1. Introduction

Food producers face serious challenges related to pesticide residues in fruits and vegetables. Continuous concern over this issue leads to production instability and reduced economic sustainability of production. As a result, farmers opt to cultivate other crops primarily to avoid these challenges and secondly due to lower profit caused by increased pesticide use. Additionally, unpredictable weather conditions, especially high temperatures and humidity, have great impact on production by creating conditions favorable for development of pest population.

For these reasons, farmers must be prepared to respond quickly and effectively at the first signs of disease. Conventional methods, such as using tractors and field crop sprayers, are not economical for treating small spots, as they take considerable time and require spraying of the entire area, including unaffected sections. In contrast, drones equipped with cameras can be used for both detection of localized infections and pesticide spraying. Drones for pesticide application can be used for several purposes and have a number of advantages [

1,

2]. First, drones are a significantly cheaper investment compared to tractors and field crop sprayers. In addition, using a drone for pesticide application can be a considerably cheaper alternative to using a tractor equipped with a field sprayer [

3,

4]. Second, apart from spraying, drones can be employed for monitoring and analyzing large agricultural areas for pest or weed infestations. Drones for pesticide spraying are typically equipped with a tank, nozzles, pumps, lines, hardware and GPS for precise application control. Operational parameters usually range around 1.15 ha/h, with an average speed of 4.45 m/s [

3,

5]. Spraying rate is lower compared to other methods, at 47 l/ha [

6] with a flow rate ranging from 0.6 l/min to 1.25 l/min [

7,

8]. However, certain limitations have been identified [

4], related to speed and total sprayed area. The cost of drone-based pesticide spraying can easily increase if spraying speed and altitude are too high. It was reported that drones are suitable for crop monitoring and small interventions in fertilization and crop protection [

9]. Other unmanned aerial vehicles, with autonomous flight and path control software, have also been tested for fertilization and crop spraying [

7]. It was observed that increasing drone flight altitude to 4 or 5 m resulted in a reduced swath width [

10].

Achieving high pesticide application efficacy is important not only for economic sustainability of crop and food production, but also for maintaining effective control over disease and weed populations. This can be accomplished only by using a properly calibrated sprayer. Sprayer calibration involves more than simply checking the pump flow rate, pressure, nozzle flow rate and distribution uniformity. It also requires optimizing pesticide distribution on the target area with minimal drift [

11,

12]. The primary goal is to distribute a sufficient amount of pesticide to the spraying target (weeds and pests) to eliminate them immediately. Otherwise, weed and pest populations may develop resistance to the pesticides.

To prevent pesticide resistance, it is important to consider different pesticide application technologies, while prioritizing prevention strategies over post-infestation treatments. Maximizing spraying deposition improves spraying efficiency while reducing spray drift, which is a challenge farmers constantly encounter throughout the growing season [

13]. To address these problems, numerous policies – many of which are found in EU regulations – recommend using calibrated unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs), such as drones [

14]. Using drones with sprayers can be an efficient way for pest control in fields [

15]. Over the years, drones have undergone many changes and advancements and their capabilities will keep expanding [

16]. Having low labor and human operational costs and causing no damage to the crops and no soil compaction from ground traffic, drones are expected to have even more significant role in future agriculture production. However, some researchers stay cautious about UAV efficiency. A study [

3] demonstrated that UAV ground operations accounted for 50% of the total working time, preparation and route planning required 10% each, while only around 30% of the working time was for spraying operations. For optimal spatial pests control aimed at preventing yield losses, minimizing drift is essential. There are several factors affecting drone deposition quality. The primary factor is wind, which can increase drift. In additional, evaporation drift must be considered, as small droplets are affected by high-speed airflow generated by drone turbines (smaller droplets have faster evaporation). These factors reduce pesticide efficacy and can potentially contribute to resistance development in weeds or pests. To minimize these effects, [

17] found that optimal application parameters for WPH642 unmanned aircraft were a flight altitude of 2 m and a flight velocity of 1.5 m/s. In another study testing two different drones with sprayers, [

18] reported that spray drift was possible due to small volume median diameter (VMD) of droplets during spraying. When droplets were smaller than 200 µm, drift became inevitable. Although the spray pattern reached swath widths of 5 m and 7 m, no drift measurements were recorded. The authors suggested that changing nozzles could reduce drift. A study by [

8] confirms that drones can be efficiently used for crop protection. When a UAV was operated at a fixed flight speed of 4 m/s and an altitude of 3.5 m, the droplets coverage rate on wheat canopy and the distribution uniformity were optimal. The ratio of droplets coverage rate between the lower layer and the canopy was 45.6%. The authors also stress that some auxiliary agents must be added to extend the retention period of the pesticide solution on crop surfaces to prolong the pesticide effect and improve pest control efficiency. In a study by [

19], it was reported that low flight altitudes (0.8 m) and drone velocity of 3 m/s resulted in coverage of approximately 6%. This very low coverage was attributed to wind drift, as higher speed reduces coverage to between 3% and 5%. The impact of drone turbines on pesticide losses is very high and using ultra-low volumes of pesticide further decreases the coverage. Moreover, the airflow from drone turbines significantly affects droplet penetration into the crops, especially along the edges of the spray area, making smaller droplets prone to drift. Although this airflow can have a positive effect on deposition and efficacy in some cases, it is important to minimize drift by using low-drift nozzles, such as air-injector nozzles [

20]. It is necessary to point out that smaller droplets contribute more significantly to treatment efficacy [

21].

However, certain factors have not been adequately considered in drone-based pesticide spraying. Successful prevention of diseases and weeds using field crop sprayers has become less economically sustainable due to the high cost of pesticides and the necessity to spray entire fields instead of only infested areas (which can be performed by drones). Effective pest control requires high spraying efficacy.

In India, conventional pesticide application methods result in excessive use of chemicals, lower spray uniformity, reduced deposition and coverage, leading to higher cost of pesticides and increased environmental pollution [

22]. Furthermore, these methods require increased drudgery in field application and result in reduced area coverage, leading to increased input costs as well as reduced efficiency in pest and disease control.

UAV-based remote sensing has transformed disease monitoring and crop protection by enabling

early detection, targeted treatment, and

data-driven decision-making. Traditional scouting methods are time-consuming and reactive, whereas drones equipped with multispectral sensors can detect stress indicators before visible symptoms appear, allowing for timely intervention [

41]. By analyzing

NDVI and

NDRE indices, UAVs precisely identify affected areas, reducing unnecessary pesticide applications and lowering costs [

42]. Precision spraying guided by drone mapping enhances application

efficiency, prevents pesticide resistance, and

minimizes environmental impact [

43]. Additionally, long-term UAV data facilitates

prediction of future outbreaks, contributing to improved disease management strategies [

44]. Integration of remote sensing technologies in modern agriculture enables

earlier, more precise, and cost-effective disease control, ensuring

sustainable crop production.

The application of UAV-based multispectral imaging has significantly advanced crop health monitoring and disease detection. By capturing and analyzing vegetation indices, such as NDVI and NDRE, it is possible to detect early stress symptoms in plants before they become visible, allowing for prompt intervention and more effective pest and disease management. In this study, multispectral imaging was employed to monitor crop conditions and assess pesticide application efficiency by analyzing spray drift [

39]. Integration of remote sensing technologies in precision agriculture is essential for optimizing input usage, reducing pesticide waste and enhancing overall crop productivity [

40].

2. Materials and Methods

The experiment was conducted using the Agras MG 1S drone, equipped with 8 rotors, providing a maximum trust of 24.5 kg. Maximum operation speed is 8 m/s and flight speed is 22 m/s. A sprayer system is mounted on the drone, with a 10-liter tank and 4 nozzles. The altitude stabilization system has a detection range of 1.5–7 m, an operational range of 2–3.5 m and detection accuracy <0.1 m. According to the manufacturer’s manual, the spray width ranges 4 – 6 m when the drone flight altitude is between 1.5 and 3 m.

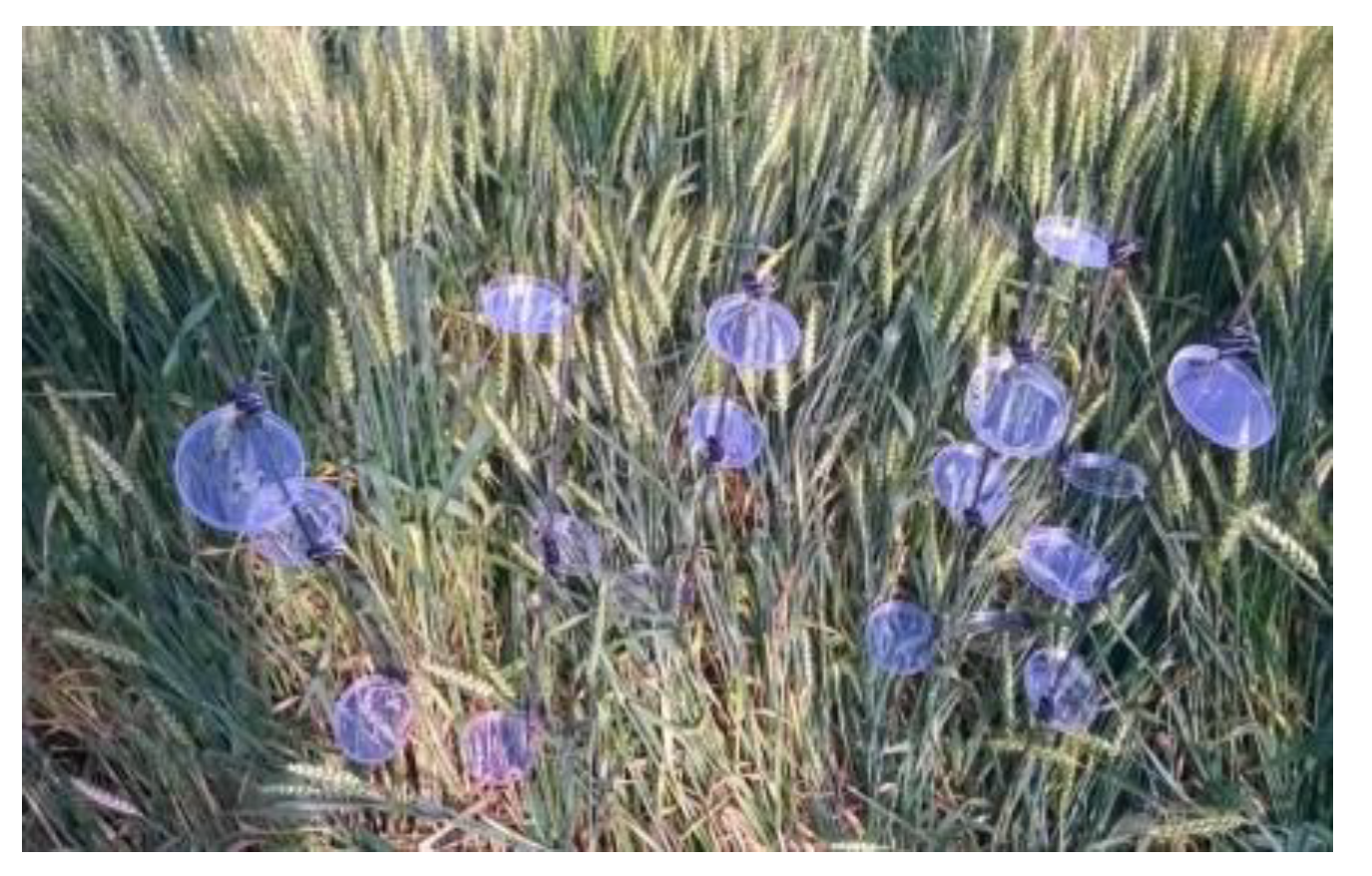

During the experiment, clean water was used together with a specific concentration of tracers. Brilliant Blue was used as the tracer at a concentration of 5 g/l. These tracers are employed to assess deposition levels on artificial targets on the ground. The artificial targets were plastic plates arranged in a 7x7 grid pattern, with one plate positioned at every 1 x 1 m (

Figure 1).

The spraying rate was 150 l/ha. Following the application, tracers were collected and washed with 0.025 l of deionized water. Absorbance was measured using the PhotoLab 6600 UV/VIS spectrophotometer at a wavelength of 627 nm, with a wavelength accuracy ±1 nm and a resolution of 1 nm.

For this experiment, the nozzles on the drone were replaced with different nozzle types to assess their impact on spray deposition. The first tested nozzle was the original flat fan nozzle (XR), with which the drone was initially equipped. This yellow-colored nozzle had a fan angle of 110o and a flow rate of 0.8 l/min at 3 bar, producing droplets with a volume median diameter of 190 µm. The second tested nozzle was an air-injector nozzle, the Compact Fan Air-T (CFA-T 110-02). This yellow-colored nozzle had a single flat fan rotated 13o backwards, a spraying angle of 110o, a flow rate of 1.2 l/min at 3 bar. It was made of molded Delrin acetal resin, producing very coarse droplets, with a volume median diameter of 368 µm. The third tested nozzle was an air-injector double flat fan nozzle. This Twin Fan Air (TFA) nozzle, also yellow-colored, had two flat fans positioned at a 30o angle to each other, a spraying angle of 120o, a flow rate of 1.2 l/min at 3 bar. It was also made of molded Delrin acetal resin, and produced extremely coarse droplets, with a volume median diameter of 525 µm. The drone speed was 2 m/s. The flight altitudes were set at 1.5 m, 3 m and 5 m above the ground, with the spraying rate of 150 l/ha.

The weather conditions were favorable, with a wind speed of approximately 1 m/s, humidity around 65% and temperature of 26.5 oC. The terrain was flat, with no inclination.

The collected data were processed using Wolfram Mathematica as a nested design. Computational models were developed to assess changes in deposition amounts.

In order to conduct remote disease detection, the DJI Phantom P4 drone equipped with a multispectral camera was used. Multispectral images were obtained using a six-channel camera, which included an RGB channel (visible spectrum), a Red channel at 650 nm ± 16 nm, a Blue channel at 450 nm ± 16 nm, a Green channel at 560 nm ± 16 nm, a near-infrared (NIR) channel at 840 nm ± 26 nm, and a RedEdge channel at 730 nm ± 16 nm. The wheat samples under observation were placed in 1 m² boxes. During imaging, the boxes were arranged in a row according to infection severity levels ranging from 0 to 4, based on the Stackman scale, where 0 represents healthy wheat and 4 indicates the highest level of infection. The drone was flown at an altitude of 15 meters, achieving a pixel resolution of 0.7 cm, which allowed for precise image analysis. After processing the images, vegetation indices were generated. The NDRE vegetation index represents the ratio between near-infrared (NIR) and visible red spectrum reflectance of plants. The healthier the plant, the greater the difference between the reflectance of these two channels (with a stronger near-infrared signal), resulting in a higher index value. The NDVI is a remote sensing metric used to assess vegetation health by analyzing the difference between near-infrared (NIR) and red light reflectance. Higher NDVI values indicate healthy, dense vegetation, while lower values suggest stress, disease, or poor plant coverage. For multispectral image analysis, five specific points were selected within each box to extract vegetation index values. These values were used to estimate the health status of wheat and examine the correlation between disease severity and index fluctuations. The collected data provided a basis for evaluating crop stress levels and determining the potential need for intervention.

3. Results

Data collected from artificial targets were first classified using a nested data design [

23,

24,

25]. The data were processed in Wolfram Mathematica 10 to generate surfaces and develop models describing deposition variations influenced by two factors: flight altitude and nozzle type. Accordingly, the data were classified with two levels of factors: flight altitude (h), nozzle type (R), with the dependent variable being deposition (Y). A nested design was formed, wherein nozzle type was nested within flight altitude (h(R)), indicating that deposition (Y) is nested within both nozzle type and flight altitude (h(R*Y)). Statistical analysis was performed using Statistica 13 software following the same nested design structure.

Table 1 presents the average tracer deposition on artificial targets depending on nozzle type and flight altitude. When using a flat fan nozzle (XR), the deposition reached 12.69% of the total deposition at a flight altitude of 1.5 m. As the flight altitude increased, deposition decreased to 7.34% at 3 m and further declined to 1.77% at 5 m. This means that a drift was more than 98%. A higher average deposition was recorded with the CFAT nozzle, reaching 16.51% at 1.5 m flight altitude with 6 m boom width. Changes in flight altitude had no dramatic effect on the deposition, with only 23.4% reduction at 5 m altitude. The highest average deposition was observed using the air-injector double flat fan nozzle (TFA), with more than 34%. When the flight altitude increased, the average deposition remained high, 30.51% at 3 m and 20.86% at 5 m. Statistical data processing included testing all effects, assessing homogeneity of variances and significance using Duncan test for the nested design (h(R*Y)). The results indicate, with 95% confidence, that flight altitude and nozzle type affect the average deposition and spraying distribution uniformity. Homogeneity of variance was not observed. Duncan test confirmed, with 95% confidence, that the highest average deposition was achieved using the TFA nozzle, especially at lower altitudes. The lowest average deposition was recorded for the XR nozzle at 3 m and 5 m. These findings are consistent with the droplet size of the tested nozzles [

26,

27].

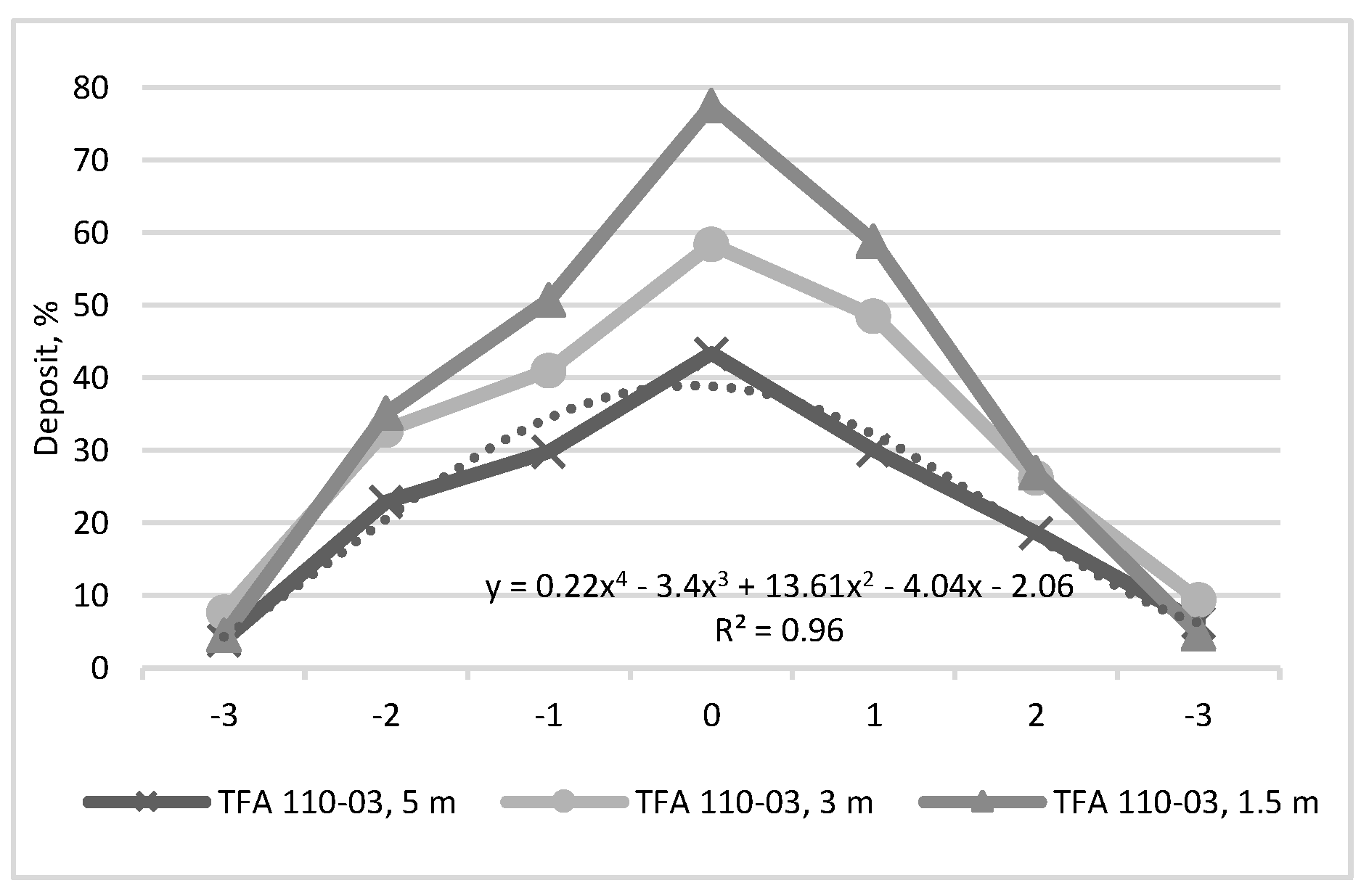

The variations in deposition distribution uniformity for the tested nozzles at different altitudes collected on artificial targets are presented in

Figure 2,

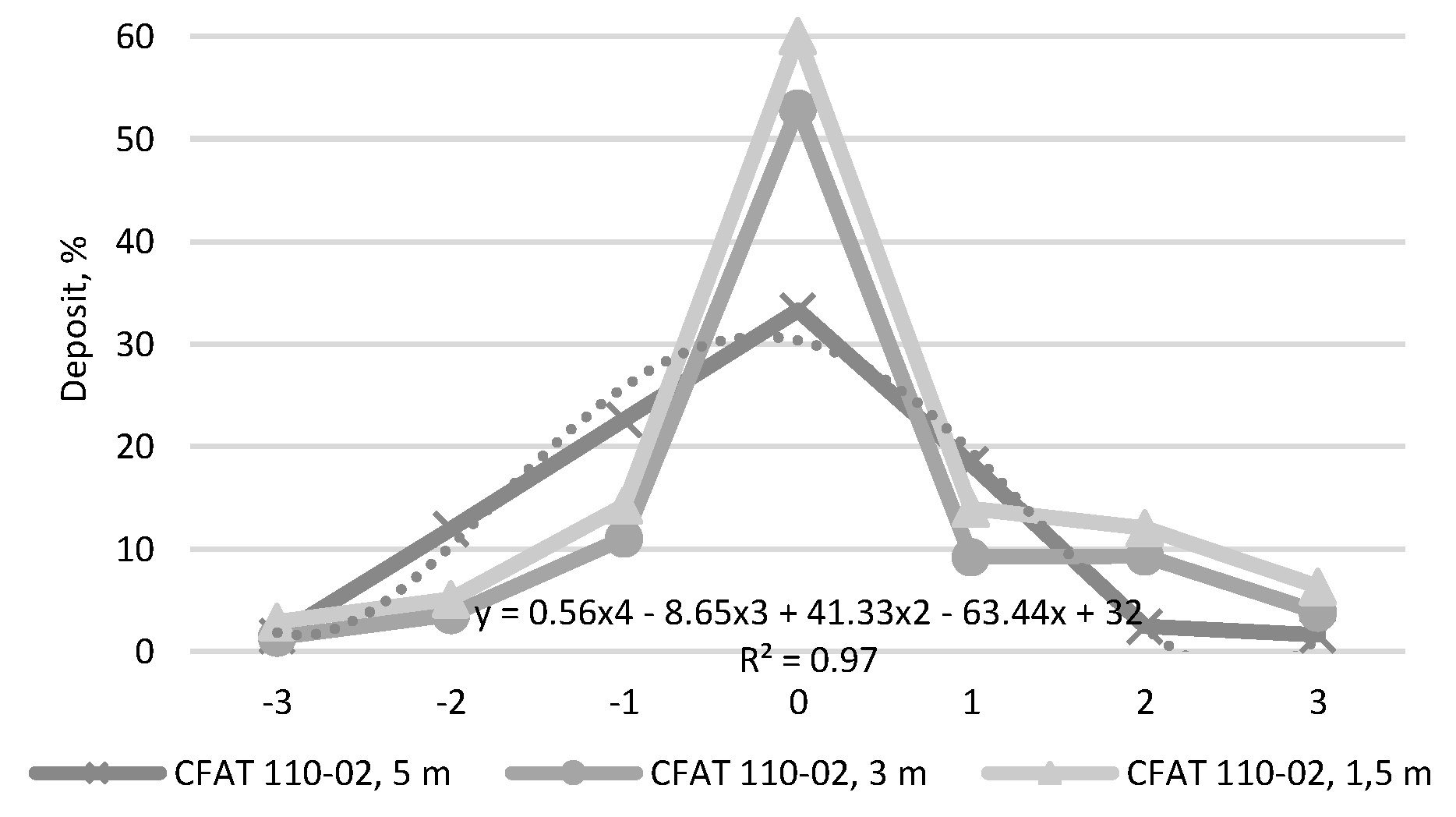

Figure 3 and

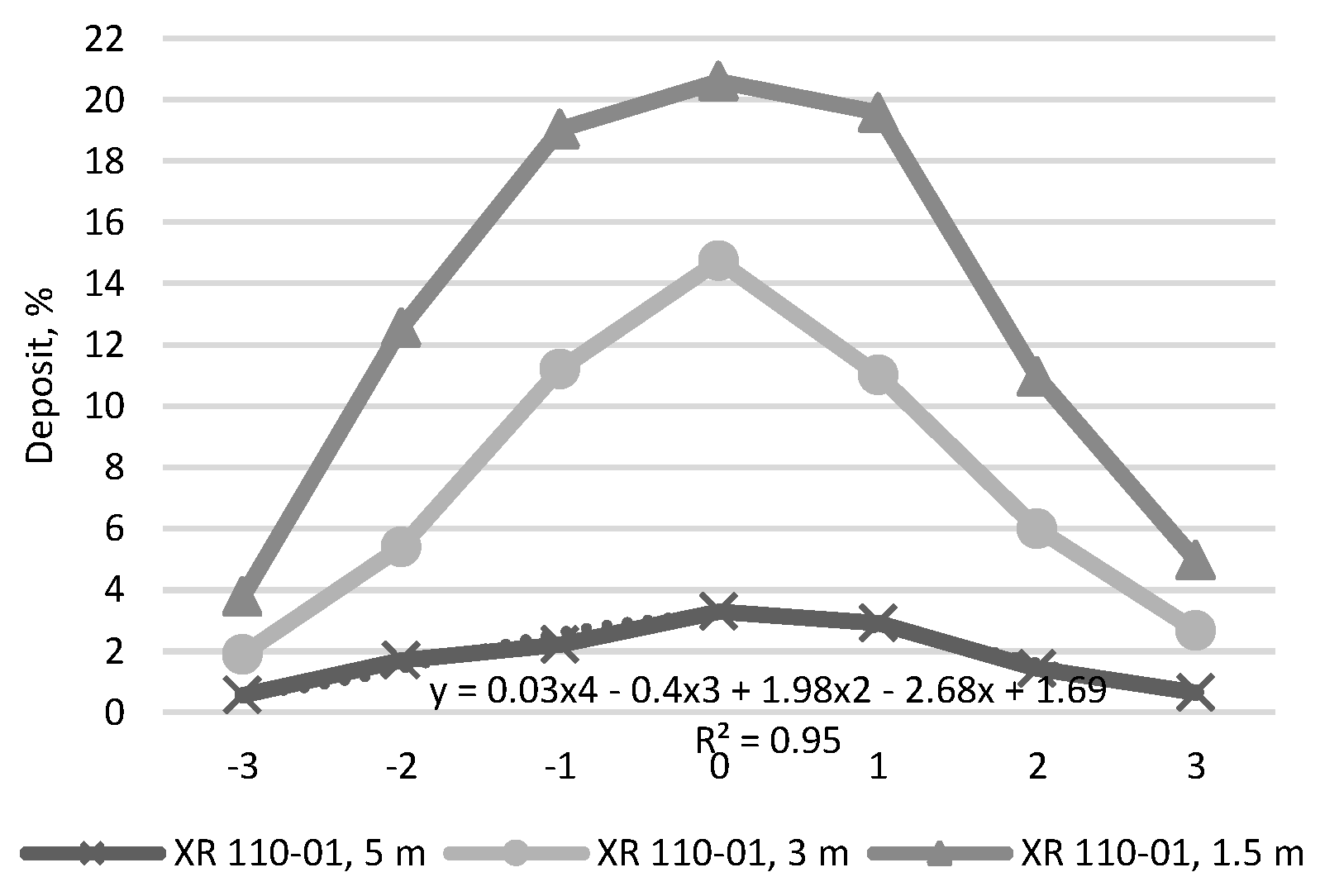

Figure 4.

Figure 2 presents the deposition of the air-injector nozzle with two flat fans (TFA), showing that this nozzle achieves the highest deposition, up to 80%, at the center of spraying. However, uniformity is not achieved. The same pattern is observed with the other two tested nozzles. The deposition for the air-injector nozzle with a single flat fan is over 60% at 1.5 m flight altitude, similar to the TFA nozzle. Deposition distribution declines drastically as the spray width changes. Total deposition remains above 50% at 2 m spray width and above 40% at 4 m spray width. However, the XR nozzle shows a distinct distribution pattern, with a maximum total deposition of approximately 20%. The most important characteristic is illustrated in

Figure 4, showing that the distribution curve of XR nozzle is more spherical compared to other two nozzles. This is attributed to the smaller, more drift-prone droplets, which are spread more widely by the drone vortex. This effect is particularly evident in this case. In contrast, the graph for the CFAT nozzle (

Figure 3) is not spherical at all, as this nozzle produces much larger droplets that are less drift-prone [

28]. These droplets are concentrated in the centre as they are heavier and fall directly onto the targets. The TFA nozzle is at the centre of the spherical curve as it produces medium-coarse droplets. As the XR nozzle generates fine droplets, drift is further increased under the influence of the drone vortex [

29]. In addition, very fine droplets evaporate almost immediately due to evaporation drift generated by the drone engine blades.

As the highest deposition is achieved at lower flight altitudes, a fitted curve can be useful to drone operators. This approach can be used for development of predictive models for pesticide deposition. Such models can help farmers in enhancing spraying efficacy and optimizing cost-effectiveness of pesticide application. The three models presented in this study are suitable for evaluation of pesticide distribution quality during spraying with three tested nozzle types at a flight altitude of 1.5 m. To apply these models, farmers need to substitute variable

x with the flight altitude and variable

y with the maximum spray width. The calculated value

z will predict the average deposition for a given flight altitude and spraying width (Eq. 1, 2, 3).

In addition to the previously presented models, effective plant protection using drones also requires monitoring crop health in accordance with time-based models for predicting disease occurrence.

Table 2 presents the average NDRE and NDVI values for each infection level, derived from five measurement points per box. The results indicate a gradual decline in both indices as infection severity increases, demonstrating a strong correlation between the vegetation indices and crop health. At the lowest infection level (0), the NDRE index is 0.46, while the NDVI index is 0.87, indicating healthy vegetation. As the infection progresses, these values steadily decline, reaching 0.20 for NDRE and 0.62 for NDVI at the highest infection level (4). This trend suggests that multispectral imaging can effectively detect early signs of plant stress, enabling timely disease management interventions. These findings emphasize the importance of remote sensing in precision agriculture, as vegetation indices provide an objective measure of crop health. By integrating NDVI and NDRE analysis with pesticide application strategies, it is possible to optimize treatments and improve efficiency while minimizing environmental impact.

4. Discussion

Although drones currently do not play a major role in pesticide application, their use is expected to increase due to changes in environmental protection regulations [

1]. Despite certain limitations, drones have significant advantages. Apart from their capacity to operate at high speed, fly safely and carry cargo, drones provide benefits such as low energy consumption, no gas emissions, minimal environmental impact. They enable targeted spraying, fertilizing small areas and real-time crop monitoring. Furthermore, they are user-friendly, equipped with automated controls and efficient and stable performances [

30,

31,

32,

33]. Regulations force farmers to reduce pesticide use to ensure production of safer food products. Pesticide residues have become a significant concern, especially because many fruits and vegetables are consumed without processing. Drones can be used for monitoring field crops to support efforts in reducing pesticide application [

34,

35]. By implementing good agricultural practices in drone-based pesticide application, pesticides can be sprayed preventively, before disease outbreaks. This approach allows drones to spray only high-risk areas where pests are likely to occur. Thus, instead of spraying full doses of pesticides, drones enable significant reductions of pesticide use as only zones at high risk of disease and pest infestation are sprayed [

36,

37,

38].

In addition, using drones for remote monitoring in agriculture enables real-time crop health assessment, facilitating early disease detection and precision interventions. Multispectral imaging, using vegetation indices such as NDVI and NDRE, is used to assess crop health. It allows for precise evaluation of infection severity and stress levels through multiple measurement points per plot. By integrating remote sensing with drift analysis, this approach optimizes pesticide application by ensuring timely and site-specific treatments. Overall, drones contribute to reduced pesticide usage, while minimizing environmental impact and enhancing efficiency in disease and pest management, which positions them as one of the key tools in modern precision agriculture [

43].

5. Conclusions

Environmentally sustainable use of pesticides can now be achieved with advanced application methods. Although pesticides will continue to be used for pest control, their application can be significantly reduced. Drone-based pesticide application is a highly efficient method for pest control that also minimizes crop damage and yield loss. Appropriate use of drones contributes to the efficacy of pesticide application, ensuring more cost-effective and profitable crop production. The experiment results show that an optimal flight altitude for drone-based pesticide application is approximately 1.5 m above the targeted crops or area. Furthermore, problems related to spray drift can be mitigated by using air-injector nozzle with two flat fans, which improves spray deposition. Medium-coarse or coarse spray droplets sizes are more suitable, as they improve distribution uniformity and significantly reduce drift, especially wind drift caused by drone engines blades. Using extremely coarse sprayer droplets is not suitable for this type of pesticide application equipment. Achieving nearly 80% of total deposition and over 50% within 2 m spray width is considered as good pesticide efficacy. It should be emphasized that drone-based pesticide application must be conducted with pesticides registered for this purpose and in accordance with national regulations related to the use of aerial application in plant protection.

Apart from pesticide application, drones have become an essential tool in remote crop monitoring, enabling early disease detection, optimized resource management and improved agricultural sustainability. Their ability to provide real-time, high-resolution data enhances decision-making in precision agriculture, leading to greater efficiency, lower costs and reduced environmental impact. Multispectral imaging was employed to assess vegetation indices, providing valuable insights into crop health. By analyzing NDRE and NDVI indices, early signs of plant stress and potentially infected zones can be identified, allowing for timely intervention and precise pesticide application. This targeted approach ensures that pesticides are applied only in high-risk areas. This method not only reduces the overall pesticide use, but also enhances application accuracy, minimizes environmental impact and improves overall disease management efficiency. By integrating drone-based spraying with multispectral monitoring, this approach contributes to a more sustainable and efficient agricultural system, leading to improved crop health and better resource utilization.

Author Contributions

“Conceptualization, V.V. and A.S.; methodology, V.V. and A.S.; software, V.V.; validation, F.V., L.T. and L.P.; formal analysis, V.V.; investigation, V.V. and F.V.; resources, A.S.; data curation, L.T.; writing—original draft preparation, V.V., L.P. writing—review and editing, V.V., A.S. and F.V.; visualization, L.P.; supervision, L.P.;

Acknowledgments

This publication is part of the TALLHEDA project that has received funding from the European Union's Horizon Europe research and innovation programme under grant agreement No. 101136578 funded by the European Union. Views and opinions expressed are however those of the author(s) only and do not necessarily reflect those of the European Union or the European Research Executive Agency (REA). Neither the European Union nor the granting authority can be held responsible for them.

Conflicts of Interest

“The authors declare no conflict of interest.”.

References

- Wang S L, Song J L, He X K, Song L, Wang X N, Wang C L, et al. Performances evaluation of four typical unmanned aerial vehicles used for pesticide application in China. Int J Agric & Biol Eng, 2017; 10(4): 22–31.

- Mogili, U.R.; Deepak, B.B.V.L. Review on Application of Drone Systems in Precision Agriculture. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2018, 133, 502–509. [CrossRef]

- Yallappa, D.; Veerangouda, M.; Maski, D.; Palled, V.; Bheemanna, M. Development and evaluation of drone mounted sprayer for pesticide applications to crops. In Proceedings of the GHTC 2017—IEEE Global Humanitarian Technology Conference, San Jose, CA, USA, 19–22 October 2017; pp. 1–7. [CrossRef]

- Wang X N, He X K, Wang C L, Wang Z C, Li L L, Wang S L, et al. Spray drift characteristics of fuel powered single-rotor UAV for plant protection. Transactions of the CSAE, 2016; 32(17): 40–46. (in Chinese).

- Kabra, T. S., Kardile, A. V., Deeksha, M. G., Mane, D. B., Bhosale, P. R., & Belekar, A. M. (2017) Design, Development & Optimization of a Quad-Copter for Agricultural Applications. International Research Journal of Engineering and Technology (IRJET) e-ISSN: 2395-0056 Volume: 04 Issue: 07.

- Giles, D. K., & Billing, R. C. (2015) “Deployment and Performance of a UAV for Crop Spraying.” Chemical Engineering Transactions, 44, pp.307-322.

- Xue, X.; Lan, Y.; Sun, Z.; Chang, C.; Hoffmann, W.C. Develop an unmanned aerial vehicle based automatic aerial spraying system. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2016, 128, 58–66. [CrossRef]

- Qin, W.; Xue, X.; Zhang, S.; Gu, W.; Wang, B. Droplet deposition and efficiency of fungicides sprayed with small UAV against wheat powdery mildew. Int. J. Agric. Biol. Eng. 2018, 11, 27–32. [CrossRef]

- Kale, S., Khandagale, S., Gaikwad, S., Narve, S. and Gangal, P., 2015, Agriculture drone for spraying fertilizer and pesticides. Int. J. Adv Res in Computer Sci. and Software Eng., 5(12): 804-807.

- Zhang D Y, Chen L P, Zhang R R, Xu G, Lan Y B, Hoffmann W C, et al. (2015). Evaluating effective swath width and droplet distribution of aerial spraying systems on M-18B and Thrush 510G airplanes. Int J Agric & Biol Eng, 2015; 8(2): 21–30. [CrossRef]

- Zhang P, Deng L, Lv Q, He S, Yi S, Liu Y, et al. Effects of citrus tree-shape and spraying height of small unmanned aerial vehicle on droplet distribution. Int J Agric & Biol Eng, 2017; 33(1): 117–123.

- Zhang S C, Xue X Y, Qin W C, Sun Z, Ding S M, Zhou L X. Simulation and experimental verification of aerial spraying drift on N-3 unmanned spraying helicopter. Transactions of the CSAE, 2015; 31(3): 87–93. (in Chinese).

- Jiao L Z, Dong D M, Feng H K, Zhao X D, Chen L P. Monitoring spray drift in aerial spray application based on infrared thermal imaging technology. Computers and Electronics in Agriculture, 2016; 121: 135–140.

- Huang Y B, Thomson S J, Hoffmann W C, Lan Y B, Fritz B K. Development and prospect of unmanned aerial vehicle technologies for agricultural production management. Int J Agric & Biol Eng, 2013; 6(3): 1–10.

- Xue X Y, Lan Y B. Agricultural aviation applications in USA. Transactions of the CSAM, 2013; 44(5): 194–201. (in Chinese).

- Lan Y B, Chen S D, Fritz B K. Current status and future trends of precision agricultural aviation technologies. Int J Agric & Biol Eng, 2017; 10(3): 1–17.

- Zhang J., Xuechao he, J. Song, Aijun Zeng, (2012): Influence of Spraying Parameters of Unmanned Aircraft on Droplets Deposition. Transactions of the Chinese Society of Agricultural Machinery, 43(12): 94-96, 2012. [CrossRef]

- Woldt, W.; Martin, D.; Lahteef, M.; Kruger, G.; Wright, R.; McMechan, J.; Proctor, C.; Jackson-Ziems, T. Field Evaluation of Commercially Available Small Unmanned Aircraft Crop Spray Systems. 2018 Detroit, Michigan July 29 - August 1, 2018. LOCATION OF CONFERENCE, COUNTRYDATE OF CONFERENCE; p. 1.

- Qin, W.-C.; Qiu, B.-J.; Xue, X.-Y.; Chen, C.; Xu, Z.-F.; Zhou, Q.-Q. Droplet deposition and control effect of insecticides sprayed with an unmanned aerial vehicle against plant hoppers. Crop. Prot. 2016, 85, 79–88. [CrossRef]

- Chen S D, Lan Y B, Li J Y, Zhou Z Y, Liu A M, Mao Y D. Effect of wind field below unmanned helicopter on droplet deposition distribution of aerial spraying. Int J Agric & Biol Eng, 2017; 10(3): 67–77.

- Chen, P.; Lan, Y.; Huang, X.; Qi, H.; Wang, G.; Wang, J.; Wang, L.; Xiao, H. Droplet Deposition and Control of Planthoppers of Different Nozzles in Two-Stage Rice with a Quadrotor Unmanned Aerial Vehicle. Agronomy 2020, 10, 303. [CrossRef]

- Saddam Hussain; Cheema, M. J. M.; Arshad, M.; Ashfaq Ahmad; Latif, M. A.; Shaharyar Ashraf; Shoaib Ahmad. (2019). Spray uniformity testing of unmanned aerial spraying system for precise agro-chemical applications. Pakistan Journal of Agricultural Sciences, ISSN 0552-9034 vol. 56(4): 897-903.

- Schielzeth, H.; Nakagawa, S. Nested by design: model fitting and interpretation in a mixed model era. Methods Ecol. Evol. 2012, 4, 14–24. [CrossRef]

- Goldstein, H. (2011) Multilevel Statistical Models, 4th edn. Wiley, Oxford.

- Algina, J. & Swaminathan, H. (2011) Centering in two-level nested designs. Handbook of Advanced Multilevel Analysis (eds J.J. Hox & J.K. Roberts), pp. 285–312. Routledge, New York, New York.

- Fritz, B.K.; Hoffmann, W.C. Measuring Spray Droplet Size from Agricultural Nozzles Using Laser Diffraction. J. Vis. Exp. 2016, e54533. [CrossRef]

- Kooij, S.; Sijs, R.; Denn, M.M.; Villermaux, E.; Bonn, D. What Determines the Drop Size in Sprays?. Phys. Rev. X 2018, 8, 031019. [CrossRef]

- Vallet, A.; Tinet, C. Characteristics of droplets from single and twin jet air induction nozzles: A preliminary investigation. Crop. Prot. 2013, 48, 63–68. [CrossRef]

- Al Heidary, M.; Douzals, J.; Sinfort, C.; Vallet, A. Influence of spray characteristics on potential spray drift of field crop sprayers: A literature review. Crop. Prot. 2014, 63, 120–130. [CrossRef]

- Krisna, V., et al., 2016, ‘Unmanned aerial vehicle in the field of agriculture, Frontiers of Current Trends in Engineering and Technology, pp. 91-96.

- Figliozzi, M.A. Lifecycle modeling and assessment of unmanned aerial vehicles (Drones) CO2e emissions. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2017, 57, 251–261. [CrossRef]

- Arena, M.; Auteri, D.; Barmaz, S.; Bellisai, G.; Brancato, A.; Brocca, D.; Bura, L.; Byers, H.; Chiusolo, A.; Marques, D.C.; et al. Guidance on the assessment of exposure of operators, workers, residents and bystanders in risk assessment for plant protection products. EFSA J. 2014, 12. [CrossRef]

- Giles D., Billing R., 2015, Deployment and performance of a uav for crop spraying, Chemical Engineering Transactions, 44, 307-312. [CrossRef]

- Fritz, B.K.; Hoffmann, W.C.; Bagley, W.E.; Hewitt, A. Field Scale Evaluation of Spray Drift Reduction Technologies from Ground and Aerial Application Systems. J. ASTM Int. 2011, 8, 1–11. [CrossRef]

- Tang Q, Zhang R R, Chen L P, Xu M, Yi T C, Zhang B. Droplets movement and deposition of an eight-rotor agricultural UAV in downwash flow field. Int J Agric & Biol Eng, 2017; 10(3): 47–56. [CrossRef]

- Xinyu, X., Kang., Weicai, Q., Lan, Y. and Huihui Zhang, 2014, Drift and deposition of ultra-low altitude and low volume application in paddy field. Int. J. Agric. Biol. Eng., 7(4): 23-28.

- Lou, Z.; Xin, F.; Han, X.; Lan, Y.; Duan, T.; Fu, W. Effect of Unmanned Aerial Vehicle Flight Height on Droplet Distribution, Drift and Control of Cotton Aphids and Spider Mites. Agronomy 2018, 8, 187. [CrossRef]

- Wang G B, Li X H, Ren W Y, Dai H B, Cui Z L, Zhou Y Y, et al. Detection of spraying quality and observation of control effect on rice blast using two kinds of helicopter in paddy field. China Plant Protection, 2014; 34(S1): 6–11. (in Chinese).

- Vasić, Filip. Application of Precision Agriculture Technologies in Wheat Protection. University of Novi Sad, Faculty of Agriculture, Novi Sad, 2022.

- Smith, John; Doe, Jane. Drones in Precision Agriculture: A Comprehensive Review of Technological Advancements and Future Directions. Drones, 2024, 8(11), 686.

- Thompson, L., & Wang, M. (2021). Early Detection of Crop Diseases Using Multispectral Imaging from UAVs. Plant Health Progress, 22(3), 150-160.

- Johnson, A., & Lee, B. (2023). Advancements in UAV Remote Sensing for Crop Health Monitoring. Agricultural Research Journal, 15(4), 234-245.

- Smith, J., & Doe, J. (2024). Drones in Precision Agriculture: A Comprehensive Review of Technological Advancements and Future Directions. Drones, 8(11), 686.

- Davis, K., & Patel, R. (2020). Yield Prediction and Assessment through Aerial Imagery in Agriculture. International Journal of Agricultural Science, 18(1), 45-58.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).