1. Introduction

While the canonical TATAAA sequence is a prevalent core promoter element in eukaryotes, not all core promoters contain this sequence, leading to the identification of "TATA-less" promoters [

1]. One such regulator is the carbon-catabolite repression-negative on TATA box less (Ccr4-Not) complex. The CCR4-Not complex is a highly conserved multi-subunit protein found in eukaryotic cells, including fungi, and plays an essential role in regulating gene expression. These functions include interacting with transcription factors, initiating transcription, elongating transcription, exporting messenger RNA (mRNA), degrading mRNA, deadenylating mRNA, and repressing mRNA translation. The complex is consistently found in the nucleus and cytoplasm and is present at all stages of gene expression throughout the life cycle, indicating its importance [

2,

3,

4].

In yeast, a classic model fungus, the CCR4-Not complex is structurally composed of nine conserved subunits, including Ccr4 and associated factor

Caf genes (

Caf130,

Caf40, and

Caf1) as well as five

Not genes (

Not1,

Not2,

Not3 (

SIG1),

Not4 (

Mot2),

Not5) [

2,

4]. Through genetic analysis of yeast mutants, the CCR4 protein was identified as a positive regulator of glucose-repressible alcohol dehydrogenase (

ADH2) genes [

5], and the

CCR4-associated factor (

Caf) gene was identified as a catalytic subunit [

2,

6].

NOT1 proteins act as scaffolds for assembling the complex, providing binding sites for the NOT2-NOT3/5 subunits, CAF130, CAF40, and the catalytic module [

7]. However, the precise function of NOT3 in yeast remains unclear. In humans,

CNOT3 has been implicated in gene expression, regulation, mRNA surveillance, and export. This suggests that this gene plays a crucial role in post-transcriptional gene regulation and is essential for normal cell function and viability [

8]. In most eukaryotes, except for yeast and

Candida albicans,

NOT3 genes are orthologous to yeast

NOT3 and

NOT5. In human fungal pathogens, such as

Cryptococcus neoformans and

Candida albicans,

CaNOT5 is involved in morphogenesis, virulence, and cell wall structure [

9,

10].

Similarly, in plant pathogenic fungi, the CCR4-NOT complex has been found to play a crucial role in regulating virulence-related functions. In the case of

Fusarium oxysporum f. sp.

niveum, which causes

Fusarium wilt in watermelon, the

FoNOT2 gene plays diverse roles, including mycelial growth, conidiation, virulence, cell wall integrity, and the production of secondary metabolites [

11].

Fusarium graminearum, the pathogen responsible for

Fusarium head blight in wheat, has also been studied previously.

FgNOT3 is involved in pleiotropic defects in vegetative growth, sexual reproduction, secondary metabolite production, and virulence [

12]. However, to date, there have been no reports on the gene functional analysis of the NOT complex, including

NOT3, in

Magnaporthe oryzae, which causes rice blast disease.

Rice blast caused by

M. oryzae is one of the most destructive diseases affecting cultivated rice worldwide.

M. oryzae has been used as a model to understand fungal diseases [

13]. To infect a host cell,

M. oryzae undergoes several developmental processes, including attachment, conidial germination, appressorium formation, direct penetration using turgor pressure, and invasive growth into the rice host cell. As an initial step in invading a host plant, three-celled asexual conidia attach to the rice leaves after landing on the host surface [

14]. When conidia are attached to a leaf with mucilage, they germinate within 3–4 h and form an appressorium within 4–6 h. A specialised structure called an appressorium directly penetrates the host cell with an enormous internal turgor pressure estimated to be as high as 8.0 MPa [

15]. Several studies have reported that signalling-related pathways are involved in appressorium formation, including the cAMP-related pathway [

16], MAP kinase pathway [

17], and calcium/calmodulin-dependent signalling [

18,

19]. Genes related to signalling regulate the formation of appressoria, as well as penetration and invasive growth [

15,

20].

Invasive hyphae colonise host cells and express numerous genes associated with pathogenicity [

21]. Subsequently, conidia of

M. oryzae emerge on the infected rice cells to reinitiate the disease cycle. Conidia produced from conidiophores are controlled by several genes, including

Com1,

Con7, and

Con1 [

20,

22,

23]. Developmental processes, such as conidiation, conidial attachment, germination, appressorium formation, and pathogenicity, are regulated by genes, including transcription factors and protein complexes [

24,

25,

26,

27]. However, the pathosystem mechanisms between the host cells and

M. oryzae need to be elucidated. Understanding the genetic mechanisms underlying host infections is a priority for the development of new disease-control strategies.

In a previous study, we identified a gene, MGG_08101, which was specifically abundant during appressorium development compared to mycelial growth in

M. oryzae [

28]. The gene encoding putative

NOT3/5 was named

MoNOT3/5. In this study, we conducted a functional analysis of and

MoNOT3/5 in

M. oryzae. To analyse the function of this gene under infection-related conditions, we generated

MoNOT3/5 deletion mutants. Our data show that

MoNOT3/5 is necessary for the overall fungal development of

M.

oryzae infection, particularly for pathogenicity and thermal stress response.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Fungal Isolate and Culture Conditions

M. oryzae wild-type (WT) strain KJ201 and all the generated transformants in this study were cultivated on V8-Juice agar medium (8% Campbell’s V8-Juice, 1.5% agar, pH adjusted to 7 using 0.1 N NaOH) or oatmeal agar medium (50 g oatmeal per litre) at 25°C under constant light. To extract genomic DNA and RNA, mycelia were isolated from fungal mycelia collected from 4-day-old cultures cultivated in liquid complete medium (CM, 0.6% yeast extract, 0.6% casamino acid, and 1% sucrose) for 5 days.

To assess mycelial growth, we used modified complete agar medium (mCM), minimal agar medium (MM), carbon-starved medium based on MM (MM-C), and nitrogen-starved medium based on MM (MM-N), as previously described [

29]. Genomic DNA was isolated from mycelia collected from 4-day-old cultures grown in liquid CM.

CaCl2 (0.2 M), NaCl (0.5 M), MnCl2 (0.02 M), sodium dodecyl sulphate (SDS) (0.01%), Congo red (200 ppm), calcofluor white (200 ppm), and H2O2 (2 mM) were added to CM agar to determine their effects on fungal mycelial growth. Thermal stress response assays were performed at 25°C and 32°C on CM. The inoculum was prepared with 5-mm agar plugs from 7-day-old strains on CM, and the plugs were then transferred upside down onto each medium. Mycelial growth was measured after incubation for 9 days, and the percentage of inhibition was calculated by comparing the mycelial growth on the CM.

2.2. Computational and Phylogenetic Analyses

The MoNOT3/5 protein sequence (MGG_08101) and sequences of

NOT3 various fungi were obtained from the Comparative Fungal Genomics Platform (

http://www.cfgp.snu.ac.kr) [

30]. Homology searches for DNA and protein sequences were performed using BLAST at the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI). Sequence analysis and domain architecture of NOT3/5 were conducted using InterPro Scan, which is available at the European Bioinformatics Institute (

http://www.ebi.ac.uk/interpro/). The amino acid sequence of

NOT3 was aligned using ClustalW (

http://align.genome.jp/). Phylogenetic trees were constructed using the maximum likelihood method in the MEGA program [

31]. All sequence alignments were tested using the bootstrap method with 1,000 repetitions.

2.3. Vector Construction and Fungal Transformation

The construction of the

MoNOT3/5 gene knockout mutant was performed using double-joint polymerase chain reaction (PCR) [

32]. Fragments corresponding to 1.5 kb upstream and downstream of

MoNOT3/5 were amplified using primers

MoNOT3/5_5UF/5UR and

MoNOT3/5_DF/DR, respectively. A 1.4-kb hph cassette was amplified with primers HygB_F and HygB_R (

Table 1) from pBCATPH, which contains the hygromycin phosphotransferase gene (

hph) under the control of the

Aspergillus nidulans TrpC promoter [

33]. The

MoNOT3/5 gene disruption construct was amplified with primers nested

MoNOT3/5_5UF/3DR using the fused products as a template and was directly transformed into the protoplasts of strain WT.

Protocols for protoplast preparation and fungal transformation were adapted from a previous study [

34]. Hygromycin-resistant transformants were screened by PCR using primers

MoNOT3/5_ORF_F/R (

Table 1).

For complementation, a 4-kb fragment containing the native promoter and ORF of

MoNOT3/5 was amplified with primers

MoNOT3/5_5UF and 3DR (

Table 1) from genomic DNA of the WT. This fragment was co-transformed into protoplasts from the

MoNOT3/5 gene deletion mutant using pll99, which contains a gene that confers resistance to geneticin. Transformants were selected based on their ability to grow in the presence of geneticin (800 μg/mL).

2.4. Nucleic acid Manipulation and Southern Blot Analysis

Genomic DNA was isolated from using the NucleoSpin® Plant II Kit (MachereyNagel, Düren, Germany). The DNA concentration was estimated using a NanoDrop ND-1000 spectrophotometer (NanoDrop Technologies, Inc. Wilmington, NC, USA). Putative MoNOT3/5 gene deletion mutants were confirmed by Southern blot analysis. For Southern blotting, genomic DNA (approximately 5 μg) was digested with EcoRI and fractionated on a 0.7% agarose gel at 40 V for 4 h in 1% Tris-acetate-EDTA buffer. The fractionated DNA was transferred onto Hydond N+ nylon membranes (Amersham International, Little Chalfont, England) using 10× SSC (1× SSC comprised 0.15 M NaCl plus 0.015 M sodium citrate). The probe, designed from the 3’-flanking region, was labelled with alkaline phosphate using AlkPhos Direct Labelling Reagents (Amersham Biosciences, UK). Hybridisation, washing, and detection were performed according to the instruction manual of the Alkphos Direct Labelling and Detection System using CDP Star (Amersham Pharmacia).

Briefly, hybridisation was performed at 55°C in Gene Images AlkPhos Direct hybridisation buffer, including 0.5 M NaCl and 4% blocking reagent. After hybridisation, the membrane was washed twice in primary wash buffer at 55°C for 10 min and then washed twice in secondary wash buffer at room temperature for 5 min. Target DNA was detected using CDP star reagent (Amersham International plc, Buckinghamshire, UK) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

2.5. Conidiation, Conidial Morphology, Conidial Germination, and Appressorium Formation

To measure conidiation and conidial morphology, conidia were collected from 7-day sporulating cultures on V8-Juice agar media by gently rubbing the mycelia with sterilised distilled water, followed by filtration through Miracloth (Calbiochem, San Diego, USA). The number of conidial suspensions was counted using a haemocytometer (BRAND counting chamber, BLAUBRAND, Brand GMBH, Germany). Conidial size was measured using a microscope, and the conidia were stained with calcofluor white and KOH to observe conidial morphology.

Conidial germination and appressorium formation were measured using hydrophobic coverslips. A total of 50 μL of a conidial suspension (5 × 104 conidia/mL) was placed on a coverslip and incubated in the moist box at 25°C for 8 h and 24 h. The percentage of conidia with germ tubes and appressoria was determined by microscopic examination of at least 100 conidia per replicate. All experiments were performed in triplicate.

2.6. Plant Infection Assays

For the pathogenicity assay, conidia were harvested from 7-day-old cultures on V8 agar plates, and 10 mL of a conidial suspension (1 × 105 conidia/mL) containing 250 ppm Tween 20 was sprayed onto 4-week-old susceptible rice seedlings (Oryza sativa cv. Nakdongbyeo) at the three-to-four-leaf stage. For the detached leaf assay, 50 μL of conidial suspension (2 × 104 conidia/mL) was dropped on three points per leaf of 4-week-old rice plans. For the infiltration infection assay, 100 μL of conidial suspension (2 × 104 conidia/mL) was injected into three points per leaf of 4-week-old rice plants. All inoculated plants were kept in a dew chamber at 25°C for 24 h in the dark and then moved to a growth chamber with a photoperiod of 16 h under fluorescent lights. Disease severity was measured 5 days after inoculation.

Plant penetration assays were performed using onion epidermis and rice sheaths, as previously described [

35]. Briefly, 4-week-old rice sheaths of cv. Nakdongbyeo and conidia (1 × 10

4 conidia/mL) from 7-day-old cultures on V8-Juice agar media were used for onion epidermis and rice sheaths. The inoculated plants were maintained in a moist box at 25°C for 36 h in the dark. An infection assay using onion epidermis was performed using fresh onion epidermis. All experiments were performed in triplicate.

2.7. RNA Isolation, Quantitative Real-Time (qRT)-PCR, and Gene Expression Analysis

Total RNA was prepared using the Easy-Spin Total RNA Extraction Kit (iNtRON Biotechnology, Sungnam, Korea) following the manufacturer’s instructions. Total RNA was extracted from the fungus at several developmental stages under stress conditions and used as a template for reverse transcription (RT)-PCR. Total RNA was extracted from mycelia in liquid mCM for expression analysis of the COS1, Com1, Con7, and MoHox2 genes.

To obtain samples during conidiogenesis, WT and gene-deletion mutants were inoculated into liquid mCM and incubated at 25°C on a 120 rpm orbital shaker for 3 days. The resulting mycelia were fragmented using a spatula and filtered through a single-layer cheesecloth. Mycelia were collected using one layer of Miracloth (Calbiochem, California, USA) in 2 mL of sterilised distilled water. Then, 400 μL of the mycelial suspension was spread onto individual 0.45-μm pore cellulose nitrate membrane filters (Whatman, Maidstone, England) placed on V8-Juice agar plates using a loop. The plates were dried and incubated at 25°C with constant light. After 12 h of inoculation, whole mycelia on cellulose nitrate membrane filters were collected using a disposable scraper (iNtRON Biotechnology, Seoul, Korea) [

27].

qRT-PCR reactions were performed using a 96-well reaction plate and a CFX96 Touch™ Real-Time PCR Detection System (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA, USA). Each well contained 5 μL of SYBR Green I Master mix (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA, USA), 2 μL of cDNA (12.5 ng), and 15 pmol of each primer. The thermal cycling conditions were 10 min at 94°C, followed by 40 cycles of 15 s at 94°C and 1 min at 60°C. All amplification curves were analysed with a normalised reporter threshold of 17 to obtain the threshold cycle (Ct) values.

The primer sequences used for each gene are listed in

Table 1. To compare the relative abundance of the target gene transcripts, the average Ct value was normalised to that of -tubulin (MGG00604) for each of the treated samples as 2

-Ct, where Ct = (Ct,

target gene - Ct,

-tubulin). Fold changes during fungal development and infectious growth in liquid CM were calculated as 2

-Ct, where Ct = (Ct,

target gene - Ct,

-tubulin)

test condition - (Ct,

WT - Ct,

-tubulin)

CM [

10]. qRT-PCR was performed using three independent tissue pools with two sets of experimental replicates.

4. Discussion

CCR4-NOT complexes are essential proteins that regulate and coordinate diverse biological processes. While numerous new studies have been published on the functional analyses of CCR4-NOT complexes in yeast, humans, human pathogenic fungi, and some phytopathogenic fungi, the characterisation of CCR4-NOT complexes in phytopathogenic fungi is still required [

2,

6]. In this study, we characterised the crucial regulatory roles of

MoNOT3/5 in the developmental stages of

M. oryzae. The absence of

MoNOT3/5 gene led to multiple defects in mycelial growth, conidiation, conidial morphology, germination, appressorium formation, cell wall stress response, and virulence.

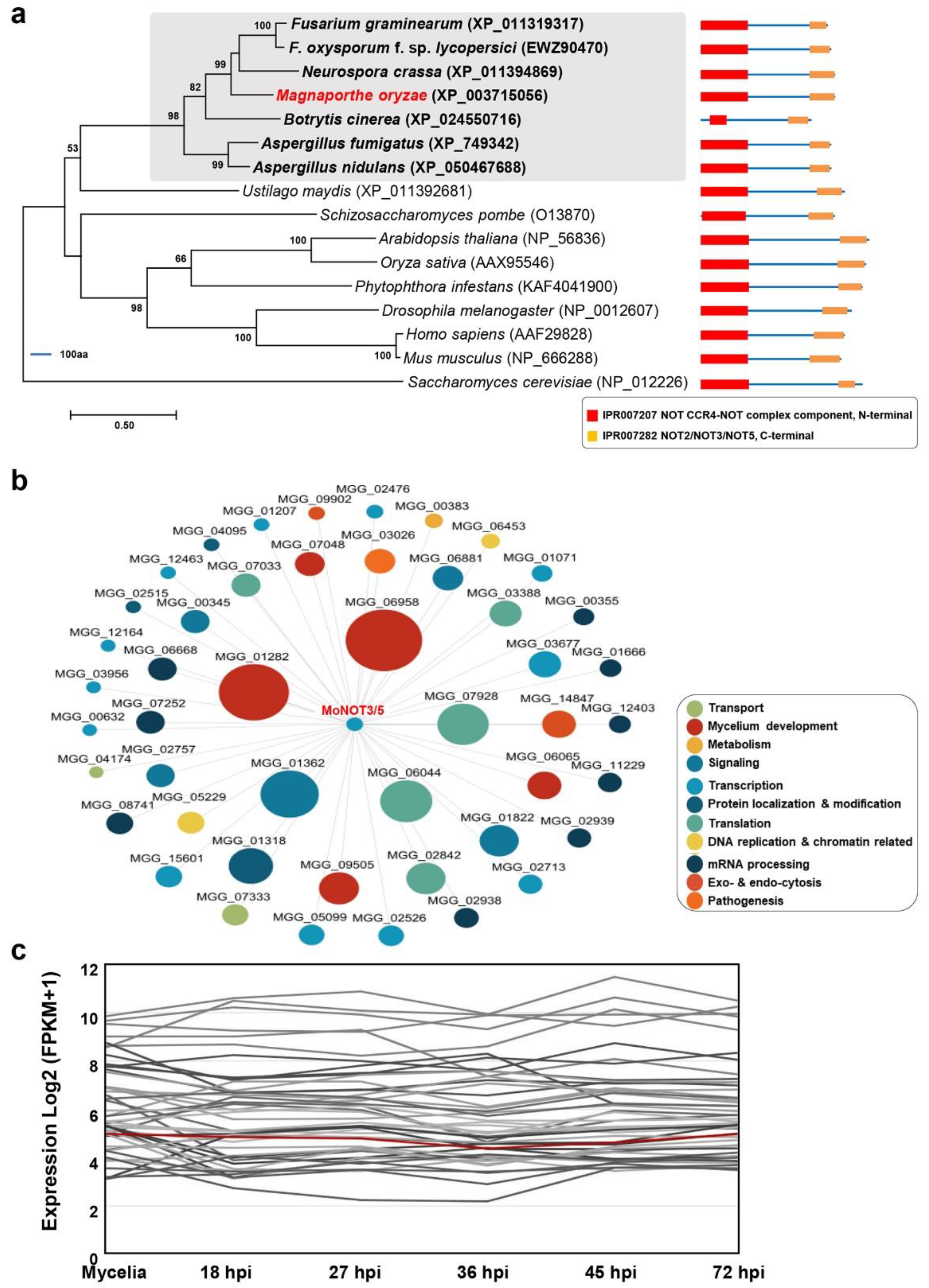

The CCR4-NOT complexes are well conserved in

M. oryzae (

Figure 1a). The

MoNOT3/5 gene is homologous to the yeast genes

ScNOT3 and

ScNOT5, human gene

CNOT3,

C. albicans gene

CaNOT5, and

F. graminearum gene

FgNOT3 [

12]. In

C. albicans,

CaNOT5 is involved in spore attachment and pathogenicity [

9,

10]. In

F. graminearum,

FgNOT3 is involved in mycelial growth, conidiation, sexual reproduction, and the production of secondary metabolites [

12]. In the present study, we discovered that

MoNOT3/5 is involved in infection-related cell development, including conidiation, conidial germination, appressorium formation, invasive growth, spore germination, and appressorium formation. These results indicate that

MoNOT3/5 may be involved in all stages of fungal development.

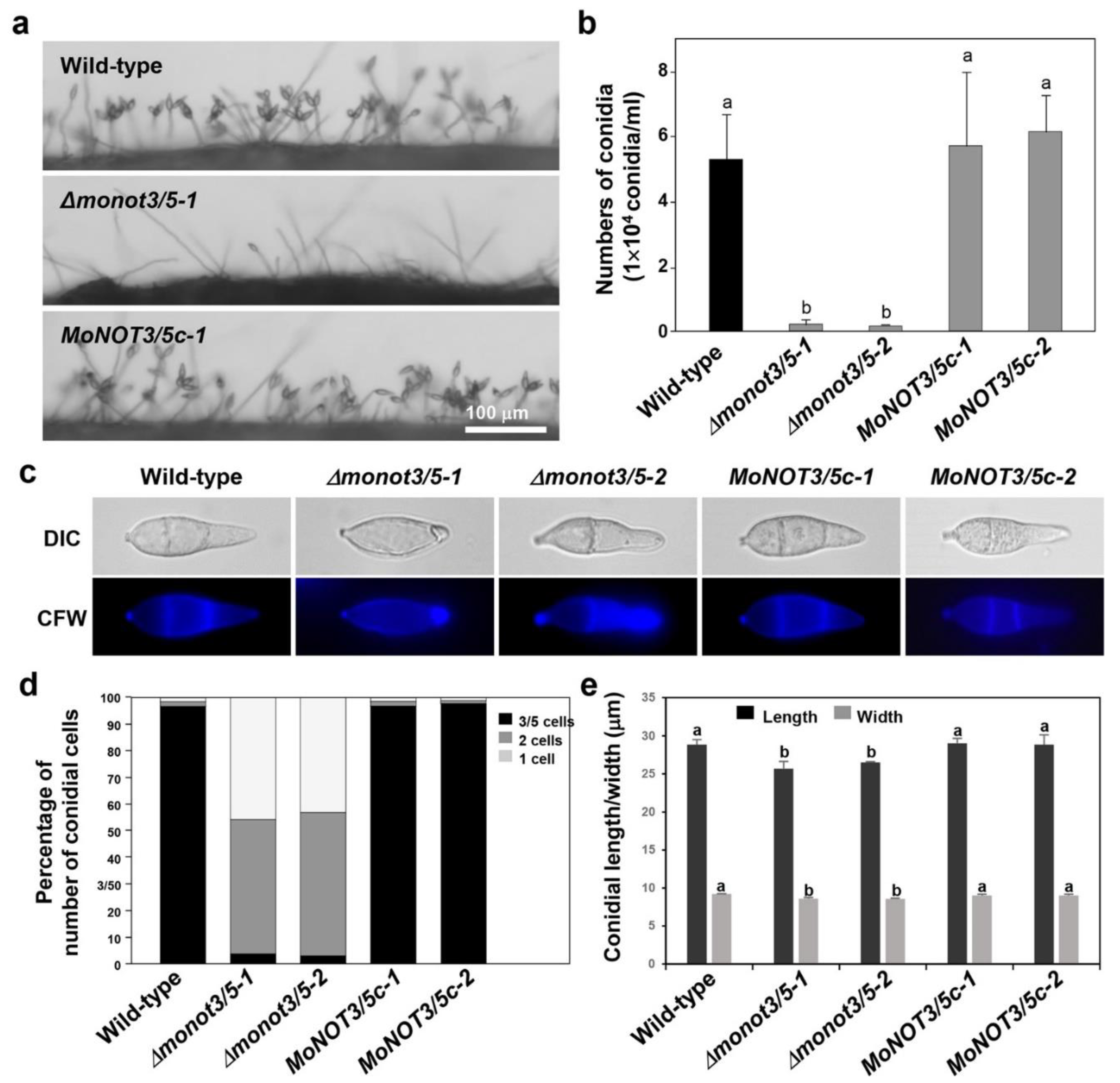

Interestingly, we found that

MoNOT3/5 contributes to conidiation-related morphogenesis, including the development of conidiophore stalks, conidial morphology, and conidial production. Except for germination, these phenotypes were similar to those observed in other fungi [

12]. The deletion of

FgNOT3 results in defective conidial morphology and germination [

12]. However, the germination of

ΔFgnot3 fully recovered over time, whereas that of

Δmonot3/5 did not, even with additional time. These differences may indicate species divergence among filamentous fungi. Because delayed mycelial growth, germination, and abnormal septation are related to cell cycle progression, the observed phenotypes in the mutants suggest that

MoNOT3/5 is involved in regulating the cell cycle.

Previous studies have reported that the mutants of

C. albicans and

F. graminearum were deficient in virulence. The deletion of

CaNOT5 does not induce a switch to a hyphal transition related to virulence [

9]. In

F. graminearum, deletion of

FoNOT3 resulted in an increase in secondary metabolites but did not lead to disease development [

11]. The mutants were unable to form mats or aspersoria-like structures to penetrate the host cell wall. Unlike

F. graminearum, in this study, we found that

MoNOT3/5 was associated with appressorium formation and invasive hyphae, demonstrating its crucial role in penetration. This is the first report indicating that

MoNOT3/5 is involved in the formation of the appressorium and invasive hyphae for penetration.

In yeast, double knockout mutants of

NOT1,

NOT2, and

NOT3/NOT5 are sensitive to heat stress [

36]. In

F. graminearum,

NOT module mutants exhibit sensitivity to heat stress [

12].

CaNOT5 in

C. albicans was sensitive to calcofluor white, whereas

FoNOT2 was sensitive to calcofluor white, Congo red, and oxidative stress.

Δmonot3/5 mutants were sensitive to heat stress, SDS, and Congo red. However, there was no difference in the other cell wall stress conditions. These differences may indicate species divergence among filamentous fungi. Other modules appear to play a more significant role in cell wall stress conditions in fungi than

Δmonot3/5.

To understand these phenotypes, we identified the proteins that interact with

MoNOT3/5. These results suggest that

MoNOT3/5 interacts with ubiquitin, which plays an important role in various cellular processes and host–pathogen interactions [

37]. The levels of polyubiquitin transcripts increased in the mutant. Mono-ubiquitination may negatively affect polyubiquitin levels, and our transcript analyses demonstrated interactions among these proteins. In

M. oryzae,

Ssb1,

Ssz,

Zuo1, and

Mkk1, which are associated with heat shock proteins, are involved in growth, pathogenicity, cell wall integrity, and conidiation [

38]. The loss of

Ssb1 resulted in protein misfolding. When comparing the phenotype of

Δmonot3/5 with

ΔMoSsb1, it is necessary to confirm the interactions with heat shock proteins. Monosodium triphosphate may affect the expression of heat shock proteins, which are crucial regulators.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.K., K.-T.K. and S.-Y.P.; methodology, Y.K., Y.L. and M.-H.J.; validation, Y.K., M.J., S. A. and S.-Y.P.; formal analysis, Y.K., Y.L. and M.-H.J.; investigation, Y.K., M.J., S. A., Y.L., E.D.C., M.-H.J. and K.-T.K.; resources, S.-Y.P.; data curation, Y.K. and S.-Y.P.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.K. and S.-Y.P.; writing—review and editing, Y.K. and S.-Y.P.; visualization, Y.K., K.-T.K. and S.-Y.P.; supervision, S.-Y.P.; project administration, S.-Y.P.; funding acquisition, S.-Y.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Figure 1.

Phylogenetic trees, putative protein–protein interaction (PPI) network, and the expression patterns of MoNOT3/5. (a) Phylogenetic analysis of NOT3/5 from Magnaporthe oryzae with eukaryotes. A maximum likelihood tree was constructed based on the amino acid sequence using MEGA X. All sequence alignments were tested with a bootstrap method using 1,000 repetitions. The domain architecture of NOT3/5s was determined by InterProScan. The scale bar shows the number of amino acid differences per site. Subclades containing MoNOT3/5 are shaded, in which MoNOT3/5 and characterised genes from other fungi are shown in bold in red or black, respectively. The text with numbers in parentheses represents the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) accession numbers of the protein sequences. (b) The PPI network of MoNOT3/5. Only the first neighbours of MoNOT3/5 are shown. The circle size of the nodes represents the number of edges (interactions) connected to each node. The putative function of each node represented by the GO term is colour coded. (c) The expression patterns of MoNOT3/5 and its PPI neighbours. The expression patterns from mycelia to the infection stages of MoNOT3/5 (red line) and its 47 neighbours are shown.

Figure 1.

Phylogenetic trees, putative protein–protein interaction (PPI) network, and the expression patterns of MoNOT3/5. (a) Phylogenetic analysis of NOT3/5 from Magnaporthe oryzae with eukaryotes. A maximum likelihood tree was constructed based on the amino acid sequence using MEGA X. All sequence alignments were tested with a bootstrap method using 1,000 repetitions. The domain architecture of NOT3/5s was determined by InterProScan. The scale bar shows the number of amino acid differences per site. Subclades containing MoNOT3/5 are shaded, in which MoNOT3/5 and characterised genes from other fungi are shown in bold in red or black, respectively. The text with numbers in parentheses represents the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) accession numbers of the protein sequences. (b) The PPI network of MoNOT3/5. Only the first neighbours of MoNOT3/5 are shown. The circle size of the nodes represents the number of edges (interactions) connected to each node. The putative function of each node represented by the GO term is colour coded. (c) The expression patterns of MoNOT3/5 and its PPI neighbours. The expression patterns from mycelia to the infection stages of MoNOT3/5 (red line) and its 47 neighbours are shown.

Figure 2.

Generation of gene deletion mutants for the

MoNOT3/5 gene. (a) The

Δmonot3/5 knockout fragment was constructed by PCR amplification. The 1.5 kb upstream and downstream flanking sequences were amplified with primers

MoNOT3/5_UF/UR and

MoNOT3/5_DF/DR, respectively, and ligated with the hph gene cassette. (b) Southern blot analysis of

EcoRI-digested genomic DNA of the wild-type (WT) and the

Δmonot3/5 mutants,

Δmonot3/5-1 and

Δmonot3/5-2. The blot was hybridized with the probe shown in

Figure 2a. (c) Expression analysis of

ΜοΝOΤ3/5 in the WT strain,

Δmonat3/5 mutants, and the complemented transformants, MoNOT3/5c-1 and MoNOT3/5c-2. Primers, MoNOT3/5c_qRT_F/R (

Table 1), were used to amplify the

Δmonot3/5 transcript using RT-PCR.

Figure 2.

Generation of gene deletion mutants for the

MoNOT3/5 gene. (a) The

Δmonot3/5 knockout fragment was constructed by PCR amplification. The 1.5 kb upstream and downstream flanking sequences were amplified with primers

MoNOT3/5_UF/UR and

MoNOT3/5_DF/DR, respectively, and ligated with the hph gene cassette. (b) Southern blot analysis of

EcoRI-digested genomic DNA of the wild-type (WT) and the

Δmonot3/5 mutants,

Δmonot3/5-1 and

Δmonot3/5-2. The blot was hybridized with the probe shown in

Figure 2a. (c) Expression analysis of

ΜοΝOΤ3/5 in the WT strain,

Δmonat3/5 mutants, and the complemented transformants, MoNOT3/5c-1 and MoNOT3/5c-2. Primers, MoNOT3/5c_qRT_F/R (

Table 1), were used to amplify the

Δmonot3/5 transcript using RT-PCR.

Figure 3.

Hyphal growth of M. oryzae WT, Δmonot3/5, and MoNOT3/5c on various media. (a) Hyphal growth of M. oryzae was measured on complete medium (CM), minimal medium (MM), carbon-starved medium based on MM (MM-C), and nitrogen-starved medium based on MM (MM-C). (b) Mycelial growth (mm) was measured at 9 days post-inoculation on the different types of media. Significance was determined by Tukey’s test (P = 0.01).

Figure 3.

Hyphal growth of M. oryzae WT, Δmonot3/5, and MoNOT3/5c on various media. (a) Hyphal growth of M. oryzae was measured on complete medium (CM), minimal medium (MM), carbon-starved medium based on MM (MM-C), and nitrogen-starved medium based on MM (MM-C). (b) Mycelial growth (mm) was measured at 9 days post-inoculation on the different types of media. Significance was determined by Tukey’s test (P = 0.01).

Figure 4.

Effect of MoNOT3/5 disruption on conidiation, production of conidia, and conidial morphology of M. oryzae. (a) Development of conidiophores and conidia was visualised in M. oryzae WT, Δmonat3/5, and MoNOT3/5c strains grown on oatmeal agar media. Conidiogenesis on conidiophores was observed under a microscope. Scale bar, 100 μm. (b) Production of conidia numbers in M. oryzae WT, Δmonat3/5, and MoNOT3/5c strains. Conidia of the WT, deletion mutants, and complemented strains were collected from V8 agar after incubation for 7 days. (c) Conidial shape and septum formation were analysed in M. oryzae WT, Δmonat3/5, and MoNOT3/5c strains. Conidia were stained by calcofluor white with KOH. (d) Distribution of conidia cell numbers in the control and Δmonat3/5 mutant strains. Conidia (>100) of each strain were counted by microscopic observation. (c) Conidial size of the WT, Δmonat3/5, and MoNOT3/5c strains. Values are the means±SD from >100 conidia of each strain, which were measured using the Axiovision image analyser. Tukey’s test was used to determine significance at the 95% probability level. The same letters show no significant differences.

Figure 4.

Effect of MoNOT3/5 disruption on conidiation, production of conidia, and conidial morphology of M. oryzae. (a) Development of conidiophores and conidia was visualised in M. oryzae WT, Δmonat3/5, and MoNOT3/5c strains grown on oatmeal agar media. Conidiogenesis on conidiophores was observed under a microscope. Scale bar, 100 μm. (b) Production of conidia numbers in M. oryzae WT, Δmonat3/5, and MoNOT3/5c strains. Conidia of the WT, deletion mutants, and complemented strains were collected from V8 agar after incubation for 7 days. (c) Conidial shape and septum formation were analysed in M. oryzae WT, Δmonat3/5, and MoNOT3/5c strains. Conidia were stained by calcofluor white with KOH. (d) Distribution of conidia cell numbers in the control and Δmonat3/5 mutant strains. Conidia (>100) of each strain were counted by microscopic observation. (c) Conidial size of the WT, Δmonat3/5, and MoNOT3/5c strains. Values are the means±SD from >100 conidia of each strain, which were measured using the Axiovision image analyser. Tukey’s test was used to determine significance at the 95% probability level. The same letters show no significant differences.

Figure 5.

Effect of MoNOT3/5 deletion on conidial germination and appressorium formation. (a) Microscopic observation of appressorium development on germ tubes. Appressorium formation was examined at 8 and 24 h after incubation of the conidial suspension on hydrophobic cover slips. Black arrowheads in Δmonot3/5 indicate the occurrence of swellings and hooks in a germ tube. Percentage of conidial germination (b) and appressorium formation (c) on a hydrophobic coverslip was measured at 8 and 24 h after incubation of the conidial suspension under a light microscope using conidia harvested from 6-day-old V8-Juice agar medium. Tukey’s test was used to determine significance at the 95% probability level. The same letters show no significant differences.

Figure 5.

Effect of MoNOT3/5 deletion on conidial germination and appressorium formation. (a) Microscopic observation of appressorium development on germ tubes. Appressorium formation was examined at 8 and 24 h after incubation of the conidial suspension on hydrophobic cover slips. Black arrowheads in Δmonot3/5 indicate the occurrence of swellings and hooks in a germ tube. Percentage of conidial germination (b) and appressorium formation (c) on a hydrophobic coverslip was measured at 8 and 24 h after incubation of the conidial suspension under a light microscope using conidia harvested from 6-day-old V8-Juice agar medium. Tukey’s test was used to determine significance at the 95% probability level. The same letters show no significant differences.

Figure 6.

Pathogenicity of Δmonot3/5. (a) Pathogenicity assay results. Spray inoculation (left). Conidial suspensions (1 × 105/mL) were sprayed onto 4-week-old rice seedlings, and lesions were observed at 5 days post-inoculation. Detached leaf inoculation (middle). Conidial suspensions (2 × 104/mL) were dropped onto 4-week-old rice seedlings. Infiltration inoculation (right). Conidial suspensions (2 × 104/mL) were injected onto 4-week-old rice seedlings. (b) Onion epidermal cell infection 24 and 48 h after inoculation. (c) Rice sheath infection 48 h after inoculation. The growth of invasive hyphae was observed under a microscope at 48 h post-inoculation. Arrows indicate appressoria.

Figure 6.

Pathogenicity of Δmonot3/5. (a) Pathogenicity assay results. Spray inoculation (left). Conidial suspensions (1 × 105/mL) were sprayed onto 4-week-old rice seedlings, and lesions were observed at 5 days post-inoculation. Detached leaf inoculation (middle). Conidial suspensions (2 × 104/mL) were dropped onto 4-week-old rice seedlings. Infiltration inoculation (right). Conidial suspensions (2 × 104/mL) were injected onto 4-week-old rice seedlings. (b) Onion epidermal cell infection 24 and 48 h after inoculation. (c) Rice sheath infection 48 h after inoculation. The growth of invasive hyphae was observed under a microscope at 48 h post-inoculation. Arrows indicate appressoria.

Figure 7.

Effect of stress conditions on growth rates of Δmonot3/5. The WT, Δmonot3/5 (Δmonot3/5-1 and Δmonot3/5-2), and complemented (MoNOT3/5c-1 and MoNOT3/5c-2) strains were grown for 9 days on CM and CM containing CaCl2 (0.2 M), NaCl (0.5 M), MnCl2 (0.02 M), sodium dodecyl sulphate (SDS) (0.01%), Congo red (200 ppm), calcofluor white (CFW) (200 ppm), and H2O2 (2 mM) at a temperature of 32°C. The 5 mm-diameter mycelial blocks were transferred onto the media and incubated for 9 days at 25°C.

Figure 7.

Effect of stress conditions on growth rates of Δmonot3/5. The WT, Δmonot3/5 (Δmonot3/5-1 and Δmonot3/5-2), and complemented (MoNOT3/5c-1 and MoNOT3/5c-2) strains were grown for 9 days on CM and CM containing CaCl2 (0.2 M), NaCl (0.5 M), MnCl2 (0.02 M), sodium dodecyl sulphate (SDS) (0.01%), Congo red (200 ppm), calcofluor white (CFW) (200 ppm), and H2O2 (2 mM) at a temperature of 32°C. The 5 mm-diameter mycelial blocks were transferred onto the media and incubated for 9 days at 25°C.

Figure 8.

Expression of the WT and Δmonot3/5 in M. oryzae. (a) Relative expression of conidiation-related genes during conidiation in the Δmonot3/5. (b) Relative expression of ubiquitin-related genes during mycelial growth in the Δmonot3/5. Transcript expression was quantified by qRT-PCR analysis, and values were normalized to the expression of β-tubulin. Relative expression levels, presented as fold changes (2-ΔΔct), were calculated by comparison with the WT strain.

Figure 8.

Expression of the WT and Δmonot3/5 in M. oryzae. (a) Relative expression of conidiation-related genes during conidiation in the Δmonot3/5. (b) Relative expression of ubiquitin-related genes during mycelial growth in the Δmonot3/5. Transcript expression was quantified by qRT-PCR analysis, and values were normalized to the expression of β-tubulin. Relative expression levels, presented as fold changes (2-ΔΔct), were calculated by comparison with the WT strain.

Table 1.

Primers used in this study.

Table 1.

Primers used in this study.

| Target |

Name |

Sequence (5′-3′) |

| Knockout |

MoNOT3/5_5UF |

ATATACAGGAGGCGGGGTCAGAGT |

| construct |

MoNOT3/5_5UR |

CCTCCACTAGCTCCAGCCAAGCCGGCTAGTTGTTGTTTCGGATGTCT |

| |

MoNOT3/5_3DF |

GTTGGTGTCGATGTCAGCTCCGGAGGAGTGAATACGGCCAATAGC |

| |

MoNOT3/5_3DR |

GCACAGAGCCTAACATCAAACCCC |

| |

MoNOT3/5_5UF_nested |

GACACCATGAAACCACGCACTCTA |

| |

MoNOT3/5_3DR_nested |

GGACCAACAAGCTCCTCTCA |

| hph gene |

HygB_F |

TCAGCTTCGATGTAGGAGGG |

| |

HygB_R |

TTCTACACAGCCATCGGTCC |

| Screening of |

MoNOT3/5_ORF_F |

TACATACGCCACTACCAACCATTA |

| transformant |

MoNOT3/5_ORF_R |

GATGCTGGAAGGTGGTAGATAGAT |

| qRT-PCR |

Mo β-tubulin_F |

ACAACTTCGTCTTCGGTCAG |

| |

Mo β-tubulin_R |

GTGATCTGGAAACCCTGGAG |

| |

MoNOT3/5_qRT_F |

CAAATGGAGAGGTTCAAAGCG |

| |

MoNOT3/5_qRT_R |

TGTCGATCATGTTCCCAAGG |

| |

COS1_qRT_F |

TGCACCACGATCCCAGAGA |

| |

COS1_qRT_R |

GCGATGTTGTGCCGTTGTTCC |

| |

COM1_qRT_F |

GCCAGAGGTCCGCTATCAAA |

| |

COM1_qRT_R |

CGGGATCTCGTCACTGGATT |

| |

CON7_qRT_F |

TAAGGAGATCCGCAAAGAGT |

| |

CON7_qRT_R |

TAGCGTTGTAGTCGGGGAGT |

| |

HOX2_qRT_F |

TGGGGTTCTGCAGCCATGTT |

| |

HOX2_qRT_R |

GTCCCGTGGTGTTACGTTCTGG |

| |

Polyubiqutin_qRT-F |

CAACGCCTTATTTTCGCTGG |

| |

Polyubiqutin_qRT-R |

TCTTGCCCGTCAAAGTCTTG |

| |

Ubiqutin_qRT-F |

GCAAGTTCAACTGCGACAAG |

| |

Ubiqutin_qRT-R |

TCCACACTTTCTCTTCCTGC |

| |

Ubiqutin40_qRT-F |

AGTTGGCTGTGCTCAAGTAC |

| |

Ubiqutin40_qRT-R |

GTAGGTCAGGTGGCAACG |

| |

Skp1-qRT-F |

TGGGATCAGAAGTTCATGCAG |

| |

Skp1-qRT-R |

ATATCAAGGTAGTTGCTCGCC |

Table 2.

Hyphal growth of M. oryzae strains under diverse stress conditions.

Table 2.

Hyphal growth of M. oryzae strains under diverse stress conditions.

| Strain |

Hyphal growtha (mm) |

| CM |

CaCl2

(0.2 M) |

NaCl

(0.5 M) |

MnCl2

(0.02 M) |

SDS

(0.01%) |

Congo red

(200 ppm) |

CFW

(2 mM) |

H2O2

(2 mM) |

32°C |

| Wild-type |

69.3±0.4ab

|

50.9±1.9a |

44.4±1.7a |

53.0±1.7a |

30.6±0.3a |

45.4±0.8a |

68.3±0.2a |

58.9±1.5a |

65.3±0.2a |

| Δmonot3/5-1 |

34.3±0.3b |

26.0±0.4b |

22.2±0.5b |

27.7±0.8b |

11.3±0.6b |

12.2±0.2b |

33.2±0.4b |

29.8±1.0b |

17.4±0.4b |

| Δmonot3/5-2 |

32.7±0.6b |

25.9±0.4b |

23.8±0.8b |

28.1±0.2b |

14.0±0.5b |

11.4±0.6b |

33.7±0.5b |

30.1±0.1b |

17.3±0.3b |

| MoNOT3c-1 |

68.3±0.6a |

49.9±1.3a |

44.2±1.3a |

52.8±1.1a |

32.1±0.6a |

42.3±1.9a |

67.2±0.4a |

59.1±0.2a |

65.2±0.3a |

| MoNOT3c-2 |

67.7±0.2a |

46.7±0.8a |

43.0±1.4a |

50.8±1.1a |

30.0±1.0a |

45.7±1.2a |

68.0±0.5a |

58.9±1.4a |

65.3±0.3a |