Submitted:

20 March 2025

Posted:

24 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Dependence of Protein Adsorption on the Particle Morphology

2.1. Size and Shape

2.2. Surface Morphology

2.3. Structure

3. Dependence of Protein Adsorption on the Physicochemical Properties of Particles

3.1. Composition

3.2. Stiffness

3.3. Surface Chemistry

4. Surface Modifications Affecting Protein Adsorption on Particles

4.1. Surface Modification with Hydrophilic Polymers

4.2. Surface Modification with Zwitterionic Polymers

4.3. Surface Modification with Proteins

5. Other Factors Affecting Protein Adsorption

5.1. Protein Type

5.2. Incubation Medium

6. Effect of Protein Adsorption on Particle–Cell Interactions

6.1. Targeted Delivery

6.2. Cellular Uptake

7. Conclusions and Outlook

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| NP | Nanoparticle |

| MP | Microparticle |

| PLGA | Poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) |

| PS | Polystyrene |

| PEG | Polyethylene glycol |

| BSA | Bovine serum protein |

| ELP | Elastin-like polypeptide |

| HDL | High-density lipoprotein |

| MAA | Methacrylic acid co-methyl methacrylate |

| PMMA | Polymethyl methacrylate |

| PCL | Poly(ε-caprolactone) |

| ApoE | Apolipoprotein E |

| FBS | Fetal blood serum |

| PS-b-PEG | Poly(styrene)-block-poly(ethylene glycol) |

| LDH | Layered double hydroxide |

| HES | Hydroxyethyl starch |

| PEG-b-AGE | Allyl glycidyl ether |

| PEEP | Poly(ethyl ethylene phosphate) |

| ApoJ | Apolipoprotein J |

| HMPB | 4-(4-hydroxymethyl-3-methoxyphenoxy)-butyric acid |

| PEI | Polyethylenimine |

| MPC | Phosphorylcholine methacrylate |

| BALF | Bronchoalveolar lavage fluid |

| PGMA | Poly(glycidyl methacrylate) |

| CBMA | Carboxybetaine methacrylate |

| SBMA | Sulfobetaine methacrylate |

| PMPC | Poly(2-methacryloyloxyethyl phosphorylcholine) |

| PCL–PDEAPS | PCL–(N-(3-sulfopropyl-N-methacryloxyethy-N,N-diethylammonium betaine) |

| PHBHHx | Poly-3-hydroxybutyrate-co-3-hydroxyhexanoate |

| CHO | Chinese hamster ovar |

| CTAB | Cetriltrimethylammonium bromide |

| PDDAC | Poly-diallyldimethylammonium chloride |

References

- Nifontova, G.; Tsoi, T.; Karaulov, A.; Nabiev, I.; Sukhanova, A. Structure–function relationships in polymeric multilayer capsules designed for cancer drug delivery. Biomater. Sci. 2022, 10, 5092–5115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Afzal, O.; Altamimi, A.S.A.; Nadeem, M.S.; Alzarea, S.I.; Almalki, W.H.; Tariq, A.; Mubeen, B.; Murtaza, B.N.; Iftikhar, S.; Riaz, N.; et al. Nanoparticles in drug delivery: From history to therapeutic applications. Nanomaterials 2022, 12, 4494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siddique, S.; Chow, J.C.L. Application of nanomaterials in biomedical imaging and cancer therapy. Nanomaterials 2020, 10, 1700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mazetyte-Stasinskiene, R.; Köhler, J.M. Sensor micro and nanoparticles for microfluidic application. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 8353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grasso, G.; Colella, F.; Forciniti, S.; Onesto, V.; Iuele, H.; Siciliano, A.C.; Carnevali, F.; Chandra, A.; Gigli, G.; del Mercato, L.L. Fluorescent nano-and microparticles for sensing cellular microenvironment: past, present and future applications. Nanoscale Adv. 2023, 5, 4311–4336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Zheng, H.; Schumacher, D.; Liehn, E.A.; Slabu, I.; Rusu, M. Recent advancements of specific functionalized surfaces of magnetic nano-and microparticles as a theranostics source in biomedicine. ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng. 2021, 7, 1914–1932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monopoli, M.P.; Åberg, C.; Salvati, A.; Dawson, K.A. Biomolecular coronas provide the biological identity of nanosized materials. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2012, 7, 779–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, R.; Chen, C. The crown and the scepter: roles of the protein corona in nanomedicine. Adv. Mater. 2019, 31, 1805740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Álvarez, R.; Hadjidemetriou, M.; Sánchez-Iglesias, A.; Liz-Marzán, L.M.; Kostarelos, K. In vivo formation of protein corona on gold nanoparticles. The effect of their size and shape. Nanoscale 2018, 10, 1256–1264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bewersdorff, T.; Glitscher, E.A.; Bergueiro, J.; Eravci, M.; Miceli, E.; Haase, A.; Calderón, M. The influence of shape and charge on protein corona composition in common gold nanostructures. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2020, 117, 111270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tenzer, S.; Docter, D.; Kuharev, J.; Musyanovych, A.; Fetz, V.; Hecht, R.; Schlenk, F.; Fischer, D.; Kiouptsi, K.; Reinhardt, C.; et al. Rapid formation of plasma protein corona critically affects nanoparticle pathophysiology. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2013, 8, 772–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

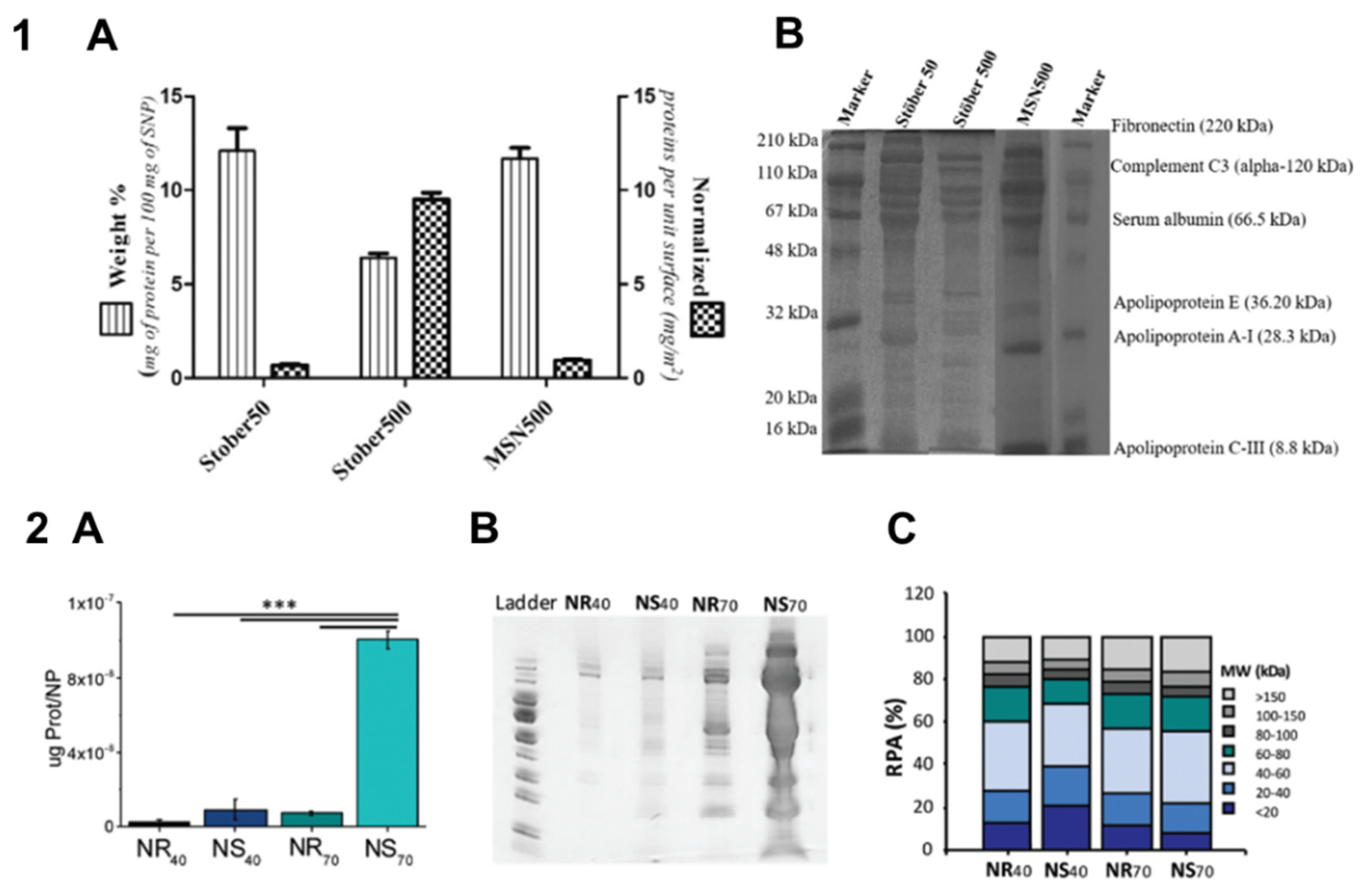

- Saikia, J.; Yazdimamaghani, M.; Hadipour Moghaddam, S.P.; Ghandehari, H. Differential protein adsorption and cellular uptake of silica nanoparticles based on size and porosity. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2016, 8, 34820–34832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clemments, A.M.; Botella, P.; Landry, C.C. Spatial mapping of protein adsorption on mesoporous silica nanoparticles by stochastic optical reconstruction microscopy. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139, 3978–3981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sempf, K.; Arrey, T.; Gelperina, S.; Schorge, T.; Meyer, B.; Karas, M.; Kreuter, J. Adsorption of plasma proteins on uncoated PLGA nanoparticles. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 2013, 85, 53–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ottonelli, I.; Duskey, J.T.; Genovese, F.; Pederzoli, F.; Caraffi, R.; Valenza, M.; Tosi, G.; Vandelli, M.A.; Ruozi, B. Quantitative comparison of the protein corona of nanoparticles with different matrices. Int. J. Pharm. X 2022, 4, 100136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ndumiso, M.; Buchtová, N.; Husselmann, L.; Mohamed, G.; Klein, A.; Aucamp, M.; Canevet, D.; D’Souza, S.; Maphasa, R.E.; Boury, F.; et al. Comparative whole corona fingerprinting and protein adsorption thermodynamics of PLGA and PCL nanoparticles in human serum. Colloids Surfaces B Biointerfaces 2020, 188, 110816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blume, J.E.; Manning, W.C.; Troiano, G.; Hornburg, D.; Figa, M.; Hesterberg, L.; Platt, T.L.; Zhao, X.; Cuaresma, R.A.; Everley, P.A.; et al. Rapid, deep and precise profiling of the plasma proteome with multi-nanoparticle protein corona. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 3662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Oliveira, F.A.; Albuquerque, L.J.C.; Castro, C.E.; Riske, K.A.; Bellettini, I.C.; Giacomelli, F.C. Reduced cytotoxicity of nanomaterials driven by nano-bio interactions: Case study of single protein coronas enveloping polymersomes. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 2022, 213, 112387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seifert, B.; Baudis, S.; Wischke, C. Composition-Dependent Protein–Material Interaction of Poly (Methyl Methacrylate-co-styrene) Nanoparticle Series. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 16390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obst, K.; Yealland, G.; Balzus, B.; Miceli, E.; Dimde, M.; Weise, C.; Eravci, M.; Bodmeier, R.; Haag, R.; Calderón, M.; et al. Protein corona formation on colloidal polymeric nanoparticles and polymeric nanogels: impact on cellular uptake, toxicity, immunogenicity, and drug release properties. Biomacromolecules 2017, 18, 1762–1771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundqvist, M.; Stigler, J.; Elia, G.; Lynch, I.; Cedervall, T.; Dawson, K.A. Nanoparticle size and surface properties determine the protein corona with possible implications for biological impacts. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2008, 105, 14265–14270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, B.; Wu, Z.; Tian, M.; Feng, T.; Yuanwei, C.; Luo, X. Effect of surface morphology change of polystyrene microspheres through etching on protein corona and phagocytic uptake. J. Biomater. Sci. Polym. Ed. 2020, 31, 2381–2395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ritz, S.; Schöttler, S.; Kotman, N.; Baier, G.; Musyanovych, A.; Kuharev, J.; Landfester, K.; Schild, H.; Jahn, O.; Tenzer, S.; et al. Protein corona of nanoparticles: distinct proteins regulate the cellular uptake. Biomacromolecules 2015, 16, 1311–1321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

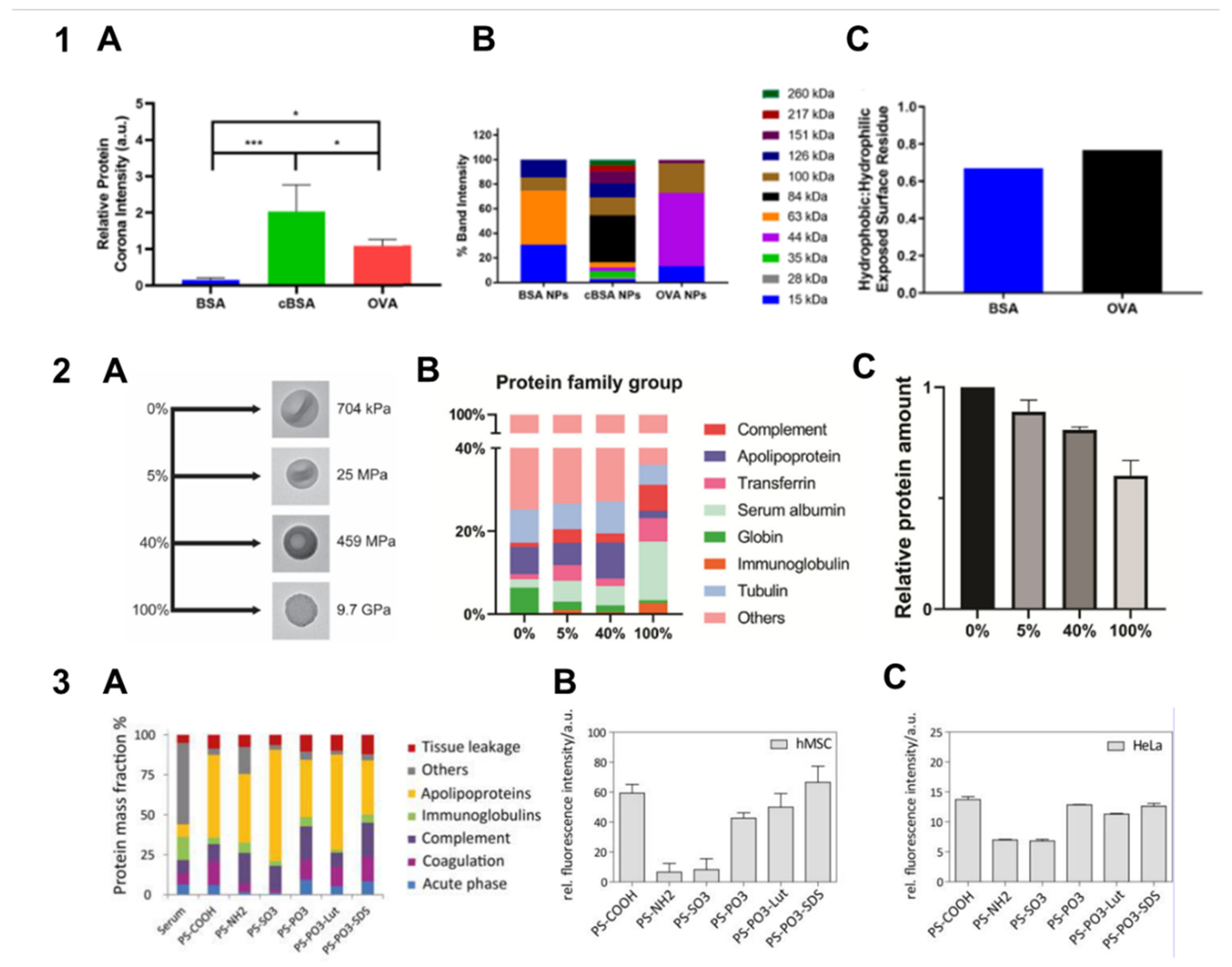

- Pustulka, S.M.; Ling, K.; Pish, S.L.; Champion, J.A. Protein nanoparticle charge and hydrophobicity govern protein corona and macrophage uptake. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2020, 12, 48284–48295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Huang, Z.; Li, Y.; Wang, W.; Shi, J.; Fu, F.; Huang, Y.; Pan, X.; Wu, C. Impact of particle size and pH on protein corona formation of solid lipid nanoparticles: A proof-of-concept study. Acta Pharm. Sin. B 2021, 11, 1030–1046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, F.; Liu, M.; Li, G.; Chen, B.; Chu, Y.; Yang, Y.; Wu, E.; Yu, Y.; Lin, S.; Ding, T.; et al. Phospholipid type regulates protein corona composition and in vivo performance of lipid nanodiscs. Mol. Pharm. 2024, 21, 2272–2283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.; Parayath, N.; Ganesh, S.; Wang, W.; Amiji, M. The role of apolipoprotein-and vitronectin-enriched protein corona on lipid nanoparticles for in vivo targeted delivery and transfection of oligonucleotides in murine tumor models. Nanoscale 2019, 11, 18806–18824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strojan, K.; Leonardi, A.; Bregar, V.B.; Križaj, I.; Svete, J.; Pavlin, M. Dispersion of nanoparticles in different media importantly determines the composition of their protein corona. PLoS One 2017, 12, e0169552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brückner, M.; Simon, J.; Jiang, S.; Landfester, K.; Mailänder, V. Preparation of the protein corona: How washing shapes the proteome and influences cellular uptake of nanocarriers. Acta Biomater. 2020, 114, 333–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilardo, R.; Traldi, F.; Vdovchenko, A.; Resmini, M. Influence of surface chemistry and morphology of nanoparticles on protein corona formation. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Nanomed. Nanobiotechnol. 2022, 14, e1788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suvarna, M.; Dyawanapelly, S.; Kansara, B.; Dandekar, P.; Jain, R. Understanding the stability of nanoparticle–protein interactions: effect of particle size on adsorption, conformation and thermodynamic properties of serum albumin proteins. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2018, 1, 5524–5535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima, T.; Bernfur, K.; Vilanova, M.; Cedervall, T. Understanding the lipid and protein corona formation on different sized polymeric nanoparticles. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 1129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, W.; Xiong, J.; Zhang, S.; Xiong, Y.; Zhang, H.; Gao, H. Influence of ligands property and particle size of gold nanoparticles on the protein adsorption and corresponding targeting ability. Int. J. Pharm. 2018, 538, 105–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clemments, A.M.; Botella, P.; Landry, C.C. Protein adsorption from biofluids on silica nanoparticles: corona analysis as a function of particle diameter and porosity. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2015, 7, 21682–21689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahniuk, M.S.; Alshememry, A.K.; Unsworth, L.D. Human plasma protein adsorption to elastin-like polypeptide nanoparticles. Biointerphases 2020, 15, 021007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marichal, L.; Klein, G.; Armengaud, J.; Boulard, Y.; Chédin, S.; Labarre, J.; Pin, S.; Renault, J.P.; Aude, J.C. Protein corona composition of silica nanoparticles in complex media: Nanoparticle size does not matter. Nanomaterials 2020, 10, 240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, G.J.; Jeong, J.Y.; Kang, J.; Cho, W.; Han, S.Y. Size dependence unveiling the adsorption interaction of high-density lipoprotein particles with PEGylated gold nanoparticles in biomolecular corona formation. Langmuir 2021, 37, 9755–9763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satzer, P.; Svec, F.; Sekot, G.; Jungbauer, A. Protein adsorption onto nanoparticles induces conformational changes: Particle size dependency, kinetics, and mechanisms. Eng. Life Sci. 2016, 16, 238–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Liu, Q.; Yang, F.; Yu, H.; Xie, Y.; Yao, W. Submicron-size polystyrene modulates amyloid fibril formation: From the perspective of protein corona. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 2022, 218, 112736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuschnerus, I.; Giri, K.; Ruan, J.; Huang, Y.; Bedford, N.; Garcia-Bennett, A. On the growth of the soft and hard protein corona of mesoporous silica particles with varying morphology. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2022, 612, 467–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visalakshan, R.M.; González García, L.E.; Benzigar, M.R.; Ghazaryan, A.; Simon, J.; Mierczynska-Vasilev, A.; Michl, T.D.; Vinu, A.; Mailänder, V.; Morsbach, S.; et al. The influence of nanoparticle shape on protein corona formation. Small 2020, 16, 2000285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qiao, L.; Zhou, Q.; Du, K. Protein adsorption to diethylaminoethyl-dextran grafted macroporous cellulose microspheres: A critical pore size for enhanced adsorption capacity and uptake kinetic. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2023, 314, 123588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, Q.; Yan, Y.; Ang, C.S.; Kempe, K.; Kamphuis, M.M.J.; Dodds, S.J.; Caruso, F. Monoclonal antibody-functionalized multilayered particles: targeting cancer cells in the presence of protein coronas. ACS Nano 2015, 9, 2876–2885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gerasimovich, E.; Kriukova, I.; Shishkov, V.V.; Efremov, Y.M.; Timashev, P.S.; Karaulov, A.; Nabiev, I.; Sukhanova, A. Interaction of serum and plasma proteins with polyelectrolyte microparticles with core/shell and shell-only structures. ACS Omega 2024, 9, 29739–29750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wells, L.A.; Guo, H.; Emili, A.; Sefton, M.V. The profile of adsorbed plasma and serum proteins on methacrylic acid copolymer beads: Effect on complement activation. Biomaterials 2017, 118, 74–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coron, A.; Fonseca, D.M.; Sharma, A.; Slupphaug, G.; Strand, B.L.; Rokstad, A.M.A. MS-proteomics provides insight into the host responses towards alginate microspheres. Mater. Today Bio 2022, 17, 100490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Luan, Y.; Dai, W. Int. Dynamic process, mechanisms, influencing factors and study methods of protein corona formation. J. Biol. Macromol. 2022, 205, 731–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dal Magro, R.; Ornaghi, F.; Cambianica, I.; Beretta, S.; Re, F.; Musicanti, C.; Rigolio, R.; Donzelli, E.; Canta, A.; Ballarini, E.; et al. ApoE-modified solid lipid nanoparticles: A feasible strategy to cross the blood-brain barrier. J. Control. Release 2017, 249, 103–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vyner, M.C.; Amsden, B.G. Polymer chain flexibility-induced differences in fetuin A adsorption and its implications on cell attachment and proliferation. Acta Biomater. 2016, 31, 89–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tengjisi; Hui, Y.; Fan, Y.; Zou, D.; Talbo, G.H.; Yang, G.; Zhao, C.X. Influence of nanoparticle mechanical property on protein corona formation. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2022, 606, 1737–1744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Jin, X.; Liu, T.; Fan, F.; Gao, F.; Chai, S.; Yang, L. Nanoparticle elasticity affects systemic circulation lifetime by modulating adsorption of apolipoprotein AI in corona formation. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 4137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buck, E.; Lee, S.; Stone, L.S.; Cerruti, M. Protein adsorption on surfaces functionalized with COOH groups promotes anti-inflammatory macrophage responses. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2021, 13, 7021–7036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miao, Y.; Li, L.; Wang, Y.; Wang, J.; Zhou, Y.; Guo, L.; Zhao, Y.; Nie, D.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, X.; et al. Regulating protein corona on nanovesicles by glycosylated polyhydroxy polymer modification for efficient drug delivery. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 1159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilson, B.K.; Yang, H.; Prud’homme, R.K. Polyelectrolyte-Doped Block Copolymer-Stabilized Nanocarriers for Continuous Tunable Surface Charge. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2024, 7, 11071–11079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spreen, H.; Behrens, M.; Mulac, D.; Humpf, H.U.; Langer, K. Identification of main influencing factors on the protein corona composition of PLGA and PLA nanoparticles. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 2021, 163, 212–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catalano, F.; Alberto, G.; Ivanchenko, P.; Dovbeshko, G.; Martra, G. Effect of silica surface properties on the formation of multilayer or submonolayer protein hard corona: Albumin adsorption on pyrolytic and colloidal SiO2 nanoparticles. J. Phys. Chem. C 2015, 119, 26493–26505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brouwer, H.; Porbahaie, M.; Boeren, S.; Busch, M.; Bouwmeester, H. The in vitro gastrointestinal digestion-associated protein corona of polystyrene nano-and microplastics increases their uptake by human THP-1-derived macrophages. Part. Fibre Toxicol. 2024, 21, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorsch, A.; Förschner, F.; Ravandeh, M.; da Silva Brito, W.A.; Saadati, F.; Delcea, M.; Wende, K.; Bekeschus, S. Nanoplastic size and surface chemistry dictate decoration by human saliva proteins. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2024, 16, 25977–25993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Partikel, K.; Korte, R.; Stein, N.C.; Mulac, D.; Herrmann, F.C.; Humpf, H.U.; Langer, K. Effect of nanoparticle size and PEGylation on the protein corona of PLGA nanoparticles. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 2019, 141, 70–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Z.; Adnan, N.N.M.; Wang, G.; Rawal, A.; Shi, B.; Liu, R.; Liang, K.; Zhao, L.; Gooding, J.J.; Boyer, C.; et al. Enhanced colloidal stability and protein resistance of layered double hydroxide nanoparticles with phosphonic acid-terminated PEG coating for drug delivery. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2018, 521, 242–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, N.; Jia, Y.; Bai, S.; Yang, Y.; Dai, L.; Li, J. Spatial mapping and quantitative evaluation of protein corona on PEGylated mesoporous silica particles by super-resolution fluorescence microscopy. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2024, 653, 351–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galdino, F.E.; Picco, A.S.; Sforca, M.L.; Cardoso, M.B.; Loh, W. Effect of particle functionalization and solution properties on the adsorption of bovine serum albumin and lysozyme onto silica nanoparticles. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 2020, 186, 110677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- von Baeckmann, C.; Kählig, H.; Lindén, M.; Kleitz, F. On the importance of the linking chemistry for the PEGylation of mesoporous silica nanoparticles. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2021, 589, 453–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karim, M.E.; Chowdhury, E.H. PEGylated Strontium Sulfite nanoparticles with spontaneously formed surface-embedded protein Corona restrict off-target distribution and accelerate breast tumour-selective delivery of siRNA. J. Funct. Biomater. 2022, 13, 211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, B.; Okwieka, P.; Schöttler, S.; Winzen, S.; Langhanki, J.; Mohr, K.; Opatz, T.; Mailänder, V.; Landfester, K.; Wurm, F.R. Carbohydrate-based nanocarriers exhibiting specific cell targeting with minimum influence from the protein corona. Angew. Chemie—Int. Ed. 2015, 54, 7436–7440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, B.; Okwieka, P.; Schöttler, S.; Seifert, O.; Kontermann, R.E.; Pfizenmaier, K.; Musyanovych, A.; Meyer, R.; Diken, M.; Sahin, U.; et al. Tailoring the stealth properties of biocompatible polysaccharide nanocontainers. Biomaterials 2015, 49, 125–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, Q.; Walkey, C.; Chan, W.C.W. Polyethylene glycol backfilling mitigates the negative impact of the protein corona on nanoparticle cell targeting. Angew. Chemie—Int. Ed. 2014, 53, 5093–5096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Lin, R.; Wang, L.; Huang, J.; Wu, H.; Cheng, G.; Zhou, Z.; MacDonald, T.; Yang, L.; Mao, H. PEG-b-AGE polymer coated magnetic nanoparticle probes with facile functionalization and anti-fouling properties for reducing non-specific uptake and improving biomarker targeting. J. Mater. Chem. B 2015, 3, 3591–3603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Negro, M.; Russo, D.; Prévost, S.; Teixeira, J.; Morsbach, S.; Landfester, K. Poly (ethylene glycol)-based surfactant reduces the conformational change of adsorbed proteins on nanoparticles. Biomacromolecules 2022, 23, 4282–4288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, J.N.; Xie, H.G.; Yu, W.T.; Liu, X.D.; Xie, W.Y.; Zhu, J.; Ma, X.J. Chitosan-g-MPEG-modified alginate/chitosan hydrogel microcapsules: A quantitative study of the effect of polymer architecture on the resistance to protein adsorption. Langmuir 2010, 26, 17156–17164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Jiang, S.; Simon, J.; Paßlick, D.; Frey, M.L.; Wagner, M.; Mailänder, V.; Crespy, D.; Landfester, K. Brush conformation of polyethylene glycol determines the stealth effect of nanocarriers in the low protein adsorption regime. Nano Lett. 2021, 21, 1591–1598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schöttler, S.; Becker, G.; Winzen, S.; Steinbach, T.; Mohr, K.; Landfester, K.; Mailänder, V.; Wurm, F.R. Protein adsorption is required for stealth effect of poly (ethylene glycol)-and poly (phosphoester)-coated nanocarriers. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2016, 11, 372–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perera, Y.R.; Xu, J.X.; Amarasekara, D.L.; Hughes, A.C.; Abbood, I.; Fitzkee, N.C. Understanding the adsorption of peptides and proteins onto PEGylated gold nanoparticles. Molecules 2021, 26, 5788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cui, T.; Ma, Y.; Yang, J.Y.; Liu, S.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, F.; Wang, J.; Cai, T.; Dong, L.; Hong, J.; et al. Protein corona-guided tumor targeting therapy via the surface modulation of low molecular weight PEG. Nanoscale 2021, 13, 5883–5891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zalba, S.; ten Hagen, T.L.M.; Burgui, C.; Garrido, M.J. Stealth nanoparticles in oncology: Facing the PEG dilemma. J. Control. Release 2022, 351, 22–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ju, Y.; Kelly, H.G.; Dagley, L.F.; Reynaldi, A.; Schlub, T.E.; Spall, S.K.; Bell, C.A.; Cui, J.; Mitchell, A.J.; Lin, Z.; et al. Person-specific biomolecular coronas modulate nanoparticle interactions with immune cells in human blood. ACS Nano 2020, 14, 15723–15737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papi, M.; Caputo, D.; Palmieri, V.; Coppola, R.; Palchetti, S.; Bugli, F.; Martini, C.; Digiacomo, L.; Pozzi, D.; Caracciolo, G. Clinically approved PEGylated nanoparticles are covered by a protein corona that boosts the uptake by cancer cells. Nanoscale 2017, 9, 10327–10334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Sun, F.; Liu, S.; Jiang, S. Anti-PEG antibodies in the clinic: Current issues and beyond PEGylation. J. Control. Release 2016, 244, 184–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grenier, P.; de, O. Viana, I.M.; Lima, E.M.; Bertrand, N. Anti-polyethylene glycol antibodies alter the protein corona deposited on nanoparticles and the physiological pathways regulating their fate in vivo. J. Control. Release 2018, 287, 121–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thi, T.T.H.; Pilkington, E.H.; Nguyen, D.H.; Lee, J.S.; Park, K.D.; Truong, N.P. The importance of poly (ethylene glycol) alternatives for overcoming PEG immunogenicity in drug delivery and bioconjugation. Polymers (Basel). 2020, 12, 298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, Y.; Ito, S.; Yoshino, F.; Suzuki, Y.; Zhao, L.; Komatsu, N. Polyglycerol grafting shields nanoparticles from protein corona formation to avoid macrophage uptake. ACS Nano 2020, 14, 7216–7226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weber, C.; Voigt, M.; Simon, J.; Danner, A.K.; Frey, H.; Mailänder, V.; Helm, M.; Morsbach, S.; Landfester, K. Functionalization of liposomes with hydrophilic polymers results in macrophage uptake independent of the protein corona. Biomacromolecules 2019, 20, 2989–2999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Müller, J.; Bauer, K.N.; Prozeller, D.; Simon, J.; Mailänder, V.; Wurm, F.R.; Winzen, S.; Landfester, K. Coating nanoparticles with tunable surfactants facilitates control over the protein corona. Biomaterials 2017, 115, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koshkina, O.; Westmeier, D.; Lang, T.; Bantz, C.; Hahlbrock, A.; Würth, C.; Resch-Genger, U.; Braun, U.; Thiermann, R.; Weise, C.; et al. Tuning the surface of nanoparticles: impact of poly (2-ethyl-2-oxazoline) on protein adsorption in serum and cellular uptake. Macromol. Biosci. 2016, 16, 1287–1300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García, K.P.; Zarschler, K.; Barbaro, L.; Barreto, J.A.; O’Malley, W.; Spiccia, L.; Stephan, H.; Graham, B. Zwitterionic-coated “stealth” nanoparticles for biomedical applications: recent advances in countering biomolecular corona formation and uptake by the mononuclear phagocyte system. Small 2014, 10, 2516–2529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, W.; Ma, G.; Ji, F.; Zhang, J.; Wang, L.; Sun, H.; Chen, S. Biocompatible long-circulating star carboxybetaine polymers. J. Mater. Chem. B 2015, 3, 440–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khung, Y.L.; Narducci, D. Surface modification strategies on mesoporous silica nanoparticles for anti-biofouling zwitterionic film grafting. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 2015, 226, 166–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safavi-Sohi, R.; Maghari, S.; Raoufi, M.; Jalali, S.A.; Hajipour, M.J.; Ghassempour, A.; Mahmoudi, M. Bypassing protein corona issue on active targeting: Zwitterionic coatings dictate specific interactions of targeting moieties and cell receptors. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2016, 8, 22808–22818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Cheng, F.; Shen, W.; Cheng, G.; Zhao, J.; Peng, W.; Qu, J. Amino acid-based anti-fouling functionalization of silica nanoparticles using divinyl sulfone. Acta Biomater. 2016, 40, 273–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Overby, C.; Park, S.; Summers, A.; Benoit, D.S.W. Zwitterionic peptides: Tunable next-generation stealth nanoparticle modifications. Bioact. Mater. 2023, 27, 113–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, F.; Chen, K.; Xu, H.; Gu, H. Functional short-chain zwitterion coated silica nanoparticles with antifouling property in protein solutions. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 2015, 126, 251–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, F.; Chen, K.; Xu, H.; Gu, H. Design and preparation of bi-functionalized short-chain modified zwitterionic nanoparticles. Acta Biomater. 2018, 72, 239–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Estupiñán, D.; Bannwarth, M.B.; Mylon, S.E.; Landfester, K.; Muñoz-Espí, R.; Crespy, D. Design and preparation of bi-functionalized short-chain modified zwitterionic nanoparticles. Nanoscale 2016, 8, 3019–3030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loiola, L.M.D.; Batista, M.; Capeletti, L.B.; Mondo, G.B.; Rosa, R.S.M.; Marques, R.E.; Bajgelman, M.C.; Cardoso, M.B. Shielding and stealth effects of zwitterion moieties in double-functionalized silica nanoparticles. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2019, 553, 540–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, S.; Park, S.; Choi, D.; Hong, J. Efficient drug delivery carrier surface without unwanted adsorption using sulfobetaine zwitterion. Adv. Mater. Interfaces 2020, 7, 2001433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, H.; Sun, Q.; Kong, F.; Dong, H.; Ma, M.; Liu, F.; Wang, C.; Xu, H.; Gu, N.; Zhang, Y. Zwitterion-functionalized hollow mesoporous Prussian blue nanoparticles for targeted and synergetic chemo-photothermal treatment of acute myeloid leukemia. J. Mater. Chem. B 2021, 9, 5245–5254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knowles, B.R.; Wagner, P.; Maclaughlin, S.; Higgins, M.J.; Molino, P.J. Carboxybetaine functionalized nanosilicas as protein resistant surface coatings. Biointerphases 2020, 15, 011001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gessner, I.; Park, J.H.; Lin, H.Y.; Lee, H.; Weissleder, R. Magnetic gold nanoparticles with idealized coating for enhanced point-of-care sensing. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 2021, 11, 2102035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez-Salcedo, S.; Vallet-Regí, M.; Shahin, S.A.; Glackin, C.A.; Zink, J.I. Mesoporous core-shell silica nanoparticles with anti-fouling properties for ovarian cancer therapy. Chem. Eng. J. 2018, 340, 114–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, B.M.; Fiegel, J. Zwitterionic polymer coatings enhance gold nanoparticle stability and uptake in various biological environments. AAPS J. 2022, 24, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koubková, J.; Macková, H.; Proks, V.; Trchová, M.; Brus, J.; Horák, D. RAFT of sulfobetaine for modifying poly (glycidyl methacrylate) microspheres to reduce nonspecific protein adsorption. J. Polym. Sci. Part A Polym. Chem. 2015, 53, 2273–2284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Z.; Wei, T.; Ge, R.; Li, Q.; Liu, B.; Ji, Z.; Chen, L.; Zhu, J.; Shen, J.; Liu, Z.; et al. Microfluidic production of zwitterion coating microcapsules with low foreign body reactions for improved islet transplantation. Small 2022, 18, 2202596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, K.; Hu, F.; Gu, H.; Xu, H. Tuning of surface protein adsorption by spherical mixed charged silica brushes (MCB) with zwitterionic carboxybetaine component. J. Mater. Chem. B 2017, 5, 435–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weiss, A.C.G.; Kempe, K.; Förster, S.; Caruso, F. Microfluidic examination of the “hard” biomolecular corona formed on engineered particles in different biological milieu. Biomacromolecules 2018, 19, 2580–2594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiss, A.C.G.; Kelly, H.G.; Faria, M.; Besford, Q.A.; Wheatley, A.K.; Ang, C.S.; Crampin, E.J.; Caruso, F.; Kent, S.J. Link between low-fouling and stealth: a whole blood biomolecular corona and cellular association analysis on nanoengineered particles. ACS Nano 2019, 13, 4980–4991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiss, A.C.G.; Krüger, K.; Besford, Q.A.; Schlenk, M.; Kempe, K.; Förster, S.; Caruso, F. In situ characterization of protein corona formation on silica microparticles using confocal laser scanning microscopy combined with microfluidics. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2019, 11, 2459–2469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, A.; Wu, Z.; Luo, X.; Li, S. Protein adsorption and macrophage uptake of zwitterionic sulfobetaine containing micelles. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 2018, 167, 252–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merz, V.; Lenhart, J.; Vonhausen, Y.; Ortiz-Soto, M.E.; Seibel, J.; Krueger, A. Zwitterion-functionalized detonation nanodiamond with superior protein repulsion and colloidal stability in physiological media. Small 2019, 15, 1901551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Q.; Zhang, S.; Yang, Q.; Zhang, T.; Wei, X.Q.; Jiang, L.; Zhang, C.L.; Chen, Q.M.; Zhang, Z.R.; Lin, Y.F. Preformed albumin corona, a protective coating for nanoparticles based drug delivery system. Biomaterials 2013, 34, 8521–8530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Oliveira, F.A.; Albuquerque, L.J.C.; Castro, C.E.; Riske, K.A.; Bellettini, I.C.; Giacomelli, F.C. Reduced cytotoxicity of nanomaterials driven by nano-bio interactions: Case study of single protein coronas enveloping polymersomes. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 2022, 213, 112387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, V.H.; Meghani, N.M.; Amin, H.H.; Tran, T.T.D.; Tran, P.H.L.; Park, C.; Lee, B.J. Modulation of serum albumin protein corona for exploring cellular behaviors of fattigation-platform nanoparticles. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 2018, 170, 179–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gu, Z.; Zuo, H.; Li, L.; Wu, A.; Xu, Z.P. Pre-coating layered double hydroxide nanoparticles with albumin to improve colloidal stability and cellular uptake. J. Mater. Chem. B 2015, 3, 3331–3339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, H.; Liu, T.; Xu, Y.; Su, G.; Liu, T.; Yu, Y.; Xu, B. Protein corona precoating on redox-responsive chitosan-based nano-carriers for improving the therapeutic effect of nucleic acid drugs. Carbohydr. Polym. 2021, 265, 118071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, Z.; Yuan, C.; Xia, Q.; Qu, Y.; Yang, H.; Du, Q.; Xu, B. Pre-coating cRGD-modified bovine serum albumin enhanced the anti-tumor angiogenesis of siVEGF-loaded chitosan-based nanoparticles by manipulating the protein corona composition. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 267, 131546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez-Cazares, G.; Eniola-Adefeso, O. Dual coating of chitosan and albumin negates the protein corona-induced reduced vascular adhesion of targeted PLGA microparticles in human blood. Pharmaceutics 2022, 14, 1018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Ju, Y.; Zhou, J.; Faria, M.; Ang, C.S.; Mitchell, A.J.; Zhong, Q.Z.; Zheng, T.; Kent, S.J.; Caruso, F. Protein precoating modulates biomolecular coronas and nanocapsule–immune cell interactions in human blood. J. Mater. Chem. B 2022, 10, 7607–7621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graván, P.; Peña-Martín, J.; de Andrés, J.L.; Pedrosa, M.; Villegas-Montoya, M.; Galisteo-González, F.; Marchal, J.A.; Sánchez-Moreno, P. Exploring the impact of nanoparticle stealth coatings in cancer models: from PEGylation to cell membrane-coating nanotechnology. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2024, 16, 2058–2074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirshafiee, V.; Kim, R.; Park, S.; Mahmoudi, M.; Kraft, M.L. Impact of protein pre-coating on the protein corona composition and nanoparticle cellular uptake. Biomaterials 2016, 75, 295–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jasinski, J.; Wilde, M.V.; Voelkl, M.; Jérôme, V.; Fröhlich, T.; Freitag, R.; Scheibel, T. Tailor-made protein corona formation on polystyrene microparticles and its effect on epithelial cell uptake. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2022, 14, 47277–47287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, Z.; Fang, S.; Li, Y.; Huang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, H.; Zhang, J.; Wang, H.X.; Xiong, H.; Zou, Q.; et al. Quantitative analysis of protein corona on precoated protein nanoparticles and determined nanoparticles with ultralow protein corona and efficient targeting in vivo. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2021, 13, 56812–56824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tonigold, M.; Simon, J.; Estupiñán, D.; Kokkinopoulou, M.; Reinholz, J.; Kintzel, U.; Kaltbeitzel, A.; Renz, P.; Domogalla, M.P.; Steinbrink, K.; et al. Pre-adsorption of antibodies enables targeting of nanocarriers despite a biomolecular corona. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2018, 13, 862–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Capolla, S.; Colombo, F.; De Maso, L.; Mauro, P.; Bertoncin, P.; Kähne, T.; Engler, A.; Núñez, L.; Spretz, R.; Larsen, G.; et al. Surface antibody changes protein corona both in human and mouse serum but not final opsonization and elimination of targeted polymeric nanoparticles. J. Nanobiotechnol. 2023, 21, 376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, J.H.; Jackman, J.A.; Ferhan, A.R.; Belling, J.N.; Mokrzecka, N.; Weiss, P.S.; Cho, N.J. Cloaking silica nanoparticles with functional protein coatings for reduced complement activation and cellular uptake. ACS Nano 2020, 14, 11950–11961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, Y.-Q.; Qu, H.; Sfyroera, G.; Tzekou, A.; Kay, B.K.; Nilsson, B.; Nilsson Ekdahl, K.; Ricklin, D.; Lambris, J.D. Protection of nonself surfaces from complement attack by factor H-binding peptides: implications for therapeutic medicine. J. Immunol. 2011, 186, 4269–4277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belling, J.N.; Jackman, J.A.; Yorulmaz Avsar, S.; Park, J.H.; Wang, Y.; Potroz, M.G.; Ferhan, A.R.; Weiss, P.S.; Cho, N.J. Stealth immune properties of graphene oxide enabled by surface-bound complement factor H. ACS Nano 2016, 10, 10161–10172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, J.Y.; Choi, E.; Jana, B.; Go, E.M.; Jin, E.; Jin, S.; Lee, J.; Bae, J.H.; Yang, G.; Kwak, S.K.; et al. Protein-precoated surface of metal-organic framework nanoparticles for targeted delivery. Small 2023, 19, 2300218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, J.Y.; Seu, M.S.; Barui, A.K.; Ok, H.W.; Kim, D.; Choi, E.; Seong, J.; Lah, M.S.; Ryu, J.H. A multifunctional protein pre-coated metal–organic framework for targeted delivery with deep tissue penetration. Nanoscale 2024, 16, 14748–14756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caracciolo, G.; Cardarelli, F.; Pozzi, D.; Salomone, F.; Maccari, G.; Bardi, G.; Capriotti, A.L.; Cavaliere, C.; Papi, M.; Laganà, A. Selective targeting capability acquired with a protein corona adsorbed on the surface of 1, 2-dioleoyl-3-trimethylammonium propane/DNA nanoparticles. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2013, 5, 13171–13179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prozeller, D.; Pereira, J.; Simon, J.; Mailänder, V.; Morsbach, S.; Landfester, K. Prevention of dominant IgG Adsorption on nanocarriers in IgG-enriched blood plasma by clusterin precoating. Adv. Sci. 2019, 6, 1802199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, L.K.; Simon, J.; Schöttler, S.; Landfester, K.; Mailänder, V.; Mohr, K. Pre-coating with protein fractions inhibits nano-carrier aggregation in human blood plasma. RSC Adv. 2016, 6, 96495–96509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, J.; Müller, L.K.; Kokkinopoulou, M.; Lieberwirth, I.; Morsbach, S.; Landfester, K.; Mailänder, V. Exploiting the biomolecular corona: pre-coating of nanoparticles enables controlled cellular interactions. Nanoscale 2018, 10, 10731–10739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Treuel, L.; Brandholt, S.; Maffre, P.; Wiegele, S.; Shang, L.; Nienhaus, G.U. Impact of protein modification on the protein corona on nanoparticles and nanoparticle–cell interactions. ACS Nano 2014, 8, 503–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, W.; Zhong, Z.; Huang, Z.; Fu, F.; Wang, W.; Wu, L.; Huang, Y.; Wu, C.; Pan, X. Two different protein corona formation modes on Soluplus® nanomicelles. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 2022, 218, 112744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schöttler, S.; Klein, K.; Landfester, K.; Mailänder, V. Protein source and choice of anticoagulant decisively affect nanoparticle protein corona and cellular uptake. Nanoscale 2016, 8, 5526–5536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirshafiee, V.; Kim, R.; Mahmoudi, M.; Kraft, M.L. The importance of selecting a proper biological milieu for protein corona analysis in vitro: Human plasma versus human serum. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2016, 75, 188–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, Q.; Guo, J.; Yan, Y.; Ang, C.S.; Bertleff-Zieschang, N.; Caruso, F. Cell-conditioned protein coronas on engineered particles influence immune responses. Biomacromolecules 2017, 18, 431–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pozzi, D.; Caracciolo, G.; Digiacomo, L.; Colapicchioni, V.; Palchetti, S.; Capriotti, A.L.; Cavaliere, C.; Chiozzi, R.Z.; Puglisi, A.; Laganà, A. The biomolecular corona of nanoparticles in circulating biological media. Nanoscale 2015, 7, 13958–13966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Wu, T.; Yu, W.; Ruan, S.; He, Q.; Gao, H. Ligand size and conformation affect the behavior of nanoparticles coated with in vitro and in vivo protein corona. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2018, 10, 9094–9103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, J.; Kuhn, G.; Fichter, M.; Gehring, S.; Landfester, K.; Mailänder, V. Unraveling the in vivo protein corona. Cells 2021, 10, 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvati, A.; Pitek, A.S.; Monopoli, M.P.; Prapainop, K.; Bombelli, F.B.; Hristov, D.R.; Kelly, P.M.; Åberg, C.; Mahon, E.; Dawson, K.A. Transferrin-functionalized nanoparticles lose their targeting capabilities when a biomolecule corona adsorbs on the surface. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2013, 8, 137–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, W.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, H.; Liu, Y.; Xie, R.; He, X.; Zhou, Y.; Liang, L.; Gao, H. The protein corona hampers the transcytosis of transferrin-modified nanoparticles through blood–brain barrier and attenuates their targeting ability to brain tumor. Biomaterials 2021, 274, 120888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dai, Q.; Yan, Y.; Guo, J.; Björnmalm, M.; Cui, J.; Sun, H.; Caruso, F. Targeting ability of affibody-functionalized particles is enhanced by albumin but inhibited by serum coronas. ACS Macro Lett. 2015, 4, 1259–1263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ju, Y.; Dai, Q.; Cui, J.; Dai, Y.; Suma, T.; Richardson, J.J.; Caruso, F. Improving targeting of metal–phenolic capsules by the presence of protein coronas. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2016, 8, 22914–22922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carney, C.P.; Pandey, N.; Kapur, A.; Saadi, H.; Ong, H.L.; Chen, C.; Winkles, J.A.; Woodworth, G.F.; Kim, A.J. Impact of targeting moiety type and protein corona formation on the uptake of Fn14-targeted nanoparticles by cancer cells. ACS Nano 2023, 17, 19667–19684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lesniak, A.; Fenaroli, F.; Monopoli, M.P.; Åberg, C.; Dawson, K.A.; Salvati, A. Effects of the presence or absence of a protein corona on silica nanoparticle uptake and impact on cells. ACS Nano 2012, 6, 5845–5857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Castro, C.E.; Panico, K.; Stangherlin, L.M.; Albuquerque, L.J.C.; Ribeiro, C.A.S.; da Silva, M.C.C.; Jäger, E.; Giacomelli, F.C. Evidence of protein coronas around soft nanoparticles regardless of the chemical nature of the outer surface: structural features and biological consequences. J. Mater. Chem. B 2021, 9, 2073–2083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caracciolo, G.; Palchetti, S.; Colapicchioni, V.; Digiacomo, L.; Pozzi, D.; Capriotti, A.L.; La Barbera, G.; Laganà, A. Stealth effect of biomolecular corona on nanoparticle uptake by immune cells. Langmuir 2015, 31, 10764–10773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Y.; Gause, K.T.; Kamphuis, M.M.J.; Ang, C.-S.; O’Brien-Simpson, N.M.; Lenzo, J.C.; Reynolds, E.C.; Nice, E.C.; Caruso, F. Differential roles of the protein corona in the cellular uptake of nanoporous polymer particles by monocyte and macrophage cell lines. ACS Nano 2013, 7, 10960–10970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Digiacomo, L.; Cardarelli, F.; Pozzi, D.; Palchetti, S.; Digman, M.A.; Gratton, E.; Capriotti, A.L.; Mahmoudi, M.; Caracciolo, G. An apolipoprotein-enriched biomolecular corona switches the cellular uptake mechanism and trafficking pathway of lipid nanoparticles. Nanoscale 2017, 9, 17254–17262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, R.; Ren, J.; Ji, Y.; Wang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Chen, Z.; Sabet, Z.F.; Wu, X.; Lynch, I.; Chen, C. Corona of thorns: the surface chemistry-mediated protein corona perturbs the recognition and immune response of macrophages. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2020, 12, 1997–2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francia, V.; Yang, K.; Deville, S.; Reker-Smit, C.; Nelissen, I.; Salvati, A. Corona composition can affect the mechanisms cells use to internalize nanoparticles. ACS Nano 2019, 13, 11107–11121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lara, S.; Alnasser, F.; Polo, E.; Garry, D.; Lo Giudice, M.C.; Hristov, D.R.; Rocks, L.; Salvati, A.; Yan, Y.; Dawson, K.A. Identification of receptor binding to the biomolecular corona of nanoparticles. ACS Nano 2017, 11, 1884–1893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fleischer, C.C.; Payne, C.K. Secondary structure of corona proteins determines the cell surface receptors used by nanoparticles. J. Phys. Chem. B 2014, 118, 14017–14026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aoyama, M.; Hata, K.; Higashisaka, K.; Nagano, K.; Yoshioka, Y.; Tsutsumi, Y. Clusterin in the protein corona plays a key role in the stealth effect of nanoparticles against phagocytes. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2016, 480, 690–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavano, R.; Gabrielli, L.; Lubian, E.; Fedeli, C.; Visentin, S.; De Laureto, P.; Arrigoni, G.; Geffner-Smith, A.; Chen, F.; Simberg, D.; et al. C1q-mediated complement activation and C3 opsonization trigger recognition of stealth poly(2-methyl-2-oxazoline)-coated silica nanoparticles by human phagocytes. ACS Nano 2018, 12, 5834–5847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vu, V.P.; Gifford, G.B.; Chen, F.; Benasutti, H.; Wang, G.; Groman, E.V.; Scheinman, R.; Saba, L.; Moghimi, S.M.; Simberg, D. Immunoglobulin deposition on biomolecule corona determines complement opsonization efficiency of preclinical and clinical nanoparticles. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2019, 14, 260–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ban, Z.; Yuan, P.; Yu, F.; Peng, T.; Zhou, Q.; Hu, X. Machine learning predicts the functional composition of the protein corona and the cellular recognition of nanoparticles. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2020, 117, 10492–10499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, X.; Yang, C.; Su, Y.; Liu, C.; Qiu, H.; Yu, Y.; Su, G.; Zhang, Q.; Wei, L.; Cui, F.; et al. Machine learning enables comprehensive prediction of the relative protein abundance of multiple proteins on the protein corona. Research 2024, 7, 0487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rouse, I.; Power, D.; Subbotina, J.; Lobaskin, V. NP corona predict: A computational pipeline for the prediction of the nanoparticle–biomolecule corona. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2024, 64, 7525–7543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Type of particles | Variable parameter(s) |

Incubation medium |

Main conclusions | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nonporous silica particles, 50 and 500 nm; mesoporous silica particles, 500 nm | Size, porosity | FBS | The amount of adsorbed protein directly depends on the available surface area of particles. The protein profile is independent of surface area and porosity. | [12] |

| Silica particles with amidine surface modification, 30–1000 nm | Size | BSA and myoglobin solutions | Conformational changes of myoglobin and BSA upon adsorption are size-dependent. | [38] |

| Polystyrene particles, 50 and 100 nm; bare, carboxyl- and amine-modified | Size, surface chemistry | Human plasma | Size and surface chemistry significantly affect the composition of the protein corona. | [21] |

| Polystyrene microspheres (PS MSs), 1.33 and 4.46 μm, original and with etched surface | Size, surface morphology | Human plasma, BSA/fibrinogen solution | Protein adsorption is lower on etched PS MSs; the lowest adsorption is on PS MSs with the maximum number and minimum area of protuberances on the surface. This effect and total adsorption depend on size. MSs after etching (which changes the surface morphology) adsorb low-molecular-weight proteins; control MSs, a wider range of proteins. | [22] |

| Polystyrene particles, 100–500 nm | Size | HEWL solution | The particles form a protein corona of HEWL, mainly driven by hydrophobic interactions. 100-, 400-, and 500-nm particles promote HEWL to form amyloid fibrils. | [39] |

| Dense and mesoporous silica particles, 70–900 nm | Size, porosity | FBS | Both dense and porous particles with smaller size adsorb more protein; small dense particles adsorb proteins with lower Mw; all porous particles adsorb smaller proteins. | [34] |

| Elastin-like polypeptide (ELP)–based particles, 200 and 500 nm | Size, surface chemistry | Platelet-poor human plasma | All ELP constructs adsorb large amount of albumin, immunoglobulin G and activated complement factor 3; variations in the composition between different NPs are observed for plasminogen, fibronectin, activated fibrinogen, antithrombin and alpha2 macroglobulin. | [35] |

| LMW chitosan oligosaccharide (COS) NPs and HMW chitosan (CS) NPs, 130&150 and 95&110 nm, respectively | Size, composition | BSA and HSA solutions | CS NPs weakly interact with proteins because of the high structural rigidity of the polymer. The smaller CS NPs exhibit greater BSA binding. | [31] |

| Pyrolytic and colloidal silica particles, 20–120 and 50 nm, respectively | Size, surface chemistry | BSA solution | The difference in protein coverage appears to be related to differences in the distribution of surface silanols more than to differences in ζ-potential. | [56] |

| PS, PS-COOH, and PS-NH2 particles, 50 nm and 1 μm | Size, surface chemistry | Human saliva | Surface chemistry and size of the particles affect the adsorption of saliva proteins. Formation of the protein corona causes changes in the surface charge, aggregation and, hence, in vitro cytotoxicity. | [58] |

| PS particles, 50, 100, 200, and 500 nm and 1 μm; PS particles with the –COOH and –NH2 groups, 100 nm | Size, surface chemistry | Simulated salivary fluid, simulated gastric fluid, simulated intestinal fluid | The protein corona formed after in vitro digestion alters the macrophage uptake of uncharged 50- and 100-nm PS particles, but not charged 100-nm or larger particles. The presence of digestion proteins changes the adsorption of serum proteins from cell culture media. | [57] |

| Silica NPs, 8, 33, and 78 nm | Size | Yeast protein extract | Larger NPs adsorbed more protein per surface unit; most of the protein adsorbed on NPs with different size were identical. | [36] |

| PEGylated gold NPs, 20–150 nm | Size | HDL solution, human serum | Larger NPs exhibit a larger surface coverage with HDLs. This process is regulated by nonspecific interactions rather than adsorption of apolipoprotein A-I. | [37] |

| Solid lipid nanoparticles (SLNs), 120–480 nm | Size | BSA solution | BSA adsorption increases with the increasing size of the particles. | [25] |

| PEGylated plasmonic gold NPs (rods and stars), 40 and 70 nm | Size, shape | In vivo in CD-1 mice | Gold nanostars adsorb more protein than nanorods due to their larger surface area. The composition of the protein corona varies between NPs with different sizes and shapes. | [9] |

| Polystyrene NPs, 26, 80, and 200 nm | Size | Mouse serum | Protein corona formation is size-dependent. | [32] |

| Gold NPs modified with PEG, 21–109 nm | Size | FBS | Protein adsorption is greater on larger gold NPs. | [33] |

| Gold NPs (spheres, rods, stars, and cages) functionalized with R-PEG-SH (R= OCH3, COOH, or NH2), ∼50 nm | Shape, surface chemistry | Human serum | Cage-shaped NPs adsorb less protein and differ in the protein corona composition. | [10] |

| Mesoporous silica particles, spherical, faceted, and rod-shaped | Shape | Bovine serum | Considerable differences in the protein composition, surface coverage, and particle agglomeration of the protein corona-particle complex indicate specific protein adsorption profiles highly dependent on the number of exposed facets and aspect ratio. | [40] |

| Mesoporous silica particles: spherical, 270 nm; rod-shaped, 290×1100 nm | Shape | Serum, plasma | Rod-shaped particles adsorb more protein from serum and plasma. | [41] |

| Diethylaminoethyl-dextran cellulose microspheres, 100 μm; pore size, 165–282 nm | Pore size | BSA and γ-globulin solutions | The increasing-then-decreasing trends in the adsorption equilibria and uptake kinetics are observed as the pore size increases. A critical pore size at which the adsorption capacity and uptake are significantly enhanced has been determined. | [42] |

| Poly(methacrylic acid) (PMA) capsules and particles functionalized with mAbs | Structure | Human serum | The capsules and particles differ in the protein corona composition. The protein corona has little effect on the targeting ability of the mAb-functionalized capsules and particles. | [43] |

| Silica nanocapsules, 150–180 nm, with stiffnesses (Young moduli) of 704 kPa, 25 MPa, 459 MPa, and 9.7 GPa | Stiffness | FBS | The protein corona of the stiffest nanocapsules contains the largest amount of complement protein C3 and immunoglobulin proteins, which facilitates their macrophage uptake. | [50] |

| Hydrogel NPs with a lipid bilayer shell and unmodified or PEGylated surface, 100–150 nm; elasticity, 45 kPa–760 MPa | Stiffness | Mouse plasma | The protein corona composition varies nonmonotonically depending on the NP elasticity; the relative abundance of Apo-I is correlated with the blood clearance lifetime of the NPs. | [51] |

| Polymeric core/multishell, solid cationic and anionic NPs and polymeric soft nanogels (NGs), 75–175 nm | Surface chemistry | Human plasma | Solid anionic and cationic particles adsorb more protein than other particles; NPs with a protein corona more weakly interact with cells; NGs with a protein corona induce enhanced cytokine release | [20] |

| Core/shell and shell-only multilayered polyelectrolyte particles, 2 μm | Structure | Human serum, plasma | Differences in particle structure affect both the quantity of adsorbed proteins and the relative abundance of individual protein groups (apolipoproteins, complement proteins, and immunoglobulins). | [44] |

| PLGA-NPs, 152 nm; PLGA/cholesterol NPs, 237 nm; cholesterol NPs, 257 nm | Composition | Human plasma | Different protein corona compositions on particles with different matrix compositions in the presence or absence of targeting ligand has been shown. | [15] |

| MAA and PMMA polymeric beads | Composition, incubation medium | Serum, plasma | The two materials differ with respect to protein adsorption, which is associated with differences in complement activation. | [45] |

| Sulphated alginate, high G alginate, and poly-L-lysine-coated alginate microspheres, 565, 579, and 538 μm, respectively | Composition | Lepuridin-anticoagulated plasma | Differences in adsorption of complement and coagulation proteins can explain differences in the inflammatory and fibrotic responses to three types of alginate microspheres. | [46] |

| Lipid nanodiscoids, 47–63 nm | Composition | Mouse serum | The phospholipid composition affects the protein corona composition, which determines the particle stability, circulation, and biodistribution. | [26] |

| Elastomer (star-poly(D,L-lactide-co-e-caprolactone)) E2 and E5 microspheres, 184 and 370 μm | Composition | FBS, human plasma | Polymer chain flexibility affects protein adsorption in competitive adsorption environments. | [49] |

| Lipid NPs, 67–110 nm | Composition | Nude mice serum | Differences in lipid constituents altered composition of protein corona; NPs with apolipoprotein-rich corona showed higher delivery efficiency than NPs with vitronectin-rich corona. | [27] |

| PLGA and PCL particles, 416 and 559 nm | Composition | HSA, human serum | Serum proteins have a higher affinity to more hydrophobic (PCL) particles; the protein corona composition is material-specific. | [16] |

| Poly(methyl methacrylate-co-styrene) particles, ∼550 nm | Composition | BSA, IgG, and fibronectin solutions | Protein adsorption is enhanced on particles with a higher amount of styrene due to a higher hydrophobicity. | [19] |

| Albumin, cationic albumin, and ovalbumin cross-linked NPs, 165–206 nm | Composition | FBS | Protein-based NPs with various hydrophobicities and charges differ in the protein corona pattern; the protein corona affects in vitro macrophage uptake of BSA and cationic BSA NPs but not ovalbumin NPs. | [24] |

| Polystyrene NPs with –COOH, –NH2, –SO3, and –PO3 surface groups, ~100 nm | Surface chemistry | Human serum | High enrichment of apolipoproteins on NPs and preferential binding of apolipoproteins on NH2- and SO3- functionalized NPs has been found. | [23] |

| Poly(styrene) surfaces modified with –NH2, –COOH, and –PO3H2 | Surface chemistry | FBS | Protein adsorption varied between surfaces with different surface groups; this was related with differences in their binding by macrophages and inflammatory responses to them. | [52] |

| PLA and PLGA NPs, 188–224 nm | Surface chemistry, hydrophobicity, matrix polymer Mw, incubation medium | Human serum, plasma | The PLA matrix polymer Mw affects only the types of the bound proteins; adsorption of specific proteins depends on hydrophobicity; surface end group identity influences both the total amount and the profile of the adsorbed proteins. | [55] |

| Glycosylated polyhydroxy polymer-modified nanovesicles (CP-LVs), ~100 nm | Surface chemistry | Plasma, liver tissue interstitial fluid | CP-LVs with the highest amino-to-hydroxyl ratio are characterized by a decreased immunoglobulin adsorption and prolonged blood circulation; adsorption of tumor-specific proteins leads to effective cellular internalization. | [53] |

| Polyelectrolyte-doped block copolymer-stabilized NPs, 40–180 nm | Surface chemistry | BSA solution | NPs with an anionic (PAA) surface modification tend to adsorb less protein and are taken up only by macrophage-like cells, whereas cationic (DMAEMA) NPs are taken up by different types of cells. | [54] |

| Type of particles | Modification | Incubation medium |

Main conclusions | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ovalbumin NCs, 250–300 nm | PEG | Human plasma | Conformation of PEG affects the adsorption of specific proteins (dysopsonins) on NCs and their uptake by phagocytic cells. | [71] |

| Polystyrene NPs, 90–100 nm | Lutensol AT50 (PEG-based surfactant), SDS | HSA solution | The NPs coated with Lutensol adsorb more protein than those coated with SDS; however, the loss of conformation is less pronounced in PEGylated (Lutensol-modified) NPs. | [69] |

| Phosphonic acid terminated poly(ethylene glycol)-conjugated layered double hydroxide (PEG-LDH) NPs, 100–170 nm | PEG | BSA solution | PEGylation of LDH particles enhances their stability, reduces BSA adsorption, and enhanced cellular uptake. | [60] |

| PEGylated gold NPs (GNPs), 125–214 nm | PEG (350, 550, 1000 Da) | Human plasma | GNPs modified with PEG 550 adsorb more albumin and transferrin, which correlates with higher uptake by, and cytotoxicity for, HepG2 cells and a higher antitumor effect in mice. | [74] |

| Mesoporous silica particles (MSNs), 980 nm | PEG (2000, 5000, 10000 Da) | BSA solution | The depth of BSA penetration into MSNs in higher than that of MSNs-PEG; the maximum penetration depth decreases with increasing PEG chain length. | [61] |

| Mesoporous silica (MS), MS-PEG, and PEG particles, 100, 450, and 800 nm | PEG | Human plasma | The rate of immune cell association of MS-PEG particles with protein coronas formed from plasmas of individual donors widely varies depending on the donor; the cell association of all PEG particles is minor irrespective of the protein corona source. | [76] |

| Mesoporous silica NPs (MSNs), 210–250 nm | PEG | 10% FCS in PBS | Method of PEGylation affects the NP pore size and the amount of adsorbed proteins. | [63] |

| Gold NPs (AuNPs), 18–78 nm | PEG (5000, 10000, 30000 Da) | BSA, GB3 (WT and K19C), and H1.5 peptide (with and without cysteine) solutions | The amount of adsorbed peptides/proteins decreases with decreasing PEG size; small molecules (glutathione, H1.5 peptide, GB3) can penetrate PEG layers: the presence of thiol groups enhances the adsorption on PEGylated AuNPs. | [73] |

| Strontium sulphite NPs (SSNs), 670–2100 nm | PEG | 10% mouse plasma | PEGylation of SSNs leads to reduction of protein adsorption from serum, reduction of cytotoxicity, and efficient tumor delivery. | [64] |

| PLGA and PLGA-PEG NPs, 100 and 200 nm | PEG | FBS | PEGylation significantly decreases the amount of bound proteins. | [59] |

| SiO2, SiO2-sulfobetaine silane (SBS), and SiO2-PEG2000 NPs, ~100 nm | Zwitterion, PEG | BSA and lysozyme solutions | Functionalization of SiO2 NPs with PEG and SBS prevents BSA adsorption but not lysozyme adsorption, although the latter is reduced, with no particle aggregation. | [62] |

| Polystyrene particles with –NH2, –PEG, or poly(ethyl ethylene phosphate) (PEEP) groups, 100–120 nm | PEG, PEEP | Human plasma | In addition to reducing protein adsorption, PEG and PEEP can affect the composition of the protein corona, and the presence of specific proteins is necessary to prevent nonspecific cellular uptake. | [72] |

| Alginate/chitosan/alginate (ACA) hydrogel microcapsules modified with chitosan-methoxy poly-(ethylene glycol) (CS-g-MPEG), 350 μm | MPEG | IgG solution | Adsorption of IgG is drastically reduced on microcapsules coated with CS-g-MPEG. The protein repulsion capacity depends on the degree of substitution and chain length of MPEG. | [70] |

| Hydroxyethyl starch NPs functionalized with PEG and modified with mannose | PEG, PEG–mannose | Human plasma | The PEG and PEG–mannose modifications of HES NPs reduces the protein adsorption but do not affect the protein corona composition. HES–PEG-mannose NPs are efficiently bound by dendritic cells. | [65] |

| Hydroxyethyl starch NPs functionalized with PEG | PEG | Human serum | PEGylation of HES NPs reduces the protein adsorption from serum by 37%. | [66] |

| Gold NPs functionalized with fluorescent Herceptin and backfilled with methoxy-terminated PEG (mPEG) , 73–97 nm | PEG (1000, 2000, 5000, 10000 Da) | Human serum | NPs with attached PEG groups adsorb less proteins in the presence of serum but retained the targeting specificity. | [67] |

| Iron oxide nanoparticles (IONPs) coated with polyethylene glycol-allyl glycidyl ether copolymer functionalized with RGD peptide or transferrin, 22–31 nm | PEG-b-AGE | FBS, human plasma | Coating of the NPs, with PEG-b-AGE leads to a decrease in protein adsorption and nonspecific uptake by macrophages of NPs, irrespective of functionalization. | [68] |

| PEGylated liposomal drug (Onyvide), 60 nm | PEG | Human plasma | PEGylation of liposomes does not prevent the formation of the protein corona; adsorbed proteins from plasma enhance binding to PANC-1 cells. | [77] |

| Gold NPs modified with PEG, 21–109 nm | PEG | FBS | PEG modification reduces plasma protein adsorption. | [33] |

| Liposomes functionalized with PEG or hyperbranched polyglycerol, 60–90 nm | PEG, PG | Human plasma | Protein adsorption on unmodified and PEG- and PG-modified liposomes is relatively low; macrophage uptake of liposomes is not affected by the protein corona; modification with PEG reduces cellular uptake, whereas modification with PG enhances it. | [82] |

| Nanodiamonds (NDs), 30, 50, and 100 nm; SPIONs, 22 nm | PEG, PG | FBS, human plasma | PG modification more efficiently reduces the protein adsorption and macrophage uptake than PEG modification. | [81] |

| Polystyrene NPs modified with poly(phosphoester) surfactants, ∼110 nm | PPE | HSA, plasma | Noncovalent modification of PS NPs with poly(phosphoester) surfactants reduces the protein adsorption and macrophage uptake after incubation in plasma. | [83] |

| Poly(organosiloxane) NPs functionalized with PEG or poly(2-ethyl-2-oxazoline), 22–26 nm | PEG, PEtOx | Bovine serum | Modification of the NPs with either PEG or PEtOx reduces the protein adsorption; modification with PEtOx reduces the cellular uptake in both serum and serum-free medium. | [84] |

| Biotin- and cysteine-coated silica NPs, 120 nm | Zwitterion (amino acid) | 10, 50, 100% human plasma | Zwitterionic (cysteine) coating interferes with the protein corona formation and improves the NP targeting ability. | [88] |

| Silica NPs functionalized with lysine/arginine/glycine/cysteine/phenylalanine, ∼60 nm | Zwitterions (amino acids) | BSA, 10% FBS | Functionalization of NPs with cysteine, lysine, and arginine reduces protein adsorption, the effect of lysine being the strongest. | [89] |

| Gold NPs conjugated with zwitterionic peptides or PEG, 50–100 nm | Zwitterions (peptides) | Human serum | Protein adsorption is reduced up to 60% compared with bare NPs; the protein adsorption profile depends on the charge motif and sequence but not amino acid composition. | [90] |

| Silica NPs (SiO2-organosiloxane), ∼120 nm | Zwitterion | BSA and lysozyme solutions, 50% FBS | Zwitterated silica NPs display antifouling properties in both BSA and lysozyme solutions, as well as in FBS. | [91] |

| Bi-functionalized silica NPs (SiO2- organosiloxane/COOH), ∼140 nm | Zwitterion | BSA and lysozyme solutions, 50% FBS | SiO2-organosiloxane/COOH5/1 particles absorb less protein while retaining the capacity for effectively binding target biomolecules. | [92] |

| Sulfobetaine-coated silica NPs, 250 nm | Zwitterion | BSA solution, FBS | Zwitterion-modification of silica NPs results in a 90% decrease in protein adsorption rate and a reduced NP uptake by macrophages and fibroblasts. | [95] |

| Polystyrene/Fe3O4/silica NPs functionalized with amino/alkene/betaine, 230–440 nm | Zwitterion | BSA and lysozyme solutions , FBS | Betaine functionalization reduces the protein adsorption from single-protein solutions and serum, with amino and alkene groups remaining accessible for interaction with biomolecules. | [93] |

| PEI-coated core/shell Fe3O4@SiO2 NPs functionalized with 2-methacryloyloxyethyl phosphorylcholine (MPC), ∼125 nm | Zwitterion | BSA solution, FBS | The protein corona formation in in 50-MPC- and 75-MPC-functionalized silica NPs is reduced in BSA solution and FBS. | [99] |

| Silica NPs functionalized with zwitterion and amino/mercapto/carboxylic groups, ∼100 nm | Zwitterion | BSA solution | Double-functionalized NPs exhibited a low protein adsorption level, with biologically active groups shielded from interactions. | [94] |

| Nanodiamonds (NDs) functionalized with zwitterion and tetraethylene glycol (TEG), ∼100 nm | Zwitterion | FBS | Combined surface functionalization of NDs with TEG chains and zwitterionic head groups ensures colloidal stability and prevents protein adsorption. | [108] |

| Silica NPs functionalized with carboxybetaine, 40 nm | Zwitterion | BSA solution | Protein binding to functionalized NPs is significantly reduced (by up to 94%). | [97] |

| Hollow mesoporous Prussian blue NPs (HMPBs) functionalized with sulfobetaine and peptide E5, 130 nm | Zwitterion | BSA solution | HMPBs@PEI-ZW and HMPBs@PEI-ZW-E5 NPs adsorb noticeably less BSA than the original NPs. | [96] |

| Poly(DMAEMA-co-carboxybetaine methacrylate)-modified silica NPs (MCB), 137–220 nm | Zwitterionic copolymer | BSA and lysozyme solutions | Modification of silica NPs using carboxybetaine copolymer with different quaternization degrees modulates the adsorption of basic and acidic proteins. | [103] |

| Poly(ε-caprolactone)-b-poly(N,N-diethylaminoethyl methacrylate)/(N-(3- sulfopropyl-N-methacryloxyethy-N,N-diethylammonium betaine)) (PCL-PDEAPS) and poly(ε-caprolactone)-b-poly(ethylene glycol) (PCL-PEG) micelles, 77–109 and 51 nm, respectively |

Zwitterionic polymers, PEG | BSA, lysozyme, and fibrinogen solurions; plasma | PCL-PDEAPS micelles adsorb more negatively charged proteins (BSA, fibrinogen) than PCL-PEG micelles due to electrostatic interactions; PCL-PDEAMS micelle uptake by macrophages after protein adsorption is low. | [107] |

| Magnetic gold NPs functionalized with poly(carboxybetaine methacrylate) and poly 2-carboxy- N,N-dimethyl-N-(2′-(methacryloyloxy)ethyl)ethanaminium), 123 nm | Zwitterion | HSA solution, serum | Magnetic gold NPs with CBMA coating adsorb significantly less protein than control NPs coated with PEG, PAH, or PEI. | [98] |

| Gold NPs coated with thiol-functionalized polymethacryloyloxyethyl phosphorylcholine polymers (pMPC), 230 nm | Zwitterion | Human serum, BALF | pMPC-coated gold NPs exhibit reduced protein adsorption and increased uptake by A549 cells after exposure to serum. | [100] |

| Core/shell GelMA microcapsules; zwitterionic coated CBMA-GelMA, SBMA-GelMA, and MPC-GelMA microcapsules, ~600 μm | Zwitterionic polymers | FITC-BSA in PBS | Zwitterionic coating effectively block nonspecific protein adsorption. | [102] |

| Poly(glycidyl methacrylate) (PGMA) microspheres modified with [3-(methacryloylamino)propyl]dimethyl(3-sulfopropyl)ammonium hydroxide (MPDSAH), 2 μm | Zwitterionic polymers | BSA solution | The amount of adsorbed BSA reduced up to half of that on the unmodified PGMA microspheres. | [101] |

| Silica particles with poly(2-methacryloyloxyethyl phosphorylcholine) coating | Zwitterionic polymers | HSA solution | Coating with zwitterion prevents the adsorption of tightly bound proteins, but a “soft” protein corona forms on the particles. | [106] |

| Mesoporous silica particles, poly(2-methacryloyloxyethylphosphorylcholine) (PMPC)-coated silica hybrid particles, PMPC replica particles, 164, 161, and 179 nm, respectively | Zwitterionic polymers | Human serum, human blood | Mesoporous silica particles adsorb more proteins of a wider range of molecular weights than PMPC-coated and PMPC replica particles. | [104] |

| Mesoporous silica particles and poly(2-methacryloyloxyethyl phosphorylcholine) (PMPC) particles, with or without coating with HSA, IgG, and C1q, ∼1 µm | Zwitterionic polymers, proteins | Human plasma, whole blood, washed blood | PMPC particles exhibit reduced adsorption of serum proteins and association with cells. The enrichment of the corona with some proteins facilitates association with specific cell types. | [105] |

| Poly(acrylic acid)-block-polystyrene (PAA22-b-PS144) polymersomes, 60 nm | BSA, IgG, lysozyme | – | The formation of protein coronas from all model proteins used reduces the cytotoxicity of the polymersomes | [110] |

| Poly-3-hydroxybutyrate-co-3-hydroxyhexanoate (PHBHHx) NPs, ~200 nm | BSA | Rat serum | Preformed albumin corona inhibits the plasma proteins adsorption, reduces the complement activation, prolongs the blood circulation time, and reduces the toxicity of the PHBHHx NPs. | [109] |

| PS particles with –COOH and –NH2 groups or without functionalization, 58–69 nm | Human plasma fractions (IgG, HSA, and low-abundant protein) | Human plasma | Pre-incubation with IgG-, HSA-, and low-abundant-protein-enriched plasma fractions alters cellular uptake and inhibits aggregation of PS and PS-NH2 particles in human plasma. | [130] |

| Supramolecular template NPs, metal–phenolic network (MPN)-coated template (core/shell) NPs, and MPN nanocapsules, ~100 nm | BSA, FBS, bovine serum | Human blood | Precoating using FBS effectively reduces the amount of adsorbed proteins and alters the composition of the protein corona, which reduces NP association with leukocytes. | [116] |

| PS particles with –COOH and –NH2 groups, 150–230 nm; hydroxyethyl starch (HES) NPs, 450 nm | Antibodies | Human serum or plasma | NPs with pre-adsorbed antibodies retain the targeting ability after the formation of the biomolecular corona. | [121] |

| PS particles with –COOH and –NH2 groups, 130–150 nm | IgG-depleted plasma | Cell culture medium containing human plasma | Precoating of NPs with Ig-depleted plasma reduces their cellular uptake; the preformed protein corona remains stable after the reintroducing to plasma. | [131] |

| Starch-coated poly(methyl methacrylate-co-acrylic acid) nanoparticles, 85 nm | Casein, soybean protein isolate, myoglobin, zein, gelatin | 30% FBS | NPs precoated with casein exhibit antifouling properties and excellent targeting in vitro and in vivo. | [120] |

| PS particles, 0.2 and 3 μm | BSA, myoglobin, β-lactoglobulin, lysozyme, fibrinogen | 10% FCS in cell culture medium | Precoating of particles strongly affects the protein corona formation; primary proteins still can be detected after the second incubation. Precoating affects particle–cell interactions, but not the particle toxicity. | [119] |

| Carboxylic acid-functionalized silica NPs, ~100 nm | γ-globulin, HSA | 10 or 55% human plasma in PBS | Precoating of the NPs with γ-globulins, but not HSA, leads to enrichment of the protein corona with immunoglobulins and complement factors, but the opsonin-rich corona does not enhance NP uptake by macrophages. | [118] |

| Polylactic acid (PLA)-PEG-poly(ε-caprolactone) (PCL) NPs, 118 and 189 nm | Antibody | Mouse serum or human serum | Complement proteins are adsorbed on the NP surface. NPs bearing the targeting antibody activate the classical immune pathway; untargeted NPs, the alternative pathway. | [122] |

| Layered double hydroxide (LDH) NPs, ~100 nm | BSA | Cell culture medium | BSA precoating stabilizes LDH suspensions in cell culture medium and enhances the NP uptake by CHO cells. | [112] |

| Gelatin–oleic nanoparticles (GONs) | BSA | Cell culture medium containing FBS | Uptake of GONs precoated with BSA by HEK293 cells is enhanced, but their uptake by A549 cells is suppressed in a FBS-containing cell medium | [111] |

| Chitosan-based nanocarriers (TsR NPs) loaded with siVEGF, 500–1500 nm | BSA-cRGD | 10% FBS | Adsorption of BSA-cRGD on TsR NPs results in a reduced serum protein adsorption and improves tumor targeting and therapeutic efficiency. | [113] |

| siVEGF-loaded chitosan-based NPs (CsR/siVEGF NPs), 150–1000 nm | BSA-cRGD | 10% mouse serum, 10% FBS | Precoating of CsR/siVEGF NPs with BSA-cRGD enhances their stability in serum and tumor targeting efficiency, which is related to reduced protein adsorption from serum and changes in the protein corona composition. | [114] |

| Polystyrene NPs coated with PEG, BSA, chitosan, and cell membranes from a human breast cancer cell line, 110–150 nm | PEG, BSA, chitosan, cell membranes | 10% FBS | All the tested coatings reduce protein adsorption, the effects of the BSA and cell membrane coatings being the strongest. | [117] |

| PLGA and chitosan–PLGA microparticles, ∼1.6 μm | HSA | Human plasma | HSA coating changes the protein profile of the corona and enhances binding to endothelial cells. | [115] |

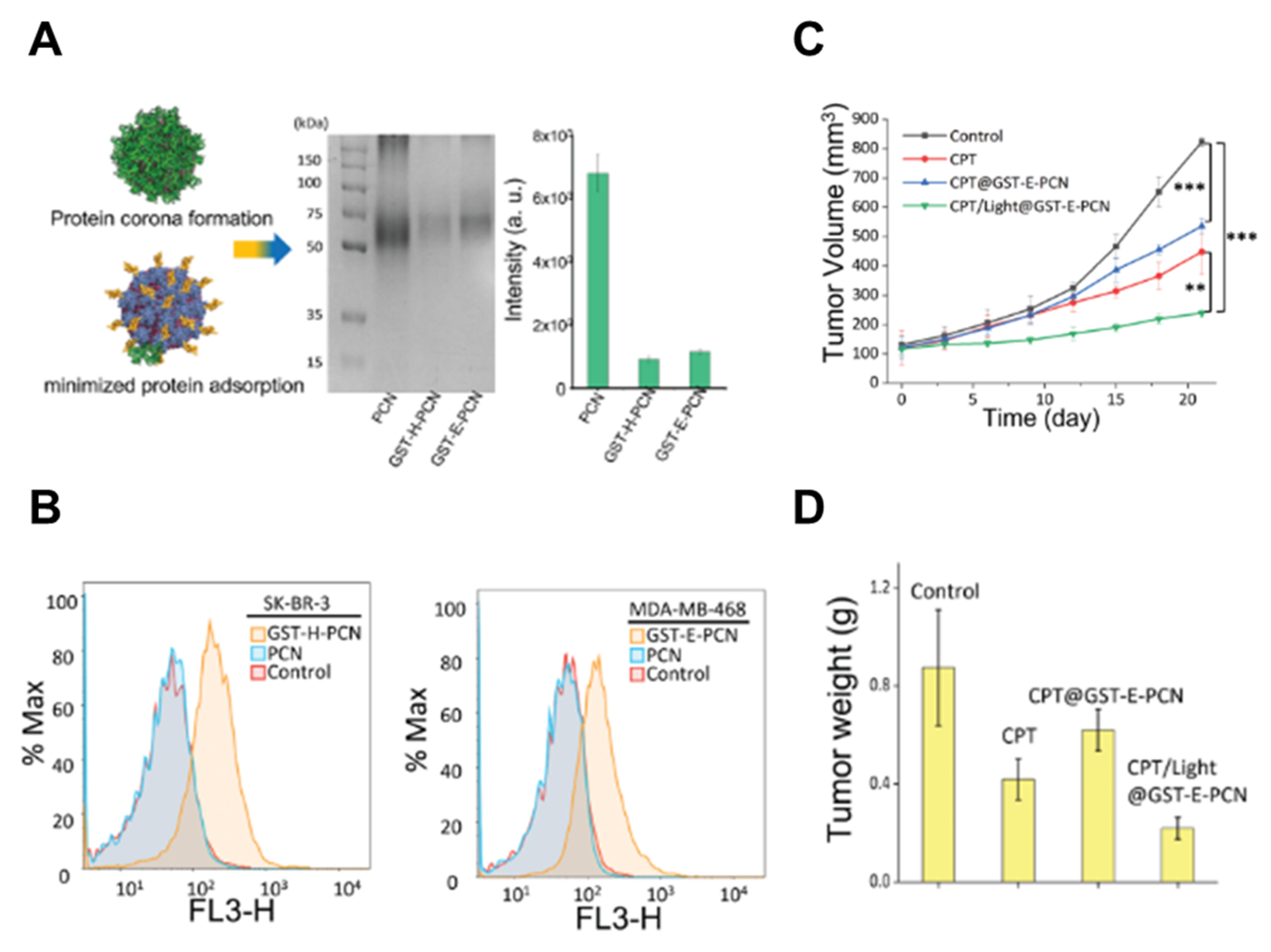

| Zr6-based metal–organic framework NPs (PCN-224), 180–260 nm | GST-Afb | 50% serum | Precoating of PCN-224 with a protein layer reduces the protein adsorption on NPs and improved cancer cell and tumor targeting. | [126] |

| Metal–organic frameworks particles (MOF-808) loaded with camptothecin, 90–120 nm | GST-Afb and collagenase | 50% serum | Formation of a protein layer consisting of GST-Afb and collagenase reduces protein adsorption from serum and provides efficient tissue penetration and tumor targeting. | [127] |

| DOTAP/DNA lipid particles, ∼220 nm | Human plasma | – | Spontaneous coating with vitronectin promotes the uptake by cancer cells overexpressing vitronectin the ανβ3 integrin receptor. | [128] |

| Silica NPs, 110 nm | BSA, HSA, IgG, complement factor H, fibrinogen | Human serum | Coating with BSA, HSA, and fibrinogen reduces the adsorption of complement proteins on the NP surface; coating with complement factor H inhibits complement activation by the NPs. | [123] |

| Polystyrene NPs, 50 nm; HES NPs, 110 nm | Clusterin (apolipoprotein J) | IgG-enriched human plasma | Precoating of both types of NPs with clusterin reduces IgG adsorption from IgG-enriched plasma and suppresses cellular uptake. | [129] |

| Polystyrene NPs (PS-COOH), 100 nm | Apolipoproteins ApoA4, ApoC3, and ApoH; prothrombin; antithrombin III | – | Coating with ApoA4 and ApoC3 reduces the NP uptake by hMSCs, whereas coating with ApoH enhances the uptake. Prothrombin and antithrombin III do not affect the cellular uptake significantly. | [23] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).