Introduction

Vermicomposting is considered a "protective, restorative, and environmentally sustainable" method because it helps divert waste from landfills while producing organic fertilizer that supports soil health and agricultural growth [

11]. The use of bins to create a controlled vermicomposting system is a relatively recent development, originating from a small group of pioneers [

25]. Vermicomposting produces high-quality organic fertilizer while also minimizing organic waste by converting it into a soil conditioner that enriches and enhances soil biodiversity [

21]. Vermicomposting boosts plant growth by 50–100% more than traditional compost and 30%–40% more than synthetic fertilizers. In addition to enriching the soil with organic carbon, vermicompost provides essential and trace nutrients, along with hormones, vitamins, and enzymes that support plant growth [

21].

The most recent experiments reported by concerned researchers [

3,

4,

5,

8] Studies have highlighted the potential benefits of vermicomposting for plant growth. The process of vermicomposting, facilitated by earthworms, results in the production of macro- and micro-nutrients, growth-regulating hormones, growth promoters, plant-associated microbes, and enzymes like lipase, chitinase, amylases, proteases, and cellulases. These enzymes continue to break down organic materials even after being secreted by the earthworms [

24].

arthworms modify the chemical and physical properties of organic matter, gradually lowering its carbon-to-nitrogen ratio. This enhances the surface area available for microorganisms, boosting the potential for further microbial degradation. The addition of vermicompost improves the organic content, structure, texture, and pH of the soil. Moreover, it helps maintain favorable environmental conditions, such as soil moisture and temperature [

20]. The movement of small organic particles and bacterial waste through the earthworm’s gut leads to a uniformity in the organic substrates. The end product of vermicomposting is a finely broken-down, humus-like organic material that has high porosity and water retention. This material is rich in essential nutrients and minerals, such as nitrate and ammonium, which are readily available for plants [

3,

4,

5].

Furthermore, the

Eisenia fetida species is highly adaptable to fluctuations in moisture and temperature. Notable traits of

Eisenia fetida include rapid growth, early sexual maturity, year-round activity, a high feeding capacity (resulting in quick casting), and extensive reproductive abilities. As a result, it has been extensively used in the vermicomposting of various plant residues, animal manure, municipal waste, and sewage sludge [

2].

Ethiopia’s surface water quality is rapidly deteriorating due to uncontrolled urbanization, waste dumping, and population growth. While soil fertility in the region is often declining, these valuable resources are frequently discarded without proper use. However, the use of the epigeic earthworm

Eisenia fetida has shown promise in breaking down various solid wastes, presenting a potential solution for improving Ethiopia’s solid waste management and producing high-quality bio- fertilizers for agricultural purposes [

1].

This study aims to evaluate Evaluation of Nitrogen, phosphorous and potassium of some crops straw and their corresponding vermicompost using Eisenia fetida in Bedele District, Buno Bedele zone, Oromia regional state, south west Ethiopia.

Materials and Methods

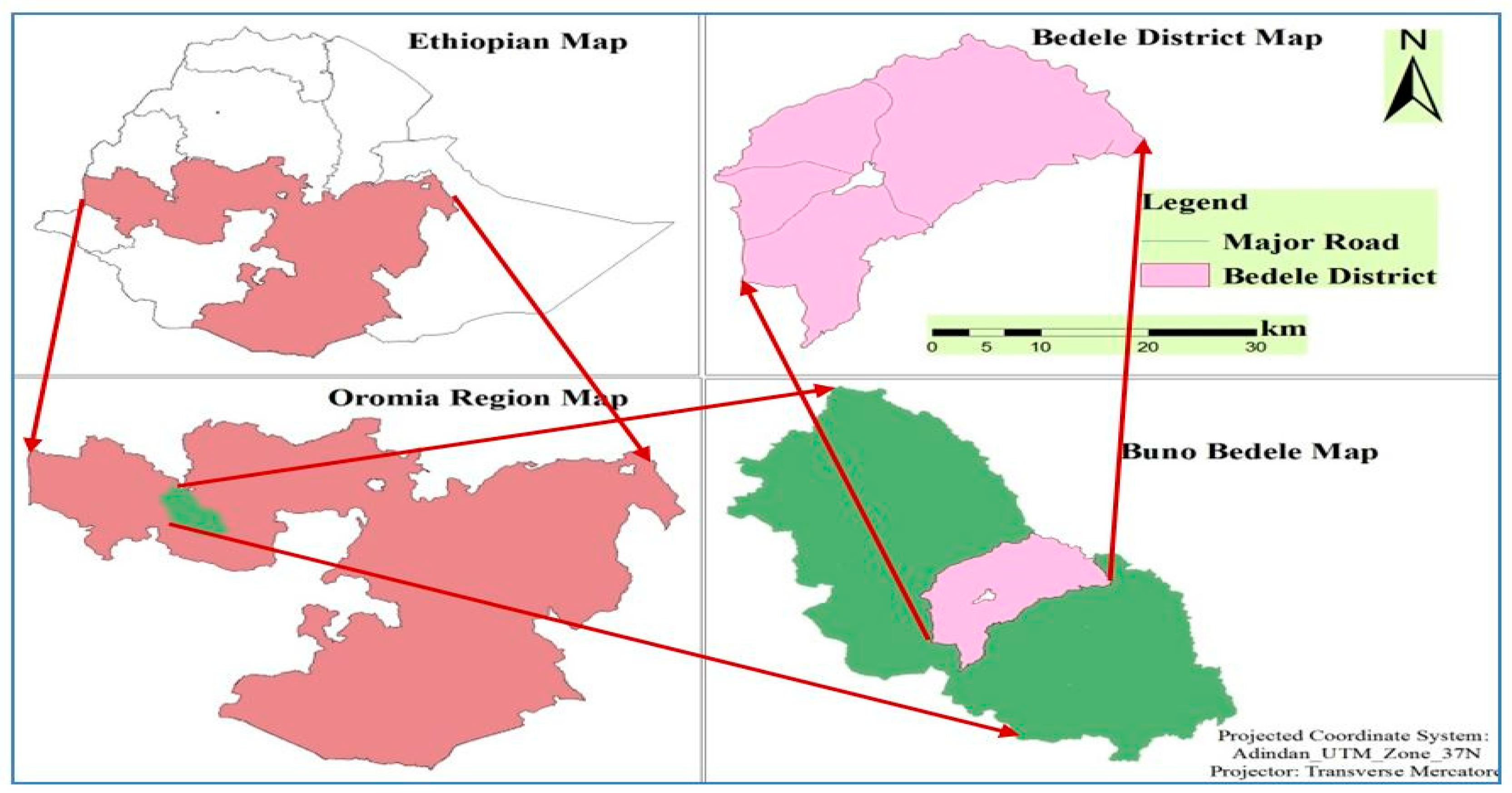

Bedele district is one of the nine districts in the Buno Bedele zone of the Oromia regional state, located in southwestern Ethiopia, approximately 436 km from Addis Ababa. The district lies between 8°14’30’’N and 8°37’53’’N latitude, and 36°13’17’’E and 36°35’05’’E longitude. It features a traditional agro-climatic zone, with elevations ranging from 1,013 to 2,390 meters above sea level. The district spans an area of 770.75 km² and includes 41 Peasant Associations (PAs). The physical landscape of the district is marked by rugged terrain, with predominantly gentle slopes and some steep areas, ranging from 2% to 45% in gradient.

The district is distinguished by three main types of landscapes: plateau plains with moderate elevation, moderately dissected hills and side slopes with a wide range of elevations, and lowland plains, such as the Didessa Valley, which reaches the lowest elevation. The varying landscape features in the study area correspond to changes in altitude. This diversity in landscapes and elevations is associated with different landform categories and soil types. In the plateau and moderately dissected hills and slopes, the dominant soil types are Dystric Nitisols and Latosols on the steeper areas. In the lowland plains of the Didessa Valley,

Pellic Vertisols are the most common soil type [

31].

Figure 1.

Map of study area.

Figure 1.

Map of study area.

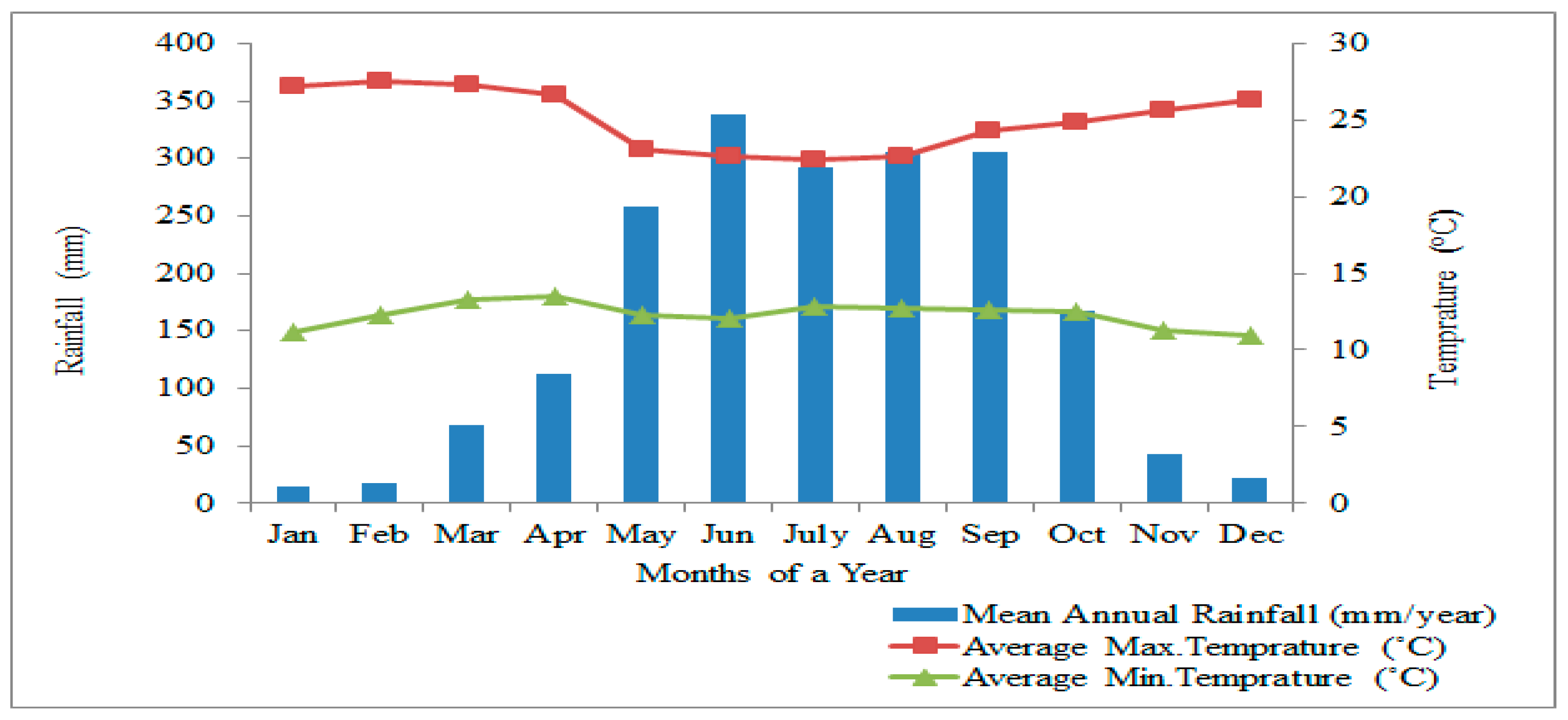

Climatic data spanning twenty years (1997-2016) indicates that the study area experiences a unimodal rainfall pattern, with the peak rainfall occurring from May to September. The average annual precipitation is 1,944.9 mm, showing significant variability from year to year. The mean annual temperatures range from a minimum of 12.9°C to a maximum of 25.8°C. The hottest months are from November to April, with maximum temperatures reaching up to 27.5°C, while the coldest months are from November to January, with minimum temperatures dropping to 10.9°C [

30].

Figure 2.

Climatic data of monthly mean rainfall, minimum and maximum temperature of the study area. Source: Ethiopian Meteorological Agency, Bedele District.

Figure 2.

Climatic data of monthly mean rainfall, minimum and maximum temperature of the study area. Source: Ethiopian Meteorological Agency, Bedele District.

Experimental Design

Local vermicomposting bins was prepared from plastic by removing its one side. Three bins were prepared depending on types of crop residue and size of the bin was 40*70cm2.

Preparation of crop residue for vermicomposting and laboratory analysis

The field pea (Pisum sativum) residue was first cleared of any foreign materials. It was then chopped, and 0.125 kg of the residue was measured out. The chopped residue was moistened appropriately and placed into bin number one for vermicomposting. Additionally, 2 grams of the field pea residue were ground for laboratory analysis of NPK (nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium).

The Noug (Guizotia abyssinica) residue was cleaned of any foreign materials, and 0.125 kg of properly moistened Noug residue was transferred to bin number two for vermicomposting. The Noug straw was left unchopped as it is neither fibrous nor tough. Additionally, 2 grams of ground Noug residue were prepared for laboratory analysis of NPK.

The Teff hay (Eragrostis tef) was cleaned and chopped to make it suitable for worms. A 0.125 kg portion of properly moistened Teff hay was then transferred to bin number three for vermicomposting. Additionally, 2 grams of the Teff hay were ground using a machine for laboratory analysis of NPK.

Importing of Eisenia fetida for vermicomposting

Three hundred twenty fetida species could be transferred to field pea residue in local bin number one.

Three hundred Eisenia fetida was transferred to noug residue in local bin number two.

Three hundred twenty Eisenia fetida worm species could be transferred to teff hay in local bin number three.

Material Collection and Preparation

Once threshing was completed, communication was made with farmers from Digaja and Yabala districts to collect crop residues. The crops were threshed using traditional methods, and the residues were gathered near the farmers’ homes. Straw from various crop residues was purposefully collected from the farmers’ fields. Teff hay was collected from Yabala district, while Noug and field pea residues were collected from fields in Digaja district. Approximately 2 kg of each type of residue was gathered, prepared for both laboratory analysis and vermicomposting. For laboratory analysis of NPK, the residues were oven-dried at 65°C for one day and then ground using a machine. For vermicomposting, the residues were chopped into small pieces to make them suitable for the worms. Three local bins were prepared for vermicomposting with Eisenia fetida worms. The chopped, moistened crop straw was added to each bin, and the worms were introduced into each box separately.

Data Source and Data Analysis

Data source is primary and experimental analysis. According to NSRC (2000), Analysis of N, P and K of crop straw and vermicompost was done and calculated.

Chemical Analysis

According to NSRC (2000), both crop residue and vermicompost were analyzed. For nitrogen determination, a 0.1g sample was digested with a strong acid. The resulting digest was distilled and collected in boric acid, then titrated with a strong acid. For phosphorus and potassium determination, a 1g sample was calcined (converted to ash) in a muffle furnace. The calcined sample was then dissolved in nitric acid and filtered into a 100ml volumetric flask. Phosphorus was measured using the methavanadate spectrometric method, while potassium was determined by flame photometry.

Result and Discussion

Analyzed PH, rate of decomposition, Total Nitrogen (TN), Total Phosphorus (TP), Total Potassium (TK), Total Organic Matter (TOC), the data are presented in

Table 1 and

Table 2.

PH. he data shows that after 32 days of successful vermicomposting, the pH of the final product fell within the neutral range (7.0 – 7.5). The highest pH, 7.5, was observed in T1, while T3 had a pH of 7.2, and T2 recorded the lowest pH of 7.0. The release of organic acids, ammonia, and CO2, combined with the activities of microorganisms and earthworms, contributed to the shift in pH towards a neutral or slightly acidic level throughout the vermicomposting process [

19,

23,

27,

28,

29].

Table 1.

Nutrient content of residues before Vermicompost.

Table 1.

Nutrient content of residues before Vermicompost.

| Treatment |

PH |

Total N (%) |

Total P (%) |

Total K (%) |

| T1 |

7.5 |

0.981 |

0.08 |

1.25 |

| T2 |

7.0 |

1.90 |

0.13 |

1.16 |

| T3 |

7.2 |

1.42 |

0.05 |

1.49 |

Table 2.

Nutrient content in prepared Enriched Vermicompost .

Table 2.

Nutrient content in prepared Enriched Vermicompost .

| Treatment |

PH |

Total N (%) |

Total P (%) |

Total K (%) |

| T1 |

7.5 |

2.56 |

0.27 |

4.4 |

| T2 |

7.0 |

2.87 |

0.15 |

1.85 |

| T3 |

7.2 |

2.28 |

0.3 |

4.05 |

| C.D5% |

0.35 |

0.28 |

0.32 |

0.08 |

Rate of decomposition. As indicated in

Table 1 and

Table 2 In T2 (

Guizotia abyssinica) that there was a gradual increase in weight gain from week one (0.25kg) to week five (32th days) (0.5kg) and average maximum weight gain by

Eisenia fetida earthworm species was recorded at 5th week with PH 7.0, temperature 23

oc and and Moisture level of 80% and the number of earthworm increased from 300 to 520. The further incubation on T3 (

Eragrostis tef) at 84 days (12th week) and T1 (Pisum sativum residues) 122 days (17th week) resulted in weight loss indicated nutrient deficiency. The previous study by [

22] The study reported that

Eisenia fetida exhibited optimal growth after 6 weeks under conditions of pH 7.0, particle size of 1-2mm, a temperature of 25°C, and a moisture level of 70% to 80%, with biomass gains ranging from 175 to 3363 mg and a 1999% increase in biomass. The current study, however, identified a 5-week period as the optimal incubation time for

Eisenia fetida [

17] Reported weight loss on 7th and 8th week of incubation for

Eudrilus eugeniae which is similar to the present results.

Total Nitrogen

The data on the total nitrogen (TN %) content in vermicompost under various treatments are shown in

Table 2. In T1, the TN% rose from 0.981% to 2.557%. T2 saw an increase from 1.897% to 2.866%, while T3 went from 1.42% to 2.275%, with a difference of 0.855%. The highest TN% was observed in T2 (2.866%), followed by T1 (2.557%) and T3 (2.275%). The changes in nitrogen content were found to be significant.

Treatment T3 was found significantly less to the rest of the treatments. This result is reliable with some previous workers who reported increased levels of total nitrogen after adding leguminous crop residue, oil seed crop residue and cereal crop residue supplements, such as 0.98% leguminous crop residue was increased by 0.77% to 1.75% (IRJSS, 2014), 1.65% of oil seed crop residue increased to 1.92% [

10] and cereal crop residue was increased from 0.263% to 0.445% with the difference of 0.182% (ICS, 2017). The enhancement of TN in vermicompost was probably due to mineralization of the organic matter containing proteins and conversion of ammonium-nitrogen into nitrate [

12,

16].

Total Phosphorus

The highest percentage of total phosphorus (TP) content was observed in T3 (0.305%), likely due to the mineralization of phosphorus. During vermicomposting, earthworms facilitate the conversion of insoluble phosphorus into a soluble form with the help of phosphatases, an enzyme found in their gut. This process enhances phosphorus mineralization in organic matter as it passes through the earthworm’s digestive system. T3 was followed by T1 (0.194%) and T2 (0.150%), with all three treatments being statistically similar and significantly more effective than the other treatments [

15] It was also reported that total phosphorus levels were higher when garden waste was supplemented with cow dung and mushroom litter, due to the enhanced decomposition of the litter by microorganisms, fungi, and earthworms. A similar finding was reported by IRJSS (2014), where the phosphorus content of leguminous crop residue increased from 0.32% to 0.78%. Other studies have also shown comparable results [

10], TP of oil seed residue was increased from 0.42% to 0.75% after vermicomposting.

ICS (2017) reported that an increase in phosphorous content from 0.0419% to 0.065% in cereal crop residual after vermicomposting. Other researchers, including [

6,

7,

8], [

18] and [

26], have also highlighted phosphatase activity, mobilization of organic matter, and mineralization by microorganisms and earthworms as key factors influencing progressive changes in TP.

Total potassium (TK) content in vermicompost is associated with the mineralization of organic waste, the total loss of organic matter, and increased activity of earthworms and microorganisms [

2,

14]. The highest percentage of total K content was observed in T1 (4.404%), attributed to the potassium content of field pea residue (Pisum sativum), which increased by 3.159% after vermicomposting. This was followed by T3 at 1.494%, and the determination of TK content in vermicompost was 4.051%, showing an increase of 2.557%. The lowest percentage of total potassium occurred in T2 (1.163%), and in vermicompost, it was 1.845%, indicating an increase by 0.682%. All three treatments were found to be statistically comparable to each other and significantly better than each other. According to IRJSS (2014), the TK of leguminous crop residue was 0.40%, and vermicompost prepared from leguminous crop residue was 0.85%, with a 0.45% increase in TP content. The result of ICS (2017) showed that potassium percent in cereal crop residue was 0.136%, and TK in vermicompost prepared from cereal crop residue was 0.191%, in agreement with [

10], where the percent potassium of oilseed residue was 0.41%, and 0.92% of TK in vermicompost prepared from oilseed residue, indicating a 0.51% increase in potassium content.

Total sulfur (TS) in

P. sativum, G. abyssinica and

E. tef ranged from 0.67 to 2.81%, with the highest content observed in treatment T2 (2.81%), followed by T1 (2.2%) and T3 (0.67%). Treatments T1 and T3 were statistically at par with each other. However, treatment T3 (0.67%) had a significantly lower TS content compared to T1 and T2. In another study, the total sulfur content in different treatments ranged from 0.85 to 1.32% [

9].

The percent total organic carbon (TOC %) was determined, and the data are presented in

Table 1 and

Table 2. TOC% ranged from 25.8 to 40.30%, and the differences across the treatments were significant. The highest TOC (40.30%) was found in treatment T3, followed by T1 (37.70%) and T2 (25.8%), and all these treatments were statistically at par with each other. The variation in TOC% indicates that the addition of bulking material and other nutritional supplements has a substantial impact on vermicomposting. Respiration and assimilation activities of earthworms and microbes are associated with reductions in TOC during vermicomposting ([

18]; [

6,

7,

8]. High nutrient substrate adequacy means higher microbial and earthworm activity, resulting in greater carbon release and assimilation, leading to lower overall TOC. The TOC results were similar to [

13,

14] (2021) (35%) (42%), who studied vermicomposting of plant substrates? Plant-based substrates contain slowly degrading lignocellulosic material, and to overcome the slow degradation of cellulose-rich waste mixtures during vermicomposting, few authors recommend adding cow dung or microbial inoculants [

15].

Conclusion

The process of vermicomposting results in an increase in NPK content. In comparison to the residue, the field pea residue contained 0.976% nitrogen (N), 0.075% phosphorus (P), and 1.24% potassium (K). Vermicompost made solely from field pea residue had 2.557% N, 0.270% P, and 4.404% K. Similarly, the nutrient content of vermicompost prepared exclusively from noug residue was 2.866% N, 0.150% P, and 1.845% K, with an increase of 0.976% in N, 0.022% in P, and 0.685% in K. The vermicompost made from teff hay had 2.275% N, 0.304% P, and 4.05% K. In all cases, the nutrient content in the vermicompost was higher than that in the residue. This improvement is attributed to the enzymes, hormones, mucus, and body fluids present in the earthworm’s intestinal tract, which contribute to the enhancement of nutrients. Additionally, decaying body parts of the earthworm are expelled through the vermicast, further enriching the nutrient content.

Vermicompost is an easily accessible, cost-effective, and environmentally friendly source of plant nutrients. To maintain soil fertility and enhance agricultural productivity, it is recommended that farmers use vermicompost instead of commercial fertilizers. In urban areas, vermicomposting can be a practical solution for waste reduction, as it allows for the production of vermicompost from various organic wastes, whether from the community or households, using earthworms.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions of the study are provided in the article/Supplementary Material; any additional inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Authors’ contributions

The two authors made significant intellectual contributions to this manuscript. The researchers collected the data, conducted the analyses, and wrote the initial draft. Subsequently, the authors participated in critically revising the manuscript for important intellectual content. All authors reviewed and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Funding sources

Funding for data collection and laboratory analysis was covered by researcher themselves.

References

- Abrha Mulu (2015). Characterization of wastewater and evaluation of the effectiveness of the wastewater treatement systems in Luna and Kera slaughterhouses in Central Ethiopia, a Thesis in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science in Environmental Science, Addis Ababa University, Ethiopia.

- Anil Kumar CH, Bhanu Prakash, Navjot Singh Brar, Balwinder Kumar (2018). Potential of Vermicompost for sustainable crop production and soil health improvement in different cropping systems. International Journal of Current Microbiology and Applied Sciences ISSN: 2319-7706 Volume 7 Number 10.

- Aslam Z, Ahmad A, Bellitürk K, Iqbal N, Idrees M, Rehman WU, Akbar G, Tariq M, Raza M, Riasat S, Rehman SU (2020). Effects of vermicompost, vermi-tea and chemical fertilizer on morpho-physiological characteristics of tomato (Solanum lycopersicum) in Suleymanpasa District, Tekirdag of Turkey. Pure and Applied Biology 9(3): 1920-1931. [CrossRef]

- Aslam, F., Awan, T. M., Syed, J. H., Kashif, A., & Parveen, M. (2020). Sentiments and emotions evoked by news headlines of coronavirus disease (COVID-19) outbreak. Humanities and Social Sciences Communications, 7(1). [CrossRef]

- Aslam, Z. and Ahmad, A. (2020). Effects of vermicompost, vermi-tea and chemical fertilizer on morpho-physiological characteristics of maize (Zea mays L.) in Suleymanpasa District, Tekirdag of Turkey. Journal of Innovative Sciences, 6(1): 41-46. [CrossRef]

- Balachandar R, Biruntha M, Yuvaraj A, Thangaraj R, Subbaiya R, Govarthanan M and Karmegam N(2021). Earthworm intervened nutrient recovery and greener production of vermicompost from Ipomoea staphylina–An invasive weed with emerging environmental challenges. Chemosphere, 263, 128080. [CrossRef]

- Balachandar R, Biruntha M, Yuvaraj A, Thangaraj R, Subbaiya R, Govarthanan, M. and Karmegam N. (2021). Earthworm intervened nutrient recovery and greener production of vermicompost from Ipomoea staphylina–An invasive weed with emerging environmental challenges.Chemosphere263:128080. [CrossRef]

- Bellitürk, K., Aslam, Z., Ahmad, A. and Rehman, S.U. (2020). Alteration of physical and chemical properties of livestock manures by Eisenia fetida (Savigny, 1926) and developing valuable organic fertilizer. Journal of Innovative Sciences, 6(1): 47-53. [CrossRef]

- Bhargava A, Sharma SK and Trivedi SK (2023). Production and Composition of Nutrient Enriched Vermicompost Prepared from different Organic Materials and Minerals, Biological Forum – An International Journal, 15(2): 350-357.

- Bhor, S. D., Patil, S. R., Gajare, A. S., and Ghodke, S. K. (2013). Influence of crop residue and earthworm species on quality and decomposition rate of vermicompost. An Asian Journal of Soil Science, 8(1), 72-75.

- Celik A, Belliturk K, Sakin E (2020). Agriculture friendly bio fertilizers in waste management: vermicompost and biochar. New approaches and applications in agriculture. (Editor: Mehmet Firat Baran). Iksad Publications 2020© ISBN: 978-625-7279-66-6.

- Deepthi, K., and Jereesh, A. S. (2021). "Inferring potential CircRNA–disease associations via deep autoencoder-based classification." Molecular Diagnosis & Therapy 25 (2021): 87-97. [CrossRef]

- Devi C and Khwairakpam M (2021). Bioconversion of Lantana camara by vermicomposting with two different earthworm species in monoculture. Bioresour Technology 296, 122308.

- Devi, C. and Khwairakpam,M.(2020). Bioconversion of Lantana camara by vermicomposting with two different earthworm species in monoculture. Journal of bioresource technology, 296(2):122308. [CrossRef]

- Gong X, Li S, Carson M A, Chang SX, Wu Q, Wang L, An Z and Sun X (2019). Spent mushroom substrate and cattle manure amendments enhance the transformation of garden waste into vermicomposts using the earthworm Eisenia fetida. J Environ Manage, 248, 109263. [CrossRef]

- Jayakumar, M., Gindaba, G. T., Gebeyehu, K. B., Periyasamy, S., Jabesa, A., Baskar, G. & Pugazhendhi, A. (2023). Bioethanol production from agricultural residues as lignocellulosic biomass feedstock’s waste valorization approach: A comprehensive review. Science of The Total Environment, 879, 163158. [CrossRef]

- Kadam, D.G. and Pathade, G.R. (2004). Studies on vermicomposting of tendu leaf Diospyros melanoxylon Roxb. refuse with emphasis on microbiological and biochemical aspects. Ph.D. Thesis.

- Karmegam N, Vijayan P, Prakash M and Paul JA (2019). Vermicomposting of paper industry sludge with cow dung and green manure plants using Eisenia fetida: A viable option for cleaner and enriched vermicompost production. J Clean Prod., 228,718– 728. [CrossRef]

- Karmegam, N., Jayakumar, M., Govarthanan, M., Kumar, P., Ravindran, B., & Biruntha, M. (2021). Precomposting and green manure amendment for effective vermitransformation of hazardous coir industrial waste into enriched vermicompost. Bioresource Technology, 319, 124136. [CrossRef]

- Kilbacak H, Belliturk K, Çelik A (2021). From vegetable and animal wastes producing vermicompost: green almond shell and sheep fertilizer mixture example. Overview of Agriculture the Academic Perspective. (Editor: Gulsah Bengisu). Iksad Publications –2021© ISBN: 978-605-70345-3-3, pp. 19-44.

- Manaig Elena M (2016). Vermicomposting Efficiency and Quality of Vermicompost with Different Bedding Materials and Worm Food Sources as Substrate. Research Journal of Agriculture and Forestry Sciences, Vol. 4(1), 1-13.

- Mulla A. I. and Pathade G.R. (2000). Optimization of Incubation Period, pH and Moisture Content for Vermicomposting of Biomethanation Sludge Admixed with Fruits and Vegetable Waste Collected from Gultekadi Market Yard, Pune Using Eudrilus eugeniae. Journal of Nature Environment and Pollution Technology, Vol. 19, No. 2, 873- 880. [CrossRef]

- Ramnarain, Y. I., Ansari, A. A., and Ori, L. (2019). Vermicomposting of different organic materials using the epigeic earthworm Eisenia foetida. International Journal of Recycling of Organic Waste in Agriculture, 8, 23-36. [CrossRef]

- Rehman, T., Shabbir, M.A., Inam-Ur-Raheem, M. (2020). Cysteine and Homocysteine as Biomarker of Various Diseases. Food Science & Nutrition, 8, 4696-4707. [CrossRef]

- Rogue, P. (2017). The History of Vermicomposting. https://www.gardenguides.com/121248-history-vermicomposting.html.

- Yadav J, Gupta RK, (2017).Dynamics of nutrient profile during vermicomposting. Ecology, Environment and Conservation. 23(1):445-450.

- Yuvaraj, A., Thangaraj, R., Ravindran, B., Chang, S. W., and Karmegam, N. (2021). Centrality of cattle solid wastes in vermicomposting technology–A cleaner resource recovery and biowaste recycling option for agricultural and environmental sustainability. Environmental Pollution, 268, 115688. [CrossRef]

- Zhang BG, Li GT, Shen TS, Wang JK, Sun Z (2000). Changes in microbial biomass C, N, and P and enzyme activities in soil incubated with the earthworms Metaphire guillelmi or Eisenia fetida. Soil Biol Biochem. 32: 2055–2062. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H., & Forde, B. G. (2000). Regulation of Arabidopsis root development by nitrate availability. Journal of experimental botany, 51-59.

- EMA (2016). Ethiopia Metrology Agency. Climatic data of monthly mean rainfall, minimum and maximum temperature. Bedele District.

- FAO (1998). Lowland plains of Dhidhessa Valley Pellic Vertisols is the dominant soil type.

- IRJSS, (2014). Crop residues management and nutritional improvement practices.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).