1. Introduction

According to Glover (1990), “Tabu search is a “higher level” heuristic procedure for solving optimization problems, designed to guide other methods (or their component processes) to escape the trap of local optimality. Tabu search has obtained optimal and near optimal solutions to a wide variety of classical and practical problems in applications ranging from scheduling to telecommunications and from character recognition to neural networks. It uses flexible structures memory (to permit search information to be exploited more thoroughly than by rigid memory systems or memoryless systems), conditions for strategically constraining and freeing the search process (embodied in tabu restrictions and aspiration criteria), and memory functions of varying time spans for intensifying and diversifying the search (reinforcing attributes historically found good and driving the search into new regions). Tabu search can be integrated with branch-and-bound and cutting plane procedures, and it has the ability to start with a simple implementation that can be upgraded over time to incorporate more advanced or specialized elements.“. In the N-Queens problem, the goal is to arrange N queens on an board such that no two queens share the same row, column, or diagonal.

Initially, the professor suggested using a matrix to control the swaps, where the upper triangle would indicate the iteration until a swap would be blocked and the lower triangle would count the frequency of swaps. However, to reduce complexity, I opted to implement a first version using two separate lists to track the swaps and the blocking iterations, and a final version that focuses on swapping only conflicting queens. All algorithms were implemented in Python 3.9.

2. Problem Definition

The N-Queens problem aims to minimize the conflicts between queens, as shown in Equation (

1):

where

if

and

are in conflict, and 0 otherwise.

3. Methodology

This section describes the implementation process and the improvements introduced in both versions of the algorithm.

3.1. First Implementation: Control Lists for Swaps and Blocking

The first implementation used two lists to manage swaps and blocking. One list tracked the swaps made and their respective counts, while the other stored the number of blocking iterations associated with each swap. This method significantly reduced complexity compared to the professor’s suggested implementation, which used a matrix to store this information. However, this approach still required constant monitoring of swaps and blocking.

3.2. Second Implementation: Focused Swaps on Conflicting Queens

In the second and more efficient implementation, I simplified the algorithm by eliminating the blocking lists and focusing exclusively on conflicting queens. Below, I describe the main details of this approach.

Evaluation Function (funcaoObjetivo): The function identifies conflicts by checking if two queens share the same diagonal, storing this information in sets to facilitate checking. In addition to returning the number of conflicts, the function generates a list of conflicting queens, used in the neighbor generation.

Neighbor Generation (gerarVizinho): In this version, the neighbor generation function only performs swaps between conflicting queens. One position is randomly selected from the conflicting queens, and another random position is chosen for the swap, which reduces the number of swaps and keeps the focus on queens that are causing problems.

Tabu Search Loop (buscaTabu): The search loops until all conflicts are resolved or the maximum number of iterations is reached. In each iteration, a neighbor is generated, and if this reduces the number of conflicts, it replaces the current solution. The search can also be executed multiple times until a fitness of 0 is found through the variable rodarAteEncontrarZero.

3.3. Aspiration Criteria

The aspiration criteria in Tabu Search allow moves blocked by the tabu list to be re-evaluated and potentially accepted if they meet specific conditions that make them advantageous. An example of this occurs when all possible swaps are blocked; in this case, the aspiration criterion can free the least frequent swap until that moment. This criterion is particularly useful in problems where neighborhood exploration often leads to local minima, helping the algorithm escape these regions and continue searching for more promising solutions.

3.3.1. Application of Aspiration Criteria to the N-Queens Problem

However, in the context of the N-Queens problem, the use of aspiration criteria was unnecessary. This is because, in the optimized implementation, the neighbor generation is restricted only to conflicting queens, which minimizes the risk of revisiting undesirable or inefficient configurations. Thus, the algorithm avoids local minima without the need to unblock tabu solutions, focusing directly on resolving the existing conflicts and ensuring faster and more efficient convergence. Therefore, the code structure and strategy of focusing on conflicting queens made the aspiration criterion redundant, simplifying the implementation and maintaining high performance.

3.4. Parameterization

For the Tabu Search algorithm to work in the context of the N-Queens problem, the following parameters are used:

Maximum Iterations: Defines the maximum number of times the algorithm will attempt to find a conflict-free solution, preventing an infinite loop in cases where the solution is hard to optimize.

Board Size: Determines the value of N, the number of queens, and the size of the board, which impacts the complexity of the problem and the execution time.

Execution until Conflict-Free Solution: This parameter controls whether the algorithm should continue searching until it finds a perfect solution or if it can stop once the iteration limit is reached. This allows for adjusting the exhaustiveness level of the search.

4. Results

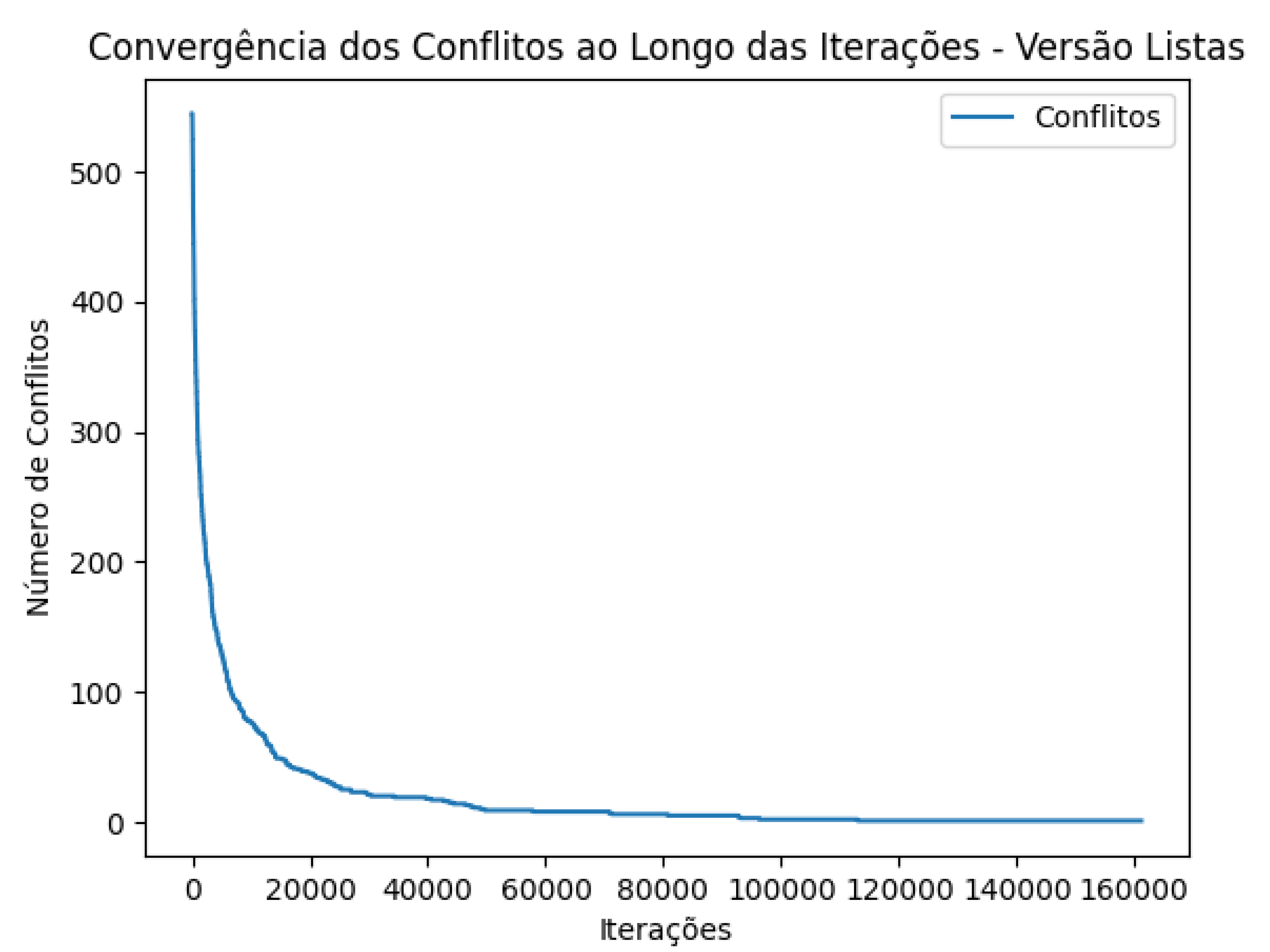

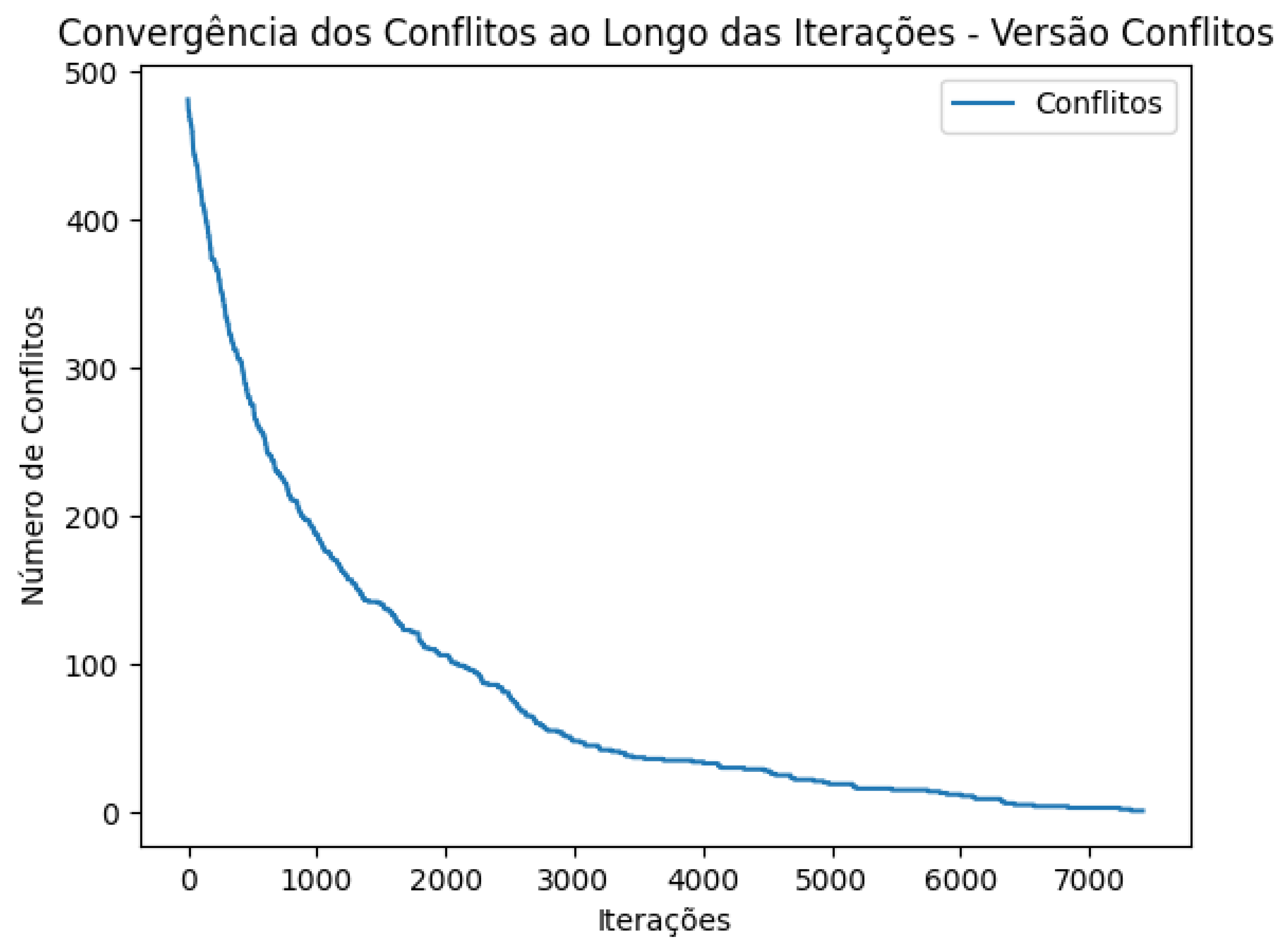

For

, the second implementation exhibited significantly faster convergence compared to the first, as illustrated in

Figure 1 (Convergence Graph for the First Implementation) and

Figure 2 (Convergence Graph for the Second Implementation). This result demonstrates a substantial improvement in the efficiency of the algorithm by adopting a more focused approach to conflict resolution.

The experiments were conducted on a Ryzen 5 5500U processor, a widely used model for medium-scale computational tasks. In this environment, the first implementation took an average of 450 seconds to complete execution, whereas the second managed to solve the problem in just 1.5 seconds, an extremely significant difference. This reduction in execution time reinforces the importance of more refined strategies in optimizing the N-queens problem.

It is important to highlight that the tests were performed until the algorithm reached a solution with a fitness value of zero, ensuring the quality of the obtained result. During this process, the first implementation required approximately 160,000 iterations to converge, while the second, by focusing exclusively on conflicting queens, achieved the same result in about 7,000 iterations, demonstrating a drastic reduction in the number of required steps.

Table 1 provides a detailed summary of the performance comparison between the two approaches, highlighting the superiority of the second implementation in terms of computational efficiency.

5. Conclusions

The analysis of the results in

Table 1 and

Figure 1 and

Figure 2 reveals significant differences in efficiency between the two implementations of the Tabu Search algorithm for the N-Queens problem. The final implementation, which focuses on swaps between conflicting queens, demonstrated faster convergence and superior performance compared to the initial version with control lists.

The data show that while the first implementation took 450 seconds to solve the problem with 1000 queens, the optimized version completed the task in just 1.5 seconds. This improvement is attributed to the neighbor generation strategy, which avoids unnecessary swaps and focuses on the queens causing conflicts. By analyzing conflicts for neighbor generation, the complexity is reduced, and the overall efficiency of the algorithm improves.

These results highlight the importance of optimizing neighbor generation in search algorithms, demonstrating that identifying and resolving specific problems can significantly enhance performance.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).