1. Introduction

1.1. Historic Background of the Synagogues of Greece

Greek Jewish history has its roots in antiquity. Archaeological evidence indicates of the existence of numerous vibrant organized Jewish communities

1, wealthy enough to erect prominent synagogues elaborated with magnificent mosaics. For example, in Aegina (c.4th CE)

2 (

Figure 1) and Chios (c.4th CE)

3 . The Greek speaking Romaniote Jewish communities had their own customs and liturgy and their synagogues a very distinct architectural typology, primarily as indicated by their interior organization. In western Greece, communities such as Ioannina, Chalkis, and Arta, were strongly influenced by the Venice tradition and the bipolar synagogues found in Venice

4 (

Figure 2). Another Romaniote tradition found in the island of Rhodes, hints to a different typology

5. There, the tradition was apparently strongly influenced by the magnificent basilica in Sardis, and in particular the adoption of a dual Holy Ark on the southeastern wall of the synagogue (

Figure 3). This type has been recently addressed and published by the author, triggered by site visits and later field surveys at the historic synagogues Kahal Tikkun Hazot and Kahal Grande in Rhodes.

6

After the 15th century, Spanish Jews (Sephardim) arrived to Greek cities under Ottoman rule, establishing flourishing communities and reviving commercial activity throughout Greece. In addition, developing a distinct synagogue typology, inspired by the synagogues of Spain and the rules of Halakhah.

7 The city of Thessaloniki, developed as a prominent center of Jewish life, with distinguished institutions and nearly 60 synagogues scattered throughout the city until the eve of the Second World War.

8 During the Ottoman rule, Jewish quarters were located in the historic city centers of the geographic area of Greece, included within walls, confined and often closed by gates, where vibrant Jewish communities lived. Their proximity to the city center and the shared market space with Greeks, Muslims and Armenians, enabled contact and co-existence, often interrupted by tension and sometimes violent events. In Ottoman times, a different synagogue typology prevailed, characterized by a square or rectangle building with 4 columns in the center (

Figure 4). Within this defined space, under a decorated flat dome or a daylit lantern, stood the

Bimah of the synagogues, facing the Holy Ark. The Holy Ark, always oriented towards Jerusalem, as required by Halakhic laws.

9 The seating surrounded the

Bimah with benches or wooden chairs from all directions, except from the space between the

Bimah and the Holy Ark.

Prior to Second World War lived in Greece more than 70,000 Jews. They lived in 27 organized Jewish communities scattered throughout Greece

10. Each community had at lest one synagogue, and several communal institutions. Very often, the Jewish community center (or club) was located adjacent to the synagogue. In Thessaloniki, the largest Jewish community with approximately 56,000 members, had nearly 59 synagogues and

midrashim (small prayer halls) concentrated throughout the city center

11, the east and northern parts of the city. A map created recently by the author for the Greek National Archaeological Registry (

Figure 5) and the Jewish Museum of Thessaloniki, indicates the exact location of nearly 70 synagogues in the city and nearly 270 synagogues and Jewish sites throughout Greece. They represent in digital form, the extensive Jewish presence in Thessaloniki in particular, and in Greece in general, before the Second World War and the Holocaust.

The deportation of the Greek Jewish communities took place between 1943 and 1944, under German and Bulgarian occupation. The Greek Jewish communities were annihilated by 87% in the Holocaust. In Thessaloniki, the percentage reached 96%. This loss and destruction devasted Jewish life and presence in the Greek cities. Jewish institutions, hospitals, welfare organizations and primarily synagogues were vandalized, looted, occupied by new owners or destroyed

12. Only a handful survived. Out of approximately 100 synagogues prior to the Second World War, only a fraction survived. Many in ruins, like, for example in Volos and Ioannina. Others were occupied by Christian organizations, for example in Xanthi, Alexandroupolis and Didimoticho (

Figure 6) where they run Sunday schools.

Immigration to Israel, to large cities – primarily, Athens - or to other countries, further reduced the number of Jews in most cities. Starting in the 1970s, many surviving Jewish communities were officially dissolved. Their synagogues followed their fate. In most cases, their plots were sold, and the buildings demolished. Documentation of Greek synagogues prior to the Second World War is rare. The Italian archive in the Dodecanese islands, where the architectural drawings of Kahal Shalom synagogue in Kos are located and the diagrams for the synagogues Ricos and Talmud Torah found in the Registry in Rhodes, are an exception. As a result, when between the end of 1970s and the middle of the 1990s when many of the abandoned synagogues were demolished, their traces, in their majority, were lost forever.

A rare archive, to which the author was granted full rights, belonging to an architect from the 1960s, proved to have preserved some of these traces. Further made accessible through digitization and dissemination by the author.

1.2. The Survey and Study of the Synagogues of Greece

Documenting, mapping and representing demolished synagogues in Greece, today, adds an historic and architectural layer on existing urban space, to make visible what is invisible. Thus bring to life a lost heritage. Reconstructing the location and form of lost synagogues, is not only an attempt to preserve their memory. It is also an attempt to preserve the memory of diversity and multi-culturalism of modern cities, made homogeneous after reconstruction that followed the Second World War. The project initiated by the author, diverts from the strict border of architectural survey and documentation, and allows the process to be enriched with historic and archival research, and interviews with people – Jews and non-Jews. They bring the building alive through their personal narrative, about the city, the synagogue and the Jewish community before the Second World War. The project aims to preserve, but also to give a form and a voice to invisible buildings and places once vibrant with Jewish life. First, through digitization of the in-situ surveys and documentations. Then, exploring digital technologies to make the representation more accurate, more engaging and more interactive. The project also adopts conventional dissemination methods, primarily publications, exhibitions, and story-telling, to make a nearly invisible heritage visible to wider audiences.

The survey project by the author spans three decades, of compilation of archival and visual documentation regarding the lost synagogues throughout Greece, and subsequently, of reconstructing and representing them in digital form. Especially, when synagogues are subsequently demolished. The survey work included photographic documentation of the buildings, not only in the current state they were captured, but also with historic visual evidence of the buildings from archives and private collections. The digitized CAD drawing, of plans, sections, elevations and decorative details, that ensued from this process, capture and represent these synagogues as accurate as possible )

Figure 7). As the visual and architectural documentation, is further enriched with human stories on their tradition and use, the representation and narrative become richer and more engaging. Interviews and discussions with the last surviving Jews in these cities, and often non-Jewish neighbors, convey the story of their neighbors and friends who perished in the Holocaust. They bring the synagogue alive, as it was visited by Jews and non-Jews with their Jewish friends as children, or in social events. Stories, that have already been published by the author in numerous occasions.

13

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. The Documentation Project

The in-situ surveys and documentation project by the author was completed between 1993 and 1996. It formed the basis for the author’s doctorate thesis at the National Technical University of Athens, under the supervision of Prof. Yiorgos Sariyiannis, Prof. Aleka Karadimou-Gerolympou and Dr. Doron Chen. It was completed in 1999. During that time, 22 surviving synagogues were surveyed, some of which were later demolished. The research also included extensive research in archives, primarily the Central Archive for the History of the Jewish People at Givat Ram campus of the Hebrew University in Jerusalem, the archive of the Jewish Museum of Greece in Athens, and the archives of KISE and OPAIE. Within this time frame, the survey drawings were digitized in CAD architectural drawings – floor plans, sections and elevations – and in some cases, rendered drawings of elevations with the original colors of the buildings and 3D digital renderings.

The research was published in 1997, 2011 and later, in a number of publications and articles. Yet, until today, new evidence required new survey expeditions, undertaken by the author, in as late as November 2024 with a survey of two ‘forgotten’ synagogues in Rhodes.

During the time of the author’s expeditions, some synagogues that survived abandoned - like in Xanthi, Didimoticho and Alexandroupolis - were demolished or renovated to the point that their historic character was altered. Other synagogues that stood abandoned for many years – like in Kavala and Komotini – were also demolished. Most were surveyed and documented.

But, what about the synagogues that were demolished before the survey expedition by the author started? What about the synagogues demolished in the 1960s or 1970s or 1980s? How can we reconstruct them accurately? How can we locate exact data on their physical form and architecture?

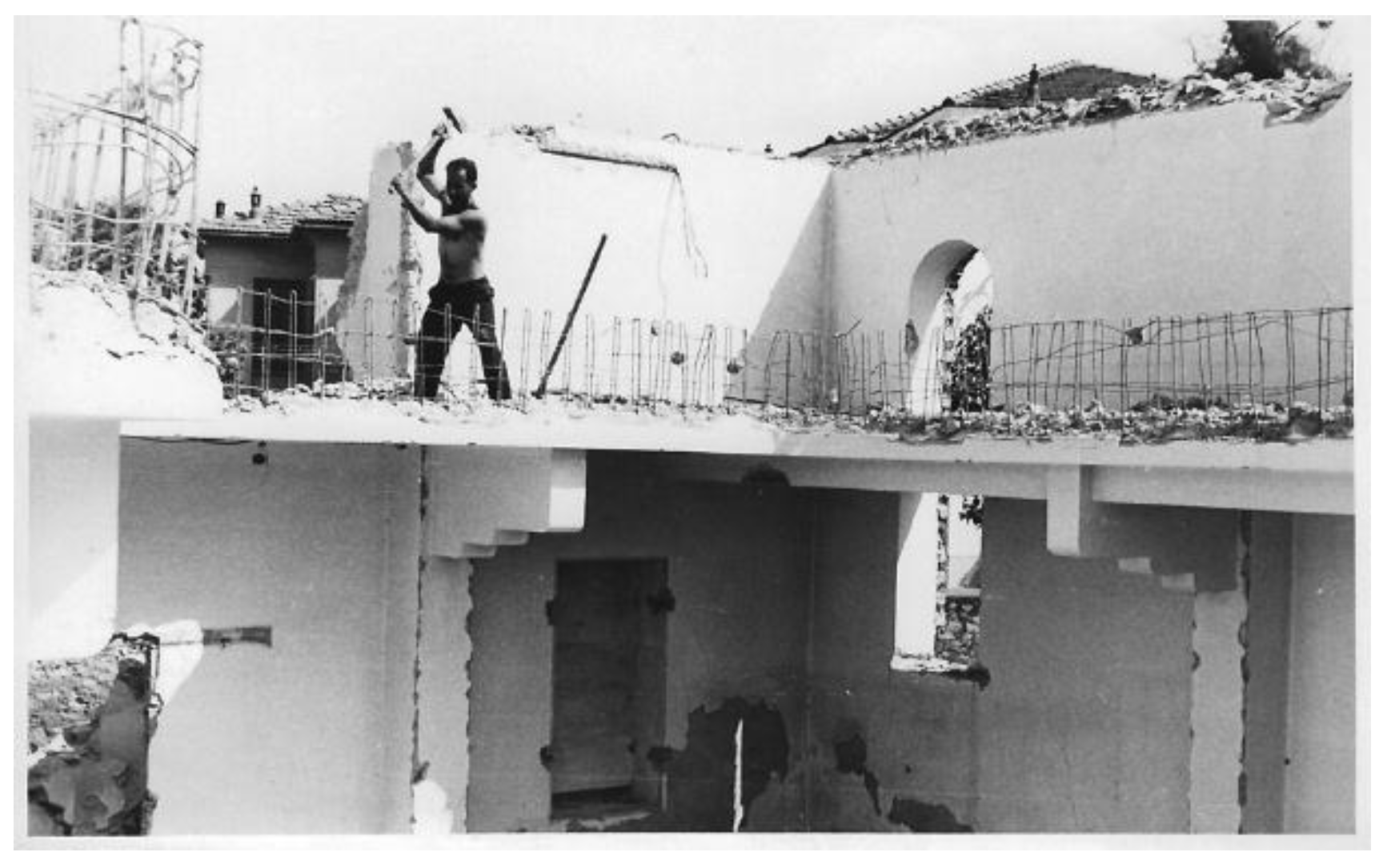

2.2. The Shemtov Samuel Archive

In May 2023, a rare archive, unknown until then, came to fill that gap

14. Under unexpected circumstances, the author was approached by the family of a Greek-Jewish architect and was later granted the full rights to his archive. This archive dating from 1960-1961 was the work of architect Shemtov Samuel (1939-2009) from Volos, Greece. His archive was discovered accidentally in Greece by his nephew, and in his house in London, where Samuel lived with his family since 1969, and recently published by the author.

15

The Samuel archive contains some extraordinary surveys of synagogues that were subsequently demolished. They were made by Samuel in 1960-1961, as a preparation for a lecture he delivered to his class. His record, although incomplete, it is extremely valuable, and the only surviving evidence of some demolished synagogues of that period. The Samuel archive is currently being digitized by the author. The process includes drafting digital CAD drawings from the original survey sketches of Samuel – floor plans, sections and elevations, ensuring that the digital reconstruction drawings will be as faithful as possible to the building.

The Samuel archive includes rare and previously unpublished documentation for the pre-war synagogue in Volos demolished in 1960 after it was damaged in the earthquake of April 19, 1955 (

Figure 8); the synagogue in Drama, which was under construction and left unfinished (1940-1941) and later demolished; the synagogue in Didimoticho and the adjacent Jewish community center, which was abandoned after it was used as a Christian Sunday school; and Beth El synagogue in Kavala, which was damaged during the Bulgarian occupation and left abandoned before it was demolished in the 1970s.

The Samuel archive has left a full record of these buildings in both site surveys and photographic documentation. In combination with the documentation archive of the author, these two archives combined offer an unprecedented and accurate record of the majority of the surviving synagogues after the Second World War in Greece.

3. Results

3.1. Physical and Digital Reconstruction

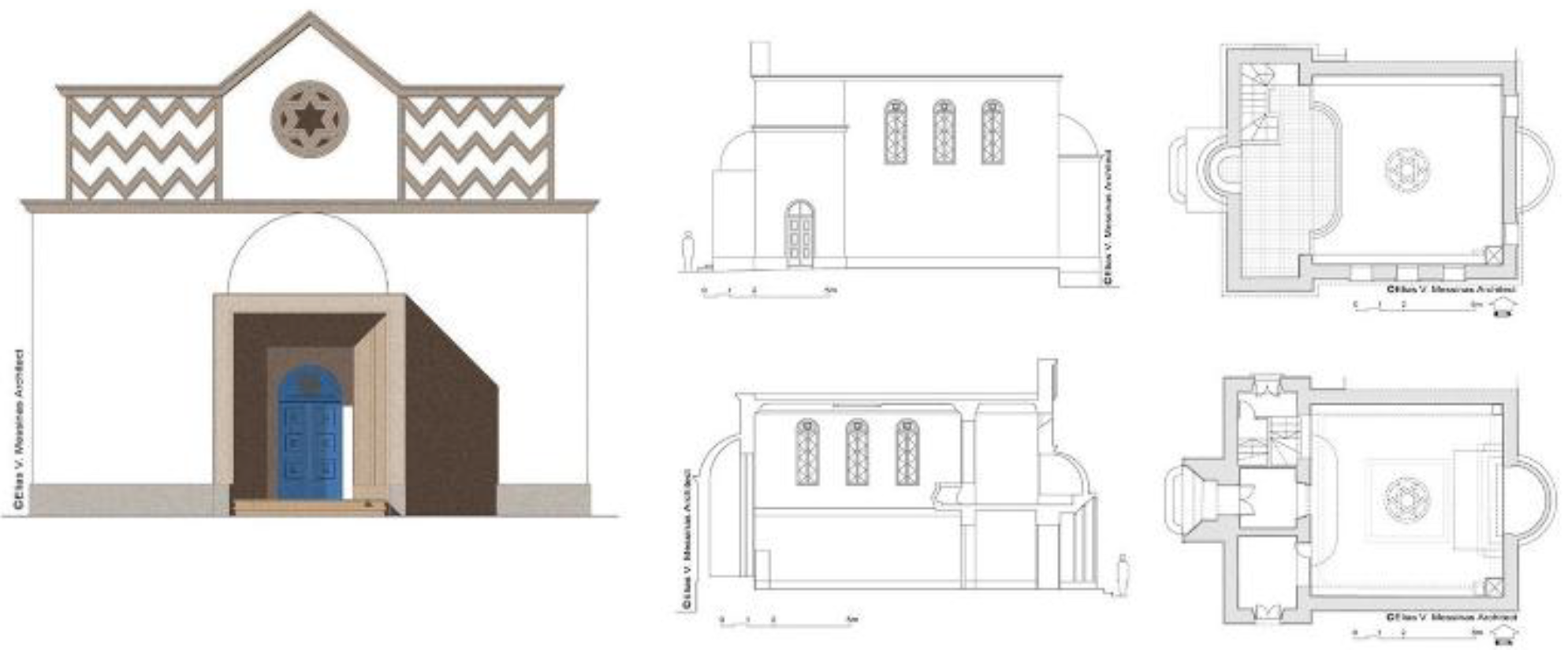

Starting in 2016, after two decades of research and publications on Greek synagogues, a number of architectural commissions came forward to apply this acquired knowledge. First, the Monastirioton (2016), the historic and central synagogue of the city, designed by Austro-Hungarian architect Ernst Loewy (1878-1943) in 1927. Subsequent interventions in its interior and exterior, and reinforcements after the earthquake of June 1978, had left the building, although in use, in a neglected state. Then, in 2017, the synagogue Yad LeZikaron, which was built in 1984 on the ground floor of an office building, that was constructed on the former site of pre-war synagogue Plassa (Burla). What is unique about this synagogue is the historic Holy Ark that belonged to the Ohel Yossef (Sarfati) synagogue of 1921. During the renovation, the Holy Ark was meticulously restored.

In 2019, the author was invited to be the project architect for the Yavanim synagogue in Trikala. The historic building suffered from lack of waterproofing and needed structural reinforcements. The restoration included replacing and repairing the interior finishes with compatible to the original. The restoration included a rather bold intervention: the demolition of the stores in the front of the synagogue, an addition of 1960-62, in order to restore the historic relationship of the synagogue visible and present on the street.

Finally, in 2022, the author was invited to restore the interior of Kahal Shalom in Kos. Built in 1935 after the older synagogue was destroyed in the earthquake of April 1933, the synagogue was built in the Italian Colonial style, by the Italians who ruled the Dodecanese islands (1912-1948). The restoration required extensive research on Italian synagogues of the 1930s and the re-creation of the Holy Ark and

Bimah, followed the practice of urban mining

16 in circular economy, by re-using old furniture.

The restoration of these synagogues required extensive research to expand the understanding of these buildings to the level of materials, colors, finishes and construction techniques. Working in collaboration with experts in the field of restoration, structural reinforcement where needed and upgrading of the electromechanical systems and improving energy performance.

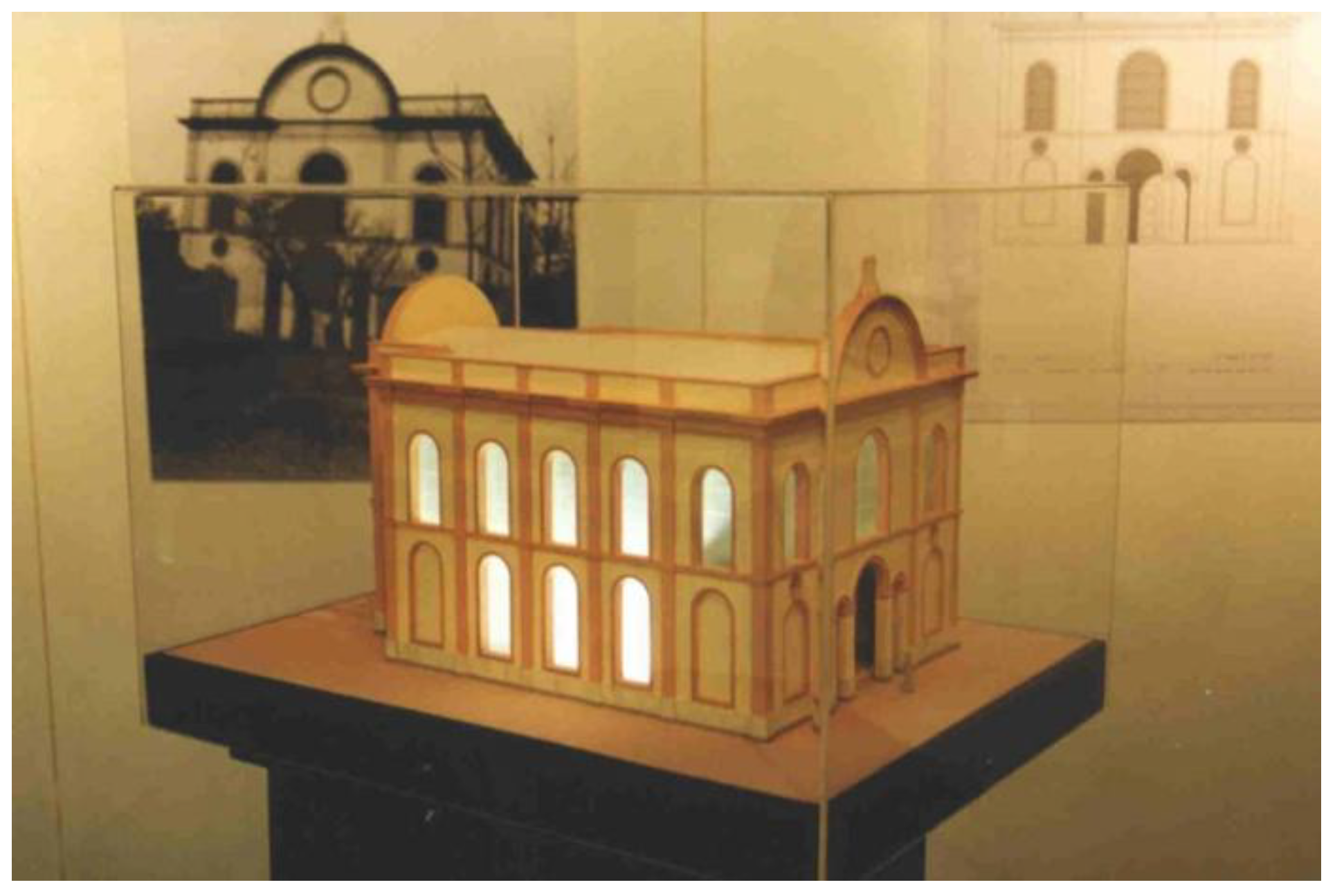

During the surveys and research, visual evidence of lost synagogues started to collect. One example, was Beth Shaul, the central synagogue in Thessaloniki. Designed by Vitaliano Poselli in 1898, it was destroyed by the Nazis immediately after the deportation of the Jewish community in 1943. Through extensive research in city archives, a topographic plan of the synagogue was retrieved. Matched with numerous black and white photographs of different angles of the synagogue, enabled a fairy accurate reconstruction of the synagogue in a full set of digital architectural drawings. When a 3D model of the synagogue was needed to be exhibited at Yad Vashem Valley of the Communities exhibition (

Figure 9) in 1999-2000

17, the author turned to survivors for assistance. In order to find the colors of the synagogue, the author interviewed the late Freddy Abravanel

18, who remembered praying at the synagogue with his family, remembering the colors of the finishes, floor tiles and walls. This information fed into the first ever reconstruction of Beth Shaul synagogue in a laser-cut physical model at 1:20 scale that was exhibited for the first time at Yad Vashem.

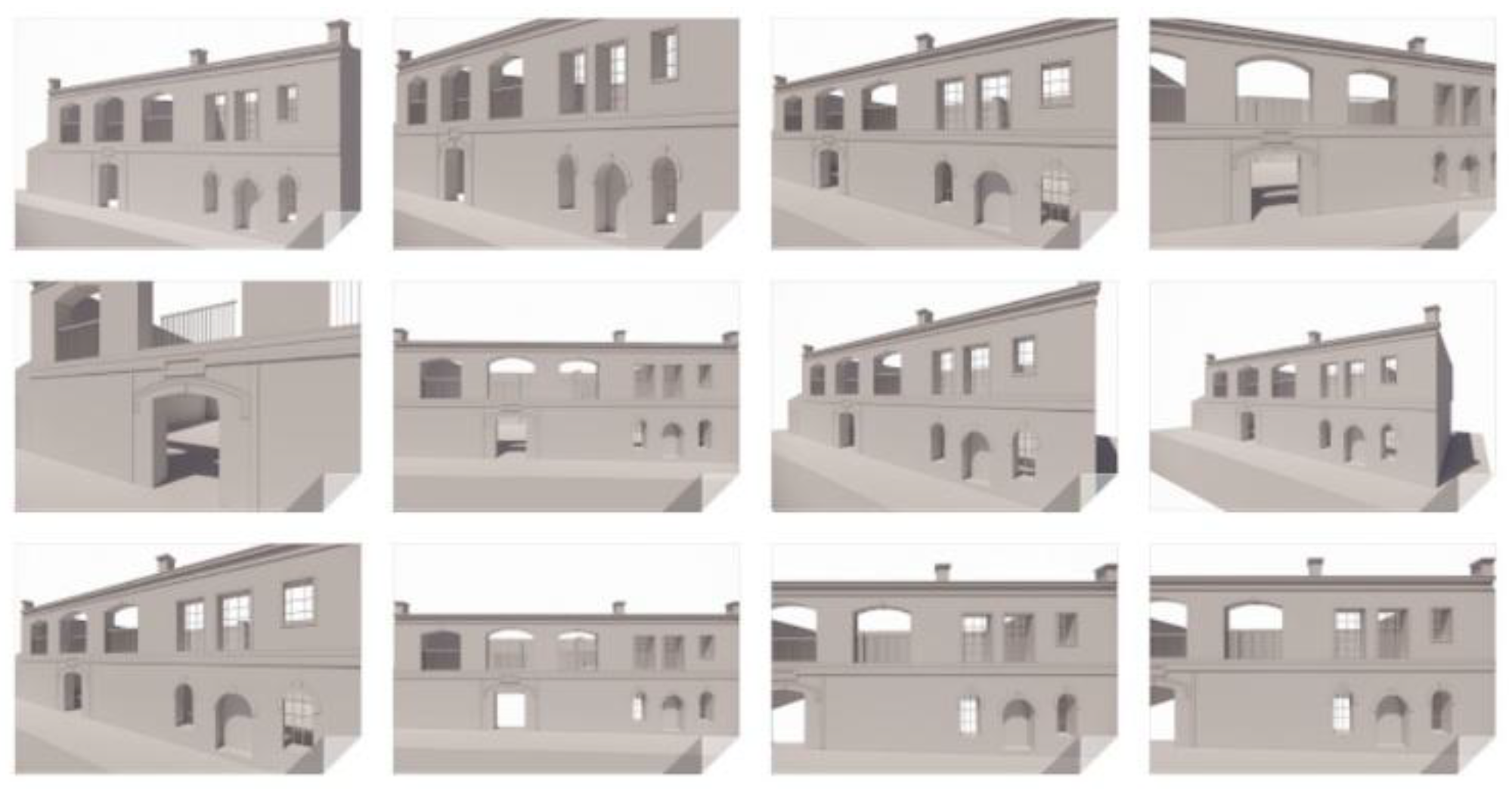

The methodology followed by the author, in consultation with professional peers and through exhaustive historic research, was very similar for the 3D reconstruction of the synagogue Aragon in Kastoria.

Built in 1830, the synagogue was destroyed soon after the deportation of the Jewish community in April 1944. Aerial photographs of 1945 and 1968 show many ‘voids’ in the Jewish quarter – Jewish homes being confiscated and demolished – with the synagogue building clearly missing in 1968. A topographic plan of the Jewish quarter of Kastoria dated from 1965, commissioned by KISE, provides a fairly accurate footprint of the synagogue building, as related to the adjacent (Jewish) properties.

When the author was commissioned to create a 3D digital model and rendering of the interior and exterior of the synagogue for an exhibition at the Jewish Museum of Thessaloniki, the existing sources were limited, however, proved enough. An earlier schematic reconstruction by the late architect Panos Tsolakis, had been published in 1994.

19 In addition, a film by Sam Elias during the visit of Bocko Mayo to Kastoria in 1935 or 1936,

20 after it was processed through screen shots into a collage image of the synagogue façade, it provided a very accurate basis for the digital reconstruction of the synagogue front façade. The topographic plan enabled a fairly accurate reconstruction of the footprint of the synagogue. Finally, the film and the few surviving photographs of the synagogue interior and exterior, offered enough evidence for the reconstruction at a high level of precision. Primarily, maintaining the correct proportions and relationships among the building parts (

Figure 10).

The 3D model reconstruction required exhausting all existing fragments of visual evidence, with the goal to represent as accurately as possible a building that was demolished, without leaving behind any physical evidence. Digital technology and publicly available archival materials over the internet, enabled this task to be completed successfully and within a very limited timeframe.

4. Discussion

This study underscores the transformative potential of digital technology in reconstructing, preserving and representing Greek synagogues, many of which exist today only in fragmented documentation or personal recollections. The research demonstrates that CAD reconstructions, digital modeling, and virtual reality applications can effectively bridge the gap between historical documentation and contemporary representation. These tools, combined with physical in-situ surveys or the same or similar buildings, have enabled a level of precision despite the fact that physical remnants are scarce or lost.

One of the most significant contributions of this study is the integration of diverse historical sources—ranging from historic surveys, to archival documents and photographic evidence to survivor testimonies—into a unified reconstruction process assisted by digital tools. These tools prove also helpful, when a physical restoration is undertaken. The rediscovery and digitization of the Shemtov Samuel archive proved invaluable in recovering visual evidence on synagogues with limited prior documentation, such as the Beth El synagogue in Kavala and the pre-war synagogue of Volos (Messinas, 2024). This methodology aligns with international best practices in digital heritage preservation, as seen in the reconstruction of Aleppo’s Great Synagogue based primarily on a photographic survey of the synagogue prior to its destruction (Back to Aleppo, 2022).

Beyond architectural accuracy, the findings highlight the broader cultural and educational value of these reconstructions. Digital heritage initiatives not only serve as academic resources triggering the inquisitive mind of future researchers, but also foster public engagement through physical and virtual exhibitions, storytelling, and immersive VR experiences. The Jewish Museum of Thessaloniki’s exhibitions – combining traditional and digital methods - demonstrate the growing public interest in reclaiming lost cultural heritage and exploring the invisible layers of the urban landscape. Moreover, these reconstructions hold significant potential for urban planning, informing future conservation strategies, and integration of remaining and lost historic synagogues by reintegrating them into their urban context through urban planning and design.

Looking ahead, future research could explore more advanced digital tools, such as augmented reality (AR) applications, allowing users to experience these synagogues in both their original urban environments via mobile devices in-situ. Additionally, AI-driven architectural reconstruction could explore machine learning to reconstruct lost heritage, or refine missing architectural details, to enhance the fidelity of digital reconstruction models. A comparative study with other lost Jewish heritage sites in Europe—such as in Italy, Turkey or the Balkans—could also offer valuable methodological insights in recapturing the regional wealth of architectural styles, all connected through the same or similar architectural and construction traditions.

Finally, deeper collaboration with Greek Jewish communities and Holocaust descendants, could further enrich these digital reconstructions with oral histories and personal testimonies. Integrating these narratives would not only enhance the users’ historical experience but also create a powerful emotional connection between contemporary audiences and Greece’s lost Jewish heritage.

5. Conclusions

Since the beginning of the survey and study of the synagogues of Greece by the author in 1993, the project has been greatly assisted and further enhanced by the use of digital tools in drafting, storing, rendering and creating 3D models, of in-situ surveys and visual archival materials made available in archives and individual collections around the world. They enabled the author to reconstruct with great detail, not only surveyed – before being demolished - synagogues, but also synagogues that have been demolished before the beginning of the project. Some synagogue documentation was unexpectedly revealed though the Samuel archive, which was unknown for many years. The research and reconstruction process and methodologies developed by the author, also enabled him to undertake architectural commissions towards the physical historic restoration of the actual buildings, confidently proposing sometimes bold interventions, backed and justified by historic facts.

The field of the study of the synagogues of Greece, which was substantially developed by the author during the past three decades, has entered a new trajectory. New interest in the Greek Jewish heritage, and the increasing dissemination of the new knowledge in publications and exhibitions, has brought to light new materials that enrich the existing research and perception of these synagogues, while combined with new technologies, open new opportunities for future research and experimentation. Through digitization, this data is made accessible, and through dissemination contributes in both informing and triggering the public in learning about this nearly lost heritage and young researchers to pursue further study.

Funding

I take this opportunity to thank the institutions and grant programs that have supported my research and publications over the years (1993-today), among them, Getty Grant Program, World Monuments Fund, Graham Foundation, Kress Foundation, Vicky Safra, Memorial Foundation for Jewish Culture and many others.

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

I also thank my draftswoman Conny Naim, for assisting in the digital drafting and 3D modeling of the synagogue reconstruction of Aragon synagogue in Kavala, under my direct supervision, between February and March 2025.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AI |

Artificial Intelligence |

| AR |

Augmented Reality |

| CAD |

Computer-Aided Design. |

| KISE |

Central Board of Jewish Communities of Greece. |

| OPAIE |

The organization for the restitution of Greek Jewry after the Second World War. |

| VR |

Virtual Reality |

| 3D |

Three-dimensional (rendering or model). |

References

- Archaeological Registry of Greece. Ministry of Culture: Athens, Greece, 2022. https://www.arxaiologikoktimatologio.gov.gr/ (Accessed December 2024).

- Back to Aleppo: A Virtual-Reality Tour of the Great Synagogue, Israel, 2022. https://www.imj.org.il/en/exhibitions/back-aleppo (Accessed December 2024).

- Ben Maimon, M. Mishneh Torah (Hebrew). Am Olam, Tel Aviv, 1968.

- Bowman, S. The Jews of Byzantimum (1204-1453). Tuscaloosa, Alabama, 1985.

- Dlin, E. Synagogues of Salonika: Community and Continuity at Yad Vashem, Jerusalem, Israel. Kol haKEHILA, online, 2000. https://www.yvelia.com/kolhakehila/archive/sites/salonika/salonika_syn_exhib_yad_vashem_006.htm (Accessed December 2024).

- Elias, S. Synagogue in prewar Kastoria. US Holocaust Memorial Museum collection, Accession Number: 2017.323, RG Number: RG-60.0144, Film ID: 4268, Washington, DC, 1935. https://collections.ushmm.org/search/catalog/irn562761 (Accessed April 2025).

- Halakhot Beit Knesset, 150. Bar Ilan University. https://u.cs.biu.ac.il/~wisemay/shulhan-aruch/s7.pdf (Accessed March 2025).

- Karababas, A. In the Traces of the Jews of Greece: The Jews of Greece and their Presence in Greece from Antiquity until Today. Psichogios, Athens, Greece, 2022.

- Konstantinis, M. The Jewish Communities of Greece after the Holocaust: Insights from the Reports of Kanaris D. Konstantinis, 1945. Athens, Greece, 2015.

- Lupo, G. The Jewish Community of Arta, 2023. https://vimeo.com/874492101/f0049815ac (visited December 2024).

- Lupo, G. The Jewish Community of Didimoteicho, 2023. https://vimeo.com/828605804 (Accessed December 2024).

- Lupo, G. The Jewish Community of Kastoria, 2023. https://vimeo.com/892356758?share=copy (Accessed December 2024).

- Lupo, G. The Last Jew of Kavala, 2023. https://youtu.be/SizVgSg1QGE?si=T9-qYi6VG0JW1JlK (Accessed December 2024).

- Mazur, B. Studies on Jewry in Greece. Hestia, Athens, Greece, 1935.

- Messinas, E. The Synagogues of Greece: A Study of Synagogues in Macedonia and Trace: With Architectural Drawings of all Synagogues of Greece, Foreword by Samuel D. Gruber. KDP: Seattle, USA, 2022.

- Messinas, E. The Synagogue (Greek). Infognomon Editions: Athens, Greece, 2022. Published in English as Messinas, E. The Syn agogue. KDP: Seattle, USA, 2025.

- Messinas, E. To Synagoi (Greek). Infognomon Editions: Athens, Greece, 2023.

- Messinas, E. To Kal (Greek). Infognomon Editions: Athens, Greece, 2024.

- Missailidis, A. A Jewish Synagogue of Diaspora in Chios and the Epigraphic Evidence (Greece). Proceedings of the International Symposium in Honour of Emeritus Professor George Velenis in Thessaloniki, Athens, Greece, 2017, p. 1385-1410.

- Pinkerfeld, J. The Synagogues of Italy: Their Architectural Development since the Renaissance (Hebrew). Goldberg’s Press, Jerusalem, Israel, 1954.

- Rau, T. and Oberhuber, S. Materials Matters: Developing Business for a Circular Economy. Routledge, London, UK, 2023.

- Samuel, S. Synagogues of Greece (Greek). Unpublished lecture at the Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, Thessaloniki, Greece, 1961.

- Stavroulakis, N., DeVinney, T. Jewish Sites and Synagogues in Greece. Talos Press, Athens, Greece, 1992.

- Tsolakis, P. The Jewish Quarter of Kastoria: History, Town Planning and Architecture (Greek). Thessaloniki, 1994.

| 1 |

Bowman, 1985. |

| 2 |

Mazur, 1935, p. 30. |

| 3 |

Missailidis, 2017, p. 1385-1410. |

| 4 |

Pinkerfeld, 1954. |

| 5 |

Stavroulakis, 1992, p. 144. |

| 6 |

Messinas, 2024, pp. 192-198, 200-201. |

| 7 |

Ben Maimon, 50. |

| 8 |

Messinas, 2023, pp. 286-288. |

| 9 |

Halakhot, 150. |

| 10 |

Karababas, 2022, p. 36-37. |

| 11 |

Messinas, 2023, pp. 285-288. |

| 12 |

Konstantinis, 2015, pp. 57-138. |

| 13 |

Starting in 2022 with "The Synagogue" (published in Greek in 2022, and in English in 2025). |

| 14 |

Samuel, 1961. |

| 15 |

Messinas, 2024. |

| 16 |

Rau, 2023, pp. 122-123. |

| 17 |

Dlin, 2000. |

| 18 |

Messinas, The Synagogue, 2022, pp. 265-272. |

| 19 |

Tsolakis, 1994. |

| 20 |

Elias, 1935. |

Figure 1.

The mosaic floor of the synagogue in Aegina (c.4th CE) located at the Archaeological Museum of Aegina (© Elias V. Messinas).

Figure 1.

The mosaic floor of the synagogue in Aegina (c.4th CE) located at the Archaeological Museum of Aegina (© Elias V. Messinas).

Figure 2.

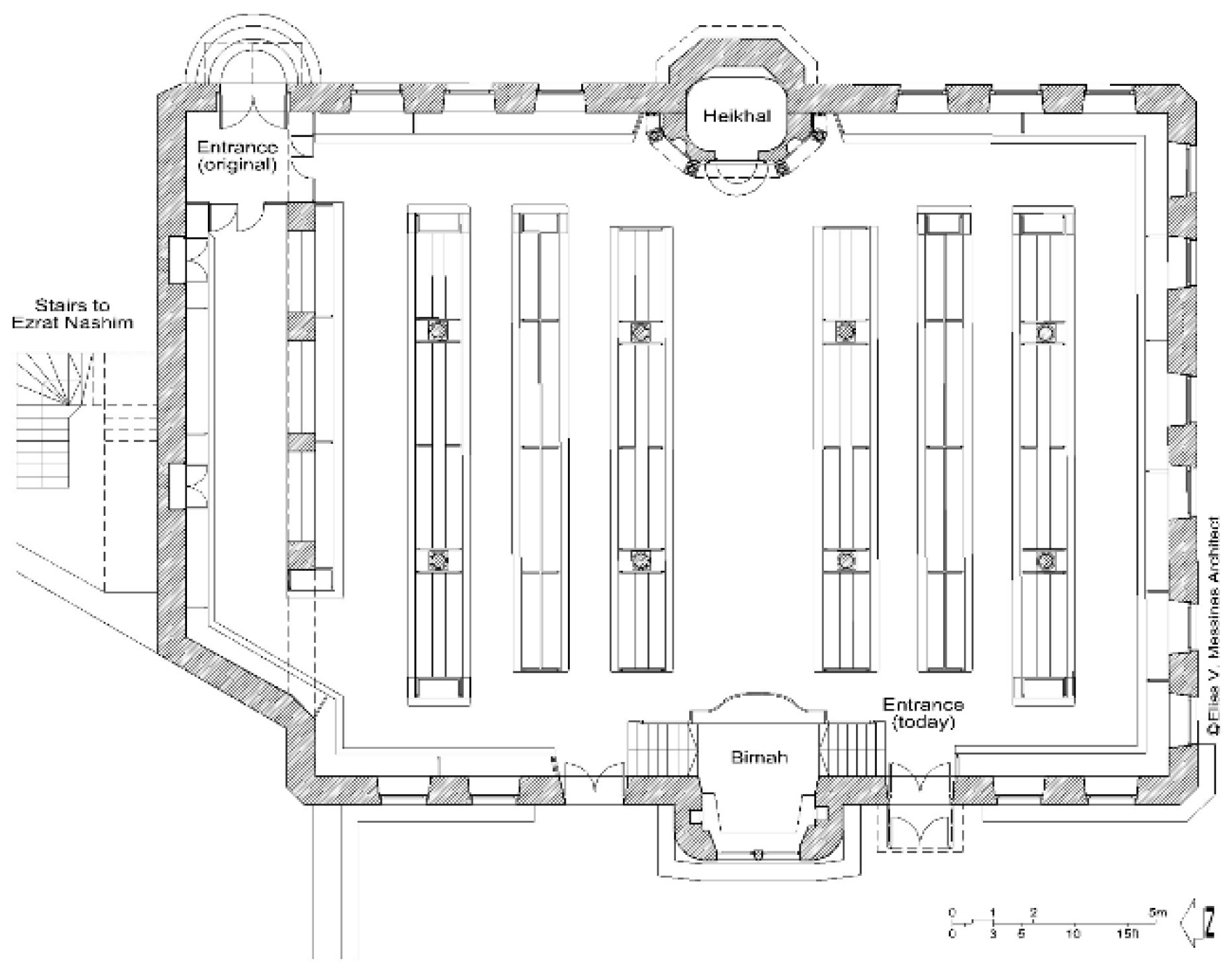

Floor plan of the synagogue Kahal Kadosh Yashan (1826) in the Old city (intra muros) in Ioannina, based on the survey by the author in May 1995. The Holy Ark and Bimah are in a bipolar arrangement (© Elias V. Messinas).

Figure 2.

Floor plan of the synagogue Kahal Kadosh Yashan (1826) in the Old city (intra muros) in Ioannina, based on the survey by the author in May 1995. The Holy Ark and Bimah are in a bipolar arrangement (© Elias V. Messinas).

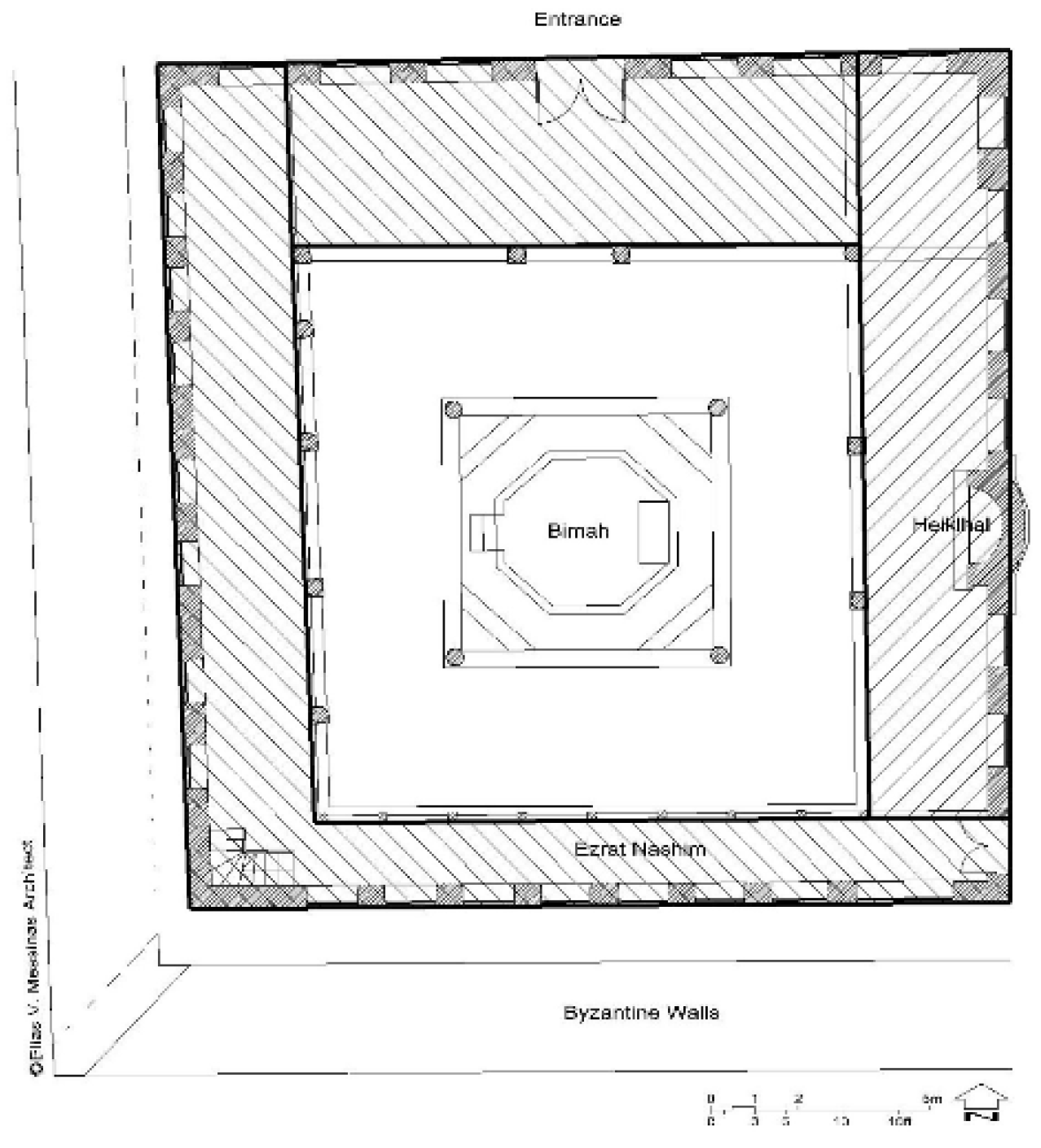

Figure 3.

Floor plan of the synagogue Kahal Kadosh Shalom (1575) in the Old City of Rhodes, based on the survey by the author in August 1996. The double Holy Ark is a unique typology found in Rhodes in both this synagogue and synagogue Kahal Kadosh Gadol (late 1400s), which was also surveyed by the author in November 2024 (© Elias V. Messinas).

Figure 3.

Floor plan of the synagogue Kahal Kadosh Shalom (1575) in the Old City of Rhodes, based on the survey by the author in August 1996. The double Holy Ark is a unique typology found in Rhodes in both this synagogue and synagogue Kahal Kadosh Gadol (late 1400s), which was also surveyed by the author in November 2024 (© Elias V. Messinas).

Figure 4.

Floor plan of the synagogue Beth El (c.19th) in Komotini (intra muros), based on the survey by the author in October 1993, prior to its demolition in 1994. The synagogue floor plan was developed in stages, as was originally identified by the author and verified by the archaeologists who studied the still-visible foundations of the synagogue. The three phases of the expansion of the original ‘Ottoman type’ square core, were (a) to the east (the wall of the Holy Ark) and (b) in a Greek ‘Π’ shape to the NSW to provide more space for the ezrat nashim (women’s gallery) (© Elias V. Messinas).

Figure 4.

Floor plan of the synagogue Beth El (c.19th) in Komotini (intra muros), based on the survey by the author in October 1993, prior to its demolition in 1994. The synagogue floor plan was developed in stages, as was originally identified by the author and verified by the archaeologists who studied the still-visible foundations of the synagogue. The three phases of the expansion of the original ‘Ottoman type’ square core, were (a) to the east (the wall of the Holy Ark) and (b) in a Greek ‘Π’ shape to the NSW to provide more space for the ezrat nashim (women’s gallery) (© Elias V. Messinas).

Figure 5.

Digital map of Thessaloniki, enriched with a layer of points and polygons of Jewish sites, marking the exact location of synagogues, schools, institutions, the ancient Jewish cemetery and Jewish quarters throughout the city fabric, for an exhibition on the synagogues of Thessaloniki at the Jewish Museum of Thessaloniki in 2023. This digital map formed the basis for the enrichment of the Archaeological Registry of the Ministry of Culture of Greece with Jewish sites, based on the research by the author (© Elias V. Messinas – basis map by Google Maps).

Figure 5.

Digital map of Thessaloniki, enriched with a layer of points and polygons of Jewish sites, marking the exact location of synagogues, schools, institutions, the ancient Jewish cemetery and Jewish quarters throughout the city fabric, for an exhibition on the synagogues of Thessaloniki at the Jewish Museum of Thessaloniki in 2023. This digital map formed the basis for the enrichment of the Archaeological Registry of the Ministry of Culture of Greece with Jewish sites, based on the research by the author (© Elias V. Messinas – basis map by Google Maps).

Figure 6.

A rare photograph of the interior of the synagogue in Didimoticho in 1960 by architect Shemtov Samuel (1939-2009). The synagogue was in use by the Christian Home organization as a Sunday school until it was abandoned and demolished in the 1984. The synagogue was surveyed by Samuel in 1960 and the in-situ remains of the synagogue by the author in April 1994. The wooden benches are the original benches of the synagogues, used by the Jewish community before the Holocaust (© Semtov Samuel Family Archive – Elias V. Messinas Archive).

Figure 6.

A rare photograph of the interior of the synagogue in Didimoticho in 1960 by architect Shemtov Samuel (1939-2009). The synagogue was in use by the Christian Home organization as a Sunday school until it was abandoned and demolished in the 1984. The synagogue was surveyed by Samuel in 1960 and the in-situ remains of the synagogue by the author in April 1994. The wooden benches are the original benches of the synagogues, used by the Jewish community before the Holocaust (© Semtov Samuel Family Archive – Elias V. Messinas Archive).

Figure 7.

The digitization of the synagogue Kahal Shalom in Kos (1935) surveyed by the author in August 1996. The synagogue was again surveyed by the author in April 2022 prior to the restoration of the interior of the synagogue by the author (© Elias V. Messinas).

Figure 7.

The digitization of the synagogue Kahal Shalom in Kos (1935) surveyed by the author in August 1996. The synagogue was again surveyed by the author in April 2022 prior to the restoration of the interior of the synagogue by the author (© Elias V. Messinas).

Figure 8.

Demolition of the synagogue in Volos in 1960. This synagogue was built from 1865 to 1870. The synagogue was partially destroyed by the Nazis at the time of the deportation of the Jews of Volos in March 25, 1944 (some sources place the explosion of the synagogue in 1943). The synagogue was reconstructed in 1948 and damaged again in the earthquake of 1955. In 1960 the synagogue was demolished to clear the site for the construction of a new synagogue, built of reinforced concrete in 1960 (© Semtov Samuel Family Archive – Elias V. Messinas Archive).

Figure 8.

Demolition of the synagogue in Volos in 1960. This synagogue was built from 1865 to 1870. The synagogue was partially destroyed by the Nazis at the time of the deportation of the Jews of Volos in March 25, 1944 (some sources place the explosion of the synagogue in 1943). The synagogue was reconstructed in 1948 and damaged again in the earthquake of 1955. In 1960 the synagogue was demolished to clear the site for the construction of a new synagogue, built of reinforced concrete in 1960 (© Semtov Samuel Family Archive – Elias V. Messinas Archive).

Figure 9.

Reconstruction laser-cut model in a scale 1:20, of the synagogue Beth Shaul of Thessaloniki by Italian architect Vitaliano Poselli (1838-1918) built for the Modiano family in 1898. The synagogue was demolished by the Nazis in 1943, after the deportation of the Jewish community. The synagogue served as the central synagogue of Thessaloniki after Talmud Torah HaGadol, the former central synagogue was destroyed in the fire of 1917. The model was based on a detailed architectural reconstruction of the synagogue by the author in 1996 based on city plans and historic photographs. The model was exhibited at Yad Vashem Valley of the Communities in Jerusalem in 1999-2000 at an exhibition based on the research of the author. The model colors were based on an interview of the late Freddy Abravanel, to the author, who grew up in Thessaloniki and his family prayed in the synagogue (© Elias V. Messinas).

Figure 9.

Reconstruction laser-cut model in a scale 1:20, of the synagogue Beth Shaul of Thessaloniki by Italian architect Vitaliano Poselli (1838-1918) built for the Modiano family in 1898. The synagogue was demolished by the Nazis in 1943, after the deportation of the Jewish community. The synagogue served as the central synagogue of Thessaloniki after Talmud Torah HaGadol, the former central synagogue was destroyed in the fire of 1917. The model was based on a detailed architectural reconstruction of the synagogue by the author in 1996 based on city plans and historic photographs. The model was exhibited at Yad Vashem Valley of the Communities in Jerusalem in 1999-2000 at an exhibition based on the research of the author. The model colors were based on an interview of the late Freddy Abravanel, to the author, who grew up in Thessaloniki and his family prayed in the synagogue (© Elias V. Messinas).

Figure 10.

Digital reconstruction of the former synagogue Aragon in Kastoria. A detailed reconstruction based on archival and previously published architectural drawings by the late architect Panos Tsolakis, published in 1994, and a film by Sam Elias of 1935/6. A topographic plan of Jewish properties of 1965 provided a fairly accurate reconstruction of the footprint of the synagogue. The model will be exhibited in the exhibition on the Jewish Community of Kastoria at the Jewish Museum of Thessaloniki (April 2024) (© Elias V. Messinas).

Figure 10.

Digital reconstruction of the former synagogue Aragon in Kastoria. A detailed reconstruction based on archival and previously published architectural drawings by the late architect Panos Tsolakis, published in 1994, and a film by Sam Elias of 1935/6. A topographic plan of Jewish properties of 1965 provided a fairly accurate reconstruction of the footprint of the synagogue. The model will be exhibited in the exhibition on the Jewish Community of Kastoria at the Jewish Museum of Thessaloniki (April 2024) (© Elias V. Messinas).

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).