Submitted:

17 March 2025

Posted:

18 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials:

2.2. Flame thermal Spray Process (FTHS):

2.3. Optical, Microstructural, Thermal and Mechanical Tests:

3. Results and Discussion

4. Conclusions

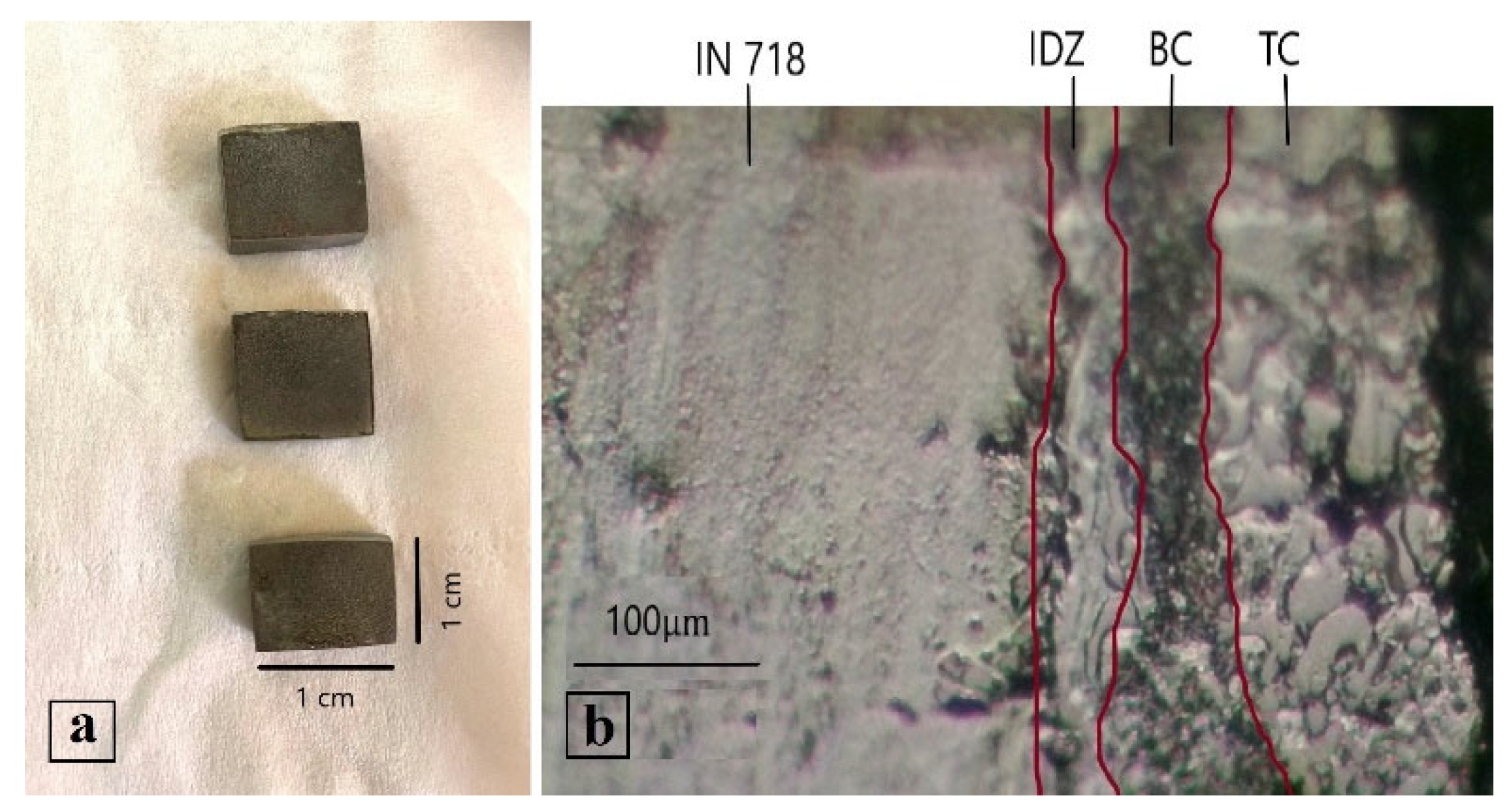

- Flame thermal spray process was successfully employed to deposit atypical BC, and TC layers as TBCs with thickness (200-300) µm on IN718 substrate that used for high temperature application such as HPT-Bs in aircraft engines.

- The matrix experiment under different flame spraying parameters confirmed that an improvement of the diffusion depth and good metallurgical bond of flame sprayed coatings can be made using the Taguchi method. The most influential parameter in the spray process was the SoD, followed by powder feeding rate, then the T. velocity.

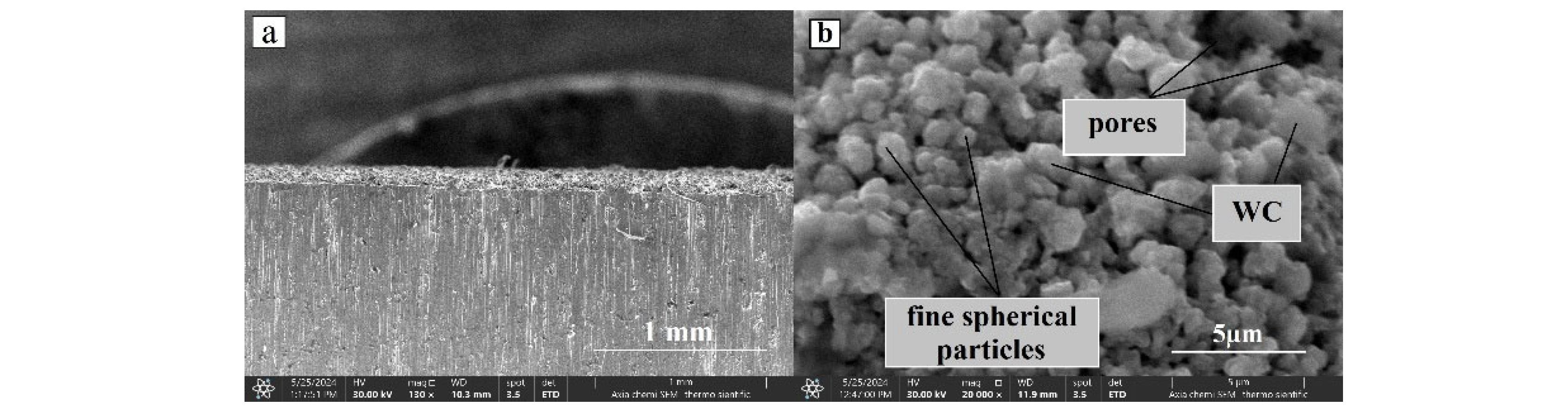

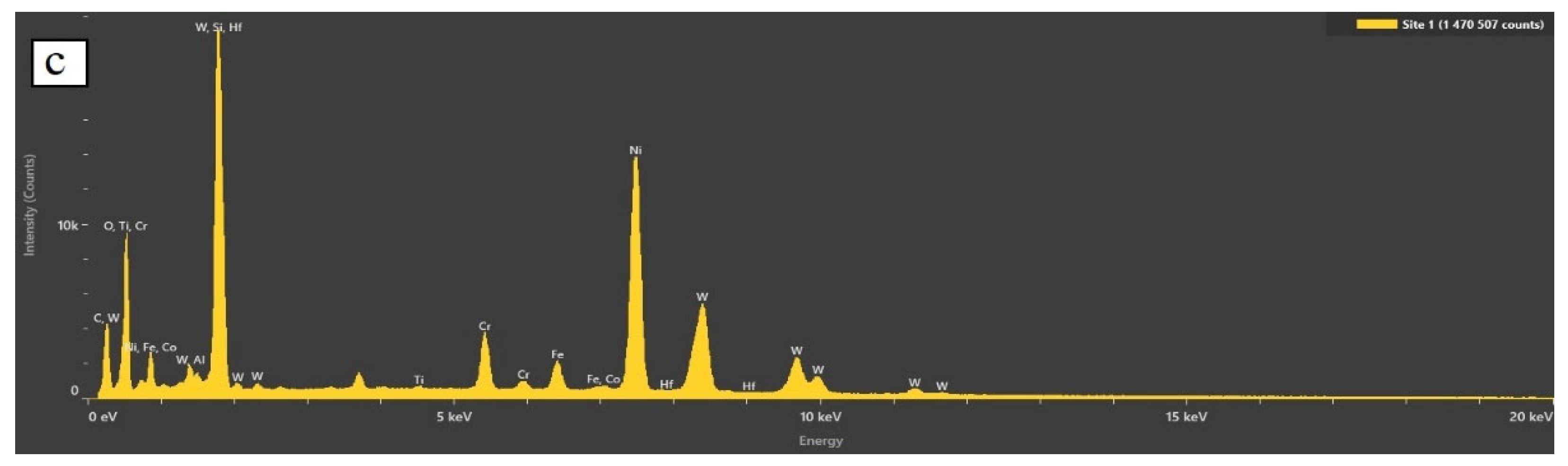

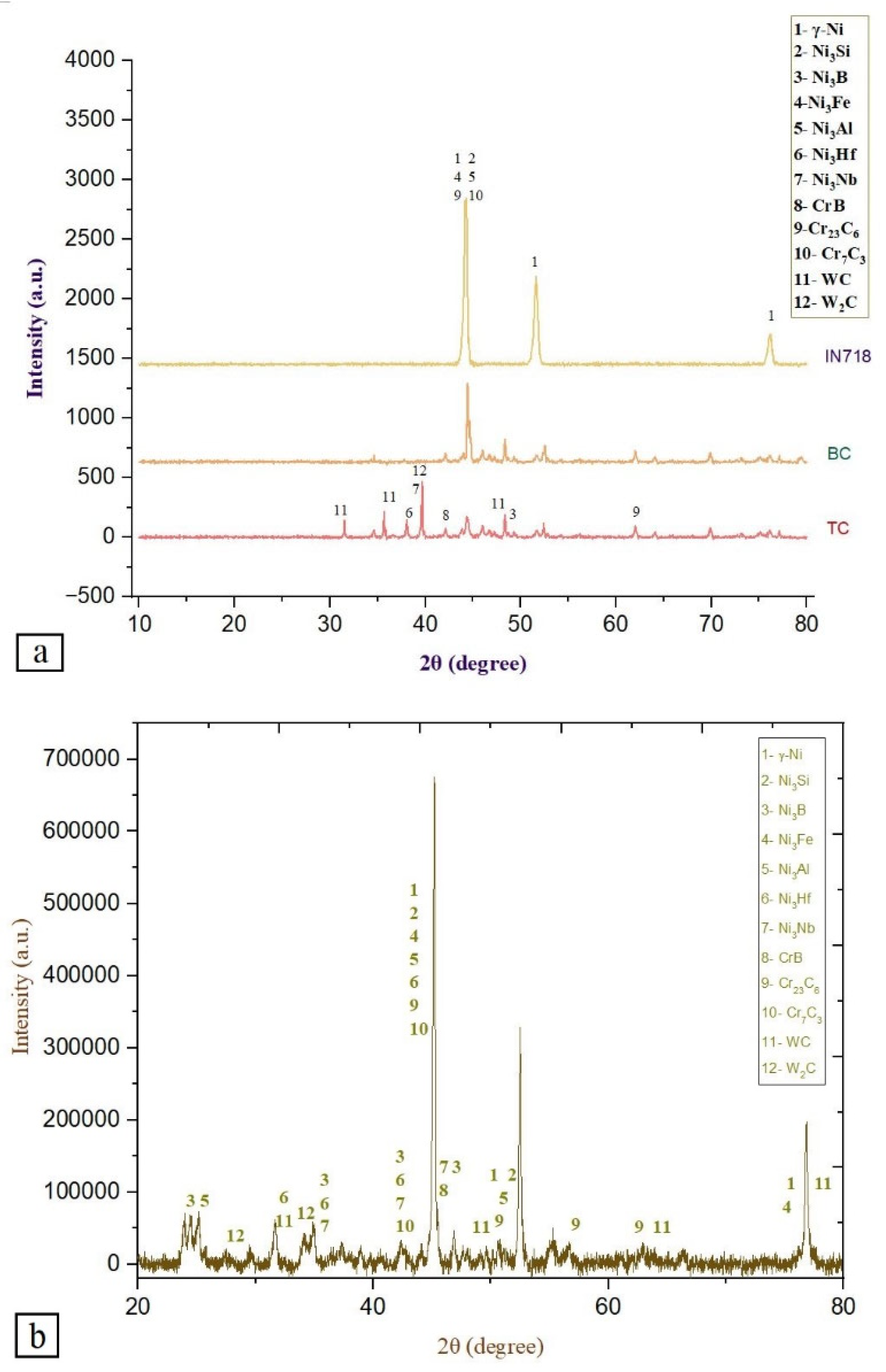

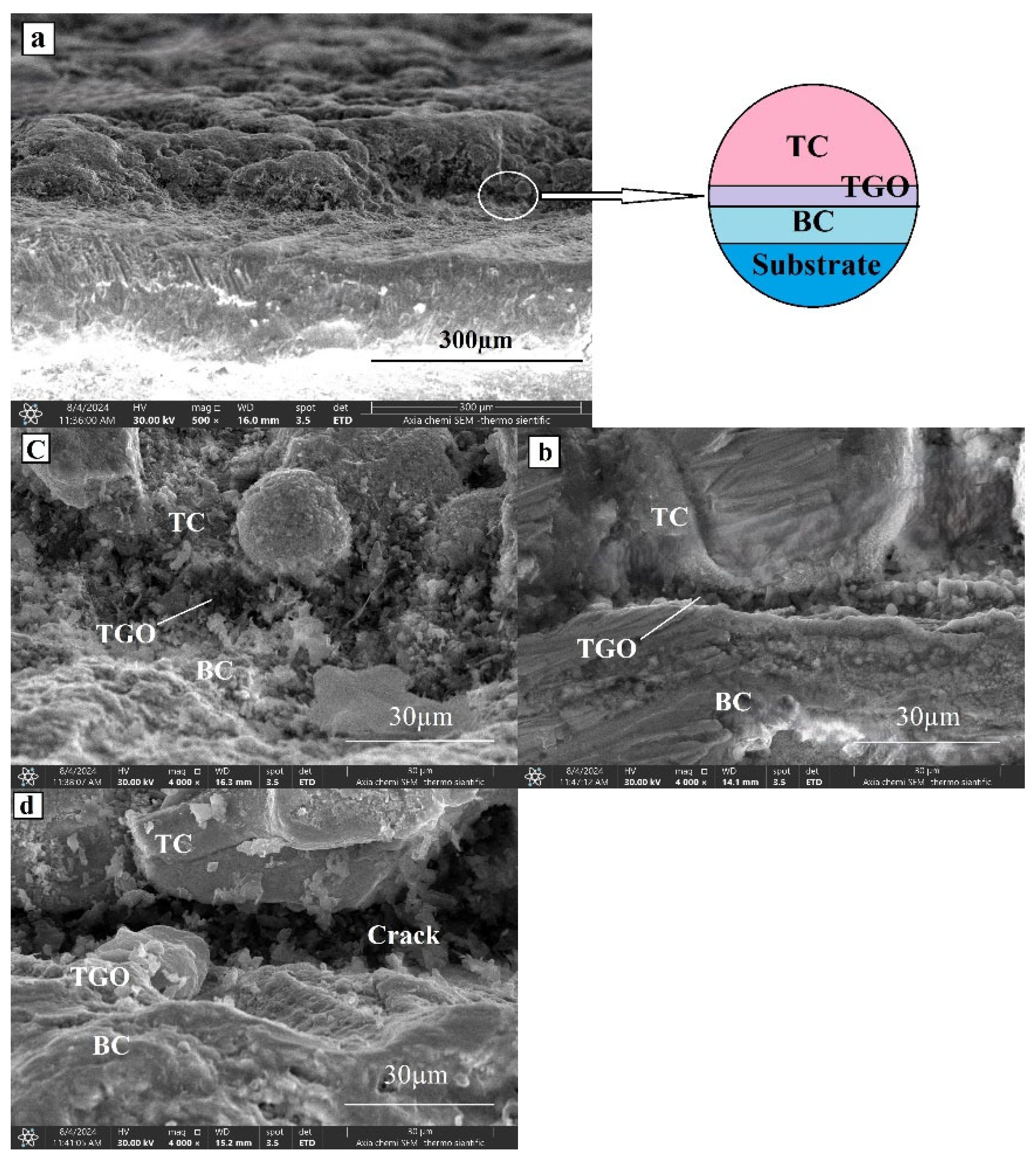

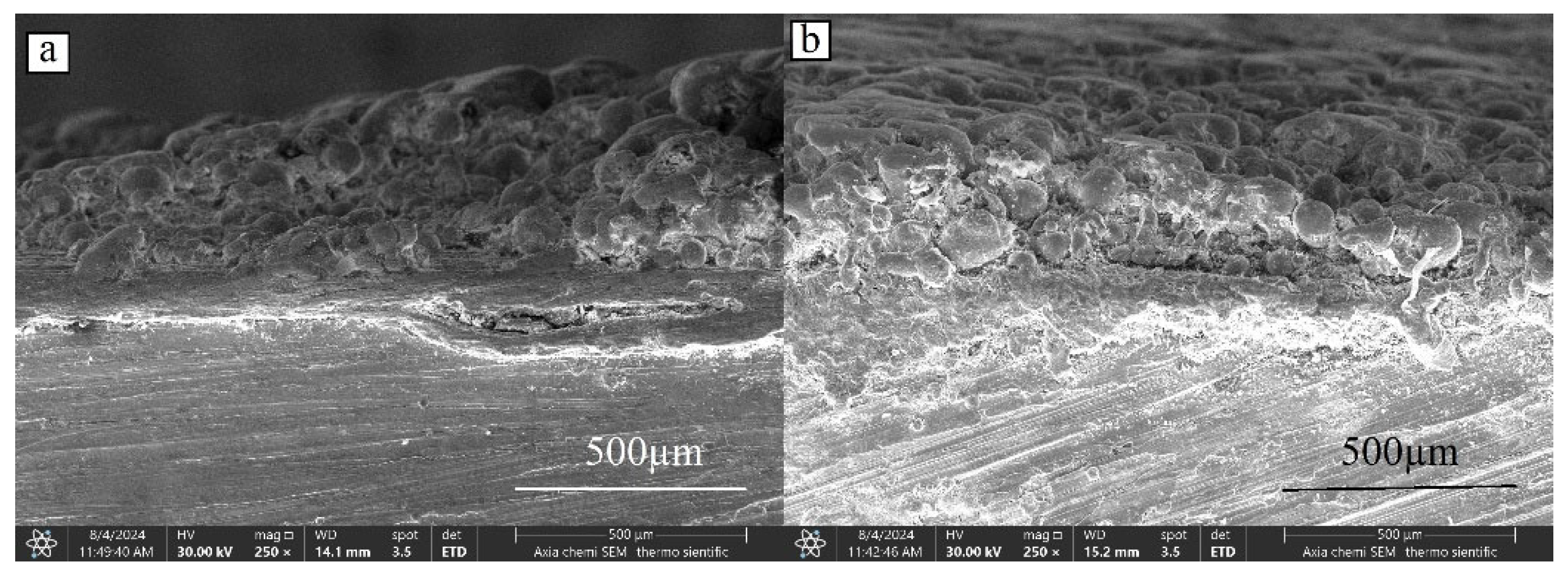

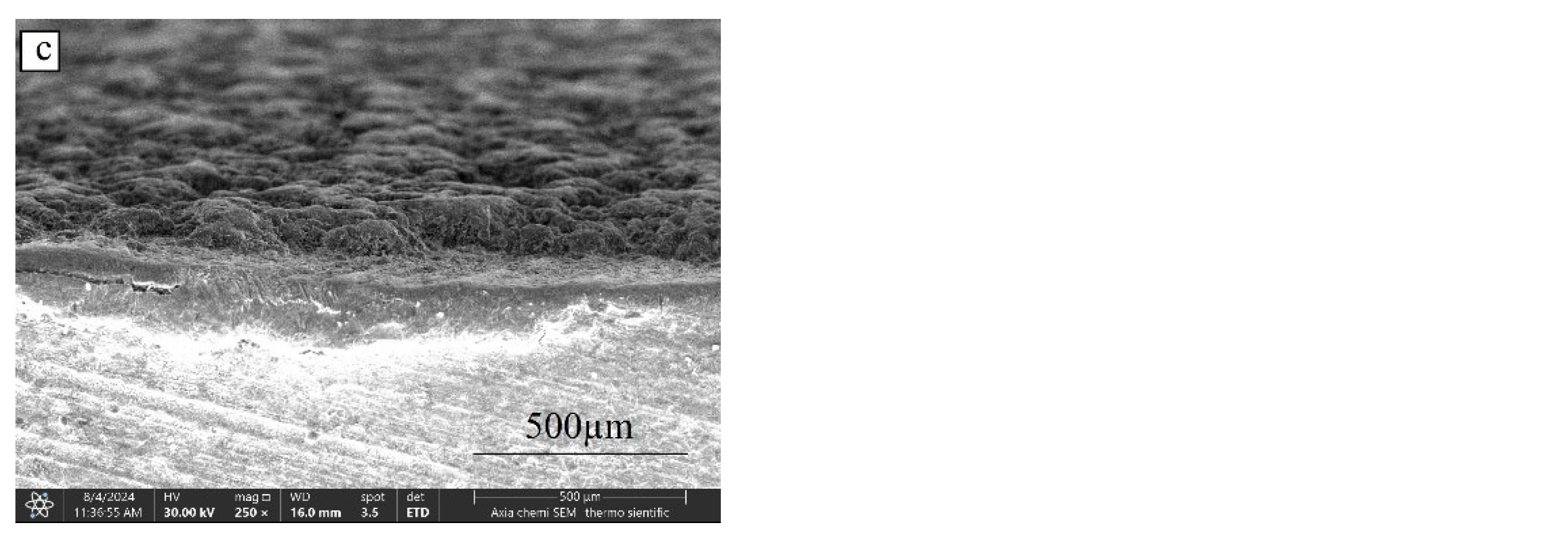

- As for the optical microscope, SEM, and EDS tests of the surface and cross section, a typical cohesion dense TBC layers formed with spherical particles of varying sizes from (300 nm to 1.6 microns). This shows the completion of the melting process for most of the particles of the primary coating material and its spread and stacked on the surface in a homogeneous manner with minimal pores and micro cracks. Also, XRD informed that TBCs consists mainly of γ-Ni, carbides such as Cr7C3, Cr23C6, and WC, borides such as Ni3B, CrB, in addition to intermetallic compounds such as Ni3Si, Ni3Al, and Ni3Nb. These phases were distributed homogenously in the formed TBCs.

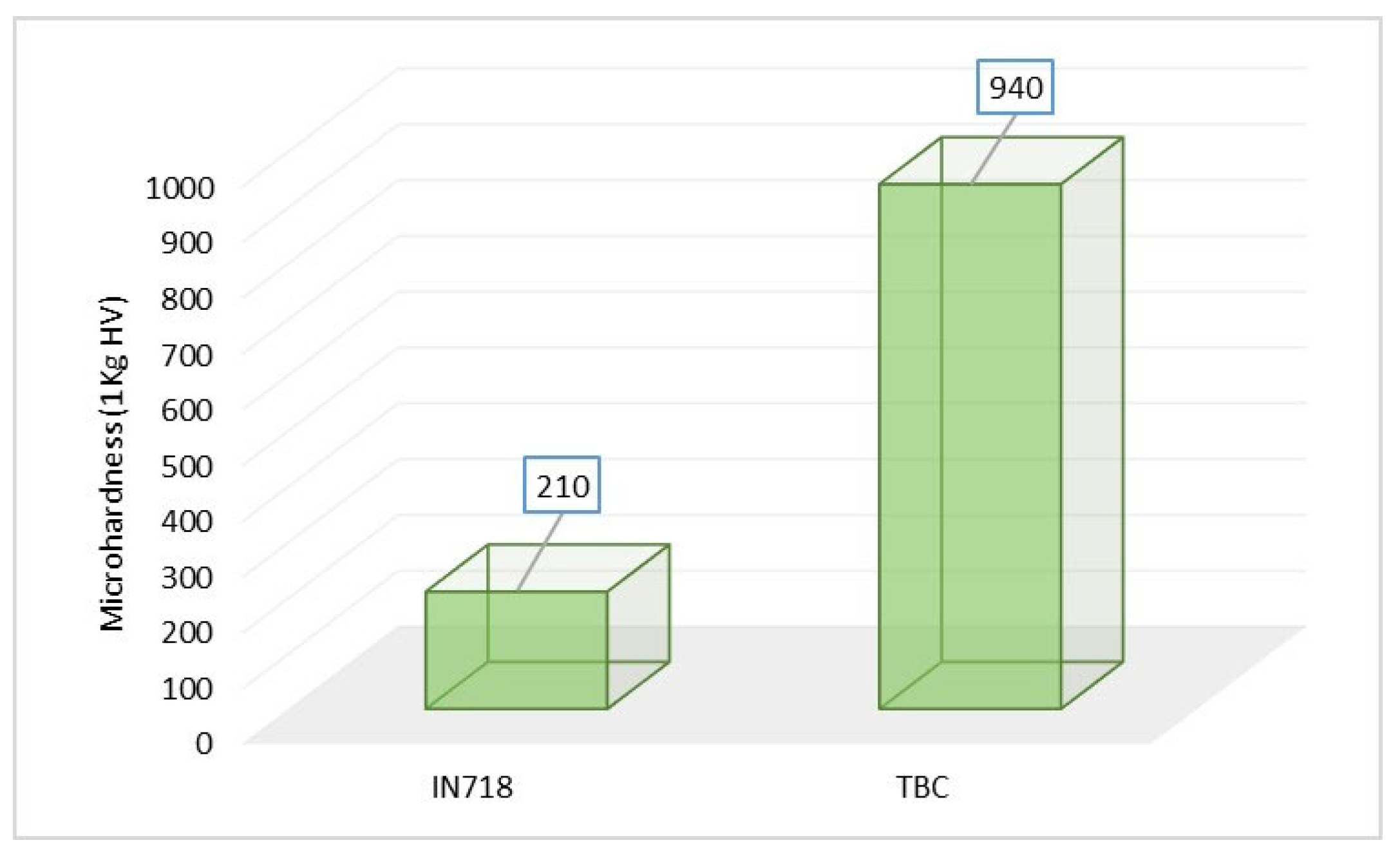

- The microhardness tests carried out on uncoated and coated samples demonstrate that the hardness increased more than 4 times due to the presence of WC hard ceramic particles in coating, in addition to uniform distribution of carbides and borides compounds in the microstructure of TBC by using FTHS process.

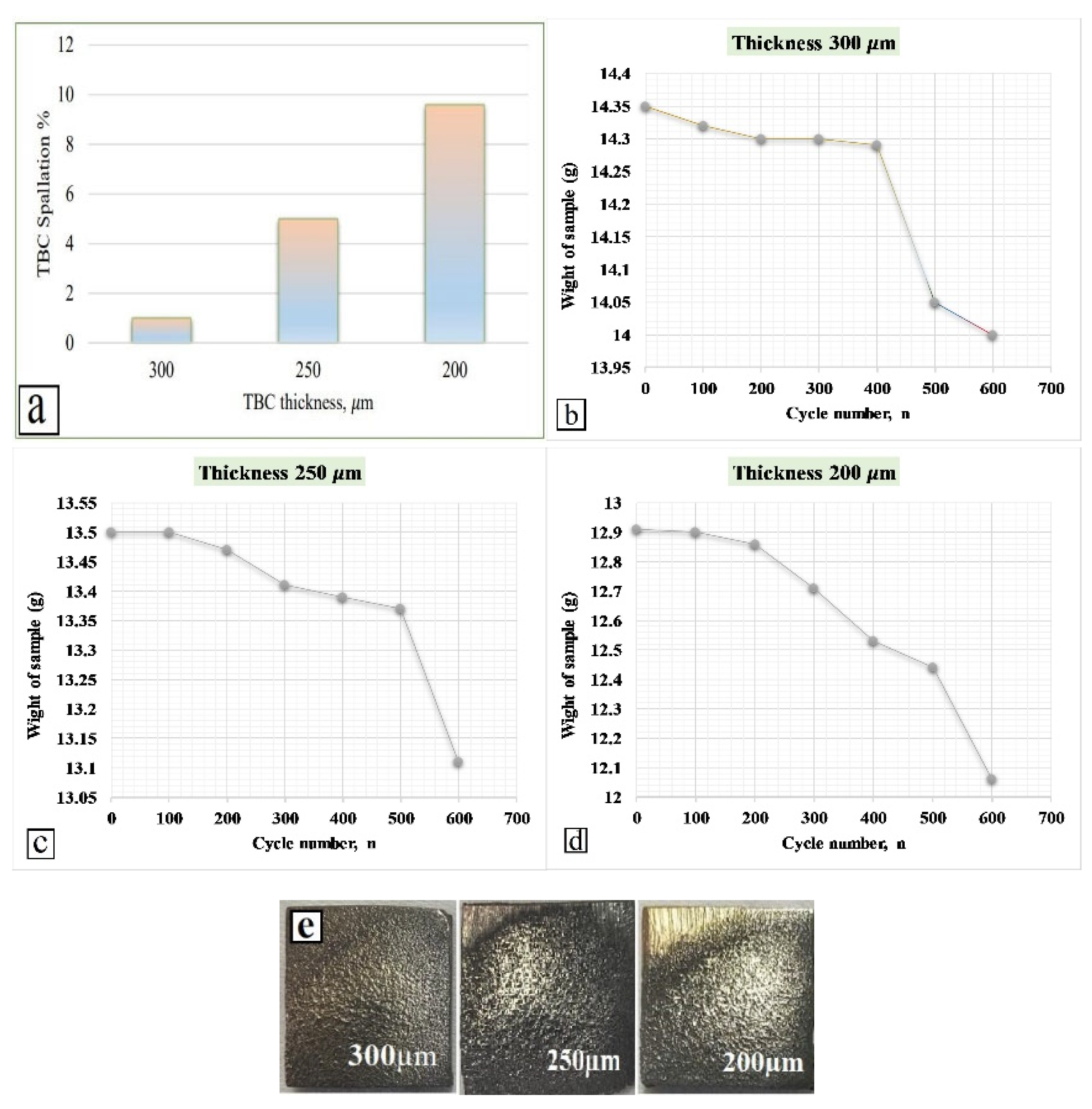

- Evaluation thermal cycling behavior of TBC with difference thickness (200, 250, and 300) µm done by using a furnace test at 1100 °C. Under heating 25min/ water cooling 10 sec/ cycle conditions the TBCs had a lifetime up to 600 cycle before spallation of TBC with thickness 200 µm reach 9,6% (10% failure criteria). In all cases, the failure modes of the TBC were segments partial spallation started from the coating edge. Best performance was observed for the coating with thickness 300 µm because increasing the thickness of TC layer and presence of γ-Ni, carbides such as Cr7C3, borides such as CrB, and intermetallic compounds such as Ni3Si, decreased the thickness of a harmly oxides layer that’s formed.

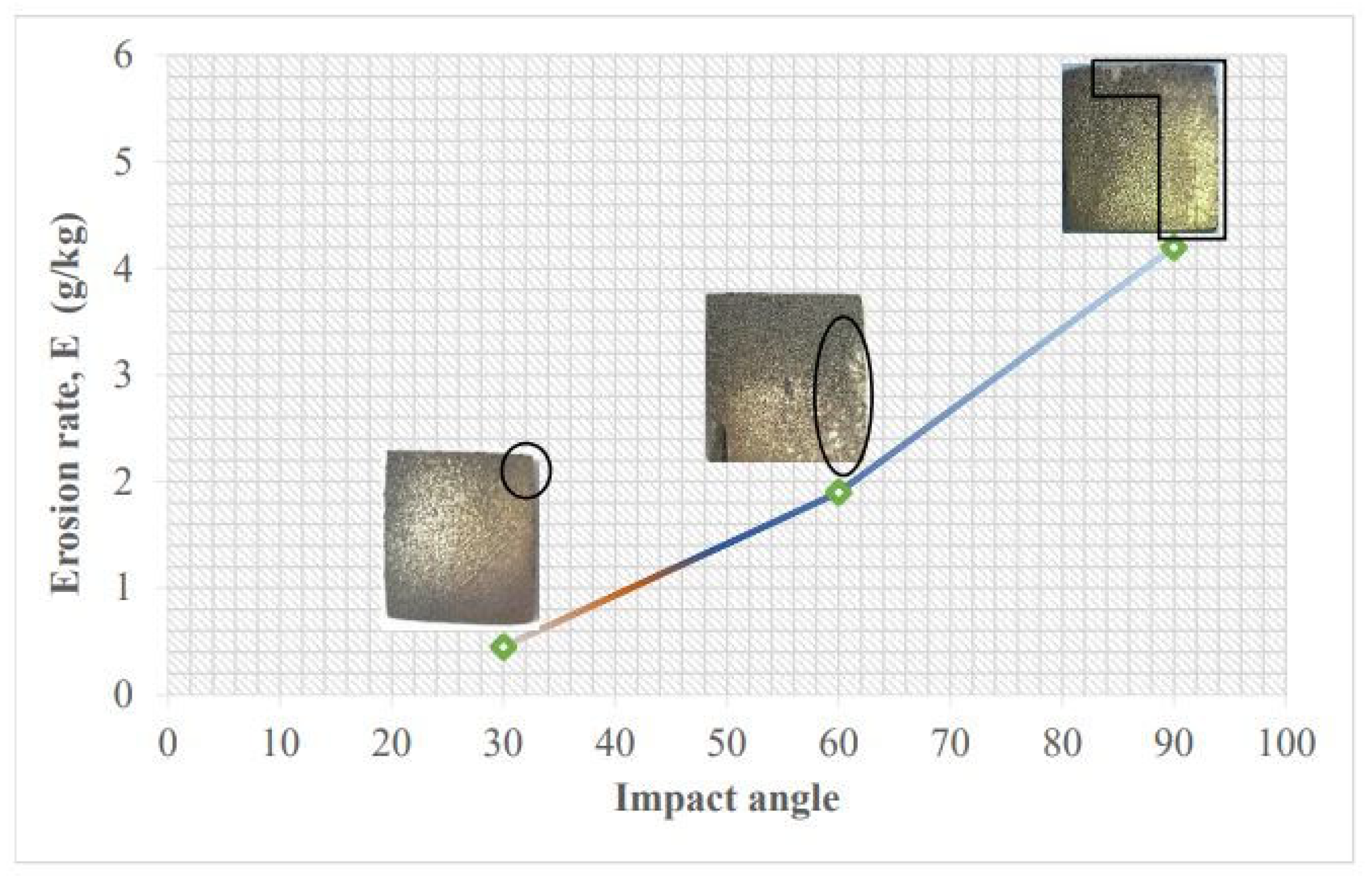

- The SPE test were run at elevated temperature (1050 °C), where silica with size (160-430) µm was use as erodent particles, the total erosion time was 20 min, with a particle feeding rate of 10 g/min. The erosion rate of a TBC was evaluated at 30°, 60°, and 90° impact angle. Results indicate that the flame thermal sprayed coating could protect the substrate at 30°, 60° and 90° impact angles. The coating shows a lower material removal rate by the erosion at an impact angle of 30° compared with 90° which is attributed to the pinning and shielding effect of the WC particles. By SEM investigation it was observed increase reduction in the thickness of TC layer is observed as impact angle increased, while the thickness of BC and substrate maintain same during the SPE test at all impact angles. Moreover, combined erosion mechanism modes (ductile and brittle mode) had been observed in TBC layer after SPE test.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- D. Shin, A. Hamed, Influence of micro–structure on erosion resistance of plasma sprayed 7YSZ thermal barrier coating under gas turbine operating conditions, Wear, Volumes 396–397, 2018, Pages 34-47, ISSN 0043-1648. [CrossRef]

- J. Aust, D. J. Aust, D. Pons, Taxonomy of Gas Turbine Blade Defects. Aerospace. 2019; 6(5):58. [CrossRef]

- Hsiao, Y.-F.; Shiah, Y.-C. Efficient BEM Modeling of the Heat Transfer in the Turbine Blades of Aero-Parts. Aerospace 2023, 10, 885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Cai, J.; Zhu, J. Hot Corrosion Behavior of BaLa2Ti3O10 Thermal Barrier Ceramics in V2O5 and Na2SO4 + V2O5 Molten Salts. Coatings 2019, 9, 351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morad, A. Shash, Y. (2014). NICKEL BASE SUPERALLOYS USED FOR AERO ENGINE TURBINE BLADES. The International Conference on Applied Mechanics and Mechanical Engineering, 16(16th International Conference on Applied Mechanics and Mechanical Engineering.), 1-22. [CrossRef]

- Abdul A., S. A. Khan, Optimization of Heat Transfer on Thermal Barrier Coated Gas Turbine Blade. IOP Conf. Series: Materials Science and Engineering 370 (2018) 012022.

- Yang, Y.; Aprilia, A.; Wu, K.; Tan, S.C.; Zhou, W. Post-Processing of Cold Sprayed CoNiCrAlY Coatings on Inconel 718 by Rapid Induction Heating. Metals 2022, 12, 396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leszek, U. , Andrzej D., Paweł S., Mirosław N., Applying Protective Coating on the Turbine Engine Turbine Blades by Means of Plasma Spraying. Journal of KONBiN. 50. (2020) 193-213. 10.2478/jok-2020-0012.

- Vishnu S., PB. Ramkumar, Deepak S., Doyel J., Jithu J., Abraham K., Optimized Thermal Barrier Coating for Gas Turbine Blades, Materials Today: Proceedings, Volume 11, Part 3, 2019, Pages 912-919, ISSN 2214-7853. [CrossRef]

- F. Fanicchia, D.A. Axinte, J. Kell, R. McIntyre, G. Brewster, A.D. Norton, Combustion Flame Spray of CoNiCrAlY & YSZ coatings, Surface and Coatings Technology, Volume 315, 2017, Pages 546-557, ISSN 0257-8972. [CrossRef]

- Erwin, V. Jonathan S., Robert C., Determination of Turbine Blade Life From Engine Field Data, 49th AIAA/ASME/ASCE/AHS/ASC Structures, Structural Dynamics, and Materials Conference, 07-10 April 2008, Schaumburg, IL. [CrossRef]

- Z. Tang, H. Kim, I. Yaroslavski, G. Masindo, Z. Celler, D. Ellsworth; –29, 2011. "Novel Thermal Barrier Coatings Produced by Axial Suspension Plasma Spray." Proceedings of the ITSC2011. Thermal Spray 2011: Proceedings from the International Thermal Spray Conference. Hamburg, Germany. (pp. pp. 571-575). ASM. 27 September. [CrossRef]

- Baraa, A. Al-Obadie, Ahmed M. Al-Gaban, Hussain M. Yousif; Improving the surface properties of GG25 cast iron using the flame thermal spray technique. AIP Conf. Proc. ; 3051 (1): 070005. 16 February. [CrossRef]

- Venkatachalapathy, V.; Katiyar, N.K.; Matthews, A.; Endrino, J.L.; Goel, S. A Guiding Framework for Process Parameter Optimisation of Thermal Spraying. Coatings 2023, 13, 713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aya, N. , Hussain M., Sura S., Improving the corrosion resistance of low carbon steel by Ni- Cu binary thermal sprayed coating layer. Advances in Mechanics, 2021, 9.3: 853-867. [CrossRef]

- Choudhary, S. , Gaur, V. (2023). Study of New Generation Thermal Barrier Coatings for High-Temperature Applications. In: Verma, A., Sethi, S.K., Ogata, S. (eds) Coating Materials. Materials Horizons: From Nature to Nanomaterials. Springer, Singapore. [CrossRef]

- Rachida, R. , Bachir El K., Fabienne D., Vronique V., Dorian D., Wear Performance of Thermally Sprayed NiCrBSi and NiCrBSi-WC Coatings Under Two Different Wear Modes, J. Mater. Environ. Sci., 2017 Volume 8, Issue 12, Page 4550-4559. [CrossRef]

- S. Rohan, H. Awatef, Sh. Dongyun, W. Nathanial, M. Robert, Deterioration of Thermal Barrier Coated Turbine Blades by Erosion, International Journal of Rotating Machinery, 2012, 601837, 10 pages, 2012. [CrossRef]

- C.S. Ramachandran, V. Balasubramanian, P.V. Ananthapadmanabhan, Erosion of atmospheric plasma sprayed rare earth oxide coatings under air suspended corundum particles, Ceramics International, Volume 39, Issue 1, 2013, Pages 649-672, ISSN 0272-8842. [CrossRef]

- S. Praveen, J. Sarangan, S. Suresh, J. Siva Subramanian, Erosion wear behaviour of plasma sprayed NiCrSiB/Al2O3 composite coating, International Journal of Refractory Metals and Hard Materials, Volume 52, 2015, Pages 209-218, ISSN 0263-4368. [CrossRef]

- S. Mahade, A. Venkat, N. Curry, M. Leitner, S. Joshi, Erosion Performance of Atmospheric Plasma Sprayed Thermal Barrier Coatings with Diverse Porosity Levels. Coatings 2021, 11, 86. [CrossRef]

- M. Murugan, A. Ghoshal, M. J. Walock, B. B. Barnett, M. S. Pepi, and K. A. Kerner, “Sand Particle-Induced deterioration of thermal barrier coatings on gas turbine blades,” Advances in aircraft and spacecraft science, vol. 4, no. 1, pp. 37–52, Jan. 2017. [CrossRef]

- D. G. Bhosale, T. R. Prabhu, W. S. Rathod, M. A. Patil, S. W. Rukhande, High temperature solid particle erosion behaviour of SS 316L and thermal sprayed WC-Cr3C2–Ni coatings, Wear, Volumes 462–463, 2020, 203520, ISSN 0043-1648. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Liu, W.; Li, C. Yan, G.; Wang, Q.; Yang, L.; Zhou, Y., Solid Particle Erosion Behavior of La2Ce2O7/YSZ Double-Ceramic Layer and Traditional YSZ Thermal Barrier Coatings at High Temperature. Coatings 2022, 12, 1638. 2022, 12, 1638. [CrossRef]

- SF. Cernuschi, L. Lorenzoni, S. Capelli, C. Guardamagna, M. Karger, R. Vaßen, K. von Niessen, N. Markocsan, J. 2011; 12. [CrossRef]

- Presby, M.J.; Stokes, J.L.; Harder, B.J.; Lee, K.N.; Hoffman, L.C. High-Temperature Solid Particle Erosion of Environmental and Thermal Barrier Coatings. Coatings 2023, 13, 902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M. Mudhafar, Z. Shihab, Hanaa Al., (2018). Investigation of Ceramic Coating by Thermal Spray with Diffusion of Copper. Acta Physica Polonica A. 134. 248-251. [CrossRef]

- Singh, G. , Kaur, M. & Upadhyaya, R. Wear and Friction Behavior of NiCrBSi Coatings at Elevated Temperatures. J Therm Spray Tech 28, 1081–1102 (2019). [CrossRef]

- G.J.Matrood, A.M. Al-Gaban and H.M. Yousif., “Studying The Erosion Corrosion Behavior of NiCrAlY Coating Layer Applied on AISI 446 Stainless Steel Using Thermal Spray Technique”, Engineering and Technology Journal, Vol. 38, Part A, No. 11, pp. 1676-1683, 2020. [CrossRef]

- K. Yuan, Y. K. Yuan, Y. Yu, J-F. 2017; -80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X. , Deng, Z., Li, H. et al. Al2O3-modified PS-PVD 7YSZ thermal barrier coatings for advanced gas-turbine engines. npj Mater Degrad 4, 31 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Rivellini, K.; Ruggiero, P.; Wildridge, G. Novel Thermal Barrier Coatings with Phase Composite Structures for Extreme Environment Applications: Concept, Process, Evaluation and Performance. Coatings 2023, 13, 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, Sh. , Akash, K.C Anil, J. Kumaraswamy, Solid Particle Erosion Performance of Multi-layered Carbide Coatings (WC-SiC-Cr_3C_2). Evergreen. Vol. 20 June; 10. [CrossRef]

- F. Cernuschi, C. Guardamagna, S. Capelli, L. Lorenzoni, D.E. Mack, A. Moscatelli, Solid particle erosion of standard and advanced thermal barrier coatings, Wear, Volumes 348–349, 2016, Pages 43-51, ISSN 0043-1648. [CrossRef]

- Hasan, Md. F. , Wang, J., & Berndt, C. C. (2013). Effect of Power and Stand-Off Distance on Plasma Sprayed Hydroxyapatite Coatings. Materials and Manufacturing Processes, 28(12), 1279–1285. [CrossRef]

- Bergant, Z. , Grum, J. Quality Improvement of Flame Sprayed, Heat Treated, and Remelted NiCrBSi Coatings. J Therm Spray Tech 18, 380–391 (2009). [CrossRef]

- Fleischer R., Dimiduk D., Lipsitt H., (1989), Intermetallic Compounds for Strong High-Temperature Materials: Status and Potential, Annual Review of Materials Research, 19, Volume 19, 231-263, 1. [CrossRef]

- J.J. Ruan, N. Ueshima, K. Oikawa, Growth behavior of the δ-Ni3Nb phase in superalloy 718 and modified KJMA modeling for the transformation-time-temperature diagram, Journal of Alloys and Compounds, Volume 814, 2020, 152289, ISSN 0925-8388. [CrossRef]

- Günen, A. , Çürük, A. Properties and High-Temperature Wear Behavior of Remelted NiCrBSi Coatings. JOM 72, 673–683 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Bergant, Z.; Batič, B.Š.; Felde, I.; Šturm, R.; Sedlaček, M. Tribological Properties of Solid Solution Strengthened Laser Cladded NiCrBSi/WC-12Co Metal Matrix Composite Coatings. Materials 2022, 15, 342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mengchuan Shi, Zhaolu Xue, Zhenya Zhang, Xiaojuan Ji, Eungsun Byon, Shihong Zhang, Effect of spraying powder characteristics on mechanical and thermal shock properties of plasma-sprayed YSZ thermal barrier coating, Surface and Coatings Technology, Volume 395, 2020, 125913, ISSN 0257-8972. [CrossRef]

- Shuo Wu, Yuantao Zhao, Wenge Li, Weilai Liu, Yanpeng Wu, Fukang Liu; Optimization of process parameters for thermal shock resistance and thermal barrier effects of 8YSZ thermal barrier coatings through orthogonal test. AIP Advances ; 11 (6): 065215. 1 June. [CrossRef]

- Pourbafrani M, Razavi RS, Bakhshi SR, Loghman-Estarki MR, Jamali H. Effect of microstructure and phase of nanostructured YSZ thermal barrier coatings on its thermal shock behaviour. Surface Engineering. 2015;31(1):64-73. [CrossRef]

- Mohd Yunus, S.; Mahalingam, S.; Manap, A.; Mohd Afandi, N.; Satgunam, M. Test-Rig Simulation on Hybrid Thermal Barrier Coating Assisted with Cooling Air System for Advanced Gas Turbine under Prolonged Exposures—A Review. Coatings 2021, 11, 560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahalingam S, Manap A, Yunus SM, Afandi N. Thermal Stability of Rare Earth-PYSZ Thermal Barrier Coating with High-Resolution Transmission Electron Microscopy. Coatings. 2020; 10(12):1206. [CrossRef]

- Muye, N. Qinling B., Lingqian K., Jun Y., Weimin L., A study of Ni3Si-based composite coating fabricated by self-propagating high temperature synthesis casting route, Surface and Coatings Technology, Volume 205, Issues 17–18, 2011, Pages 4249-4253, ISSN 0257-8972. [CrossRef]

- Barwinska, I.; Kopec, M.; Kukla, D.; Senderowski, C.; Kowalewski, Z.L. Thermal Barrier Coatings for High-Temperature Performance of Nickel-Based Superalloys: A Synthetic Review. Coatings 2023, 13, 769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- V. Keerthivasan, S. K. Nitharshana Juvala, S. Neeviha Gayathri, 2019, Study of Coatings used in Gas Turbine Engine, INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF ENGINEERING RESEARCH & TECHNOLOGY (IJERT) CONFCALL – 2019 (Volume 7 – Issue 11).

- Ashofteh, Afshin. (2018). Thermal shock behavior of mixed composite top coat APS TBCs. Ceramics - Silikaty. 62. 1-10. 10.13168/cs.2018.0013.

- Yuexing Zhao, Dachuan Li, Xinghua Zhong, Huayu Zhao, Liang Wang, Fang Shao, Chenguang Liu, Shunyan Tao, Thermal shock behaviors of YSZ thick thermal barrier coatings fabricated by suspension and atmospheric plasma spraying, Surface and Coatings Technology, Volume 249, 2014, Pages 48-55, ISSN 0257-8972. [CrossRef]

- Mahade, S.; Venkat, A.; Curry, N.; Leitner, M.; Joshi, S. Erosion Performance of Atmospheric Plasma Sprayed Thermal Barrier Coatings with Diverse Porosity Levels. Coatings 2021, 11, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, D, & Hamed, A. "Advanced High Temperature Erosion Tunnel for Testing TBC and New Turbine Blade Materials." Proceedings of the ASME Turbo Expo 2016: Turbomachinery Technical Conference and Exposition. Volume 6: Ceramics; Controls, Diagnostics and Instrumentation; Education; Manufacturing Materials and Metallurgy. Seoul, South Korea. –17, 2016. V006T21A011. ASME. 13 June. [CrossRef]

- Bonu, V.; Barshilia, H.C. High-Temperature Solid Particle Erosion of Aerospace Components: Its Mitigation Using Advanced Nanostructured Coating Technologies. Coatings 2022, 12, 1979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Materials | Ni | Cr | Al | Fe | C | Hf | B | Si | W |

| In718 | Base | 10.5 | 0.3 | 0.5 | 16.7 | 0.4 | 1.3 | 0.6 | - |

| NiCrBSi | Base | 14.94 | 0.21 | 3.95 | - | - | - | 5.33 | - |

| Ni based-WC | Base | 3.9 | 0.3 | 2.2 | 11.8 | 0.1 | - | 3.5 | 31.5 |

| Parameter | Code | Level1 | Level2 | Level3 |

| Stand-off distance (mm) | A | 100 | 125 | 150 |

| Traverse Velocity (mm/min) | B | 100 | 200 | 300 |

| Powder Feeding (g/min) | C | 10 | 20 | 30 |

| Code | A | B | C | Trail1 | Trai2 | Trail3 | Mean | S/N |

| 1 | 100 | 100 | 10 | 51 | 53 | 48 | 50.6667 | 34.09 |

| 2 | 100 | 200 | 20 | 66 | 64 | 61 | 63.6667 | 36.08 |

| 3 | 100 | 300 | 30 | 67 | 69 | 67 | 67.6667 | 36.61 |

| 4 | 125 | 100 | 20 | 47 | 48 | 44 | 46.3333 | 33.32 |

| 5 | 125 | 200 | 30 | 55 | 53 | 54 | 54.0000 | 34.65 |

| 6 | 125 | 300 | 10 | 64 | 58 | 60 | 60.6667 | 35.66 |

| 7 | 150 | 100 | 30 | 72 | 71 | 72 | 71.6667 | 37.11 |

| 8 | 150 | 200 | 10 | 66 | 68 | 65 | 66.3333 | 36.43 |

| 9 | 150 | 300 | 20 | 59 | 56 | 61 | 58.6667 | 35.37 |

| Level | A | B | C |

| 1 | 35.59 | 34.84 | 35.40 |

| 2 | 34.54 | 35.72 | 34.92 |

| 3 | 36.30 | 35.88 | 36.12 |

| Delta | 1.76 | 1.04 | 1.20 |

| Rank | 1 | 3 | 2 |

| Source | DF | Seq SS | Adj SS | Adj MS | F | Contribution,% |

| Standoff distance mm | 2 | 4.712 | 4.712 | 2.3561 | 1.26 | 37.64 |

| T. velocity mm/min | 2 | 1.879 | 1.879 | 0.9396 | 0.50 | 15.01 |

| Powder feeding g/min | 2 | 2.189 | 2.189 | 1.0943 | 0.59 | 17.4 |

| Residual Error | 2 | 3.737 | 3.737 | 1.8686 | 29.85 | |

| Total | 8 | 12.517 | 100 |

| Exp. No. | A | B | C | Predicted diffusion depth | Exp. Diffusion depth |

| 1 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 72.4074 | 71.43 |

| 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 72.4074 | 72.01 |

| 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 72.4074 | 72.39 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).