I. Introduction

Hydrodynamic cavitation occurs when, in a moving fluid, the pressure drops below the vapor tension (ρ_v), causing the formation of bubbles that, upon collapse, rapidly release energy in the form of shock waves [

1,

2]. The pioneering work of Brennen [

1] and the contributions of Franc and Michel [

2] provided the theoretical foundations for understanding this phenomenon, which is now applied in industrial processes such as the extraction of active ingredients, sanitation, and the optimization of chemical reactions [

3,

4,

5,

6,

7].

Bernoulli’s equation, expressed as:

is fundamental for understanding the pressure recovery along the flow; however, circular-section Venturi tubes show limitations in generating extremely high pressure gradients. The Reuleaux Triangle (VRA) stands out precisely for its high Perimeter/Area ratio, which allows for a more rapid and intense pressure recovery, thereby increasing the pressure difference (Δp). Studies by Rayleigh [

1] and further investigations by Drake [

28] have shown that an increase in Δp reduces collapse times and increases the implosion speed of bubbles. These results, together with further research on future applications [

11,

31,

32], suggest that the VRA may offer more efficient and sustainable solutions for water treatment and the extraction of bioactive compounds.

II. Mathematical Comparison Between Circular Venturi and VRA

A. Perimeter and Area

As highlighted in (2), the VRA exhibits a higher P/A ratio, meaning that per unit area the fluid interacts with a larger surface, generating more intense pressure gradients.

B. Pressure Difference (Δp)

The pressure difference, defined as the gap between the recovery pressure and the vapor tension, is commonly expressed through Bernoulli’s equation (1). In traditional devices, this Δp is limited by classical geometries, whereas the VRA, thanks to its higher Perimeter/Area configuration, enables a more rapid pressure recovery and consequently a significant increase in Δp. Studies conducted by Randall [

3] have shown that higher pressure gradients can intensify the cavitation phenomenon, while Kaneko et al. [

4] demonstrated that a high Δp contributes to greater efficiency in extraction and purification processes. These findings suggest that the VRA, with its increased Δp, offers operational advantages over circular models.

C. Collapse Time and Velocity

Several studies, beginning with those of Rayleigh [

1], have highlighted the importance of the relationship between Δp and bubble behavior. According to these studies, an increase in Δp results in a reduction in collapse time—making the process faster—and a higher implosion velocity of the bubbles. Drake [

28] further elaborated on this concept, emphasizing that devices with high Δp, such as the VRA, generate more violent and rapid bubble implosions. This effect is crucial for industrial applications that require a strong energy release, for example, to break down cellular structures during the extraction of bioactive compounds or to enhance water purification processes.

D. Shock Pressure

The shock pressure developed during bubble collapse is a key indicator of cavitation effectiveness. For example, Charrière et al. [

10] conducted experiments demonstrating that an increase in the pressure gradient—i.e., a higher Δp—leads to shock waves of significantly greater intensity. Similarly, Escaler et al. [

12] developed numerical models that confirm that a higher collapse velocity, directly correlated with an elevated Δp, translates into intensified shock pressure. These observations clearly indicate that the VRA, capable of generating a higher Δp, produces much more violent bubble implosions—essential for industrial applications that require a robust energy release to break up aggregates or cellular structures. Such evidence is further supported by studies showing that greater pressure gradients result in more intense shock pressure, significantly enhancing the overall effectiveness of cavitation applications [

10,

12].

III. Comparison of Operational Performance

It is clear that, at equal flow rate, the VRA generates a higher Δp compared to the circular Venturi tube. This increase, achieved through a more rapid pressure recovery, leads to shorter bubble collapse times and a higher implosion velocity. These effects combine to produce an intensified shock pressure, a fundamental element for improving cavitation effectiveness. In practical terms, the VRA enables more violent bubble implosions that can break down cellular structures or contaminant aggregates, thus enhancing processes such as the extraction of bioactive compounds and water treatment. These results, supported by both theoretical models and experimental evidence, demonstrate the operational superiority of the VRA over the circular model.

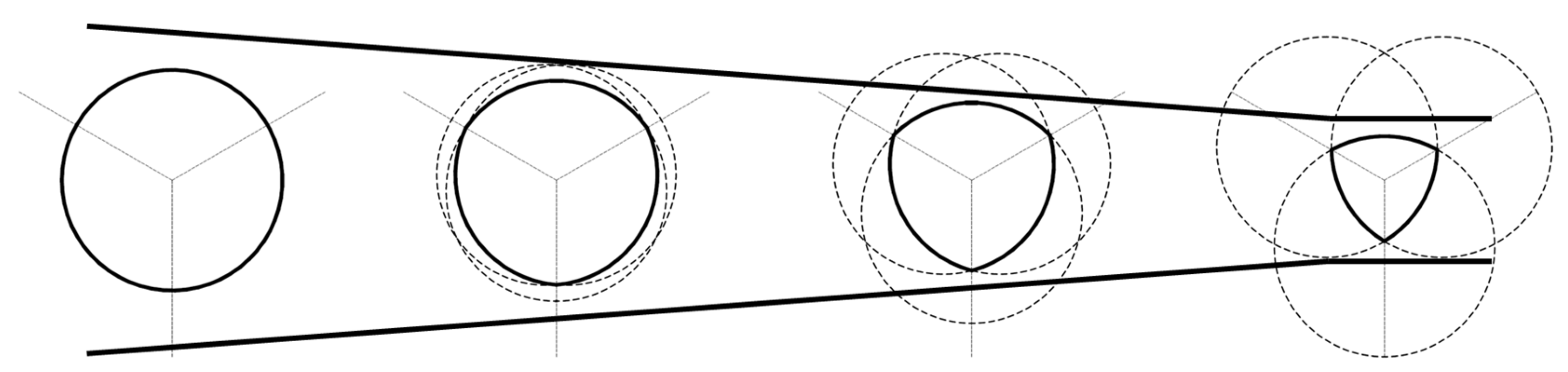

IV. Transition from Circular Section to VRA

It is appropriate to describe the geometric transformation process from the classic circular-section Venturi tube to the new VRA.

Figure 1.

Transition from the circular section to the Reuleaux section.

Figure 1.

Transition from the circular section to the Reuleaux section.

The figure shows how a tube with a circular section can be gradually transformed into a VRA section. This transformation can be achieved through electroerosion [

30].

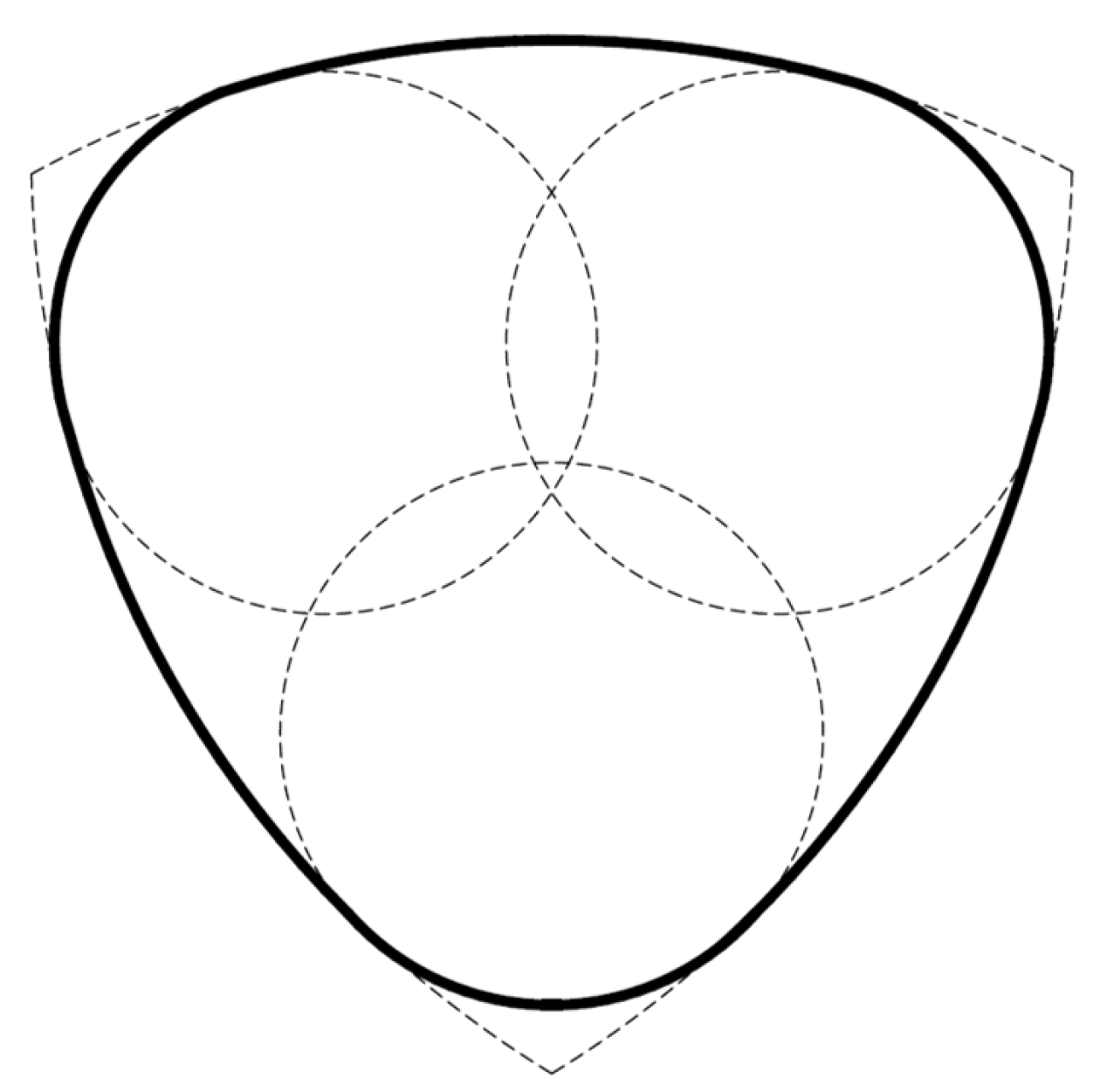

V. Internal Section

A possible internal configuration is illustrated, characterized by curvatures designed to evenly distribute energy during bubble collapse and to reduce the risk of friction, erosion, and the accumulation of solid particles.

Figure 2.

Internal geometry of the VRA with curvatures designed to reduce friction, erosion, and solid deposits.

Figure 2.

Internal geometry of the VRA with curvatures designed to reduce friction, erosion, and solid deposits.

This solution was designed because sharp angles can create zones of stress concentration. Shad’s work [

11] highlights the importance of developing configurations that minimize the effects of friction and erosion, while Silva et al. [

14] show that an accurate internal design increases durability and operational reliability. Thus, the VRA not only intensifies the cavitation phenomenon due to the higher Δp, but also ensures high performance under extreme operating conditions.

VI. Future Applications

The potential applications of the VRA extend to numerous industrial sectors. In the food industry, for instance, the VRA could revolutionize the extraction of bioactive compounds from plant raw materials, improving both yield and extract quality through its ability to facilitate the breakdown of cellular structures [

31]. Similarly, in the beverage sector, the VRA can optimize both sterilization and mixing processes, reducing processing times and ensuring higher-quality final products. In the pharmaceutical field, the adoption of the VRA for the extraction of active ingredients and the formulation of emulsions and suspensions promises to enhance product efficacy and bioavailability. Furthermore, the VRA’s ability to generate intense shock waves makes it particularly suitable for water treatment and purification, facilitating the removal of both organic and inorganic contaminants [

32].

In the future, pilot tests will be necessary to verify the VRA’s performance in the field. Shad’s research [

11] underscores the importance of developing configurations that reduce friction and erosion effects, ensuring consistent performance. Meneguzzo’s work [

15] suggests that refined geometric modifications can intensify chemical reactions in industrial processes. These findings, together with numerous experimental and theoretical studies, open new prospects for the industrial application of the VRA.

VII. Conclusions

The Venturi Reuleaux Triangle (VRA) represents a significant evolution compared to the traditional circular Venturi tube, thanks to its high Perimeter/Area ratio that enables the generation of more intense pressure gradients and more violent bubble collapses [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10]. By adopting an innovative configuration, the VRA achieves a higher Perimeter/Area ratio, which explains the increase in pressure difference (Δp) observed in the studies of Randall [

3] and Kaneko et al. [

4].

The analyses by Rayleigh [

1] and the further insights by Drake [

28] indicate that a higher Δp leads to shorter collapse times and a greater collapse velocity, thereby generating shock waves of higher intensity. This aspect is further confirmed by the experimental work of Charrière et al. [

10] and the numerical models developed by Escaler et al. [

12], which demonstrate that higher pressure gradients translate into intensified shock pressure—significantly improving the effectiveness of cavitation processes. Similarly, studies by Shad [

11] emphasize the importance of developing configurations that reduce friction and erosion effects, ensuring performance stability over time. These results suggest that, thanks to its innovative configuration, the VRA may prove to be superior and more efficient compared to traditional circular models.

References

- Brennen, C.E. Cavitation and Bubble Dynamics, Oxford University Press, 1995.

- Franc, J.P.; Michel, J.M. Fundamentals of Cavitation, Kluwer Academic Publishers, 2004.

- Randall, L.N. Rocket applications of the cavitating Venturi. J. Am. Rocket Soc. 1952, 22, 28–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaneko, A.; Takagi, S.; Nomura, Y. Bubble Break-up Phenomena in Venturi Tubes. JSME 2012, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dular, M.; Khlifa, I.; Fuzier, S.; Maiga, S.A.; Coutier-Delgosha, O. Scale Effects on Unsteady Cloud Cavitation. Exp. Fluids 2012, 53, 1233–1250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, D.A.; Pun, K.; Ganesan, P.B.; Hamad, F. Effects of Throat Length on Venturi Cavitation. ASME J. Fluids Eng. 2020, 142. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.; Wu, Q.; Huang, B.; Zhang, H.; Liang, W. Decomposition of Unsteady Cavitation Dynamics in Fluid–Structure Interaction. Int. J. Multiph. Flow 2021, 142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbasi, E.; Saadat, S.; Jashni, A.K.; Shafaei, M.H. Optimization of Slit Venturi. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2020, 67. [Google Scholar]

- Tomov, P.; Ravelet, F.; et al. Experimental study aerated cavitation in a horizontal Venturi nozzle. Exp. Therm. Fluid Sci. 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charrière, B.; Decaix, J.; Goncalvès, E. A Comparative Study of Cavitation Models in a Venturi Flow. Eur. J. Mech. B/Fluids 2015, 49, 287–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shad, R. Application of Venturi cavitation in advanced oxidation processes. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2021, 72, 105298. [Google Scholar]

- Escaler, R.; et al. Experimental investigation of cavitation in Venturi flows. Fluid Dyn. Res. 2010, 42. [Google Scholar]

- Corrigan, M.T.; Kling, S.G. Experimental Analysis of Non-Circular Venturi Geometry for Cavitating Flows. J. Fluid Power 2019, 12. [Google Scholar]

- Silva, A.; Paiva, L. On the erosion and turbulence in cavitating Venturi flows. Int. J. Multiph. Flow 2021, 135. [Google Scholar]

- Meneguzzo, F.; Albanese, L. Intensification of the Dimethyl Sulfide Precursor Conversion Reaction: A Retrospective Analysis of Pilot-Scale Brewer’s Wort Boiling Experiments Using Hydrodynamic Cavitation. Beverages 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Presentato, A.; Piacenza, E.; Scurria, A.; et al. Antibacterial Activity of Lemon IntegroPectin Against Escherichia coli. ChemistrySelect 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Albanese, L.; Ciriminna, R.; Meneguzzo, F.; Pagliaro, M. Beer-brewing powered by controlled hydrodynamic cavitation: Theory and real-scale experiments. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flori, L.; Albanese, L.; Calderone, V.; Testai, L. Cardioprotective Effects of Grapefruit IntegroPectin Extracted via Hydrodynamic Cavitation from By-Products of Citrus Fruits Industry: Role of Mitochondrial Potassium Channels. Foods 2022, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shad, R. Application of Venturi cavitation in advanced oxidation processes for water treatment. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2021, 72, 105298. [Google Scholar]

- Kamath, M.A.S.; Gopalakrishnan, K.M. Analysis of cavitation in Venturi nozzles: An experimental study. Exp. Fluids 2007, 42, 789–798. [Google Scholar]

- Piacenza, E.; Presentato, A.; Alduina, R.V.; Martino, D.F.C. Cross-linked natural IntegroPectin films from citrus biowaste with intrinsic antimicrobial activity. Cellulose 2022, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Presentato, A.; Piacenza, E.; Scurria, A.; et al. Antibacterial Activity of Lemon IntegroPectin Against Escherichia coli: Implications for Food Packaging. ChemistrySelect 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Bauer, S.G. Advanced Reuleaux-Based Nozzle Geometry for Enhanced Cavitation. J. Hydrodyn. Eng. 2024, 91. [Google Scholar]

- Dey, T.K.; Sinha, P.K. Numerical simulation of cavitation in a Venturi nozzle. J. Fluids Eng. 2012, 134, 1215–1223. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, R.P.; Gupta, S. Reuleaux triangle geometry: A new design approach in fluid machinery. Int. J. Mech. Sci. 2015, 57, 533–541. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, A.B. Recent advances in cavitation research: A review. Prog. Energy Combust. Sci. 2014, 44, 109–134. [Google Scholar]

- Drake, J.L. Cavitation in fluid flows: A modern perspective. J. Fluid Mech. 2012, 690, 1–39. [Google Scholar]

- Escaler, R.; et al. Experimental investigation of cavitation in Venturi flows. Fluid Dyn. Res. 2010, 42. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, J.D.; Johnson, M.K.; Nguyen, L.R. Electrical Discharge Machining of Non-standard Geometries for Fluid Dynamic Applications. J. Manuf. Process. 2020, 45, 123–130. [Google Scholar]

- Patel, A.K. Advanced EDM techniques for fabricating complex shapes. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2019, 107, 987–994. [Google Scholar]

- Rossi, M.; Bianchi, F.; Verdi, G. Innovative Applications of Hydrodynamic Cavitation in the Food Industry. Food Eng. Rev. 2020, 12, 210–223. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, S.; Kim, H.; Park, J. Cavitation-Enhanced Water Treatment: A Review of Industrial Applications. Water Res. 2020, 162, 160–174. [Google Scholar]

|

Note: VRA stands for “Venturi Reuleaux Albanese.” |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).