Submitted:

20 March 2025

Posted:

21 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. The Current State of the Research Field

1.2. Measuring and Modelling the HTC

1.3. The Knowledge Gap

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Linking the HTC to Dynamic Heat Transfer in a Building

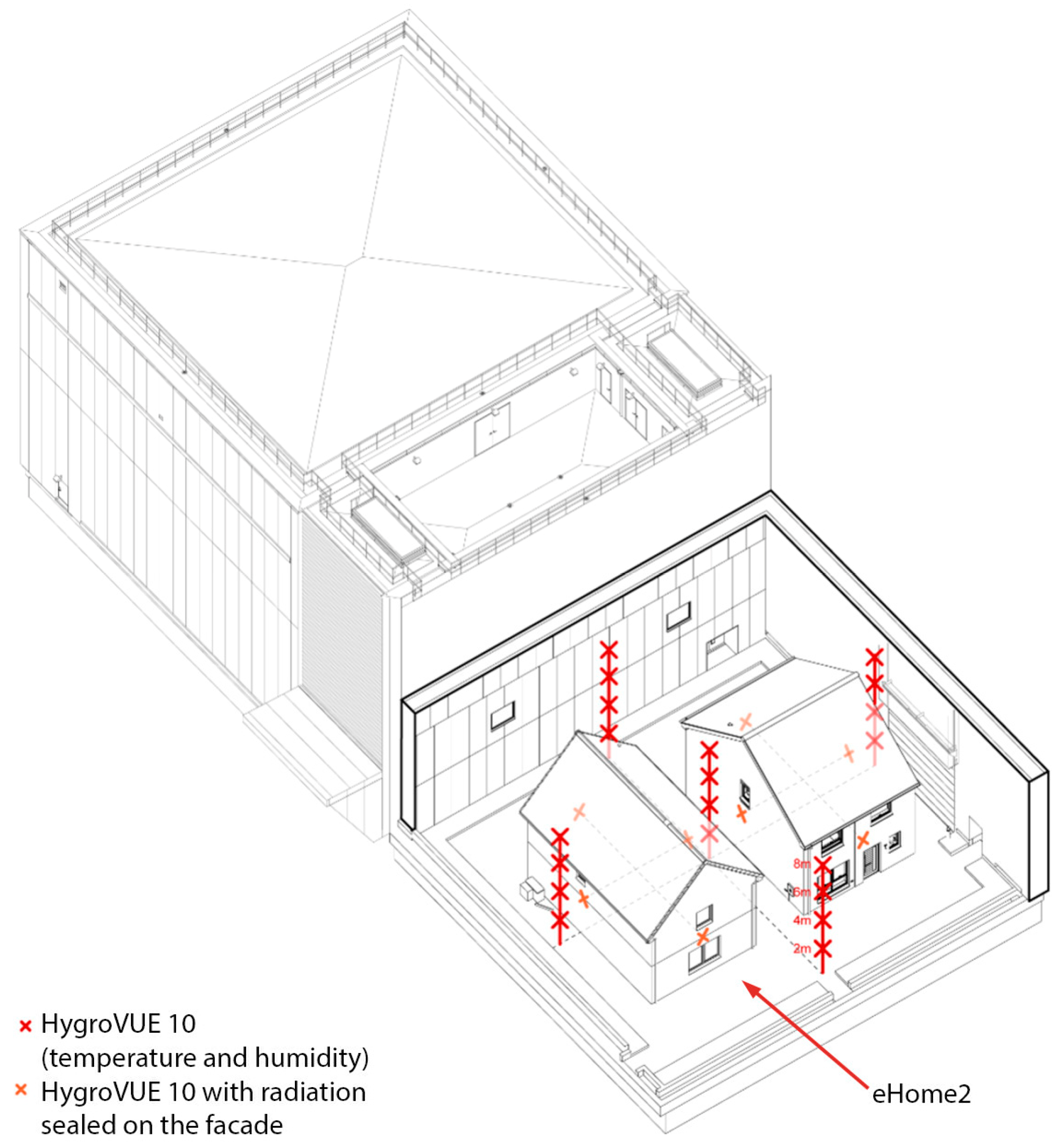

2.2. The Test Facility

- Temperature: (-20 °C to 40 °C)

- Relative Humidity (20% to 90%)

- Wind (up to ~17 m/s)

- Rain (up to 200 mm/h)

- Solar Radiation (up to 1200 W/m2)

- Snow (up to 250 mm per day)

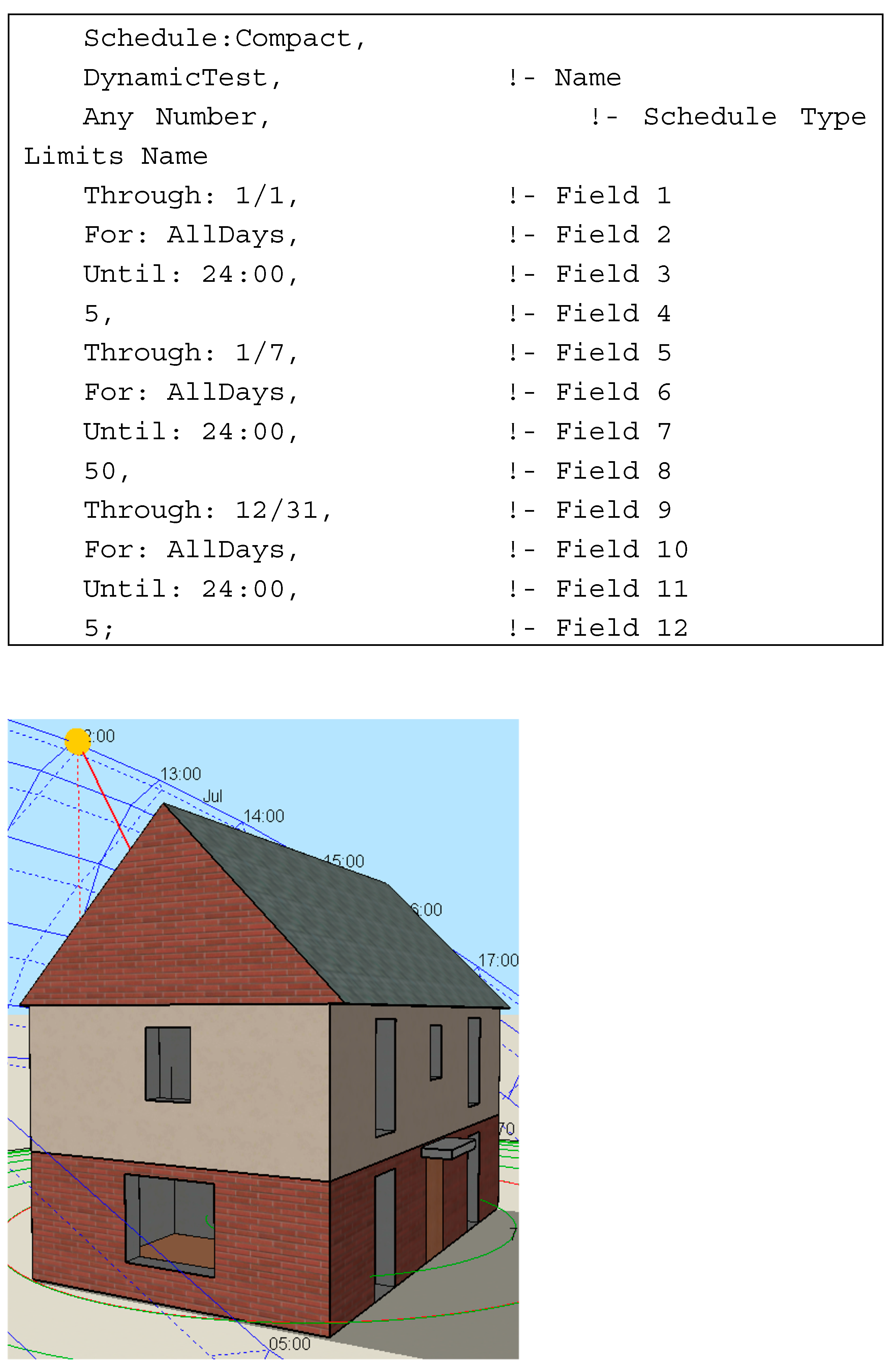

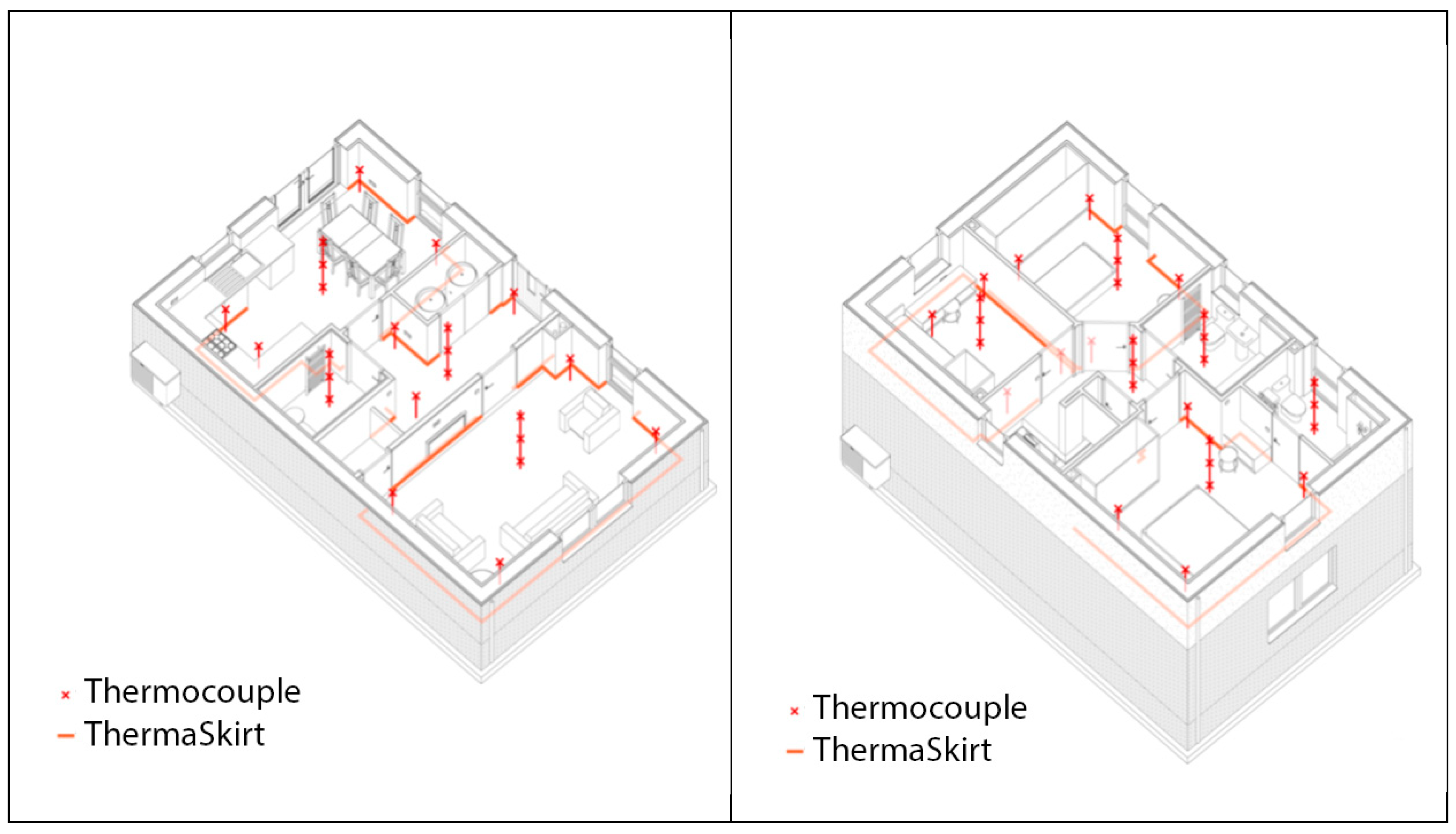

2.3. The Test Building—eHome2

2.4. Simulation Models

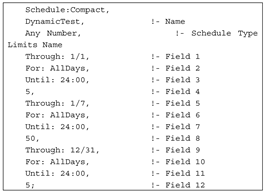

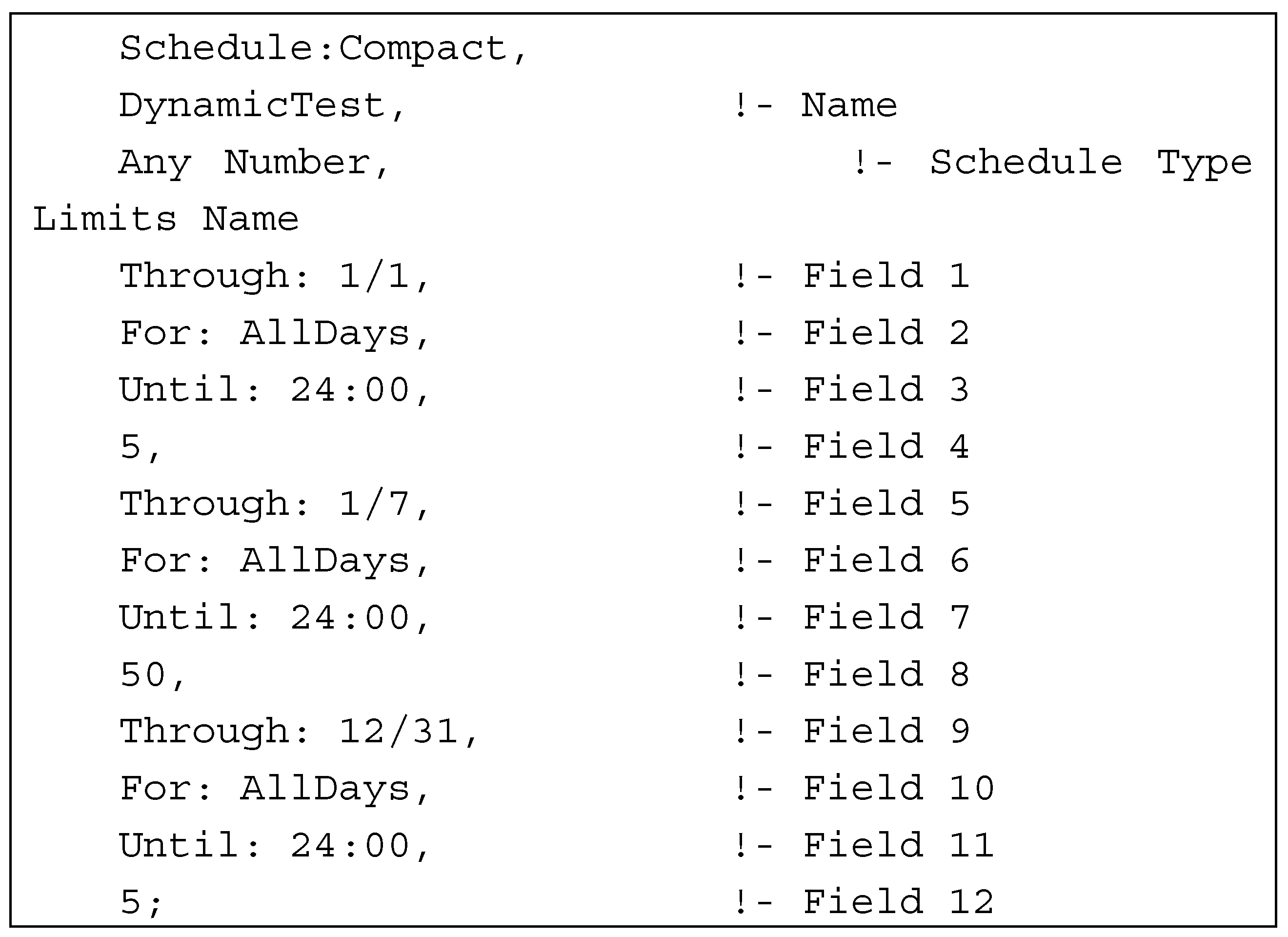

is that the building internal air temperature is kept at 5 °C over the first 24 hours of the simulation, where ‘1/1’ denotes ‘month/day’, and then for the next seven days, until day 7 of month 1 the target temperature is set to 50 °C, and after that it is set back to 5 °C again for the rest of the simulation year. The text after the exclamation symbol on every line represent comments.

is that the building internal air temperature is kept at 5 °C over the first 24 hours of the simulation, where ‘1/1’ denotes ‘month/day’, and then for the next seven days, until day 7 of month 1 the target temperature is set to 50 °C, and after that it is set back to 5 °C again for the rest of the simulation year. The text after the exclamation symbol on every line represent comments.2.3. Monitored Data

-

eHome2:

- Air temperature in seven points in each room

- Operative temperature in seven points in each room

- Relative humidity in the geometric center of each room

- Electrical energy consumption

- Heat meter output on ASHP primary flow and return

- Electrical energy consumption by circuit and by individual power outlet

-

Chamber:

- Air temperature at 36 points

- Relative humidity at 36 points

- Sub soil temperature under the center of each house

2.5. Machine Learning of the HTC Using Measured Data

3. Experiments and Results

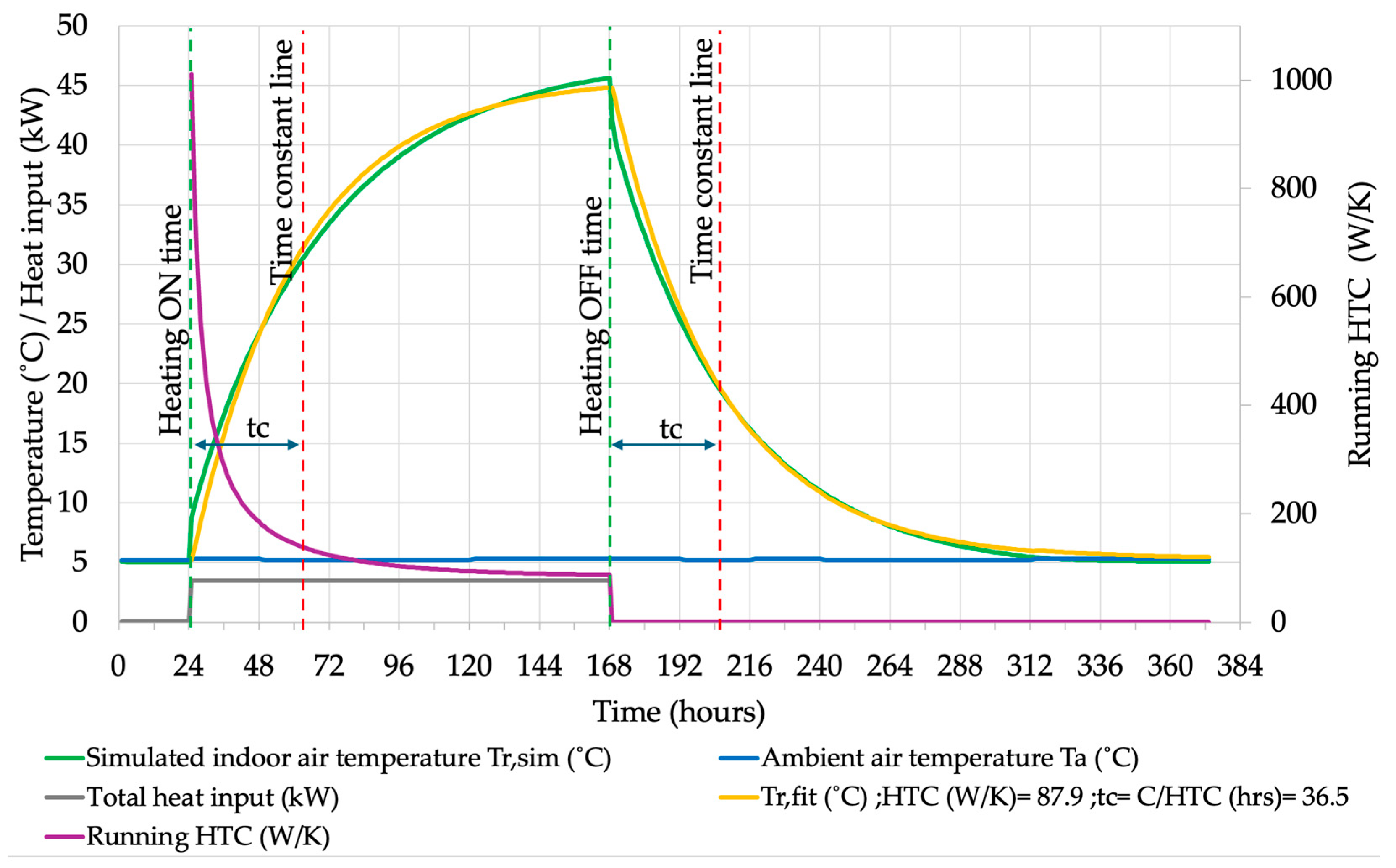

3.1. HTC During a Dynamic Heating and Cooling Down Test Simulation with a Calibrated Model

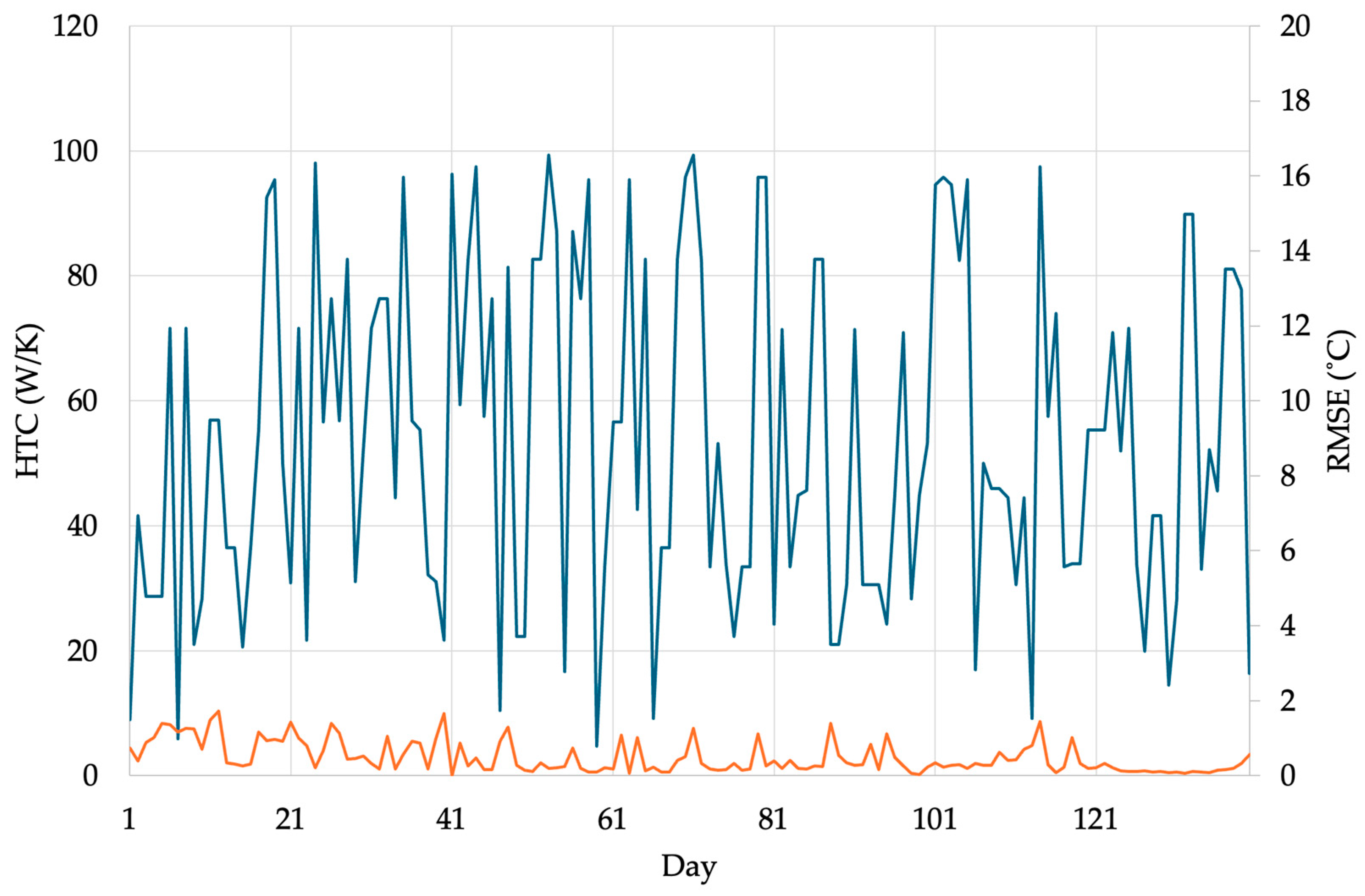

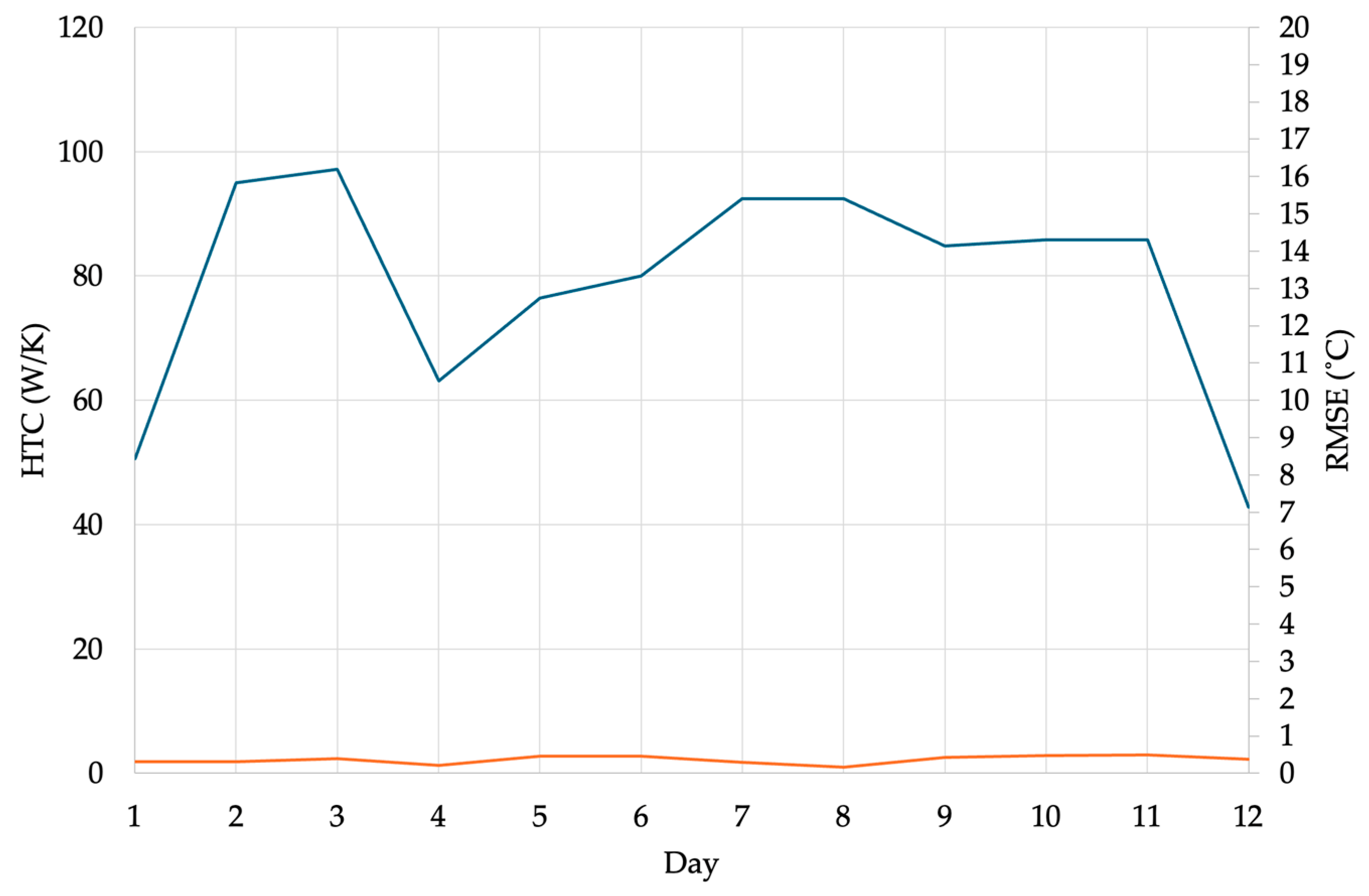

3.2. Machine Learning of Daily HTC Variations Using Measured Data

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Nomenclature

| ρ | density (kg/m3) |

| Ai | floor area of each individual zone (m2) |

| Ai | surface area of the i-th building element (m²) |

| B | proportionality constant in Equation (17) |

| C | effective thermal capacitance in MJ/K |

| c | specific heat (J/(kg∙K)) |

| d | wall thickness in meters (m) |

| GA | Genetic Algorithm |

| Hc | conductive heat loss coefficient (W/K) |

| Htb | thermal bridging heat loss coefficient (W/K) |

| HTC | heat transfer coefficient (W/K) |

| Hv | ventilation and infiltration heat loss coefficient (W/K) |

| i | individual zone index as in Table 5 |

| k | thermal conductivity in W/(m∙K) |

| Li | length of the i-th linear thermal bridge (m) |

| m | mass (kg) |

| n | number of building elements |

| N | volume air change per hour (h⁻¹) |

| OHTC | Operational HTC (W/K) |

| q̇ | heat flux (W/m2) |

| Q | overall heat loss rate (W) |

| Qint | internal heat gain in the building arising from heating or from casual gains (W). |

| Qloss | heat gain from solar radiation (W) |

| Qsol | heat gain from solar radiation (W) |

| R1, R2, R3… | resistances of individual construction layers (m2K/W) |

| Ri | internal surface resistance (m2K/W) |

| RMSE | root mean squared error (°C) |

| RMSEMAX | Error tolerance for GA learning (°C) |

| Ro | external surface resistance (m2K/W) |

| T | temperature (°C) |

| t | time (s) |

| Tamb | difference between ambient air temperature and the initial room temperature Ta—Tr,0. (°C) |

| THTC | Test or Theoretical HTC (W/K) |

| Ti | internal air temperature (K) |

| Ti | middle shielded room temperature for each individual zone (°C) |

| To | external air temperature (°C). |

| Troom | difference between room temperature and the initial room temperature Tr—Tr,0 (°C) |

| OTTV | Overall Thermal Transfer Value (W/m2) |

| QUB | Quick U-value of Buildings |

| Ui | thermal conductance of the i-th building element (W/(m²K)) |

| V | volume (m3) |

| z | proportionality constant that represents the relationship B/V in Equation (18). |

| α | thermal diffusivity (m2/s) |

| Ψi | linear thermal transmittance of the i-th thermal bridge (W/(m∙K)) |

References

- ISO. 13789:2017 Thermal Performance of Buildings — Transmission Heat Loss Coefficient — Calculation Method; ISO 13789:2017; Geneva.

- Eastwood, M. Variability in the Heat Transfer Coefficient of Dwellings. 2025, 80030983 Bytes. [CrossRef]

- Li, M. Thermal Performance of UK Dwellings: Assessment of Methods for Quantifying Whole-Dwelling Heat Loss in Occupied Homes. 2022, 12284773 Bytes. [CrossRef]

- Sougkakis, V.; Meulemans, J.; Wood, C.; Gillott, M.; Cox, T. Field Testing of the QUB Method for Assessing the Thermal Performance of Dwellings: In Situ Measurements of the Heat Transfer Coefficient of a circa 1950s Detached House in UK. Energy and Buildings 2021, 230, 110540. [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, N.; Ghiaus, C.; Qureshi, M. Error Analysis of QUB Method in Non-Ideal Conditions during the Experiment. Energies 2020, 13, 3398. [CrossRef]

- Juricic, S.; Rabouille, M.; Challansonnex, A.; Jay, A.; Thébault, S.; Rouchier, S.; Bouchié, R. The Sereine Test: Advances towards Short and Reproducible Measurements of a Whole Building Heat Transfer Coefficient. Energy and Buildings 2023, 299, 113585. [CrossRef]

- Vighio, A.A.; Zakaria, R.; Ahmad, F.; Aminuddin, E. Real-Time Monitoring and Development of a Localized OTTV Equation for Building Energy Performance. Civ Eng J 2025, 11, 544–564. [CrossRef]

- David Allinson Technical Evaluation of SMETER Technologies (TEST) Project; Department for Business, Energy & Industrial Strategy, 2022; p. 183;.

- 2023; 9. Build Test Solutions & SOAP Retrofit SmartHTC Validation Report; 2023;

- Aico Utilising IOT Technology To Validate Retrofit Interventions (No. HomeLINK; p. 9) Available online: https://www.aico.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2024/08/Retrofit-Validation-Case-Study-Aico-x-CorkSol.pdf.

- Fitton, R. Building Energy Performance Assessment Based on In-Situ Measurements : Challenges and General Framework; IEA EBC Annex 71; KU Leuven, Belgium, 2021;

- Johnston, D.; Miles-Shenton, D.; Wingfield, J.; Farmer, D.; Bell, M. Whole House Heat Loss Test Method (Coheating); Leeds Metropolitan University: Leeds, UK, 2012;

- Fitton, R. BS EN 17887-1:2024 Thermal Performance of Buildings. In Situ Testing of Completed Buildings. Data Collection for Aggregate Heat Loss Test (Part 1); 2024.

- Marshall, A.; Fitton, R.; Swan, W.; Farmer, D.; Johnston, D.; Benjaber, M.; Ji, Y. Domestic Building Fabric Performance: Closing the Gap between the in Situ Measured and Modelled Performance. Energy and Buildings 2017, 150, 307–317. [CrossRef]

- Farmer, D.; Gorse, C.; Swan, W.; Fitton, R.; Brooke-Peat, M.; Miles-Shenton, D.; Johnston, D. Measuring Thermal Performance in Steady-State Conditions at Each Stage of a Full Fabric Retrofit to a Solid Wall Dwelling. Energy and Buildings 2017, 156, 404–414. [CrossRef]

- Jack, R.; Loveday, D.; Allinson, D.; Lomas, K. First Evidence for the Reliability of Building Co-Heating Tests. Building Research & Information 2018, 46, 383–401. [CrossRef]

- HM Government BEIS. SAP 10.2: The Government’s Standard Assessment Procedure for Energy Rating of Dwellings; BRE Garston, Watford, WD25 9XX, 2023.

- DesignBuilder Software Ltd. DesignBuilder 2024.

- Johnston, D.; Miles-Shenton, D.; Farmer, D. Quantifying the Domestic Building Fabric ‘Performance Gap.’ Building Services Engineering Research and Technology 2015, 36, 614–627. [CrossRef]

- Parker, J.; Farmer, D.; Johnston, D.; Fletcher, M.; Thomas, F.; Gorse, C.; Stenlund, S. Measuring and Modelling Retrofit Fabric Performance in Solid Wall Conjoined Dwellings. Energy and Buildings 2019, 185, 49–65. [CrossRef]

- Fitton, R.; Diaz Hernandez, H.; Farmer, D.; Henshaw, G.; Sitmalidis, A.; Swan, W. Saint Gobain & Barratt Developments “eHome2” Baseline Performance Report.; Salford: ERDF & Innovate UK, 2024;

- Alzetto, F.; Pandraud, G.; Fitton, R.; Heusler, I.; Sinnesbichler, H. QUB: A Fast Dynamic Method for in-Situ Measurement of the Whole Building Heat Loss. Energy and Buildings 2018, 174, 124–133. [CrossRef]

- Veritherm: Identifying Consumer Routes to Market for Thermal Testing. Energy Systems Catapult 2024.

- Jankovic, L. Designing Zero Carbon Buildings: Embodied and Operational Emissions in Achieving True Zero; Third edition.; Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group: Abingdon, Oxon ; New York, NY, 2024; ISBN 978-1-03-237871-8.

- Lienhard, J.H., V.; Lienhard, J.H., IV A Heat Transfer Textbook; 6th ed.; Phlogiston Press: Cambridge, MA, 2024;

- Fourier, J.B.J. The Analytical Theory of Heat; 1st ed.; Cambridge University Press, 2009; ISBN 978-1-108-00178-6.

- Tsang, C.; Fitton, R.; Zhang, X.; Henshaw, G.; Diaz Hernandez, H.; Farmer, D.; Allinson, D.; Sitmalidis, A.; Dgali, M.; Jankovic, L.; et al. Dataset for Article: “Calibration of Building Performance Simulations for Zero Carbon Ready Homes: Two Open Access Case Studies in Controlled Conditions” 2025.

- DOE EnergyPlus 2024.

| HTC measurement method |

HTC value (W/K) |

Difference from coheating (%) |

| Coheating | 76.7±2.1 | |

| QUB | 65.1±5.6 | -15 |

| Veritherm | 71.9 | -6 |

| Layer | Material | Thickness (mm) | Conductivity (W/mK) |

Thermal resistance (m2K/W) |

| Brick external wall | ||||

| External finish | Weberwall brick slip finishing system | 15 | 0.72 | 0.021 |

| External board | BG glassroc x | 12.5 | 0.1865 | 0.067 |

| Cavity | Ventilated cavity | 25 | - | 0.71 |

| Sheathing | Oriented Strand Board | 9 | 0.13 | 0.069 |

| Outer Insulation | TFR35 Insulation, 8.8% bridging with flange (λ = 0.13) | 47 | 0.035 | 0.947 |

| Core insulation | TFR35 Insulation, 1.7% bridging with flange (λ = 0.13) | 151 | 0.035 | 3.831 |

| Inner insulation | TFR35 Insulation, 8.8% bridging with flange (λ = 0.13) | 47 | 0.035 | 0.947 |

| Additional sheathing | Oriented Strand Board | 9 | 0.13 | 0.069 |

| Service void | Service void with 8.8% bridging with wooden battens (λ = 0.13) | 35 | - | 0.518 |

| Internal Finish | Gyproc Wallboard | 15 | 0.19 | 0.079 |

| Rendered external wall | ||||

| External finish | Webersill TF finish coat and Weberend LCA rapid base coat | 7.5 | 0.72 | 0.0104 |

| External board | BG glassroc x | 12.5 | 0.1865 | 0.067 |

| Cavity | Ventilated cavity | 25 | - | 0.71 |

| Sheathing | Oriented Strand Board | 9 | 0.13 | 0.069 |

| Outer Insulation | TFR35 Insulation, 8.8% bridging with flange (λ = 0.13) | 47 | 0.035 | 0.947 |

| Core insulation | TFR35 Insulation, 1.7% bridging with flange (λ = 0.13) | 151 | 0.035 | 3.831 |

| Inner insulation | TFR35 Insulation, 8.8% bridging with flange (λ = 0.13) | 47 | 0.035 | 0.947 |

| Additional sheathing | Oriented Strand Board | 9 | 0.13 | 0.069 |

| Service void | Service void with 8.8% bridging with wooden battens (λ = 0.13) | 35 | - | 0.518 |

| Internal Finish | Gyproc Wallboard | 15 | 0.19 | 0.079 |

| Loft ceiling | ||||

| Primary insulation | Isover Spacesaver roof insulation | 300 | 0.044 | 6.818 |

| Secondary insulation | Isover Spacesaver roof insulation, 9% bridging with wooden batons (λ = 0.13) | 100 | 0.044 | 2.092 |

| Ceiling | Gyproc Wallboard | 15 | 0.19 | 0.079 |

| Pitched roof construction | ||||

| External | Concrete tiles (roofing) | 10 | 1.5 | 0.007 |

| Ventilation | Air gap | 10 | - | 0.15 |

| Underlayment | Roofing Felt | 5 | 0.19 | 0.026 |

| Internal partitions | ||||

| Surface 1 | Gypsum plasterboard | 15 | 0.19 | 0.079 |

| Air space | Air gap | 100 | - | 0.15 |

| Surface 2 | Gypsum plasterboard | 15 | 0.19 | 0.079 |

| Internal floor construction | ||||

| Floor surface | Caberdek chipboard floor | 22 | 0.13 | 0.169 |

| Sheathing | Oriented Strand Board | 15 | 0.13 | 0.115 |

| Air space | Air gap 254 mm | 254 | - | 0.230 |

| Ceiling | Gyproc wallboard | 15 | 0.19 | 0.079 |

| Ground floor construction | ||||

| Floor construction | 450 mm NUG375+75 mm Screed | 450 | 0.058 | 7.759 |

| External door construction | ||||

| Door | Painted Oak | 35 | 0.19 | 0.184 |

| Building component | U-Value (W/m2K) |

| Brick external wall U-value | 0.13 |

| Rendered external wall U-value | 0.13 |

| Loft ceiling U-value | 0.11 |

| Ground floor U-value | 0.11 |

| Windows U-value | 1.20 |

| French Door U-value | / |

| External Door U-value | 1.20 |

| Internal partition U-value | 1.89 |

| Internal floor U-value (W/m2K) | 1.16 |

| Internal door U-value (W/m2K) | 2.82 |

| Measurement | Equipment | Uncertainty |

| ASHP energy and power output | Sharkey 775 heat meter | ± 1% |

| ASHP flow rate | Sharkey 775 ultrasonic flow meter | ± 1% |

| ASHP flow and return temperature | PT-100 RTD | ± 0.3 °C |

| Internal shielded air temperature | Type-T thermocouples (calibrated to ± 0.1 °C) | ± 0.1 °C |

| Mid-room shielded air temperatures | Campbell Scientific HygroVUE10(20 to 60 °C)2 | ±0.1 °C |

| Chamber air temperatures | Campbell Scientific HygroVUE10(–40 to 70 °C)2 | ±0.2 °C |

| Element surface temperatures | Type-T thermocouples (calibrated to ± 0.1 °C) | ± 0.1 °C |

| Relative humidity | Campbell Scientific HygroVUE10 | ± 1.5% |

| Black globe temperature | Type-T thermocouple in 40 mm diameter globe | ± 0.1 °C |

| Individual zone index i | Zone | Floor area (m2) | |

| Ground Floor | 1 | Living Room | 17.17 |

| 2 | Hall | 7.81 | |

| 3 | Kitchen + Dining | 7.77+6.35 | |

| 4 | WC | 2.79 | |

| - | Store 1 | 1.68 | |

| First Floor | 5 | Bedroom 1 | 12.29 |

| 6 | Bedroom 2 | 9.86 | |

| 7 | Bedroom 3 | 7.51 | |

| 8 | Landing | 6.09 | |

| 9 | Bathroom | 3.89 | |

| 10 | En-suite | 3.19 | |

| - | Store 2 | 0.44 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).