Submitted:

17 March 2025

Posted:

17 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Mapping Urban Flood Vulnerability

- Shorter return times (frequent and rapid phenomena);

- Different spatial representation (larger scale on limited map);

- The presence of obstacles and complex elevation trends do not allow a prevailing direction of flow.

- toppling mechanism;

- complex velocity profile and forces acting on the human body;

- bed slope conditions;

- body shape characteristics;

- bias of controlled laboratory conditions.

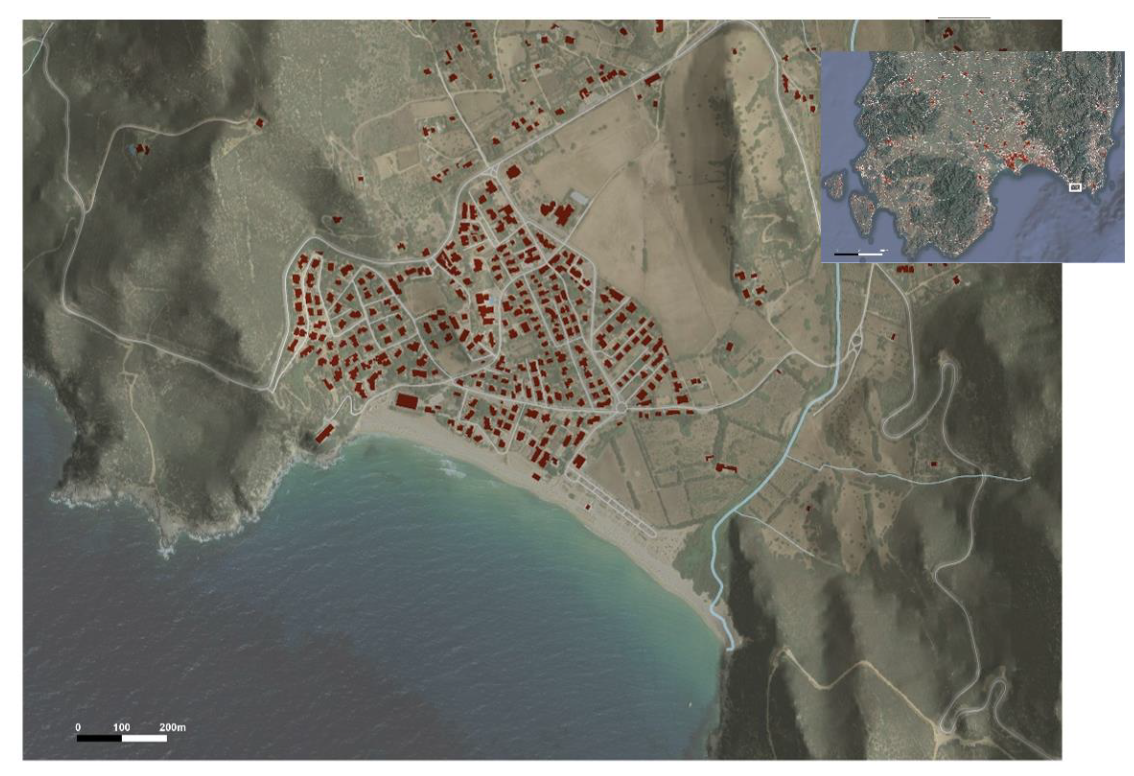

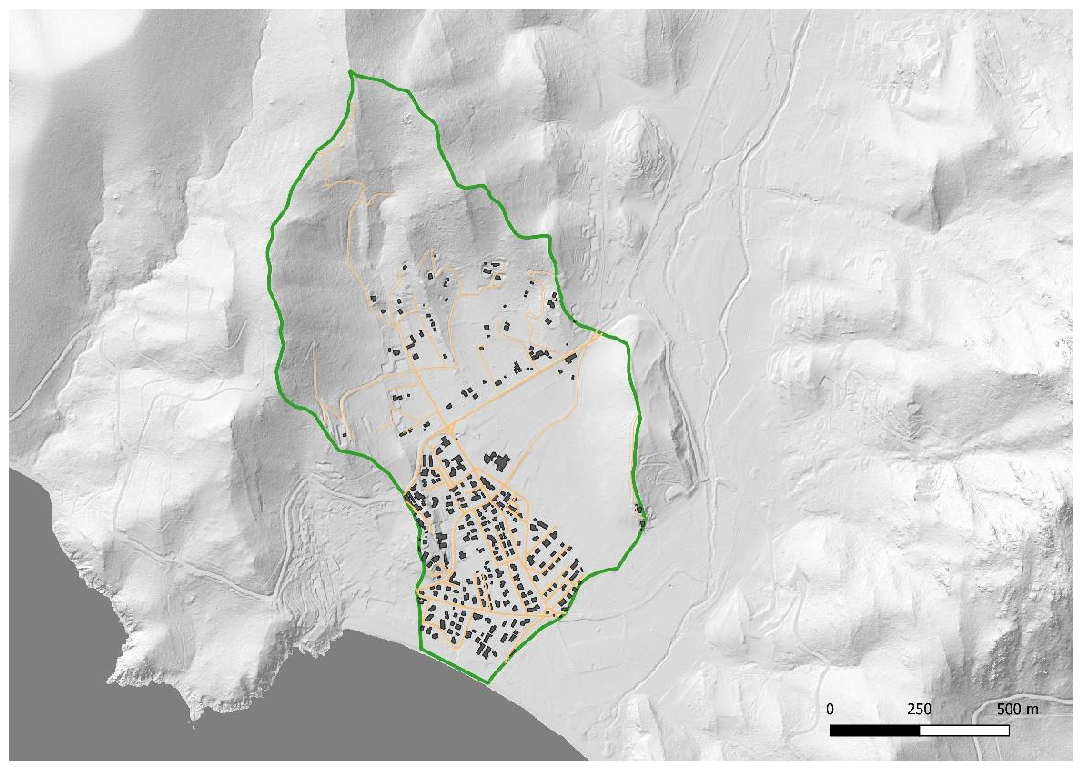

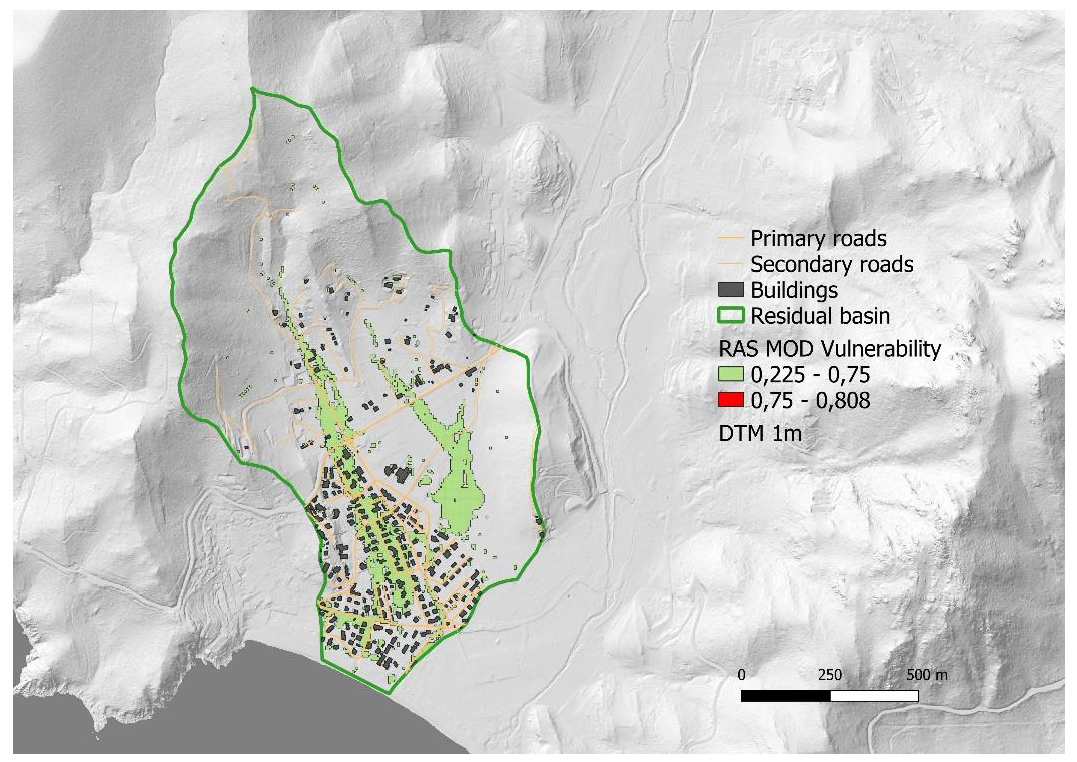

2.2. Area of Study

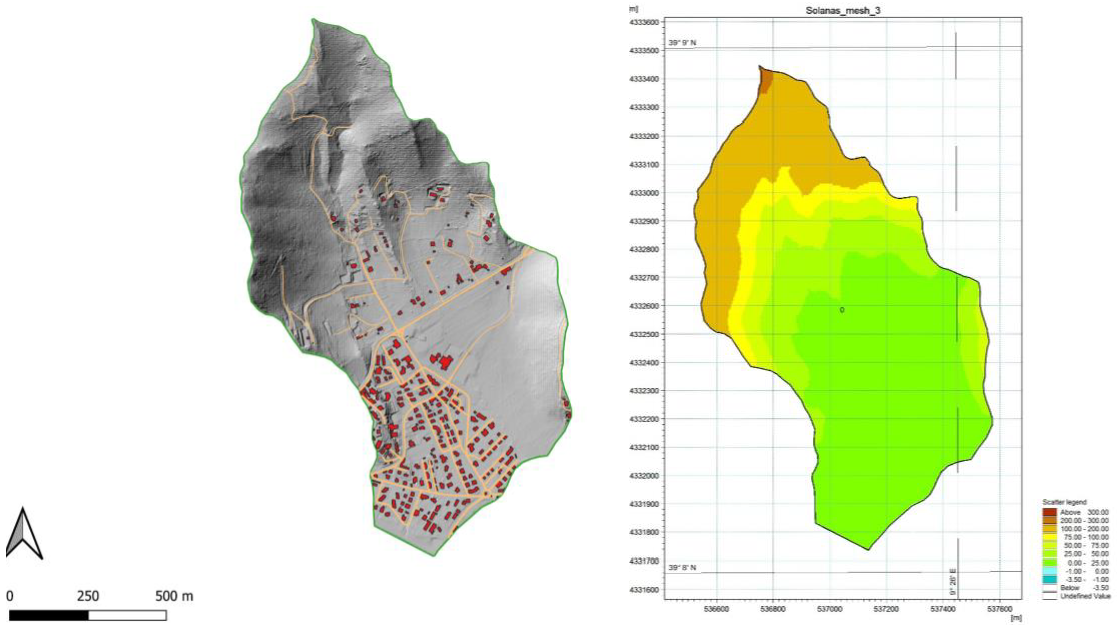

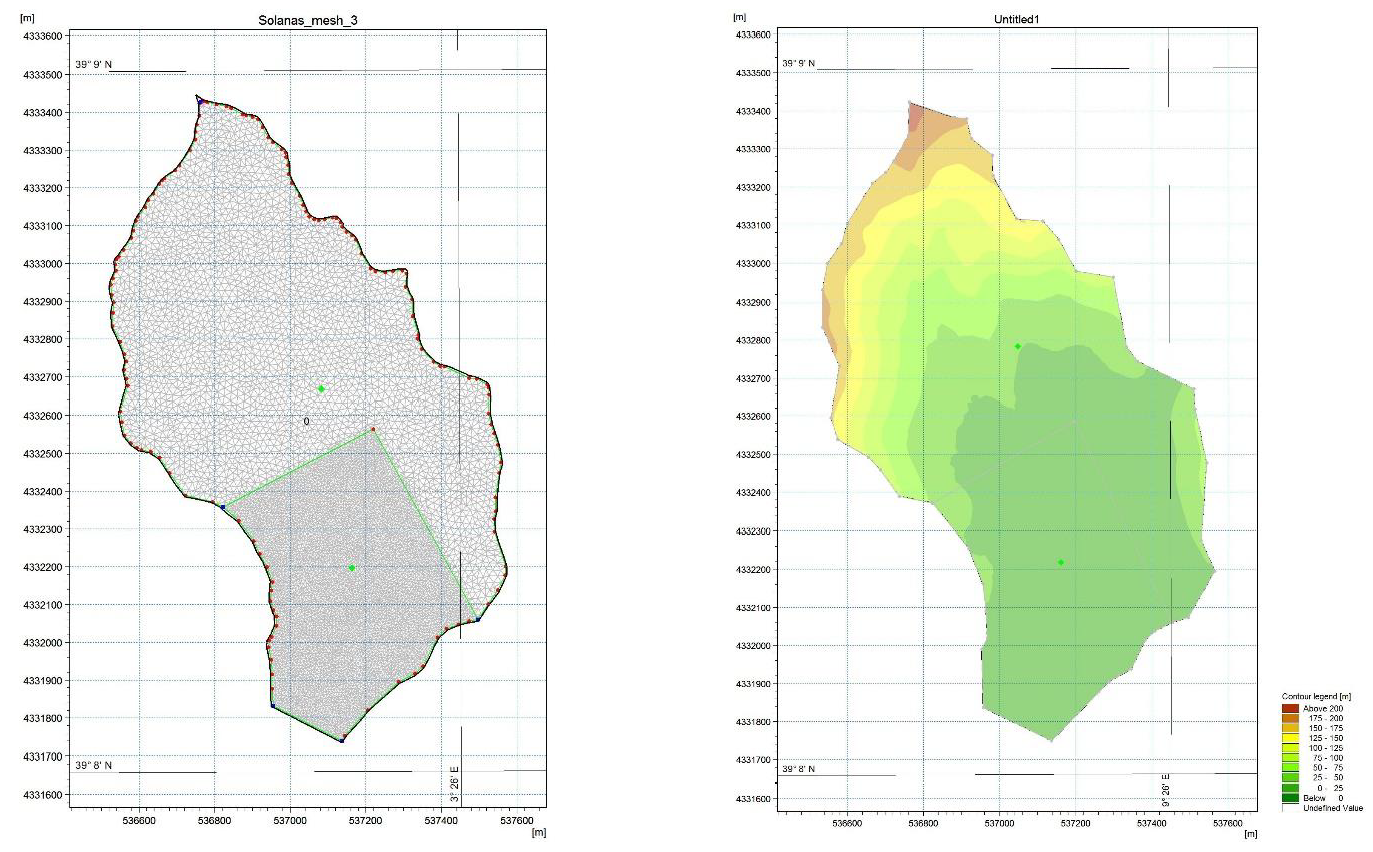

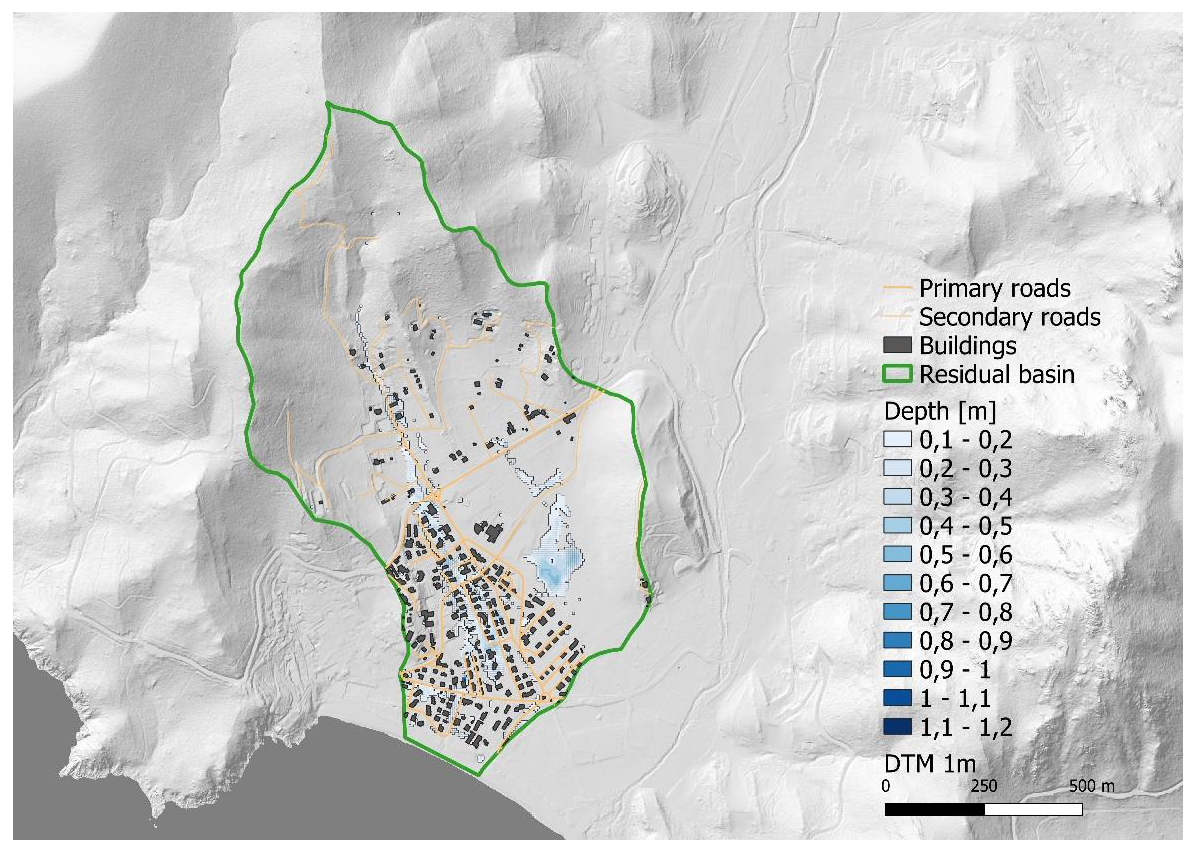

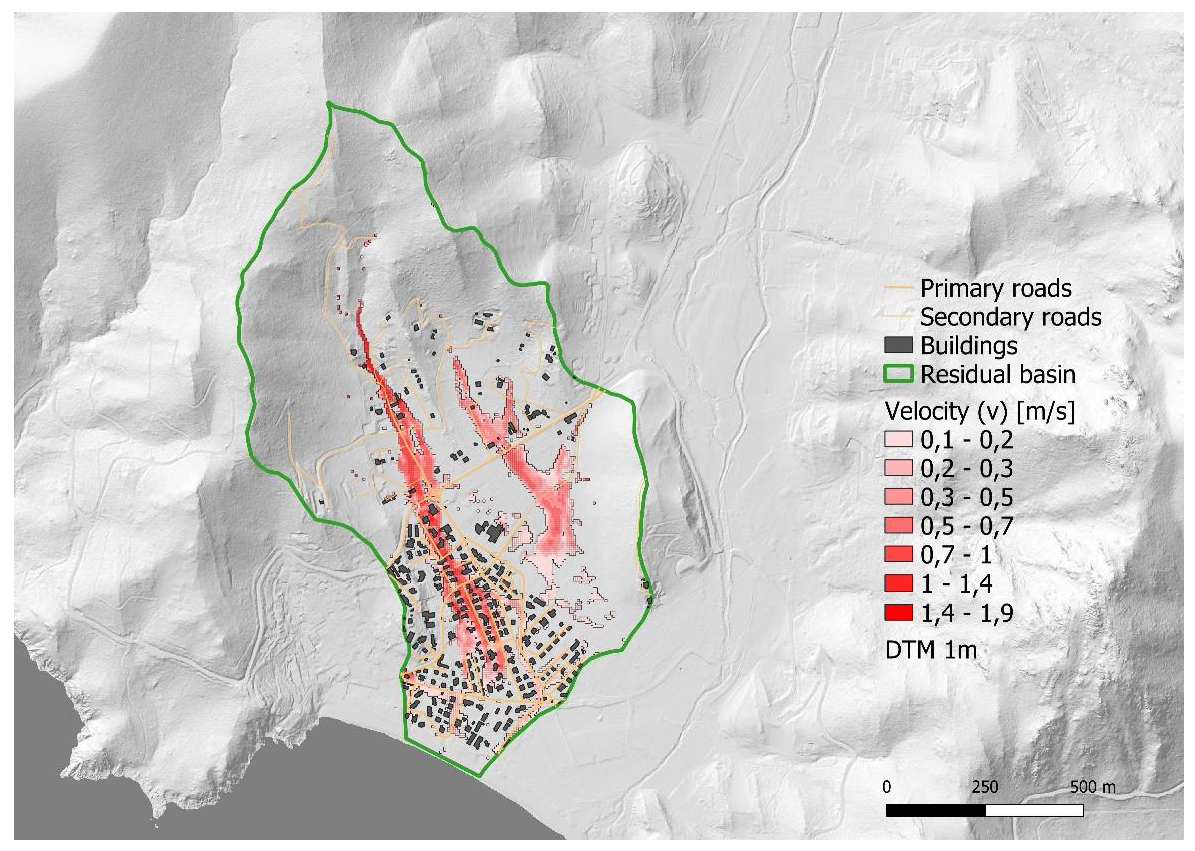

2.3. Numerical Model Application to Solanas Flood

- Hydrological model of inflow-runoff transformation for the determination of runoff (net rainfall hyetogram with leak assessment) for reference rainfall events (gross rainfall from rainfall probability curves or historical rainfall grams);

- Hydraulic model for the study of surface current propagation by solving two-dimensional equations characterizing shallow water equation model – SWE – flow for underground and surface drainage.

3. Results

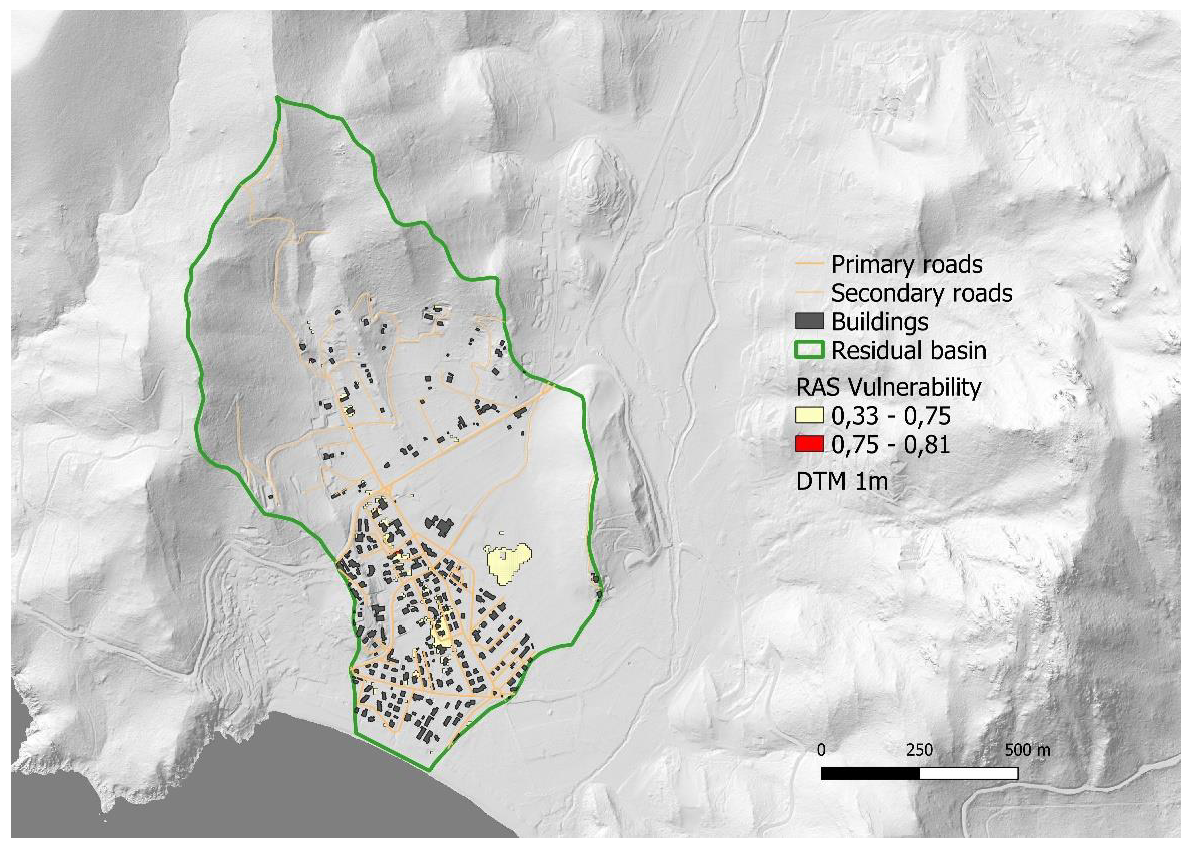

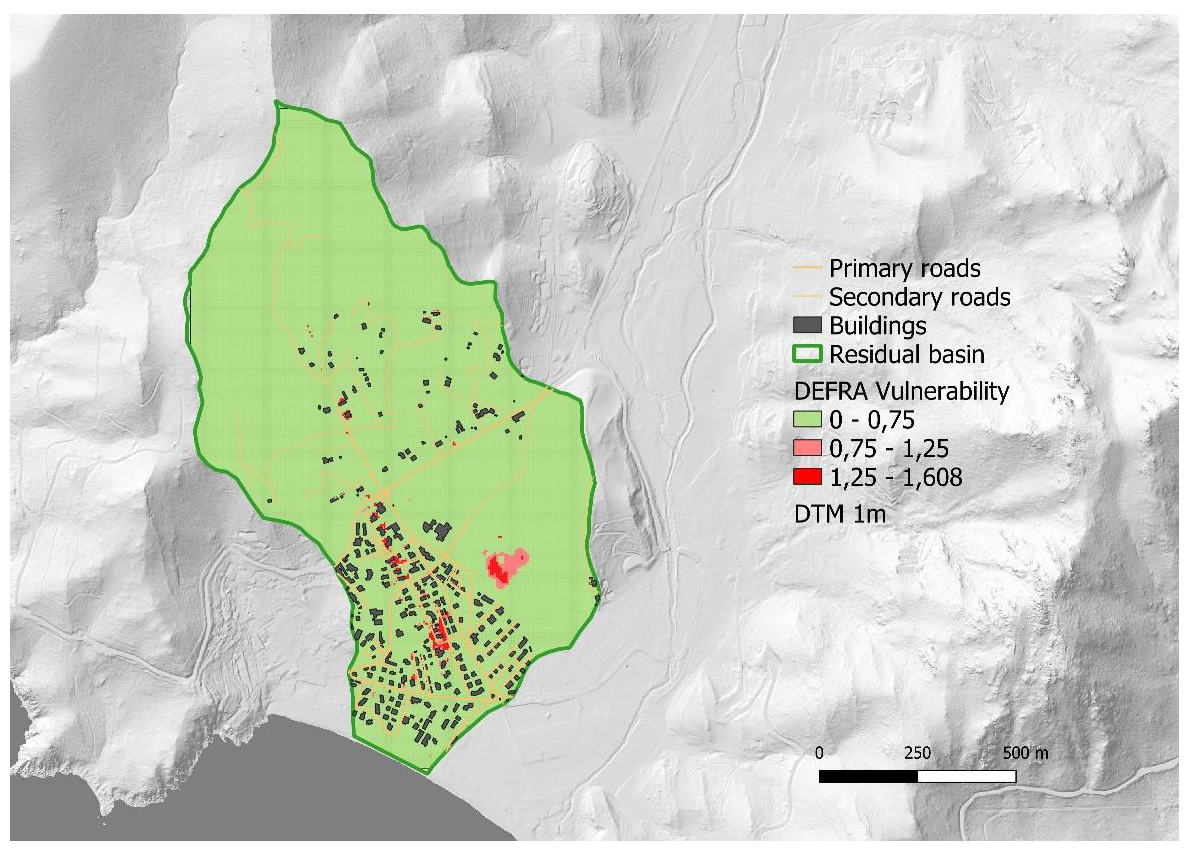

Flood Vulnerability Index Comparison

| Vp | DEFRA class | RAS class |

|---|---|---|

| < 0.75 | low | low |

| 0.75 – 1.0 | moderate | high |

| 1.0 – 1.25 | ||

| 1.25 – 2.5 | significant | |

| > 2.5 | extreme |

4. Discussion

| RAS | RAS_MOD | |

|---|---|---|

| Area [m2] | 14925 (1,5%) | 97825 (9,6%) |

| Area with vulnerability [m2] | 14925 (1,5%) | 97825 (9,6%) |

| Max Vulnerability | 0.81 | 0.81 |

| Std Dev Vulnerability | 0.08 | 0.09 |

| Average Vulnerability | 0.45 | 0.33 |

5. Conclusions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Degeai, J.-P.; Blanchemanche, P.; Tavenne, L.; Tillier, M.; Bohbot, H.; Devillers, B.; Dezileau, L. River flooding on the French Mediterranean coast and its relation to climate and land use change over the past two millennia. Catena 2022, 219, 106623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taillandier, F.; Taillandier, P.; Brueder, P.; Brosse, N. The dynamic sketch map to support reflection on urban flooding. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction 2025, 116, 105121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grimaldi, S.; Petroselli, A.; Serinaldi, F. A continuous simulation model for design-hydrograph estimation in small and ungauged watersheds. Hydrological Sciences Journal 2012, 57, 1035–1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grimaldi, S.; Nardi, F.; Piscopia, R.; Petroselli, A.; Apollonio, C. Continuous hydrologic modelling for design simulation in small and ungauged basins: A step forward and some tests for its practical use. Journal of Hydrology 2021, 595, 125664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apel, H.; Aronica, G.T.; Kreibich, H.; Thieken, A.H. Flood risk analyses – how detailed do we need to be? Natural Hazards 2009, 49, 79–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mark, O.; Weesakul, S.; Apirumanekul, C.; Aroonnet, S.B.; Djordjević, S. Potential and limitations of 1D modelling of urban flooding. Journal of Hydrology 2004, 299, 284–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teng, J.; Jakeman, A.J.; Vaze, J.; Croke, B.F.W.; Dutta, D.; Kim, S. Flood inundation modelling: A review of methods, recent advances and uncertainty analysis. Environmental Modelling & Software 2017, 90, 201–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horritt, M.S.; Bates, P.D. Evaluation of 1D and 2D numerical models for predicting river flood inundation. Journal of Hydrology 2002, 268, 87–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fathi, M.M.; Liu, Z.; Fernandes, A.M.; Hren, M.T.; Terry, D.O.; Nataraj, C.; Smith, V. Spatiotemporal flood depth and velocity dynamics using a convolutional neural network within a sequential Deep-Learning framework. Environmental Modelling & Software 2025, 185, 106307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ignacio, J.A.F.; Cruz, G.T.; Nardi FHenry, S. Assessing the effectiveness of a social vulnerability index in predicting heterogeneity in the impacts of natural hazards: case study of the Tropical Storm Washi flood in the Philippines. Vienna Yearbook of Population Research 2015, 13, 91–129. [Google Scholar]

- Mudashiru, R.B.; Sabtu, N.; Abustan, I.; Balogun, W. Flood hazard mapping methods: A review. Journal of Hydrology 2021, 603, 126846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimitriadis, P.; Tegos, A.; Oikonomou, A.; Pagana, V.; Koukouvinos, A.; Mamassis, N.; Koutsoyiannis, D.; Efstratiadis, A. Comparative evaluation of 1D and quasi-2D hydraulic models based on benchmark and real-world applications for uncertainty assessment in flood mapping. Journal of Hydrology 2016, 534, 478–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Managing the Risks of Extreme Events and Disasters to Advance Climate Change Adaptation; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Rufat, S.; Tate, E.; Burton, C.G.; Maroof, A.S. Social vulnerability to floods: Review of case studies and implications for measurement. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2015, 14, 470–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wing, O.E.; Pinter, N.; Bates, P.D.; Kousky, C. New insights into us flood vulnerability revealed from flood insurance big data. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 1444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cosby, A.G.; Lebakula, V.; Smith, C.N.; et al. Accelerating growth of human coastal populations at the global and continent levels: 2000–2018. Sci Rep 2024, 14, 22489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ardhuin, F.; Stopa, J.E.; Chapron, B.; Collard, F.; Husson, R.; Jensen, R.E.; Johannessen, J.; Mouche, A.; Passaro, M.; Quartly, G.D.; Swail, V.; Young, I. Observing Sea States. Frontiers in Marine Science 2019, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matos Silva, M.; Costa, J.P. Flood Adaptation Measures Applicable in the Design of Urban Public Spaces: Proposal for a Conceptual Framework. Water 2016, 8, 284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, D.; Adams, M. Design For Flooding: Architecture, Landscape, And Urban Design For Resilience To Climate Change. John Wiley & Sons, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Balaian, S.K.; Sanders, B.F.; Abdolhosseini Qomi, M.J. How urban form impacts flooding. Nat Commun 2024, 15, 6911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MIKE + 2D Manual (2023). User Manual. DHI Technical Report.

- Sulis, A.; Altana, M.; Sanna, G. Assessing Reliability, Resilience and Vulnerability of Water Supply from SuDS. Sustainability 2024, 16, 5391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Programma Azione Coste della Sardegna, 2013. Regione Autonoma della Sardegna. Technical Report. https://www.regione.sardegna.it/documenti/1_274_20140121114459.pdf.

- Sulis, A.; Carboni, A.; Manca, G.; Yezza, O.; Serreli, S. Impacts of climate change on the tourist-carrying capacity at La Playa beach (Sardinia, IT). Estuarine, Coastal and Shelf Science 2023, 284, 108284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNDRR, 2020. Human Cost of Disasters, Human Cost of Disasters. An overview of the last 20 years 2000-2019. [CrossRef]

- Arrighi, C.; Pregnolato, M.; Dawson, R.J.; Castelli, F. Preparedness against mobility disruption by floods. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 654, 1010–1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinet, F. (Ed.) Flood Impacts on Loss of Life and Human Health. In Floods; Elsevier, 2017; pp. 33–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yari, A.; Ostadtaghizadeh, A.; Ardalan, A.; et al. Risk factors of death from flood: Findings of a systematic review. J Environ Health Sci Engineer 2020, 18, 1643–1653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaiser, M.; Günnemann, S.; Disse, M. Spatiotemporal analysis of heavy rain-induced flood occurrences in Germany using a novel event database approach. Journal of Hydrology 2021, 595, 125985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agonafir, C.; Lakhankar, T.; Khanbilvardi, R.; Krakauer, N.; Radell, D.; Devineni, N. A review of recent advances in urban flood research. Water Security 2023, 19, 100141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musolino, G.; Ahmadian, R.; Falconer, R.A. Comparison of flood hazard assessment criteria for pedestrians with a refined mechanics-based method. Journal of Hydrology X 2020, 9, 100067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foster, D.N.; Cox, R. Stability of children on roads used as floodways: preliminary study. 1973; 12. [Google Scholar]

- Abt, S.R.; Wittier, R.J.; Taylor, A.; Love, D.J. Human stability in a high flood hazard zone. J. Am. Water Resour. Assoc. 1989, 25, 881–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jonkman, S.N.; Penning-Rowsell, E. Human Instability in Flood Flows. JAWRA Journal of the American Water Resources Association 2008, 44, 1208–1218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jonkman, S.N.; Penning-Rowsell, E. Human Instability in Flood Flows1. JAWRA Journal of the American Water Resources Association 2008, 44, 1208–1218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Xia, J.; Falconer, R.A.; Guo, P. Further improvement in a criterion for human stability in floodwaters. J Flood Risk Management 2019, 12, e12486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramsbottom, D.; Wade, S.; Bain, V.; Hassan, M.; Penning-Rowsell, E.; WIlson, T.; Fernandez, A.; House, M.; Floyd, P. Flood Risk to People: Phase 2. R&D Technical Report FD, Department for the Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (DEFRA), UK Environment Agency. 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Istituto Superiore per la Protezione e la Ricerca Ambientale. Proposta metodologica per l’aggiornamento delle mappe di pericolosità e di rischio, Proposta metodologica per l'aggiornamento delle mappe di pericolosità e di rischio. 2012.

- Piano Stralcio Assetto Idrogeologico (PAI) della Sardegna. Norme Tecniche di Attuazione. Update to 21.11.2024. Norme di Attuazione al PAI - Autorità di Bacino.

- Cox, R.J.; Shand, T.D.; Blacka, M.J. Australian rainfall and runoff (AR&R). Revision project 10: appropriate safety criteria for people. 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Martínez-Gomariz, E.; Gómez, M.; Russo, B. Experimental study of the stability of pedestrians exposed to urban pluvial flooding. Nat Hazards 2016, 82, 1259–1278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Xia, J.; Dong, B.; Liu, Y.; Wang, X. Risk assessment of individuals exposed to urban floods. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction 2023, 88, 103599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| RAS | DEFRA | |

|---|---|---|

| Area [m2] (A) | 14925 (1,5%) | 1020100 (100%) |

| Vulnerable Area [m2] (AV) | 14925 (1,5%) | 723475 (70,9%) |

| Max Vulnerability (MV) | 0.81 | 1.61 |

| Std Dev Vulnerability (SDV) | 0.08 | 0.15 |

| Average Vulnerability (AV) | 0.45 | 0.03 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).