Submitted:

19 March 2025

Posted:

20 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Strain and Culture Conditions

2.2. Strategies for Generation of Mutant and Complementation Assays

2.3. Southern Blotting Assay

2.4. RNA Extraction and qPCR Assays

2.5. Colony Growth, Conidiation Formation and Conidiophores Development

2.6. Evaluation of Pathogenicity, Hyphae Penetration and Incipient Cytorryhsis Assays

2.7. Cell Sensitivity Assay

2.8. Total Protein Extraction and Western Blotting Assays

2.9. Microscopy Assays

3.10. RNA Sequencing and Analysis

3. Results

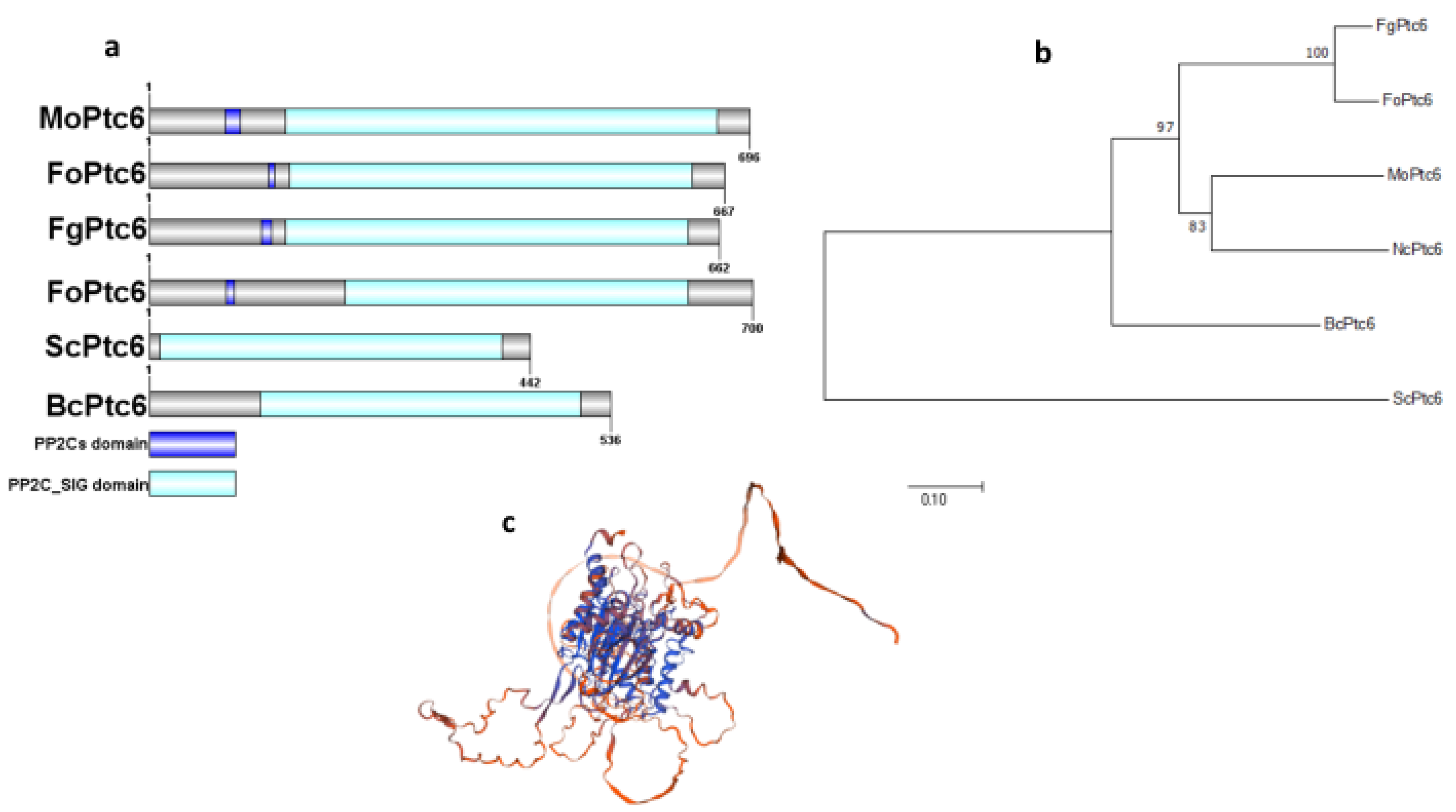

3.1. Identification, Domain Architecture, and Phylogenetic Analysis of MoPtc6

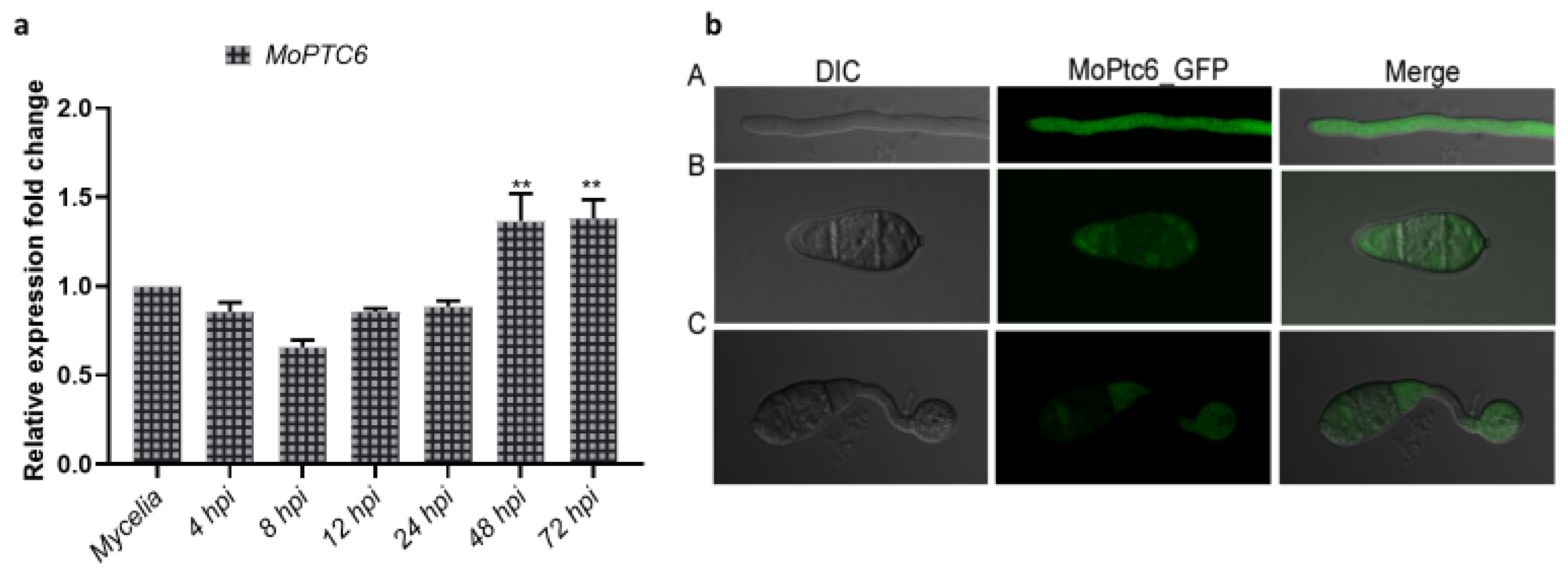

3.2. Expression Profile of MoPTC6 During Pathogen-Host Interaction and Subcellular Localization

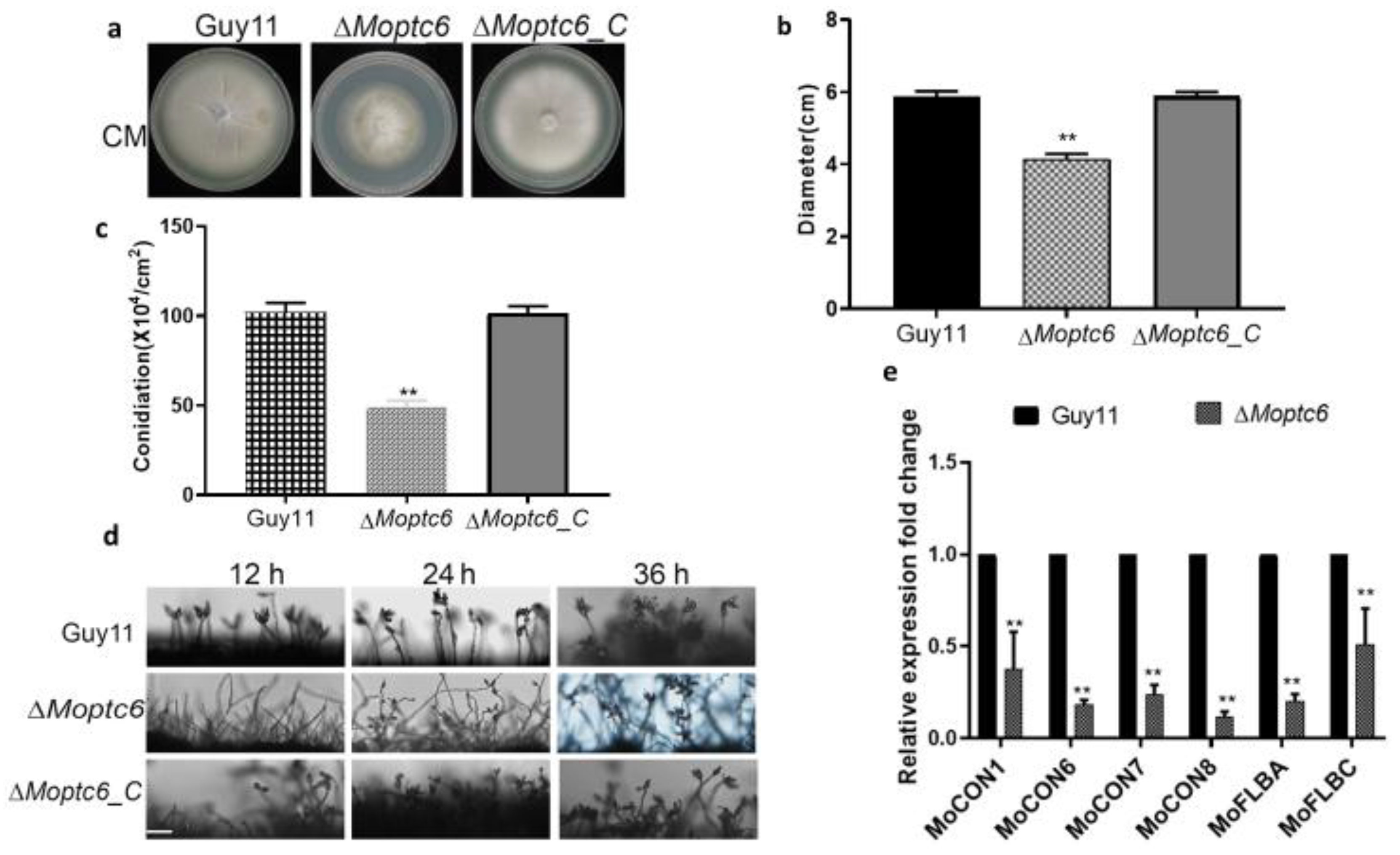

3.3. Effects of MoPTC6 Deletion on Fungal Growth, Conidiophore Development, and Sporulation

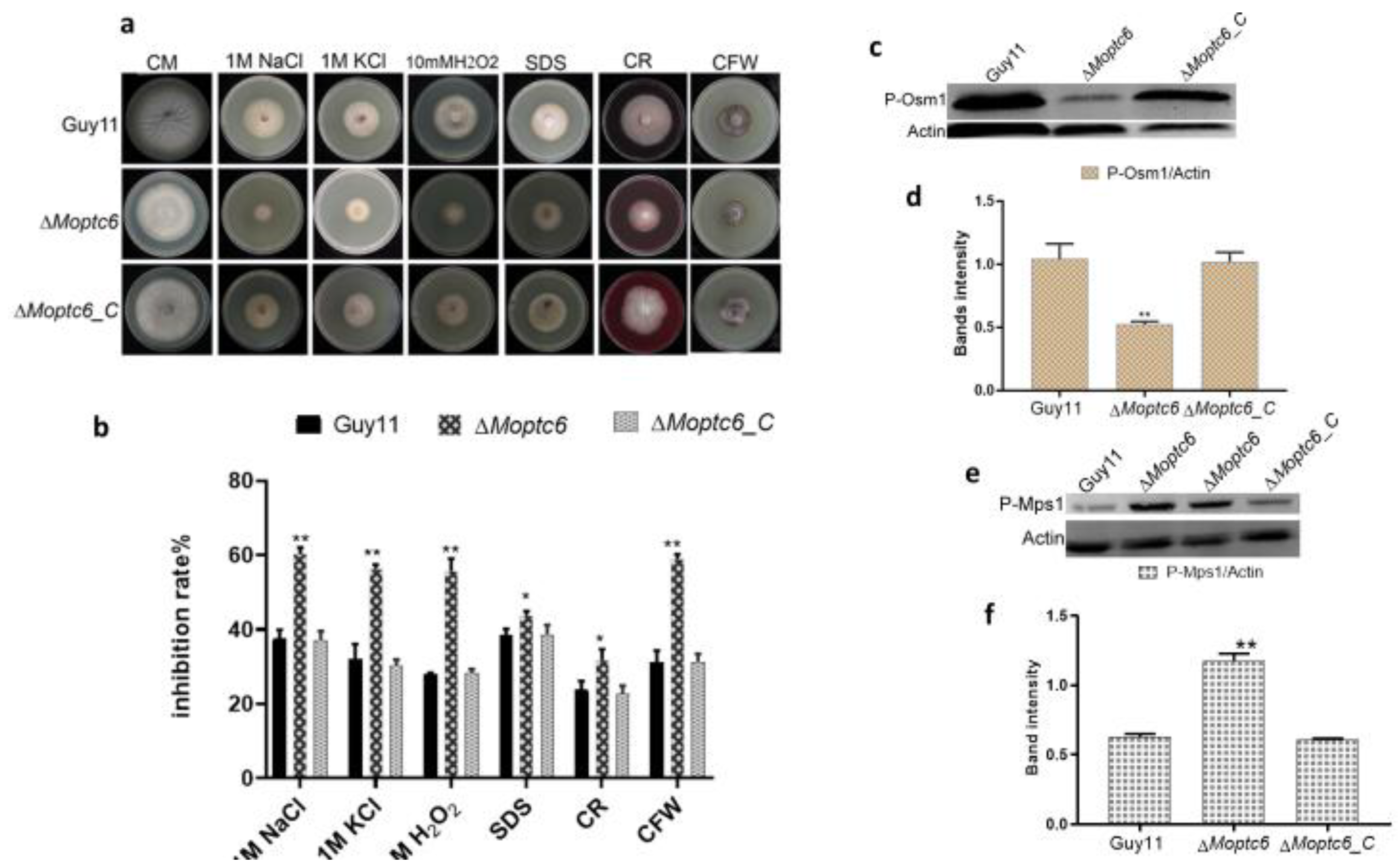

3.4. Sensitivity of ΔMoptc6 Mutant to Stress-Inducing Agents

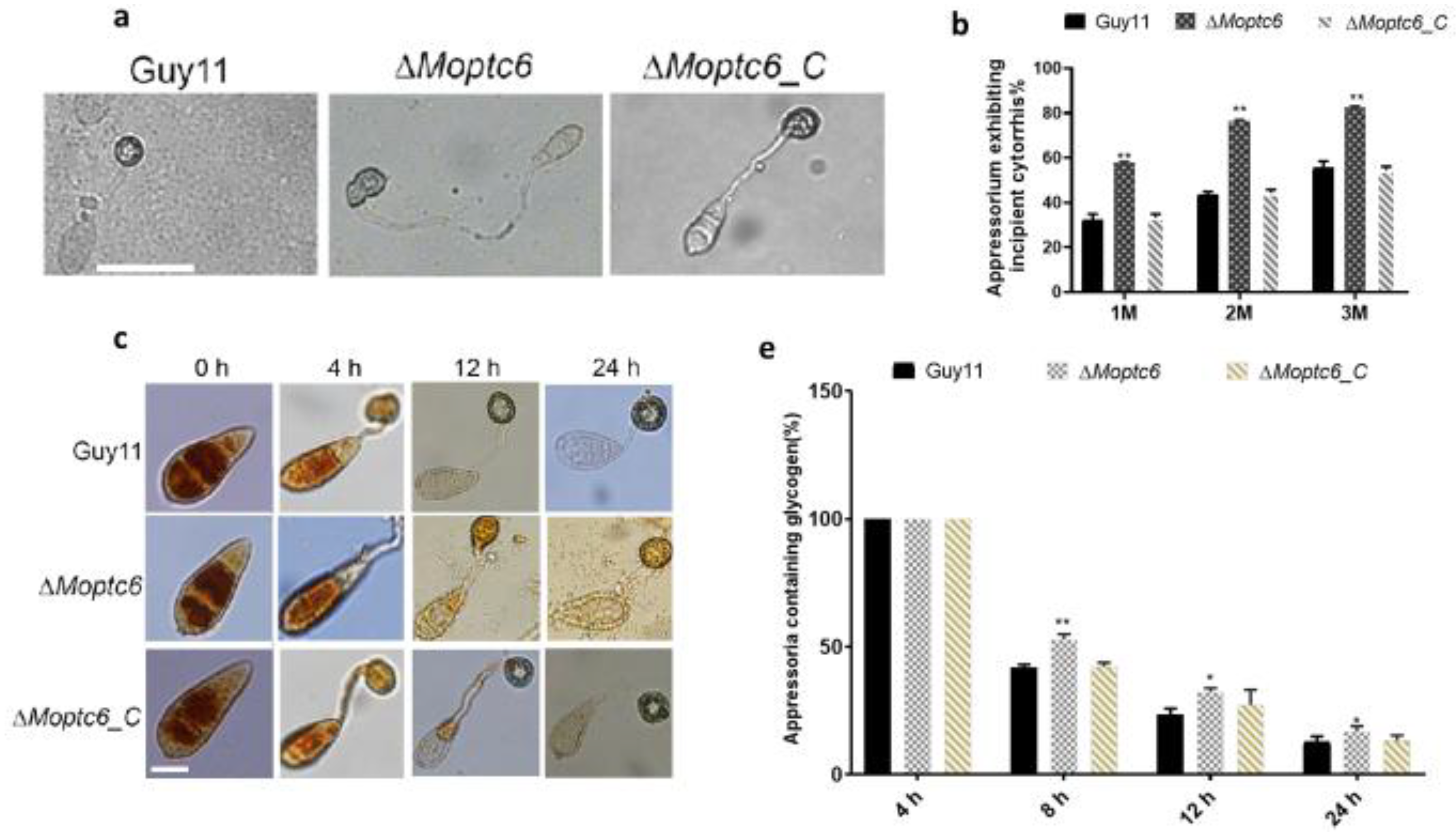

3.5. Deletion of MoPTC6 Attenuates Appressorium Turgor Pressure

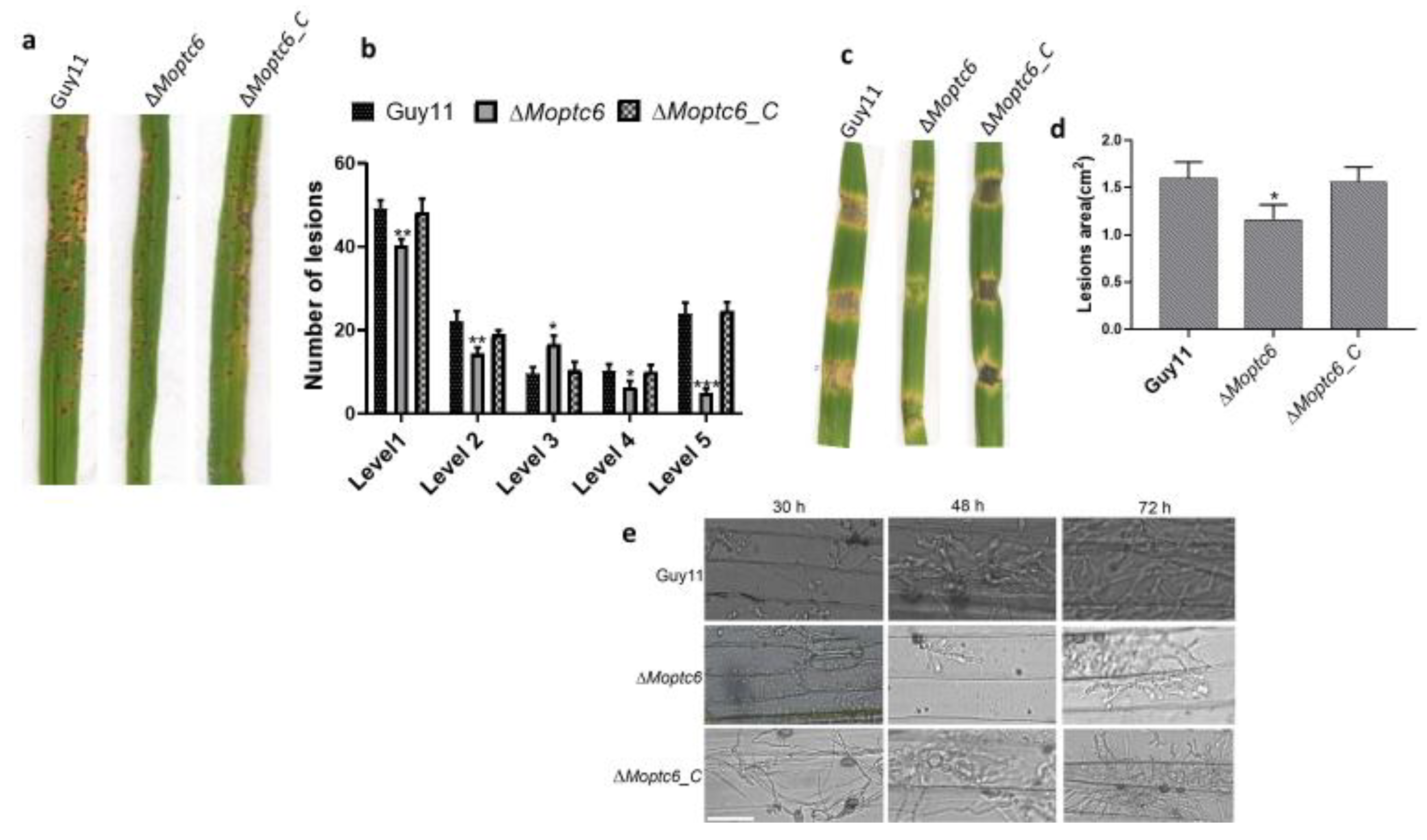

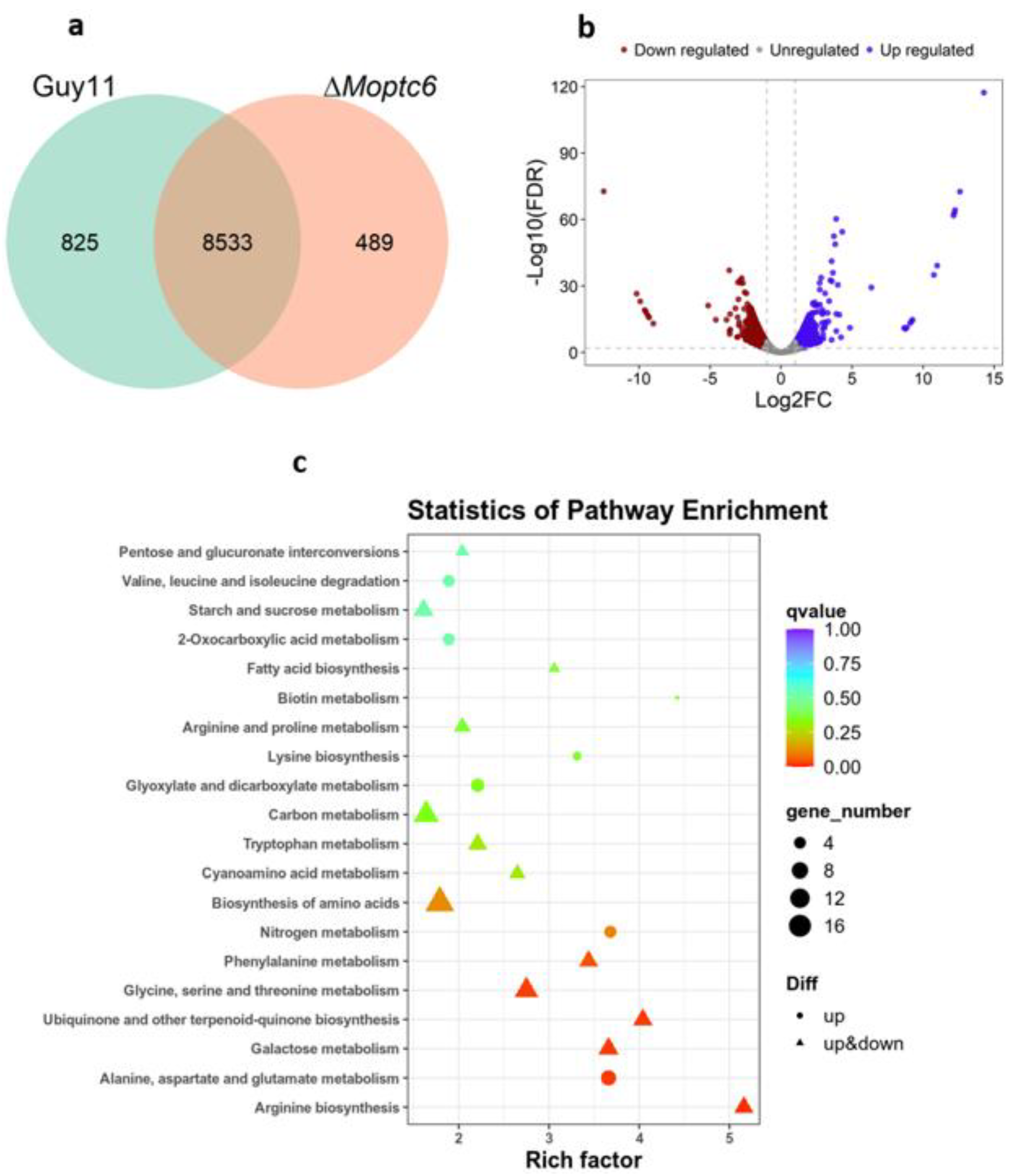

3.7. Influence of MoPTC6 Gene Deletion on Global Gene Expression

4. Discussion

5. Conclusion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Competing Interests

References

- Baudin, M.; Le Naour-Vernet, M.; Gladieux, P.; Tharreau, D.; Lebrun, M.H.; Lambou, K.; Leys, M.; Fournier, E.; Césari, S.; Kroj, T. Pyricularia oryzae: Lab star and field scourge. Mol Plant Pathol. 2024, 25, e13449.

- Wilson, R.A.; Talbot, N.J. Under pressure: investigating the biology of plant infection by Magnaporthe oryzae. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2009, 7, 185–195. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Anjago, W.M.; Zhou, T.; Zhang, H.; Shi, M.; Yang, T.; Zheng, H.; Wang, Z. Regulatory network of genes associated with stimuli sensing, signal transduction and physiological transformation of appressorium in Magnaporthe oryzae. Mycol 2018, 9, 211–222. [Google Scholar]

- Eseola, A.B.; Ryder, L.S.; Osés-Ruiz, M.; Findlay, K.; Yan, X.; Cruz-Mireles, N.; Molinari, C.; Garduño-Rosales, M.; Talbot, N.J. Investigating the cell and developmental biology of plant infection by the rice blast fungus Magnaporthe oryzae. Fungal Genet Biol. 2021, 154, 103562. [Google Scholar]

- Escalona-Montaño, A.R.; Zuñiga-Fabián, M.; Cabrera, N.; Mondragón-Flores, R.; Gómez-Sandoval, J.N.; Rojas-Bernabé, A.; González-Canto, A.; Gutierrez-Kobeh, L.; Perez-Montfort, R.; Becker, I. Protein serine/threonine phosphatase type 2C of Leishmania mexicana. Front Cell infect Microbiol. 2021, 11, 641356. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, Y. Serine/threonine phosphatases: mechanism through structure. Cell 2009, 139, 468–484. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Bradshaw, N.; Levdikov, V.M.; Zimanyi, C.M.; Gaudet, R.; Wilkinson, A.J.; Losick, R. A widespread family of serine/threonine protein phosphatases shares a common regulatory switch with proteasomal proteases. Elife. 2017, 6, e26111. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Z.; Yang, J.; Wang, Y.; Wang, F.; Mao, W.; He, Q.; Xu, J.; Wu, Z.; Mao, C. Protein phosphatase95 regulates phosphate homeostasis by affecting phosphate transporter trafficking in rice. Plant Cell. 2020, 32, 740–757. [Google Scholar]

- Rej, R.; Bretaudiere, J.P. Effects of metal ions on the measurement of alkaline phosphatase activity. Clin Chem. 1980, 26, 423–428. [Google Scholar]

- Warmka, J.; Hanneman, J.; Lee, J.; Amin, D.; Ota, I. Ptc1, a type 2C Ser/Thr phosphatase, inactivates the HOG pathway by dephosphorylating the mitogen-activated protein kinase Hog1. Mol Cell Biol. 2001, 21, 51–60. [Google Scholar]

- Sharmin, D.; Sasano, Y.; Sugiyama, M.; Harashima, S. Type 2C protein phosphatase Ptc6 participates in activation of the Slt2-mediated cell wall integrity pathway in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Biosci Bioeng. 2015, 119, 392–398. [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz, A.; Xu, X.; Carlson, M. Ptc1 protein phosphatase 2C contributes to glucose regulation of SNF1/AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. JBiol Chem. 2013, 288, 31052–31058. [Google Scholar]

- González, A.; Ruiz, A.; Serrano, R.; Ariño, J.; Casamayor, A. Transcriptional profiling of the protein phosphatase 2C family in yeast provides insights into the unique functional roles of Ptc1. J Biol Chem. 2006, 281, 35057–35069. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, J.; Yun, Y.; Yang, Q.; Shim, W.-B.; Wang, Z.; Ma, Z. A type 2C protein phosphatase FgPtc3 is involved in cell wall integrity, lipid metabolism, and virulence in Fusarium graminearum. PloS one. 2011, 6, e25311. [Google Scholar]

- Nunez-Rodriguez, J.C.; Ruiz-Roldán, C.; Lemos, P.; Membrives, S.; Hera, C. The phosphatase Ptc6 is involved in virulence and MAPK signalling in Fusarium oxysporum. Mol Plant pathol. 2020, 21, 206–217. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Q.; Jiang, J.; Mayr, C.; Hahn, M.; Ma, Z. Involvement of two type 2 C protein phosphatases B c P tc1 and B c P tc3 in the regulation of multiple stress tolerance and virulence of Botrytis cinerea. Envir Microbiol. 2013, 15, 2696–2711. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, L.; Yang, J.; Fan, F.; Zhang, D.; Wang, X. The Type 2C protein phosphatase FgPtc1p of the plant fungal pathogen Fusarium graminearum is involved in lithium toxicity and virulence. Molecular plant pathology 2010, 11, 277–282. [Google Scholar]

- Biregeya, J.; Anjago, W.M.; Pan, S.; Zhang, R.; Yang, Z.; Chen, M.; Felix, A.; Xu, H.; Lin, Y.; Nkurikiyimfura, O. Type 2C Protein Phosphatases MoPtc5 and MoPtc7 Are Crucial for Multiple Stress Tolerance, Conidiogenesis and Pathogenesis of Magnaporthe oryzae. J Fungi 2023, 9, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Anjago, W.M.; Biregeya, J.; Shi, M.; Chen, Y.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Z.; Hong, Y.; Chen, M. The Calcium Chloride Responsive Type 2C Protein Phosphatases Play Synergistic Roles in Regulating MAPK Pathways in Magnaporthe oryzae. J Fungi 2022, 8, 1287. [Google Scholar]

- Cai, Y.; Liu, X.; Shen, L.; Wang, N.; He, Y.; Zhang, H.; Wang, P.; Zhang, Z. Homeostasis of cell wall integrity pathway phosphorylation is required for the growth and pathogenicity of Magnaporthe oryzae. Mol Plant Pathol 2022, 2022. 23, 1214–1225. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, Z.; Yang, M.; Yang, G.; Zhang, B.; Cao, X.; Yuan, J.; Ge, F.; Wang, S. PP2C phosphatases Ptc1 and Ptc2 dephosphorylate PGK1 to regulate autophagy and aflatoxin synthesis in the pathogenic fungus Aspergillus flavus. Mbio. 2023, e00977–00923. [Google Scholar]

- Winkelströter, L.K.; Bom, V.L.P.; de Castro, P.A.; Ramalho, L.N.Z.; Goldman, M.H.S.; Brown, N.A.; Rajendran, R.; Ramage, G.; Bovier, E.; Dos Reis, T.F. H igh osmolarity glycerol response PtcB phosphatase is important for Aspergillus fumigatus virulence. Mol Microbiol. 2015, 96, 42–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, Y.; Qin, Y.; Zhu, D.; Shan, A.; Feng, J. Identification and characterization of PP2C phosphatase SjPtc1 in Schistosoma japonicum. Parasitol intern 2018, 67, 213–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kamada, R.; Kudoh, F.; Ito, S.; Tani, I.; Janairo, J.I.B.; Omichinski, J.G.; Sakaguchi, K. Metal-dependent Ser/Thr protein phosphatase PPM family: Evolution, structures, diseases and inhibitors. Pharmacol Therap 2020, 215, 107622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rogers, J.P.; Beuscher; Flajolet, M.; McAvoy, T.; Nairn, A.C.; Olson, A.J.; Greengard, P. Discovery of protein phosphatase 2C inhibitors by virtual screening. J Med Chem. 2006, 49, 1658-1667.

- Peri, K.V.R.; Faria-Oliveira, F.; Larsson, A.; Plovie, A.; Papon, N.; Geijer, C. Split-marker-mediated genome editing improves homologous recombination frequency in the CTG clade yeast Candida intermedia. FEMS yeast Res. 2023, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, B.; Xiao, J.; Dai, L.; Huang, Y.; Mao, Z.; Lin, R.; Yao, Y.; Xie, B. Development of a high-efficiency gene knockout system for Pochonia chlamydosporia. Microbiol Res. 2015, 170, 18–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryksin, A.V.; Matsumura, I. Overlap extension PCR cloning: a simple and reliable way to create recombinant plasmids. Biotech. 2010, 48, 463–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ning, Y.; Hu, B.; Yu, H.; Liu, X.; Jiao, B.; Lu, X. Optimization of Protoplast Preparation and Establishment of Genetic Transformation System of an Arctic-Derived Fungus Eutypella sp. Front Microbiol. 2022, 13, 769008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talbot, N.J.; Ebbole, D.J.; Hamer, J.E. Identification and characterization of MPG1, a gene involved in pathogenicity from the rice blast fungus Magnaporthe grisea. Plant Cell. 1993, 5, 1575–1590. [Google Scholar]

- Nakayashiki, H.; Hanada, S.; Quoc, N.B.; Kadotani, N.; Tosa, Y.; Mayama, S. RNA silencing as a tool for exploring gene function in ascomycete fungi. Fungal Genet Biol. 2005, 42, 275–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hattori, N.; Ushijima, T. Analysis of gene-specific DNA methylation. Handbook of epigenetics 2017, 113–123. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, J.-R.; Hamer, J.E. MAP kinase and cAMP signaling regulate infection structure formation and pathogenic growth in the rice blast fungus Magnaporthe grisea. Genes Dev. 1996, 10, 2696–2706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tripathy, S.K.; Maharana, M.; Ithape, D.M.; Lenka, D.; Mishra, D.; Prusti, A.; Swain, D.; Mohanty, M.R.; Raj, K.R. Exploring rapid and efficient protocol for isolation of fungal DNA. Intern Curr Microbiol Appl Sci. 2017, 6, 951–960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huhndorf, S.M.; Greif, M.; Mugambi, G.K.; Miller, A.N. Two new genera in the Magnaporthaceae, a new addition to Ceratosphaeria and two new species of Lentomitella. Mycol. 2008, 100, 940–955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Love, M.I.; Huber, W.; Anders, S. Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol. 2014, 15, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.; Langmead, B.; Salzberg, S.L. HISAT: a fast spliced aligner with low memory requirements. Nat Meth. 2015, 12, 357–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryder, L.S.; Talbot, N.J. Regulation of appressorium development in pathogenic fungi. Curr opin Plant Biol. 2015, 26, 8–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aron, O.; Otieno, F.J.; Tijjani, I.; Yang, Z.; Xu, H.; Weng, S.; Guo, J.; Lu, S.; Wang, Z.; Tang, W. De novo purine nucleotide biosynthesis mediated by MoAde4 is required for conidiation, host colonization and pathogenicity in Magnaporthe oryzae. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2022, 106, 5587–5602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arino, J.; Casamayor, A.; González, A. Type 2C protein phosphatases in fungi. Eukaryot Cell. 2011, 10, 21–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albataineh, M.T.; Kadosh, D. Regulatory roles of phosphorylation in model and pathogenic fungi. Sabouraudia. 2015, 54, 333–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Y.-Y.; Qi, Y.-L.; Cai, L. Induction of sporulation in plant pathogenic fungi. Mycol. 2012, 3, 195–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagliarulo, C.; Sateriale, D.; Scioscia, E.; De Tommasi, N.; Colicchio, R.; Pagliuca, C.; Scaglione, E.; Jussila, J.; Makkonen, J.; Salvatore, P. Growth, survival and spore formation of the pathogenic aquatic oomycete Aphanomyces astaci and fungus Fusarium avenaceum are inhibited by Zanthoxylum rhoifolium bark extracts in vitro. Fishes. 2018, 3, 12. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Z.; Wang, Q.; Li, Y.; Huang, P.; Liao, J.; Wang, J.; Li, H.; Cai, Y.; Wang, J.; Liu, X. A multilayered regulatory network mediated by protein phosphatase 4 controls carbon catabolite repression and de-repression in Magnaporthe oryzae. Commun Biol. 2025, 8, 130. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, K.S.; Lee, Y.H. Gene expression profiling during conidiation in the rice blast pathogen Magnaporthe oryzae. PLoS One. 2012, 7, e43202. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, A.J.; Budge, S.; Kaloriti, D.; Tillmann, A.; Jacobsen, M.D.; Yin, Z.; Ene, I.V.; Bohovych, I.; Sandai, D.; Kastora, S. Stress adaptation in a pathogenic fungus. J Exper Biol. 2014, 217, 144–155. [Google Scholar]

- Nikolaou, E.; Agrafioti, I.; Stumpf, M.; Quinn, J.; Stansfield, I.; Brown, A.J. Phylogenetic diversity of stress signalling pathways in fungi. BMC Evol Biol. 2009, 9, 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Feng, W.; Yin, Z.; Wu, H.; Liu, P.; Liu, X.; Liu, M.; Yu, R.; Gao, C.; Zhang, H.; Zheng, X.; et al. Balancing of the mitotic exit network and cell wall integrity signaling governs the development and pathogenicity in Magnaporthe oryzae. PLoS Pathog. 2021, 17, e1009080. [Google Scholar]

- Su, X.; Yan, X.; Chen, X.; Guo, M.; Xia, Y.; Cao, Y. Calcofluor white hypersensitive proteins contribute to stress tolerance and pathogenicity in entomopathogenic fungus, Metarhizium acridum. Pest manag sci. 2021, 77, 1915–1924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshimi, A.; Miyazawa, K.; Kawauchi, M.; Abe, K. Cell Wall Integrity and Its Industrial Applications in Filamentous Fungi. J Fungi. 2022, 8. [Google Scholar]

- Calcáneo-Hernández, G.; Landeros-Jaime, F.; Cervantes-Chávez, J.A.; Mendoza-Mendoza, A.; Esquivel-Naranjo, E.U. Osmotic Stress Responses, Cell Wall Integrity, and Conidiation Are Regulated by a Histidine Kinase Sensor in Trichoderma atroviride. J Fungi. 2023, 9. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.; Gong, X.; Li, M.; Si, H.; Zhou, Q.; Liu, X.; Fan, Y.; Zhang, X.; Han, J.; Gu, S.; et al. Effect of Osmotic Stress on the Growth, Development and Pathogenicity of Setosphaeria turcica. Front Microbiol. 2021, 12, 706349. [Google Scholar]

- Duran, R.; Cary, J.W.; Calvo, A.M. Role of the osmotic stress regulatory pathway in morphogenesis and secondary metabolism in filamentous fungi. Toxins. 2010, 2, 367–381. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Chaudhary, P.; Janmeda, P.; Docea, A.O.; Yeskaliyeva, B.; Abdull Razis, A.F.; Modu, B.; Calina, D.; Sharifi-Rad, J. Oxidative stress, free radicals and antioxidants: potential crosstalk in the pathophysiology of human diseases. Front Chem. 2023, 11, 1158198. [Google Scholar]

- Bai, Z.; Harvey, L.M.; McNeil, B. Oxidative stress in submerged cultures of fungi. Crit Rev Biotechnol. 2003, 23, 267–302. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Simaan, H.; Lev, S.; Horwitz, B.A. Oxidant-Sensing Pathways in the Responses of Fungal Pathogens to Chemical Stress Signals. Front Microbiol. 2019, 10, 567. [Google Scholar]

- Segmüller, N.; Ellendorf, U.; Tudzynski, B.; Tudzynski, P. BcSAK1, a stress-activated mitogen-activated protein kinase, is involved in vegetative differentiation and pathogenicity in Botrytis cinerea. Eukaryot Cell 2007, 6, 211–221. [Google Scholar]

- Tatebayashi, K.; Yamamoto, K.; Tomida, T.; Nishimura, A.; Takayama, T.; Oyama, M.; Kozuka-Hata, H.; Adachi-Akahane, S.; Tokunaga, Y.; Saito, H. Osmostress enhances activating phosphorylation of Hog1 MAP kinase by mono-phosphorylated Pbs2 MAP2K. Embo j 2020, 39, e103444. [Google Scholar]

- Stępień, Ł.; Lalak-Kańczugowska, J. Signaling pathways involved in virulence and stress response of plant-pathogenic Fusarium species. Fungal Biol Rev. 2021, 35, 27–39. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, Z.; Tang, W.; Wang, J.; Liu, X.; Yang, L.; Gao, C.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, H.; Zheng, X.; Wang, P.; et al. Phosphodiesterase MoPdeH targets MoMck1 of the conserved mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinase signalling pathway to regulate cell wall integrity in rice blast fungus Magnaporthe oryzae. Mol Plant Pathol 2016, 17, 654–668. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X.; Wang, Z.; Jiang, C.; Xu, J.R. Regulation of biotic interactions and responses to abiotic stresses by MAP kinase pathways in plant pathogenic fungi. Stress Biol. 2021, 1, 5. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Cui, X.; Xiao, J.; Kang, X.; Hu, J.; Huang, Z.; Li, N.; Yang, C.; Pan, Y.; Zhang, S. A novel MAP kinase-interacting protein MoSmi1 regulates development and pathogenicity in Magnaporthe oryzae. Mol Plant Pathol. 2024, 25, e13493. [Google Scholar]

- Abah, F.; Kuang, Y.; Biregeya, J.; Abubakar, Y.S.; Ye, Z.; Wang, Z. Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinases SvPmk1 and SvMps1 Are Critical for Abiotic Stress Resistance, Development and Pathogenesis of Sclerotiophoma versabilis. J fungi. 2023, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angelova, M.B.; Pashova, S.B.; Spasova, B.K.; Vassilev, S.V.; Slokoska, L.S. Oxidative stress response of filamentous fungi induced by hydrogen peroxide and paraquat. Mycoll Res. 2005, 109, 150–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chumley, F.G.; Valent, B. Genetic analysis of melanin-deficient, nonpathogenic mutants of Magnaporthe grisea. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. 1990, 3, 135–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.-H.; Liang, S.; Wei, Y.-Y.; Zhu, X.-M.; Li, L.; Liu, P.-P.; Zheng, Q.-X.; Zhou, H.-N.; Zhang, Y.; Mao, L.-J. Metabolomics analysis identifies sphingolipids as key signaling moieties in appressorium morphogenesis and function in Magnaporthe oryzae. MBio 2019, 10, 10.1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wengler, M.R.; Talbot, N.J. Mechanisms of regulated cell death during plant infection by the rice blast fungus Magnaporthe oryzae. Cell Death Differ. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Shen, N.; Zhang, Q.; Qin, M.; Cao, T.; Zhu, S.; Tang, D.; Han, L. Magnaporthe oryzae transcription factor MoBZIP3 regulates Appressorium turgor pressure formation during pathogenesis. Intern J Mol Sci. 2022, 23, 881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, L.; Cao, J.; Du, A.; An, Q.; Chen, X.; Yuan, S.; Batool, W.; Shabbir, A.; Zhang, D.; Wang, Z. eIF3k domain-containing protein regulates conidiogenesis, appressorium turgor, virulence, stress tolerance, and physiological and pathogenic development of Magnaporthe oryzae. Front Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 748120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.R.; Hamer, J.E. MAP kinase and cAMP signaling regulate infection structure formation and pathogenic growth in the rice blast fungus Magnaporthe grisea. Genes Dev. 1996, 10, 2696–2706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aron, O.; Wang, M.; Lin, L.; Batool, W.; Lin, B.; Shabbir, A.; Wang, Z.; Tang, W. MoGLN2 Is Important for Vegetative Growth, Conidiogenesis, Maintenance of Cell Wall Integrity and Pathogenesis of Magnaporthe oryzae. J Fungi. 2021, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).