Submitted:

29 November 2024

Posted:

29 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

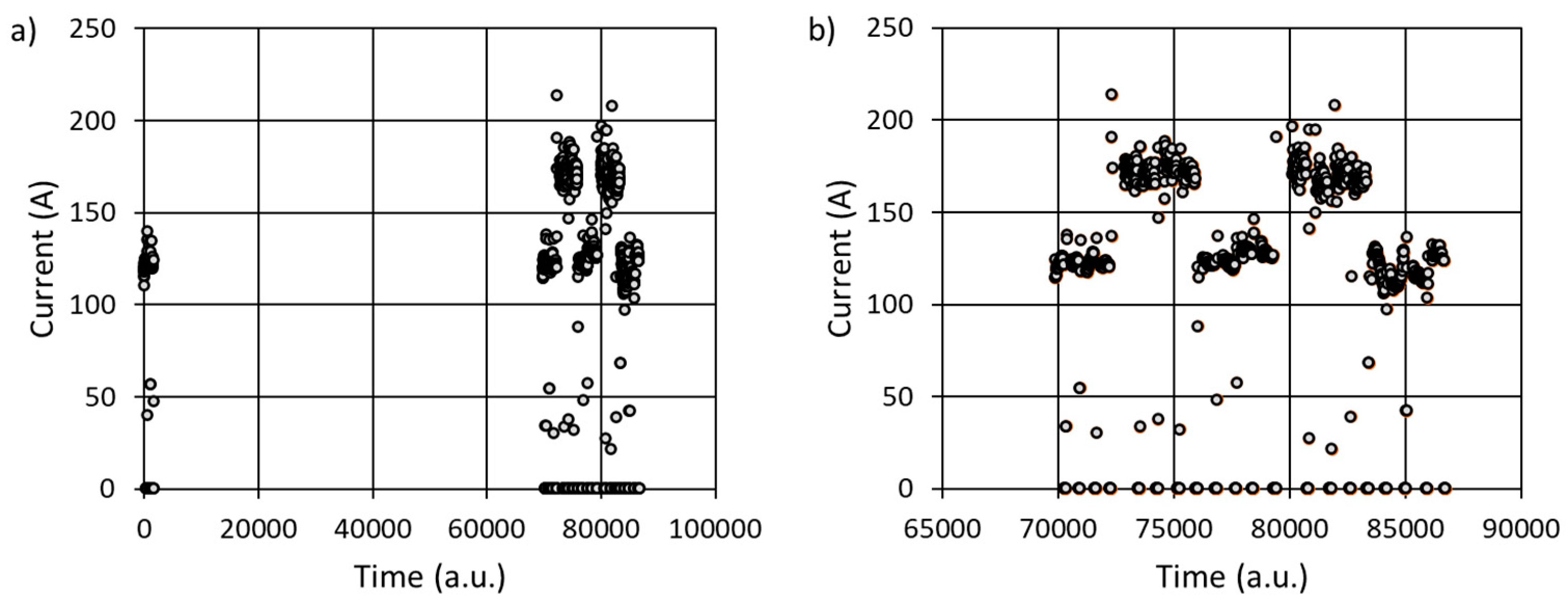

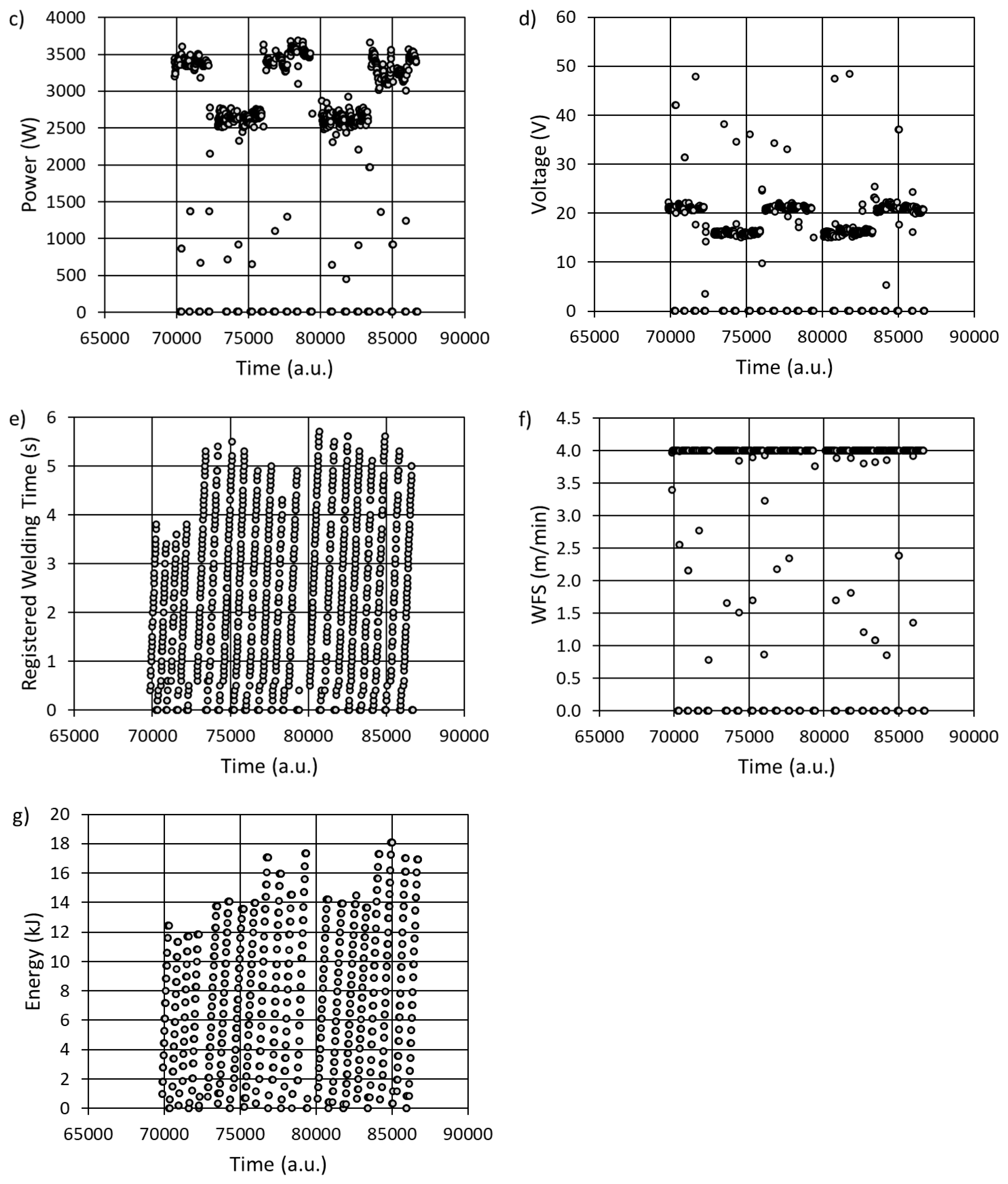

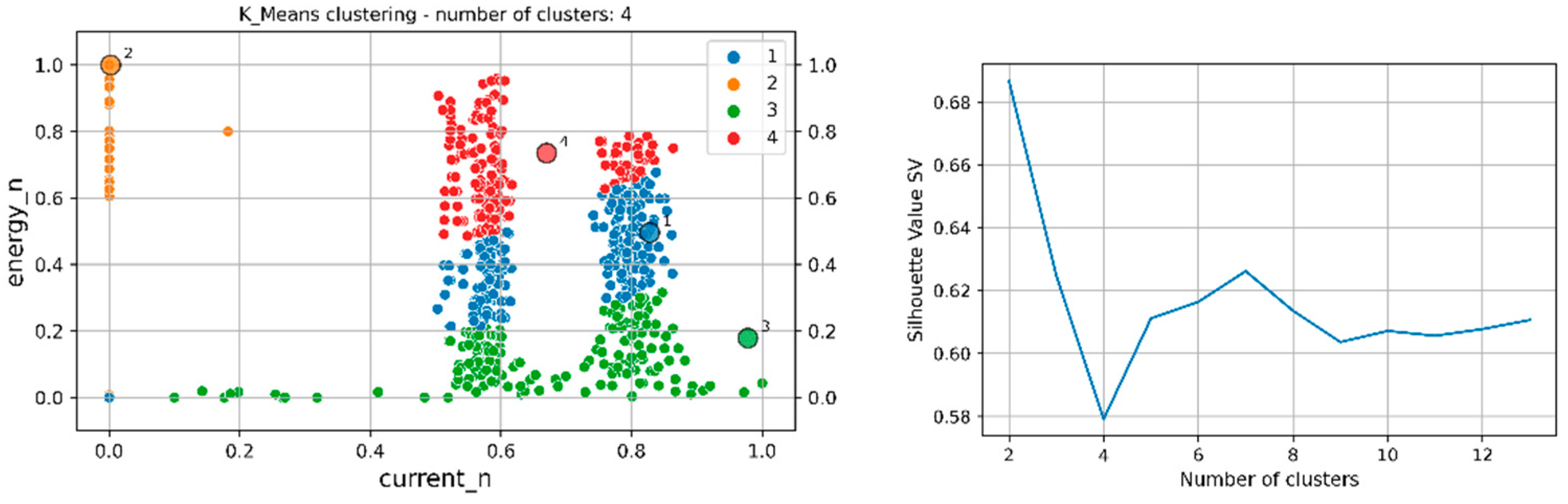

2. Collecting Industrial Data and Samples

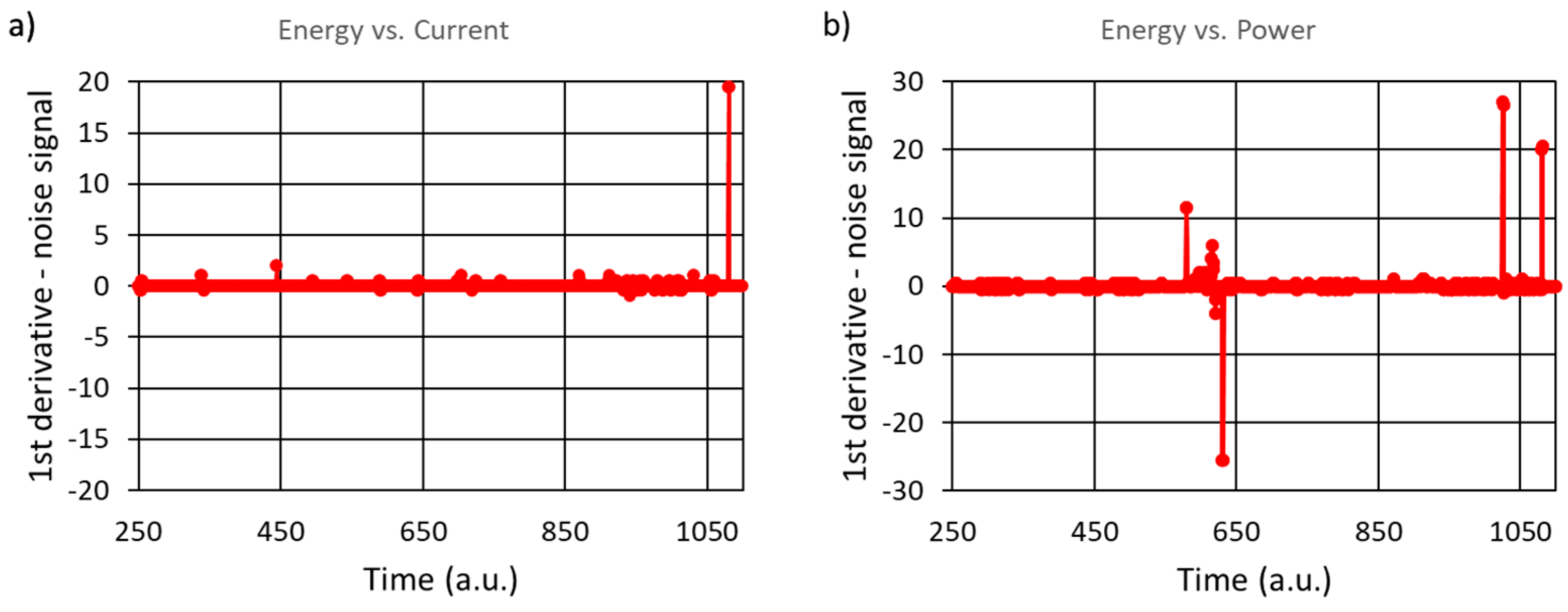

3. Analysis of Results

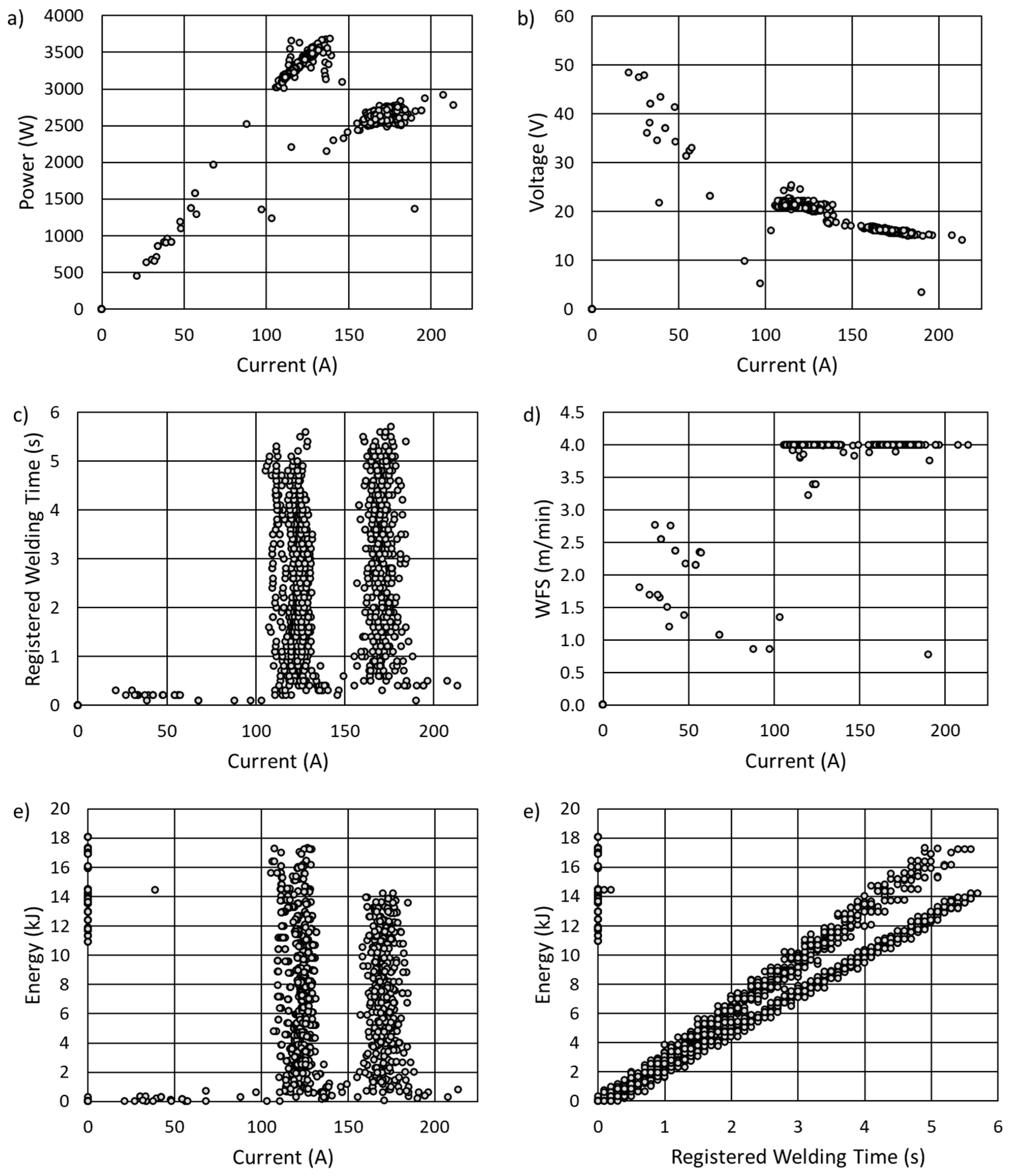

3.1. K-Means Algorithm

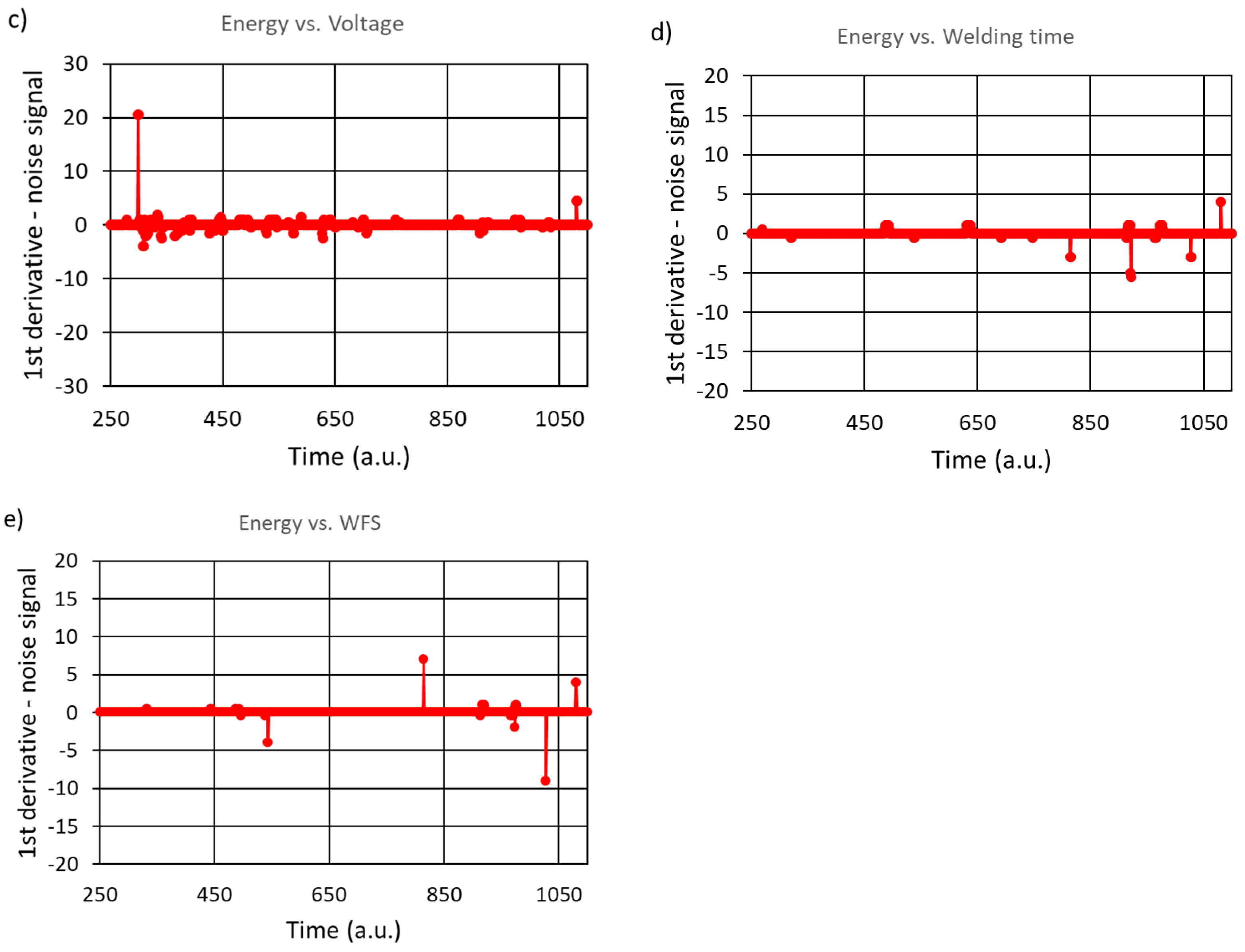

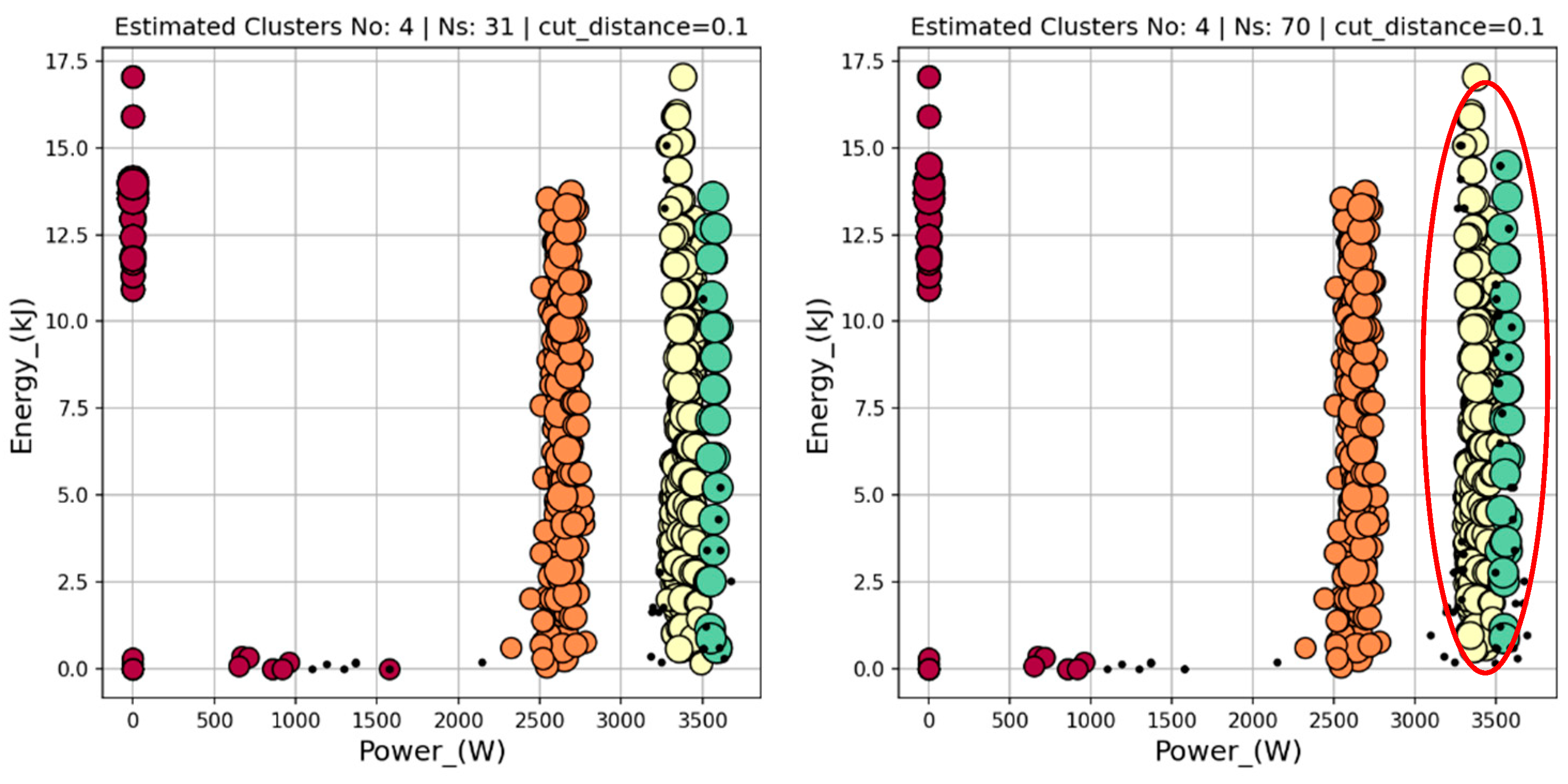

3.2. DBSCAN Algorithm

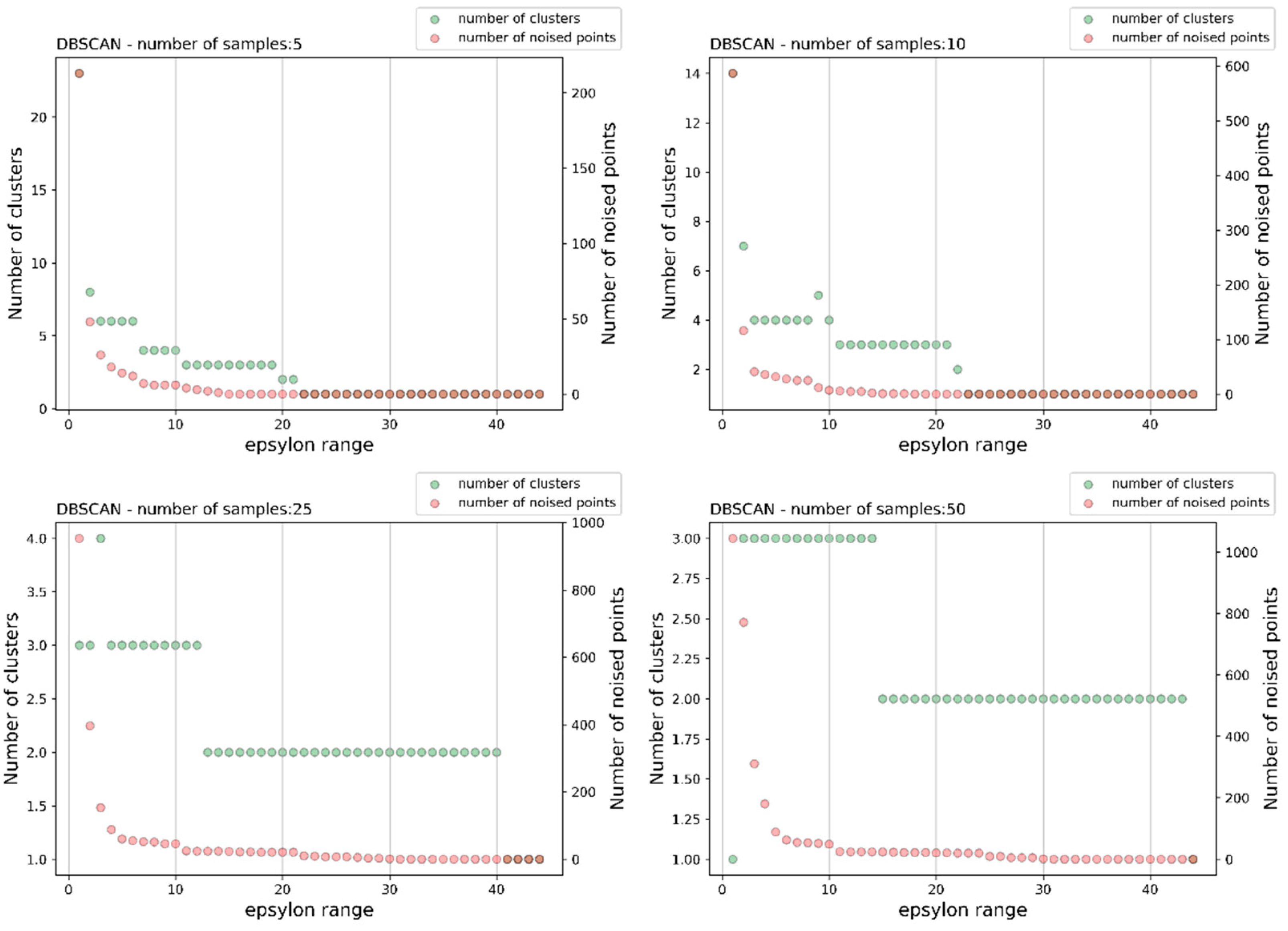

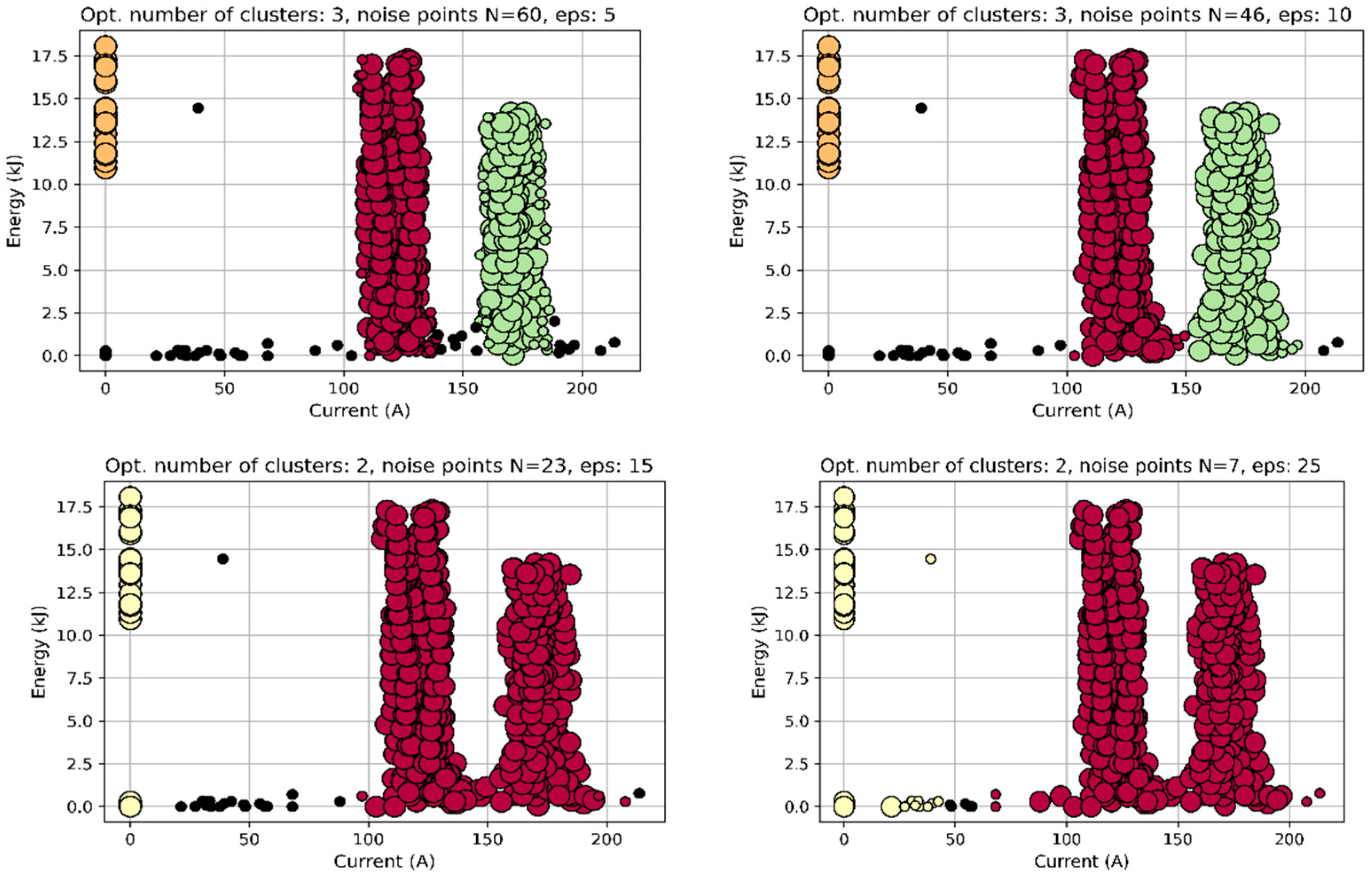

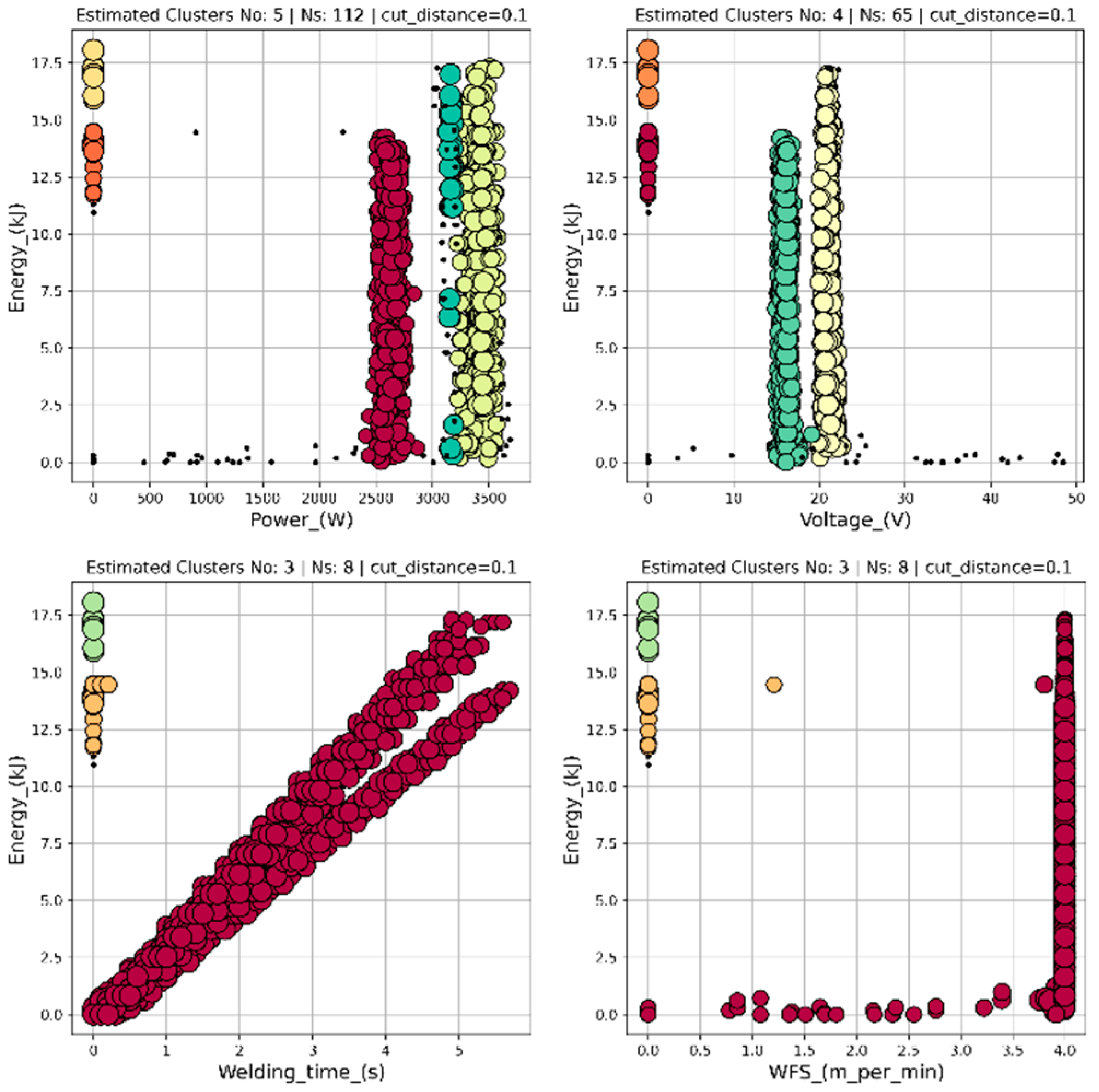

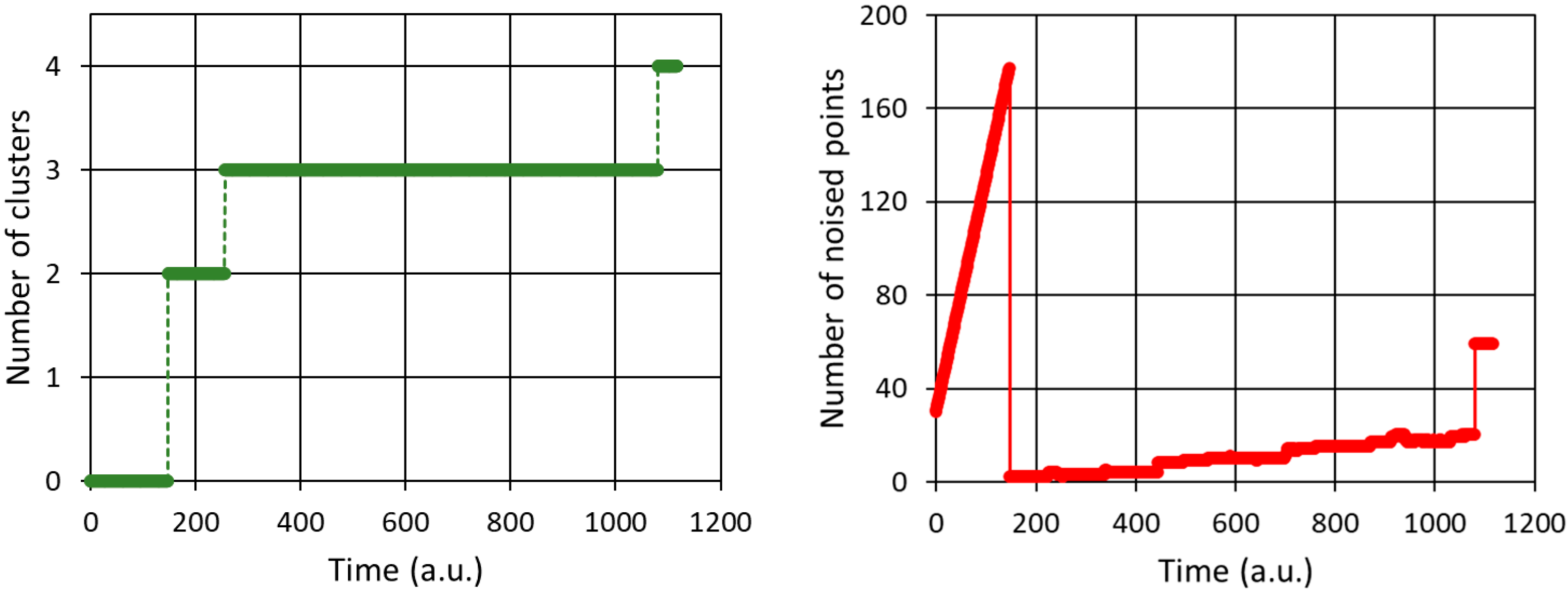

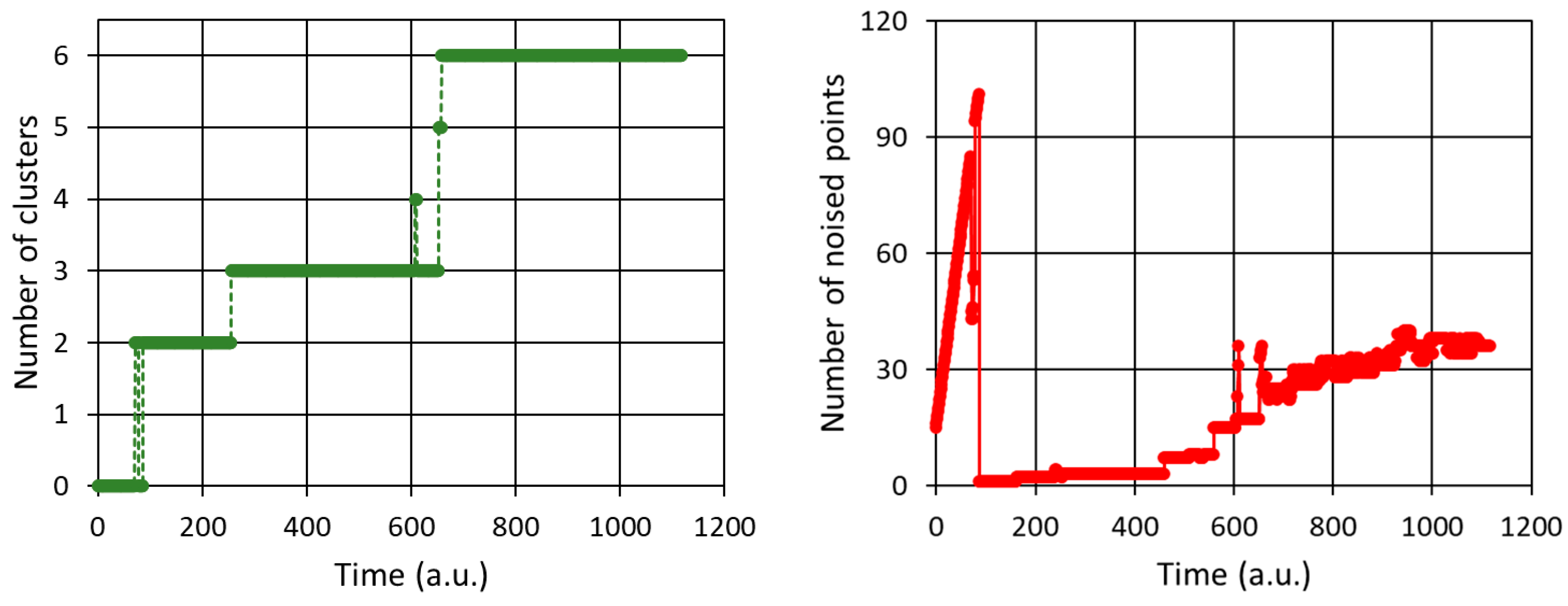

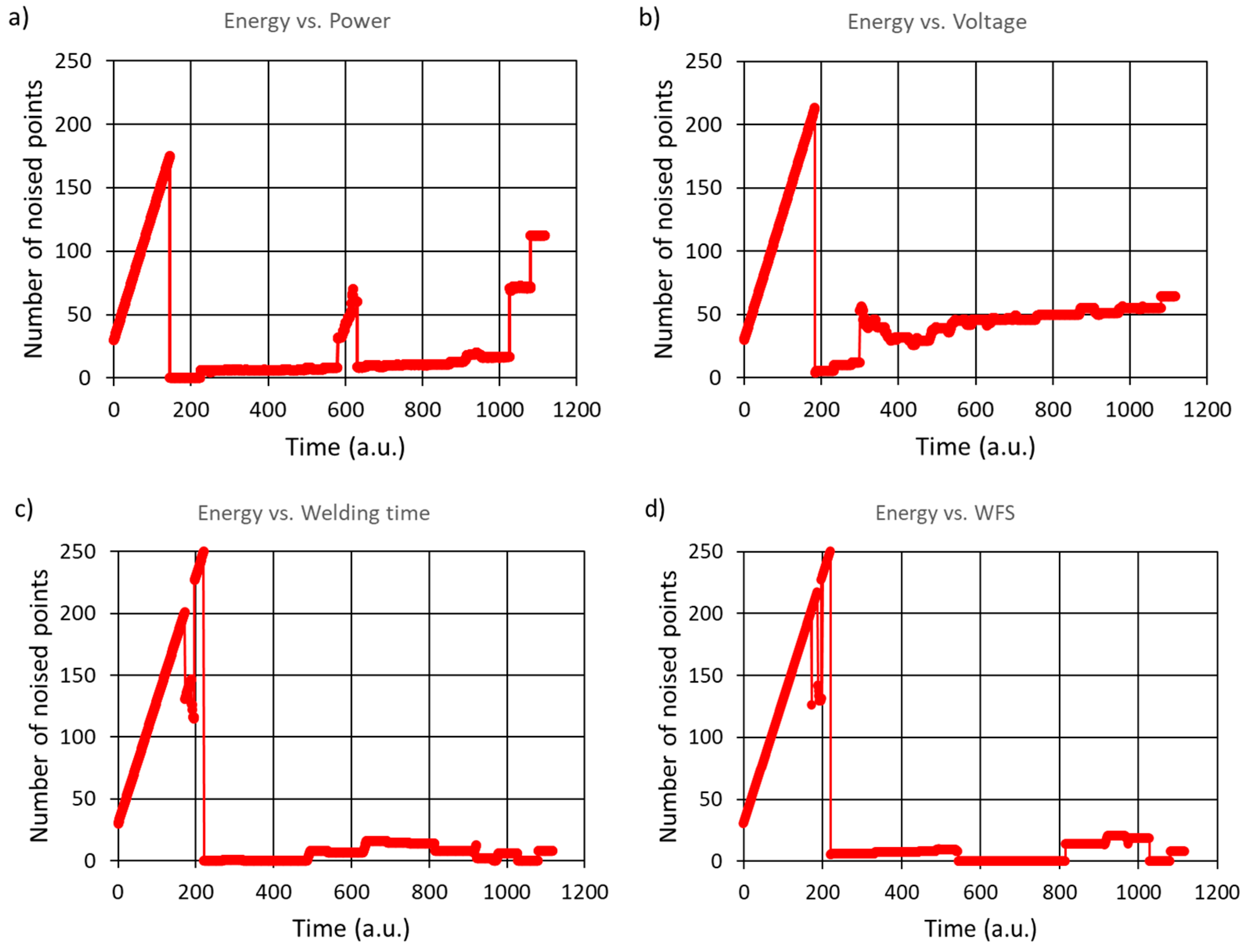

3.3. HDBSCAN Algorithm

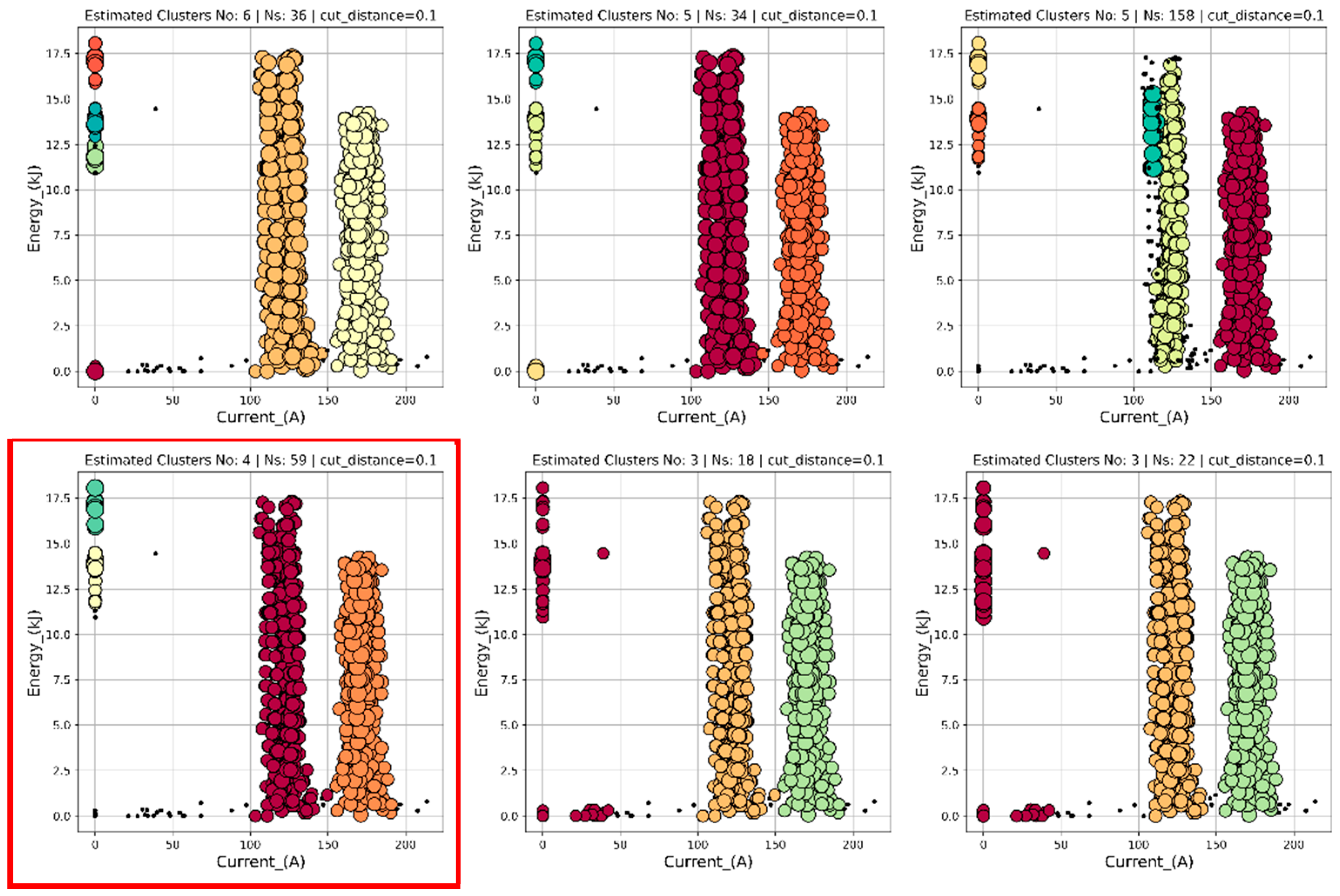

4. Discussion and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Shalev-Shwartz, S.; Ben-David, S. Understanding Machine Learning: From Theory to Algorithms; Cambridge University Press, 2014.

- Goodfellow, I.; Bengio, Y.; Courville, A. Deep Learning; MIT Press, 2016.

- Aggarwal, C. C.; Reddy, C. K. (Eds.). Data Clustering: Algorithms and Applications; CRC Press, 2013.

- Azzalini, A., & Torelli, N. (2007). Clustering via nonparametric density estimation. Statistics and Computing, 17(1), 71–80. [CrossRef]

- Kriegel, H. P., Kröger, P., Sander, J., & Zimek, A. (2009). Density-based clustering. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Data Mining and Knowledge Discovery, 1(3), 231–240.

- Campello, R. J. G. B., Hruschka, E. R., & Sander, J. (2015). Clustering based on density measures and automated cluster extraction. Data Mining and Knowledge Discovery, 29(3), 802–830.

- Campello, R. J., Moulavi, D., Zimek, A., & Sander, J. (2013). Density-based clustering based on hierarchical density estimates. In Pacific-Asia Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining (pp. 160–172). Springer.

- McInnes, L., Healy, J., & Astels, S. (2017). HDBSCAN: Hierarchical density-based clustering. Journal of Open Source Software, 2(11), 205. [CrossRef]

- Hartigan, J. A., & Wong, M. A. (1979). A K-means clustering algorithm. Applied Statistics, 28(1), 100–108.

- Jain, A. K. Data clustering: 50 years beyond K-means. Patt. Recogn. Lett. 2010, 31, 651–666. [CrossRef]

- Schubert, E., Sander, J., Ester, M., Kriegel, H. P., & Xu, X. (2017). DBSCAN revisited, revisited: Why and how you should (still) use DBSCAN. ACM Transactions on Database Systems, 42(3), 19.

- Retiti Diop Emane, C.; Song, S.; Lee, H.; Choi, D.; Lim, J.; Bok, K.; Yoo, J. Anomaly Detection Based on GCNs and DBSCAN in a Large-Scale Graph. Electronics 2024, 13, 2625. [CrossRef]

- Emmons, S., Kobourov, S., Gallant, M., & Börner, K. (2016). Analysis of network clustering algorithms and cluster quality metrics at scale. PLOS ONE, 11(7), e0159161. [CrossRef]

- Xu, R., & Wunsch, D. (2005). Survey of clustering algorithms. IEEE Transactions on Neural Networks, 16(3), 645–678.

- https://scikit-learn.org/.

- Ackermann, M. R., Blömer, J., & Sohler, C. (2010). Clustering for metric and non-metric distance measures. ACM Transactions on Algorithms, 6(4), 1–26.

- Schubert, E., Sander, J., Ester, M., Kriegel, H. P., & Xu, X. (2017). DBSCAN revisited, revisited: Why and how you should (still) use DBSCAN. ACM Transactions on Database Systems, 42(3), 19.

- Hasan, M.M.U.; Hasan, T.; Shahidi, R.; James, L.; Peters, D.; Gosine, R. Lithofacies Identification from Wire-Line Logs Using an Unsupervised Data Clustering Algorithm. Energies 2023, 16, 8116. [CrossRef]

- Han, X.; Armenakis, C.; Jadidi, M. Modeling Vessel Behaviours by Clustering AIS Data Using Optimized DBSCAN. Sustainability 2021, 13, 8162. [CrossRef]

- Munguía Mondragón, J.C.; Rendón Lara, E.; Alejo Eleuterio, R.; Granda Gutirrez, E.E.; Del Razo López, F. Density-Based Clustering to Deal with Highly Imbalanced Data in Multi-Class Problems. Mathematics 2023, 11, 4008. [CrossRef]

- Yun, K.; Yun, H.; Lee, S.; Oh, J.; Kim, M.; Lim, M.; Lee, J.; Kim, C.; Seo, J.; Choi, J. A Study on Machine Learning-Enhanced Roadside Unit-Based Detection of Abnormal Driving in Autonomous Vehicles. Electronics 2024, 13, 288. [CrossRef]

- DeMedeiros, K.; Koh, C.Y.; Hendawi, A. Clustering on the Chicago Array of Things: Spotting Anomalies in the Internet of Things Records. Future Internet 2024, 16, 28. [CrossRef]

- edersen, K.; Jensen, R.R.; Hall, L.K.; Cutler, M.C.; Transtrum, M.K.; Gee, K.L.; Lympany, S.V. K-Means Clustering of 51 Geospatial Layers Identified for Use in Continental-Scale Modeling of Outdoor Acoustic Environments. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 8123. [CrossRef]

- Cesario, E.; Lindia, P.; Vinci, A. Detecting Multi-Density Urban Hotspots in a Smart City: Approaches, Challenges and Applications. Big Data Cogn. Comput. 2023, 7, 29. [CrossRef]

- Gadal, S.; Mokhtar, R.; Abdelhaq, M.; Alsaqour, R.; Ali, E.S.; Saeed, R. Machine Learning-Based Anomaly Detection Using K-Mean Array and Sequential Minimal Optimization. Electronics 2022, 11, 2158. [CrossRef]

- Guerreiro, M.T.; Guerreiro, E.M.A.; Barchi, T.M.; Biluca, J.; Alves, T.A.; de Souza Tadano, Y.; Trojan, F.; Siqueira, H.V. Anomaly Detection in Automotive Industry Using Clustering Methods—A Case Study. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 9868. [CrossRef]

- Choi, W.-H.; Kim, J. Unsupervised Learning Approach for Anomaly Detection in Industrial Control Systems. Appl. Syst. Innov. 2024, 7, 18. [CrossRef]

- Barrera, J.M., Reina, A., Mate, A. et al. Fault detection and diagnosis for industrial processes based on clustering and autoencoders: a case of gas turbines. Int. J. Mach. Learn. & Cyber. 13, 3113–3129 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Nelson, W.; Culp, C. Machine Learning Methods for Automated Fault Detection and Diagnostics in Building Systems—A Review. Energies 2022, 15, 5534. [CrossRef]

- Vijayan, D.; Aziz, I. Adaptive Hierarchical Density-Based Spatial Clustering Algorithm for Streaming Applications. Telecom 2023, 4, 1-14. [CrossRef]

- Mazzei, D.; Ramjattan, R. Machine Learning for Industry 4.0: A Systematic Review Using Deep Learning-Based Topic Modelling. Sensors 2022, 22, 8641. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Guo, J.; Yuan, F.; Qiu, Y.; Wang, P.; Cheng, F.; Gu, Y. Enhancement Methods of Hydropower Unit Monitoring Data Quality Based on the Hierarchical Density-Based Spatial Clustering of Applications with a Noise–Wasserstein Slim Generative Adversarial Imputation Network with a Gradient Penalty. Sensors 2024, 24, 118. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).