1. Introduction

Access to affordable, reliable, sustainable, and modern energy (SDG 7) (United Nations, 2015) is being advocated globally because of its important contributions to household, community, and national lives. Using the popular definition of sustainable development from the Brundtland Report (United Nations, 1987) as a basis, sustainable energy means achieving energy access that meets the requirements of the present generation without jeopardizing the access of future generations to the same resources. There is an overwhelming requirement to invest in options that will promote this agenda and two important decisions are required. First, the performance of the currently installed capacities, which are mostly conventional, should be improved to make them more sustainable. Second, new sustainable investments are expected to augment the current deficit. Different technologies would dictate the attainment of this goal in the energy system, given their respective benefits and disadvantages. While ensuring that people have access to electricity is a necessary first step, a number of incidents show that power systems can be made much more resilient (Mazur et al., 2019). Changes in energy and environmental policies, new power plant types, and other major changes can cause disruptions during the transition to decarbonized energy systems, not to mention threats from nature and man-made actions and inaction. Energy planning is imperative in anticipation of disruptive situations to ensure the maintenance of optimal energy system performance (Ahmadi, Saboohi, Tsatsaronis, et al., 2021) because power outages have severe adverse effects on the healthcare sector, economy, and education, as well as sustainable development as a whole (Moslehi & Reddy, 2018). Thus, considering the practicalities of complex systems and a dedication to fulfilling sustainability obligations, holistic approach (Adamo et al., 2020) and evaluation framework that integrates these factors is highly appropriate for this situation (Gaudreau & Gibson, 2010). Research shows that simultaneous attention to sustainability and resilience issues is significant in promoting supply chain sustainability and competitiveness (Salehi et al., 2022).

Sustainability aims to maintain environmentally, economically, and socially desirable human-environment interactions (Labuschagne et al., 2005; Sharifi & Yamagata, 2015). The incorporation of numerous sustainability criteria into the evaluation procedure is critical and a growing priority for low-carbon energy investment decisions. Its assessment is viewed as a vital instrument to aid the shift towards sustainability. This approach helps to identify and implement sustainable alternatives for the future given their unique performance under different criteria (Atilgan & Azapagic, 2016; Ren, 2018). It is crucial to assess the sustainability of energy systems and technologies from a wider perspective and throughout the system lifecycle. Such a holistic approach will require an understanding of other factors such as political, technological and institutional factors (Verma et al., 2023) as decision-making transverse from the local, national and global levels. The criteria for measuring sustainability have unique definitions depending on the context of usage. When crafting climate and energy policies, it must be clear that the best path depends upon the exact goal being addressed (Brecha et al., 2011). For example, renewable energy technologies were investigated using several critical sustainability indicators (Evans et al., 2009). Some frameworks have been developed for assessing sustainability (Akber et al., 2017; Haddad et al., 2021; B. Wang et al., 2019). Frameworks for sustainability assessment offer interpretations through practical applications such as utility analysis, cost—benefit analysis, and comparative value analysis, risk assessment, and multi-criteria analysis (Abdul Murad et al., 2019).

Resilience is used in a variety of disciplines to describe the ability to withstand and adjust to disruptions while remaining functional (Brien & Hope, 2010). It offers explanations for the performance of any system under dynamic environments and across multiple periods. It takes into account behaviours under changing conditions and complex interactions between the physical, informational, and human domains, thereby supplementing conventional static system performance measures (such as sustainability) (Roege et al., 2014). Energy is one of the most important fields of application for resilience policies, particularly in regard to electricity (Gatto & Drago, 2020b). Resilience is currently receiving increasing attention as additional requirement for energy transition (B.-J. Jesse et al., 2024). Energy resilience (ER) is widely recognised as the adaptability of an energy system to respond to unforeseen shocks (Molyneaux et al., 2016). In theory, ER can be perceived as energy system’s capacity to cope with changing conditions or disturbances (B. Jesse et al., 2019). An energy system, for example, needs to continue providing electricity even though it transforms into a renewable sources (Schilling et al., 2018). Loss of resilience can lead to a decline in the ability of energy systems to provide services, as well as sudden shifts into fundamentally new states and structures that can affect individuals, cultures, ecosystems, or knowledge systems (Afgan & Veziroglu, 2012). Past studies have identified approaches for explaining resilience with respect to energy systems, including engineering resilience which analyses critical infrastructure such as the electricity grid to determine its ability to recover from tipping points (Gatto & Drago, 2020a; B. Jesse et al., 2019; Sharifi & Yamagata, 2015). Ecological resilience pertains to the capacity of a given system to endure disruptions and sustain its fundamental operations in the face of unpredictability. This system is capable of re-entering numerous equilibrium states (Gatto & Drago, 2020a; Sharifi & Yamagata, 2015). Socio-ecological resilience is a soft approach that recognizes system dynamics, uncertainties, and natural disaster unpredictability. According to the resilience approach, which is dynamic and system-oriented, resilient social–ecological systems have adaptive capacity (Brien & Hope, 2010).

With respect to the relationship between the two concepts, they have been considered as synonyms, or subset of each other or separate yet complimentary objectives (Roostaie et al., 2019). Both the sustainability and resilience criteria have been conceived for broad application to evaluations of situations, options and undertakings of various kinds, scales and locations (i.e., Grafakos, 2016). Ensuring a high level of system resilience during a sustainability transition process minimizes the risk of system-level collapse (Schilling et al., 2018). Resilience and sustainability metrics often have overlapping goals;, therefore, both can be included in composite indices (Yazdanie, 2023), and can be applied to changes in system parameters (Afgan & Veziroglu, 2012), shortages and unequal distributions of energy resources (Ala et al., 2023), climate change (Amin, Hasnat, et al., 2023) energy management systems, among others (Dashtpeyma & Ghodsi, 2022). Since the resilience of any infrastructure system is about sustaining capacity, especially during extreme events, it ought to be reflected in its analysis, measurement, tracking, enhancement, and planning (Mujjuni et al., 2021). Energy planners can use their criteria to evaluate a wide range of scenarios, choices, and projects of different sizes, scopes, and locations (i.e., Grafakos, 2016). Resilience criteria can enhance sustainability-based evaluation criteria by clarifying the necessary attributes for maintaining socioecological integrity (Gaudreau & Gibson, 2010). However, uniting the concepts may be challenging when goals and strategies for achieving goals are different and when the equilibrium of the system is distinct (Roostaie et al., 2019). Thus, case and context specifics are essential in every incorporation of the two objectives. To develop evaluation criteria for a specific case and context, it is necessary to combine general criteria with a focus on the specific factors relevant to the case and context, especially those that showcase aspirations and constraints (Gaudreau & Gibson, 2010).

Sustainability and resilience have been well discussed conceptually. While energy sustainability has gained wider recognition globally, energy resilience is trailing with some momentum. To date, many energy decision studies have addressed the duo individually. For instance, Lassio et al. (2021), Liu (2014) and Martín-Gamboa et al. (2017) address sustainability whereas Gasser et al. (2021), B. Jesse et al. (2019) and Mola et al. (2018) are on resilience. The combination of the two for energy planning is still in its infancy. The only study known to authors at the time of implementation of this research (Mazur et al., 2019) was an in-depth review to develop general resilience framework for energy systems to promote sustainability goals. This study reiterates the likely synergy between the two but failed to address how they should be integrated in reality. Additionally, single-objective studies have limited application to increasing complexities of urban infrastructure systems on the one hand, and more severe and more frequent natural disasters due to global climate change on the other hand, which demands holistic considerations (Moslehi & Reddy, 2019). It is not enough to achieve sustainable access when interruptions due to low resilience persist in the system. This has forced researchers to consider resilience explicitly along with assessing the sustainability of critical infrastructures (Moslehi & Reddy, 2019). Therefore, this study use existing frameworks to present perspectives to address this gap. On the basis of current trends and practices, this review promotes an understanding of the elements or parameters or factors captured as “decision objective, context, and implementation” to enhance the integration of sustainability and resilience for energy decisions. The scope of this study is electrical energy, since electricity plays a critical role in connecting different segments of the energy sector and supporting the fundamental operations of residential, commercial, and industrial sectors (IEA, 2020) and for sustainable development (Atilgan & Azapagic, 2016). As a result, in this study, ’energy’ is used synonymously with electrical energy. Sustainability in this study takes a cue from SDG 7, whereas energy resilience is used to explain a system’s ability to withstand and recover quickly from any unanticipated shocks (United Nations, 2023). The achievement of these two objectives promotes SDG 7 without disruption in the system. A systematic approach is essential for facilitating effective decision-making and policy formulation to achieve the targets outlined in SDG 7 and, ultimately, to foster a sustainable energy transition (Dantas & Soares, 2022).

The following sections of this article include situating the agenda of this study; the methodology used for this review; trends and practices that can improve the integration of the objectives; discussions of the findings; and conclusions with future research directions.

2. Overview of Existing Study and Situating the Agenda of this Study

The body of knowledge contributes to the explanation of relevant concepts, generating theories, approaches, decision frameworks, and analyses of the sustainability and resilience of the energy system. The review by Liu (2014) aimed to develop methods for selecting, quantifying, evaluating, and weighting indicators, as well as general sustainability indicators and aggregation for renewable energy systems. Martín-Gamboa et al. (2017) performed a systematic review of commonly used data sources, criteria, and tools that are useful for integrating data envelopment analysis and life-cycle approaches to evaluate the sustainability of energy systems. To present the study’s results, both descriptive and in-depth analyses of the identified articles were used. Other studies include Lassio et al. (2021), who focused on incorporating life cycle-based sustainability into the decision-making process concerning electricity generation by conducting frequency analysis of indicators. Dantas and Soares (2022) identified challenges, methodological approaches, and sustainability indicators used to perform life cycle sustainability assessment via bibliometric, publication trends, and comparative analyses. Zhang et al. (2021) focused on highlighting the limitations of the index system and assessment method for hydropower sustainability assessment, using historical studies as a means of improvement. On the other hand, Mola et al. (2018) explored the resilience of electrical infrastructural systems, whereas a review by Jesse et al. (2019) investigated the application of resilience to energy systems. Gasser et al. (2021) presented an overview of definitions of resilience across various scientific disciplines, and performed in-depth quantification and analysis of resilience assessment for energy systems. Ahmadi, Saboohi, and Vakili (2021) ascertained the characteristics, frameworks, quantitative indicators, and methods of the analysis of energy system resilience. Jesse et al. (2024) recently reviewed the definition of energy system resilience to gain better understanding. Mazur et al. (2019) presented a divergent approach. Insinuating the prospect of integrating sustainability and resilience objectives, the authors intend to promote the goal of global and local sustainability by conducting an in-depth review of existing frameworks to compile information on general resilience in energy systems with applications to rural areas. Boche et al. (2022) undertook a review to generate a framework for comprehending scientific articles on sustainability micro-grid system within technical and social fields although literature that address either sustainability or resilience were studied.

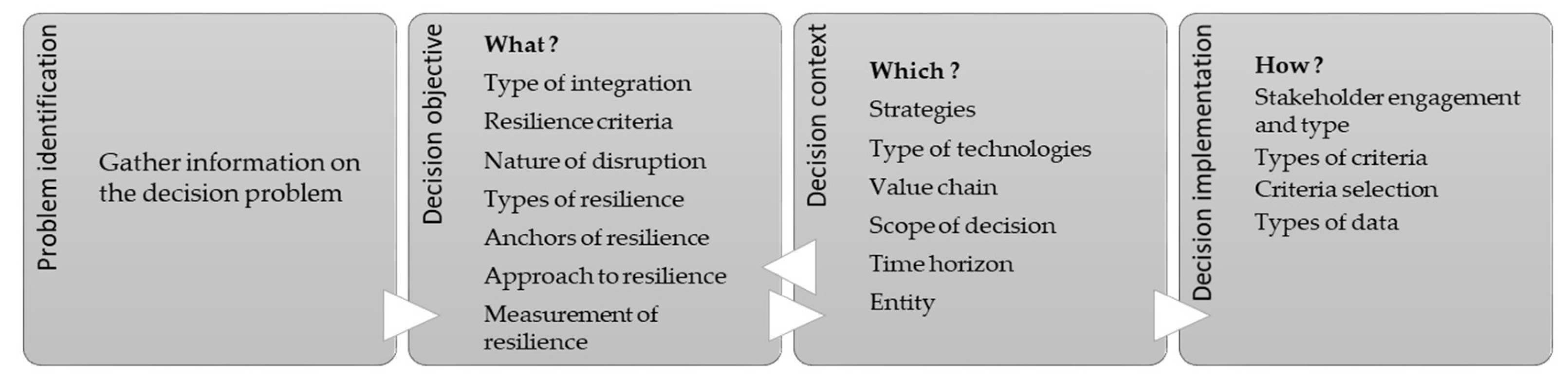

According to the literature summary presented in

Table 1, Mazur et al. (2019) serves as a pointer for an integrated study. However, a few review articles after the year of publication still addressed sustainability and resilience separately. Previous studies have focused mostly on the ‘how’ and ‘what’ of energy planning, addressing methodological and conceptual issues, whereas the ‘what’, ‘which’ and ‘how’ of planning are all relevant for specificity (Gaudreau & Gibson, 2010) as explained under D-OCI framework in the methods section. Regarding the system boundary, none of the studies addressed electrical systems in particular, considering both sustainability and resilience objectives at the same time. The above discussion highlights the paucity of studies dedicated to investigating the integration of sustainability and resilience objectives for energy (electrical) system decisions; and answering the ‘what’, ’which’, and ‘how’ questions. Consequently, this study answers some pertinent questions that could provide guidance for incorporating the two objectives, drawing inspiration from “there is no clarity on what practices could jointly advance both areas” (Negri et al., 2021). Its significance lies in the investigation of practices that can enhance effective energy planning by providing more recent and comprehensive insights and guides for energy evaluation.

Table 1.

Summary of selected previous reviews.

Table 1.

Summary of selected previous reviews.

| Author |

Objective |

Scope of review |

Method |

System Addressed |

| (G. Liu, 2014) |

Sustainability |

Method |

Comparative analysis |

Renewable energy systems |

| (Thygesen & Agarwal, 2014) |

Sustainability |

Conceptualization and method |

Qualitative analysis, comparative analysis |

Wind power |

| (Mardani et al., 2016) |

Sustainability |

Method |

systematic reviews and meta-analyses |

Energy management |

| (Martín-gamboa et al., 2017) |

Sustainability |

Method |

Descriptive and in-depth analysis |

Energy systems |

| (Horschig & Thrän, 2017) |

Sustainability |

Method |

Descriptive and in-depth analysis |

Energy system |

| (Vlachokostas et al., 2020) |

Sustainability |

Method |

Critical review |

Waste-to-energy |

| (Lassio et al., 2021) |

Sustainability |

Method |

Bibliometric and frequency analysis |

Electricity generation |

| (Dantas & Soares, 2022) |

Sustainability |

Method |

Bibliometric, publication trends and comparative analysis |

Energy sector |

| (Kumar et al., 2022) |

Sustainability |

Method |

Extensive review |

Energy system |

| (Zhang et al., 2021) |

Sustainability |

Method |

Comparative analysis |

Hydropower |

| (Abdul Murad et al., 2019) |

Sustainability |

Conceptualization |

Mini review/qualitative |

Some aspect of energy involved |

| Mola et al. (2018) |

Resilience |

Conceptualization and method |

Bibliometric analysis |

Electrical infrastructural system |

| (B. Jesse et al., 2019) |

Resilience |

Conceptualization and method |

In-depth analysis |

Energy systems |

| (Emenike & Falcone, 2020) |

Resilience |

Conceptualization and method |

In-depth analysis |

Natural gas supply chain |

| (Jasiunas et al., 2021) |

Resilience |

Conceptualization |

In-depth analysis |

Energy system |

| (Gasser et al., 2021) |

Resilience |

Overview and method |

In-depth/comparative analysis |

Energy systems |

| (O. P. Aasa et al., 2025) |

Resilience |

Conceptualization |

Systematic review; qualitative analysis |

Energy system |

| (Ahmadi, Saboohi, and Vakili, 2021) |

Resilience |

Method |

In-depth/comparative analysis |

Energy system |

| (B.-J. Jesse et al., 2024) |

Resilience |

Conceptualization |

Bibliometric and descriptive analysis |

Energy system |

| (Mazur et al., 2019) |

Resilience/

sustainability |

Conceptualization |

In-depth review of existing frameworks |

Energy systems |

| (Boche et al., 2022) |

Sustainability (or resilience) |

Conceptualization and challenges |

Systematics and comprehensive review |

Micro-grid energy system |

3. Materials and Methods

A systematic literature review design was adopted for this study because it is a comprehensive framework and one of the best tools for exploring the literature (Dashtpeyma & Ghodsi, 2021). It fits with the purpose of this study, which is to synthesize literature for up-to-date evidence-based practices for energy decisions and analysis and suggest policy and future research directions (Mallidou, 2014). Its weakness is the narrow research questions it addresses, which might limit its suitability for more complex subjects (Jansen, 2017). However, as previous reviews (Lassio et al., 2021; López-Castro & Solano-Charris, 2021) have demonstrated, that this allows for a comprehensive investigation of the topic under consideration rather than a narrow focus. Figure S1 shows the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guide (Page et al., 2021) flow diagram for the study. The study implemented the following steps (Denyer & Tranfield, 2009).

3.1. Formulating Review Questions

The main research question is as follows: what are the trends and practices that can enhance the integration of sustainability and resilience for energy decisions? The specific questions are as follows:

Q1. How are sustainability and resilience integrated?

Q2. How is sustainability assessed?

Q3. What types of disruptions are taken into account?

Q4. What are the types of resilience?

Q5. What are the anchors or attributes of resilience?

Q6. What are the approaches to energy resilience?

Q7. How is resilience assessed?

Q8. What are the system configurations addressed?

Q9. What are the technologies assessed?

Q10. Which energy value chain(s) is/are considered?

Q11. What is the scope of the decisions?

Q12. What is the perspective on the assessment?

Q13. What energy entity is used for decision-making?

Q14. How inclusive is stakeholders’ participation in assessment?

Q15. How are criteria/indicator identified?

Q16. What are the sources of data for decision analysis?

Q17. How are energy decisions analysed?

Q18. What are the types of data used for assessment?

The questions are motivated by a similar study on supply chain network design (López-Castro & Solano-Charris, 2021) as well as the need to go beyond the ‘how’ and ‘what’ of energy decisions, that has been addressed in previous review studies to include ‘which’ as clarified in section 3.4.

3.2. Locating the Studies

The Scopus database was used to identify the articles for the review. Scopus is chosen because it has a larger journal collection and stronger interdisciplinary coverage than others, such as Web of Science. The database has received wide acceptance in several energy planning review articles to date (Steffen, 2020; Yazdi et al., 2023). To ensure the accuracy and completeness of the review, the keywords utilized for searching the database are from a preliminary literature review as recommended by (Negri et al., 2021) between January and May 2023. With prior understanding and familiarity with relevant concepts associated with sustainability and resilience, specific keywords or terms identified were used for the search. However, López-Castro and Solano-Charris (2021) and Negri et al. (2021) provided guidance in framing the search strings because they share similar concepts, albeit in different knowledge areas (Qazi et al., 2019). The title, abstract, and author keywords were used for the search.

3.3. Selecting and Evaluating the Studies

The selected papers were: in the English language, peer-reviewed, in the field of energy; and empirical research papers. The only exception to these inclusion criteria is Gatto and Drago (2020), which has the attributes of a review paper, but Scopus regards it as a research article for unknown reason. Exclusion criteria filter out irrelevant papers after the initial search results. These are: papers not explicitly concentrating on any of the energy systems or any of the value chains, and grey literature, e.g., theses, project deliverables, and working papers. Most grey literature is developed into paper, which will amount to duplication if it is included in the list of literature reviewed . To address the peculiarities of the first exclusion criterion, we conducted an initial scan of titles and abstracts for the initial search results. During this process, some keywords outside the electricity system scope were identified. Thereafter, the keyword exclusion option on Scopus was used to refine the search to exclude studies with those keywords. Articles from initial search consisted of 314 items, of which 299 were available for download. Further review of the articles’ abstracts led to the identification of 81 articles, which were downloaded into Mendeley Reference Manager and Microsoft Excel Spreadsheet. Finally, 34 papers were selected for critical review following two successive thorough examinations of the entire texts, as they suitably addressed the decision objective, context, and implementation. Another search was conducted in January 2025 using the same database and procedure. The motive is to include recently published articles after the initial search in May 2023 (i.e., 2023–2025). This search returned 344 items, of which 29 were not available for download at the time of the search; and 38 duplicates from the previous search were identified, implying 277 were screened for relevance. A review of their abstracts identified 87 articles downloaded into Mendeley Reference Manager and Microsoft Excel Spreadsheet. After full-text readings, 41 were selected for critical review from the second search. Overall, 74 articles were used to achieve the objectives of this review. The list of articles is presented in Table S1 (supplementary material). Figure S1 shows the PRISMA flow diagram for the study.

Table 2.

Advance search terms on Scopus.

Table 2.

Advance search terms on Scopus.

| (TITLE-ABS-KEY(sustainab* AND resilien* AND energy AND assess* OR framework OR evalut* OR criteria OR indicator*) AND ( LIMIT-TO ( SUBJAREA,”ENER” ) ) AND ( LIMIT-TO ( SRCTYPE,”j” ) ) AND ( EXCLUDE ( EXACTKEYWORD,”Blockchain” ) OR EXCLUDE ( EXACTKEYWORD,”Architectural Design” ) OR EXCLUDE ( EXACTKEYWORD,”Information Management” ) OR EXCLUDE ( EXACTKEYWORD,”Air Quality” ) OR EXCLUDE ( EXACTKEYWORD,”Urban Resilience” ) OR EXCLUDE ( EXACTKEYWORD,”Urbanization” ) OR EXCLUDE ( EXACTKEYWORD,”Biodiversity” ) OR EXCLUDE ( EXACTKEYWORD,”Land Use” ) OR EXCLUDE ( EXACTKEYWORD,”Waste Management” ) OR EXCLUDE ( EXACTKEYWORD,”Building” ) OR EXCLUDE ( EXACTKEYWORD,”Food Supply” ) OR EXCLUDE ( EXACTKEYWORD,”Food Production” ) OR EXCLUDE ( EXACTKEYWORD,”Buildings” ) OR EXCLUDE ( EXACTKEYWORD,”Cooling Systems” ) OR EXCLUDE ( EXACTKEYWORD,”Competition” ) ) AND ( LIMIT-TO ( LANGUAGE,”English” ) ) AND ( LIMIT-TO ( DOCTYPE,”ar” ) ) ) |

3.4. Analysis and Synthesis

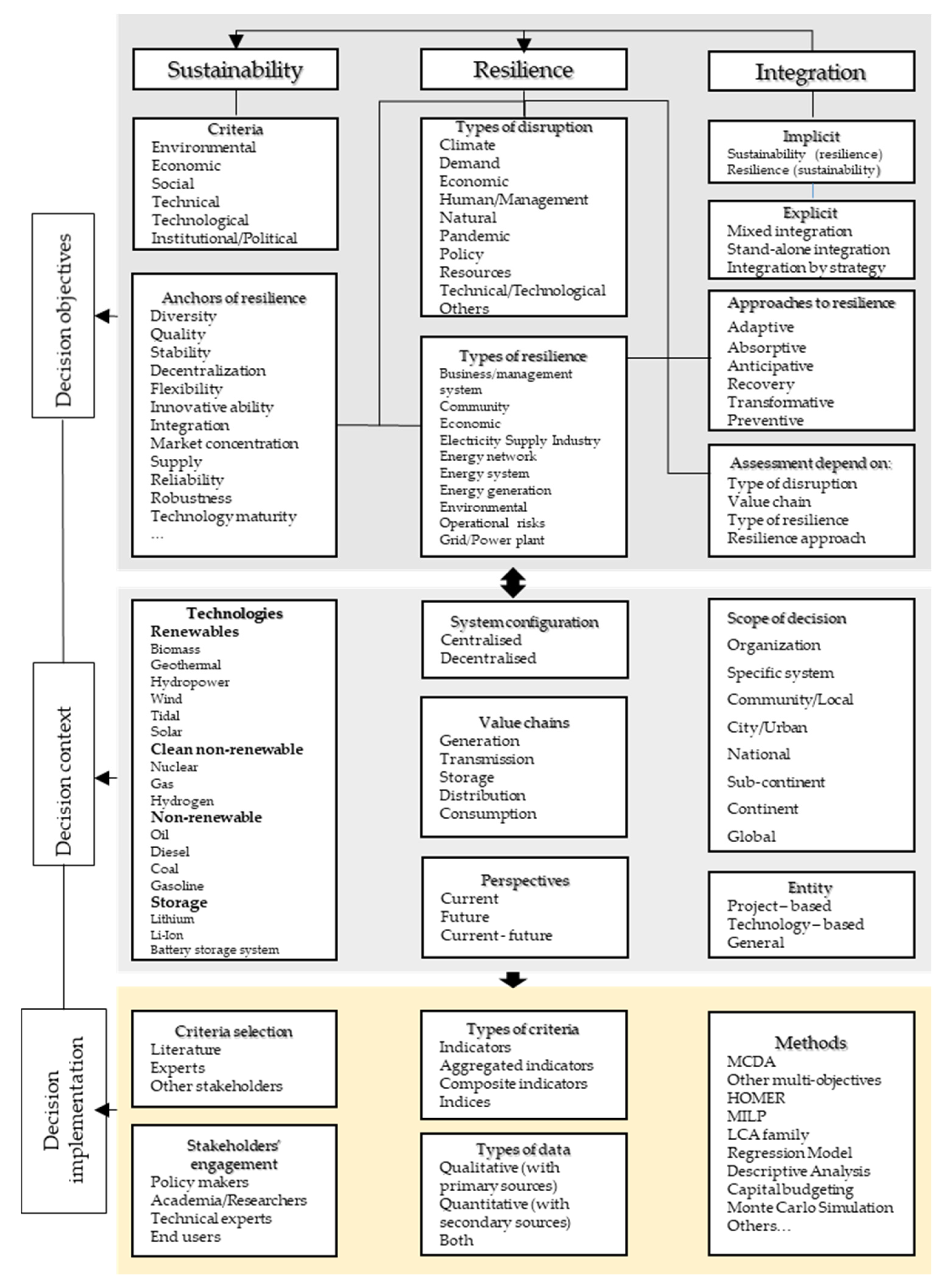

To analyse the selected papers,

a classification scheme was developed as recommended (López-Castro & Solano-Charris, 2021) as shown in

Figure 1. The scheme presents the contents of the articles under decision-making themes. Related content is synthesized to form a cohesive and comprehensive decision guide by grouping the 17 specific review questions under the themes. The themes are decision objective (D-O), decision context (D-C), and decision implementation (D-I) (D-OCI), which are linked to Q1–Q7, Q8–Q13, and Q14–Q18, respectively. Q1–Q18 are the specific questions. Aside from addressing ‘how’ (methodology aspect), the synthesis of the contents addressed the ‘what’ and ‘which’ questions to promote an optimal perspective and course of action for formulating energy policy. Within the frame of this study, the questions linked to D-O (what) help decision makers focus on what they intend to achieve or what the decision is about. In this study, the focus is specific elements necessary to achieve the sustainability and resilience objectives in the energy system. The D-C questions (which) are the basis for D-O. Establishing the context clarifies which issues or factors that can affect the outcome of energy decision. D-I questions (how) cover how decisions are evaluated. Generally, the scheme addresses case- and context-specific energy decisions by providing decision-makers (DMs) with options from elements under different themes rather than generalizing strategies to achieve the objectives, which is unlikely to be effective because of the uniqueness of each element.

Section 5 explains how D-OCI can be implemented.

The analysis and synthesis techniques used in the study include bibliographic and comparative presentations in tables, charts/figures, trends, and frequency/percentage distributions for ease of visualization. Qualitative justifications were also used to support these techniques.

3.5. Reporting and Using the Results

The results and discussion with practical implications are presented in

Section 4.

4. Results

4.1. Trend Towards the Integration of Sustainability and Resilience

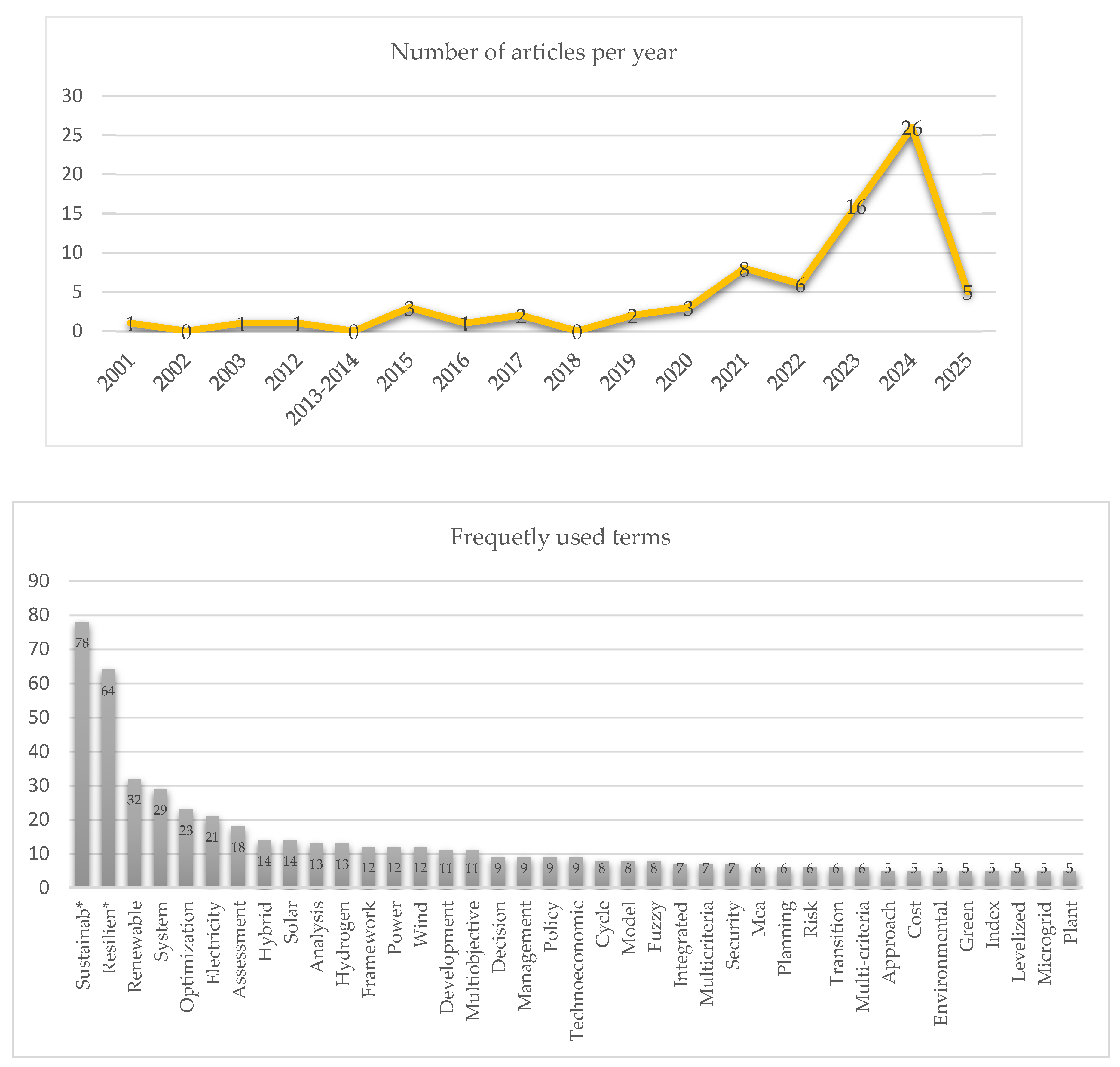

Figure 2 (a) illustrates the number of articles published each year from 2001 to 2025. While the first articles appeared in 2001, the annual publication rate was minimal during the initial two decades (up to 2020), representing only 18.6 per cent. However, this trend has since shifted, with a notable increase of 81.3 per cent from 2021 to early 2025. Remarkably, five articles emerged by mid-January 2025, suggesting the potential for even greater publication numbers than in previous years. This trend underscores the rising importance of achieving sustainability and resilience objectives in the energy sector as the global community nears the SDG 7 timeline.

Figure 2 (b) displays the key terms utilised in the articles. The first two terms, ‘sustainab*’ and ‘resilien*’, highlight the focus of this study and their prominence as leading terms. Following these are ‘renewable’, ‘system’, ‘optimisation’, ‘electric*’, and ‘assessment’. This depiction further emphasises the significance of renewable technologies within the electricity system and the need to evaluate candidate technologies during energy planning. Additional key terms can be found in the figure.

4.2. Decision Objectives (D-O)

This section addresses the core of energy decision, elements of decision objective, mostly from the conceptual perspective.

4.2.1. Types of Integration

The integration of the objectives can be achieved in two major ways as deduced from the identified articles—implicit and explicit integrations. Articles categorized as implicit demonstrated that either of the concepts can be addressed implicitly when the other is the central theme. For example, when a study whose primary focus is sustainability addresses resilience latently and vice versa. There are two aspects to this:

(a) Sustainability objective (with implicit integration of resilience issues) (SR)

According to some studies, sustainability objective can promote resilience issues implicitly. While Yue et al. (2001) emphasized resilience concept of ‘decentralization’ as means to transition toward a sustainable energy future, Spalding-fecher (2003) aggregated indicators of progress toward sustainability in the energy sector by introducing technologies that are renewable, introducing an economic perspective to resilience. The energy transition study by (Herbert et al., 2016) introduced resilience thinking of the diversity of energy technologies in the energy portfolio as applied to electricity generation in its sustainability assessment. In a quantitative life cycle assessment framework, Moslehi and Reddy (2019) addressed the sustainability of energy systems, but resilience is seen as one of the two ways to achieve sustainability in an engineered system. The resilience aspect is the diversity of the portfolio of sources that have the highest chance of preventing disruptions. Similarly, resilience is one of the criteria in the sustainability assessment framework for power system planning (Cano-andrade, 2017). The perspective of Wang et al. (2021) was that energy transitions contribute to adaptive policies for responding to climate change. Thus, security was a key reflection of energy resilience in this study, as it assesses energy transition policy from a sustainable development perspective. Finally Odoi-yorke et al. (2022) is concerned with decision-making method for assessing hybrid energy system from renewable sources for greening business even as Pal and Shankar (2023) focused on sustainability performance of smart grid, of which critical success factors to aid performance included resilience related attributes or capabilities. Wehbi (2024), justifying the role of sustainable energy planning and resiliency, developed a framework for a renewable energy transition based on five dimensions of sustainability. Li et al. (2024) assessed the sustainability of geothermal power to promote the resiliency of the generation system. Hassan et al. (2025) analysed the economic and environmental aspects of transitioning to renewable energy and green hydrogen to promote energy security by 2030. The techno-economic study by Maaloum et al. (2024) highlighted the resilience of future investment in green hydrogen when renewable technology is used for its production.

(b) Resilience objective (with implicit integration of sustainability issues) (RS)

Here, the resilience objective can address sustainability objectives implicitly to achieve different energy goals. First, Mujjuni et al. (2021) developed a framework for resilience assessment as a means to achieve development, with sustainability as one of its goals. Another article measured resilience from an economic perspective rather than from engineering or physical aspects, which are common in resilience studies and examined the effect of resilience on CO2 emissions (Phoumin et al., 2021). Dong et al. (2021) studied how energy resilience affects carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions thereby contributing to environmental sustainability. Using sustainability as factor or strategy to achieve resilience, Dashtpeyma and Ghodsi (2021) developed a resilient solar energy management system but their later study identified and evaluated the enablers of resilience capability in the wind power sector to design, develop and optimize a resilient management system to achieving sustainable energy management (Dashtpeyma & Ghodsi, 2022). The scope of the study by González-Delgado et al. (2023) was the economic and techno-economic resilience of power generation through large scale production routes of hydrogen by indirect gasification using African palm fruit. In Haro-baez et al. (2025), authors are interested in strategies for promoting resilience in clean energy infrastructure on an island. The approach ensures energy security and sustainability.

Articles under the explicit integration category revealed that the two objectives could be integrated without ambiguity. Specific issues related to the two concepts such as the criteria/metrics/ indicators, could be clearly identified as part of their evaluation process.

(a) Mixed integration (R-S): This involves incorporating sustainability and resilience assessment criteria distinctively, though not separated. That is, the contributions of the two objectives to energy decisions are not separate. For example, to present an analysis of resilient energy system analysis and planning, both resilience and sustainability were included in the composite resilience index because of their overlapping goals (Yazdanie, 2023). In the case of Grafakos et al. (2017), an integrated sustainability and resilience framework for low-carbon energy technologies assessments at the local level was developed, similar to assessing low-carbon energy technologies against sustainability and resilience criteria (Grafakos & Flamos, 2015). Sustainability is the means to achieve resilience in the sustainable resilience of hydrogen energy systems (Afgan & Veziroglu, 2012), whereas resilience has been applied to sustainability criteria in the assessment framework for hydrogen energy infrastructure development (Yazdi et al., 2023). Gholami (2024) developed a multi-criteria framework to improve sustainability and resilience. The study was implemented to address the changing energy needs and the problems with adding renewable energy. Liu et al., (2024a) developed an inclusive framework that improves the efficiency and sustainability of energy systems. Liu et al., (2024b) conducted an evaluation and selected the optimal power grid options for multi-energy systems, taking into account resilience and sustainability indicators.

(b) Stand-alone integration (R_S): In this situation, both sustainability and resilience stand as individual objectives within the main goal of the energy transition. For strategic planning for balancing the trilemma of energy for energy system planning in coastal cities, different pathways for a sustainable transition have been evaluated with resilience as one of the three objectives (Jing et al., 2021). Salehi et al. (2022) undertook the design of a resilient and sustainable biomass supply network via an optimization method. Among other factors, the study examined the associations between resilience factors and sustainability indicators by specifying the two objectives within the biomass supply chain. In the dynamic sustainability framework for petroleum refinery projects, sustainability criteria was examined against some pillars of resilience (Hasheminasab et al., 2020). Others are economic and environmental criteria of sustainability (Jing et al., 2021). In a study on marine energy in coastal communities, Kazimierczuk et al. (2023) listed community energy goals such as energy security, affordability, resilience, environmental sustainability, and economic growth. Gruber et al. (2024) measured both aspects of resilience and sustainability separately using economic and technical goals, respectively.

(c) Integration by strategy (IS): As a result of reviewing additional articles published between 2023 and 2025, new trends were observed in the integration of both objectives. There are more studies evaluating strategies that support both objectives simultaneously during the period. Therefore, it cannot be stated categorically whether an evaluation is meant to capture either objective, but there are explicit statements that justify classifying them as explicit integration based on the strategies pursued. Examples include the application of an integrated waste-to-energy approach to resilient energy system design for sustainable cities and communities (Babalola et al., 2022). To achieve SDG 7 through a reduction in fossil fuel and electricity costs, Eras-almeida et al. (2020) leveraged how to achieve a resilient energy supply through diverse options or a combination of options to implement this goal. Ala et al. (2023)’s interest lies in achieving resilience and long-term security of sustainable energy planning. Ba-alawi, Nguyen, Aamer, et al. (2024) optimised sustainable green hydrogen energy storage to address the intermittent challenges of solar and wind energy production resulting from adverse weather conditions. The study conducted a sustainability analysis before determining which resilience option offers the greatest safety or minimal risk. Ba-alawi, Nguyen, and Yoo (2024) undertook a study to improve the strategic management and planning of water energy systems to reduce operational and emission expenses while maximising system resilience within the generation and distribution network. Castro et al. (2023) used a techno-economic analysis to assess the significance and effects of incorporating storm hardening measures and insurance into a hybrid renewable energy system. Araria et al. (2024) propose a sustainable approach for offshore energy generation to address resilience concerns linked with intermittency. Dongyang et al. (2024) examined dynamic adaptation strategies in power transmission to deal with problems that arise because of the growing reliance on renewable energy for the long-term management of power transmission systems. Tangi and Amaranto (2025) created a decision-analytic framework that combines the single-objective simulation-optimisation model with multi-objective evolutionary algorithms to help plan the best, most sustainable, and resilient multi-energy systems. Different algorithms are evaluated, and the most effective method is employed to derive ideal designs based on fluctuating renewable energy generation potential and energy cost. Elkholy et al. (2024) address the implementation of an effective hybrid power system in two primary phases. Initially, it seeks to enhance the performance of individual renewable energy sources (RESs), guaranteeing their optimal efficiency. Secondly, it employs artificial intelligence to optimise energy distribution inside the micro-grid. The main emphasis is on guaranteeing the reliability, sustainability, and cost-efficiency of micro-grid operations using a hybrid optimisation algorithm. Shah et al., (2023) investigated the optimal system size for resilience and reliable load servicing of a 100% hybrid renewable energy system using the multi-objective genetic algorithm (MOGA) optimisation technique, based on the premise that off-grid electrification of remote areas with sustainable energy systems (SES) is essential for achieving sustainable development goals.

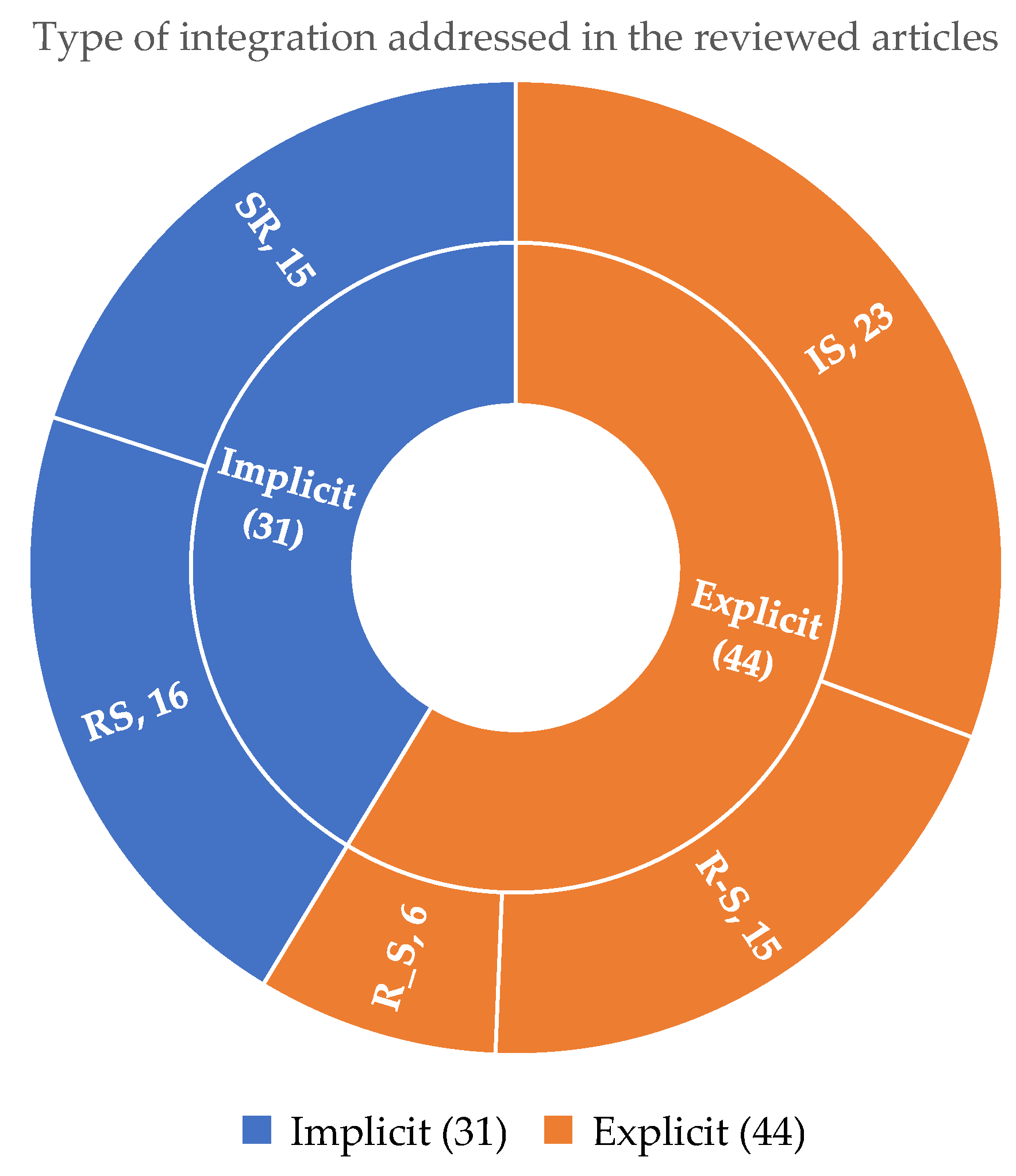

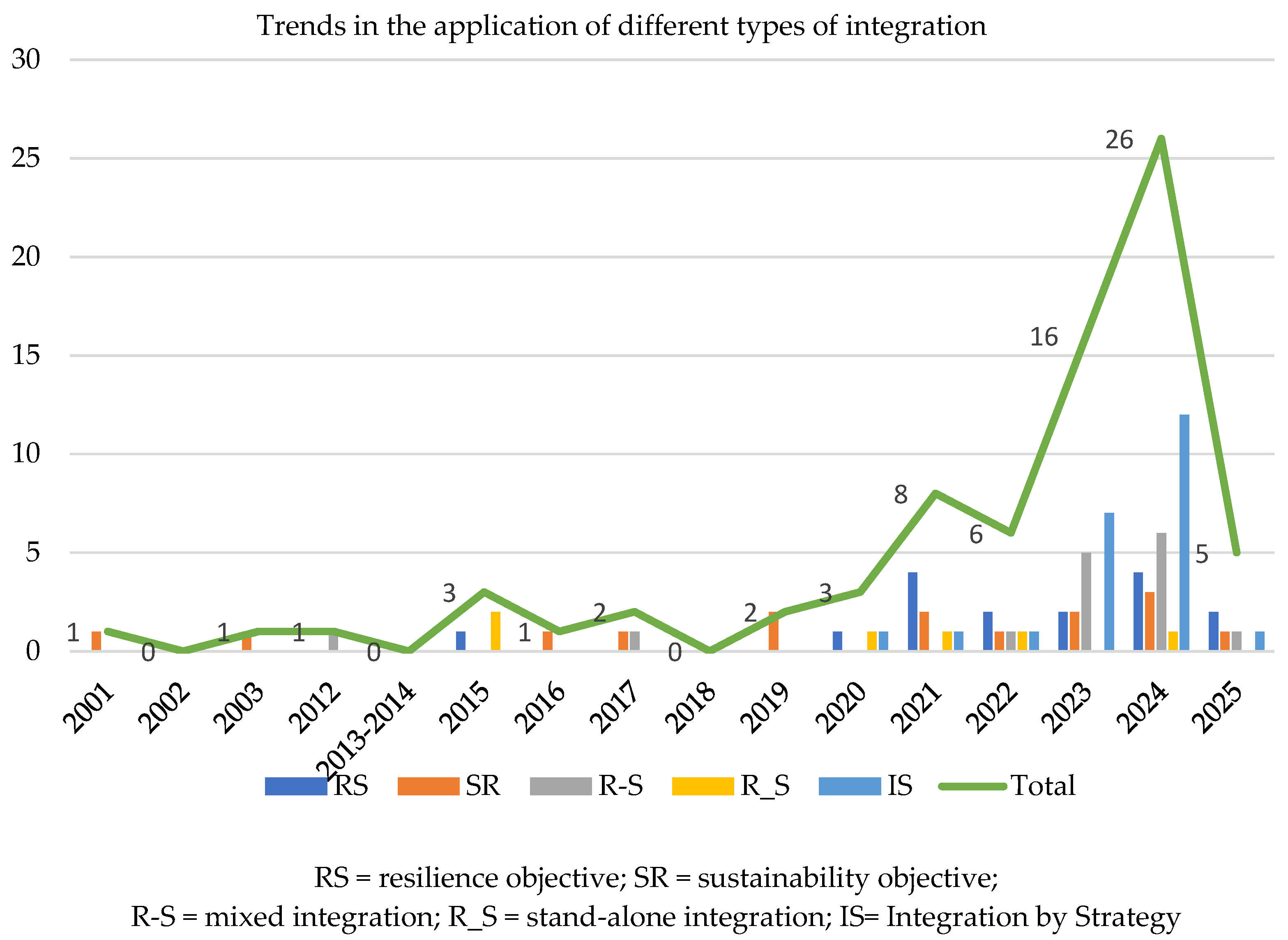

As presented in

Figure 3(a), the number of articles classified as explicit integration (44) is more than those under implicit integration (31). IS (23) is the most adopted approach for integration, followed by RS (16). Both SR and R-S have an equal number of articles (15), while R_S (6) has the least number of articles. Furthermore,

Figure 3 (b) shows that the initial years were dominated by implicit integration while explicit integration began to receive more attention from the research community from 2020 upwards.

4.2.2. Sustainability Objective

Table 3 presents the sustainability criteria and indicators identified during the content analysis of the reviewed articles. The ticked boxes indicate the criteria/indicators identified in the articles. When at least one indicator associated with a criterion is identified, the criterion box is also ticked. Where it is not very clear which indicator(s) was addressed, only the criterion box was ticked if there is evidence that the criterion was addressed. In addition, the captions given to indicators represent general identifiers, which means they may not be the actual terms used in some of the articles. According to the table, six criteria can be identified, which are environmental, economic, technical, social, technological and institutional/political dimensions. Economic dimension was relevant in most energy planning occurring in 80.0 per cent of the articles. Its indicators include the cost of establishing power facilities or expansion, operation and maintenance, and repair, fuel cost, occupation, energy production, earning (NPV, IRR, ROI,, NPC)), and payback period (as well as lifespan of investment). Some indicators have limited usage, such as “investment and financing policy” (Dashtpeyma & Ghodsi, 2022)

, “grid electricity purchase” (Odoi-yorke et al., 2022), “supply chain cost” (Salehi et al., 2022), “economic performance” (Hasheminasab et al., 2020), cost of energy (Ali et al., 2024), insurance premium (Castro et al., 2023) and cost of balancing (Shobayo & Dao, 2024). The environmental aspect has also gained much (77.3 per cent) attention although not as economic criterion. Frequently occurring indicators are CO

2 emissions and other air pollutants, ecosystem damage/impact (including health), resource usage (fuel, water, land, etc.), noise pollution, waste generation/ reduction and waste disposal (including infrastructure). Some indicators are unique to some studies, such as “unburned hydrocarbon” (Odoi-yorke et al., 2022), “land and soil pollution”, (Hasheminasab et al., 2020), “environmental cost” (Ba-alawi, Nguyen, & Yoo, 2024), “compatibility with national heritage” and “green economy”(Gholami, 2024). As evident in

Table 3, the technical criteria ranked third (54.7 per cent) in terms of inclusion in the energy assessment. It is measured in terms of capacity adequacy (as a capacity factor; rated capacity, unmet load), maximum capacity for energy technology, maximum capacity for energy technology, peak demand, electricity production, and operational capabilities, which are the recurring sub-criteria in the articles. Other less common indicators are “permissible lowest/highest limitations of increased technologies in periods” (Ala et al., 2023), “energy security” (Wehbi, 2024; Yazdanie, 2023), and “technically accessible resource and resource availability” (Beriro et al., 2022) “service integrity (or reliability)” (Babalola et al., 2022) and energy savings (Amin, Hossain, et al., 2023; Xue et al., 2024). Social factors are fourth (34.7 per cent) and has been used in the form of employment (job creation, wages, etc.), social fairness in the distribution of technology, welfare and health, social acceptance, safety and security, community engagement, aesthetic/functional impact and mortality, morbidity accidents/fatalities (tendencies). The Human Development Index (Ali et al., 2024) is used in only one article.

The technological criteria (32.0 per cent) can be distinguished from the technical criteria, because they mostly address the concrete aspects energy source or enablers that make the process (technical aspect) to run smoothly to ensure continues energy usage. Compared with the earlier identified criteria, the technological aspect has fewer uses. Indicators include technical and non-technical innovations, market size (domestic), flexibility, technological maturity, market size (potential), market size (potential), and use of renewables. Other indicators with limited use are construction duration (Ala et al., 2023); techno-feasibility; operational and cross-border control smart design (Dashtpeyma & Ghodsi, 2022); and deployment viability (supply chain) (Beriro et al., 2022), which are also relevant in specific situations. The dimension with the lowest degree of occurrence is institutional criteria (17.3 per cent). The fact that the publications that featured it are recent confirms that it has recently gained recognition in sustainability assessment. The most occurring indicators include organisation, policy support, regulatory framework, political stability/acceptance, legal compliance, and education, training, and skills, while institutional capacity occurred only in (Wehbi, 2024). Furthermore, some articles combine two criteria, i.e., socio-economic (Eras-almeida et al., 2020) and techno-economic (Dashtpeyma & Ghodsi, 2022), among other articles.

4.2.3. Resilience Objective

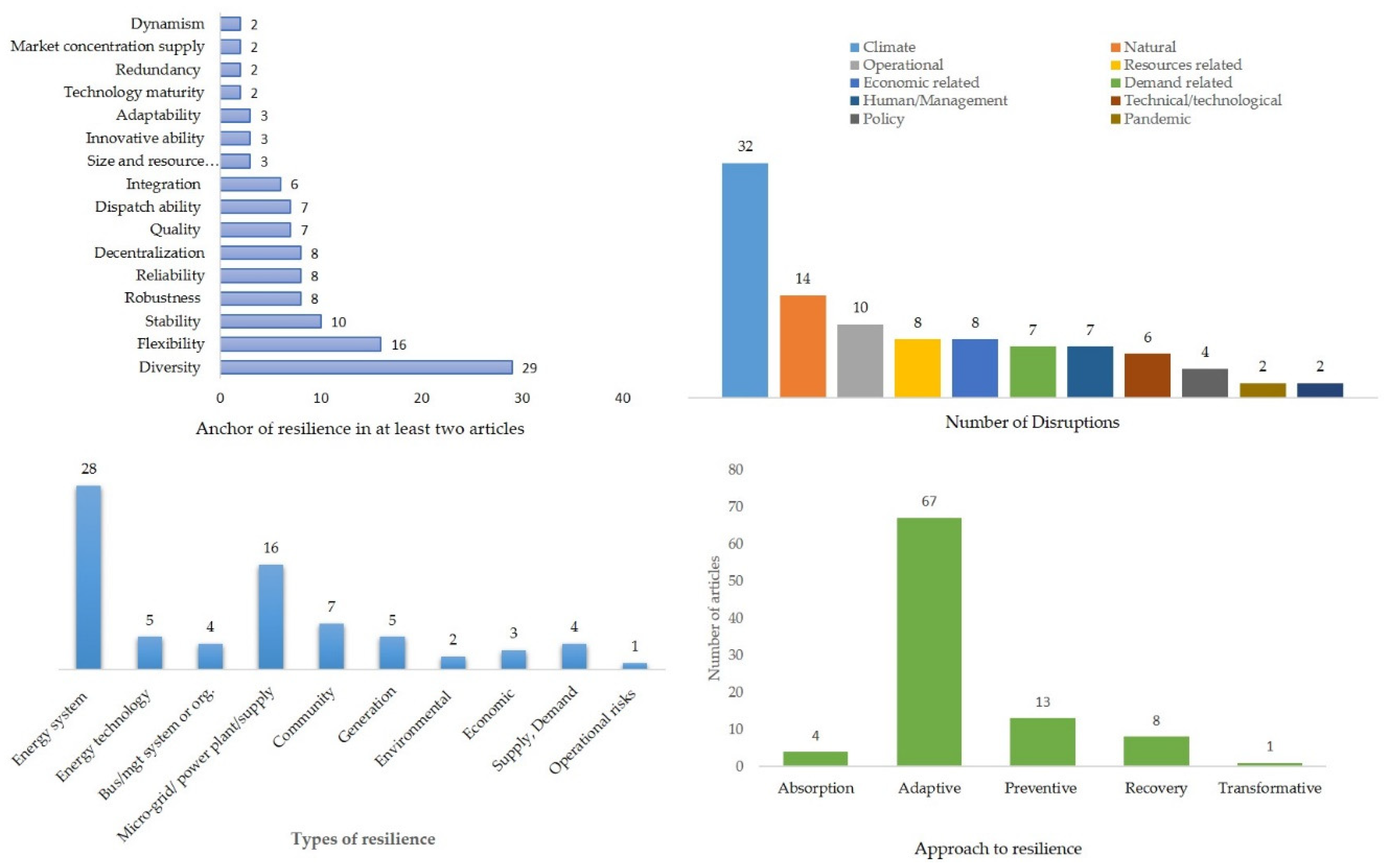

Although both sustainability and resilience are important in energy transitions, it seems that the chances of effective energy planning can be attained when critical system issues, which are mostly associated with threats or shocks and/or resilience, are incorporated. As displayed in

Figure 4, decisions should address a variety of threats, which were classified into 10 groups (See Table S2 of the supplementary material for the list of disruptions addressed in each of the articles).

Figure 4 depicts the cluster columns for each group. The highest cluster includes only climate-related disruptions with frequency counts of 32, followed by ‘natural disasters’ (14) and ’operational’ and ‘resources’ (8) in the second, third, and fourth positions. The next cluster includes ’economic’ and ‘demand’ threats, which have 7 articles each. The least occurred threats are ‘technical, technological’ (6), ‘policy’ (4), ‘pandemic’ (2), and other factors (2).

Furthermore, decisions should address different types of resilience. To determine the type of resilience addressed by the studies, the authors relied on the article title, abstract, and/or methodology sections of the articles. When this was not entirely clear, the authors relied on the explanations provided in the articles in comparison to articles with similar contributions. Energy system resilience (28) is the most common. Other types of resilience reported in at least two articles include micro-grids and power plants/supply (16), community energy (7), energy technology (5), energy generation (5), supply and demand (4), and business/management systems or organisations (4). Economic, environmental, and operational resilience are the least common. Approaches to resilience provide an explanation of how the articles aim to achieve resilience.

Figure 4 shows that the approach to energy resilience is mostly adaptive (67). Other approaches include preventive, recovery, absorptive, and transformative in descending order of occurrence. It is also possible to use more than one approach, such as in Afgan and Veziroglu (2012) who mentioned both adaptive and recovery, similar to Mujjuni et al. (2021) who combined adaptive, absorptive, anticipative, and transformative approaches, and Yazdi et al. (2023) who focused on recovery, absorptive and preventive strategies. Janta et al. (2024) identified preparedness, absorbability, recoverability, and adaptability, while Murshed et al. (2023) mentioned adaptive, preventive, and anticipative.

Anchors of resilience help to achieve the listed approaches, reflecting attributes or initiatives that make energy system or any of its value chains more resilient. A higher performance of attributes increases the degree of resilience of the energy system.

Figure 4 presents attributes that appear in at least two articles. Apparently, ‘diversity’ is the most measured attribute, occurring in 29 articles. Diversity can be related to the degree of functionality and responsiveness ((Kharrazi et al., 2015). ‘Flexibility’ and ’stability’ appeared in 16 and 10 articles, respectively, whereas ‘decentralisation,’ ‘reliability,’ and ‘robustness’ featured in 8 articles each. While ‘dispatch ability’ and ‘quality’ were addressed in 7 articles, ‘integration’ emerged in 6 articles.

Compared to sustainability, resilience assessment is more complex, as it requires different considerations such as the type of disruption (single or multiple), value chain (or entire system), and type of resilience among others. Thus, it is difficult if not impracticable to classify criteria/indicators for measuring resilience in the same way that it was done for sustainability. Every assessment is likely to have unique components, except for adoption where a new assessment share similar characteristics with an existing assessment. However, the aforementioned anchors of resilience have been used to measure the degree of resilience in some studies. These include stability of energy generation (Grafakos et al., 2017), flexibility (Amin, Hasnat, et al., 2023; Dashtpeyma & Ghodsi, 2022), and integration (Dashtpeyma & Ghodsi, 2021; Pal & Shankar, 2023). Others are diversity (Jing et al., 2021; Sharmin & Dhakal, 2022), decentralization (Yazdanie, 2023), reliability (C.-K. Wang et al., 2021), robustness (Yazdi et al., 2023), and technology maturity (Grafakos et al., 2017), among others. Another trend in the evaluation of resilience is measurement—or optimization— through the lens of sustainability criteria. For instance, Yazdi et al. (2023) addressed the resilience index by using technical, social, economic, and organisational resilience. Castro et al. (2023), González-Delgado et al. (2023), Tayyab et al. (2024) focus on the techno-economic assessment of resilience strategies. Gruber et al. (2024) measured technical goals as a proxy for resilience, while Pérez-Denicia et al. (2021)measured it directly using economic, environmental, and social criteria. Resilience was implied from environmental, technical, political, and economic factors (Beriro et al., 2022). The supplementary material summarizes how individual articles have assessed resilience.

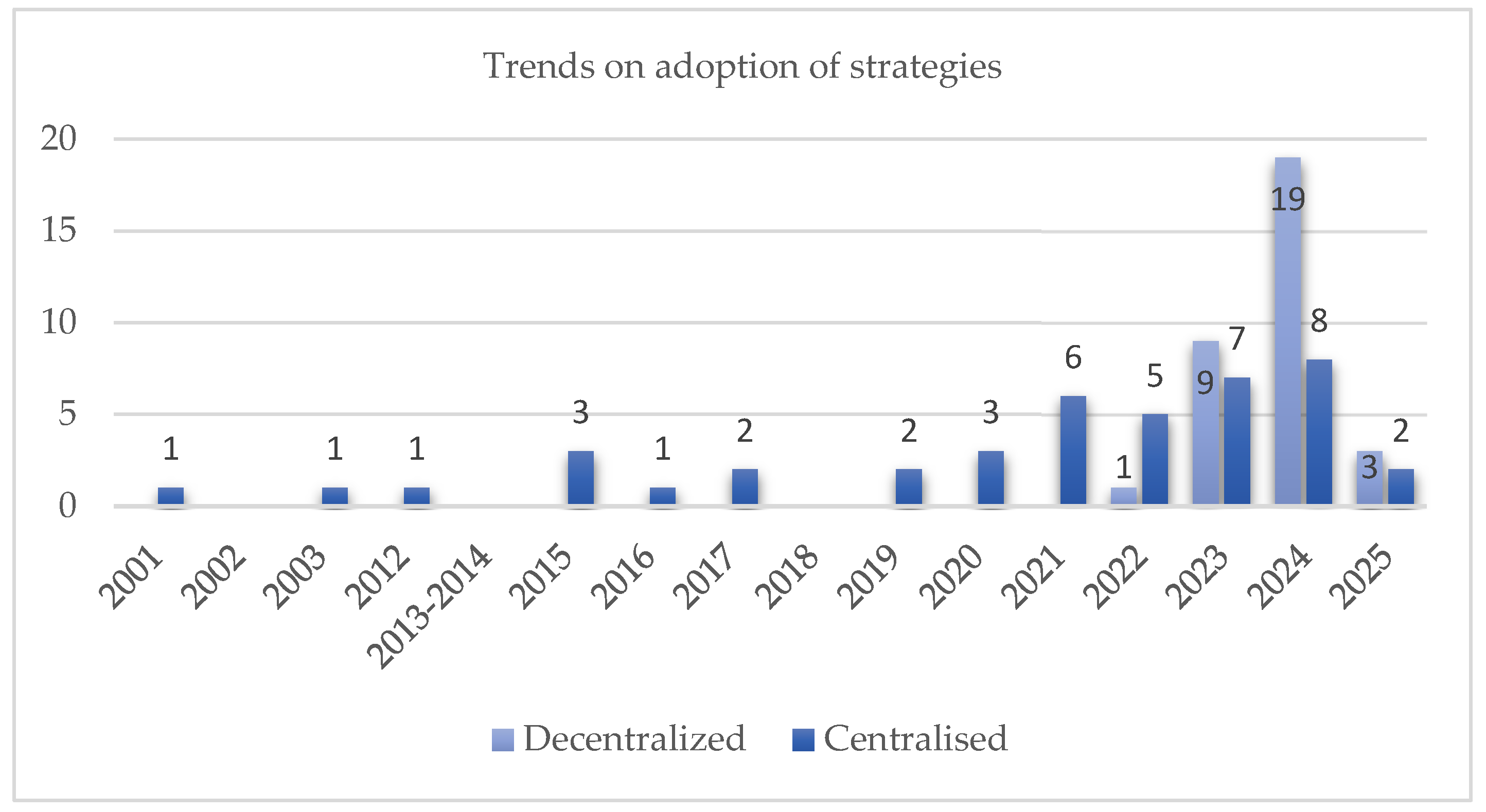

4.3. Decision Context (D-C)

The decision context addresses the setting, issues or factors that affect the decision evaluation such as the system configuration, value chain, technology, perspective to decision, decision term, entity or unit and decision scope. The review revealed two main configurations, centralised and decentralised. Where an article is not specific about the configuration, it is assumed to be centralised because, based on findings during the review, those addressing decentralised systems are more specific about it compared to those addressing traditional grid systems. According to

Figure 5, in earlier years, articles focused on centralised systems until recently, when attention began to shift towards off-grid solutions. The shift is due to the disruptions in the larger system and their large-scale effect. Thus, decentralisation may be an effective strategy to address sustainability and resilience issues simultaneously. To confirm this proposition, the correlation matrix in

Table 4 shows strong relationships between integration approaches and the system configuration used.

Various technology options are available to boost performance in terms of sustainability and resilience. Technologies can be classified into two categories: energy generation and storage. Those for generation can be grouped into renewables, non-renewables, and cleaner non-renewables. Renewable options include solar, biomass, wind, hydro, geothermal, tidal, and wave, although solar (52.0 per cent), wind (32.0 per cent), and biomass (20.0 per cent) have been widely used to address energy transition (

Table 5). Nuclear (a derivative of uranium), gas, and hydrogen are cleaner non-renewables, but hydrogen (22.7 per cent) has received more attention. Under the non-renewables group, the diesel power engine (21.3 per cent) is prominent as a backup to other technologies, although linked to a decentralised system. Others are coal (14.7 per cent), oil (9.3 per cent) and gasoline (2.7 per cent). On the other hand, some technologies have been used to store excess energy, most especially in a system comprising Variable Renewable Energy (VRE), as revealed in 21.3 per cent of the articles, which is why different storage strategies are being studied lately (He et al., 2025; Sawhney et al., 2024; Shobayo & Dao, 2024). Common storage technologies include battery energy storage systems (BESS), lithium and cryogenic (Misra et al., 2024), lithium (Castro et al., 2023), and Li-Ion (Ali et al., 2024). The descriptive statistics under

Table 5 show that most energy decisions (65.3 per cent) are multi-energy focused, some of which involve both renewables and non-renewables (29.3 per cent) or only renewables (28.0 per cent). Other combinations include renewable, non-renewable, and storage (10.7 per cent), renewables and cleaner non-renewables only (8.0 per cent), renewables with storage (5.3 percent), non-renewable with storage (2.7 per cent), and cleaner renewables with storage (8 per cent).

Moreover, the value chains represent stages or activities necessary to make energy available for end usage. The current review investigated the value chains implemented in the identified studies. These are generation, transmission/transportation, storage, distribution, consumption, and general energy systems. The results presented in

Table 6 show that 64.0 per cent of the studies addressed ‘energy generation’. While 14.6 per cent of the studies addressed ‘transmission’, 13.3 per cent, 9.3 per cent and 6.7 per cent focused on ‘distribution’, ‘storage’ and ’consumption’ respectively. Energy decisions can address the entire energy system (24.0 per cent) of an entity or multiple value chains, as exemplified in 24.0 per cent of the articles. Some examples are Afgan and Veziroglu (2012) and Hasheminasab et al. (2020), both of which look at five value chains. Sharmin and Dhakal (2022) and Pal and Shankar (2023) investigated four value chains, while Beriro et al. (2022), Moslehi and Reddy (2019), and Mujjuni et al. (2021) look at three each. Babalola et al. (2022), and Eras-almeida et al. (2020) focused on two each. Very few articles have addressed other aspects, such as energy demand (Pal & Shankar, 2023)

, supply (Haro-baez et al., 2025; Maaloum et al., 2024; Zhao et al., 2024), supply and demand (Miao et al., 2023), and sector (Gatto & Drago, 2020a).

According to

Table 7, nine levels of application are realistic. In descending order of the number of sources, they are local/community (24), national (14), city/urban/municipal (11), power plant/energy generation/project/specific system (9), organisational (4), global (3), and continent or sub-continent (2). Studies (Grafakos et al., 2015; Grafakos et al., 2017) seem to be unique in that they address local energy transition issues but within a European continent. Thus, they were not included in the list presented in

Table 5. These findings prove that there has been more application of studies to national, local/community and specific system contexts. Continent or Sub-continent have has received little attention

The review demonstrates that decisions should consider the time horizon of assessment (i.e., either current or future orientation).

Table 8 shows that most of the articles (52) are future-orientated while a few are current (9) in nature. Another set of articles is both current and future-focused (14). The basis of this classification is whether an article is aimed at improving current performance or helping to make optimum decisions targeted at future times. The former prioritises the current perspective, whereas the latter focuses on the future. Those that consider both perspectives invariably seek to improve the state of the art while looking forward to future decisions. Energy entity refers to the unit used for decision-making. The review identified both project-based and technology-based decisions contexts. Technology-based energy planning appraisal has been the focus of most articles (65), whereas only 6 per cent are project-based assessments, just as 94 are not specific about their basis of decision, at least on the basis of authors’ judgement (see

Table 6).

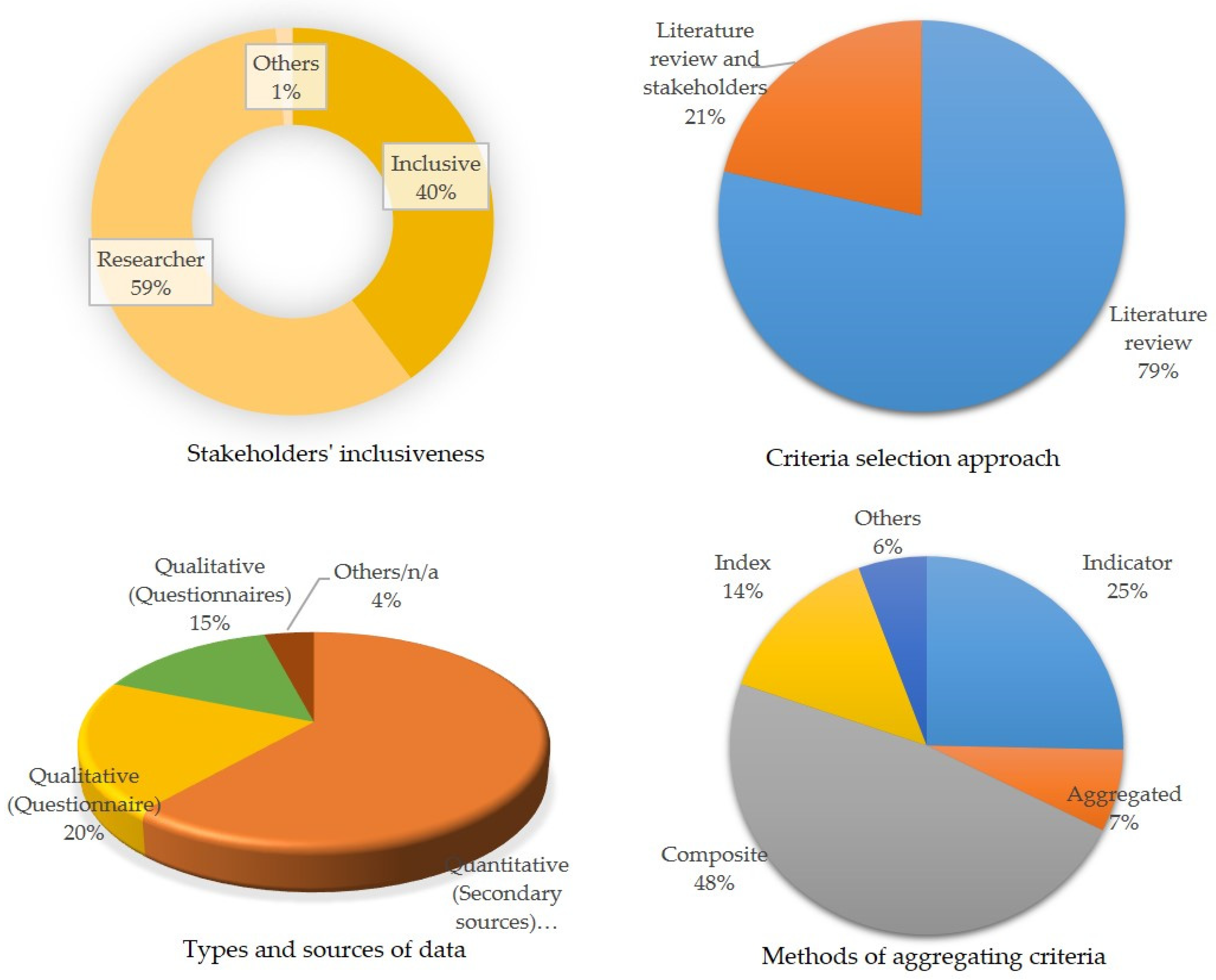

3.3. Decision Implementation (D-I)

Decision implementation covers the methodological aspects of decision evaluation such as stakeholders’ inclusiveness, selection of criteria/indicators, type of data, and methods for aggregating criteria/indicators and models/methods. Energy decisions are multi-stakeholder oriented. On the one hand, there are energy experts, policy makers, regulators and researchers. On the other hand are users, and investors, among others. Effective engagement of these various groups will not only achieve favourable decisions, but also cooperation of various stakeholders during decision implementation. According to

Figure 6, 40.0 per cent of the articles are outcomes of inputs from authors, experts, decision-makers, and other stakeholders, whereas 59.0 per cent do not state whether stakeholders were engaged or not. This does not mean they do not engage a few experts at a particle stage in their undertaking. For example, some are likely to consult relevant bodies of literature for input data. It follows that they indirectly engage other stakeholders in an ‘informal’ manner. One of the functions of a decision lead or analyst is the selection of criteria/indicators and other techniques for measuring the achievement of the objectives of their assessment.

Figure 5 presents how this aim has been achieved in the articles. Many of the studies (79 per cent) relied solely on literature sources, whereas others requested contributions from major stakeholders while criteria were selected and validated. Sharmin & Dhakal (2022) engaged policymakers, academic/researchers, technical experts, and end users, totalling 30 participants during the Delphi survey, while Dashtpeyma & Ghodsi (2021) retrieved the opinions of 30 experts from academia and industry. Other activities requiring the support of stakeholders during decision-making, as found during the review, include actual assessment in the form of a survey (Gholami, 2024; Haro-baez et al., 2025; P. Liu et al., 2024b; Odoi-yorke et al., 2022) or interview (Kazimierczuk et al., 2023; Zaheb et al., 2023).

The types of data observed in the articles (

Figure 6) include quantitative data from secondary sources (61 per cent), and qualitative data from primary sources through survey instruments (20). A combination of the two sources was found in some articles (15). An example is Ref. (Odoi-yorke et al., 2022) where quantitative data on technical, economic, and environmental criteria was used in combination with qualitative data on socio-political criteria through questionnaire distribution. In such situations, data normalization may be required to ensure that the data are in the same unit of measurement for assessment purposes (Pérez-Denicia et al., 2021).

Figure 6 also presents methods for aggregating indicators in the articles. While the table provides insightful findings, grouping articles by methods can be complex, as different authors may understand a given approach in different ways. Thus, by applying the knowledge gained from (Liu, 2014), this review identified fundamental categories of indicators that can be differentiated from the articles by their construction methods and degree of aggregation—indicators, aggregated indicators, index, composite indicators. Composite indicators are the most used accounting for 48.0 per cent of the articles. They involve relatively complex concepts, and the articles in this category sum numerous facets of a given phenomenon into a single number with a common unit. Common areas of application include optimization problems, such as hybrid/decentralized systems aiming for the best combination of criteria and options to achieve a particular objective (Araria et al., 2024; Elkholy, Senjyu, et al., 2024; Gul et al., 2025; Haro-baez et al., 2025). Indicator-based methods accounted for 25 per cent. The method is based on results from the processing and interpretation of primary data. Indices (14.0 per cent) employ a form of dimensionless number that requires the transformation of data in various units for the most part in order to generate a single number. The aggregated indicators (7.0 per cent) combine a number of components (indicators/sub-criteria) of the same units, mostly in an additive aggregation way. When data are not of the same unit, they can be normalized to have a common basis for assessment such as in (Pérez-Denicia et al., 2021). In addition to these, criteria can assume positive or negative value, that are beneficial or non-beneficial for assessment purposes (Evans et al., 2009). This affects the sizes of the weights that criteria assume and invariably affect the valuation of each decision alternative available.

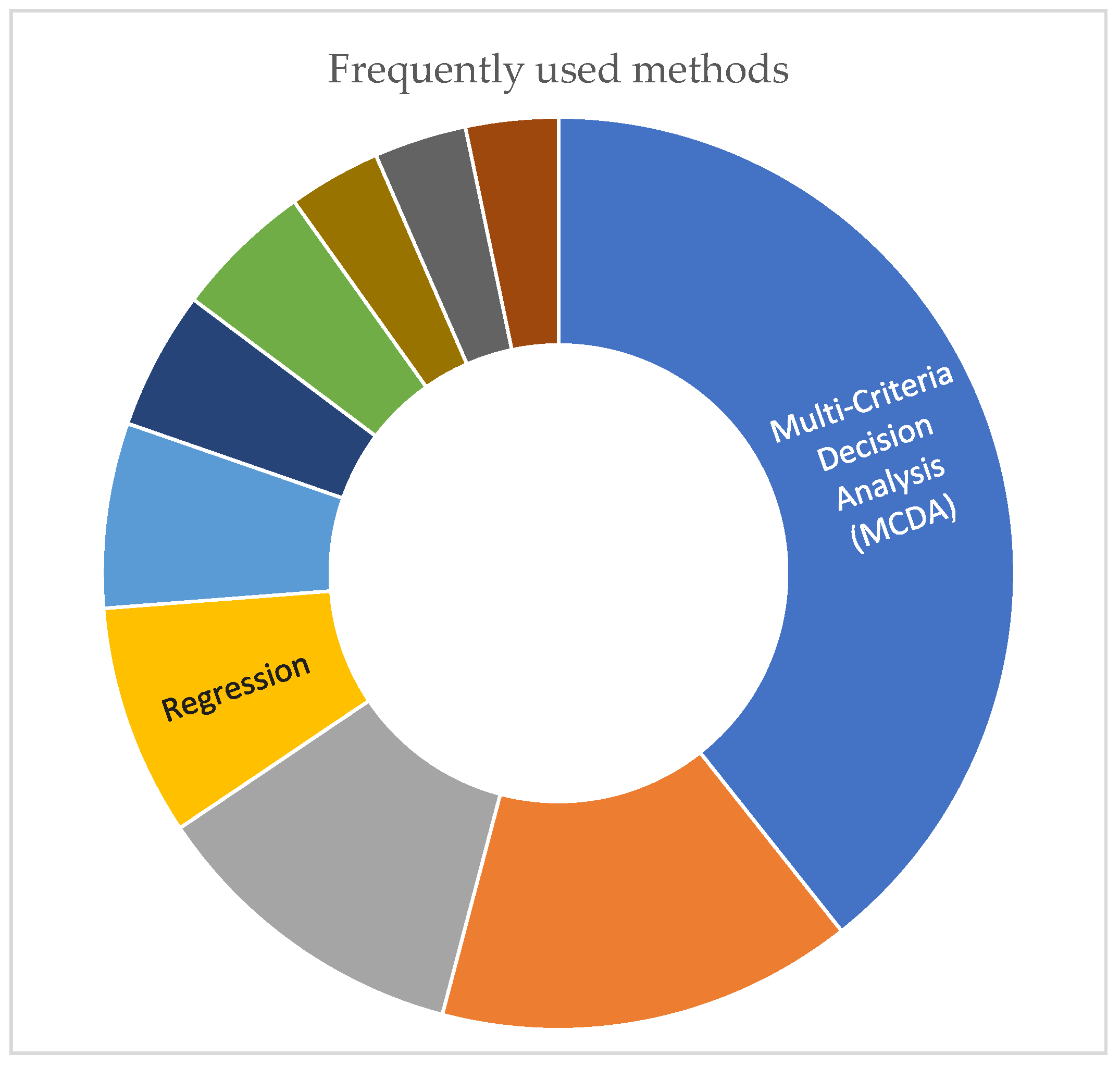

It is important to identify methods for handling energy decision analysis. While most of the articles used at least two methods,

Figure 7 identified 10 categories of methods that featured in at least two articles. Multi-Criteria Decision Analysis (MCDA) (discrete) related methods have been widely used. Other multi-objective techniques (continuous versions of MCDA) identified are Multi-Objective Grey Wolf Optimization (Ala et al., 2023), Multi-Objective Optimization Framework (Jing et al., 2021), Multi-Objective Programming Model (Ala et al., 2023), Multi-Objective Resilience Metric Approach (Yazdanie, 2023). Hybrid Optimization of Multiple Energy Resources (HOMER) is also one of the top three methods identified while Capital Budgeting Model, Descriptive Model (using descriptive statistics), Life Cycle Cost Analysis (LCCA), Regression (such as Quantile regression (Dong et al., 2021)) have been used in two articles each. Other methods are listed in Table S3 (supplementary material).

5. Discussion

This study is a comprehensive perspective on the trends and practices that can enhance the energy sustainability and resilience decisions and analysis. Following the earliest article (Yue et al., 2001), efforts had been made to increase scientific knowledge and practices for achieving these objectives individually or together. The highest trends occurred in 2021, when publications started increasing beyond the previous two decades. Within the period under consideration, terms relating to the objectives have been prominent and supported by terms like renewable, system, optimisation, electric*, and assessment, among others. These positive trends was observed in a recent study on resilience and sustainable goals in global south urban strategies (Kochskämper et al., 2024). Therefore, it is important to discuss practices that can serve as guides in decision-making according to the D-OCI framework explained in section 3.

5.1. Decision Objectives

One of the preliminary steps in the integration of sustainability and resilience is to clarifying the issues relating to goals to be achieved. In the first instance, the energy planners can achieve sustainability and resilience goals at the same time in several ways, which can be categorised into implicit integration, explicit integration, and integration by strategy. Implicit integration supports the existing notion that pursuing either sustainability or resilience can indirectly help one to achieve the other (Marchese et al., 2018). Although the implicit approach was common in the earliest studies, addressing the performance of a specific resilience aspect critical to addressing a specific threat may be difficult. An implied or aggregated performance value will not be adequate in this case. Mujjuni et al. (2021) recommended treating each element of the system affected by a threat as an entity, rather than adopting a ’one-size-fits-all’ approach. Explicit approach could handle this challenge by addressing specific cases and contexts, which are subject to different factors or influences. Consequently, explicit integration has been used increasingly recently. Of the three forms of explicit integration identified in this study, stand-alone integration makes it easier to determine how each energy option achieves individual objectives prior to investment decision and implements initiatives that will improve the aspects that are underperforming during project life. Integration by strategy appears to be more appealing when different strategies that could promote the objectives are optimised to know which combination gives the best results, such as combining different technologies (i.e., generation and storage in a centralised or decentralised system). Most of the studies focused on the environmental, economic, technical and social aspects of sustainability in energy planning. The position of technical factors among the triple bottom line (TBL) is not surprising since energy systems are made up of technical features. Contrary to the assertion that the Triple Bottom Line (TBL) encompasses a broader perspective (Olivier et al., 2021) and includes minor issues like technical and operability others (Akber et al., 2017), there is an increasing focus on technical, technological, and institutional/political sustainability as independent criteria. This corroborates the definition of sustainability as the ability to maintain an entity, outcome, or process over time through mutual relationships (Jenkins, 2009). To maintain a sustainable energy system with minimal disruption, the right political will and institutional framework are needed. Technological sustainability is essential for meeting global dynamics and providing necessary technical support and enabling processes. Thus, a holistic approach to achieving sustainability objectives in a low-carbon economy is nothing short of integrating cross-cutting sustainability concerns into (energy) policy assessment procedures, thereby generating cohesive policy-making, and better governance (Weaver & Jordan, 2008).

The review clearly demonstrates the diversity and distinct focus of resilience decisions. For instance, policymakers and practitioners may need to prioritize threats to the performance of the system. These are human/management, economic, technical/technological, resource, operational, policy, climate or natural, pandemic, demand, and others. While entire energy system is open for energy planning, decisions could be made on energy technology, organization/management systems, micro-grids/power plants or power supply, among others. More so, while energy resilience strategies mostly cater for system adaptation, decision makers have other options like recovery, absorptive, anticipative, transformative, and preventive strategies, which can combined to attain the desired performance level of resilience. The strategies can manifest in various forms, but diversity, flexibility, stability, robustness, reliability, and decentralisation have gained wider usage.

Given the aforementioned parameters, evaluating resilience can be a challenging task. As mentioned earlier, implicit integration of resilience with sustainability may not achieve an effective decision outcome, whereas it may be easier and more productive to aggregate assessment criteria if articulated explicitly, owing to the answer to the question: resilience “of or for what.” Thus, taking a cues from articles on explicit integration, resilience assessment can be attribute-based, such as the diversity index (Jing et al., 2021), and resilience factors (Salehi et al., 2022), or using anchors of resilience as assessment criteria. To evaluate resilience where integration by strategy is involved, sustainability criteria or indicators could be adopted as objectives to optimize (Gruber et al., 2024; Tangi & Amaranto, 2025). From these discussions, it can be found that the connection or differences in the sustainability and resilience depend on how they are integrated. In implicit integration, the focus is either how being sustainable could promote resilience or how being resilient could promote sustainability. In explicit integration, both goals may be pursued independent of each other or by combination of strategies, but collaboratively. Fundamentally, identifying the enabling factors and strategies provides a suitable tool for stakeholders to make better decisions in the energy industry (Dashtpeyma & Ghodsi, 2021) but it is also important to consider the decision context as explained next.

5.2. Decision Context

The decision objective is of little importance without establishing the context of decision agenda. Two main system configurations are currently central to addressing energy challenges: centralised and decentralised systems. There is a strong link between the configuration of the system and the type of integration used, but there is not enough evidence to say whether one configuration performs better than another under a different approach or the other way around. However, reading carefully through articles on integration by strategy does show that decentralised, or off-grid, systems are good for the approach. The type of technology is another contextual issue, ranging from energy generation to storage. This review showed a number of different technology choices, including different mixes of renewable, nonrenewable, and storage technologies to show how an energy system that only uses renewables could be a concern under unfavourable conditions. DMs should evaluate renewable and conventional technologies to determine which best achieves the two objectives or which should be mixed with others. The combination of renewables and cleaner conventional energy sources can serve as alternatives to dirty conventional energy sources (United Nations Economic Commission for Europe [UNECE], 2022). They could address the intermittency challenge with renewable sources that are weather-dependent, such as wind and solar (Schwerhoff & Sy, 2018). Consequently, it is not surprising that articles on hydrogen outnumber those that addressed the renewables except solar and wind. A similar pattern was noticed for storage technologies to validate supporting renewable sources with cleaner non-renewables and storage technology.

Another important decision context parameter is the value chain because the process of meeting the demand and supply of energy involves different value chains such as generation, transmission, storage, distribution and consumption, each of which has its own unique function and factors or threats and should be treated accordingly. Energy is generated through different technologies (sometimes mixtures of different sources) but it must be transmitted to the distribution system using high-voltage lines through the grid. Next, it is delivered to consumers through poles and wires at low voltage (Bamber et al., 2015). Depending on which demand timely intervention, effort could be directed to the entire system or specific value chain, although more than 60.0 per cent of previous studies are based on generation most likely because of the dependence of other value chain on it. Nevertheless, different combinations of value chains from generation, transmission/transportation, storage, distribution, and consumption are also possible, such as in Sharmin and Dhakal (2022) and Pal and Shankar (2023).

Furthermore, DMs need to specify the boundary of the decision. Available options include local/community, national level, and power plant/energy generation/project/specific system scope. Localised/community, national, and urban options are the most studied. Efforts are being undertaken to meet the peculiar geographical location needs of the local community, which make access to energy infrastructure difficult (Ali et al., 2024). National energy mixes are examples for holistic assessment (Dantas & Soares, 2022). The benefits of nation-wide energy decisions include providing top-level strategies that can guide lower levels. An example is the UN’s national commitment to SDG transformation (United Nations, 2023), although developing plans and implementing policies would still require coordinated commitments from national, state, local, and other entities (Oyewunmi, 2021). Furthermore, energy decisions can focus on either current or future systems/technologies or both. Performance evaluation is often required for the current system to improve its future performance, whereas evaluation of new energy investment is future-focused. There is the belief that the outcome of sustainability policy may not be felt in the short run (such as in intergenerational equality), unlike resilience policy, which will secure the system in the short term from potential threats. This is the main difference between the concepts (Aasa et al., 2016; Marchese et al., 2018). The above argument could justify the use of sustainability indicators to assess resilience strategies to establish their long-term relevance. Some of the indicators are service life (Irshad et al., 2023), lifetime costs inside the system (Tayyab et al., 2024), product lifetime analysis (Maaloum et al., 2024), operational lifetime (Li et al., 2024), short-term and long-term perspectives (Shobayo & Dao, 2024), long-term economic and environmental benefits (Hassan et al., 2025) and long-term climate resilience evaluations (He et al., 2025). Nevertheless, both concepts work in tandem to guarantee uninterrupted access to energy.

With respect to the unit of decision, technology-based assessment has gained more popularity than project-based assessment since there is no basis for comparing projects that will always differ in technology, cost, size, etc. (Büyük€ozkan & Karabulut, 2017). Technology-based assessments are useful for comparing or selecting among a number of alternatives/technologies, whereas project assessment seems to be more beneficial to a specific technology to determine feasibility.

5.3. Decision Implementation

As important as clarifying decision objectives and establishing the context, they depend on the synthesis of different considerations through implementation strategy. It was found that energy decisions involve multiple stakeholder. Stakeholders usually participate in the process of aggregating criteria for evaluation, but their inputs are also relevant during data collection. Nevertheless, 79.0 percent of the studies relied on literature sources for criteria selection. Past studies are useful sources for aggregating criteria, if existing criteria can be adapted, but policymakers, academics, technical experts, and end users could add value to the selection of criteria during the scientific validation process, such as in (Grafakos et al., 2017). Moreover, indicators, indices, aggregated indicators, and composite indicators are the metrics for energy assessment based on their aggregation technique. From decision assessment standpoint, the drawback in the use of individual indicators is that it does not give the performance overview as a whole. Consequently, it is difficult to use individual indicators for comparability activity since they are entity centric (OECD, 2010; Abdul Murad et al., 2019). On the other hand, composite indices are extremely useful because information from several aspects is aggregated and simplified enabling easy interpretation although there may be data misinterpretation since each sub-index may have their own scope and limitations (OECD, 2010), and should not have been generalized. The trends in data collection for assessment include quantitative data from secondary sources and qualitative data from primary sources through survey instruments, and in some instances, a combination of the two is necessary. Combining different data sources is essential for easy data collection, availability, and measurability. Transparency in the assessment process is crucial, while involving stakeholders in key stages, such as validation and assessment of criteria, ensures stakeholder engagement. Conceivably, MCDA has gained popularity within the energy planning domain because it allows for a transparent process that engages as many stakeholders as possible. It can have a substantial effect on the effectiveness of the process (Guarini et al., 2018).

Irrefutably, this study indicates the need for a shift from a narrow view of energy planning as a decision that involves static and narrow concepts to an embodiment of—insights from a number of disciplines investigating the factors shaping it (Cherp et al., 2018)—for which sustainability and resilience considerations are inevitable. To apply D-OCI, the decision process should address the question: Decision on what, for which setting, and how? The responses to the questions will include choices among elements of the framework. For example, under D-O, decision-makers can choose whether to integrate sustainability and resilience objectives implicitly or explicitly. Under D-C, decision-makers have the option to tailor integration to either energy generation or any other value chain, which will affect the choice of strategies to increase resilience. Under D-I, the type of data used for decision evaluation can be qualitative or quantitative, depending on the reasons stated in the subsection addressing the data type in section 4. According to

Figure 8, the first step in using the framework is to collect information on the energy decision problem from stakeholders. The information collected is input for establishing the decision objective, as well as contextualizing solutions in stages two and three. The framework may involve going back and forth between stages two and three to make sure that all of their parts are in agreement, especially those that have to do with resilience, before addressing issues related to decision implementation. For instance, the choice of resilience strategy will require DM to know the value chain being addressed. Furthermore, to guarantee effective assessment, criteria must be tailored to specific system configuration and value chains.

6. Conclusions

This review addresses the central question on trends and practices that can enhance the integration of sustainability and resilience objectives for energy decisions. Energy transition involves disruptions in the energy system, in addition to both natural and man-made threats, implying the need for effective strategies to address for these disruptions and holistic sustainability assessment. Research outputs in this area have emerged recently, but more studies are still needed to unravel effective practices within the energy planning field.