1. Introduction

The oceans, which represent more than 70% of the total surface of the planet [

1], the exploitation of the resources they contain, and the various uses we make of their surface are fundamental to humanity and will be even more so in the future. For this, it is necessary to achieve sustainable use of resources and effective management of space usage. Spatial planning is a key tool to achieve this.

Marine Spatial Planning (MSP) [

2] is the process currently followed by the Intergovernmental Oceanographic Commission of UNESCO (IOC UNESCO) [

3] and the Directorate-General for Maritime Affairs and Fisheries (DG MARE) [

4] of the European Commission to address the sustainable and safe exploitation of ocean resources, as well as to ensure compatibility of uses among different sectors through sustainable governance. This is in line with the Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) of the 2030 Agenda [

5], with the support of national and regional initiatives within the framework of the United Nations Decade of Ocean Science for Sustainable Development and Ecosystem Restoration [

6]. MSP also proves to be a very useful tool for planning the objectives of the High-Level Panel for a Sustainable Ocean Economy [

7], which is communicated in its "Call to Action" [

8] and described in its Agenda with results for 2030 and 2050.

The Marine Spatial Planning (MSP) process is a broad and strategic approach that, from an ecosystem-based perspective, analyzes and assigns temporary uses to specific ocean areas to minimize conflicts between human activities and maximize benefits, while ensuring the resilience of marine ecosystems.

The broad and strategic process covers the following areas:

Ecosystem management, Marine Protected Areas, Renewable Energy Sites, Sustainable Fisheries, Cumulative Effects, Aquaculture Sites, Ecosystem Services and Natural Capital, Climate Change, Transboundary Aspects, Blue Economy, Ocean Conservation Debt Swaps, the High Seas and Areas Beyond National Jurisdiction (ABNJ) (2/3 of the ocean), Food Security, Seabed Resource Extraction, and their uses.[

9]

Coastal zones are of particular interest. These areas are where the land-sea interaction occurs, with their specific issues, and where a significant portion of the population is concentrated in coastal cities, 50%, according to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) [

10] and Platform for Climate Change Adaptation in Spain, MITECO [

11].

Considering the land-sea interaction, the population residing in coastal cities, and the effects of climate change, it becomes clear that this zone, the coastal strip, is a highly sensitive and impactful area for the population. The urbanization of coastal cities, governed by land-use planning, is creating static urban development "turned away from the sea." This means the consideration of the sea's influence is limited to the public maritime domain band that must be respected and is outside the scope of Terrestrial Spatial Planning (TSP).

Traditionally, land space planning and marine space planning have been carried out independently, resulting in uncoordinated approaches and often conflicting uses. However, the growing awareness of the interdependence between terrestrial and marine ecosystems has driven the need for integrated and holistic planning.

Currently, there is no clear methodology for conducting integrated planning. The objective of this article is to propose a methodology for conducting the afore-mentioned integrated planning, which, based on the state of the art of MSP and TSP, establishes clear criteria for the steps to follow in the development of the proposed tool.

In defining the methodology, the aim has been to avoid reliance on developments made by specific countries. This was easier to accomplish in the case of MSP since its methodology is widely generalized and coordinated by IOC UNESCO (155 countries), so it has been taken as a reference. It has been more complicated to avoid specific references to countries in the case of TSP, as, although its definition includes many globally accepted concepts, when trying to "ground" certain definitions with a high degree of precision, one must resort to concrete examples from specific countries.

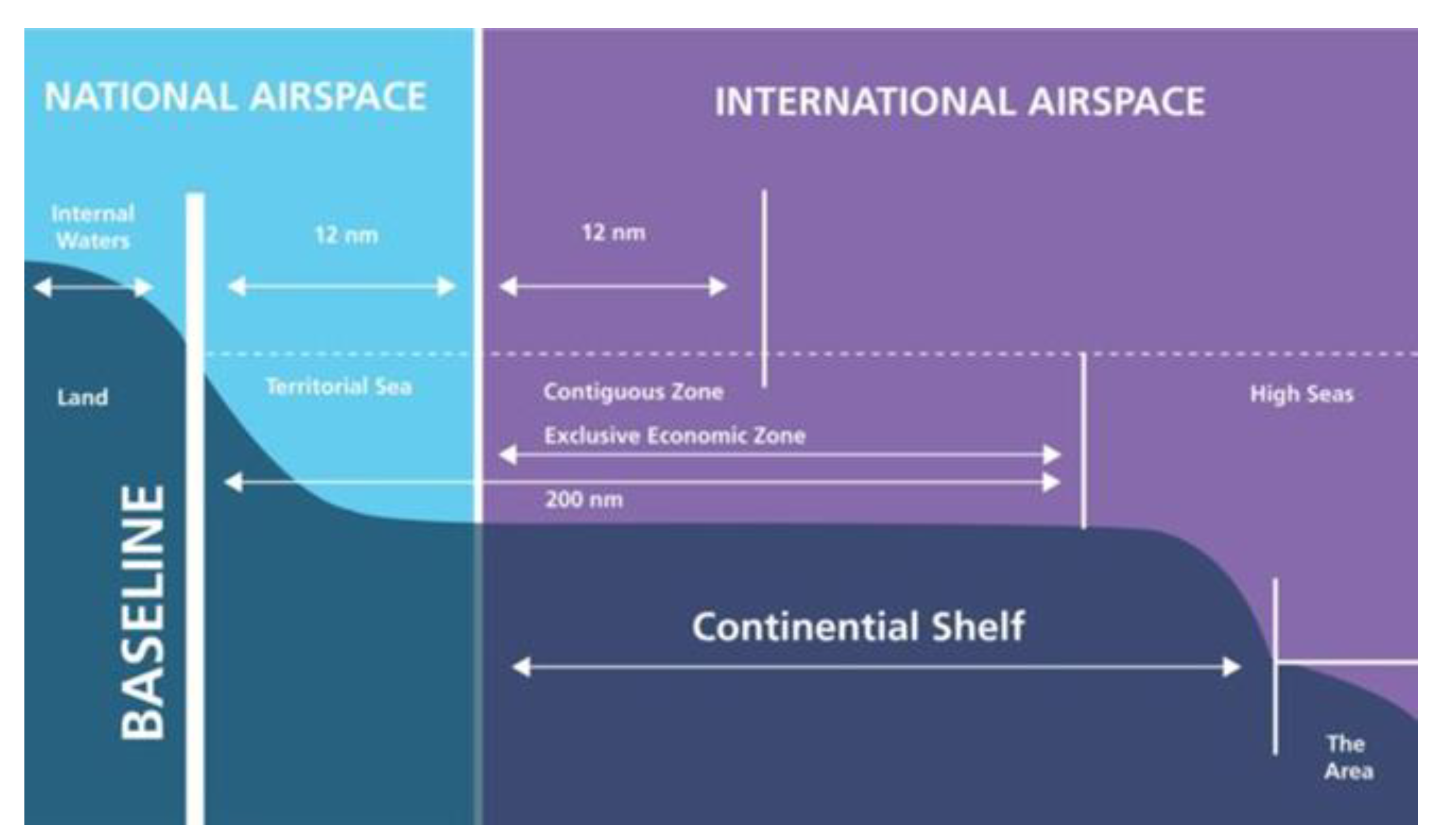

The methodology consists of zoning the oceanic waters based on the distance from the baseline (according to the definition of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea [

12], the baseline is the line along the coast from which the limits of a country's territorial sea and other maritime jurisdictional areas, such as a country's exclusive economic zone, are measured. Typically, a maritime baseline follows the low-water line of a coastal country) to define the different planning tools and the competent administrative levels for them.

In these areas, the MSP scales will be defined, which will be analogous to the TSP scales and must be managed by the same administrative levels: national, regional, and municipal. The equivalent area will be defined as the land area whose planning is managed at the same administrative level and conducted at the same scale.

Integration will be carried out in the areas and their equivalent areas. It will be Integrated Planning by zones.

2. Main Global Organizations Involved in the Sustainable Development of the Ocean

IOC-UNESCO

The Intergovernmental Oceanographic Commission is a commission belonging to UNESCO. UNESCO is the United Nations organization for Education, Science, and Culture. It contributes to peace and security by fostering international cooperation in the fields of education, science, culture, communication, and information. UNESCO promotes the exchange of knowledge and the free flow of ideas to accelerate mutual understanding and a more perfect understanding of each other's lives. UNESCO's programs contribute to the achievement of the Sustainable Development Goals defined in the 2030 Agenda, adopted by the United Nations General Assembly in 2015 [

13].

Figure 1.

Sustainable Development Goals of the UN 2030 Agenda.

Figure 1.

Sustainable Development Goals of the UN 2030 Agenda.

Within this organization is the IOC commission, founded in 1960, which is currently composed of 150 Member States. The work of the IOC contributes to UNESCO's mission of promoting the advancement of science and its applications to develop knowledge and capacities, which are key for economic and social progress, the foundation of peace, and sustainable development. The IOC is responsible for coordinating the United Nations Decade of Ocean Science for Sustainable Development 2021-2030, the "Ocean Decade."

The mission of the IOC is to promote international cooperation and coordinate research programs, services, and capacity building to learn more about the nature and resources of the ocean and coastal areas, and to apply that knowledge to improve management, sustainable development, marine environmental protection, and the decision-making processes of its Member States (IOC Statutes, Article 2.1) [

14].

It operates by making decisions by consensus through its main governing and subsidiary bodies (technical and regional).

As stated by the IOC [

15], through knowledge of oceanographic conditions, the foundation will be laid for understanding climate, living resources and their availability, ocean hazards such as storms, cyclones, tsunamis, and warning systems for them, marine pollution and its effects; changes occurring in the ocean (acidification, sea level rise, warming and its consequences on coral reefs, coastal conditions, erosion, and how to adapt and mitigate these effects); and the absorption of CO2 by the ocean and its repercussions.

The ocean is too vast for any single country to study it alone, making intergovernmental cooperation essential. Therefore, an intergovernmental and collaborative approach is necessary. No country can monitor the global ocean on its own. Oceanography, like meteorology, is necessarily international. It requires government cooperation, as well as coordination and sharing of resources, since it is labor-intensive and infrastructure intensive.

Marine activities have an impact on GDP, with the IOC gathering assessments that estimate this impact around 5% of various national economies. Investments in ocean observation, marine science, and international collaboration will return through increased marine science capabilities, with applications such as coastal protection, the development of industries beyond the continental shelf, improved marine resource management, coastal tourism, safe navigation, and national security. These factors will increase the share of GDP from marine activities.

The Intergovernmental Oceanographic Commission was also founded with the goal of promoting and supporting capacity building, data exchange and storage, and fostering trust.

Since the ratification of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea in 1994, coastal States have been granted jurisdiction over large portions of coastal waters, extending up to 200 nautical miles and beyond.

HIGH LEVEL PANEL FOR A SUSTAINABLE OCEAN ECONOMY

Composed of 19 Member States (Australia, Canada, Chile, Fiji, France, Ghana, Indonesia, Jamaica, Japan, Kenya, Mexico, Namibia, Norway, Palau, Portugal, United Kingdom, Seychelles, United Arab Emirates, and the USA), the members of the High-Level Panel for a Sustainable Ocean Economy (the Ocean Panel) are heads of state and government representing people from all ocean basins, nearly 50% of the world's coastlines, and 44% of exclusive economic zones. They recognize that the ocean is the life source of our planet and is vital for human well-being and a prosperous global economy.

They have issued a call to action (Our Call to Action), which is fully reproduced here:

“We have a collective opportunity and responsibility to protect and restore the health of our ocean and build a sustainable ocean economy that can provide food, empower coastal communities, power our cities, transport our people and goods, and provide innovative solutions to global challenges. In accepting this responsibility and seizing this opportunity, we can give a blue boost to the economy today while mitigating and building resilience for future crises. The framework and five areas of transformation presented here secure ocean health and wealth for generations to come. We urge other governments, industries, and stakeholders to join us in this endeavor.”

The combined exclusive economic zones of Ocean Panel members constitute 68,261,389 square kilometers, twice the landmass of North America and Russia combined.

Mission and Vision

The COVID-19 pandemic has highlighted the deep interconnections between human and planetary health and the need for nations to work together to respond to global threats. The pandemic has caused a dramatic disruption of the global economy, significant impacts on our societies, and enormous costs to our communities. It has put greater financial pressure on developing countries, particularly least developed countries and small island developing states.

The High-Level Panel for a Sustainable Ocean Economy's mission is to undertake a series of transformations that materialize in a Sustainable Ocean Planning. This planning is a strategic framework designed to guide the responsible management of national marine areas, balancing economic, social, and environmental sustainability. It involves policies, regulatory reforms, strategic investments, and marine spatial planning to align economic development with the health of marine ecosystems, thus achieving long-term sustainability.

Sustainable Ocean Planning is an overarching framework in which marine spatial planning (MSP) is situated, which the High-Level Panel for a Sustainable Ocean Economy uses as a reference tool to manage and implement its strategy.

GLOBAL PARTNERSHIP FOR OCEANS [

17]

The Global Partnership for Oceans (GPO) was launched in 2012 by the World Bank as a new approach to restoring ocean health. It sought to mobilize financing and knowledge to activate proven solutions for the benefit of communities, countries, and global well-being. The GPO had more than 150 partners representing governments, international organizations, civil society groups, and private sector interests committed to addressing the threats to ocean health, productivity, and resilience. The partnership aimed to address documented problems of overfishing, pollution, and habitat loss. Together, these issues are contributing to the depletion of a natural resource bank that provides vital nutrition, livelihoods, and ecosystem services.

Next Steps

With oceans firmly integrated into the highest level of development dialogues, the World Bank and its partners felt that it was time to shift from advocacy to implementation. The numerous GPO partners will continue to address ocean health through a variety of solutions and partnerships.

The World Bank Group is committed to financing, investment, and policy reforms that unlock the potential of ocean resources for food security and poverty alleviation, such as replenishing the Fisheries and Aquatic Resources Program (PROFISH+) in an expanded capacity.

Although it no longer serves as the Secretariat of the GPO, the World Bank continues to work in collaboration and partnership with stakeholders to achieve the goals of healthy and productive oceans.

The GPO is a growing alliance of over 140 governments, international organizations, civil society groups, and private sector interests committed to addressing the threats to ocean health, productivity, and resilience.

The partnership aims to address documented problems of overfishing, pollution, and habitat loss. Together, these issues are contributing to the depletion of a natural resource bank that provides vital nutrition, livelihoods, and ecosystem services.

The World Bank has helped facilitate the development of the GPO because it has recognized that improving ocean health is essential for poverty reduction and economic growth.

In all of these organizations, partnerships, and commissions, MSP is proposed as the best tool for achieving the objectives they pursue.

3. State of the Art of Marine Spatial Planning

Basic Concepts of MSP

The first thing that should be understood about Marine Spatial Planning (MSP) from the IOC-UNESCO perspective is its integrative nature. MSP is conceived as the framework for integrated planning in which the challenges of ocean governance can be addressed to promote sustainable ocean governance.

That said, the second thing to understand is the concept of ocean governance from the MSP perspective: It is the way in which ocean affairs are governed by governments, local communities, and other stakeholders, based on law (national and international, public and private), customs, traditions, culture, and the institutions and processes created by them [

18]

To rigorously use the different concepts in the MSP field, we use the following terminology: MSPglobal International Guide on Marine/Maritime Spatial Planning [

19].

Paris, UNESCO. (IOC Manuals and Guides no 89)

Coastal Zone: Refers to a geographical area that connects terrestrial and marine ecosystems. Currently, integrated coastal zone management (ICZM) plans exist in various countries, and these will be included in MSP to form part of the integrated planning.

Ocean Domain: This is the physical space defined as “ocean” in three dimensions, from the sea surface to the seabed, including the entire water column.

Maritime Boundaries: These are the legal definitions of water according to national and international law. The right to develop marine spatial plans extends to the entire maritime area of national jurisdiction (territorial sea), the national sovereignty rights, and jurisdiction over specific matters in the Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) and the continental shelf. Currently, no authority has the mandate to develop and apply marine spatial plans for the Areas Beyond National Jurisdiction (ABNJ), which encompass almost two-thirds of the ocean.

MSP is also considered as part of the broader concept of zone-based planning defined in the text (art1.1) of the agreement under the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea [

20] regarding the conservation and sustainable use of marine biodiversity in areas beyond national jurisdiction [

21].

Figure 3.

-Legal Boundaries of the Oceans and Airspace This figure was uploaded by John Bradford [

22].

Figure 3.

-Legal Boundaries of the Oceans and Airspace This figure was uploaded by John Bradford [

22].

Marine Spatial Planning (MSP)

The Intergovernmental Oceanographic Commission (IOC) of UNESCO (2009) defines MSP as:

The public process of analyzing and allocating the spatial and temporal distribution of human activities in marine areas to achieve ecological, economic, and social objectives that have been specified through a political process.

The National Ocean Council of the United States of America (2013) defines MSP in its manual as: [

23]

Marine planning is a science- and information-based tool that can help promote local and regional interests, as well as address management challenges related to the multiple uses of the ocean, economic and energy development priorities, and conservation goals.

Directive 2014/89/EU of the European Union (EU) establishing a framework for maritime spatial planning [

24] defines MSP as:

The process through which the competent authorities of the Member State analyze and organize human activities in marine areas in order to achieve ecological, economic, and social objectives. Through their maritime spatial plans, Member States will aim to contribute to the sustainable development of offshore energy sectors, maritime transport, fishing and aquaculture sectors, and the conservation, protection, and enhancement of the environment, including resilience to the effects of climate change. In addition, Member States may pursue other objectives, such as promoting sustainable tourism and the sustainable extraction of raw materials.

Common points in all definitions: A tool for governance, a process that considers stakeholders, and aims to achieve sustainable economic and social development while taking conservation goals into account.

Blue Economy

An ocean economy understood as the sum of economic activities, assets, goods, and services based on the ocean. It can be “brown” if economic growth is unsustainable and “blue” when economic growth is sustainable (Patil et al., 2018). It covers a wide range of established sectors, such as fishing, maritime transport, and tourism, as well as emerging sectors, such as renewable energy, aquaculture, and marine biotechnology.

MSP is considered a facilitating objective for the blue economy.

Ocean Multi-Use

The joint and intentional use of the same ocean space and/or resources in close geographical proximity by two or more activities in at least one of the following four dimensions: spatial, temporal, provisioning, and functional.

Depending on the type of interaction between uses and their physical distance, multi-use can be classified as:

- i)

Polyvalent/Multifunction: The marine space is shared by uses that have different functions and are independent of each other.

- ii)

Symbiotic Use: The marine space is shared by associated or linked uses that benefit from this association.

- iii)

Coexistence/Co-location: The marine space is shared in its spatial dimension simultaneously (coexistence) or at alternate times (co-location).

- iv)

Subsequent Use/Re-use: The marine space is shared by one use, and after this use, another use occurs that is independent of the first (subsequent use) or reuses all or part of what was used by the first (re-use).

Marine Management

Refers to the sectoral regulation of human activities at sea: catch quotas, technical regulations for fishing, maritime transport regulations, etc. It also includes measures for the protection of the marine environment: limiting emissions, harmful environmental practices, etc.

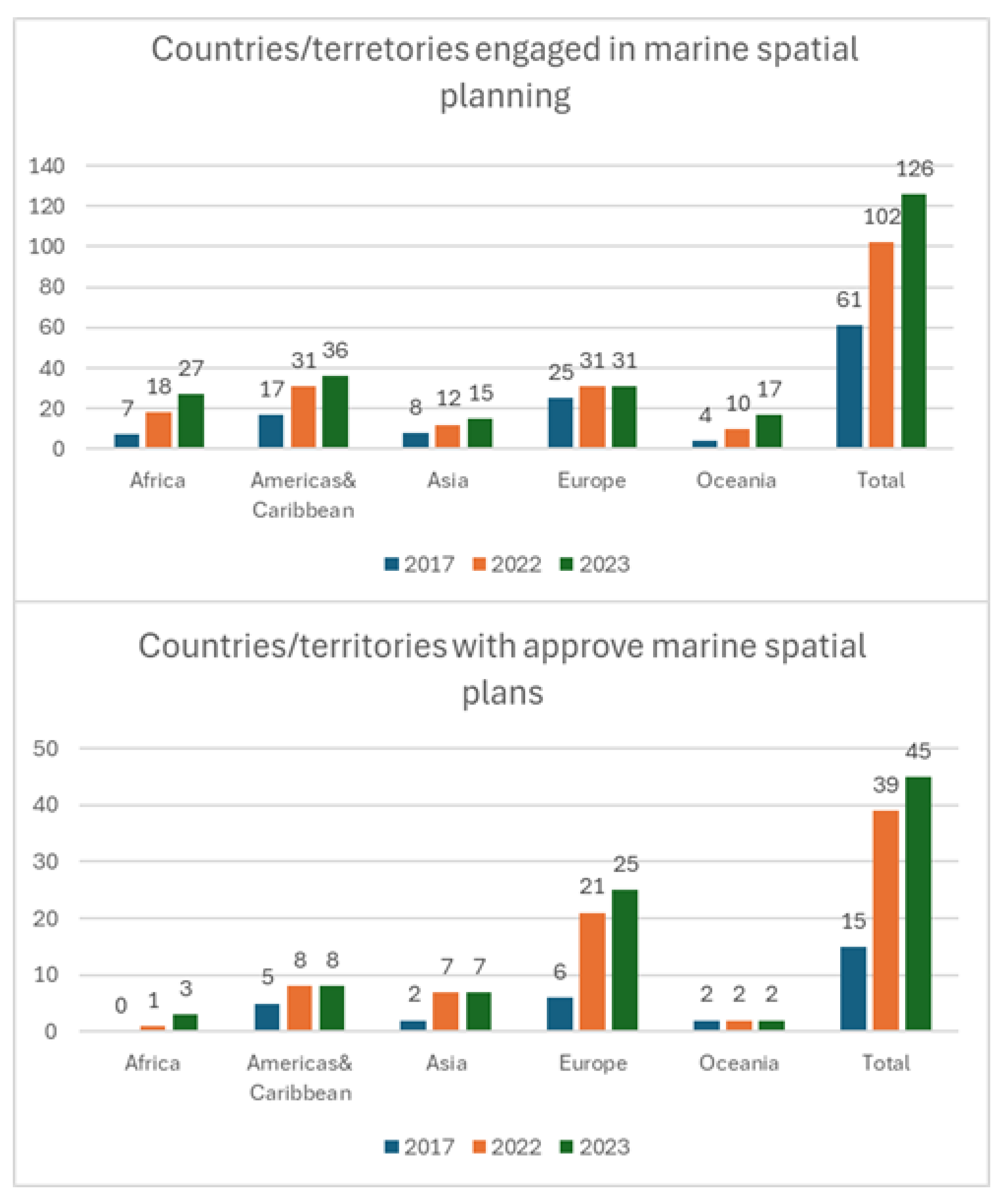

Figure 4.

- IOC-UNESCO assessments about marine spatial planning status around the world: a. Number of countries/territories engaged in MSP; and b. Number of countries/territories with approved marine spatial plans at national, subnational and/or local level. Source: IOC-UNESCO.

Figure 4.

- IOC-UNESCO assessments about marine spatial planning status around the world: a. Number of countries/territories engaged in MSP; and b. Number of countries/territories with approved marine spatial plans at national, subnational and/or local level. Source: IOC-UNESCO.

Sustainable Ocean Planning [

25]

According to IOC-UNESCO, a Sustainable Ocean Plan (SOP) is a strategic framework designed to guide the responsible management of national marine areas, balancing economic, social, and environmental sustainability. It involves policies, regulatory reforms, strategic investments, and marine spatial planning to align economic development with the health of marine ecosystems to achieve long-term ocean sustainability.

What is Sustainable Ocean Planning (SOP)?

Although it may vary from one oceanic region to another, several common attributes define SOP. These include intersectoral participation, transparent and equitable processes, and accountability. Therefore, SOP acts as a general framework for the governance of national marine space through a unified strategy and vision that are based on sustainable development principles.

Key Principles of Standard Operating Procedures for SOP

In 2020, the High-Level Panel for a Sustainable Ocean Economy (Ocean Panel) highlighted SOP as the primary common tool for achieving a sustainable ocean economy. In 2021, they published a shared and common understanding of what SOP means, emphasizing the following key principles:

- Inclusive: Ensures that the voices of all stakeholders are heard and addressed.

- Integrative: Coordinates across government agencies, ocean sectors, and processes.

- Iterative: Adapts to future changes while addressing current needs.

- Place-based: Covers all marine and coastal areas within national waters.

- Ecosystem-based: Acknowledges the interactions between ecosystems and human activities.

- Knowledge-based: Supported by scientific, local, and indigenous knowledge.

- Politically supported: Backed by national governments at the highest level.

- Long-term financing: Ensures sustainable financing mechanisms.

-Capacitated: Equipped with the necessary resources and expertise for implementation.

Sustainable Ocean Planning Program in the Ocean Decade [

26]

The Ocean Decade Program on Sustainable Ocean Planning (SOP) has been jointly designed and developed to respond to the recommendations of the Ocean Panel agenda regarding achieving 100% sustainable ocean planning. It also aims to leverage the Ocean Decade ecosystem, particularly in relation to Challenge 4, and accelerate the implementation of Standard Operating Procedures (SOPs) in coastal nations through technical and scientific support.

While the overarching purpose of this SOP Program is to equip nations with the necessary tools and knowledge to develop and implement user-driven, mission-oriented, climate-smart, and equitable standard operating procedures, supported by scientific knowledge and knowledge from indigenous and local communities, the Program also aims to support cross-border cooperation and enhance capacity development, particularly in least developed countries, large ocean states, and small island developing states. Therefore, the SOP Program aims to foster a global community of practice, bringing together nations, researchers, and stakeholders to co-create and jointly develop evidence-based, tailored strategies for the sustainable use of the oceans.

In conclusion, the SOP Program is:

- Mission-Oriented: Focused on addressing global challenges with practical solutions.

- Collaborative: Promotes a global community of practice among nations, researchers, indigenous peoples, local communities, and stakeholders.

- Equitable: Ensures that Small Island Developing States (SIDS) and Least Developed Countries (LDCs) have access to the tools, knowledge, and capacities necessary for sustainable ocean management.

IOC-UNESCO's Strategy on Sustainable Ocean Planning and Management [

27]

The recognition of the importance of an integrated approach to ocean management is reflected in various international commitments, both within and outside of the IOC, such as the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (especially Goal 14), the agreement under the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea regarding the conservation and sustainable use of marine biodiversity in areas beyond national jurisdiction (BBNJ), the United Nations Decade of Ocean Science for Sustainable Development (Ocean Decade), the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) and its Paris Agreement, the High-Level Panel for a Sustainable Ocean Economy (Ocean Panel), and the Lisbon Declaration from the United Nations Ocean Conference.

For these reasons, a Strategy for Sustainable Ocean Planning and Management (SOPM) is currently being developed at the IOC level, in close consultation with member states and relevant stakeholders at all levels. This collaborative effort aims to create a unified and comprehensive approach to ocean governance, promoting cross-sector dialogue and ensuring alignment with global ocean initiatives. To achieve this, the Strategy's functions will remain deeply interwoven with current and ongoing IOC programs and will expand their roles. This will include programs and projects such as MSPglobal, the Global Ocean Observing System (GOOS), and the International Oceanographic Data and Information Exchange (IODE), as well as several initiatives under the ocean science and tsunami programs.

The Strategy will serve as the guiding framework for the IOC's work across its various programs, facilitating future observations, data collection and management, early warning services, assessments, and the development of innovative tools, knowledge products, and capacity-building initiatives tailored to the needs of the sustainable ocean planning community.

Relationship Between MSP and Climate Change. Climate-Smart MSP [

28]

The integration of strategic climate objectives into general sustainable development and environmental policies related to the marine realm can be achieved through the use of a climate-smart and inclusive Marine Spatial Planning (MSP) as a common framework to establish meaningful and effective actions across all regions. This can be facilitated by establishing interdisciplinary MSP networks to develop climate-smart and inclusive design frameworks for ocean planning.

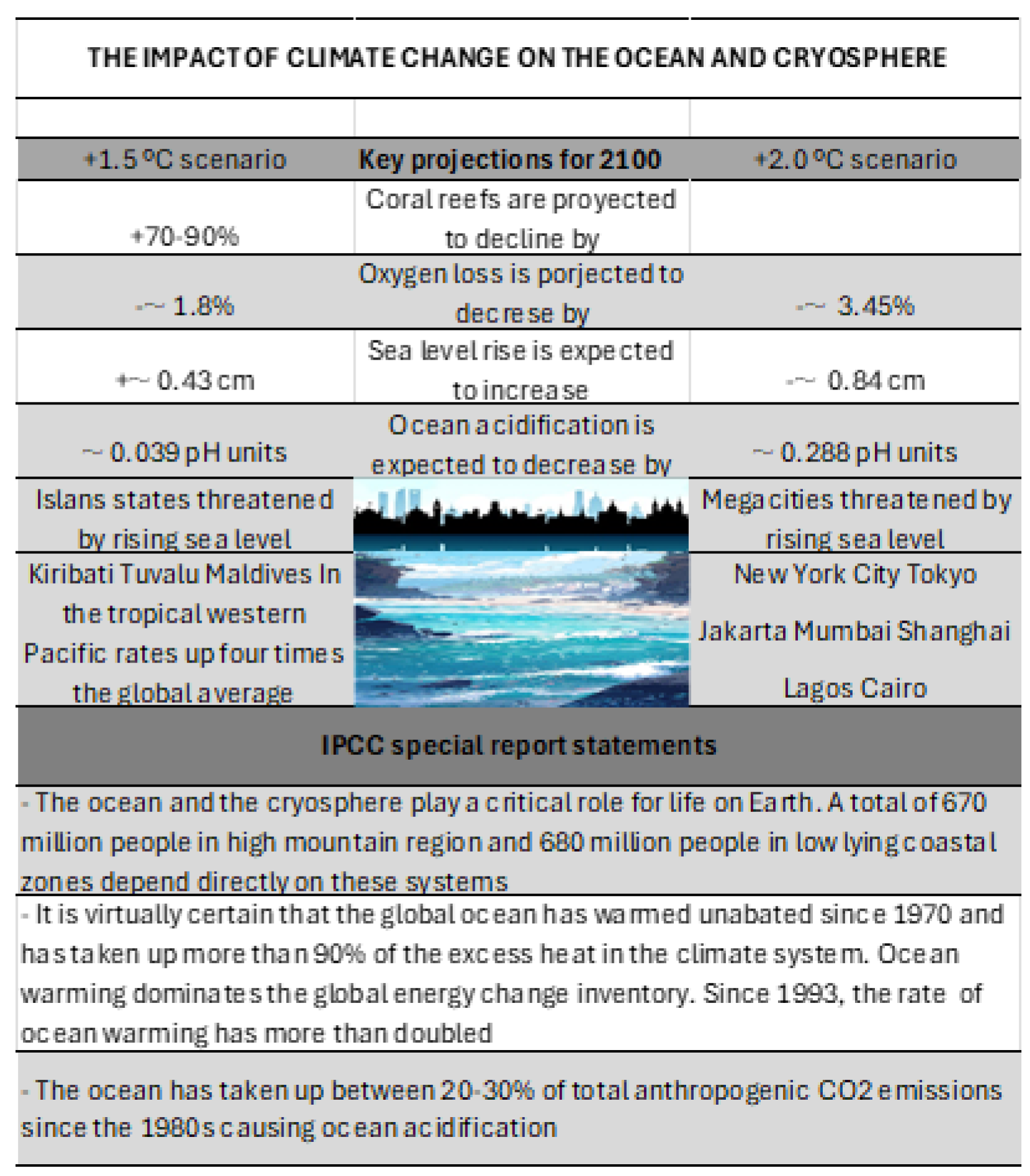

Figure 5.

-The impacts of a changing climate on our ocean. Data source IOC-UNESCO.

Figure 5.

-The impacts of a changing climate on our ocean. Data source IOC-UNESCO.

Challenges in Incorporating Climate Change Impacts into MSP

Topics:

- Variable Impacts on Sectors, Geographies, and Scales

Climate change presents a growing and evolving challenge, requiring flexible and adaptable ocean planning and management. Additionally, the impacts on marine ecosystems are expected to be cumulative, compounded by other human-induced changes [

29]

- Limited Knowledge of Processes and Impacts

Considerable efforts are being made to integrate climate change into spatial use scenarios [

30]. However, there is still limited knowledge about the complexity of the underlying processes driving these impacts. This represents a significant obstacle to reducing uncertainty in spatial planning decision-making [

31].

All of the studies of climate change must be done considering the time variable, defining different evolution scenarios due to climate change. [

32]

- Variable National Responses

Another important consideration is the tremendous disparity in technical, institutional, and financial capacities for climate change adaptation between developed and developing countries.

Facilitators and Opportunities

What is a “Climate-Smart MSP,” and How Can It Contribute to Climate Change Mitigation and Adaptation?

For Marine Spatial Planning (MSP) to become "climate-smart," data and knowledge about the pathways through which climate change impacts marine ecosystems and human uses at appropriate spatial scales are needed. While climate literacy can help build capacity and facilitate behavioral changes to better tackle climate-related challenges, stakeholders can also provide valuable insights into how a specific region has changed over time and how the system functions in general. These are important ingredients of climate-smart MSPs that promote "inclusive nature design" approaches [

33] and constitute a truly dynamic and adaptive ocean governance framework that will effectively contribute to enhancing ocean sustainability and resilience.

Recommendations for Action

- Knowledge Generation and Use

There is a need to expand the knowledge base on climate change impacts. This includes building robust evidence on the uses most vulnerable to climate change effects and that are valuable for the socioeconomics of a specific region, as well as integrating their potential spatial relocation into the development of MSP scenarios.

- Policy Actions

The integration of strategic climate objectives into general sustainable development and environmental policies related to the marine realm can be achieved through the use of a climate-smart and inclusive MSP for nature as a common framework to establish meaningful and effective actions across all regions. This can be facilitated by establishing interdisciplinary MSP networks to develop climate-smart and inclusive design frameworks for ocean planning.

Marine Spatial Planning. Policy Actions in Europe

As an example of the political actions that have contributed to consolidating Marine Spatial Planning (MSP), some of the initiatives that have been carried out in Europe and also in Spain will be presented. [

34]

The European Directive 2014/89/EU, of July 23rd [

35], 2014 which establishes a framework for the planning of maritime space, with a view to promoting the sustainable growth of maritime economies, the sustainable development of marine spaces and the use sustainable management of marine resources in the different coastal countries of the European Union and its transposition in 2017 through Royal Decree 363/2017, of April 8th [

36], opens in Spain the legal framework for the establishment of Marine Space Planning. This Royal Decree was issued in development of Law 41/2010, of December 29th [

37], on the protection of the marine environment, in accordance with the provisions of its article 4.2, which establishes that the Government may approve common guidelines for all marine strategies in order to guarantee the coherence of its objectives, in various aspects including, in its section f), the management of activities that are carried out or may affect the marine environment.

Within this legislative framework, Royal Decree 363/2017, of April 8th, ordered the approval of five maritime space planning plans, one for each of the Spanish marine demarcations. These plans must serve to guarantee the sustainability of human activities at sea, and at the same time, facilitate the development of the maritime sectors, and the achievement of the objectives that these sectors have set, with special attention to those objectives established to fulfil the commitments of the European Green Deal [

38], the Paris Agreement [

39], the European Union (EU) Climate Change Adaptation Strategy [

40] and the EU Biodiversity Strategy to 2030 [

41], among others.

In the preparation of the maritime space planning plans, the procedure established in article 7 of Royal Decree 363/2017, of April 8th, has been followed, with full inter-administrative coordination, as well as promoting the participation of Stakeholders and the civil society.

In Spain, maritime planning comes from the hand of Royal Decree 150/2023 of February 28th [

42]. The scope of application of this royal decree is the five Spanish marine regions: North Atlantic, South Atlantic, Strait and Alboran, Levantine-Balearic and Canary Islands, defined in article 6.2 of Law 41/2010, of December 29th, on environmental protection. marine., and in the terms stipulated in article 2 of said Law [

43]

Figure 6.

The five regions of the POEM. Source: Executive summary of the POEM. Ministry for the ecological transition and the demographic challenge.

Figure 6.

The five regions of the POEM. Source: Executive summary of the POEM. Ministry for the ecological transition and the demographic challenge.

4. State of the Art of Land Planning

Description of Land Planning

Land space planning has highly developed instruments, which are based on legislation at different levels—national, regional, and local.

Land space is organized using various tools that primarily depend on the scale of the space being organized.

Both marine space planning and land space planning are developed based on the specific legislation of a given State. However, here we will attempt to avoid this particularization and will focus on communicating the essential and common aspects of global land planning.

Definition of Territory

The first thing to understand is that, unlike marine space, which in many countries is part of the public domain, in most countries, land corresponds to both public and private use, with the latter being predominant in cities. Public space is reserved for placing infrastructures and buildings, which are the tools used by authorities to provide public services.

In this sense, territory can be defined [

44] as a raw material whose consumption requires programming and structuring under legal supervision. If we substitute "consumption" with "use," this definition could also be applied to marine space, especially along the coastal strip, which gathers most of the human activities of users and residents of coastal cities.

Planned programming and structuring is a form of planning. Therefore, we can say that this planning is organized based on legal, political, economic, and social criteria.

Planning, Management, and Implementation

The planning, management, and implementation of the guidelines established by this planning are executed through technical criteria that require scientific knowledge.

The growth of cities, the planning of non-urban spaces, the integration of infrastructures, the development of real estate or public works, and the control of the land market are scientifically regulated by urbanism and land planning.

Land Planning. Terrestrial Spatial Planning (TSP)

Land planning originated as a state policy and planning tool linked to the consolidation of the welfare state in the 1930s. It became solidified from 1960 as a scientific discipline with technical, economic, social, and administrative nature and as a state policy [

45].

In 1930, land planning as part of economic, social, and regional development policies emerged in the United States. A landmark event in this regard is the implementation of the Integrated Management Plan for the Tennessee Valley, coordinated by the Tennessee Valley Authority, under the Roosevelt administration (1933) [

46], [

47]. This plan's focus was on the management of natural resources, water, electricity generation, flood control, creation of natural reserves, mass housing programs, and urban development of metropolitan areas.

In Europe, land planning emerged associated with urban planning, with two major trends: on one side, the United Kingdom, USSR, and France, which addressed the creation of large urban complexes and housing plans. On the other side, Switzerland and the Alpine countries focused on solving accessibility and connectivity issues.

Land Planning in Europe

In 1983, Europe published its European Charter for Territorial Planning, which outlines the basic principles that should guide member states in this matter:

- Balanced and sustainable development of regions

- Improvement of the quality of life and the quality of infrastructures

- Responsible management of natural resources

- Rational and balanced use of land

Bengoetxea [

48] defines different levels of land planning in Europe based on territorial scope and the predominant approach.

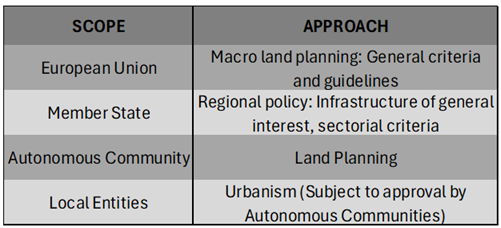

Table 1.

-Land Planning. Scope and Approach in Europe. Source: Bengoetxea, 2000.

Table 1.

-Land Planning. Scope and Approach in Europe. Source: Bengoetxea, 2000.

Land use planning is an integrative discipline, as noted by Serrano (2001), similar to marine spatial planning, which addresses environmental, social, economic, infrastructural, and service-related issues. Land planning involves managing the specific relationships and modes of space appropriation, which must be considered in a systemic way. This is essential if the goal is to achieve a model that promotes equity and sustainability across different territories, as outlined in the European Spatial Planning Charter

Land Use Planning Models in Europe [

45]

These models are based on the political and administrative organizations of the different Member States.

British Land Use Planning Model

This model was used by the United Kingdom before Brexit and, due to its strong implementation, it is still in use today. The UK is a Constitutional Monarchy with a parliamentary-democratic basis. The territories are: England, Wales, Scotland, and Northern Ireland, which are further divided into Counties and Municipalities. The state is unitary, and political and state power is held by the Central Government and the Parliament of London.

The responsibilities for land use planning are divided as follows:

- The Central Government mediates conflicts between local planning authorities and the project developer, oversees infrastructures of general interest, and controls county and municipal planning.

- Counties are responsible for territorial planning at the subregional scale.

- Municipalities are responsible for urban planning for city development.

Since the 1990 Spatial Planning Act, land use planning has been based on territorial balance and sustainability.

French Land Use Planning Model

France's political and administrative organization is based on decentralization. The form of government is a Republic, with a Unitary State that has undergone a decentralization process since the 1980s into three territorial entities: Regions, Departments, and Municipalities [

50].

Currently, the land use planning model is managed according to different territorial levels. Territorial planning has become a shared and negotiated responsibility, increasing territorial integration participation. Ultimately, urban planning is developed by the Municipalities but in a supervised and integrated way into land use planning.

German Land Use Planning Model

Germany's political and administrative organization is based on a Federal State (Bünd) composed of sixteen Member States (Länder), each of which has its own executive, legislative, and judicial organs. These Member States are further divided into Municipalities and Districts. The Länder do not have authority in territorial planning. The executive function is the responsibility of the states, with the exception of the Federal Railways and the Federal Waterways Administration, which fall under the Federation's executive capacity.

Thus, land use planning is conducted at the Federal State level and implemented by the Member States with oversight from the Federal State and participation from Municipalities and Districts. The latter are responsible for the development of urban plans, adjusted to the territorial planning and state-level planning objectives.

Germany has been very active in European territorial policy, establishing the Leipzig Principles, which served as the foundation for the final document of the European Territorial Strategy of 1999 and participated in the formulation of the Guiding Principles for Sustainable Development of the European continent [

51].

Spanish Land Use Planning Model

Spain’s political and administrative organization is that of a Unitary State with a parliamentary monarchy system, highly decentralized into 17 Autonomous Communities, which are further divided into Provinces and Municipalities.

Land use planning is the responsibility of the Public Administration at its various levels of decentralization. The General Administration of the State has authority over the national land laws and establishes principles and general guidelines for regional land laws. It also retains responsibility for planning and executing infrastructures of general interest such as national highways, railways, state ports, and coastal management, which, according to the 1978 Constitution, is under the jurisdiction of the General Administration of the State. However, responsibilities related to coastal areas are currently being transferred to the autonomous communities.

Autonomous Communities are responsible for the development of regional land laws, the development of all regional infrastructure, and the supervision of urban planning, which is managed by Municipalities.

Italian Land Use Planning Model

Italy's political and administrative organization is a Unitary State with a Republic as the form of government. It has a strong decentralization of political power at the regional level. There are 20 Regions, which are further divided into Provinces and Municipalities [

51].

Regions are the territorial entities with exclusive competencies in land use planning and urban planning, with Municipalities having lost most of their powers in favor of the Regions. The state only retains competencies in matters related to infrastructures of general interest, cultural heritage, and the environment.

Conclusions on Land Use Management in the European Union

As we have seen through the analysis of some of its Member States, the European Union has general instruments that establish guiding principles that apply to all Member States:

- The European Spatial Planning Charter (1983) [

52]

- European Territorial Strategy (1999) [

53]

- Guiding Principles for Sustainable Development in Europe (2005) [

54]

All of these documents are inspired by the principles of territorial balance and sustainability in land use planning and urban planning, based on respect for and conservation of the environment.

With this principle, the European Regional Development Fund (ERDF) [

55] was created in 1975. The fundamental challenge faced by the European Union has been the varying stages of economic development among its Member States. This has led to almost three Europes: fully developed Europe (Germany, France, and Italy, and at one time, the UK), the Europe that needed to develop to match these countries (Spain, Ireland, Greece, Portugal), and Eastern Europe (Poland, Bulgaria, Romania, Turkey, and the countries from the former Yugoslavia or the Balkans).

The introduction of a single currency, the absence of internal borders (and thus internal tariffs), and the need to compete as a “single state” against the United States, China, the Commonwealth, Mercosur, and others have demanded a major territorial balance effort. This effort is still underway and remains one of the guiding principles of European policy in general, and specifically in land use planning. The other fundamental principle, sustainability, is not only a matter for the EU but a global guiding principle for ensuring the sustainable development of various national economies based on the preservation of the planet through responsible resource management and environmental protection.

The highest body responsible for land use planning in the European Union is the European Spatial Planning Commission, which defines land use planning as "the spatial expression of economic, social, cultural, and ecological policies of any society... it is a scientific discipline, an administrative technique, and a policy conceived as an interdisciplinary and holistic approach aimed at the balanced development of regions and the physical organization of space according to a guiding conception" (Parejo, 2003).

Thus, it can be concluded that the European approach to land use planning is integrative. It defines spatial uses within a framework of legal security, sustainability, and territorial balance.

SYSTEMATICS IN LAND USE PLANNING

Below, it is detailed the development of land use planning in greater detail. The Spanish model of planning will be used as a basis (though without referencing specific Spanish legislation), and concrete examples will be provided to aid in the understanding of certain descriptions.

The various legislations and administrative organizations of different nations play a decisive role in shaping territorial spatial plans. However, there are several common themes that, rather than being administrative, are scientific in nature and allow us to structure the land use planning process.

1. Territorial Development Plans

The first step in land use planning involves territorial development plans. These plans can be developed at different levels within a country: regional, autonomous community, or federation, and must comply with state legislation and relevant sectoral laws that govern the use of space for various activities (e.g., roads, railways, ports, airports, stormwater drainage systems, etc.). In some cases, less frequently now, they may be developed at the state level.

To facilitate understanding, here are some examples of territorial planning tools, as outlined in the document: [

56]

- Regional Territorial Strategy Plan. This plan sets out the basic elements for organizing and structuring the territory of the Autonomous Community or Region, its strategic objectives, and defines the reference framework for all other territorial planning instruments or plans.

- Territorial Plans. These plans can further develop the Regional Territorial Strategy Plan of the Autonomous Community or, in its absence, provide direct territorial planning at a municipal or subregional level, as defined within the plan or as delineated according to the corresponding Territorial Plan.

- Territorial Action Coordination Programs. These programs establish, within the framework of the Regional Territorial Strategy Plan's determinations, the coordination of actions by Public Administrations that involve land occupation or use and have significant territorial impact.

- Natural and Rural Land Use Plans. The objective of these plans is to protect, conserve, and enhance territories of supra-municipal importance due to their geographical, morphological, agricultural, livestock, forestry, landscape, or ecological value. They are developed in accordance with the environmental determinations of the Regional Territorial Strategy Plan. In coastal regions, Coastal Land Use Plans can also be included at this planning level, with the goal of organizing beaches and maritime fronts.

- Regional Interest Actions. As an exceptional instrument, these actions are designed for cases of special interest or urgency with regional impact, aimed at executing direct urban development activities within the Autonomous Community.

- Municipal Land Use Plans. Municipalities can develop their own municipal strategic plans in accordance with the territorial planning instruments. In the absence of territorial planning instruments at the regional level, these municipal strategic plans are integrated later into the corresponding territorial strategy or Territorial Plan, adjusting as necessary to align with its determinations.

This structure of planning instruments helps ensure that land use is well-regulated at different levels, from the state level to regional, municipal, and subregional levels. These instruments work together to ensure that territorial organization is carried out systematically, balancing strategic development with ecological, social, and infrastructural considerations.

Territorial Impacts of Sectoral Legislation (García- Ayllón, 2014)

In urban and territorial planning, multiple interests converge that affect different bodies of the Public Administrations. Therefore, a global view of the existing or future elements in the territory is required. These elements, as a result of their regulatory planning, generate a series of impacts on the territory that must be taken into account when carrying out its planning.

Two main groups can be differentiated: those referring to natural elements of the territory (watercourses, coasts, livestock routes, forests, protected natural spaces, etc.) and those referring to territorial infrastructures (roads, railways, ports, airports, energy transportation, etc.), both within the framework of national as well as regional or autonomous legislation.

In all these cases, the specific legislations regulating each of these elements have a hierarchical level higher than that of the various urban planning laws, meaning that the elements regulated by them must comply with sectoral legislation.

- a)

Impacts derived from natural elements of the territory:

- -

- Impacts related to coasts.

- -

- Impacts related to water bodies.

- -

- Impacts related to livestock routes.

- -

- Impacts related to forests.

- -

- Impacts related to protected natural spaces.

- b)

Impacts derived from territorial infrastructures:

- -

- Impacts related to roads.

- -

- Impacts related to railways.

- -

- Impacts related to airports.

- -

- Impacts related to the transportation of electricity.

Urban Planning Instruments within Municipal Competence

At the municipal level, the main element of planning is the General Urban Planning Plan. One possible classification of land in this General Plan, in terms of its nature concerning its level of urban planning, can be distinguished as follows:

Non-urbanizable land: Land that cannot be urbanized due to its special characteristics, such as environmental protection, historical value, or other protective characteristics.

Urbanizable land: Land that can become urbanized through development planning. This land may be:

Sectorized

Non-sectorized

-Urban land: Land that has sufficient urban development to allow direct construction or minimal urban transformation. This can be further classified into:

Consolidated

Non-consolidated

Special

The urban planning instruments will be:

General Urban Planning Plan

Development Planning

Partial plans

Land readjustment projects (related with the ownership of land)

Sectorization projects (related with the phases of development)

Special plans (Plans for Special Situations)

Study of detail (For specific areas)

Urbanization projects (Technical projects aimed at equipping the land with the necessary infrastructure for services, mobility, and green areas)

General Urban Planning Plan

These are responsible for establishing the urban planning of municipalities. They define the model for urban development. Within their scope of action, they classify the land (the terrestrial space) as: urban land, developable land, and non-developable land.

Development Planning

Its purpose is to develop the land defined in the General Plan by providing specific urban planning parameters, which allow for the construction of buildings on the land under specific and homogeneous conditions for lands of the same type.

Partial Plans

Partial Plans define the scope of their action within the General Plan, providing detailed planning for the different sectors defined in the Partial Plan, establishing zoning with the allocation of land uses (residential, public facilities, industrial, commercial, and others) and building typologies. It will establish regulations for land use, development (amount of built surface area on the land surface), and designate areas for green spaces, as well as reserves for public and private facilities.

Special Plans and Detail Studies

These are development tools similar to Partial Plans, distinguished by their specific application. They may differ in scope or because they only regulate certain parameters.

5. Materials and Methods

Marine Spatial Planning and Terrestrial Spatial Planning: characteristics for integration.

The authors aim to achieve the integration of both land and marine spatial planning in order to create an integrated spatial planning system. While this integration may seem straightforward at the tool level, it presents both limitations and opportunities based on the similarities and differences of these two planning systems.

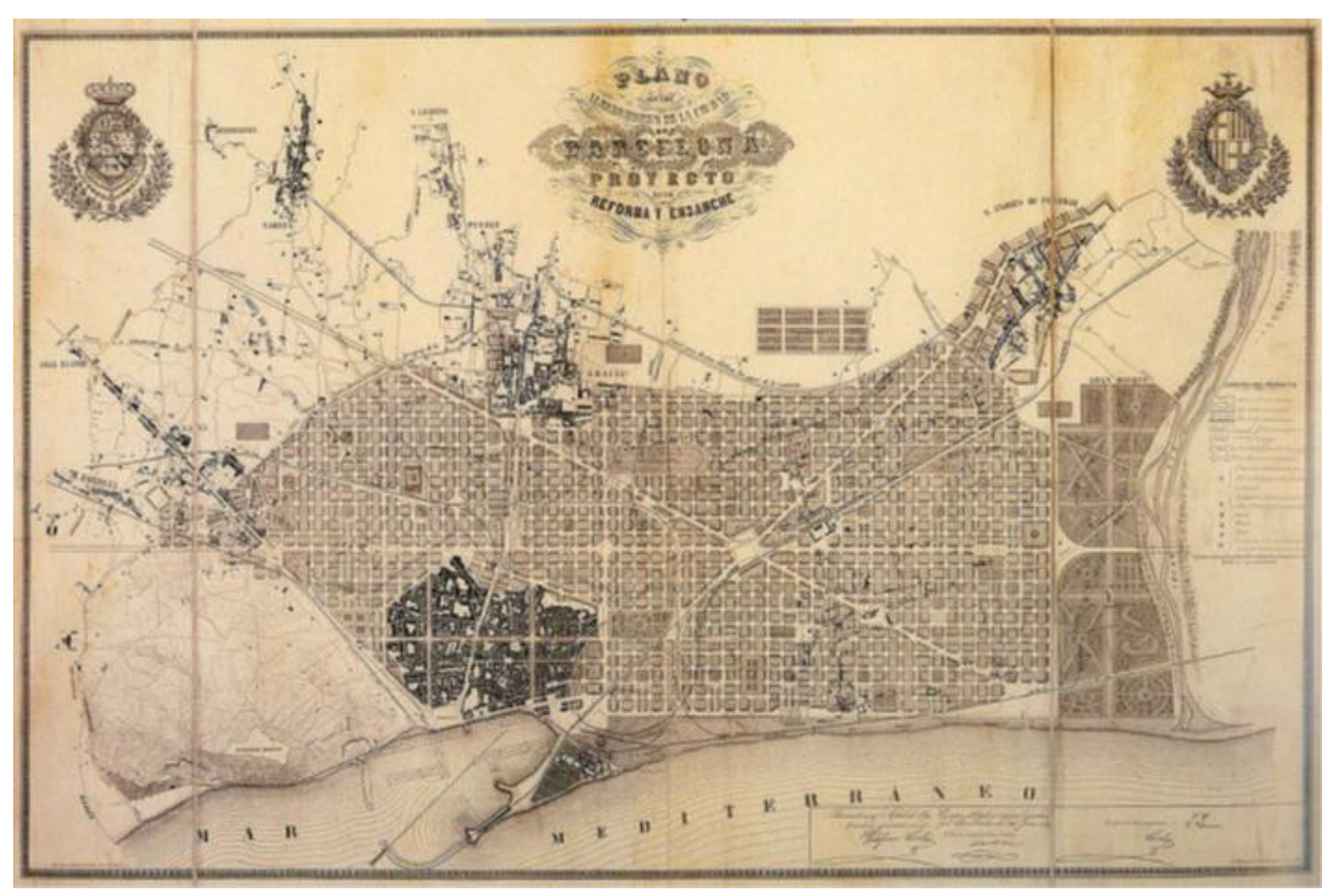

Figure 7.

Cerdá Plan in Barcelona. Source: City History Museum, Barcelona. Source [

44].

Figure 7.

Cerdá Plan in Barcelona. Source: City History Museum, Barcelona. Source [

44].

It can be seen in the photo that, despite the training of the illustrious Mr. Ildefonso Cerdá as a Civil, Canal and Port Engineer, his masterful planning of the city of Barcelona was carried out with his back to the sea.

First, let's assess the progress made in marine spatial planning (MSP) in this regard. To do so, we can refer to the MSPglobal (manual by IOC UNESCO/European Commission (UNESCO-COI/European Commission, 2021).[

19]

Integrating land, coastal, and marine planning, including the land-sea interactions

In many cases, coastal and marine areas have unclear boundaries, which highlights the need to connect coastal and marine planning measures. This way, "planning systems" can be created to coordinate policies and give coherence to territorial measures, especially for coastal areas (which are themselves interfaces between land and sea).

While the integration of coastal and marine spatial planning is a common element in many coastal-marine policies, its integration into land planning, which has a longer history, is less common. Although coastal-marine articulation is evident, creating systems that link these three domains is less frequent. This is due to its complexity, the difficulty of concentrating administrative competences within a limited number of institutions, and the novelty of marine spatial planning. The standardization of maritime policies with a corresponding shift towards regional and local government levels seems to be a developing trend, and in this context, it will be easier for territorial and planning policies to build complex systems for the integrated management of both land and marine spaces.

Furthermore, the manual analyzes the interaction between land and sea, delving into various aspects that must be considered when addressing coastal zones within Marine Spatial Planning.

While the outer marine boundary of plans typically corresponds to the limits of Exclusive Economic Zones (EEZ) or the continental shelf depending on the case, with few issues other than those associated with their delimitation, the inner or terrestrial boundary is more complex. This is related to determining the respective boundaries of land planning, coastal management, and emerging MSP, as well as considering the interactions between land and sea as part of MSP, and the need to integrate territorial and coastal aspects of planning within MSP.

This convergence of plans can lead to inconsistencies in objectives and goals, as well as conflicts at the level of regulations and institutions during the development phase.

Land-sea interactions can be interpreted both within an environmental framework (ecosystems and natural processes) and an economic framework (uses and activities), as described in United Nations Environmental Program (UNEP) (2016-2018) [

57], [

58], or in relation to different categories of environmental, socioeconomic, and technical interactions, as expressed by the European Commission [

59].

From the more specific perspective of formal plan development, another dimension to consider is the institutional interaction between administrative hierarchies, the distribution of competences, and the types of plans. This is a key reflection that the authors have utilized in their proposed model.

Both in the convergence between Marine Spatial Planning (MSP) and land planning, as well as in considering land-sea interactions in the development of planning, it is recommended to operate within an integrated political planning system between land and sea, which facilitates the transfer of knowledge from consolidated land planning to MSP [

60].

The concept of land-sea interactions, when applied to small islands, requires consideration that these interactions occur entirely within the insular territory and that their territorial plans, by their nature, have a strong maritime dimension.

Below are several definitions of land-sea interaction as referred to by IOC/UNESCO (1. Priority Actions Program/ Regional Activity Centre (PAP/RAC), 2018 [

61],. 2. European Observation Network for Territorial Development and Cohesion (ESPON) [

62], 2020 and land sea interactions MSPglobal2030 [

63].

What is land-sea interaction?

Although there is no single definition of land-sea interaction, the following can be considered:

- Any possible interaction between land and sea. [

64].

- "Land-sea interactions involve complex and constantly evolving interconnections between socio-economic activities, both at sea and on land, and natural processes that occur at the land-sea interface" [

65].

- A four-dimensional definition of land-sea interaction that includes:[

66]

o 1) Socio-ecological interactions.

o 2) Relevant governance frameworks.

o 3) Interrelated governance processes; and

o 4) Knowledge and methods required to address them"

Examples of land-sea interactions

Land-sea interactions can generally be grouped into two categories that are closely interrelated, through biogeochemical processes and socio-economic activities [

67]

How can land-based processes affect the ocean and seas?

- Agricultural and wastewater pollutants discharged into a freshwater body and flowing into the sea

- Sediment transport via rivers

- Port activities

How can the ocean and seas affect land areas?

- Submarine cables that connect maritime activities to an on-land electrical grid

- Marine debris/pollutants from maritime activities

- Coastal erosion

- Extreme events (storms, high tides, tsunamis)

- Sea level rise

Relationship between MSP and land-sea interaction

The analysis of land-sea interactions aims to inform the marine spatial planning (MSP) process by identifying key elements that link the terrestrial and marine components of the coast, which must be considered when planning the marine space. In other words, the land-sea interaction issues that need to be addressed and the opportunities that can be exploited.

Integrating Integrated Coastal Zone Management (ICZM) and MSP

Reconciling the development and good ecological status of resources, while considering environmental, economic, and social concerns, Integrated Coastal Zone Management (ICZM) and MSP are privileged instruments for the sustainable development of coastal and marine areas. Therefore, they constitute two mechanisms through which land-sea interaction can be addressed.

In practice, similarities, differences, and overlaps between the two processes can be observed depending on institutional frameworks, policies and public regulations, as well as cultural aspects and geography in each country.

According to the authors, this would be a first step towards integrating spatial planning; however, in this article, the proposed method is much more general, with the aim of achieving a total integration of both spatial planning systems.

Differences and Similarities between Marine Spatial Planning and Land Spatial Planning

The essential difference lies in the level of transformation required as a result of the planning of space:

In Terrestrial Spatial Planning, the transformation is very deep. Territory planning transforms the land for the creation of various infrastructures, including transportation networks with large linear works, river channelling, flood attenuation, large dams and reservoirs for water supply, vast residential, industrial, and logistics developments, waste treatment plants (for industrial, urban, solid, and liquid waste), and others. These infrastructures support the various activities that drive the economy and social needs.

When considering large infrastructures within Terrestrial Spatial Planning along the coastal strip, such as port works, submarine outfalls, protective dikes, and beach regeneration, Marine Spatial Planning requires much less transformation.

This level of transformation will determine the level and form of integration.

From the analysis of the current state of both planning systems, it can be deduced that, while Terrestrial Spatial Planning has developed various scales of planning, from territory planning to detailed urban planning, Marine Spatial Planning does not have different scales. Essentially, this planning has been defined at the regional level.

Another factor affecting the different planning instruments is the timeline for their implementation, with some instruments being long-term planning tools (MSP and Territory Planning), while others are shorter-term, such as those defined in the development instruments of Municipal Urban Planning.

This article will present a proposal for integration associated with a suggestion for defining other smaller-scale planning elements for Marine Spatial Planning.

Proposal for the Integration of Marine Spatial Planning and Land Spatial Planning

Zoning and Administrative Management Levels

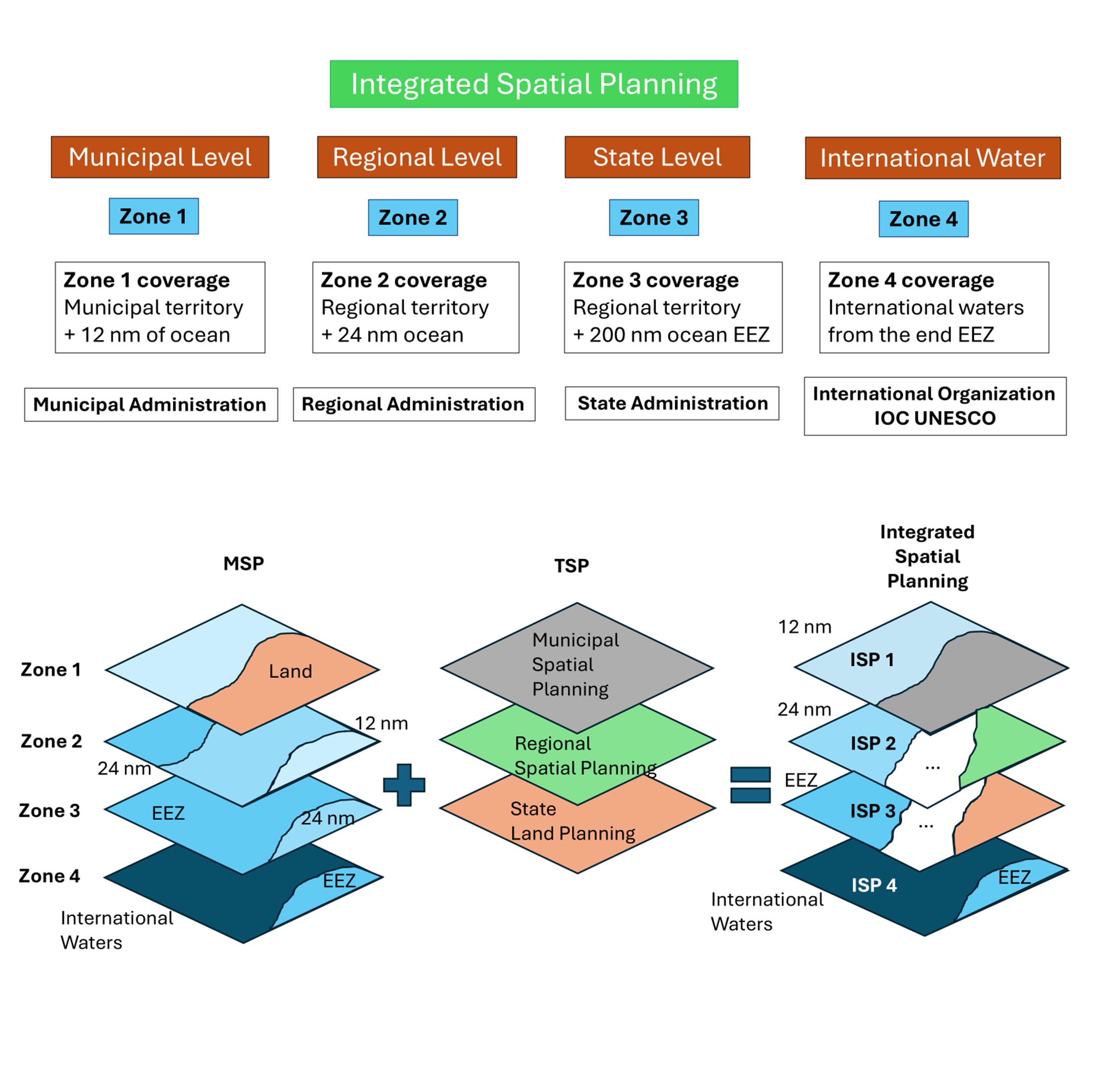

First, different areas within the Marine Space must be distinguished, in which different planning criteria will be applied (see

Figure 2):

- Zone 1: Internal waters and territorial sea (up to 12 nautical miles from the high-water mark or baseline).

- Zone 2: Contiguous zone (up to 24 nautical miles).

- Zone 3: Exclusive economic zone (up to 200 nautical miles).

- Zone 4: International waters (beyond 200 nautical miles).

These zones should have different levels of administrative management:

Zone 1: The administrative management unit should be the one managing urban planning at the municipal level within the various territorial planning management systems, under the supervision of the Autonomous Community.

- Zone 2: The administrative management unit should be regional, meaning the administrative unit responsible for territorial planning management at the regional level.

- Zone 3: The administrative management unit should be national (State level).

- Zone 4: The administrative management unit should be under the jurisdiction of IOC-UNESCO.

Marine Spatial Planning According to Zoning Based on Distance from the Baseline (Boundary between Land and Marine Domains)

Zone 1

In this zone, Marine Spatial Planning must be organized at various scales, similar to the scales of Land Spatial Planning.

See the following schematic division of Land Spatial Planning according to different scales:

In general terms, we can distinguish between Urban Planning and Territorial Planning, establishing some differences that we will detail:

• The main distinction is the scale of work.

• Urban Planning focuses on planning and management at the municipal level.

• Territorial Planning at the supra-municipal level deals with different sectoral infrastructures (coastline, industry, railways, roads, service and telecommunications networks, and ports).

• Urbanism includes:

o Development planning (GUDP, Partial Plans, Special Plans, Interior Reform Plans, Detailed Studies, etc.)

o Urbanization projects

o Drafting of parceling projects and various urban management processes

Territorial Planning assumes:

o Sectoral Guidelines (Coastal, industrial land, agricultural land, railways, roads, service and telecommunications networks, ports)

o Territorial analysis and diagnosis (Territorial impact studies, Territorial Planning Plans, Actions of Regional Interest)

o Environmental Strategies.

o Strategic policies for the territory

o Areas of General Interest

o Priority Use Areas

o High Potential Areas

o Protected Areas

Thus, in Zone 1, the following planning tools will be presented, from lower to higher scale:

- Urban Planning: Definition of the city and its coastline up to 12 nautical miles. Within Marine Planning, there will be different levels of detailed urban planning, namely: general marine planning, partial marine planning, and “marine infrastructure” plans (equivalent to urbanization projects in land planning).

- Similar to Land Spatial Planning, Urban Planning is subject to regional and/or national supervision (depending on the territorial planning competencies of the different States) with regard to the impacts caused by regional or national infrastructures, which we will call sectorial infrastructures, and their guidelines (sectorial guidelines).

Zone 2

Planning in this zone corresponds to its counterpart in land planning, i.e., planning at the supra-municipal scale:

Marine Spatial Planning in this zone will not have detailed planning but will provide general criteria for different uses. Those that require the construction of infrastructures will demand specific projects similar to those used in Land Spatial Planning to define regional interest infrastructures. In this case, the competent administration will be the same as in Land Spatial Planning. For state-interest infrastructures and uses, the General State Administration will supervise and direct the various uses and specific projects.

Zone 3

Planning in this zone will be reserved for the General State Administration, as the entire area is of general interest.

Zone 4

In international waters, the organizations designated by IOC-UNESCO will be responsible for Marine Spatial Planning, both for uses and resource exploitation.

Integration of Marine Spatial Planning and Terrestrial Spatial Planning

This integration is defined as the creation of a single planning system for each state for both terrestrial and marine planning in Zones 1, 2, and 3. The marine planning for international waters is excluded, as these areas, by definition, do not have state sovereignty or exclusivity.

Within Zones 1, 2, and 3, the integration of spatial planning involves integrated documents for each of the scales:

In Zone 1, we will have Integrated Spatial Planning that includes all terrestrial and marine elements of urban planning and its detailed organization. The responsibility for this planning will rest with the municipality, subject to regional and state supervision arising from sectoral influences.

In Zone 2, by analogy, there will be Integrated Spatial Planning that includes the entire planning process and a plan at a scale where the infrastructures and uses of regional and state interest are defined.

In Zone 3, the Integrated Spatial Planning will encompass state-level infrastructures and uses.

In Zone 4, there will be no Integrated Planning; only marine spatial planning will exist due to the nature of international waters.

6. Results. Integrated Spatial Planning

Taking a "top-down" approach, i.e., from the most general to the most specific, from international to municipal, the general approach would be as follows:

For international waters, beyond the EEZ, only IOC/UNESCO frameworks will exist, with general MSP (Marine Spatial Planning) rules. This planning can define international maritime routes for passenger transport, goods, hazardous materials, energy extraction, aquaculture, or offshore mining. It will also include international transmission lines for electricity, gas, oil, and communications, as well as offshore mining activities, defining their characteristics, locations, and transport routes for the extracted minerals. In short, the MSP must be the framework within which both socio-economic activities with a sustainability approach and ecosystem characteristics to be preserved are spatially framed. In this regard, the location of measurement stations for physical, chemical, and biological parameters will be established, allowing for the characterization of the environment, tracking its evolution, and predicting future parameters through the application of advanced mathematical models using AI neural networks. With these estimates, we can analyze the consequences for ecosystems and infrastructure, and study solutions that ensure the ocean’s ecosystem sustainability, and consequently, the sustainability of socio-economic activities.

In the EEZ up to 200 nautical miles, Zone 3**, from the baseline, the state's general planning will be applied. This planning will consist of the MSP and its reserved zones for different uses, which should also include the routes for the transport of goods and passengers. The state planning for terrestrial space will mainly focus on space use, defining general transportation networks, railways, state ports, coastlines, and general service networks such as electricity, gas, and communications. As with international waters, a similar methodology will be applied to study parameters, predict their evolution, and establish sustainability actions. Thus, a single document will integrate both the state-level Territorial Planning (TSP) and the MSP.

In Zone 2, up to 24 nautical miles, regional territorial planning instruments will be integrated with the MSP, as previously defined. In terms of Marine Spatial Planning, as explained in the IOC/UNESCO framework, it will be the territorial planning instruments that include MSP elements at a scale equivalent to those instruments. As a result, in coastal regions, the Territorial Planning Guidelines and Plans, Coastal Planning Plans, Territorial Action Programs, and Regional Interest Actions will encompass both the terrestrial space of the region and its maritime space up to 24 nautical miles, forming a single document. In the maritime space, this document will be subordinated to the MSP.

Similarly, in Zone 1, between the baseline and 12 nautical miles, in addition to the MSP at its scale, municipal planning instruments, i.e., the General Urban Developing Plan (GUDP), will include the maritime space up to 12 miles, subordinated to the guidelines set by the MSP. Therefore, it will contain the land-sea interactions, Integrated Coastal Zone Management documents, and all the MSP documents that affect the municipality.

All the above must be done considering the time variable, defining different evolution scenarios due to climate change.

The introduction of the temporal variable will make us turn to planning models that are adaptive to the new configurations of the coasts [

32]. That is, Integrated Spatial Planning must foresee the change in the coastal configuration and the evolution of its effects due to extreme events. Therefore, ultimately municipal planning will be conditioned to said change in coastal configuration and the changing effects of extreme events.

7. Discussion

This article presents a model for the integration of MSP (Marine Spatial Planning) and TSP (Territorial Spatial Planning). This model is necessary to ensure territorial governance in its broadest sense: governance of the municipality and its coastlines, governance of the region and its regional waters, and governance of state-controlled waters.

The proposed zoning for the different scales of integrated planning responds to the scope of responsibility of the administering authority. It is a proposal that, as the authors understand, is coherent. Just as states have responsibility up to 200 nautical miles of the EEZ (Exclusive Economic Zone) in Zone 3, the different Zones 1 and 2 are proposed. This approach considers the different levels of responsibility of the authorities in most coastal states, namely: the State Administration (Zone 3), the Regional Administration (Zone 2), and the Municipal Administration (Zone 1).

In the different zones, uses are defined that make no sense to analyze separately for land and sea. For example, electric, gas, oil, and communication lines will appear in a single planning document and can be analyzed and managed within a unified governance framework. It would make no sense for one administration to define a route on land, with all the related issues, and then, when the route enters the maritime zone, different authorities be responsible. Outside the scope of Integrated Planning, different sustainability challenges are faced, and governance responsibilities change. The integration approach requires marine planning experts at all levels of administration to handle developments in an integrated manner at the state, regional, and municipal levels. The result of this approach is the best framework for analyzing the sustainability issues of socio-economic activities and ecosystems, both terrestrial and marine. Terrestrial and marine ecosystems are interrelated, so we must govern them from an integrated approach that accounts for this interrelationship.

The integration into Zone 1 is of particular importance, as it is the area most affected by land-sea interaction. For example, it does not make sense for one administration to regulate the discharge of continental waters into the sea, carrying pollutants from agriculture, without considering the medium into which they are discharged. Integrated spatial planning allows for a better analysis of problems, their causes, and solutions, but not in just one of the domains (marine or terrestrial). The solution must address the entire environment. The environment is unique, and it is affected in an integrated way, so the solutions must be integral. For this, the best approach is to ensure that the tools for managing space use are integrated tools.

The issue of climate change, which particularly impacts coastal cities due to the potential rise in sea levels or coastal retreat, is best analyzed from an integrated perspective. It makes no sense to have municipal urban planning that only extends to the limit of the public maritime-terrestrial domain. If done this way, the problem will only have partial solutions. However, with a General Urban Planning Plan that considers both the continental and maritime spaces up to 12 nautical miles, it is possible to provide comprehensive solutions for the orderly growth of coastal cities that are sustainable and also preserve the sustainability of marine and terrestrial ecosystems. Furthermore, new activities such as aquaculture, marine renewable energies (wave, tidal, offshore photovoltaic, and offshore wind), should contribute to the development of the Municipality and the Region, and therefore, should be considered in the corresponding Integrated Plans. Likewise, cultural, tourism, and recreational activities in coastal municipalities will be better managed through Integrated Spatial Planning.

It is possible to define other zonings, but the approach presented here will remain the same if done analogously to how it has been outlined. That is, according to the governance levels of state, regional, and municipal authorities.

Once the integration model has been identified and proposed, this will be the basis for the study of the activities and design of coastal cities, both for their growth and for their protection against the effects of extreme events and rising or retreating sea levels. caused by climate change. It should also serve to prepare coastal cities against disastrous dangers, such as hurricanes and, more importantly in Spain, the event of possible tsunamis [

68] y [

69]. Another example of how different activities resulting from various uses should be included in the integration model is: the maritime and port operations, ensuring safety and prevention through the application of inspections under the Paris MOU [

70].

Integrated Space Planning will be the tool that will serve for the total management of the territory, including the EEZ and with it, both the sea-land interaction and the critical variables of the evolution of climate change will be analysed [

71]. Serving as a basis for managing the rise or fall of sea level, conditions caused by extreme events and preparation for disastrous dangers, such as hurricanes, tsunamis, or earthquakes.

Obviously, for planning to be effective, it must be available in a Geographic Information System (GIS) that makes available both the graphic results of the planning, as well as the data that characterize the environment, organized in supports that allow for massive computer processing.

Finally, in the different countries, integrated planning systems must be sought that are compatible with each other, allowing the characterization of the physical environment beyond the EEZ zones of the different sovereign States. International waters, both on their surface, water column and seabed, are and will be a source of resources that will multiply world wealth if we are able to carry out sustainable exploitation of these new "territories" It is essential to define international organizations and laws that regulate the rules. of exploitation of international waters and funds by the different sovereign States [

34]

In this regard, advanced initiatives can be found, such as the PATRICOVA from the Valencia Autonomous Community (Spain) [

72], which, as shown in the figure, has pre-implemented in the tool both territorial planning initiatives and models on flood risk due to river overflow, storms, or rising sea levels caused by climate change, which interact with this planning.

8. Conclusions