1. Introduction

The physical visit to real architectural spaces is considered an unparalleled experience in which the multitude of stimuli and sensations received are very difficult to reproduce by virtual systems. However, the generation of three-dimensional models of architecture is still interesting, being especially relevant in the case of the disappeared architecture, since they are the only way in which its configuration and characteristics can be observed.

There are different techniques that have been developed in recent decades in the field of Human Computer Interaction (HCI) and Computer Graphics around experimenting with digital environments and objects. The most widespread are VR [1 & 2] and AR [

3]. These techniques are generated by computers and the use of specific devices that allow users to be provided with immersive experience in a simulated (VR) or semi-simulated (AR) world. However, more complex systems such as the Cave Environment have been developed [

4].

These technologies offer a new way of perceiving our world, and we are constantly working to find the most real experience possible and/or stimulate a better experience of interaction with the computer. This way of interacting with the environment and objects has multiple applications in various fields such as the military, health, video games, museums [

5], education [

2] or Architectural Heritage. The latest developments in these technologies are based on the use of the cloud and greater ease of use that enables better usability and accessibility to the technology by non-expert users.

The most common VR and AR case studies are archaeological sites where historical elements need to be reconstructed by CAD systems based on historical information, such as the archaeological site of Pausilypon in Naples (Italy) where a hypothetical CAD reconstruction of a maritime villa from the Roman period was carried out and concluded that immersive systems could increase the interest of non-expert users in the site studied, such as the study by Bakar et al., on user requirements for VR exposures [

6]. Immersive systems offer the possibility of visualizing hypothetical reconstruction [

7]. In addition, the fact that the 3D reconstruction of the place has been developed implies an advance in the pedagogical goals of cultural heritage studies [

8], specifically in its application to architectural heritage, and its relationship with both urban environments [

9] and the landscape [

10].

Sometimes the role of VR or AR in cultural heritage is closely related to tourism objectives, such as the Roman theatre of Byblos [

11]. In these experiences, it is interesting to have studies that assess the public’s reactions [

12].

Augmented Reality (AR) has proven to be a key tool in education, research, and the dissemination of architectural heritage, enhancing spatial understanding and interaction with historical environments. Its implementation in education requires high-quality standards in content and accessibility [

13], while in heritage tourism, it has developed as a strategy to provide immersive experiences and increase visitor engagement [

14,

15]. Additionally, its use in the conservation and digital reconstruction of heritage facilitates its study and dissemination [

16]. However, challenges remain in terms of cost, acceptance, and technological development [

17].

The main objective of this work is the creation of educational materials with various applications, including their use in museums. In this regard, it is relevant to highlight certain aspects of the definition of a museum [

18], which describes it as an institution that serves society by researching, collecting, preserving, interpreting, and exhibiting heritage. Museums must be open to the public, accessible, and inclusive, promoting diversity and sustainability while offering diverse experiences for education, enjoyment, reflection, and the exchange of knowledge.

Another important objective of this work is to ensure the accessibility of the dissemination materials produced. In this case, special consideration has been given to individuals with visual impairments. In this regard, the contribution of Tiflological Museums to society should be acknowledged, such as the ONCE Museum in Madrid, which dedicates one of its halls to architectural monument models [

19].

In addition, it is worth noting the importance of generating inclusive resources to facilitate access to architectural heritage to the widest possible range of people, regardless of their cognitive, visual, auditory and/or motor abilities, in line with the philosophy of inclusive design [

20]. The creation of educational materials for museums plays a key role in fulfilling the mission of these facilities to educate, interpret and engage the visitors. These materials can take a variety of forms, such as interactive exhibits, guided tours, multimedia presentations and even tactile-visual exhibits, all designed to enhance the visitor’s understanding and appreciation of the architectural or cultural heritage being presented. By developing diverse and accessible educational resources, museums can cater to a wide range of learning styles and abilities, ensuring that the knowledge and cultural significance of their collections are effectively communicated to all visitors, while democratizing and expanding access to knowledge.

Accessibility is a crucial aspect of museum education and architectural heritage education, particularly for individuals with visual impairments in the case of this study. The development of tactile models, audio descriptions, and Braille labels are examples of how museums can make their collections more inclusive. Tiflological Museums, such as the ONCE Museum in Madrid, showcase the potential of these approaches by featuring architectural monument models that can be explored through touch. This inclusive approach not only benefits those with visual impairments but also enriches the experience for all visitors by providing multi-sensory engagement with the exhibits. By prioritizing accessibility and inclusiveness in the creation of educational materials, museums can fulfill their role as institutions that serve the entire community, promoting diversity and fostering a deeper understanding of our shared cultural heritage.

Finally, within the scope of this study, it is useful to address at least three major groups of resources that are used primarily in the field of education and museology, among other disciplines. Firstly, it is worth mentioning conventional visual and text resources commonly used. Secondly, digital resources such as Augmented Reality and/or Virtual Reality and, finally, haptic resources [

21,

22].

The work presented is based on a previous work of graphic restitution that has made it possible to define a relevant case of disappeared architecture. It is a work developed with a specific research methodology, which through the study of different documentary sources allows the generation of complete graphic documentation [

23,

24,

25]. Likewise, the work has been based on previous experience from other research studies conducted by the authors [

26,

27,

28].

2. The Study Case

The Earls’ Palace in Oliva was one of the most significant buildings of late Gothic and Renaissance Valencian architecture. Today, only some remnants remain; however, the graphic study and inventory carried out by Egil Fischer and Vilhelm Lauritzen (1919-20) have left behind an extensive collection of sketches, drawings, and photographs [

29,

30]. Built by the Centelles family of Oliva and Nules, construction began in the 14th or early 15th century. The “Roman-style” embellishments made between 1480 and 1536 [

31] are attributed to Serafí de Centelles Riu-Sec (†1536). Among its most distinctive architectural features were its Gothic-Renaissance portals and windows [

32], as well as its polychrome wooden coffered ceilings and beams, typical of the period.

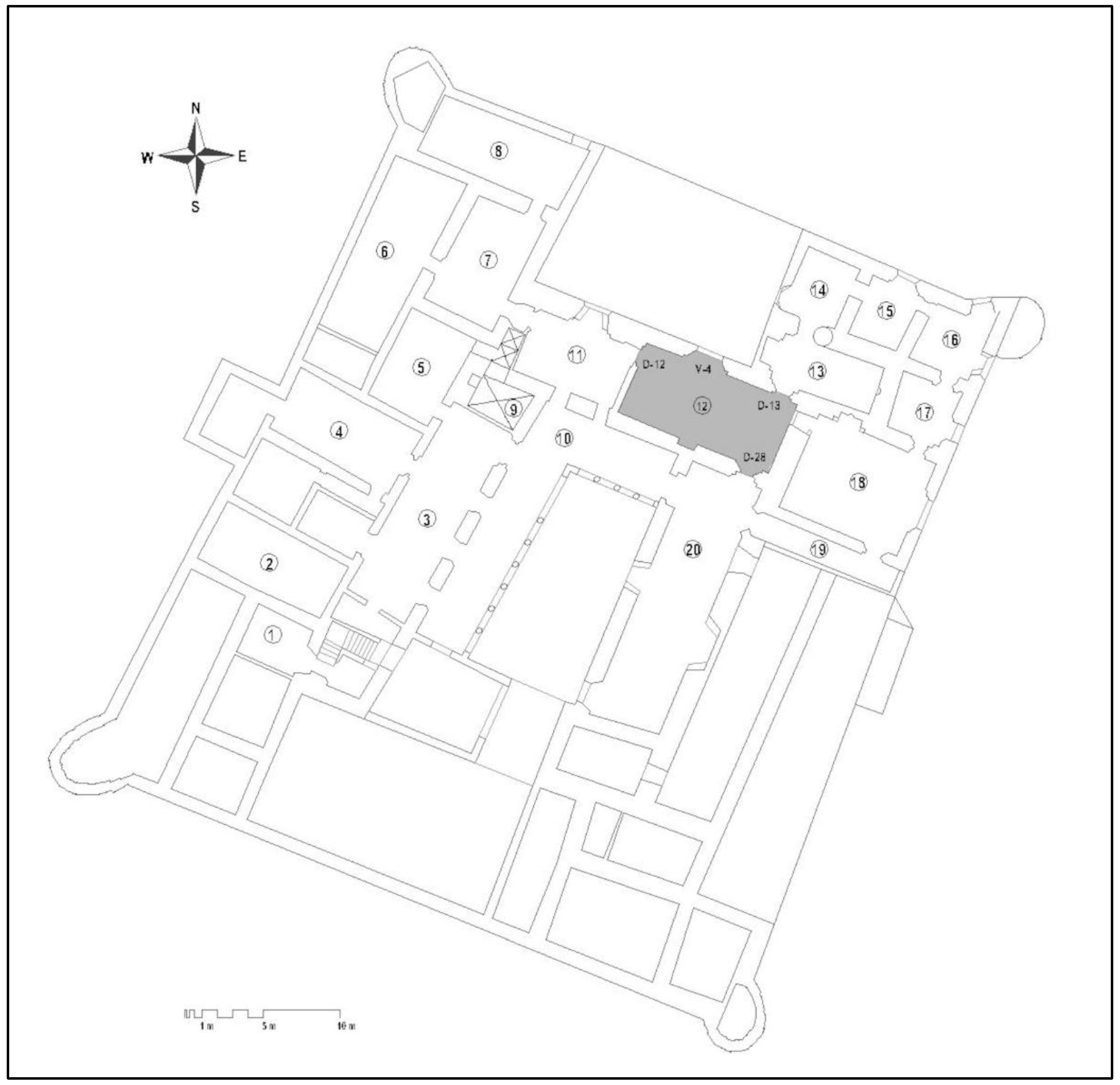

The Golden Hall [

33], or Room 12 according to Fischer’s inventory, was located on the first floor. With its late Gothic-style portals and polychrome rhomboidal coffered ceiling, it was, along with the Hall of Arms, one of the most remarkable halls in the palace (see

Figure 1 and

Figure 2). It was almost entirely documented by the Danish architects [

35].

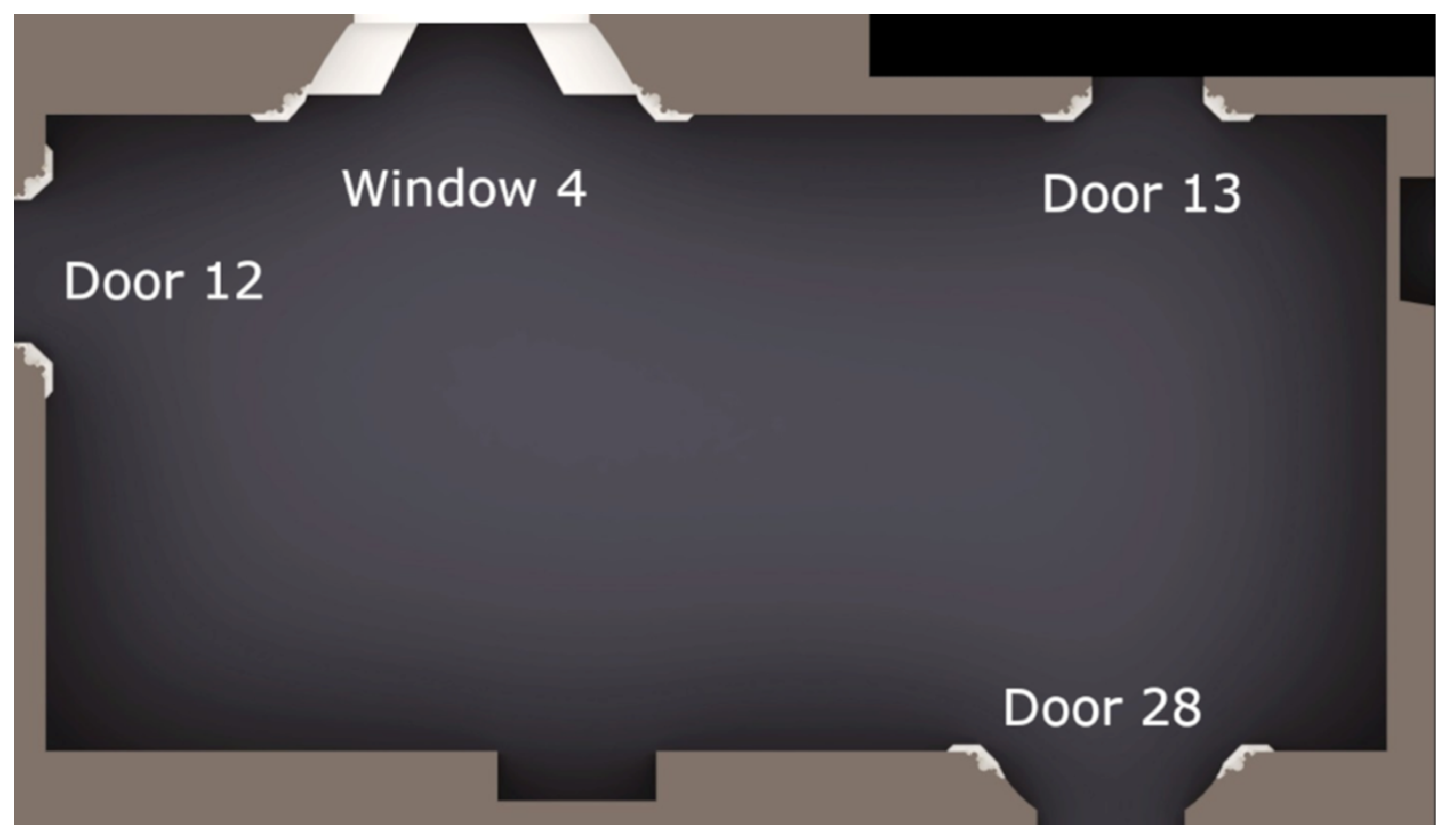

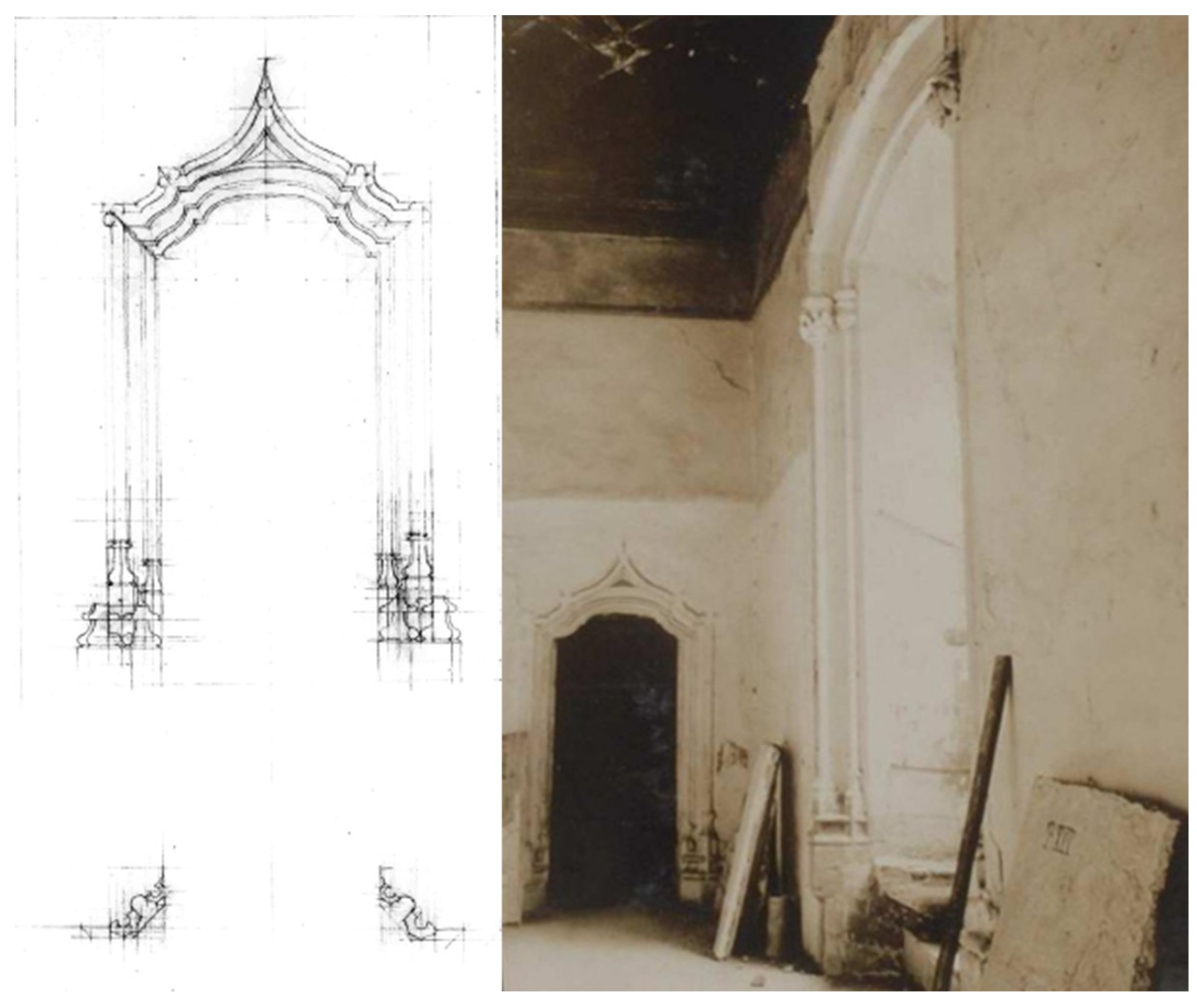

2.1. Portals

The three portals in the Golden Hall (Door 12, Door 13, and Door 28) display distinct late Gothic features in their arches and the bases from which the main moldings emerge. These bases consist of two small columns with varying diameters and a convex molding that shapes both the jambs and arches.

Doorway 12 is made up of a mixtilinear carpanel arch on its lower surface, transitioning into a mixtilinear flamboyant Gothic on its upper surface. The convex molding does not maintain a consistent diameter throughout the arch, introducing additional complexity that was accurately defined through its 3D layout. The initial documentation prepared by architects Fischer and Lauritzem, used for the reconstruction of this portal, consists of two blueprints (LA1138 and LA1139) and a photograph (Picture Nr. 77, Large Photo Album, p. 17A) [

34] (see

Figure 3).

Doorway 13 features a depressed trilobed arch with moldings similar to those of Doorway 12. The documentation used for the reconstruction of this portal consists of two blueprints (LA1145 and LA1146) and a photograph (picture Nr. 63, Large Photo Album, p. 14R) [

34] (see

Figure 4).

Doorway 28 has a depressed arch on its lower surface, transitioning into a pointed arch on its upper surface with moldings consistent with the other portals. The documentation used for the reconstruction of this portal consists of two blueprints (LA1143 and LA1144) and a photograph (picture Nr. 64, Large Photo Album, p. 14R) [

34] (see

Figure 5).

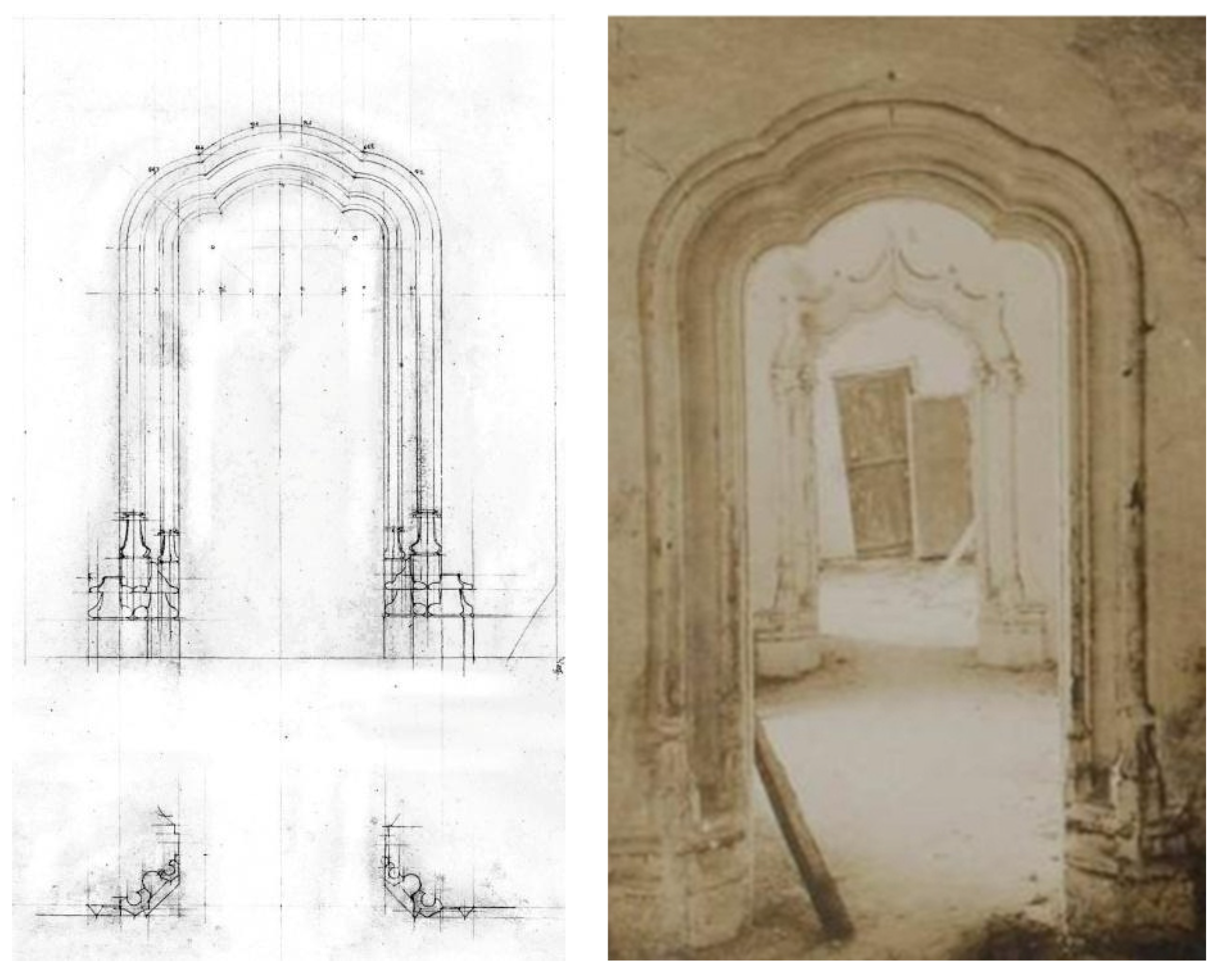

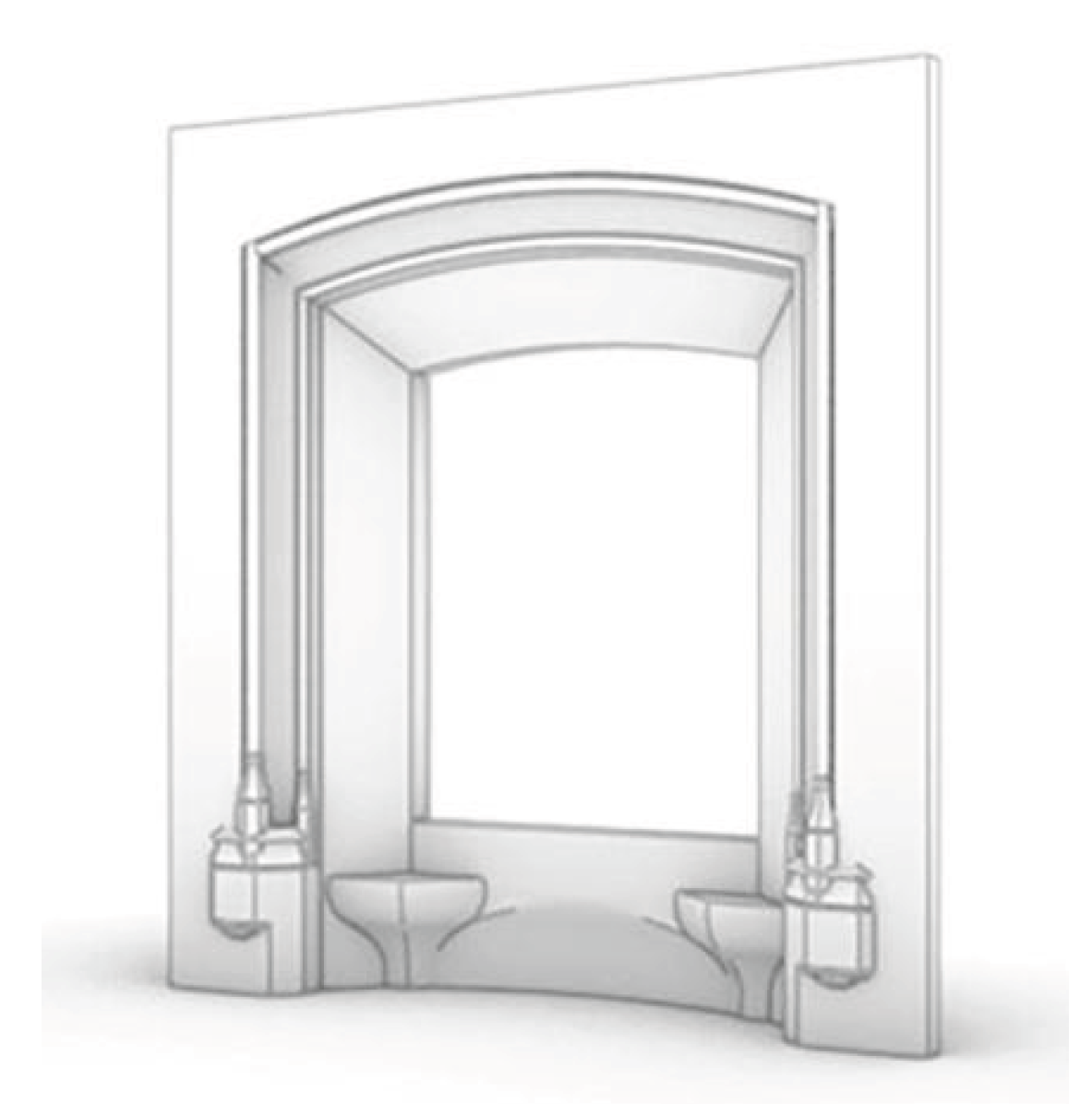

2.2. Window

Window W-4 is significantly taller than the portals and features a depressed arch. Its main moldings are identical to those of the portals with one key distinction: its bases do not originate from the flooring but instead rise from the wall supported by a crown-shaped base. The columns are adorned with capitals featuring vegetal and zoomorphic decorations. The most distinctive feature of this window, however, is its

festejadors, a built-in stone or masonry bench located on the interior sides of the window, characteristic of Mediterranean Gothic architecture. These architectural elements were commonly found in palaces and noble residences in regions such as Catalonia and Valencia during the late Gothic and first Renaissance. The documentation used for the reconstruction of the window consists of two blueprints (LA1196 and LA1197) and three photographs (pictures Nr. 76, 77, and 78, Large Photo Album, p. 17A) [

34] (see

Figure 6).

2.3. Wood-Coffered Ceiling

One of the most striking elements in this architectural space is undoubtedly its rhomboidal coffered ceiling, which bears similarities to those found in other buildings of the era, such as the Generalitat Palace in Valencia and the Palace of the Dukes of Segorbe [

35]. The coffered ceiling was decorated with gold leaf, which is why the room is called the Golden Hall. The documentation used for the reconstruction of the coffered ceiling consists of four blueprints (LA1114, LA1115, LA1116, and LA1117) and a photograph where it can be partially seen (picture 77, Large Photo Album, p. 17A) [

34] (see

Figure 7).

2.4. Flooring

Although the exact design of the flooring is unknown, we know that it was covered with white tiles decorated in blue. To reconstruct its possible appearance, a hypothesis has been developed based on the original flooring found at the Palace’s Tower of the Comare, now in the MAO (see

Figure 8 left) based on the flooring design of the Golden Halls in the Generalitat Palace of Valencia. (see

Figure 8 right). The dimension of the tiles is 12 x 12 cm.

3. Materials and Methods

This section will present the starting materials available, as well as the equipment, graphic tools, and work methodology used for the development of this study.

3.1. Materials

3.1.1. Digital Restitution

As the starting material for this work, a CAD file containing the entire geometry of the Golden Hall in a single 3D model was available.

Based on the original plans by Fischer and Lauritzen, a process of graphic restitution has been carried out by rectifying and scaling the digital files of the original plans and modeling each of the pieces in 3D using CAD, relying on the information contained in these plans and supported by photographs [

34]. To interpret these complex forms, similar facades of contemporary existing buildings have been analyzed. The general dimensions have been obtained from the measurements included in the plans by Fischer and Lauritzen, while the rest were determined by scaling and dimensioning the original plans. Once the elements were individually modeled, they were assembled into a single CAD file (see

Figure 9).

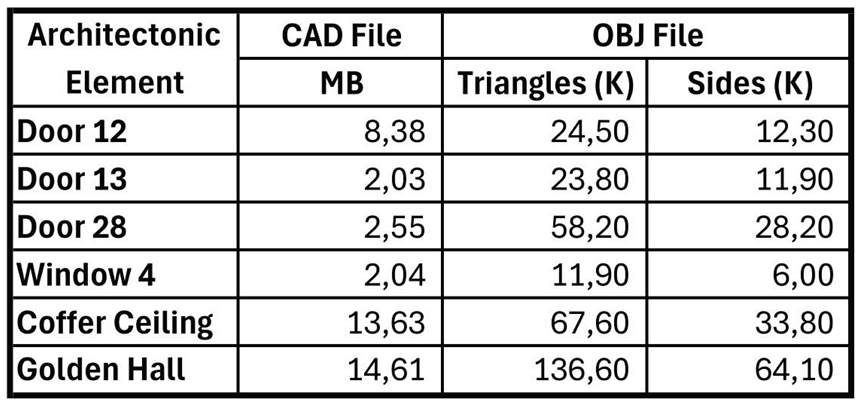

The floor plan measurements of the hall were obtained from the coffered ceiling plan (12.04 x 5.46 m), and to determine the total height of the hall, the blueprint of doorway 12 was used and proportioned according to the height of the doorway in photograph 77, resulting in a total height of 5.60 m. The CAD file was exported to an OBJ format consisting of 136,600 polygons. This complete graphic process was carried out in previous research works [

24,

25,

26] and has been used as the starting material for this study.

3.1.2. AR Tools

For the visualization of architectural elements using AR techniques, the following tools have been used:

3.1.3. VR Tools

For the visualization of the Golden Hall using VR techniques:

Meta Quest 3 VR glasses with the following features: 512 GB storage, 2 RGB cameras with 18 PPD, 8 GB DRAM, 2064 × 2208 pixels per eye display resolution, refresh rate 72,9-120 Hz, 110º horizontal and 96º field of view, 2.2 hours battery life, Wi-Fi connection.

Minimum PC Requirements: Processor, Intel i7 / AMD Ryzen 7; Graphics Card, Nvidia RTX 20 Series* / AMD Radeon RX 6000 Series; Memory, 16 GB DDR4 RAM.

Sketchfab’s online service to upload the 3D model to this website’s server and share it for viewing (Sketchfab, 2025).

3.1.4. Multimodal Panels

For the realization of the multimodal panels, the following tools have been used:

Fused Deposition Modelling (FDM) Ultimaker S3 Printer for the printing of tactile models. Fused Deposition Modeling (FDM) is an economical technique within the domain of rapid prototyping [

38], which facilitates the production of tactile scale models intended for haptic applications.

WIX Platform for the design of the web page. WIX is a platform designed for the creation of websites. It provides tools and features that facilitate the design and construction of web pages, even for individuals lacking advanced technical skills. Users have the option to select from various templates, utilize drag-and-drop elements, and customize multiple aspects of their site’s appearance and functionality through WIX’s user-friendly interface.

3.2. Methods

In this section, the methodology followed for each of the tools applied in this case study will be presented.

3.2.1. Restitution Process

To apply VR or AR, it is necessary to generate a digital environment or object using specific CAD files and software. These digital models allow the space of the room to be shown, with its shape and its general dimensions. Unique elements such as the coffered ceiling, the portals and the large window are also defined. Different finishes have been incorporated: the white of the walls, the gilding of the coffered ceiling and the design of the flooring, as well as the natural lighting through the large window. It has not been possible to incorporate other elements such as furniture, due to the lack of sufficient information. The work has focused exclusively on the reconstruction of the architectural space.

The steps to visualize a model, with AR or VR, in this case have been:

Creation of a CAD model generated with modeling.

Export CAD model to OBJ format.

Conversion, transformation, or editing of CAD models to AR or VR.

Share the 3D model through a host (Sketchfab).

Add textures to the model (walls, flooring and coffer ceiling).

Viewing from a device.

Due to changes in technology, this process could change in the coming years. There is a large body of literature dealing with this issue in the field of architectural heritage, archaeological sites and museums which describe cases and typical workflow to ensure a successful application of these techniques of VR an AR to the architectural heritage. [

39,

40,

41].

3.2.2. AR creation process

AR is a mixed reality that allows reality to be visualized through a device that superimposes additional information, such as the restitution of missing elements.

There are several ways to generate a virtual object or environment using 3D modeling. On one hand, CAD tools such as SolidWorks, Autodesk Revit, Rhinoceros, and SketchUp, among others, can be used. On the other hand, many mobile applications are available for visualizing CAD models in augmented reality (AR). However, Google technologies provide a free method to facilitate the final step of this process for use on Android devices.

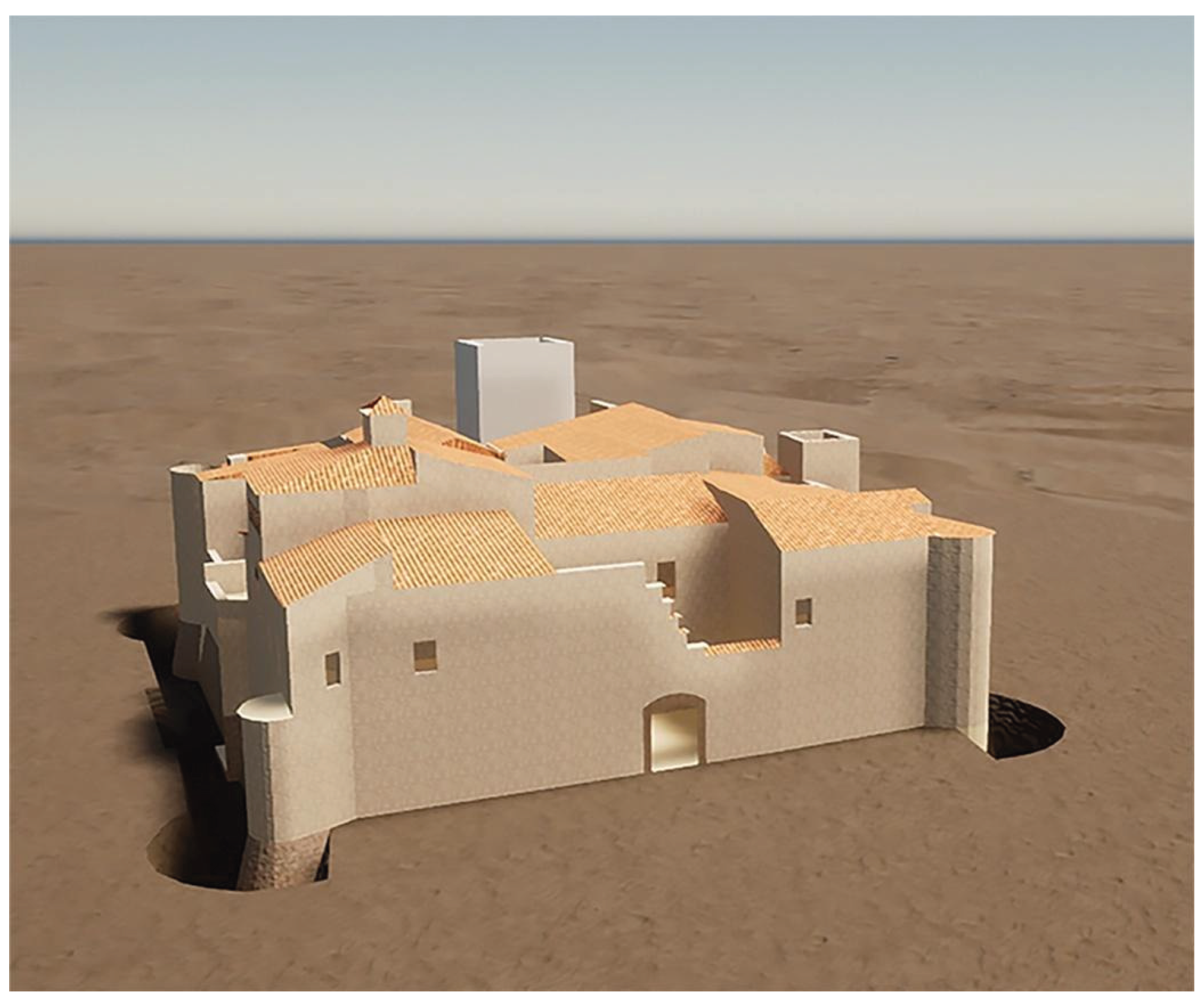

The first step involves starting with a 3D CAD file. In this case, a 3D CAD model of the reconstruction of window W-4 of the Palace of Oliva (see

Figure 10) and the Palace of Oliva (see

Figure 11) have been used.

Once the CAD file is obtained, it must be exported (preferably in an optimized STL format) with fewer than 10,000 polygons to ensure compatibility with the AR system.

Next, the STL file must be uploaded to a Sketchfab (

https://sketchfab.com/) account to be shared on a public host for AR visualization.

The final step is viewing the model using a device, typically a smartphone. In this study, an Android smartphone (v. 8.0.0) with an open-source license of the ARCore Service (

https://developers.google.com/ar/arcore) was used (see Materials section). Finally, the generated link must be opened on the smartphone for visualization (see Results section).

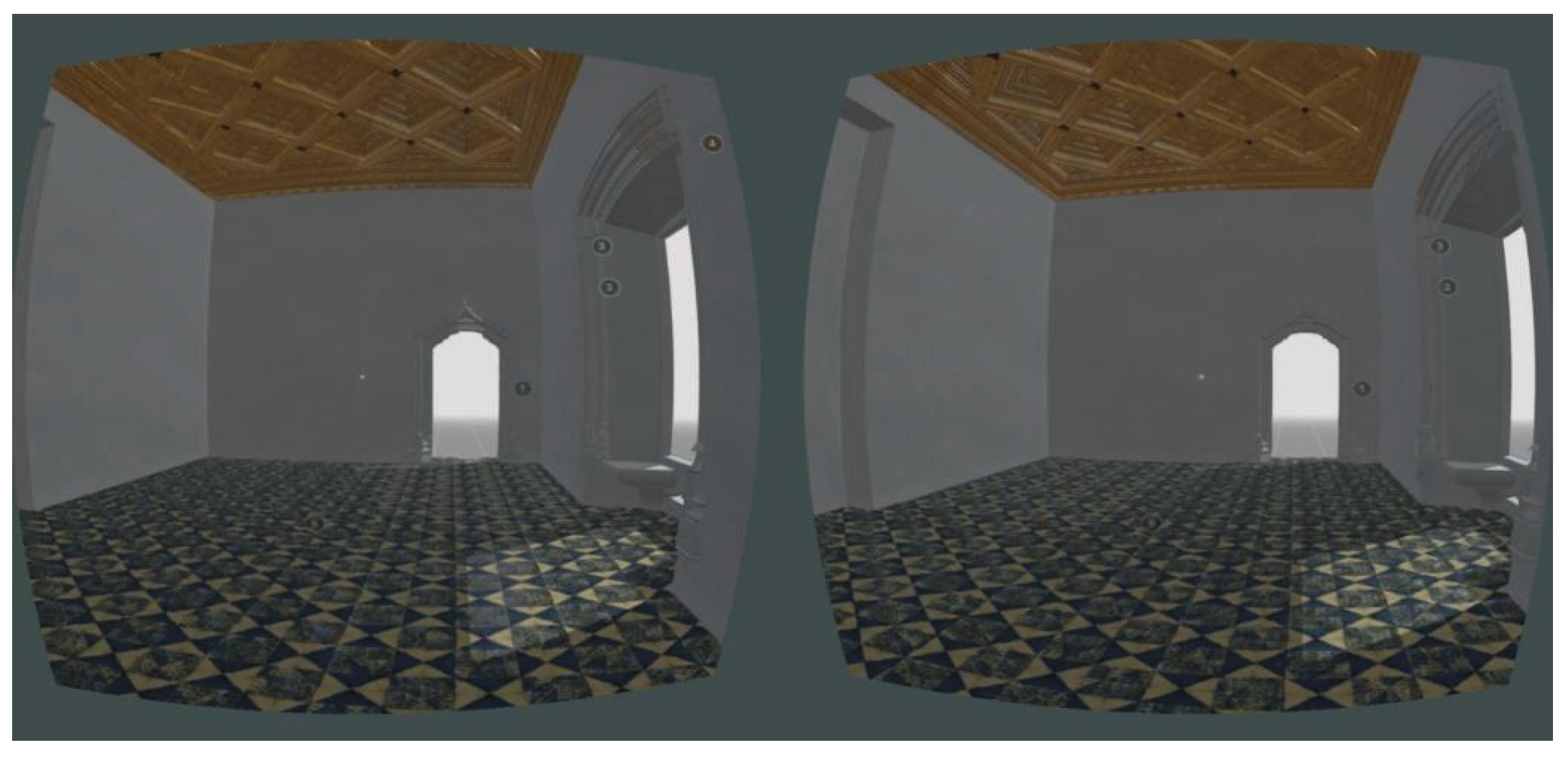

3.2.3. VR Creation Process

VR allows immersive experience inside the room. By means of its actual displacement, it can experience the sensation of space and visualize different points of view.

For VR, one of the simplest methods is to use an online platform dedicated to sharing 3D CAD models, allowing the model to be prepared for free.

The process begins with a 3D CAD file—in this case, a model of the Golden Hall. The three-dimensional model was developed utilizing the computer-aided design software Rhinoceros version 8.

Next, the CAD file must be exported in one of the formats supported by the Sketchfab platform, such as FBX, OBJ, DAE, BLEND, or STL. In this study, an Obj file was utilized, and additionally, it was necessary to include an mtl file containing the material structure data of the maps and textures, as well as the textures employed in the scene configuration.

Then, the uploaded model must be shared on Sketchfab, ensuring that the VR display mode is enabled.

Finally, the 3D model is visualized using a device. In this study, the Meta Quest 3 headset was used (see

Figure 12). However, a simpler alternative is to use a smartphone with a VR Cardboard viewer (see

Figure 13). In this instance, to visualize the model using the Meta Quest 3 VR headset, it was necessary to synchronize the VR headset with the computer via a shared Wi-Fi network. Additionally, the computer must have the appropriate control software from the Meta company installed.

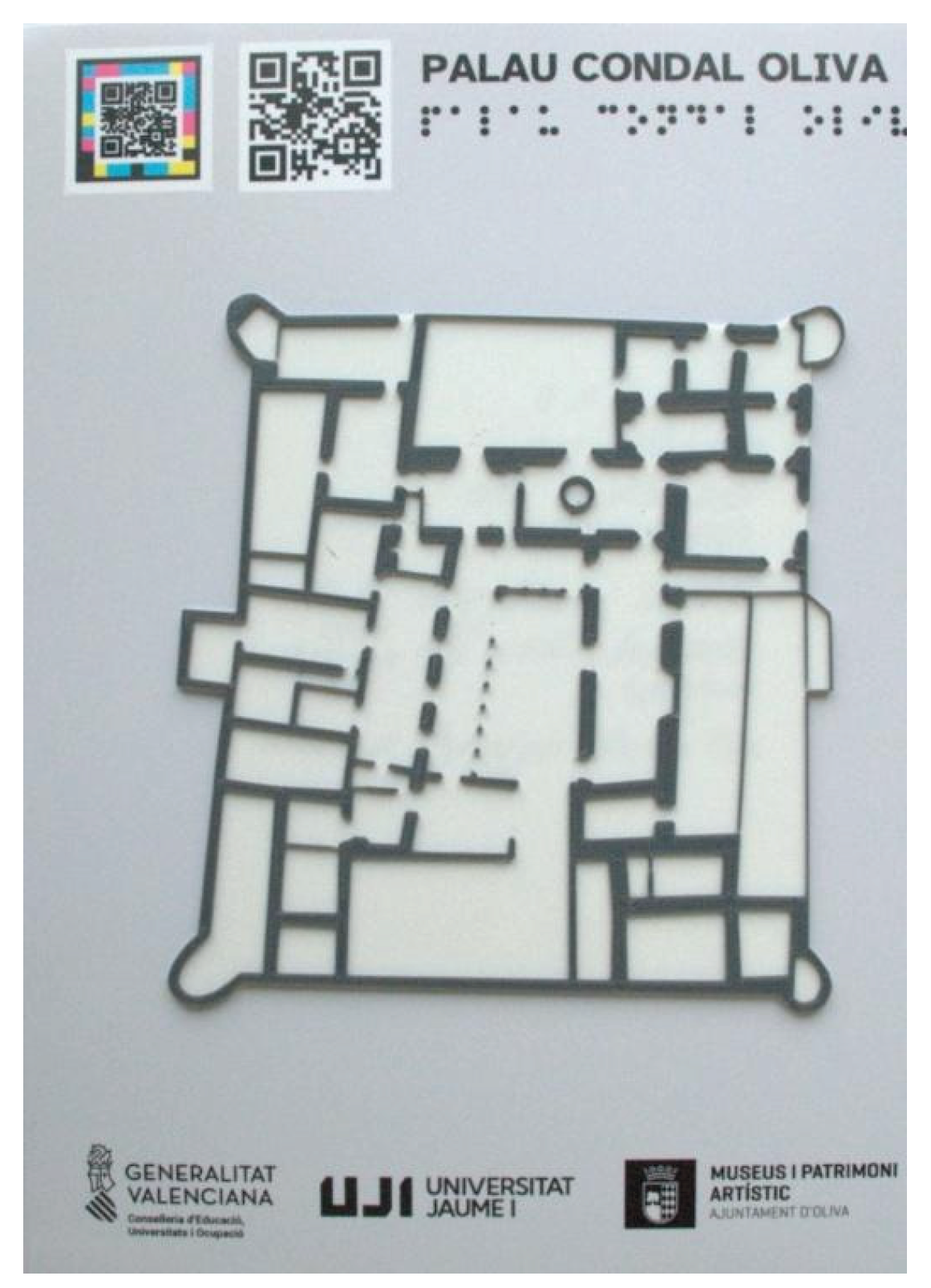

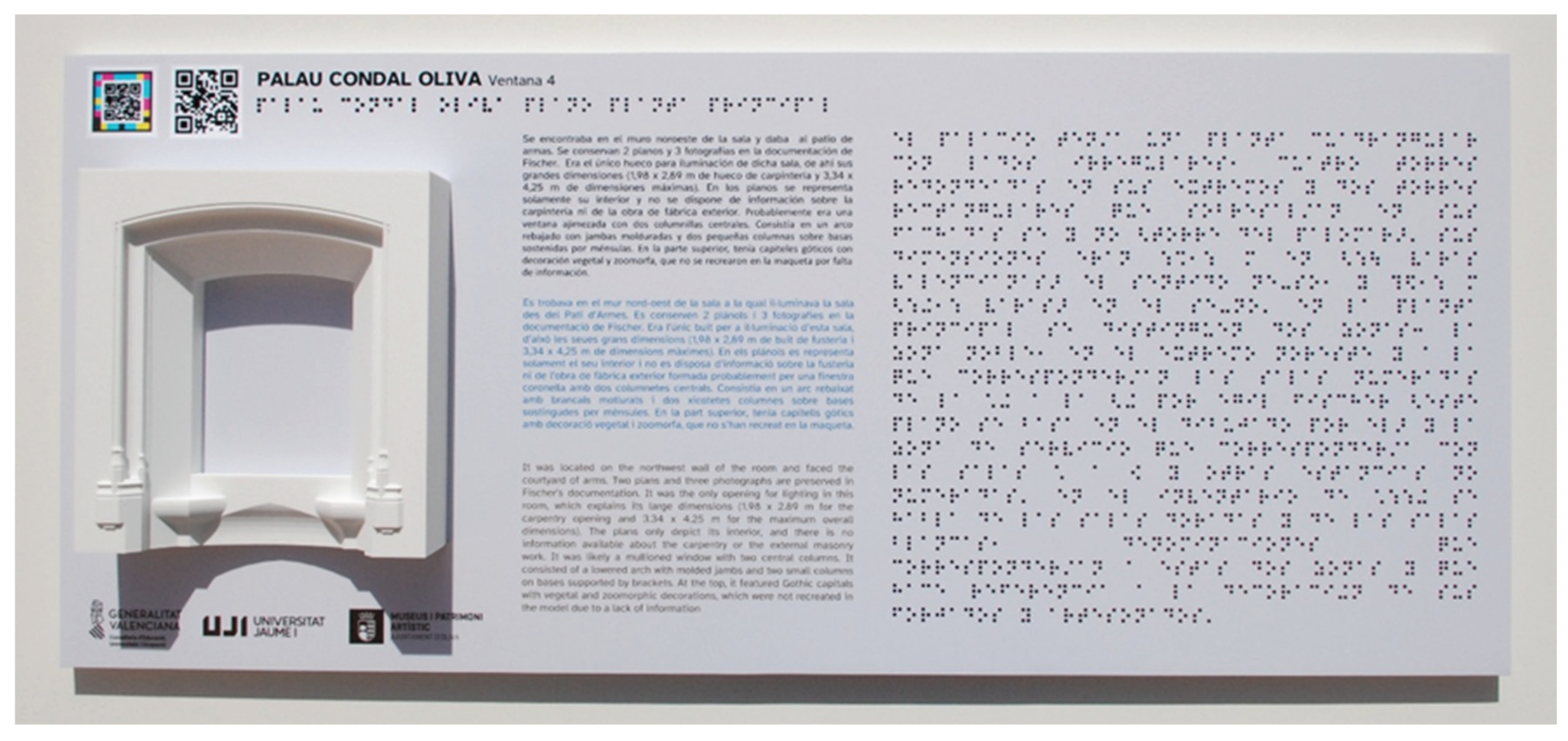

3.2.4. Multimodal Panels

They incorporate, on the one hand, physical models, interesting for all types of audiences and that allow tactile interpretation. It also introduces additional material in the form of texts, with a Braille version. It is complemented by the link to the website, incorporating new information such as audio in different languages.

For the creation of the tactile models of the portals, window, and coffered ceiling, the same 3D digital models used in the rest of the tools have been utilized. The CAD files were exported in STL format, and the meshes were reviewed and repaired using Meshlab software. For the floor plans, 2D CAD files were used as a starting point, their shapes were simplified to facilitate interpretation by visually impaired individuals, and the walls were extruded to obtain 3D models. These models were then exported in STL format, following the same process as the other pieces.

For the realization of the multimodal panels, the design recommendations of various organizations with extensive experience have been followed in order to design the visual text aspects and the Braille Code [

42,

43,

44,

45].

In addition, for the realization of the haptic model, additive manufacturing techniques have been used to produce the model, specifically a Fused Deposition Modelling (FDM) Ultimaker S3 Printer: the models have been made in Polylactic acid (PLA), using the Ultimaker Cura 5.8 slicer program. For the creation of the tactile embossed floor plans, a dual extruder was used, printing in two colors (white base and black walls). This approach facilitates the comprehension of these panels for sighted individuals or those with visual impairments (see

Figure 14).

For the design of the web page the free WIX Platform has been used, trying to follow the pertinent recommendations to expose the information in an accessible way to any User [

46].

4. Results

This section may be divided into subheadings and should provide a concise and precise description of the experimental results, their interpretation, and the conclusions drawn from the experiments.

4.1. Graphic Restitution

For the graphic reconstruction of the Palace of Oliva, the starting point was the graphic material produced by the Danish architects Fischer and Lauritzen, stored at the AMO. This material consists of plans, notebooks, and photograph albums. All this documentation has been digitized, making it easier to handle and having been previously classified.

After analyzing the existing graphic documentation of each architectural element, the plans and photographs were corrected and scaled to determine the dimensions of elements not specified in the plans. This process allowed for the drafting of elevations and sections of the different components.

Subsequently, 3D models of the various elements (portals, window, and coffered ceiling) were created and then assembled to form the 3D model of the hall, which was exported as an OBJ file.

To reconstruct these architectural assets and represent them digitally and virtually, the reconstruction was based on the graphic documentation prepared by Fischer and Lauritzen for the Palace of Oliva, along with archival documentation [

24,

25,

26].

Table 1 shows the characteristics of the files for each of the models that make up the hall, as well as for the complete. Since these files were obtained through digital modeling, their size is moderate and it has not been necessary to perform mesh retopology, so their geometry has not been altered.

4.2. VR vs. AR for Architectural Visualization

There are certain differences between the two techniques used, VR and VA. Although it is true that at the level of the process of creating scenarios and objects with these methods (VR and VA) it can be considered accessible, it cannot be ignored that the creation of 3D scenarios and objects requires a minimum knowledge of 3D modeling and digitization. In this sense, the development of applications in the cloud has improved access to certain cultural content.

4.2.1. Augmented Reality

Access by users is simple when it comes to using the AR technique, since visualization can be done from most devices (desktops, laptops, tablets, smartphones, etc.). Navigation through the platform can be done at different levels: from the 3D Visualizer-Renderer on the device’s screen with which the 3D model is accessed, or also from the device’s camera in AR (see

Figure 15).

4.2.2. Virtual Reality

On the other hand, VR requires a specific device such as “glasses” (see

Figure 8) that replaces the display on a flat screen and the use of gloves or controllers that make it possible to interact with the scene. The latter technique allows a greater degree of immersion than the previous one by “isolating” the user in the digital environment (See

Figure 16).

In any case, these techniques based on free applications on the cloud have significant shortcomings: limitation of the polygonization of 3D models and the reproduction of textures in a realistic way.

Finally, the possibility of including tags that include metadata allows additional information to be added within the model, such as explanatory texts and old photographs and documents that help to understand and contextualize these architectural elements (see

Figure 17) in an immersive experience.

4.3. Multimodal Panels

The Hall’s architectural components are elucidated through a series of 9 multimodal panels, which have been strategically implemented to provide comprehensive contextual interpretation:

These informational panels have been manufactured by direct printing on 3 mm composite

(Dibon), with dimensions of 680x290 mm, according to the recommendation of maximum size for an optimum haptic exploration in terms of usability [

45]; direct printing allows the creation of elements in ink, braille and embossing if required. These information panels are divided, from an informative point of view, into five parts, following the recommendations on information panels oriented to visually impaired people [

45]:

Title of the components with access codes (QR code and Navilens code) to accessible hypertext web (W3C, online) for further information and translation of the title to Braille reading and writing code. These elements are located on the upper left side.

Haptic scale model for haptic scanning in the left area of the panel.

Large and contrasted text in the middle area of the panel, for reading by people with low vision. The text is presented in three different languages, Spanish, Catalan and English.

Corresponding text in Braille code on the right side of the panel.

Institutional logos of the public entities that have financed the Project, in the lower left part of the panel.

The arrangement of these elements in their respective positions is attributable to ergonomic considerations, primarily to facilitate simultaneous haptic exploration and braille code reading, should the user prefer this approach.

The typography employed in the title and body of the panels utilizes rectilinear forms, specifically Helvetica typeface, with a 28-point size for the title and 14-point size for the descriptive paragraphs. The contrast between text and background has been optimized to facilitate reading for individuals with low vision. The content of the texts has been adjusted to an appropriate cognitive level, avoiding excessive technical vocabulary that would impede comprehension, as well as excessive length (150 words) to maintain visitor attention. The embossed text of the Braille code has been contrasted for users with visual impairment, and its size has been adjusted to the relevant standards [

43]. Furthermore, the model has been dimensioned for a haptic display accommodating both hands, in which at least the basic general shapes can be perceived [

42,

44]. Additionally, two codes have been incorporated to facilitate access to a website where the documentation is expanded. These codes (QR and Navilens) provide enhanced flexibility of use by functioning as elements that direct the user to a hypertextual scenario. The web page has been designed adhering, to the extent possible, to minimum accessibility standards [

46] that enable reading for diverse user types, including visually impaired individuals who, with a verbal text reader on their access device, can navigate through it (see

Figure 22).

5. Discussion

While numerous studies have investigated the digital reconstruction of architectural heritage spaces, this work stands out for focusing on a completely lost architectural site: the Golden Hall of the Earl’s Palace in Oliva. This hall has been reconstructed using high-value heritage graphic documentation (sketches, plans, and photographs) produced by Fischer and Lauritzen in the early 20th century. This material has enabled a faithful recreation of the original architectural elements and their dissemination through a range of visual and interpretive resources, making the space accessible and understandable to a broad and diverse audience.

AR and VR techniques based on free applications on clouds have significant shortcomings: limitation of the polygonization of 3D models and the reproduction of textures in a realistic way (see

Figure 23).

The values of historical architecture are manifold, and it is essential to reflect on the possibilities of their transmission. The development of educational materials should consider the advantages and disadvantages of applying different media and technologies.

For the development of this work, prior experience from other projects in which some of the techniques used in this work were applied has been considered [26, 27, and 28]. The originality of this work lies in an integrated strategy for graphic restoration and accessibility, combining different tools:

Detailed 3D modeling using CAD tools.

Augmented Reality (AR) visualization, accessible from mobile devices.

Immersive Virtual Reality (VR) experiences using state-of-the-art headsets.

Haptic and multimodal resources integrated into multimodal panels: tactile models, raised maps, Braille texts, and QR codes/NaviLens.

This simultaneous combination of tools, aimed at all audiences (with and without visual impairments), is innovative and pioneering due to its inclusive approach.

The complexity of architectural heritage values and the diverse contexts in which different cases exist create a broad range of opportunities for material generation and dissemination techniques. This study applies these Considerations in a specific case, developing various systems for analysis. It further reflects on the unique characteristics and potential of each system concerning the information conveyed and the diverse audience it aims to reach.

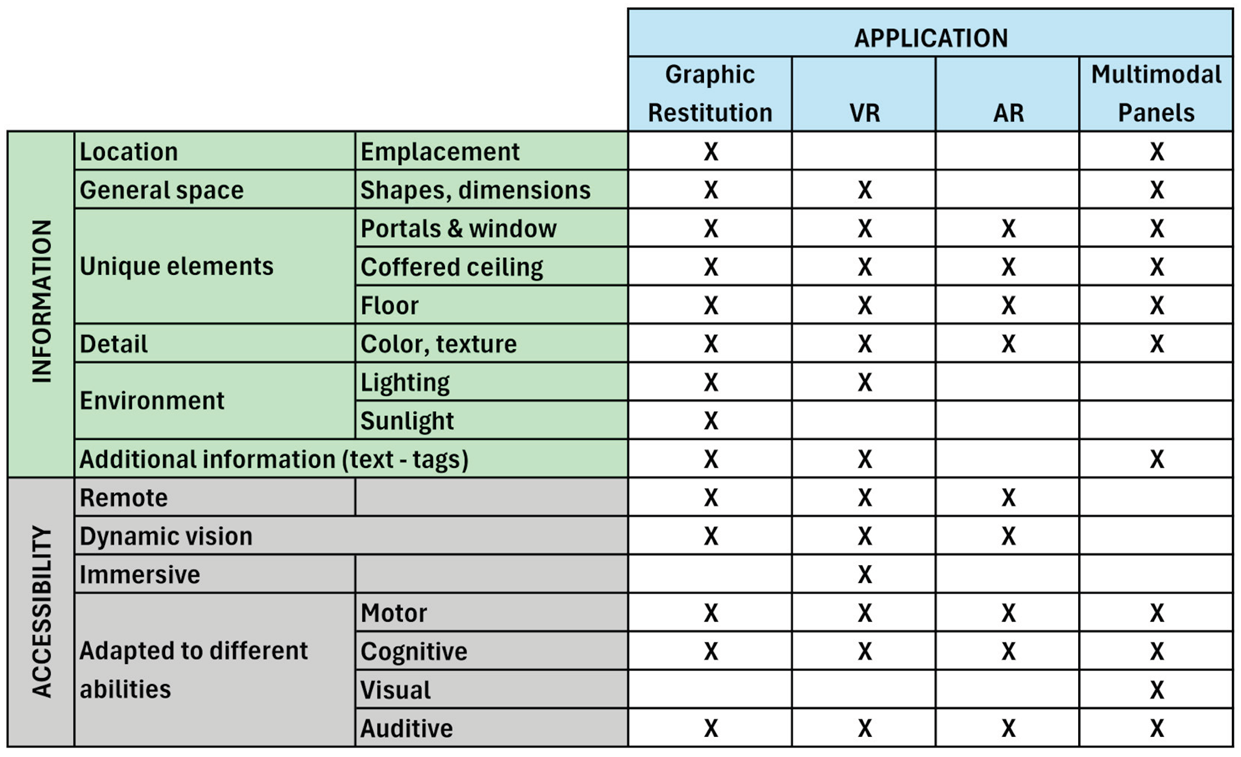

Table 2 analyzes the four techniques used in this study to represent these architectural elements (Graphic Restitution, VR, AR, and Multimodal Panels) and the results obtained in this specific case study, considering both the information provided by each tool and their level of accessibility.

5.1. Information

A comparative analysis has been conducted on the information contained in the different media applied in this studio.

5.1.1. Emplacement

The location of the hall within the palace, as well as the placement of its architectural elements, has been represented in the graphic restitution documentation through site plan and floor plans. Specifically, a floor plan of the main level of the palace was developed to identify the position of the Golden Hall. Additionally, two multimodal panels featuring embossed floor plans were created: one illustrating the first floor of the palace with the Golden Hall clearly marked, and another detailing the interior layout of the Golden Hall itself, showing the locations of its various portals and the window.

5.1.2. General Space

The digital model allows for the interpretation of shapes and dimensions, either through direct measurement within the digital environment, through graphic or numeric scales in printed formats, or through graphic scales in digital formats. In the case of VR, the models are scaled in relation to the user’s avatar, enabling them to be experienced at a real-life scale (1:1), thus offering an immersive experience of the Golden Hall with all its architectural elements. In this case, since it is an interior space, a complete AR visualization model has not been developed. The multimodal panels allow the interpretation of the hall’s overall dimensions through tactile reference scales.

5.1.3. Unique Elements

All the tools make it possible to recreate and interpret the architectural elements individually: portals 12, 13 and 28, window 4, rhomboidal coffered ceiling and the flooring.

5.1.4. Details

Texture and color can be applied in all tools. In the case of multimodal panels, color can be applied through painting techniques or color printing for mockups. Indirectly, color and textures can be found in digital models through the website. In this case, the textures and colors have only been applied in the digital model, while the coffered ceiling mockup has been given a golden finish, emulating the original color of the ceiling.

Figure 24.

Mockup of the coffered ceiling with golden finish.

Figure 24.

Mockup of the coffered ceiling with golden finish.

5.1.5. Environment

Specific lighting and sunlight conditions can only be obtained through specialized software using the digital model, although in VR, different lighting conditions could be applied. In the case of multimodal panels, these parameters can be included through renders or videos created from the digital model. In the VR model, it has been simulated that the room is illuminated by natural light coming through Window V4, just as it might have appeared during the day in the past.

5.1.6. Additional Information (Tags)

Different tools can be used to apply tags to digital models, incorporating additional information such as explanatory texts, images, or old plans that served as a starting point for their creation. Each element in the room includes a tag with its name, a brief description, as well as historical images that serve as a starting point for the present work. These tags can be viewed through virtual reality, allowing for an immersive museum visit by adding additional information to the model. Likewise, this information can be accessed from multimodal panels by linking to the website through QR codes.

5.2. Accessibility

This section will analyze different aspects related to the accessibility of each tool.

5.2.1. Remote

The different tools allow access from anywhere, offering advantages in cases of complex access and eliminating the need for travel. This facilitates global accessibility. This aspect does not apply to multimodal panels, although it does to the website that serves as a supporting tool for them.

5.2.2. Dynamic Vision

The different tools enable users to explore the room and adjust their viewpoint. Nevertheless, the same constraint discussed in the previous section remains applicable.

5.2.3. Immersive experience

The use of a device such as glasses or a headset enables the simulation of real experience in an environment where movement and interaction are possible. Only VR provides fully immersive experience.

5.2.4. Adaptation to Different Abilities

This refers to how each system accommodates users with different abilities: motor, cognitive, visual, or auditive. All tools ensure accessibility for people with motor, cognitive, or auditory impairments, either directly or through an inclusive website. For visually impaired individuals, only multimodal panels provide a haptic interpretation of the models. However, through the website, users can print the models themselves by downloading the models, allowing them to interpret them through touch.

An agreement has been established with the Archaeological Museum of Oliva (AMO) to produce these multimodal panels, which will allow for future empirical testing of these materials. This will make it possible to assess their usability and identify any potential weaknesses to be addressed in future work.

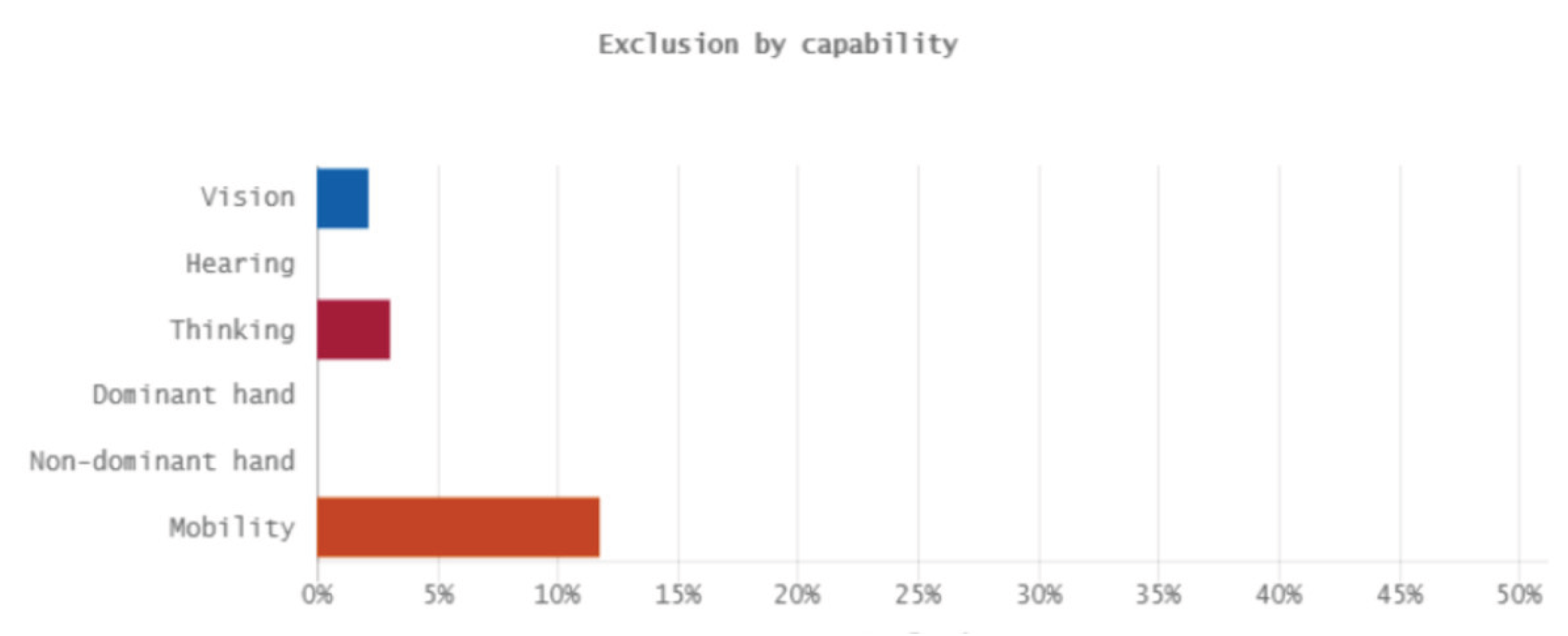

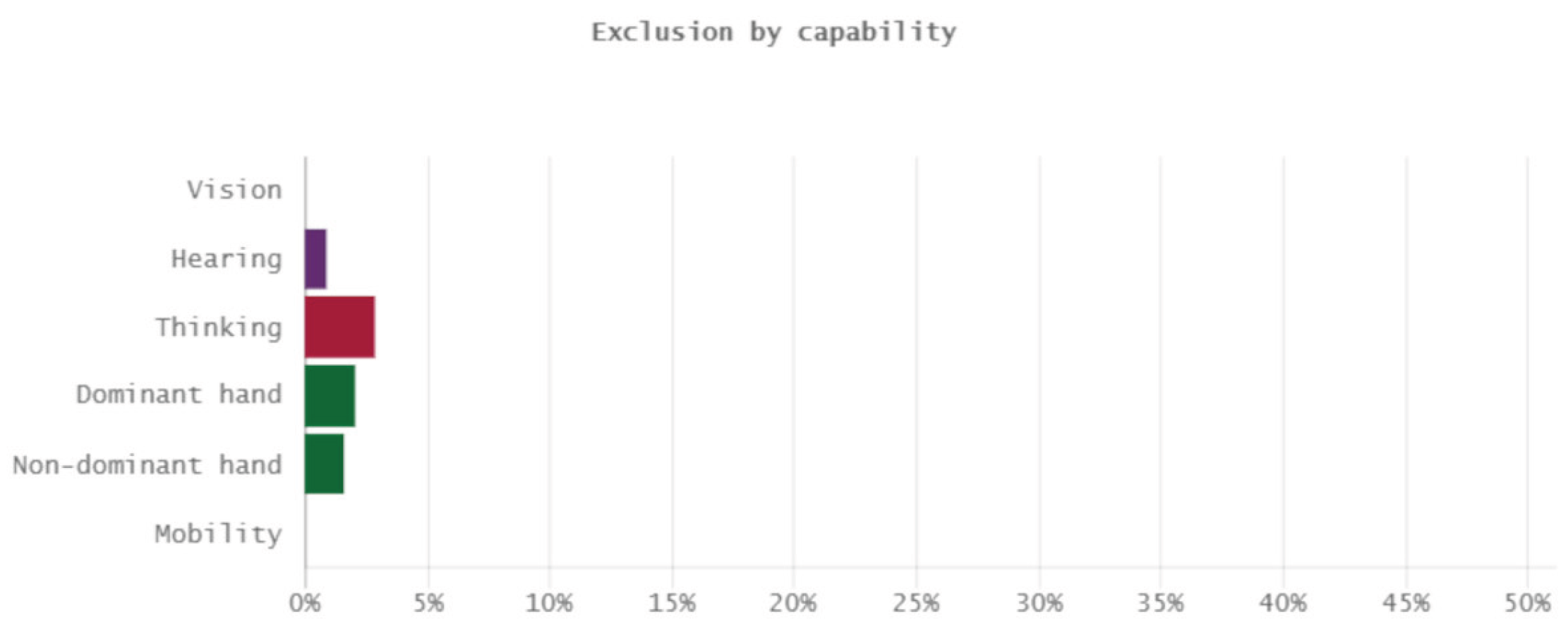

5.3. Exclusion Calculator Analysis

This section presents an analysis of the proportion of the population excluded by the use of conventional panels compared to the multimodal panels developed in this study, with consideration given to the capabilities required for their use. These results have been estimated using the Exclusion Calculator Lite v2.1 [

48], a tool developed by the University of Cambridge. To validate the findings, two analyses were conducted: one involving a visit to a comparable real building (Conventional visit), and the other examining the multimodal panels developed in this research. The capabilities assessed include Vision, Hearing, Thinking, Handiness, and Mobility.

5.3.1. Conventional Museum Visit

In this initial assessment, we examined a museum visit to a comparable room situated on the second floor of a historic building, accessible solely via a staircase lacking handrails, and featuring panels with explanatory texts and figures. This scenario is typical of many small-scale museum centers. The resulting exclusion level was determined to be 13.3% (see

Figure 25).

5.3.2. Multimodal Panels Visit

In the second evaluation, the interpretation of the Golden Hall was assessed utilizing the multimodal panels developed in this study. The resulting exclusion level was determined to be 5.6% (see

Figure 26).

Based on the aforementioned data, there is an enhancement in accessibility, as multimodal devices have become less exclusive and discriminatory, thereby fostering greater inclusivity for individuals with diverse abilities. This development not only signifies an improvement in the level of inclusion but also contributes to a generally enhanced experience for all kinds of visitors.

6. Conclusions

The use of VR and AR in architectural heritage is currently being developed for a more accessible and simple use, as can be seen in this study. Moreover, if these models, created at local level, are presented on internet platforms, their dissemination is extended on an international scale, without restrictions of time or space. These tools facilitate access to historical information and enhance user experience in educational settings and museums.

Therefore, we can conclude that current techniques, both data collection and modelling, specific software, as well as the use of VR or AR technologies, together with the exhaustive scientific study of historic architectural assets, allow us to enjoy all or part of the lost historic buildings in an efficient way, recovering these partially disappeared architectures.

It would seem appropriate to implement more powerful rendering engines capable of reproducing volumes and textures with higher definition on free-to-air VR and AR viewing platforms.

Multimodal panels, such as tactile models with Braille and acoustic information, have been developed to ensure accessibility for visually impaired individuals. The combination of different presentation formats (graphic, haptic, and digital) promotes greater inclusion in architectural heritage dissemination.

Free cloud-based platforms have limitations in realistic texture reproduction and 3D model resolution. Improving rendering engines and exploring more advanced interactive systems could optimize the visualization and understanding of architectural heritage in the not-too-distant future.

Given the numerous possibilities of techniques and devices for providing immersive experience, it is essential to conduct an initial analysis of the target audience and the type of information to be conveyed, relating this to the effectiveness of each system. This approach makes it possible to establish an overall strategy for determining both the content and the technologies required to achieve the optimal result.

This work makes it possible to interpret and visualize this now-disappeared architectural space in an immersive and accessible way, bringing it closer to all types of audiences. Currently, the only way to appreciate these architectural elements is through the photographs and plans created by Ficher and Lautitzem, which makes their interpretation and contextualization challenging. The architectural pieces created have been adjusted to the measurements of the original blueprints, which were carried out with great technical precision by the Danish architects. Those elements for which measurements were not available have been scaled based on the existing blueprints and photographs, and in some cases, they have been based on similar pieces from the period that still exists today.

This study adopts a multidisciplinary and inclusive approach that goes beyond the digital documentation and reconstruction of a lost architectural space by adapting it into accessible formats for a wide and diverse audience. The integration of historical accuracy, technical precision, and a strong commitment to social inclusion makes this work a novel and meaningful contribution to the field of digital cultural heritage.

The upcoming implementation of the materials developed in this project at the Oliva Archaeological Museum through a collaboration agreement will make them accessible to a wide range of audiences, thereby enhancing the museum’s overall accessibility. Testing the usability and inclusivity of these tools will allow for identifying their weaknesses and detecting areas for improvement in future applications.

In conclusion, each of the tools used in this study should be evaluated based on the type of architecture and its real possibilities. They can be adapted to each specific case, with the potential to combine different tools within the same study, improving the inclusivity index of the visit. These technologies can improve the immersive experience and accessibility of these resources in the future.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.M.M. and J.G.O.; methodology, J.M.M. and J.G.O.; software, J.M.M. and J.G.O.; validation, J.M.M., J.G.O. and A.S.E.; formal analysis, J.M.M., J.G.O. and A.S.E.; investigation, J.M.M., J.G.O. and A.S.E.; resources, J.M.M. and J.G.O. ; data curation, J.M.M. and J.G.O.; writing—original draft preparation, J.M.M., J.G.O. and A.S.E. ; writing—review and editing, J.M.M., J.G.O. and A.S.E.; visualization, J.M.M. and J.G.O.; supervision, J.M.M., J.G.O. and A.S.E.; project administration, J.M.M.; funding acquisition, J.M.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Please add: This research has been funded by Generalitat Valenciana, Conselleria de Educación, Universidades y Empleo, grant number CIGE/2023/123, project: “Graphic survey, study, cataloging and dissemination of curtain portals in the Valencian Community”.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available upon request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We thank Andreea Caraiman for her work in the preparation of the multimodal panels and the website.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| CHS |

Cultural Heritage Site |

| AMO |

Archaeological Museum of Oliva |

| AR |

Augmented Reality |

| VR |

Virtual Reality |

| HCI |

Human Computer Interaction |

References

- Boas, Y.A. Overview of Virtual Reality Technologies. Interact. Multimed. Conf. 2013. Available online: https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/Overview‐of‐Virtual‐Reality‐Technologies‐Boas/4214cb09e29795f5363e5e3b545750dce027b668 (accessed February 2025).

- Burdeaux, G.C.; Coiffet, P. Virtual Reality Technology; John Wiley & Sons, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Beji, F.; Ferreira, W.; Pivotto Dabat, I.; Matias, V. CAVE Automatic Virtual Environment Technology: A Patent Analysis. Eng. Proc. 2025, 89, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cordeil, M.; Dwyer, T.; Klein, K.; Laha, B.; Marriott, K.; Thomas, B.H. Immersive Collaborative Analysis of Network Connectivity: CAVE-Style or Head-Mounted Display? IEEE Trans. Vis. Comput. Graph. 2017, 23, 441–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Forte, M.; Pescarin, S.; Pujol Tost, L. VR Applications, New Devices and Museums: Public’s Feedback and Learning. A Preliminary Report. Proc. 7th Int. Symp. Virtual Reality, Archaeol. Cult. Herit. 2006, 64–69. Available online: https://acortar.link/hi30YA (accessed on 1 February 2025).

- Bakar, J.A.A.; Jahnkassim, P.S.; Mahmud, M. User Requirements for Virtual Reality in Architectural Heritage Learning. International Journal of Interactive Digital Media 2013, 1, 37–45. [Google Scholar]

- Farella, E.; Menna, F.; Remondino, F.; Campi, M. 3D Modeling and Virtual Applications for the Valorization of Historical Heritage. Proc. 8th Int. Congr. Archaeol. Comput. Graph. Cult. Herit. Innov. 2016, 456–459. Available online: https://riunet.upv.es/bitstream/handle/10251/85988/4157-11565-1-PB.pdf?sequence=1 (accessed on 1 February 2025).

- Kantner, J. Realism vs. Reality: Creating Virtual Reconstructions of Prehistoric Architecture. BAR Int. Ser. 2000, 843, 47–52. [Google Scholar]

- Brusaporci, S.; Maiezza, P. Smart Architectural and Urban Heritage: An Applied Reflection. Heritage 2021, 4, 2044–2053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Val Fiel, M.; Soler-Estrela, A. Interactive Virtual Reality Applications for the Enhanced Knowledge of Spanish Mediterranean Fortress-Castles. Disegnarecon 2021, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Younes, G.; Kahil, R.; Jallad, M.; Asmar, D.; Elhajj, I.; Turkiyyah, G.; Al-Harithy, H. Virtual and Augmented Reality for Rich Interaction with Cultural Heritage Sites: A Case Study from the Roman Theater at Byblos. Digit. Appl. Archaeol. Cult. Herit. 2017, 5, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto, I.; Huertas, A. A Comparative Study of VR and AR Heritage Applications on Visitor Emotional Experiences: A Case Study from a Peripheral Spanish Destination. Virtual Reality 2025, 29, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aso, B.; Navarro-Neri, I.; García-Ceballos, S.; Rivero, P. Quality Requirements for Implementing Augmented Reality in Heritage Spaces: Teachers’ Perspective. Educ. Sci. 2021, 11, 405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dogan, E.; Kan, M.H. Bringing Heritage Sites to Life for Visitors: Towards a Conceptual Framework for Immersive Experience. Adv. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2020, 1, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, D.I.; Dieck, M.C.; Jung, T. User Experience Model for Augmented Reality Applications in Urban Heritage Tourism. J. Herit. Tour. 2018, 13, 46–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rueda Márquez de la Plata, A.; Cruz Franco, P.A.; Ramos Sánchez, J.A. Applications of Virtual and Augmented Reality Technology to Teaching and Research in Construction and Its Graphic Expression. Sustainability 2023, 15, 9628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luna, U.; Rivero, P.; Vicent, N. Augmented Reality in Heritage Apps: Current Trends in Europe. Appl. Sci. 2019, 9, 2756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ICOM. Museum Definition; International Council of Museums, 2022. Available at https://icom.museum/es/recursos/normas-y-directrices/definicion-del-museo/ (accessed February, 2025).

- Consuegra Cano, B. Antecedentes históricos de las colecciones del Museo Tiflológico. Integración: Revista sobre Ceguera y Deficiencia Visual.

- Clarkson, P.J.; Coleman, R.; Keates, S.; Lebbon, C. Inclusive Design: Design for the Whole Population; Springer-Verlag: Berlin, Germany, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Gual, J.; Puyuelo, M.; Lloveras, J. Universal Design and Visual Impairment: Tactile Products for Heritage Access. Proceedings of the 18th International Conference on Engineering Design (ICED11); Culley, S.J., Ed.; The Design Society: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2011; pp. 155–164. [Google Scholar]

- Puyuelo Cazorla, M.; Val Fiel, M.; Merino Sanjuan, L.; Gual Ortí, J. Diseño Inclusivo y Accesibilidad a la Cultura; Colección UPV [Scientia], 2018.

- Martínez Moya, J. Ángel; Soler Estrela, A. Metodología de Recuperación Gráfica de las Portadas del Palacio Condal de Oliva. EGE Revista de Expresión Gráfica en la Edificación 2014, 8, 35–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez Moya, J. Ángel. Restitución Gráfica de la Sala 12 del Palacio Condal de Oliva a Partir del Legado Gráfico de Fischer y Lauritzem. EGA Expresión Gráfica Arquitectónica 2016, 21, 60–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Moya, J.A. The Centelles’ Palace of Oliva: The Recovery of Architectural Heritage through Its Plundering. Buildings, 2018, 8, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Moya, J.A.; Gual-Ortí, J.; Máñez-Pitarch, M.J. Physical Scale Models as Diffusion Tools of Disappeared Heritage. Lecture Notes in Civil Engineering 2018. [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Moya, J.A.; Gual-Ortí, J. Graphic Restitution and Recovery of the Chronos Pavement of the Marquis of Benicarlo’s House. Heritage 2024, 8, 4206–4226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soler Estrela, A.; Martínez Moya, J.Á.; Li, S. Musealisation of architectural heritage for sustainable and inclusive tourism. The Yonghe Temple. Beijing. VITRUVIO—International Journal of Architectural Technology and Sustainability 2024, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muller, P. El Palacio de Oliva de los Centelles. Arkitekturhistorisk Årsskrift 1996, 18, 127–157. [Google Scholar]

- Gavara Prior, J.J.; Muller, P.E. El Palacio Condal de Oliva. Catálogo de los Planos de Egil Fischer y Vilhelm Lauritzen; Ajuntament de Oliva: Oliva, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Mestre i Pons, F. L’Associació Cultural Centelles i Riu-sech. In El Palau dels Centelles d’Oliva. Recull Gràfic y Documental; Esteve i Blai, A., Ed.; L’Associació Cultural Centelles i Riu-sech Oliva; Gràfiques Colomar: Oliva, Spain, 1997; pp. 41–76. [Google Scholar]

- Bérchez Gómez, J. Catálogo de Monumentos y Conjuntos de la Comunidad Valenciana I; Consellería de Cultura, Educación y Ciencia: Valencia, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Felip Sempere, V. Recull per a una Història de Nules; Caixa Rural Sant Josep de Nules: Nules, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Fischer, E.; Lauritzen, V. Blueprints, Notebook I, Notebook II, Large Photo Album, Small Photo Album; Archaeological Museum of Oliva. Earl’s Palace documentation, 1919–1920.

- Zaragozá Catalán, A. Arquitectura Gótica Valenciana. Siglos XIII-XV; Consellería de Cultura i Educació: Valencia, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Sketchfab. Available online: https://sketchfab.com/ (accessed on 1 February 2025).

- Syahputra, M.F.; Hardywantara, F.; Andayani, U. Augmented Reality Virtual House Model Using ARCore Technology Based on Android. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2020, 1566, 012018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson, I.; Rosen, D.; Stucker, B. Additive Manufacturing Technologies: 3D Printing, Rapid Prototyping, and Direct Digital Manufacturing; Springer: New York, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Bekele, M.K.; Pierdicca, R.; Frontoni, E.; Malinverni, E.S.; Gain, J. A Survey of Augmented, Virtual, and Mixed Reality for Cultural Heritage. J. Comput. Cult. Herit. 2018, 11, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Addison, A.C. Emerging Trends in Virtual Heritage. IEEE Multimedia 2000, 7, 22–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albourae, A.T.; Armenakis, C.; Kyan, M. Architectural heritage visualization using interactive technologies. The International Archives of the Photogrammetry, Remote Sensing and Spatial Information Sciences 2017, 42, 7–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AENOR. UNE-EN ISO 13407. Procesos de Diseño para Sistemas Interactivos Centrados en el Operador Humano; AENOR: Madrid, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- AENOR. UNE 17002. Requisitos de Accesibilidad para la Rotulación; AENOR: Madrid, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Comisión Braille Española. Guías de la Comisión Braille Española. Signografía Básica; ONCE: Madrid, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Comisión Braille Española. Requisitos Técnicos para la Confección de Planos Accesibles a Personas con Discapacidad Visual; ONCE: Madrid, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- W3C. Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG) 2.2. Available at https://www.w3.org/TR/WCAG22/ (accessed February 2025).

- Martínez-Moya, J.A.; Gual-Ortí, J.; Máñez-Pitarch, M.J. Physical Scale Models as Diffusion Tools of Disappeared Heritage. Lecture Notes in Civil Engineering 2018. [CrossRef]

- Inclusive Design Toolkit. University of Cambridge. calc.inclusivedesigntoolkit.com. Available at https://calc.inclusivedesigntoolkit.com (accessed May 23, 2025).

Figure 1.

Main Floor of the Palace. Location of the Golden Room. Source: author.

Figure 1.

Main Floor of the Palace. Location of the Golden Room. Source: author.

Figure 2.

Floor plan of Golden Room. Source: author.

Figure 2.

Floor plan of Golden Room. Source: author.

Figure 3.

Portal 12 documentation: left: blueprint Nr. LA1139, right: picture Nr 77. Source: E. Fischer and V. Lauritzem, 1919-20. A.M.O.

Figure 3.

Portal 12 documentation: left: blueprint Nr. LA1139, right: picture Nr 77. Source: E. Fischer and V. Lauritzem, 1919-20. A.M.O.

Figure 4.

Portal 13 documentation: left: blueprint Nr. LA1146, right: picture Nr 63. Source: E. Fischer and V. Lauritzem, 1919-20. A.M.O.

Figure 4.

Portal 13 documentation: left: blueprint Nr. LA1146, right: picture Nr 63. Source: E. Fischer and V. Lauritzem, 1919-20. A.M.O.

Figure 5.

Portal 28 documentation: left: blueprint Nr. LA1144, right: picture Nr 64. Source: E. Fischer and V. Lauritzem, 1919-20. A.M.O.

Figure 5.

Portal 28 documentation: left: blueprint Nr. LA1144, right: picture Nr 64. Source: E. Fischer and V. Lauritzem, 1919-20. A.M.O.

Figure 6.

Window 4 documentation: blueprint Nr. LA1197. Source: E. Fischer and V. Lauritzem, 1919-20. A.M.O.

Figure 6.

Window 4 documentation: blueprint Nr. LA1197. Source: E. Fischer and V. Lauritzem, 1919-20. A.M.O.

Figure 7.

Coffering ceiling documentation of hall 12: blueprint Nr. LA1116. Source: E. Fischer and V. Lauritzem, 1919-20. A.M.O.

Figure 7.

Coffering ceiling documentation of hall 12: blueprint Nr. LA1116. Source: E. Fischer and V. Lauritzem, 1919-20. A.M.O.

Figure 8.

Left: Original flooring found at the Palace’s Tower of the Comare (MAO). Right: Hypothesis for flooring design based on the tiles from the Tower of the Comare and the design of flooring of the Golden Halls of the Generalitat Palace.

Figure 8.

Left: Original flooring found at the Palace’s Tower of the Comare (MAO). Right: Hypothesis for flooring design based on the tiles from the Tower of the Comare and the design of flooring of the Golden Halls of the Generalitat Palace.

Figure 9.

Golden Hall. 3D CAD file.

Figure 9.

Golden Hall. 3D CAD file.

Figure 10.

3D CAD model of window W-4 of the Palace.

Figure 10.

3D CAD model of window W-4 of the Palace.

Figure 11.

Rendered 3D CAD model of the Palacio de Oliva.

Figure 11.

Rendered 3D CAD model of the Palacio de Oliva.

Figure 12.

Visualization of an architectonical model with Meta Quest 3 headset.

Figure 12.

Visualization of an architectonical model with Meta Quest 3 headset.

Figure 13.

Caption of the Hal with a VR Cardboard viewer.

Figure 13.

Caption of the Hal with a VR Cardboard viewer.

Figure 14.

Tactile map of the main floor printed in two colors.

Figure 14.

Tactile map of the main floor printed in two colors.

Figure 15.

3D model of window W-4 of the Palace of Oliva visualized using AR.

Figure 15.

3D model of window W-4 of the Palace of Oliva visualized using AR.

Figure 16.

View of the Golden Room of the Palace of Oliva (VR).

Figure 16.

View of the Golden Room of the Palace of Oliva (VR).

Figure 17.

View of cover 12 of the Golden Room of the Palacio de Oliva with metadata tag (VR).

Figure 17.

View of cover 12 of the Golden Room of the Palacio de Oliva with metadata tag (VR).

Figure 18.

Multimodal Panel of curtain doorway Nr. 12 of the Golden Hall.

Figure 18.

Multimodal Panel of curtain doorway Nr. 12 of the Golden Hall.

Figure 19.

Multimodal Panel of curtain doorway Nr. 13 of the Golden Hall.

Figure 19.

Multimodal Panel of curtain doorway Nr. 13 of the Golden Hall.

Figure 20.

Multimodal Panel of the left base of curtain doorway Nr. 13 of the Golden Hall.

Figure 20.

Multimodal Panel of the left base of curtain doorway Nr. 13 of the Golden Hall.

Figure 21.

Multimodal Panel of the Window W-4 of the Golden Hall.

Figure 21.

Multimodal Panel of the Window W-4 of the Golden Hall.

Figure 22.

Accessible QR code of web page.

Figure 22.

Accessible QR code of web page.

Figure 23.

QR code of Golden Hall at Sketchfab platform.

Figure 23.

QR code of Golden Hall at Sketchfab platform.

Figure 25.

Exclusion chart for a conventional visit to a similar building.

Figure 25.

Exclusion chart for a conventional visit to a similar building.

Figure 25.

Exclusion chart for the visit using multimodal panels.

Figure 25.

Exclusion chart for the visit using multimodal panels.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the files for each of the models that make up the hall and of the Golden Hall.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the files for each of the models that make up the hall and of the Golden Hall.

Table 2.

Comparison between different tools.

Table 2.

Comparison between different tools.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).