1. Key Findings

High antibiotic use with partial adherence to medical advice: Over half (56.2%) of participants reported using antibiotics in the past year, with a large portion following prescriptions. However, many stopped antibiotics early, indicating limited adherence to completing prescribed courses.

Significant misconceptions about antibiotic use: A substantial number of participants incorrectly believed antibiotics could treat viral illnesses like colds and flu, with only 35% aware of the importance of completing the full course. Misunderstandings also extended to using non-prescribed antibiotics from family or friends, which increases the risk of resistance.

Educational level strongly correlates with knowledge of antibiotic use and amr: Higher education levels correlated significantly with better knowledge about antibiotics and AMR. Participants with college or university education were more likely to understand the appropriate use of antibiotics and the risks of AMR, highlighting an education-driven disparity in health literacy.

Urgent need for targeted educational interventions: The findings emphasizes the necessity of targeted educational efforts to address misconceptions about antibiotic use, especially among those with lower educational levels. Public health campaigns could play a crucial role in promoting appropriate antibiotic use and reducing AMR in Sri Lanka.

2. Introduction

Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) is a major global health threat that undermines effective infection treatment leading to prolong hospital stays, high costs, and higher mortality rates [

1,

2]. AMR escalates with improper antibiotic use, especially in community settings [

3]. Limited public awareness about when and why antibiotics should be used, and their restriction per WHO guidelines, fuels misuse [

3,

4], Factors such as self-medication, poor adherence to prescriptions, over-the-counter antibiotic sales, and reliance on unofficial healthcare sources all contribute to antibiotic misuse [

4,

5].

Reducing AMR starts by limiting antibiotic use [

5]. Antimicrobial stewardship programs (ASPs) are coordinated efforts to optimize antimicrobial use, enhancing patient outcomes, reducing resistance, and limiting multidrug-resistant infections [

6]. ASPs have proven effective in lowering antibiotic use, minimizing adverse events, and improving outcomes, with a focus on public education about proper antibiotic use [

7,

8].

Health authorities should enhance ASP educational efforts to boost public knowledge on appropriate antibiotic use. Strengthened health promotion and guidance have been shown to improve adherence and awareness about AMR risks [

9]. Antimicrobial stewards, as healthcare professionals involved in ASPs, play a key role in this public education to address AMR effectively [

10]. Optimal antibiotic knowledge and awareness among the public is important to overcome the AMR challenge.

In Sri Lanka, the misuse and overuse of antibiotics are significant public health concerns, contributing to the growing problem of AMR [

11]. Although antibiotics are legally prescription-only, their over-the-counter availability in private pharmacies often promotes self-medication, improper dosing, and incomplete treatments, fueling the development of resistant pathogens. WHO highlights AMR as critical in Sri Lanka, with resistant infections rising in hospitals and communities [

12,

13]. Similarly, misconceptions and limited public knowledge about proper antibiotic use and AMR are common, along with high self-medication rates [

14,

15]. Despite government efforts to regulate antibiotic use, enforcement remains challenging, underscoring the need for stronger stewardship initiatives and public awareness campaigns to address AMR [

13].

This study aims to evaluate public knowledge, practices, and misconceptions about antibiotic use and AMR among Sri Lankans, examining variations across demographics, especially education levels. It seeks to identify gaps to inform targeted health interventions, education, and stewardship efforts.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Study Design and Setting.

This descriptive cross-sectional study used a self-administered questionnaire to explore antibiotic usage, knowledge of treatment indications, and AMR among the general public who visited four hospitals in Sri Lanka (as patients, caregivers, friends, relatives, etc.). The hospitals were from three different geographical regions and consisted of three teaching hospitals and one base hospital. Ethical approval was obtained from the Ethics Review Committee of Faculty of Allied Health Sciences, University of Peradeniya (Ref: AHS/ERC/2020/026; 30th November 2020). Administrative approval from the Directors of the four selected Sri Lankan hospitals were obtained. This research was undertaken as part of MPhil study in October 2022-February 2023.

3.2. Recruitment and Sample Size

A convenience sampling technique was used to recruit participants for the survey. The sample size for this study was calculated based on the number of patients attending these hospitals. We assumed the response distribution to be 50% and determined the confidence interval at 95%, with a margin of error 5%. By using the Raosoft® sample size calculator the sample size was calculated. The minimum effective sample size estimated was 1520 in which 400 participants (26.3%) were recruited from Teaching Hospital One (TH1), 380 participants (25%) from Base Hospital One (BH1), 365 participants (24%) from TH2, and 375 participants (24.7%) from TH3. Participants were eligible if they were 18 years of age or older, able to read, write, and communicate in Sinhala or Tamil languages, and provided consent to participate.

3.3. Survey Administration and Data Collection Procedure

The participants were approached by one of two researchers, working at the four hospitals in the outpatient departments, medical and surgical wards until the target sample number had been achieved. The study was explained by the researcher to potential patients (emphasizing their voluntary participation and confidentiality of responses), and then informed consent was obtained.

To maintain confidentiality, all data were securely stored in locked cupboards or drawers at the University. Additionally, personal computers used for data storage were password-protected, further ensuring data privacy and security. No incentives for participation were offered. Surveys were self-completed in hard-copy and took around 20 minutes to complete.

3.4. Data Collection Tool

The study used a questionnaire based on the WHO Antibiotic Resistance, Multi-country Public Awareness Survey [

2], chosen for its prior international use and comprehensive coverage of antibiotic use, indications, and AMR. Permission to reproduce the survey was obtained (WHO Ref: 314741).

The questionnaire was piloted with 10 Tamil and 10 Sinhala participants at TH1 to assess design, relevance, readability, and flow. It was available in English, Sinhala, and Tamil—the main languages in Sri Lanka. The English version [

2] was translated and back-translated by the University of Jaffna, with the original authors reviewing for semantic accuracy. The questionnaire had five sections: (i) demographics (age, gender, marital status, residence, education), (ii) antibiotic use (recent use, source, advice), (iii) knowledge of antibiotic treatment (course and indications), and (iv) knowledge of antibiotic resistance. Internal consistency was validated using Cronbach’s alpha, with a criterion of 0.7 or above for acceptance.

3.5. Data Analysis

Data were coded and analyzed in SPSS (v22.0) using descriptive statistics (frequencies, percentages) and chi-squared tests to examine associations between knowledge level and education with p<0.05 set for significance. To identify the association between participants' knowledge of antibiotics and antimicrobial resistance with socio-demographic characteristics, a knowledge score was calculated based on the percentage of correct responses in the questionnaire. Knowledge scores were categorized as low (0-40%), moderate (41-70%), and high (81-100%) based on correct responses.

4. Results

4.1. Sociodemographic Characteristics of Study Participants

Table 1 outlines the participants’ characteristics; the majority was less than 45 years old (84.4%), more than half were female (57.5%), lived in rural areas (56.1%), and slightly less than half had completed secondary education (48.6%).

4.2. Self-Reported Antibiotic Use

Overall, 855 (56.25%) of participants reported using one or more antibiotics in the last year; 177 participants (11.0036%) had never taken antibiotics, and 488 participants (32%) had not used an antibiotic in more than a year or couldn't remember taking an antibiotic. Of those who reported use in the last 12 months, 23% (n = 350)) reported antibiotic use within the last month, 20.1% (n = 305) within the last six months, and 13.2% (n = 200) sometime in the last year.

4.3. Pattern of Antibiotic Use

The majority (52.6%) of this group had an antibiotic prescribed by a doctor, and 46.7% reported receiving advice from a healthcare professional when acquiring the antibiotic(s). The majority of participants (58.4%) got their antibiotics from hospital or community pharmacies. A quarter (n = 175/855;20.4%) reported obtaining antibiotics from family members or using saved antibiotics from a previous supply. Very few (1.5%) obtained antibiotic(s) on the internet. More than half (58.4%) said they should stop taking antibiotics once they felt better, while only35.0% thought they should continue taking antibiotics until the entire course was finished.

4.4. Knowledge of Antibiotic Use and Therapeutic Effectiveness

Less than half of the respondents (41.1%) reported that they should not use antibiotics prescribed for other people (e.g., friends or relatives) however, 39.9% thought that this behavior was acceptable. When asked, if it was appropriate to buy or ask a doctor to prescribe an antibiotic that had resolved their previous symptoms, 41% responded that this was not appropriate but 39.1% reported it was appropriate.

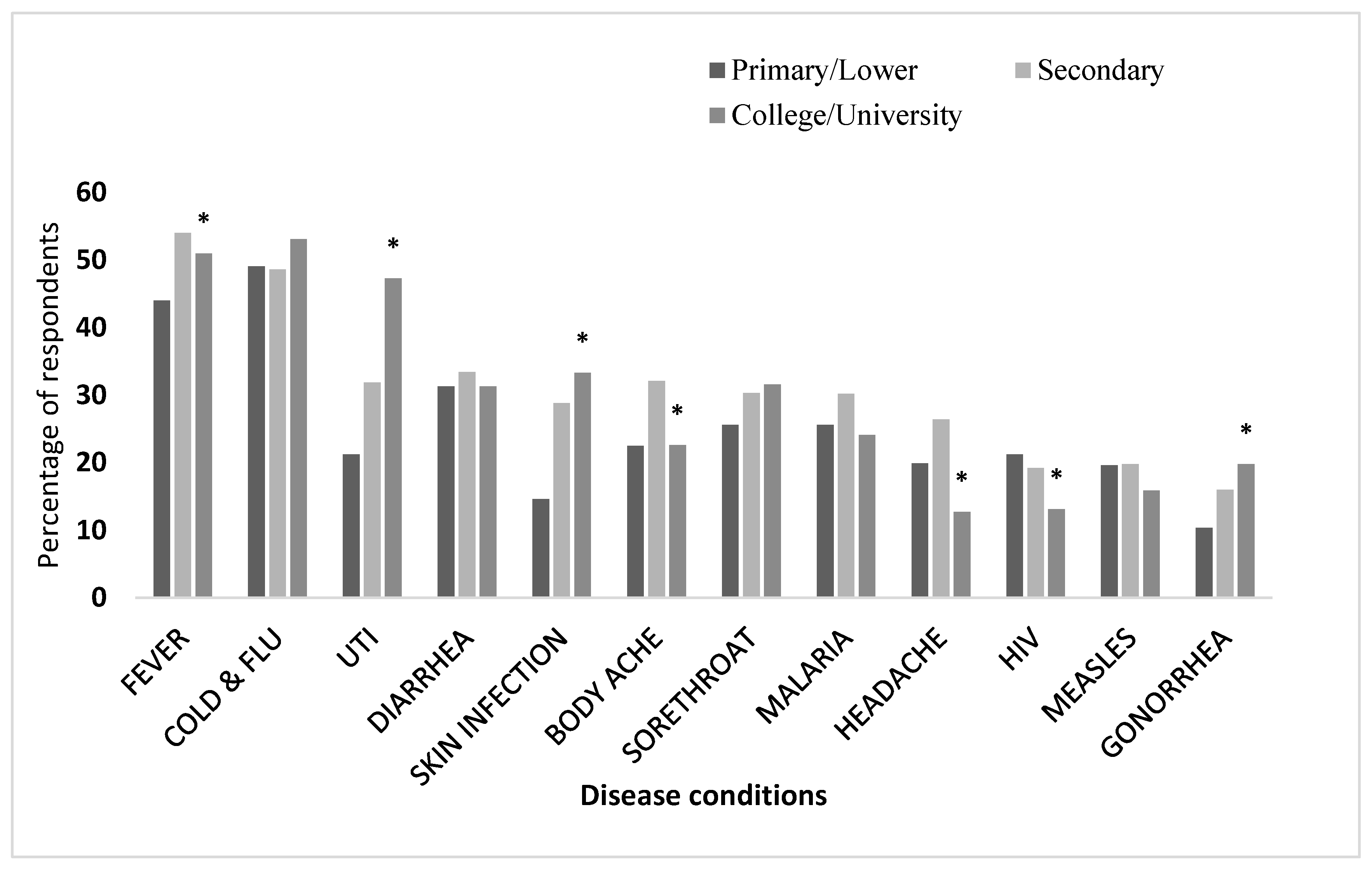

Respondents were asked to identify whether antibiotics were appropriate for the treatment of specific health conditions. Less than 35% of participants correctly identified effectiveness in these conditions: skin infections (27.2%), urinary tract infections (UTIs) (34.4%), gonorrhea (16%), malaria (27.4%), sore throats (29.7%), and diarrhea (32.4%). Additionally, a large number of participants incorrectly indicated that antibiotics were for colds and flu (50.1%) and fever (51.2%). Similarly, participants incorrectly reported that antibiotics were effective for body aches (27.2%) and headaches (20.9%).

Significant differences were found in knowledge about the effectiveness of antibiotics in specific health conditions according to participants' education status. Those who had attended college/university exhibited a higher level of antibiotic knowledge across a range of conditions (

Figure 1). For example: 47.3% of respondents with college/university education correctly identified the use of antibiotics for UTI compared 21.2% of respondents with only primary school education (p = 0.000); and 20.0% of respondents having primary school education reported that they would use antibiotics for headaches compared to 12.7% of those with college/university education (p = 0.000).

Participants' knowledge regarding AMR was assessed through a set of eight statements and they were asked to select ‘true’, ‘false’ or ‘do not know’ responses.

Table 2 shows that less than half of the participants correctly identified any of the eight statements; Statements 2,3,4, and 5 were correctly identified by between 40-46% of participants, Statements 6,7, and 8 by approximately 35%, and Statement 1 by only 17.6% of participants.

AMR knowledge for each of these eight statements was compared based on participants’ education levels (

Table S1). There were statistically significant differences found for all eight statements with higher levels of knowledge were observed for participants with college/university education.

Knowledge Regarding Potential Solutions for Antimicrobial Resistance

Participants' knowledge regarding possible solutions/strategies to address AMR were assessed through eight statements rated on a 5-point Likert scale (strongly agree, slightly agree, neither slightly disagree, strongly disagree) (

Figure S1). The majority of participants correctly responded to all of the statements (≥60% slightly agreed/strongly agreed).

Knowledge about strategies/solutions to address AMR was also compared by the level of participants' education. There were significant differences found for all eight statements; participants with college/university educational levels exhibited greater knowledge compared to those with primary and secondary educational levels (

Table S2).

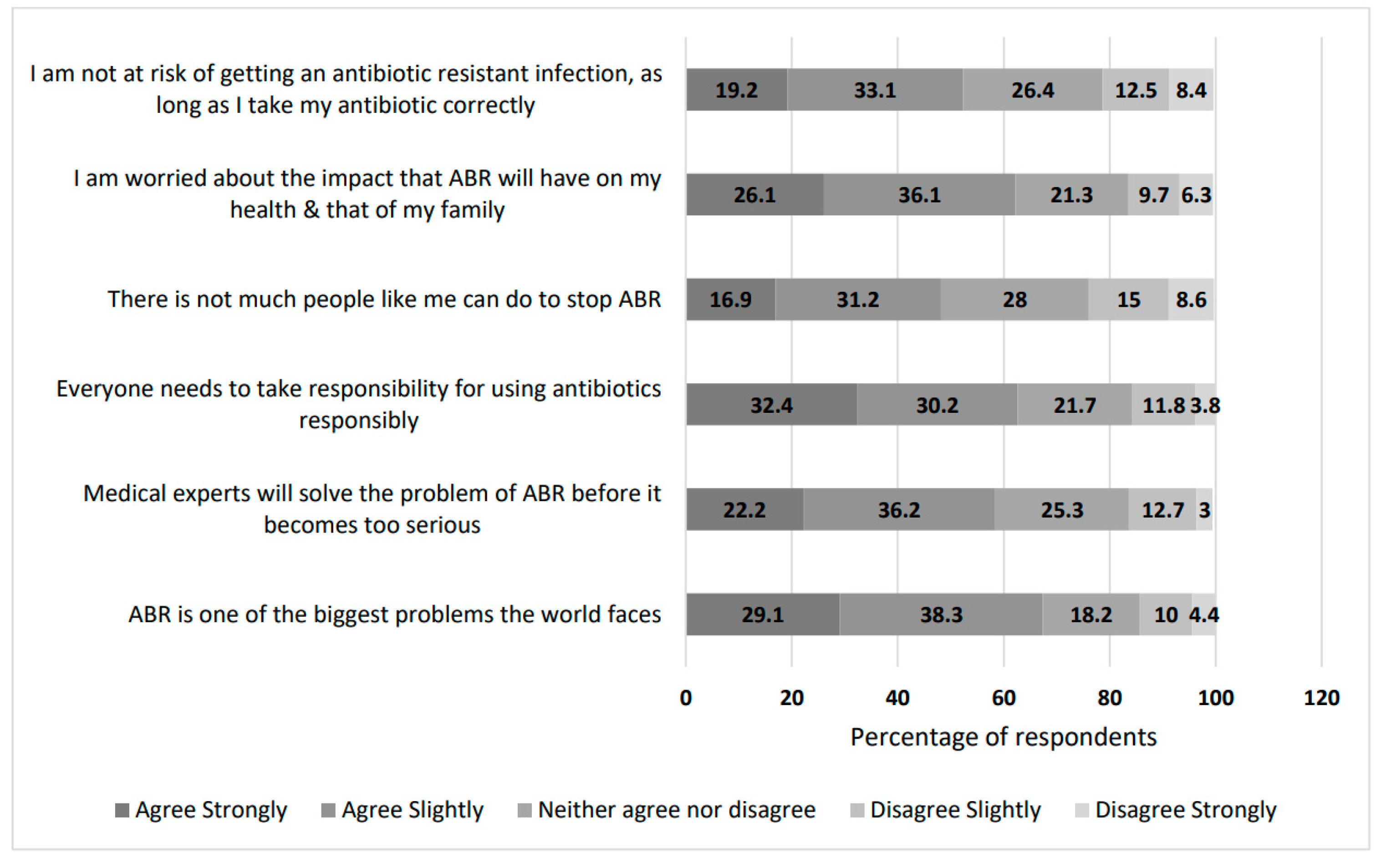

4.5. Attitudes and Beliefs Towards AMR

We assessed participants' attitudes and beliefs regarding AMR through a set of six statements rated on a 5-point Likert scale (strongly agree, slightly agree, neither slightly disagree, strongly disagree) (

Figure 2).

More than 60% of participants agreed/strongly agreed that AMR was a significant problem globally, everyone needed to take responsibility for appropriate antibiotic use, and they were concerned about the impact of AMR on themselves and their families. The statement regarding there was nothing the general public could do to prevent AMR had the lowest proportion of people who agreed/strongly agreed, however less than half (48.0%) of participants agreed/strongly agreed with this. Similar to the previous knowledge-based sections, participants with higher educational levels, such as college or university education, were more likely to agree/strongly agree with the attitude and belief statements (

Table S3).

4.6. Association Between Knowledge of Antibiotics and AMR and Participant Characteristics

Ten percent (10.6%) of participants had low knowledge, 70.1% had moderate knowledge, and 19.3% had high knowledge regarding antibiotics and AMR. Significant differences in knowledge levels were observed according to age, gender, marital status, province, and educational level of the participants (

Table 3).

5. Discussion

This comprehensive survey provides valuable insights into the patterns of antibiotic use, public knowledge, and awareness of AMR among the Sri Lankan population across four provinces. This study highlights the public's antibiotic-related knowledge and behaviors, emphasizing the need for targeted, education-focused interventions to address knowledge gaps, particularly among less educated groups, and to promote proper antibiotic use and strengthen Antimicrobial Stewardship (ASP) efforts.

Our findings reveal critical gaps in public knowledge of antibiotics and AMR. Approximately half of the participants reported adherence to prescriptions and sought professional advice; however, significant misconceptions persist. Common misunderstandings include premature cessation of antibiotics, using non-prescribed medications, and reliance on antibiotics for viral illnesses like colds or flu. These misconceptions highlight a public health challenge: inaccurate perceptions of antibiotics contribute to improper use, fostering AMR development. Non-completion of antibiotics contributes directly to AMR, as incomplete treatment may allow resistant bacteria to proliferate.

Educational disparities emerged as a strong predictor of knowledge levels. Those with higher education had better awareness and understanding of appropriate antibiotic use and AMR [

16], while those with only primary or secondary education showed notable gaps [

17,

18]. This trend underscores the need for public health strategies tailored to different education levels [

19,

20]. In particular, targeted campaigns could improve awareness among individuals with lower education levels through accessible and culturally relevant messaging.

Public health strategies were identified as pivotal for AMR prevention, with consensus among participants on the importance of initiatives such as promoting hospital handwashing [

18,

21], implementing hygiene, infection prevention, and control practices [

22], and incentives for developing new antibiotics [

23]. These insights align with global AMR containment strategies and suggest that Sri Lanka’s public health efforts should be amplified in these areas. Developing robust antimicrobial stewardship (AMS) programs [

21,

24] and public education campaigns [

25,

26] can correct misconceptions and support informed antibiotic use, ultimately aiding in the fight against AMR.

The study also highlights how Sri Lanka’s patterns compare to other countries. In contrast to findings in Saudi Arabia [

27] and Albania [

28] where a higher percentage of the population adheres to prescription requirements, Sri Lanka still faces challenges with non-prescription antibiotic access and use [

29,

30]. Various factors likely influence these differences, including regulatory strictness [

29,

31], accessibility of healthcare [

32], inappropriate prescribing practices [

31], and the strength of public health education [

33]. Countries with strong health literacy [

30,

32,

33] and public health campaigns [

27,

34] demonstrate better adherence to safe antibiotic practices. In Sri Lanka, implementing similar educational initiatives could significantly impact AMR by curbing self-medication practices.

The implications of improper antibiotic use, including incomplete treatment courses, are substantial. The tendency to discontinue antibiotics once symptoms improve was noted both in this study and in comparable studies from Iraq [

35] and East Indonesia [

20]. Incomplete antibiotic regimens not only fail to eradicate infections but also enable bacterial resistance to develop [

36]. Hence, healthcare providers should prioritize educating patients on the importance of completing antibiotic regimens and managing potential side effects to improve adherence. Several studies from Ethiopia [

37], Malaysia [

38] and Bangladesh [

39] revealed that educational interventions have increased adherence. Similar approaches could yield beneficial results in Sri Lanka.

In this study considerable proportion of participants mistakenly believed antibiotics to be effective for viral infections or compared them to painkillers for common ailments. This lack of distinction between bacterial and viral infections calls for specific educational outreach. Health professionals and pharmacists play a key role in bridging these knowledge gaps, as pharmacists are often the first point of advice in many low- and middle-income countries [

29,

40,

41]. However, where pharmacists lack sufficient training or regulation, they may inadvertently contribute to antibiotic misuse [

31].

Additionally, a notable number of respondents mistakenly believed that antibiotic resistance occurs when the human body, rather than bacteria, becomes resistant. This misconception aligns with findings from studies in Nigeria [

42], Singapore [

43], Norway [

44], and Malaysia [

45], indicating a global need for AMR education that accurately explains how resistance develops. Clear, relatable public health communication, such as workshops in schools, community centers, and healthcare facilities, can help address these misunderstandings.

The impact of education level on antibiotic knowledge is evident: participants with college or university education were more likely to correctly understand antibiotic effectiveness for conditions like UTIs [

46], gonorrhea [

42], and skin infections [

47]. Educated individuals often have better access to credible health information, fostering greater adherence to medical guidance [

22]. This observation underscores the importance of tailored educational interventions that equip all educational levels with essential knowledge on antibiotics and AMR. This highlights the need for educational interventions tailored to different demographic and educational groups. Public health campaigns should consider simplified, accessible materials for those with lower educational backgrounds to ensure broader reach and understanding.

Healthcare professionals should actively educate patients on when antibiotics are appropriate, the necessity of completing prescribed courses, and the distinctions between bacterial and viral infections [

40]. They must also adhere to guidelines for responsible antibiotic prescribing to prevent resistance development [

31]. Following up with patients to ensure regimen adherence and to discuss potential misuse may further enhance outcomes [

30].

5.1. Strengths and Limitations of the Study

This study’s strengths include its high response rate and diverse sample, covering urban and rural areas across various hospitals, enhancing its generalizability to Sri Lanka’s broader population. The multi-language questionnaire likely increased comprehension, and restrictions on taking questionnaires home improved data integrity by reducing the likelihood of consulted responses.

However, limitations include the potential for socially desirable responses inherent to questionnaire-based studies and the restriction to hospital-based participants, who may not fully represent those outside healthcare settings. Future studies could include qualitative methods to gain deeper insights into participants’ attitudes and beliefs regarding antibiotics and AMR.

6. Conclusions

This study reveals significant gaps in general public understanding and practices on antibiotic use and AMR in Sri Lanka, especially among those with lower education levels. Despite some adherence to prescriptions, widespread misconceptions, such as stopping antibiotics early and using them for viral illnesses, underscore the need for targeted educational initiatives. Enhancing public awareness through ASP programs and accessible health education can address these knowledge gaps, promoting responsible antibiotic use and supporting AMR prevention efforts. These findings lay the groundwork for effective public health strategies that empower communities and help combat AMR in Sri Lanka.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1: Comparison of AMR knowledge across educational levels Figure S1: Knowledge about solutions/strategies to address AMR Table S2: Comparison of knowledge about solutions/strategies to address AMR by education status. Table S3: Comparison of attitudes and beliefs to AMR by education status

Author Contributions

S. Mathanki contributed to the development of the research proposal, study design, and preparation of the data collection instrument, including conducting the pilot study, under the guidance of M.H.F. Sakeena, F. Mohamed, and HDWT Damayanthi. S. Mathanki also played a key role in the implementation of the study and data collection. S. Mathanki, M.H.F. Sakeena, and F. Mohamed were involved in the data analysis and interpretation, and they collectively drafted the manuscript. M.H.F. Sakeena, F. Mohamed, and HDWT Damayanthi revised and approved the final manuscript for submission.

Funding

University Research Grant; URG/2021/02/AHS. The grant does not include provisions to cover the publication processing fee.

Informed Consent Statement

Ethical approval was obtained from the Ethics Review Committee of Faculty of Allied Health Sciences, University of Peradeniya (Ref: AHS/ERC/2020/026; 30th November 2020). Administrative approval from the Directors of the four selected Sri Lankan hospitals were obtained. This research was undertaken as part of an MPhil study in October 2022-February 2023. Informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Data Availability Statement

The identified study datasets are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank everyone who participated in the study. We would also like to thank the CASPPER (Collaboration of Australians and Sri Lankans for Pharmacy Practice, Education and Research) mentors for providing the opportunity to attend the Writing Workshop in Sri Lanka in July 2024, in particular Professor Amanda Wheeler, Griffith University, who led the workshop and for her support in drafting this manuscript. I used ChatGPT, to assist with language refinement, drafting, and enhancing the clarity of certain sections.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Abbreviations

AMR—Antimicrobial resistance, ASP—Antimicrobial Stewardship.

References

- Unit E: Ministry of Health N& IM. WEEKLY EPIDEMIOLOGICAL REPORT A publication of the Epidemiology Unit Ministry of Health. Wkly Epidemiol Rep. 2017;44(August):1–4.

- WHO | Antibiotic resistance: Multi-country public awareness survey. WHO. 2016 [cited 2020 Jan 25];https://www.who.int/drugresistance/documents/baselinesurveynov2015/en/#.

- Varma JK, Oppong-Otoo J, Ondoa P, Perovic O, Park BJ, Laxminarayan R, et al. Africa Centres for Disease Control and Prevention’s framework for antimicrobial resistance control in Africa. Afr J Lab Med. 2018;7(2). [CrossRef]

- Murray CJ, Ikuta KS, Sharara F, Swetschinski L, Robles Aguilar G, Gray A, et al. Global burden of bacterial antimicrobial resistance in 2019: a systematic analysis. Lancet. 2022;399(10325):629–55. [CrossRef]

- World Health Organisation. Global action plan on antimicrobial resistance. WHO Press. 2015.

- Khadse SN, Ugemuge S, Singh C. Impact of Antimicrobial Stewardship on Reducing Antimicrobial Resistance. Cureus. 2023;15(12):1–9. [CrossRef]

- Yong MK, Buising KL, Cheng AC, Thursky KA. Improved susceptibility of Gram-negative bacteria in an intensive care unit following implementation of a computerized antibiotic decision support system. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2010;65(5):1062–9. [CrossRef]

- Jimah T, Fenny AP, Ogunseitan OA. Antibiotics stewardship in Ghana: a cross-sectional study of public knowledge, attitudes, and practices among communities. One Heal Outlook. 2020;2(1). [CrossRef]

- Dekker ARJ, Verheij TJM, van der Velden AW. Inappropriate antibiotic prescription for respiratory tract indications: most prominent in adult patients. Fam Pract. 2015 Aug 1 [cited 2023 Apr 23];32(4):401–7. [CrossRef]

- MacDougall C, Polk RE. Antimicrobial stewardship programs in health care systems. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2005;18(4):638–56. [CrossRef]

- Epidemiology Unit Ministry of Health. Weekly Epidemiological Report. Wkly Epidemiol Rep. 2018;40(September):1–4.

- Zawahir S, Lekamwasam S, Aslani P. Antibiotic dispensing practice in community pharmacies: A simulated client study. Res Soc Adm Pharm. 2019;15(5):584–90. [CrossRef]

- Shelke YP, Bankar NJ, Bandre GR, Hawale D V, Dawande P. An Overview of Preventive Strategies and the Role of Various Organizations in Combating Antimicrobial Resistance. Cureus. 2023;15(9).

- Gunasekera YD, Kinnison T, Kottawatta SA, Silva-Fletcher A, Kalupahana RS. Misconceptions of Antibiotics as a Potential Explanation for Their Misuse. A Survey of the General Public in a Rural and Urban Community in Sri Lanka. Antibiotics. 2022;11(4). [CrossRef]

- Zawahir S, Lekamwasam S, Halvorsen KH, Rose G, Aslani P. Self-medication Behavior with antibiotics: a national cross-sectional survey in Sri Lanka. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther. 2021;19(10):1341–52.

- Tangcharoensathien V, Chanvatik S, Kosiyaporn H, Kirivan S. Population knowledge and awareness of antibiotic use and antimicrobial resistance : results from national household survey 2019 and changes from 2017. BMC Public Health. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Rijal KR, Banjara MR, Dhungel B, Kafle S, Gautam K, Ghimire B, et al. Use of antimicrobials and antimicrobial resistance in Nepal: a nationwide survey. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1):1–14.

- Sindato C, Mboera LEG, Katale BZ, Frumence G, Kimera S, Clark TG, et al. Knowledge, attitudes and practices regarding antimicrobial use and resistance among communities of Ilala, Kilosa and Kibaha districts of Tanzania. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control. 2020;9(1):1–17. [CrossRef]

- Gillani AH, Chang J, Aslam F, Saeed A, Shukar S, Khanum F, et al. Public knowledge, attitude, and practice regarding antibiotics use in Punjab, Pakistan: a cross-sectional study. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther. 2021;19(3):399–411. [CrossRef]

- Kurniawan, Posangi J, Rampengan N. Association between public knowledge regarding antibiotics and self-medication with antibiotics in Teling Atas Community Health Center, East Indonesia. Med J Indones. 2017;26(1):62–9.

- Shelke YP, Bankar NJ, Bandre GR, Hawale D V, Dawande P. An Overview of Preventive Strategies and the Role of Various Organizations in Combating Antimicrobial Resistance. Cureus. 2023;15(9). [CrossRef]

- Geta K, Kibret M. Knowledge, Attitudes and Practices of Patients on Antibiotic Resistance and Use in Public Hospitals of Amhara Regional State, Northwestern Ethiopia: A Cross-Sectional Study. Infect Drug Resist. 2022 Jan 22 [cited 2022 Aug 2];15:193–209.

- Geta K, Kibret M. Knowledge, Attitudes and Practices of Patients on Antibiotic Resistance and Use in Public Hospitals of Amhara Regional State, Northwestern Ethiopia: A Cross-Sectional Study. Infect Drug Resist. 2022;15(January):193–209.

- Majumder MAA, Rahman S, Cohall D, Bharatha A, Singh K, Haque M, et al. Antimicrobial stewardship: Fighting antimicrobial resistance and protecting global public health. Infect Drug Resist. 2020;13:4713–38. [CrossRef]

- Abujheisha KY, Al-Shdefat R, Ahmed N, Fouda MI. Public Knowledge and Behaviours Regarding Antibiotics Use: A Survey among the General Public. Int J Med Res Heal Sci. 2017;6(6):82–8.

- Sadasivam K, Chinnasami B, Ramraj B, Karthick N, Saravanan A. Knowledge, attitude and practice of paramedical staff towards antibiotic usage and its resistance. Biomed Pharmacol J. 2016;9(1):337–43. [CrossRef]

- Alnasser AHA, Al-Tawfi JA, Ahmed HAA, Alqithami SMH, Alhaddad ZMA, Rabiah ASM, et al. Public knowledge, attitude and practice towards antibiotics use and antimicrobial resistance in Saudi Arabia: A web-based cross-sectional survey. J Public health Res. 2021 Oct 10 [cited 2022 Aug 2];10(4). [CrossRef]

- Bushi E, Gashi Z, Malaj L. Evaluation of the Knowledge, Attitude and Public Awareness about the Use of Antibiotics and Antibiotic Resistance in Albania. Indian J Pharm Educ Res. 2024;58(1):316–25. [CrossRef]

- Sakeena MHF, Bennett AA, Jamshed S, Mohamed F, Herath DR, Gawarammana I, et al. Investigating knowledge regarding antibiotics and antimicrobial resistance among pharmacy students in Sri Lankan universities. BMC Infect Dis. 2018;18(1):209. [CrossRef]

- Zawahir S, Lekamwasam S, Aslani P. Factors related to antibiotic supply without a prescription for common infections: A cross-sectional national survey in Sri Lanka. Antibiotics. 2021;10(6). [CrossRef]

- Sakeena MHF, Bennett AA, McLachlan AJ. Non-prescription sales of antimicrobial agents at community pharmacies in developing countries: a systematic review. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2018;52(6):771–82. [CrossRef]

- Dyar OJ, Beović B, Vlahović-Palčevski V, Verheij T, Pulcini C. How can we improve antibiotic prescribing in primary care? Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther. 2016;14(4):403–13.

- Zaniboni D, Ceretti E, Gelatti U, Pezzotti M, Covolo L. Antibiotic resistance: is knowledge the only driver for awareness and appropriate use of antibiotics? Ann di Ig Med Prev e di Comunita. 2021;33(1):21–30.

- Naing S, van Wijk M, Vila J, Ballesté-Delpierre C. Understanding antimicrobial resistance from the perspective of public policy: A multinational knowledge, attitude, and perception survey to determine global awareness. Antibiotics. 2021;10(12). [CrossRef]

- Al-Taie A, Hussein AN, Albasry Z. A Cross-Sectional Study of Patients’ Practices, Knowledge and Attitudes of Antibiotics among Iraqi Population. J Infect Dev Ctries. 2021;15(12):1845–53. [CrossRef]

- Kouyos RD, Metcalf CJE, Birger R, Klein EY, zur Wiesch PA, Ankomah P, et al. The path of least resistance: Aggressive or moderate treatment? Proc R Soc B Biol Sci. 2014;281(1794).

- Ayele Y, Mamu M. Assessment of knowledge, attitude and practice towards disposal of unused and expired pharmaceuticals among community in Harar city, Eastern Ethiopia. J Pharm Policy Pract. 2018;11(1). [CrossRef]

- Hassali MA, Arief M, Saleem F, Khan MU, Ahmad A, Mariam W, et al. Assessment of attitudes and practices of young Malaysian adults about antibiotics use: A cross-sectional study. Pharm Pract (Granada). 2017;15(2):1–7.

- Ahmed I, Rabbi MB, Rahman M, Tanjin R, Jahan S, Khan MAA, et al. Knowledge of antibiotics and antibiotic usage behavior among the people of Dhaka, Bangladesh. Asian J Med Biol Res. 2020;6(3):519–24. [CrossRef]

- Sakeena MHF, Bennett AA, McLachlan AJ. Enhancing pharmacists’ role in developing countries to overcome the challenge of antimicrobial resistance: A narrative review. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control. 2018;7(1). [CrossRef]

- Sakeena MHF, Bennett AA, Carter SJ, McLachlan AJ. A comparative study regarding antibiotic consumption and knowledge of antimicrobial resistance among pharmacy students in Australia and Sri Lanka. PLoS One. 2019;14(3):1–14. [CrossRef]

- Chukwu EE, Oladele DA, Awoderu OB, Afocha EE, Lawal RG, Abdus-Salam I, et al. A national survey of public awareness of antimicrobial resistance in Nigeria. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control. 2020;9(1):1–10. [CrossRef]

- Lim JM, Duong MC, Cook AR, Hsu LY, Tam CC. Public knowledge, attitudes and practices related to antibiotic use and resistance in Singapore: A cross-sectional population survey. BMJ Open. 2021;11(9):1–10. [CrossRef]

- Waaseth M, Adan A, Røen IL, Eriksen K, Stanojevic T, Halvorsen KH, et al. Knowledge of antibiotics and antibiotic resistance among Norwegian pharmacy customers - A cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health. 2019;19(1):1–12.

- Irawati L, Alrasheedy AA, Hassali MA, Saleem F. Low-income community knowledge, attitudes and perceptions regarding antibiotics and antibiotic resistance in Jelutong District, Penang, Malaysia: A qualitative study. BMC Public Health. 2019;19(1):1–15. [CrossRef]

- Yusef D, Babaa AI, Bashaireh AZ, Al-Bawayeh HH, Al-Rijjal K, Nedal M, et al. Knowledge, practices & attitude toward antibiotics use and bacterial resistance in Jordan: A cross-sectional study. Infect Dis Heal. 2018;23(1):33–40. [CrossRef]

- Gabriel S, Manumbu L, Mkusa O, Kilonzi M, Marealle AI, Mutagonda RF, et al. Knowledge of use of antibiotics among consumers in Tanzania. JAC-Antimicrobial Resist. 2021;3(4):1–8.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).