Submitted:

19 March 2025

Posted:

20 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Foundations

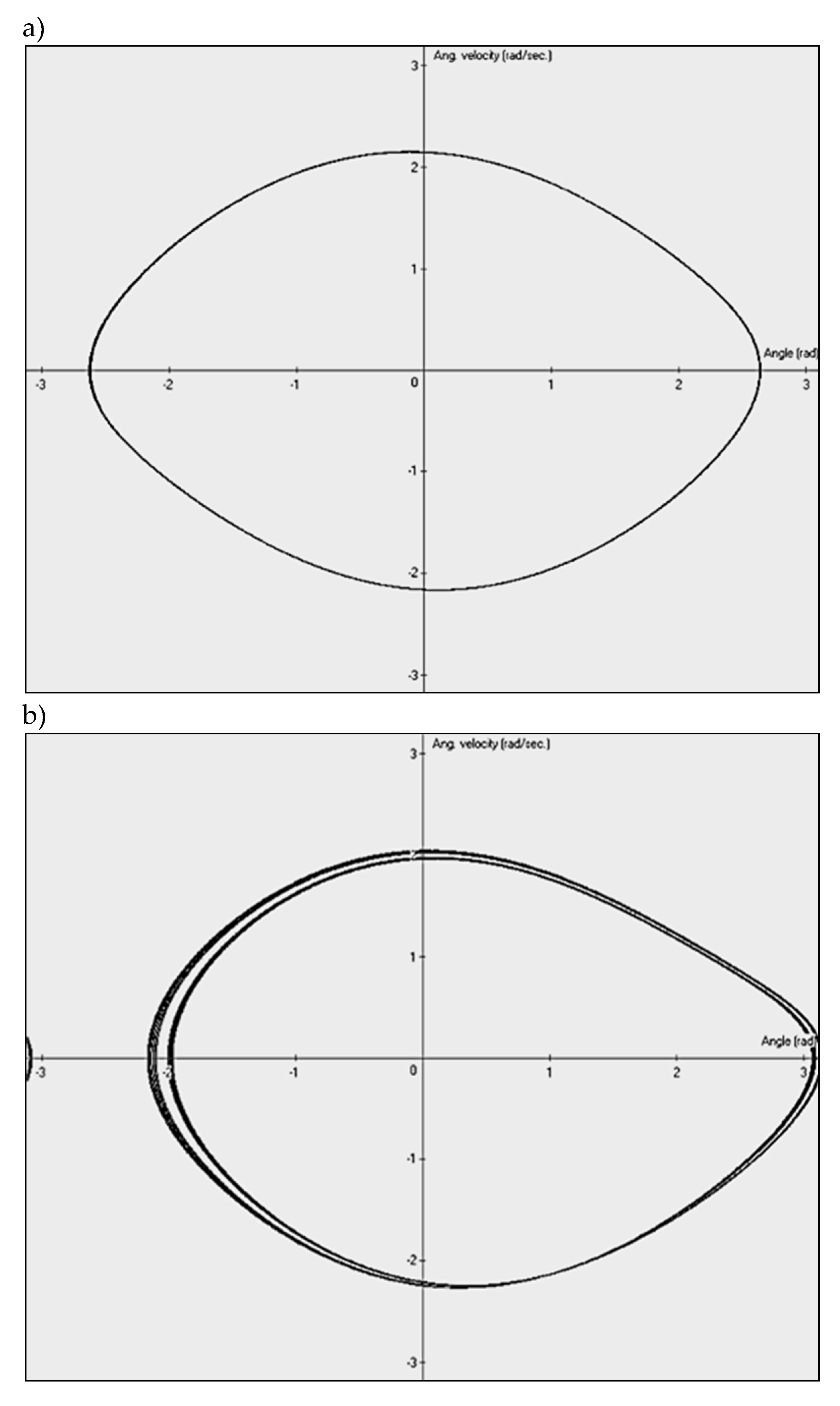

2.1. Deterministic Chaos as Example of Complex Behavior of Mechanical Systems

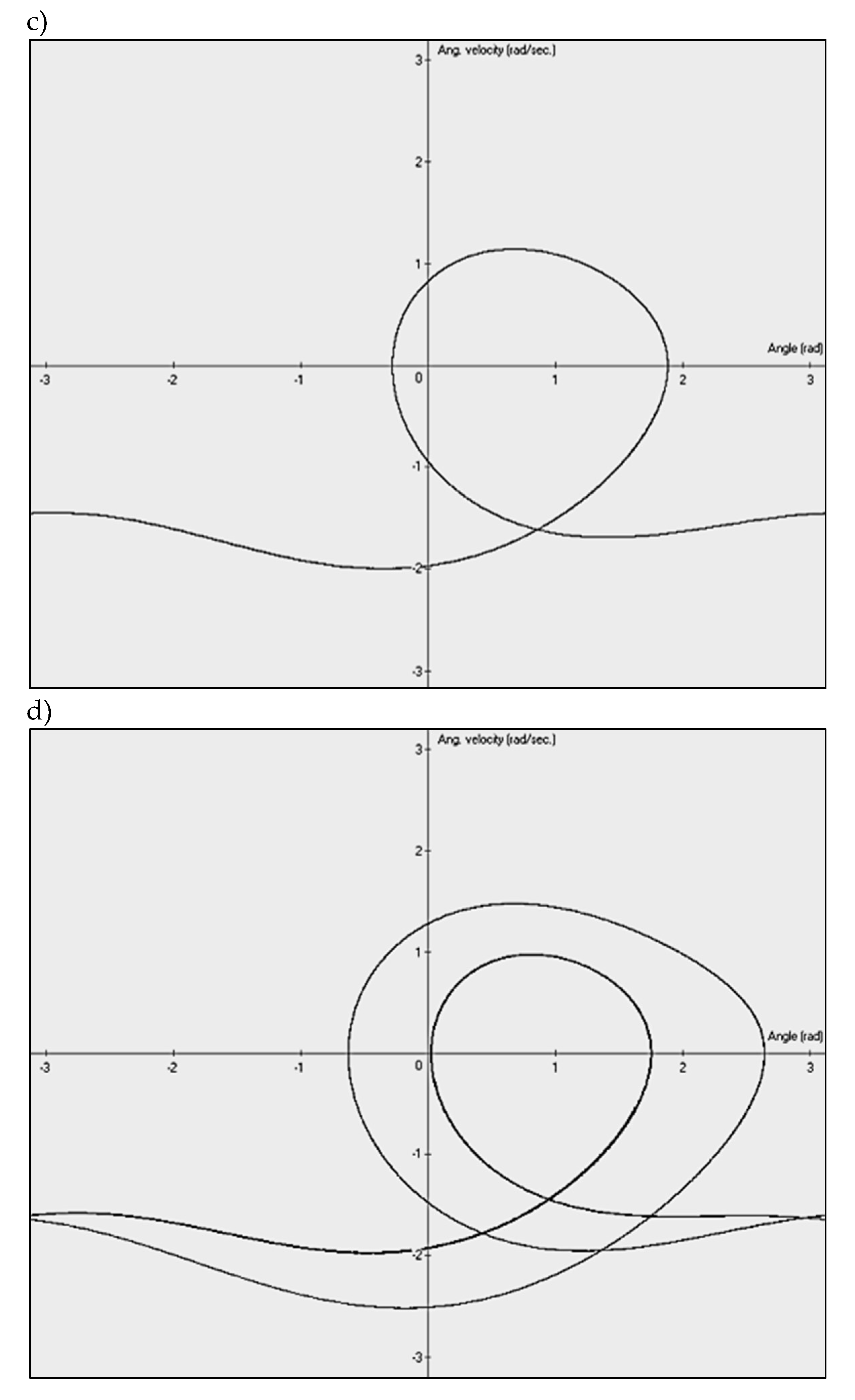

2.2. The Concept of Time-Shifted Mapping (TSM)

3. Experiment and Analysis of Data

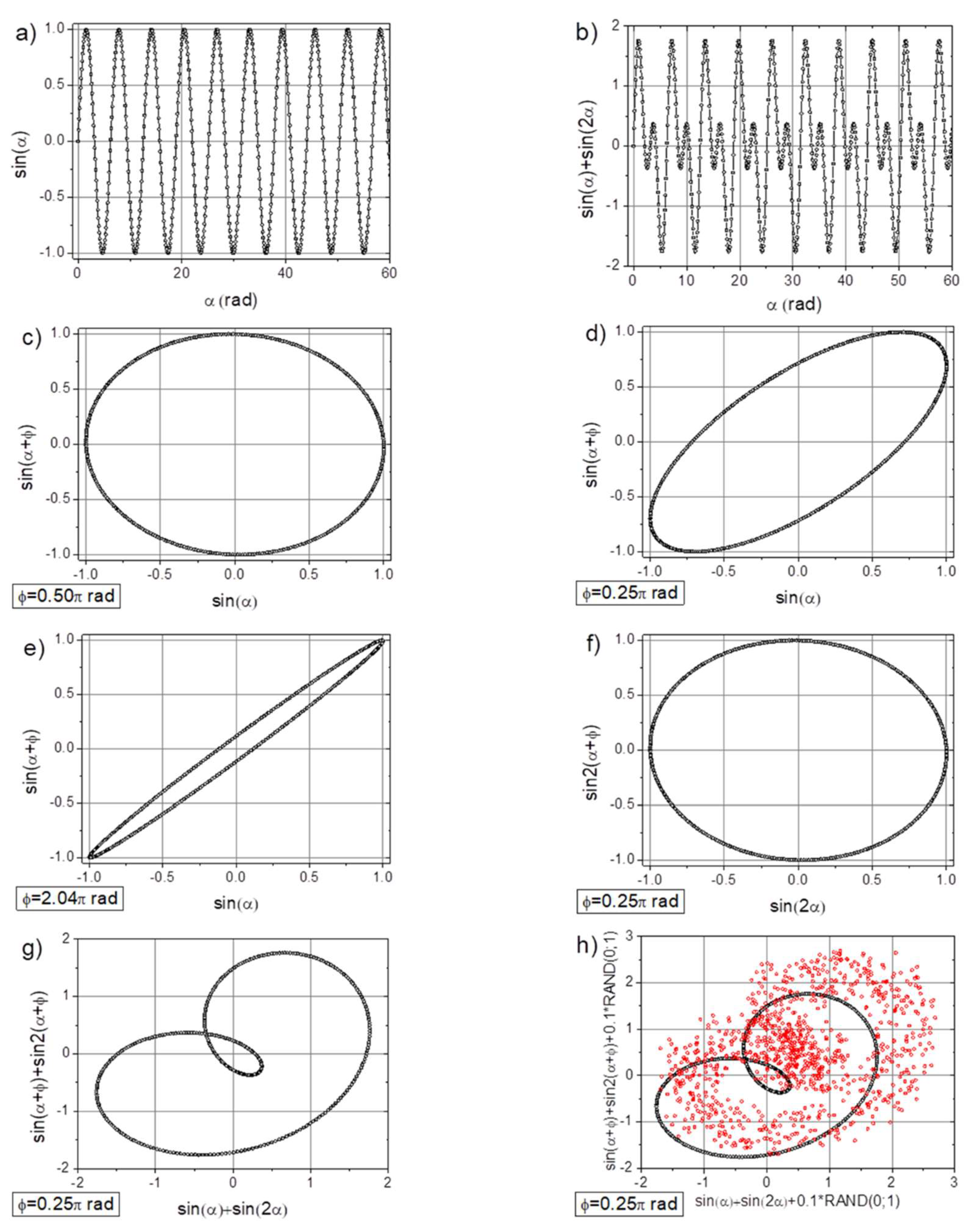

3.1. Experimental Data Analysis

4. Discussion and Conclusions

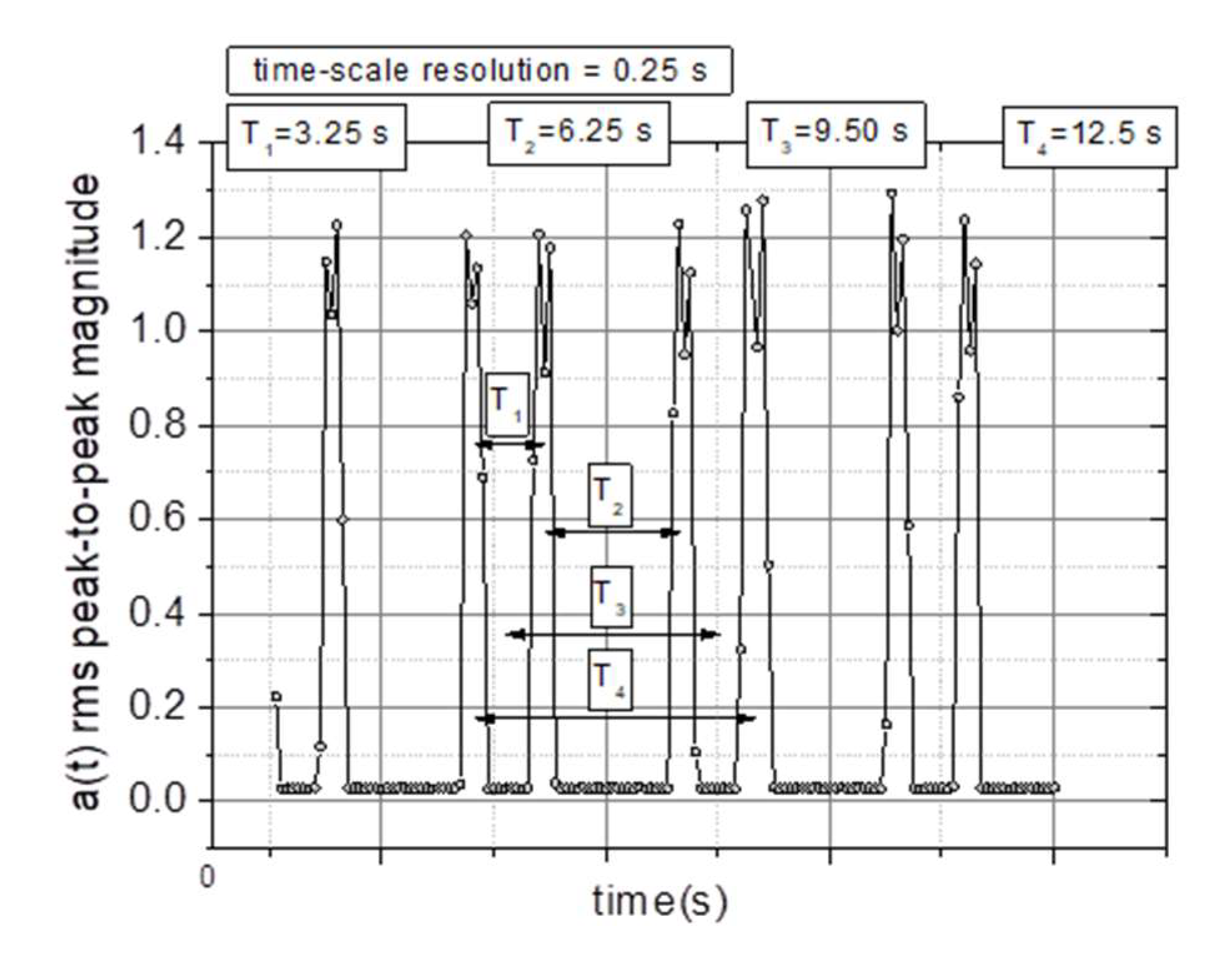

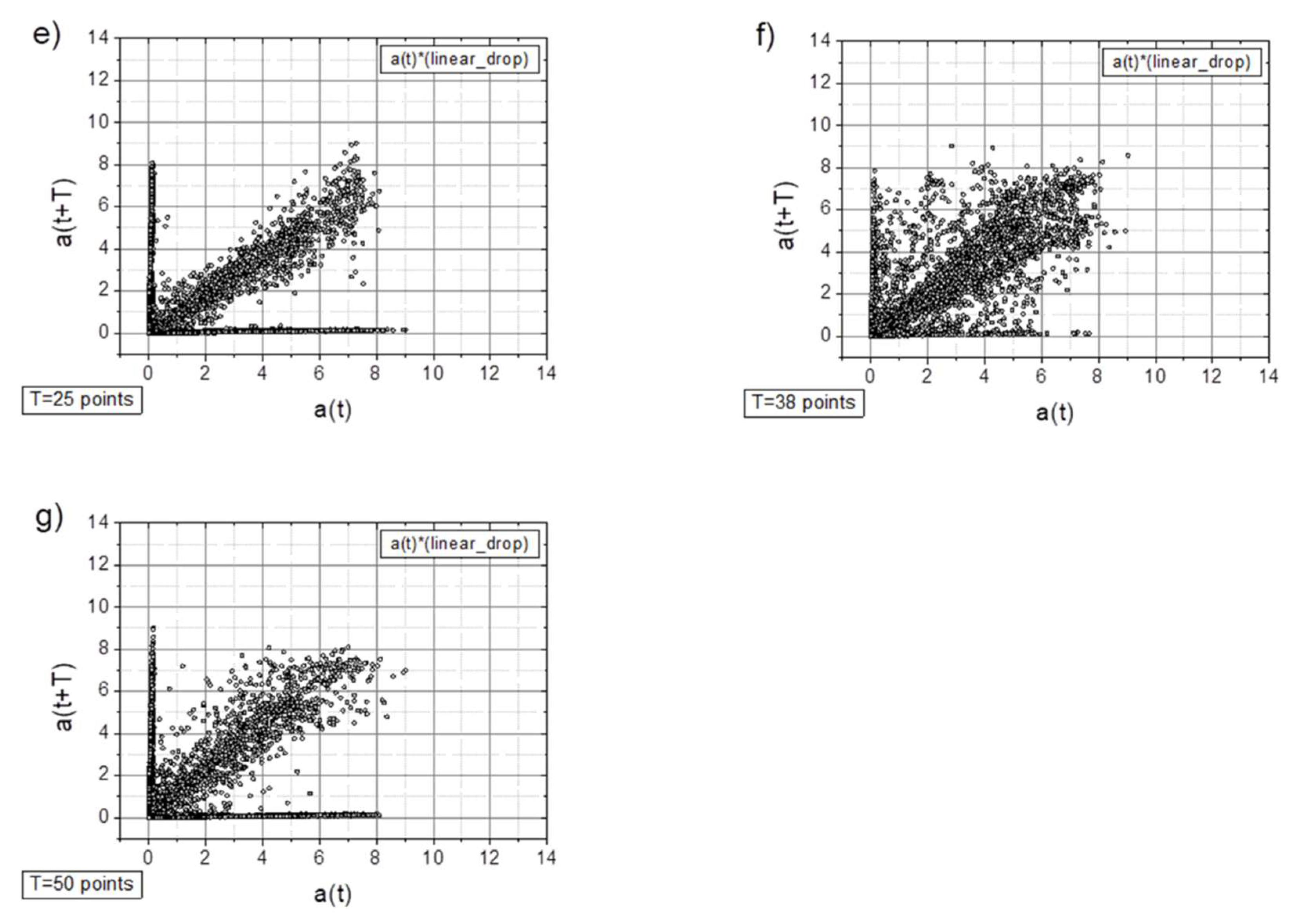

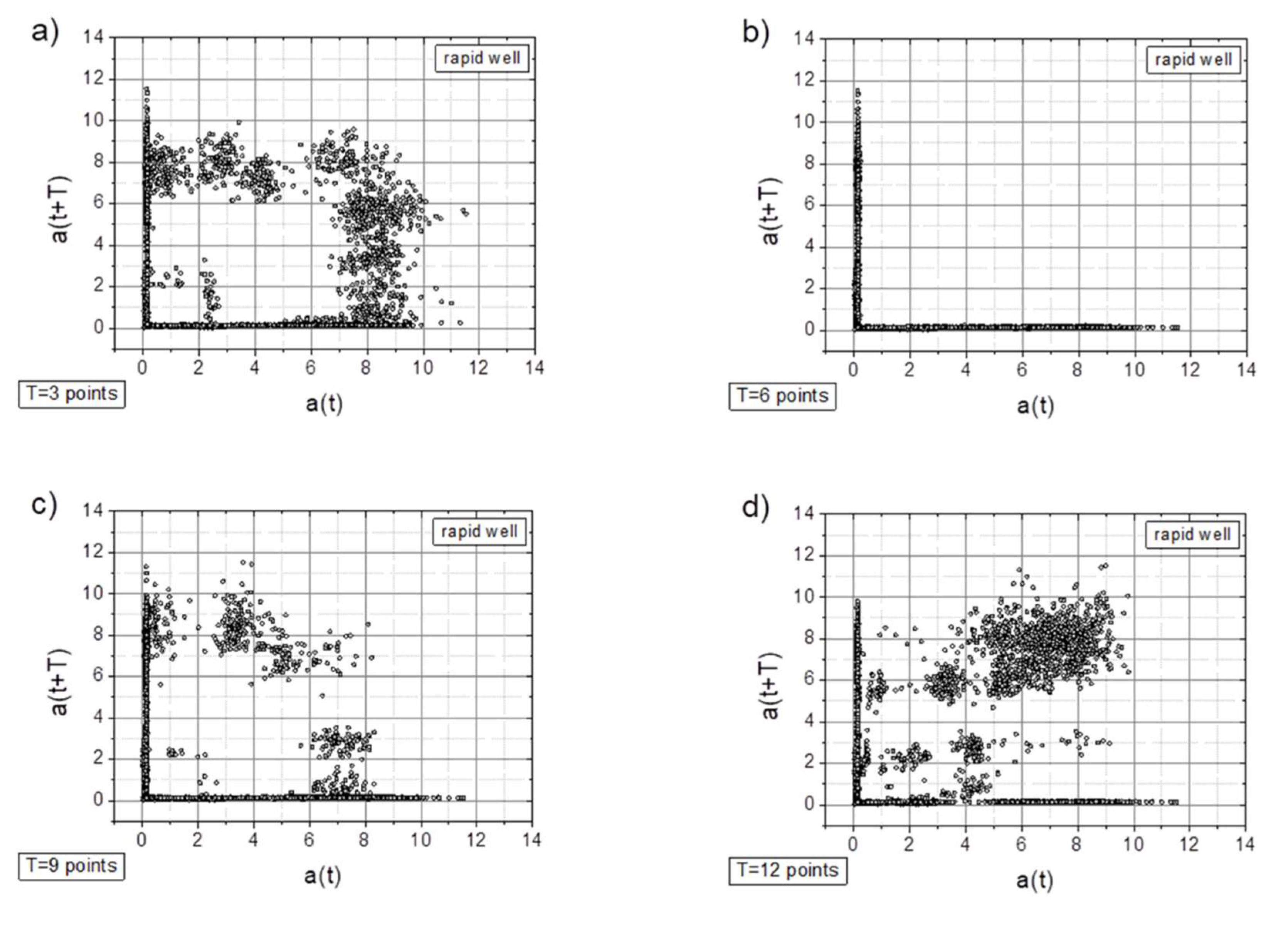

- In general, all charts, except those with a time shift of T=6 points, proved to be effective for analyzing the registered signals.

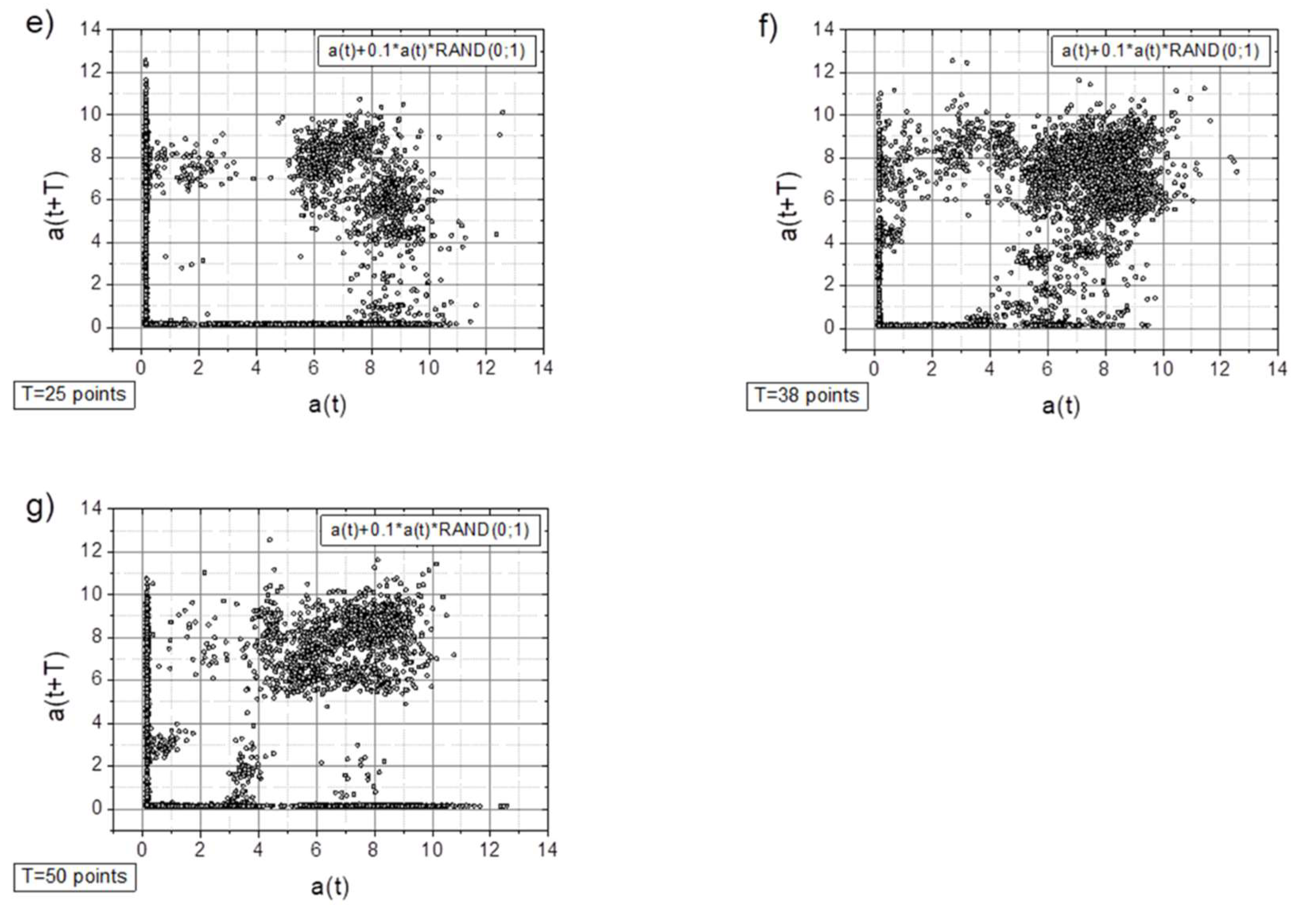

- Adding a random factor to the signal disrupts its periodicity: on a map with a time shift of T=9 points (cf. Figure 7a and 7c), the map completely changes its character.

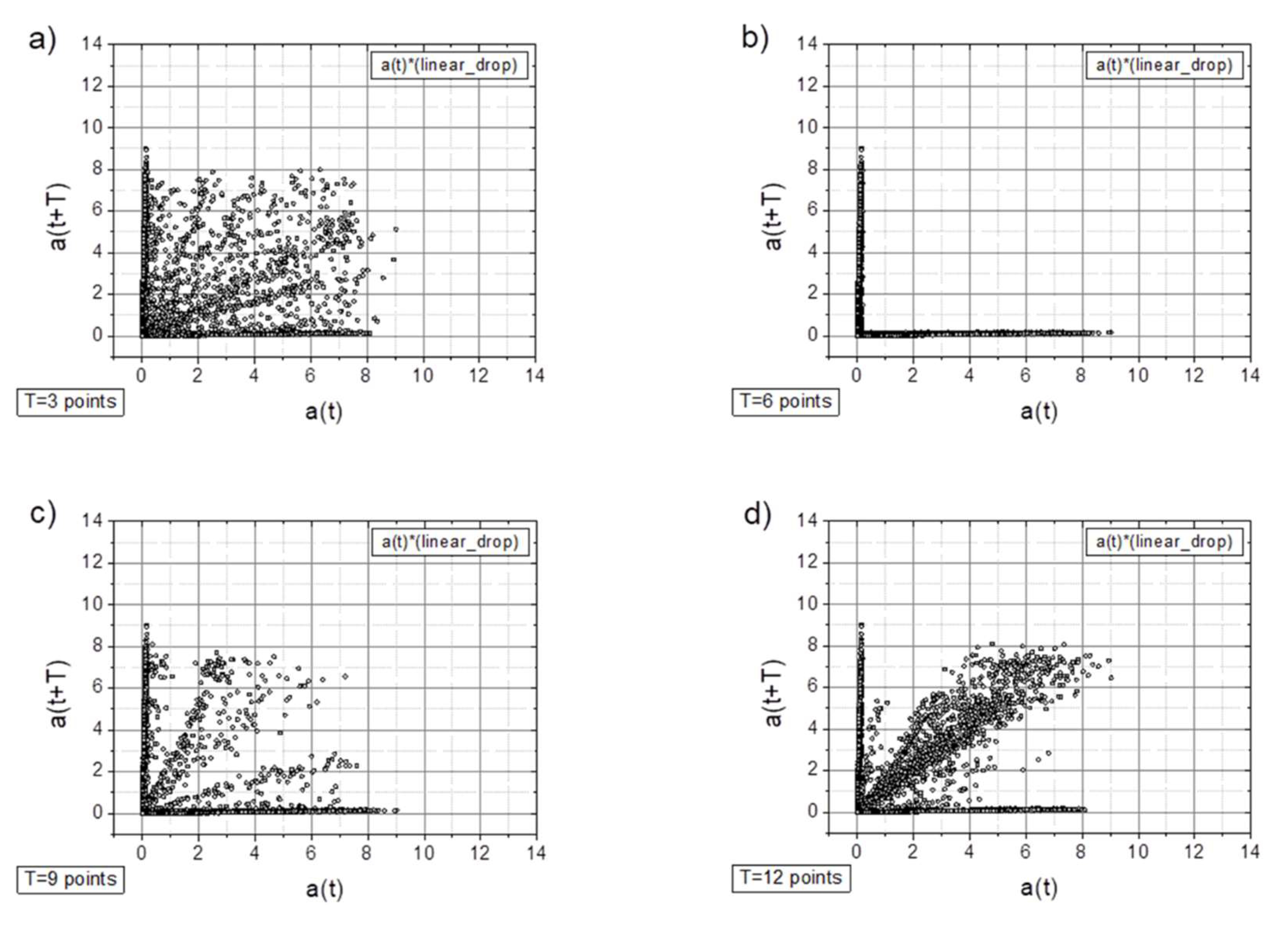

- The linear decay of the signal results in the appearance of new collinear sets of points on the chart (e.g., Figure 8c).

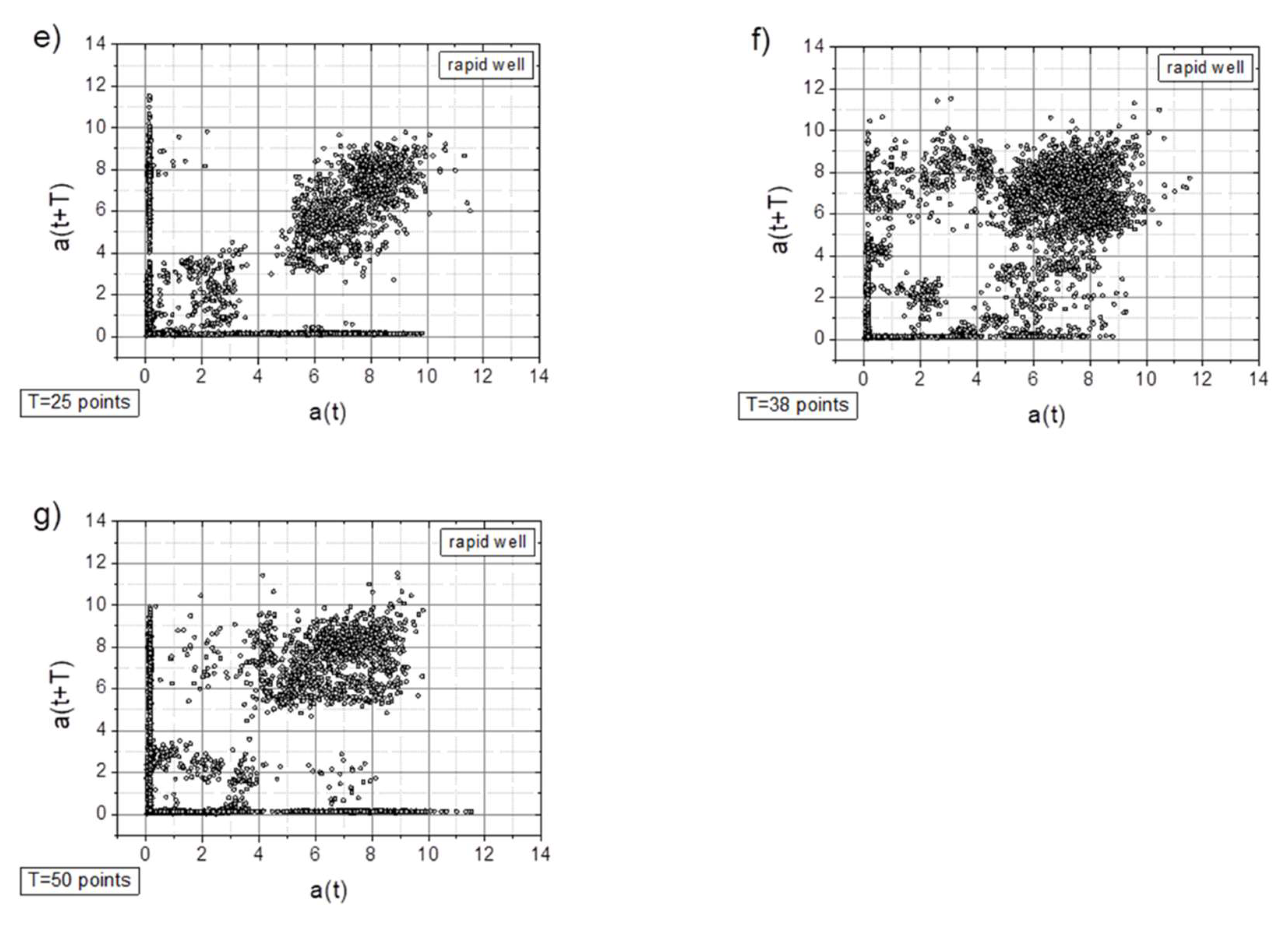

- Along with the observed periodicities, areas of high randomness are clearly visible—cf. maps for T=25 points, particularly for accelerations exceeding 5g (depending on the signal type).

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ding, H.; Tian, J.; Yu, W.; Wilson, D.I.; Young, B.R.; Cui, X.; Xin, X.; Wang, Z.; Li, W. The Application of Artificial Intelligence and Big Data in the Food Industry. Foods 2023, 12, 4511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorger, M.; Ralph, B.J.; Hartl, K.; Woschank, M.; Stockinger, M. Big Data in the Metal Processing Value Chain: A Systematic Digitalization Approach under Special Consideration of Standardization and SMEs. Applied Sciences 2021, 11, 9021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurnia Putri, R.; Athoillah, M. Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning in Digital Transformation: Exploring the Role of AI and ML in Reshaping Businesses and Information Systems. In Advances in Digital Transformation - Rise of Ultra-Smart Fully Automated Cyberspace; IntechOpen, 2024.

- Raska, P.; Ulrych, Z.; Malaga, M. Data Reduction of Digital Twin Simulation Experiments Using Different Optimisation Methods. Applied Sciences 2021, 11, 7315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Abassi, A.; Karimipour, H.; HaddadPajouh, H.; Dehghantanha, A.; Parizi, R.M. Industrial Big Data Analytics: Challenges and Opportunities. In Handbook of Big Data Privacy; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2020; pp. 37–61. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.; Zhang, W.; Shi, Y.; Duan, S.; Liu, J. Industrial Big Data Analytics: Challenges, Methodologies, and Applications. 2018.

- Panza, M.A.; Pota, M.; Esposito, M. Anomaly Detection Methods for Industrial Applications: A Comparative Study. Electronics (Basel) 2023, 12, 3971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grunova, D.; Bakratsi, V.; Vrochidou, E.; Papakostas, G.A. Machine Learning for Anomaly Detection in Industrial Environments. In Proceedings of the EEPES 2024; MDPI: Basel Switzerland, August 7, 2024; p. 25. [Google Scholar]

- Serradilla, O.; Zugasti, E.; Ramirez de Okariz, J.; Rodriguez, J.; Zurutuza, U. Adaptable and Explainable Predictive Maintenance: Semi-Supervised Deep Learning for Anomaly Detection and Diagnosis in Press Machine Data. Applied Sciences 2021, 11, 7376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, A.; Dasgupta, A. Supervised and Unsupervised Machine Learning Algorithms for Forecasting the Fracture Location in Dissimilar Friction-Stir-Welded Joints. Forecasting 2022, 4, 787–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, B.; Wang, X. Industrial Image Anomaly Detection via Self-Supervised Learning with Feature Enhancement Assistance. Applied Sciences 2024, 14, 7301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kannan, S.; Gambetta, N. Technology-Driven Sustainability in Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises: A Systematic Literature Review. Journal of Small Business Strategy 2025, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rupeika-Apoga, R.; Petrovska, K. Barriers to Sustainable Digital Transformation in Micro-, Small-, and Medium-Sized Enterprises. Sustainability 2022, 14, 13558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz-Arancibia, J.; Hochstetter-Diez, J.; Bustamante-Mora, A.; Sepúlveda-Cuevas, S.; Albayay, I.; Arango-López, J. Navigating Digital Transformation and Technology Adoption: A Literature Review from Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises in Developing Countries. Sustainability 2024, 16, 5946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theodorakopoulos, L.; Theodoropoulou, A.; Stamatiou, Y. A State-of-the-Art Review in Big Data Management Engineering: Real-Life Case Studies, Challenges, and Future Research Directions. Eng 2024, 5, 1266–1297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andronie, M.; Lăzăroiu, G.; Iatagan, M.; Hurloiu, I.; Ștefănescu, R.; Dijmărescu, A.; Dijmărescu, I. Big Data Management Algorithms, Deep Learning-Based Object Detection Technologies, and Geospatial Simulation and Sensor Fusion Tools in the Internet of Robotic Things. ISPRS Int J Geoinf 2023, 12, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andronie, M.; Lăzăroiu, G.; Karabolevski, O.L.; Ștefănescu, R.; Hurloiu, I.; Dijmărescu, A.; Dijmărescu, I. Remote Big Data Management Tools, Sensing and Computing Technologies, and Visual Perception and Environment Mapping Algorithms in the Internet of Robotic Things. Electronics (Basel) 2022, 12, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Q.; Zhao, Q. Recent Advances in Robotics and Intelligent Robots Applications. Applied Sciences 2024, 14, 4279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zabala-Vargas, S.; Jaimes-Quintanilla, M.; Jimenez-Barrera, M.H. Big Data, Data Science, and Artificial Intelligence for Project Management in the Architecture, Engineering, and Construction Industry: A Systematic Review. Buildings 2023, 13, 2944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Licardo, J.T.; Domjan, M.; Orehovački, T. Intelligent Robotics—A Systematic Review of Emerging Technologies and Trends. Electronics (Basel) 2024, 13, 542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skėrė, S.; Žvironienė, A.; Juzėnas, K.; Petraitienė, S. Decision Support Method for Dynamic Production Planning. Machines 2022, 10, 994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosin, F.; Forget, P.; Lamouri, S.; Pellerin, R. Enhancing the Decision-Making Process through Industry 4.0 Technologies. Sustainability 2022, 14, 461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaworski, M.; Borowski, P.F.; Kozioł, Ł. Supporting Decision-Making in the Technical Equipment Selection Process by the Method of Contradictory Evaluations. Sustainability 2022, 14, 7911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.-F.; Wang, S.-Y.; Tung, H.-H. A Comprehensive Decision-Making Approach for Strategic Product Module Planning in Mass Customization. Mathematics 2024, 12, 1745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulewicz, R.; Siwiec, D.; Pacana, A. A New Model of Pro-Quality Decision Making in Terms of Products’ Improvement Considering Customer Requirements. Energies (Basel) 2023, 16, 4378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krajčovič, M.; Bastiuchenko, V.; Furmannová, B.; Botka, M.; Komačka, D. New Approach to the Analysis of Manufacturing Processes with the Support of Data Science. Processes 2024, 12, 449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q.; Guo, R. An Unsupervised Method for Industrial Image Anomaly Detection with Vision Transformer-Based Autoencoder. Sensors 2024, 24, 2440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panza, M.A.; Pota, M.; Esposito, M. Anomaly Detection Methods for Industrial Applications: A Comparative Study. Electronics (Basel) 2023, 12, 3971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, G.; Hong, S.H.; Kyzer, T.; Wang, Y. U-TFF: A U-Net-Based Anomaly Detection Framework for Robotic Manipulator Energy Consumption Auditing Using Fast Fourier Transform. Applied Sciences 2024, 14, 6202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, C. Dynamics, Periodic Orbit Analysis, and Circuit Implementation of a New Chaotic System with Hidden Attractor. Fractal and Fractional 2022, 6, 190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Askar, S.S.; Al-Khedhairi, A. Further Discussions of the Complex Dynamics of a 2D Logistic Map: Basins of Attraction and Fractal Dimensions. Symmetry (Basel) 2020, 12, 2001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, G.L.; Gollub, J.P. Chaotic Dynamic: an Introduction. Cambridge University Press, 1996.

- BCM0001 Sensor Specification. Available online: https://www.balluff.com/en-my/products/BCM0001. (accessed on 7 January 2025).

- KR 270 R3100 Ultra K-F ROBOT. Available online: https://my.kuka.com/s/product/kr-270-r3100-ultra-kf/01t58000002hninAAA?language=pl (accessed on 7 January 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).