Introduction

Healthcare services in hospitals involve not only healthcare professionals but also the contributions of patient companions, who play a vital role in various aspects of patient care [

1]. A companion or family caregiver is defined as any family member, friend, or volunteer who is available to assist a hospitalized patient [

2]. Numerous health studies have documented the responsibilities that patient companions perform in healthcare facilities. Thus, these family caregivers provide cleaning care, psychological, physical, educational support and often deliver nursing care at the bedside [

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8]. This broad array of care activities contributes to patient well-being and recovery. However, these activities may also expose patients and/or their companions to the risk of healthcare-associated infections (HAIs) [

4].

In addition, the involvement of patient companions into the care process has been demonstrated to alleviate the workload of healthcare personnel by increasing the services provided, particularly in contexts characterized by shortages of qualified human resources and constrained healthcare funding [

1,

6]. The African continent is disproportionately impacted by the global shortage of healthcare professionals, as evidenced by its 24% share of the global disease burden despite its 3% contribution to the global healthcare workforce and its allocation of less than 1% of global health expenditures [

9,

10].

As is the case in other African countries, the health sector in Burkina Faso is grappling with a dearth of qualified human resources. As a result, nursing assistants frequently assume the role of caregivers, while patient companions function as health assistants or, on occasion, as caregivers [

11]. On the other hand, the patients that family caregivers assist are most often carriers of contagious infectious diseases of which they are totally unaware, which exposes them to real infectious risks [

11]. Thus, without proper infection prevention and control (IPC) training, these companions may serve as reservoirs and transmitters of infections during care processes [

12]. This could have adverse health consequences, both for them and for patients and the community [

4,

13].

Nevertheless, the safety of patient companions’ care in our context has yet to be substantiated by robust evidence. The objective of this study is to examine the knowledge and practices of IPC among patients’ companions in care settings in three referral health centers in the city of Bobo-Dioulasso, Burkina Faso. The identification of the determinants and risks associated with their activities is a key step in developing effective support systems for patient companions.

Methodology

Study Design and Setting

This multicenter cross-sectional analytic study was conducted from May 1 to November 30, 2022, in three public health facilities in Bobo Dioulasso, Burkina Faso’s second largest city. The facilities included the Sourô Sanou University Hospital (CHUSS) and the two district hospitals of Do (Do/DH) and Dafra (Dafra/DH). The CHUSS is a third-level health facility that receives the majority (98%) of patients from four health regions of the country (Hauts-Bassins, Boucle du Mouhoun, Cascades, and Sud-Ouest). The district hospitals constitute the second rung of the first-level healthcare system, serving as referral centers for patients from these primary health centers within their respective catchment areas. Participants in the CHUSS were recruited from the intensive care, pediatric, and post-operative gynecology and obstetrics wards. In contrast, the Do and Dafra district hospitals recruited participants from the post-operative wards.

Study Population

The study population consisted of companions present at their patient’s bedside when the interviewers visited the target services and agreed to participate in the survey. Visitors were not included in this study.

Sampling

Sampling Type

We used non-probability sampling consisting of consecutively including no more than two companions per patient, present in the care units of the three hospital structures at the time of the surveys.

Sample Size

Our sample size was calculated by the following formula:

πy: proportion of companions with good IPC practice in hospitals estimated at 50 percent. In the absence of baseline data, we chose the proportion that maximizes the sample size.

uα: value associated with the degree of confidence in the information, with u5% = 1.96.

E: Accuracy = 5%.

Thus, a minimum number of 384 patient companions was required for this study. We included 789 participants in this study.

Variables

Dependent variables

The dependent variables in this study were the levels of IPC knowledge and practices. Respondents were grouped according to their responses to the “correct answer” and “wrong answer” questions, as well as according to their “good practice” and “bad practice” practices. The knowledge and practices of the patient companions were then transformed into a quantitative score. To quantify the knowledge and practice scores of the patient companions, the knowledge and practice questions were coded by assigning a point when the response to a question or practice was adequate and zero points when appropriate. For each domain, a score was calculated by summing the points. For each individual, the knowledge and practice scores were reported at the maximum score and then multiplied by 100 to obtain a score out of 100.

-

Explanatory variables

- -

Age in years: convenience-based grouping of participants into five age groups was employed: ≤25, 26-35, 36-45, 46-55, >55.

- -

Gender: male and female.

- -

Occupation: occupations were grouped into six categories: housewife, trader, farmer, pupil/student, civil servant, other.

- -

Location: Rural, urban

- -

Marital status: Married, widowed and single.

- -

Education: None, primary, secondary and above

- -

Accompaniment experience: No, yes

- -

IPC awareness in health care settings: No, yes, missing data (MD)

- -

Healthcare facility: Sourô Sanou university hospital (CHUSS), Do district hospital (Do/DH), Dafra district hospital (Dafra/DH)

Statistical Analysis

The data obtained from the survey forms were entered into the Epidata3.1® software and subsequently analyzed with the Stata13® software.The socio-demographic characteristics, roles, and levels of IPC knowledge and practice of care companions were described for each care setting. The qualitative variables were presented as percentages, and the quantitative variables were expressed as mean and standard deviations (SD).The IPC knowledge and practice levels (proportion of correct responses, mean scores) among companions from the three facilities were then compared. The Kruskal-Walli’s test was used to compare quantitative variables and the Chi2 test to compare qualitative variables across facilities.

To determine the associations between knowledge and practice scores and participant sociodemographic characteristics, a multilevel linear regression model was constructed. The independent variables included participant age, sex, occupation, place of residence, marital status, level of education, accompaniment experience, IPC awareness in healthcare settings, and health setting. The significance level (p-value) was set at 5% for all statistical analyses.

Ethical Aspects

This study was conducted as part of a larger research initiative entitled “Strategies for the Surveillance and Prevention of Healthcare-Associated Infections in Bobo-Dioulasso, Burkina Faso.” The National Ethics Committee of Burkina Faso approved this study (reference letter of approval number 2022-02-020). Informed consent was obtained from all participants, and an information sheet was provided to each participant. To ensure confidentiality, the data collected was anonymized.

Results

Population Description

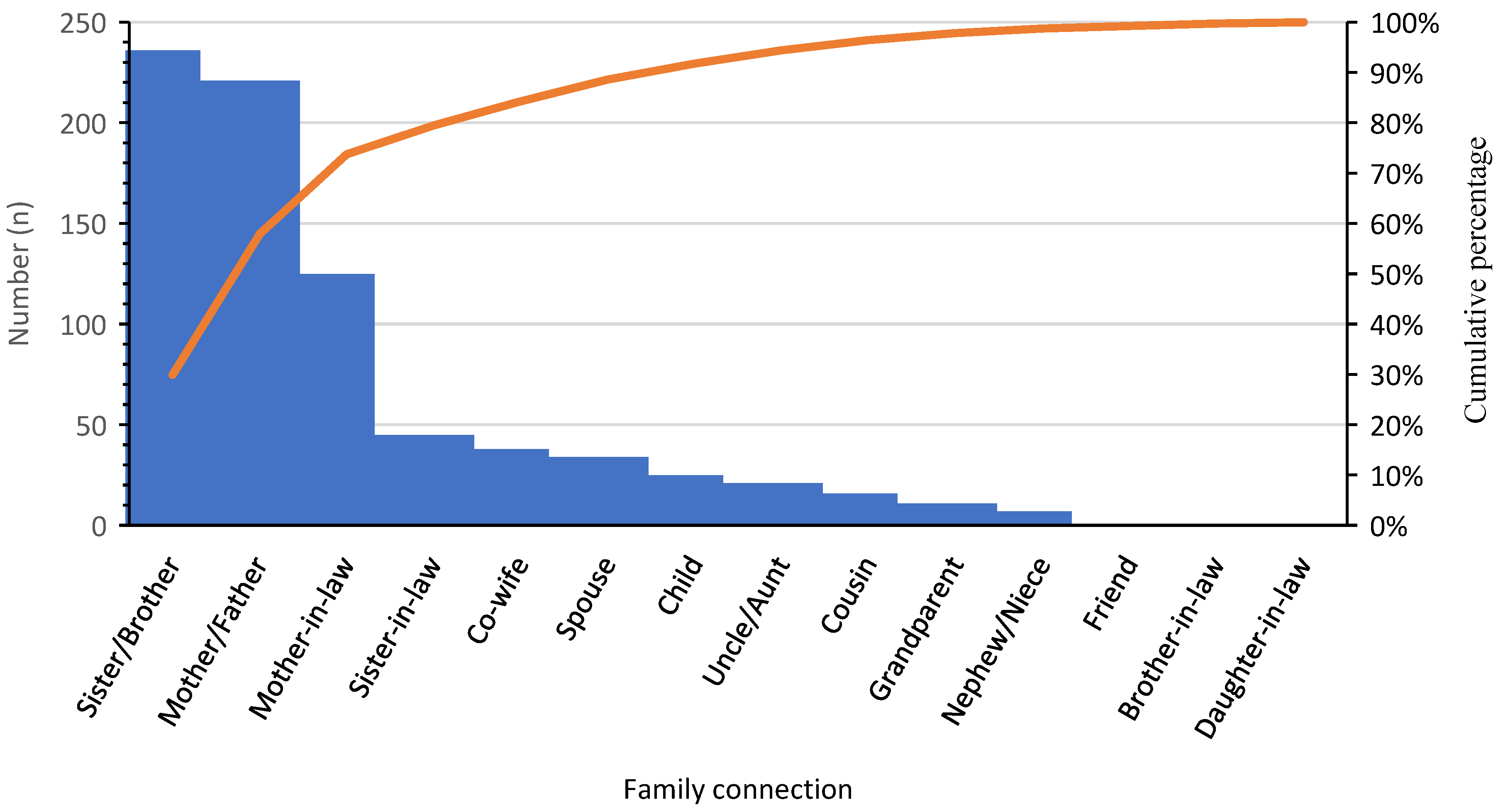

A total of 789 patient companions participated in this study, including 305 (38.7%) at the CHUSS, 244 (30.9%) at the Do/DH, and 240 (30.4%) at the Dafra/DH. The majority of companions were female (87.1%), resided in rural areas (84.3%), and were predominantly non-urban residents. The average age of the participants was 37.9 years (SD: 10.3), and 30.3% of them had received at least a primary education. Nearly the participants were married (94.3%), and 77.3% of them were housewives. Furthermore, more than half of the participants (51.7%) had experience as patient companion, with an average of 3.0 accompaniments (SD: 2.4) carried out. The average time spent by each companion at the patient’s bedside was 16.4 hours (SD:5.3) over the course of the patient’s stay. Furthermore, 78.8% of companions reported that they had not received IPC awareness in the healthcare setting. The average number of companions per patient was 3.0 (SD: 1.3), with extremes ranging from 1 to 12. In the majority of cases, these companions were patients’ family members, with 80% assisting a sister, brother, mother, father, mother-in-law, or sister-in-law (

Figure 1). The differences in the distribution of patients’ companions between the three hospitals was found to be statistically significant across various sociodemographic factors, including age, sex, place of residence, education, marital status, occupation, experience in companionship, and awareness (see

Table 1 for details).

Roles of Patient Companions

Patient companions played an instrumental role in supporting hospitalized individuals, with nearly all of them (more than 98%) actively involved in patient care, providing both nursing and basic care. Their responsibilities included monitoring the patient, overseeing or discontinuing infusions, administering medications orally or subcutaneously, assisting with washing, dressing, feeding, making the bed, helping with mobility, and managing excreta removal. Beyond the immediate patient care realm, a significant proportion of companions (greater than 93%) engaged in providing psychological support, while an analogous proportion (93.9%) undertook housekeeping responsibilities, encompassing tasks such as dishwashing, cleaning the hospital environment, and waste management. In addition, a substantial majority of companions (more than 80%) actively participated in therapeutic decision-making processes concerning their patients, in addition to undertaking various administrative and logistical tasks. These tasks included the collection of medical test results, the procurement of medications, and the accompaniment of patients to external medical examinations. However, the involvement of patient companions in the various patient support processes appears to be more pronounced in district hospitals than at CHUSS, as illustrated in

Table 2.

Patient Companions’ Knowledge of IPC in Healthcare Settings

Patient companions correctly answered an average of 39.7% of the questions assessing their knowledge of IPC in healthcare. The study revealed that 46 participants (5.8%) were aware of potential infection transmission sources in healthcare settings, with no participants from Dafra demonstrating such awareness (p=0.000). Furthermore, 88.3% of the companions were unaware that meals could be a source of transmission of infection. Regarding exposure to healthcare-associated infections, 141 participants (17.9%), including 127 from CHUSS, were able to identify individuals at risk. However, 44.9% of companions did not recognize that hospital visitors could also be exposed to infections. Knowledge about hand hygiene was particularly low, only 58 companions (7.3%), including 42 from CHUSS, were aware of the key moments for hand hygiene (p = 0.000). Moreover, a significant proportion, 79% of the participants, lacked awareness of the imperative for hand hygiene prior to patient contact. The overall average IPC knowledge score among patient companions was 32 out of 100 (SD: 16.3). Scores were significantly higher at CHUSS compared to Do/DH and Dafra/DH (p = 0.000), as illustrated in

Table 3

Patient Companions’ Practices of IPC in Health Care Settings

Among the patient companions surveyed, only 15.8% adequately managed patients’ linens, with notable differences across facilities: 27.9% at CHUSS, 16.4% at Do/DH, and 0% at Dafra/DH. Additionally, only 16.1% of companions decontaminated soiled laundry before washing. The majority of companions effectively managed patient excreta (92.8%) and food leftovers (87.7%). However, only 41.9% of those patient companions appropriately disposed of empty packaging. CHUSS participants exhibited notably superior waste management practices compared to those at Do/DH and Dafra/DH. The mean hygiene practice score among patient companions was 81.0 out of 100 (SD: 16.2). This score was significantly higher among CHUSS participants (84.9 out of 100) compared to those at Do and Dafra (p = 0.000), as illustrated in

Table 3.

Factors Associated with IPC Knowledge and Practices of Patient Companions in Healthcare Facilities

Factors associated with higher levels of IPC knowledge in healthcare settings among patient companions, included male gender, urban residence, widowed status, secondary and above education level, and previous IPC awareness. Similarly, secondary and above education level and previous IPC awareness were associated with better IPC practices in healthcare settings among patient companions. Conversely, being a patient companion in Dafra/DH was associated with lower IPC practice scores compared to other facilities (

Table 4).

Discussion

This study aimed to assess the knowledge and practices of IPC among patient companions in the three referral health centers of Bobo-Dioulasso. A total of 789 companions participated, most of whom were young women with low levels of education and family ties to the patients. The findings revealed a low level of IPC knowledge but a relatively high level of IPC practice in healthcare settings. Factors associated with better IPC knowledge included male gender, urban residence, widowed status, high school education or higher, and previous IPC awareness. Similarly, secondary education, prior awareness, and being at CHUSS or Do/DH were associated with better IPC practices in healthcare settings.

The present study demonstrated that patient companions played a critical role in providing essential care activities, including patient monitoring, medication administration, and toileting. The involvement of patient companions in the care process has been documented in numerous studies, including those by Surendran et al. in India [

14], Prokop et al. in Germany [

6], Sterponi et al. in Italy [

5], Koshkeshtb et al. in Iran [

15], Aniceto et al. in Brazil [

2], and Akpinar et al. in Turkey [

7]. Beyond the provision of direct care, patient companions have been shown to provide emotional, educational, informational, and physical support to patients [

5,

6,

7,

8]. Their presence has also been demonstrated to facilitate communication between patients and healthcare providers, which may improve patient safety and reduce the risk of adverse treatment effects [

16,

17,

18].

This study found that the average number of companions per patient was three, with a range of one to 12. The presence of multiple companions in the patient’s care environment can result in inadequate patient supervision and contribute to hospital overcrowding, as previously reported by Surendran et al. in India [

14]. This situation increases the risk of pathogen transmission between patients and their companions, as well as exposure to hospital-acquired infections. The risk is further exacerbated when companions possess limited knowledge of infection control or fail to adhere to IPC measures in healthcare settings.

The present study revealed that IPC companions exhibited a deficiency in knowledge, particularly concerning hand hygiene and the sources of infection transmission. These elements are crucial for ensuring the safety of patients, companions, and caregivers [

19,

20]. This finding stands in contrast to the higher practices observed. A similar observation was made in a study by Zahradnik et al. [

21] that examined hand hygiene among family caregivers in Canada. The study reported a high level of self-reported knowledge but a low level of actual practice (9%). The observed discrepancy between knowledge and practice may be attributed to the fact that knowledge is closely linked to education level, whereas practice is more influenced by behavior and cultural norms. Consistent with the findings of this study, Park et al. [

4] reported in a multicenter study conducted in Bangladesh, Indonesia, and South Korea that family caregivers had insufficient knowledge of infection prevention and control measures for healthcare-associated infections (HAIs).

The dearth of knowledge evident in this study may be attributed to the limited educational attainment of the participants. The knowledge and practices of patient companions pertaining to IPC frequently remain unacknowledged, thereby engendering potential hazards to caregivers, patients, and the healthcare milieu.The WHO advocates for the integration of family members into the execution of the multimodal IPC strategy, acknowledging their pervasive involvement in patient care within certain facilities [

22].Nevertheless, the majority of WHO guidelines predominantly focus on healthcare professionals, with IPC promotion endeavors seldom addressing patient companions. Consequently, there is a prevalent misperception among families that they should play a passive role in infection prevention and control [

4,

22].

The findings of this study indicated that education level and prior awareness were the key factors associated with better IPC knowledge and practices among patient companions. This result is consistent with those of Allegranzi et al. [

23], which showed that access to educational resources or communication materials adapted to the level of understanding (language, health literature, etc.) were associated with better IPC knowledge and practice. Furthermore, Helman et al. [

24] and Abiétar et al. [

17] noted the impact of cultural factors, traditional practices, and local beliefs on IPC behaviors. Awareness-raising activities and educational materials (e.g., posters, brochures) on the modes of transmission of infectious agents, hand hygiene, environmental hygiene, and wearing of personal protective equipment in healthcare settings could improve the participation of companions in IPC [

25]. These initiatives must be meticulously designed with consideration for cultural specificities, education levels, and literacy skills to ensure effective participation.

The primary limitation of this study is its failure to address the contextual, organizational, and structural factors that hinder the implementation of IPC by patient companions. Additionally, it does not take into account companions’ perceptions of patient safety. Notwithstanding these limitations, this study offers significant insights by being the first in our context to assess the level of IPC knowledge and practices among patient companions, as well as the factors influencing them, within a large study population.

Conclusion

The results of this study highlight the critical role of patient companions in the care process. However, their IPC knowledge and practice levels remain low, with lack of education and awareness being the primary contributing factors. To address this gap, these initiatives must prioritize standard precautions, encompassing hand hygiene, environmental hygiene, and the proper use of personal protective equipment. Additionally, providing companions with access to essential resources will facilitate the enhancement of their IPC knowledge and practices, thereby contributing to an improvement in patient and healthcare safety.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org. Table S1: Database. Figure S2: Distribution of Average IPC knowledge and practice scores for Patient companions

Author Contributions

AH, SAS, OK and SS designed the study; AH, SAS, SS and OK drafted the manuscript. AH, SAS and OK conducted the analyses. AH, SAS, SS, OK, AP, ZCM, ASO and LS contributed to the interpretation of the findings and edited and reviewed the manuscript. All the authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

No external funding was provided for this project. The costs of collecting data were borne by a group of researchers from Sourô Sanou Teaching Hospital and Centre Muraz.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was approved by the National Health Ethics Committee of Burkina Faso reference letter of approval number 2022-02-020). An information sheet was given to each participant. After reading this information sheet, those who desired to participate in the study signed a free and informed consent form. The data collected were anonymized to ensure their confidentiality.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets, including deidentified quantitative and qualitative data, used and/or analyzed during the current study are available in the

Supplementary Materials.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the data collectors, the staff of Sourô Sanou Teaching Hospital, Do and Dafra District Hospitals. We would also like to thank the patient companions for their participation in this study.

Conflicts of Interest

AH, SAS, OK, SS, AP, ZCM, ASO and LS have no competing interests to declare.

References

- Casey V, Crooks VA, Snyder J, et al. Knowledge brokers, companions, and navigators: a qualitative examination of informal caregivers’ roles in medical tourism. Int J Equity Health 2013; 12: 94.

- Aniceto SC, Loureiro LH. Hospitalization: the companion at the center of research. Res Soc Dev 2020 ; 9 : e201985618.

- Islam MS, Luby SP, Sultana R, et al. Family caregivers in public tertiary care hospitals in Bangladesh: Risks and opportunities for infection control. Am J Infect Control 2014; 42: 305–310.

- Park JY, Pardosi JF, Seale H. Examining the inclusion of patients and their family members in infection prevention and control policies and guidelines across Bangladesh, Indonesia, and South Korea. Am J Infect Control 2020; 48: 599–608.

- Sterponi L, Fatigante M, Zucchermaglio C, et al. Companions in immigrant oncology visits: Uncovering social dynamics through the lens of Goffman’s footing and Conversation Analysis. SSM - Qual Res Health 2024; 5: 100432.

- Prokop A, Reinauer K-M, Koebler M, et al. Do we need more volunteering in medicine? Examples of traumatic surgery projects. Z for Orthop Trauma Surgery 2023; 161: 366–369.

- Akpinar A, Özcan M, Ülker Toygar D. Patient’s companions as a vulnerable group in Turkish hospitals: A descriptive study. J Eval Clin Pract 2020 ; 26 : 1196–1204.

- Pomey M-P, Paquette J, Iliescu-Nelea M, et al. Accompanying patients in clinical oncology teams: Reported activities and perceived effects. Health Expect Int J Public Particip Health Care Health Policy 2023; 26: 847–857.

- International Finance Corporation (IFC). Investing in Health in Africa - The Private Sector: A Partner in Improving People’s Lives https://documents.banquemondiale.org/fr/publication/documents/reports/documentdetail/302121467990315371.

- World Health Organization. Commitment to Health and Growth: Investing in the Health Workforce, https://www.who.int/fr/publications/i/item/9789241511308 (2016, accessed 25 February 2025).

- Ouedraogo SM, Sondo KA, Kyelem CG, et al. Roles and tasks of inpatient companions in the pneumophthysiology department at Yalgado Ouedraogo University Hospital of Ouagadougou (Burkina Faso). Sci Tech Sci Santé 2014; 37: 57–66.

- Blancarte-Fuentes E, Álvarez-Aguirre A, Tolentino-Ferrel MDR. Primary caregiver as transmission agent of health care-associated infections: literature review. SANUS IS A 2020; 34–50.

- Lee H, Singh J. Appraisals, Burnout and Outcomes in Informal Caregiving. Asian Nurs Res 2010; 4: 32–44.

- Surendran S, Castro-Sánchez E, Nampoothiri V, et al. Indispensable yet invisible: A qualitative study of the roles of carers in infection prevention in a South Indian hospital. Int J Infect Dis IJID Off Publ Int Soc Infect Dis 2022; 123: 84–91.

- Khoshkesht S, Ghiyasvandian S, Esmaeili M, et al. The Role of the Patients’ Companion in the Transitional Care from the Open-Heart Surgery ICU to the Cardiac Surgery Ward: A Qualitative Content Analysis. Int J Community Based Nurs Midwifery 2021; 9: 117–126.

- Miller AD, Mishra SR, Kendall L, et al. Partners in Care: Design Considerations for Caregivers and Patients During a Hospital Stay. In: Proceedings of the 19th ACM Conference on Computer-Supported Cooperative Work & Social Computing. San Francisco California USA: ACM, pp. 756–769.

- Abiétar DG, Domingo L, Medina-Perucha L, et al. A qualitative exploration of patient safety in a hospital setting in Spain: Policy and practice recommendations on patients’ and companions’ participation. Health Expect Int J Public Particip Health Care Health Policy 2023; 26: 1536–1550.

- Oliveira TGPD, Diniz CG, Carvalho MPM, et al. Involvement of companions in patient safety in pediatric and neonatal units: scope review. Rev Bras Enferm 2022; 75: e20210504.

- World Health Organization, WHO Patient Safety. WHO guidelines on hand hygiene in health care. 2009; 262.

- World Health Organization. Improving infection prevention and control at the health facility: Interim practical manual supporting implementation of the WHO Guidelines on Core Components of Infection Prevention and Control Programmes. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2018 (WHO/HIS/SDS/2018.10).

- Zahradnik S, Tsampalieros A, Okeny-Owere J, et al. Hand hygiene knowledge and practices of family caregivers in inpatient pediatrics. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2024; 45: 253–256.

- World Health Organization. Guidance on key components of infection prevention and control programs at the national and acute care level. Geneva: World Health Organization, https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/272850 (2017, accessed 13 February 2025).

- Allegranzi B, Pittet D. Role of hand hygiene in healthcare-associated infection prevention. J Hosp Infect 2009; 73: 305–315.

- Helman C. Culture, Health and Illness, Fifth edition. 0 ed. CRC Press. Epub ahead of print 26 January 2007. [CrossRef]

- Siegel JD, Rhinehart E, Jackson M, et al. 2007 Guideline for Isolation Precautions: Preventing Transmission of Infectious Agents in Health Care Settings. Am J Infect Control 2007; 35: S65–S164.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).