Submitted:

18 March 2025

Posted:

19 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Quatum-Chemical Calculations

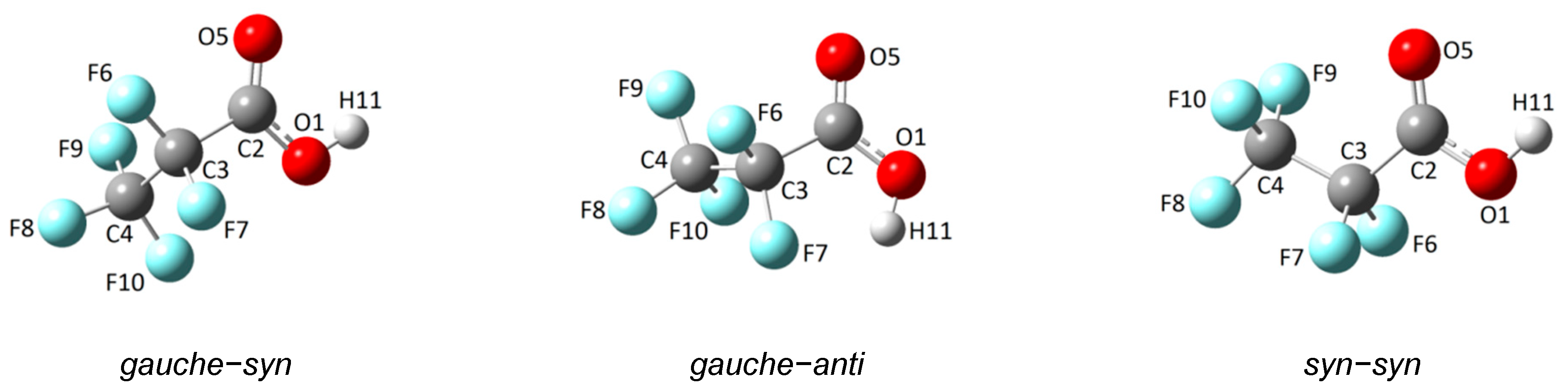

2.1.1. Monomer

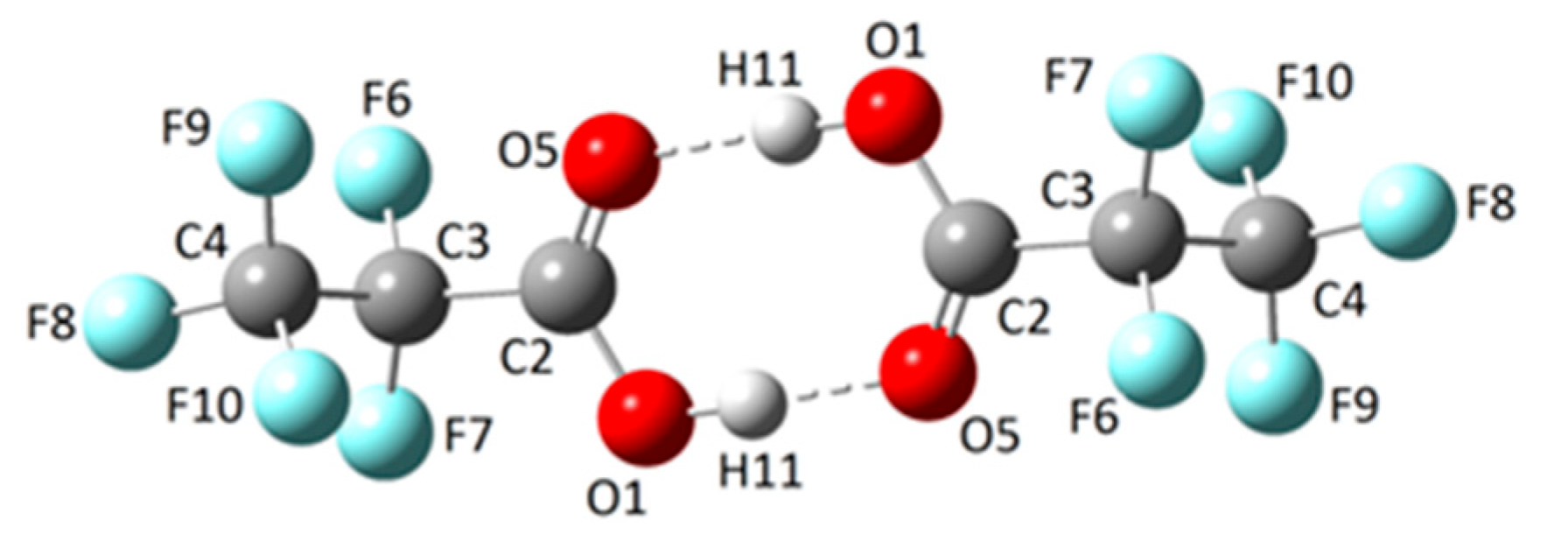

2.1.2. Dimer

2.2. Experimental Results

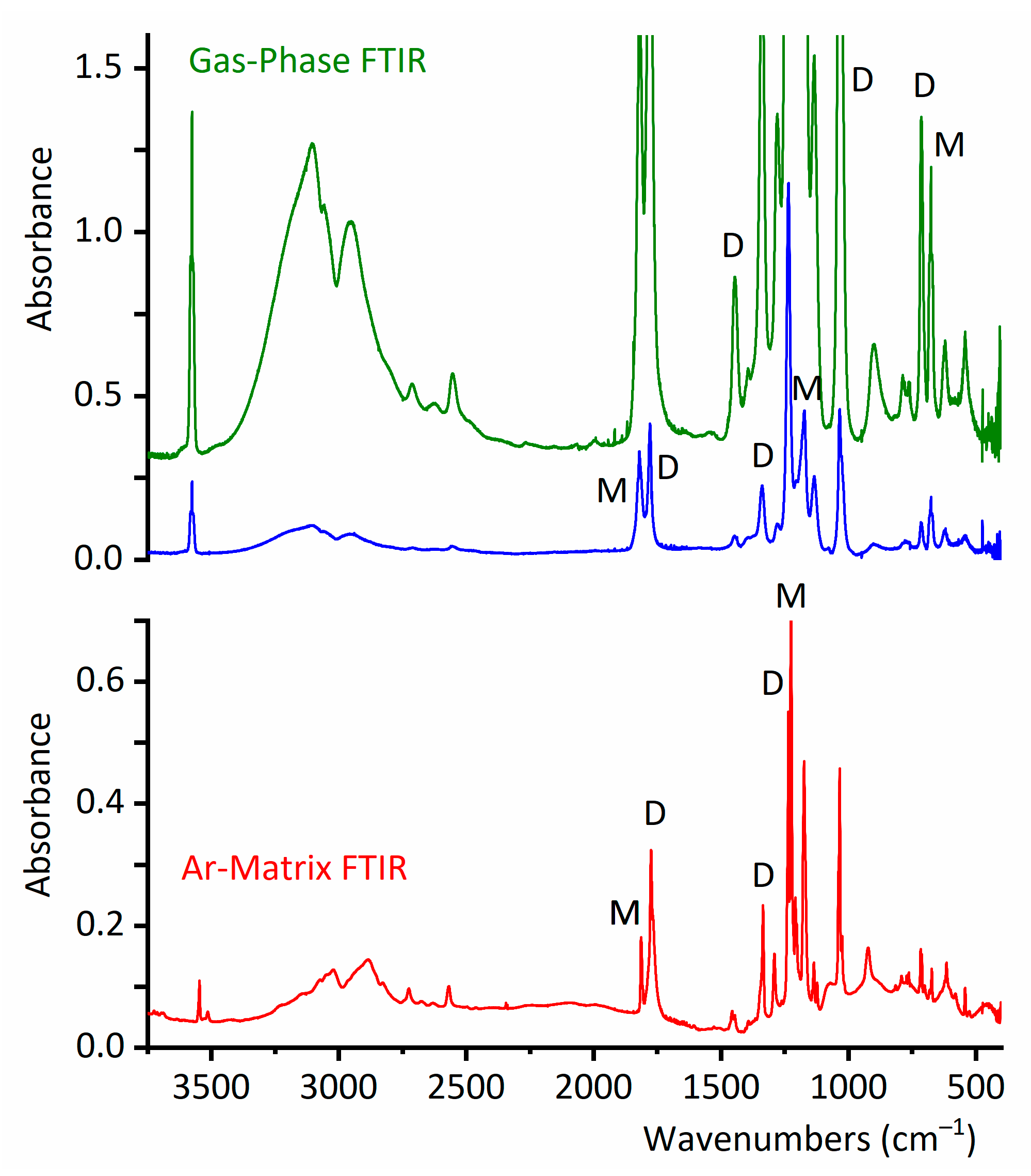

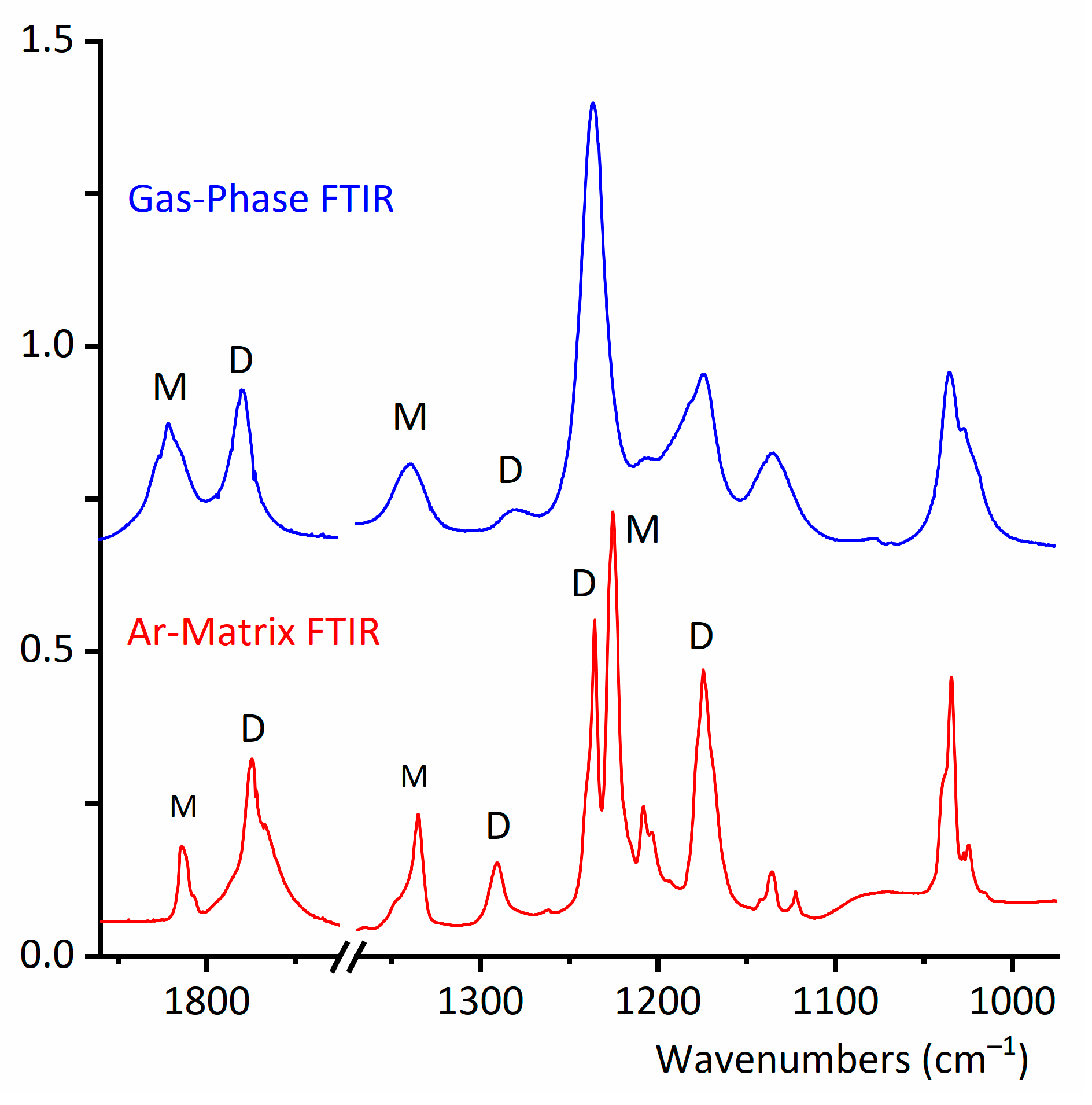

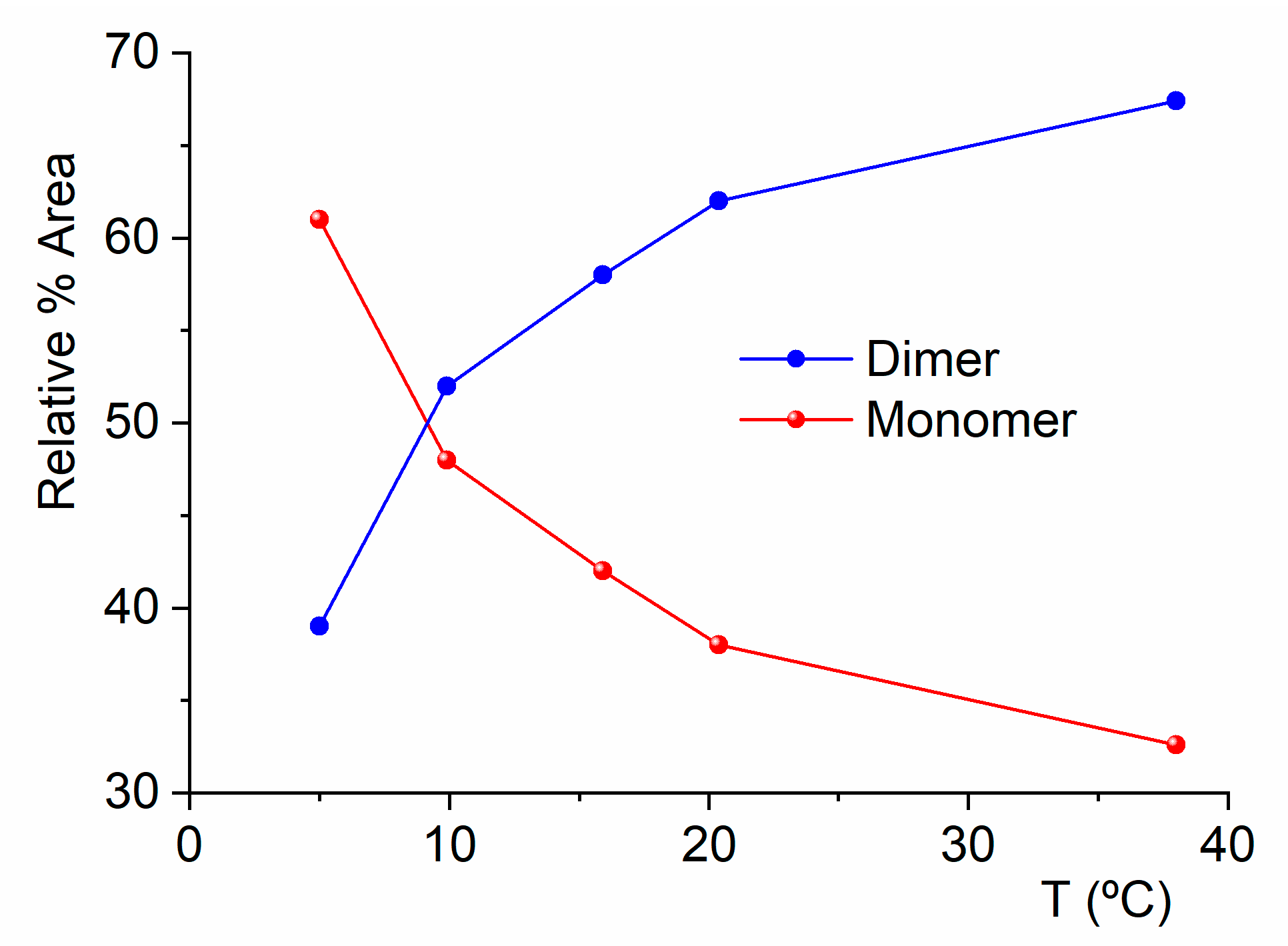

2.2.1. Gas-Phase FTIR Spectra

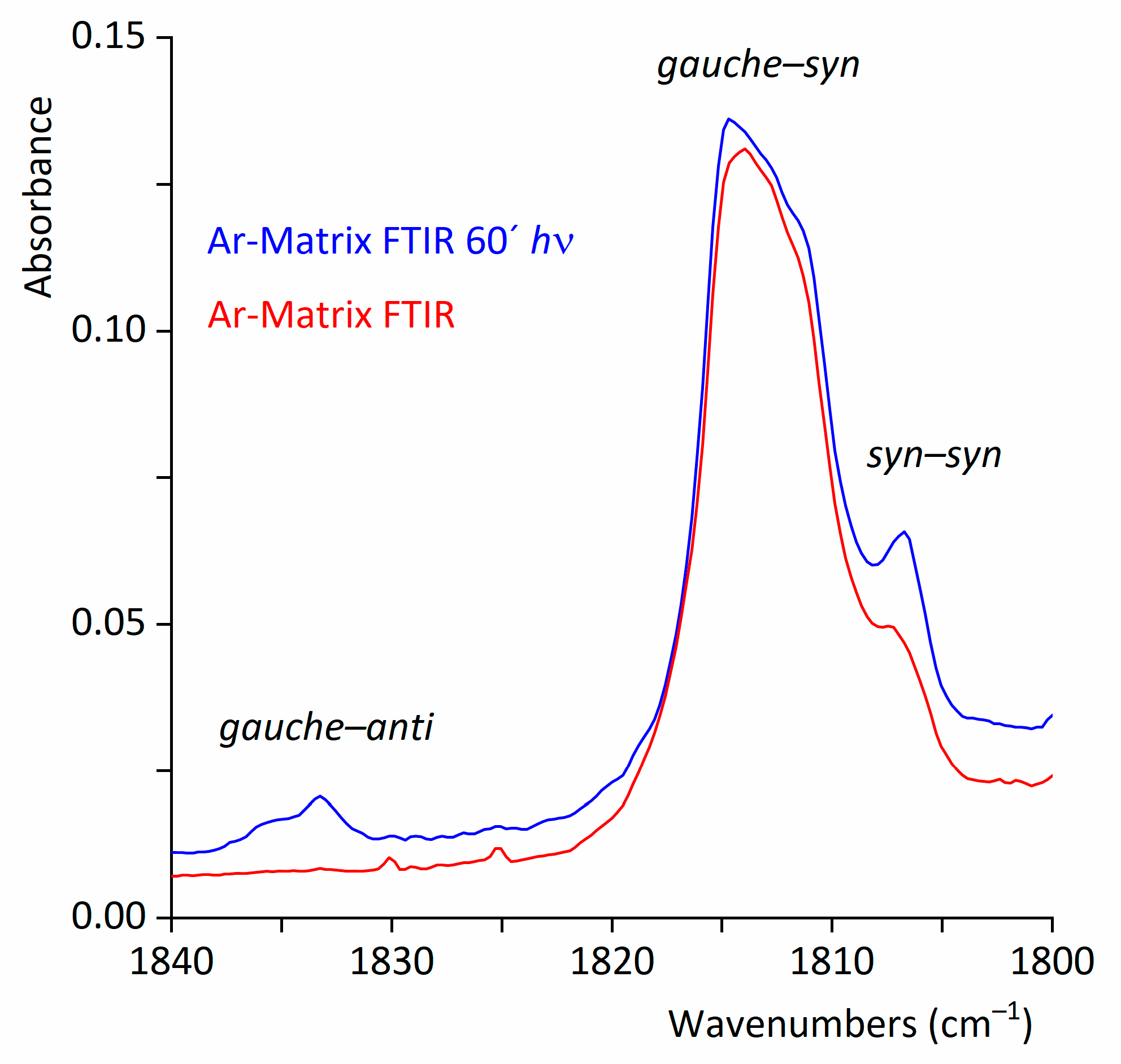

2.2.2. FTIR Spectrum of CF3CF2C(O)OH Isolated in Solid Ar

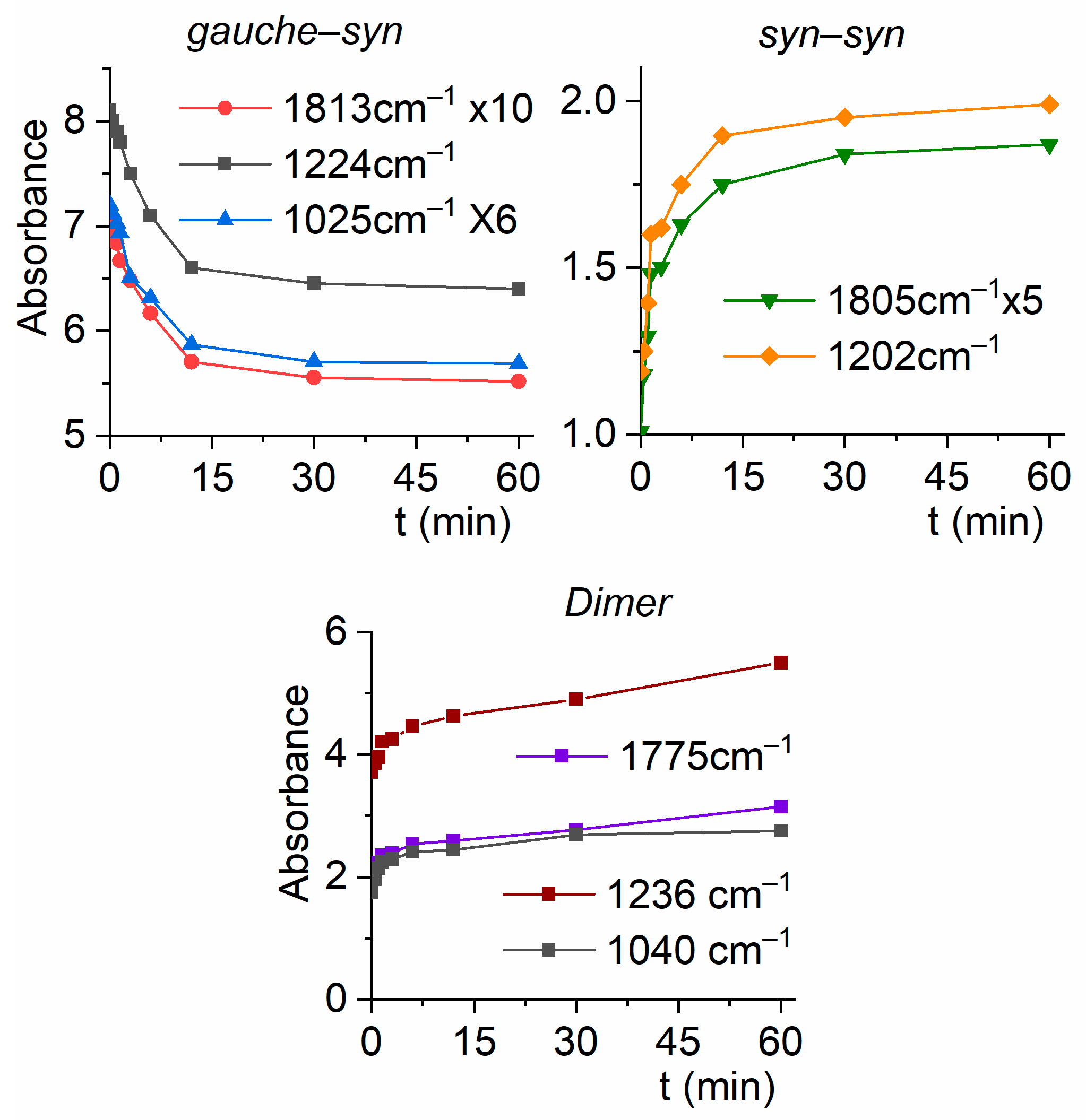

2.2.3. Matrix FTIR Spectra of CF3CF2C(O)OH after Broadband UV-VIS Irradiation

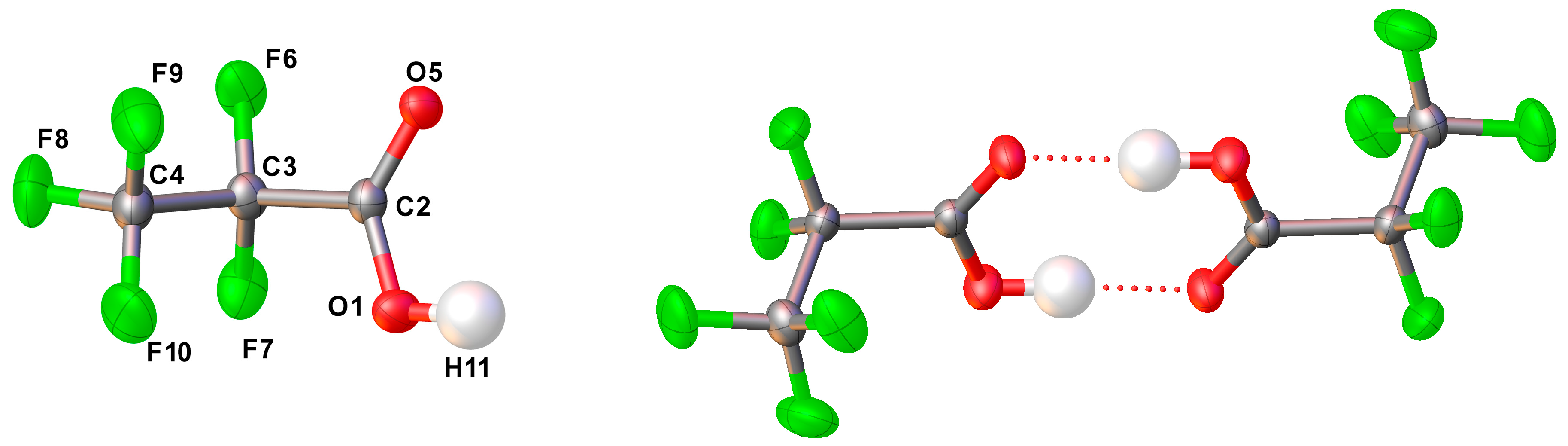

2.2.4. Solid State Structure

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. CF3CF2C(O)OH

3.2. Quantum-Chemical Calculations

3.3. Infrared Spectroscopy

3.4. Matrix Isolation Experiments

3.5. X−Ray Diffraction Analysis

3. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Susarla, N.; Ahmed, S. Estimating cost and energy demand in producing lithium hexafluorophosphate for Li-ion battery electrolyte. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2019, 58, 3754–3766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moody, C.A.; Martin, J.W.; Kwan, W.C.; Muir, D.C.G.; Mabury, S.A. Monitoring perfluorinated surfactants in biota and surface water samples following an accidental release of fire-fighting foam into Etobicoke Creek. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2002, 36, 545−551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Yan, H.; Li, F.; Zhou, Q. Occurrence and fate of perfluorinated acids in two wastewater treatment plants in Shanghai, China. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2015, 22, 1804–1811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamashita, N.; Kannan, K.; Taniyasu, S.; Horii, Y.; Petrick, G.; Gamo, T. A global survey of perfluorinated acids in oceans. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2005, 51, 658–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- So, M.K.; Miyake, Y.; Yeung, W.Y.; Ho, Y.M.; Taniyasu, S.; Rostkowski, P. Perfluorinated compounds in the Pearl River and Yangtze River of China. Chemosphere. 2007, 68, 2085–2095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, D.A.; Mabury, S.A.; Martin, J.W.; Muir, D.C.G. Thermolysis of fluoropolymers as a potential source of halogenated organic acids in the environment. Nature. 2001, 412, 321–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y.; Yao, Y.; Chang, S.; Zhao, Z.; Zhao, Y.Y.; Yuan, X.J.; Wu, F.C.; Sun, H.W. Occurrence and phase distribution of neutral and ionizable per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFASs) in the atmosphere and plant leaves around landfills: A case study in Tianjin, China. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2018, 52, 1301–1310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, J.W.; Mabury, S.A.; Solomon, K.R.; Muir, D.C.G. Dietary accumulation of perfluorinated acids in juvenile rainbow trout (Oncorhynchusmykiss). Environ. Tox. Chem. 2003, 22, 189–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, J.W.; Mabury, S.A.; Solomon, K.R.; Muir, D.C.G. Bioconcentration and tissue distribution of perfluorinated acids in rainbow trout (Oncorhynchusmykiss). Environ. Tox. Chem 2003, 22, 196–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. Preliminary risk assessment of the developmental toxicity associated with exposure to perfluorooctanoic acid and its salts. Office of Pollution Prevention and Toxics, RiskAssessment Division, 2003.

- Berthiaume, J.; Wallace, K.B. Perfluorooctanoate, perflourooctanesulfonate, and N-ethyl perfluorooctanesulfonamido ethanol; peroxisome proliferation and mitochondrial biogenesis. Toxicol. Lett. 2002, 129, 23–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Upham, B.L.; Deocampo, N.D.; Wurl, B.; Trosko, J.E. Inhibition of gap junctional intercellular communication by perfluorinated fatty acids is dependent on the chain length of the fluorinated tail. Int. J. Cancer. 1998, 78, 491–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biegel, L.B.; Hurtt, M.E.; Frame, S.R.; Connor, J. O.; Cook, J.C. Mechanisms of extrahepatic tumor induction by peroxisome proliferators in male CD rats. Toxicol. Sci. 2001, 60, 44−55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, D.A.; Young, C.J.; Hurley, M.D.; Wallington, T.J.; Mabury, S.A. Atmospheric degradation of perfluoro-2-methyl-3-pentanone: Photolysis, hydrolysis and hydration. Environ Sci. Technol. 2011, 45, 8030–8036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, B.F.; Spencer, C.; Mabury, S.A.; Muir, D.C.G. Environ. Poly and perfluorinated carboxylates in North American precipitation. Sci. Technol. 2006, 40, 7167–7174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, C.J.; Hurley, M.l.D.; Wallington, T.J.; Mabury, S.A. Atmospheric chemistry of CF3CF2H and CF3CF2CF2CF2H: Kinetics and products of gas-phase reactions with Cl atoms and OH radicals, infrared spectra, and formation of perfluorocarboxylic acids. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2009, 473, 251–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grubbs, G.S. II; Obenchain, D.A.; Frank, D.S.; Novick, S.E.; Cooke, S.A.; Serrato, A. III; Lin, W. A study of the monohydrate and dihydrate complexes of perfluoropropionic acid using Chirped-Pulse Fourier Transform Microwave (CP-FTMW) spectroscopy. J Phys Chem A. 2015, 119, 10475–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crowder, G.A. Infrared and Raman spectra of pentafluoropropionic acid. J. Fluorine Chem. 1972, 1, 385–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kagarise, R.E. Relation between the electronegativities of adjacent substitutents and the stretching frequency of the carbonyl group, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1955, 77, 1377–1379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statz, G.; Lippert, E. Far infrared spectroscopic studies on carboxylic acid solutions. Ber. Bunsen-Ges 1967, 71, 673–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badawi, H. M.; Al-Khaldi, M. A. A.; Al-Sunaidi, Z. H. A.; Al-Abbad, S. S. A. Conformational properties and vibrational analyses of monomeric pentafluoropropionic acid CF3CF2COOH and pentafluoropropionamide CF3CF2CONH2, Can. J. Anal. Sci. Spectrosc. 2007, 52, 252–269. [Google Scholar]

- Grubbs, G.S. II; Serrato, A. III; Obenchain, Cooke, S.A.; D.A.; Frank, D.S.; Novick, S.E.; Lin W. The rotational spectrum of perfluoropropionic acid. J. Mol. Spectrosc. 2012, 275, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Husted, D.R.; Ahlbrecht, A.H. The chemistry of the perfluoro acids and their derivatives. V. Perfluoropropionic acid. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1953, 75, 1605–1608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, M.F.; Haywood, B.C. Vibration spectra of carboxylic acids by neutron spectroscopy, J. Chem. Phys. 1970, 52, 5740–5745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rontu, N.; Vaida, V. Vibrational spectroscopy of perfluorocarboxylic acids from the infrared to the visible regions, J. Phys. Chem. B 2008, 112, 276–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rontu, N.; Vaida, V. Vibrational spectroscopy of perfluoropropionic acid in the region between 1000 and 11000 cm-1, J. Mol. Spectros. 2006, 237, 19–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, S.; Remucal, C.K. ; We,i H. Common and distinctive Raman spectral features for the identification and differentiation of per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances. ACS EST Water 2025, 5, 300–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, E.; Featherstone, J.; Martens, J.; McMahon, T.B. ; Hopkins; W.S. Fluorinated propionic acids unmasked: Puzzling fragmentation phenomena of the deprotonated species. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2024, 15, 3029–3036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berrueta Martínez, Y.; Bava, Y.B.; Cavasso Filho, R.L.; Erben, M.F.; Romano, R.M.; Della Védova, C.O. Valence and inner electronic excitation, ionization, and fragmentation of perfluoropropionic acid, J. Phys. Chem. A 2018, 122, 9842–9850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Litvanová, K.; Klemetsrud, B.; Xiao, F.; Kubátová, A. Investigation of real-time gaseous thermal decomposition products of representative per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS), J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom. 2025, 36, 108–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiens, J.P. ; Miller; T.H., Ard, S.G.; Viggiano, A.A.; Shuman, N.S. Elementary reactions leading to perfluoroalkyl substance degradation in an Ar+/e− Plasma. J. Phys. Chem. A 2022, 126, 9076–9086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Song, M.; Abusallout, I.; Hanigan, D. Thermal decomposition of two gaseous perfluorocarboxylic acids: Products and mechanisms. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2023, 57, 6179–6187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melin, T.R.L.; Harell, P. ; Ali, B; Loganathan, N.; Wilson A.K. Thermochemistry of per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances. J Comput Chem. 2023, 44, 570–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medeiros F.S., Jr.; Jr. ; Mota C.; Chaudhuri, P. Perfluoropropionic acid-driven nucleation of atmospheric molecules under ambient conditions. J. Phys. Chem. A 2022, 126, 8449–8458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sablinskas, V.; Pucetaite, M.; Ceponkus, J.; Kimtys, L. Structure of propanoic acid dimers as studied by means of MIR and FIR spectroscopy. J. Mol. Struct. 2010, 976, 263–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarez, S. A cartography of the van der Waals territories. Dalton Trans. 2013, 42, 8617–8636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frisch, M.J.; Trucks, G.W.; Schlegel, H.B.; Scuseria, G.E.; Robb, M.A.; Cheeseman, J.R.; Montgomery, J.A. Jr.; Vreven, T.; Kudin, K.N.; Burant, J.C.; Millam, J.M.; Iyengar, S.S.; et al. Gaussian 03, rev C.02; Gaussian, Inc., Wallingford CT, 2004.

- Parr, R.G.; Yang, W. Density-Functional Theory of atoms and molecules; Oxford University Press: USA, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Møller, C.; Plesset, M.S. Note on an approximation treatment for many-electron systems, Phys. Rev. 1934, 46, 618–622. [Google Scholar]

- Foster, J.P; Weinhold, F. Natural hybrid orbitals. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1980, 102, 7211–7218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glendening, E.D.; Badenhoop, J.K.; Reed, A.E.; Carpenter, J.E; . Bohmann, J.A.; Morales, C.M.; Weinhold, F. NBO 5.G, Theoretical Chemistry Institute, University of Wisconsin, Madison, WI 2004.

- Almond, M. J.; Downs, A. J. Spectroscopy of matrix isolated species. Adv. Spectrosc. 1989, 17, 1–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunkin, I.R. Matrix-Isolation Techniques: A Practical Approach; Oxford University Press: New York, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Perutz, R. N.; Turner, J. J. Pulsed matrix isolation. A comparative study. J. Chem. Soc., Faraday Trans. 2. 1973, 69, 452–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolomanov, O.V.; Bourhis, L.J.; Gildea, R.J.; Howard, J.A.K.; Puschmann, H. OLEX2: a complete structure solution, refinement and analysis program. J. Appl. Cryst. 2009, 42, 339–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheldrick, G. M. A short history of SHELX. Acta Cryst. 2008, A64, 112–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bourhis, L.J. , Dolomanov, O.V., Gildea, R.J., Howard, J.A.K., Puschmann, H. The anatomy of a comprehensive constrained, restrained refinement program for the modern computing environment - Olex2 dissected. Acta Crystallogr. 2015, A71, 59–75. [Google Scholar]

- Kleemiss, F. , Dolomanov, O.V., Bodensteiner, M., Peyerimhoff, N., Midgley, L., Bourhis, L.J., Genoni, A., Malaspina, L.A., Jayatilaka, D., Spencer, J.L., White, F., Grundkoetter-Stock, B., Steinhauer, S., Lentz, D., Puschmann, H., Grabowsky, S, Accurate crystal structures and chemical properties from NoSpherA2. Chem. Sci., 2021, 12, 1675–1692. [Google Scholar]

- Hogg, P.J. Trends Biochem Sci. 2003, 28, 210–214.

- Hilal, R.; El-Aaser, A.M. A comparative quantum chemical study of methyl acetate and S-methyl thioacetate Toward an understanding of the biochemical reactivity of esters of coenzyme A. Biophys. Chem. 1985, 2, 145–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, I.T.; Mitchell, E.C.; Webb Hill, A.; Turney, J.M; Rotavera, B.; Schaefer III, H.F. Evaluating the importance of conformers for understanding the vacuum-ultraviolet spectra of oxiranes: Experiment and theory, J. Phys. Chem. A 2024, 128, 10906–10920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Conformer | φ(C−C−C=O) | φ(O−C−O−H) | ΔE (kcal/mol) | ΔG (kcal/mol) | χ (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| gauche−syn | 101.2 | −0.3 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 85.1 |

| syn−syn | −0.1 | 0.0 | 0.43 | 0.62 | 14.7 |

| gauche−anti | 82.3 | 176.6 | 3.37 | 3.64 | 0.2 |

| Parameter | X-ray diffraction | MP2/6-311+G(D) |

|---|---|---|

| r F6−C3 | 1.338(2) | 1.344 |

| r F7−C3 | 1.336(2) | 1.351 |

| r F9−C4 | 1.319(2) | 1.336 |

| r F8−C4 | 1.317(2) | 1.330 |

| r F10−C4 | 1.304(2) | 1.332 |

| r O5=C2 | 1.215(2) | 1.203 |

| r O1−H11 | 0.97(3) | 0.971 |

| r O1−C2 | 1.286(2) | 1.337 |

| r C2−C3 | 1.545(2) | 1.542 |

| r C4−C3 | 1.542(2) | 1.542 |

| α H11−O1−C2 | 112.6(17) | 108.3 |

| α O5−C2−O1 | 127.9(2) | 126.9 |

| α O5−C2−C3 | 120.0(2) | 123.0 |

| α O1−C2−C3 | 112.0(2) | 110.0 |

| α F9−C4−F8 | 108.9(2) | 109.0 |

| α F9−C4−F10 | 108.8(2) | 108.8 |

| α F9−C4−C3 | 109.4(2) | 109.4 |

| α F8−C4−F10 | 109.1(2) | 108.9 |

| α F8−C4−C3 | 110.1(2) | 110.1 |

| α F10−C4−C3 | 110.6(2) | 110.5 |

| α F6−C3−C7 | 108.7(2) | 108.9 |

| α F6−C3−C2 | 109.0(2) | 108.8 |

| α F6−C3−C4 | 108.1(2) | 107.7 |

| α F7−C3−C2 | 110.5(2) | 110.6 |

| α F7−C3−C4 | 107.9(2) | 108.0 |

| α C2−C3−C4 | 112.6(2) | 112.8 |

| τ H11−O1−C2−O5 | −0.5(18) | −0.3 |

| τ H11−O1−C2−C3 | −178.2(17) | 178.8 |

| τ O5−C2−C3−F6 | 21.2(2) | −18.2 |

| τ O5−C2−C3−F7 | 140.6(2) | −137.8 |

| τ O5−C2−C3−C4 | −98.7(2) | 101.2 |

| τ O1−C2−C3−F6 | −160.9(2) | 162.6 |

| τ O1−C2−C3−F7 | −41.5(2) | 43.1 |

| τ O1−C2−C3−C4 | 79.2(2) | −78.0 |

| τ F9−C4−C3−F6 | −65.5(2) | 65.1 |

| τ F9−C4−C3−F7 | 177.2(2) | −177.4 |

| τ F9−C4−C3−C2 | 54.9(2) | −54.9 |

| τ F8−C4−C3−F6 | 54.1(2) | −54.7 |

| τ F8−C4−C3−F7 | −63.3(2) | 62.8 |

| τ F8−C4−C3−C2 | 174.5(2) | −174.7 |

| τ F10−C4−C3−F6 | 174.7(2) | −175.0 |

| τ F10−C4−C3−F7 | 57.3(2) | −57.6 |

| F10−C4−C3−C2 | −64.9(2) | 65.0 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).