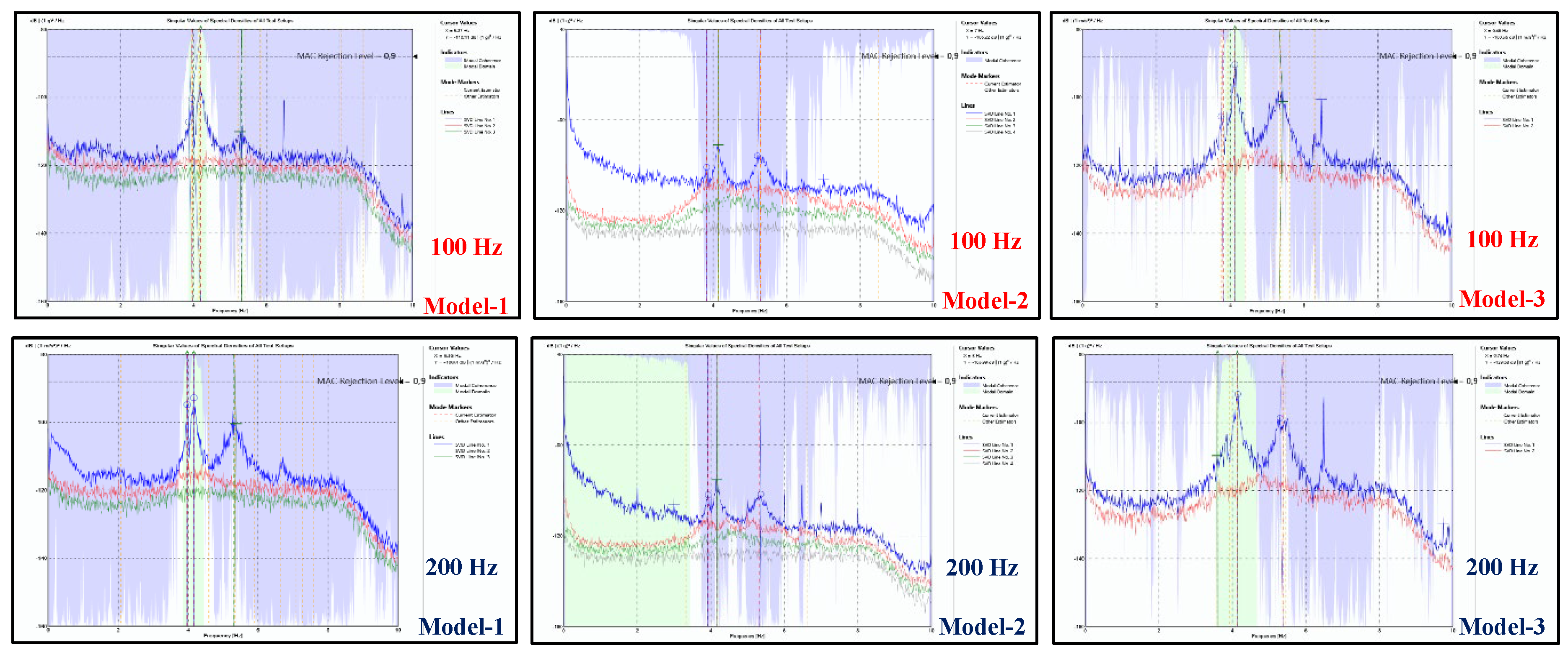

3.2. Results of Operational Modal Analysis

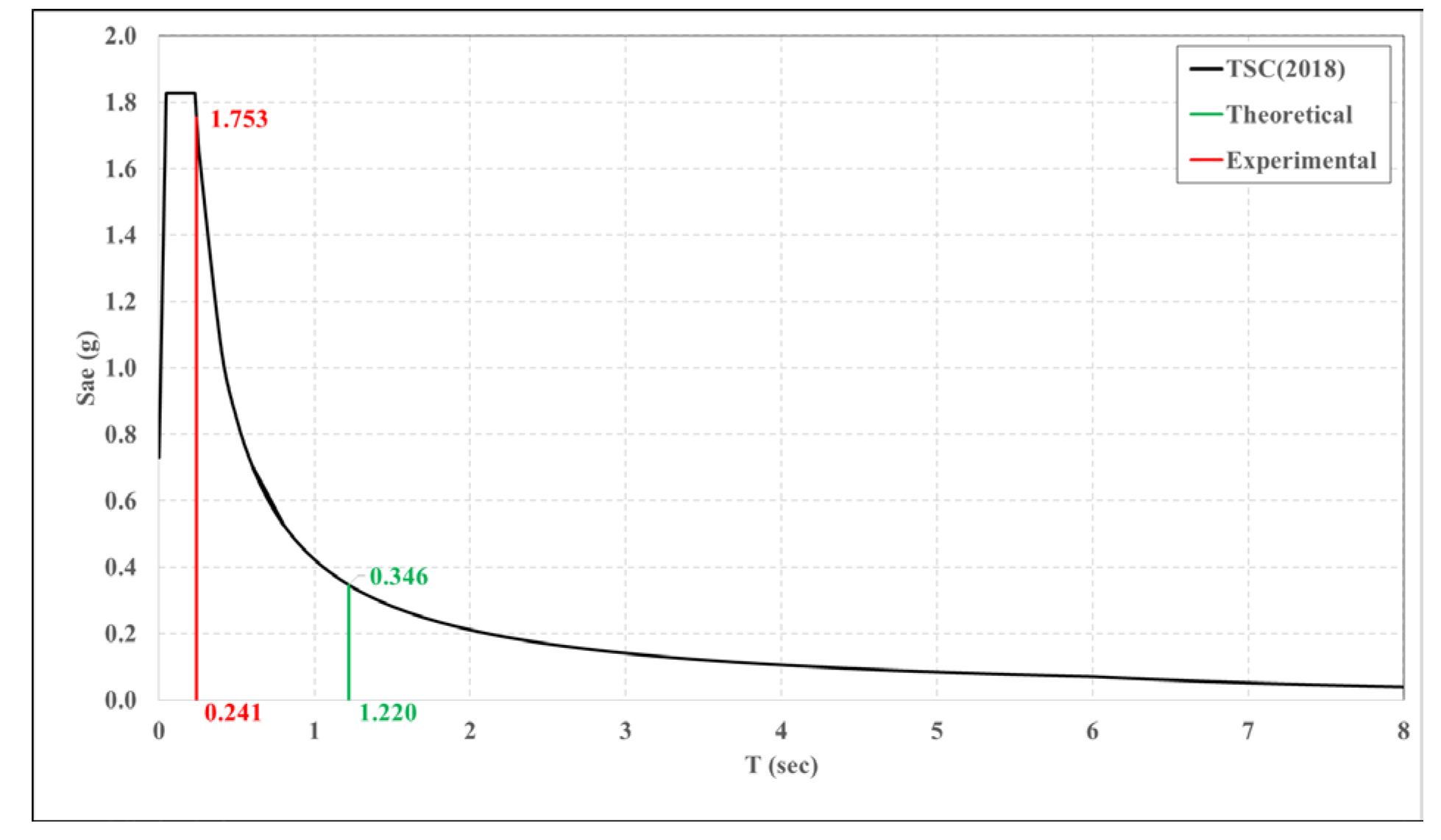

3.3. Combined Evaluation of Theoretical and Experimental Modal Analysis Results

- Creation of the finite element model for seismic performance assessment without considering the effect of infill walls, followed by theoretical modal analysis.

- Performing OMA studies based on the mode shapes calculated from the theoretical modal analysis and determining dynamic behavior parameters experimentally.

- Calibrating the finite element model to include the stiffness contributions of the infill walls, with the aim of aligning theoretical and experimental modal analysis results, particularly the natural vibration period

- Conducting structural analyses on the finite element model calibrated with infill wall additions to evaluate the seismic performance of the building.

5. Conclusions

- It has been concluded that the structural contributions of infill walls to the system's rigidity need to be incorporated into the finite element model of low-rise reinforced concrete buildings to accurately assess seismic risks in accordance with the RYTEİE (2019) rules. Considering the consensus in the relevant literature regarding the effects of infill walls, it is believed that the finite element model created by incorporating these effects will better represent the existing structure and allow for a technically more sound evaluation.

- It has been demonstrated that the modal behavior parameters of a low-rise reinforced concrete building can be experimentally determined using OMA applications. The relatively small volume of the building, coupled with environmental vibrations (e.g., traffic vibrations, human movement within the structure, etc.), allowed the building to be adequately excited, enabling the automatic extraction of mode shapes through response vibration measurements.

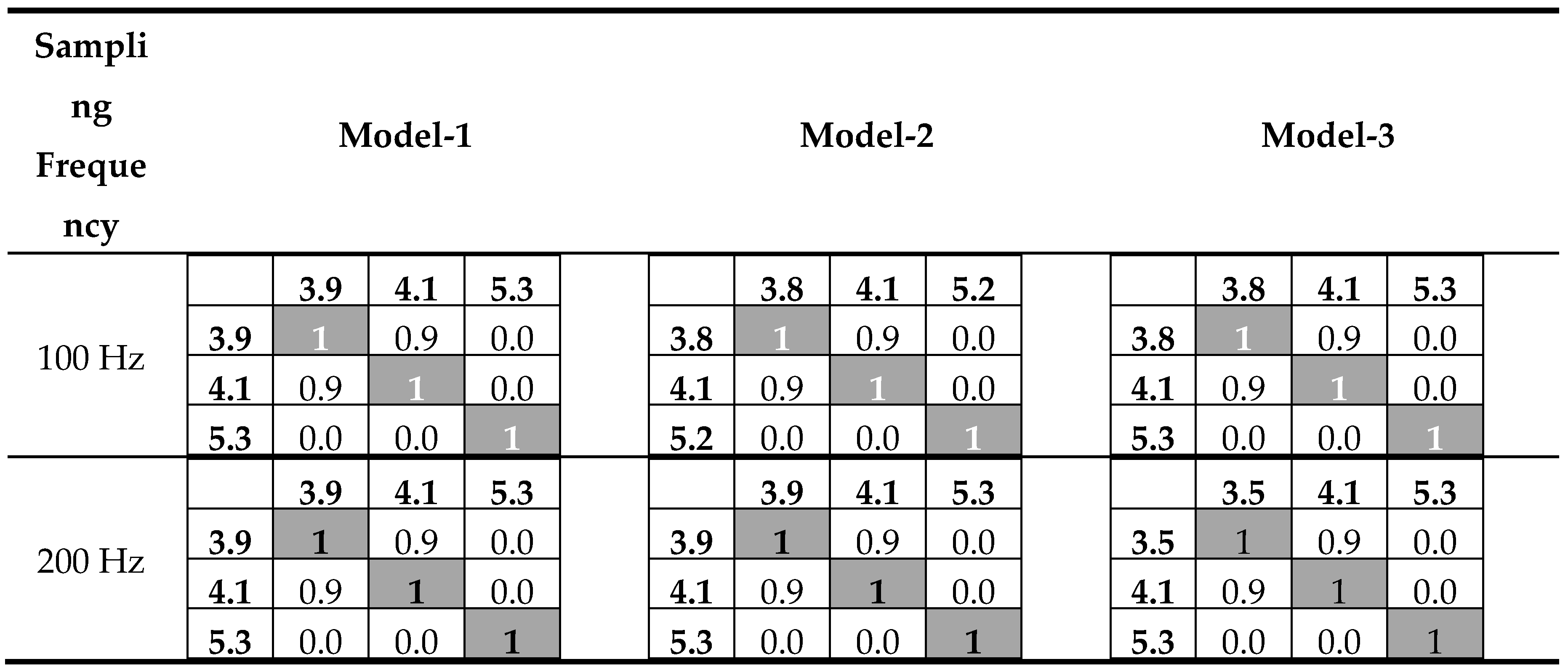

- In OMA applications on the low-rise reinforced concrete building, it was observed that modal behavior parameters could be easily obtained through the analysis of response vibration measurements of 100 Hz sampling frequency. Besides total measurement duration being equal to 500 times the theoretical natural vibration period was found to be adequate.

- It has been concluded that an OMA application (OMA-1/Model-1) that involves response vibration measurements at all points determined from theoretical modal analysis would not only provide modal behavior characteristics of the structure but also may supply valuable data regarding the structure's health. This type of OMA application also allowed for the detection and examination of interventions made to the structure, beyond its original state. However, this application was deemed to be time-consuming and required the use of a large number of sensors.

- Various options were explored for using the minimum number of sensors to determine the natural vibration period of the building through OMA. Reducing the number of sensors allows the process to be completed in a shorter time and at a lower cost. Based on the practical nature of OMA, it was concluded that the natural vibration period could also be determined by analyzing response vibration data collected with accelerometer sensors placed at the four corners of the top floor slab.

- The absence of a basement in the investigated building raised questions regarding the fixed-base definition of its foundation connections in the finite element model. However, no behavior contradicting the fixed-base connection modeling at the building's foundation was calculated following the OMA applications. This result led to the conclusion that, for low-rise reinforced concrete buildings with basements, the foundation connection can be assumed to be fixed, and that determining mode shapes and periods using response vibration measurements taken at the corner points along the top floor ceiling slab is feasible.

- In the OMA-2 applications conducted as part of sensor optimization studies, response vibrations were measured with accelerometer sensors placed at the rigidity center of each floor slab. While these applications were very fast and practical, it was observed that they could provide misleading modal behavior results for buildings that have undergone modifications (such as the addition of a roof floor as in the structure studied in this research). Additionally, in OMA-2 applications, mode shapes involving torsional motion around the vertical axis could not be identified. However, OMA-2 applications may be considered to be useful in determining the natural vibration period experimentally for low-rise buildings that have not been modified, although they may not be suitable for determining the general modal behavior of such structures. As a collective knowledge production practice, it is recommended that studies be conducted on this topic and their content shared with the literature.

- It is recommended to incorporate OMA applications into the seismic risk assessment of existing reinforced concrete buildings. By reflecting the dynamic behavior characteristics and structural health data obtained through OMA into the finite element model, and conducting structural analyses on the updated model, a much more realistic approach to performance evaluation can be achieved

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgements

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ASCE | American Society of Civil Engineers |

| Ct | Coefficient used to account for the structural system type |

| Ec | Modulus of Elasticity of Concrete |

| FEMA | Federal Emergency Management Agency |

| fcm | Concrete Axial Compressive Strength (MPa) |

| Gc | Shear Modulus of Concrete (MPa) |

| g | Acceleration of Gravity (9.8 m/s²) |

| H, HN | Total building height (meters) |

| INFORM | Index for Risk Management |

| IPE | I-shaped Profile, European standard for structural steel profiles |

| L | Plan length of the building considering the earthquake direction (meters) |

| MAC | Modal Assurance Criteria |

| OMA | Operational Modal Analysis |

| N | Total number of floors |

| RYTEİE | Principles for Identifying Risky Buildings (in Turkish) |

| RC | Reinforced concrete |

| s | Seconds |

| TpA, T, Ta | Period of the building (seconds) |

| TSC | Turkish Seismic Code |

| USD | United States Dollar |

| υ | Poisson’s Ratio |

| α | Coefficient defined as 0 for reinforced concrete buildings and 1 for buildings with a steel structural system |

References

- Statista. Development of the Number of Earthquakes Worldwide Since 2000. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/263105/development-of-the-number-of-earthquakes-worldwide-since-2000/ (accessed on 16 February 2025).

- AFAD. Event Catalog. Available online: https://deprem.afad.gov.tr/event-catalog (accessed on 17 February 2025).

- İletişim Başkanlığı. İnşa ve İhya. Cumhurbaşkanlığı, 2025. Available online: https://www.iletisim.gov.tr/images/uploads/dosyalar/Ihya_ve_Insa.pdf (accessed on 20 February 2025).

- Akıncı, A.C.; Ünlügenç, U.C. 6 Şubat 2023 Kahramanmaraş Depremleri: Sahadan Jeolojik Veriler, Değerlendirme ve Adana için Etkileri. Çukurova Üniversitesi Mühendislik Fakültesi Dergisi 2023, 38(2), 553–569. [CrossRef]

- Sabırsız, E.; Şöhret, M. 6 Şubat Depremlerinin Türkiye Ekonomisi Üzerindeki Makroekonomik, Sosyal ve Çevresel Etkileri. Akademik Yaklaşımlar Dergisi 2024, 15(1 - Deprem Özel Sayısı), 571–597. [CrossRef]

- JRC. INFORM Index. Available online: https://drmkc.jrc.ec.europa.eu/inform-index (accessed on 17 February 2025).

- Tozlu, S. Erzurum Tarihinde Depremler. In Tarih Boyunca Anadolu’da Doğal Afetler ve Deprem Semineri; İstanbul Üniversitesi Edebiyat Fakültesi Tarih Araştırma Merkezi: İstanbul, Turkey, 22–23 May 2000; pp. 93–117.

- Özdoğan, D.B. Investigation of the dynamic behavior of historical buildings using historical Erzurum earthquake records generated by stochastic modeling method. Ph.D. Thesis, Erzurum Teknik Üniversitesi, Fen Bilimleri Enstitüsü, Erzurum, Turkey, 2024. (In Turkish)

- Aslan, Ö. The Effect of Local Soil Conditions on Structural Damage of the March 13, 1992 Erzincan Earthquake. MSc Thesis, Istanbul Technical University, Institute of Science, 2015.(In Turkish).

- Okuyucu, D. Effects of Frame Aspect Ratio on the Seismic Performance Improvement of PC Panel Strengthening Technique, Ph.D. Thesis. Middle East Technical University, Ankara, Turkey, 2011.

- Wikipedia contributors. List of Earthquakes in Chile. Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Available online: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_earthquakes_in_Chile (accessed on 20 February 2025).

- U.S. Geological Survey. Earthquake Event Page for 1960 Chile Earthquake. Available online: https://earthquake.usgs.gov/earthquakes/eventpage/official19600522191120_30/shakemap/analysis?source=atlas&code=atlas19600522191117 (accessed on 20 February 2025).

- USGS. Impact Analysis of Earthquake Event: Official 1960 Chile Earthquake. United States Geological Survey. Available online: https://earthquake.usgs.gov/earthquakes/eventpage/official19600522191120_30/impact (accessed on 20 February 2025).

- MacroTrends. Chile Population. Available online: https://www.macrotrends.net/global-metrics/countries/chl/chile/population (accessed on 20 February 2025).

- Astroza, M.; Andrade, F.; Moroni, M.O. Confined Masonry Buildings: The Chilean Experience. In Proceedings of the 16th World Conference on Earthquake Engineering, Santiago, Chile, January 9–13, 2017; Paper No. 3462.

- Law No. 6306. Law on the Transformation of Areas Under Disaster Risk. Available online: https://www.mevzuat.gov.tr/mevzuat?MevzuatNo=6306&MevzuatTur=1&MevzuatTertip=5 (accessed on 20 February 2025).

- Regulation on the Implementation of Law No. 6306. Regulation on the Identification, Transformation, and Other Relevant Aspects of Risky Buildings (RYTEİE), 2019. Available online: https://www.mevzuat.gov.tr/mevzuat?MevzuatNo=16849&MevzuatTur=7&MevzuatTertip=5 (accessed on 20 February 2025).

- AFAD Erzurum IRAP. Erzurum Provincial Risk Reduction Plan (IRAP), 2025. Available online: https://erzurum.afad.gov.tr/kurumlar/erzurum.afad/IRAP/Erzurum_IRAP.pdf (accessed on 20 February 2025).

- TSC. Turkish Building Earthquake Code – Principles for the Design of Buildings Under Earthquake Effects, 2018. Available online: http://www.resmigazete.gov.tr/eskiler/2018/03/20180318M1-2-1.pdf (accessed on 10 September 2018).

- TS500. Turkish Standard for the Design and Construction of Reinforced Concrete Structures, Turkish Standards Institution, 1984.

- SAP2000-V21. SAP2000 Version 21, Computers and Structures, Inc., 2021. Erzurum Technical University.

- TS498. Turkish Standard for the Design and Construction of Reinforced Concrete Structures, Turkish Standards Institution, 2021.

- TSC. Turkish Earthquake Resistant Design Code (2007): Specifications for Buildings to be Built in Disaster Areas, Ministry of Public Works & Settlement, Ankara, 2007.

- ASCE7-16. Minimum Design Loads and Associated Criteria for Buildings and Other Structures in Seismic Design Requirements for Building Structures, Structural Engineering Institute, 2017, pp. 89–121. Available online: https://www.asce.org/asce-7/ (accessed on 10 September 2018).

- UBC-1997. Structural Design Requirements Earthquake Design, pp. 9–22. Available online: https://www.iccsafe.org/codes-tech-support/codes/ (accessed on 10 September 2018).

- EC8. Design of Structures for Earthquake Resistance in Part 1: General Rules, Seismic Actions and Rules for Buildings; 2004. Available online: https://eurocodes.jrc.ec.europa.eu/doc/WS_335/report/EC8_Seismic_Design_of_Buildings_Worked_examples.pdf (accessed on 10 September 2018)sistance in Part 1: General Rules, Seismic Actions and Rules for Buildings; 2004.

- ICPSRDB. Iranian Code of Practice for Seismic Resistant Design of Buildings; 2007. Available online: http://iisee.kenken.go.jp/worldlist/26_Iran/Iran%20National%20Seismic%20Code_2007_3rd%20Version_English.pdf (accessed on 10 September 2018).

- SI-413. Design Provisions for Earthquake Resistance of Structures; 2009. Available online: https://www.iec.co.il/Suppliers/101862470/Amendment%20No%205%20to%20SI%20413.pdf (accessed on 10 September 2018).

- Indian-Code. Criteria for Earthquake Resistant Design of Structures, in Design of Structures; 2002. Available online: http://iisee.kenken.go.jp/worldlist/24_India/24_India_Code.pdf (accessed on 10 September 2018).

- Au, S.-K. Operational Modal Analysis: Modeling, Bayesian Inference, Uncertainty Laws; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017.

- Rainieri, C.; Fabbrocino, G. Operational Modal Analysis of Civil Engineering Structures: An Introduction and Guide for Applications; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2014.

- Qin, Q.; Li, H.B.; Qian, L.Z.; Lau, C.-K. Modal Identification of Tsing Ma Bridge by Using Improved Eigensystem Realization Algorithm. Journal of Sound and Vibration 2001, 247, 325–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faecke, A.; Parolai, S.; Kling, S.M.; Stempniewski, L. Assessing the Vibrational Frequencies of the Cathedral of Cologne (Germany) by Means of Ambient Seismic Noise Analysis. Natural Hazards 2006, 38, 229–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasani, H.; Freddi, F. Operational Modal Analysis on Bridges: A Comprehensive Review. Infrastructures 2023, 8, 172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Şahin, M. Modal Behaviour Evaluation of a Rubber Bearing Isolated Structure under the Effects of Cold Weather by Operational Modal Analysis, MSc Thesis, Erzurum Technical University, Erzurum, Turkey, 2020. (In Turkish). [Google Scholar]

- Erkmen, E. Dynamic Identification Study on a Historical Cupola: Erzurum Three Cupolas Anonymous-2 Cupola Application, MSc Thesis, Erzurum Technical University, Erzurum, Turkey, 2022. (In Turkish). [Google Scholar]

- Yılmaz, M. Dynamic Identification Study on the Anonymous-I Cupola of Erzurum Three Cupolas, MSc Thesis, Erzurum Technical University, Erzurum, Turkey, 2022. (In Turkish). [Google Scholar]

- Gedik, Y. Dynamic Identification Study of Emir Saltuk Cupola, MSc Thesis, Erzurum Technical University, Erzurum, Turkey, 2022. (In Turkish). [Google Scholar]

- Özdoğan, D.B. Investigation of the Dynamic Behavior of Historical Buildings Using Historical Erzurum Earthquake Records Generated by Stochastic Modeling Method, PhD Thesis, Erzurum Technical University, Erzurum, Turkey, 2024. (In Turkish). [Google Scholar]

- Aymelek, A.; Yanık, Y.; Yıldırım, Ö.; Türker, T. Variations in the Natural Frequencies of Masonry Stone Minarets Depending on Temperature and Humidity. Journal of the Faculty of Engineering and Architecture of Gazi University 2025, 40, 951–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aslay, S.E.; Okuyucu, D. Technical Evaluation of Abscissa Damage of Erzincan Değirmenliköy Church. Journal of the Faculty of Engineering and Architecture of Gazi University 2020, 35, 387–402. [Google Scholar]

- Ramos, L.F.; Aguilar, R.; Lourenco, P.B. Operational Modal Analysis of Historical Constructions Using Commercial Wireless Platforms. Structural Health Monitoring 2010, 10, 511–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okuyucu, D. Operational Modal Analysis Method for Historic Masonry Structures: Applications. In Handbook of Cultural Heritage Analysis; D'Amico, S., Venuti, V., Eds.; Springer: Cham, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chisari, C.; Zizi, M.; Lavino, A.; Freda, S.; De Matteis, G. Operational Modal Analysis and Safety Assessment of a Historical Masonry Bell Tower. Applied Sciences 2024, 14, 10604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yanık, Y.; Türker, T.; Çalık, İ.; Yıldırım, Ö. Investigation of Environmental and Time-Dependent Effects on Historical Masonry Minarets Using Vibration Testing. Journal of the Faculty of Engineering and Architecture of Gazi University 2022, 37, 799–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelrazaq, A. Validating the Structural Behavior and Response of Burj Khalifa: Synopsis of the Full Scale Structural Health Monitoring Programs. International Journal of High-Rise Buildings 2012, 1, 37–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savaş, G.K. Evaluation of Construction Quality Control of Multi-Story Reinforced Concrete Structures Using the Operational Modal Analysis Method. Master’s Thesis, Erzurum Technical University, Erzurum, Turkey, 2020. (In Turkish). [Google Scholar]

- Eslek, T. A Comprehensive Investigation on the Direction and Monitoring of Interventions on Historical Masonry Structures Using Operational Modal Analysis. PhD Thesis, Erzurum Technical University, Erzurum, Turkey, 2025. (In Preparation). [Google Scholar]

- Romero, M.; Pachón, P.; Compán, V.; Cámara, M.; Pinto, F. Operational Modal Analysis: A Tool for Assessing Changes on Structural Health State of Historical Constructions after Consolidation and Reinforcement Works—Jura Chapel (Jerez de la Frontera, Spain). Shock and Vibration 2018, Volume 2018, Article ID 3710419, 12 pages. [CrossRef]

- Jacobsen, N.J.; Andersen, P. Operational Modal Analysis on Structures with Rotating Parts. In Proceedings of the ISMA Conference: International Conference on Noise and Vibration Engineering, Leuven, Belgium; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Okuyucu, D. Operational Modal Analysis Application on a Single Storey Reinforced Concrete Building, DÜMF MD 2020, 11, 3, 1407–1419. (In Turkish). [CrossRef]

- Artemis Modal Pro. Version 2024. Artemis International, 2024. Erzurum Technical University.

- Papadimitriou, D. Optimal Sensor Placement Methodology for Parametric Identification of Structural Systems. Journal of Sound and Vibration 2004, 278, 4–5, 923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brehm, M.; Zabel, V.; Bucher, C. Optimal Reference Sensor Positions Using Output-Only Vibration Test Data. Mechanical Systems and Signal Processing 2013, 41, 1–2, 196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Der Kiureghian, A. Robust Optimal Sensor Placement for Operational Modal Analysis Based on Maximum Expected Utility. Mechanical Systems and Signal Processing 2016, 75, 155–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelmar, T.; Chierichetti, M.; Davoudi Kakhki, F. Optimization of Sensor Placement for Modal Testing Using Machine Learning. Applied Sciences 2024, 14, 3040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mostafaei, H.; Ghamami, M. State of the Art in Automated Operational Modal Identification: Algorithms, Applications, and Future Perspectives. Machines 2025, 13, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Zheng, X.; Luo, Y.; Shen, Y.; Xue, Y.; Fu, W. An Approach for Time Synchronization of Wireless Accelerometer Sensors Using Frequency-Squeezing-Based Operational Modal Analysis. Sensors 2022, 22, 4784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walter, P.; Karl, P.; Kiefer, F.; Swanson, B.; Krug, E.; Ajupova, G. Wireless Sensors Applied to Modal Analysis. Sound & Vibration 2003, 37.

- Polyakov, S.V. On the Interactions Between Masonry Filler Walls and Enclosing Frame When Loaded in the Plane on the Wall. Translations in Earthquake Engineering 1960, Earthquake Engineering Research Institute, San Francisco, USA, pp. 36–42.

- Altın, S.; Ersoy, U.; Tankut, T. Hysteretic Response of Reinforced Concrete Infilled Frames. Journal of Structural Engineering, ASCE 1992, 118, 8, 2133–2150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asteris, P.G. Lateral Stiffness of Brick Masonry Infilled Plane Frames. Journal of Structural Engineering, ASCE 2003, 129, 8, 1071–1079. Mehrabi, A.; Shing, P.B.; Schuller, M.P.; Noland, J.L. Experimental Evaluation of Masonry Infilled RC Frames. Journal of Structural Engineering, ASCE 1996, 122, 3, 228–237.

- TSC. Regulation on Buildings to Be Constructed in Disaster Areas, Protection from Earthquake Hazards, 1998. Available online: http://www.resmigazete.gov.tr/eskiler/2007/07/20070714-7.htm (accessed on 10 September 2018).

- Sivri, M.; Demir, F.; Kuyucular, A. The Effects of Infill Walls, Frame Structures on the Earthquake Behavior and Failure Mechanism. Journal of Institute of Natural Sciences, Süleyman Demirel University 2006, 10, 1, 109–115.

- Tetik, D. Effect of Infill Walls on Free Vibration Characteristics of Reinforced Concrete Buildings; Master’s Thesis, Graduate School of Yildiz Technical University: Istanbul, Turkey, 2007. (In Turkish).

- Tüzün, C. Dynamic Analysis of RC Infilled Frames Structures; Master’s Thesis, Dokuz Eylül University: Izmir, Turkey, 1999. (In Turkish).

- Yıldırım, M.K. Determining the Period of Structure According to the Infill Wall Ratio of RC Frame Structures; Master’s Thesis, Graduate School of Yildiz Technical University: Istanbul, Turkey, 2009. (In Turkish).

- BSLJ. The Building Standard Law of Japan (BSLJ). Ministry of Construction, Japan, 1987.

- Chopra, A.K.; Goel, R.K. Building Period Formulas for Estimating Seismic Displacements. Earthquake Spectra 2000, 16, 33–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, L.L.; Hwang, W.L. Empirical Formula for Fundamental Vibration Periods of Reinforced Concrete Buildings in Taiwan. Earthquake Engineering and Structural Dynamics 2000, 29, 327–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crowley, H.; Pinho, R. Simplified Equations for Estimating the Period of Vibration of Existing Buildings. In Proceedings of the First European Conference on Earthquake Engineering and Seismology, Geneva, Switzerland, 3–8 September 2006; p. 1122. [Google Scholar]

- Guler, K.; Yuksel, E.; Kocak, A. Estimation of the Fundamental Vibration Period of Existing RC Buildings in Turkey Utilizing Ambient Vibration Records. Journal of Earthquake Engineering 2008, 12, 140–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatzigeorgiou, G.D.; Kanapitsas, G. Evaluation of Fundamental Period of Low-Rise and Mid-Rise Reinforced Concrete Buildings. Earthquake Engineering and Structural Dynamics 2013, 42, 1599–1616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kose, M.M. Parameters Affecting the Fundamental Period of RC Frame with Infill Walls. Engineering Structures 2009, 39, 93–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asteris, P.G.; Repapis, C.C.; Repapi, E.V.; Cavaleri, L. Fundamental Period of Infilled Reinforced Concrete Frame Structures. Structure and Infrastructure Engineering 2017, 7, 929–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yiğit, A.; Erdil, B.; Akkaya, İ. A Simplified Fundamental Period Equation for RC Buildings. Građevinar 2021, 73, 5, 483–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koçak, A.; Yıldırım, M.K. Effects of Infill Wall Ratio on the Period of Reinforced Concrete Framed Buildings. Advances in Structural Engineering 2011, 14, 5, 731–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Earthquake Hazard Map of Türkiye. Available online: https://tdth.afad.gov.tr/ (accessed on 3 February 2025).

- ASCE 41-06. Seismic Rehabilitation of Existing Buildings; American Society of Civil Engineers: Virginia, Reston, 2006.

- Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA). Prestandard and Commentary for the Seismic Rehabilitation of Buildings, Report No. FEMA 356, FEMA: Washington, DC, 2000.

| Rank | Country | Earthquake Risk Score |

| 1 | Nepal | 9.8 |

| 2 | Philippines | 9.7 |

| 3 | Japan | 9.7 |

| 4 | Peru | 9.6 |

| 5 | Chilie | 9.6 |

| 6 | Ecuador | 9.5 |

| 7 | Guatemala | 9.5 |

| 8 | Iran | 9.3 |

| 9 | Türkiye | 9.3 |

| 10 | Pakistan | 9.2 |

| Specimen | Compressive Strength (MPa) |

| 1 | 11.7 |

| 2 | 8.2 |

| 3 | 8.4 |

| 4 | 12.8 |

| 5 | 12.7 |

| 6 | 11.6 |

| Mean: | 10.9 |

| Regulation/Code | Empirical Equation | Values of the Parameter | Period (s) |

| TSC(2007) [23] | TpA=Ct*HN3/4 | Ct=0.1, HN=13 m | 0.685 |

| TSC (2018) [19] | TpA=Ct*HN3/4 | Ct= 0.1, HN=13 m | 0.685 |

| ASCE 7-16 (2017) [24] | 0,1N | N=4 | 0.400 |

| ASCE 7-16 (2017) [24] | T= Ct*HNx | HN=13 m, Ct=0.0466, x=0.9 | 0.469 |

| Uniform Building Code(1997) [25] | T= Ct*HN3/4 | Ct : 0.0731, HN=13 m | 0.500 |

| Eurocode 8 (2004) [26] | T= Ct*H3/4 | Ct=0.075, HN=13 m | 0.513 |

| Iran Code (2007) [27] | T= 0.070*H3/4 | H=13 m | 0.479 |

| Israil Code (2009) [28] | T= 0.075*H3/4 | H=13 m | 0.513 |

| Indian Code (2002) [29] | T= 0.075*H3/4 | H=13 m | 0.513 |

| Mode Number | Mode Shape | Period (s) |

| 1 |

Horizontal translational movement parallel to the long plan direction |

1.220 |

| 2 |

Horizontal translational movement parallel to short plan direction |

0.819 |

| 3 |

Lateral torsional movement around the vertical axis |

0.800 |

| 4 |

Horizontal translational movement of the roof floor parallel to the long plan direction* |

0.793 |

| 5 |

Vertical torsional movement around the short span direction of the structure |

0.392 |

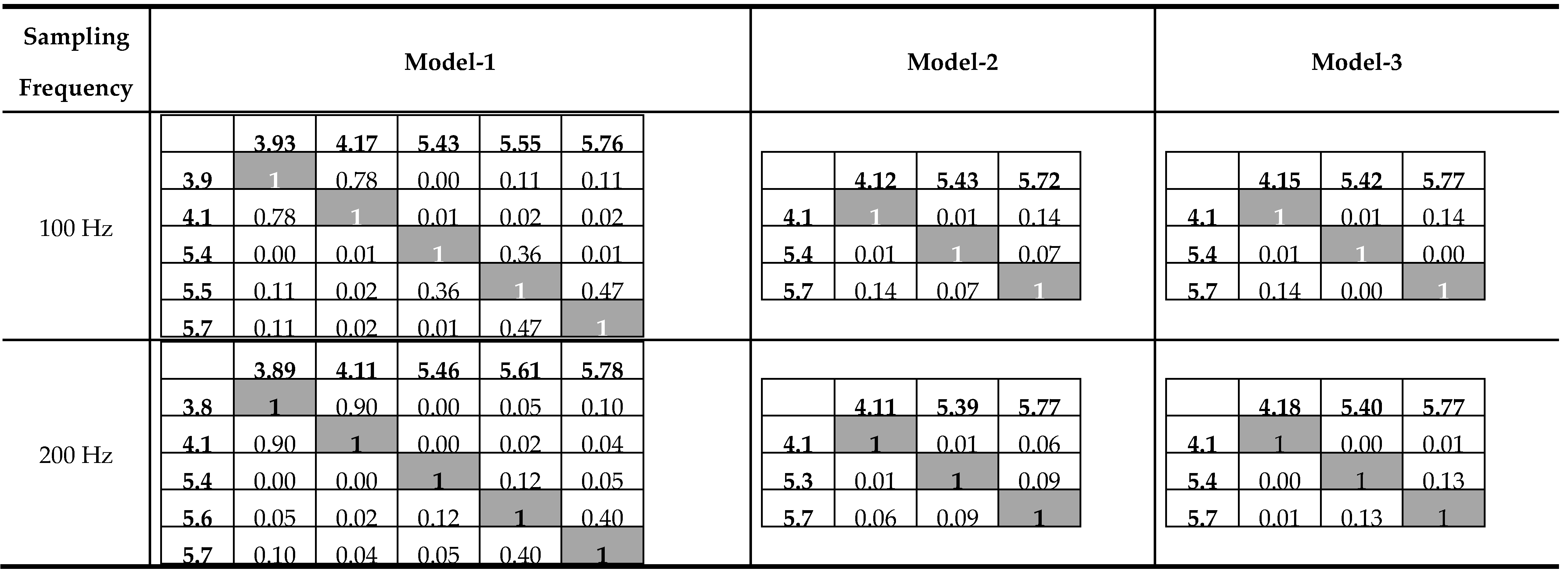

| Model-1 | Model-2 | Model-3 | ||||

Sensor placement in all floors |

Sensor placement in the ground floor and the top floor |

Sensor placement in only the top floor |

||||

| Mode Number | Mode Shape | Period (s) | Mode Shape | Period (s) | Mode Shape | Period (s) |

| 1 | Horizontal translational movement of the roof floor parallel to the short plan direction | 0.254 | Horizontal translational movement parallel to the short plan direction | 0.243 | Horizontal translational movement parallel to the short plan direction | 0.241 |

| 2 | Horizontal translational movement parallel to the short plan direction | 0.240 | Horizontal translational movement parallel long plan direction | 0.184 | Horizontal translational movement parallel long plan direction | 0.184 |

| 3 | Horizontal translational movement parallel long plan direction | 0.184 | Lateral torsional movement around the vertical axis | 0.175 | Lateral torsional movement around the vertical axis | 0.173 |

| 4 | Lateral torsional movement of the roof floor around the vertical axis | 0.180 | - | - | - | - |

| 5 | Lateral torsional movement around the vertical axis | 0.174 | - | - | - | - |

| Model-1 | Model-2 | Model-3 | ||||

Sensor placement in all floors |

Sensor placement in the ground floor and the top floor |

Sensor placement in only the top floor |

||||

| Mode Number | Mode Shape | Period (s) | Mode Shape | Period (s) | Mode Shape | Period (s) |

| 1 | Horizontal translational movement of the roof floor parallel to the short plan direction | 0.257 | Horizontal translational movement parallel to the short plan direction | 0.243 | Horizontal translational movement parallel to the short plan direction | 0.239 |

| 2 | Horizontal translational movement parallel to the short plan direction | 0.243 | Horizontal translational movement parallel long plan direction | 0.185 | Horizontal translational movement parallel long plan direction | 0.185 |

| 3 | Horizontal translational movement parallel long plan direction | 0.183 | Lateral torsional movement around the vertical axis | 0.173 | Lateral torsional movement around the vertical axis | 0.173 |

| 4 | Lateral torsional movement of the roof floor around the vertical axis | 0.178 | - | - | - | - |

| 5 | Lateral torsional movement around the vertical axis | 0.173 | - | - | - | - |

| Model-1 | Model-2 | Model-3 | ||||

Sensor placement in all floors |

Sensor placement in the ground floor and the top floor |

Sensor placement in only the top floor |

||||

| Mode Number | Mode Shape | Period (s) | Mode Shape | Mode Number | Mode Shape | Period (s) |

| 1 | Horizontal translational movement of the roof floor parallel to the short plan direction | 0.255 | Horizontal translational movement parallel to the short plan direction | 0.243 | Horizontal translational movement parallel to the short plan direction | 0.240 |

| 2 | Horizontal translational movement parallel to the short plan direction | 0.242 | Horizontal translational movement parallel long plan direction | 0.185 | Horizontal translational movement parallel long plan direction | 0.185 |

| 3 | Horizontal translational movement parallel long plan direction | 0.183 | Lateral torsional movement around the vertical axis | 0.174 | Lateral torsional movement around the vertical axis | 0.173 |

| 4 | Lateral torsional movement of the roof floor around the vertical axis | 0.179 | - | - | - | - |

| 5 | Lateral torsional movement around the vertical axis | 0.173 | - | - | - | - |

| Mode Number | Mode Shape | Period (s) |

| 1 | Horizontal translational movement of the roof floor parallel to the short plan direction | 0.255 |

| 2 | Horizontal translational movement parallel to the short plan direction | 0.241 |

| 3 | Horizontal translational movement parallel long plan direction | 0.184 |

| 4 | Lateral torsional movement of the roof floor around the vertical axis | 0.179 |

| 5 | Lateral torsional movement around the vertical axis | 0.173 |

| Model-1 | Model-2 | Model-3 | ||||

Sensor placement in all floors |

Sensor placement in the ground floor and the top floor |

Sensor placement in only the top floor |

||||

| Mode Number | Mode Shape | Period (s) | Mode Shape | Period (s) | Mode Shape | Period (s) |

| 1 | Horizontal translational movement parallel to the short plan direction | 0.252 | Horizontal translational movement parallel to the short plan direction | 0.261 | Horizontal translational movement parallel to the short plan direction | 0.263 |

| 2 | Horizontal translational movement parallel to the short plan direction | 0.238 | Horizontal translational movement parallel to the short plan direction | 0.242 | Horizontal translational movement parallel to the short plan direction | 0.242 |

| 3 | Horizontal translational movement parallel long plan direction | 0.188 | Horizontal translational movement parallel long plan direction | 0.189 | Horizontal translational movement parallel long plan direction | 0.188 |

| Model-1 | Model-2 | Model-3 | ||||

Sensor placement in all floors |

Sensor placement in the ground floor and the top floor |

Sensor placement in only the top floor |

||||

| Mode Number | Mode Shape | Period (s) | Mode Shape | Period (s) | Mode Shape | Period (s) |

| 1 | Horizontal translational movement parallel to the short plan direction | 0.252 | Horizontal translational movement parallel to the short plan direction | 0.255 | Horizontal translational movement parallel to the short plan direction | 0.278 |

| 2 | Horizontal translational movement parallel to the short plan direction | 0.240 | Horizontal translational movement parallel to the short plan direction | 0.240 | Horizontal translational movement parallel to the short plan direction | 0.242 |

| 3 | Horizontal translational movement parallel long plan direction | 0.188 | Horizontal translational movement parallel long plan direction | 0.188 | Horizontal translational movement parallel long plan direction | 0.186 |

| Model-1 | Model-2 | Model-3 | ||||

Sensor placement in all floors |

Sensor placement in the ground floor and the top floor |

Sensor placement in only the top floor |

||||

| Mode Number | Mode Shape | Period (s) | Mode Shape | Period (s) | Mode Shape | Period (s) |

| 1 | Horizontal translational movement parallel to the short plan direction | 0.252 | Horizontal translational movement parallel to the short plan direction | 0.258 | Horizontal translational movement parallel to the short plan direction | 0.270 |

| 2 | Horizontal translational movement parallel to the short plan direction | 0.239 | Horizontal translational movement parallel to the short plan direction | 0.241 | Horizontal translational movement parallel to the short plan direction | 0.242 |

| 3 | Horizontal translational movement parallel long plan direction | 0.188 | Horizontal translational movement parallel long plan direction | 0.188 | Horizontal translational movement parallel long plan direction | 0.187 |

| Mode Number | Mode Shape | Period (s) |

| 1 | Horizontal translational movement parallel to the short plan direction | 0.260 |

| 2 | Horizontal translational movement parallel to the short plan direction | 0.241 |

| 3 | Horizontal translational movement parallel long plan direction | 0.188 |

| Theoretical Modal Anlysis | Operational Modal Analysis | |||||

| RYTEİE (2019) | OMA-1 | OMA-2 | ||||

| Mode Number | Mode Shape | Period (s) | Mode Shape | Period (s) | Mode Shape | Period (s) |

| 1 | Horizontal translational movement parallel to the long plan direction | 1.220 | Horizontal translational movement of the roof floor parallel to the short plan direction | 0.255 | Horizontal translational movement parallel to the short plan direction | 0.260 |

| 2 | Horizontal translational movement parallel to the short plan direction | 0.819 | Horizontal translational movement parallel to the short plan direction | 0.241 | Horizontal translational movement parallel to the short plan direction | 0.241 |

| 3 | Lateral torsional movement around the vertical axis |

0.800 | Horizontal translational movement parallel long plan direction | 0.184 | Horizontal translational movement parallel long plan direction | 0.188 |

| 4 | Horizontal translational movement of the roof floor parallel to the long plan direction | 0.793 | Lateral torsional movement of the roof floor around the vertical axis | 0.179 | - |

- |

| 5 | Vertical torsional movement around the short span direction of the structure | 0.392 | Lateral torsional movement around the vertical axis | 0.173 | - | - |

| Regulation/Code | Empirical Equation | Value of the Parameter | Period (s) |

| TSC(1998) [63] | T=Ct*HN3/4 | Ct=0.05, HN=13 m | 0.342 |

| TSC(2007) [23] | TpA=Ct*HN3/4 | Ct=0.07, HN=13 m | 0.479 |

| TSC (2018) [19] | TpA=Ct*HN3/4 | Ct= 0.07, HN=13 m | 0.479 |

| ASCE 7-16 (2017) [24] | 0,1N | N=4 | 0.400 |

| ASCE 7-16 (2017) [24] | T= Ct*HNx | HN=13 m, Ct=0.0488, x=0.75 | 0.334 |

| Uniform Building Code(1997) [25] | T= Ct*HN3/4 | Ct : 0.0488, HN=13 m | 0.334 |

| Eurocode 8 (2004) [26] | T= Ct*H3/4 | Ct=0.05, HN=13 m | 0.342 |

| Iran Code (2007) [27] | T= 0.050*H3/4 | H=13 m | 0.342 |

| Israil Code (2009) [28] | T= 0.050*H3/4 | H=13 m | 0.342 |

| Study | Empirical Equation | Period (s) |

| Chopra and Goel (2000) [69] | T= 0.067*H0.9 | 0.674 |

| Hong and Hwang (2000) [70] | T= 0.0294*H0.804 | 0.231 |

| Crowley and Pinho (2006) [71] | T= 0.055*H | 0.715 |

| Güler et al. (2008)[72] | T= 0.026*H0.9 | 0.262 |

| Hatzigeorgiou and Kanapitsas (2013) [73] | T= 0.075*H0.75 | 0.452 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).