Submitted:

17 March 2025

Posted:

18 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Video Assays

2.2. Fly Culture and Strains

2.3. Generation of Multi-Copy Strains

2.4. Cameras and Filters

2.5. Vials, Media and Fly Handling for Video Assays

2.6. In Vivo Bortezomib Treatment

2.7. In Vivo Cycloheximide Treatment

2.8. Microscope Image Capture Assay and Statistical Analysis

2.9. In Vitro Proteasome Assay

2.10. Generation of Partially Purified eGFP Extract

2.11. Video Analysis Software and Statistical Analysis

3. Results

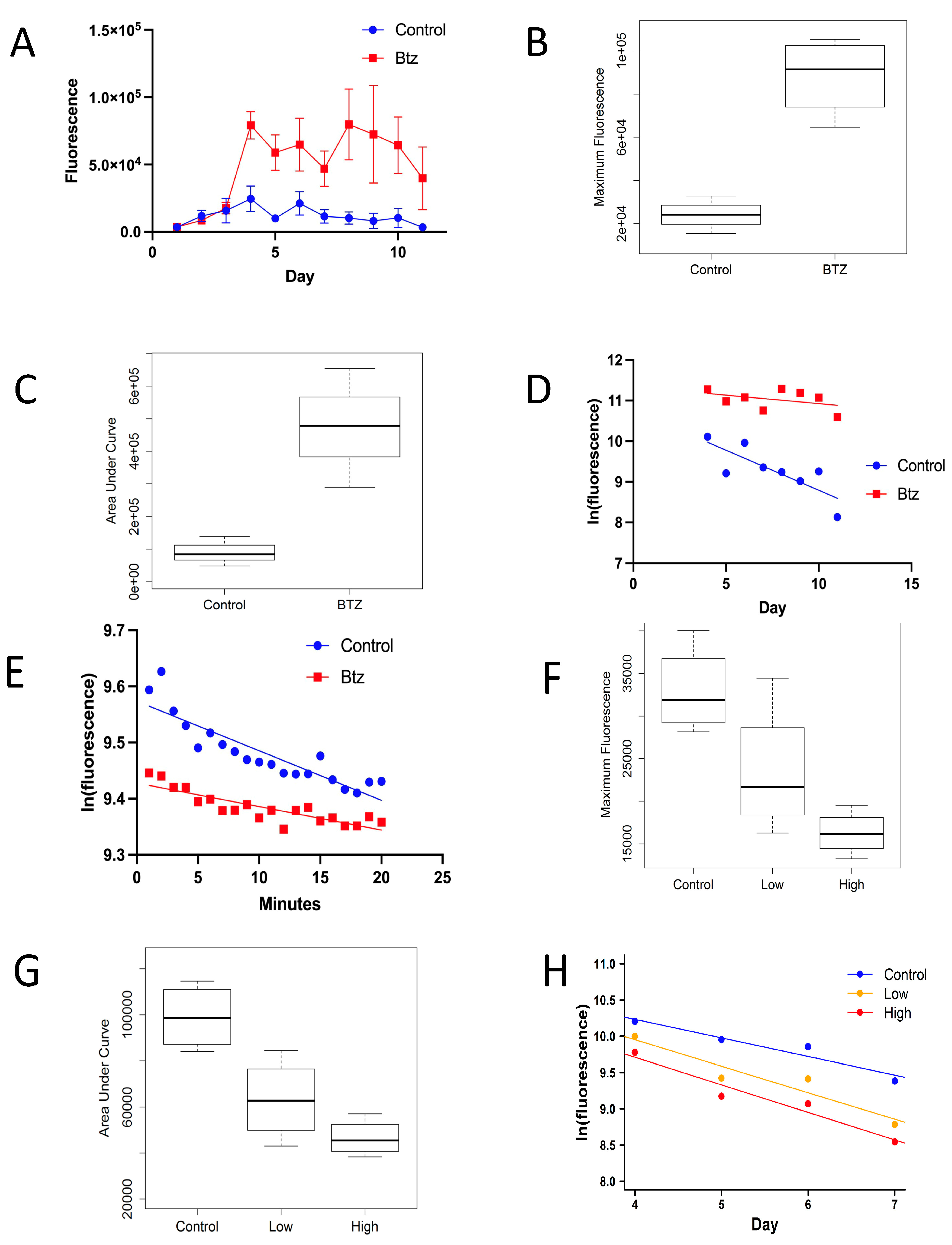

3.1. Bortezomib Increases eGFP Half-Life In Vivo and In Vitro

3.2. Cycloheximide Decreases eGFP Expression In Vivo

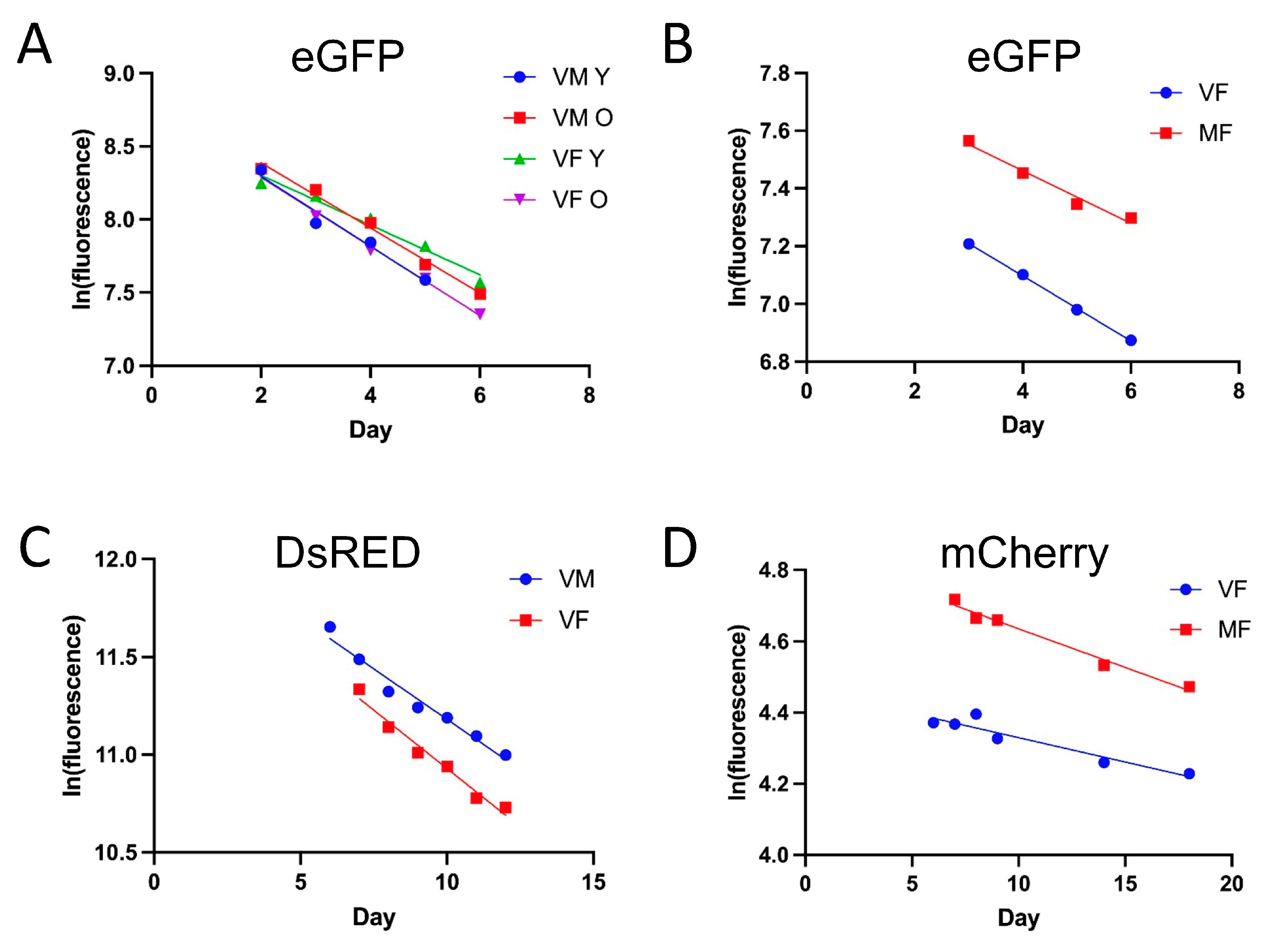

3.3. Half-Life Values of Different Fluorescent Proteins

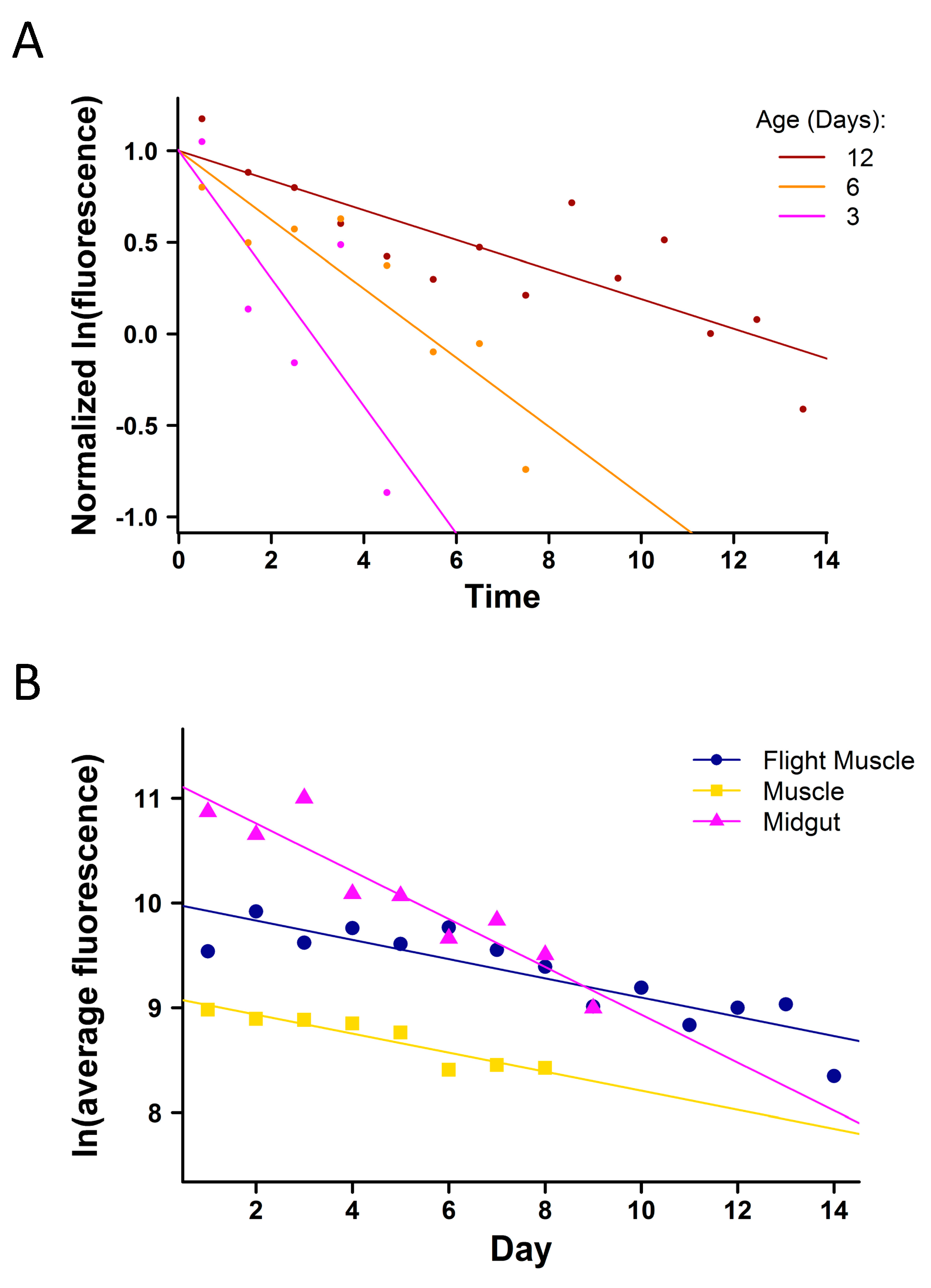

3.4. Tissue-Specific Expression of eGFP

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| eGFP | enhanced green fluorescent protein |

| DsRED | Discosoma species red fluorescent protein |

| LED | light emitting diode |

| COX8 | cytochrome c oxidase subunit 8 |

| UAS | upstream activating sequence |

| GS | Gene-Switch |

| rtTA | reverse tetracycline trans-activator |

| tetO | Tet operator |

References

- Bell, H.S.; Tower, J. In vivo assay and modelling of protein and mitochondrial turnover during aging. Fly (Austin) 2021, 15, 60–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nicholson, L.; Singh, G.K.; Osterwalder, T.; Roman, G.W.; Davis, R.L.; Keshishian, H. Spatial and temporal control of gene expression in Drosophila using the inducible GeneSwitch GAL4 system. I. Screen for larval nervous system drivers. Genetics 2008, 178, 215–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osterwalder, T.; Yoon, K.S.; White, B.H.; Keshishian, H. A conditional tissue-specific transgene expression system using inducible GAL4. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2001, 98, 12596–12601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ford, D.; Hoe, N.; Landis, G.N.; Tozer, K.; Luu, A.; Bhole, D.; Badrinath, A.; Tower, J. Alteration of Drosophila life span using conditional, tissue-specific expression of transgenes triggered by doxycyline or RU486/Mifepristone. Exp Gerontol 2007, 42, 483–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bieschke, E.T.; Wheeler, J.C.; Tower, J. Doxycycline-induced transgene expression during Drosophila development and aging. Molecular & general genetics : MGG 1998, 258, 571–579. [Google Scholar]

- Trauth, J.; Scheffer, J.; Hasenjager, S.; Taxis, C. Strategies to investigate protein turnover with fluorescent protein reporters in eukaryotic organisms. AIMS Biophysics 2020, 7, 90–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sala, A.J.; Bott, L.C.; Morimoto, R.I. Shaping proteostasis at the cellular, tissue, and organismal level. J Cell Biol 2017, 216, 1231–1241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, J.; Demontis, F. Skeletal muscle autophagy and its role in sarcopenia and organismal aging. Curr Opin Pharmacol 2017, 34, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hetz, C. Adapting the proteostasis capacity to sustain brain healthspan. Cell 2021, 184, 1545–1560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ardekani, R.; Huang, Y.M.; Sancheti, P.; Stanciauskas, R.; Tavare, S.; Tower, J. Using GFP Video to Track 3D Movement and Conditional Gene Expression in Free-Moving Flies. PLoS One 2012, 7, e40506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, C.; Finkel, S.E.; Tower, J. Conditional inhibition of autophagy genes in adult Drosophila impairs immunity without compromising longevity. Exp Gerontol 2009, 44, 228–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jacobs, J.A.; Sehgal, A. Anandamide Metabolites Protect against Seizures through the TRP Channel Water Witch in Drosophila melanogaster. Cell reports 2020, 31, 107710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luis, N.M.; Wang, L.; Ortega, M.; Deng, H.; Katewa, S.D.; Li, P.W.; Karpac, J.; Jasper, H.; Kapahi, P. Intestinal IRE1 Is Required for Increased Triglyceride Metabolism and Longer Lifespan under Dietary Restriction. Cell reports 2016, 17, 1207–1216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mlih, M.; Khericha, M.; Birdwell, C.; West, A.P.; Karpac, J. A virus-acquired host cytokine controls systemic aging by antagonizing apoptosis. PLoS Biol 2018, 16, e2005796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horn, C.; Jaunich, B.; Wimmer, E.A. Highly sensitive, fluorescent transformation marker for Drosophila transgenesis. Dev Genes Evol 2000, 210, 623–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tower, J.; Agrawal, S.; Alagappan, M.P.; Bell, H.S.; Demeter, M.; Havanoor, N.; Hegde, V.S.; Jia, Y.; Kothawade, S.; Lin, X.; et al. Behavioral and molecular markers of death in Drosophila melanogaster. Exp Gerontol 2019, 126, 110707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laker, R.C.; Xu, P.; Ryall, K.A.; Sujkowski, A.; Kenwood, B.M.; Chain, K.H.; Zhang, M.; Royal, M.A.; Hoehn, K.L.; Driscoll, M.; et al. A novel MitoTimer reporter gene for mitochondrial content, structure, stress, and damage in vivo. J Biol Chem 2014, 289, 12005–12015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, P.; Damschroder, D.; Zhang, M.; Ryall, K.A.; Adler, P.N.; Saucerman, J.J.; Wessells, R.J.; Yan, Z. Atg2, Atg9 and Atg18 in mitochondrial integrity, cardiac function and healthspan in Drosophila. J Mol Cell Cardiol 2019, 127, 116–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, C.; Webster, P.; Finkel, S.E.; Tower, J. Increased internal and external bacterial load during Drosophila aging without life-span trade-off. Cell Metab 2007, 6, 144–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Tower, J. Expression of hsp22 and hsp70 transgenes is partially predictive of drosophila survival under normal and stress conditions. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2009, 64, 828–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoe, N.; Huang, C.M.; Landis, G.; Verhage, M.; Ford, D.; Yang, J.; van Leeuwen, F.W.; Tower, J. Ubiquitin over-expression phenotypes and ubiquitin gene molecular misreading during aging in Drosophila melanogaster. Aging (Albany NY) 2011, 3, 237–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robertson, H.M.; Preston, C.R.; Phillis, R.W.; Johnson-Schlitz, D.M.; Benz, W.K.; Engels, W.R. A stable genomic source of P element transposase in Drosophila melanogaster. Genetics 1988, 118, 461–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cox, R.T.; Spradling, A.C. A Balbiani body and the fusome mediate mitochondrial inheritance during Drosophila oogenesis. Development 2003, 130, 1579–1590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pickering, A.M.; Staab, T.A.; Tower, J.; Sieburth, D.S.; Davies, K.J. A conserved role for the 20S proteasome and Nrf2 transcription factor in oxidative-stress adaptation in mammals, C. elegans and D. melanogaster. J Exp Biol 2012. [CrossRef]

- Pomatto, L.C.; Carney, C.; Shen, B.; Wong, S.; Halaszynski, K.; Salomon, M.P.; Davies, K.J.; Tower, J. The Mitochondrial Lon Protease Is Required for Age-Specific and Sex-Specific Adaptation to Oxidative Stress. Curr Biol 2017, 27, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, C.R.C.; Abdul-Majeed, S.; Cael, B.; Barta, S.K. Clinical Pharmacokinetics and Pharmacodynamics of Bortezomib. Clin Pharmacokinet 2019, 58, 157–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferree, A.W.; Trudeau, K.; Zik, E.; Benador, I.Y.; Twig, G.; Gottlieb, R.A.; Shirihai, O.S. MitoTimer probe reveals the impact of autophagy, fusion, and motility on subcellular distribution of young and old mitochondrial protein and on relative mitochondrial protein age. Autophagy 2013, 9, 1887–1896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rolfs, Z.; Frey, B.L.; Shi, X.; Kawai, Y.; Smith, L.M.; Welham, N.V. An atlas of protein turnover rates in mouse tissues. Nature communications 2021, 12, 6778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McClatchy, D.B.; Martinez-Bartolome, S.; Gao, Y.; Lavallee-Adam, M.; Yates, J.R., 3rd. Quantitative analysis of global protein stability rates in tissues. Scientific reports 2020, 10, 15983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neznanov, N.; Komarov, A.P.; Neznanova, L.; Stanhope-Baker, P.; Gudkov, A.V. Proteotoxic stress targeted therapy (PSTT): induction of protein misfolding enhances the antitumor effect of the proteasome inhibitor bortezomib. Oncotarget 2011, 2, 209–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dantuma, N.P.; Lindsten, K.; Glas, R.; Jellne, M.; Masucci, M.G. Short-lived green fluorescent proteins for quantifying ubiquitin/proteasome-dependent proteolysis in living cells. Nat Biotechnol 2000, 18, 538–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verkhusha, V.V.; Kuznetsova, I.M.; Stepanenko, O.V.; Zaraisky, A.G.; Shavlovsky, M.M.; Turoverov, K.K.; Uversky, V.N. High stability of Discosoma DsRed as compared to Aequorea EGFP. Biochemistry 2003, 42, 7879–7884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wheeler, J.C.; Bieschke, E.T.; Tower, J. Muscle-specific expression of Drosophila hsp70 in response to aging and oxidative stress. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1995, 92, 10408–10412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wheeler, J.C.; King, V.; Tower, J. Sequence requirements for upregulated expression of Drosophila hsp70 transgenes during aging. Neurobiol Aging 1999, 20, 545–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demontis, F.; Piccirillo, R.; Goldberg, A.L.; Perrimon, N. Mechanisms of skeletal muscle aging: insights from Drosophila and mammalian models. Dis Model Mech 2013, 6, 1339–1352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Landis, G.N.; Salomon, M.P.; Keroles, D.; Brookes, N.; Sekimura, T.; Tower, J. The progesterone antagonist mifepristone/RU486 blocks the negative effect on life span caused by mating in female Drosophila. Aging (Albany NY) 2015, 7, 53–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landis, G.N.; Hilsabeck, T.A.U.; Bell, H.S.; Ronnen-Oron, T.; Wang, L.; Doherty, D.V.; Tejawinata, F.I.; Erickson, K.; Vu, W.; Promislow, D.E.L.; et al. Mifepristone Increases Life Span of Virgin Female Drosophila on Regular and High-fat Diet Without Reducing Food Intake. Frontiers in genetics 2021, 12, 751647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tower, J.; Landis, G.N.; Shen, J.; Choi, R.; Fan, Y.; Lee, D.; Song, J. Mifepristone/RU486 acts in Drosophila melanogaster females to counteract the life span-shortening and pro-inflammatory effects of male Sex Peptide. Biogerontology 2017, 18, 413–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).