Submitted:

19 March 2025

Posted:

20 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

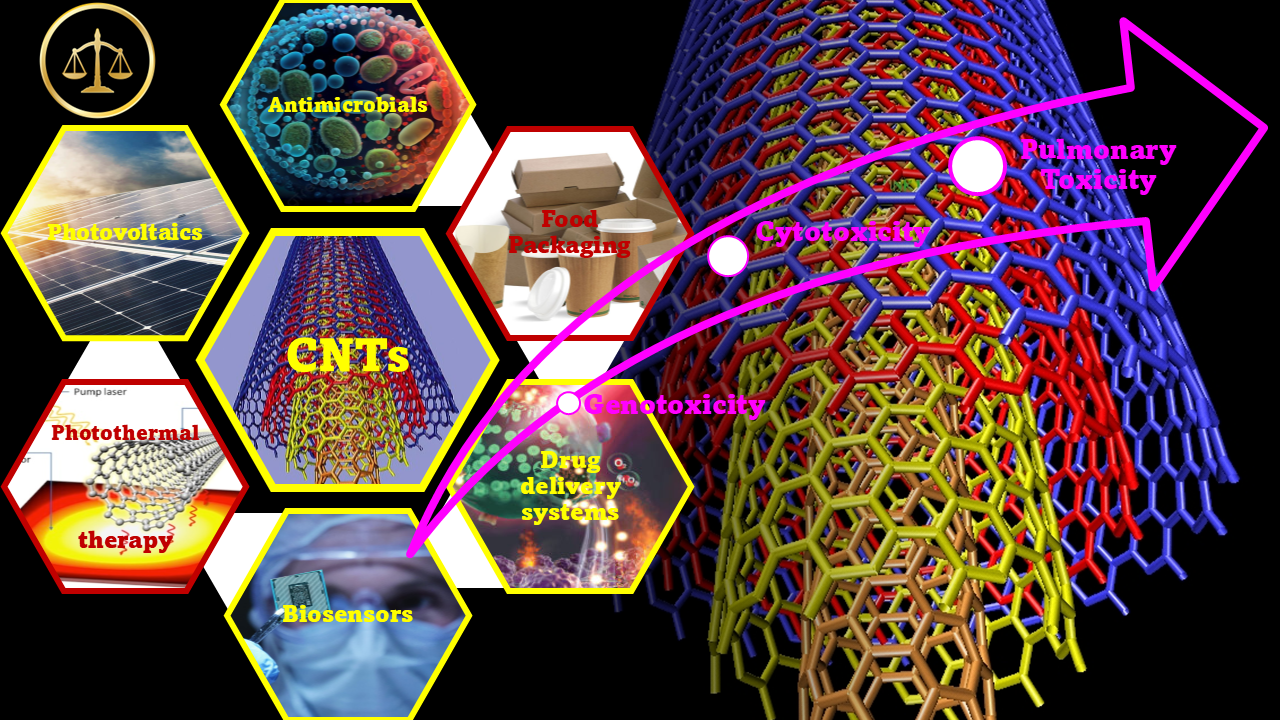

1. Introduction

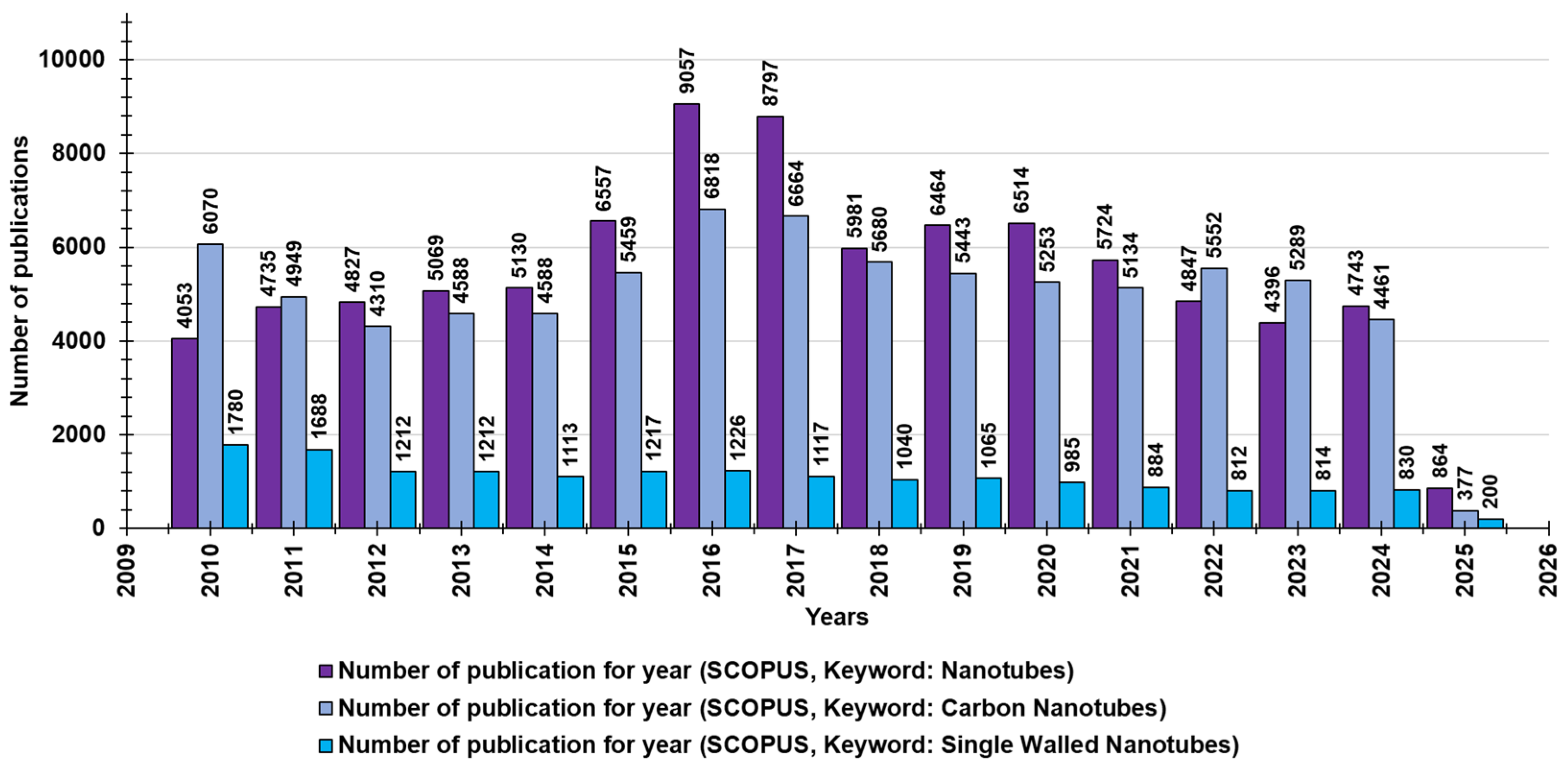

2. Approaching Carbon Nanotubes

2.1. Synthesis of CNTs

2.1.1. Arc Discharge (AD)

2.1.2. Laser Ablation (LA)

2.1.3. Chemical Vapor Deposition (CVD)

2.1.4. High-Pressure Carbon Monoxide (HiPco) Process

2.1.5. Super-Growth CVD (SGCVD)

2.1.6. Plasma Torch (PT)

2.1.7. Liquid Electrolysis Method (LEM)

2.1.8. Natural, Incidental, and Controlled Flame Environments

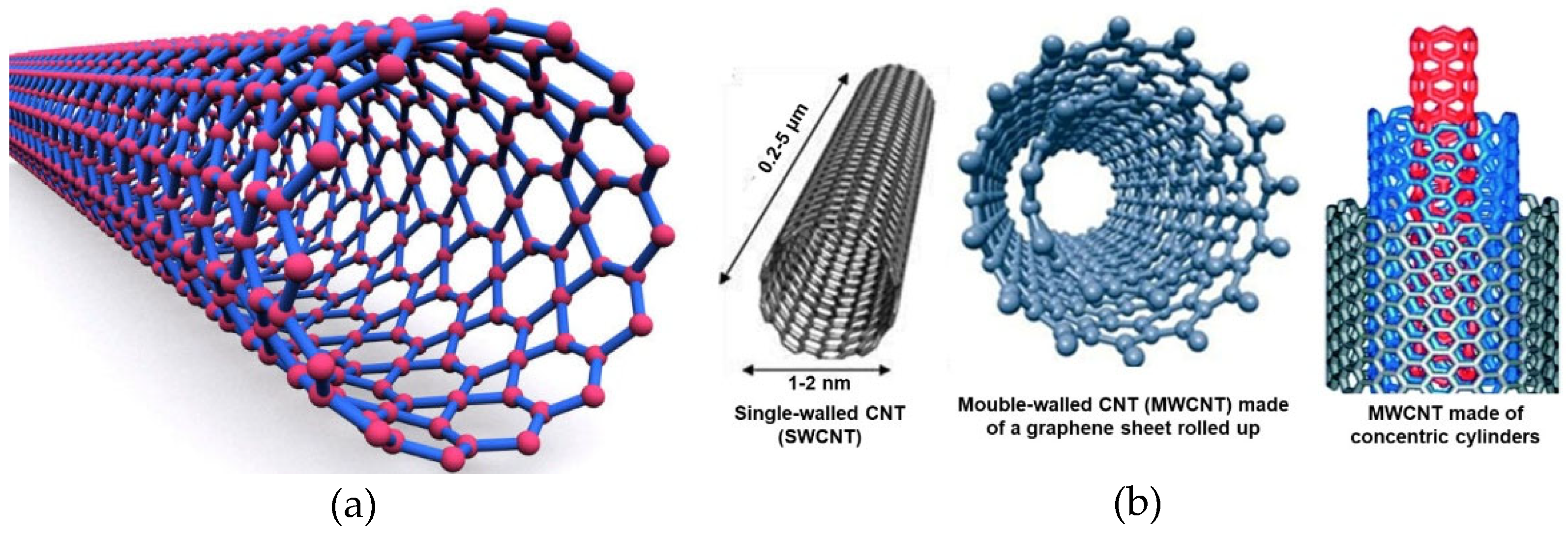

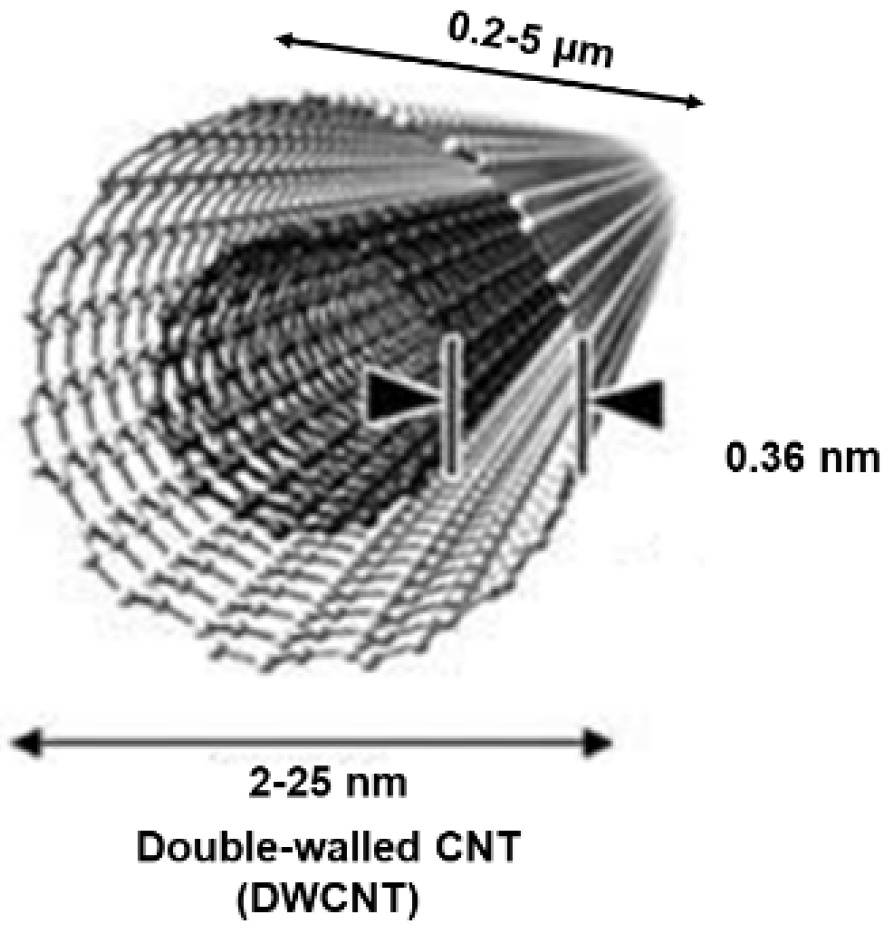

2.2. Architecture and Other Features of CNTs

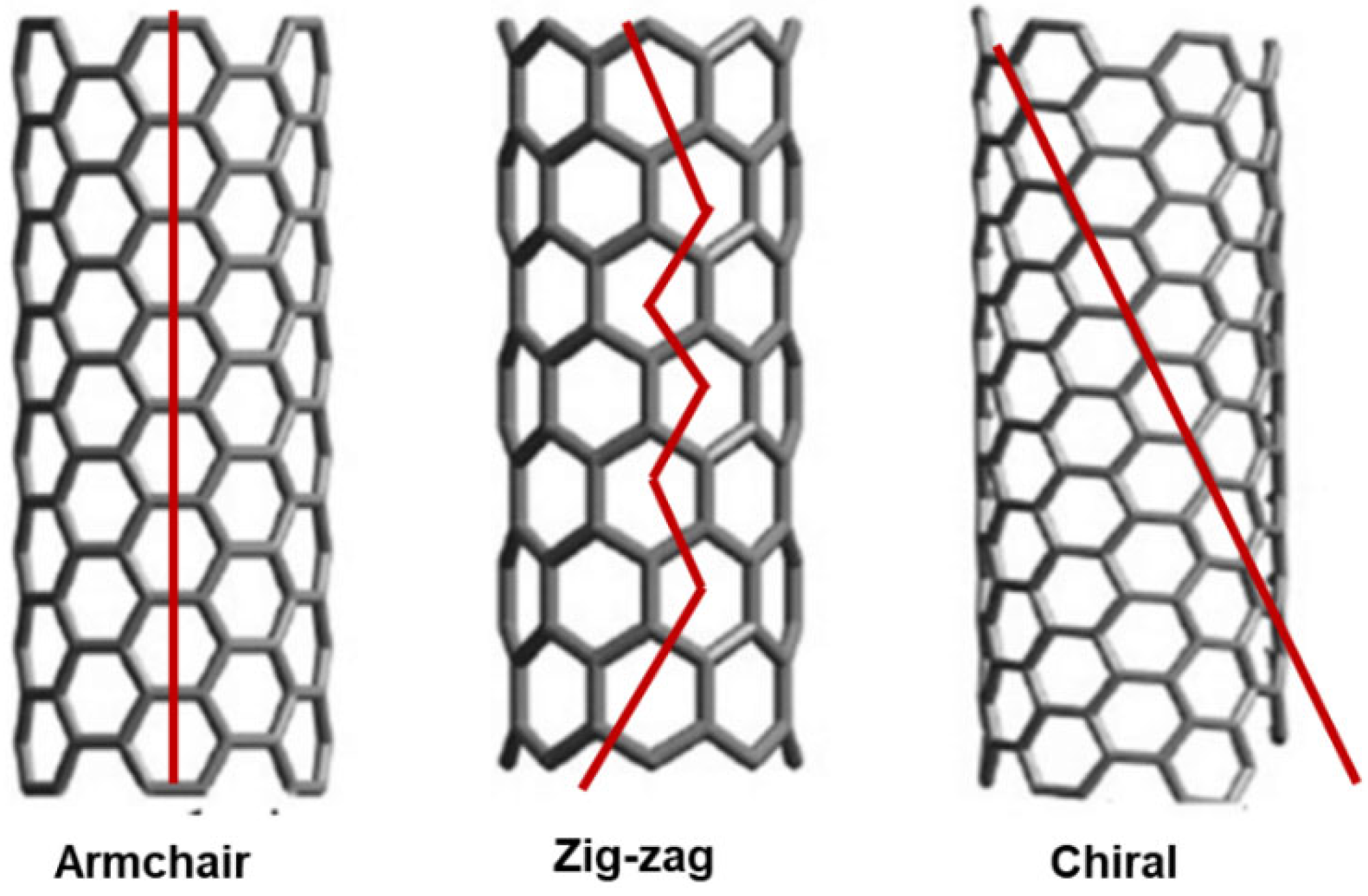

2.2.1. Relationships Structure/Properties

3. Biomedical Applications of CNTs

3.1. Antimicrobial Properties of Carbon Nanotubes

3.1.1. Functionalized SWCNTs

3.1.2. Functionalized MWCNTs

4. Impediments to the Extensive Application of CNTs: Toxicity Issues

4.1. Introduction to Environmental and Human Safety

4.1.1. Other Hurdles Are Close to Solution

4.2. In Vitro and In Vivo Studies

4.2.1. In Vitro Studies

4.2.2. In Vivo Studies: Pulmonary Toxicity

CNTs Cytotoxic Effects to Other Tissues

5. Possible Strategies to Moderate CNTs’ Toxic Effects

5.1. Future Perspective and Preventive Actions

6. Regulatory Considerations

6.1. Authors Considerations and Future Perspectives

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Key Properties | Potential uses | Current hurdles |

|---|---|---|

| Size [61] | Nano-electronics [64] | Electronic heterogeneity [76] |

| Crystallographic defects | ||

| Stone–Wales defects | ||

| Ø < 100 nm Thickness = 1-2 nm Ideally infinite length |

Conductors (SWCNTs) Superconductors Semi-conductors 1 Supercapacitors |

Not tunable conductivity |

| Electrical and electrochemical properties | Interconnects | ⇩ Controllable orientation |

| ⇧ Electrical conductivity Constant resistively [63] Electrons emission capacity |

Chips manufacture [65] Conductivity-enhancing components |

⇩ Organized configuration |

| Thermal Properties | ⇧ Variation in size and density [76] | |

| ⇧ Heat conductivity Expansion |

Optics and photonics | |

| Mechanical properties | Light-emitting diodes (LEDs) [66,67] 2 | Export restrictions |

| ⇧ Tensile strength ⇧Elastic modulus |

Photodetectors [68] 2 | |

| Optical Properties | Bolometers [69] 2 | |

| Absorption properties | Optoelectronic memory devices [70] 2 | |

| Photoluminescence (fluorescence) | ||

| Raman spectroscopy properties | ||

| Others | Batteries [71] | Environmental concerns [76] |

| Easily modifiable structure | ||

| Presence of functional groups | Supercapacitors production Ultra-thin flexible batteries Implantable medical devices |

|

| Chemical inertness | ||

| Easily optimizable solubility and dispersion | Cleaning up polluted environments | |

| Water filtration Air filters, such as smokestacks [72] | ||

| Others | ||

| Transistors production [73,74] | ||

| Energy production | ||

| Solar cells [75] | ||

| Light weight | Energy Storage | |

| ⇧ Biocompatibility | CNT based fibres and fabrics | |

| Capability of molecules immobilization | CNT based ceramics | |

| Transport of protein, DNA, RNA | ||

| Large surface area | Sources of light | |

| High capability of absorbing chemicals from their surroundings | Entrenched dominance of other material |

| Method | Process Type | Products Purity | Conditions Yields (%) | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arc discharge (AC) |

The carbon in the negative electrode sublimates due to the high discharge temperatures (T) |

SWCNTs short tubes Ø=0.6-1.4 nm MWCNTs short tubes Inner Ø=1-3 nm Outer Ø= 10 nm Medium purity |

Argon/N2 500 torr T ≤ 4,000 °C 20-100% |

Few structural defects | Length ≤ 50 µm |

| Laser ablation (LA) |

Graphite samples are vaporized in a reactor at ⇧ T by a pulsed laser in presence of an inert gas CNTs grow up on the cooler reactor’s surfaces as the vaporized carbon condenses |

SWCNTs 5-20 µm Ø=1-2 nm MWCNTs Low purity |

500-1000°C at ⇧ energy laser beam 25-1000°C ≤ 70% |

Controllable Ø by the reaction temperature |

⇧ Expensive than AC, CVD |

| Chemical Vapor Deposition (CVD) |

Layered metal catalyst particles are heated in a reactor where a process gas and a carbon-containing gas are bled into |

SWCNTs long tubes Ø=0.6-4 nm MWCNTs long tubes Ø=10-240 nm Medium-High purity |

Low pressure inner gas (argon) 500-1200°C 60-90% |

⇧ Economic and simple than AD and LA Synthesis at ⇩ temperature and AP ⇧ Yield and purity than AD and LA Versatile in the control of CNTs structure/architecture Suitable for scale up |

⇩ Crystallinity than that by AD and LA Removal of the catalyst support |

| Physical property | Largest | Smallest | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Diameter | N.R. | 0.30 nm (MWCNT) 1 0.43 nm (SWCNT) |

[148] |

| Length | 0.5 m 2 | Cycloparaphenylenes (2.49 Å) 3 | [149] [150] |

| Density | 1.6 g/cm* | N.R. | [151,152] |

| Associations Morphologies |

Type of interaction Arrangement |

Possible products | Applications/Properties | Refs |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CNTs/CNTs* | Junctions s | Metallic CNTs/semiconducting CNTs | Component of NTs-based electronic circuits |

[153,154,157] |

| CNTs/GF* | Junctions | Pillared GF (3D-CNTs) | Energy storage Supercapacitors Field emission Transistors High-performance catalysis Photovoltaics Biomedical devices Implants Sensors |

[158,159,160,161] |

| 2 CNTs/fullerenes* | Covalent Bond | Fullerene-like nanobuds | Field emitters | [162] |

| CNT/fullerenes* | Entrapment | Carbon peapods (CPPs) | Heating devices Irradiating devices Oscillators |

[163,164,165,166] |

| Doughnut shape** | CNTs twisted into a toroid (Annulus shape). |

Nano tori (NTRs) | ⇧ magnetic moment ⇧ stability |

[167,168] |

| GF/MWCNTs* | GFs integrated MWCNTs | GFCNTs | ⇧ Surface area 3D-framework ⇧Total charge capacity per unit of nominal area |

[169,170] |

| 1D carbon structures** | Stacking microstructure of GF layers |

Cup-stacked CNTs (CSCNTs) | Semiconductors | [171] |

| Applications | Principle | Detection Target | Year Ref. |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sensors | Electrochemical sensors | Made of AuNPs + MWCNTs Mannan-Os Adducts | Dopamine | 2015 [9] |

| Made of glassy carbon electrodes modified with MWCNTs and CuMPs dispersed in PEIs | Amino acids and glucose | 2016 [10] | ||

| Based on MWCNTs | Clostridium tetani | 2016 [11] | ||

| Based on AgNPs/ Bi NPs/MWCNTs nafion modified | Lead and Cadmium | 2020 [12] | ||

| Based on carbon sensor fabricated with coalesced Ru–TiO2 NPs and MWCNTs | Cetrizine | 2019 [13] | ||

| Based on glassy carbon sensor modified with MWCNT in pH 9.0 PBS |

Methdilazine | 2019 [14] | ||

| Based on (Ru–TiO2) NPs and MWCNTs | Flufenamic acid (FFA) Mefenamic acid (MFA) |

2019 [15] | ||

| Based on Bi-MWCNT/MCPE at physiological pH | Gallic Acid (GA) | 2020 [16] | ||

| Function | ||||

| Piezoelectric sensors |

Based on MWCNTs on PDMS as substrate | N.R. | 2017 [17] | |

| Based on graphene, CNTs and graphene-CNTs composite | N.R. | 2018 [18] | ||

| Based on MWCNT on PDMS as substrate | For developing robotic hands (rehabilitation) Strain detecting needle for tissue characterization |

2019 [19] | ||

| Based on MWCNTs on thermoplastic urethane as substrate | Sensors integrated in gloves and bandages for assessing specific human functions | 2019 [20] | ||

| Based on MWCNTs on PDMS substrate | To measure pressure directly without the use of deformation materials. | 2019 [21] | ||

| Detection Target | ||||

| Gas sensors | Based on a resonant electromagnetic transducer in microstrip technology | Volatile Organic Compounds (VOCs) | 2019 [22] | |

| Based on dye functionalized matrix anchored onto MWCNTs ammonia | Sulphur dioxide and chlorine | 2018 [23] | ||

| Based on WxOy nano-bricks and MWCNTs | Ammonia gas | 2019 [24] | ||

| Transported Drugs | ||||

| Drug Targeting | Based on MWCNT and pH responsive gel of chitosan-coated magnetic nanocomposites | Doxorubicin (DOX) to U-87 Glioblastoma cells | 2019 [25] | |

| Based on stimuli responsive CNTs using Ag nanowires to stimulate the drug release from the core of NTs | Cisplatin | 2017 [26] | ||

| Based on electro responsive polymer-MWCNT hybrid hydrogel | Sucrose | 2013 [27] | ||

| Based on MWCNTs biodegradable, biocompatible nanocomposite hydrogel |

Diclofenac sodium | 2016 [28] | ||

| Cancer diagnosis and treatment | Based on MTX-loaded MWCNTs releasing drugs by enzymatic cleavage | Methotrexate to in vitro breast cells | 2010 [29] | |

| Based on DOX loaded dendrimer modified MWCNTs releasing drugs at low pH | DOX | 2013 [30] | ||

| Based on cationic MWCNTs-NH3þ for direct intertumoral injections | Apoptotic siRNA against polo-like kinase (siPLK1) in calu6 tumour xenografts | 2015 [31] | ||

| Target bacteria/Applications | ||||

| Antibacterial agents |

Based on chitosan/MWCNTs nanocomposites |

Enterococcus faecalis Staphylococcus epidermidis Escherichia coli |

[32,33,34,35,36,37,38] | |

| Based on Fe3O4/SWCNTs | E. coli | 2018 [39] | ||

| Based on Ag–Fe3O4/SWCNTs | N.R. | 2018 [40] | ||

| Based on CDX/Ag/MWCNTs | N.R. | 2014 [41] | ||

| Based on MWCNTs containing carboxylic functions | N.R. | 2015 [42] | ||

| Based on PA/graphene/CNTs | Staphylococcus aureus, E. coli | 2018,2012 [43,44] | ||

| Based on MWCNTs | Treatment of drinking water through removal and inactivation of virus and bacteria | 2011 [45] | ||

| Based on MWCNTs functionalized with mono-, di-, and tri-ethanolamine |

E. coli, Klebsiella pneumonia Pseudomonas aeruginosa Salmonella typhimurium, Bacillus subtilis S. aureus, Bacillus cereus Streptococcus pneumonia |

2014 [46] | ||

| Based on dispersion SWCNTs/TABM derivative with carboxy groups | E. coli, S. aureus | 2019 [47] | ||

| Target fungi | ||||

| Antifungal agents | Based on chitosan/MWCNTs |

Aspergillus niger, Candida trobicalis C. neoformans |

2000 [48] | |

| Based on functionalized CNTs |

A. niger, C. albicans, A. fumigatus, Penicillium chrysogenum Saccharomyces cerevisiae, Fusarium culmorum Microsporum canis, Trichophyton mentagrophytes T. rubrum, P. lilacinum |

2013 [49] | ||

| Based on dispersion SWCNTs/TABM derivative with carboxy groups | C. albicans | 2019 [47] | ||

References

- Ifijen, I.H.; Maliki, M.; Omorogbe, S.O.; Ibrahim, S.D. Incorporation of Metallic Nanoparticles Into Alkyd Resin: A Review of Their Coating Performance. In; 2022; pp. 338–349.

- Omorogbe, S.O.; Ikhuoria, E.U.; Ifijen, H.I.; Simo, A.; Aigbodion, A.; Maaza, M. Fabrication of Monodispersed Needle-Sized Hollow Core Polystyrene Microspheres. In; 2019; pp. 155–164.

- Ifijen, H.I.; Ikhuoria, E.U.; Omorogbe, S.O. Correlative Studies on the Fabrication of Poly(Styrene-Methyl-Methacrylate-Acrylic Acid) Colloidal Crystal Films. J Dispers Sci Technol 2019, 40, 1023–1030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ifijen, I.H.; Ikhuoria, E.U.; Omorogbe, S.O.; Aigbodion, A.I. Ordered Colloidal Crystals Fabrication and Studies on the Properties of Poly (Styrene–Butyl Acrylate–Acrylic Acid) and Polystyrene Latexes. In; 2019; pp. 125–135.

- Ifijen, I.H.; Maliki, M.; Ovonramwen, O.B.; Aigbodion, A.I.; Ikhuoria, E.U. Brilliant Coloured Monochromatic Photonic Crystals Films Generation from Poly (Styrene-Butyl Acrylate-Acrylic Acid) Latex. Journal of Applied Sciences and Environmental Management 2019, 23, 1661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omorogbe, S.O.; Aigbodion, A.I.; Ifijen, H.I.; Simo, A.; Ogbeide-Ihama, N.L.; Ikhuoria, E.U. Low-Temperature Synthesis of Superparamagnetic Fe3O4 Morphologies Tuned Using Oleic Acid as Crystal Growth Modifiers. In; 2020; pp. 619–631.

- Ifijen, I.H.; Ikhuoria, E.U.; Maliki, M.; Otabor, G.O.; Aigbodion, A.I. Nanostructured Materials: A Review on Its Application in Water Treatment. In; 2022; pp. 1172–1180.

- Ifijen, I.H.; Aghedo, O.N.; Odiachi, I.J.; Omorogbe, S.O.; Olu, E.L.; Onuguh, I.C. Nanostructured Graphene Thin Films: A Brief Review of Their Fabrication Techniques and Corrosion Protective Performance. In; 2022; pp. 366–377.

- Ciambelli, P.; La Guardia, G.; Vitale, L. Nanotechnology for Green Materials and Processes. In; 2020; pp. 97–116.

- SO, O.; AI, A.; EU, I.; IH, I. Impact of Varying the Concentration of Tetraethyl-OrthoSilicate on the Average Particle Diameter of Monodisperse Colloidal Silica Spheres. Chem Sci J 2018, 09. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ifijen, I.H.; Maliki, M.; Odiachi, I.J.; Aghedo, O.N.; Ohiocheoya, E.B. Review on Solvents Based Alkyd Resins and Water Borne Alkyd Resins: Impacts of Modification on Their Coating Properties. Chemistry Africa 2022, 5, 211–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ifijen, I.H.; Omonmhenle, S.I. Antimicrobial Properties of Carbon Nanotube: A Succinct Assessment. Biomedical Materials & Devices 2024, 2, 113–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anzar, N.; Hasan, R.; Tyagi, M.; Yadav, N.; Narang, J. Carbon Nanotube - A Review on Synthesis, Properties and Plethora of Applications in the Field of Biomedical Science. Sensors International 2020, 1, 100003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Q.; Gan, L.; Liu, J.; Yang, X. Carbon Dots Derived from Pea for Specifically Binding with Cryptococcus Neoformans. Anal Biochem 2020, 589, 113476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salari, S.; Jafari, S.M. Application of Nanofluids for Thermal Processing of Food Products. Trends Food Sci Technol 2020, 97, 100–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abd-Elsalam, K.A. Carbon Nanomaterials: 30 Years of Research in Agroecosystems. In Carbon Nanomaterials for Agri-Food and Environmental Applications; Elsevier, 2020; pp. 1–18.

- Iijima, S. Helical Microtubules of Graphitic Carbon. Nature 1991, 354, 56–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azizi-Lalabadi, M.; Hashemi, H.; Feng, J.; Jafari, S.M. Carbon Nanomaterials against Pathogens; the Antimicrobial Activity of Carbon Nanotubes, Graphene/Graphene Oxide, Fullerenes, and Their Nanocomposites. Adv Colloid Interface Sci 2020, 284, 102250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chong, Y.; Ge, C.; Fang, G.; Wu, R.; Zhang, H.; Chai, Z.; Chen, C.; Yin, J.-J. Light-Enhanced Antibacterial Activity of Graphene Oxide, Mainly via Accelerated Electron Transfer. Environ Sci Technol 2017, 51, 10154–10161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, S.; Mauter, M.S.; Elimelech, M. Physicochemical Determinants of Multiwalled Carbon Nanotube Bacterial Cytotoxicity. Environ Sci Technol 2008, 42, 7528–7534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haung, C.-F.; Chan, Y.-H.; Chen, L.-K.; Liu, C.-M.; Huang, W.-C.; Ou, S.-F.; Ou, K.-L.; Wang, D.-Y. Preparation, Characterization, and Properties of Anticoagulation and Antibacterial Films of Carbon-Based Nanowires Fabricated on Surfaces of Ti Implants. J Electrochem Soc 2013, 160, H392–H397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, E.-S.; Kim, Y.-O.; Ha, Y.-M.; Lim, D.; Hwang, J.Y.; Kim, J.; Park, M.; Cho, J.W.; Jung, Y.C. Antimicrobial Properties of Lignin-Decorated Thin Multi-Walled Carbon Nanotubes in Poly(Vinyl Alcohol) Nanocomposites. Eur Polym J 2018, 105, 79–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azizi-Lalabadi, M.; Hashemi, H.; Feng, J.; Jafari, S.M. Carbon Nanomaterials against Pathogens; the Antimicrobial Activity of Carbon Nanotubes, Graphene/Graphene Oxide, Fullerenes, and Their Nanocomposites. Adv Colloid Interface Sci 2020, 284, 102250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oyelami, A.O.; Semple, K.T. Impact of Carbon Nanomaterials on Microbial Activity in Soil. Soil Biol Biochem 2015, 86, 172–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maleki Dizaj, S.; Mennati, A.; Jafari, S.; Khezri, K.; Adibkia, K. Antimicrobial Activity of Carbon-Based Nanoparticles. Adv Pharm Bull 2015, 5, 19–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, S.; Pinault, M.; Pfefferle, L.D.; Elimelech, M. Single-Walled Carbon Nanotubes Exhibit Strong Antimicrobial Activity. Langmuir 2007, 23, 8670–8673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, S.; Herzberg, M.; Rodrigues, D.F.; Elimelech, M. Antibacterial Effects of Carbon Nanotubes: Size Does Matter! Langmuir 2008, 24, 6409–6413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Wang, B.; Gao, D.; Guan, M.; Zheng, L.; Ouyang, H.; Chai, Z.; Zhao, Y.; Feng, W. Broad-Spectrum Antibacterial Activity of Carbon Nanotubes to Human Gut Bacteria. Small 2013, 9, 2735–2746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfei, S.; Schito, G.C. Nanotubes: Carbon-Based Fibers and Bacterial Nano-Conduits Both Arousing a Global Interest and Conflicting Opinions. Fibers 2022, 10, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebbesen, T.W.; Ajayan, P.M. Large-Scale Synthesis of Carbon Nanotubes. Nature 1992, 358, 220–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eatemadi, A.; Daraee, H.; Karimkhanloo, H.; Kouhi, M.; Zarghami, N.; Akbarzadeh, A.; Abasi, M.; Hanifehpour, Y.; Joo, S.W. Carbon Nanotubes: Properties, Synthesis, Purification, and Medical Applications. Nanoscale Res Lett 2014, 9, 393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, T.; Nikolaev, P.; Rinzler, A.G.; Tomanek, D.; Colbert, D.T.; Smalley, R.E. Self-Assembly of Tubular Fullerenes. J Phys Chem 1995, 99, 10694–10697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, T.; Nikolaev, P.; Thess, A.; Colbert, D.T.; Smalley, R.E. Catalytic Growth of Single-Walled Nanotubes by Laser Vaporization. Chem Phys Lett 1995, 243, 49–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, M.; Ando, Y. Chemical Vapor Deposition of Carbon Nanotubes: A Review on Growth Mechanism and Mass Production. J Nanosci Nanotechnol 2010, 10, 3739–3758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neupane, S.; Lastres, M.; Chiarella, M.; Li, W.; Su, Q.; Du, G. Synthesis and Field Emission Properties of Vertically Aligned Carbon Nanotube Arrays on Copper. Carbon N Y 2012, 50, 2641–2650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inami, N.; Mohamed, M.A.; Shikoh, E.; Fujiwara, A. Synthesis-Condition Dependence of Carbon Nanotube Growth by Alcohol Catalytic Chemical Vapor Deposition Method. Sci Technol Adv Mater 2007, 8, 292–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishigami, N.; Ago, H.; Imamoto, K.; Tsuji, M.; Iakoubovskii, K.; Minami, N. Crystal Plane Dependent Growth of Aligned Single-Walled Carbon Nanotubes on Sapphire. J Am Chem Soc 2008, 130, 9918–9924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naha, S.; Puri, I.K. A Model for Catalytic Growth of Carbon Nanotubes. J Phys D Appl Phys 2008, 41, 065304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, S.; Naha, S.; Puri, I.K. Molecular Simulation of the Carbon Nanotube Growth Mode during Catalytic Synthesis. Appl Phys Lett 2008, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eftekhari, A.; Jafarkhani, P.; Moztarzadeh, F. High-Yield Synthesis of Carbon Nanotubes Using a Water-Soluble Catalyst Support in Catalytic Chemical Vapor Deposition. Carbon N Y 2006, 44, 1343–1345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Z.F.; Huang, Z.P.; Xu, J.W.; Wang, J.H.; Bush, P.; Siegal, M.P.; Provencio, P.N. Synthesis of Large Arrays of Well-Aligned Carbon Nanotubes on Glass. Science (1979) 1998, 282, 1105–1107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hata, K.; Futaba, D.N.; Mizuno, K.; Namai, T.; Yumura, M.; Iijima, S. Water-Assisted Highly Efficient Synthesis of Impurity-Free Single-Walled Carbon Nanotubes. Science (1979) 2004, 306, 1362–1364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Futaba, D.N.; Hata, K.; Yamada, T.; Hiraoka, T.; Hayamizu, Y.; Kakudate, Y.; Tanaike, O.; Hatori, H.; Yumura, M.; Iijima, S. Shape-Engineerable and Highly Densely Packed Single-Walled Carbon Nanotubes and Their Application as Super-Capacitor Electrodes. Nat Mater 2006, 5, 987–994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smiljanic, O.; Stansfield, B.L.; Dodelet, J.-P.; Serventi, A.; Désilets, S. Gas-Phase Synthesis of SWNT by an Atmospheric Pressure Plasma Jet. Chem Phys Lett 2002, 356, 189–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.S.; Cota-Sanchez, G.; Kingston, C.T.; Imris, M.; Simard, B.; Soucy, G. Large-Scale Production of Single-Walled Carbon Nanotubes by Induction Thermal Plasma. J Phys D Appl Phys 2007, 40, 2375–2387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, J.; Li, F.-F.; Lau, J.; González-Urbina, L.; Licht, S. One-Pot Synthesis of Carbon Nanofibers from CO 2. Nano Lett 2015, 15, 6142–6148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Service, R.F. Conjuring Chemical Cornucopias out of Thin Air. Science (1979) 2015, 349, 1160–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, L.; Saito, K.; Pan, C.; Williams, F.A.; Gordon, A.S. Nanotubes from Methane Flames. Chem Phys Lett 2001, 340, 237–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, L.; Saito, K.; Hu, W.; Chen, Z. Ethylene Flame Synthesis of Well-Aligned Multi-Walled Carbon Nanotubes. Chem Phys Lett 2001, 346, 23–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, H.M.; McKinnon, J.T. Nanoclusters Produced in Flames. J Phys Chem 1994, 98, 12815–12818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murr, L.E.; Bang, J.J.; Esquivel, E.V.; Guerrero, P.A.; Lopez, D.A. Carbon Nanotubes, Nanocrystal Forms, and Complex Nanoparticle Aggregates in Common Fuel-Gas Combustion Sources and the Ambient Air. Journal of Nanoparticle Research 2004, 6, 241–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vander Wal, R.L. Fe-Catalyzed Single-Walled Carbon Nanotube Synthesis within a Flame Environment. Combust Flame 2002, 130, 37–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saveliev, A. V.; Merchan-Merchan, W.; Kennedy, L.A. Metal Catalyzed Synthesis of Carbon Nanostructures in an Opposed Flow Methane Oxygen Flame. Combust Flame 2003, 135, 27–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Height, M.J.; Howard, J.B.; Tester, J.W.; Vander Sande, J.B. Flame Synthesis of Single-Walled Carbon Nanotubes. Carbon N Y 2004, 42, 2295–2307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sen, S.; Puri, I.K. Flame Synthesis of Carbon Nanofibres and Nanofibre Composites Containing Encapsulated Metal Particles. Nanotechnology 2004, 15, 264–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naha, S.; Sen, S.; De, A.K.; Puri, I.K. A Detailed Model for the Flame Synthesis of Carbon Nanotubes and Nanofibers. Proceedings of the Combustion Institute 2007, 31, 1821–1829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rathinavel, S.; Priyadharshini, K.; Panda, D. A Review on Carbon Nanotube: An Overview of Synthesis, Properties, Functionalization, Characterization, and the Application. Materials Science and Engineering: B 2021, 268, 115095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monthioux, M.; Kuznetsov, V.L. Who Should Be given the Credit for the Discovery of Carbon Nanotubes? Carbon N Y 2006, 44, 1621–1623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chernozatonskii, L.A. Carbon Nanotube Connectors and Planar Jungle Gyms. Phys Lett A 1992, 172, 173–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menon, M.; Srivastava, D. Carbon Nanotube “T Junctions”: Nanoscale Metal-Semiconductor-Metal Contact Devices. Phys Rev Lett 1997, 79, 4453–4456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, K.L.; Yan, X.H.; Guo, Y.D.; Xiao, Y. Electronic Transport Properties of Junctions between Carbon Nanotubes and Graphene Nanoribbons. Eur Phys J B 2011, 83, 487–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, P.J.F.; Suarez-Martinez, I.; Marks, N.A. The Structure of Junctions between Carbon Nanotubes and Graphene Shells. Nanoscale 2016, 8, 18849–18854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambin, Ph.; Vigneron, J.P.; Fonseca, A.; Nagy, J.B.; Lucas, A.A. Atomic Structure and Electronic Properties of a Bent Carbon Nanotube. Synth Met 1996, 77, 249–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimitrakakis, G.K.; Tylianakis, E.; Froudakis, G.E. Pillared Graphene: A New 3-D Network Nanostructure for Enhanced Hydrogen Storage. Nano Lett 2008, 8, 3166–3170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lalwani, G.; Kwaczala, A.T.; Kanakia, S.; Patel, S.C.; Judex, S.; Sitharaman, B. Fabrication and Characterization of Three-Dimensional Macroscopic All-Carbon Scaffolds. Carbon N Y 2013, 53, 90–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lalwani, G.; Gopalan, A.; D’Agati, M.; Srinivas Sankaran, J.; Judex, S.; Qin, Y.-X.; Sitharaman, B. Porous Three-Dimensional Carbon Nanotube Scaffolds for Tissue Engineering. J Biomed Mater Res A 2015, 103, 3212–3225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noyce, S.G.; Vanfleet, R.R.; Craighead, H.G.; Davis, R.C. High Surface-Area Carbon Microcantilevers. Nanoscale Adv 2019, 1, 1148–1154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, M.-F.; Lourie, O.; Dyer, M.J.; Moloni, K.; Kelly, T.F.; Ruoff, R.S. Strength and Breaking Mechanism of Multiwalled Carbon Nanotubes Under Tensile Load. Science (1979) 2000, 287, 637–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, B.; Locascio, M.; Zapol, P.; Li, S.; Mielke, S.L.; Schatz, G.C.; Espinosa, H.D. Measurements of Near-Ultimate Strength for Multiwalled Carbon Nanotubes and Irradiation-Induced Crosslinking Improvements. Nat Nanotechnol 2008, 3, 626–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, K.; Mickelson, W.; Kis, A.; Zettl, A. Buckling and Kinking Force Measurements on Individual Multiwalled Carbon Nanotubes. Phys Rev B 2007, 76, 195436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mingo, N.; Stewart, D.A.; Broido, D.A.; Srivastava, D. Phonon Transmission through Defects in Carbon Nanotubes from First Principles. Phys Rev B 2008, 77, 033418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumanek, B.; Janas, D. Thermal Conductivity of Carbon Nanotube Networks: A Review. J Mater Sci 2019, 54, 7397–7427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koziol, K.K.; Janas, D.; Brown, E.; Hao, L. Thermal Properties of Continuously Spun Carbon Nanotube Fibres. Physica E Low Dimens Syst Nanostruct 2017, 88, 104–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, S.; Myung, S. A Flexible Approach to Mobility. Nat Nanotechnol 2007, 2, 207–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Li, Q.; Xie, J.; Jin, Z.; Wang, J.; Li, Y.; Jiang, K.; Fan, S. Fabrication of Ultralong and Electrically Uniform Single-Walled Carbon Nanotubes on Clean Substrates. Nano Lett 2009, 9, 3137–3141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, X.; Chen, Z. Curved Pi-Conjugation, Aromaticity, and the Related Chemistry of Small Fullerenes (<C 60 ) and Single-Walled Carbon Nanotubes. Chem Rev 2005, 105, 3643–3696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anzar, N.; Hasan, R.; Tyagi, M.; Yadav, N.; Narang, J. Carbon Nanotube - A Review on Synthesis, Properties and Plethora of Applications in the Field of Biomedical Science. Sensors International 2020, 1, 100003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.U.; Reddy, K.R.; Snguanwongchai, T.; Haque, E.; Gomes, V.G. Polymer Brush Synthesis on Surface Modified Carbon Nanotubes via in Situ Emulsion Polymerization. Colloid Polym Sci 2016, 294, 1599–1610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Che, J.; Çagin, T.; Goddard, W.A. Thermal Conductivity of Carbon Nanotubes. Nanotechnology 2000, 11, 65–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smart, S.K.; Cassady, A.I.; Lu, G.Q.; Martin, D.J. The Biocompatibility of Carbon Nanotubes. Carbon N Y 2006, 44, 1034–1047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Negri, V.; Pacheco-Torres, J.; Calle, D.; López-Larrubia, P. Carbon Nanotubes in Biomedicine. Top Curr Chem 2020, 378, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamberti, M.; Pedata, P.; Sannolo, N.; Porto, S.; De Rosa, A.; Caraglia, M. Carbon Nanotubes: Properties, Biomedical Applications, Advantages and Risks in Patients and Occupationally-Exposed Workers. Int J Immunopathol Pharmacol 2015, 28, 4–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Rani, R.; Dilbaghi, N.; Tankeshwar, K.; Kim, K.-H. Carbon Nanotubes: A Novel Material for Multifaceted Applications in Human Healthcare. Chem Soc Rev 2017, 46, 158–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagai, H.; Toyokuni, S. Differences and Similarities between Carbon Nanotubes and Asbestos Fibers during Mesothelial Carcinogenesis: Shedding Light on Fiber Entry Mechanism. Cancer Sci 2012, 103, 1378–1390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aslan, S.; Loebick, C.Z.; Kang, S.; Elimelech, M.; Pfefferle, L.D.; Van Tassel, P.R. Antimicrobial Biomaterials Based on Carbon Nanotubes Dispersed in Poly(Lactic-Co-Glycolic Acid). Nanoscale 2010, 2, 1789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olivi, M.; Zanni, E.; De Bellis, G.; Talora, C.; Sarto, M.S.; Palleschi, C.; Flahaut, E.; Monthioux, M.; Rapino, S.; Uccelletti, D.; et al. Inhibition of Microbial Growth by Carbon Nanotube Networks. Nanoscale 2013, 5, 9023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Ng, A.K.; Xu, R.; Wei, J.; Tan, C.M.; Yang, Y.; Chen, Y. Antibacterial Action of Dispersed Single-Walled Carbon Nanotubes on Escherichia Coli and Bacillus Subtilis Investigated by Atomic Force Microscopy. Nanoscale 2010, 2, 2744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arias, L.R.; Yang, L. Inactivation of Bacterial Pathogens by Carbon Nanotubes in Suspensions. Langmuir 2009, 25, 3003–3012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, Y.-F.; Lee, H.-J.; Shen, Y.-S.; Tseng, S.-H.; Lee, C.-Y.; Tai, N.-H.; Chang, H.-Y. Toxicity Mechanism of Carbon Nanotubes on Escherichia Coli. Mater Chem Phys 2012, 134, 279–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleemi, M.A.; Fouladi, M.H.; Yong, P.V.C.; Wong, E.H. Elucidation of Antimicrobial Activity of Non-Covalently Dispersed Carbon Nanotubes. Materials 2020, 13, 1676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vassallo, J.; Besinis, A.; Boden, R.; Handy, R.D. The Minimum Inhibitory Concentration (MIC) Assay with Escherichia Coli: An Early Tier in the Environmental Hazard Assessment of Nanomaterials? Ecotoxicol Environ Saf 2018, 162, 633–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartono, M.R.; Kushmaro, A.; Chen, X.; Marks, R.S. Probing the Toxicity Mechanism of Multiwalled Carbon Nanotubes on Bacteria. Environmental Science and Pollution Research 2018, 25, 5003–5012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Nghiem, J.; Silverberg, G.J.; Vecitis, C.D. Semiquantitative Performance and Mechanism Evaluation of Carbon Nanomaterials as Cathode Coatings for Microbial Fouling Reduction. Appl Environ Microbiol 2015, 81, 4744–4755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Shashkov, E. V.; Galanzha, E.I.; Kotagiri, N.; Zharov, V.P. Photothermal Antimicrobial Nanotherapy and Nanodiagnostics with Self-assembling Carbon Nanotube Clusters. Lasers Surg Med 2007, 39, 622–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammad, M.R.; Ahmed, D.S.; Mohammed, M.K.A. Synthesis of Ag-Doped TiO2 Nanoparticles Coated with Carbon Nanotubes by the Sol–Gel Method and Their Antibacterial Activities. J Solgel Sci Technol 2019, 90, 498–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mocan, T.; Matea, C.T.; Pop, T.; Mosteanu, O.; Buzoianu, A.D.; Suciu, S.; Puia, C.; Zdrehus, C.; Iancu, C.; Mocan, L. Carbon Nanotubes as Anti-Bacterial Agents. Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences 2017, 74, 3467–3479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.-P.; Lin, I.-J.; Chen, C.-C.; Hsu, Y.-C.; Chang, C.-C.; Lee, M.-J. Delivery of Small Interfering RNAs in Human Cervical Cancer Cells by Polyethylenimine-Functionalized Carbon Nanotubes. Nanoscale Res Lett 2013, 8, 267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martincic, M.; Tobias, G. Filled Carbon Nanotubes in Biomedical Imaging and Drug Delivery. Expert Opin Drug Deliv 2015, 12, 563–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Wang, H.; Shen, S.; She, X.; Shi, W.; Chen, J.; Zhang, Q.; Hu, Y.; Pang, Z.; Jiang, X. Fibrin-Targeting Peptide CREKA-Conjugated Multi-Walled Carbon Nanotubes for Self-Amplified Photothermal Therapy of Tumor. Biomaterials 2016, 79, 46–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pasquini, L.M.; Hashmi, S.M.; Sommer, T.J.; Elimelech, M.; Zimmerman, J.B. Impact of Surface Functionalization on Bacterial Cytotoxicity of Single-Walled Carbon Nanotubes. Environ Sci Technol 2012, 46, 6297–6305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saleemi, M.A.; Kong, Y.L.; Yong, P.V.C.; Wong, E.H. An Overview of Antimicrobial Properties of Carbon Nanotubes-Based Nanocomposites. Adv Pharm Bull 2022, 12, 449–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaudhari, A.A.; Joshi, S.; Vig, K.; Sahu, R.; Dixit, S.; Baganizi, R.; Dennis, V.A.; Singh, S.R.; Pillai, S. A Three-Dimensional Human Skin Model to Evaluate the Inhibition of Staphylococcus Aureus by Antimicrobial Peptide-Functionalized Silver Carbon Nanotubes. J Biomater Appl 2019, 33, 924–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prabhu, S.; Poulose, E.K. Silver Nanoparticles: Mechanism of Antimicrobial Action, Synthesis, Medical Applications, and Toxicity Effects. Int Nano Lett 2012, 2, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z.; Wang, Z.; Li, S.; Yuan, X. Antimicrobial Strategies for Urinary Catheters. J Biomed Mater Res A 2019, 107, 445–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhari, A.A.; Ashmore, D.; Nath, S. deb; Kate, K.; Dennis, V.; Singh, S.R.; Owen, D.R.; Palazzo, C.; Arnold, R.D.; Miller, M.E.; et al. A Novel Covalent Approach to Bio-Conjugate Silver Coated Single Walled Carbon Nanotubes with Antimicrobial Peptide. J Nanobiotechnology 2016, 14, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Dalal, J.; Dahiya, S.; Punia, R.; Sharma, K.D.; Ohlan, A.; Maan, A.S. In Situ Decoration of Silver Nanoparticles on Single-Walled Carbon Nanotubes by Microwave Irradiation for Enhanced and Durable Anti-Bacterial Finishing on Cotton Fabric. Ceram Int 2019, 45, 1011–1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karumuri, A.K.; Oswal, D.P.; Hostetler, H.A.; Mukhopadhyay, S.M. Silver Nanoparticles Supported on Carbon Nanotube Carpets: Influence of Surface Functionalization. Nanotechnology 2016, 27, 145603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbinta-Patrascu, M.E.; Ungureanu, C.; Iordache, S.M.; Iordache, A.M.; Bunghez, I.-R.; Ghiurea, M.; Badea, N.; Fierascu, R.-C.; Stamatin, I. Eco-Designed Biohybrids Based on Liposomes, Mint–Nanosilver and Carbon Nanotubes for Antioxidant and Antimicrobial Coating. Materials Science and Engineering: C 2014, 39, 177–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Y.-N.; Gong, J.-L.; Zeng, G.-M.; Ou, X.-M.; Song, B.; Guo, M.; Zhang, J.; Liu, H.-Y. Antimicrobial Behavior Comparison and Antimicrobial Mechanism of Silver Coated Carbon Nanocomposites. Process Safety and Environmental Protection 2016, 102, 596–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.B.; Steadman, C.S.; Chaudhari, A.A.; Pillai, S.R.; Singh, S.R.; Ryan, P.L.; Willard, S.T.; Feugang, J.M. Proteomic Analysis of Antimicrobial Effects of Pegylated Silver Coated Carbon Nanotubes in Salmonella Enterica Serovar Typhimurium. J Nanobiotechnology 2018, 16, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, A.; Goswami, A.; Nain, S. Enhanced Antibacterial Activity and Photo-Remediation of Toxic Dyes Using Ag/SWCNT/PPy Based Nanocomposite with Core–Shell Structure. Appl Nanosci 2020, 10, 2255–2268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Xu, J.; Wang, Y.; Chen, C.; Gu, H.; Chai, Y.; Wang, Y. Silver Nanoparticles-Decorated and Mesoporous Silica Coated Single-Walled Carbon Nanotubes with an Enhanced Antibacterial Activity for Killing Drug-Resistant Bacteria. Nano Res 2020, 13, 389–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yun, H.; Kim, J.D.; Choi, H.C.; Lee, C.W. Antibacterial Activity of CNT-Ag and GO-Ag Nanocomposites Against Gram-Negative and Gram-Positive Bacteria. Bull Korean Chem Soc 2013, 34, 3261–3264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leid, J.G.; Ditto, A.J.; Knapp, A.; Shah, P.N.; Wright, B.D.; Blust, R.; Christensen, L.; Clemons, C.B.; Wilber, J.P.; Young, G.W.; et al. In Vitro Antimicrobial Studies of Silver Carbene Complexes: Activity of Free and Nanoparticle Carbene Formulations against Clinical Isolates of Pathogenic Bacteria. Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy 2012, 67, 138–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nepal, D.; Balasubramanian, S.; Simonian, A.L.; Davis, V.A. Strong Antimicrobial Coatings: Single-Walled Carbon Nanotubes Armored with Biopolymers. Nano Lett 2008, 8, 1896–1901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Upadhyayula, V.K.K.; Gadhamshetty, V. Appreciating the Role of Carbon Nanotube Composites in Preventing Biofouling and Promoting Biofilms on Material Surfaces in Environmental Engineering: A Review. Biotechnol Adv 2010, 28, 802–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levashov, P.A.; Sedov, S.A.; Shipovskov, S.; Belogurova, N.G.; Levashov, A. V. Quantitative Turbidimetric Assay of Enzymatic Gram-Negative Bacteria Lysis. Anal Chem 2010, 82, 2161–2163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, F.; Santos, C.M.; Vergara, R.A.M. V.; Tria, M.C.R.; Advincula, R.; Rodrigues, D.F. Antimicrobial Applications of Electroactive PVK-SWNT Nanocomposites. Environ Sci Technol 2012, 46, 1804–1810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aslan, S.; Deneufchatel, M.; Hashmi, S.; Li, N.; Pfefferle, L.D.; Elimelech, M.; Pauthe, E.; Van Tassel, P.R. Carbon Nanotube-Based Antimicrobial Biomaterials Formed via Layer-by-Layer Assembly with Polypeptides. J Colloid Interface Sci 2012, 388, 268–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goodwin, D.G.; Marsh, K.M.; Sosa, I.B.; Payne, J.B.; Gorham, J.M.; Bouwer, E.J.; Fairbrother, D.H. Interactions of Microorganisms with Polymer Nanocomposite Surfaces Containing Oxidized Carbon Nanotubes. Environ Sci Technol 2015, 49, 5484–5492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sah, U.; Sharma, K.; Chaudhri, N.; Sankar, M.; Gopinath, P. Antimicrobial Photodynamic Therapy: Single-Walled Carbon Nanotube (SWCNT)-Porphyrin Conjugate for Visible Light Mediated Inactivation of Staphylococcus Aureus. Colloids Surf B Biointerfaces 2018, 162, 108–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiraferri, A.; Vecitis, C.D.; Elimelech, M. Covalent Binding of Single-Walled Carbon Nanotubes to Polyamide Membranes for Antimicrobial Surface Properties. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces 2011, 3, 2869–2877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cajero-Zul, L.R.; López-Dellamary, F.A.; Gómez-Salazar, S.; Vázquez-Lepe, M.; Vera-Graziano, R.; Torres-Vitela, M.R.; Olea-Rodríguez, M.A.; Nuño-Donlucas, S.M. Evaluation of the Resistance to Bacterial Growth of Star-Shaped Poly(ε-Caprolactone)-Co-Poly(Ethylene Glycol) Grafted onto Functionalized Carbon Nanotubes Nanocomposites. J Biomater Sci Polym Ed 2019, 30, 163–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murugan, E.; Vimala, G. Effective Functionalization of Multiwalled Carbon Nanotube with Amphiphilic Poly(Propyleneimine) Dendrimer Carrying Silver Nanoparticles for Better Dispersability and Antimicrobial Activity. J Colloid Interface Sci 2011, 357, 354–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neelgund, G.M.; Oki, A. Deposition of Silver Nanoparticles on Dendrimer Functionalized Multiwalled Carbon Nanotubes: Synthesis, Characterization and Antimicrobial Activity. J Nanosci Nanotechnol 2011, 11, 3621–3629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neelgund, G.M.; Oki, A.; Luo, Z. Antimicrobial Activity of CdS and Ag2S Quantum Dots Immobilized on Poly(Amidoamine) Grafted Carbon Nanotubes. Colloids Surf B Biointerfaces 2012, 100, 215–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, L.; Stilwell, J.; Zhang, T.; Elboudwarej, O.; Jiang, H.; Selegue, J.P.; Cooke, P.A.; Gray, J.W.; Chen, F.F. Molecular Characterization of the Cytotoxic Mechanism of Multiwall Carbon Nanotubes and Nano-Onions on Human Skin Fibroblast. Nano Lett 2005, 5, 2448–2464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zardini, H.Z.; Davarpanah, M.; Shanbedi, M.; Amiri, A.; Maghrebi, M.; Ebrahimi, L. Microbial Toxicity of Ethanolamines—Multiwalled Carbon Nanotubes. J Biomed Mater Res A 2014, 102, 1774–1781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilbertson, L.M.; Goodwin, D.G.; Taylor, A.D.; Pfefferle, L.; Zimmerman, J.B. Toward Tailored Functional Design of Multi-Walled Carbon Nanotubes (MWNTs): Electrochemical and Antimicrobial Activity Enhancement via Oxidation and Selective Reduction. Environ Sci Technol 2014, 48, 5938–5945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, J.; Seo, Y.; Hwang, J.; Kim, J.; Jeong, Y.; Hwang, M. Antibacterial Activity and Cytotoxicity of Multi-Walled Carbon Nanotubes Decorated with Silver Nanoparticles. Int J Nanomedicine 2014, 4621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jung, J.H.; Hwang, G.B.; Lee, J.E.; Bae, G.N. Preparation of Airborne Ag/CNT Hybrid Nanoparticles Using an Aerosol Process and Their Application to Antimicrobial Air Filtration. Langmuir 2011, 27, 10256–10264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rusen, E.; Mocanu, A.; Nistor, L.C.; Dinescu, A.; Călinescu, I.; Mustăţea, G.; Voicu, Ş.I.; Andronescu, C.; Diacon, A. Design of Antimicrobial Membrane Based on Polymer Colloids/Multiwall Carbon Nanotubes Hybrid Material with Silver Nanoparticles. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces 2014, 6, 17384–17393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohan, R.; Shanmugharaj, A.M.; Sung Hun, R. An Efficient Growth of Silver and Copper Nanoparticles on Multiwalled Carbon Nanotube with Enhanced Antimicrobial Activity. J Biomed Mater Res B Appl Biomater 2011, 96B, 119–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sui, M.; Zhang, L.; Sheng, L.; Huang, S.; She, L. Synthesis of ZnO Coated Multi-Walled Carbon Nanotubes and Their Antibacterial Activities. Science of The Total Environment 2013, 452–453, 148–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karthika, V.; Arumugam, A. Synthesis and Characterization of MWCNT/TiO 2 /Au Nanocomposite for Photocatalytic and Antimicrobial Activity. IET Nanobiotechnol 2017, 11, 113–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirschfeld, J.; Akinoglu, E.M.; Wirtz, D.C.; Hoerauf, A.; Bekeredjian-Ding, I.; Jepsen, S.; Haddouti, E.-M.; Limmer, A.; Giersig, M. Long-Term Release of Antibiotics by Carbon Nanotube-Coated Titanium Alloy Surfaces Diminish Biofilm Formation by Staphylococcus Epidermidis. Nanomedicine 2017, 13, 1587–1593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grover, N.; Borkar, I. V.; Dinu, C.Z.; Kane, R.S.; Dordick, J.S. Laccase- and Chloroperoxidase-Nanotube Paint Composites with Bactericidal and Sporicidal Activity. Enzyme Microb Technol 2012, 50, 271–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesan, J.; Jayakumar, R.; Mohandas, A.; Bhatnagar, I.; Kim, S.-K. Antimicrobial Activity of Chitosan-Carbon Nanotube Hydrogels. Materials 2014, 7, 3946–3955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, N.A.; Al-Harby, N.F.; Almarshed, M.S. Synthesis and Characterization of Novel Trimellitic Anhydride Isothiocyanate-Cross Linked Chitosan Hydrogels Modified with Multi-Walled Carbon Nanotubes for Enhancement of Antimicrobial Activity. Int J Biol Macromol 2019, 132, 416–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ding, L.; Wang, H.; Liu, D.; Zeng, X.-A.; Mao, Y. Bacteria Capture and Inactivation with Functionalized Multi-Walled Carbon Nanotubes (MWCNTs). J Nanosci Nanotechnol 2020, 20, 2055–2062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levi-Polyachenko, N.; Young, C.; MacNeill, C.; Braden, A.; Argenta, L.; Reid, S. Eradicating Group A Streptococcus Bacteria and Biofilms Using Functionalised Multi-Wall Carbon Nanotubes. International Journal of Hyperthermia 2014, 30, 490–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, Y.; Park, I.S.; Lee, S.J.; Bae, T.S.; Watari, F.; Uo, M.; Lee, M.H. Aqueous Dispersion of Surfactant-Modified Multiwalled Carbon Nanotubes and Their Application as an Antibacterial Agent. Carbon N Y 2011, 49, 3663–3671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khazaee, M.; Ye, D.; Majumder, A.; Baraban, L.; Opitz, J.; Cuniberti, G. Non-Covalent Modified Multi-Walled Carbon Nanotubes: Dispersion Capabilities and Interactions with Bacteria. Biomed Phys Eng Express 2016, 2, 055008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhavan, O.; Azimirad, R.; Safa, S. Functionalized Carbon Nanotubes in ZnO Thin Films for Photoinactivation of Bacteria. Mater Chem Phys 2011, 130, 598–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amiri, A.; Zardini, H.Z.; Shanbedi, M.; Maghrebi, M.; Baniadam, M.; Tolueinia, B. Efficient Method for Functionalization of Carbon Nanotubes by Lysine and Improved Antimicrobial Activity and Water-Dispersion. Mater Lett 2012, 72, 153–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasnain, M.S.; Nayak, A.K. Regulatory Considerations of Carbon Nanotubes. In; 2019; pp. 103–106.

- Ma-Hock, L.; Treumann, S.; Strauss, V.; Brill, S.; Luizi, F.; Mertler, M.; Wiench, K.; Gamer, A.O.; van Ravenzwaay, B.; Landsiedel, R. Inhalation Toxicity of Multiwall Carbon Nanotubes in Rats Exposed for 3 Months. Toxicological Sciences 2009, 112, 468–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- wikipedia Toxicology of Carbon Nanotubes Available online:. Available online: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Toxicology_of_carbon_nanomaterials#:~:text=The%20toxicity%20of%20carbon%20nanotubes%20has%20been%20an,in%20evaluating%20the%20toxicity%20of%20this%20heterogeneous%20material. (accessed on 7 March 2025).

- Wang, H.; Wang, J.; Deng, X.; Sun, H.; Shi, Z.; Gu, Z.; Liu, Y.; Zhaoc, Y. Biodistribution of Carbon Single-Wall Carbon Nanotubes in Mice. J Nanosci Nanotechnol 2004, 4, 1019–1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, J.; Flahaut, E.; Cheng, S.H. Effect of Carbon Nanotubes on Developing Zebrafish ( Danio Rerio ) Embryos. Environ Toxicol Chem 2007, 26, 708–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.G.; Li, Q.N.; Xu, J.Y.; Cai, X.Q.; Liu, R.L.; Li, Y.J.; Ma, J.F.; Li, W.X. The Pulmonary Toxicity of Multi-Wall Carbon Nanotubes in Mice 30 and 60 Days After Inhalation Exposure. J Nanosci Nanotechnol 2009, 9, 1384–1387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scoville, C.; Cole, R.; Hogg, J.; Farooque, O.; Russel, A. Carbon Nanotubes. Available online: https://courses.cs.washington. edu/courses/csep590a/08sp/projects/CarbonNanotubes.pdf#:~:text=The%20structure%20of%20a%20carbon%20nanotube% 20is%20formed,and%20bonded%20together%20to%20form%20a%20carbon%20nanotube (accessed on 7 March 2025).

- Li, Y.; Wang, S.; Lv, Z.; Wang, Z.; Zhao, Y.; Xie, Y.; Xu, Y.; Qian, L.; Yang, Y.; Zhao, Z.; et al. Transforming the Synthesis of Carbon Nanotubes with Machine Learning Models and Automation. Matter 2025, 8, 101913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon-Deckers, A.; Gouget, B.; Mayne-L’Hermite, M.; Herlin-Boime, N.; Reynaud, C.; Carrière, M. In Vitro Investigation of Oxide Nanoparticle and Carbon Nanotube Toxicity and Intracellular Accumulation in A549 Human Pneumocytes. Toxicology 2008, 253, 137–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- PULSKAMP, K.; DIABATE, S.; KRUG, H. Carbon Nanotubes Show No Sign of Acute Toxicity but Induce Intracellular Reactive Oxygen Species in Dependence on Contaminants. Toxicol Lett 2007, 168, 58–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WICK, P.; MANSER, P.; LIMBACH, L.; DETTLAFFWEGLIKOWSKA, U.; KRUMEICH, F.; ROTH, S.; STARK, W.; BRUININK, A. The Degree and Kind of Agglomeration Affect Carbon Nanotube Cytotoxicity. Toxicol Lett 2007, 168, 121–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monteiro-Riviere, N.A.; Inman, A.O.; Wang, Y.Y.; Nemanich, R.J. Surfactant Effects on Carbon Nanotube Interactions with Human Keratinocytes. Nanomedicine 2005, 1, 293–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pantarotto, D.; Briand, J.-P.; Prato, M.; Bianco, A. Translocation of Bioactive Peptides across Cell Membranes by Carbon NanotubesElectronic Supplementary Information (ESI) Available: Details of the Synthesis and Characterization, Cell Culture, TEM, Epifluorescence and Confocal Microscopy Images of CNTs 1, 2 and Fluorescein. See Http://Www.Rsc.Org/Suppdata/Cc/B3/B311254c/. Chemical Communications. [CrossRef]

- Manna, S.K.; Sarkar, S.; Barr, J.; Wise, K.; Barrera, E. V.; Jejelowo, O.; Rice-Ficht, A.C.; Ramesh, G.T. Single-Walled Carbon Nanotube Induces Oxidative Stress and Activates Nuclear Transcription Factor-ΚB in Human Keratinocytes. Nano Lett 2005, 5, 1676–1684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shvedova, A.; Castranova, V.; Kisin, E.; Schwegler-Berry, D.; Murray, A.; Gandelsman, V.; Maynard, A.; Baron, P. Exposure to Carbon Nanotube Material: Assessment of Nanotube Cytotoxicity Using Human Keratinocyte Cells. J Toxicol Environ Health A 2003, 66, 1909–1926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shvedova, A.A.; Kisin, E.R.; Mercer, R.; Murray, A.R.; Johnson, V.J.; Potapovich, A.I.; Tyurina, Y.Y.; Gorelik, O.; Arepalli, S.; Schwegler-Berry, D.; et al. Unusual Inflammatory and Fibrogenic Pulmonary Responses to Single-Walled Carbon Nanotubes in Mice. American Journal of Physiology-Lung Cellular and Molecular Physiology 2005, 289, L698–L708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumortier, H.; Lacotte, S.; Pastorin, G.; Marega, R.; Wu, W.; Bonifazi, D.; Briand, J.-P.; Prato, M.; Muller, S.; Bianco, A. Functionalized Carbon Nanotubes Are Non-Cytotoxic and Preserve the Functionality of Primary Immune Cells. Nano Lett 2006, 6, 1522–1528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayes, C.M.; Liang, F.; Hudson, J.L.; Mendez, J.; Guo, W.; Beach, J.M.; Moore, V.C.; Doyle, C.D.; West, J.L.; Billups, W.E.; et al. Functionalization Density Dependence of Single-Walled Carbon Nanotubes Cytotoxicity in Vitro. Toxicol Lett 2006, 161, 135–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi Kam, N.W.; Jessop, T.C.; Wender, P.A.; Dai, H. Nanotube Molecular Transporters: Internalization of Carbon Nanotube−Protein Conjugates into Mammalian Cells. J Am Chem Soc 2004, 126, 6850–6851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fenoglio, I.; Tomatis, M.; Lison, D.; Muller, J.; Fonseca, A.; Nagy, J.B.; Fubini, B. Reactivity of Carbon Nanotubes: Free Radical Generation or Scavenging Activity? Free Radic Biol Med 2006, 40, 1227–1233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, Z.; Liu, Z.; Meng, J.; Meng, J.; Duan, J.; Xie, S.; Lu, X.; Zhu, Z.; Wang, C.; Chen, S.; et al. Carbon Nanotubes Enhance Cytotoxicity Mediated by Human Lymphocytes In Vitro. PLoS One 2011, 6, e21073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, D.; Tian, F.; Ozkan, C.S.; Wang, M.; Gao, H. Effect of Single Wall Carbon Nanotubes on Human HEK293 Cells. Toxicol Lett 2005, 155, 73–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, G.; Wang, H.; Yan, L.; Wang, X.; Pei, R.; Yan, T.; Zhao, Y.; Guo, X. Cytotoxicity of Carbon Nanomaterials: Single-Wall Nanotube, Multi-Wall Nanotube, and Fullerene. Environ Sci Technol 2005, 39, 1378–1383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pacurari, M.; Yin, X.J.; Zhao, J.; Ding, M.; Leonard, S.S.; Schwegler-Berry, D.; Ducatman, B.S.; Sbarra, D.; Hoover, M.D.; Castranova, V.; et al. Raw Single-Wall Carbon Nanotubes Induce Oxidative Stress and Activate MAPKs, AP-1, NF-ΚB, and Akt in Normal and Malignant Human Mesothelial Cells. Environ Health Perspect 2008, 116, 1211–1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kisin, E.R.; Murray, A.R.; Keane, M.J.; Shi, X.-C.; Schwegler-Berry, D.; Gorelik, O.; Arepalli, S.; Castranova, V.; Wallace, W.E.; Kagan, V.E.; et al. Single-Walled Carbon Nanotubes: Geno- and Cytotoxic Effects in Lung Fibroblast V79 Cells. J Toxicol Environ Health A 2007, 70, 2071–2079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francis, A.P.; Devasena, T. Toxicity of Carbon Nanotubes: A Review. Toxicol Ind Health 2018, 34, 200–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muller, J.; Huaux, F.; Moreau, N.; Misson, P.; Heilier, J.-F.; Delos, M.; Arras, M.; Fonseca, A.; Nagy, J.B.; Lison, D. Respiratory Toxicity of Multi-Wall Carbon Nanotubes. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 2005, 207, 221–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirano, S.; Kanno, S.; Furuyama, A. Multi-Walled Carbon Nanotubes Injure the Plasma Membrane of Macrophages. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 2008, 232, 244–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monteiro-Riviere, N.A.; Nemanich, R.J.; Inman, A.O.; Wang, Y.Y.; Riviere, J.E. Multi-Walled Carbon Nanotube Interactions with Human Epidermal Keratinocytes. Toxicol Lett 2005, 155, 377–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monteiro-Riviere, N.A.; Inman, A.O. Challenges for Assessing Carbon Nanomaterial Toxicity to the Skin. Carbon N Y 2006, 44, 1070–1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Liu, C.; Yang, D.; Zhang, H.; Xi, Z. Comparative Study of Cytotoxicity, Oxidative Stress and Genotoxicity Induced by Four Typical Nanomaterials: The Role of Particle Size, Shape and Composition. Journal of Applied Toxicology 2009, 29, 69–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, L.; Stilwell, J.; Zhang, T.; Elboudwarej, O.; Jiang, H.; Selegue, J.P.; Cooke, P.A.; Gray, J.W.; Chen, F.F. Molecular Characterization of the Cytotoxic Mechanism of Multiwall Carbon Nanotubes and Nano-Onions on Human Skin Fibroblast. Nano Lett 2005, 5, 2448–2464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soto, K.F.; Carrasco, A.; Powell, T.G.; Garza, K.M.; Murr, L.E. Comparative in Vitro Cytotoxicity Assessment of Some Manufacturednanoparticulate Materials Characterized by Transmissionelectron Microscopy. Journal of Nanoparticle Research 2005, 7, 145–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murr, L.E.; Garza, K.M.; Soto, K.F.; Carrasco, A.; Powell, T.G.; Ramirez, D.A.; Guerrero, P.A.; Lopez, D.A.; Venzor, J. Cytotoxicity Assessment of Some Carbon Nanotubes and Related Carbon Nanoparticle Aggregates and the Implications for Anthropogenic Carbon Nanotube Aggregates in the Environment. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2005, 2, 31–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bottini, M.; Bruckner, S.; Nika, K.; Bottini, N.; Bellucci, S.; Magrini, A.; Bergamaschi, A.; Mustelin, T. Multi-Walled Carbon Nanotubes Induce T Lymphocyte Apoptosis. Toxicol Lett 2006, 160, 121–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pantarotto, D.; Briand, J.-P.; Prato, M.; Bianco, A. Translocation of Bioactive Peptides across Cell Membranes by Carbon NanotubesElectronic Supplementary Information (ESI) Available: Details of the Synthesis and Characterization, Cell Culture, TEM, Epifluorescence and Confocal Microscopy Images of CNTs 1, 2 and Fluorescein. See Http://Www.Rsc.Org/Suppdata/Cc/B3/B311254c/. Chemical Communications. [CrossRef]

- Manna, S.K.; Sarkar, S.; Barr, J.; Wise, K.; Barrera, E. V.; Jejelowo, O.; Rice-Ficht, A.C.; Ramesh, G.T. Single-Walled Carbon Nanotube Induces Oxidative Stress and Activates Nuclear Transcription Factor-ΚB in Human Keratinocytes. Nano Lett 2005, 5, 1676–1684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, C.-W. Pulmonary Toxicity of Single-Wall Carbon Nanotubes in Mice 7 and 90 Days After Intratracheal Instillation. Toxicological Sciences 2003, 77, 126–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warheit, D.B. Comparative Pulmonary Toxicity Assessment of Single-Wall Carbon Nanotubes in Rats. Toxicological Sciences 2003, 77, 117–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Z.; Hulderman, T.; Salmen, R.; Chapman, R.; Leonard, S.S.; Young, S.-H.; Shvedova, A.; Luster, M.I.; Simeonova, P.P. Cardiovascular Effects of Pulmonary Exposure to Single-Wall Carbon Nanotubes. Environ Health Perspect 2007, 115, 377–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mutlu, G.M.; Budinger, G.R.S.; Green, A.A.; Urich, D.; Soberanes, S.; Chiarella, S.E.; Alheid, G.F.; McCrimmon, D.R.; Szleifer, I.; Hersam, M.C. Biocompatible Nanoscale Dispersion of Single-Walled Carbon Nanotubes Minimizes in Vivo Pulmonary Toxicity. Nano Lett 2010, 10, 1664–1670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, L.A.; Lauer, F.T.; Burchiel, S.W.; McDonald, J.D. Mechanisms for How Inhaled Multiwalled Carbon Nanotubes Suppress Systemic Immune Function in Mice. Nat Nanotechnol 2009, 4, 451–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muller, J.; Huaux, F.; Fonseca, A.; Nagy, J.B.; Moreau, N.; Delos, M.; Raymundo-Piñero, E.; Béguin, F.; Kirsch-Volders, M.; Fenoglio, I.; et al. Structural Defects Play a Major Role in the Acute Lung Toxicity of Multiwall Carbon Nanotubes: Toxicological Aspects. Chem Res Toxicol 2008, 21, 1698–1705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donaldson, K.; Aitken, R.; Tran, L.; Stone, V.; Duffin, R.; Forrest, G.; Alexander, A. Carbon Nanotubes: A Review of Their Properties in Relation to Pulmonary Toxicology and Workplace Safety. Toxicological Sciences 2006, 92, 5–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poland, C.A.; Duffin, R.; Kinloch, I.; Maynard, A.; Wallace, W.A.H.; Seaton, A.; Stone, V.; Brown, S.; MacNee, W.; Donaldson, K. Carbon Nanotubes Introduced into the Abdominal Cavity of Mice Show Asbestos-like Pathogenicity in a Pilot Study. Nat Nanotechnol 2008, 3, 423–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inoue, K.; Yanagisawa, R.; Koike, E.; Nishikawa, M.; Takano, H. Repeated Pulmonary Exposure to Single-Walled Carbon Nanotubes Exacerbates Allergic Inflammation of the Airway: Possible Role of Oxidative Stress. Free Radic Biol Med 2010, 48, 924–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobayashi, N.; Naya, M.; Ema, M.; Endoh, S.; Maru, J.; Mizuno, K.; Nakanishi, J. Biological Response and Morphological Assessment of Individually Dispersed Multi-Wall Carbon Nanotubes in the Lung after Intratracheal Instillation in Rats. Toxicology 2010, 276, 143–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morimoto, Y.; Hirohashi, M.; Ogami, A.; Oyabu, T.; Myojo, T.; Todoroki, M.; Yamamoto, M.; Hashiba, M.; Mizuguchi, Y.; Lee, B.W.; et al. Pulmonary Toxicity of Well-Dispersed Multi-Wall Carbon Nanotubes Following Inhalation and Intratracheal Instillation. Nanotoxicology 2012, 6, 587–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grubek-Jaworska, H.; Nejman, P.; Czumińska, K.; Przybyłowski, T.; Huczko, A.; Lange, H.; Bystrzejewski, M.; Baranowski, P.; Chazan, R. Preliminary Results on the Pathogenic Effects of Intratracheal Exposure to One-Dimensional Nanocarbons. Carbon N Y 2006, 44, 1057–1063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francis, A.P.; Ganapathy, S.; Palla, V.R.; Murthy, P.B.; Ramaprabhu, S.; Devasena, T. One Time Nose-Only Inhalation of MWCNTs: Exploring the Mechanism of Toxicity by Intermittent Sacrifice in Wistar Rats. Toxicol Rep 2015, 2, 111–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simeonova, P.P.; Erdely, A. Engineered Nanoparticle Respiratory Exposure and Potential Risks for Cardiovascular Toxicity: Predictive Tests and Biomarkers. Inhal Toxicol 2009, 21, 68–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pietroiusti, A.; Massimiani, M.; Fenoglio, I.; Colonna, M.; Valentini, F.; Palleschi, G.; Camaioni, A.; Magrini, A.; Siracusa, G.; Bergamaschi, A.; et al. Low Doses of Pristine and Oxidized Single-Wall Carbon Nanotubes Affect Mammalian Embryonic Development. ACS Nano 2011, 5, 4624–4633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Mu, Q.; Zhang, W.; Butch, E.R.; Snyder, S.E.; Yan, B. Repeated Administrations of Carbon Nanotubes in Male Mice Cause Reversible Testis Damage without Affecting Fertility. Nat Nanotechnol 2010, 5, 683–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Philbrook, N.A.; Walker, V.K.; Afrooz, A.R.M.N.; Saleh, N.B.; Winn, L.M. Investigating the Effects of Functionalized Carbon Nanotubes on Reproduction and Development in Drosophila Melanogaster and CD-1 Mice. Reproductive Toxicology 2011, 32, 442–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Møller, P.; Wils, R.S.; Di Ianni, E.; Gutierrez, C.A.T.; Roursgaard, M.; Jacobsen, N.R. Genotoxicity of Multi-Walled Carbon Nanotube Reference Materials in Mammalian Cells and Animals. Mutation Research/Reviews in Mutation Research 2021, 788, 108393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sargent, L.M.; Hubbs, A.F.; Young, S.-H.; Kashon, M.L.; Dinu, C.Z.; Salisbury, J.L.; Benkovic, S.A.; Lowry, D.T.; Murray, A.R.; Kisin, E.R.; et al. Single-Walled Carbon Nanotube-Induced Mitotic Disruption. Mutation Research/Genetic Toxicology and Environmental Mutagenesis 2012, 745, 28–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lash, L.H. Special Issue: Membrane Transporters in Toxicology. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 2005, 204, 197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, C.-W. Pulmonary Toxicity of Single-Wall Carbon Nanotubes in Mice 7 and 90 Days After Intratracheal Instillation. Toxicological Sciences 2003, 77, 126–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, A.R.; Kisin, E.; Leonard, S.S.; Young, S.H.; Kommineni, C.; Kagan, V.E.; Castranova, V.; Shvedova, A.A. Oxidative Stress and Inflammatory Response in Dermal Toxicity of Single-Walled Carbon Nanotubes. Toxicology 2009, 257, 161–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Orecchioni, M.; Bedognetti, D.; Sgarrella, F.; Marincola, F.M.; Bianco, A.; Delogu, L.G. Impact of Carbon Nanotubes and Graphene on Immune Cells. J Transl Med 2014, 12, 138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Svadlakova, T.; Holmannova, D.; Kolackova, M.; Malkova, A.; Krejsek, J.; Fiala, Z. Immunotoxicity of Carbon-Based Nanomaterials, Starring Phagocytes. Int J Mol Sci 2022, 23, 8889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kan, H.; Pan, D.; Castranova, V. Engineered Nanoparticle Exposure and Cardiovascular Effects: The Role of a Neuronal-Regulated Pathway. Inhal Toxicol 2018, 30, 335–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alidori, S.; Bowman, R.L.; Yarilin, D.; Romin, Y.; Barlas, A.; Mulvey, J.J.; Fujisawa, S.; Xu, K.; Ruggiero, A.; Riabov, V.; et al. Deconvoluting Hepatic Processing of Carbon Nanotubes. Nat Commun 2016, 7, 12343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, A.R.N.; Reddy, Y.N.; Krishna, D.R.; Himabindu, V. Multi Wall Carbon Nanotubes Induce Oxidative Stress and Cytotoxicity in Human Embryonic Kidney (HEK293) Cells. Toxicology 2010, 272, 11–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, G.; Wang, H.; Yan, L.; Wang, X.; Pei, R.; Yan, T.; Zhao, Y.; Guo, X. Cytotoxicity of Carbon Nanomaterials: Single-Wall Nanotube, Multi-Wall Nanotube, and Fullerene. Environ Sci Technol 2005, 39, 1378–1383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Facciolà, A.; Visalli, G.; La Maestra, S.; Ceccarelli, M.; D’Aleo, F.; Nunnari, G.; Pellicanò, G.F.; Di Pietro, A. Carbon Nanotubes and Central Nervous System: Environmental Risks, Toxicological Aspects and Future Perspectives. Environ Toxicol Pharmacol 2019, 65, 23–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, W.; McKinney, W.; Kashon, M.; Salmen, R.; Castranova, V.; Kan, H. The Influence of Inhaled Multi-Walled Carbon Nanotubes on the Autonomic Nervous System. Part Fibre Toxicol 2015, 13, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aragon, M.J.; Topper, L.; Tyler, C.R.; Sanchez, B.; Zychowski, K.; Young, T.; Herbert, G.; Hall, P.; Erdely, A.; Eye, T.; et al. Serum-Borne Bioactivity Caused by Pulmonary Multiwalled Carbon Nanotubes Induces Neuroinflammation via Blood–Brain Barrier Impairment. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2017, 114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gholamine, B.; Karimi, I.; Salimi, A.; Mazdarani, P.; Becker, L.A. Neurobehavioral Toxicity of Carbon Nanotubes in Mice. Toxicol Ind Health 2017, 33, 340–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Larner, S.F.; Wang, J.; Goodman, J.; O’Donoghue Altman, M.B.; Xin, M.; Wang, K.K.W. In Vitro Neurotoxicity Resulting from Exposure of Cultured Neural Cells to Several Types of Nanoparticles. J Cell Death 2017, 10, 117967071769452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Zheng, X.; Nicholas, J.; Humes, S.T.; Loeb, J.C.; Robinson, S.E.; Bisesi, J.H.; Das, D.; Saleh, N.B.; Castleman, W.L.; et al. Single-Walled Carbon Nanotubes Modulate Pulmonary Immune Responses and Increase Pandemic Influenza a Virus Titers in Mice. Virol J 2017, 14, 242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, E.-J.; Choi, J.; Kim, J.-H.; Lee, B.-S.; Yoon, C.; Jeong, U.; Kim, Y. Subchronic Immunotoxicity and Screening of Reproductive Toxicity and Developmental Immunotoxicity Following Single Instillation of HIPCO-Single-Walled Carbon Nanotubes: Purity-Based Comparison. Nanotoxicology 2016, 10, 1188–1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khang, D.; Lee, S.; Kim, S.-H. High Dispersity of Carbon Nanotubes Diminishes Immunotoxicity in Spleen. Int J Nanomedicine 2015, 2697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, W.; Bi, J.; Zhang, X.; Wang, J.; Wang, J.; Liu, P.; Li, Z.; Wu, W. Damaging Effects of Multi-Walled Carbon Nanotubes on Pregnant Mice with Different Pregnancy Times. Sci Rep 2014, 4, 4352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, J.; Cheng, S.H. Influence of Carbon Nanotube Length on Toxicity to Zebrafish Embryos. Int J Nanomedicine 2012, 3731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Zhang, F.; Sun, X.; Choi, K.-Y.; Niu, G.; Zhang, G.; Guo, J.; Lee, S.; Chen, X. The Genotype-Dependent Influence of Functionalized Multiwalled Carbon Nanotubes on Fetal Development. Biomaterials 2014, 35, 856–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, B.; Zhu, S.; Li, J.; Hui, X.; Wang, G.-X. The Developmental Toxicity, Bioaccumulation and Distribution of Oxidized Single Walled Carbon Nanotubes in Artemia Salina. Toxicol Res (Camb) 2018, 7, 897–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Mu, Q.; Zhang, W.; Butch, E.R.; Snyder, S.E.; Yan, B. Repeated Administrations of Carbon Nanotubes in Male Mice Cause Reversible Testis Damage without Affecting Fertility. Nat Nanotechnol 2010, 5, 683–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindberg, H.K.; Falck, G.C.-M.; Singh, R.; Suhonen, S.; Järventaus, H.; Vanhala, E.; Catalán, J.; Farmer, P.B.; Savolainen, K.M.; Norppa, H. Genotoxicity of Short Single-Wall and Multi-Wall Carbon Nanotubes in Human Bronchial Epithelial and Mesothelial Cells in Vitro. Toxicology 2013, 313, 24–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lettiero, B.; Andersen, A.J.; Hunter, A.C.; Moghimi, S.M. Complement System and the Brain: Selected Pathologies and Avenues toward Engineering of Neurological Nanomedicines. Journal of Controlled Release 2012, 161, 283–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moghimi, S.M.; Peer, D.; Langer, R. Reshaping the Future of Nanopharmaceuticals: Ad Iudicium. ACS Nano 2011, 5, 8454–8458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Davis, C.; Cai, W.; He, L.; Chen, X.; Dai, H. Circulation and Long-Term Fate of Functionalized, Biocompatible Single-Walled Carbon Nanotubes in Mice Probed by Raman Spectroscopy. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2008, 105, 1410–1415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Fernando, K.A.S.; Liu, J.; Wang, J.; Sun, H.; Liu, Y.; Chen, M.; Huang, Y.; Wang, X.; Wang, H.; et al. Covalently PEGylated Carbon Nanotubes with Stealth Character In Vivo. Small 2008, 4, 940–944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pondman, K.M.; Pednekar, L.; Paudyal, B.; Tsolaki, A.G.; Kouser, L.; Khan, H.A.; Shamji, M.H.; ten Haken, B.; Stenbeck, G.; Sim, R.B.; et al. Innate Immune Humoral Factors, C1q and Factor H, with Differential Pattern Recognition Properties, Alter Macrophage Response to Carbon Nanotubes. Nanomedicine 2015, 11, 2109–2118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayes, C.M.; Liang, F.; Hudson, J.L.; Mendez, J.; Guo, W.; Beach, J.M.; Moore, V.C.; Doyle, C.D.; West, J.L.; Billups, W.E.; et al. Functionalization Density Dependence of Single-Walled Carbon Nanotubes Cytotoxicity in Vitro. Toxicol Lett 2006, 161, 135–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, R.M.; Doudrick, K.; Franzi, L.M.; TeeSy, C.; Anderson, D.S.; Wu, Z.; Mitra, S.; Vu, V.; Dutrow, G.; Evans, J.E.; et al. Instillation versus Inhalation of Multiwalled Carbon Nanotubes: Exposure-Related Health Effects, Clearance, and the Role of Particle Characteristics. ACS Nano 2014, 8, 8911–8931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Sun, B.; Chen, C. Understanding the Toxicity of Carbon Nanotubes. Acc Chem Res 2013, 46, 702–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Li, W.; Li, Q.; Li, Y.; Li, Y.; Zhang, X.; Huang, Q. Effects of Serum Proteins on Intracellular Uptake and Cytotoxicity of Carbon Nanoparticles. Carbon N Y 2009, 47, 1351–1358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, X.; Sun, Z.; Wang, X.; Leng, X. An Innovative MWCNTs/DOX/TC Nanosystem for Chemo-Photothermal Combination Therapy of Cancer. Nanomedicine 2017, 13, 2271–2280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, Y.; Wang, R.; Hu, Y.; Sun, R.; Song, T.; Shi, X.; Yin, S. Stacking of Doxorubicin on Folic Acid-Targeted Multiwalled Carbon Nanotubes for in Vivo Chemotherapy of Tumors. Drug Deliv 2018, 25, 1607–1616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Awasthi, S.; De, S.; Pandey, S.K. Surface Grafting of Carbon Nanostructures. In Handbook of Functionalized Carbon Nanostructures. In Handbook of Functionalized Carbon Nanostructures; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2024; pp. 1–45. [Google Scholar]

- Rele, S.; Thakur, C.K.; Khan, F.; Baral, B.; Saini, V.; Karthikeyan, C.; Moorthy, N.S.H.N.; Jha, H.C. Curcumin Coating: A Novel Solution to Mitigate Inherent Carbon Nanotube Toxicity. J Mater Sci Mater Med 2024, 35, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, L.; Man, C.; Wang, H.; Lu, X.; Ma, Q.; Cai, Y.; Ma, W. PEGylated Multi-Walled Carbon Nanotubes for Encapsulation and Sustained Release of Oxaliplatin. Pharm Res 2013, 30, 412–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, P.M.; Bourgognon, M.; Wang, J.T.-W.; Al-Jamal, K.T. Functionalised Carbon Nanotubes: From Intracellular Uptake and Cell-Related Toxicity to Systemic Brain Delivery. Journal of Controlled Release 2016, 241, 200–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sohaebuddin, S.K.; Thevenot, P.T.; Baker, D.; Eaton, J.W.; Tang, L. Nanomaterial Cytotoxicity Is Composition, Size, and Cell Type Dependent. Part Fibre Toxicol 2010, 7, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heras, A.; Colina, A.; López-Palacios, J.; Ayala, P.; Sainio, J.; Ruiz, V.; Kauppinen, E.I. Electrochemical Purification of Carbon Nanotube Electrodes. Electrochem commun 2009, 11, 1535–1538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mercier, G.; Hérold, C.; Marêché, J.-F.; Cahen, S.; Gleize, J.; Ghanbaja, J.; Lamura, G.; Bellouard, C.; Vigolo, B. Selective Removal of Metal Impurities from Single Walled Carbon Nanotube Samples. New Journal of Chemistry 2013, 37, 790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pełech, I.; Narkiewicz, U.; Kaczmarek, A.; Jędrzejewska, A.; Pełech, R. Removal of Metal Particles from Carbon Nanotubes Using Conventional and Microwave Methods. Sep Purif Technol 2014, 136, 105–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madani, S.Y.; Mandel, A.; Seifalian, A.M. A Concise Review of Carbon Nanotube’s Toxicology. Nano Rev 2013, 4, 21521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sallam, A.A.; Ahmed, M.M.; El-Magd, M.A.; Magdy, A.; Ghamry, H.I.; Alshahrani, M.Y.; Abou El-Fotoh, M.F. Quercetin-Ameliorated, Multi-Walled Carbon Nanotubes-Induced Immunotoxic, Inflammatory, and Oxidative Effects in Mice. Molecules 2022, 27, 2117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, D.; Deng, X.; Ji, Z.; Shen, X.; Dong, L.; Wu, M.; Gu, T.; Liu, Y. Long-Term Hepatotoxicity of Polyethylene-Glycol Functionalized Multi-Walled Carbon Nanotubes in Mice. Nanotechnology 2010, 21, 175101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pérez-Luna, V.; Moreno-Aguilar, C.; Arauz-Lara, J.L.; Aranda-Espinoza, S.; Quintana, M. Interactions of Functionalized Multi-Wall Carbon Nanotubes with Giant Phospholipid Vesicles as Model Cellular Membrane System. Sci Rep 2018, 8, 17998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adenuga, A.A.; Truong, L.; Tanguay, R.L.; Remcho, V.T. Preparation of Water Soluble Carbon Nanotubes and Assessment of Their Biological Activity in Embryonic Zebrafish. Int J Biomed Nanosci Nanotechnol 2013, 3, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lay, C.L.; Liu, H.Q.; Tan, H.R.; Liu, Y. Delivery of Paclitaxel by Physically Loading onto Poly(Ethylene Glycol) (PEG)-Graftcarbon Nanotubes for Potent Cancer Therapeutics. Nanotechnology 2010, 21, 065101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naqvi, S.T.R.; Rasheed, T.; Hussain, D.; Najam ul Haq, M.; Majeed, S.; shafi, S.; Ahmed, N.; Nawaz, R. Modification Strategies for Improving the Solubility/Dispersion of Carbon Nanotubes. J Mol Liq 2020, 297, 111919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleemi, M.A.; Hosseini Fouladi, M.; Yong, P.V.C.; Chinna, K.; Palanisamy, N.K.; Wong, E.H. Toxicity of Carbon Nanotubes: Molecular Mechanisms, Signaling Cascades, and Remedies in Biomedical Applications. Chem Res Toxicol 2021, 34, 24–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barosova, H.; Karakocak, B.B.; Septiadi, D.; Petri-Fink, A.; Stone, V.; Rothen-Rutishauser, B. An In Vitro Lung System to Assess the Proinflammatory Hazard of Carbon Nanotube Aerosols. Int J Mol Sci 2020, 21, 5335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rele, S.; Thakur, C.K.; Khan, F.; Baral, B.; Saini, V.; Karthikeyan, C.; Moorthy, N.S.H.N.; Jha, H.C. Curcumin Coating: A Novel Solution to Mitigate Inherent Carbon Nanotube Toxicity. J Mater Sci Mater Med 2024, 35, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, P.-X.; Liu, C.; Cheng, H.-M. Purification of Carbon Nanotubes. Carbon N Y 2008, 46, 2003–2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.; Zhang, M. Biodegradation of Carbon Nanotubes by Macrophages. Front Mater 2019, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Yang, T.; Heng, C.; Zhou, Y.; Jiang, Z.; Qian, X.; Du, L.; Mao, S.; Yin, X.; Lu, Q. Quercetin Improves Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver by Ameliorating Inflammation, Oxidative Stress, and Lipid Metabolism in Db / Db Mice. Phytotherapy Research 2019, 33, 3140–3152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Petrillo, A.; Orrù, G.; Fais, A.; Fantini, M.C. Quercetin and Its Derivates as Antiviral Potentials: A Comprehensive Review. Phytotherapy Research 2022, 36, 266–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakanishi, J.; Morimoto, Y.; Ogura, I.; Kobayashi, N.; Naya, M.; Ema, M.; Endoh, S.; Shimada, M.; Ogami, A.; Myojyo, T.; et al. Risk Assessment of the Carbon Nanotube Group. Risk Analysis 2015, 35, 1940–1956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- KUMAR BABELE, P.; KUMAR VERMA, M.; KANT BHATIA, R. Carbon Nanotubes: A Review on Risks Assessment, Mechanism of Toxicity and Future Directives to Prevent Health Implication. BIOCELL 2021, 45, 267–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duraia, E.M.; Opoku, M.; Beall, G.W. Efficient Eco-Friendly Synthesis of Carbon Nanotubes over Graphite Nanosheets from Yellow Corn: A One-Step Green Approach. Sci Rep 2024, 14, 16405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, C.; E. Rider, A.; Jun Han, Z.; Kumar, S.; Levchenko, I.; Ostrikov, K. (Ken) Applications and Nanotoxicity of Carbon Nanotubes and Graphene in Biomedicine. J Nanomater 2012, 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gendron, D.; Bubak, G. Carbon Nanotubes and Graphene Materials as Xenobiotics in Living Systems: Is There a Consensus on Their Safety? J Xenobiot 2023, 13, 740–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zumwalde, R.D. Current Intelligence Bulletin 65: Occupational Exposure to Carbon Nanotubes and Nanofibers. 2013. [Google Scholar]

- European Union Eur-Lex Available online:. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=OJ:JOC_2022_229_R_0001 (accessed on 13 March 2025).

- EU-OSHA - The Swedish Work Environment Authority Carbon Nanotubes – Exposure, Toxicology and Protective Measures in the Work Environment.

- Hasnain, M.S.; Nayak, A.K. Regulatory Considerations of Carbon Nanotubes. In; 2019; pp. 103–106.

- Schulte, P.A.; Murashov, V.; Zumwalde, R.; Kuempel, E.D.; Geraci, C.L. Occupational Exposure Limits for Nanomaterials: State of the Art. Journal of Nanoparticle Research 2010, 12, 1971–1987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerr, R.; McHugh, M.; McCrory, M. HSE Management Standards and Stress-Related Work Outcomes. Occup Med (Chic Ill) 2009, 59, 574–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Types of CNTs | Synthesis method | Concentration | Species | Main findings | Refs. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SWCNTs | CO disproportionation | 5 µg/mL | E. coli | Releasing intracellular content due to irrecoverable outer membrane damage | [26] |

| SWCNTs | CO disproportionation | 5 µg/mL | E. coli | Microbial cells lost their cellular integrity | [27] |

| MWCNTs | CVD method | 5 µg/mL | E. coli | Many of the bacterial cells remain intact and preserve their outer membrane | [20] |

| SWCNTs/MWCNTs | CVD method | 20, 50, 100 µg/mL |

L. acidophilus, E. coli B. adolescentis, E. faecalis S. aureus |

Antimicrobial mechanism associated with length-dependent wrapping and diameter-dependent piercing upon microbial cell membrane damage and the release of intracellular contents | [28] |

| MWCNTs | Nanocycle productions | 1.5–100 mg/L | E. coli | Low microbial toxicity. | [91] |

| MWCNTs | - | - |

E. coli, B. subtilis P. aeruginosa |

2-log cell density reduction in viability of pathogens | [92] |

| DWCNTs/MWCNTs | NE scientific productions | 20/100 µg/mL |

S. aureus, P. aeruginosa K. pneumoniae, C. albicans |

MWNTs antimicrobial activity higher than DWNTs | [90] |

| MWCNTs | Nanotech Labs productions | 20 mg/20 mL | P. fluorescens | 44% of inactivated bacteria MWNTs showed a significant effect on the inhibition of microbial adhesion due to the electrochemical Potential |

[93] |

| SWCNTs | - | 5 µg/mL | E. coli, B. subtilis | No physical destruction was observed below 10 nN of applied force | [87] |

| SWCNT/DWCNT MWCNT | Electric arc discharge, and CCVD | 100 µg/mL |

S. aureus, P. aeruginosa, C. albicans |

Microbial death induced by the aggregation of CNTs trapped on the microbial cell surface | [86] |

| SWCNTs/MWCNTs | - | 0.2 mg/mL | E. coli | Control bacteria grow by laser-activated CNTs | [94] |

| SWCNT-OHs | - | 50 to 250 µg/mL | Salmonella | - 7log reduction in cell viability at 200-250 µ | [88] |

| Material blend | Concentration | Species | Main findings | Refs |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SWCNTs-OH, -COOH, -NH2 | 50-200 µg/mL | S. aureus, B. Subtilis, S. typhimurium | SWCNTs-OH and -COOH showed higher microbial inhibition rate (7-log reduction) than SWCNTs-NH2 | [88] |

| Ag-SWCNTs containing TP226, TP359, TP557 peptides | 5 µg/mL | S. aureus | In skin models treated with silver-SWCNTs antimicrobial activity of only 1-log reduction was observed | [102] |

| SWCNTs functionalized with DNA and LSZ | ~25 mg/L | S. aureus, M. lysodeikticus | DNA- and LSZ-SWCNTs caused 84% microbial reduction | [115] |

| SWCNTs-PLGA complexes | < 2% by weight | E. coli, S. epidermidis | SWCNTs-PLGA caused the 98% reduction of metabolic activity | [85] |

| SWCNTs- PVK nanocomposite | 3 wt.% | E. coli, B. subtilis | SWCNTs-PVK induced 90% and 94% of B. subtilis and E. coli inhibition in the planktonic cells and showed a significant reduction of biofilm formation | [118] |

| SWCNTs-PGA/PLL (layer-by-layer) |

< 2% by weight | E. coli, S. epidermidis | SWCNTs/PGA/PLL showed a 90% reduction of pathogens | [85] |

| Oxidized SWCNTs-PVOH) nanocomposite |

0-10% (w/w) | P. aeruginosa | O-SWCNTs-PVOH gradually decreased viability of cells with increasing in nanotubes loading | [120] |

| SWCNTs/porphyrin composite | 0.04 mg/mL | S. aureus | SWCNTs/porphyrin caused a visible light induced damage to the cell membrane | [121] |

| SWCNTs-PEG)/poly-(ε caprolactone) composites | 0.5-1.0 wt.% | P. aeruginosa, S. aureus | SWCNT/copolymer complex caused lower bacteria inhibition than pure polymer complex | [123] |

| SWCNTs-polyamide membranes |

0.1-0.2 mg/mL | E. coli | Nanocomposite inactivated the microbial cells by 60% after 1 h of contact time | [121] |

| Material blend | Concentration | Species | Main findings | Refs |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MWCNTs-OH, -COOH, -NH2 | 50-200 µg/mL |