1. Introduction

We have a good knowledge of the 26S proteasome structure (Dong et al., 2019; Greene et al., 2020; Groll et al., 1997). The 26S proteasome is formed by assembling two different protein complexes, a 20S catalytic core particle (20S CP) and the 19S regulatory particle (19S RP). Each of these particles assembled independently but in the context of the 26S proteasomes are subjected to mutual allosteric regulation (Coffino & Cheng, 2022). In addition to 19S RP, alternative complexes including PA200 (PSME4) and 11S PA28 are associated with 20S CP (Stadtmueller & Hill, 2011). The 20S CP is built of two copies of seven different alpha (PSMA1 to 7) and seven different beta (PSMB1 to 7) subunits, each organized to form a ring shape. The two interior beta rings are flanked by the alpha rings in forming a cylindrical chamber (Groll et al., 1997). The beta rings are endowed with proteolytic cleavage specificities categorized as trypsin-like (PSMB7), chymotrypsin-like (PSMB5), and caspase-like (PSMB6) (Greene et al., 2020). The PSMA flexible N-terminal regions form the gate that controls the access of substrates to the chamber (Groll et al., 1997, 2000; Religa et al., 2010).

The multi-PSMD subunit 19S RP caps one or both ends of the 20S CP. The 19S RP docking is ATP-dependent but can be substituted with NADH (Tsvetkov et al., 2014). In the latter case, there is a preference for the degradation of intrinsically disordered proteins (Tsvetkov et al., 2020). The 19S RP recognizes ubiquitinated substrates, is active in their deubiquitination, and enhances substrate accessibility into the 20S CP in an ATP hydrolysis-dependent manner. The 19S RP is further subdivided into the base and lid subcomplexes (Glickman, Rubin, Coux, et al., 1998; Glickman, Rubin, Fried, et al., 1998). Several proteasome-dedicated chaperones regulate 26S proteasome assembly (Gu & Enenkel, 2014) and activation (Goldberg et al., 2021). Knockdown of one of the 19S RP subunits gives rise to the accumulation of either free 20S CP, or in complex with some alternative caps (Sahu et al., 2021; Tsvetkov et al., 2018; Welk et al., 2016).

Proteasomes are localized in the cytoplasm and the nuclei of animal cells. The difficulty in determining proteasome subcellular localization merged from the proteasome tendency to reprogram their subcellular localization in response to growth conditions and hostile environment (Enenkel et al., 2022; Wójcik & DeMartino, 2003). In response to osmotic stress specific nuclear proteasomal condensates, containing active proteasomes and polyubiquitinated proteins, have been recently described (Yasuda et al., 2020). These nuclear proteasomal condensates or granules exhibit characteristics of liquid-liquid phase separation.

Several methods were developed to visualize proteasomes in animal cells, such as the utilization of antibodies for immunofluorescent assay or overexpression of fluorescently-tagged proteasome subunits (Gan et al., 2019). Lately, mostly thanks to the CRISPR technology, the endogenous proteasome subunit can be fluorescently tagged. We have reported the generation of PSMB6-YFP, one of the beta ring subunits (Reuven et al., 2021; Tsvetkov et al., 2018). PSMB2–eGFP or PSMB2-Fusion Red-KI HCT116 cells were generated and used for time-lapse imaging of the 20S CP in the cells (Yasuda et al., 2020). This group also employed PSMD6–eGFP to visualize the 19S RP. For 26S proteasome visualization, the cells need to be tagged at both; a subunit of the 20S CP and the 19S RP. This is critical to monitor the 26S/20S ratio. We established double-tagged HeLa cells co-expressing PSMB6-YFP and PSMD6-mScarlet to time-lapse imaging of the 20S and 19S particles at the single-cell resolution. We found that the vast majority of the 20S CP are 19S RP capped.

The proteasome granules formed in the nuclei in response to osmotic stress are all YFP and mScarlet positive suggesting they are made of 26S proteasome. Interestingly under PSMD1 knockout, the “free” 20S CP remained nuclear whereas the 19S RP was accumulated in the cytoplasm. The subcellular segregation of the two major proteasome components was also observed when the PSMA3 C-terminus was truncated, suggesting that the 20S CP regulates its capping. The double-tagged proteasome cell line is of choice in investigating 26S proteasome assembly in animal cells.

2. Materials and Methods

Cell culture.

The generation of the HEK293 PSMB6-YFP cell line was previously reported by us (Reuven et al., 2021; Tsvetkov et al., 2018). The G3BP1-mCherry construct was a gift from E. Hornstein and originated in N. Kedersha and P. Anderson (Harvard Medical School, USA). The pFIRES puro plasmid was a gift from C. Kahana and originated in S. Hobbs (Hobbs et al., 1998).

Cells were grown at 37◦C in a humidified incubator with 5% CO2 in high-glucose Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM; GIBCO, Life Technologies, Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) supplemented with 8% fetal bovine serum (GIBCO), and 100 units/mL penicillin, and 100μg/mL streptomycin (Biological Industries).

Materials

Paraformaldehyde and poly-D-lysine hydrobromide, polybrene, and sodium (meta) arsenite were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. jetOPTIMUS® was purchased from Polyplus. PEI MAX® was purchased from Polysciences. NEBuilder® HiFi DNA Assembly Cloning Kit was purchased from BioLabs. Hoechst was purchased from Molecular Probes.

Immunoblot

Immunoblots were performed as previously described (Levy et al., 2007) using RIPA buffer (50mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5, 150mM NaCl, 1% Nonidet P-40 (v/v), 0.5% deoxycholate (v/v), 0.1% SDS (w/v)) supplemented with cocktails of protease inhibitors (Apex Bio). Antibodies used were monoclonal anti-β-actin, polyclonal anti-PSMD6 (ab155761, Abcam), monoclonal anti-RFPs (6G6, ChromoTek), and the polyclonal Living Colors antibody (Clontech) (to detect YFP). Detection by Living Colors antibody and by psmd6 antibody was more sensitive if the samples were not boiled before separation by SDS–PAGE.

Lentivector preparation and transduction

Lentiviruses were produced as described (Cohen et al., 2010) for the expression of G3BP-mCherry. For transduction, medium containing lentivirions was filtered through a 0.45 µM filter and supplemented with polybrene (8 μg/ml), and added to the cells for ~16 hours. The transduced cells were washed with warm PBS 3 times, and a fresh medium containing 10µg/ml Blasticidin was added to the cells for selection. After 5 days cells were sorted with FACSAriaIII (BD Biosciences) according to the mCherry fluorescence intensity.

Establishment of tagged-proteasome cell lines

The establishment of the heterozygous HeLa and HEK293 PSMB6-SYFP edited cell lines were previously reported (Reuven et al., 2019; Tsvetkov et al., 2018). To establish cell lines expressing tagged 19S RP, for expressing both the 20S CP and the 19S RP tagged proteins, we fused mScarlet to the C-terminus of PSMD6 in HeLa and HEK293 cell lines. The SpCas9 expression plasmid was pX330-U6-Chimeric_BB-CBh-hSpCas9 (Addgene plasmid #42230; RRID: Addgene_42230). The guide sequence CACCGGCTTTACATATTAATTACTC was inserted in this plasmid in targeting the 3’ end of the PSMD6 gene. The Donor plasmid was constructed by cloning a 1033 bp long fragment (

Figure S1) of the 3’ end of the PSMD6 gene, followed by a linker sequence in pBlueScript KS- (Stratagene). The linker sequence GGTGGAGGTAGTGGGGATCCACCGGTCGCCACC, followed by a segment of mScarlet coding frame and by a segment of 964 bp of the 3’ end of the human genome gene PSMD6 (from the stop codon in the reading frame).

The SpCas9 expression plasmid and the donor plasmids were transfected to HeLa cells using jetOPTIMUS regent according to the company instructions. Since editing efficiency was extremely low (~1%), cells were also transfected simultaneously with pFIRES puro plasmid (Hobbs et al., 1998) for puromycin selection. Cells were selected with 2 µg/ml puromycin the day after transfection. After 14 more days, cells were sorted with FACSAriaIII (BD Biosciences) to cells expressing PSMD6-mScarlet according to the mScarlet fluorescence signal. In establishing the double-tagged reporter, HeLa PSMD6-mScarlet PSMB6-YFP cells, the PSMB6-YFP editing was conducted in the PSMD6-mScarlet cell line. Double-reported positive cells were sorted by FACS. The cells are heterozygous for PSMD6 (

Figure S2).

Osmotic stress protocol

About 30,000 cells were plated in 96-well plate glass bottom. A day later, cells were Hoechst stained (1 µl/well). 20-30 minutes later, time-lapse images were taken. The media was replaced at time zero with media supplemented with 150mM NaCl/200mM sucrose for inducing osmotic stress.

Generation of PSMD1-KD cells

Cells were generated as described by (Tsvetkov et al., 2018). Briefly, cells were transduced with a lentiviral Tet-inducible TRIPZ vector with shRNAmir against 26S proteasome subunit PSMD1 (5’TGCTGTTGACAGTGAGCGAGCTCATATT GGGAATGCTTATTAGTGAAGCCACAGATGTAATAAGCATTCCCAATATGAGCCTGCCTACTGCCTCGGA-3’). The PSMD1 sequence is bolded. Cells are viable under this condition but die after 4-5 days. Images were taken at 3.5 days.

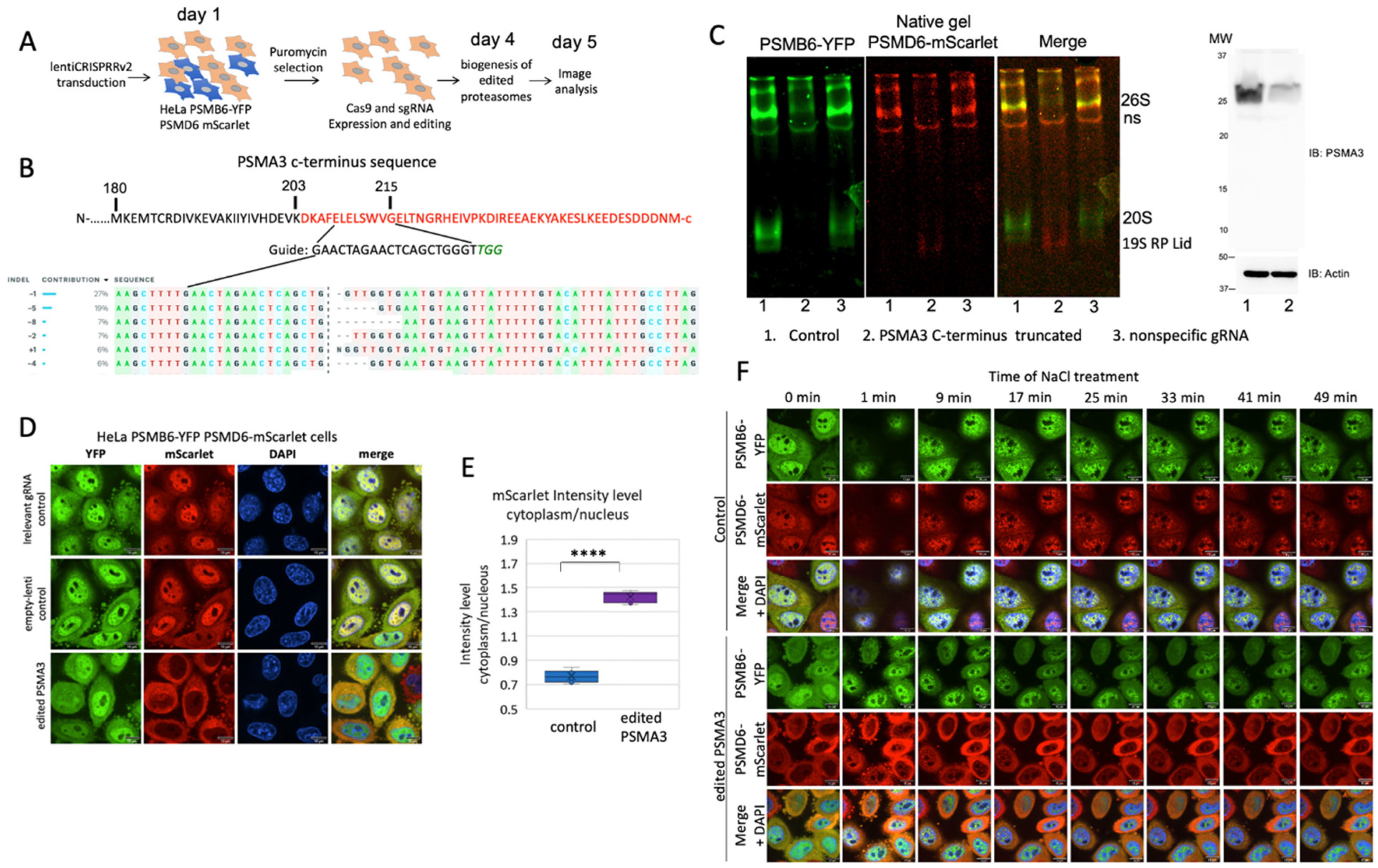

Generation of PSMA3 C-terminal truncated cells

To truncate the PSMA3 C-terminal region, a guide targeting PSMA3 around the amino acid 203 was cloned into a single lentiviral vector for delivery of Cas9, a sgRNA, and a puromycin selection marker (lentiCRISPRv2, #52961 from Addgene). For control, we used lentiCRISPRv2 harboring non-targeting gRNA sequences (TTTCGTGCCGATGTAACAC). SgRNAs were designed, and off-target cutting was assessed using the CRISPR designtool, Zhang lab, MIT. Lentivirions were produced as described (Cohen et al., 2010). HeLa PSMD6-mScarlet PSMB6-YFP cells were transduced with lentivirions based on the above vectors, followed by selection with 2 µg/ml puromycin for 3 days and imaged the next day. Edited cells did not survive and died 1-2 days later (

Figure S3).

To prepare genomic DNA for PCR analysis, cell pellets from approximately 10

5 cells were suspended in 18μl 50 mM NaOH and heated at 95

◦C for 10 min, followed by neutralization with 2μl 1 M Tris-Cl pH 8. PSMA3 genomic region around aa 203 was amplified, and the PCR fragment was sequenced via Sanger sequencing using a 3730 DNA Analyzer (ABI)). The Synthego ICE tool (

https://ice.synthego.com) was used to deconvolute the Sanger sequencing results of edited clones.

In-gel analysis of fluorescently tagged proteins

SDS-PAGE was used to assess the expression of PSMB6-YFP and PSMD6-mScarlet subunits by in-gel fluorescence assay (Saeed & Ashraf, 2009). HeLa PSMD6-mScarlet PSMB6-YFP cells were lysed on ice in NP-40 buffer [20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 0.32M sucrose, 5 mM MgCl2, 1% NP-40, 2mM ATP, and 1 mM DTT, supplemented by protease inhibitor cocktail] for 20 min, following centrifugation (20 min at 27,650g at 4C). Supernatants (40 μg) were mixed with the Laemmli protein sample buffer resulting in the final 0.8% SDS, but not heated, and separated on 12.5% SDS-PAGE. Gels were then scanned by Typhoon FLA 9500 imager for YFP signal, using a 473 nm laser for excitation and a 530DF20 BPB1 emission filter and mScarlet signal, using the 532 nm laser for excitation and 575LPR (>665 nm emission filter).

To visualize the proteasomal complexes in native conditions, the above extracts (80 μg) were analyzed on a nondenaturing 4% polyacrylamide gel, and the fluorescent signals were detected as above.

Live cell imaging

Cells were seeded on 96-well glass bottom Microwell plate 630µl black 17mm low glass of Matrical Bioscience (MGB096-1-2-LG) and allowed to adhere overnight. HeLa at a density of 30,000 cells/well, HEK293 at a density of 200,000 cells/well in a well that was coated with poly-D-lysine hydrobromide. Before the imaging using spinning disk microscopy, cell media was supplemented with 5 µg/ml Hoechst 33342. The plate was placed in the microscope chamber and cells were maintained at 37°C and 5% CO2 for the duration of the experiment. Images of 4 different sites in a well were taken every 4 minutes for 3 hours. Images were taken using a VisiScope Confocal Cell Explorer live cell imaging system a 60-oil objective.

Data Processing and Analysis

Images were constructed and processed by Visiview, Imaris, and Excel software. Images were cropped and adjusted using Visiview software. Nuclei and granules detection was made using a different set of parameters for every experiment in Imaris. Nuclei were defined as surfaces; the threshold was 400-1000 (absolute intensity). Granules were defined as spots; the threshold was 100-115 for YFP and 45-60 for mScarlet. Classification of granules inside/outside nuclei was calculated using the Shortest Distance to Surfaces, a distance between -2 to -6 µM. For mScarlet intensity analysis, nuclei, and cytoplasm detection was made using definitions of cells. Nuclei were defined using the Hoechst marker, the threshold was 350-400, and cytoplasm was defined using the mScarlet marker, the threshold was 250-300. The data then were processed and presented in graphs in excel. The profile line plot were generated by first manually drawing a linear region of interest and exporting the value along the line for each channel. FIJI’s ROI Manager tool’s Multi Plot feature was used for this step (Schindelin et al., 2012). Next, the values from each channel were normalized to that channel’s respective maximum value, and the normalized values are plotted in Excel.

Statistical tests of 2-tailed T-test were performed to assess significance using excel formulas. In the case of mScarlet intensity level, 100 background count was reduced from the total amount of both nucleus and cytoplasm.

Proteasome modeling

Was made using the program PyMOL. PDB files were downloaded from RCSB Protein Data Bank (RCSB PDB) website. Files were: 5vhh.PDB, 7oin.PDB, 3ed8.pdb, 6rgq.pdb.

3. Results

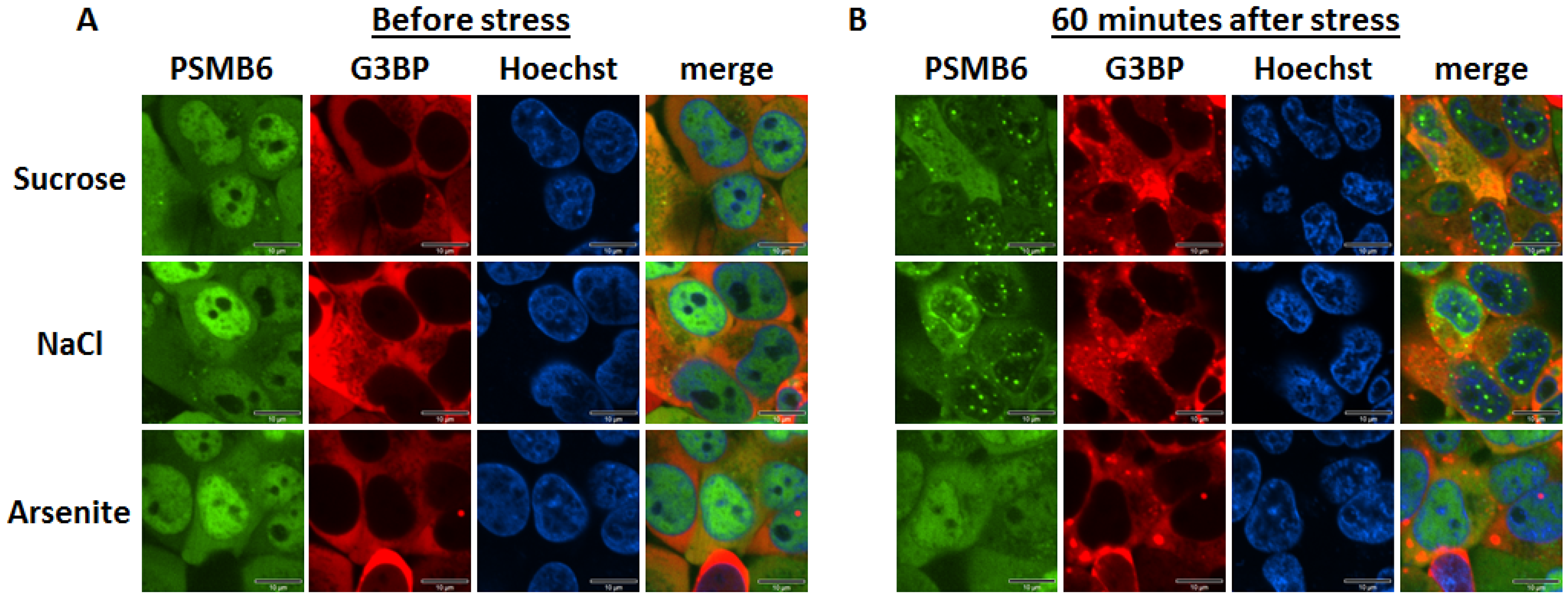

Intracellular monitoring of the 26S proteasome

We have previously reported establishing a YFP-tagged 20S proteasome cell line (Reuven et al., 2021; Tsvetkov et al., 2018). To this end, we employed CRISPR technology to generate the chimeric PSMB6-YFP gene. We transduced the PSMB6-YFP cell line using a lentivector expressing G3BP1-mCherry, a reporter of the stress granules. The tagged proteasome is preferentially nuclear, whereas the G3BP1-mCherry is exclusively in the cytoplasm (

Figure 1A). We exposed the cells to osmotic stress to induce the formation of nuclear proteasomal granules (

Figure 1B). We next treated the cells with arsenite, an inducer of stress granules. Stress granules were selectively formed under arsenite treatment. These data validate the distinct behavior of the proteasomal granules from the stress granules.

Figure 1.

PSMB6 and 3GBP under different stresses, the positive proteasome bodies are distinct from the stress granules. (A) PSMB6 was tagged with YFP, and G3BP1 was tagged with mCherry in HEK293 cells. (B) Cells were subjected to treatment with arsenite (1 mM, 1h), sucrose (200 mM, 1h), or NaCl (150 mM, 1h). The green live-imaging marker represents the 20S; the red represents stress granules. Nuclei were stained using Hoechst staining (blue). The scale bar is 10 µm.

Figure 1.

PSMB6 and 3GBP under different stresses, the positive proteasome bodies are distinct from the stress granules. (A) PSMB6 was tagged with YFP, and G3BP1 was tagged with mCherry in HEK293 cells. (B) Cells were subjected to treatment with arsenite (1 mM, 1h), sucrose (200 mM, 1h), or NaCl (150 mM, 1h). The green live-imaging marker represents the 20S; the red represents stress granules. Nuclei were stained using Hoechst staining (blue). The scale bar is 10 µm.

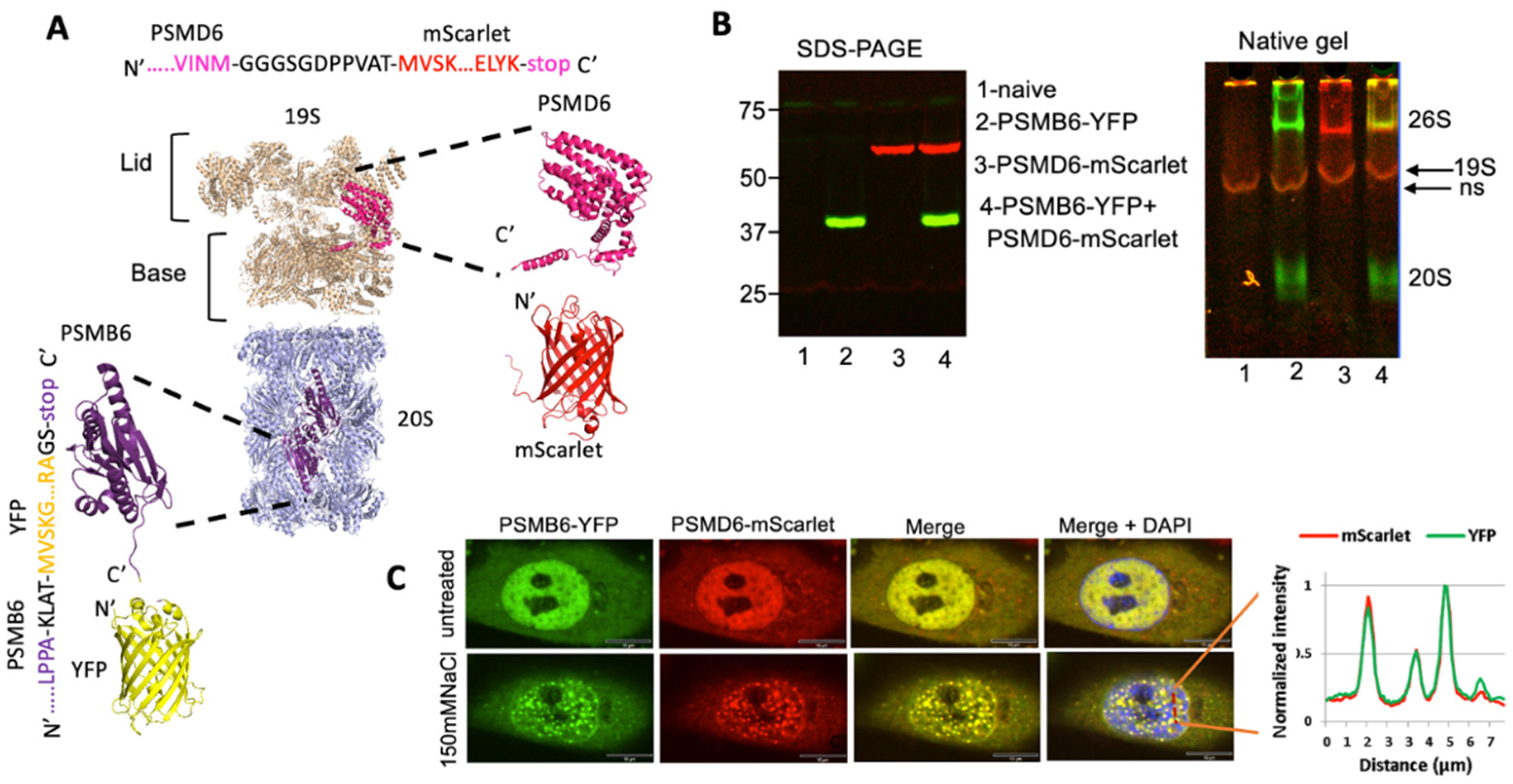

Next, we modified the PSMB6-YFP cells by fusing the endogenous PSMD6 gene to mScarlet fluorescent protein using the CRISPR technique to establish a double-tagged proteasome in HeLa cells (

Figure 2A). PSMD6-mScarlet allows the detection of the intracellular 19S RP in real time. The expression of the fluorescent PSMB6 and PSMD6 proteins was analyzed by SDS-PAGE and native gel (

Figure 2B). As expected, the 26S and the 20S proteasome complexes are both positive for PSMB6-YFP, whereas only 26S is positive for PSMD6-mScarlet. The 26S proteasome, therefore, is positive for both PSMB6-YFP and PSMD6-mScarlet.

Next, we microscopically analyzed the cells for the distribution of the fluorescent proteins. Interestingly, the most fluorescent signal is localized in the nucleus (

Figure 2C). The intracellular distribution of PSMB6-YFP completely overlapped with PSMD6-mScarlet distribution. Furthermore, the proteasome granules formed under osmotic stress are all positive for both YFP and mScarlet. These data suggest that the 26S proteasome is specifically visualized in the double-tagged cell line and that the level of other proteasome complexes (free 20S CP, PA200, and 11S PA28) is too low under detection by our technique.

Figure 2.

establishment of a double reporter HeLa cell line. (A) model showing the chimeric proteasome proteins and the fluorescence proteins. The 20S PC core proteasome is in gray, the PSMB6 subunits in purple, the YFP fluorescence protein in yellow, the 19S RP in cream, the PSMD6 subunit in pink, and the mScarlet fluorescence protein in red. The junction sequences, PSMD6 C-terminus and mScarlet N-terminus, are shown

(B) Fluorescent detection of the chimeric proteins. On the left is SDS-PAGE, and on the right is the native gel analysis of the cell extracts. 19S is visualized but very close to it a nonspecific (ns) band is seen in the controls. The identity of the 19S becomes more evident in

Figure 5, see below.

(C) HeLa PSMB6-YFP PSMD6-mScarlet cells were treated with 150 mM NaCl. The green live-imaging marker represents the 20S, the red marker 19S, and hence 26S; the blue represents the nucleus. The scale bar is 10µm. The left panel shows the line profiling of a section of the cell indicated by a red dashed line.

Figure 2.

establishment of a double reporter HeLa cell line. (A) model showing the chimeric proteasome proteins and the fluorescence proteins. The 20S PC core proteasome is in gray, the PSMB6 subunits in purple, the YFP fluorescence protein in yellow, the 19S RP in cream, the PSMD6 subunit in pink, and the mScarlet fluorescence protein in red. The junction sequences, PSMD6 C-terminus and mScarlet N-terminus, are shown

(B) Fluorescent detection of the chimeric proteins. On the left is SDS-PAGE, and on the right is the native gel analysis of the cell extracts. 19S is visualized but very close to it a nonspecific (ns) band is seen in the controls. The identity of the 19S becomes more evident in

Figure 5, see below.

(C) HeLa PSMB6-YFP PSMD6-mScarlet cells were treated with 150 mM NaCl. The green live-imaging marker represents the 20S, the red marker 19S, and hence 26S; the blue represents the nucleus. The scale bar is 10µm. The left panel shows the line profiling of a section of the cell indicated by a red dashed line.

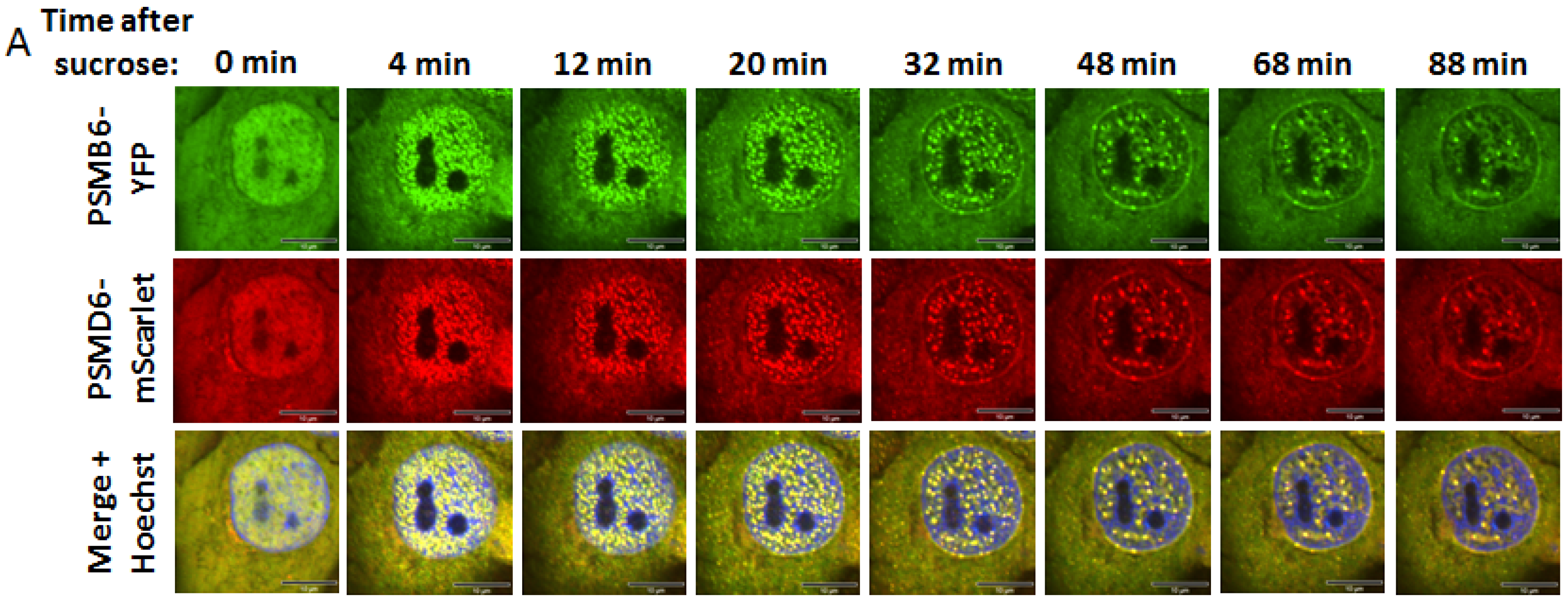

Time kinetics of the 26S proteasome granules in response to osmotic stress

Having established a cell line for visualizing the 26S proteasome, we next performed time-lapse imaging to monitor the behavior of the 26S proteasome under osmotic stress. Cells were treated with 200 mM sucrose and as expected described (Yasuda et al., 2020) hyperosmotic stress induced the formation of nuclear PSMB6-YFP positive proteasome granules (

Figure 3A and

Figure S4). The 26S proteasomes formed these granules since all the granules were also positive for the PSMD6-mScarlet. The 26S granules were visualized after four minutes and reached maximal level after 12 minutes (

Figure 3B,C). Cells recovery took place with slower time kinetics. Interestingly, in the longer time points the granules were more visualized at the nuclear periphery.

Figure 3.

proteasome granules dynamic under sucrose osmotic stress. (A) Time-lapse images of HeLa PSMB6-YFP PSMD6-mScarlet cells treated with 200 mM sucrose. The green live-imaging marker represents all proteasomes, the red live-imaging marker represents 19S RP and the yellow spots in the merge panel represent 26S proteasomes. The nuclei were Hoechst stained (blue). Frames were taken every 4 min. The scale bar is 10µm (B) the average number of granules per cell at the indicated time points seen with YFP vs. mScarlet markers, n=3 repetitions. (C) the average number of nuclear granules at the indicated time points seen with YFP vs. mScarlet, n=3 repetitions. ns, not significant, *P < 0.05 by 2-tailed unpaired t-test.

Figure 3.

proteasome granules dynamic under sucrose osmotic stress. (A) Time-lapse images of HeLa PSMB6-YFP PSMD6-mScarlet cells treated with 200 mM sucrose. The green live-imaging marker represents all proteasomes, the red live-imaging marker represents 19S RP and the yellow spots in the merge panel represent 26S proteasomes. The nuclei were Hoechst stained (blue). Frames were taken every 4 min. The scale bar is 10µm (B) the average number of granules per cell at the indicated time points seen with YFP vs. mScarlet markers, n=3 repetitions. (C) the average number of nuclear granules at the indicated time points seen with YFP vs. mScarlet, n=3 repetitions. ns, not significant, *P < 0.05 by 2-tailed unpaired t-test.

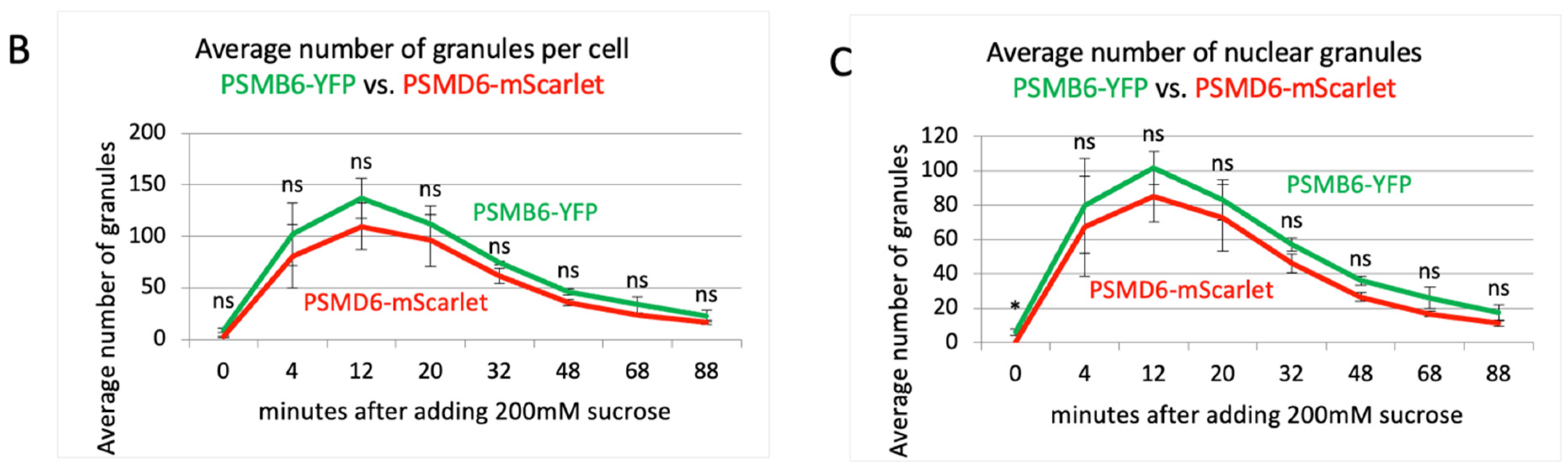

Next, we induced salt osmotic stress (

Figure 4A and

Figure S5). Here again, all the granules were positive for both PSMB6-YFP and PSMD6-mScarlet, suggesting that the 26S proteasome formed the granules. Salt osmotic stress-induced proteasomal granules rapidly developed, and the maximal number of granules was observed after 4 minutes (

Figure 4B,C). like the sucrose treatment, the decay in the number of granules took much longer, with a tendency to be localized at the nuclear periphery. These data suggest that in response to osmotic stress, the 26S proteasomes form nuclear granules and that no 26S disassembly occurs along the formation and resolution of the granule formation.

Figure 4.

proteasome granules dynamic under NaCl osmotic stress. (A) Time-lapse images of HeLa PSMB6-YFP PSMD6-mScarlet cells treated with 150 mM NaCl. The green live-imaging marker represents all proteasomes, the red live-imaging marker represents 19S RP and the yellow spots in the merge panel represent 26S proteasomes. The nuclei were Hoechst stained (blue). Frames were taken every 4 min. The scale bar is 10µm. (B) the average number of granules per cell at selected time points seen with YFP vs. mScarlet markers, n=3 repetitions. (C) the average number of nuclear granules at the selected time points seen with YFP vs. mScarlet, n=3 repetitions. ns, not significant, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001 respectively by 2-tailed unpaired t-test.

Figure 4.

proteasome granules dynamic under NaCl osmotic stress. (A) Time-lapse images of HeLa PSMB6-YFP PSMD6-mScarlet cells treated with 150 mM NaCl. The green live-imaging marker represents all proteasomes, the red live-imaging marker represents 19S RP and the yellow spots in the merge panel represent 26S proteasomes. The nuclei were Hoechst stained (blue). Frames were taken every 4 min. The scale bar is 10µm. (B) the average number of granules per cell at selected time points seen with YFP vs. mScarlet markers, n=3 repetitions. (C) the average number of nuclear granules at the selected time points seen with YFP vs. mScarlet, n=3 repetitions. ns, not significant, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001 respectively by 2-tailed unpaired t-test.

Nuclear localization of the 20S proteasome in 19S knockdown cells

Previously we have shown that the knockdown of subunits of the 19S RC reduces the level of the 26S proteasome with a concomitant increase at the level of the 20S CP (Tsvetkov et al., 2018). We transduced the proteasome double reporter cells with a lentivector expressing shRNA to target PSMD1 in a doxycycline (dox) inducible manner (

Figure 5A), using our reported protocol (Tsvetkov et al., 2018).

Under this condition the level of most of other 19S RP was not affected (Figure S6). Native gel analysis validated a sharp reduction at the level of the 26S with a concomitant increase at the level of the 20S CP, in dox-treated cells (

Figure 5B).

PSMD1 (Rpn2), is a component of the 19S Base subcomplex, and is critical for the assembly of the 19S RP (Glickman, Rubin, Coux, et al., 1998), indeed,

the level of the intact 19S RP is too low to be detected. In fact, it is expected that the 19S RP is completely disassembled and PSMD6-mScarlet is “free”. As PSMD6-mScarlet is a component of the 19S Lid the observed faint red complex underneath the 20S CP is likely to be the residual PSMD6-mScarlet positive Lid subcomplex. Remarkably, in dox-treated cells, the PSMD6-mScarlet was barely detected in the nuclei and significantly accumulated in the cytoplasm (

Figure 5C,D). The cytoplasmic PSMD6-mScarlet is likely to represent the “free” or 19S RP Lid associated PSMD6-mScarlet. The “free” 20S CP remained mostly nuclear. This behavior was not observed in the control cells; the dox-treated cells in the absence of the PSMD1 shRNA cassette and the non-treated cells in the presence of the PSMD1 shRNA cassette. These results suggest that the “free” 20S CP is mostly nuclear.

Next, the cells were subjected to osmotic stress (

Figure 5E and

Figure S6). As expected, nuclear 26S proteasome granules were rapidly formed in untreated control cells (Amzallag & Hornstein, 2022; Yasuda et al., 2020). In contrast in the PSMD1 knocked-down cells, the PSMD6-mScarlet remained in the cytoplasm and did not form visible granules. The “free” 20S CP remained unclear but did not form granules. Before osmotic stress induction, the 20S CP was homogeneously distributed in the nucleus, however, upon osmotic stress, the 20S CP did not form the classical granules but instead formed subnuclear defused aggregates. These data suggest that the 26S proteasome is critical for the formation of the proteasome granules in response to osmotic stress.

Figure 5.

Proteasome granules are dynamic under osmotic stress. (A) Schematic description of the strategy of PSMD1 knockdown using the doxycycline (dox) inducible system. (B) native gel of the three treatment groups described in panel A, as scanned for YFP and mScarlet. (C) HeLa PSMB6-YFP PSMD6-mScarlet PSMD1-KD cassette cells were treated or untreated with doxycycline and imaged after 3.5 days. As an additional control, HeLa PSMB6-YFP PSMD6-mScarlet cells were doxycycline-treated and imaged after 3.5 days. (D) Boxplot analysis of the mScarlet intensity level in the cytoplasm versus the nucleus, n=8 repetitions each. ****P < 0.0001 by 2-tailed unpaired t-test. (E) Time-lapse images of HeLa PSMB6-YFP PSMD6-mScarlet cells and HeLa PSMB6-YFP PSMD6-mScarlet PSMD1-KD cells treated with 100 mM NaCl. Frames were taken every 4 min. The scale bar is 10µm.

Figure 5.

Proteasome granules are dynamic under osmotic stress. (A) Schematic description of the strategy of PSMD1 knockdown using the doxycycline (dox) inducible system. (B) native gel of the three treatment groups described in panel A, as scanned for YFP and mScarlet. (C) HeLa PSMB6-YFP PSMD6-mScarlet PSMD1-KD cassette cells were treated or untreated with doxycycline and imaged after 3.5 days. As an additional control, HeLa PSMB6-YFP PSMD6-mScarlet cells were doxycycline-treated and imaged after 3.5 days. (D) Boxplot analysis of the mScarlet intensity level in the cytoplasm versus the nucleus, n=8 repetitions each. ****P < 0.0001 by 2-tailed unpaired t-test. (E) Time-lapse images of HeLa PSMB6-YFP PSMD6-mScarlet cells and HeLa PSMB6-YFP PSMD6-mScarlet PSMD1-KD cells treated with 100 mM NaCl. Frames were taken every 4 min. The scale bar is 10µm.

PSMA3 C-terminus regulates 26S proteasome integrity.

Lately, we have reported that the PSMA3 C-terminus interacts with many disordered proteins in their degradation (Biran et al., 2022). We employed CRISPR technology to truncate the PSMA3 C-terminal region in the proteasome double reporter cells and pooled cells were subjected to further analysis (

Figure 6A-B). As a control, we used lentiCRISPRv2 harboring non-targeting gRNA sequence. “Free” 20S CP was not detected in the C-terminus truncated PSMA3 cells as analyzed by native gel (

Figure 6C). Although RNA analysis revealed that the cells express about 20% truncated PSMA3 mRNA, we could not detect the truncated protein by immunoblot analysis. Also, the 19S RP became unstable and only the Lid subcomplex is detected. Thus, the proteasome integrity was dramatically compromised under these conditions. The PSMB6-YFP residual 20S CP is nuclear, possibly the result of some residual 20S CP and PSMD6-mScarlet is localized in the cytoplasm including the residual 19S RP (

Figure 6 D,E). For controls, we either used irrelevant gRNA or transduced the cells with an “empty” lentivector.

Next, the cells were subjected to osmotic stress (

Figure 6F). The observed phenotype is reminiscent of the PSMD1 knocked down cells, and the nuclear PSMB6-YFP did not form foci. The few observed foci are all positive to PSMD6-mScarlet, suggesting they are of 26S proteasome type. These data suggest that CRISPR editing targeted to delete the C-terminal region of the PSMA3 dramatically affected the integrity and subcellular localization of both the 20S CP and 19S RP.

Figure 6.

The PSMA3 C-terminus regulates 26S proteasome integrity. (A) Schematic description of the strategy of selecting cells with truncated C-terminus PSMA3. A day after transduction cells were puromycin treated (2 µg/ml) for three days. Images were taken a day later. (B) Sequencing analysis of edited HeLa PSMB6-YFP PSMD6-mScarlet cells in deleting the PSMA3 C-terminal region. The 450 bp fragment was amplified, sequenced, and the results were analyzed by using the Synthego ICE tool (Synthego Performance Analysis, ICE Analysis. 2019. v2. Synthego). The guide sequence is shown. (C) Native and immunoblot analysis of the CRISPR edited cells. PSMA3 monoclonal antibody used is D4Y9O (cell signaling). (D) The edited HeLa PSMB6-YFP PSMD6-mScarlet cells and the controls (lentiviruses with a non-targeting guide or with a trapper-targeting guide) were imaged after 5 days. The scale bar is 10µm. (E) Boxplot analysis of the mScarlet intensity level in the cytoplasm versus the nucleus. ****P < 0.0001 by 2-tailed unpaired t-test. (F) Time-lapse images of cells treated with 100 mM NaCl. Frames were taken every 4 min. The scale bar is 10µm.

Figure 6.

The PSMA3 C-terminus regulates 26S proteasome integrity. (A) Schematic description of the strategy of selecting cells with truncated C-terminus PSMA3. A day after transduction cells were puromycin treated (2 µg/ml) for three days. Images were taken a day later. (B) Sequencing analysis of edited HeLa PSMB6-YFP PSMD6-mScarlet cells in deleting the PSMA3 C-terminal region. The 450 bp fragment was amplified, sequenced, and the results were analyzed by using the Synthego ICE tool (Synthego Performance Analysis, ICE Analysis. 2019. v2. Synthego). The guide sequence is shown. (C) Native and immunoblot analysis of the CRISPR edited cells. PSMA3 monoclonal antibody used is D4Y9O (cell signaling). (D) The edited HeLa PSMB6-YFP PSMD6-mScarlet cells and the controls (lentiviruses with a non-targeting guide or with a trapper-targeting guide) were imaged after 5 days. The scale bar is 10µm. (E) Boxplot analysis of the mScarlet intensity level in the cytoplasm versus the nucleus. ****P < 0.0001 by 2-tailed unpaired t-test. (F) Time-lapse images of cells treated with 100 mM NaCl. Frames were taken every 4 min. The scale bar is 10µm.

4. Discussion

We report here the establishment of a cell line for live visualization of both; the 20S CP and 19S RP at a single-cell resolution. Time-lapse imaging revealed that these two complexes form the 26S proteasome under normal and osmotic stress conditions. The 26S proteasome mostly resides in the nucleus, and the osmotic stress-induced proteasome granules, are primarily nuclear. The alternative 20S CP caps, such as PSME1 to 4 (Stadtmueller & Hill, 2011), that in our assay should be tagged only by PSMB6-YFP, “free” 20S CP, are hardly seen. Using biochemical and extract fractionation methods, it was reported that “free” 20S CP is about 30-40% of the total proteasome complexes in HeLa cells (Fabre et al., 2014; Tanahashi et al., 2000). We did not visualize significant amount of “free” 20S CP, signifying the meager amount of non-26S proteasomes. However, one cannot exclude the possibility that certain level of “free” 19S and 20S are co-localized without forming 26S. Notably, asymmetric 26S proteasomes, where the 20S CP is capped only with one 19S RP, with the antipode side being uncapped (RP-CP, but not RP-CP-RP), cannot be distinguished by our assay from the doubly capped one since a single RP is sufficient to label the 20S CP with mScalet. The unoccupied side of 20S CP (RP-CP) might function in a 19S RP-independent manner.

Knockdown of a 19S RP subunit increases the level of the “free” 20S CP (Sahu et al., 2021; Tsvetkov et al., 2018; Welk et al., 2016), but whether this process affects the proteasomal subcellular localization is unknown. We report here that under this condition the tagged 19S subunit, possibly the 19S RP Lid subcomplex, is nuclear excluded whereas the “free” 20S CP is mostly nuclear. The “free” 20S CP are nuclear even under osmotic stress, although they do not form the classical condensate granules of the 26S proteasome. It has been reported that RAD23B, a ubiquitin-binding shuttle protein is essential in the formation of nuclear proteasomal condensates(Amzallag & Hornstein, 2022; Uriarte et al., 2021; Yasuda et al., 2020). The p62/SQSTM1 ubiquitin-binding protein is another ubiquitin shuttle protein regulating nuclear condensates (Amzallag & Hornstein, 2022; Fu et al., 2021). The nuclear “free” 20S CP could be either the result of their de novo nuclear assembly or the product of the 26S proteasomes disassembly. However, since this proteasome complex is not expected to bind ubiquitin shuttle proteins, it seems that their nuclear residency is either the default of 26S proteasome disassembly or is AKIRIN2 mediated. AKIRIN2 binds to the 20S proteasome surface in mediating its nuclear import of the “free” 20S CP (Chen & Walters, 2022; de Almeida et al., 2021; Guo, 2022).

Evidence is accumulating for the role of 20S CP in isolation in degrading proteins (Asher et al., 2006; Biran et al., 2022; Kumar Deshmukh et al., 2019; Sahu et al., 2021). Since the process is ubiquitin independent a key question was how the substrates are recruited for degradation. In vitro degradation assay revealed over two hundred IDPs/IDRs proteins that are degraded by purified 20S CP (Myers et al., 2018). Interestingly a large fraction of this group of IDPs/IDRs directly binds PSMA3 C-terminus (Biran et al., 2022). To investigate the role of this region in the cells we employed the CRISPR technology to truncate PSMA3 by deleting the region active in binding IDPs/IDRs substrates. Using the proteasome double reporters, we found profound segregation of the two tagged proteasome subunits; the 20S CP PSMB6-YFP is nuclear whereas the 19S RP PSMD6-mScarlet subunit resides in the cytoplasm. This finding is consistent with the report that PR-39 blocks PSMA3 (alpha 7) subunit and inhibits 20S-19S interaction (Gaczynska et al., 2003).

Native gel analysis revealed that the tagged 19S RP is not intact and possibly is dissociated into its two subcomplexes; Base and Lid (Glickman, Rubin, Coux, et al., 1998). Under osmotic stress, the tagged 19S RP remained in the cytoplasm. The nature of the nuclear PSMB6-YFP positive component is not well defined. The beyond-detection level of the 20S CP in the native gel and lack of detection of the truncated PSMA3 might suggest that the observed nuclear PSMB6-YFP is not an intact 20S CP. However, it is also possible that the incorporation of the truncated PSMA3 into the 20S CP makes the complex unstable and dissociates during cell extraction.

How PSMA3 regulates 26S proteasome integrity is an open question. Previously it has been reported that PSMA3 C-terminal phosphorylation increases 26S integrity (Bose et al., 2004). This region has an acidic patch, and phosphorylation further increases acidity. It is, therefore, possible that the charged PSMA3 C-terminus increases the process of 20S CP capping by 19S RP, as was reported in yeast for the binding of Ecm29, a proteasome interacting protein (Wang et al., 2017; Wani et al., 2016). The double-reporters proteasome cell line we have established, for the first time, allows live visualization of proteasome distribution in mammalian cells to investigate proteasome behavior under various conditions. In isolation, the distinct subcellular localization of the two major proteasome particles, the 20S CP and the 19S RP can be exploited to investigate 26S proteasome assembly and identify the proteins involved in this process. Furthermore, this system might greatly assist in discovering and assaying small molecules regulating proteasome assembly and disassembly for research and clinical aims (Coleman & Trader, 2018; Njomen et al., 2018; Tsvetkov et al., 2018).

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org, Figure S1: The sequence of the donor DNA in CRISPR-Cas9 editing of PSMD6. Figure S2: Evidence for heterozygosity of the PSMD6-mScarlet cells. Figure S3: Microscopic images of control and C-terminus truncated PSMA3 edited cells after 6 days. Figure S4: Wide-field images of proteasome granules under sucrose osmotic stress at different time points. Figure S5: Wide-field images of proteasome granules under NaCl osmotic stress at different time points. Figure S6: Western blot analysis of the components of 19S in PSMD1 knockout cells. Figure S7: Wide-field images of proteasome granules under osmotic stress.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.S.; methodology, S.S., and J.A.; software, S.S.; validation, J.A.; formal analysis, S.S., and J.A.; investigation, S.S., and J.A.; writing—original draft preparation, Y,S.; supervision, Y.S.; funding acquisition, Y.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Please add: “This research received no external funding”

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable

Acknowledgments

We thank Ayala Sharp from the Weizmann FACS unit for her assistance; Nina Reuven for her guidance in the CRISPR procedures; and Joseph Steinberger for his help with data processing and analysis.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Amzallag, E., & Hornstein, E. (2022). Crosstalk between Biomolecular Condensates and Proteostasis. Cells, 11(15). https://doi.org/10.3390/cells11152415. [CrossRef]

- Asher, G., Reuven, N., & Shaul, Y. (2006). 20S proteasomes and protein degradation “by default”. Bioessays: News and Reviews in Molecular, Cellular and Developmental Biology, 28(8), 844–849. https://doi.org/10.1002/bies.20447. [CrossRef]

- Biran, A., Myers, N., Steinberger, S., Adler, J., Riutin, M., Broennimann, K., Reuven, N., & Shaul, Y. (2022). The C-Terminus of the PSMA3 Proteasome Subunit Preferentially Traps Intrinsically Disordered Proteins for Degradation. Cells, 11(20). https://doi.org/10.3390/cells11203231. [CrossRef]

- Bose, S., Stratford, F. L. L., Broadfoot, K. I., Mason, G. G. F., & Rivett, A. J. (2004). Phosphorylation of 20S proteasome alpha subunit C8 (alpha7) stabilizes the 26S proteasome and plays a role in the regulation of proteasome complexes by gamma-interferon. The Biochemical Journal, 378(Pt 1), 177–184. https://doi.org/10.1042/BJ20031122. [CrossRef]

- Chen, X., & Walters, K. J. (2022). Nuclear destruction: A suicide mission by AKIRIN2 brings intact proteasomes into the nucleus. Molecular Cell, 82(1), 13–14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molcel.2021.11.020. [CrossRef]

- Coffino, P., & Cheng, Y. (2022). Allostery Modulates Interactions between Proteasome Core Particles and Regulatory Particles. Biomolecules, 12(6). https://doi.org/10.3390/biom12060764. [CrossRef]

- Cohen, D., Adamovich, Y., Reuven, N., & Shaul, Y. (2010). Hepatitis B virus activates deoxynucleotide synthesis in nondividing hepatocytes by targeting the R2 gene. Hepatology, 51(5), 1538–1546. https://doi.org/10.1002/hep.23519. [CrossRef]

- Coleman, R. A., & Trader, D. J. (2018). Development and application of a sensitive peptide reporter to discover 20S proteasome stimulators. ACS Combinatorial Science, 20(5), 269–276. https://doi.org/10.1021/acscombsci.7b00193. [CrossRef]

- de Almeida, M., Hinterndorfer, M., Brunner, H., Grishkovskaya, I., Singh, K., Schleiffer, A., Jude, J., Deswal, S., Kalis, R., Vunjak, M., Lendl, T., Imre, R., Roitinger, E., Neumann, T., Kandolf, S., Schutzbier, M., Mechtler, K., Versteeg, G. A., Haselbach, D., & Zuber, J. (2021). AKIRIN2 controls the nuclear import of proteasomes in vertebrates. Nature, 599(7885), 491–496. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-021-04035-8. [CrossRef]

- Dong, Y., Zhang, S., Wu, Z., Li, X., Wang, W. L., Zhu, Y., Stoilova-McPhie, S., Lu, Y., Finley, D., & Mao, Y. (2019). Cryo-EM structures and dynamics of substrate-engaged human 26S proteasome. Nature, 565(7737), 49–55. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-018-0736-4. [CrossRef]

- Enenkel, C., Kang, R. W., Wilfling, F., & Ernst, O. P. (2022). Intracellular localization of the proteasome in response to stress conditions. The Journal of Biological Chemistry, 298(7), 102083. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbc.2022.102083. [CrossRef]

- Fabre, B., Lambour, T., Garrigues, L., Ducoux-Petit, M., Amalric, F., Monsarrat, B., Burlet-Schiltz, O., & Bousquet-Dubouch, M.-P. (2014). Label-free quantitative proteomics reveals the dynamics of proteasome complexes composition and stoichiometry in a wide range of human cell lines. Journal of Proteome Research, 13(6), 3027–3037. https://doi.org/10.1021/pr500193k. [CrossRef]

- Fu, A., Cohen-Kaplan, V., Avni, N., Livneh, I., & Ciechanover, A. (2021). p62-containing, proteolytically active nuclear condensates, increase the efficiency of the ubiquitin-proteasome system. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 118(33). https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2107321118. [CrossRef]

- Gaczynska, M., Osmulski, P. A., Gao, Y., Post, M. J., & Simons, M. (2003). Proline- and arginine-rich peptides constitute a novel class of allosteric inhibitors of proteasome activity. Biochemistry, 42(29), 8663–8670. https://doi.org/10.1021/bi034784f. [CrossRef]

- Gan, J., Leestemaker, Y., Sapmaz, A., & Ovaa, H. (2019). Highlighting the proteasome: using fluorescence to visualize proteasome activity and distribution. Frontiers in Molecular Biosciences, 6, 14. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmolb.2019.00014. [CrossRef]

- Glickman, M. H., Rubin, D. M., Coux, O., Wefes, I., Pfeifer, G., Cjeka, Z., Baumeister, W., Fried, V. A., & Finley, D. (1998). A subcomplex of the proteasome regulatory particle required for ubiquitin-conjugate degradation and related to the COP9-signalosome and eIF3. Cell, 94(5), 615–623. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81603-7. [CrossRef]

- Glickman, M. H., Rubin, D. M., Fried, V. A., & Finley, D. (1998). The regulatory particle of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae proteasome. Molecular and Cellular Biology, 18(6), 3149–3162. https://doi.org/10.1128/MCB.18.6.3149. [CrossRef]

- Goldberg, A. L., Kim, H. T., Lee, D., & Collins, G. A. (2021). Mechanisms that activate 26S proteasomes and enhance protein degradation. Biomolecules, 11(6). https://doi.org/10.3390/biom11060779. [CrossRef]

- Greene, E. R., Dong, K. C., & Martin, A. (2020). Understanding the 26S proteasome molecular machine from a structural and conformational dynamics perspective. Current Opinion in Structural Biology, 61, 33–41. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbi.2019.10.004. [CrossRef]

- Groll, M., Bajorek, M., Köhler, A., Moroder, L., Rubin, D. M., Huber, R., Glickman, M. H., & Finley, D. (2000). A gated channel into the proteasome core particle. Nature Structural Biology, 7(11), 1062–1067. https://doi.org/10.1038/80992. [CrossRef]

- Groll, M., Ditzel, L., Löwe, J., Stock, D., Bochtler, M., Bartunik, H. D., & Huber, R. (1997). Structure of 20S proteasome from yeast at 2.4 A resolution. Nature, 386(6624), 463–471. https://doi.org/10.1038/386463a0. [CrossRef]

- Guo, X. (2022). Localized proteasomal degradation: from the nucleus to cell periphery. Biomolecules, 12(2). https://doi.org/10.3390/biom12020229. [CrossRef]

- Gu, Z. C., & Enenkel, C. (2014). Proteasome assembly. Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences, 71(24), 4729–4745. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00018-014-1699-8. [CrossRef]

- Hobbs, S., Jitrapakdee, S., & Wallace, J. C. (1998). Development of a bicistronic vector driven by the human polypeptide chain elongation factor 1alpha promoter for creation of stable mammalian cell lines that express very high levels of recombinant proteins. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications, 252(2), 368–372. https://doi.org/10.1006/bbrc.1998.9646. [CrossRef]

- Kumar Deshmukh, F., Yaffe, D., Olshina, M. A., Ben-Nissan, G., & Sharon, M. (2019). The contribution of the 20S proteasome to proteostasis. Biomolecules, 9(5). https://doi.org/10.3390/biom9050190. [CrossRef]

- Levy, D., Adamovich, Y., Reuven, N., & Shaul, Y. (2007). The Yes-associated protein 1 stabilizes p73 by preventing Itch-mediated ubiquitination of p73. Cell Death and Differentiation, 14(4), 743–751. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.cdd.4402063. [CrossRef]

- Myers, N., Olender, T., Savidor, A., Levin, Y., Reuven, N., & Shaul, Y. (2018). The Disordered Landscape of the 20S Proteasome Substrates Reveals Tight Association with Phase Separated Granules. Proteomics, 18(21–22), e1800076. https://doi.org/10.1002/pmic.201800076. [CrossRef]

- Njomen, E., Osmulski, P. A., Jones, C. L., Gaczynska, M., & Tepe, J. J. (2018). Small molecule modulation of proteasome assembly. Biochemistry, 57(28), 4214–4224. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.biochem.8b00579. [CrossRef]

- Religa, T. L., Sprangers, R., & Kay, L. E. (2010). Dynamic regulation of archaeal proteasome gate opening as studied by TROSY NMR. Science, 328(5974), 98–102. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1184991. [CrossRef]

- Reuven, N., Adler, J., Broennimann, K., Myers, N., & Shaul, Y. (2019). Recruitment of DNA Repair MRN Complex by Intrinsically Disordered Protein Domain Fused to Cas9 Improves Efficiency of CRISPR-Mediated Genome Editing. Biomolecules, 9(10). https://doi.org/10.3390/biom9100584. [CrossRef]

- Reuven, N., Adler, J., Myers, N., & Shaul, Y. (2021). CRISPR Co-Editing Strategy for Scarless Homology-Directed Genome Editing. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 22(7). https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms22073741. [CrossRef]

- Saeed, I. A., & Ashraf, S. S. (2009). Denaturation studies reveal significant differences between GFP and blue fluorescent protein. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules, 45(3), 236–241. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2009.05.010. [CrossRef]

- Sahu, I., Mali, S. M., Sulkshane, P., Xu, C., Rozenberg, A., Morag, R., Sahoo, M. P., Singh, S. K., Ding, Z., Wang, Y., Day, S., Cong, Y., Kleifeld, O., Brik, A., & Glickman, M. H. (2021). The 20S as a stand-alone proteasome in cells can degrade the ubiquitin tag. Nature Communications, 12(1), 6173. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-021-26427-0. [CrossRef]

- Schindelin, J., Arganda-Carreras, I., Frise, E., Kaynig, V., Longair, M., Pietzsch, T., Preibisch, S., Rueden, C., Saalfeld, S., Schmid, B., Tinevez, J.-Y., White, D. J., Hartenstein, V., Eliceiri, K., Tomancak, P., & Cardona, A. (2012). Fiji: an open-source platform for biological-image analysis. Nature Methods, 9(7), 676–682. https://doi.org/10.1038/nmeth.2019. [CrossRef]

- Stadtmueller, B. M., & Hill, C. P. (2011). Proteasome activators. Molecular Cell, 41(1), 8–19. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molcel.2010.12.020. [CrossRef]

- Tanahashi, N., Murakami, Y., Minami, Y., Shimbara, N., Hendil, K. B., & Tanaka, K. (2000). Hybrid proteasomes. Induction by interferon-gamma and contribution to ATP-dependent proteolysis. The Journal of Biological Chemistry, 275(19), 14336–14345. https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.275.19.14336. [CrossRef]

- Tsvetkov, P., Adler, J., Myers, N., Biran, A., Reuven, N., & Shaul, Y. (2018). Oncogenic addiction to high 26S proteasome level. Cell Death & Disease, 9(7), 773. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41419-018-0806-4. [CrossRef]

- Tsvetkov, P., Myers, N., Adler, J., & Shaul, Y. (2020). Degradation of intrinsically disordered proteins by the NADH 26S proteasome. Biomolecules, 10(12). https://doi.org/10.3390/biom10121642. [CrossRef]

- Tsvetkov, P., Myers, N., Eliav, R., Adamovich, Y., Hagai, T., Adler, J., Navon, A., & Shaul, Y. (2014). NADH binds and stabilizes the 26S proteasomes independent of ATP. The Journal of Biological Chemistry, 289(16), 11272–11281. https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M113.537175. [CrossRef]

- Uriarte, M., Sen Nkwe, N., Tremblay, R., Ahmed, O., Messmer, C., Mashtalir, N., Barbour, H., Masclef, L., Voide, M., Viallard, C., Daou, S., Abdelhadi, D., Ronato, D., Paydar, M., Darracq, A., Boulay, K., Desjardins-Lecavalier, N., Sapieha, P., Masson, J.-Y., … Affar, E. B. (2021). Starvation-induced proteasome assemblies in the nucleus link amino acid supply to apoptosis. Nature Communications, 12(1), 6984. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-021-27306-4. [CrossRef]

- Wang, X., Chemmama, I. E., Yu, C., Huszagh, A., Xu, Y., Viner, R., Block, S. A., Cimermancic, P., Rychnovsky, S. D., Ye, Y., Sali, A., & Huang, L. (2017). The proteasome-interacting Ecm29 protein disassembles the 26S proteasome in response to oxidative stress. The Journal of Biological Chemistry, 292(39), 16310–16320. https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M117.803619. [CrossRef]

- Wani, P. S., Suppahia, A., Capalla, X., Ondracek, A., & Roelofs, J. (2016). Phosphorylation of the C-terminal tail of proteasome subunit α7 is required for binding of the proteasome quality control factor Ecm29. Scientific Reports, 6, 27873. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep27873. [CrossRef]

- Welk, V., Coux, O., Kleene, V., Abeza, C., Trümbach, D., Eickelberg, O., & Meiners, S. (2016). Inhibition of proteasome activity induces formation of alternative proteasome complexes. The Journal of Biological Chemistry, 291(25), 13147–13159. https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M116.717652. [CrossRef]

- Wójcik, C., & DeMartino, G. N. (2003). Intracellular localization of proteasomes. The International Journal of Biochemistry & Cell Biology, 35(5), 579–589. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1357-2725(02)00380-1. [CrossRef]

- Yasuda, S., Tsuchiya, H., Kaiho, A., Guo, Q., Ikeuchi, K., Endo, A., Arai, N., Ohtake, F., Murata, S., Inada, T., Baumeister, W., Fernández-Busnadiego, R., Tanaka, K., & Saeki, Y. (2020). Stress- and ubiquitylation-dependent phase separation of the proteasome. Nature, 578(7794), 296–300. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-020-1982-9. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).