1. Introduction

T follicular helper (Tfh) cells stand as a specialized subset of CD4⁺ lymphocytes and their main role is to initiate and regulate B cell responses [

1]. They serve as the connecting link between cellular and humoral immunity. Based on their ability to interact and activate B lymphocytes, Tfh cells have emerged as critical regulators of humoral immunity, supporting B cell differentiation and antibody production [

2]. These interactions between Tfh and B lymphocytes take place within the

germinal centers (GC) of secondary lymphoid organs, such as spleen and lymph nodes [

3].

Therefore, Tfh cells are essential for the formation and maintenance of

GC, where they assist B cells undergo processes such as affinity maturation and class switching to produce high-affinity antibodies [

4].

However, while Tfh cells are vital for protective immune responses, their dysregulation can lead to the production of autoreactive antibodies, driving the pathogenesis of autoimmune diseases. In this review, we will analyze their functions in normal conditions and explore critical changes in their behavior in autoimmune diseases, with a focus on SLE, RA, and AAV, their contribution to, and the emerging insights into ANCA-associated vasculitis (AAV). We will also discuss potential therapeutic strategies aimed at targeting Tfh cells or their key signaling pathways [

1,

4,

5].

One of the central players in this finely tuned process is the Tfh cells, which represent a specialized subset of CD4+ T cells that closely interact with B cells to promote the production of high-affinity antibodies [

4,

5]. Tfh cells are essential for the formation and maintenance of

GC, the specialized microenvironment sites within lymphoid organs, where B lymphocytes undergo a process called somatic hypermutation and class switching, ensuring the production of a diverse array of antibodies that can effectively neutralize pathogens in certain types of immune responses [

6].

However, Tfh cells are not only essential to initiate B lymphocyte activation, but also, to effectively maintain immune homeostasis, by guiding B cell response in the production of high-affinity, class-switched antibodies against pathogens only, and prevent them from excessive autoimmune responses [

7].

Nevertheless, in the context of autoimmune diseases, this delicate balance in autoimmune reactions, and the competition between defensive and destructive responses is often disrupted, almost always leading to the excessive B cell activation. Tfh cells seem to play central role in these mechanisms of unbalanced reactions [

8]. Deregulated Tfh cell activity can lead to the production of autoantibodies, chronic inflammation and tissue damage. There are several findings of Tfh cell implication and involvement in the pathogenesis of certain autoimmune diseases, including systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), Rheumatoid arthritis (RA), and anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody-associated vasculitis (AAV), not only by up regulating the production of harmful autoantibodies, but also, by preserving the inflammatory and autoimmune cascades [

9,

10]. Understanding the mechanisms by which Tfh cells contribute to the pathophysiology of these diseases is crucial in their abrupt intervention and long term management. By investigating their complicated and multifaceted mechanisms, researchers intent to identify new therapeutic approach which aim to regulate and possibly restrain Tfh cell function, without compromising the body's ability to mount normal immune responses.

The present review describes the function of Tfh cells, their important role in maintaining adaptive immune system activity, but also their detrimental role in certain autoimmune systemic diseases. Although a variety of studies have been conducted investigating the role of Tfh cells in SLE and RA, this review is an aim to reveal the gap in the literature regarding the role of such subpopulations in the pathogenesis of AAV vasculitis and also the need for conducting similar studies.

2. Phenotypic Characteristics of Tfh Cells

The main characteristic which distinguishes Tfh cells from other CD4+ subpopulations is their unique transcriptional program and their ability to interact with B cells in the context of

GC. Differentiation of Naïve CD4 lymphocytes to Tfh cells is driven by the transcription factor Bcl-6, which represses the gene programs of other T helper (Th) cell subsets and promotes the expression of key molecules, including CXCR5, ICOS**, and PD-1, essential to define the Tfh phenotype [

11].

Tfh cells exhibit phenotypic diversity, often classified into Tfh1, Tfh2, and Tfh17 subtypes, each associated with specific cytokine profiles and immune responses [

1,

10,

12,

13].

Tfh1 Cells are characterized by the production of IFN-γ. Tfh1 cells are involved in pro-inflammatory responses and implicated in supporting IgG1 and IgG3 isotype switching in B cells. This subtype is often upregulated in autoimmune diseases, such as RA, where IFN-γ-driven inflammation exacerbates joint damage [

10,

12,

13].

Tfh2 Cells produce IL-4 and are linked to IgE and IgG4 class switching, playing a role in allergic responses and some autoimmune diseases. IL-4 from Tfh2 cells supports humoral responses while limiting excessive inflammation, making them potentially protective in certain contexts [

14].

Tfh17 Cells are defined by IL-17A production, Tfh17 cells are associated with inflammatory autoimmune diseases such as Multiple Sclerosis (MS) and RA. IL-17A enhances neutrophil recruitment, furthering tissue damage in autoimmune settings. Studies suggest that Tfh17 cells may contribute to AAV pathogenesis, where IL-17-driven inflammation underlies vascular injury [

12,

13]. The introduction of Tfh cell subtypes, including Tfh1, Tfh2, and Tfh17, directed researchers to a dedicated view of Tfh cell functions in health and disease. Each phenotype produces unique cytokine profiles that contribute to different immune pathways, with implications for autoimmunity and targeted treatment. For instance, Tfh1 cells, which produce IFN-γ, are often associated with heightened inflammation in RA, while Tfh17 cells, which produce IL-17, contribute to tissue inflammation in multiple sclerosis and potentially AAV. These phenotypes reflect the adaptability of Tfh cells in response to environmental signals, offering pathways to develop phenotype-specific therapies for autoimmune diseases [

15]. By selectively modulating Tfh1, Tfh2, or Tfh17 cells, it may be possible to target specific aspects of immune dysregulation without compromising broader immune functions.

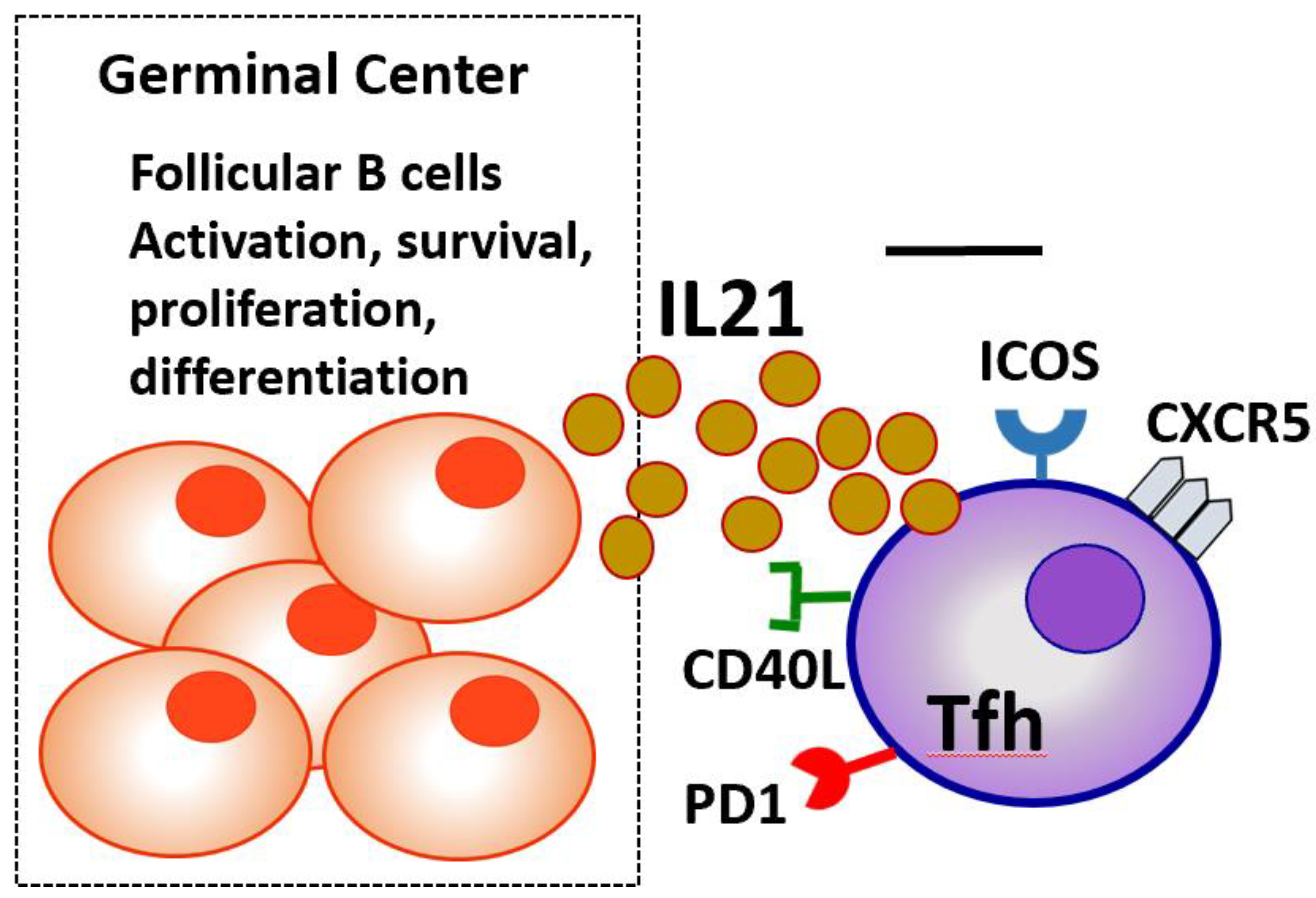

2.1. Key Markers and Signaling Pathways

Expression of certain surface molecules that characterize Tfh cells are: CXC chemokine receptor type 5 (CXCR5) is a chemokine receptor expressed on Tfh cells, that allows their migration to B cell follicle regions and

GCs of secondary lymphoid organs. CXCR5 molecule is the main receptor that determines Tfh certain role in B cell activation, through binding to CXCL13 molecule, a chemokine highly expressed on B follicular cells [

16]. Inducible T cell Costimulator (ICOS) is crucial for the initiation of Tfh cell differentiation and their continued activation of B cells. ICOS acts as a co-stimulatory molecule as it supports interaction between T and B lymphocytes, promotes cytokine production, and enhances the survival and proliferation of both cell types [

17]. Programmed Death-1 (PD-1) serves as a regulatory molecule, controlling the magnitude of the Tfh cell response, by preventing overactivation and maintaining immune homeostasis. Elevated PD-1 expression is a marker of fully differentiated Tfh cells within

GCs. CD40 ligand (CD40L) on their surface, which binds to CD40 on B lymphocytes, an interaction which apart from B cell activation, drives to B cell differentiation into memory B cells and plasma cells [

18]. Signaling Lymphocyte Activation Molecule (SLAM) (CD150) is a receptor that helps interactions between Tfh and B cells. Tfh cells are characterized by downregulation of the CCR7 surface molecule expression. Low CCR7 expression allows Tfh cells to travel from the T cell zones into the B cell follicles of lymphoid organs where they can exert their function [

19] as shown in

Figure 1.

Structure of the B-Cell Follicle and Germinal Center

The B-cell follicle is a specialized region within secondary lymphoid organs (such as lymph nodes and the spleen) where B cells reside and respond to antigens. Within these follicles, a

GC can form during an immune response [

19]. The

GC is crucial for antibody affinity maturation and the differentiation of B cells into long-lived plasma cells and memory B cells. The

GC consists of two main compartments. The Dark Zone which contains rapidly proliferating B cells known as centroblasts, specifil cells undergoing somatic hypermutation (SHM) in their immunoglobulin (Ig) genes to improve antigen-binding affinity and the Light Zone which Contains smaller, less proliferative B cells called centrocytes. These cells express mutated B-cell receptors (BCRs) and interact with follicular dendritic cells (FDCs), which present antigens. T follicular helper (Tfh) cells provide crucial survival and differentiation signals via CD40L and cytokines like IL-21. B cells with high-affinity BCRs are positively selected for further differentiation [

20].

3. Cytokine Production

Certain cytokines are produced by Tfh cells and seem to play crucial role in their stimulating effect on B lymphocytes in

GCs. IL-21 cytokine is produced by Tfh cells and is the cytokine playing a central role in B cell proliferation and survival, while it promotes their clonal expansion and differentiation into plasma cells and memory B cells. IL-21 not only acts on B cells but also supports the survival and expansion of Tfh cells themselves, creating a positive feedback loop [

21]. IL-4 cytokine supports the class switching of B cells to immunoglobulin E (IgE) and IgG1 production. IL-10 production is produced is less prominent cytokine produced by Tfh cells and exerts a rather anti-inflammatory role [

22].

4. Regulation of Tfh Cells

Tfh cell differentiation and function are tightly regulated by a combination of intrinsic transcriptional programs and extrinsic signaling pathways from the microenvironment. Bcl-6 is the master regulator of Tfh cell fate. It acts through upregulation of CXCR5, ICOS, and PD-1, and repression of transcription factors that promote Th1, Th2 and Th17 differentiation (23). Several other transcription factors, such as Achaete-scute homolog 2 (Ascl2), Signal transducers and activators of transcription 1-5 (STAT1-5) and c-Musculoaponeurotic-fibrosarcoma (c-Maf), c-Musculoaponeurotic-fibrosarcoma (Blimp1), Activating transcription factor 3 (ATF-3), Basic leucine zipper transcription factor (Batf), Interferon regulatory factor (IRF) 4 and 8, T-box expressed in T cells (T-bet), T cell-specific transcription factor 1 (TCF-1), Lymphoid enhancer binding factor 1 (LEF-1) also contribute to Tfh cell development and differentiation, while BTB and CNC homolog 2 (Bach2), Forkhead-box protein O1 (FOXO1), Forkhead-box protein P1 (FOXP1), Krüppel-like factor 2 (KLF2) inhibit their differentiation through downregulation of Bcl6 expression and the production of IL-21 [

22,

23,

24].

The interplay between these factors ensures that Tfh cells differentiate appropriately and function within the constraints of the immune response. Ascl2 is the transcription factor which is mainly responsible for the Tfh cells into B lymphocyte follicles, as they act in early stages of Tfh cell differentiation, by upregulation of CXCR5 and repression of CCR receptor expression. Furthermore, reduced Blimp-1 expression, a molecule which antagonizes Bcl-6, prevents from Tfh cell inactivation [

25].

Regulatory mechanisms, including PD-1 and T follicular regulatory (Tfr) cells, help to limit the activity of Tfh cells, preventing excessive or autoreactive responses [

26]. Tfr cells are a subset of regulatory T cells (Tregs) that express both CXCR5 and Bcl-6, allowing them to migrate to the

GC and suppress Tfh-B cell interactions [

27]. Dysregulation of these pathways can lead to unchecked Tfh cell activity, contributing to autoantibody production and autoimmunity.

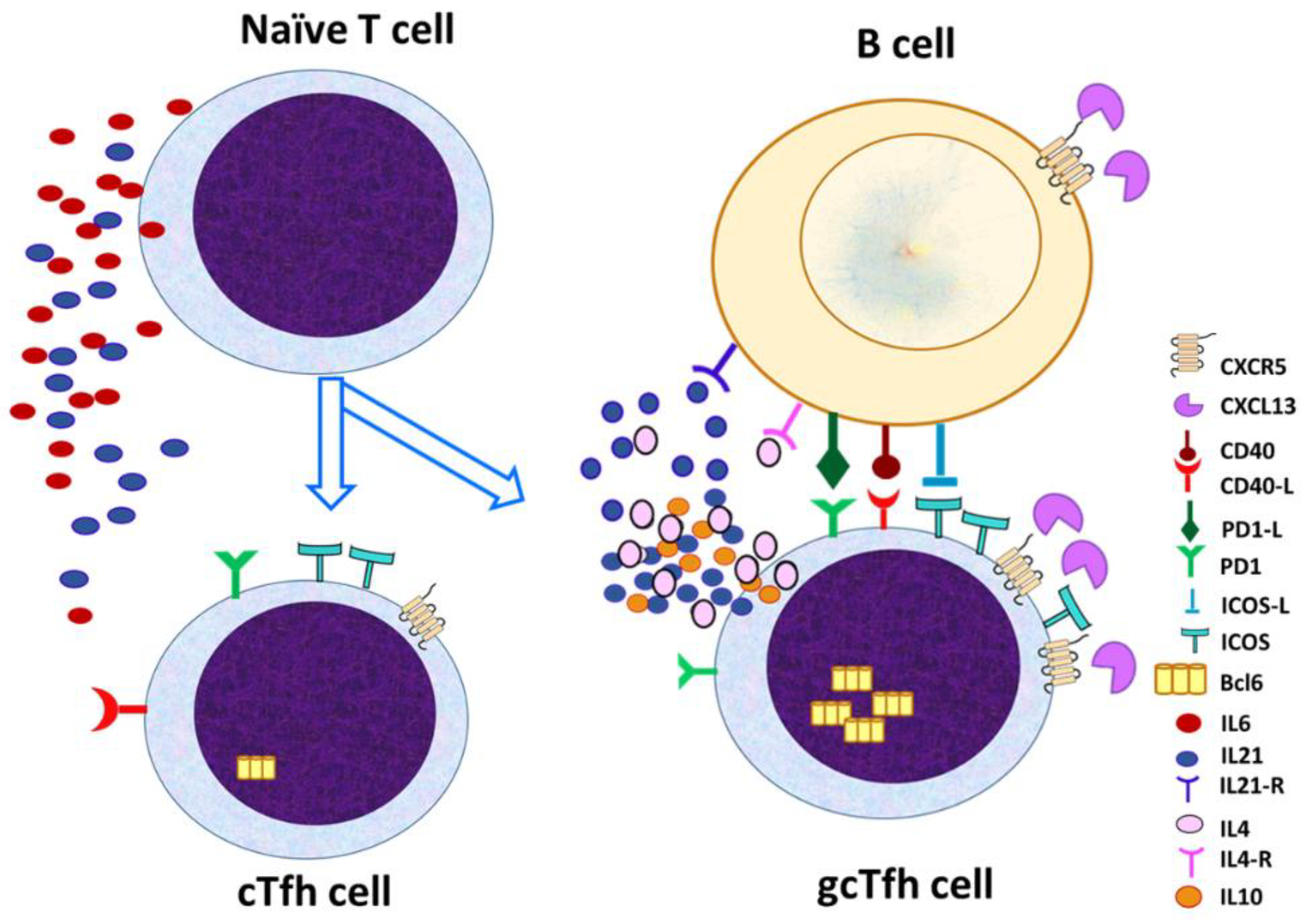

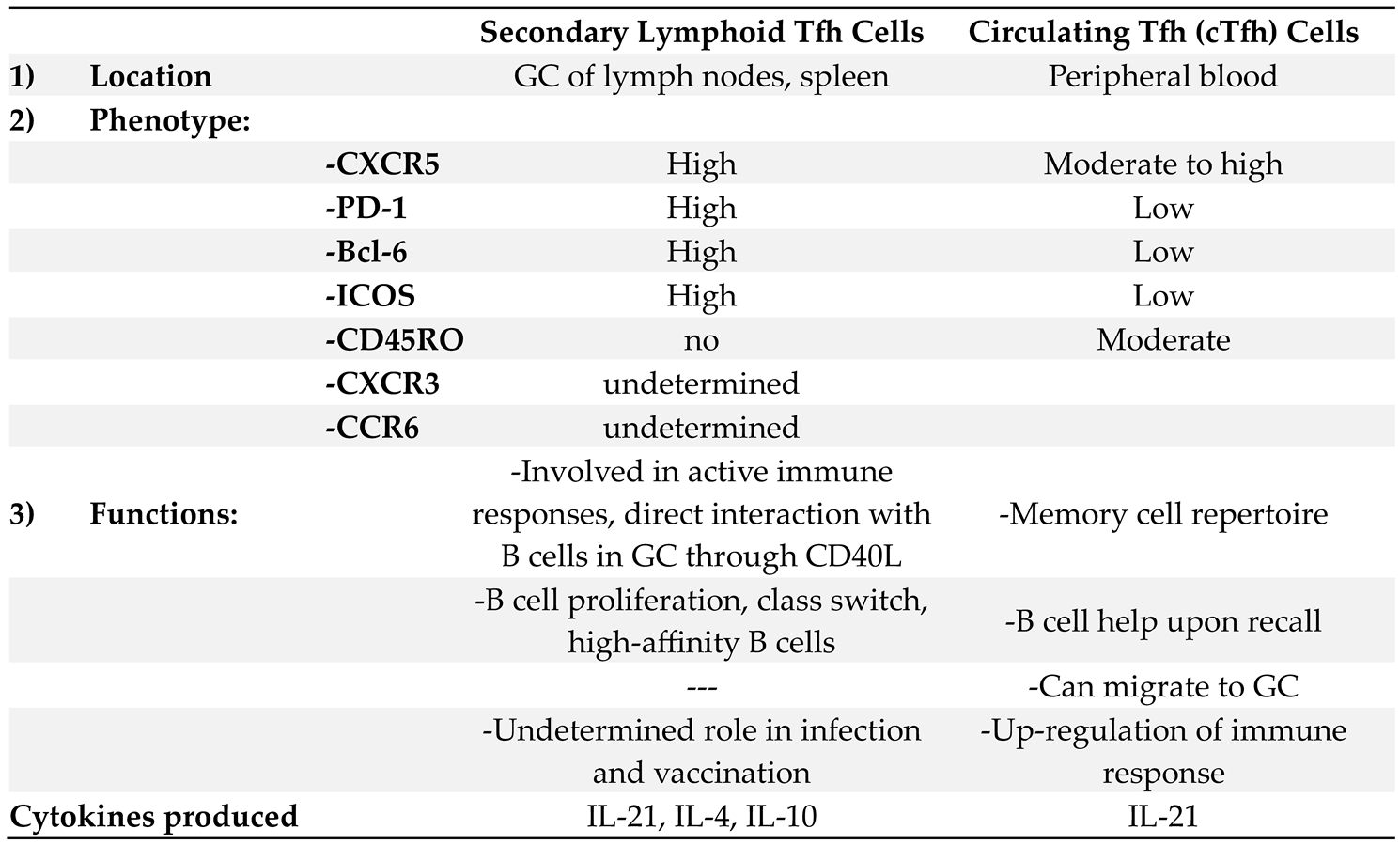

5. Differences Between Tfh Cells in GCs and Tfh Cells in the Peripheral Circulation

While the main place of location for Tfh cells is the B cell follicles and GC within the secondary lymph nodes (gcTfh), Tfh cells are also found in the peripheral circulation, characterized as cTfh [

28,

29] the two populations are not identical, they are similar but still exhibit distinctive phenotypic and functional characteristics (

Figure 2).

The two populations exhibit distinct phenotypic and functional characteristics as shown in

Table 1. Phenotypic differences include increased expression of CXCR5, PD-1, Bcl-6 and ICOS in the Tfh within the

GC, while the peripheral Tfh cell may co-express other markers, such as CD45RO, which indicates their increased memory activity [

28,

29,

30].

6. Tfh Cells in Autoimmune Diseases

Tfh cells are instrumental in regulating B-cell responses within GCs of secondary lymphoid organs. They support B-cell maturation, somatic hypermutation, and isotype switching, processes essential for generating high-affinity antibodies. However, when dysregulated, Tfh cells can drive the production of autoantibodies, fueling the progression of autoimmune diseases. In systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), rheumatoid arthritis (RA), and ANCA-associated vasculitis (AAV), aberrant Tfh cell activity contributes to immune dysregulation and disease pathology [

31,

32,

33].

6.1. Tfh Cells in Systemic Lupus Erythematosus (SLE) Pathogenesis

SLE is a complex autoimmune disease that affects multiple organs and is characterized by a wide range of autoantibodies, antinuclear, anti-dsDNA, antiRNP, anti-Sm antibodies. Production of theses autoantibodies in SLE patients is the direct consequence of the disrupted balance in Tfh-B cell interactions within GCs and in circulation [

31].

The levels of Tfh cells are increased in SLE patients, both within GCs and circulation, and play a central role in SLE pathogenesis. The dysregulation of Tfh cells has been closely associated with the development and progression of SLE. Several studies have reported an increased frequency of Tfh cells in the peripheral blood and lymphoid tissues of SLE patients, correlating with disease activity and autoantibody production. Recent studies have demonstrated that SLE patients exhibit a higher frequency of circulating Tfh (cTfh) cells compared to healthy controls. This elevation is often associated with increased disease activity, as measured by the SLE Disease Activity Index (SLEDAI). For instance, a study [

34] reported that the frequency of cTfh cells was significantly elevated in active SLE patients and positively correlated with serum anti-double-stranded DNA (anti-dsDNA) antibody levels and SLEDAI scores. In addition to quantitative changes, qualitative alterations in Tfh cells have been observed in SLE. Specifically, an increased proportion of Tfh cells expressing inducible costimulator (ICOS) and programmed cell death protein 1 (PD-1) has been reported, indicating an activated phenotype. These activated Tfh cells are more efficient in providing B-cell help, potentially leading to enhanced autoantibody production [

34,

35].

Tfh cells from SLE patients often exhibit altered cytokine profiles, particularly increased production of IL-21. IL-21 is a potent stimulator of B-cell differentiation into plasma cells and promotes class-switch recombination, processes that are dysregulated in SLE. Elevated serum IL-21 levels have been observed in SLE patients and are associated with higher disease activity and autoantibody titers. Other studies also demonstrated that blocking IL-21 signaling in a murine model of SLE resulted in reduced autoantibody production and amelioration of disease symptoms, highlighting the pathogenic role of IL-21 in SLE [

36].

Several molecular pathways have been implicated in the aberrant expansion and function of Tfh cells in SLE. In SLE, dysregulation of Bcl-6 expression has been observed, contributing to the abnormal expansion of Tfh cells. Moreover, other transcription factors, such as T-bet and STAT3, have been implicated in modulating Tfh cell responses in SLE. For example, increased STAT3 activation has been reported in Tfh cells from SLE patients, promoting their differentiation and function [

37]. Other studies also showed that inhibiting STAT3 signaling reduced Tfh cell numbers and autoantibody production in an SLE mouse model [

38].

Epigenetic changes, including DNA methylation and histone modifications, have been linked to Tfh cell dysregulation in SLE. Hypomethylation of the IL21 gene promoter has been observed in Tfh cells from SLE patients, leading to increased IL-21 production [

39,

40,

41,

42]. Additionally, altered histone acetylation patterns have been reported in genes associated with Tfh cell function, suggesting that epigenetic therapies could be potential strategies for modulating Tfh cell responses in SLE [

39,

40,

41,

42].

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are small non-coding RNAs that regulate gene expression post-transcriptionally. Dysregulation of specific miRNAs has been implicated in Tfh cell abnormalities in SLE. For instance, reduced expression of miR-146a, a negative regulator of Tfh cell differentiation, has been observed in SLE patients, leading to increased Tfh cell numbers and activity. Restoring miR-146a levels in a lupus mouse model resulted in decreased Tfh cell responses and amelioration of disease symptoms [

40].

The interaction between Tfh cells and B cells is central to the pathogenesis of SLE. Aberrant Tfh-B cell interactions contribute to the breakdown of B-cell tolerance and the production of pathogenic autoantibodies. In SLE, dysregulated Tfh cell activity leads to the formation of hyperactive GCs, resulting in the generation of autoreactive B cells.

Although the role of both cTfh and gcTfh in the pathogenesis, progression and sustained activity of SLE is indisputable, the distinct effects of cTfh cells subpopulations, cTfh1, cTfh2, and cTfh17, are still under investigation, and seem to be complicated, as various studies have demonstrated controversial results [

40,

41,

42,

43,

44,

45,

46,

47]. Novel SLE treatment strategies have just been released, trying to focus in the deactivation and reduction of Tfh cells. Most in vitro experiments and in vivo studies tried to blockade IL-21 cytokine. The initial in vivo study which targeted IL21 cytokine in a lupus-prone MRL-Fas(lpr) mouse model, was more than 15 years ago, when even the production of IL-21 from Tfh cells was not elucidated. Mice showed an alleviation of skin lesions and lymphadenopathy, reduction in circulating dsDNA autoantibodies, IgG1 and IgG2a and urine protein levels, and improved histology after 10weeks treatment with IL-21R.Fc fusion protein. The same study also revealed that IL21 blockade also reduced splenic T lymphocytes and reduced pathogenic autoantibodies production by splenic B lymphocytes [

40,

41,

44,

45,

47].

Further studies in lupus-prone MRL/Mp-lpr/lpr (MRL/lpr) and B6.

Sle1.Yaa mice revealed a beneficial effect after IL-21 neutralization in autoantibody production, and also reduced renal-infiltrating Tfh and Th1 cells, improved renal histology and and reduced GC B cells and CD138

hi plasmablasts. These studies [

40,

41] demonstrated that Tfh cells and the derived IL-21 cytokine may orchestrated the autoreactive B lymphocyte production in SLE. Yet, a simultaneous reduction of IL-10 levels, a regulatory cytokine produced by Tfh cells under the impact of IL-21, substantially restricted its beneficial effect, and revealed that Tfh cells, apart from B lymphocyte activation, may also have immune regulatory functions via production IL-10 [

25,

26]. Similarly, when ICOS activities were blocked by anti-B7RP-1 Ab in a New Zealand Black/New Zealand White (NZB/NZW) F(1) mouse model of systemic lupus erythematosus a reduction of Tfh and gcB cells was followed by amelioration of disease manifestations [

40,

41].

Very recently treatment of lupus-prone NZB/WF1 mice with CD40L antibodies or a combination CTLA4Ig and anti-CD40L reduced circulating B and T lymphocytes and improved kidney inflammation [

48]. Additionally, the use of circulating Tfh cell levels as a biomarker may aid in monitoring disease activity and adjusting treatment regimens for patients with SLE. Recent studies have proved that peripheral follicular helper T (Tfh) cells were increased during the early diagnosis of SLE, followed by a significant reduction during the first year of follow up [

49]. Furthermore, Tf regulatory cells, which inhibit B cell activation by Tfh cells, were reduced in patients with SLE, compared to healthy controls, and their levels showed a significant negative correlation with disease activity and serum anti-DNA levels. More intersingly though, both Tfr levels and Tfr/Tfh ratio were improved to almost normal after adequate treatment [

50].

6.2. Tfh Cells in Rheumatoid Arthritis (RA)

RA is a chronic autoimmune disease characterized by inflammation of synovial joints and destruction of cartilage and bone. The presence of anti-citrullinated protein antibodies (ACPAs) is a hallmark of RA, and their generation is heavily influenced by Tfh cells. Elevated numbers of Tfh cells have been identified in the blood and synovial fluid of RA patients, suggesting that they play a central role in sustaining chronic inflammation [

44,

45,

51]. Tfh cells in RA promote ACPA production by stimulating autoreactive B cells in ectopic

GCs within synovial tissue, contributing to localized inflammation and tissue damage [

52].

In RA, the cytokine milieu further promotes Tfh cell activity. IL-21 and IL-6 are both elevated in RA patients and act synergistically to enhance Tfh cell function and sustain B-cell differentiation within the synovial microenvironment. IL-6 in particular is implicated in the initial activation of Tfh cells, whereas IL-21 sustains their activity, creating an inflammatory feedback loop that amplifies autoimmune responses [

51,

52,

53]. Moreover, Tfh cells in RA express high levels of ICOS, a co-stimulatory molecule that reinforces Tfh-B cell interactions. Blocking ICOS/ICOS-L signaling in RA has shown potential to reduce Tfh-mediated inflammation, highlighting ICOS as a therapeutic target in autoimmune diseases with Tfh dysregulation [

51,

52]. Among Tfh subsets, Tfh17 cells appear to have the strongest correlation with disease severity in RA, likely due to their dual role in promoting B-cell activation and driving Th17-mediated inflammation, which is well-documented in RA pathology [

53].

The presence of ACPAs and rheumatoid factor (RF) is also a hallmark of RA. Tfh cells provide help to autoreactive B cells, promoting their differentiation into plasma cells that produce these autoantibodies. Increased Tfh activity is directly associated with higher ACPA and RF titers, which contribute to joint inflammation and tissue damage in RA. Other studies [

51,

52,

54] demonstrated that the frequency of Tfh cells in RA patients was positively correlated with ACPA levels, indicating that Tfh cells play a critical role in driving autoantibody-mediated pathology (. Given the role of Tfh cells in ACPA production, therapies targeting Tfh-B cell interactions are a promising area of investigation in RA. Rituximab, a B-cell depleting agent, has shown efficacy in RA by disrupting the cycle of Tfh-B cell cooperation. However, new therapies are being developed to target Tfh-specific pathways, potentially offering more selective modulation of immune responses without broadly depleting B cells. The use of ICOS inhibitors or IL-21 receptor blockers could provide a more nuanced approach to controlling Tfh cell activity in RA, especially for patients who do not respond to conventional therapies [

53,

54].

6.3. Tfh Cells in Anti-Neutrophil Cytoplasmic Antibodies (ANCA)-Associated Vasculitis (AAV)

AAV encompasses autoimmune conditions that involve small-vessel inflammation, driven by ANCA, which target proteins within neutrophils, leading to their activation and recruitment, release inflammatory mediators and damage vessel walls [

20]. Recent studies have revealed a role for Tfh cells in promoting ANCA production and sustaining the autoimmune response in AAV [

55].

In patients with active AAV, circulating Tfh cells are significantly increased and correlate with ANCA titers, suggesting that Tfh cells actively drive disease activity. IL-21, predominantly produced by Tfh cells, is elevated in AAV and contributes to the differentiation of B cells into ANCA-producing plasma cells. This cytokine-driven interaction highlights Tfh cells as central players in maintaining the chronic inflammatory state characteristic of AAV [

56]. Moreover, ectopic lymphoid structures have been observed in inflamed tissues of AAV patients, providing a local environment for Tfh-B cell interactions and further promoting ANCA production.

Studies such as those [

57] support the therapeutic potential of targeting IL-21 in AAV. Blocking IL-21 reduces ANCA levels and diminishes disease severity in preclinical models, suggesting that IL-21 inhibition may alleviate inflammation without compromising other immune functions. Given the link between Tfh cells, IL-21, and ANCA production, IL-21 blockade could become a targeted strategy for treating AAV, potentially slowing disease progression and reducing relapse rates [

55,

56].

In addition to IL-21, other Tfh-associated pathways, such as PD-1 and ICOS, are being explored for their potential roles in AAV. For instance, impairments in PD-1 signaling, which typically act as a checkpoint to limit Tfh cell activity, may contribute to the persistence of autoreactive Tfh cells in AAV. Enhancing PD-1 signaling could help restore immune tolerance and suppress ANCA production, providing a novel therapeutic approach for managing AAV [

57,

58].

The role of Tfh cells in autoimmune diseases like SLE, RA, and AAV underscores their importance as mediators of immune dysregulation and highlights the potential for targeted therapies. Through their interactions with B cells, Tfh cells facilitate the production of high-affinity autoantibodies, perpetuating inflammation and tissue damage. Cytokines like IL-21 and IL-6 play crucial roles in these processes, both promoting Tfh cell survival and enhancing their pathogenic effects. Therapeutic strategies aimed at disrupting Tfh-B cell interactions, blocking Tfh-derived cytokines, or modulating co-stimulatory pathways (e.g., ICOS, PD-1) may offer effective means of managing autoimmune diseases driven by Tfh cell dysregulation. Understanding Tfh cells' diverse roles in a normal immune response and in various autoimmune settings continues to inform new, precision-targeted treatments with the potential to reduce disease activity and improve patient outcomes.

The recent studies on ANCA-associated vasculitis (AAV) have added significant depth to the understanding of Tfh cells in autoimmune pathology. Older studies [

57] highlighted that elevated Tfh cells in GPA (a form of AAV) are associated with increased ANCA titers and more severe disease manifestations. These findings suggest that Tfh cells could be used as biomarkers for disease activity and potentially to predict flares in AAV patients. By showing that IL-21 produced by Tfh cells drives ANCA production, the study reinforces the potential of IL-21 blockade as a therapeutic approach in AAV, which could help mitigate the chronic vascular inflammation and immune dysregulation characteristic of the disease [

59].

These insights into the role of IL-21 in supporting ANCA-producing B cells highlight Tfh cells as central players in AAV. Together, these studies suggest that modulating Tfh activity or blocking IL-21 could provide new therapeutic options for AAV, aligning Tfh cells with targeted interventions that reduce disease burden without broader immunosuppressive effects [

60,

61].

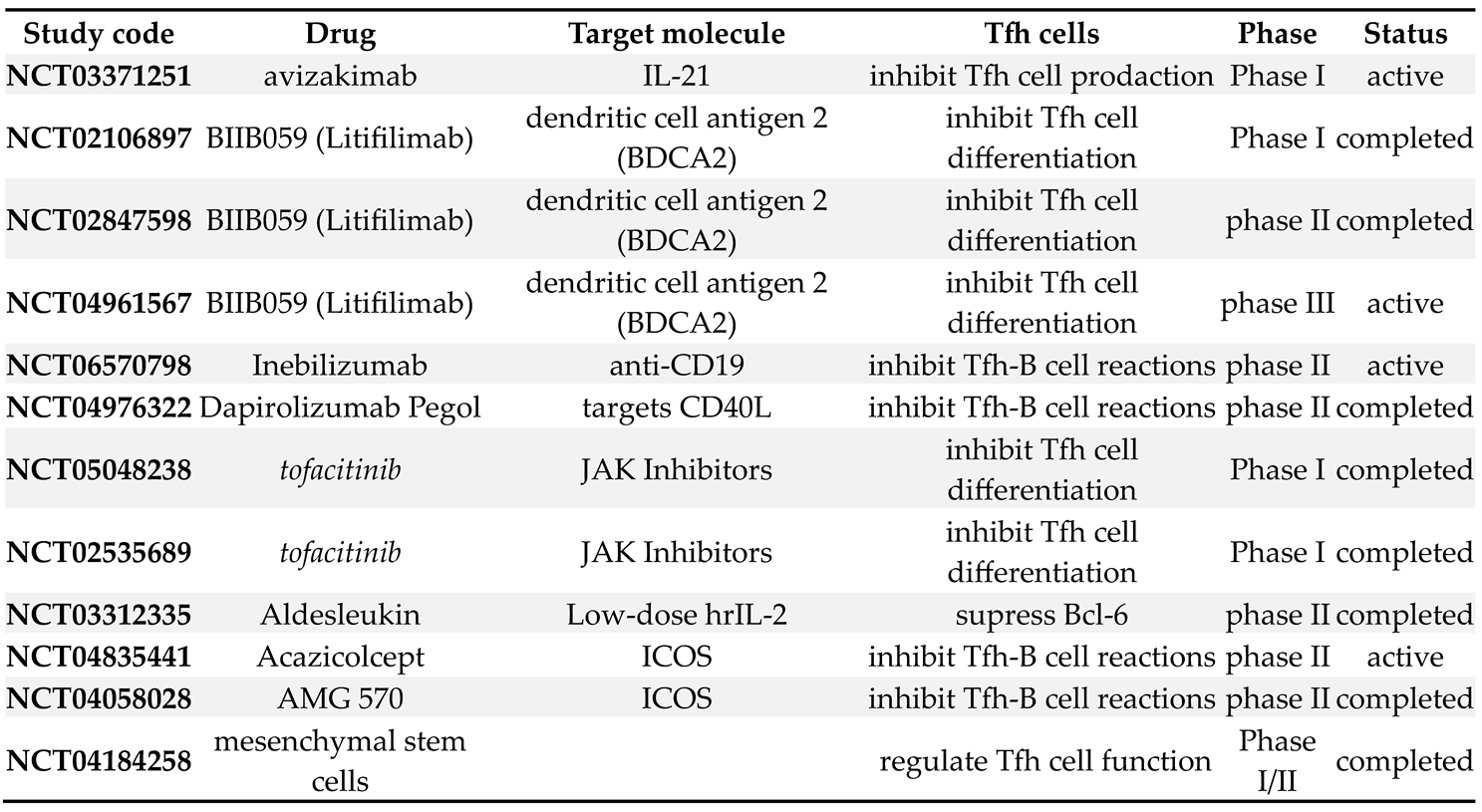

7. Therapeutic Implications in Humans

The central role of Tfh cells in promoting autoreactive B-cell responses makes them an attractive target for therapeutic intervention in autoimmune diseases. Several strategies have been proposed to modulate Tfh cell activity, either by directly targeting Tfh cells or by disrupting their interactions with B cells.

7.1. Targeting IL-21 Signaling

Given the critical role of IL-21 in Tfh cell function, blocking IL-21 signaling is a promising approach for reducing autoantibody production in autoimmune diseases. Clinical trials are currently underway to evaluate the efficacy of IL-21 receptor antagonists in diseases such as SLE and RA [

62]. In addition, therapies targeting IL-21 may be beneficial in AAV, where elevated IL-2 levels are associated with increased ANCA production and disease activity [

63].

7.2. Bcl-6 Inhibitors

As the master regulator of Tfh cell differentiation, Bcl-6 represents another potential therapeutic target. Bcl-6 inhibitors have been shown to reduce Tfh cell numbers and suppress

GC formation in preclinical models of autoimmune disease [

63,

64]. However, targeting Bcl-6 must be approached with caution, as this transcription factor also regulates other aspects of immune function.

7.3. PD-1/PD-L1 Modulation

The PD-1/PD-L1 pathway plays a critical role in regulating Tfh cell activity and preventing excessive

GC responses. Enhancing PD-1 signaling in autoimmune diseases could help to suppress the overactivity of Tfh cells and reduce autoantibody production [

65,

66]. However, the challenge lies in balancing the suppression of autoreactive Tfh cells with the preservation of normal immune responses, as PD-1 signaling is also important for maintaining tolerance to infections and tumors [

67].

Most of clinical studies, targeting Tfc function and their interaction with B cells, have been performed in patients with SLE, and are demonstrated in

Table 2.

8. Conclusions

T follicular helper (Tfh) cells play a central role in the immune system by facilitating the development of high-affinity antibody responses through their interactions with B cells in GCs. In the context of autoimmune diseases, however, these cells become key players in immune dysregulation and pathogenic autoantibody production. Their ability to drive B-cell maturation and antibody generation makes them indispensable for effective immunity, but also makes them liable to promote the progression of autoimmunity when dysregulated. This dual nature of Tfh cells—crucial for both protective and pathological immune responses—has made them a focal point in the study of diseases such as SLE, RA, and AAV.

A major contribution of Tfh cells to autoimmune diseases is through their production of cytokines, particularly IL-21, which supports the proliferation and differentiation of autoreactive B cells. Elevated levels of circulating Tfh-like cells and IL-21 have been observed in patients with SLE, RA, and AAV, correlating strongly with disease severity and autoantibody levels. The feedback loop between IL-21 and Tfh cells not only sustains Tfh cell function but also drives the continuous expansion of autoreactive B cells, leading to the production of pathogenic antibodies that damage tissues and drive chronic inflammation. By understanding these interactions, researchers have identified potential therapeutic targets, with IL-21 blockade emerging as a promising strategy in managing autoimmune disease symptoms and slowing progression.

The role of Tfh cells in the regulation of humoral immunity and their contribution to autoimmune diseases has been increasingly recognized over the past decade. Through their interactions with B cells, Tfh cells promote the production of high-affinity antibodies, a process that is crucial for the clearance of pathogens. However, when dysregulated, Tfh cells drive the production of autoantibodies that target self-antigens, leading to chronic inflammation and tissue damage.

In autoimmune diseases such as SLE, RA, and AAV, the overactivation of Tfh cells and the subsequent breakdown of tolerance mechanisms lead to the production of pathogenic autoantibodies that drive disease progression. In SLE, elevated levels of circulating Tfh cells and the overproduction of IL-21 contribute to the expansion of autoreactive B cells, resulting in the production of anti-dsDNA and anti-Sm antibodies. Similarly, in RA, Tfh cells play a central role in the generation of ACPAs, which drive synovial inflammation and joint destruction.

The identification of Tfh cells in AAV is particularly noteworthy, as it extends our understanding of the role of Tfh cells beyond traditional autoimmune diseases characterized by systemic inflammation. In AAV, the expansion of circulating Tfh cells and the production of IL-21 are associated with increased ANCA titers and disease activity. These findings suggest that Tfh cells are directly involved in driving the pathogenic B-cell responses that lead to vascular inflammation and damage in AAV.

Looking to the future, Tfh cell research offers promising opportunities for targeted therapies that modulate Tfh activity without compromising immune function. As our understanding of Tfh cell regulation expands, therapies that selectively inhibit pathogenic Tfh responses while preserving protective immunity are likely to emerge. The development of subtype-specific inhibitors and cytokine blockers, along with Tfh cell-related biomarkers could transform autoimmune disease treatment, leading to more effective care for patients with chronic autoimmune conditions. However, challenges remain in ensuring that these therapies do not induce excessive immunosuppression, leaving patients vulnerable to infections or blunting responses to vaccines.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Qi J, Liu C, Bai Z, Li X, Yao G. T follicular helper cells and T follicular regulatory cells in autoimmune diseases. Front Immunol. 2023 Apr 28;14:1178792. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2023.1178792. PMID: 37187757; PMCID: PMC10175690.

- Crotty, S. (2011). Follicular helper CD4 T cells (Tfh). Annual Review of Immunology, 29(1), 621-663.

- Gonzalez-Figueroa P, Roco JA, Papa I, Núñez Villacís L, Stanley M, Linterman MA, Dent A, Canete PF, Vinuesa CG. Follicular regulatory T cells produce neuritin to regulate B cells. Cell. 2021 Apr 1;184(7):1775-1789.e19. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2021.02.027. Epub 2021 Mar 11. PMID: 33711260.

- Le Coz C, Oldridge DA, Herati RS, De Luna N, Garifallou J, Cruz Cabrera E, Belman JP, Pueschl D, Silva LV, Knox AVC, Reid W, Yoon S, Zur KB, Handler SD, Hakonarson H, Wherry EJ, Gonzalez M, Romberg N. Human T follicular helper clones seed the germinal center-resident regulatory pool. Sci Immunol. 2023 Apr 14;8(82):eade8162. doi: 10.1126/sciimmunol.ade8162. Epub 2023 Apr 7. PMID: 37027481; PMCID: PMC10329285.

- Zhang M, Zhang S. T Cells in Fibrosis and Fibrotic Diseases. Front Immunol. 2020 Jun 26;11:1142. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2020.01142. PMID: 32676074; PMCID: PMC7333347.

- Linterman, M. A., et al. (2011). Follicular helper T cells are required for systemic autoimmunity. The Journal of Experimental Medicine, 208(5), 897-911.

- Sage, P. T., Francisco, L. M., Carman, C. V., & Sharpe, A. H. (2013). The receptor PD-1 controls follicular regulatory T cells in the lymph nodes and blood. Nature Immunology, 14(2), 152-161.

- Long Y, Feng J, Ma Y, Sun Y, Xu L, Song Y, Liu C. Altered follicular regulatory T (Tfr)- and helper T (Tfh)-cell subsets are associated with autoantibody levels in microscopic polyangiitis patients. Eur J Immunol. 2021 Jul;51(7):1809-1823. doi: 10.1002/eji.202049093. Epub 2021 Apr 23. PMID: 33764509.

- Vinuesa, C. G., & Tangye, S. G. (2014). Molecular interactions underpinning T follicular helper cell differentiation. Immunology and Cell Biology, 92(1), 36-44.

- Craft, J. Follicular helper T cells in immunity and systemic autoimmunity. Nat. Rev. Rheumatol. 2012, 8, 337–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, Y. S., et al. (2011). Bcl-6 controls the fate of follicular helper T cells and the germinal center reaction. Science, 341(6141), 673-677.

- Johnston, R. J., et al. (2009). Bcl6 and Blimp-1 are reciprocal and antagonistic regulators of T follicular helper cell differentiation. Science, 325(5943), 1006-1010.

- Sage, P. T., et al. (2016). Regulation of germinal center responses by T follicular regulatory cells. Journal of Clinical Investigation, 126(5), 1511-1520.

- Mohammed MT, Sage PT. Follicular T-cell regulation of alloantibody formation. Curr Opin Organ Transplant. 2020 Feb;25(1):22-26. doi: 10.1097/MOT.0000000000000715. PMID: 31789953; PMCID: PMC7323906.

- Zhao Z, Xu B, Wang S, Zhou M, Huang Y, Guo C, Li M, Zhao J, Sung SJ, Gaskin F, Yang N, Fu SM. Tfh cells with NLRP3 inflammasome activation are essential for high-affinity antibody generation, germinal centre formation and autoimmunity. Ann Rheum Dis. 2022 Jul;81(7):1006-1012. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2021-221985. Epub 2022 Apr 12. PMID: 35414518; PMCID: PMC9262832.

- Zhu X, Chen X, Cao Y, Liu C, Hu G, Ganesan S, Veres TZ, Fang D, Liu S, Chung H, Germain RN, Schwartzberg PL, Zhao K, Zhu J. Optimal CXCR5 Expression during Tfh Maturation Involves the Bhlhe40-Pou2af1 Axis. bioRxiv [Preprint]. 2024 May 20:2024.05.16.594397. doi: 10.1101/2024.05.16.594397. PMID: 38903096; PMCID: PMC11188140.

- Wei X, Niu X. T follicular helper cells in autoimmune diseases. J Autoimmun. 2023 Jan;134:102976. doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2022.102976. Epub 2022 Dec 14. PMID: 36525939.

- Feng H, Zhao Z, Zhao X, Bai X, Fu W, Zheng L, Kang B, Wang X, Zhang Z, Dong C. A novel memory-like Tfh cell subset is precursor to effector Tfh cells in recall immune responses. J Exp Med. 2024 Jan 1;221(1):e20221927. doi: 10.1084/jem.20221927. Epub 2023 Dec 4. PMID: 38047912; PMCID: PMC10695277.

- Liu D, Yan J, Sun J, Liu B, Ma W, Li Y, Shao X, Qi H. BCL6 controls contact-dependent help delivery during follicular T-B cell interactions. Immunity. 2021 Oct 12;54(10):2245-2255.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2021.08.003. Epub 2021 Aug 30. PMID: 34464595; PMCID: PMC8528402.

- Huang C. Germinal Center Reaction. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2020;1254:47-53. doi: 10.1007/978-981-15-3532-1_4. PMID: 32323268.

- Dong C. Cytokine Regulation and Function in T Cells. Annu Rev Immunol. 2021 Apr 26;39:51-76. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-061020-053702. Epub 2021 Jan 11. PMID: 33428453.

- Zhang H, Cavazzoni CB, Podestà MA, Bechu ED, Ralli G, Chandrakar P, Lee JM, Sayin I, Tullius SG, Abdi R, Chong AS, Blazar BR, Sage PT. IL-21-producing effector Tfh cells promote B cell alloimmunity in lymph nodes and kidney allografts. JCI Insight. 2023 Oct 23;8(20):e169793. doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.169793. PMID: 37870962; PMCID: PMC10619486.

- Xia Y, Sandor K, Pai JA, Daniel B, Raju S, Wu R, Hsiung S, Qi Y, Yangdon T, Okamoto M, Chou C, Hiam-Galvez KJ, Schreiber RD, Murphy KM, Satpathy AT, Egawa T. BCL6-dependent TCF-1+ progenitor cells maintain effector and helper CD4+ T cell responses to persistent antigen. Immunity. 2022 Jul 12;55(7):1200-1215.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2022.05.003. Epub 2022 May 27. PMID: 35637103; PMCID: PMC10034764.

- Butcher MJ, Zhu J. Recent advances in understanding the Th1/Th2 effector choice. Fac Rev. 2021 Mar 15;10:30. doi: 10.12703/r/10-30. PMID: 33817699; PMCID: PMC8009194.

- Johnston RJ, Poholek AC, DiToro D, Yusuf I, Eto D, Barnett B, Dent AL, Craft J, Crotty S. Bcl6 and Blimp-1 are reciprocal and antagonistic regulators of T follicular helper cell differentiation. Science. 2009 Aug 21;325(5943):1006-10. doi: 10.1126/science.1175870. Epub 2009 Jul 16. PMID: 19608860; PMCID: PMC2766560.

- Fonseca VR, Ribeiro F, Graca L. T follicular regulatory (Tfr) cells: Dissecting the complexity of Tfr-cell compartments. Immunol Rev. 2019 Mar;288(1):112-127. doi: 10.1111/imr.12739. PMID: 30874344.

- Ding T, Su R, Wu R, Xue H, Wang Y, Su R, Gao C, Li X, Wang C. Frontiers of Autoantibodies in Autoimmune Disorders: Crosstalk Between Tfh/Tfr and Regulatory B Cells. Front Immunol. 2021 Mar 26;12:641013. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2021.641013. PMID: 33841422; PMCID: PMC8033031.

- Walker LSK. The link between circulating follicular helper T cells and autoimmunity. Nat Rev Immunol. 2022 Sep;22(9):567-575. doi: 10.1038/s41577-022-00693-5. Epub 2022 Mar 11. PMID: 35277664; PMCID: PMC8915145.

- Iwamoto Y, Ueno H. Circulating T Follicular Helper Subsets in Human Blood. Methods Mol Biol. 2022;2380:29-39. doi: 10.1007/978-1-0716-1736-6_3. PMID: 34802119.

- Szabó K, Jámbor I, Pázmándi K, Nagy N, Papp G, Tarr T. Altered Circulating Follicular T Helper Cell Subsets and Follicular T Regulatory Cells Are Indicators of a Derailed B Cell Response in Lupus, Which Could Be Modified by Targeting IL-21R. Int J Mol Sci. 2022 Oct 13;23(20):12209. doi: 10.3390/ijms232012209. PMID: 36293075; PMCID: PMC9602506.

- Kim, S. J., & Gregg, R. K. (2014). Follicular helper T (Tfh) cells and systemic lupus erythematosus. *nternational Immunopharmacology, 20(2), 116-123.

- Simpson, N., et al. (2010). Expansion of circulating Tfh-like cells in SLE patients is associated with autoantibody levels and disease activity. Immunology, 130(2), 176-183.

- Ueno, H., et al. (2015). Circulating T follicular helper cells in human health and disease. Journal of Clinical Immunology, 35(3), 173-181

.

- Ma, X., Nakayamada, S., & Wang, J. (2021). Multi-Source Pathways of T Follicular Helper Cell Differentiation. Frontiers in Immunology, 12, 621105.

- Tenbrock K, Rauen T. T cell dysregulation in SLE. Clin Immunol. 2022 Jun;239:109031. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2022.109031. Epub 2022 May 6. PMID: 35526790.

- Shi X, Liao T, Chen Y, Chen J, Liu Y, Zhao J, Dang J, Sun Q, Pan Y. Dihydroartemisinin inhibits follicular helper T and B cells: implications for systemic lupus erythematosus treatment. Arch Pharm Res. 2024 Jul;47(7):632-644. doi: 10.1007/s12272-024-01505-1. Epub 2024 Jul 8. PMID: 38977652.

- Jackson SW, Jacobs HM, Arkatkar T, Dam EM, Scharping NE, Kolhatkar NS, Hou B, Buckner JH, Rawlings DJ. B cell IFN-γ receptor signaling promotes autoimmune germinal centers via cell-intrinsic induction of BCL-6. J Exp Med. 2016 May 2;213(5):733-50. doi: 10.1084/jem.20151724. Epub 2016 Apr 11. PMID: 27069113; PMCID: PMC4854732.

- Ou Q, Qiao X, Li Z, Niu L, Lei F, Cheng R, Xie T, Yang N, Liu Y, Fu L, Yang J, Mao X, Kou X, Chen C, Shi S. Apoptosis releases hydrogen sulfide to inhibit Th17 cell differentiation. Cell Metab. 2024 Jan 2;36(1):78-89.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2023.11.012. Epub 2023 Dec 18. PMID: 38113886.

- Liu X, Zhou S, Huang M, Zhao M, Zhang W, Liu Q, Song K, Wang X, Liu J, OuYang Q, Dong Z, Yang M, Li Z, Lin L, Liu Y, Yu Y, Liao S, Zhu J, Liu L, Li W, Jia L, Zhang A, Guo C, Yang L, Li QG, Bai X, Li P, Cai G, Lu Q, Chen X. DNA methylation and whole-genome transcription analysis in CD4+ T cells from systemic lupus erythematosus patients with or without renal damage. Clin Epigenetics. 2024 Jul 30;16(1):98. doi: 10.1186/s13148-024-01699-7. PMID: 39080788; PMCID: PMC11290231.

- Rasmussen TK. Follicular T helper cells and IL-21 in rheumatic diseases. Dan Med J. 2016 Oct;63(10):B5297. PMID: 27697141.

- Zhu, X., & Zhu, J. (2020). CD4 T Helper Cell Subsets and Related Human Immunological Disorders. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 21(21), 8011.

- Schmitt, N., et al. (2014). IL-21-producing CD4+ Tfh cells drive chronic inflammation in systemic lupus erythematosus. Nature Immunology, 15(5), 396-405.

- Ji, Long-Shan, Sun, Xue-Hua, Zhang, Xin, Zhou, Zhen-Hua, Yu, Zhuo, Zhu, Xiao-Jun, Huang, Ling-Ying, Fang, Miao, Gao, Ya-Ting, Li, Man, Gao, Yue-Qiu, Mechanism of Follicular Helper T Cell Differentiation Regulated by Transcription Factors, Journal of Immunology Research, 2020, 1826587, 9 pages, 2020.

- Bugatti, S., et al. (2014). Circulating T follicular helper cells in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis & Rheumatology, 66(8), 2285-2293.

- Choi, S. W., & Rho, J. (2017). The role of Tfh cells in the immunopathogenesis of rheumatoid arthritis. Journal of Autoimmunity, 77, 104-110.

- Samson, M., et al. (2016). Follicular helper T cells: a new role in rheumatic diseases. Joint Bone Spine, 83(3), 241-246.

- Nurieva, R. I., et al. (2008). Tfh cells represent a distinct lineage differentiated from Th1, Th2, and Th17 cells. Nature Immunology, 9(9), 1074-1085.

- Yin Y, Zhao L, Zhang F, Zhang X. Impact of CD200-Fc on dendritic cells in lupus-prone NZB/WF1 mice. Sci Rep. 2016 Aug 22;6:31874. doi: 10.1038/srep31874. PMID: 27545083; PMCID: PMC4992952.

- Luo Q, Xiao Q, Zhang L, Fu B, Li X, Huang Z, Li J. Circulating TIGIT±PD1+TPH, TIGIT ± PD1+TFH cells are elevated and their predicting role in systemic lupus erythematosus. Heliyon. 2024 Mar 12;10(6):e27687. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e27687. PMID: 38515720; PMCID: PMC10955264.

- Miao M, Xiao X, Tian J, Zhufeng Y, Feng R, Zhang R, Chen J, Zhang X, Huang B, Jin Y, Sun X, He J, Li Z. Therapeutic potential of targeting Tfr/Tfh cell balance by low-dose-IL-2 in active SLE: a post hoc analysis from a double-blind RCT study. Arthritis Res Ther. 2021 Jun 11;23(1):167. doi: 10.1186/s13075-021-02535-6. PMID: 34116715; PMCID: PMC8194162.

- Zhou S, Lu H, Xiong M. Identifying Immune Cell Infiltration and Effective Diagnostic Biomarkers in Rheumatoid Arthritis by Bioinformatics Analysis. Front Immunol. 2021 Aug 13;12:726747. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2021.726747. PMID: 34484236; PMCID: PMC8411707.

- Floudas A, Canavan M, McGarry T, Mullan R, Nagpal S, Veale DJ, Fearon U. ACPA Status Correlates with Differential Immune Profile in Patients with Rheumatoid Arthritis. Cells. 2021 Mar 14;10(3):647. doi: 10.3390/cells10030647. PMID: 33799480; PMCID: PMC8000255.

- Lu J, Wu J, Xia X, Peng H, Wang S. Follicular helper T cells: potential therapeutic targets in rheumatoid arthritis. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2021 Jun;78(12):5095-5106. doi: 10.1007/s00018-021-03839-1. Epub 2021 Apr 20. PMID: 33880615; PMCID: PMC11073436.

- Rao DA, Gurish MF, Marshall JL, Slowikowski K, Fonseka CY, Liu Y, Donlin LT, Henderson LA, Wei K, Mizoguchi F, Teslovich NC, Weinblatt ME, Massarotti EM, Coblyn JS, Helfgott SM, Lee YC, Todd DJ, Bykerk VP, Goodman SM, Pernis AB, Ivashkiv LB, Karlson EW, Nigrovic PA, Filer A, Buckley CD, Lederer JA, Raychaudhuri S, Brenner MB. Pathologically expanded peripheral T helper cell subset drives B cells in rheumatoid arthritis. Nature. 2017 Feb 1;542(7639):110-114. doi: 10.1038/nature20810. PMID: 28150777; PMCID: PMC5349321.

- Pan M, Zhao H, Jin R, Leung PSC, Shuai Z. Targeting immune checkpoints in anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies associated vasculitis: the potential therapeutic targets in the future. Front Immunol. 2023 Apr 6;14:1156212. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2023.1156212. PMID: 37090741; PMCID: PMC10115969.

- Chung, S. A., & Criswell, L. A. (2021). Molecular and cellular pathways in ANCA-associated vasculitis. Nature Reviews Rheumatology, 17(9), 532-542.

- Schmitt, N., et al. (2014). Elevated circulating Tfh-like cells and IL-21 in ANCA vasculitis. Journal of Clinical Immunology, 34(7), 853-861.

- Morgan, A. W., et al. (2012). The role of IL-21 in the pathogenesis of ANCA-associated vasculitis. Journal of Autoimmunity, 39(2), 123-130.

- Jennette, J. C., & Falk, R. J. (2017). Pathogenesis of anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic autoantibody-mediated disease. Nature Reviews Rheumatology, 13(11), 670-680.

- Xu J, Zhao H, Wang S, Zheng M, Shuai Z. Elevated Level of Serum Interleukin-21 and Its Influence on Disease Activity in Anti-Neutrophil Cytoplasmic Antibodies Against Myeloperoxidase-Associated Vasculitis. J Interferon Cytokine Res. 2022 Jun;42(6):290-300. doi: 10.1089/jir.2022.0014. Epub 2022 Apr 12. Erratum in: J Interferon Cytokine Res. 2023 Apr;43(4):188. doi: 10.1089/jir.2022.0014.correx. PMID: 35416717.

- Lodka D, Zschummel M, Bunse M, Rousselle A, Sonnemann J, Kettritz R, Höpken UE, Schreiber A. CD19-targeting CAR T cells protect from ANCA-induced acute kidney injury. Ann Rheum Dis. 2024 Mar 12;83(4):499-507. doi: 10.1136/ard-2023-224875. PMID: 38182404; PMCID: PMC10958264.

- Herber D, Brown TP, Liang S, et al. IL-21 has a pathogenic role in a lupus-prone mouse model and its blockade with IL-21R.Fc reduces disease progression. Journal of Immunology (Baltimore, Md. : 1950). 2007 Mar;178(6):3822-38300.

- Yang X, Yang J, Chu Y, Xue Y, Xuan D, et al. (2014) T Follicular Helper Cells and Regulatory B Cells Dynamics in Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. PLOS ONE 9(2): e88441.

- Choi JY, Seth A, Kashgarian M, Terrillon S, Fung E, Huang L, Wang LC, Craft J.Disruption of Pathogenic Cellular Networks by IL-21 Blockade Leads to Disease Amelioration in Murine Lupus. J Immunol. 2017 Apr 1;198(7):2578-2588.

- Hu YL, Metz DP, Chung J, Siu G, Zhang M. B7RP-1 blockade ameliorates autoimmunity through regulation of follicular helper T cells. J Immunol. 2009 Feb 1;182(3):1421-8.

- Xu Y, Xu H, Zhen Y, Sang X, Wu H, Hu C, Ma Z, Yu M, Yi H. Imbalance of Circulatory T Follicular Helper and T Follicular Regulatory Cells in Patients with ANCA-Associated Vasculitis. Mediators Inflamm. 2019 Dec 2;2019:8421479. doi: 10.1155/2019/8421479. PMID: 31885499; PMCID: PMC691497.

- Wang S, Zheng MJ, Zhou XL, Liu YQ, Shuai ZW. [The clinical significance of circulating follicular helper T cells in patients with anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic myeloperoxidase antibody-associated vasculitis]. Zhonghua Nei Ke Za Zhi. 2018 Oct 1;57(10):738-742. Chinese. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cho SK, Vazquez T, Werth VP. Litifilimab (BIIB059), a promising investigational drug for cutaneous lupus erythematosus. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2023 May;32(5):345-353. doi: 10.1080/13543784.2023.2212154. Epub 2023 May 15. PMID: 37148249.

- Frampton JE. Inebilizumab: First Approval. Drugs. 2020 Aug;80(12):1259-1264. doi: 10.1007/s40265-020-01370-4. PMID: 32729016; PMCID: PMC7387876.

- Furie RA, Bruce IN, Dörner T, Leon MG, Leszczyński P, Urowitz M, Haier B, Jimenez T, Brittain C, Liu J, Barbey C, Stach C. Phase 2, randomized, placebo-controlled trial of dapirolizumab pegol in patients with moderate-to-severe active systemic lupus erythematosus. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2021 Nov 3;60(11):5397-5407. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keab381. Erratum in: Rheumatology (Oxford). 2022 Dec 23;62(1):486. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keac326. PMID: 33956056; PMCID: PMC9194804.

- Fleischmann R, Kremer J, Cush J, Schulze-Koops H, Connell CA, Bradley JD, Gruben D, Wallenstein GV, Zwillich SH, Kanik KS; ORAL Solo Investigators. Placebo-controlled trial of tofacitinib monotherapy in rheumatoid arthritis. N Engl J Med. 2012 Aug 9;367(6):495-507. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1109071. PMID: 22873530.

- Orvain C, Cauvet A, Prudent A, Guignabert C, Thuillet R, Ottaviani M, Tu L, Duhalde F, Nicco C, Batteux F, Avouac J, Wang N, Seaberg MA, Dillon SR, Allanore Y. Acazicolcept (ALPN-101), a dual ICOS/CD28 antagonist, demonstrates efficacy in systemic sclerosis preclinical mouse models. Arthritis Res Ther. 2022 Jan 5;24(1):13. doi: 10.1186/s13075-021-02709-2. PMID: 34986869; PMCID: PMC8728910.

- Zhang M, Lee F, Knize A, Jacobsen F, Yu S, Ishida K, Miner K, Gaida K, Whoriskey J, Chen C, Gunasekaran K, Hsu H. Development of an ICOSL and BAFF bispecific inhibitor AMG 570 for systemic lupus erythematosus treatment. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2019 Nov-Dec;37(6):906-914. Epub 2019 Feb 15. PMID: 30789152.

- Luque-Campos N, Contreras-López RA, Jose Paredes-Martínez M, Torres MJ, Bahraoui S, Wei M, Espinoza F, Djouad F, Elizondo-Vega RJ, Luz-Crawford P. Mesenchymal Stem Cells Improve Rheumatoid Arthritis Progression by Controlling Memory T Cell Response. Front Immunol. 2019 Apr 16;10:798. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2019.00798. PMID: 31040848; PMCID: PMC6477064.

- Xie M, Li C, She Z, Wu F, Mao J, Hun M, Luo S, Wan W, Tian J, Wen C. Human umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cells derived extracellular vesicles regulate acquired immune response of lupus mouse in vitro. Sci Rep. 2022 Jul 30;12(1):13101. doi: 10.1038/s41598-022-17331-8. PMID: 35908050; PMCID: PMC9338971.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).