1. Introduction

Precision temperature control is a key technology in the industrial dispensing system. To ensure the stable quality of the products produced by the dispensing applicator, various components such as the press plate, quantitative filling machine valves, heating module, adhesive gun copper sleeve, and adhesive gun valve block need to be stabilized at different temperature settings. It is required that the temperature fluctuations are minimized, and the anti-interference capability is as strong as possible.

In the traditional Proportional-Integral-Derivative (PID) algorithm, it is necessary to tune and set the proportional coefficient (KP), integral coefficient (KI), and derivative coefficient (KD) for a specific controlled object [

1,

2]. The traditional approach is to determine the PID coefficients based on certain tuning rules after obtaining the mathematical model of the object. Examples of such methods include the Ziegler-Nichols method [

3,

4], the pole placement method [

5], the M-constrained Integral Gain Optimization (MIGO) tuning method [

6], the Kappa-Tau method [

7], and the Internal Model Control (IMC) tuning method [

8,

9].

However, in industrial adhesive dispensing systems, numerous controlled processes exhibit complex dynamics characterized by nonlinearity, time-varying uncertainty, and hysteresis due to their intricate mechanisms. Any variation in operational conditions may result in alterations to system model parameters, necessitating potential structural adjustments to the controller itself [

10]. Under such circumstances, previously optimized coefficients fail to maintain control system performance, necessitating real-time parameter recalibration [

11].

Consequently, conventional PID controllers demonstrate significant limitations in industrial adhesive dispensing applications, primarily manifesting as:

Challenges in achieving optimal parameter tuning

Excessive temperature overshoot

Suboptimal control precision

Prolonged convergence times

Aiming at these problems, literature [

12,

13,

14] proposed a control strategy that uses a fuzzy controller to adjust the PID parameters online. Reference [

15,

16] proposes the idea of using an improved particle swarm optimization algorithm to optimize the proportional factor in the fuzzy controller, thereby overcoming the problem of defuzzification control overly relying on expert experience. References [

17,

18,

19] proposed the idea of using the neural network’s self-learning ability to automatically adjust the parameters of the traditional PID algorithms. However, both above methods have high computational complexity, which places high demands on the computational performance of the controller and invisibly increases the production cost of equipment manufacturers.

Aiming at these shortcomings of traditional temperature control methods, an adaptive PID temperature control method is proposed in this paper. The method combines a segmented temperature control algorithm with an algorithm that has variable control coefficients based on output power. This method can reduce the overshoot and accelerate the convergence speed of the algorithm while maintaining a relatively low computational load.

Compared with the traditional PID method, under the same experimental conditions, the overshoot is reduced by 2 to 4 degrees Celsius, the convergence rate is increased by about 30%, and the temperature fluctuation range is reduced by about 0.2 degrees Celsius after interference.

2. Preliminary Studies

This section mainly introduces the temperature control scenario and the transfer function of the industrial adhesive dispensing heating system, and also provides the basic knowledge for the temperature control algorithm to be introduced later.

2.1. The Structure of Industrial Dispensing Temperature Control System

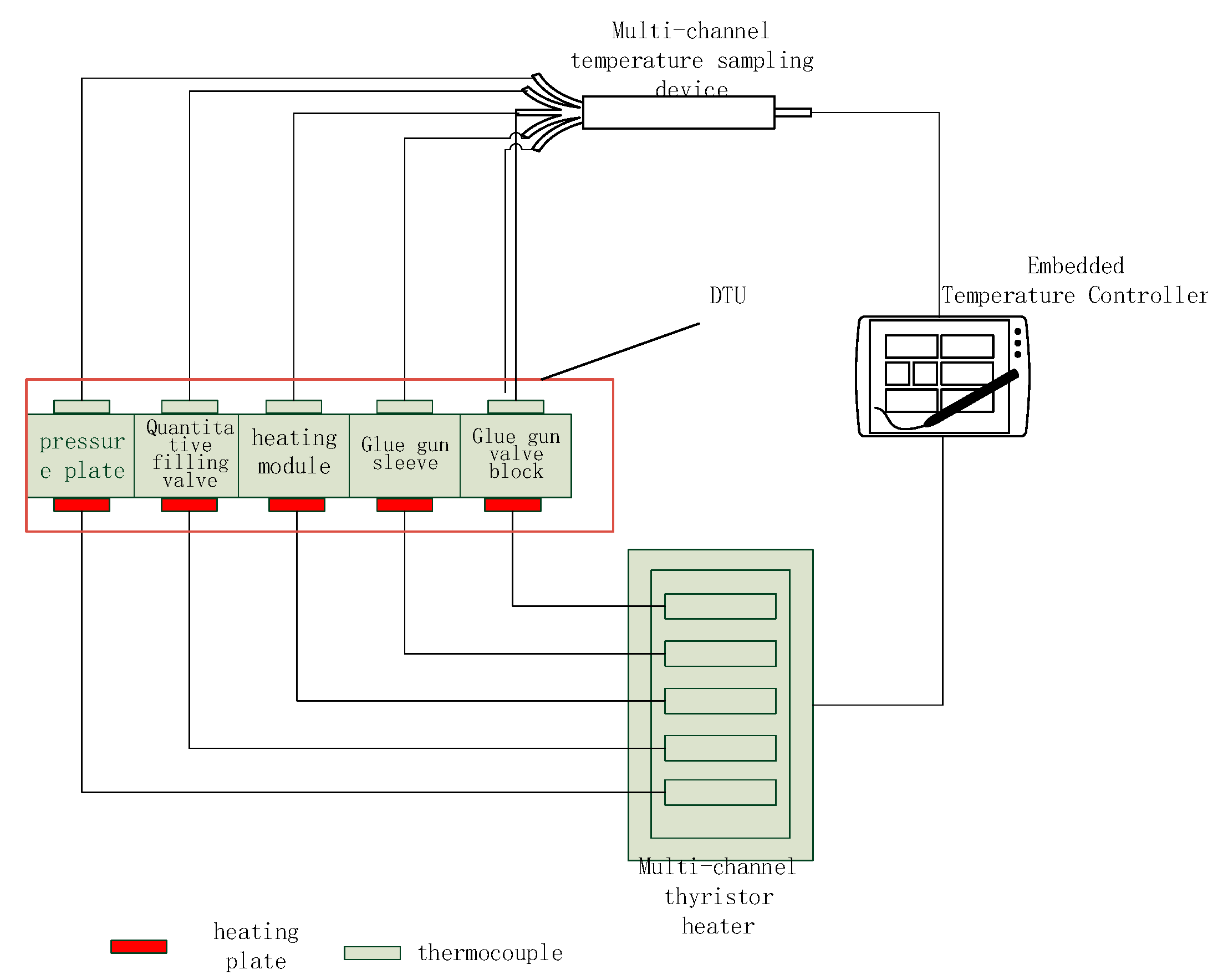

The overall structure of the industrial adhesive dispensing heating system is shown in

Figure 1. It consists of a multi-channel Thyristor Heater (TH), an Industrial Adhesive Dispensing System (IGDS), a multi-channel Temperature Sampling device, and an Embedded Temperature Controller (EC). The thyristor heater, PTC ceramic heating sheets, thermocouple Temperature Sensors (TS), and the device under test (DUT) are placed in the production site. The TH is responsible for providing heat to the DUT through the ceramic heating sheets. The TS is responsible for feeding back the heat of the DUT to the EC. The EC controls the output power of the TH through an intelligent algorithm to keep each part of the DUT at the set temperature. In the industrial adhesive dispensing system, it is required that the industrial adhesive enters from the pressure plate and passes through each component of the DUT in sequence, and gradually heating up. Finally, when the adhesive reaches the outlet of the DUT (i.e., the adhesive gun valve), the temperature also reaches the set value, thus meeting the process requirements of the industrial adhesive dispensing system.

2.2. Transmission Model of the Heating System

The industrial adhesive dispensing temperature control system uses a thyristor to output stable power, which is loaded onto the PTC ceramic heating element to heat the object being heated. Due to the different absorption efficiencies of various components and the presence of flowing adhesive materials inside the heated object, the entire heating system often exhibits nonlinear and time-delay characteristics in terms of temperature control. Therefore, the transfer function of this temperature control system should be a high-order model, which poses challenges to the design of temperature control.

Now, taking the heating module components in the system as an example, the transfer function is determined through the next experimental method.

In the experiment, the model of the temperature control system of the heating module is approximated as a First-Order Plus Dead Time (FOPDT) model, and its transfer function is shown in the following formula:

The step response method is often used to determine the transfer function of a control system. In the adhesive dispensing temperature control system, when a fixed amplitude voltage is output, the transfer function of the system can be fitted according to the temperature change curve.

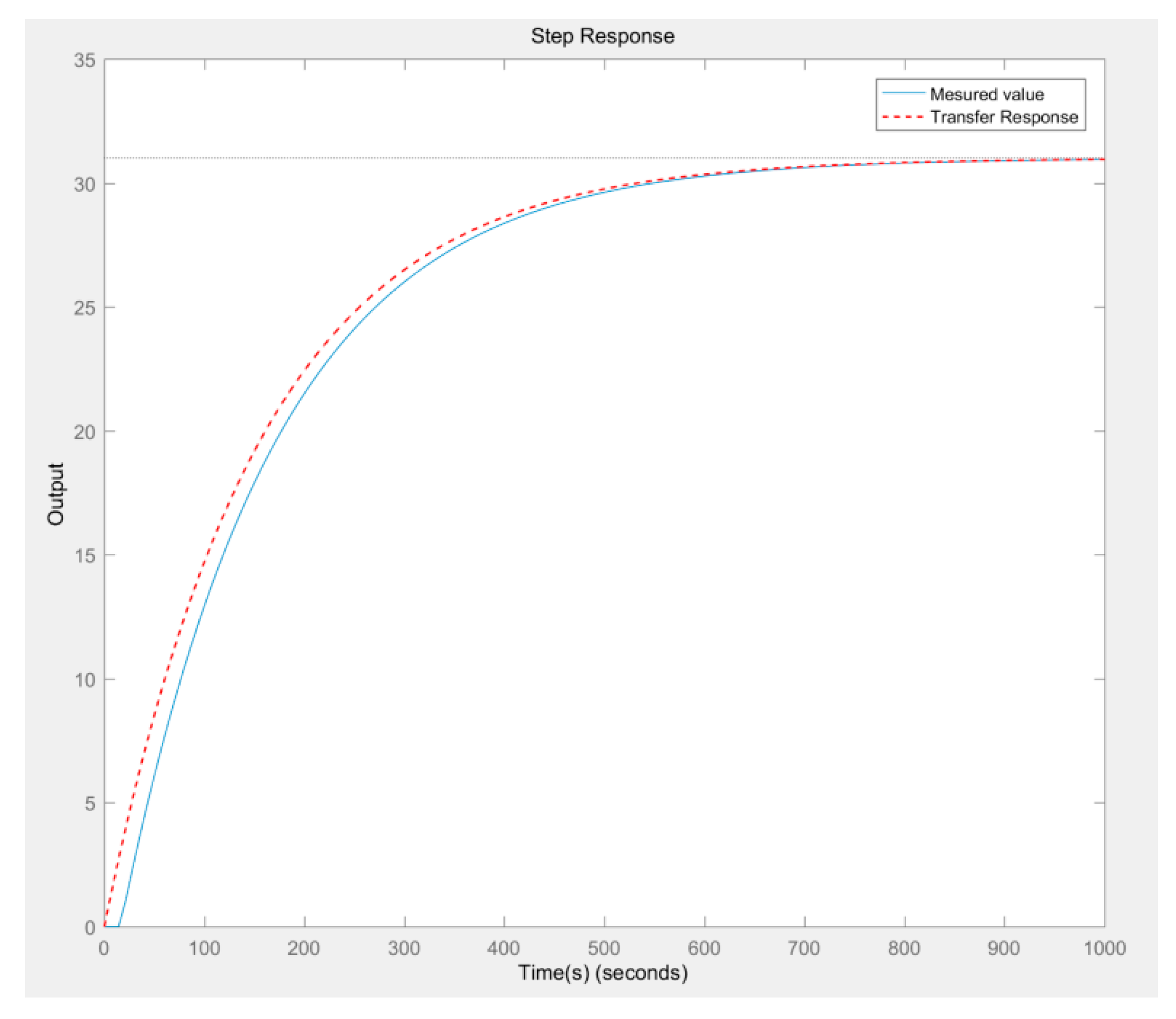

Figure 2 shows the step response temperature curve of the top surface of the Device Under Test (DUT) in the experiment. The heater is a PTC ceramic heating element, the control voltage is fixed at 5V, and the initial temperature is set as the origin of the coordinate system.

According to the FOPDT model, the step response of the temperature control system can be expressed as Equation (2) in the Laplace domain.

Here,

represents the response of the system in the Laplace domain, and

represents the Laplace transform of the control signal. The transient process of the control system in the time domain is shown in the following formula:

Here, is the amplitude of the step input, and represents the inverse Laplace transform. It can be seen from the above formula that when the condition of is met, the step response tends to .

The value of

in the transfer function can be calculated according to the following formula:

The ambient temperature is 20.5℃, and it is set as the origin of the temperature-time curve. The initial temperature value needs to be subtracted from the step response curve. According to the above principle, the calculation process of the parameter is shown in formula (5).

The calculation of

and

requires taking two known points in the system response, as shown in formula (6). The input current of the heating device is 2, and the parameters can be solved as

,

,

. Therefore, the transfer function can be expressed by the following formula:

Using the same method, we can measure the heat transfer functions of other channels. The solution process is omitted here.

3. Proposed Method: Segmented Temperature Control Algorithm

Reference [

20,

21,

22] suggests that the PID algorithm can be combined with the time-optimal algorithm. When the temperature error is greater than the threshold value, the time-optimal algorithm is used to heat the heated body at maximum power, so that it’s temperature can rise in the shortest time; when the temperature error is less than the threshold value, only the PID algorithm is used to control the output power and stabilize the temperature of the heated body. This method can reduce the overshoot of the system, but due to the different thermal inertia of different heated bodies, it is necessary to set different error thresholds for different heated bodies, otherwise it is very likely that the overshoot temperature will be too high. To prevent excessive overshoot, the literature [

23,

24] proposes the application of integral separation algorithm, using PD controller when the error is larger and PID controller when it is smaller. However, the algorithm must also set a reasonable threshold, otherwise it cannot control the overshoot. In view of the above problems, this paper proposes a segmented temperature control algorithm, which divides the PID control process into several stages, and each stage adopts different control strategies to achieve the purpose of rapid heating, rapid convergence, and small overshoot.

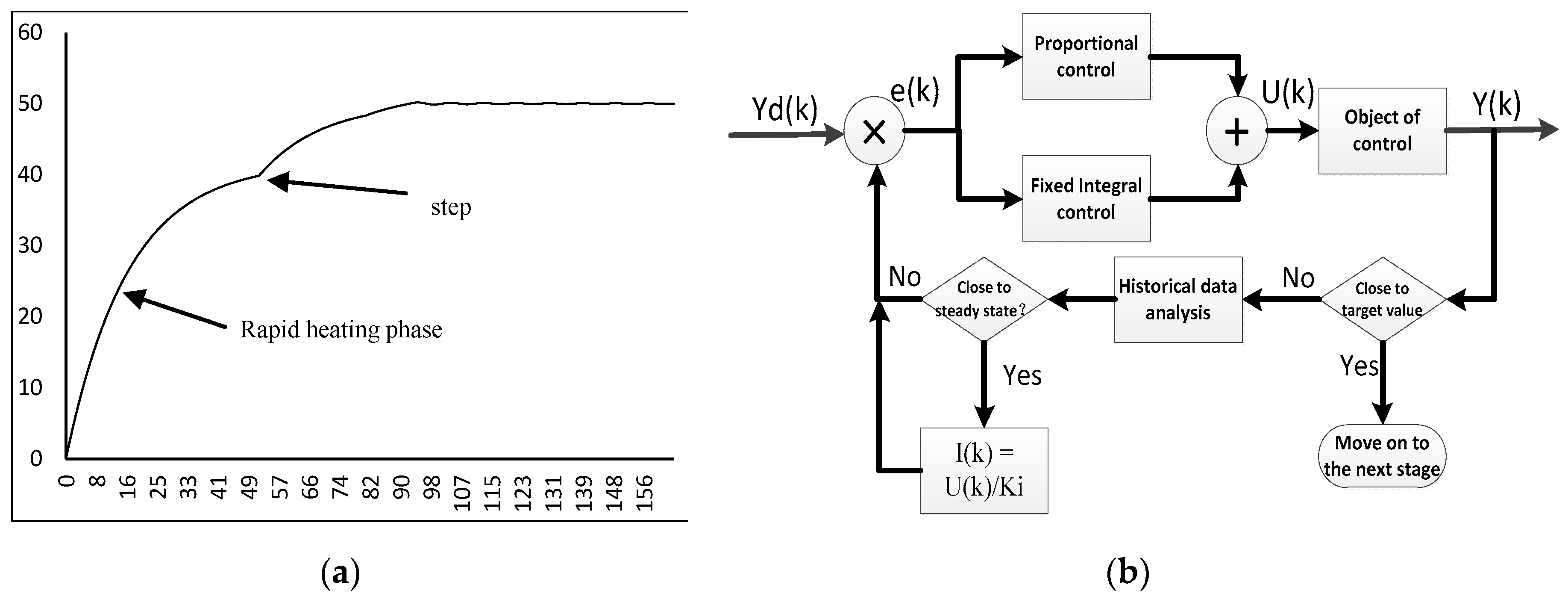

3.1. Control Strategy for Rapid Heating Phase

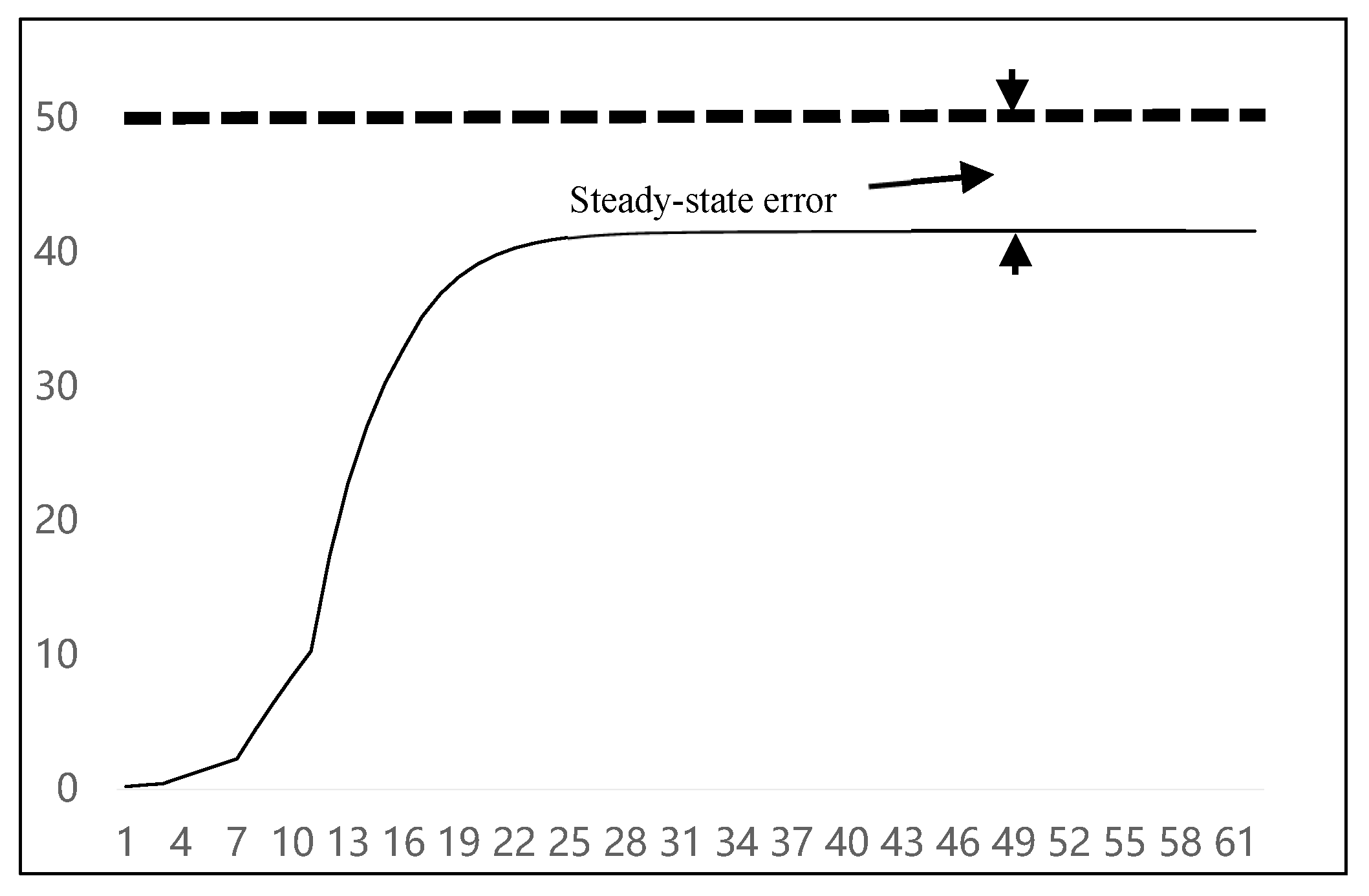

At the beginning of the heating stage, the algorithm adopts the proportional control method only. According to the magnitude of the error, the temperature control power is output proportionally. The formula is .

Where

is the output power at time k,

is the error at time

, and

is the proportional coefficient. According to PID control theory [

1,

25], when there is only proportional control, the system will quickly reach a steady state, and then there will be steady-state errors in the system. The temperature control curve is shown on

Figure 1. In the figure, we take 50° as the target temperature and only adopt the proportional control method. The horizontal axis of the figure is the sampling time, and the vertical axis is the current temperature. As can be seen from the figure, in the later stage of the temperature control process, a stable steady-state error is formed between the controlled temperature and the target temperature.

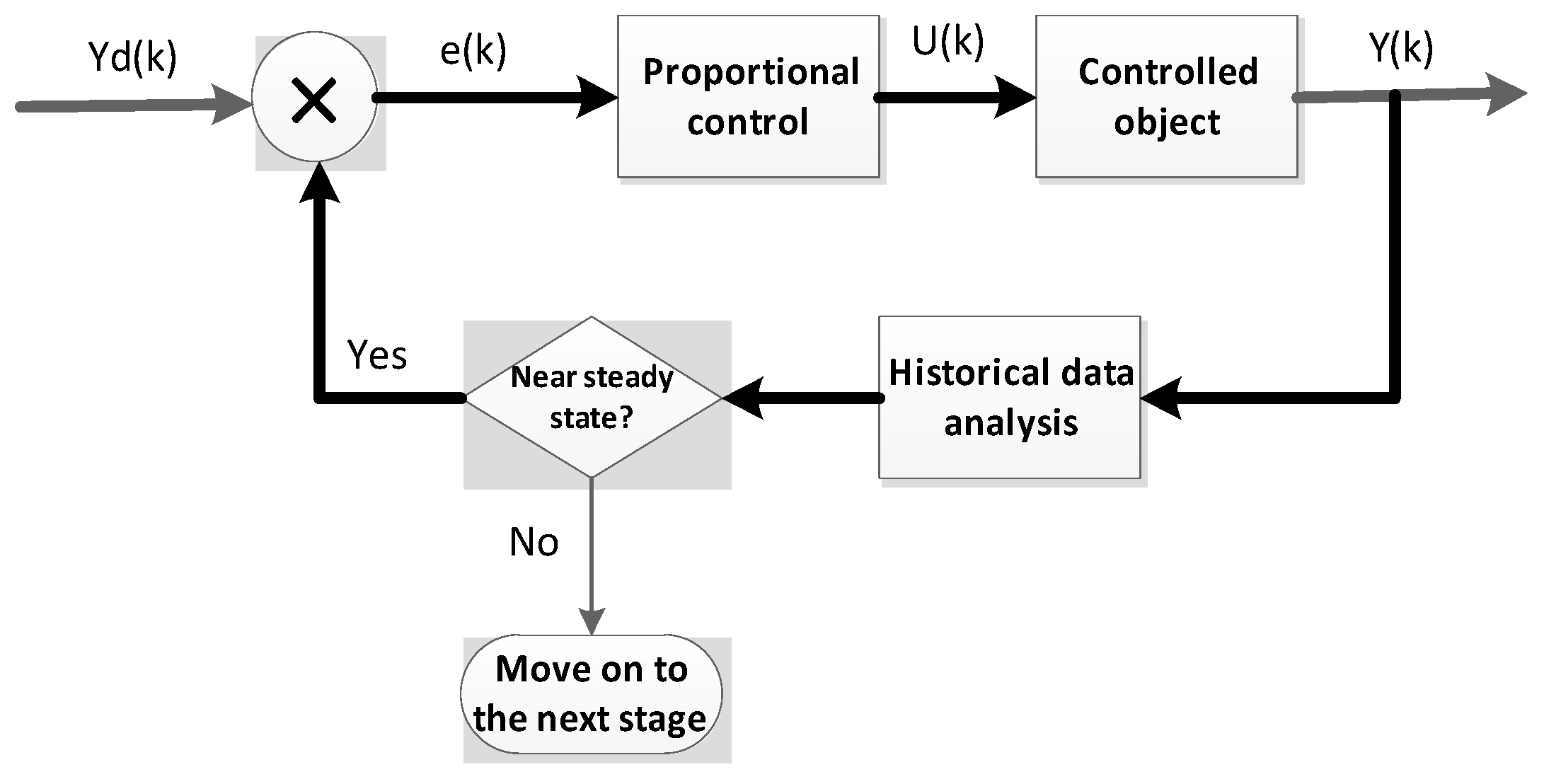

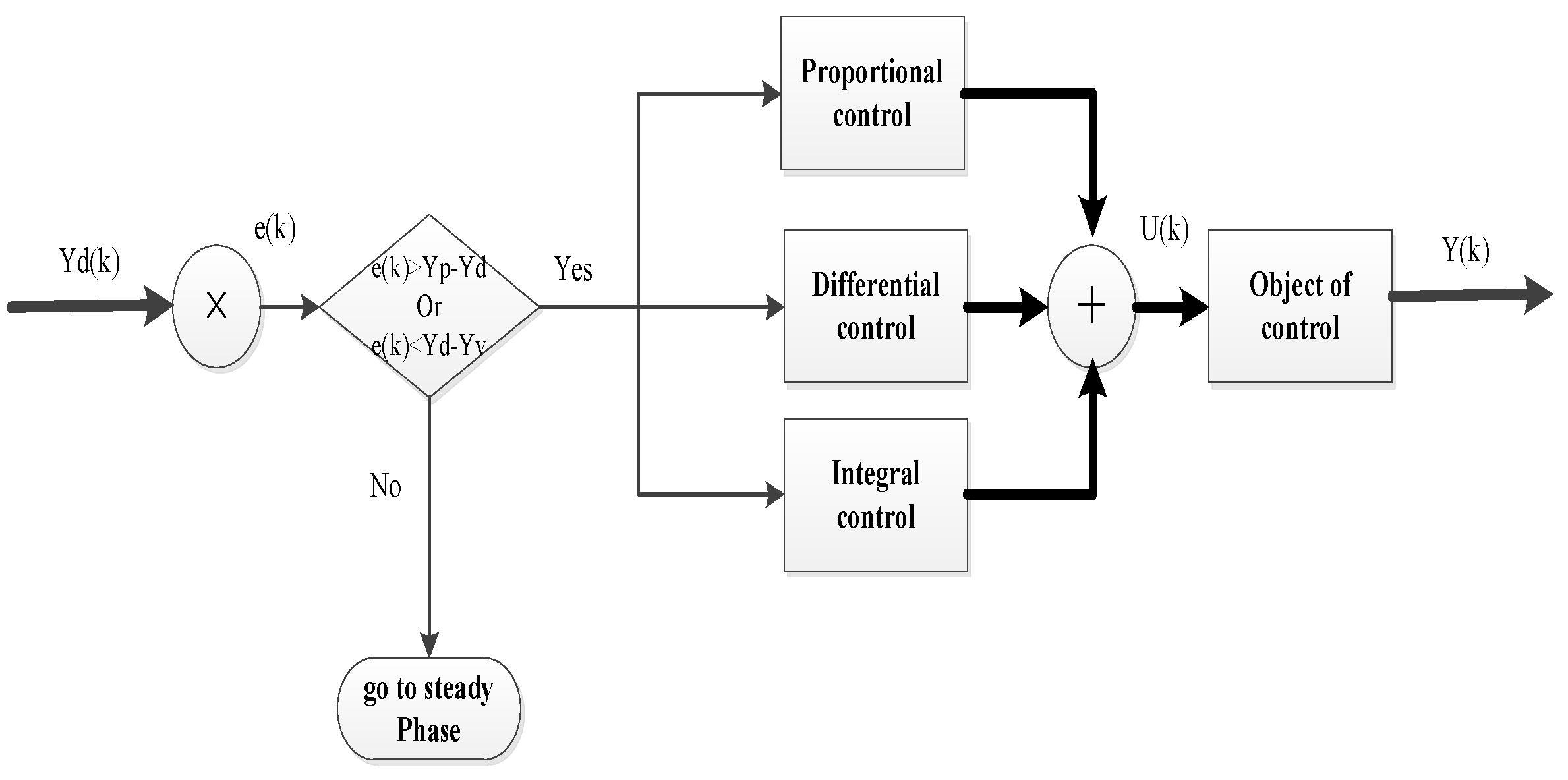

While performing proportional control, the historical data of the controlled temperature is analyzed, and according to the historical data, whether the controlled temperature is close to the steady state is judged. When the controlled data is found to be close to the steady state, the control program can enter the second stage. The control flow chart for this phase is shown in

Figure 3

In

Figure 4,

is the target temperature,

is the current temperature of the heated object at time

,

is the error at time

, and

is the output power at time

.

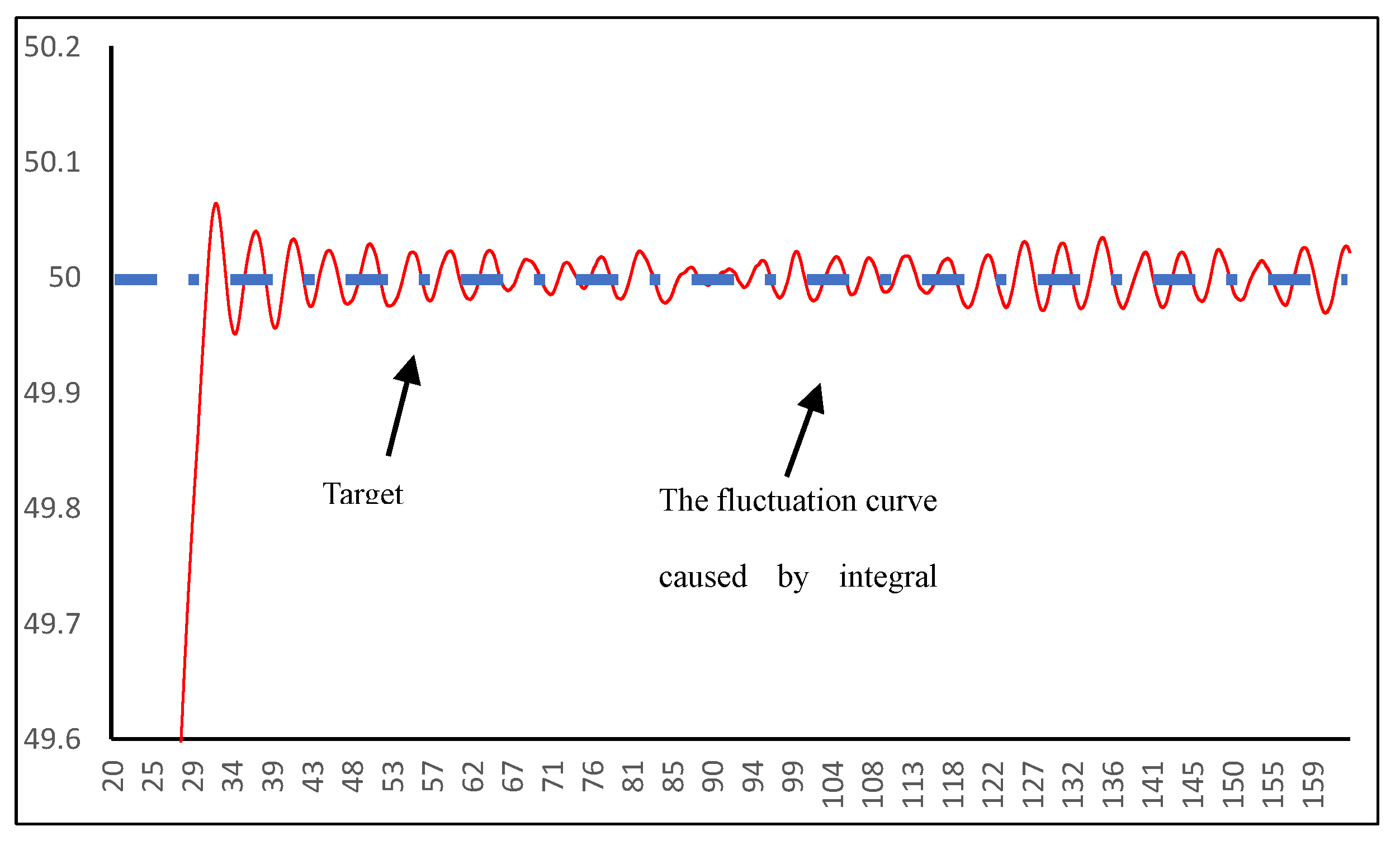

3.2. Control Strategy for Pre-Steady Phase

In the rapid heating phase, as the error decreases, the output power of the system becomes smaller and smaller, gradually approaches the heat loss of the heated object. Currently, the heated object is close to the thermal equilibrium state, so the temperature curve also enters or approaches the steady state. After that, if we want to continue increasing the temperature, we need to add integral control to increase the output power. However, it is easy to cause significant overshoots because of integral excessive. To avoid this phenomenon, in the pre-steady state phase, we set the integral value to a fixed value, which is the ratio of the output power to the integral coefficient at the end of the previous steady state (Equation 8). The output power control formula is changed to a PI model with a fixed integral value. To avoid this situation, we set the integral value to a fixed value in the pre-steady phase, which is the quotient of the output power at the end of the rapid heating phase and the integral coefficient, which can be obtained from equation

. And then, the output power control formula is changed to PI mode with a fixed integral value.

In the formula,

is a fixed integral value,

is the integral coefficient, and

is the output power at the end of the previous phase. The purpose of this is to replace the function of the previous proportional control with constant integral control, and the proportional term continues to increase the power output based on the error between the current temperature and the target temperature. Then, the output temperature will quickly enter a new steady-state phase. If we repeat the previous process, the temperature curve will become a stepped image, When the error approaches the required accuracy of the system, the control program can enter the next phase. The controlled temperature curve of this phase is shown in

Figure 5a. The control flow chart of this phase is shown in

Figure 5b.

This strategy effectively eliminates the phenomenon of excessive integration, avoids excessive overshoot, and ensures the speed of temperature rise.

In this phase, the current temperature value will be continuously monitored. If the current error has approached the required accuracy of the system, the system will enter the steady-state phase.

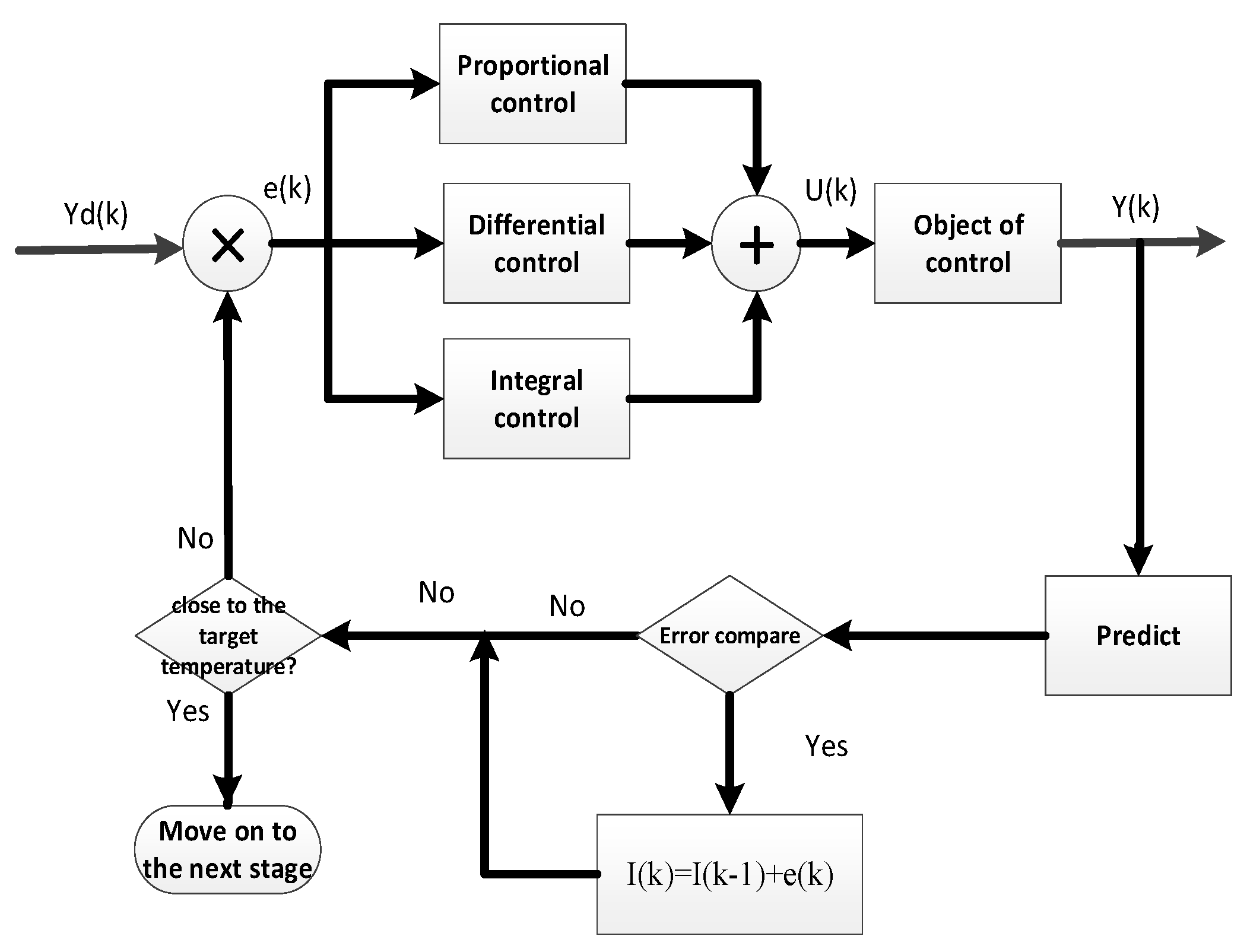

2.3. Control strategy for Steady-State Phase

In the steady-state phase, the temperature of the heated object has nearly reached the target value. At this stage, incorporating dynamic integral control will not result in excessive overshoot, and adding derivative control will further minimize the oscillation of the output power. The temperature control strategy at this time is depicted in Equations 9, 10, and 11.

Here,

is the differential value at time

,

is the differential coefficient, and

is the integral value at time

. At this phase, the integration effect will become the main force in regulating the output power, but due to the time-delay characteristic of the integration effect, the temperature control curve will fluctuate around the target value.

Figure 6 shows the amplified effect of this phase.

For overcome the problem of system time delay, we can rely on the transfer function (equation 7) to predict the output state of the system, and take measures in advance according to this predicted value to control the change of the integral value, so as to achieve the purpose of stabilizing the system output.

In order to predict the system state, we need to perform a Z-transform on the transfer function (Equation 7), and the discretized transfer function after the transformation is Equation 12

This equation can be transformed into Equation 13.

Furthermore, we can transform this equation into a difference form.

Equation 14 can be used to predict the output state of the system in the next cycle. At this time, we can adopt the following strategy to control the magnitude of the integral value in the PID control in advance: If the predicted error in the next cycle has the same direction as the error in this cycle and the absolute value becomes smaller, then stop executing Equation 10. At this moment, the integral value will no longer change, and the system output will depend on the effect of the proportional control part. If the directions of the two errors are different, or if they are in the same direction but the absolute value of the error in the next cycle is greater than or equal to that of the error in this cycle, then continue to execute Equation 10. At this time, the system output will mainly depend on the effect of the integral control.

This adaptive strategy effectively mitigates integral hysteresis effects while accelerating transient convergence rates. However, system stability tends to be compromised under such dynamic conditions. To enhance regulatory precision, the system may transition to the subsequent control phase characterized by refined parameter adjustments. The corresponding control logic diagram for this advanced phase is illustrated in

Figure 7.

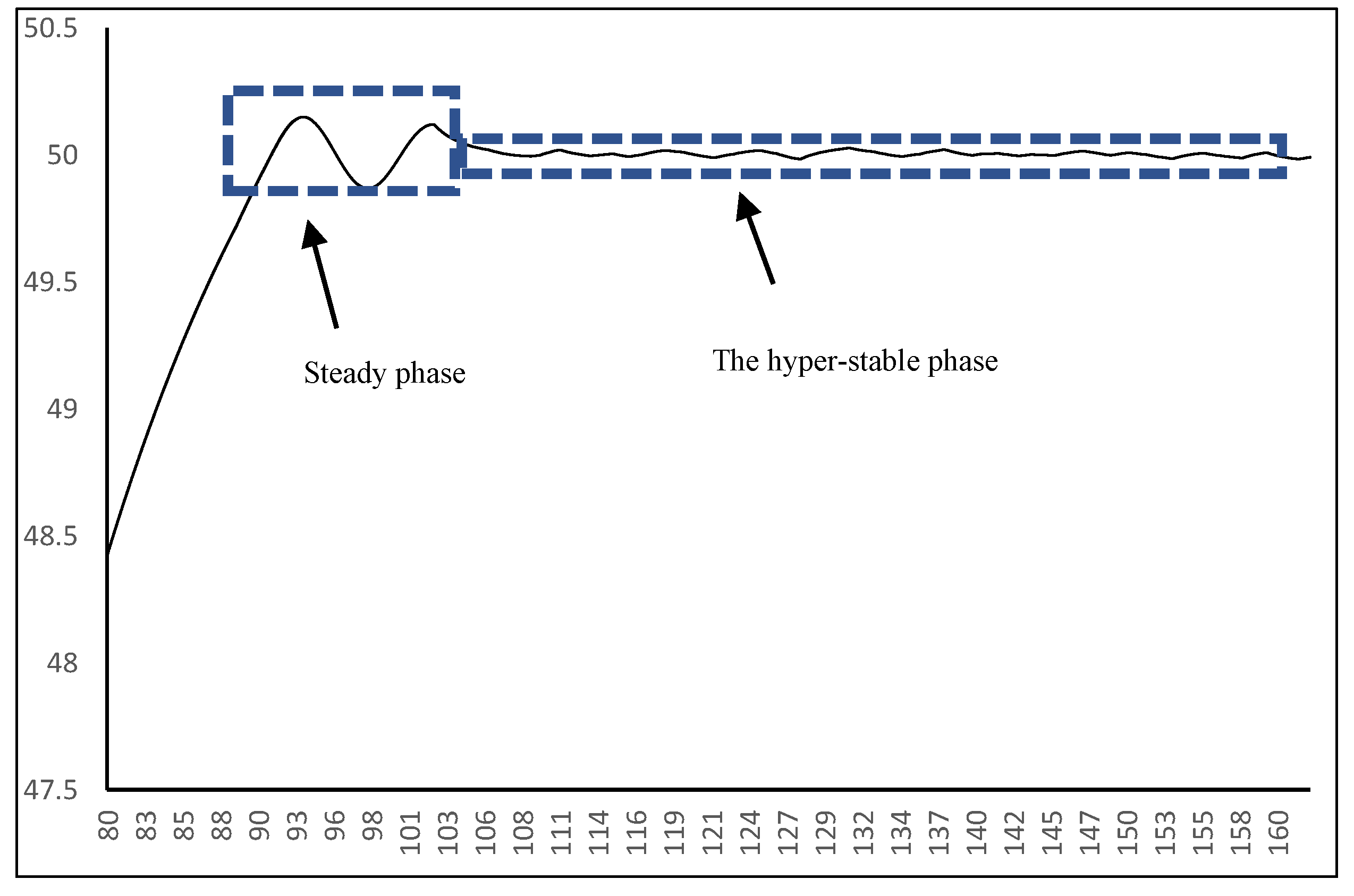

3.4. Control Strategy of Super-Stable Phase

According to the analysis in the previous section, the time delay of the integration effect is one of the reasons for the oscillation of the output power of the standard PID controller. The external environment of the temperature control system is usually stable, so the time delay of integration effect becomes the main reason to affect temperature control accuracy.

Therefore, this paper proposes a super-stable control strategy to overcome the delay effect of integration effect: When the system enters steady state, the integral value is fixed at the average value of the peak and valley moments. Then the output power of the system is only affected by proportional control and differential control, while integral control is responsible for providing constant base power. Building on the theoretical foundation established above, the output power control is formulated using equations 15, 16, and 17, where

is the integral value at the peak moment and

is the integral value at the valley moment.

If the system is not disturbed, the control effect will be as shown on

Figure 8. When the system is disturbed (such as wind disturbance, external temperature disturbance, etc.), the system will experience significant fluctuations again, and the absolute error value will be greater than the amplitude of the current peak and valley. At this time, the system can exit the super-stable control phase and return to the steady-state control phase.

So, the complete control flow of this phase is shown in

Figure 9, where

represents the temperature at peak time and

represents the temperature at valley time.

3. Variable Proportional Coefficient Control Based On Output Power

Industrial adhesive application system requires not only rapid convergence and high precision but also good anti-interference performance. This means that when disturbances occur, temperature fluctuations should be minimal, and the temperature should quickly re-converge. And the system should have a wide range of applicable parameters and be easy to use and adjust. To meet this requirement, a variable coefficient PID control algorithm based on output power is proposed in this paper. This method correlates the coefficient of traditional PID controllers with the output power of temperature control system. Ensure that the system can respond to disturbances in a short period of time, while avoiding excessive oscillations due to overly large coefficients. To achieve this goal, this article adds a scaling factor α to the PID formula and relates the integral value to the output power ratio of adjacent two sampling periods to adjust the sensitivity of the integral effect; Increase the scaling factor

to adjust the sensitivity of the proportional control effect. Now, the temperature control formula is shown in equations 18-22, where

in equation 14 and

in equation 16 are adjustable coefficients that can be adjusted appropriately according to the system resolution.

In the formulas, is the output power generated by integral control, is the integral value adjusted by factor , is the adjusted integral coefficient, and is the proportional coefficient adjusted by . According to the above formulas, when the steady-state system is disturbed and the output power increases, a larger proportional coefficient and integral value will be obtained, than changing the sensitivity and strength of the integral control. The difference between this control method and fuzzy PID is that fuzzy PID adjusts the values of PID parameters based on a pre-set fuzzy rule library, errors, and error change rates 19. While the method in this article adjusts PID parameters based on the output power to ensure that the PID adjustment effect is neither too extreme nor too slow. Compared to fuzzy PID, the method proposed in this paper has smaller computational complexity and more sensitive response.

4. Experiment Results and Discussion

In this section, real heating tests of the adhesive application system were carried out to verify and confirm the algorithm. Meanwhile, the performance of this algorithm was compared with the PID adjustment method based on integral anti-windup, so as to verify the performance of the method proposed in this paper in terms of overshoot, oscillation period, response time, and the applicable range of parameters.

4.1. Experiment Setting

In this experiment, a closed-loop temperature control system was developed for an industrial adhesive dispensing system. The heated assembly consists of a series-connected arrangement including a pressure plate, metering machine filling valve, heating module, adhesive gun copper sleeve, and valve block. The industrial adhesive flows sequentially through these components, each of which is equipped with a T-type thermocouple. These thermocouples are then interfaced with an external temperature acquisition unit to monitor the real-time surface temperatures of the components under test.

The control system employs a microcontroller - centric embedded platform based on the STM32F407. This system generates Pulse - Width Modulation (PWM) signals with adjustable duty cycles to regulate the switching state of a thyristor power controller, thereby modulating the power delivered to the heating elements.

A 6 - channel temperature acquisition module with 1 kS/s (kilo - samples per second) sampling rate is integrated. This device maintains ±0.1°C measurement accuracy across the operational temperature range of -100°C to 400°C.

The embedded controller manages two primary functions: performing multi - channel thermocouple data acquisition, and calculating the required output power using the proprietary control algorithm described in this paper.

The experimental firmware is implemented in the C language, consisting of three core components: a temperature acquisition module, a temperature control algorithm implementation, and an output power regulation module.

Primary attention is focused on the heating module's temperature profile. The temperature control experiment commences once the module temperature stabilizes below 10°C. The test protocol requires cyclically adjusting the device under test's surface temperature between 30°C and -100°C. To ensure equipment safety, a 15V input voltage ceiling is imposed on each heating element. Accordingly, the proposed algorithm restricts output voltage to 0-15V. Through voltage-to-duty-cycle conversion, this corresponds to a PWM output range of 0-80%. At 0% duty cycle, heat dissipation occurs primarily via gray-body radiation from the tested components.

4.2. System Response Speed Comparison Test

Now we compare the differences in overshoot, oscillation period, response time, and parameter applicability between this method and the integral limited PID algorithm on the same hardware device.

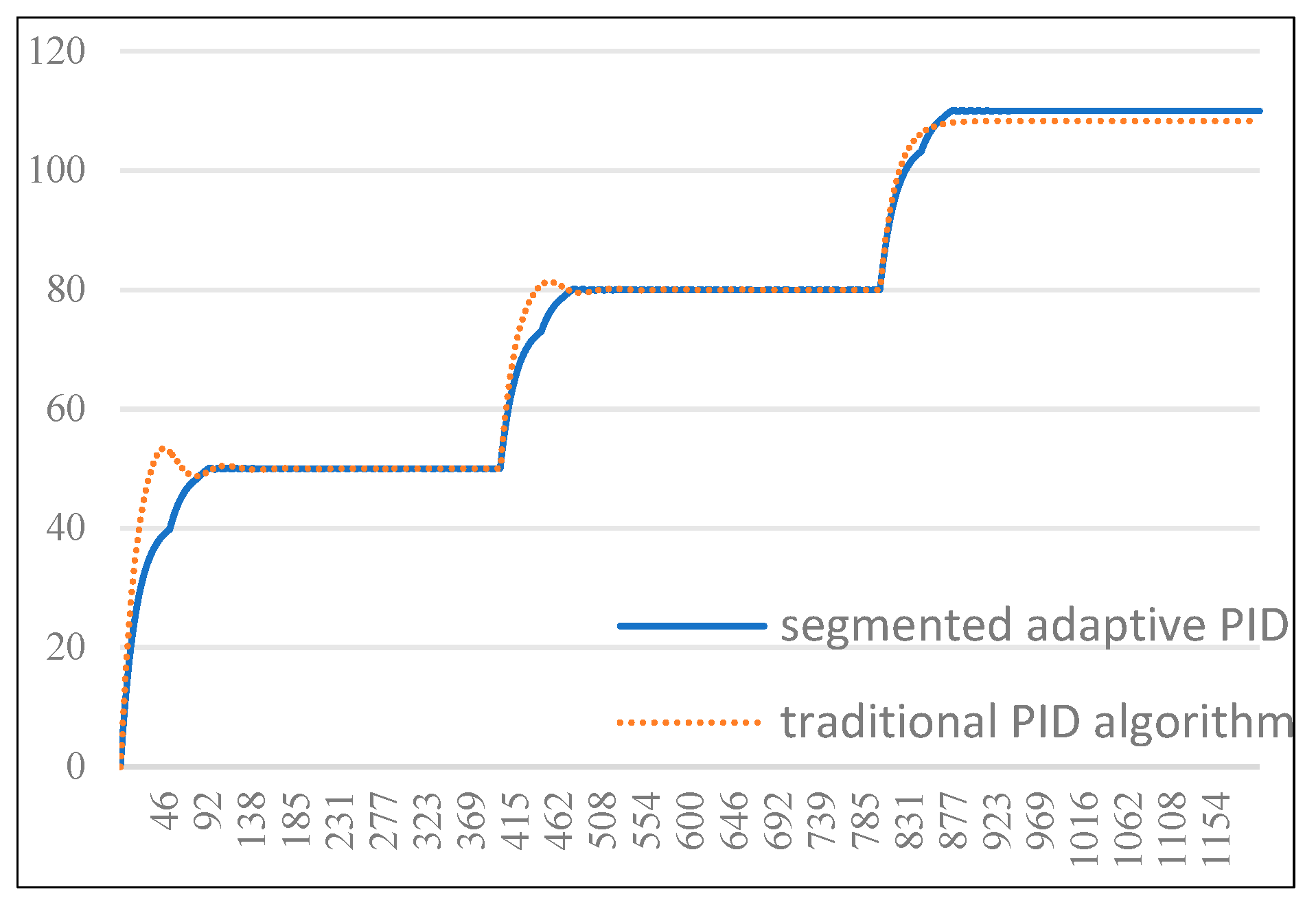

First, we carry out heating experiments to compare and verify the heating effect from 0 degrees to 50 degrees from 50 degrees to 80 degrees and from 80 degrees to 110 degrees, in which the traditional PID algorithm limits the maximum value of the integral value to 80, while the method in this paper has no limit on the PID integral value. The results are shown in

Figure 10.

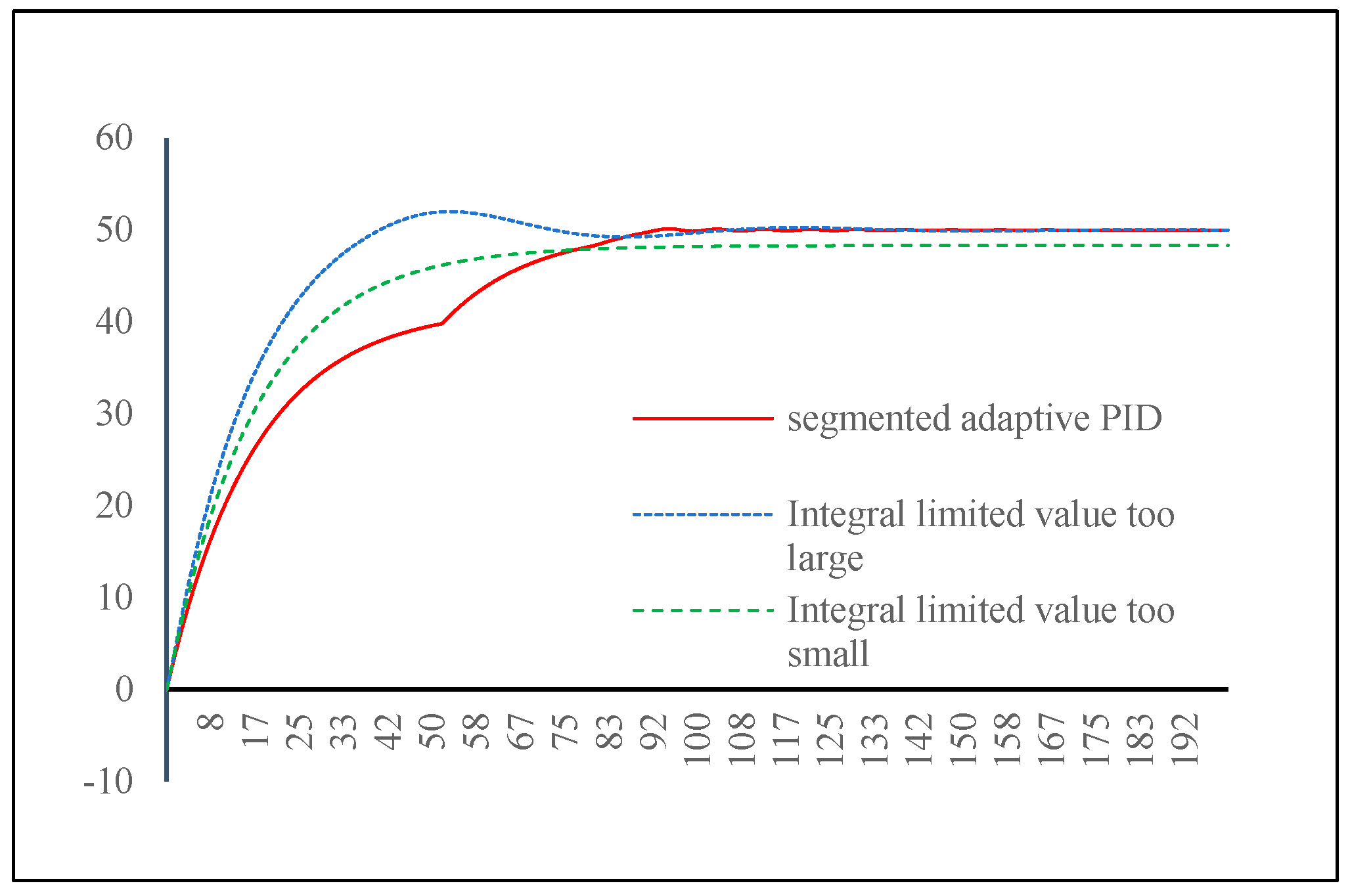

Then, the integral limit values of the traditional PID algorithm were set to 80 and 50, respectively, and the effect of heating the target from 0 degrees to 50 degrees was compared with the method proposed in this paper. The results are shown in

Figure 11.

From the comparison results of the two figures, the overshoot of the method proposed in this paper is not significantly different at any output power and is smaller than that of the traditional PID algorithm. At the same time, there is no obvious oscillation phenomenon after completing the heating process. The overshoot of traditional PID algorithm is directly related to the value of integral limited value and the heating power. When the value of the integral limit matches the heating power, the overshoot is appropriate. When the value of the integral limit is too small, the heating speed of the system is significantly too slow, and there may even be steady-state errors. When the integral limit value is too large, there will be a significant overshoot phenomenon. Therefore, traditional PID algorithms rely heavily on prior experience in terms of heating speed and convergence speed, while the method proposed in this paper has stronger adaptability.

4.3. Anti-Interference Performance Test

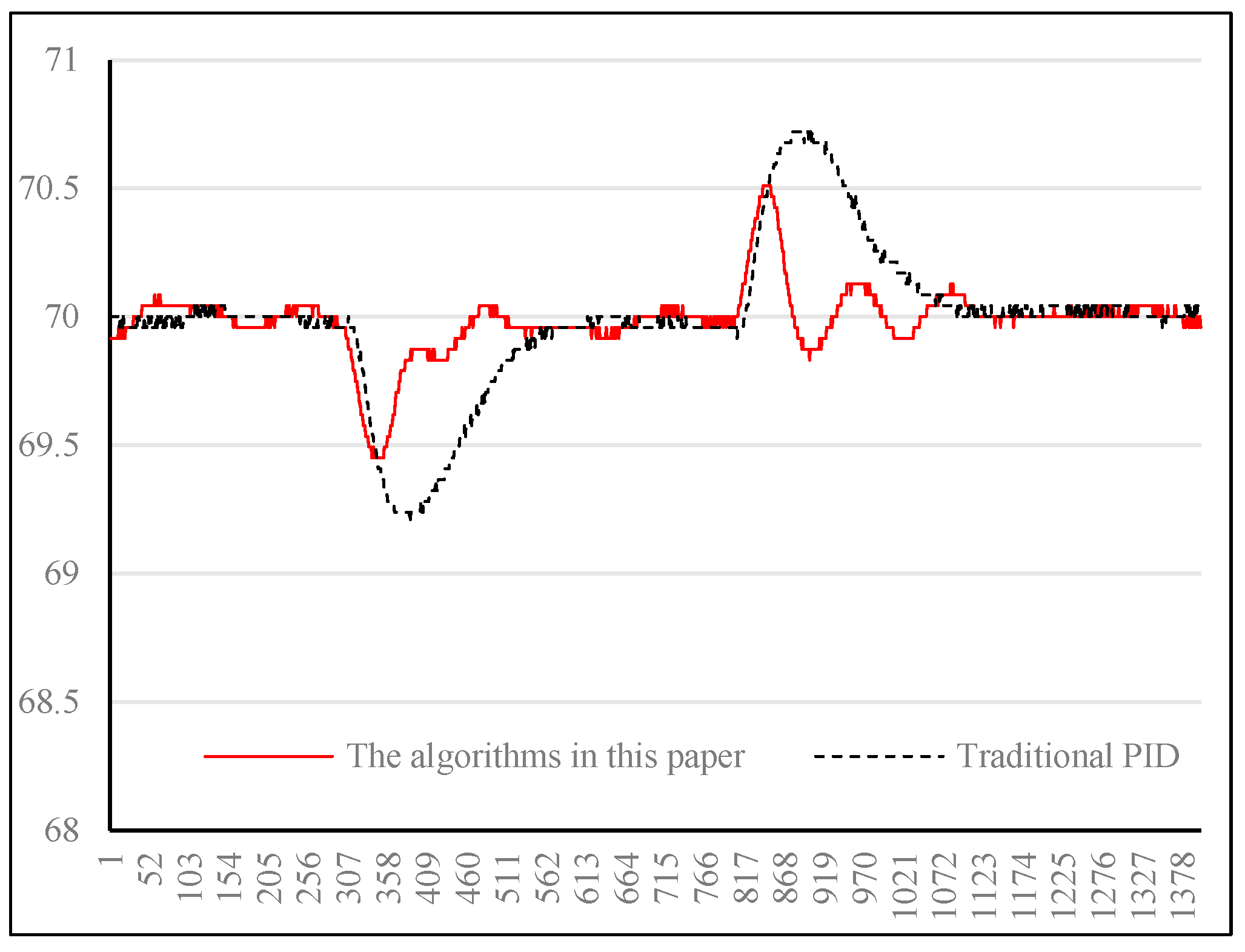

In the experiment, in order to test the anti-interference performance, when the temperature of the heated object is stable at 70°C, we blow the heated object directly with a fan. After the temperature of the heated object stabilizes, the fan is turned off to simulate sudden changes in ambient temperature. We measure the amplitude and convergence rate of temperature changes of the heated object under two methods. The experimental results are shown in

Figure 12.

From the comparison in the figure, the maximum error of the method proposed in this paper after interference is about 0.5 degrees, and the error converges to 0.2 degrees after 100 sampling periods; The maximum error of traditional PID after interference is about 0.8 degrees, and the error converges to 0.2 degrees after 200 times sampling periods. The method proposed in this article is superior to traditional PID control methods in both interference amplitude and convergence speed.

5. Conclusions

The industrial adhesive application system has many heated components, with variable heating target temperatures and significant differences in thermal inertia of the heated objects. The working environment is also affected by various interference factors. Usually, to meet the temperature control requirements of the system, complex temperature control algorithms such as fuzzy PID controller, BP neural network PID algorithm, etc. are often required. These algorithms either require a large amount of expert experience or have high computational complexity, which increases the manufacturing cost of the equipment. In response to these issues, this article proposes a new adaptive PID control method which combines a segmented temperature control algorithm with a variable control coefficient PID algorithm based on output power. The algorithm eliminates the dependence on expert experience and has simple calculations, which reduces the cost of equipment manufacturing. The method has been used well in production practice, and the temperature control accuracy can be controlled within 2 to 3 times of the measurement accuracy of the system. Under the same experimental conditions, compared with the traditional PID algorithm, the proposed method can reduce the overshoot by 2 to 4℃, increase the convergence speed by about 30%, and reduce the temperature fluctuation range by about 0.2℃ after interference. At the same time, the algorithm does not require operators to perform complex PID coefficient tuning operations.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.G. and W.S.Z.; methodology, Y.G.; software, Y.G.; validation, Y.G. and W.S.Z.; formal analysis, W.S.Z.; investigation, Y.G.; resources, W.S.Z.; data curation, Y.G.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.G.; writing—review and editing, W.S.Z.; visualization, Y.G.; supervision, W.S.Z.; project administration, Y.G.; funding acquisition, W.S.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work is supported by Tianjin Science and Technology Plan Projects (23YDTPJC00890). Key Laboratory Project of Optoelectronic Information Technology, Ministry of Education (2023KFKT018).

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- K. H. Ang, G. Chong, and Y. Li, “PID control system analysis, design, and technology,” IEEE Trans. Control Syst. Technol., vol. 13, no. 4, pp. 559–576, Jul. 2005.

- Zhang, P.; Yuan, M.; Wang, H. Self-Tuning PID Based on Adaptive Genetic Algorithms with the Application of Activated Sludge Aeration Process. 2006 6th World Congress on Intelligent Control and Automation. LOCATION OF CONFERENCE, ChinaDATE OF CONFERENCE; pp. 9327–9330.

- Ziegler, J.G.; Nichols, N.B. Optimum Settings for Automatic Controllers. J. Fluids Eng. 1942, 64, 759–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Åström, K.; Hägglund, T. Revisiting the Ziegler–Nichols step response method for PID control. J. Process. Control. 2004, 14, 635–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.-G.; Zhang, Z.; Astrom, K.J.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Y. Guaranteed Dominant Pole Placement with PID Controllers. IFAC Proc. Vol. 2008, 41, 5842–5845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahiri, M.; Ranjbar, A.; Karami, M.R.; Ghaderi, R. New tuning design schemes of fractional complex-order PI controller. Nonlinear Dyn. 2016, 84, 1813–1835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gude, J.J.; Kahoraho, E. Kappa-tau type PI tuning rules for specified robust levels. IFAC Proc. Vol. 2012, 45, 589–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selvi, J.A.V.; Radhakrishnan, T.; Sundaram, S. Performance assessment of PID and IMC tuning methods for a mixing process with time delay. ISA Trans. 2007, 46, 391–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nath, U.M.; Dey, C.; Mudi, R.K. Review on IMC-based PID Controller Design Approach with Experimental Validations. IETE J. Res. 2021, 69, 1640–1660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Yang, M. Comparison of auto-tuning methods of PID controllers based on models and closed-loop data. 2014 33rd Chinese Control Conference (CCC). LOCATION OF CONFERENCE, ChinaDATE OF CONFERENCE; pp. 3661–3667.

- Sanchez-Palma, J.; Ordonez-Avila, J.L. A PID Control Algorithm With Adaptive Tuning Using Continuous Artificial Hydrocarbon Networks for a Two-Tank System. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 114694–114710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Lu, G.; Su, J.; Hou, T.; Huang, F.; Pan, Y. Improved Particle Swarm Fuzzy PID Temperature Control for the Pellet Grills. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 66373–66381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, J.; He, Z.; Wang, W.; Li, B.; Yang, G. Fuzzy control of temperature in gas flow control system based on mixed cold and hot gases. Int. Commun. Heat Mass Transf. 2023, 148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Zhou, L.; Li, Y.; Huang, Y.; Li, A.; Long, J.; Luo, C.; Li, C. Dynamic fuzzy temperature control with quasi-Newtonian particle swarm optimization for precise air conditioning. Energy Build. 2024, 310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Du, S.; He, Y.; Liang, M.; Xu, D. Robust model predictive control for greenhouse temperature based on particle swarm optimization. Inf. Process. Agric. 2018, 5, 329–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- X. Pei, J. Zhang, W. Jia, D. Han, S. Ma and B. Xu, "Research on Junction Temperature Control Method of LED Array,"2024 4th International Conference on Electrical Engineering and Mechatronics Technology (ICEEMT), Hangzhou, China, 2024, pp. 166-170. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X.; Cheng, T. Design of a BP neural network PID controller for an air suspension system by considering the stiffness of rubber bellows. Alex. Eng. J. 2023, 74, 65–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanna, Y.F.; Khater, A.A.; El-Bardini, M.; El-Nagar, A.M. Real time adaptive PID controller based on quantum neural network for nonlinear systems. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2023, 126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Gao, L. The Brushless DC motor control system Based on neural network fuzzy PID control of power electronics technology. Optik 2022, 271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vlad Mureșan,Mihail Abrudean and Mihaela-Ligia Ungureșan,“Intelligent Temperature Control in an Industrial Furnace”, ICCAE 2020: 2020 12th International Conference on Computer and Automation Engineering Sydney NSW Australia February 14 - 16, 2020.

- Zhaojun Xu, Junxia Liu,“Research on Temperature Control of Liposome High Pressure Homogenizer Based on Genetic Algorithm Optimization PID”, Procedia Computer Science, Volume 208, 2022, Pages 330-337.

- Corradini, L.; Costabeber, A.; Mattavelli, P.; Saggini, S. Parameter-Independent Time-Optimal Digital Control for Point-of-Load Converters. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2009, 24, 2235–2248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, K.; Xie, Y.; Wang, C.; Yan, J.; Shi, Y.; Guo, J.; Guo, J. Application of the fuzzy proportional integral differential (PID) temperature control algorithm in a liver function test system based on a centrifugal microfluidic device. Talanta 2023, 268, 125330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, Y.; Yin, S.; Zhao, Y.; Chen, Y.; Wan, F. Research on the Control Strategy of Battery Roller Press Deflection Device by Introducing Genetic Algorithm to Optimize Integral Separation PID. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 100878–100894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frank, P.; Heger, F.; Heintz, T.; Härtel, H. Computer Aided Adjustment of PID Control for Steam Turbines. IFAC Proc. Vol. 1979, 12, 573–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buzruk, M.; Ghogare, S.; Deshpande, A. A Novel Maximum Power Point Tracking Control Without Steady State Oscillations Using Extremum Seeking Control Algorithm. 2021 Seventh Indian Control Conference (ICC). LOCATION OF CONFERENCE, IndiaDATE OF CONFERENCE; pp. 259–264.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).