1. Introduction

In today’s digital age, video games have become an indispensable part of our daily lives, providing an interactive and engaging platform for entertainment. However, their importance goes beyond mere entertainment and they have become innovative educational tools. Video games, with their ability to immerse players in real and compelling language scenarios, play a central role in the process of language learning. This research explores the usage of video games as a powerful channel for language learning, challenging conventional methodologies and opening up new avenues for language acquisition.

Several studies have investigated the relationship between video games and second language learning. For example, [

1] examined how the use of video games affects motivation for language learning. Others like [

2] argue that the use of video games at an early age promotes second language acquisition. Other authors claim that they are useful for increasing foreign language knowledge [

3]. However, there are studies that suggest that the possibilities for language learning with video games are very diverse and that a guiding role of the teacher is desirable [

4]. Others show that good pedagogical planning is necessary for the use of video games for language learning to be really useful [

5].

Despite the growing popularity of video games as an educational tool, there is a notable gap in the scientific literature on their use in second language learning, as most existing studies have focused on the motivational and cognitive aspects of video games. Furthermore, existing literature has rarely focused on the bibliometrics of the field, which limits our understanding of trends and patterns in the existing literature. In doing so, this study will not only provide a more complete picture of the current state of research in this area, but also identify areas that require further investigation.

This study was supported by “PIT+: Innovation and Talent Program” from the Education and Employment Department from Junta de Extremadura and European Union and the Erasmus+ Project “BABO: Bilingual and Bicultural Outlook” from the European Union (Ref.: 2021-1-ES01-KA220-SCH-000027950).

Bibliometric analysis is a quantitative method used to assess scientific production and its impact on a given field of knowledge. Based on the examination of scientific publications and their citations, such an approach provides a thorough understanding of the state of research in a given field, derived from the analysis of scientific publications and their citations. As a result, such studies can identify research trends, help researchers make informed decisions, and assess the performance of researchers, institutions and countries in terms of scientific output and impact [

6]. Given that no bibliometric analysis of the intersection between video games and language learning has been carried out to date, nor has any study been conducted using conventional bibliometric laws, the present study aims to evaluate publications related to video games and language learning, identifying the most prominent journals, the most prolific and prominent authors, the most relevant papers and the most recurrent keywords.

2. Materials and Methods

The bibliometric analysis was carried out using publications from journals indexed in the Web of Science (WoS) database from Clarivate Analytics (WoS importance citation). The search was carried out in the WoS Core Collection database within the Science Citation Index Expanded (SCI-E), Social Sciences Citation Index (SSCI) and Emerging Sources Citation Index (ESCI) editions. For this search, the command “TI” was used to find the term only in the titles of the documents; the command “AB” was used to find it in the abstracts of the documents; and the command “AK” was used to find it in the author keywords of the document. The next search was performed on 15 November 2023, using the following vector:

(TI=(“video game*” OR “videogame*” OR “online game*” OR “mobile game” OR “digital game” OR “online gaming” OR “videojuego*” OR “exergames”) OR AB=(“video game*” OR “videogame*” OR “online game*” OR “mobile game” OR “digital game” OR “online gaming” OR “videojuego*” OR “exergames”) OR AK=(“video game*” OR “videogame*” OR “online game*”OR “mobile game” OR “digital game” OR “online gaming” OR “videojuego*” OR “exergames”)) AND (TI=(“second language” OR “language learning” OR “foreign language” OR “linguistic skill*” OR “english learning” OR “spanish learning” OR “chinese learning” OR “french learning” OR “portuguese learning” OR “language education” OR “language acquisition” OR “language develop*” OR “linguist* develop*”) OR AB=(“second language” OR “language learning” OR “foreign language” OR “linguistic skill*” OR “english learning” OR “spanish learning” OR “chinese learning” OR “french learning” OR “portuguese learning” OR “language education” OR “language acquisition” OR “language develop*” OR “linguist* develop*”) OR AK=(“second language” OR “language learning” OR “foreign language” OR “linguistic skill*” OR “english learning” OR “spanish learning” OR “chinese learning” OR “french learning” OR “portuguese learning” OR “language education” OR “language acquisition” OR “language develop*” OR “linguist* develop*”))

Papers that did not have video games or language learning as the main subject of study were excluded from the search. The sample was exported from WoS in .xslx and plain text (.txt) formats for further processing using Microsoft® Excel® for Microsoft 365 for Business and Vos Viewer (version 1.6.20).

Descriptive analysis was used to examine the patterns of annual publications. DeSolla-Price’s law, which postulates the exponential growth of science [

7,

8], was used. The estimation involved determining the coefficient of determination (R2) adjusted to an exponential growth rate. The purpose of this adjustment was to determine whether the annual publications corresponded to a phase of exponential growth.

In order to analyse the WoS categories into which the documents were classified, the WoS tool “Analysis of results” was used to select the main categories, to check who were the authors who contributed the most documents to each subject, and which journals and publishers accumulated the most documents in these categories.

Lotka’s Law [

9] was used to identify the cohort of prolific authors. This statistical framework involves estimating prolific authors using the square root of the total number of authors who have contributed to a selected subset of the sampled papers. Furthermore, this estimation is validated by adjusting the power law that governs the relationship between prolific authors and the resulting number of published papers. This adjustment is made by examining the coefficient of determination (R2), a statistical measure calculated using Microsoft Excel. The most cited documents on the topic were then examined using the Hirsch index [

10], which specifies a set of “n” documents with “n” or more citations. Those with the most citations were considered to be the most productive. To select prominent authors, prolific authors were cross-referenced with the most cited papers, with prolific authors with papers among the most cited being considered prominent authors.

In order to identify the journals that are characterised by a significant amount of published work on video games and language learning, a concentration analysis was carried out using Bradford’s law [

11,

12,

13,

14]. Applying this law, the journals are grouped into terciles according to the number of publications, with the core of journals in this field being the journals that make up the first publication tercile. A descriptive analysis of the journals making up this core was carried out using the WoS tool “Analysis of results”.

Zipf’s law [

11,

15] was used in the study of scientific production areas. This law facilitates the identification of the most frequently used author keywords within a given document set, and their estimation is achieved by the square root of the total number of author keywords.

The countries that co-authored the documents found were analysed, highlighting the countries that contributed the most documents, using co-authorship analysis in VOSViewer software.

3. Results

A total of 268 papers were found, but after checking whether these papers met the inclusion and exclusion criteria, 238 papers were included in this bibliometric analysis.

The 238 documents were published from 2005 to 2023. From the first paper [

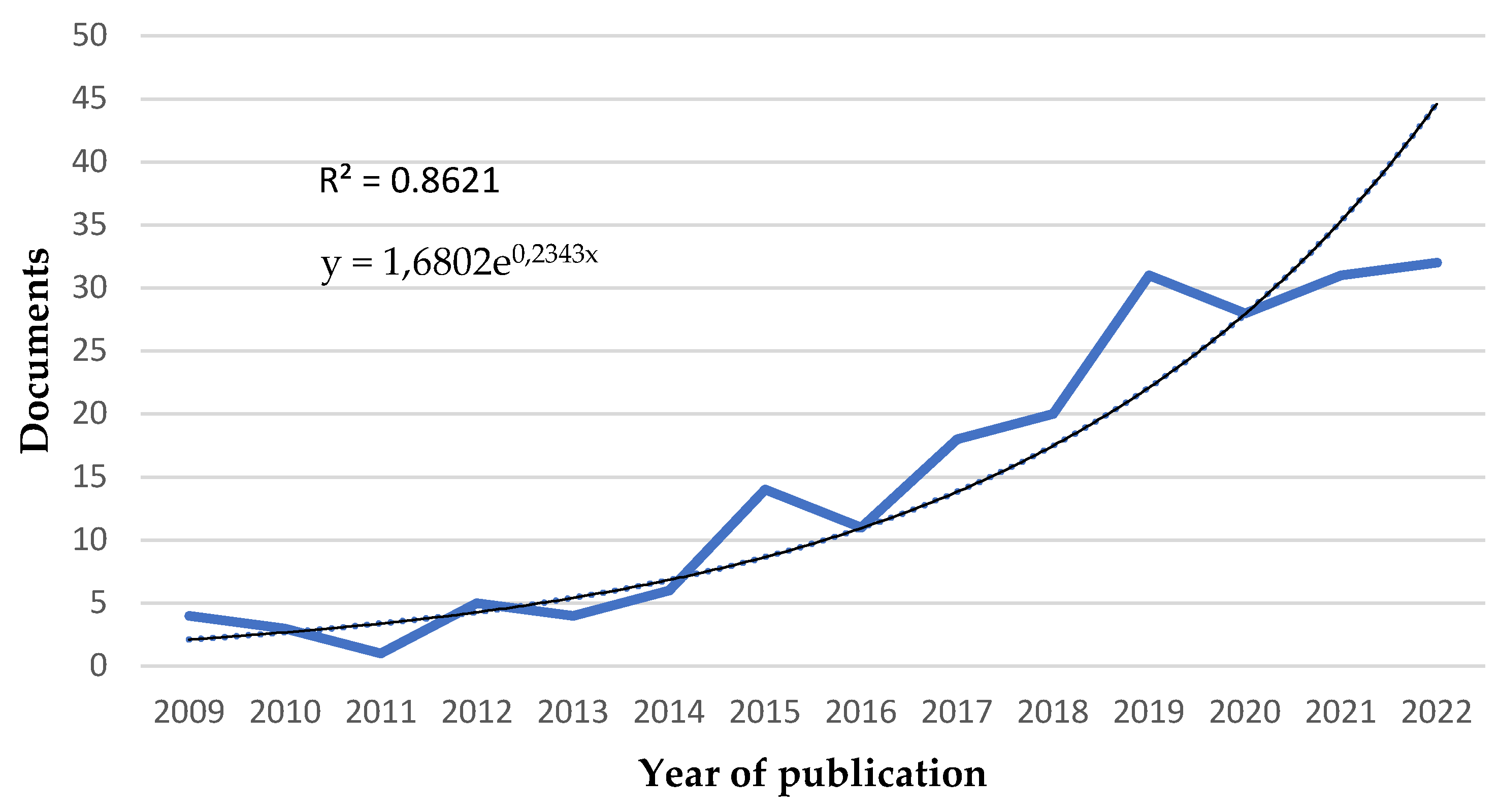

16], no continuity in annual publications was found until 2009. From 2005 to 2009, sporadically published papers were found (2), but from 2009 to 2022 (2023 was excluded as it was not finalised and not having complete data) annual publications were found to be uninterrupted and followed an exponential growth trend with a goodness of fit at an exponential growth ratio of R² = 0.8621 (

Figure 1).

The 238 papers were found to be distributed by WoS in 39 categories. Among categories, Education Educational Research (169 papers), Linguistics (70 papers), Language Linguistics (51 papers) and Computer Science Interdisciplinary Applications (16 papers) stood out.

Table 1 shows the descriptive analysis of the main categories, including the number of documents, the most productive author in the subject area and the journals and publishers that contributed the most documents.

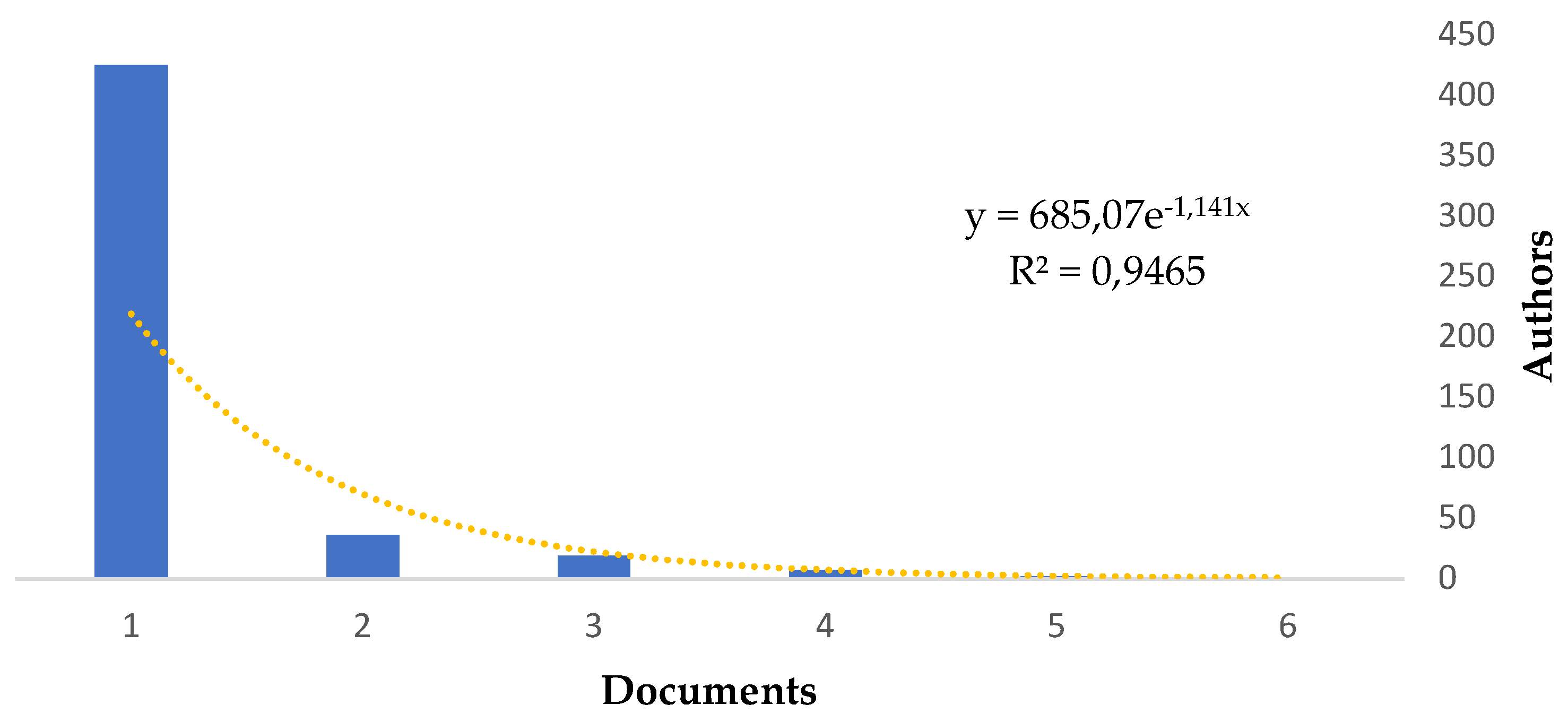

When analysing the authors, 490 authors were found, after standardisation and elimination of duplicates. These authors had a publication range between 1 and 6 papers. Applying Lotka’s law, it was estimated that the prolific authors should be the 22 (square root of total authors, 22.13) with the highest number of publications. When performing the discrete count of authors and their papers we found that 10 authors had published 4 or more papers and 29 authors 3 or more papers, the latter being considered prolific authors (

Figure 2).

Twenty-nine prolific authors were identified, including Jie Chi-Yang (6 papers and 233 citations), Ricardo Casan-Pitarch (5 papers and 12 citations) and Gwo-Jen Hwang (5 papers and 217 citations).

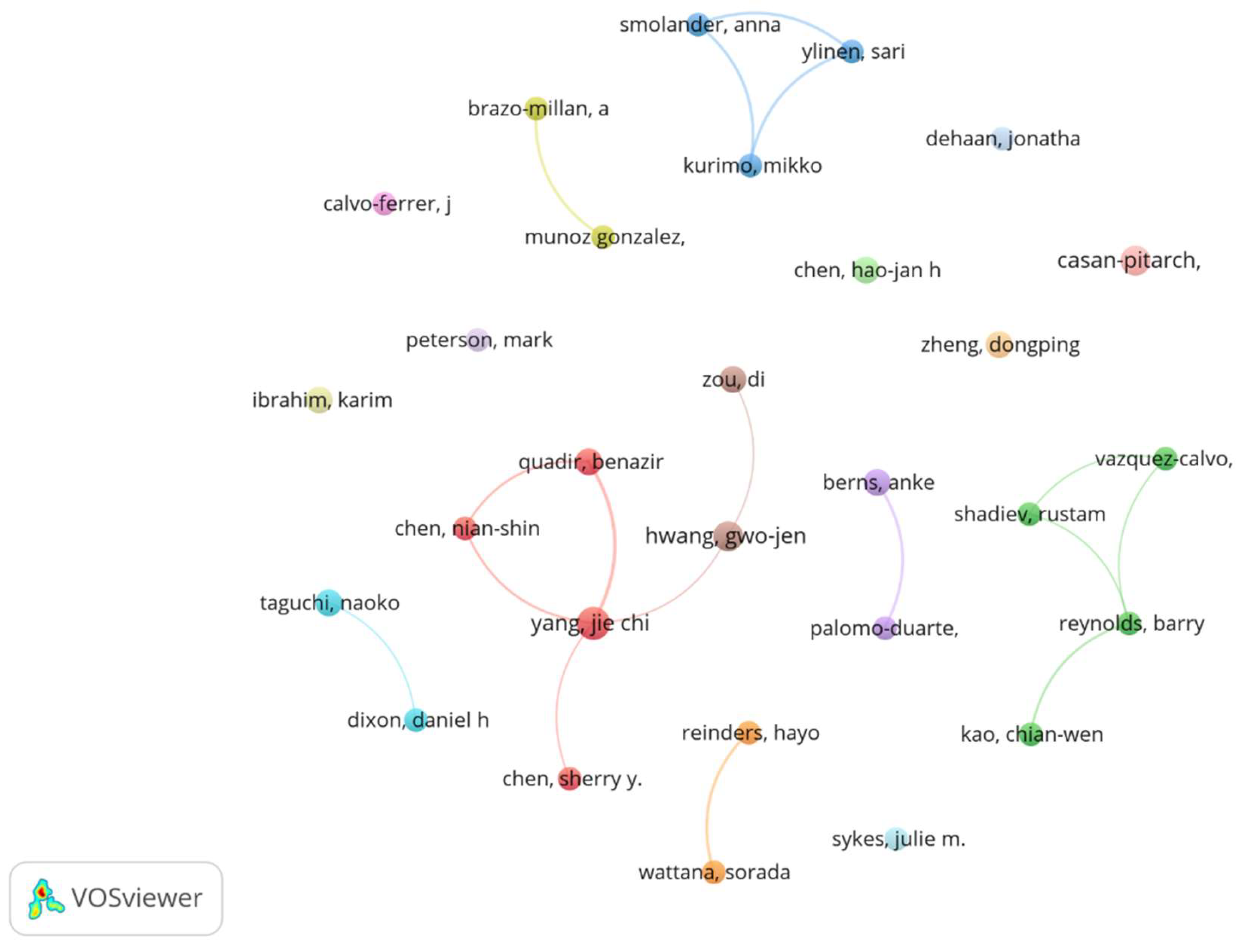

Figure 3 shows three large clusters: the first, in red, includes the 6 authors with the highest level of production; the second, in green, includes 4 prolific authors; and the third, in blue, another group of 3 prolific authors. In addition, we find some smaller relationships between other authors producing in pairs (yellow, purple, light blue and orange clusters) and another 8 authors producing individually.

When analysing the citations of the set of documents, it was found that these documents had a range of citations between 0 and 417. When applying the h-index, there were found 35 documents with 38 number of citations, these being the most cited documents.

Figure 4.

Relationship between number of citations and number of documents (h-index).

Figure 4.

Relationship between number of citations and number of documents (h-index).

Among the 35 most cited papers, [

17] stood out with 417 citations and [

18] with 267 citations.

Table 2 shows the 35 most cited papers, the number of citations, the journal and publisher in which they were published, the subject category assigned to them and the index in which they were indexed.

When crossing the prolific authors with the most cited papers, 14 authors stood out, with 3 or more papers with some paper among the most cited papers, considering these as prominent authors.

Table 3 shows the prominent authors.

124 journals were found with a publication range between 1 and 14 papers. Applying Bradford’s law, these journals were distributed into three zones: Bradford’s publication core consisted of 11 journals publishing 36% of the papers (86 papers, 36.13%), Zone I consisted of 25 journals (65 papers, 27.31%) and Zone II consisted of 87 journals (87 papers, 36.55%) (

Table 4).

The Bradford core of journals in this subject area was made up of the journals shown in

Table 4, with Computer Assisted Language Learning being the journal that published the highest number of papers (14), followed by Recall (12 papers).

Table 5.

Core of Bradford journals ordered by number of papers.

Table 5.

Core of Bradford journals ordered by number of papers.

| Zone |

Journal |

Acc. |

Documents |

Citations |

WoS

Category |

JIF |

JCR |

%OA |

| Core |

Computer Assisted Language Learning |

5,88% |

14 |

479 |

Linguistics; Education & Educational Research |

7,0 |

Q1 |

6,38% |

| Recall |

5,04% |

12 |

521 |

Linguistics; Education & Educational Research |

4,5 |

Q1 |

29,85% |

| Computers & Education |

3,78% |

9 |

523 |

Education & Educational Research |

12,0 |

Q1 |

19,36% |

| Language Learning & Technology |

3,78% |

9 |

516 |

Linguistics; Education & Educational Research |

3,8 |

Q1 |

0,00% |

| Interactive Learning Environments |

3,36% |

8 |

114 |

Education & Educational Research |

5,4 |

Q1 |

4,79% |

| Foreign Language Annals |

2,94% |

7 |

86 |

Linguistics; Education & Educational Research |

2,7 |

Q1 |

5,88% |

| British Journal of Educational Technology |

2,52% |

6 |

89 |

Education & Educational Research |

6,6 |

Q1 |

19,21% |

| Calico Journal |

2,52% |

6 |

48 |

Education & Educational Research |

2,0 |

Q2 |

0,00% |

| Arab World English Journal |

2,10% |

5 |

25 |

Linguistics |

1,0 |

Q2 |

97,61% |

| Education and Information Technologies |

2,10% |

5 |

51 |

Education & Educational Research |

5,5 |

Q1 |

16,30% |

| Journal of Computer Assisted Learning |

2,10% |

5 |

239 |

Education & Educational Research |

5,0 |

Q1 |

23,97% |

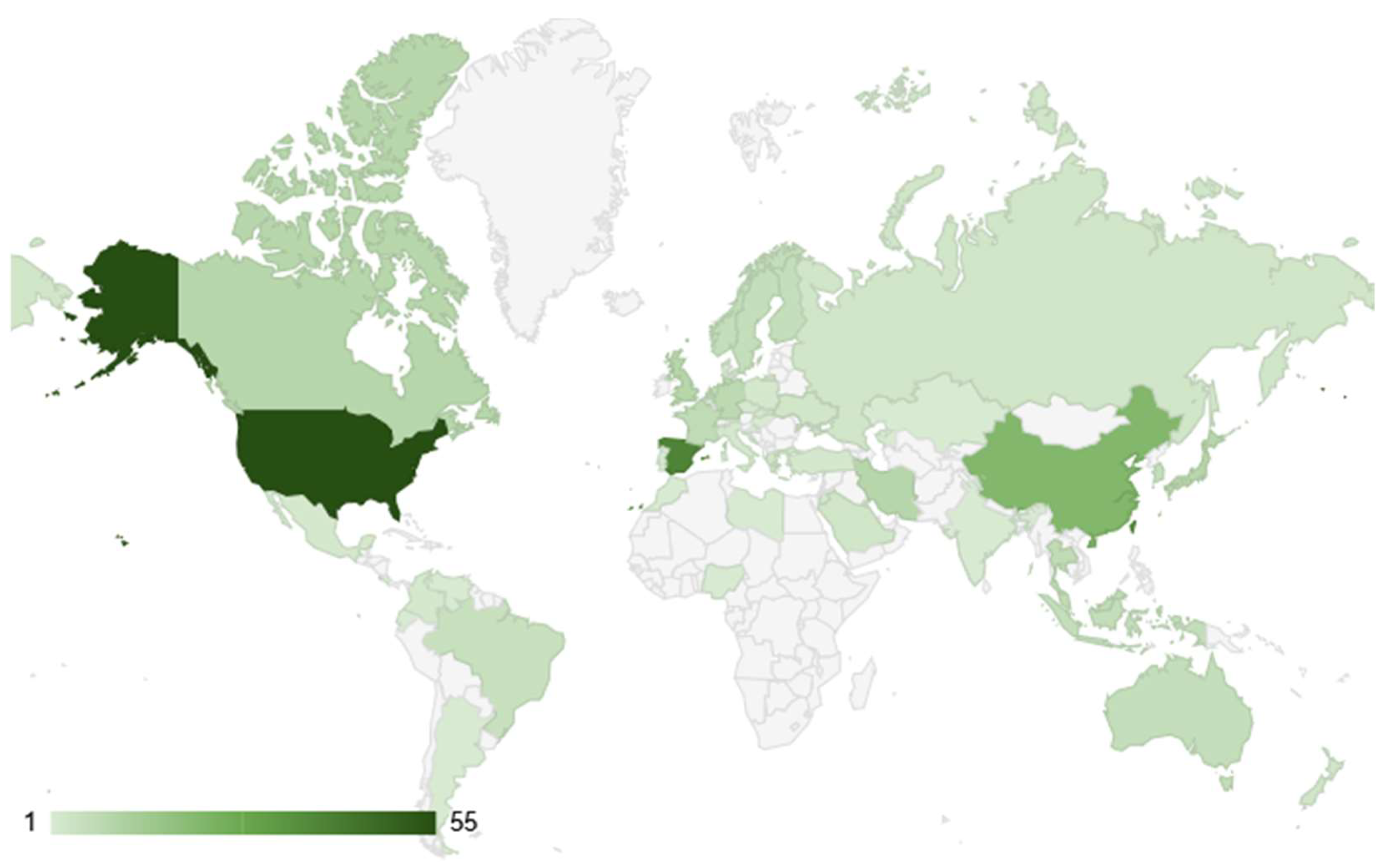

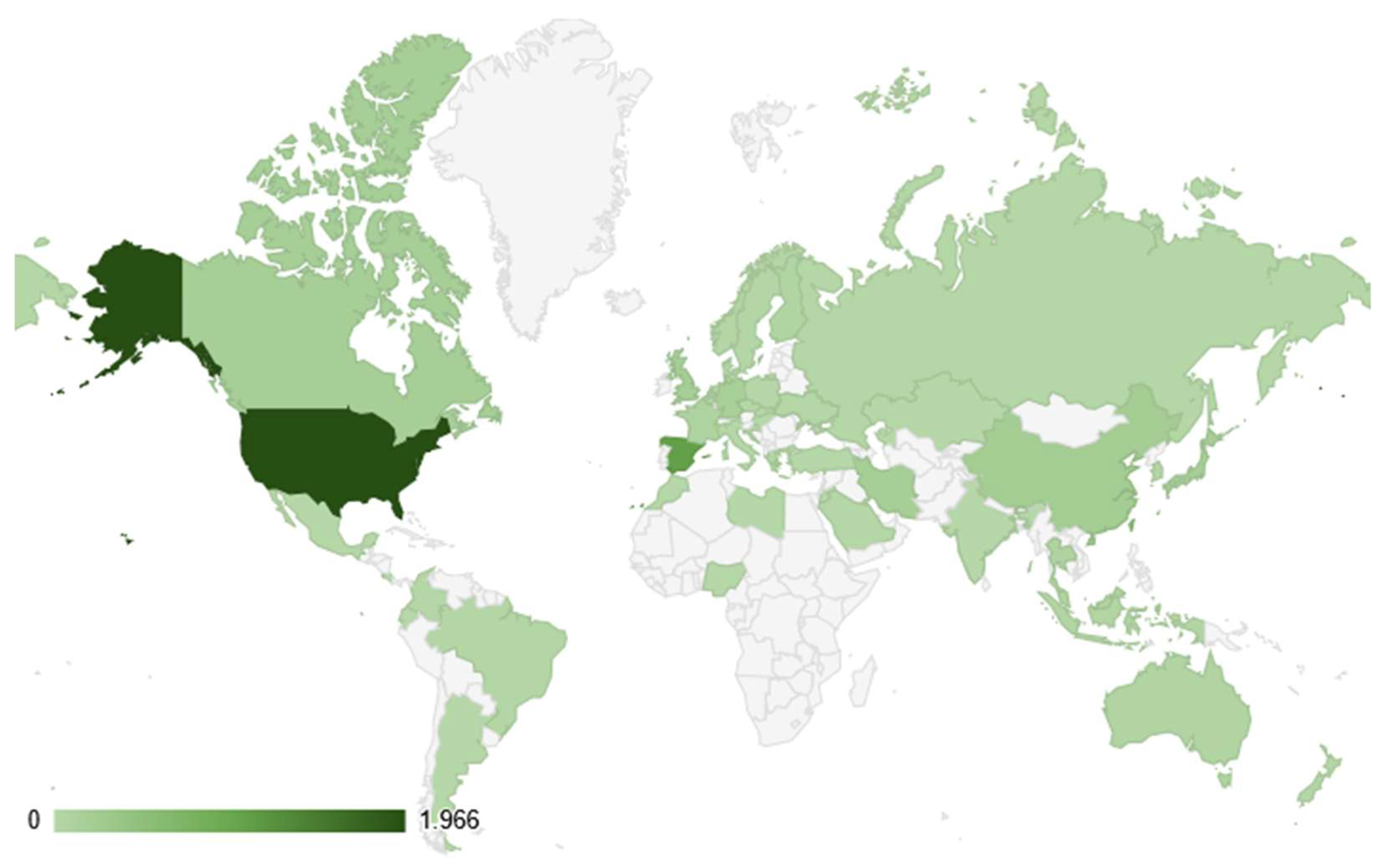

When analysing the co-authored countries, 48 countries were found with a range of documents between 1 and 48, with the USA being the country with the most documents (48 documents), followed by Taiwan (36 documents) and Spain (33 documents). The USA (1966 citations) was also the country with the most citations, followed by Taiwan (1076 citations) and China (548 citations), (

Figure 5 and

Figure 6).

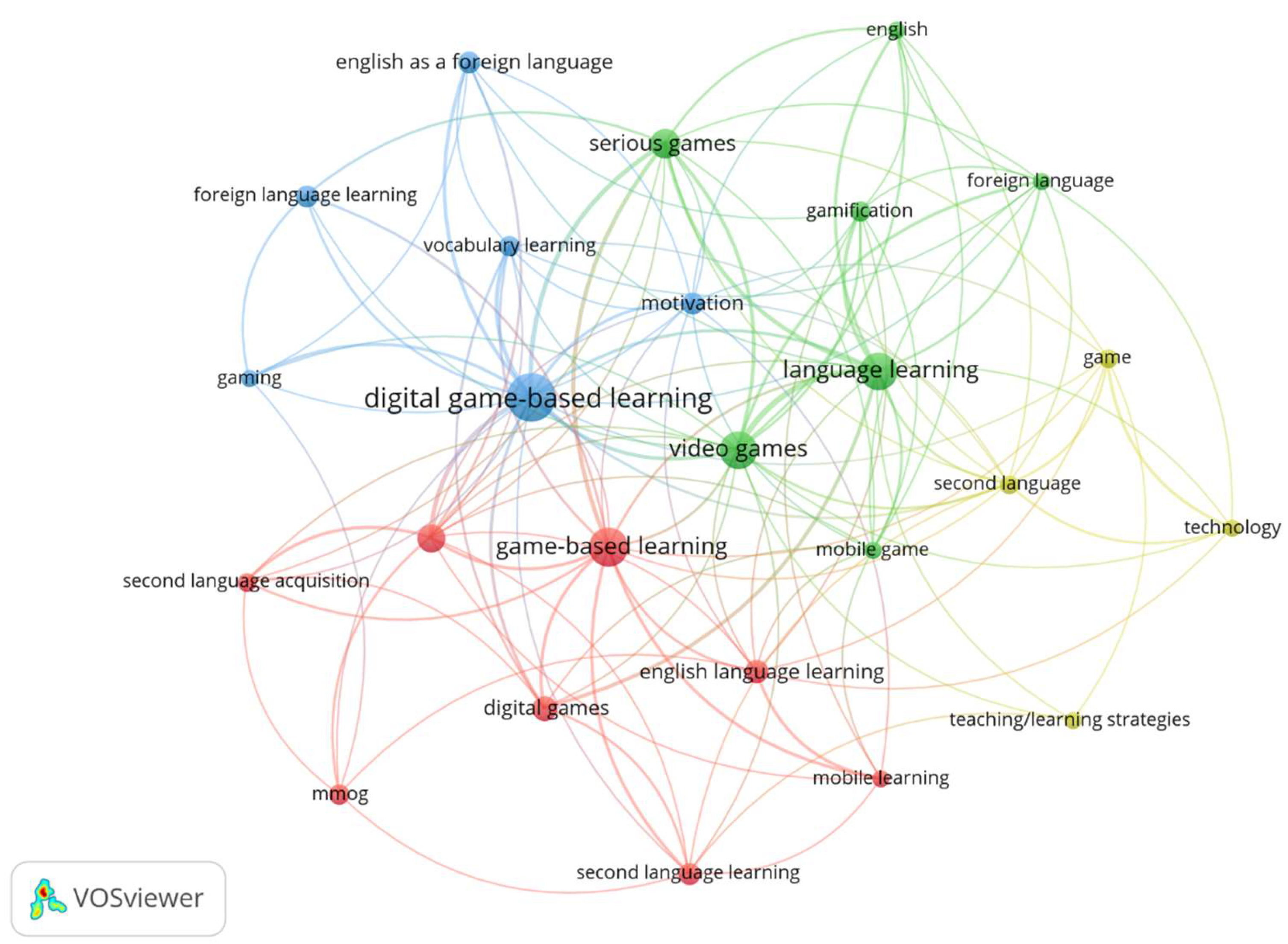

After normalising and eliminating duplicates, 574 author keywords were found, with a range of co-occurrence from 1 to 49. Applying Zipf’s law, it was estimated that the most prominent or most used keywords by authors should be 24 (square root of total author keywords, 23.95).

When performing the discrete count of author keywords and the documents in which they appeared, we found 21 keywords with 7 or more occurrences and 25 keywords with 6 or more, the latter being considered the most relevant keywords for the authors.

In

Figure 7 we can observe four distinct clusters: green, focusing on language learning, video games, foreign language and serious games; blue, collecting terms such as digital game-based learning, motivation and vocabulary learning; red, with game-based learning as the main focus and encompassing digital games, English language learning and second language learning; and yellow, focusing on second language, game and technology.

4. Discussion

This bibliometric analysis is the first to be carried out on terms related to video games and language learning and includes 238 documents. Unlike other bibliometric analyses on similar topics [

19,

20,

21,

22,

23,

24], it follows the traditional laws of bibliometrics, is unprecedented in terms of the subjects studied, and demonstrates the international interest in this topic, so it could be considered a pioneer in the field of study. We found an exponential growth trend in the number of papers found, with continuity of publication between 2009 and 2022, similar to other bibliometric studies related to video games and education [

23], augmented reality and language learning [

22] or serious games and education [

24]. However, although there are papers published since 2005, there is no continuity until 2009, with only two papers remaining from that period [

16,

25], which represents less than 1% of the publications collected in this study, indicating that it is a current, relevant and growing topic of interest.

The documents found were classified in 39 WoS categories, among which Educational Research (71%), Linguistics (29%) and Language Linguistics (21%) stand out, which makes sense as the search terms are related to language learning and it is in these areas of knowledge that efforts are being made to improve, innovate and explore new methodologies and didactics.

In the analysis of authors, we were able to find 490 authors, of which 29 were considered prolific, those with three or more papers. The authors with the highest number of published papers were Jie Chi Yang [

26,

27,

28,

29], Ricardo Casan-Pitarch [

30,

31,

32,

33,

34] and Gwo-Jen Hwang [

35,

36,

37,

38,

39]. Both the first and second focus their publications on new methodologies for second or foreign language teaching and the use of digital media for this purpose. The third, however, has a wider range of publications related to educational technology. These authors contrast drastically with the other bibliometric analyses compared, with the exception of G.-J. Hwang et al. (2023), where he himself appears.

For the analysis of the most cited papers, the h-index was used to select the 35 papers with more than 38 citations. Among these, the paper by Young et al. (2012) published in the Review of Educational Research with 417 citations and the paper by Thorne et al. (2009) published in The Model Language Journal with 267 citations stand out. Both were published in the first years of publication continuity (2009 and 2012) and served as a reference for future publications related to the objects of study. If we look at the authors with the highest number of citations, we can see that two of the three authors with the highest number of citations are prominent: Yang, with 4 of the most cited papers (233 citations in total), and Hwang, with 3 of the most cited papers (217 citations in total), consolidating their position as a reference in the field.

When analysing the journals, Bradford’s law was applied to verify that the distribution of the journals corresponded to the three differentiated zones: Core (36.13%), Zone I (27.31%) and Zone II (36.55%). Within Core, the journals with the highest number of published documents are Computer Assisted Language Learning (14 documents) and Recall (12 documents).

When analysing the countries of origin of co-authors, 48 countries were found, including the United States (48 papers), Taiwan (36 papers) and Spain (33 papers). Similarly, when analysing the countries with the highest number of citations, the United States (1966 citations), Taiwan (1076 citations) and China (548 citations) again stand out. These results partly coincide with studies that also find the USA to be the country with the most documents and citations [

20,

22,

24], although they differ in the countries that follow; others coincide in some of the three countries with the most publications or citations [

19,

21], although in a different order. This result is understandable, since the three countries with the most publications and citations are three of the most widely spoken languages in the world (English, Spanish and Chinese), but which also have other languages spoken in their territories (Spanish, Catalan, Basque, Galician, Taiwanese...).

On the other hand, in the analysis of the keywords provided by the authors, we highlight 25 keywords with more than 6 occurrences as the most relevant for the authors, among which we find terms such as “digital game-based learning” (49 occurrences), “game-based learning” (32 occurrences), “language learning” or “video games” (both 29 occurrences). As can be seen, the first two refer to pedagogical methods used to integrate video games into educational practice and the last two refer to the main study terms of this bibliometric analysis. In this part of the analysis, we found some coincidences with the keywords of the most relevant authors of other studies [

20,

21], in which “game-based learning” predominates, as both have a perspective oriented towards the didactic methodology of game-based learning.

In this bibliometric analysis we have identified the core journals and the most cited journals, highlighting the most prolific and prominent authors, the most relevant articles and the keywords most used by the authors. All of this provides us with very valuable information to carry out the analysis and facilitates the search for the most relevant authors with a view to possible future collaborations.

On the other hand, limitations were found in the collection of documents, as only the Web of Science database was used, so for future research or analyses of the same type, it would be advisable to include another database to include more documents and have a broader perspective of the results, in order to have a more complete analysis.

From a practical point of view, it would be useful to carry out research in the field of language learning in which video games are used as a didactic tool, regardless of whether they are commercial, serious or educational.

Finally, in terms of possible lines of future research, it would be interesting to analyse only experimental studies from different countries to see what types of methodologies are used to implement video games in the classroom with the aim of promoting language learning, whether it is a mother tongue, second and/or foreign language, and whether the results are really successful or not.

5. Conclusions

The USA was the country with the most papers and citations; Jie Chi Yang, Ricardo Casañ-Pitarch and Gwo-Jen Hwang were the most prolific co-authors; ’Our Princess Is in Another Castle: A Review of Trends in Serious Gaming for Education” was the most cited paper; Computer Assisted Language Learning was the most productive journal in the JCR ranking. The most used author keyword was “digital game-based learning”.

Looking at the data collected and seeing the exponential growth until 2023, and knowing that this year had not yet ended at the time of the document search, it can be concluded that there is a current interest among academics in video games and language learning as a whole. The research trend in educational sciences on the use of technology as a teaching tool is not new, but the increasing accessibility and supply of video games on the market opens up a huge range of possible video games that can be used in the classroom to teach any content and, of course, language learning, which does not have to appear as content, but learning can appear in a transversal or vehicular way. This interest comes from the field of educational science and language teaching research, not from the field of video games or technology.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.P-M. and M.R.; methodology, A.P-M. and M.R.; software, A.P-M..; validation, A.G-F., J.A-B.; formal analysis, A.P-M.; investigation, A.P-M.; resources, A.P-M.; data curation, A.P-M.; writing—original draft preparation, A.P-M.; writing—review and editing, A.G-F., M.R.; visualization, A.P-M.; supervision, J.A-B.; project administration, M.R.; funding acquisition, A.P-M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The author A.P-M. was supported by a grant from Junta de Extremadura and FSE+ from the European Union (PD23133).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable. There were no individual subjects involved in the process.

Data Availability Statement

Data available:

Acknowledgments

In this section, you can acknowledge any support given which is not covered by the author contribution or funding sections. This may include administrative and technical support, or donations in kind (e.g., materials used for experiments).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Ebrahimzadeh, M.; Alavi, S. The Effect of Digital Video Games on EFL Students’ Language Learning Motivation. Teach. Engl. Technol. 2017, 17, 87–112. [Google Scholar]

- Sylvén, L.K.; Sundqvist, P. Gaming as Extramural English L2 Learning and L2 Proficiency among Young Learners. ReCALL 2012, 24, 302–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Udjaja, Y.; Suri, P.A.; Gunawan, R.; Hartanto, F. Game-Based Learning Increase Japanese Language Learning through Video Game. Int. J. Adv. Comput. Sci. Appl. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newcombe, J.; Brick, B. Blending Video Games Into Language Learning. Int. J. Comput.-Assist. Lang. Learn. Teach. 2017, 7, 75–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reinders, H.; Wattana, S. Learn English or Die: The Effects of Digital Games on Interaction and Willingness to Communicate in a Foreign Language. Digit. Cult. Educ. 2011, 3, 4–28. [Google Scholar]

- Donthu, N.; Kumar, S.; Mukherjee, D.; Pandey, N.; Lim, W.M. How to Conduct a Bibliometric Analysis: An Overview and Guidelines. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 133, 285–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobrov, G.M.; Randolph, R.H.; Rauch, W.D. New Options for Team Research via International Computer Networks. Scientometrics 1979, 1, 387–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Price, D.D.S. A General Theory of Bibliometric and Other Cumulative Advantage Processes. J. Am. Soc. Inf. Sci. 1976, 27, 292–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lotka, A.J. The Frequency Distribution of Scientific Productivity. J. Wash. Acad. Sci. 1926, 16, 317–323. [Google Scholar]

- Hirsch, J.E. An Index to Quantify an Individual’s Scientific Research Output. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2005, 102, 16569–16572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bulick, S. Book Use as a Bradford-Zipf Phenomenon | Bulick | College & Research Libraries. 2017. [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Xu, Y.; Kitto, E.; Bradford, H.; Brooks, C. Promoting Culturally Sensitive Teacher Agency in Chinese Kindergarten Teachers: An Integrated Learning Approach. Early Years Int. J. Res. Dev. 2022, 42, 55–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nash-Stewart, C.E.; Kruesi, L.M.; Del Mar, C.B. Does Bradford’s Law of Scattering Predict the Size of the Literature in Cochrane Reviews? J. Med. Libr. Assoc. JMLA 2012, 100, 135–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venable, G.T.; Shepherd, B.A.; Loftis, C.M.; McClatchy, S.G.; Roberts, M.L.; Fillinger, M.E.; Tansey, J.B.; Klimo, P. Bradford’s Law: Identification of the Core Journals for Neurosurgery and Its Subspecialties. J. Neurosurg. 2016, 124, 569–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zipf, G.K. Selected Studies of the Principle of Relative Frequency in Language; Selected studies of the principle of relative frequency in language; Harvard Univ. Press: Oxford, England, 1932. [Google Scholar]

- Purushotma, R. Commentary: You’re Not Studying, You’re Just. Lang. Learn. Technol. 2005, 9, 80–96. [Google Scholar]

- Young, M.; Slota, S.; Cutter, A.; Jalette, G.; Mullin, G.; Lai, B.; Simeoni, Z.; Tran, M.; Yukhymenko, M. Our Princess Is in Another Castle: A Review of Trends in Serious Gaming for Education. Rev. Educ. Res. 2012, 82, 61–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorne, S.; Black, R.; Sykes, J. Second Language Use, Socialization, and Learning in Internet Interest Communities and Online Gaming. Mod. Lang. J. 2009, 93, 802–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camunas-Garcia, D.; Pilar Caceres-Reche, M.; de la Encarnacion Cambil-Hernandez, M. Mobile Game-Based Learning in Cultural Heritage Education: A Bibliometric Analysis. Educ. Train. 2023, 65, 324–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekin, C.C.; Gul, A. Bibliometric Analysis of Game-Based Researches in Educational Research. Int. J. Technol. Educ. 2022, 5, 499–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, G.-J.; Chen, P.-Y.; Chu, S.-T.; Chuang, W.-H.; Juan, C.-Y.; Chen, H.-Y. Game-Based Language Learning in Technological Contexts: An Integrated Systematic Review and Bibliometric Analysis. Int. J. ONLINE PEDAGOGY COURSE Des. 2023, 13, 316184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Min, W.; Yu, Z. A Bibliometric Analysis of Augmented Reality in Language Learning. SUSTAINABILITY 2023, 15, 7235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortiz-Clavijo, L.F.; Cardona-Valencia, D. Trends and Challenges of Video Games as an Educational Tool. Rev. Colomb. Educ. 2022, e211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyni, J.; Tarkiainen, A.; Lopez-Pernas, S.; Saqr, M.; Kahila, J.; Bednarik, R.; Tedre, M. Games and Rewards: A Scientometric Study of Rewards in Educational and Serious Games. IEEE ACCESS 2022, 10, 31578–31585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- deHaan, J. Acquisitoin of Japanese as a Foreign Language through a Baseball Video Game. FOREIGN Lang. Ann. 2005, 38, 278–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Quadir, B.; Chen, N. Effects of the Badge Mechanism on Self-Efficacy and Learning Performance in a Game-Based English Learning Environment. J. Educ. Comput. Res. 2016, 54, 371–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Lin, M.; Chen, S. Effects of Anxiety Levels on Learning Performance and Gaming Performance in Digital Game-Based Learning. J. Comput. Assist. Learn. 2018, 34, 324–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Quadir, B.; Chen, N. Effects of Children’s Trait Emotional Intelligence on Digital Game-Based Learning. Int. J. Hum.-Comput. Interact. 2019, 35, 374–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Quadir, B. Effects of Prior Knowledge on Learning Performance and Anxiety in an English Learning Online Role-Playing Game. Educ. Technol. Soc. 2018, 21, 174–185. [Google Scholar]

- Casañ-Pitarch, R. Gamifying Content and Language Integrated Learning with Serious Videogames. J. Lang. Educ. 2017, 3, 107–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casañ-Pitarch, R. Storyline-Based Videogames in the FL Classroom. Digit. Educ. Rev. 2017, 80–92. [Google Scholar]

- Casañ-Pitarch, R. Language for Specific Purposes and Graphic-Adventure Videogames: Supporting Content and Language Learning. OBRA Digit.-Rev. Comun. 2017, 169–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casañ-Pitarch, R.; Gong, J. Testing ImmerseMe with Chinese Students: Acquisition of Foreign Language Forms and Vocabulary in Spanish. Lang. Learn. High. Educ. 2021, 11, 219–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casañ-Pitarch, R.; Wang, L. Spanish B1 Vocabulary Acquisition among Chinese Students with Guadalingo. Int. J. Inf. Learn. Technol. 2022, 39, 197–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, S.; Hwang, G.; Chien, S.; Chang, S. Incorporating Teacher Intelligence into Digital Games: An Expert System-Guided Self-Regulated Learning Approach to Promoting EFL Students’ Performance in Digital Gaming Contexts. Br. J. Educ. Technol. 2023, 54, 534–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hung, H.; Yang, J.; Hwang, G.; Chu, H.; Wang, C. A Scoping Review of Research on Digital Game-Based Language Learning. Comput. Educ. 2018, 126, 89–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, W.; Shih, T.; Ma, Z.; Shadiev, R.; Chen, S. Evaluating Listening and Speaking Skills in a Mobile Game-Based Learning Environment with Situational Contexts. Comput. Assist. Lang. Learn. 2016, 29, 639–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.; Hwang, G.; Fu, Q.; Cao, Y. Facilitating EFL Students’ English Grammar Learning Performance and Behaviors: A Contextual Gaming Approach. Comput. Educ. 2020, 152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Hwang, G. Effects of Metalinguistic Corrective Feedback on Novice EFL Students’ Digital Game-Based Grammar Learning Performances, Perceptions and Behavioural Patterns. Br. J. Educ. Technol. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).