1. Introduction

For power generation and propulsion, combustion of gaseous or liquid fuels in gas turbine engine combustors will remain important for decades to come in view of the high efficiency and power density. In the path of transition to sustainable fuels, methane and Diesel/Kerosene/jet fuel will be replaced by hydrogen, ammonia and Sustainable Aviation Fuel. The challenges related to their combustion will however remain. The emission of nitric oxides will still be an issue and the drive to reduce them will continue. This is laid down in the Paris agreement in 2015 [

1]. In addition, the necessity to reduce and control thermoacoustic oscillations has to be faced as well. A method that was proven to be successful in the past for natural gas to reach this low NOx emission target, is lean premixed combustion. If this concept will be an option with new sustainable fuels remains to be seen. But for all fuels the occurrence of thermoacoustic instabilities in lean premixed combustion has to be reckoned with. This paper presents a method to analyze and predict the onset to instability and predict a likely growth of amplitudes. This is done for premixed methane combustion with the option to generalize this to other combustion concepts.

The flame in the combustor is a powerful thermoacoustic monopole source that can drive the acoustics in the combustor into a high amplitude limit cycle oscillation. This can lead to destructive processes in the engine [

2]. Being able to predict and understand these instabilities is a continuous challenge that calls for experimental work on combustion systems that are representative for gas turbine engine combustion chambers. The aim is to develop effective post processing concepts of the data allowing predictive methodologies to avoid thermoacoustic instabilities [

3].

In experimental work, the so-called data driven approach, a nonlinear time series analysis to study thermoacoustic instabilities has been presented in the works of Gotoda et al. [

4] and more recently by [

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11]. They have pioneered in the nonlinear analysis of laboratory scale combustors, mostly with laminar flow.

Studied were the high amplitude oscillations and how the system goes from chaotic to non-chaotic behaviour. It was shown how to identify and make a clean distinction of the stages at which the combustor behaviour changes. This can be when the composition of the fuel, the position of the flame or the air to fuel ratio varies for a certain combustor. Most of the nonlinear analysis through three phase portraits has been done in the laminar regime, with operational air flows of Reynolds numbers of the order of 1000. More recently, [

9] and [

10] presented nonlinear analysis of the combustion dynamics of methane/hydrogen mixtures. [

9] worked at leaner conditions and Reynolds numbers of 19000, air to fuel equivalence ratio of 1.8 and increasing the percentage of methane. The change from stable to limit cycle oscillations occurs as methane is more prominent in the mass fraction. A property of a deterministic system is that its evolution is fully determined but its predictability is limited by the exponential growth of errors on the measurements [

12]. Prediction of a chaotic time series can be approximated by the nonlinear functional mapping of the signal. This is by far not a new idea, as the initial chaotic time series prediction take us back to 1987, where it was already known that chaotic fluids flows can generate state spaces onto an attractor of a few dimensions [

13]. However, computational power and developments in the artificial intelligence umbrella have now opened a world of possibilities to process experimental nonlinear data and make predictions with it.

The present study aims at nonlinear treatment of pressure and OH-chemiluminescence time series retrieved from the combustor with two different geometries. The data in the time series is based on data from multiple wall mounted pressure transducers and data from a photo multiplier tube. The thermoacoustic system, composed of the combustion chamber and the flame are viewed as a black box. From the obtained time series, with the methodology introduced by Abarbanel [

14], three-phase portraits are obtained, based on the computed system delay time and global embedding dimension [

15]. The phase portraits were obtained for a variation of the operating parameters, where the system evolved from stable/chaotic to deterministic/unstable and back. The transition from chaotic to deterministic was observed by means of the 0-1 test. For all operating conditions, the fractal dimension of the phase portraits was established and the predictive capabilities for thermoacoustic oscillations analyzed. This was all done for a high Reynolds number flow with the combustion flow well in the turbulent regime. The present paper is organized as follows: In

Section 2. Methodology and Experimental Set Up the applied methodology is introduced as well as the combustion system on which this was applied. The combustion system delivered for varied operating conditions data in terms of pressure transducer and photomultiplier time series. The behaviour of the combustion system shows a bifurcation in the transition from stable to unstable operation. This is presented in

Section 3. Analysis of Optics and Pressure Data. The nonlinear behaviour of the combustion dynamics is analyzed by means of a phase space construction in

Section 4. Nonlinear Analysis. In

Section 5.Test 0-1 for Chaos is investigated if the transition from stable combustion dynamics with small growth rate to limit cycle oscillations is related to a switch from chaotic to deterministic behaviour. Explored is if this can be used to predict the onset of limit cycle oscillations. Finally in

Section 6. Conclusions conclusions and take away of the paper are summarized.

2. Methodology and Experimental Set Up

In this section first the followed methodology to investigate the nature of limit cycle oscillations is lined out. Subsequently the combustor that is used to provide the data is presented. Since this is about thermoacoustic oscillations, the data obtained are time series of pressure samples and photomultiplier samples. The target of this study was to explore the unstable behaviour of a combustor with a turbulent air inlet flow and turbulent flame. First the time series are observed using a conventional Fourier transformation to reveal the spectral content of the signals. The combustor can operate either in a stable or unstable mode, with a well reproduceable transition with a change in equivalence ratio. The oscillations amplitude distribution changes in a very characteristic way in the transition and this is analyzed. This transition of amplitude distribution can be mapped in a bifurcation diagram, revealing the change of the combustion oscillations behaviour.

More is to be learnt from the obtained data time series by more advanced data processing. To this end, a phase space reconstruction is made of the data to observe the possible motion of the system to a lower dimensional attractor. The presence of such an attractor would indicate chaotic system behaviour switching to deterministic. Therefore, for all operation conditions, the 0-1 test for chaos is performed and investigated if this will serve as a precursor for instability in this turbulent premixed combustor.

2.2. Experimental Setup

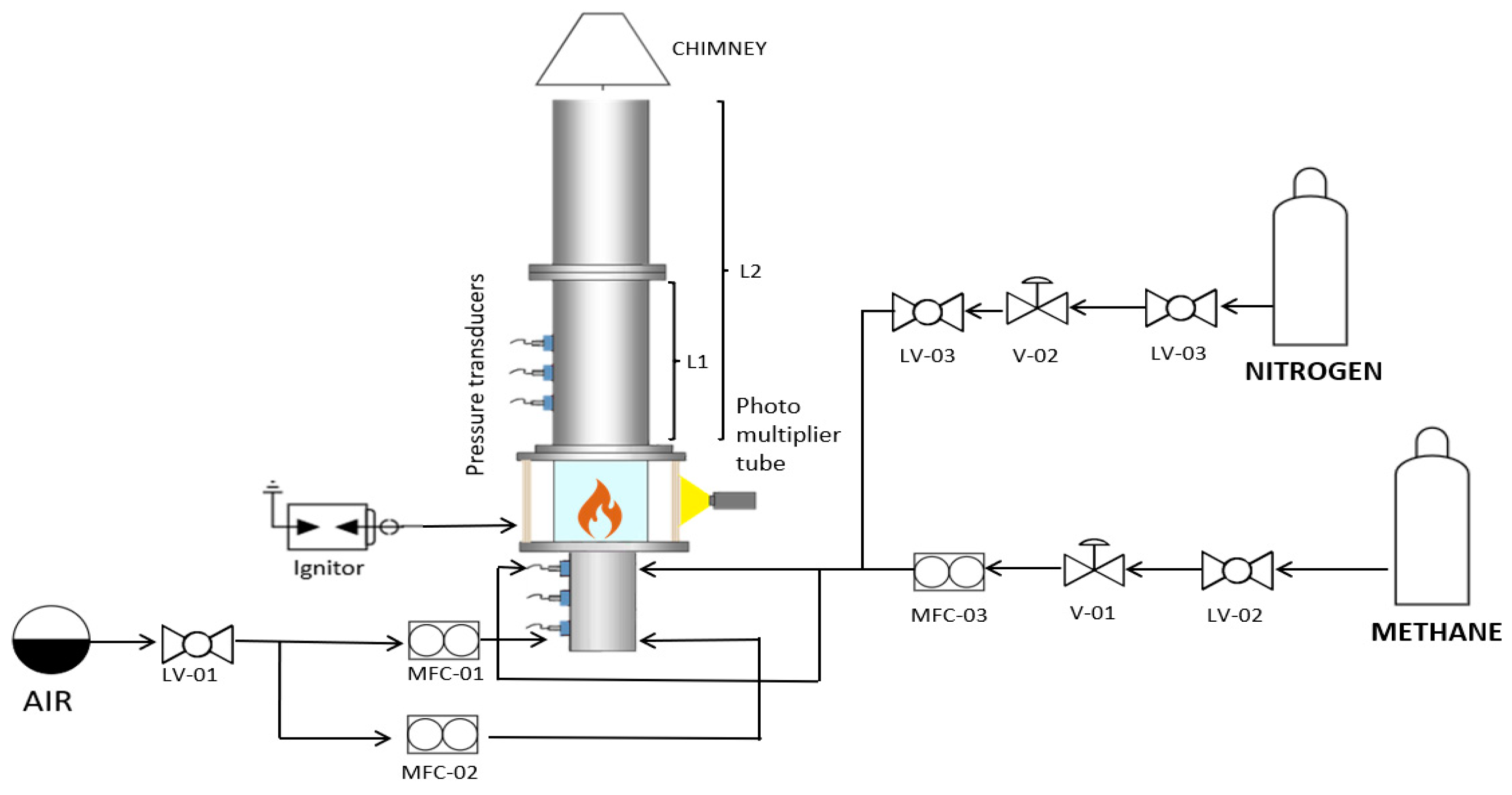

For the studies presented, an available combustion system was used. This was the combustor developed and built in the LIMOUSINE project.

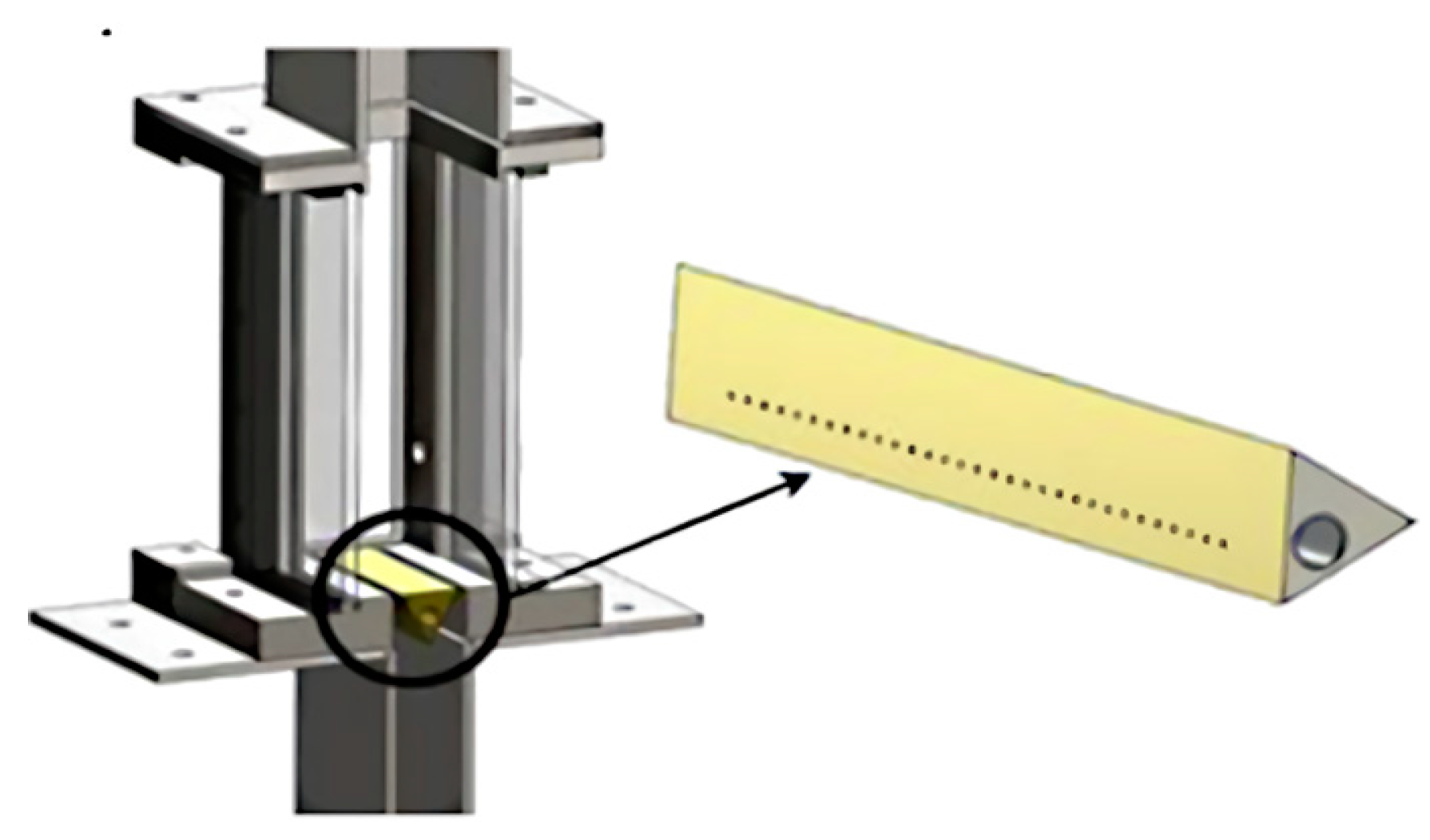

Figure 1 sketches the test rig lay-out and shows a detailed view of the burner geometry. This geometry consists of a triangular wedge holding the flame on the bluff body wake. The triangular wedge has a hollow body with 32 holes per face on both upstream directing faces. Through these holes, methane fuel, supplied from both ends of the wedge, is injected into the air flow. This combustor burns stable at lean fuel to air equivalence ratio but transists into limit cycle oscillation when the equivalence ratio is increased sufficiently close to stochiometric. The air to the burner is supplied in a plenum that opens via the wedge passage into the combustion chamber that has a larger width. Since the air flow past the wedge has a high turbulence intensity, the methane fuel injected mixes fast, leading to a premixed methane/air flow into the combustor from each side of the wedge. The turbulent flame stabilizes on the recirculation area crated by the boundary layer detachment at the two sharp downstream facing edges of the wedge. The plenum has a length of 275 mm with a cross-section of 25x150 mm2. (width x depth). The combustion chamber on top of the plenum has a length of 780 mm with a cross-section of 50x150 mm2 (width x depth, L1 in

Figure 1). The liner can be equipped with a liner extension that allows for an extra 610 mm of the combustor length (L2 in

Figure 1), giving an overall of 1610 mm full length. In the combustion chamber four quartz windows are placed starting at the wedge position to allow optical access of the flame from all sides.

2.3. Instrumentation and Data Acquisition

Acoustic data is collected by 6 Kulite XTE 190M wall mounted pressure transducers, 3 upstream and 3 downstream the burner. Four thermocouples are installed distributed over the length of the combustor. A Thorlabs PMM01 Photomultiplier Tube, with a band pass filter of 310 nm mounted, was used to acquire the OH* chemiluminescence of the flame.

The signals are measured by National Instruments cards and a LabVIEW data acquisition program. The DAQ system (NI 9239), can read ±10 V signals at a maximum sample rate of 50,000 Hz simultaneously in all the (12) input channels. In the research performed here for each test, 3.2 seconds of data were obtained at a sample rate of 10,000 Hz. These sample parameters were chosen such to be able to study pressure oscillations in the range of 50 to 800 Hz.

3. Analysis of Optics and Pressure Data

A series of experiments with lean combustion conditions is performed as follows, with the combustor at a nominal thermal power of 50 kW. The combustor is started near stoichiometric and subsequently the air flow is quickly increased to reach an air factor of 1.9. In that situation the combustion process is stable and low amplitude combustion noise is observed and driven by turbulence. Subsequently the air factor is decreased in steps of 0.1 (1.9 to 1.8 to 1.7…). After every stepwise change of the airflow, pressure measurements are performed after the thermoacoustic system has become stationary. The air factor is decreased till well beyond the point the thermoacoustic system has become unstable and developed at a high amplitude limit cycle oscillation. The lowest air factor reached is 1.2, where the combination of high flame temperature and high amplitude pressure oscillations has reached the limit that the combustor can sustain for a brief time without being damaged. Subsequently the process is reversed, and the path back to an air factor 1.9 is followed. This in order to detect a possible hysteresis in the nonlinear processes involved. The thermoacoustic system can switch between two characteristic states: stable low noise amplitude and limit cycle oscillation with high amplitude saturation.

3.1. For the L1 Case (Original Length)

An optical snapshot viewed from the side of the combustor of the stable and the unstable case can be seen in

Figure 3. For the air factor (λ) of 1.8 (left picture), it can be seen how the flame is totally divided in the two sides where the fuel holes are located. There is a long and thin flame that extend toward the optical window. On the right, we have an λ of 1.2, where we encountered limit cycle oscillations, shown as a compacted flame that anchors at the bluff body in its wake.

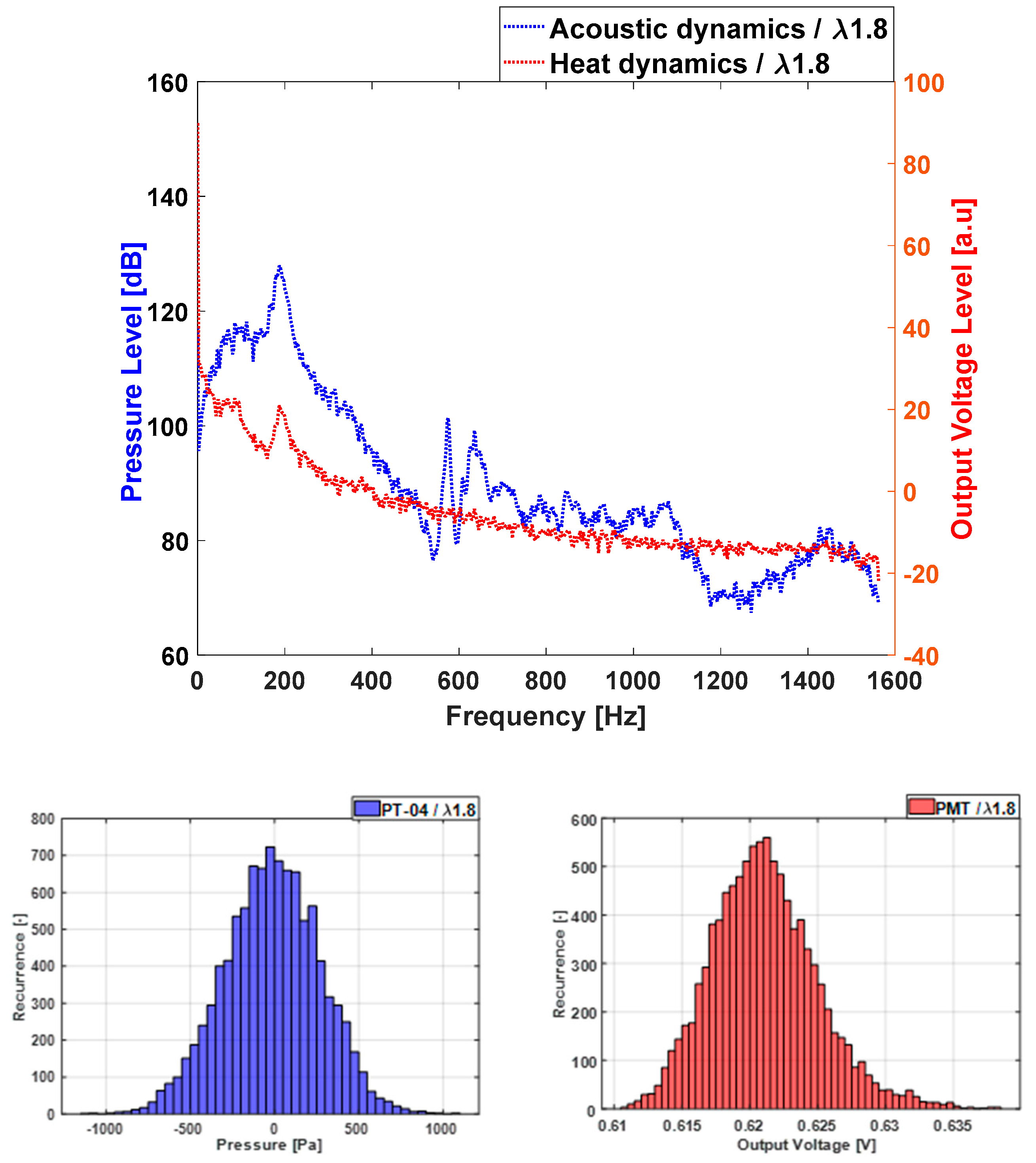

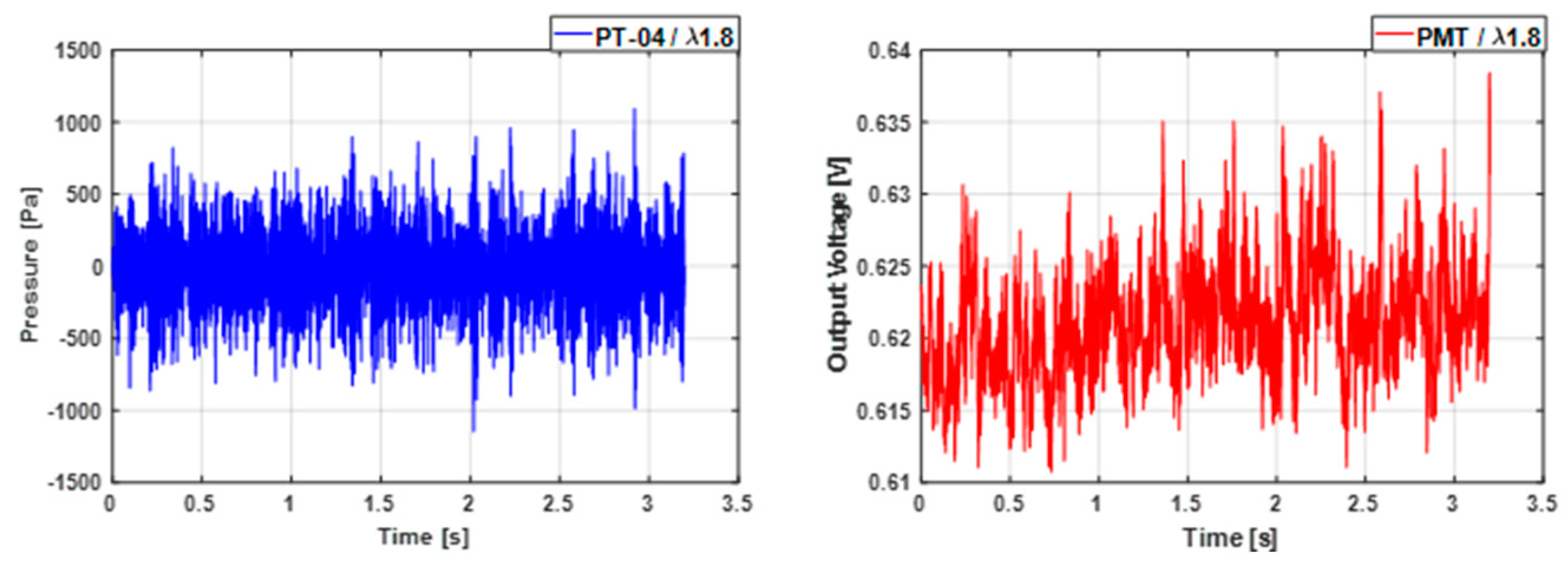

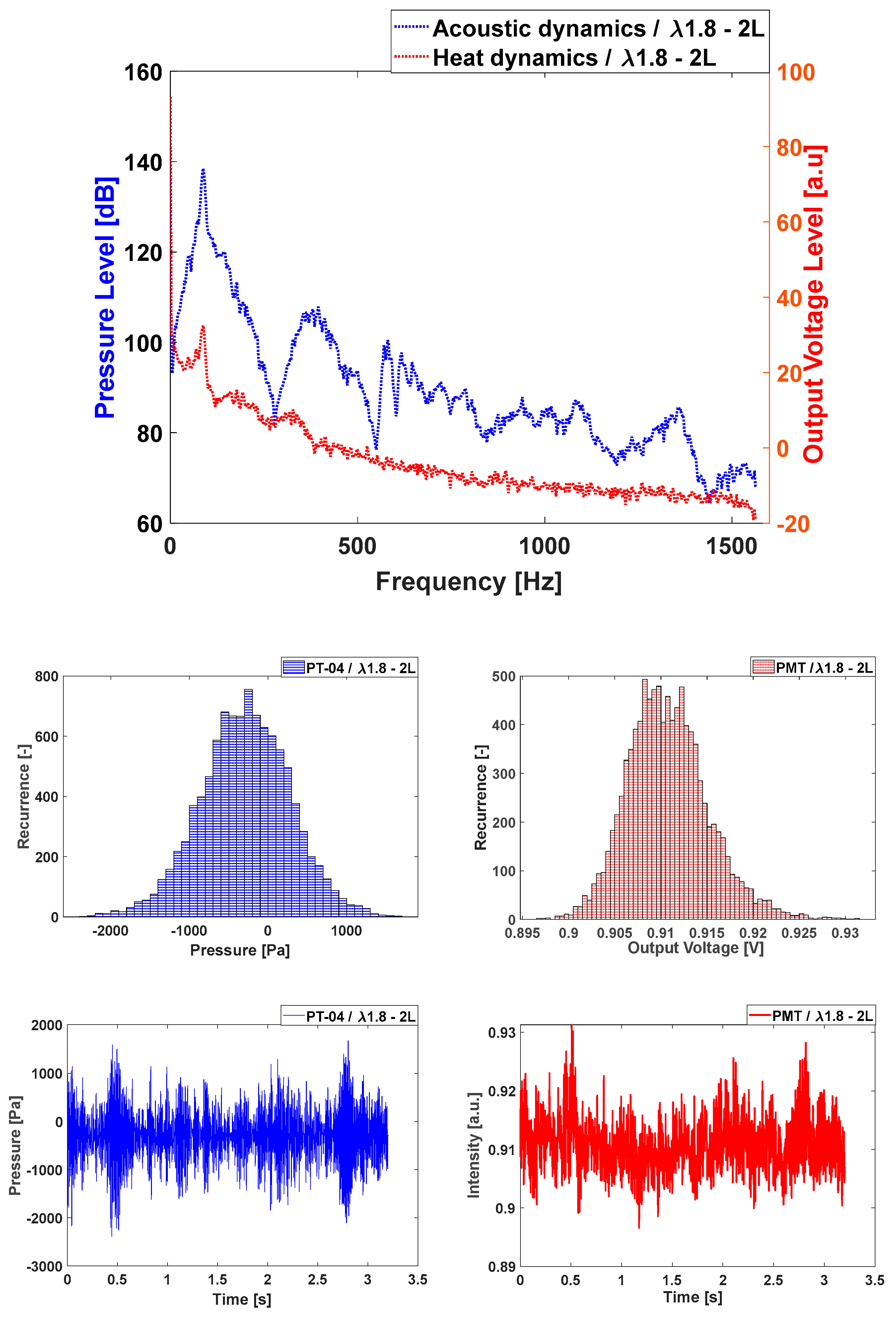

First take a look is taken at the stable case, being the one with higher air factor (λ=1.8).

Figure 4 shows the power spectrum in dB and related logarithmic units for both, the acoustics and the rate of heat release. On both spectra there are no resonant dominant frequencies observed. There is an increased activity (130 dB) in the range of 50 – 300 Hz for the acoustic signal. The higher frequency amplitudes are below 100 dB. The signal histogram (middle), that allows us to evaluate the amplitude distribution changes from a stable case to a transitional state and to an unstable situation. The time series (bottom) which for the case of the pressure is seen to heavily vary with time.

The stable mode pressure amplitude histogram at air factor 1.8 is observed to be a symmetric bell shape and symmetrically distributed on both sides of 0 amplitude with a maximum representation of low amplitudes and a decline of occurrence with increasing amplitude. The maximum amplitude with very low occurrence is 400 Pa. For the OH* chemiluminescence case, the intensity time series vary strongly with time and the histogram shows a bell shape distribution as well, balanced around mean chemiluminescence intensity, with its center slightly moved towards lower values.

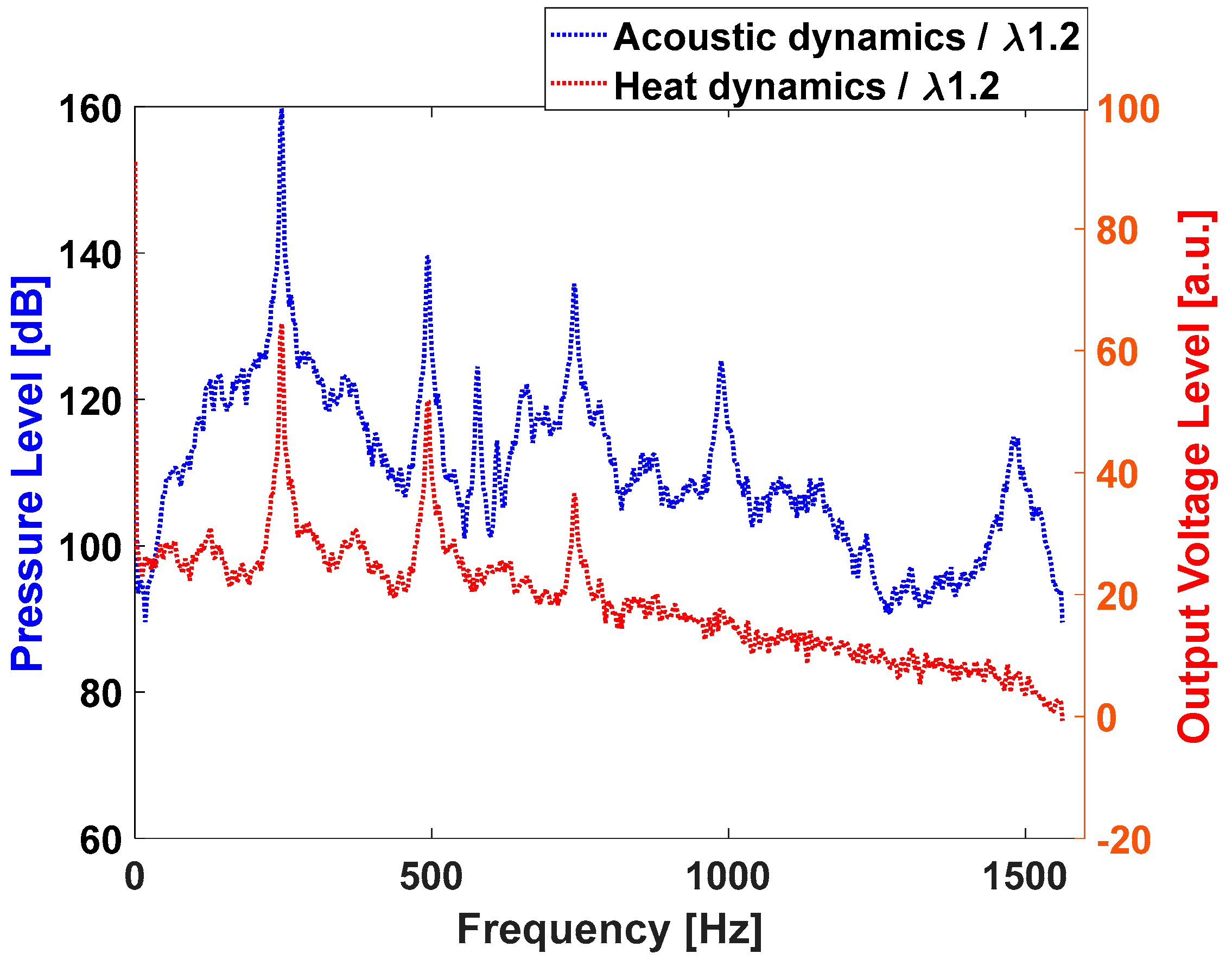

Figure 5 shows a representative measured pressure time series of the limit cycle oscillation state and the frequency spectrum at air factor 1.2. The pressure amplitude is quite high and constant with time and indicates a saturation of the process. The spectrum for pressure oscillations shows a dominant peak of 160 dB at a frequency of 240 Hz. At this frequency the PMT signal (rate of heat release) also shows a very high peak.

Regarding the signal histograms, in the limit cycle mode the amplitude distribution has become flat with a strong emphasis on the high amplitudes. It can be concluded that the pressure amplitude distribution changes in a very characteristic way in the path to switch to the unstable/limit cycle mode. Regarding the OH* chemiluminescence, we see higher and constant values and a saturated signal. Nevertheless, the histogram shows a distribution of the intensity values most concentrated in low values and then a decay and similar distribution for the higher intensities, with a slight peak around 0.83 (value as an arbitrary unit). and then a decrease. In the superposed spectra a number of very dominant resonant frequencies can be observed. A main resonant frequency appears around 240 Hz at 165 dB. The structural mode is also observed and at higher amplitude than in the stable mode (135 dB). Other resonant frequencies can be observed at 650 Hz, 800 Hz (140 dB) and 1400 Hz (120 dB). The characteristics of these two states and the system changes in the path for high to low air factor are explored next.

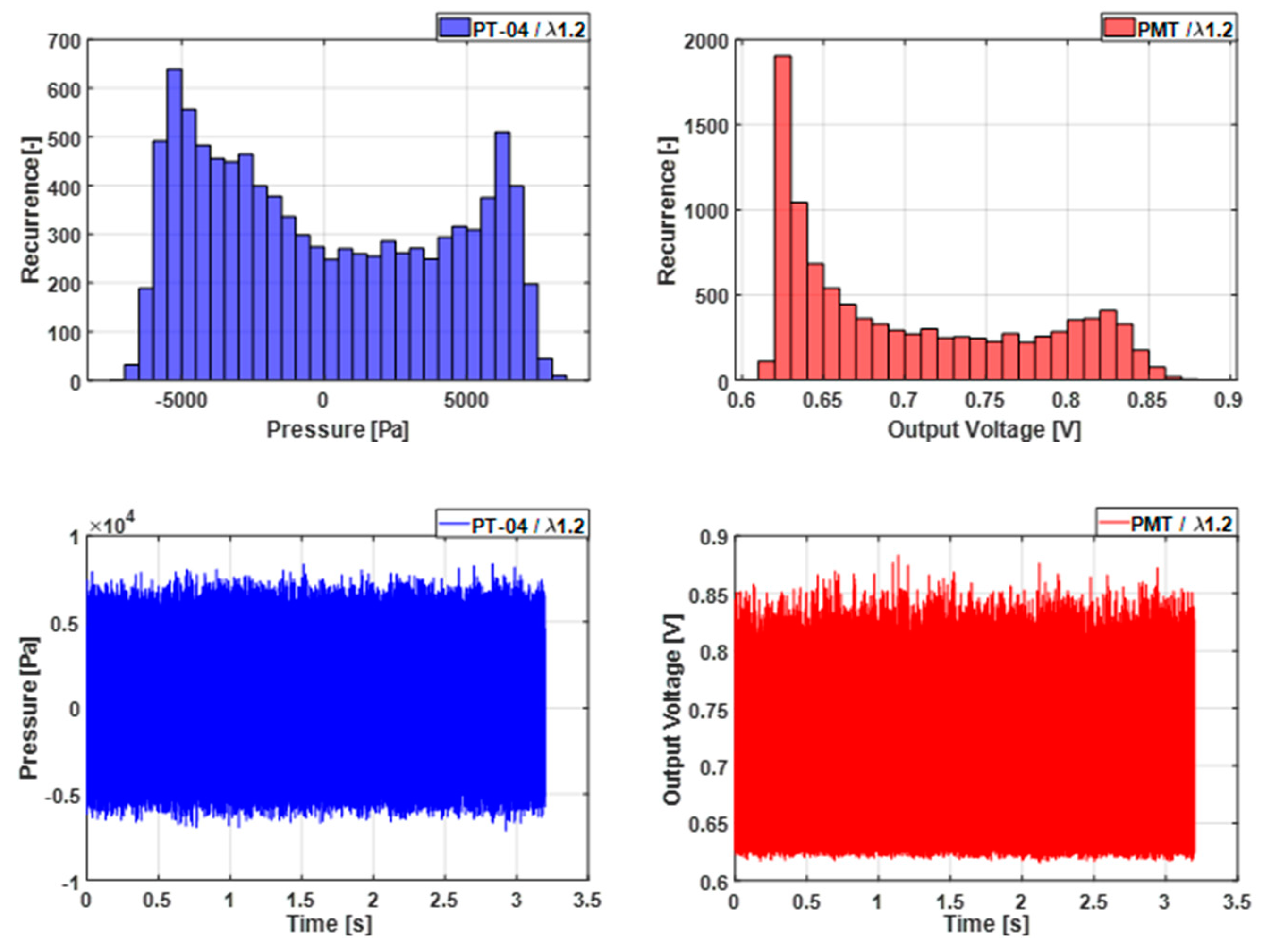

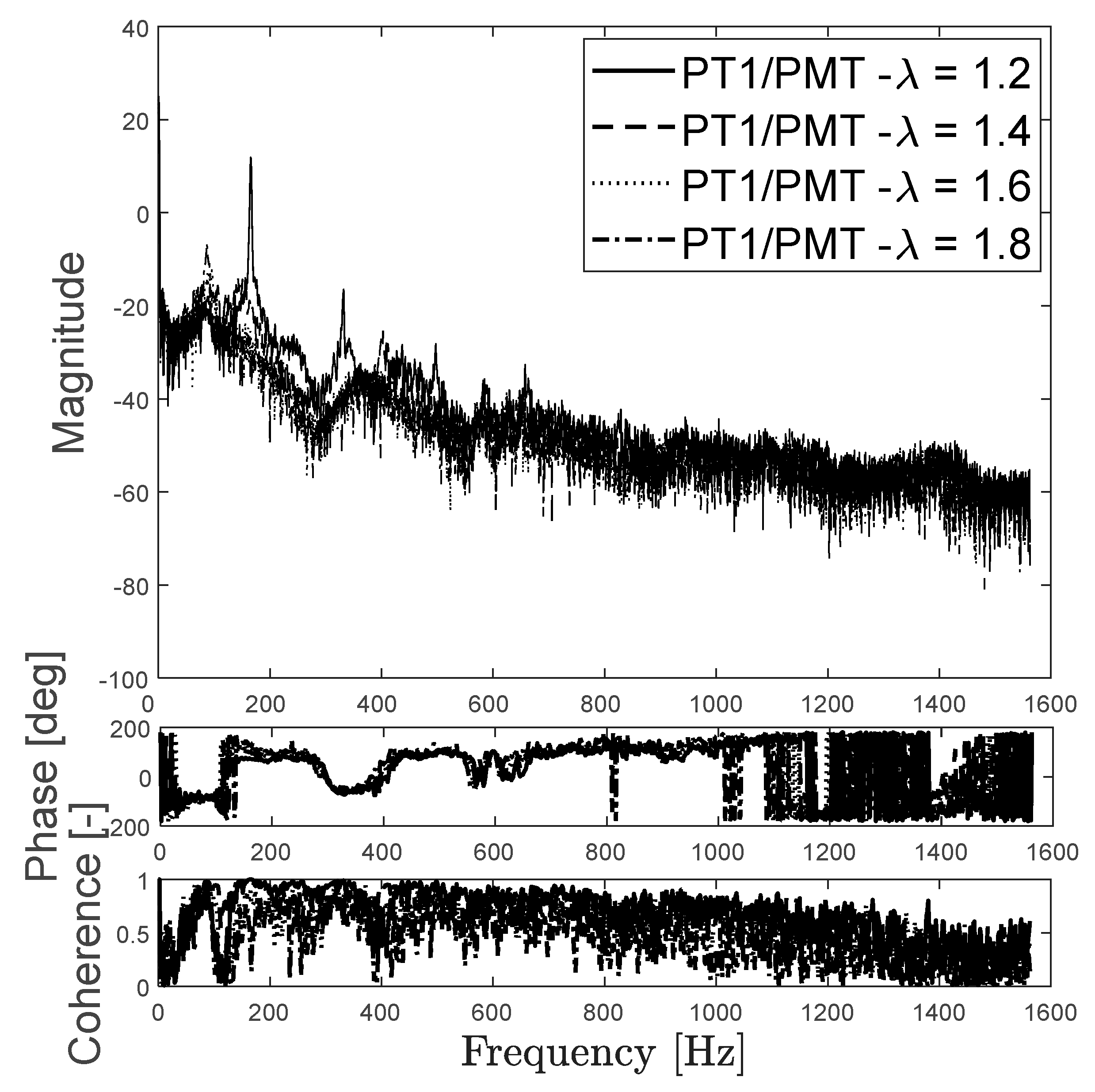

The cross-spectrum magnitude, phase and coherence of the oscillations of gauge pressure and rate of heat release (measured by the chemiluminescence signal), are presented in

Figure 6, for the cases of λ =1.8 (dash-dot),1.6 (dot),1.4 (dash) and 1.2 (solid line). It can be seen that the coherence in all cases remains high up to about 1400 Hz, indicating a coupling of acoustics and rate of heat release fluctuations. From this figure the peak magnitude location and its phase are observed to analyze the nature of the oscillations. The Rayleigh equation for thermoacoustic instability predicts, if the phase of the peak magnitude is in between -180 and 180 degrees, the rate of heat release fluctuations will amplify the pressure oscillations. In case the acoustic source term is larger than the damping and loss of acoustic energy the growth rate will be positive and a limit cycle may be reached. The two lean cases (λ =1.8,1.6) have a negative peak at 186 Hz for the first and 196 Hz for the second, both not significant and indicating that the signals are about 180 degrees out of phase. Hence the oscillatory growth rate is negative or near zero.

On the close to stoichiometric air factor 1.4 case, there are 3 prominent peaks, the first at 234 Hz and with a positive value, the next ones have a negative value and are located at 467 Hz and 705 Hz. For the λ =1.2 case, when the high amplitude oscillations are happening, the cross spectrum shows the first peak at 246 Hz and a positive value. This indicates (and shows in the phase diagram) a phase difference between acoustics and rate of heat release fluctuations of about 0 degrees. This confirms the Rayleigh prediction of a positive growth rate and limit cycle oscillation. The next two peaks are at 493 Hz, with positive value and 740 Hz on a remarkably close value of the amplitude. There is a lower peak at 989 Hz. The coherence has a value of 1 coincides with the more defined and larger in amplitude peaks.

3.2. For the L2 Case (Double Length)

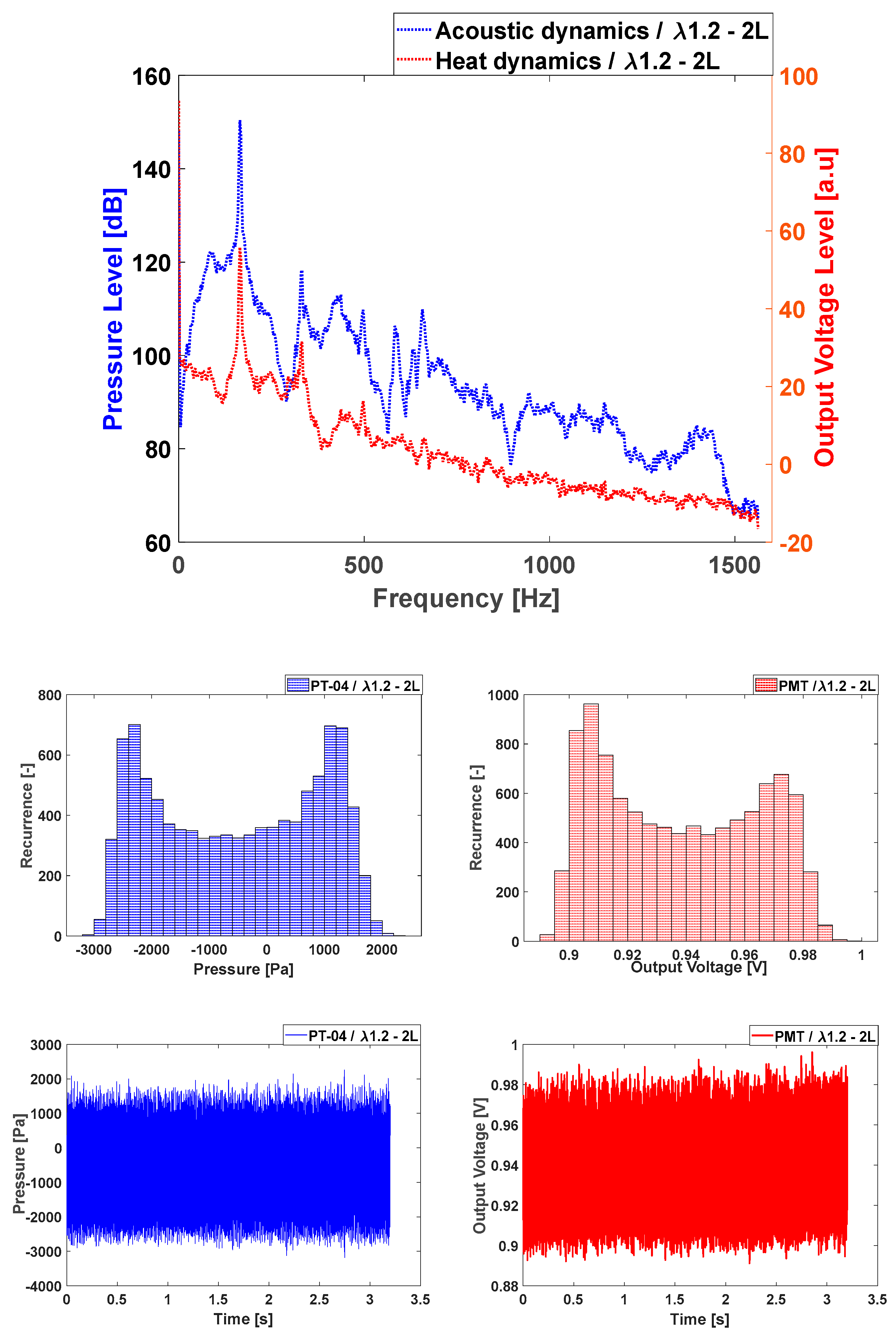

Subsequently experiments are performed with the same combustor but at double length downstream the burner deck, at a nominal power of 50 kW (0.99 g/s of methane) and the highest air fuel equivalence ratio before reaching the lean blow off. The experimental sequence was from λ= 1.8, 18.2 g/s of air, to λ= 1.2, 12.1 g/s of air, and back.

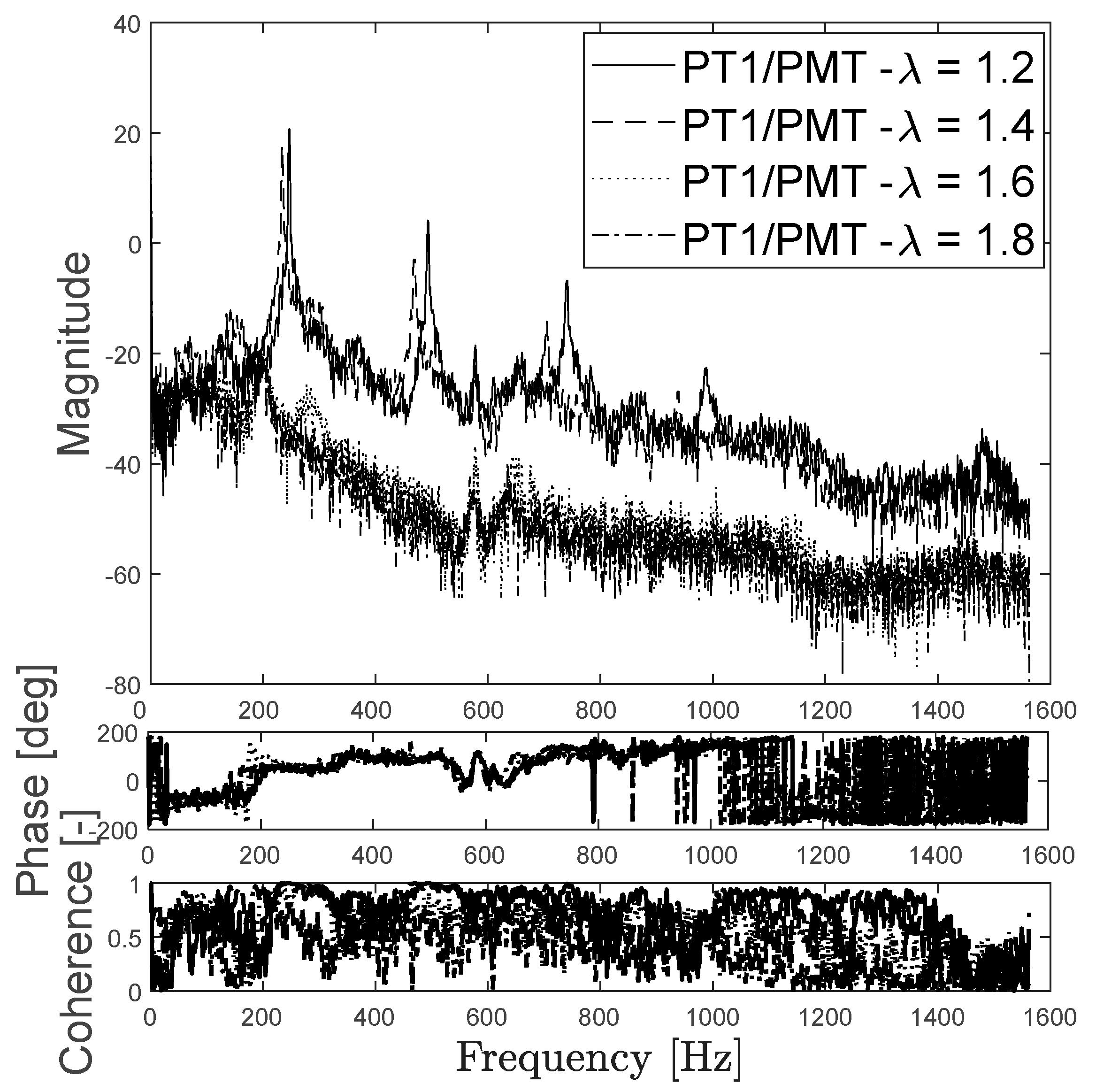

Figure 7 shows the pressure time series and the amplitude histogram for the stable case λ= 1.8. We again encounter a seemingly random varying pressure amplitude decreasing with frequency and a symmetrical gaussian shape for the amplitude distribution with most values concentrated in low amplitudes, of less than 500 Pa. For the case of the PTM signal, for which raw data is presented, we see a random changing signal that tends to decrease its mean value with frequency, behaviour that can be also appreciated in the amplitude distribution data histogram.

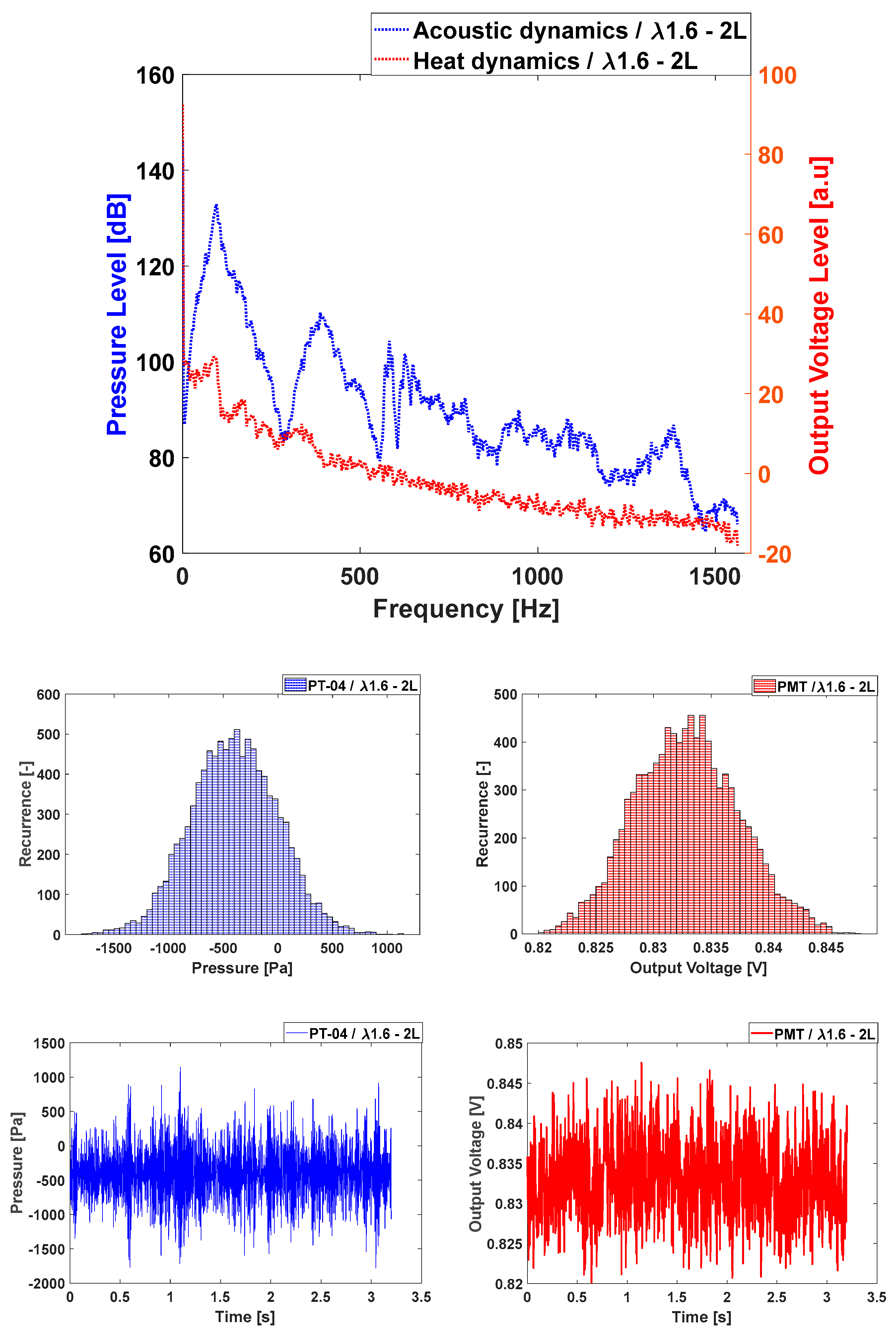

Figure 8 shows the pressure time series on an unstable case, reaching the limit cycle oscillation, being this point close to the stochiometric combustion. The pressure amplitude is now high and constant, next to it, the histogram shows an “u” shape with peaks in high values of pressure. A similar response tendency c can be observed for the PTM signal, in its own unit rank.

Different from what was observed on the original combustor length. Where previously there was a clear transition regime that shared qualities of both, unstable and stable regime, for this geometry is what happens is that on in between conditions of the stable and unstable regime, the systems jump from one to the other.

Looking at the spectrums of both pressure and the PTM signal obtained by a Fourier for both λ=1.8, and 1.2. For the first case, pressure signal, there is a high dB around 100 Hz and further than 200 Hz is not above the 110 dB. The PTM signal does not show any excitation. For the second, λ=1.2, at 162 Hz (of 155 dB for the pressure signal) and 327 Hz with an extra peak for the pressure signal at 585 Hz and 652 Hz, it is clear that both signals are coupled and correlated.

We can see that for the double length case, the pressure peaks have displaced to lower frequencies, and they have a lower amplitude.

Meanwhile, the visual of the flame remains quite similar for both lengths.

In

Figure 8, one more for the double length, the cross-spectrum magnitude, phase and coherence of the pressure and the chemiluminescence are presented for λ=1.8,1.6,1.4 and 1.2. It can be observed that for the λ=1.6, we do not have an important peak in the cross spectrum. A high amplitude oscillation is not reached under these conditions. Apparently, a longer liner gives more damping to the acoustic waves and reaching a self-excited oscillation requires a stronger thermoacoustic source term.

The λ=1.8,1.6,1.4 cases have a magnitude peak in 86 Hz, 146 Hz and 95 Hz respectively, all of them with values below zero. These cases have a phase shift of about 180 degrees and have a negative growth rate.

On the 1.2 case, there are 2 prominent magnitude peaks, at 165 Hz and with a positive value and 467 Hz and 331 Hz with a negative one. Again, the coherence value validates the presence of the peaks.

3.3. Intermittent Case for L2

A particular feature of the studied combustor in double length version is that it presents a clearly intermittent case. Important observations of the intermittent case in a combustor, and how the intermittency keeps being fed by the change in position in the flame related to its repositioning on the recirculation zones have been studied in experimental work [

10]. In

Section 4.2, in

Figure 17, part b, we can see that for cases of an air factor from 1.8 to between 1.4 and 1.6 (which implies an increase of fuel mass flow of 14%), in particular coming from a lean (stable) to a richer (unstable case), an intermittent case occurs. When

Figures 7 (stable) and

8 (unstable) are compared to

Figure 9, this shows clearly the transition from the stable case, with lower amplitudes in the pressure and in the flame OH-chemiluminescence followed by sections of higher amplitude that repeat themselves over the time series of 3.2 seconds. When looking at the histograms, the distribution shape shows this tendency of having sections of big amplitude and maintaining these high values.

The spectra of both signals show important peaks, particularly at lower frequencies, mixed with a decay of the amplitude with frequency.

3.4. Bifurcation Diagrams

It was shown above that the combustion system can operate in two stationary modes: one stable low noise level mode and a mode with a fully developed limit cycle oscillation with saturated amplitude. Interesting is now the transition between these two modes: what happens in the path from stable to limit cycle and how does the system return to the stable mode from a limit cycle oscillation. To this end the traverse between these two modes is explored in both directions. Results of the data obtained from both paths, from stable to unstable and from unstable through 18 different cases are compared. A preliminary view of this was presented in [

16].

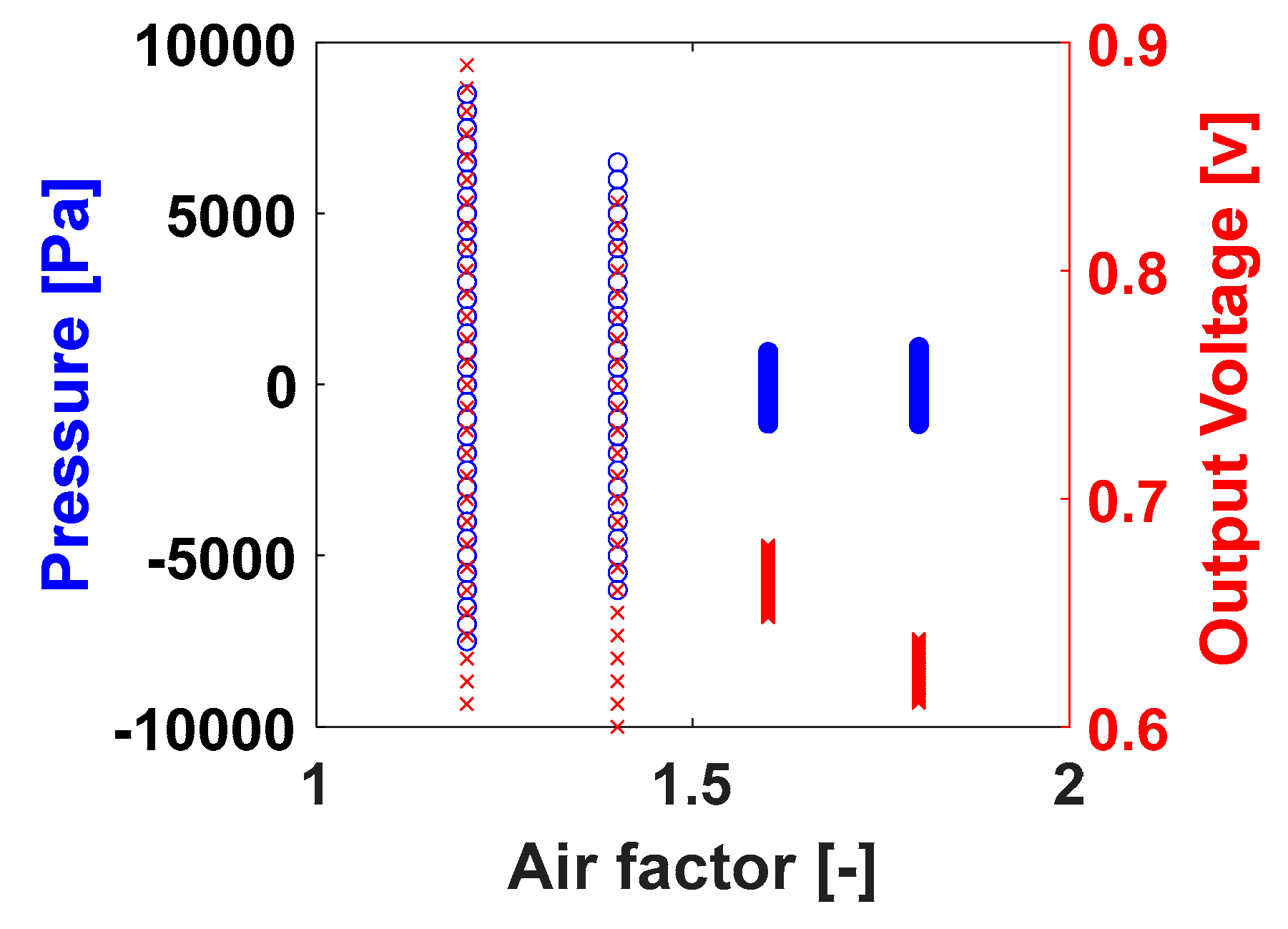

A next step to understand how the pressure amplitude distribution changes in the mode transition, is by analyzing the bifurcation diagram of the pressure and OH* chemiluminescence values.

Figure 11 shows for the L1 case, the pressure amplitude range (on the left) as a function of decreasing air factor with on the right the flame intensity. It is observed that in the stable mode, at high air factor, the range is small, about 400 Pa and near symmetric around the mean pressure. In the transition the range becomes much larger, around 8,000 Pa and asymmetric with emphasis above the mean pressure. For the case of the PMT signal, the amplitude distribution shows again to be dependent of the air fuel equivalence factor and at a lower value of λ, the ranges are much larger than on higher values. Different from the behaviour observed with the pressure bifurcation diagram, the values do not concentrate in the middle value the measured signal, but they are concentrated in the lower values, which makes for a more negatively affected flame intensity by the increasing of air.

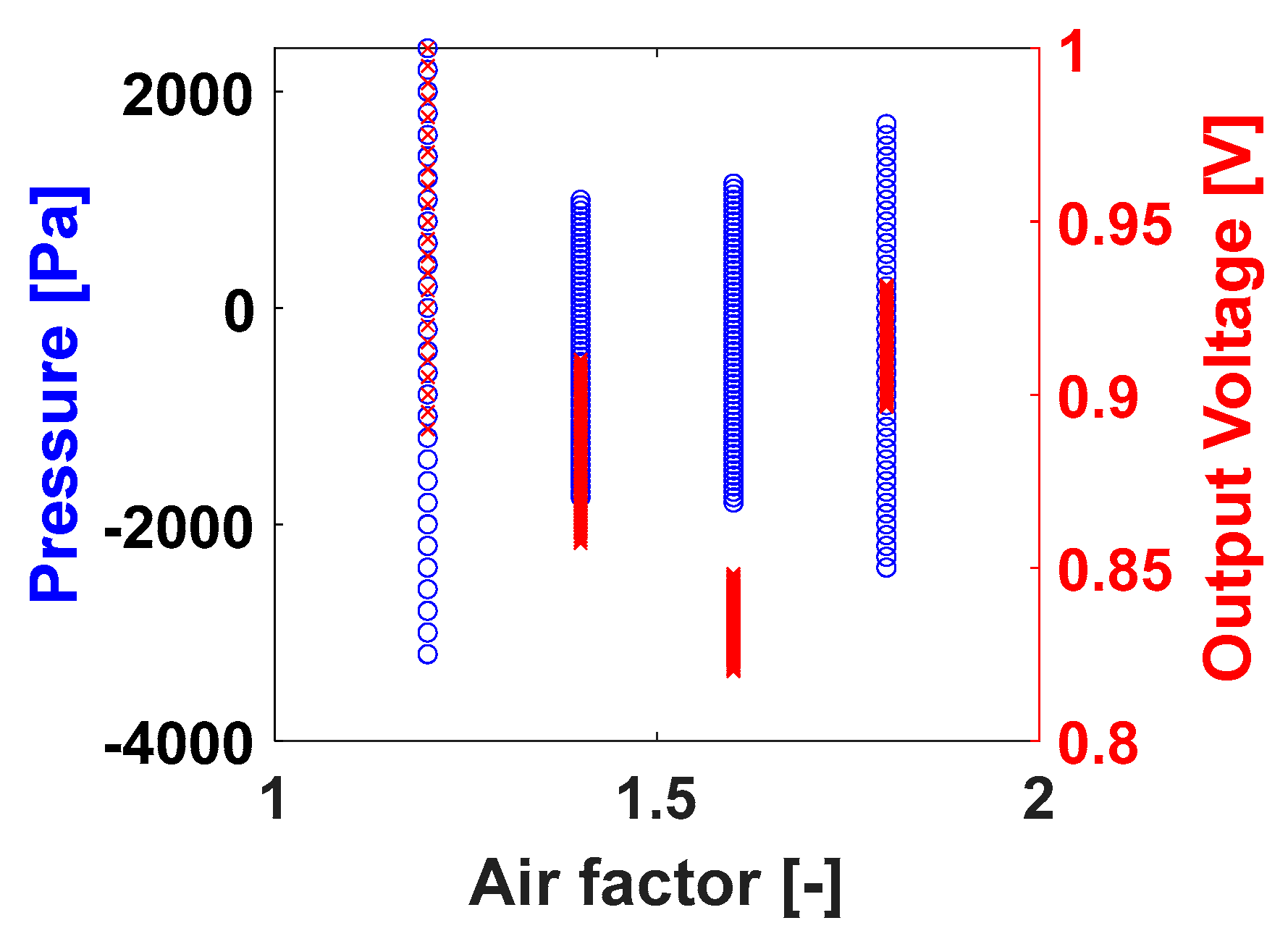

For the L2 case,

Figure 12, the pressure and the intensity signal, where the pressure amplitude range is presented as function of the decreasing air factor, the ranges do not have a marked tendency when working in learner conditions. The ranges get smaller in the in-between conditions where the system is intermittent. For the case of the intensity, the range of intensity values increases as the air factor decreases, but the values themselves are moving from lower to higher without a clear trend.

4. Nonlinear Analysis

After the relatively simple analysis of the pressure amplitude data, a more mathematical analysis is performed on basis of the work on strange attractors by Takens [

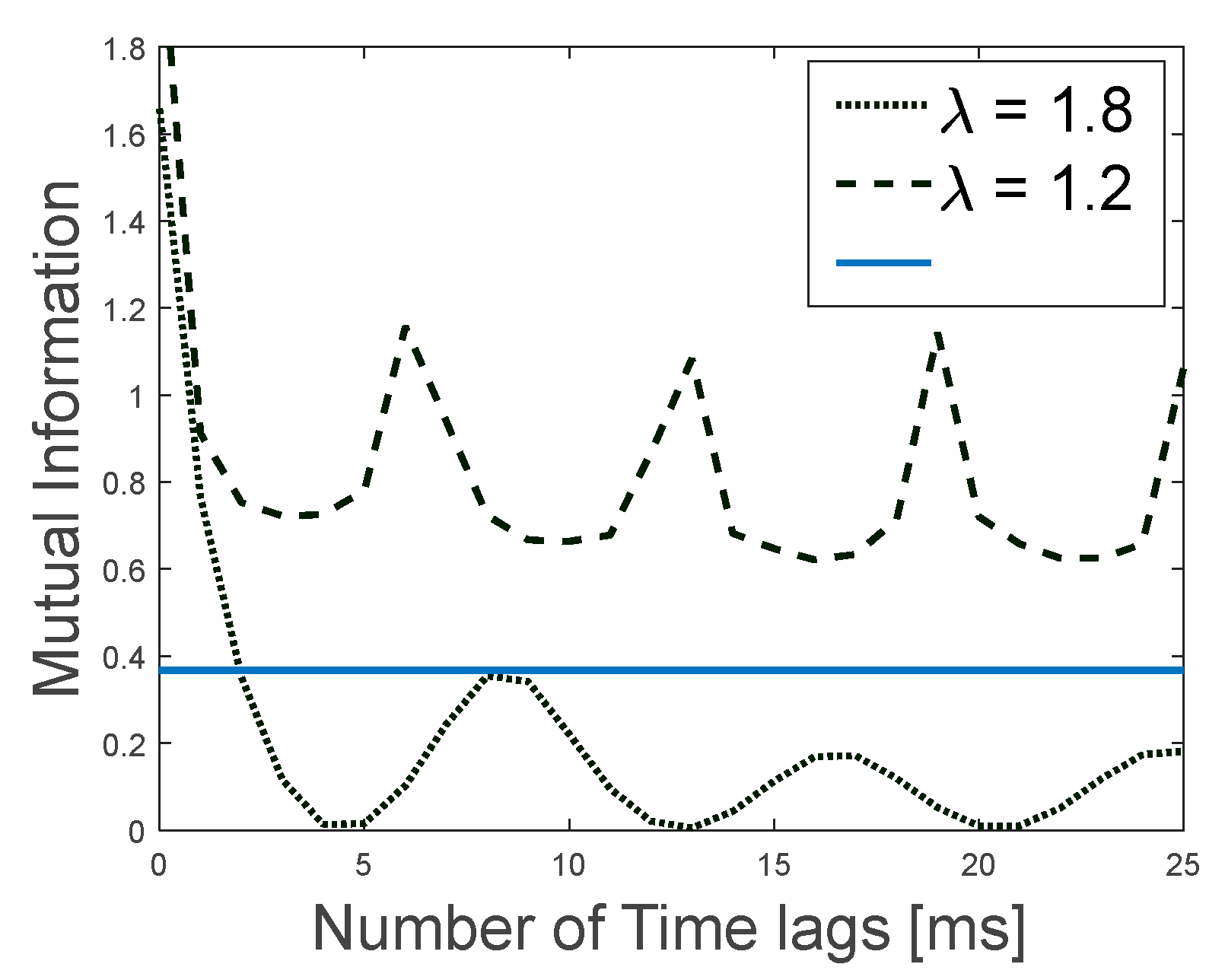

17]. From the obtained time series of the pressure just downstream the flame, phase space coordinates can be constructed on basis of the instantaneous values and the value shifted at a certain time delay to generate phase portraits. This system time delay must satisfy the property of being far enough in time that it can be able to generate new data and at the same time close enough to the original, so it does not become uncorrelated from it. Takens’ approach to find this value is though the Average Mutual Information function (AMI) [

18], a function that relates two measurements that are close to, but almost independent from each other, by their joint probability density. The appropriate system time delay is then the first minimum when plotting this function with the number of time lags possible.

In this approach the global embedding dimension is a parameter that must be determined in order to generate the phase space portrait. This parameter gives the lowest integer global dimension, which is the number of dimensions that is necessary to unfold the observed orbits formed by our time series and its delayed copies, and this can be done by the projection of the attractor to lower dimensional spaces. A methodology to find this value is through applying the False Nearest Neighbors function (FNN), that measures the distance between 2 vectors and finds the nearest neighbor in the phase space. When they are real neighbors, they can go next to the other to form the orbit in the phase portrait. But if they are false, what we are seeing is a projection from a higher dimension, which means that the attractor will not unfold. The dimension that removes all false neighbors and unfolds the attractor is the one defined as the lowest embedding dimension. A more precise explanation of how to determine these 2 important parameters to obtain the phase space portrait is presented below.

4.1. Average Mutual Information Function

The objective is to create a phase portrait that shows the observed variable (in our case the pressure), using coordinates made from this same variable and its value further ahead in time at a system characteristic delay time. The system delay time needs to be determined that is far enough in time to generate new data, but close enough that it does not become totally independent and uncorrelated. Let us consider a set of measurements

and

, with their respective probability densities and joint probability density:

,

and

. The Mutual Information that gives the interaction between two measurements that are almost independent is then defined as:

When

and

are indeed independent, their mutual information is equal to zero, The Average Mutual Information between both measurements can be defined as:

As the name suggests, this function gives the relation between these two sets of measurements and its dependence. When adapting to the information from the measurements

through measurement of

the time lagged measurements, we obtain:

The method suggested by Takens is to use the time lag of the first minimum of the Average Mutual Information function as the system time delay.

In

Figure 13, we can observe how the AMI data behaves for the two system modes. In both modes the value of the AMI oscillates as a function of the number of time lags. For the stable mode (left diagram) the AMI value decreases with increasing time lag, until eventually the correlation between points in the time series is lost, and the Average Mutual Information function tends to zero. In contrast with this, in the limit cycle oscillation mode the AMI amplitude remains high and constant, the AMI does not vanish with increasing time lag. This means the time series remains correlated in its limit cycle oscillation.

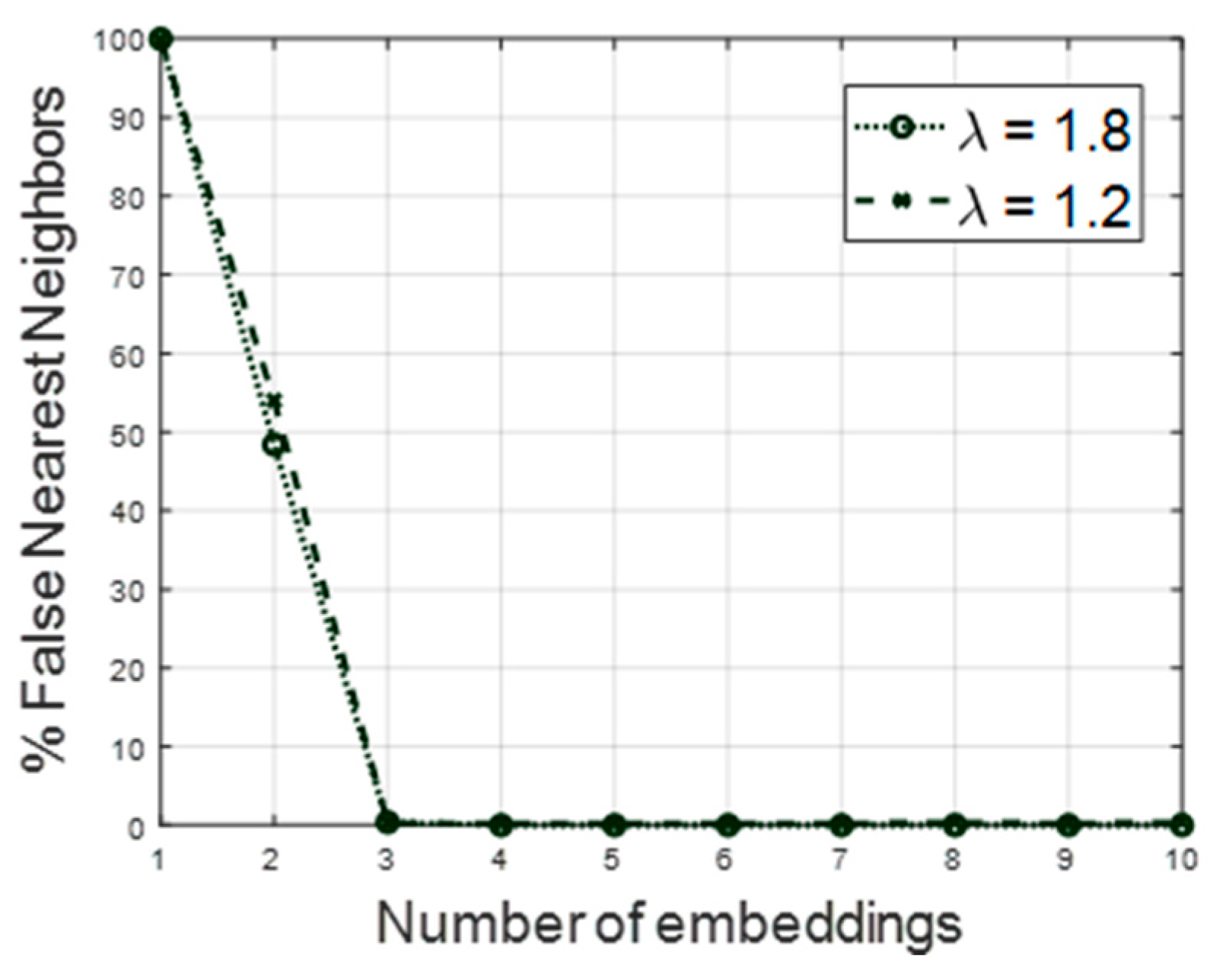

4.2. False Nearest Neighbors Function

To create these phase space reconstructions, we need to determine the integer global dimension, the lowest one, where the necessary number of coordinates to un-fold observed orbits from the same signal times the time delay can be done from the projection of the attractor to a lower dimensional space. This is known as the embedding dimension. This is a global dimension, and several methods can be found in literature to find this value. Following Abarbanel’s [

14] recommendations and proposed methodology, we can talk about vector neighbors and their neighborhoods and apply this with the False Nearest Neighbors function (FNN).

We consider two vectors, one of the state space reconstructions in a d dimension:

When examining the nearest neighbor in phase space of the vector

with time label k, we obtain:

The Euclidean distance between these neighbors is:

While in dimension

is

If is the neighbour, it can be the one before or next to it but along the orbit, allowing the attractor shape to be identified and compact. If they are false neighbours, this meaning that the former arrived at the later neighborhood by a projection from a higher dimension and showing that the dimension d does not unfold the attractor. Going to a dimension the false neighbor can move out of the neighborhood; we can look for which is the lower dimension that removes all false neighbors and unfold the attractor and that juncture is known as the . Once this point is reached the addition of dimensions would not change the false neighbour’s percentage.

Through an extended analysis, the criterion established to find two vectors are false neighbors is that

Is greater than a number of orders two. Considering that R_A is the nominal radius of the attractor defined as the RMS value of the data about its mean.

Figure 14 shows where the percentage of false neighbors drops to zero: 3 for both the air equivalence factor of 1.8 and of 1.2. This translates in that the phase space reconstruction can be made for the pressure signal in the time lags:

In

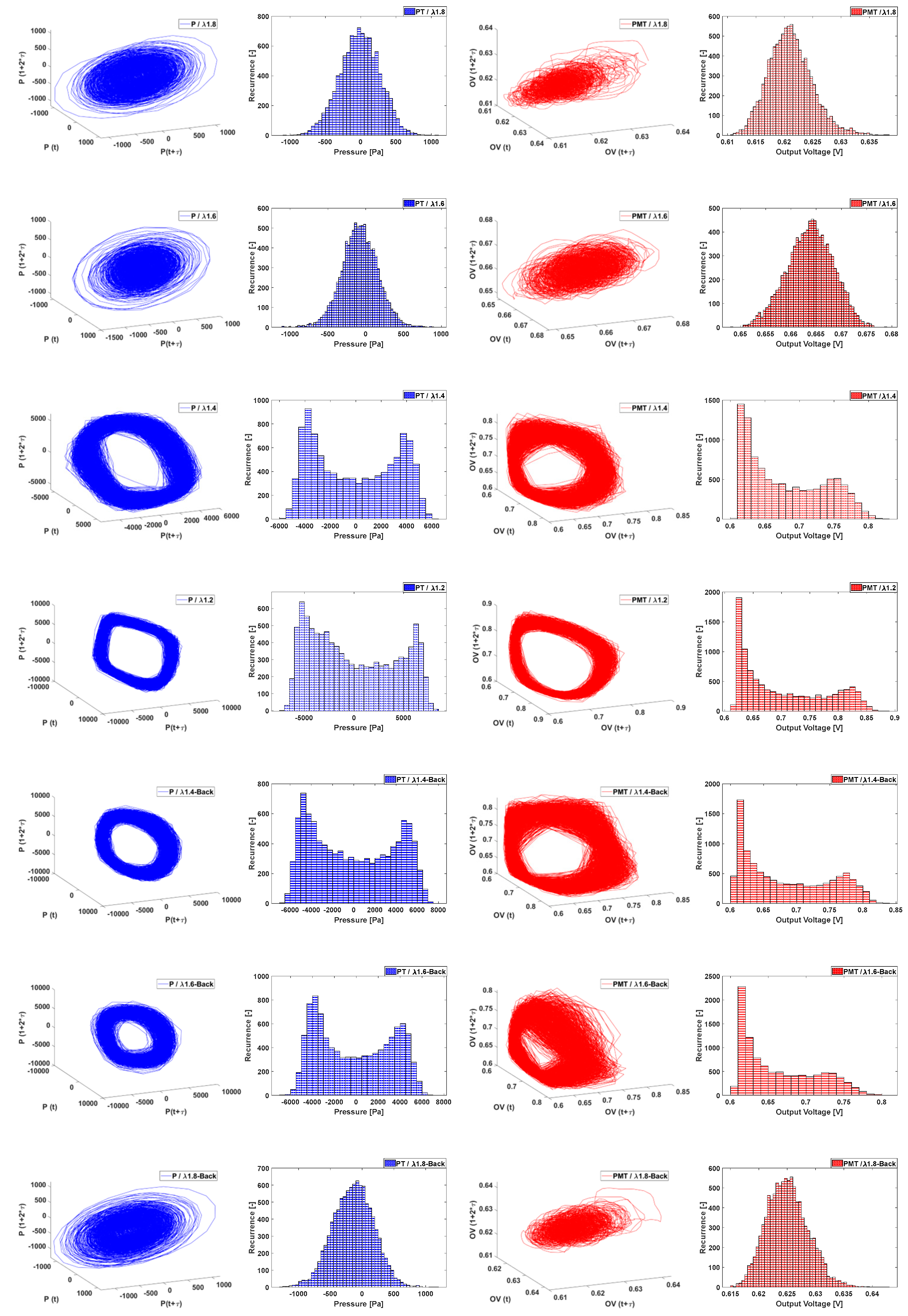

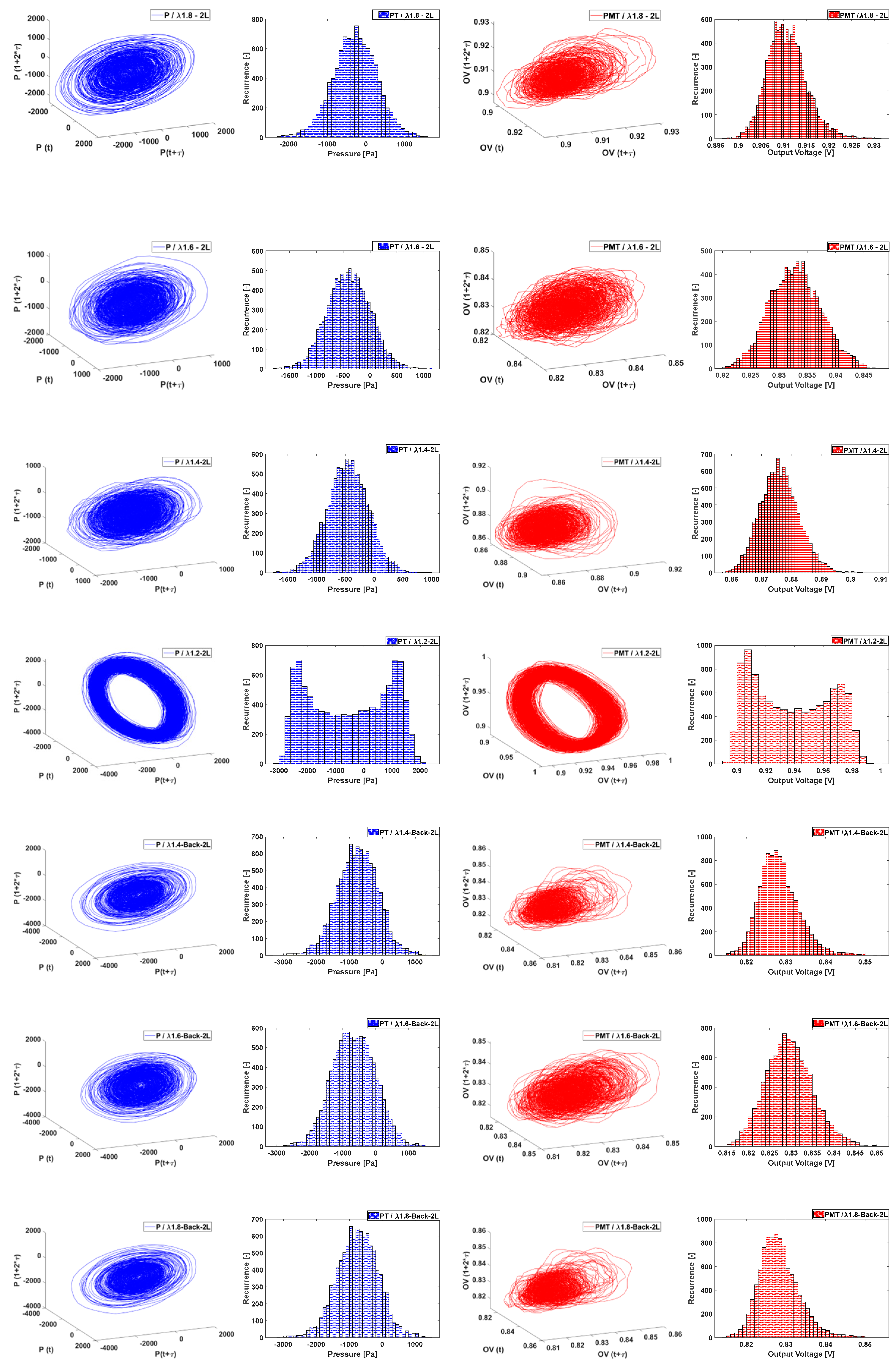

Figure 15, we can observe the generated three phase portraits for a power of 50 kW and the L1, original length. Starting from an air-fuel equivalence ratio,

and up to 1.2, we can clearly see that for the leaner, stable regime, the three phase portraits trajectories are all overlapping together, and we cannot distinguish a tendency or a starting point to evaluate out attractors. On the other hand, as on the richer, unstable regime, the attractor unfolds, presenting a torus shape and the trajectories of the attractor can be noticed. For the case of the PMT signal three phase portraits, the shapes are not as well defined as the ones provided by the pressure signal, but the trend remains when moving to stochiometric combustion, the trajectories unfold towards a torus-like shape.

Figure 16 shows the three phase portraits under the same condition but for L2, double length. As with previous observations, the formed attractors have interjected trajectories for the stable cases and for the high amplitude oscillation case, the attractor unfolds and acquires a torus shape. For the light intensity, the case is similar, but the attractor does not unfold yet in as a clear manner as with the pressure one. Again, when comparing with L1, the high amplitude oscillations is not reached until the

of 1.2.

4.3. Intermittent Case

The obtained three phase portraits for the intermittent case studied in

Section 3.3 are shown in the third row of

Figure 16. These plots show that both stable and unstable behaviour can be observed: detangled, torus shape trajectories tending to higher values and overlapping and jumbled trajectories in the center, crossing values of zero. While in other combustion systems, there is a strong differentiation and even an empty space in between both trajectories tendency. For this combustor geometry, the three phase portraits look almost filled, with just a slight separation between the centered trajectories and the torus shape.

4.4. Hysteresis Effects: Histogram and Phase Portraits Approach

It is known that high amplitude oscillation has a hysterics effect that can be expressed by means of the Hopf bifurcation point. Hereby, by means of the generated histograms and three phase portraits of the pressure and flame intensity time series, we can appreciate the resistance of the system to replicate its conditions when these are preceded by certain operating conditions.

Times series histograms and three phase portraits, both from the pressure and the flame intensity, going from an air factor of 1.8, the leanest that the combustor allows, to 1.6, 1.4 and 1.2 (the closest to the stochiometric value to which the combustor can stand the elevated temperatures) are shown in

Figure 17 and

Figure 18. For both, acoustic and flame intensity histogram results reproduce the same behaviour. When the air factor is high there is a bell shape distribution that, as we previously acknowledged, has a smaller range. As we decrease the air factor the bell shape breaks in a bimodal distribution with peaks of similar number of data points in its extremes. Finally, in the lowest air factor the distribution is more irregular, having both a decreasing tendency for half of it and the u-shaped on the other half. Then, when going back in a higher air factor, λ=1.4, the histogram shape is similar to the previous equal operating condition. Divergent from this case is the following, when going up to λ=1.6 and we encounter still with a u-shaped histogram, opposite to the same operating point in decreasing λ values case, where the histogram was a bell shape. The flame intensity histograms, the ones below and in red, show the same tendency and same resistance to go back in the same shapes for the increasing than for the decreasing of λ, with the notorious difference than the low λ values cases are more of a l-shape histogram than a u-shape. This favoring lower values of the intensity rather than higher one, with soft peak that then decrease in the highest values.

Figure 17.

Three phase portraits and histograms for gauge pressure in blue and PMT/heat release, for L1; following the sequence 1.8 (top), 1.6, 1.4, 1.2, 1.4, 1.6 and 1.8 (bottom).

Figure 17.

Three phase portraits and histograms for gauge pressure in blue and PMT/heat release, for L1; following the sequence 1.8 (top), 1.6, 1.4, 1.2, 1.4, 1.6 and 1.8 (bottom).

Regarding the three phase portraits sequence, we notice that a cleaner, with most trajectories overlapping and making the torus contour thinner, agrees with the operating conditions of the highest amplitude values of the limit cycle oscillations. On the other side of the sequence, the phase portrait with trajectories taking different direction and converging on the center of the plot. As the system gets more unstable because of less lean conditions, the torus shape is gaining strength and then, when going back to leaner conditions, the torus shape thickens and finally all different trajectories converge. For the case of the pressure three phase portraits, this resistance to “close the torus shape“ is shown at λ=1.4, where on the decreasing air-fuel factor case, while open is thicker than in the same operating conditions revisited on the increasing sequence. For the case of the flame intensity, these three phase portraits seem to be affected at all times by the change in conditions and no plot looks as it is equivalent on the increasing sequence. As mentioned already, the flame is heavily affected by both the turbulence and the pressure. The system’s chaotic behaviour is complicated and most transparent where these two signals couple for certain frequencies.

From this, we can conclude that the process that holds for this difference between going from the leanest case to a close to stochiometric versus from the close to stochiometric to the leanest case is hysteresis induced by nonlinear effects induced by the flow. This is to say that the acoustic and flame intensity behaviour is not only function of the current operating conditions but that they are influenced by the past working state of the combustion.

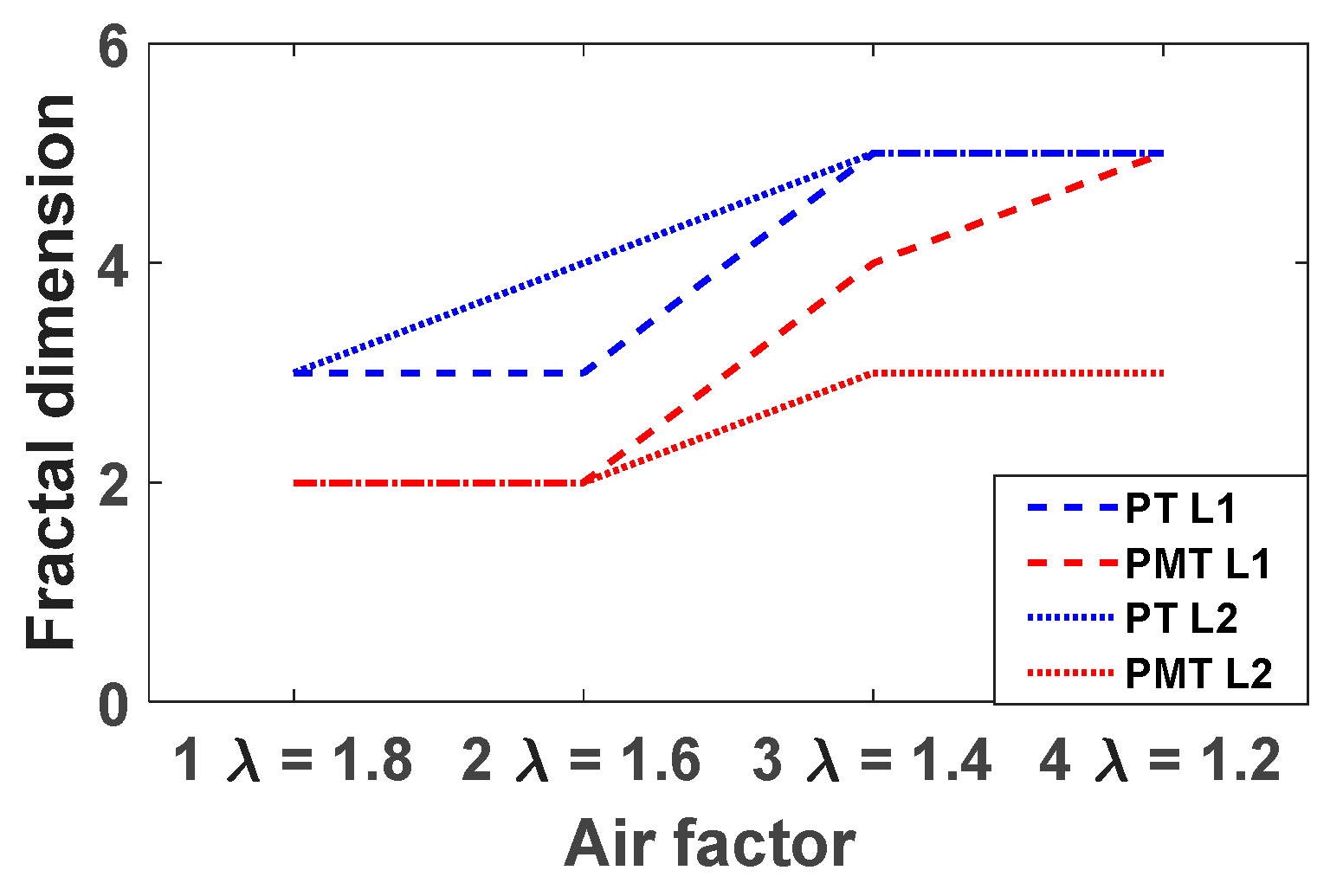

4.5. Fractal Dimension

An important property to characterize the generated attractor in the three phase portraits that can indicate how to unfold the times series is the fractal dimension. This is a telling quantity that can reveal if a system is likely to show deterministic or chaotic behaviour. This fractal dimension must be greater than 2 for a system likely to become chaotic. Several methods are available to find the fractal dimension, accounting for different characteristics for which the original data is available. For the case studied here we use the “box counting” method and the results for different operating points for both, the standard-length case and the double length case, of the pressure and flame intensity are presented in

Figure 19. There is a different behaviour for the pressure signal as compared to the signal of the Photomultiplier Tube (i.e., rate of heat release). It can be observed that at lean air factor (=1.8) the fractal dimension of both the PT and PMT for both combustor lengths are 2 and 3 respectively. This is the fractal dimension of the system of pressure fluctuations and the chemiluminescence of the flame. The fractal dimension of the flame surface of a premixed flame was studied by Kerstein [

19]. There is a strong correlation between the wrinkling of the flame surface and the nature of the flame as a source of sound, as derived by Lighthill. Hence their fractal dimensions must be correlated as well, when the wrinkling is driven by turbulence-combustion interaction. Kerstein predicted a fractal dimension of 7/3 (2.33) for a turbulent premixed flame. This is close to the value for fractal dimension of 2 and 3 as measured here at air factor 1.8.

This value of the fractal dimension changes when the flame is moving into a limit cycle periodic oscillation due to a coupling of the combustion to the acoustic oscillations. When moving to near stoichiometric combustion (air factor 1.2), the fractal dimension increases to 5 for the PT signal and for the standard length for the PMT signal. For the double length the fractal dimension increases slightly less to 3 for the PMT signal. This increase of fractal dimension with a decrease in air factor can be explained by the fact that the pressure field and combustion rate fluctuations are driven here by the limit cycle acoustic oscillations. Then the wrinkling of the flame field is not controlled by combustion-turbulence interaction but by acoustic wave-combustion interaction. Apparently, this leads to an increase of the fractal dimension of the system. Hence the flame/ combustion-acoustic system is developing from marginally chaotic to chaotic when moving from lean to stoichiometric. This is interesting as in this change of air factor the combustion-acoustic system develops a periodic oscillation with a strange attractor in the phase diagram.

By [

20,

21] is suggested that there is a correlation between fractal dimension

, flame structure length

and turbulent flame speed

given by:

This equation does raise some questions, as left- and right-hand side have different dimensions. They observe for a lean flame a fractal dimension of the flame front of 2 at air factor 1.2, in line with [

19]. With the air factor going from lean to stoichiometric the fractal dimension of the flame is measured by them to decrease to 1.8. With a change to stoichiometric the turbulent flame speed will increase. Since flame structure length is less than unity this means the fractal dimension will have to decrease. The difference in behaviour with the present work is explained by the fact that the work of [

20] is on the wrinkled flame fractal dimension, as determined by turbulence-combustion interaction. The work presented here is dominated by combustion-acoustics interaction at near stoichiometric combustion

5. Test 0-1 for Chaos

In the same fashion as [

22], when we are presented with the time series and the pressure spectrum of the path from stable to unstable combustion, we do not see just a great change in the amplitude values, but also, we can find some hints in the high amplitude cases to the presence of deterministic non chaotic behaviour.

There are several techniques to evaluate the presence of chaos in a system, for this study we decide on the 0-1 test, as first proposed by Gottwald and Melbourne [

23]. This under the notion that the methodology is very adaptable to a system of our kind and because the results have a visual appeal to our path kind of study.

For a given series, being these

with

, we obtain the translation variables, been these:

For

. Here, the diffusive or not diffusive behaviour of

and

can be investigated by analysing the mean square displacement

This test shows that id the dynamics of the given system have a regular behaviour, then the mean square displacement will be bounded as a function in time. On the other hand, if the studied system is chaotic, it will scale linearly with time. From this we can assure that we have a mean square displacement that is a function of time, as showed in Equation 3.

And from this, we can obtain an approximation that accounts for a sample time

to Equation 4

For the case of continuous time systems, the mean square displacement is defined as:

Where

accounts for an oscillatory term that is obtained from:

We want to find and express the asymptotic growth rate,

, and if is the value is closer to 0, meaning that our data is deterministic (non chaotic or limit cycle oscilltions), or to 1, meaning that our data is chaotic. In order to obtain these values, we use the regression method. This method consists of having a linear regression for the log-log plot for the

so we have Equation 15

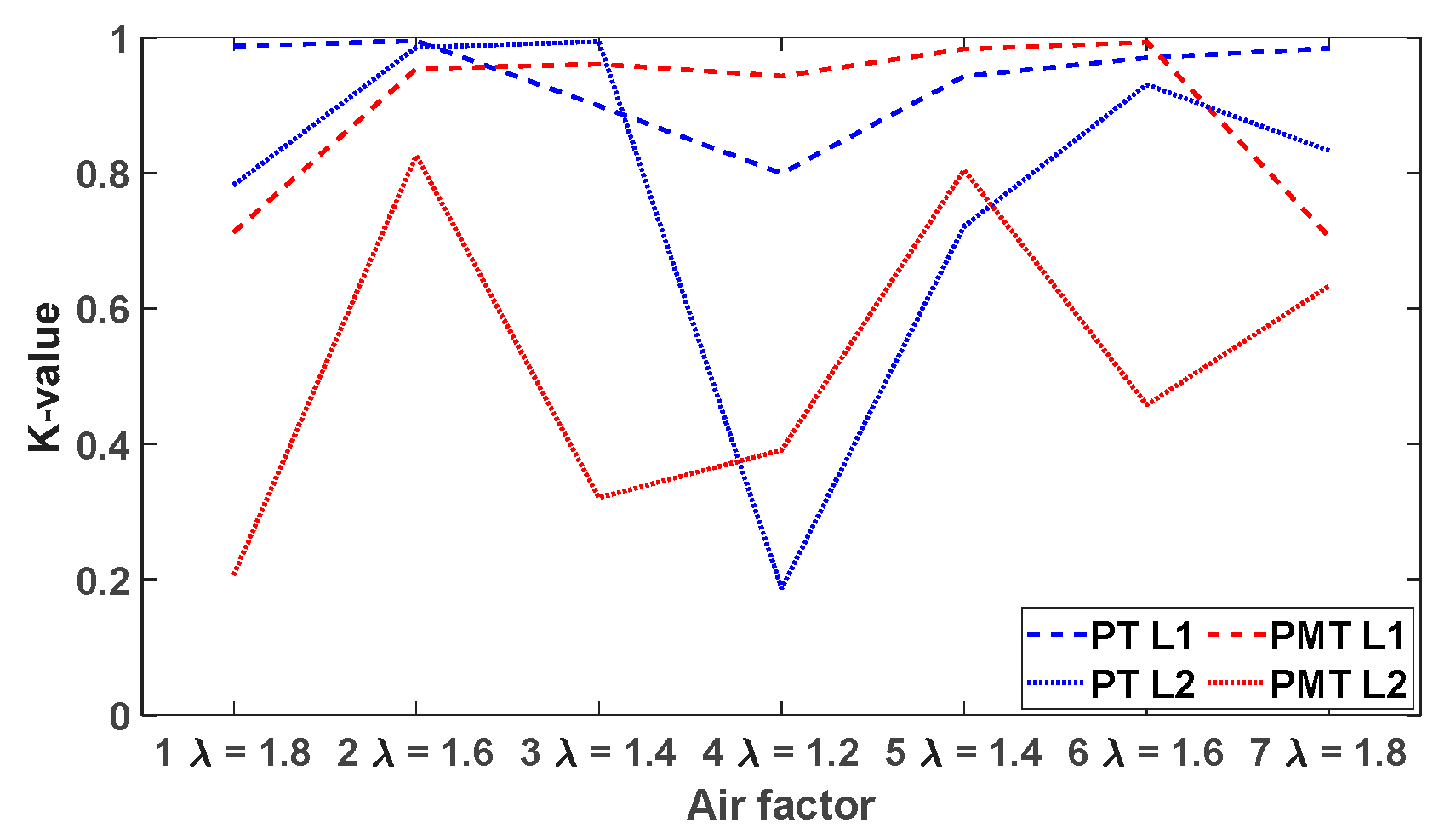

The obtained data from the experiments are implemented for this test. The transition from stable state to unstable and then from unstable to stable is analyzed for both the pressure and the OH* chemiluminescence signals and for cases L1 and L2, as can be seen in

Figure 20. When plotting the K values for both, the pressure (in black) and the PMT signal (in red), we can see that when going from right to left at high λ values, K has values for pressure close to unity, confirming the presence of chaos and an absence of a periodic limit cycle, in line with the absence of a low dimensional attractors in the three phase portraits. Then at λ= 1.2, the value decays to a minimum. This indicates the transition to a low dimensional strange attractor due to a deterministic periodic limit cycle oscillation. When moving further to the left to higher air factors, the value of K goes back up again, but with lower values than in the decreasing sequence, but close enough to the unity (higher than 0.6). This confirms the earlier observations of hysteresis and the reluctance of the system to leave the deterministic oscillation once this has formed.

The behaviour of the PMT signal (rate of heat release) is more complicated and the data less straightforward. When at high air factor, the K value is small and indicating deterministic behavior, which is in contradiction with the observed 3 phase portraits. At intermediate air factor 1.6 the K value increases to unity confirming chaotic behavior. At minimum air factor the K value decrease again to zero, indicating deterministic behavior. It can be concluded that at intermediate to stoichiometric air factor the K value for the PMT signal is a good measure for deterministic behaviour, but in lean conditions this is not the case. For the double length the K variation is more extreme, possibly due to the large damping in the system.

6. Conclusions

In this experimental study, the chaotic nature of the pressure and combustion rate oscillations of a premixed atmospheric combustor is studied as a function of air factor and combustor length. There is a significant difference in the behaviour of the combustor at standard length and double length. At both lengths the combustion is stable and dominated by combustion-turbulence interaction at lean conditions. Near stoichiometric the combustion reaches a limit cycle oscillation driven by acoustics-combustion interaction. The combustion dynamics differ and the operating condition to reach the limit cycle oscillations move, in the sense that a smaller combustor length reaches the instability with leaner conditions. Additional to this, a longer liner length allows for an intermittent state where both, stable and unstable modes coexist. Related to the instability frequencies presented for both cases, for the standard-length high amplitude oscillations occur at 246.4 Hz, 492.9 Hz and 740.8 Hz, whereas for the double length cases the high amplitude oscillations are located at 165.5 Hz, 331.9 Hz and 656. 9 Hz. The 3-phase diagram generated for the pressure and chemiluminescence fluctuations develops from a chaotic diagram to a diagram with a strange attractor when moving from lean to rich combustion and into a limit cycle operation. In this change the amplitude distribution changes from a Gaussian shape to a flat distribution up to the maximum amplitude. For both length cases of high amplitude oscillations, a hysteresis effect is observed when it is moved towards unstable cases and out of it. Subsequently the fractal dimension of the pressure and chemiluminescence fluctuations is determined. At lean combustion where the combustion is coupled primarily to turbulence, the fractal dimension of pressure is found to be 2, and chemiluminescence 3, in line with predictions by literature. When close to stoichiometric the fractal dimension increases to 5 due to a switch to combustion fluctuations dominated by acoustics. Finally, a 0-1 test is performed to investigate if this can indicate an imminent change from stable to unstable combustion. This is confirmed with a change of the value of from unity to a low value when the unstable operation near stoichiometric is approached. The final conclusion is that postprocessing of measured pressure fluctuations or chemiluminescence is a powerful tool to analyse, characterize and predict the behavior of a confined flame in a combustor.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the funding of this research by the EC in the Marie Curie Actions – Networks for Initial Training, Project MAGISTER with project number 766264.

References

- T. Ourbak and L. Tubiana, “Changing the game: the Paris Agreement and the role of scientific communities,” Clim. Policy, vol. 17, no. 7, pp. 819–824, 2017. [CrossRef]

- T. Poinsot, “Prediction and control of combustion instabilities in real engines,” Proc. Combust. Inst., vol. 36, no. 1, pp. 1–28, 2017. [CrossRef]

- D. Zhao, Z. Lu, H. Zhao, X. Y. Li, B. Wang, and P. Liu, “A review of active control approaches in stabilizing combustion systems in aerospace industry,” Prog. Aerosp. Sci., vol. 97, pp. 35–60, Feb. 2018. [CrossRef]

- H. Gotoda, H. Nikimoto, T. Miyano, and S. Tachibana, “Dynamic properties of combustion instability in a lean premixed gas-turbine combustor,” Chaos, vol. 21, no. 1, 2011. [CrossRef]

- L. Kabiraj, R. I. Sujith, and P. Wahi, “Bifurcations of self-excited ducted laminar premixed flames,” J. Eng. Gas Turbines Power, vol. 134, no. 3, pp. 1–7, 2012. [CrossRef]

- Roy, C. P. Premchand, M. Raghunathan, A. Krishnan, V. Nair, and R. I. Sujith, “Critical region in the spatiotemporal dynamics of a turbulent thermoacoustic system and smart passive control,” Combust. Flame, vol. 226, pp. 274–284, 2021. [CrossRef]

- V. Nair and R. I. Sujith, “Multifractality in combustion noise: Predicting an impending combustion instability,” J. Fluid Mech., vol. 747, no. x, pp. 635–655, 2014. [CrossRef]

- V. R. Unni, M. S. Yogesh Prasaad, N. T. Ravi, S. M. Iqbal, B. Pesala, and R. I. Sujith, “Experimental investigation of bifurcations in a thermoacoustic engine,” Int. J. Spray Combust. Dyn., vol. 7, no. 2, pp. 113–130, 2015. [CrossRef]

- E. Karlis, Y. Liu, Y. Hardalupas, and A. M. K. P. Taylor, “H2 enrichment of CH4 blends in lean premixed gas turbine combustion: An experimental study on effects on flame shape and thermoacoustic oscillation dynamics,” Fuel, vol. 254, no. June, p. 115524, 2019. [CrossRef]

- P. Palies, D. Durox, T. Schuller, and S. Candel, “Nonlinear combustion instability analysis based on the flame describing function applied to turbulent premixed swirling flames,” Combust. Flame, vol. 158, no. 10, pp. 1980–1991, 2011. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M. Shahsavari, Z. Rao, S. Yang, and B. Wang, “Thermoacoustic instability drivers and mode transitions in a lean premixed methane-air combustor at various swirl intensities,” Proc. Combust. Inst., vol. 38, no. 4, pp. 6115–6124, 2021. [CrossRef]

- R. Bakker, J. C. Schouten, C. L. Giles, F. Takens, and C. M. van den Bleek, “Learning Chaotic Attractors by Neural Networks,” Neural Comput., vol. 12, no. 10, pp. 2355–2383, Oct. 2000. [CrossRef]

- J. D. Farmer and J. J. Sidorowich, “Predicting chaotic time series,” Phys. Rev. Lett., vol. 59, no. 8, pp. 845–848, 1987. [CrossRef]

- H. D. I. Abarbanel, Analysis of Observed Chaotic Data. New York, NY: Springer New York, 1996.

- T. Kobayashi, S. Murayama, T. Hachijo, and H. Gotoda, “Early Detection of Thermoacoustic Combustion Instability Using a Methodology Combining Complex Networks and Machine Learning,” Phys. Rev. Appl., vol. 11, no. 6, p. 1, 2019. [CrossRef]

- S. N. Arredondo and J. Kok, “A model to study spontaneous oscillations in a lean premixed combustor using non linear analysis,” Proc. 26th Int. Congr. Sound Vib. ICSV 2019, pp. 1–8, 2019.

- F. Takens, “Detecting strange attractors in turbulence,” 1981, pp. 366–381.

- S. Wallot and D. Mønster, “Calculation of Average Mutual Information (AMI) and false-nearest neighbors (FNN) for the estimation of embedding parameters of multidimensional time series in matlab,” Front. Psychol., vol. 9, no. SEP, pp. 1–10, 2018. [CrossRef]

- A. R. KERSTEIN, “Fractal Dimension of Turbulent Premixed Flames,” Combust. Sci. Technol., vol. 60, no. 4–6, pp. 441–445, Aug. 1988. [CrossRef]

- K. K. Y. Noguchi, K. Nakamura, Y. Hagiwara, S. Hitomi, “Flame Propagation and Fractal Dimension in a Concentric Double Cylinders Apparatus,” J. Japanese Soc. Exp. Mech., vol. 14, no. Special Issue, pp. s101–s104, 2014. [CrossRef]

- Y. Wada and K. Kuwana, “A numerical method to predict flame fractal dimension during gas explosion,” J. Loss Prev. Process Ind., vol. 26, no. 2, pp. 392–395, Mar. 2013. [CrossRef]

- Y. Guan, V. Gupta, and L. K. B. Li, “Intermittency route to self-excited chaotic thermoacoustic oscillations,” J. Fluid Mech., vol. 894, pp. 1–13, 2020. [CrossRef]

- G. A. Gottwald and I. Melbourne, “A new test for chaos in deterministic systems,” Proc. R. Soc. A Math. Phys. Eng. Sci., vol. 460, no. 2042, pp. 603–611, 2004. [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

LIMOUSINE combustor lay out.

Figure 1.

LIMOUSINE combustor lay out.

Figure 2.

The triangular wedge flame holder and its mounted position in the combustor.

Figure 2.

The triangular wedge flame holder and its mounted position in the combustor.

Figure 3.

Snapshot of the flame, side of the combustor. Air factor of 1.8 (left) and 1.2 (right).

Figure 3.

Snapshot of the flame, side of the combustor. Air factor of 1.8 (left) and 1.2 (right).

Figure 4.

Acoustic in units of gauge pressure (blue) and PMT/heat release in units of output voltage (red) for λ of 1.8. Power spectra (top), histograms (middle) and time series (bottom).

Figure 4.

Acoustic in units of gauge pressure (blue) and PMT/heat release in units of output voltage (red) for λ of 1.8. Power spectra (top), histograms (middle) and time series (bottom).

Figure 5.

Acoustic in units of gauge pressure (blue) and PMT/heat release in units of output voltage (red) for λ of 1.2. Power spectra (top), histograms (middle) and time series (bottom).

Figure 5.

Acoustic in units of gauge pressure (blue) and PMT/heat release in units of output voltage (red) for λ of 1.2. Power spectra (top), histograms (middle) and time series (bottom).

Figure 6.

Cross spectrum of the oscillation of gauge pressure and PMT/heat release output voltage for magnitude (top), phase (middle) and coherence (bottom). Results are shown for air factors 1.8, 1.6, a.4 and 1.2 with the standard combustor length.

Figure 6.

Cross spectrum of the oscillation of gauge pressure and PMT/heat release output voltage for magnitude (top), phase (middle) and coherence (bottom). Results are shown for air factors 1.8, 1.6, a.4 and 1.2 with the standard combustor length.

Figure 7.

Acoustic in units of gauge pressure (blue) and PMT/heat release in units of output voltage (red) for λ of 1.8. Power spectra (top), histograms (middle) and time series (bottom). Double length.

Figure 7.

Acoustic in units of gauge pressure (blue) and PMT/heat release in units of output voltage (red) for λ of 1.8. Power spectra (top), histograms (middle) and time series (bottom). Double length.

Figure 8.

Acoustic in units of gauge pressure (blue) and PMT/heat release in units of output voltage (red) for λ of 1.2. Power spectra (top), histograms (middle) and time series (bottom). Double length.

Figure 8.

Acoustic in units of gauge pressure (blue) and PMT/heat release in units of output voltage (red) for λ of 1.2. Power spectra (top), histograms (middle) and time series (bottom). Double length.

Figure 9.

Cross spectrum of the oscillation of gauge pressure and PMT/heat release output voltage for magnitude (top), phase (middle) and coherence (bottom). Results are shown for air factors 1.8, 1.6, a.4 and 1.2 with double combustor length.

Figure 9.

Cross spectrum of the oscillation of gauge pressure and PMT/heat release output voltage for magnitude (top), phase (middle) and coherence (bottom). Results are shown for air factors 1.8, 1.6, a.4 and 1.2 with double combustor length.

Figure 10.

Acoustic in units of gauge pressure (blue) and PMT/heat release in units of output voltage (red) for λ of 1.6. Power spectra (top), histograms (middle) and time series (bottom). Double length.

Figure 10.

Acoustic in units of gauge pressure (blue) and PMT/heat release in units of output voltage (red) for λ of 1.6. Power spectra (top), histograms (middle) and time series (bottom). Double length.

Figure 11.

Bifurcation diagram for standard length (L1), for the acoustics/pressure (blue o) and rate of heat release/ PMT output voltage (red x) signals.

Figure 11.

Bifurcation diagram for standard length (L1), for the acoustics/pressure (blue o) and rate of heat release/ PMT output voltage (red x) signals.

Figure 12.

Bifurcation diagram for double length (L2), for the acoustics/pressure (blue o) and heat release/PMT out-put voltage (red x) signals.

Figure 12.

Bifurcation diagram for double length (L2), for the acoustics/pressure (blue o) and heat release/PMT out-put voltage (red x) signals.

Figure 13.

AMI function for an air fuel equivalence factor of 1.8 (dot) and for one of 1.2 (dashed).

Figure 13.

AMI function for an air fuel equivalence factor of 1.8 (dot) and for one of 1.2 (dashed).

Figure 14.

Percentage of false nearest neighbors for an air factor of 1.8 (dot) and for one of 1.2 (dashed).

Figure 14.

Percentage of false nearest neighbors for an air factor of 1.8 (dot) and for one of 1.2 (dashed).

Figure 15.

Three phase portraits for L1. Gauge pressure (P) in blue and PMT/heat release (Output voltage, OV) in red; for λ 1.8, 1.6, 1.4 and 1.2.

Figure 15.

Three phase portraits for L1. Gauge pressure (P) in blue and PMT/heat release (Output voltage, OV) in red; for λ 1.8, 1.6, 1.4 and 1.2.

Figure 16.

Three phase portraits for L2. Gauge pressure (P) in blue and PMT/heat release (Output voltage, OV) in red; for 1.8, 1.6, 1.4 and 1.2

Figure 16.

Three phase portraits for L2. Gauge pressure (P) in blue and PMT/heat release (Output voltage, OV) in red; for 1.8, 1.6, 1.4 and 1.2

Figure 18.

Three phase portraits and histograms for gauge pressure in blue and PMT/heat release, for L2; following the sequence λ 1.8 (top), 1.6, 1.4, 1.2, 1.4, 1.6 and 1.8 (bottom).

Figure 18.

Three phase portraits and histograms for gauge pressure in blue and PMT/heat release, for L2; following the sequence λ 1.8 (top), 1.6, 1.4, 1.2, 1.4, 1.6 and 1.8 (bottom).

Figure 19.

Fractal dimension for both, L1 ( - -) and L2 (…), for gauge pressure (blue) and PMT/heat release (red).

Figure 19.

Fractal dimension for both, L1 ( - -) and L2 (…), for gauge pressure (blue) and PMT/heat release (red).

Figure 20.

Test 0-1 for chaotic behaviour for both, L1 ( - -) and L2 (…), for gauge pressure (blue) and PMT/heat release (red).

Figure 20.

Test 0-1 for chaotic behaviour for both, L1 ( - -) and L2 (…), for gauge pressure (blue) and PMT/heat release (red).

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).