Energy consumption continues to grow worldwide as a result of progressive humankind’s development. As energy needs rise, the world has evolved from burning wood, wind, waterfalls, coal, fossil fuels, solar and nuclear energy sources. Although it is big progress, energy sources are currently dominated by non-renewable sources with 80.45% nearly equal to 143,939 TWh in 2022. Thus, non-replenishable energy resources must be consumed with attention because they continually fade away. Natural gas held 22.03% of the non-renewable energy resources. From 2012 to 2022, natural gas consumption rose to 36.5% and is expected to continue to grow as it is deemed a cleaner than other fossil fuels [

1]. Natural gas emits 50 to 60% less CO

2 than coal [

2]. In 2016, the transportation sector solely consumed 28.55% of the used energy resources [

3]. While from 2010 to 2022, natural gas consumption in the transportation sector has increased by 27.3% [

4] and it is expected to continually rise. This increase is associated with low cost and low greenhouse gas emission (GHG) than gasoline emitting about 15 to 20% [

2]. Natural gas is mainly transported and stored in its cryogenic form, at atmospheric pressure, due to its shrinkage of less than 600 times its occupancy volume under standard conditions [

5]. During cryogenic transportation and storage of natural gas, LNG boils off due to heat leakage from surroundings and generates boil-off gas (BOG) [

6]. Continuous generation of BOG increases pressure inside LNG carriers, export and receiving terminals. For safety purposes, BOG is often resealed out of tanks for pressure relief [

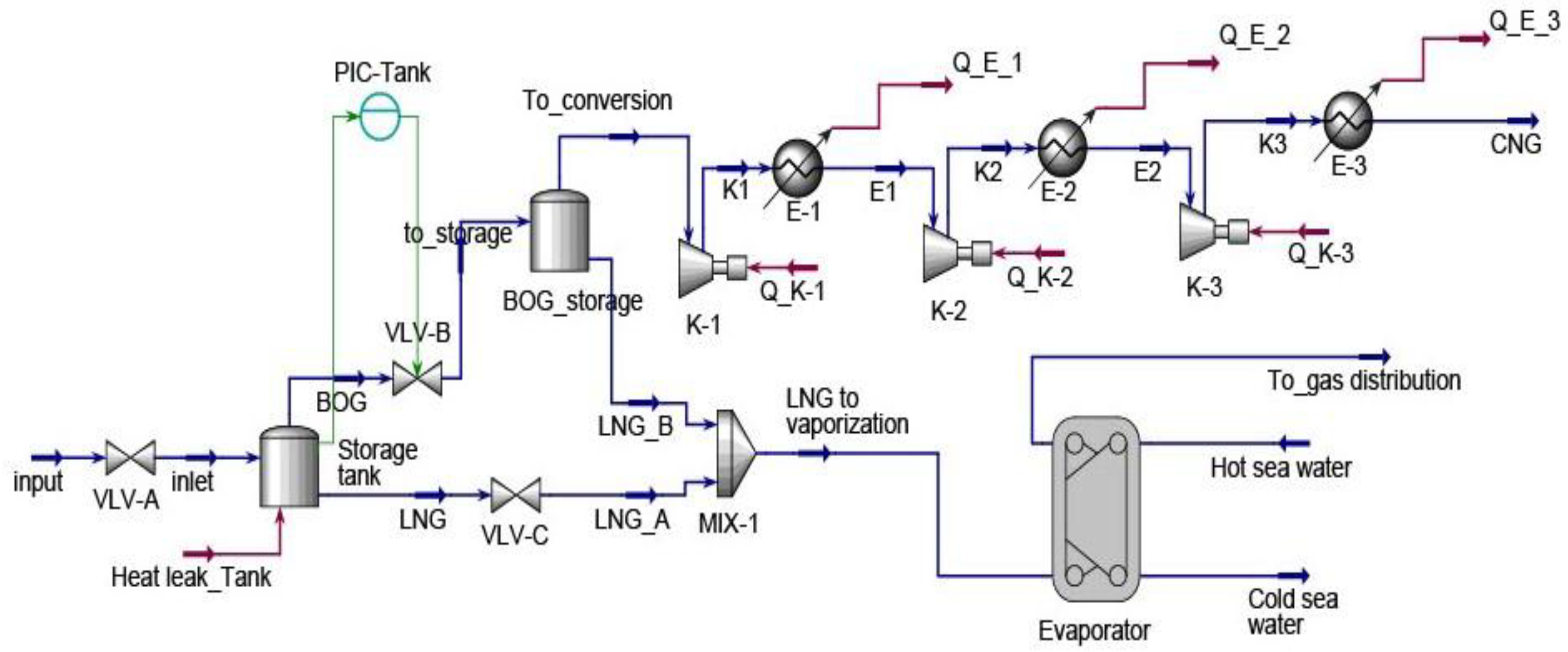

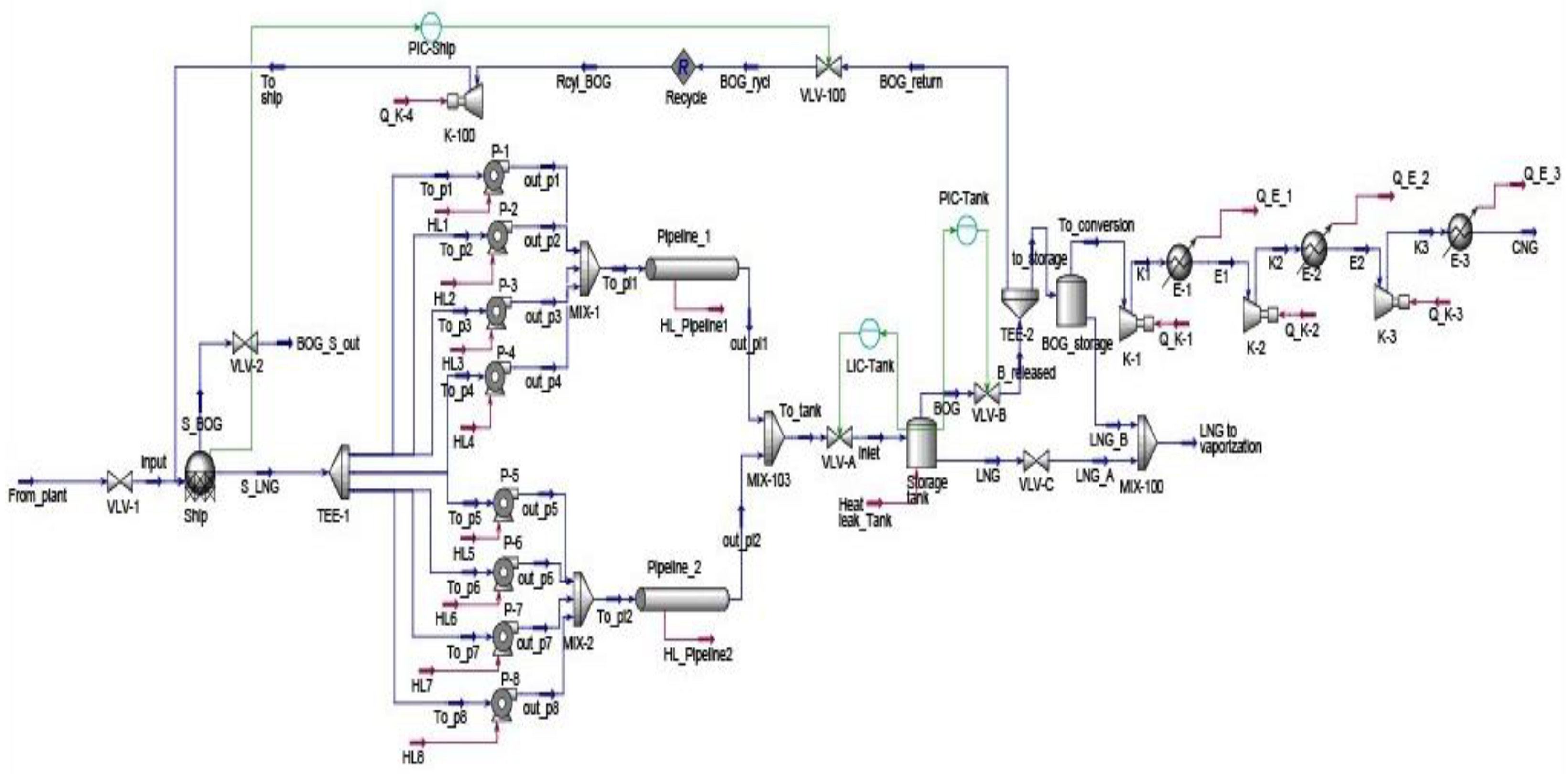

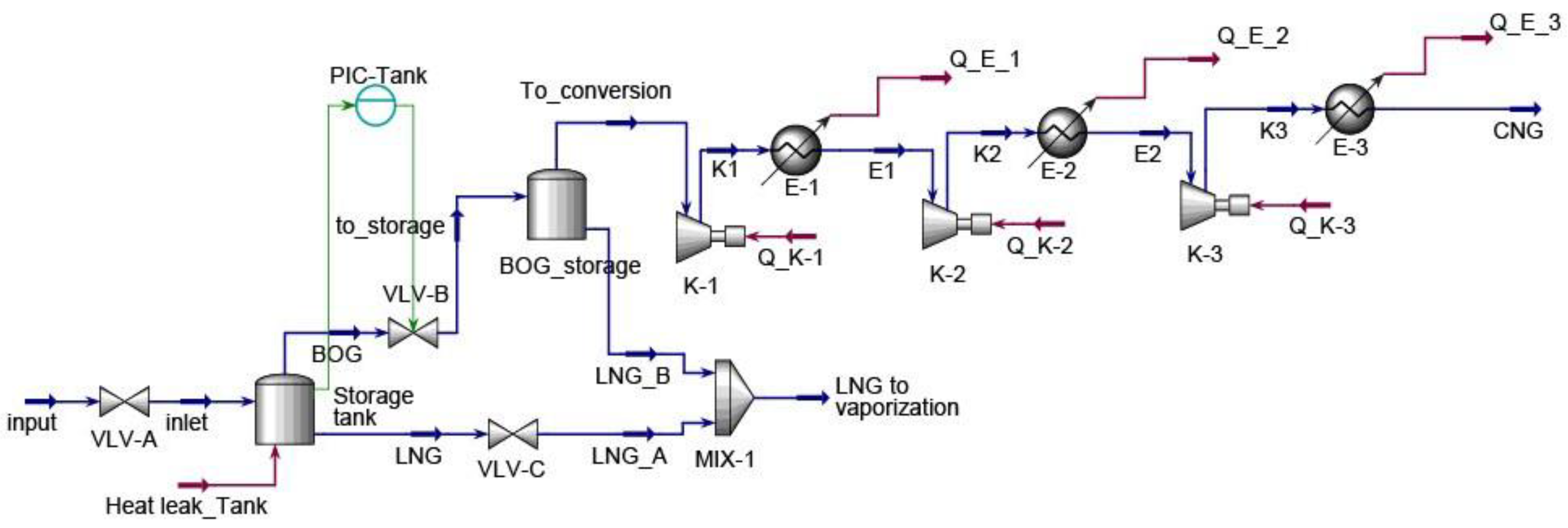

7]. At an LNG receiving terminal, generated BOG originates from heat leakage into terminal facilities, pumping, pressure drop and mixing two LNGs of different composition. The released BOG is burnt, vented and compressed to send-out pressure; then it is re-liquefied and used as LNG regasification fuel, or filled into unloaded LNG ship carriers to regulate carrier tank’s pressure and temperature [

5,

7]. For long distances, natural gas is most economically transported in liquid form through vessels across the whole world [

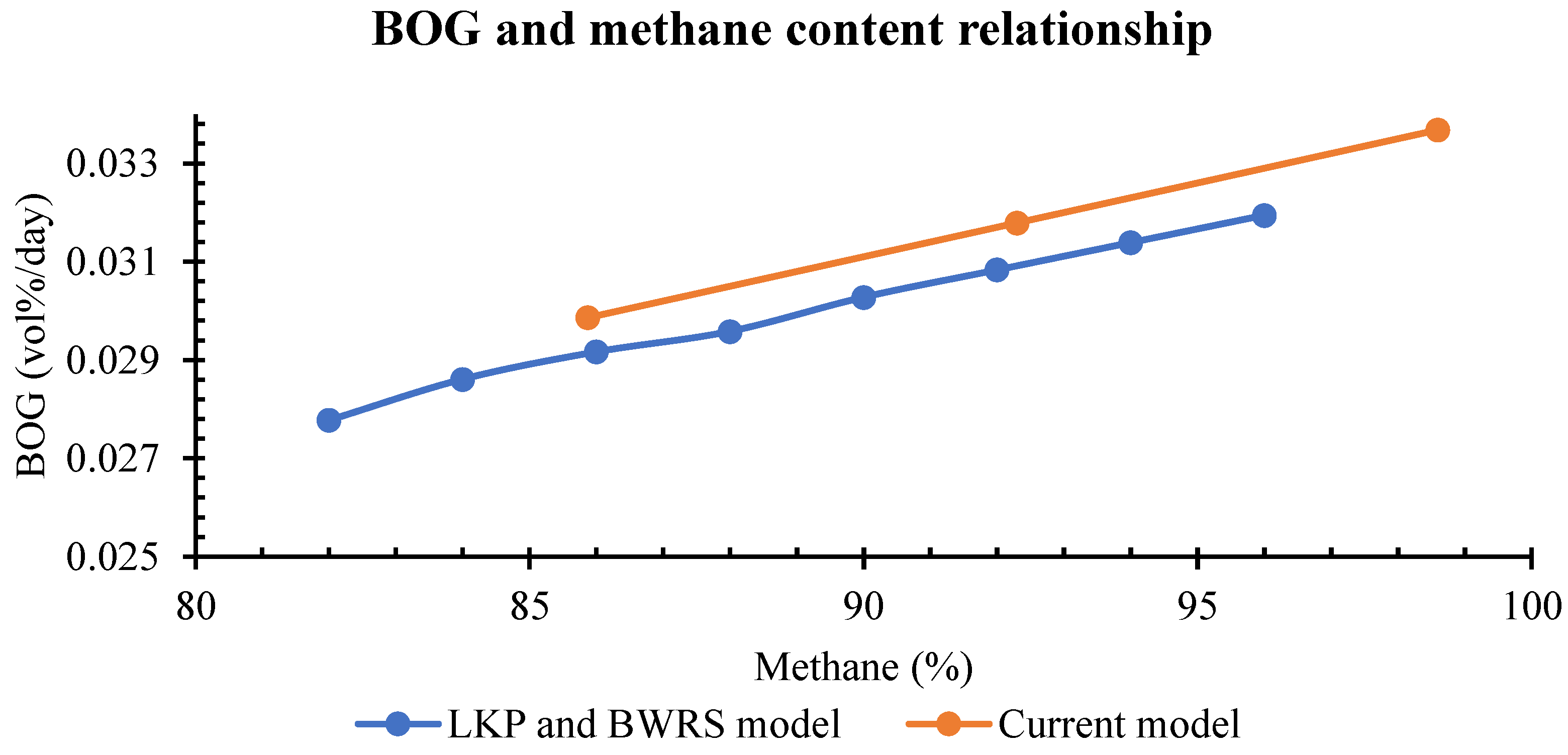

8]. During the loading, transport or shipping, and unloading of the LNG, the natural gas evaporates due to the exchange of heat between LNG and the surrounding environment. The BOG is typically in the range of 0.022 to 0.05% of the LNG storage tank per day [

7,

9]. The flaring and venting of BOG are undesirable as it contributes to greenhouse gases emissions and environmental damage. In LNG supply chain, scholars have proposed that BOG can be recovered and used as fuel, or re-liquefied [

7]. The thermodynamically based analysis study has shown that BOG flare optimal minimization at receiving terminal can be achieved in four stages BOG reliquefication system though the capital cost and operating cost remained higher beyond equilibrium line because of use of many compressors [

10]. For proper implementation of the model made by [

9], boil-off rate (BOR) can be reduced to 0.11% of LNG weight inside the tank per day which is 26.7% lower than the rate proposed by International Marine Organization (IMO). Although natural gas short live into the atmosphere after emission, its warming potential is 27 to 30 times per 100 years [

11] and 84 times per 20 years [

12] higher than CO2 because it is predominantly consisting of methane. Gas flaring has been reduced by 3% in 2022 to meet the global ambition of Zero Routine Flaring by 2030. However, in countries such as Algeria, Mozambique, Venezuela, Republic of Congo, India and Russia gas flaring has shown an increase [

12]. BOG is one of the main issues facing LNG receiving terminals, as well as being harmful to the environment, it is also a waste of non-renewable energy resources. In a single tank, the BOG released is usually in the range of 0.02 to 0.05% of an LNG tank volume per day [

13]. If BOG is recovered from a single LNG tank, approximately 0.2 billion m3 of natural gas can be saved from waste and harming the environment [

14]. To tackle environmental concerns, resource wastage, and transportation fuel scarcity, BOG can be recovered and converted into natural gas fuel, i.e. compressed natural gas (CNG). According to [

15], CNG fuel production is feasible from a natural gas resource capable of supplying 1 to 7 billion m3 per year which is suitable for BOG generally produced at LNG receiving terminal and supplied to consumers not far from 2000 km. suggested that natural gas composition should be containing methane with minimum 90%, Ethane of 4% as the maximum, propane not more than 1.7%, butane and heavier not more than 0.7%, carbon dioxide and nitrogen not more than 3%, hydrogen less or equal to 0.1%, carbon monoxide less or equal to 0.1% and oxygen not more than 0.5%. According to [

16], the typical CNG combustive properties are MON of 120, molar mass of 16.04, carbon weight fraction of 75% mass, stoichiometric air/fuel ratio of 16.79 and mixture density of 1.24, lower heating value of 47.377 MJ/kg and stoichiometric lower heating value of 2.77 MJ/kg, flammability range between 5 and 15, and spontaneous ignition temperature of 6450C. According to [

17], physicochemical CNG properties value for octane number range from 120 to 130, molar mass of 17.3, stoichiometric air/fuel mass of 17.2 and mixture density of 1.25, lower heating value of 47.5 MJ/kg and stoichiometric lower heating value of 2.62 MJ/kg, energy of combustion of 24.6 MJ/m3, flammability in air range from 4.3 to 15.2% vol. in air, speed of propagation of 0.41m/s, adiabatic flame temperature of 18900C, auto-ignition temperature of 5400C, and Wobbe index between 51 and 58 MJ/m3. The aim of this study is to recover excess the BOG released from the storage tank and use it as CNG fuel for vehicles operating around the LNG receiving terminal within a radius of 2000 km. The planet is facing severe climate change while it fears the nearing end of fossil resources; therefore, proper use of resources and sustainable innovative energy solutions are of vital concerns. BOG flaring and vent have been contributing adverse greenhouse gases through the result of CO

2 and unburned methane. CO

2 emission pollutes the atmosphere and BOG flaring is one of its sources. Methane is the major component of BOG. Despite the various uses of methane gas, its emission has a higher warming potential than CO

2 though it short-lived [

11,

12,

18]. Although CNG is less expensive than petrol and diesel, there is a problem of its shortage due to many factors including increase of consumers for it is gaining preference in many countries such as Pakistan, the third largest CNG consumer. Among the probable and sustainable ways to solve it, new gas resources are a preferred option [

19]. It is of crucial importance to find a way to fully recover BOG and use it efficiently to sustainably and effectively use responsibly the natural gas resources. CNG fuel for natural gas vehicles (NGV) is believed to be one of the viable options for adding value to BOG. Therefore, the study attempts to unlock the potential use of BOG as CNG fuel while minimizing GHG emission and environmental damage. The main objective of this study is to evaluate and recover the excess BOG generated from LNG receiving terminal into CNG fuel for vehicles. To this end, this study evaluates the amount of BOG excess generated from each source at the LNG receiving terminal, the amount of BOG recoverable and is converted into CNG fuel. Finally, the energy consumed in the process of converting BOG into CNG fuel is evaluated, whether the conversion of BOG into CNG is technically feasible and the produced CNG fuel on specification. To this end, we aim to: