Submitted:

20 March 2025

Posted:

21 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Material and Method

2.1. Questionnaire and Measurement

2.2. Data Collection

2.3. Data Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Ethical statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Competing interests

References

- A, E.R.; P, D. Role of women and youth in food security and rural livelihood. Int. J. Agric. Ext. Soc. Dev. 2020, 3, 68–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allaire, G.; Vandecandelaere, E. Linking people, places and products: A guide for promoting quality linked to geographical origin and sustainable geographical indications, 2nd ed; FAO, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Bahl, S.; Milne, G.R.; Ross, S.M.; Mick, D.G.; Grier, S.A.; Chugani, S.K.; Chan, S.S.; Gould, S.J.; Cho, Y.-N.; Dorsey, J.D.; et al. Mindfulness: Its Transformative Potential for Consumer, Societal, and Environmental Well-Being. J. Public Policy Mark. 2016, 35, 198–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balundė, A.; Perlaviciute, G.; Steg, L. The Relationship Between People’s Environmental Considerations and Pro-environmental Behavior in Lithuania. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 2319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bamberg, S. How does environmental concern influence specific environmentally related behaviors? A new answer to an old question. J. Environ. Psychol. 2003, 23, 21–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barak, F.; Efitre, J.; Odong, R.; Melgar-Quiñonez, H. Women's agency in nutrition in the association between women's empowerment in agriculture and food security: A case study from Uganda. World Food Policy 2023, 9, 228–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bean, M.; Sharp, J.S. Profiling alternative food system supporters: The personal and social basis of local and organic food support. Renew. Agric. Food Syst. 2011, 26, 243–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beitzen-Heineke, E.F.; Balta-Ozkan, N.; Reefke, H. The prospects of zero-packaging grocery stores to improve the social and environmental impacts of the food supply chain. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 140, 1528–1541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bimbo, F.; Russo, C.; Di Fonzo, A.; Nardone, G. Consumers' environmental responsibility and their purchase of local food: evidence from a large-scale survey. Br. Food J. 2020, 123, 1853–1874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Born, B.; Purcell, M. Avoiding the Local Trap: Scale and Food Systems in Planning Research. J. Plan. Educ. Res. 2006, 26, 195–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouman, T.; Steg, L.; Perlaviciute, G. From values to climate action. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 2021, 42, 102–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowden, R.; Even-Zahav, E.; Kelly, C. Innovative Food Procurement Strategies of Women Living in Khayelitsha, Cape Town. Urban Forum 2018, 29, 315–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bytyçi, P.; Kokthi, E.; Hasalliu, R.; Fetoshi, O.; Salihu, L.; Mestani, M. Is the local origin of a food product a nexus to better taste or is just an information bias. Int. J. Gastron. Food Sci. 2024, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camanzi, L.; Kaliji, S.A.; Prosperi, P.; Collewet, L.; El Khechen, R.; Michailidis, A.C.; Charatsari, C.; Lioutas, E.D.; De Rosa, M.; Francescone, M. Value seeking, health-conscious or sustainability-concerned? Profiling fruit and vegetable consumers in Euro-Mediterranean countries. Br. Food J. 2024, 126, 303–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casas, R. Moving towards a Healthier Dietary Pattern Free of Ultra-Processed Foods. Nutrients 2021, 14, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chao, C.; Yu, T. How emotions and green altruism explain consumer purchase intention toward circular economy products: A multi-group analysis on willingness to be environmentally friendly. Bus. Strat. Environ. 2023, 33, 2803–2816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, P.-J.; Antonelli, M. Conceptual Models of Food Choice: Influential Factors Related to Foods, Individual Differences, and Society. Foods 2020, 9, 1898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiffoleau, Y.; Dourian, T. Sustainable Food Supply Chains: Is Shortening the Answer? A Literature Review for a Research and Innovation Agenda. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiffoleau, Y.; Dourian, T. Sustainable Food Supply Chains: Is Shortening the Answer? A Literature Review for a Research and Innovation Agenda. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conrad, Z.; Blackstone, N.T. Identifying the links between consumer food waste, nutrition, and environmental sustainability: a narrative review. Nutr. Rev. 2020, 79, 301–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dentoni, D. , Tonsor, G. T., Calantone, R. J., Peterson, H. C., Dentoni, D., Tonsor, G. T., Calantone, R. J., Peterson, H. C. (2009). The Direct and Indirect Effects of ‘Locally Grown’ on Consumers’ Attitudes towards Agri-Food Products. [CrossRef]

- Deselnicu, O. C. , Costanigro, M., Souza-Monteiro, D. M., McFadden, D. T. A Meta-Analysis of Geographical Indication Food Valuation Studies: What Drives the Premium for Origin-Based Labels? Journal of Agricultural and Resource Economics 2013, 38, 204–219. [Google Scholar]

- Dimitrova, R.; Musso, P.; Naudé, L.; Zahaj, S.; Solcova, I.P.; Stefenel, D.; Uka, F.; Jordanov, V.; Jordanov, E.; Tavel, P. National collective identity in transitional societies: Salience and relations to life satisfaction for youth in South Africa, Albania, Bulgaria, the Czech Republic, Kosovo and Romania. J. Psychol. Afr. 2017, 27, 150–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doernberg, A.; Piorr, A.; Zasada, I.; Wascher, D.; Schmutz, U. Sustainability assessment of short food supply chains (SFSC): developing and testing a rapid assessment tool in one African and three European city regions. Agric. Hum. Values 2022, 39, 885–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doss, C.R. Women and agricultural productivity: Reframing the Issues. Dev. Policy Rev. 2017, 36, 35–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Druen, P.B.; Zawadzki, S.J. Escaping the Climate Trap: Participation in a Climate-Specific Social Dilemma Simulation Boosts Climate-Protective Motivation and Actions. Sustainability 2021, 13, 9438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards-Jones, G. Does eating local food reduce the environmental impact of food production and enhance consumer health? Proc. Nutr. Soc. 2010, 69, 582–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisinger-Watzl, M.; Wittig, F.; Heuer, T.; Hoffmann, I. Customers Purchasing Organic Food - Do They Live Healthier? Results of the German National Nutrition Survey II. Eur. J. Nutr. Food Saf. 2015, 5, 59–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Endrizzi, I.; Cliceri, D.; Menghi, L.; Aprea, E.; Gasperi, F. Does the ‘Mountain Pasture Product’ Claim Affect Local Cheese Acceptability? Foods 2021, 10, 682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ericson, T.; Kjønstad, B.G.; Barstad, A. Mindfulness and sustainability. Ecol. Econ. 2014, 104, 73–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evola, R.S.; Peira, G.; Varese, E.; Bonadonna, A.; Vesce, E. Short Food Supply Chains in Europe: Scientific Research Directions. Sustainability 2022, 14, 3602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fardet, A.; Rock, E. Ultra-Processed Foods and Food System Sustainability: What Are the Links? Sustainability 2020, 12, 6280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, D.; Stanszus, L.; Geiger, S.; Grossman, P.; Schrader, U. Mindfulness and sustainable consumption: A systematic literature review of research approaches and findings. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 162, 544–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franzen, A.; Vogl, D. Time Preferences and Environmental Concern. Int. J. Sociol. 2013, 43, 39–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, L.; Sun, Z.; Zha, L.; Liu, F.; He, L.; Sun, X.; Jing, X. Environmental awareness and pro-environmental behavior within China’s road freight transportation industry: Moderating role of perceived policy effectiveness. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gamhewage, M.I.; Sivashankar, P.; Mahaliyanaarachchi, R.P.; Wijeratne, A.W.; Hettiarachchi, I.C. Women participation in urban agriculture and its influence on family economy - Sri Lankan experience. J. Agric. Sci. 2015, 10, 192–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Salirrosas, E.E.; Escobar-Farfán, M.; Gómez-Bayona, L.; Moreno-López, G.; Valencia-Arias, A.; Gallardo-Canales, R. Influence of environmental awareness on the willingness to pay for green products: an analysis under the application of the theory of planned behavior in the Peruvian market. Front. Psychol. 2024, 14, 1282383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garg, R.; Bansal, S.; Rathi, R.; Bhowmick, S. Mindful consumption – A systematic review and research agenda. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gifford, R. The dragons of inaction: Psychological barriers that limit climate change mitigation and adaptation. Am. Psychol. 2011, 66, 290–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gifford, R.; Nilsson, A. Personal and social factors that influence pro-environmental concern and behaviour: A review. Int. J. Psychol. 2014, 49, 141–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grando, S.; Carey, J.; Hegger, E.; Jahrl, I.; Ortolani, L. Short Food Supply Chains in Urban Areas: Who Takes the Lead? Evidence from Three Cities across Europe. Urban Agric. Reg. Food Syst. 2017, 2, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guiné, R.P.F.; Bartkiene, E.; Florença, S.G.; Djekić, I.; Bizjak, M.Č.; Tarcea, M.; Leal, M.; Ferreira, V.; Rumbak, I.; Orfanos, P.; et al. Environmental Issues as Drivers for Food Choice: Study from a Multinational Framework. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guri, F., Kokthi, E., Kelemen-Erdős, A. (2019). Consumers’ Perceptions about Food Safety Issues: Evidence from Albania. Management, Enterprise and Benchmarking in the 21st Century.

- Hale, J.; Knapp, C.; Bardwell, L.; Buchenau, M.; Marshall, J.; Sancar, F.; Litt, J.S. Connecting food environments and health through the relational nature of aesthetics: Gaining insight through the community gardening experience. Soc. Sci. Med. 2011, 72, 1853–1863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A.F. Partial, conditional, and moderated moderated mediation: Quantification, inference, and interpretation. Commun. Monogr. 2018, 85, 4–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A.F. Partial, conditional, and moderated moderated mediation: Quantification, inference, and interpretation. Commun. Monogr. 2018, 85, 4–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A.F.; Montoya, A.K. A Tutorial on Testing, Visualizing, and Probing an Interaction Involving a Multicategorical Variable in Linear Regression Analysis. Commun. Methods Meas. 2017, 11, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A.F.; Rockwood, N.J. Conditional Process Analysis: Concepts, Computation, and Advances in the Modeling of the Contingencies of Mechanisms. Am. Behav. Sci. 2019, 64, 19–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helm, S.V.; Pollitt, A.; Barnett, M.A.; Curran, M.A.; Craig, Z.R. Differentiating environmental concern in the context of psychological adaption to climate change. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2018, 48, 158–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hesty, W.; Hidayati, F.; Noor, I. A Proposed Sustainable Model of Food Systems. In Proceedings of the 3rd Annual International Conference on Public and Business Administration (AICoBPA 2020), Bogor, Indonesia; 2021; pp. 545–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hida, L., Karaulli, E., Kokthi, E., & Hasani, A. (2022). The impact of origin in the selection of children’s food-the-case of Albania and Kosovo.

- Howell, R.A. It's not (just) “the environment, stupid!” Values, motivations, and routes to engagement of people adopting lower-carbon lifestyles. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2013, 23, 281–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughner, R.S.; McDonagh, P.; Prothero, A.; Shultz, C.J.; Stanton, J. Who are organic food consumers? A compilation and review of why people purchase organic food. J. Consum. Behav. 2007, 6, 94–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hume, I.; Summers, D.; Cavagnaro, T. Self-sufficiency through urban agriculture: Nice idea or plausible reality? Sustain. Cities Soc. 2021, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Igartua, J.-J.; Hayes, A.F. Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: Concepts, Computations, and Some Common Confusions. Span. J. Psychol. 2021, 24, e49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iori, E.; Masotti, M.; Falasconi, L.; Risso, E.; Segrè, A.; Vittuari, M. Tell Me What You Waste and I’ll Tell You Who You Are: An Eight-Country Comparison of Consumers’ Food Waste Habits. Sustainability 2022, 15, 430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarzębowski, S.; Bourlakis, M.; Bezat-Jarzębowska, A. Short Food Supply Chains (SFSC) as Local and Sustainable Systems. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaçani, K.; Kokthi, E.; López-Bonilla, L.M.; González-Limón, M. Social tipping and climate change: The moderating role of social capital in bridging the gap between awareness and action. J. Int. Dev. 2024, 36, 2537–2556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karaulli, E., Hida, L., Kokthi, E., & Hasani, A. (2022). Will nutritionists reduce uncertainty in parents food choices? The case of baby food in Albania and Kosovo.

- Khurana, T. (2021). Role of women in sustainability (1).

- Kokthi, E.; Kruja, D.; Guri, F.; Zoto, O. Are the consumers willing to pay more for local fruits and vegetables? An empirical research on Albanian consumers. Prog. Agric. Eng. Sci. 2021, 17, 19–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kollmuss, A.; Agyeman, J. Mind the Gap: Why do people act environmentally and what are the barriers to pro-environmental behavior? Environ. Educ. Res. 2002, 8, 239–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kropp, C.; Antoni-Komar, I.; Sage, C. Food system transformations: Social movements, local economies, collaborative networks; Routledge, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- G, N.L.; N, P. Role of Women in Sustainable Agricultural Growth. In M. Kappagantual, B.N., P. V. Babu (Eds.), A Modern Approach to AI- Integrating Machine Learning with Agile Practices (pp. 125–133). QTanalytics India. [CrossRef]

- Liao, C.; Qiao, L.; Wang, X.; Lu, S. Exploring food waste prevention through advent food consumption: The role of perceived concern, consumer value, and impulse buying. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2022, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Xie, C.; She, S. Perception of delayed environmental risks: beyond time discounting. Disaster Prev. Manag. Int. J. 2014, 23, 112–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Low, B.S. Men, women, and sustainability. Popul. Environ. 1996, 18, 111–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majewski, E.; Komerska, A.; Kwiatkowski, J.; Malak-Rawlikowska, A.; Wąs, A.; Sulewski, P.; Gołaś, M.; Pogodzińska, K.; Lecoeur, J.-L.; Tocco, B.; et al. Are Short Food Supply Chains More Environmentally Sustainable than Long Chains? A Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) of the Eco-Efficiency of Food Chains in Selected EU Countries. Energies 2020, 13, 4853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malak-Rawlikowska, A.; Majewski, E.; Wąs, A.; Borgen, S.O.; Csillag, P.; Donati, M.; Freeman, R.; Hoàng, V.; Lecoeur, J.-L.; Mancini, M.C.; et al. Measuring the Economic, Environmental, and Social Sustainability of Short Food Supply Chains. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsden, T.; Banks, J.; Bristow, G. Food Supply Chain Approaches: Exploring their Role in Rural Development. Sociol. Rural. 2000, 40, 424–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayflor, G. Agustin. (2022). Development and Validation of a Test to Measure Student’s Climate Change Awareness (CCA) Toward Sustainable Development Goals. [CrossRef]

- Migliore, G.; Thrassou, A.; Crescimanno, M.; Schifani, G.; Galati, A. Factors affecting consumer preferences for “natural wine”. Br. Food J. 2020, 122, 2463–2479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakajima, M. Sustainable Food Consumption: Demand for Local Produce in Singapore. Sustainability 2022, 14, 12330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, M.E.; Hamm, M.W.; Hu, F.B.; Abrams, S.A.; Griffin, T.S. Alignment of Healthy Dietary Patterns and Environmental Sustainability: A Systematic Review. Adv. Nutr. 2016, 7, 1005–1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’neill, C.; Hashem, S.; McCarthy, M.; Moran, C. (2024). Infrastructure, Impulsivity, and Waste. Exploring the (Un)sustainable Routines of Mainstream Food Shoppers. In A. Dulsrud, F. Forno (Eds.), Digital Food Provisioning in Times of Multiple Crises: How Social and Technological Innovations Shape Everyday Consumption Practices (pp. 93–118). Springer International Publishing. [CrossRef]

- O'Neill, K. Linking wastes and climate change: Bandwagoning, contention, and global governance. WIREs Clim. Chang. 2018, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owen, L.; Udall, D.; Franklin, A.; Kneafsey, M. Place-Based Pathways to Sustainability: Exploring Alignment between Geographical Indications and the Concept of Agroecology Territories in Wales. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schultz, P.W. THE STRUCTURE OF ENVIRONMENTAL CONCERN: CONCERN FOR SELF, OTHER PEOPLE, AND THE BIOSPHERE. J. Environ. Psychol. 2001, 21, 327–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plender, C. “It’s a Co-op in Spirit, That’s What It Is”: Fostering Collaboration, Collectivity, and Egalitarianism in Food Cooperatives. Krit. etnografi: Swed. J. Anthr. 2022, 5, 77–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poortinga, W.; Demski, C.; Steentjes, K. Generational differences in climate-related beliefs, risk perceptions and emotions in the UK. Commun. Earth Environ. 2023, 4, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pulighe, G.; Lupia, F. Food First: COVID-19 Outbreak and Cities Lockdown a Booster for a Wider Vision on Urban Agriculture. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seyfang, G. (2006). Community currencies: A new tool for sustainable consumptions? (CSERGE Working Paper EDM 06–09). University of East Anglia, The Centre for Social and Economic Research on the Global Environment (CSERGE). https://hdl.handle.net/10419/80270.

- Shen, M.; Wang, J. The Impact of Pro-environmental Awareness Components on Green Consumption Behavior: The Moderation Effect of Consumer Perceived Cost, Policy Incentives, and Face Culture. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 580823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shourove, J.H.; Meem, F.C.; Rahman, M.; Islam, G.M.R. Is women’s household decision-making autonomy associated with their higher dietary diversity in Bangladesh? Evidence from nationally representative survey. PLOS Glob. Public Heal. 2023, 3, e0001617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, E.K.; Mayer, A. A social trap for the climate? Collective action, trust and climate change risk perception in 35 countries. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2018, 49, 140–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, T.A.; Huang, C.L.; Lin, B.-H. Does Price or Income Affect Organic Choice? Analysis of U.S. Fresh Produce Users. J. Agric. Appl. Econ. 2009, 41, 731–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snelgar, R.S. Egoistic, altruistic, and biospheric environmental concerns: Measurement and structure. J. Environ. Psychol. 2006, 26, 87–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castellano, R.L.S. Alternative Food Networks and the Labor of Food Provisioning: A Third Shift? Rural Sociol. 2016, 81, 445–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stefani, G.; Romano, D.; Cavicchi, A. Consumer expectations, liking and willingness to pay for specialty foods: Do sensory characteristics tell the whole story? Food Qual. Preference 2006, 17, 53–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stern, P.C. New environmental theories: Toward a coherent theory of environmentally significant behavior. J. Soc. Issues 2000, 56, 407–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tandon, A.; Dhir, A.; Kaur, P.; Kushwah, S.; Salo, J. Why do people buy organic food? The moderating role of environmental concerns and trust. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2020, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thyberg, K.L.; Tonjes, D.J. Drivers of food waste and their implications for sustainable policy development. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2016, 106, 110–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tobler, C.; Visschers, V.H.; Siegrist, M. Eating green. Consumers’ willingness to adopt ecological food consumption behaviors. Appetite 2011, 57, 674–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tobler, C.; Visschers, V.H.; Siegrist, M. Addressing climate change: Determinants of consumers' willingness to act and to support policy measures. J. Environ. Psychol. 2012, 32, 197–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vermeir, I.; Verbeke, W. Sustainable Food Consumption: Exploring the Consumer “Attitude—Behavioral Intention” Gap. J. Agric. Environ. Ethics 2006, 19, 169–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vermeir, I.; Verbeke, W. Sustainable food consumption among young adults in Belgium: Theory of planned behaviour and the role of confidence and values. Ecol. Econ. 2008, 64, 542–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verplanken, B.; Sato, A. The Psychology of Impulse Buying: An Integrative Self-Regulation Approach. J. Consum. Policy 2011, 34, 197–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vittersø, G.; Torjusen, H.; Laitala, K.; Tocco, B.; Biasini, B.; Csillag, P.; de Labarre, M.D.; Lecoeur, J.-L.; Maj, A.; Majewski, E.; et al. Short Food Supply Chains and Their Contributions to Sustainability: Participants’ Views and Perceptions from 12 European Cases. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, L.; Spence, M.T. Causes and consequences of emotions on consumer behaviour: A review and integrative cognitive appraisal theory. Eur. J. Mark. 2007, 41, 487–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wells, V.K.; Ponting, C.A.; Peattie, K. Behaviour and climate change: Consumer perceptions of responsibility. J. Mark. Manag. 2011, 27, 808–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolf, J.; Moser, S.C. Individual understandings, perceptions, and engagement with climate change: insights from in-depth studies across the world. WIREs Clim. Chang. 2011, 2, 547–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Li, W.; Chi, S. Altruism, Environmental Concerns, and Pro-environmental Behaviors of Urban Residents: A Case Study in a Typical Chinese City. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yiridoe, E.K.; Bonti-Ankomah, S.; Martin, R.C. Comparison of consumer perceptions and preference toward organic versus conventionally produced foods: A review and update of the literature. Renew. Agric. Food Syst. 2005, 20, 193–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zepeda, L.; Nie, C. What are the odds of being an organic or local food shopper? Multivariate analysis of US food shopper lifestyle segments. Agric. Hum. Values 2012, 29, 467–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

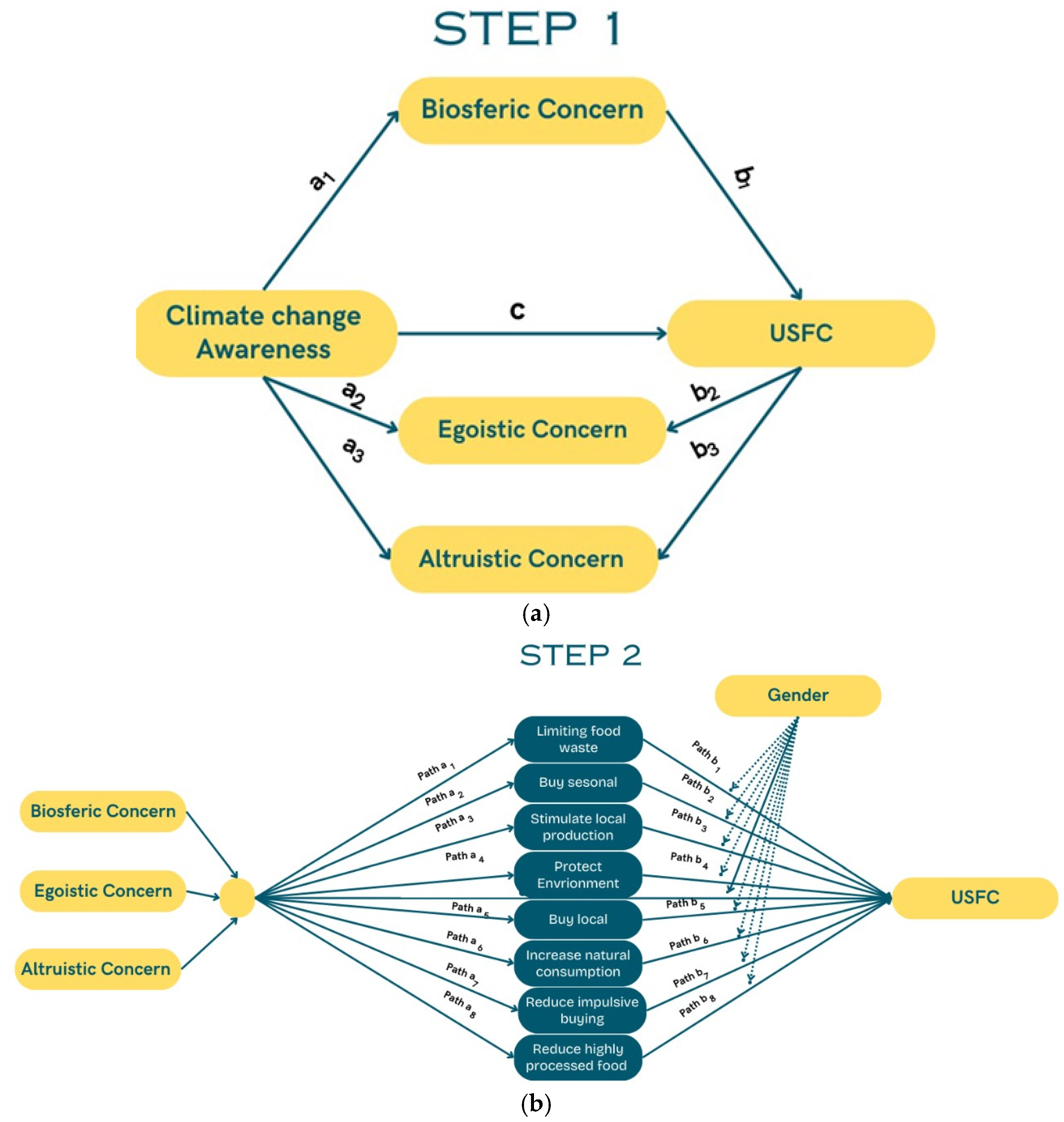

| Drivers | Pathway | Hypotheses |

|---|---|---|

| Biospheric concern |

Path a1: CCA → Biospheric Concern; Path b1: Biospheric Concern → USFC |

H1:1a CCA positively influences Biospheric Concern, |

| H1: 1b Biospheric Concern, positively affecting participation in USFC | ||

|

Egoistic concern |

Path a2: CCA → Egoistic Concern; Path b2: Egoistic Concern → USFC |

H1:2a CCA positively influences Egostic Concern, |

| H1:2b Egostic Concern, positively affecting participation in USFC | ||

| Altruistic concern |

Path a3: CCA → Altruistic Concern; Path b3: Altruistic Concern → USFC |

H1:3a CCA positively influences Altruistic Concern, |

| H1:3b Altruistic Concern, positively affecting participation in USFC |

| Drivers | Hypotheses | References |

|---|---|---|

|

Limiting Food Waste |

H 2.1: Climate Change Concern (CCC)

→

Limiting Food Waste

→

USFC

|

(Iori et al., 2022; Liao et al., 2022) (O’Neill, 2019). (Conrad & Blackstone, 2021;, Thyberg & Tonjes, 2016) |

| Buying Seasonal Products | H2.2: CCC → Buying Seasonal Products → USFC | (Dentoni et al., 2009; Edwards-Jones, 2010; Jarzębowski et al., 2020). |

| Stimulating Local Production | H2.3: CCC → Stimulating Local Production → USFC | (Chiffoleau & Dourian, 2020a; Edwards-Jones, 2010; Evola et al., 2022; Vittersø et al., 2019) |

| Protecting the Environment | H2.4: CCC → Protecting the Environment → USFC | (Bimbo et al., 2020; Shen & Wang, 2022; Tobler et al., 2012; Wells et al., 2011) |

| Buying Local Products | H2.5: CCC → Buying Local Products → USFC | (Dentoni et al., 2009; Edwards-Jones, 2010). |

| Increasing Natural Consumption | H2.6: CCC → Increasing Natural Consumption → USFC | (Hughner et al., 2007; Migliore et al., 2020; Tandon et al., 2020) (Bimbo et al., 2020; Endrizzi et al., 2021; Jarzębowski et al., 2020; Kokthi et al., 2021) |

| Reducing Impulsive Buying |

H2.7: CCC → Reducing Impulsive Buying → USFC |

(Ericson et al., 2014) (O’Neill et al., 2024, 2024; Verplanken & Sato, 2011) (Bahl et al., 2016; Fischer et al., 2017; Garg et al., 2024). |

| Reducing Highly Processed Food Consumption |

H2.8: CCC → Reducing Highly Processed Food Consumption → USFC | (Casas, 2022; Fardet & Rock, 2020)(Nelson et al., 2016). (Allaire & Vandecandelaere, 2010) |

| Category | Description |

|---|---|

| Socio-Demographic Characteristics | City (Tirana), Age, Gender, Educational level, Family Income, Parenthood status, Number and Age of children |

| Climate Change Awareness (CCA) | Awareness of air pollution, vehicle emissions, water pollution, chemical fertilizers, green space loss, and land degradation (1=Not informed, 5=Very informed) |

| Environmental Concerns | Concerns about environmental impact on plants, marine life, birds, animals, self, health, future, all people, and children (1=Not concerned, 5=Extremely concerned) |

| Sustainable Consumption & Food Preferences | Preferred food sourcing for school catering, willingness to pay more, motivations for paying more (e.g., limiting waste, seasonal food, reducing processed food), understanding of sustainable food consumption |

| Demographics | Value | Frequency | Frequency percentage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Female | 208 | 91% |

| Male | 20 | 9% | |

| Age | 18-25 | 6 | 2.6% |

| 26-35 | 110 | 47.8% | |

| 36-45 | 78 | 33% | |

| 46-55 | 30 | 13% | |

| Over 55 | 6 | 2.6% | |

| Educational Level | Up to 9 years | 4 | 1% |

| 12 years | 14 | 5% | |

| University degree | 108 | 47% | |

| Post university degree | 108 | 47% | |

| Monthly incomes Eur |

100 – 300 | 6 | 2.6 |

| 3001 – 600 | 24 | 10.4 | |

| 601 – 900 | 74 | 32.5 | |

| 1000+ | 124 | 53.8 | |

| Parent | Yes | 220 | 95.7 |

| No | 10 | 4.3 | |

| Number of children | 1 | 102 | 44.3 |

| 2 | 118 | 51.3 | |

| 3 | 10 | 4.3 | |

| 4 | - | - | |

| Over 4 | - | - | |

| Children’s age | Six months-3years | 56 | 24.3 |

| 3 years-5 years | 56 | 24.3 | |

| 5 years-12 years | 64 | 27.8 | |

| 12-15years | 16 | 7 | |

| 15-18 years | 38 | 16.5 |

| 1 | ||

| Question | Mean | StdD |

| Are you aware of the danger of vehicle gas emissions that harm people’s health? | 3.96 | 1.061 |

| Are you aware that using chemical fertilisers and pesticides will cause environmental damage? | 4.17 | 0.952 |

| Are you aware of the dangers of air pollution due to urbanisation? | 4.21 | 0.881 |

| Have you been informed about the dangers of water pollution? | 4.12 | 1.046 |

| Are you aware of the dangers of insufficient green space? | 4.03 | 1.113 |

| Have you been informed about the damage caused by the degradation of cultivated land quality? | 3.86 | 1.214 |

| 2 | ||

| Concern for... | Mean | StdD |

| Plants | 3.98 | 0.771 |

| Aquatic life | 4.01 | 0.778 |

| Birds | 3.92 | 0.831 |

| Myself | 4.55 | 0.660 |

| My health | 4.69 | 0.557 |

| Children’s Health | 4.78 | 0.479 |

| My future | 4.67 | 0.595 |

| All individuals | 4.59 | 0.640 |

| 3 | ||

| Driver | Mean | StdD |

| Buy locally produced foods to limit transportation | 3.87 | 1.070 |

| Increasing the consumption of natural foods | 4.55 | 0.860 |

| Promotion of local agricultural/livestock production | 4.08 | 0.950 |

| Purchase and consumption of seasonal foods | 4.61 | 1.040 |

| Reducing food waste | 3.78 | 0.890 |

| Reducing the consumption of highly processed foods | 4.38 | 1.020 |

| Reduction of excessive consumption that comes from impulsive purchases | 4.15 | 1.010 |

| The need to protect the natural environment | 3.92 | 1.050 |

| Hypothesis | Path | R-squared | (Effect) | p-value | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H: CCA → Biospheric Concern | Path a1 | 0.111 | 0.252 | <0.001 | CCA significantly increases Biospheric Concern |

| H: Biospheric Concern → USFC | Path b1 | 0.036 | 0.028 (Indirect) | >0.05 | No significant indirect effect on USFC participation |

| H1: CCA → Egoistic Concern | Path a2 | 0.041 | 0.113 | 0.003 | CCA significantly increases Egoistic Concern |

| H:Egoistic Concern → USFC | Path b2 | 0.036 | -0.102 (Indirect) | <0.05 | Egoistic Concern negatively mediates the effect on USFC participation. |

| H:CCA → Altruistic Concern | Path a3 | 0.024 | 0.076 | 0.023 | CCA significantly increases Altruistic Concern |

| H: Altruistic Concern → USFC | Path b3 | 0.036 | 0.062 (Indirect) | 0.044 | Altruistic Concern positively mediates the effect on USFC participation. |

| Total Effect of CCA on USFC | Total Path | 0.036 | -0.141 | 0.16 | No significant total effect of CCA on USFC participation |

| Direct Effect of CCA on USFC | Direct Path | 0.036 | -0.129 | 0.223 | No significant direct effect of CCA on USFC participation |

| Interaction Effects | M1- Biospheric, M2- Egoistic, M3-Altruistic | - | Not significant | - | Interaction effects were not significant. |

| H | OV | R2 (ECB) | Coefficient ECB |

p-value ECB | R2 ECE | Effect ECE | p-value ECE | R2 (ECA) | Coefficient ECA | p-value ECA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H2.1 | Limiting Food Waste | 0.090 | 0.349 | <0.000 | 0.036 | 0.200 | 0.009 | 0.111 | 0.393 | <0.0001 |

| H2.2 | Buying Seasonal | 0.101 | 0.304 | <0.000 | 0.110 | 0.287 | <0.000 | 0.188 | 0.423 | <0.0001 |

| H2.3 | Stimulating Local Prod | 0.156 | 0.439 | <0.000 | 0.088 | 0.304 | <0.000 | 0.172 | 0.468 | <0.0001 |

| H2.4 | Protecting Environment | 0.154 | 0.404 | <0.000 | 0.097 | 0.294 | <0.000 | 0.166 | 0.425 | <0.0001 |

| H2.5 | Buying Local Products | 0.065 | 0.280 | 0.000 | 0.034 | 0.188 | 0.010 | 0.096 | 0.345 | <0.0001 |

| H2.6 | Increasing Natural Cons | 0.156 | 0.394 | <0.0001 | 0.126 | 0.321 | <0.0001 | 0.218 | 0.473 | <0.000 |

| H2.7 | Reducing Impulsive Buy | 0.074 | 0.301 | 0.000 | 0.086 | 0.299 | <0.0001 | 0.113 | 0.377 | <0.000 |

| H2.8 | Reducing Processed Food | 0.136 | 0.415 | <0.0001 | 0.156 | 0.406 | <0.0001 | 0.230 | 0.546 | <0.000 |

| H2.9 | WTP (Overall Model) | 0.131 | 0.6520 (Direct effect) | 0.092 | 0.146 | 0.3387 (Direct effect) | 0.318 | 0.122 | 0.6520 (Direct effect) | 0.092 |

| Limiting waste | - | 0.502 | 0.002 | - | 0.448 | 0.006 | - | 0.502 | 0.002 | |

| Buying Seasonal | - | -0.207 | 0.534 | - | -0.236 | 0.476 | - | -0.207 | 0.534 | |

| Protecting environment | - | -0.297 | 0.158 | - | -0.213 | 0.306 | - | -0.297 | 0.158 | |

| Stimulating local production | - | 0.067 | 0.775 | - | 0.047 | 0.837 | - | 0.067 | 0.775 | |

| Increasing natural consumption | - | -0.663 | 0.022 | - | -0.731 | 0.011 | - | -0.663 | 0.022 | |

| Reducing Impulsive bying | - | -0.323 | 0.096 | - | -0.291 | 0.120 | - | -0.323 | 0.096 | |

| Reducing Processed food consumption | - | 0.370 | 0.095 | - | 0.418 | 0.054 | - | 0.370 | 0.095 | |

| Buying Local | - | 0.000 | 1.000 | - | -0.017 | 0.919 | - | 0.000 | 1.000 | |

| Interaction (Gender) | - | -0.730 | 0.021 | - | -0.560 | 0.032 | - | -0.730 | 0.021 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).