Submitted:

18 March 2025

Posted:

18 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Experimental

2.1. Materials

2.2. Methods

2.2.1. Preparation of 200 mM Bathophenanthroline:DMSO:HCl Solution

2.2.2. Polyclonal IgG Purification. Step I: Preparation of [(batho)x:cationy] Complexes

2.2.3. SDS-PAGE Electrophoresis

2.2.4. Binding Capacity of the [(batho)3: Zn2+] Complex for Impurity Proteins

2.2.5. Bradford Assay of Impurity Proteins

2.2.6. Scanning Electron Microscope Imaging

2.2.7. Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS)

2.2.8. Circular Dichroism (CD) Spectrocopy

3. Results and Discussion

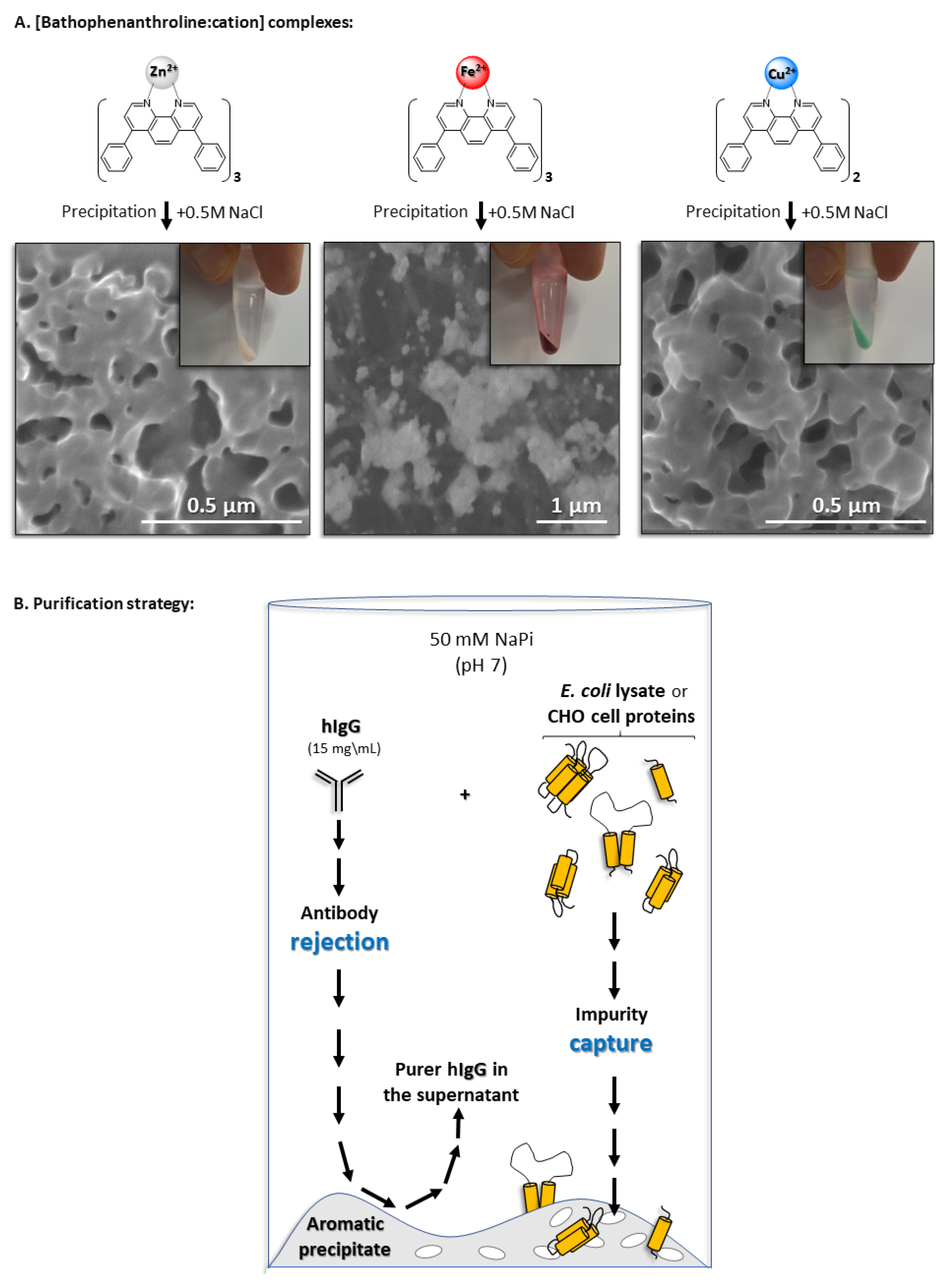

3.1. Complex Precipitation: Morphology

3.2. Comparison of Process Yield for Different Divalent Cations

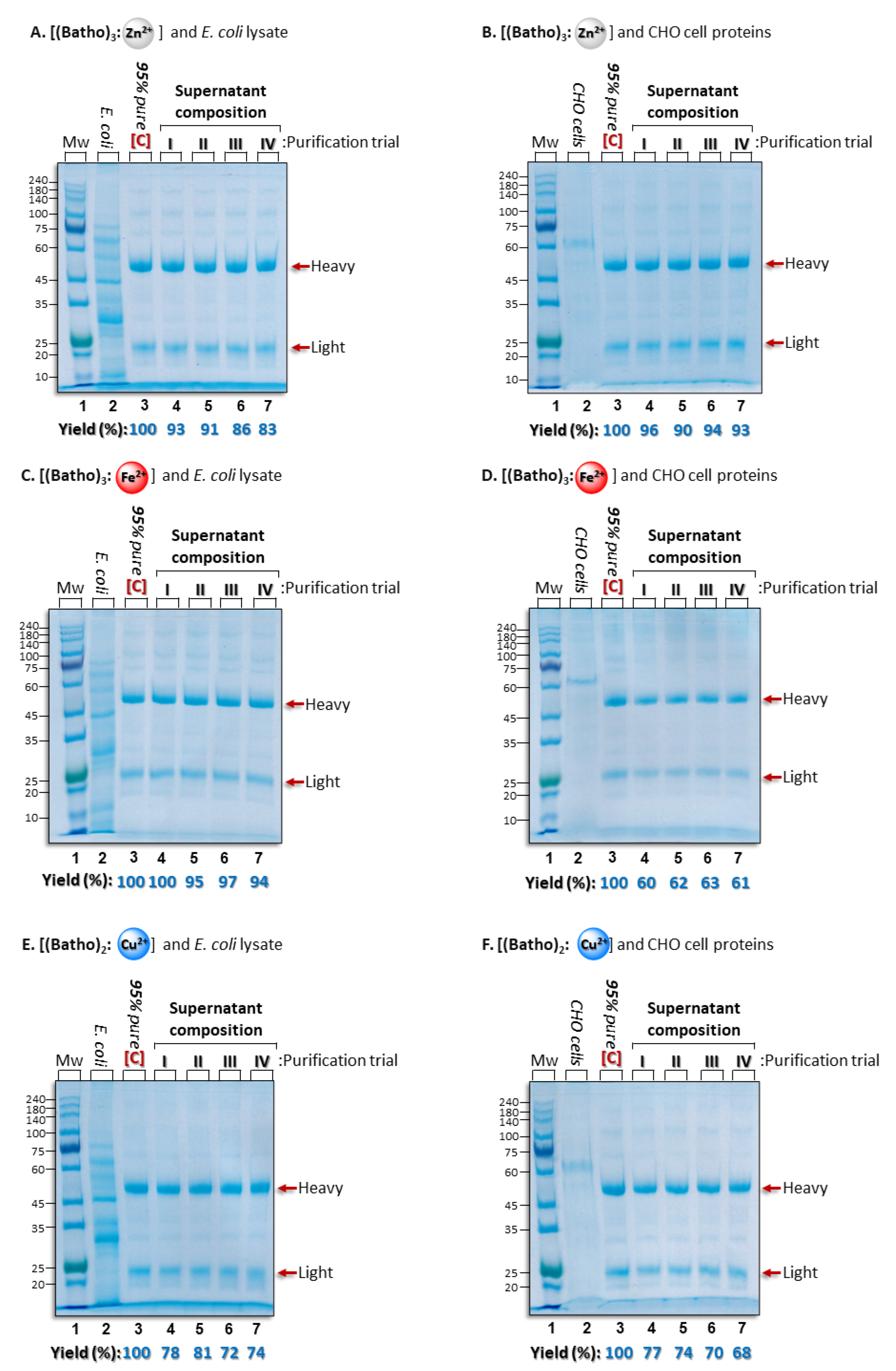

3.3. Binding Capacity for Protein Impurities of [(batho)3:Zn2+] Aromatic complexes

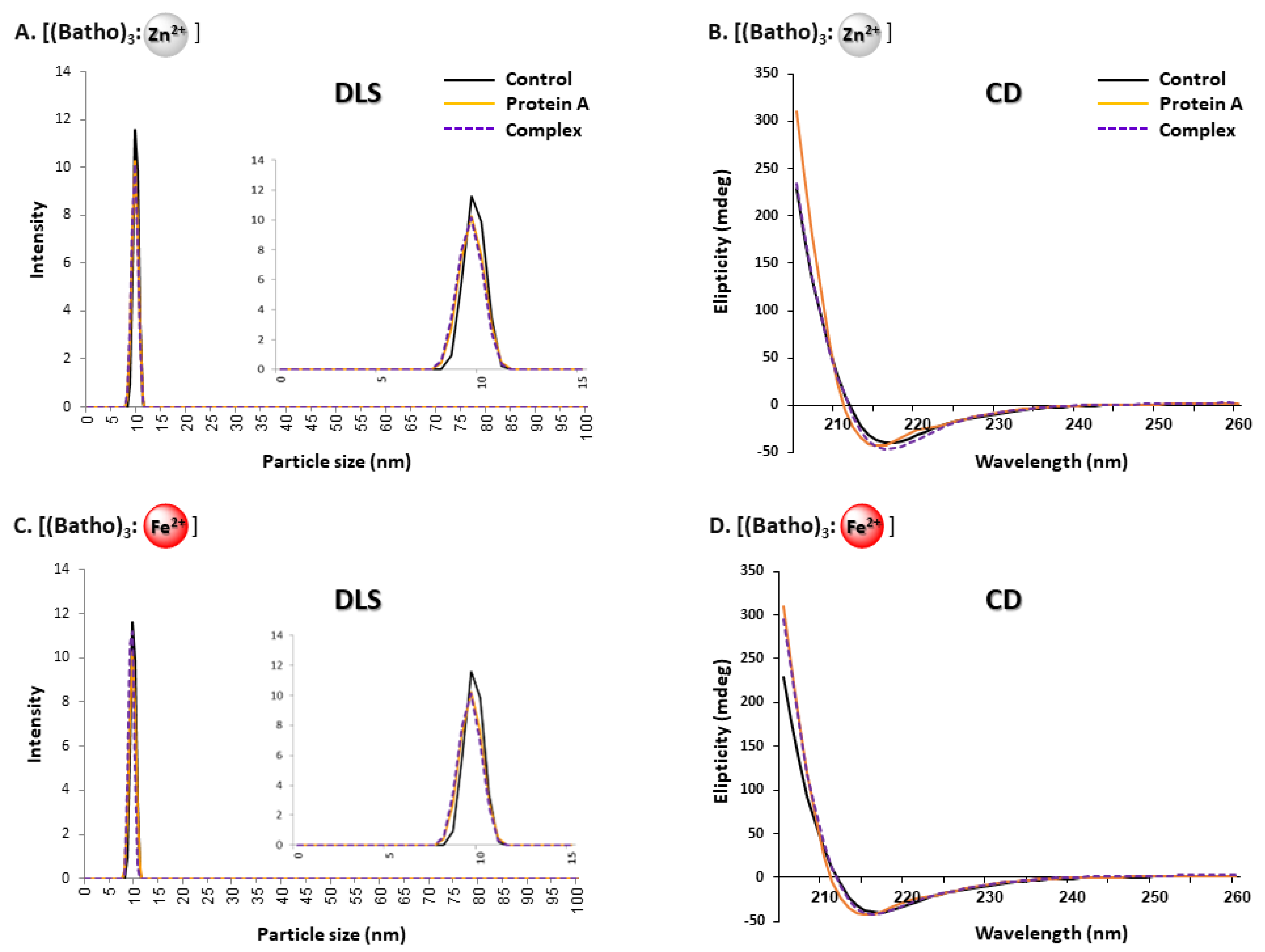

3.4. Native, Non-Aggregated State of hIgG

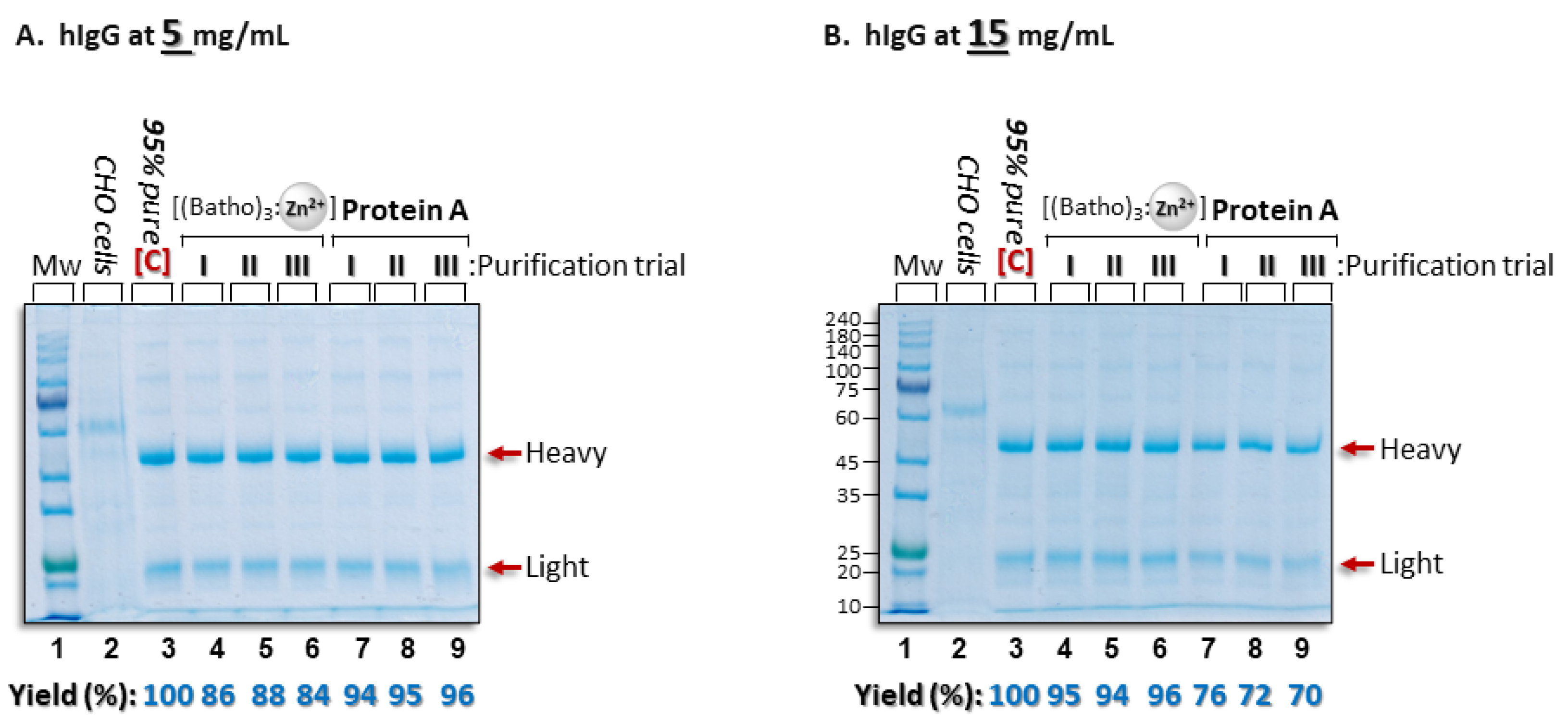

3.5. Comparison of Aromatic Complex Purification and Protein A Chromatography

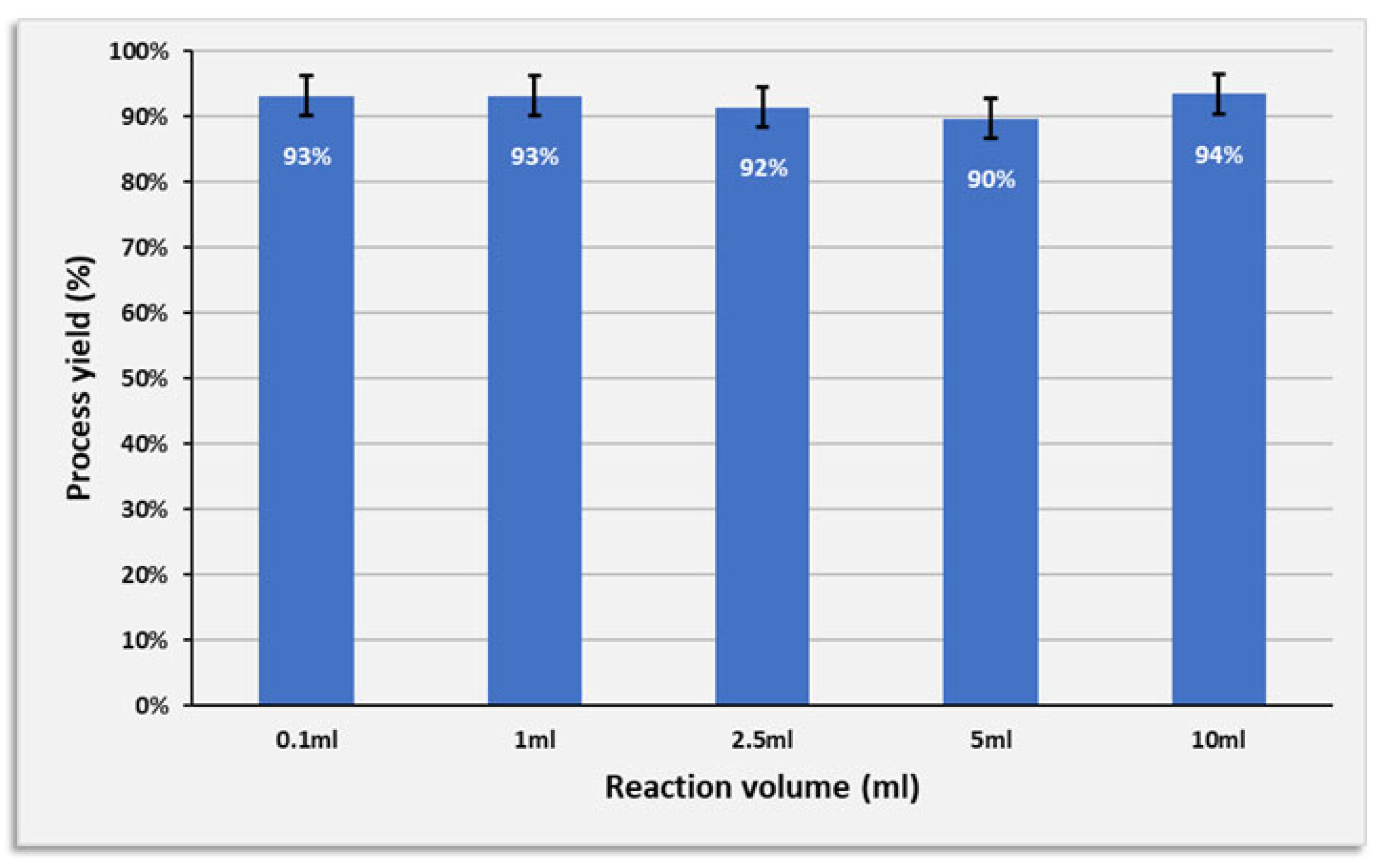

3.6. Increasing the Reaction Volume

4. Conclusions

References

- Jain, E. and A. Kumar, Upstream processes in antibody production: evaluation of critical parameters. Biotechnol Adv, 2008. 26(1): p. 46-72.

- Shukla, A.A. and J. Thömmes, Recent advances in large-scale production of monoclonal antibodies and related proteins. Trends Biotechnol, 2010. 28(5): p. 253-61.

- Elvin, J.G., R.G. Couston, and C.F. van der Walle, Therapeutic antibodies: market considerations, disease targets and bioprocessing. Int J Pharm, 2013. 440(1): p. 83-98.

- Khanal, O. and A.M. Lenhoff, Developments and opportunities in continuous biopharmaceutical manufacturing. mAbs, 2021. 13(1): p. 1903664.

- Kaplon, H., et al., Antibodies to watch in 2022. MAbs, 2022. 14(1): p. 2014296.

- Ghose, S., B. Hubbard, and S.M. Cramer, Binding capacity differences for antibodies and Fc-fusion proteins on protein A chromatographic materials. Biotechnol Bioeng, 2007. 96(4): p. 768-79.

- Kelley, B., Industrialization of mAb production technology: the bioprocessing industry at a crossroads. MAbs, 2009. 1(5): p. 443-52.

- Li, F., et al., Cell culture processes for monoclonal antibody production. MAbs, 2010. 2(5): p. 466-79.

- Huang, Y.M., et al., Maximizing productivity of CHO cell-based fed-batch culture using chemically defined media conditions and typical manufacturing equipment. Biotechnol Prog, 2010. 26(5): p. 1400-10.

- Natarajan, V. and A.L. Zydney, Protein A chromatography at high titers. Biotechnol Bioeng, 2013. 110(9): p. 2445-51.

- Chon, J.H. and G. Zarbis-Papastoitsis, Advances in the production and downstream processing of antibodies. N Biotechnol, 2011. 28(5): p. 458-63.

- Butler, M. and A. Meneses-Acosta, Recent advances in technology supporting biopharmaceutical production from mammalian cells. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol, 2012. 96(4): p. 885-94.

- Yavorsky, D.P., et al., The clarification of bioreactor cell cultures for biopharmaceuticals. Pharmaceutical technology, 2003. 27: p. 62-76.

- Liu, H.F., et al., Recovery and purification process development for monoclonal antibody production. MAbs, 2010. 2(5): p. 480-99.

- Gavara, P.R., et al., Chromatographic Characterization and Process Performance of Column-Packed Anion Exchange Fibrous Adsorbents for High Throughput and High Capacity Bioseparations. Processes, 2015. 3(1): p. 204-221.

- Yang, W.C., et al., Concentrated fed-batch cell culture increases manufacturing capacity without additional volumetric capacity. Journal of Biotechnology, 2016. 217: p. 1-11.

- Wang, M., G. Buist, and J.M. van Dijl, Staphylococcus aureus cell wall maintenance - the multifaceted roles of peptidoglycan hydrolases in bacterial growth, fitness, and virulence. FEMS Microbiol Rev, 2022. 46(5).

- Vidarsson, G., G. Dekkers, and T. Rispens, IgG subclasses and allotypes: from structure to effector functions. Front Immunol, 2014. 5: p. 520.

- DeLano, W.L., et al., Convergent solutions to binding at a protein-protein interface. Science, 2000. 287(5456): p. 1279-83.

- Follman, D.K. and R.L. Fahrner, Factorial screening of antibody purification processes using three chromatography steps without protein A. J Chromatogr A, 2004. 1024(1-2): p. 79-85.

- Valdés, R., et al., Chromatographic removal combined with heat, acid and chaotropic inactivation of four model viruses. J Biotechnol, 2002. 96(3): p. 251-8.

- Brorson, K., et al., Identification of protein A media performance attributes that can be monitored as surrogates for retrovirus clearance during extended re-use. J Chromatogr A, 2003. 989(1): p. 155-63.

- Butler, M.D., B. Kluck, and T. Bentley, DNA spike studies for demonstrating improved clearance on chromatographic media. J Chromatogr A, 2009. 1216(41): p. 6938-45.

- Tarrant, R.D., et al., Host cell protein adsorption characteristics during protein A chromatography. Biotechnol Prog, 2012. 28(4): p. 1037-44.

- Shukla, A.A. and P. Hinckley, Host cell protein clearance during protein A chromatography: development of an improved column wash step. Biotechnol Prog, 2008. 24(5): p. 1115-21.

- Linhult, M., et al., Improving the tolerance of a protein a analogue to repeated alkaline exposures using a bypass mutagenesis approach. Proteins, 2004. 55(2): p. 407-16.

- Hari, S.B., et al., Acid-induced aggregation of human monoclonal IgG1 and IgG2: molecular mechanism and the effect of solution composition. Biochemistry, 2010. 49(43): p. 9328-38.

- Bansal, R., S. Gupta, and A.S. Rathore, Analytical Platform for Monitoring Aggregation of Monoclonal Antibody Therapeutics. Pharm Res, 2019. 36(11): p. 152.

- Paul, A.J., K. Schwab, and F. Hesse, Direct analysis of mAb aggregates in mammalian cell culture supernatant. BMC Biotechnol, 2014. 14: p. 99.

- Zhang, J., et al., Maximizing the functional lifetime of Protein A resins. Biotechnol Prog, 2017. 33(3): p. 708-715.

- McDonald, P., et al., Selective antibody precipitation using polyelectrolytes: a novel approach to the purification of monoclonal antibodies. Biotechnol Bioeng, 2009. 102(4): p. 1141-51.

- Azevedo, A.M., et al., Chromatography-free recovery of biopharmaceuticals through aqueous two-phase processing. Trends Biotechnol, 2009. 27(4): p. 240-7.

- Mao, L.N., et al., Downstream antibody purification using aqueous two-phase extraction. Biotechnol Prog, 2010. 26(6): p. 1662-70.

- van Reis, R. and A. Zydney, Bioprocess membrane technology. Journal of Membrane Science, 2007. 297(1–2): p. 16-50.

- Zheng, X., et al., Enrichment of IgG and HRP glycoprotein by dipeptide-based polymeric material. Talanta, 2022. 241: p. 123223.

- Dhandapani, G., E. Wachtel, and G. Patchornik, Conjugated surfactant micelles: A non-denaturing purification platform for concentrated human immunoglobulin G. Nano Select, 2023. 4(6): p. 386-394.

- Withanage, T.J., et al., Conjugated Nonionic Detergent Micelles: An Efficient Purification Platform for Dimeric Human Immunoglobulin A. ACS Med Chem Lett, 2024. 15(6): p. 979-986.

- Dhandapani, G., et al., Conjugated detergent micelles as a platform for IgM purification. Biotechnol Bioeng, 2022. 119(7): p. 1997-2003.

- Dhandapani, G., et al., A general platform for antibody purification utilizing engineered-micelles. MAbs, 2019. 11(3): p. 583-592.

- Withanage, T.J., et al., The [(bathophenanthroline)(3):Fe(2+)] complex as an aromatic non-polymeric medium for purification of human lactoferrin. J Chromatogr A, 2024. 1732: p. 465218.

- Noy-Porat, T., et al., Acetylcholinesterase-Fc Fusion Protein (AChE-Fc): A Novel Potential Organophosphate Bioscavenger with Extended Plasma Half-Life. Bioconjug Chem, 2015. 26(8): p. 1753-8.

- Shafferman, A., et al., Electrostatic attraction by surface charge does not contribute to the catalytic efficiency of acetylcholinesterase. Embo j, 1994. 13(15): p. 3448-55.

- Dhandapani, G., et al., Purification of antibody fragments via interaction with detergent micellar aggregates. Sci Rep, 2021. 11(1): p. 11697.

- Perry, R.D. and C.L.S. Clemente, Determination of iron with bathophenanthroline following an improved procedure for reduction of iron(III) ions. Analyst, 1977. 102(1211): p. 114-119.

- O'Laughlin, J.W., Separation of cationic metal chelates of 1,10-phenanthroline by liquid chromatography. Analytical Chemistry, 1982. 54(2): p. 178-181.

- Ng, N.S., et al., The antimicrobial efficacy and DNA binding activity of the copper(II) complexes of 3,4,7,8-tetramethyl-1,10-phenanthroline, 4,7-diphenyl-1,10-phenanthroline and 1,2-diaminocyclohexane. J Inorg Biochem, 2016. 162: p. 62-72.

- Zhang, J.H., et al., Strategies and Considerations for Improving Recombinant Antibody Production and Quality in Chinese Hamster Ovary Cells. Front Bioeng Biotechnol, 2022. 10: p. 856049.

- Kelley, B., Developing therapeutic monoclonal antibodies at pandemic pace. Nature Biotechnology, 2020. 38(5): p. 540-545.

- Rashid, M.H., Full-length recombinant antibodies from Escherichia coli: production, characterization, effector function (Fc) engineering, and clinical evaluation. MAbs, 2022. 14(1): p. 2111748.

- Cain, P., et al., Impact of IgG subclass on monoclonal antibody developability. mAbs, 2023. 15(1): p. 2191302.

- Dhandapani, G., et al., Role of amphiphilic [metal:chelator] complexes in a non-chromatographic antibody purification platform. J Chromatogr B Analyt Technol Biomed Life Sci, 2019. 1133: p. 121830.

- Dhandapani, G., et al., Nonionic detergent micelle aggregates: An economical alternative to protein A chromatography. N Biotechnol, 2021. 61: p. 90-98.

- Bruque, M.G., et al., Analysis of the Structure of 14 Therapeutic Antibodies Using Circular Dichroism Spectroscopy. Analytical Chemistry, 2024. 96(38): p. 15151-15159.

- Greenfield, N.J., Using circular dichroism spectra to estimate protein secondary structure. Nat Protoc, 2006. 1(6): p. 2876-90.

- Buyel, J.F., R.M. Twyman, and R. Fischer, Very-large-scale production of antibodies in plants: The biologization of manufacturing. Biotechnology Advances, 2017. 35(4): p. 458-465.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).