Submitted:

14 March 2025

Posted:

17 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Ligand and Protein Preparation

2.2. Grid Box Adjust and Binding Site Identification

2.3. Molecular Docking Simulation

2.4. Chemical Reagents for In-Vitro Investigations

2.5. Preparation of Sample Extract

2.6. In-Vitro Cytotoxicity

2.7. In-Vitro Validation by Reverse Transcription Polymerase Chain Reaction (RT-PCR)

2.8. Real-Time Quantitative Reverse Transcription PCR (qRT-PCR) Assay Validation

2.9. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

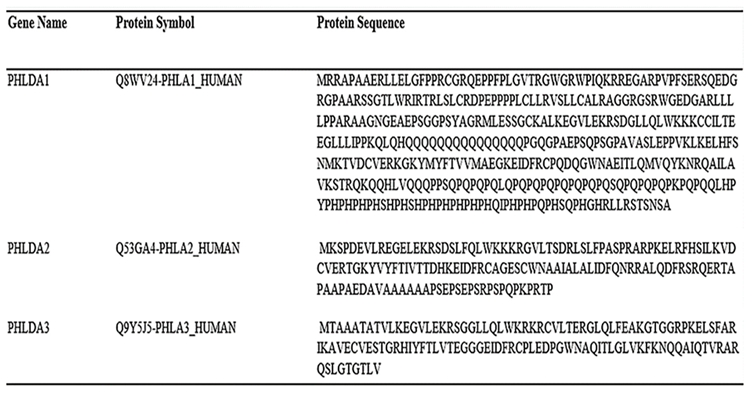

3.1. Disease and Gene Targets from the Previous Study

3.2. Investigation of Free-Binding Energy of CK and PHLDA Gene Family

3.3. In-Silico Molecular Dynamic (MD) Simulation of CK and PHLDA Gene Family

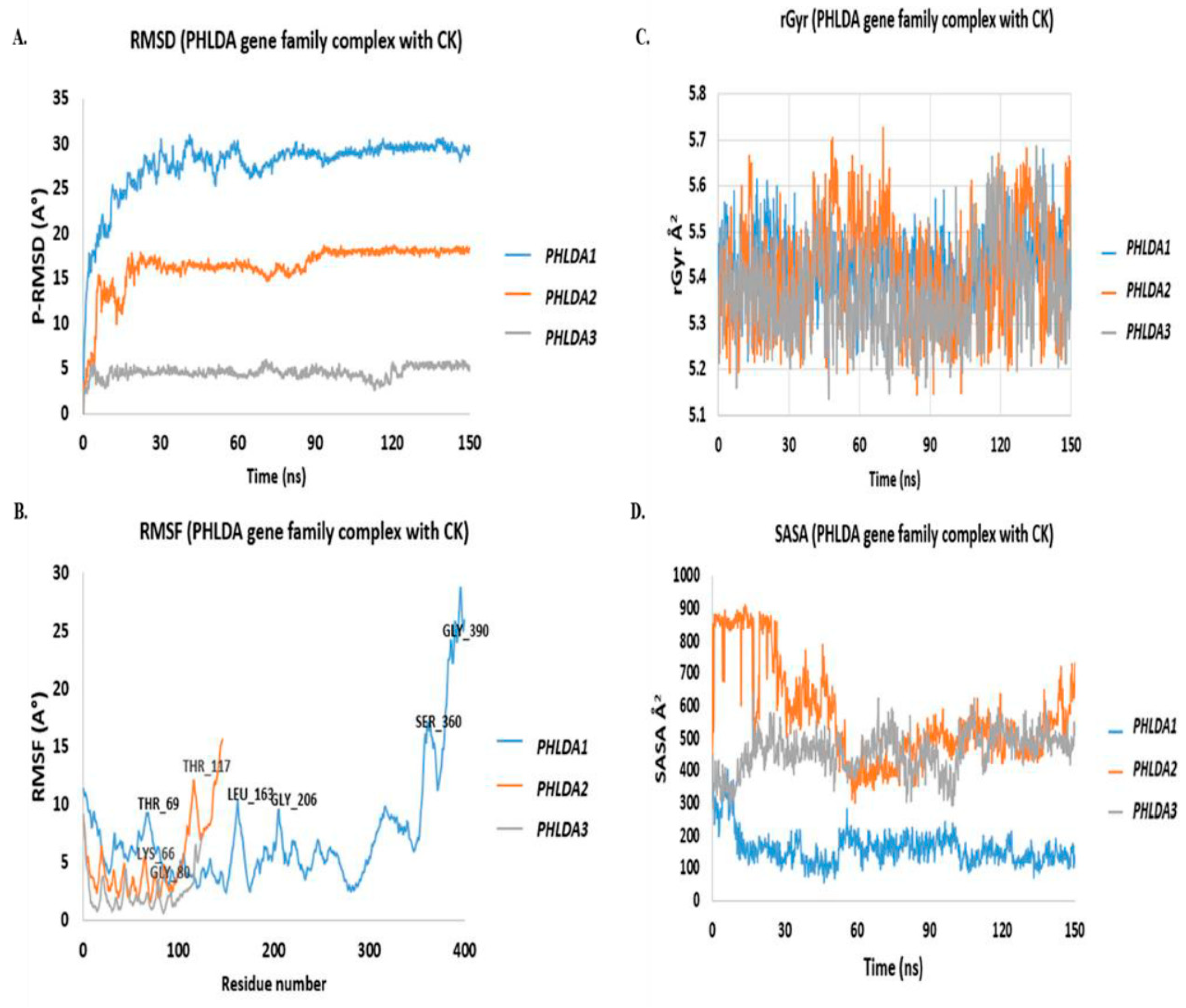

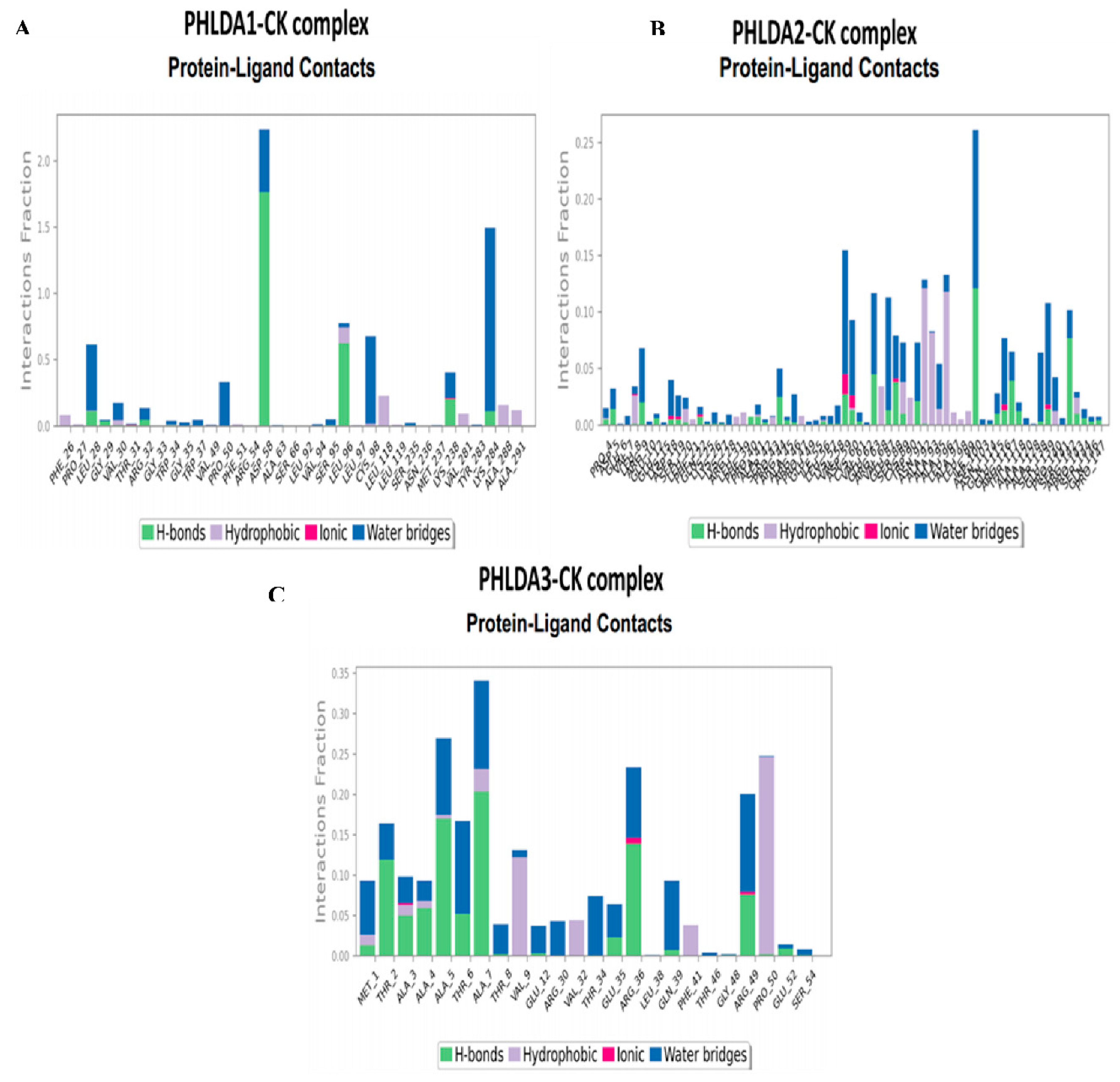

3.4. In-Vitro Cytotoxic Effect of G-CK

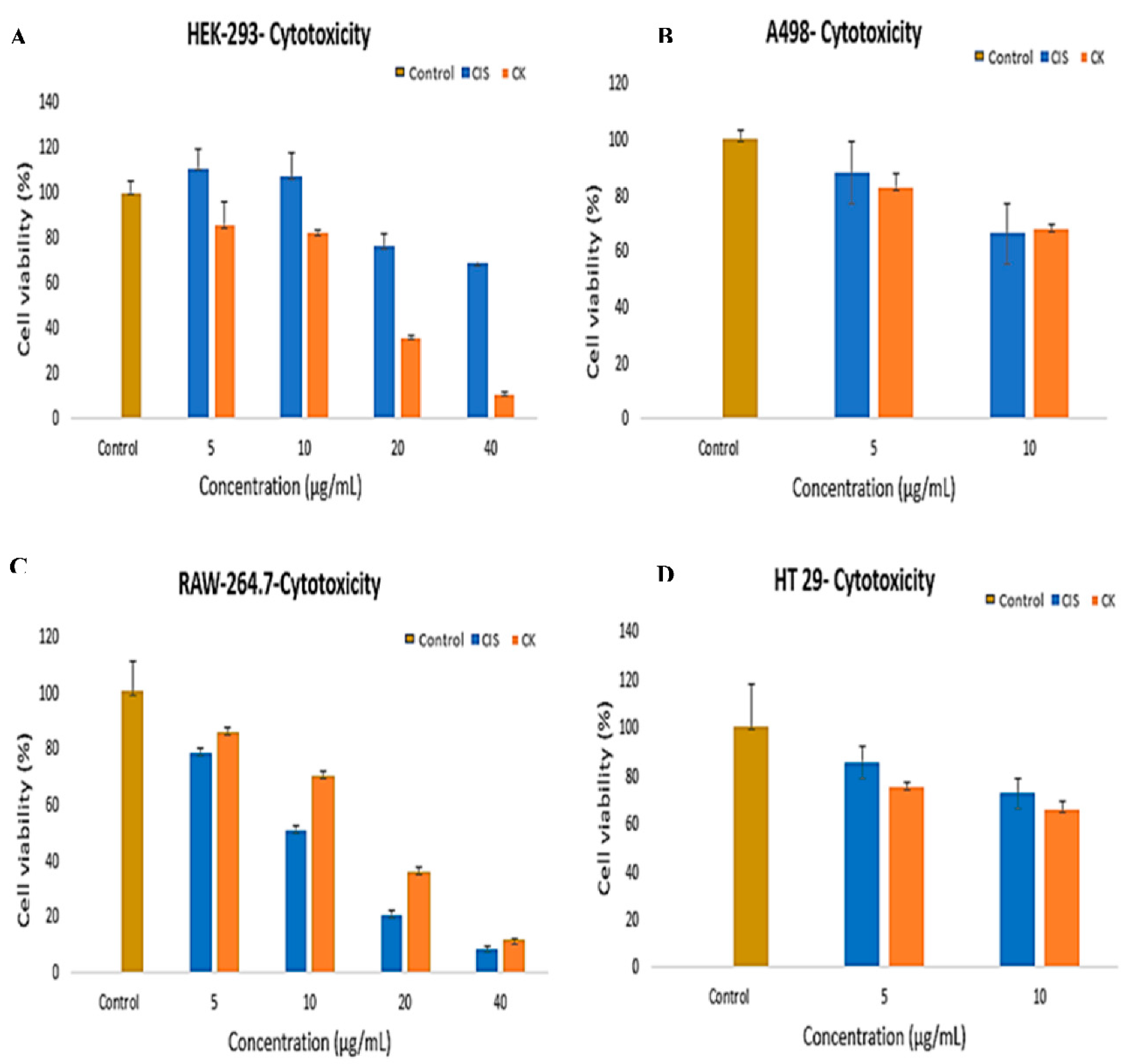

3.5. G-CK Controls the Gene Expression of the PHLDA Gene Family

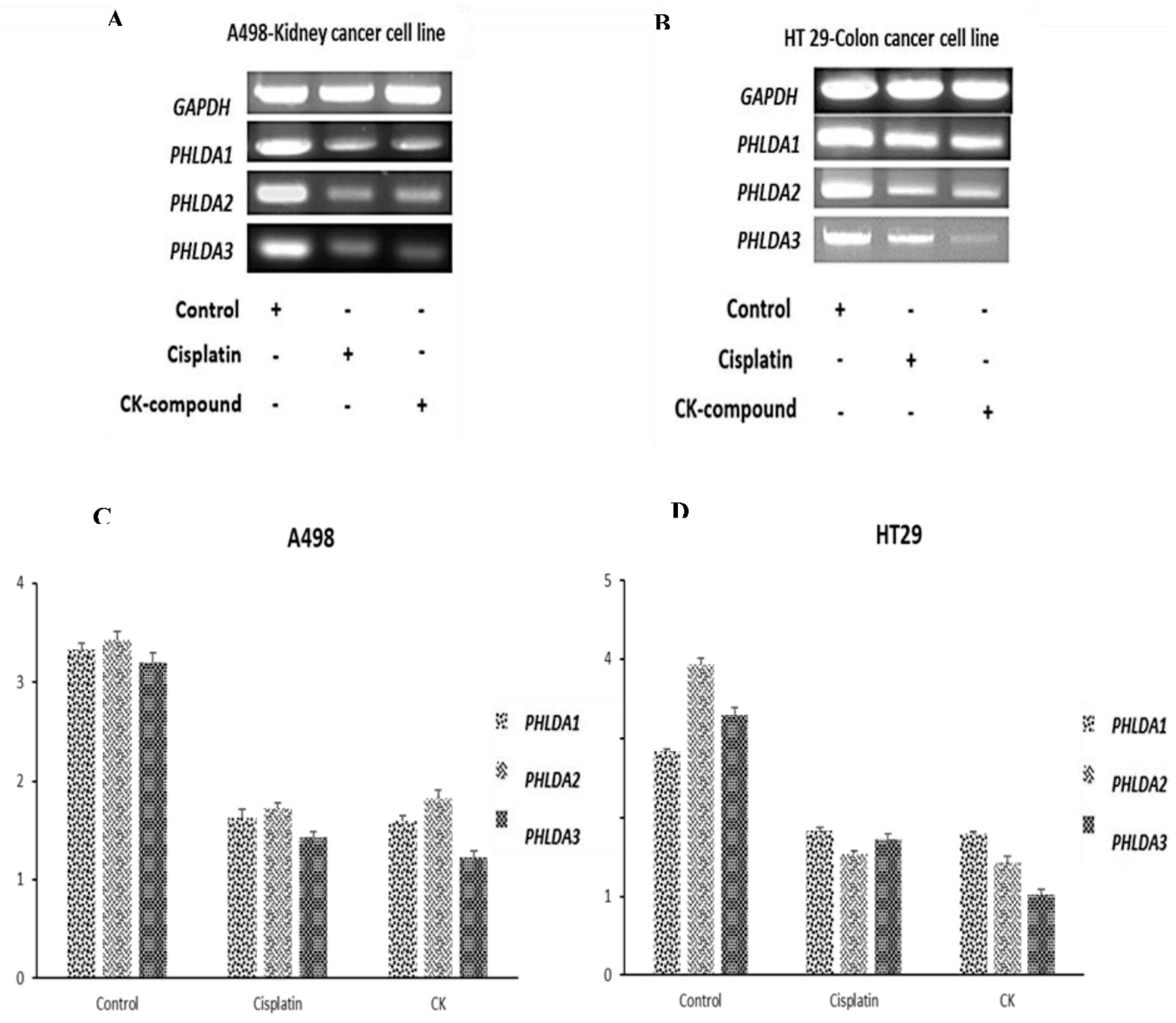

4. Discussion

5. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Data archiving statement

Data availability

Competing Interest Declaration

References

- Iqbal, S.; Karim, M.R.; Mohammad, S.; Ahn, J.C.; Kariyarath Valappil, A.; Mathiyalagan, R.; Yang, D.-C.; Jung, D.-H.; Bae, H.; Yang, D.U. In Silico and In Vitro Study of Isoquercitrin against Kidney Cancer and Inflammation by Triggering Potential Gene Targets. Current Issues in Molecular Biology 2024, 46, 3328–3341. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, K.D.; Goding Sauer, A.; Ortiz, A.P.; Fedewa, S.A.; Pinheiro, P.S.; Tortolero-Luna, G.; Martinez-Tyson, D.; Jemal, A.; Siegel, R.L. Cancer Statistics for Hispanics/Latinos, 2018. CA Cancer J Clin 2018, 68, 425–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lotfollahzadeh, S.; Recio-Boiles, A.; Cagir, B. Colon Cancer. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing Copyright © 2024, StatPearls Publishing LLC.: Treasure Island (FL), 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Jung, D.H.; Nahar, J.; Mathiyalagan, R.; Rupa, E.J.; Ramadhania, Z.M.; Han, Y.; Yang, D.C.; Kang, S.C. A Focused Review on Molecular Signalling Mechanisms of Ginsenosides Anti-Lung Cancer and Anti-inflammatory Activities. Anticancer Agents Med Chem 2023, 23, 3–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, K.T. Botanical characteristics, pharmacological effects and medicinal components of Korean Panax ginseng C A Meyer. Acta Pharmacol Sin 2008, 29, 1109–1118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piao, X.M.; Huo, Y.; Kang, J.P.; Mathiyalagan, R.; Zhang, H.; Yang, D.U.; Kim, M.; Yang, D.C.; Kang, S.C.; Wang, Y.P. Diversity of Ginsenoside Profiles Produced by Various Processing Technologies. Molecules 2020, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nag, S.A.; Qin, J.J.; Wang, W.; Wang, M.H.; Wang, H.; Zhang, R. Ginsenosides as Anticancer Agents: In vitro and in vivo Activities, Structure-Activity Relationships, and Molecular Mechanisms of Action. Front Pharmacol 2012, 3, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Oliveira Zanuso, B.; de Oliveira Dos Santos, A.R.; Miola, V.F.B.; Guissoni Campos, L.M.; Spilla, C.S.G.; Barbalho, S.M. Panax ginseng and aging related disorders: A systematic review. Exp Gerontol 2022, 161, 111731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chae, S.; Kang, K.A.; Chang, W.Y.; Kim, M.J.; Lee, S.J.; Lee, Y.S.; Kim, H.S.; Kim, D.H.; Hyun, J.W. Effect of compound K, a metabolite of ginseng saponin, combined with gamma-ray radiation in human lung cancer cells in vitro and in vivo. J Agric Food Chem 2009, 57, 5777–5782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Kim, N.; Jeong, J.; Lee, S.; Kim, W.; Ko, S.-G.; Kim, B. Anti-Cancer Effect of Panax Ginseng and Its Metabolites: From Traditional Medicine to Modern Drug Discovery. Processes 2021, 9, 1344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iqbal, S.; Karim, M.R.; Mohammad, S.; Mathiyalagan, R.; Morshed, M.N.; Yang, D.-C.; Bae, H.; Rupa, E.J.; Yang, D.U. Multiomics Analysis of the PHLDA Gene Family in Different Cancers and Their Clinical Prognostic Value. Current Issues in Molecular Biology 2024, 46, 5488–5510. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, L.; Chen, L.; Zeng, X.; Liao, J.; Ouyang, D. Ginsenoside compound K alleviates sodium valproate-induced hepatotoxicity in rats via antioxidant effect, regulation of peroxisome pathway and iron homeostasis. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 2020, 386, 114829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christensen, L.P. Ginsenosides chemistry, biosynthesis, analysis, and potential health effects. Adv Food Nutr Res 2009, 55, 1–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boopathi, V.; Nahar, J.; Murugesan, M.; Subramaniyam, S.; Kong, B.M.; Choi, S.K.; Lee, C.S.; Ling, L.; Yang, D.U.; Yang, D.C.; et al. In silico and in vitro inhibition of host-based viral entry targets and cytokine storm in COVID-19 by ginsenoside compound K. Heliyon 2023, 9, e19341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murugesan, M.; Mathiyalagan, R.; Boopathi, V.; Kong, B.M.; Choi, S.-K.; Lee, C.-S.; Yang, D.C.; Kang, S.C.; Thambi, T. Production of Minor Ginsenoside CK from Major Ginsenosides by Biotransformation and Its Advances in Targeted Delivery to Tumor Tissues Using Nanoformulations. Nanomaterials 2022, 12, 3427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, Y.; Du, Y.; Gu, Z.; Zheng, X.; Wang, C. Prognostic Value, Immune Signature, and Molecular Mechanisms of the PHLDA Family in Pancreatic Adenocarcinoma. Int J Mol Sci 2022, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakthianandeswaren, A.; Christie, M.; D'Andreti, C.; Tsui, C.; Jorissen, R.N.; Li, S.; Fleming, N.I.; Gibbs, P.; Lipton, L.; Malaterre, J.; et al. PHLDA1 expression marks the putative epithelial stem cells and contributes to intestinal tumorigenesis. Cancer Res 2011, 71, 3709–3719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMinn, J.; Wei, M.; Schupf, N.; Cusmai, J.; Johnson, E.B.; Smith, A.C.; Weksberg, R.; Thaker, H.M.; Tycko, B. Unbalanced placental expression of imprinted genes in human intrauterine growth restriction. Placenta 2006, 27, 540–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, H.G.; Oh, K.; Lee, J.; Lee, M.; Kim, J.Y.; Yoo, T.K.; Seo, M.W.; Park, A.K.; Ryu, H.S.; Jung, E.J.; et al. Prognostic and functional importance of the engraftment-associated genes in the patient-derived xenograft models of triple-negative breast cancers. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2015, 154, 13–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salmanli, M.; Tatar Yilmaz, G.; Tuzuner, T. Investigation of the antimicrobial activities of various antimicrobial agents on Streptococcus Mutans Sortase A through computer-aided drug design (CADD) approaches. Comput Methods Programs Biomed 2021, 212, 106454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, G.M.; Huey, R.; Lindstrom, W.; Sanner, M.F.; Belew, R.K.; Goodsell, D.S.; Olson, A.J. AutoDock4 and AutoDockTools4: Automated docking with selective receptor flexibility. J Comput Chem 2009, 30, 2785–2791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guex, N.; Peitsch, M.C.; Schwede, T. Automated comparative protein structure modeling with SWISS-MODEL and Swiss-PdbViewer: a historical perspective. Electrophoresis 2009, 30 Suppl 1, S162–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramachandran, G.N.; Ramakrishnan, C.; Sasisekharan, V. Stereochemistry of polypeptide chain configurations. J Mol Biol 1963, 7, 95–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Liu, X.; Zhou, W.; Cheng, G.; Wu, J.; Guo, S.; Jia, S.; Liu, Y.; Li, B.; Zhang, X.; et al. A bioinformatics investigation into molecular mechanism of Yinzhihuang granules for treating hepatitis B by network pharmacology and molecular docking verification. Sci Rep 2020, 10, 11448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, W.; Chen, C.; Lei, X.; Zhao, J.; Liang, J. CASTp 3.0: computed atlas of surface topography of proteins. Nucleic Acids Res 2018, 46, W363–w367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kemmish, H.; Fasnacht, M.; Yan, L. Fully automated antibody structure prediction using BIOVIA tools: Validation study. PLoS One 2017, 12, e0177923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dallakyan, S.; Olson, A.J. Small-molecule library screening by docking with PyRx. Methods Mol Biol 2015, 1263, 243–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, G.; Soufan, O.; Ewald, J.; Hancock, R.E.W.; Basu, N.; Xia, J. NetworkAnalyst 3.0: a visual analytics platform for comprehensive gene expression profiling and meta-analysis. Nucleic Acids Res 2019, 47, W234–w241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trott, O.; Olson, A.J. AutoDock Vina: improving the speed and accuracy of docking with a new scoring function, efficient optimization, and multithreading. J Comput Chem 2010, 31, 455–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rupa, E.J.; Arunkumar, L.; Han, Y.; Kang, J.P.; Ahn, J.C.; Jung, S.K.; Kim, M.; Kim, J.Y.; Yang, D.C.; Lee, G.J. Dendropanax Morbifera Extract-Mediated ZnO Nanoparticles Loaded with Indole-3-Carbinol for Enhancement of Anticancer Efficacy in the A549 Human Lung Carcinoma Cell Line. Materials (Basel) 2020, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iqbal, S.; Karim, M.R.; Mohammad, S.; Mathiyalagan, R.; Morshed, M.N.; Yang, D.C.; Bae, H.; Rupa, E.J.; Yang, D.U. Multiomics Analysis of the PHLDA Gene Family in Different Cancers and Their Clinical Prognostic Value. Curr Issues Mol Biol 2024, 46, 5488–5510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.-P.; Shao, L.; Wang, L.; Chen, M.-Y.; Zhang, W.; Huang, W.-H. Bioconversion variation of ginsenoside CK mediated by human gut microbiota from healthy volunteers and colorectal cancer patients. Chinese Medicine 2021, 16, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Ye, H.; Gong, F.; Mao, S.; Li, C.; Xu, B.; Ren, Y.; Yu, R. Ginsenoside compound K exerts antitumour effects in renal cell carcinoma via regulation of ROS and lncRNA THOR. Oncol Rep 2021, 45, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahdavi, M.; Fattahi, A.; Tajkhorshid, E.; Nouranian, S. Molecular Insights into the Loading and Dynamics of Doxorubicin on PEGylated Graphene Oxide Nanocarriers. ACS Appl Bio Mater 2020, 3, 1354–1363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, Y.; Meng, X.; Sun, K.; Zhao, M.; Liu, X.; Yang, T.; Zhang, Z.; Su, R. Anti-cancer effects of ginsenoside CK on acute myeloid leukemia in vitro and in vivo. Heliyon 2022, 8, e12106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.; Li, Z.K.; Li, C.Y.; Liang, Y.Q.; Yang, F. Anticancer properties and pharmaceutical applications of ginsenoside compound K: A review. Chem Biol Drug Des 2022, 99, 286–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.F.; Wu, L.X.; Li, X.F.; Zhu, Y.C.; Wang, W.X.; Xu, C.W.; Huang, Z.Z.; Du, K.Q. Ginsenoside compound K inhibits growth of lung cancer cells via HIF-1α-mediated glucose metabolism. Cell Mol Biol (Noisy-le-grand) 2019, 65, 48–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, H.; Wan, J.Y.; Zeng, J.; Huang, W.H.; Sava-Segal, C.; Li, L.; Niu, X.; Wang, Q.; Wang, C.Z.; Yuan, C.S. Effects of compound K, an enteric microbiome metabolite of ginseng, in the treatment of inflammation associated colon cancer. Oncol Lett 2018, 15, 8339–8348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.Z.; Anderson, S.; Du, W.; He, T.C.; Yuan, C.S. Red ginseng and cancer treatment. Chin J Nat Med 2016, 14, 7–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padala, S.A.; Barsouk, A.; Thandra, K.C.; Saginala, K.; Mohammed, A.; Vakiti, A.; Rawla, P.; Barsouk, A. Epidemiology of Renal Cell Carcinoma. World J Oncol 2020, 11, 79–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maher, E.R. Hereditary renal cell carcinoma syndromes: diagnosis, surveillance and management. World J Urol 2018, 36, 1891–1898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baral, K.C.; Bajracharya, R.; Lee, S.H.; Han, H.K. Advancements in the Pharmaceutical Applications of Probiotics: Dosage Forms and Formulation Technology. Int J Nanomedicine 2021, 16, 7535–7556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, Z.; Lou, S.; Jiang, Z. PHLDA2 regulates EMT and autophagy in colorectal cancer via the PI3K/AKT signaling pathway. Aging (Albany NY) 2020, 12, 7985–8000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Idichi, T.; Seki, N.; Kurahara, H.; Fukuhisa, H.; Toda, H.; Shimonosono, M.; Okato, A.; Arai, T.; Kita, Y.; Mataki, Y.; et al. Molecular pathogenesis of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma: Impact of passenger strand of pre-miR-148a on gene regulation. Cancer Sci 2018, 109, 2013–2026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.G.; Kang, Y.J.; Kim, H.S.; Moon, A.; Kim, S.G. Phlda3, a urine-detectable protein, causes p53 accumulation in renal tubular cells injured by cisplatin. Cell Biol Toxicol 2015, 31, 121–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Ohki, R. p53-PHLDA3-Akt Network: The Key Regulators of Neuroendocrine Tumorigenesis. Int J Mol Sci 2020, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Wang, Y.; Yu, Z.; Lv, G.; Huang, X.; Lin, H.; Ma, C.; Lin, Z.; Qu, P. Functional Mechanism of Ginsenoside Compound K on Tumor Growth and Metastasis. Integr Cancer Ther 2022, 21, 15347354221101203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baildya, N.; Khan, A.A.; Ghosh, N.N.; Dutta, T.; Chattopadhyay, A.P. Screening of potential drug from Azadirachta Indica (Neem) extracts for SARS-CoV-2: An insight from molecular docking and MD-simulation studies. J Mol Struct 2021, 1227, 129390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmud, S.; Rahman, E.; Nain, Z.; Billah, M.; Karmakar, S.; Mohanto, S.C.; Paul, G.K.; Amin, A.; Acharjee, U.K.; Saleh, M.A. Computational discovery of plant-based inhibitors against human carbonic anhydrase IX and molecular dynamics simulation. J Biomol Struct Dyn 2021, 39, 2754–2770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

| Targets | Compound | Binding Energy | Hydrogen bond | Other bonds | Grid Box Center | Dimension |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PHLDA1 | Compound K (CK) | -6.9 | SER235, GLY29 | TYR283. GLN287, ALA288, LEU 28, PRO27, VAL30, ASN285, PHE26 | x=1.662, y=-2.6093, Z= 4.3494 |

x=149.63, y=121.75, Z= 104.54 |

| Control (Levofloxacin) | -5.7 | ASP263 | GLN165, TRP167, ARG159, VAL243, GLU244, TYR251, LYS246 | x=1.662, y=-2.6093, Z= -4.3494 |

x=149.63, y=121.75, Z= 104.54 |

|

| PHLDA2 | Compound K (CK) | -7.3 | GLU12, ARG28, LYS26, PRO40 | LYS27, ALA41, LYS26, PHE39, PRO43, SER42, ARG44, PRO47, ALA45, ARG46 | x=-4.233, y=-2.692, Z= 5.189 |

x=89.71, y=47.33, Z= 78.76 |

| Control (Levofloxacin) | -5.7 | ARG16, ASP81 | GLU79,LYS15, ILE80, SER17, ASP18, LEU20, GLN22,SER19 | x=-12.82, y=-4.747, Z= 12.03 |

x=106.89, y=51.43, Z= 92.43 |

|

| PHLDA3 | Compound K (CK) | -6.8 | GLU52 | ARG36, THR34, VAL32, VAL9, ALA7, GLN39, PRO50, PHE41, ARG30, GLY48. GLY47, THR46, THR6 | x=-0.369, y=0.114, Z= 4.93 |

x=52.379, y=38.433, Z= 58.078 |

| Control (Levofloxacin) | -6.0 | TRP26. CYS63 | ARG18, ASP84, PHE73, GLU65, ARG86, THR67 | x=-4.17, y=0.114, Z= 8.49 |

x=59.98, y=38.43, Z= 65.20 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).