1. Introduction

In a recent paper [

1] the concept of ghost star was introduced and studied in detail. Such a concept, inspired in early ideas by Zeldovich [

2,

3], describes fluid distributions which do not produce gravitational field outside its boundary surface (i.e. its total mass vanishes). In order to achieve the vanishing of the total mass (for a non-trivial fluid distribution) one must assume the existence of some regions within the fluid sphere endowed with negative energy-density. Some examples of this kind of fluid distribution may be found in [

1,

4,

5] (see also [

6] for more recent developments).

More recently we have studied solutions which, either correspond to the adiabatic evolution of a ghost star, or describe the evolution of fluid distributions which attain the ghost star status momentarily at some point of their lives, abandoning such state immediately afterward [

7].

However neither of the models exhibited in the references above describe solutions leading asymptotically (as ) to a ghost star.

It is the purpose of this work to present a model of an evolving fluid distribution describing the emergence of a ghost star, as the end point of its evolution.

In order to obtain our model we have initially started by imposing three conditions

Vanishing of the complexity factor [

8,

9]

Quasi-homologous evolution (QH)[

10]

The variation of the infinitesimal proper radial distance between two neighboring points per unit of proper time vanishes [

11].

The first two conditions have been shown to be useful in the description of the structure and evolution of self–gravitating fluids. The second one represents a generalization of the well known homologous evolution in Newtonian hydrodynamics [

12,

13,

14].

The third condition implies the existence of a cavity surrounding the center, and therefore appears to be a useful tool for the modeling of cosmic voids [

15,

16].

Notwithstanding, we have resorted to the above conditions for purely heuristic reasons, its physical interest being, in the context of this work, a fact of secondary relevance.

The solution obtained under the three conditions above (hereafter referred to as “primeval solution”) does not satisfy the asymptotic conditions required to obtain a static ghost star as the end point of the evolution. Accordingly we have modified this solution in order to satisfy the conditions ensuring the formation of a ghost star.

The final solution matches smoothly on the external boundary surface with the Minkowski space-time as . Instead, matching conditions are not satisfied on the boundary surface delimiting the fluid distribution from the inside (not even asymptotically), accordingly we have a thin shell on that surface.

The physical properties of the model will be analyzed in detail and the characteristics of the ghost star appearing at the end of the evolution will be discussed.

2. The General Setup of the Problem: Notation, Variables and Equations

We consider a spherically symmetric distribution of fluid, which is bounded from the outside by a spherical surface and, since we shall assume a cavity surrounding the center, the fluid is also bounded from inside by a spherical surface . The matter content consists in a locally anisotropic fluid (principal stresses unequal) undergoing dissipation in the form of heat flow (diffusion approximation).

Thus, in comoving coordinates, the general line element may be written as

where the functions

depend on

t and

r.

The energy–momentum tensor takes the form

where

is the energy density,

the radial pressure,

the tangential pressure,

the heat flux,

the four velocity of the fluid, and

a unit four vector along the radial direction. These quantities satisfy

It will be convenient to express the energy momentum tensor (

2) in the equivalent (canonical) form

with

Since we are considering comoving observers, we have

It is worth noticing that we do not add explicitly bulk or shear viscosity to the system because they can be trivially absorbed into the radial and tangential pressures, and , of the collapsing fluid (in ). Also we do not explicitly introduce dissipation in the free streaming approximation since it can be absorbed in and q.

2.1. Einstein Equations

Einstein’s field equations for the interior spacetime (

1) are given by

The non null components of (

6) with (

1) and (

2), read

where dots and primes denote derivative with respect to

t and

r respectively.

2.2. Kinematical Variables and the Mass Function

The three non-vanishing kinematical variables are the four–acceleration , the expansion scalar and the shear tensor . The corresponding expressions follow at once from their definitions.

Thus

producing

with

.

The expansion

is given by

and for the shear tensor we have

with only one non–vanishing independent component.

Using (

5) and (

14) we may write

where

2.3. The Mass Function

Next, the mass function

introduced by Misner and Sharp [

17,

18] is given by

To study the dynamical properties of the system, let us introduce, following Misner and Sharp the proper time derivative

given by

and the proper radial derivative

,

Using (

18) we can define the velocity

U of the collapsing fluid as the variation of the “areal” radius (

R) with respect to proper time, i.e.

Then (

17) can be rewritten as

From (

17) we may easily obtain

Equation (

22) may be integrated to obtain

(assuming a regular centre to the distribution, so

), or

2.4. The Junction Conditions

Outside

we have the Vaidya spacetime (or Schwarzschild in the dissipationless case), described by

where

denotes the total mass, and

v is the retarded time. The matching of the non-adiabatic sphere to the Vaidya spacetime, on the surface

constant, in the absence of thin shells (Darmois conditions [

19], see also [

20]), implies the continuity of the first and the second fundamental forms through the matching hypersurface, producing

and

In the case when a cavity forms we also have to match the solution to the Minkowski spacetime on the boundary surface delimiting the empty cavity (

). In this case the matching conditions imply

As we shall see below, in our model the Darmois conditions cannot be satisfied on

, in which case we must allow the presence of thin shells on

, implying discontinuities in the mass function [

21].

On the other hand Darmois conditions are satisfied on but only asymptotically (as ). In other words a thin shell is present on during the evolution, disappearing as the ghost star forms.

2.5. The Transport Equation

In the diffusion approximation we shall need a transport equation to evaluate the temperature and its evolution within the fluid distribution. Here we shall resort to a transport equation derived from a causal dissipative theory ( e.g. the Israel-Stewart second order phenomenological theory for dissipative fluids [

22,

23,

24]).

Thus the corresponding transport equation for the heat flux reads

where

denotes the thermal conductivity, and

T and

denote temperature and relaxation time respectively. Observe that, due to the symmetry of the problem, equation (

30) only has one independent component, which may be written as

In the case

we recover the Eckart–Landau equation [

25,

26], and in the Newtonian limit we recover the Cattaneo equation [

27,

28,

29]

For simplicity we shall consider here the so called “truncated” version where the last term in (

30) is neglected [

30],

and whose only non–vanishing independent component becomes

3. Three Conditions Leading to Our Model

As mentioned before we shall start the building up of our model by imposing three conditions on the fluid distribution, these are: the vanishing complexity factor condition, the quasi–homologous condition and a kinematical condition on the variation of the infinitesimal proper radial distance between two neighboring points per unit of proper time. In what follows we shall briefly describe these conditions.

3.1. The Vanishing Complexity Factor Condition

The complexity factor is a scalar function that has been proposed in order to measure the degree of complexity of a given fluid distribution [

8,

9].

The complexity factor is identified with the scalar function

which defines the trace–free part of the electric Riemann tensor (see [

9] for details).

It can be expressed in terms of physical variables as

or in terms of the metric functions

We shall impose the vanishing of the complexity factor in order to find an analytical solution, however as we shall see below, such a solution does not satisfy the required asymptotic behavior. In order to obtain a model with the appropriate asymptotic behavior we shall modify this primeval solution, as a consequence of which the resulting model will satisfy the vanishing complexity factor condition only asymptotically.

3.2. The Quasi-Homologous Condition

The QH condition is a generalization of the homologous condition (H) which has been assumed in [

9] to represent the simplest mode of evolution of the fluid distribution. However this last condition appears to be too stringent thereby excluding many potential interesting scenarios. Therefore in [

10] we have proposed to relax (H), and replaced it by what we called the “quasi–homologous” condition (QH).

More specifically, the H condition implies that

and

where

and

denote the areal radii of two concentric shells (

) described by

, and

, respectively.

These relationships are characteristic of the homologous evolution in Newtonian hydrodynamics [

12,

13,

14]. More so, in this latter case (

36) implies (

37). However in the relativistic case both (

36) and (

37) are in general independent, and the former implies the latter only in very special cases.

On the other hand QH only requires (

36), which using the field equations may also be written as (see [

10] for details)

As already mentioned we shall start the building up of our model by assuming that the evolution of the fluid distribution proceeds in the quasi-homologous regime (QH). Since such a condition leads to an asymptotic behavior which is incompatible with the formation of a ghost star, we should modify the primeval solution. As a consequence of this modification the final solution will not satisfy the (QH) except in the static limit , when it is trivially satisfied.

3.3. A Kinematical Restriction

In order to obtain our primeval model, besides the condition of the vanishing complexity factor and the quasi–homologous evolution, we shall impose a condition on a kinematical variable. For doing that let us first introduce another concept of velocity, different from

U, which measures the variation of the infinitesimal proper radial distance between two neighboring points (

) per unit of proper time, i.e.

. Thus, it can be shown that (see [

11,

31] for details)

or,

As an additional restriction we shall assume

, in which case

, from which a reparametrization of the coordinate

r allows us to write without loss of generality

implying

, and as it follows from (

13) and (

16)

Since the center of symmetry () does not move all along the evolution, it appears evident that any evolving fluid satisfying the condition cannot fill the central region. Therefore we shall assume the center to be surrounded by a void cavity with boundary surface , whose areal radius changes in such a way that for all fluid elements.

In the next section we shall build up a model leading to a ghost star.

4. Building up The Model

We shall now proceed to find a model giving rise to a ghost star. This will be achieved in three steps. First we shall find a primeval solution satisfying the three conditions:

, (

38) and

. In a second step we shall modify this primeval solution in order to satisfy the desired asymptotic behavior. Finally, in the third step we shall make a specific choice of some arbitrary functions and constants to fully determine the model. This final model satisfies the condition

, but conditions

and (

38) are satisfied only asymptotically.

4.1. The primeval solution

Let us start by considering a model satisfying the constraint . This model is endowed with a cavity surrounding the center, accordingly we should not worry about regularity conditions at the center.

In this case the physical variables read

and for the kinematical variables we have

Next, imposing the quasi–homologous condition, we obtain

In other words, the QH condition implies that in this case only depends on t.

On the other hand the condition

produces

Thus, the conditions of vanishing complexity factor,

and quasi–homologous evolution read

and

respectively, with

.

In order to solve the above system of equations it would be useful to introduce the intermediate variables

,

in terms of which (

50) and (

51), become

In what follows we shall impose an additional restriction to solve the above system, specifically we shall assume that

X is a separable function, i.e.

Then feeding back (

55) into (

53), and taking

t-derivative we obtain

Likewise, feeding back (

55) into (

54) and taking the

r-derivative we obtain

The combination of (

56) and (

57) produces

where

is a constant.

Then, from the integration of (

58) we have

where

is a constant of integration.

Thus, the metric functions become

where

and

are two arbitrary functions of their arguments. This a generalized version of the solution exhibited in Sec.7.2.1 in [

10].

However, functions

and

are not completely arbitrary. Indeed, taking the

t derivative of (

61) and feeding it back into (

51) we obtain

producing

where

is an arbitrary constant.

The above result implies that in the static limit (when ), , leading to in that limit.

Still worse from the above and (

61) it follows that

Thus if we want our system to be static in the limit

, we should demand

as

. But such a condition would imply because of (

60) that

as

, which of course in unacceptable.

On the other hand using (

60) and (

61), the vanishing complexity factor condition (

50) reads

implying

. However, as we shall see below, we shall need

in order to satisfy matching conditions.

In other words the metric functions (

60), (

61), obtained from the QH and the vanishing complexity factor condition are incompatible with the condition that the system tends asymptotically (as

) to a static regime. On the other hand, in the case

the QH condition implies that the shear scalar is function of

t only, and therefore in order to obtain the static asymptotic behavior,

should be function of both

t and

r.

4.2. The Asymptotic Conditions

In order to obtain the expected asymptotic behavior we shall assume the same form of metric functions (

60), (

61), but replacing

by an arbitrary function of

t (say

), such that in the limit

besides

g is not a constant.

Obviously such metric functions do not satisfy (

50) (

51) and (

65), in general (for any

t) although they do satisfy such conditions in the limit

.

From the comments above we shall assume our metric variables to read

Using these expressions in (

17) and (

42)-(

45) we find for the physical variables

4.3. The Matching Conditions

So far our model is determined up to three functions . The form of these functions will be suggested by the asymptotic conditions as and a condition to avoid shell crossing singularities ().

We are looking for a model which asymptotically (as ), approaches the state of a static ghost star .

As mentioned before, for the required asymptotic behavior of the model, we must demand that in the limit

, conditions (

66) are satisfied.

Let us now consider the matching of this model on

. We shall demand the matching conditions (

21) and (

27) to be satisfied asymptotically (as

), when a ghost star is expected to form Thus we shall demand

On the other hand, as it can be seen from (

72) and (

66), in the limit

, we obtain

as expected from the static limit, therefore we also must demand

Using (

66) in (

73), the condition

reads

To specify further our model we shall assume for the function

and the constant

where

is dimensionless constant.

Then condition (

76) becomes

On the other hand condition (

74) reads

where (

66), and

have been used. Feeding back (

77) into (

79) we obtain

which is exactly (

78). Thus the above choice of constants ensure the asymptotic fulfillment of matching conditions on

, of our fluid distribution with Minkowski space-time.

It is worth mentioning that for this choice of g and the matching condition are not satisfied on . Therefore this model has a thin shell on this surface and is a free parameter.

4.4. The Model

Finally, in order to fully describe our model we have to specify the two functions

F and

f which must satisfy the asymptotic conditions (

66).

For the sake of simplicity we choose

With the above choice, and (

77) and (

80), the metric functions

A and

R read

where

changing in the interval

, with

being a positive constant, and

changing in the interval

.

In order to ensure the positivity of A we must assume .

Using the above expressions in (

69)–(

73), the physical variables describing our model read

The temperature for this model may be calculated using (

33), (

82), and (

86), however the resulting expression is cumbersome and not very illuminating. Suffice is to say that asymptotically the temperature tends to a constant as expected from a static distribution in thermal equilibrium (as we shall see below the “thermal inertial term”

[

32] vanishes asymptotically in this model).

We shall now illustrate the formation of the ghost star as

for the model described so far. For doing that we need to evaluate the energy-density in the limit

. Using (

66), (

77) and (

80) in (

69) we obtain

where

, whose values are within the interval

.

With the choice above the expressions for

and

read

and

where

.

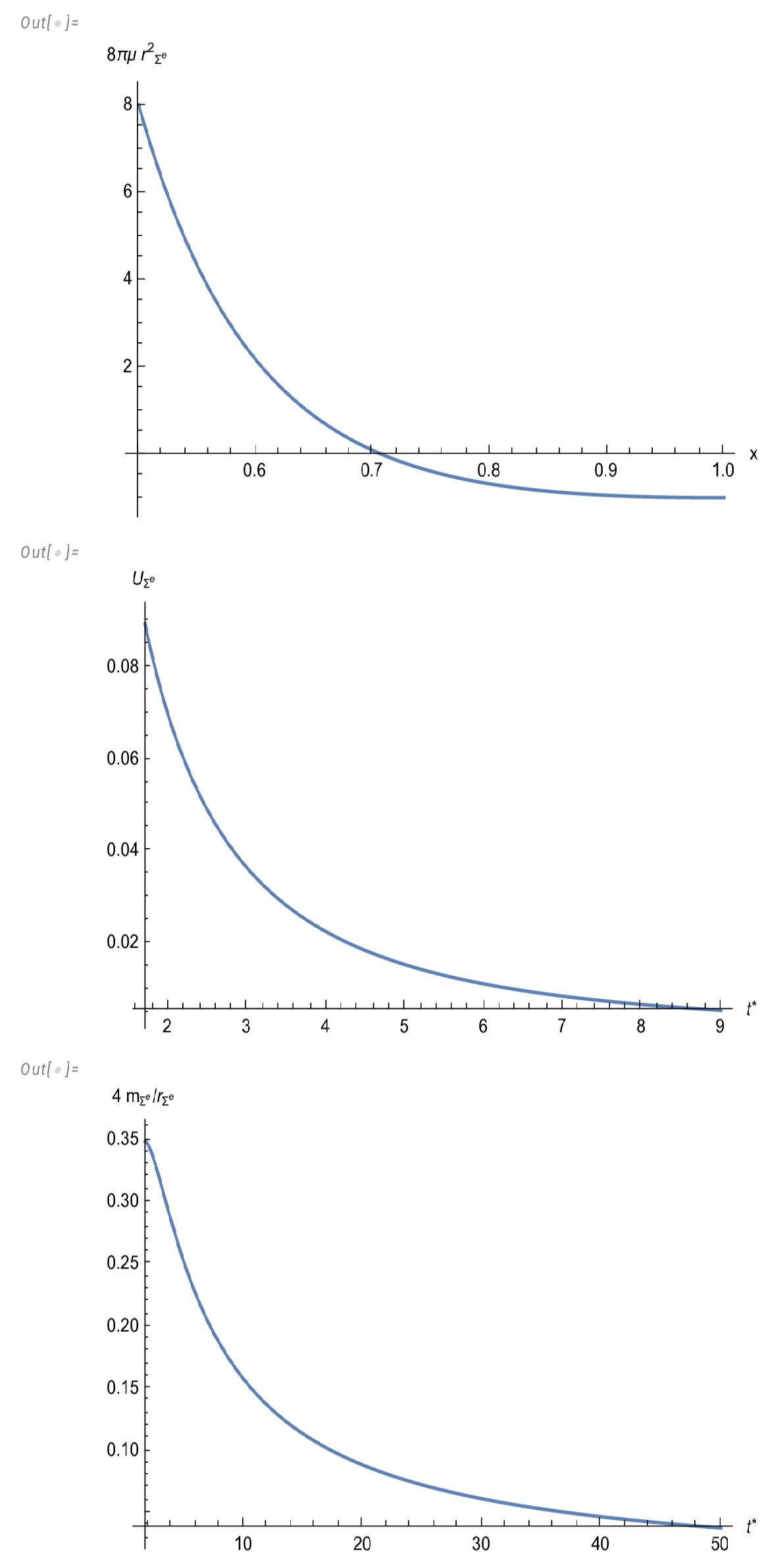

The three curves in

Figure 1 illustrate the emergence of the ghost star. The first curve depicts the radial distribution of energy-density as

, which shows a region of negative values of this variable, which ensures the vanishing of the total mass, as illustrated by the third curve. Finally the second curve shows the tendency to the static situation.

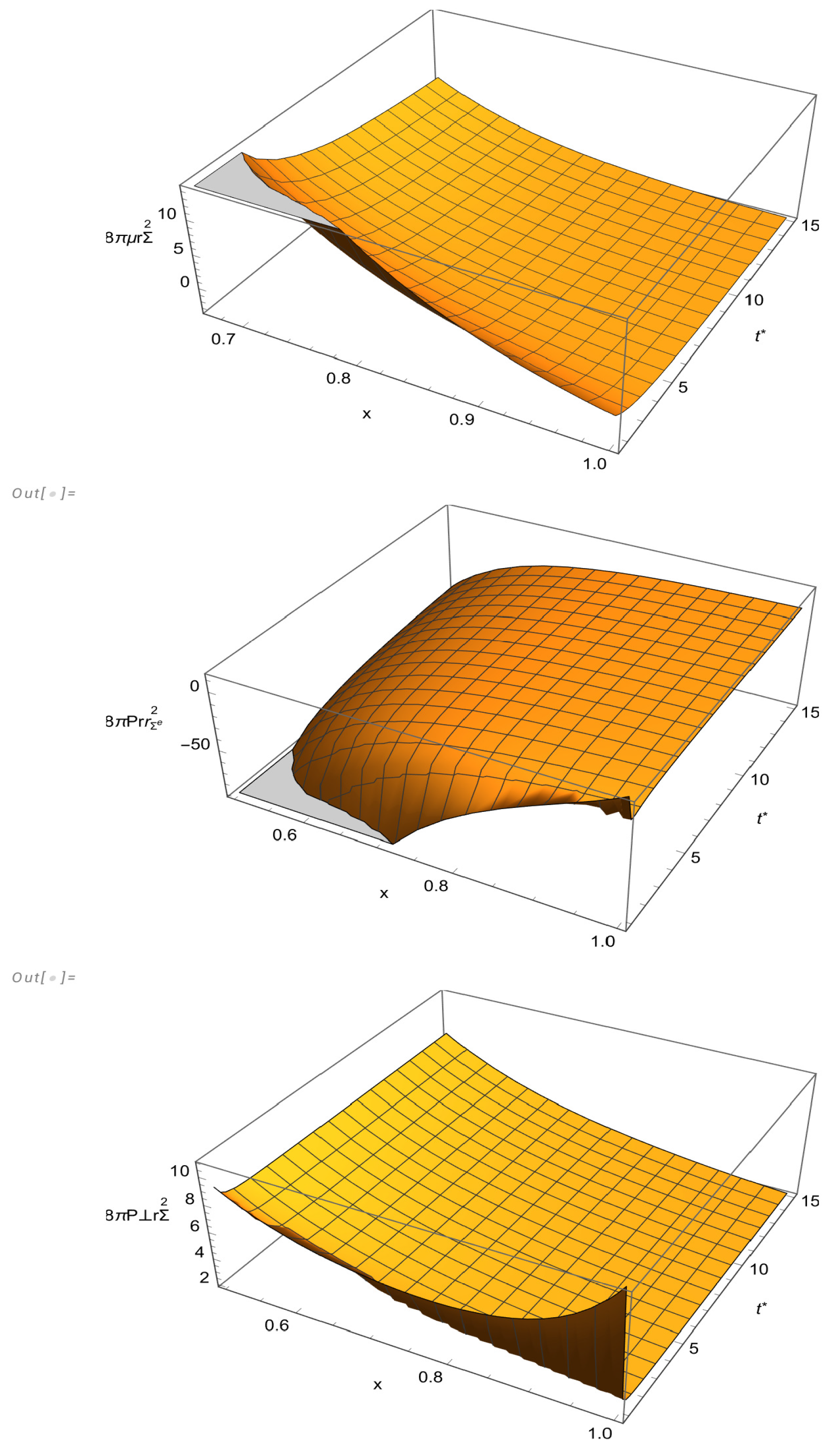

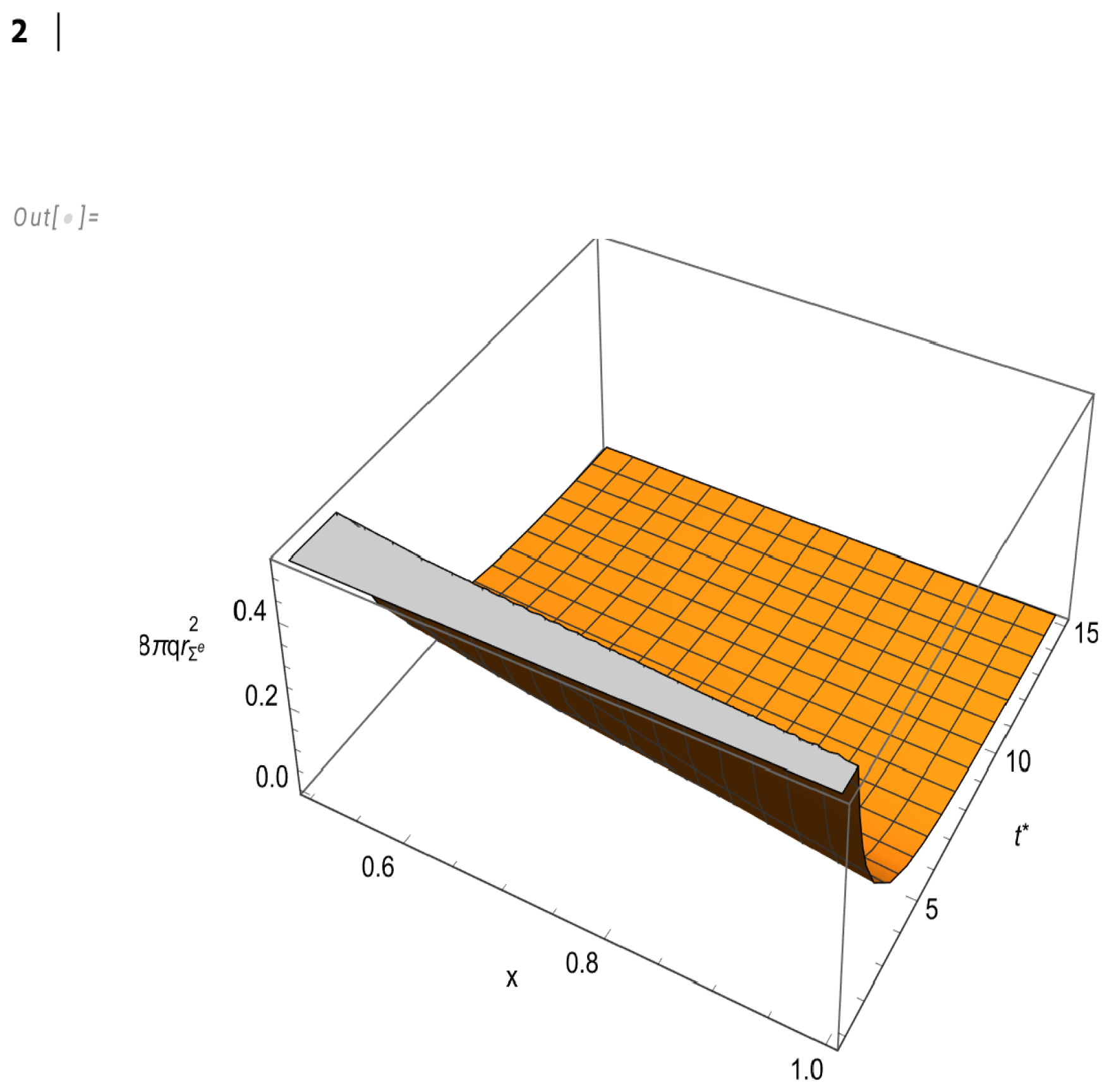

The behavior of the physical variables is depicted in

Figure 2 and

Figure 3. The graphics for

and

q have been drawn for the variables

and

x in the intervals

and

respectively. Instead, for

we have chosen the intervals

and

in order to better illustrate the appearance of the region of negative energy-density. The fast convergence of the system to the static regime is well illustrated in

Figure 3.

5. Discussion

The main purpose of this work has been to exhibit the viability of the formation of a ghost star as the end point of the evolution of a self–gravitating fluid distribution. To achieve this goal we have presented an analytical model of a dissipative spherically symmetric fluid distribution evolving toward a ghost star.

We have initially found a primeval solution satisfying the vanishing complexity factor condition, the quasi–homologous evolution and

. This primeval solution was next modified to satisfy the required asymptotic conditions (

66). Finally we have chosen the remaining arbitrary functions to fully specify our model. This final model represents and expanding fluid distribution endowed with a cavity surrounding the center, tending to a static configuration. The endpoint of the evolution of this model is a ghost star as illustrated by

Figure 1.

Furthermore, in the limit

we have

, implying, because of (

12), the vanishing of the four-acceleration of the fluid forming the ghost star (which explains the vanishing of the “thermal inertial term” mentioned before). This implies in its turn, according to (

A1), that the gravitational term in the dynamic equation (

A2) (the Tolman mass [

33]) vanishes, and the equilibrium is reached by the balance between the radial pressure gradient and the anisotropic factor. A particular model of a ghost star with vanishing complexity factor and vanishing Tolman mass has been considered in [

1].

The model satisfies asymptotically Darmois conditions on the external boundary surface, whereas on the inner boundary surface such conditions are not satisfied indicating thereby the appearance of shells on this hypersurface. The presence of these thin shells are likely to be produced by the simplicity of the model. More involved analytical models, or numerical models could avoid these “drawbacks”.

We should recall that the very existence of ghost stars relies on the assumption of the existence of regions of the fluid distribution endowed with negative energy-density. In this respect it should be mentioned that negative energy-density (or negative mass) is a subject extensively considered in the literature (see [

34,

35,

36,

37,

38,

39,

40,

41,

42,

43,

44,

45,

46,

47,

48,

49] and references therein). Particularly relevant are those references relating the appearance of negative energy-density with quantum effects.

It is worth mentioning the relevance of the observational aspects of the ghost stars, in general and of our model in particular. On the one hand it is evident that the shadow of such kind of object should differ from the one produced by a self-gravitating star with non-vanishing total mass. In the particular case of the model here considered one should be able to detect the variation of the shadow as the system approaches the state of ghost star. We ignore if the ongoing observations of this kind [

50,

51,

52,

53] are able to do that, but this is an important issue to consider. A research endeavor pointing in a similar direction has been recently published in [

54].

On the other hand, it is worth noticing that ghost stars are a sort of reservoirs of dark mass produced by the appearance of negative energy-density is some regions of the fluid distribution. It remain to be seen if the general problem of dark matter could be, at least partially, be explained in terms of ghost stars [

55].

We would also like to mention that an important piece of theoretical evidence behind the concept of ghost star is still missing. We have in mind a microscopic theory accounting for the appearance of negative energy-density. Research in this direction could provide further support to the astrophysical relevance of ghost stars.

Finally, let us mention two natural extensions of the work here presented

Our solution was based on a set of heuristic conditions mentioned above. Alternatively, solutions of this kind might be found by using the general methods presented in [

56,

57,

58,

59].

We have resorted to GR to describe the gravitational interaction. It would be interesting to consider the same problem within the context of one of the extended gravitational theories [

60].

Author Contributions

All authors contributed equally to this work. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript. Conceptualization, L.H.; methodology, L.H., A.D.P.; J.O. ; software, J. O.; formal analysis, L.H., A.D. P.; J. O.; writing—original draft preparation, L. H. writing—review and editing, L. H:; A.D. P.; J. O.; funding acquisition, L. H.; J.O.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was partially supported by the Grant PID2021-122938NB-I00 funded by MCIN/AEI/ 10.13039/501100011033 and by ERDF A way of making Europe, as well as the Consejería de Educación of the Junta de Castilla y León under the Research Project Grupo de Excelencia Ref.:SA097P24 (Fondos Feder y en línea con objetivos RIS3).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to publish the results.

Appendix A Dynamical Equation

Using (

12), (

17), (

20) and (

70) it can be easily obtained

which allows to write the dynamical equation following from the Bianchi identities as (see [

9] for details)

References

- Herrera, L.; Di Prisco, A.; Ospino, J. Ghost stars in general relativity. Symmetry 2024, 16, 562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeldovich, Ya.B.; Novikov, I.D. Relativistic Astrophysics. Vol I. Stars and Relativity; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, Illinois. USA, 1971. [Google Scholar]

- Zeldovich, Ya.B. The Collapse of a Small Mass in the General Theory of Relativity. Sov. Phys. JETP 1962, 15, 446. [Google Scholar]

- Herrera,L. ; Ponce de Leon, J. Confined gravitational fields produced by anisotropic spheres. J. Math. Phys. 1985, 26, 2847–2849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrera, L.; Di Prisco, A.; Ospino, J. Non-static fluid spheres admitting a conformal Killing vector: Exact solutions. Universe 2022, 8, 296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naseer, T.; Hassan, K.; Sharif, M. Possible existence of ghost stars in the context of electromagnetic field. Chin. J. P. 2025, 94, 594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrera, L.; Di Prisco, A.; Ospino, J. Evolution of Self-Gravitating Fluid Spheres Involving Ghost Stars. Symmetry 2024, 16, 1422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrera, L. New definition of complexity for self–gravitating fluid distributions: The spherically symmetric static case. Phys. Rev. D 2018, 97, 044010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrera, L.; Di Prisco, A.; Ospino, J. Definition of complexity for dynamical spherically symmetric dissipative self–gravitating fluid distributions. Phys. Rev. D 2018, 98, 104059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrera, L.; Di Prisco, A.; Ospino, J. Quasi–homologous evolution of self–gravitating systems with vanishing complexity factor. Eur. Phys. J. C 2020, 80, 631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- L. Herrera, G. L. Herrera, G. Le Denmat and N.O. Santos. Cavity evolution in relativistic self–gravitating fluids. Class. Quantum Grav. 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Schwarzschild, M. Structure and Evolution of the Stars; Dover: New York, NY, USA, 1958. [Google Scholar]

- Hansen, C.; Kawaler, S. Stellar Interiors: Physical Principles, Structure and Evolution; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Kippenhahn, R.; Weigert, A. Stellar Structure and Evolution; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Liddle, A. R.; Wands, D. Microwave background constraints on extended inflation voids. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 1991, 253, 637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peebles, P. J. E. The Void Phenomenon. Astrophys. J. 2001, 557, 445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Misner, C.; Sharp, D. Relativistic Equations for Adiabatic, Spherically Symmetric Gravitational Collapse. Phys. Rev. 1964, 136, B571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cahill, M.; McVittie, G. Spherical Symmetry and Mass-Energy in General Relativity. I. General Theory. J. Math. Phys. 1970, 11, 1382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darmois, G. Memorial des Sciences Mathematiques; Gauthier-Villars: Paris, France, (1927); p. 25.

- Chan, R. Collapse of a radiating star with shear. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 1997, 288, 589–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Israel,W. Singular hypersurfaces and thin shells in general relativity. Il Nuovo Cimento B 1966, 10, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Israel, W. Nonstationary irreversible thermodynamic: A causal relativistic theory. Ann. Phys. (NY) 1976, 100, 310–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Israel, W.; Stewart, J. Thermodynamic of nonstationary and transient effects in a relativistic gas. Phys. Lett. A 1976, 58, 213–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Israel, W.; Stewart, J. Transient relativistic thermodynamics and kinetic theory. Ann. Phys. (NY) 1979, 118, 341–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eckart, C. The Thermodynamics of Irreversible Processes. III. Relativistic Theory of the Simple Fluid. Phys. Rev. 1940, 58, 919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landau, L.; Lifshitz, E. Fluid Mechanics, Pergamon Press: London, U. K. 1959.

- Cattaneo, C. Sulla conduzione del calore. Atti Sem. Mat. Fiz. Univ. Modena 1948, 3, 83–101. [Google Scholar]

- Cattaneo, C. Sur une forme de l’equation de la chaleur eliminant le paradoxe d’une propagation instantanee. Compt. R. Acad. Sci. Paris 1958, 247, 431–433. [Google Scholar]

- Vernotte, P. Les paradoxes de la theorie continue de l’equation de la chaleur. Compt. R. Acad. Sci. Paris 1958, 246, 3154–3155. [Google Scholar]

- Triginer, J.; Pavon, D. On the thermodynamics of tilted and collisionless gases in Friedmann–Robertson–Walker spacetimes. Class. Quantum Grav. 1995, 12, 199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M. K. ( 1985.

- Tolman, R. On the weight of heat and thermal equilibrium in general relativity. Phys. Rev 1930, 35, 904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tolman, R. On the use of the energy-momentum principle in general relativity. Phys. Rev 1930, 35, 875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bondi, H. Negative Mass in General Relativity. Rev. Mod. Phys. 1957, 29, 423–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooperstock, F.I.; Rosen, N. A nonlinear gauge-invariant field theory of leptons. Int. J. Theor. Phys. 1989, 28, 423–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonnor, W.B.; Cooperstock, F.I. Does the electron contain negative mass? Phys. Lett. A. 1989, 139, 442–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papapetrou, A. Lectures on General Relativity; D. Reidel, Dordrecht-Holland: Boston. USA, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Herrera, L.; Varela, V. Negative energy density and classical electron models. Physics Letters A, 1994, 189, 11–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Najera, S.; Gamboa, A.; Aguilar-Nieto, A.; Escamilla-Rivera, C. On Negative Mass Cosmology in General Relativity. arXiv: 2105.110041v1, arXiv:2105.110041v1 2021.

- Farnes, J.S. A unifying theory of dark energy and dark matter: Negative masses and matter creation within a modified λ cdm framework. Astron. Astrophys. 2018, 620, A92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maciel, A.; Delliou, M.L.; Mimoso, J.P. New perspectives on the TOV equilibrium from a dual null approach. Class. Quantum Gravity 2020, 37, 125005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrera, L. Nonstatic hyperbolically symmetric fluids. Int. J. Mod. Phys. D 2022, 31, 2240001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capozziello, S.; Lobo, F.S.N.; Mimoso, J.P. Energy conditions in modified gravity. Phys. Lett. B 2014, 730, 280–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capozziello, S.; Lobo, F.S.N.; Mimoso, J.P. Generalized energy conditions in extended theories of gravity. Phys. Rev. D 2015, 91, 124019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barcelo, C.; Visser, M. Twilight for the Energy Conditions? Int. J. Mod. Phys. D 2002, 11, 1553–1560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kontou, E.A.; Sanders, K. Energy conditions in general relativity and quantum field theory. Class. Quantum Gravity 2020, 37, 193001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavsic, M. On negative energies, strings, branes, and braneworlds: A review of novel approaches. Int. J. Mod. Phys. A 2020, 35, 2030020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen-Hao Hao etal. Emergence of negative mass in general relativity. Eur. Phys. J. C 2024, 84, 878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bormashenko, E. The effect of negative mass in gravitating systems. Pramana J. P. 2023, 97, 199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akiyama, K. et al. (Event Horizon Telescope Collaboration). First M87 Event Horizon Telescope Results. I. The Shadow of the Supermassive Black Hole. Astrophys. J. Lett. 2019, 875, L1. [Google Scholar]

- Akiyama, K. et al. (Event Horizon Telescope Collaboration). First Sagittarius A Event Horizon Telescope Results. I. The Shadow of the Supermassive Black Hole in the Center of the Milky Way. Astrophys. J. Lett. 2022, 930, L12. [Google Scholar]

- Psaltis, D. Testing general relativity with the Event Horizon Telescope. Gen. Relativ. Gravit. 2019, 51, 137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gralla, S. E. Can the EHT M87 results be used to test general relativity? Phys. Rev. D 2021, 103, 024023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nalui, S.; Bhattacharya, S. Herrera complexity and shadows of spherically symmetric compact objects. Phys. Lettt. B 2025, 861, 139261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Croon, D.; Sevillano Munoz. , S. Repository for extended dark matter object constraints. Eur.Phys J. C 2025, 85, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thirukkanesh, S; Maharaj, S. D. Radiating relativistic matter in geodesic motion. J. Math. Phys. 2009, 50, 022502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thirukkanesh, S.; Maharaj, S. D. Mixed potentials in radiative stellar collapse. J. Math. Phys. 2010, 51, 072502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanov, B. All solutions for geodesic anisotropic spherical collapse with shear and heat radiation. Astrophys. Space Sci. 2016, 361, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanov, B. A different approach to anisotropic spherical collapse with shear and heat radiation. Int. J. Mod. Phys. D 2016, 25, 1650049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capozziello, S.; Laurentis, M.D. Extended theories of gravity. Phys. Rep. 2011, 509, 167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).