Submitted:

15 March 2025

Posted:

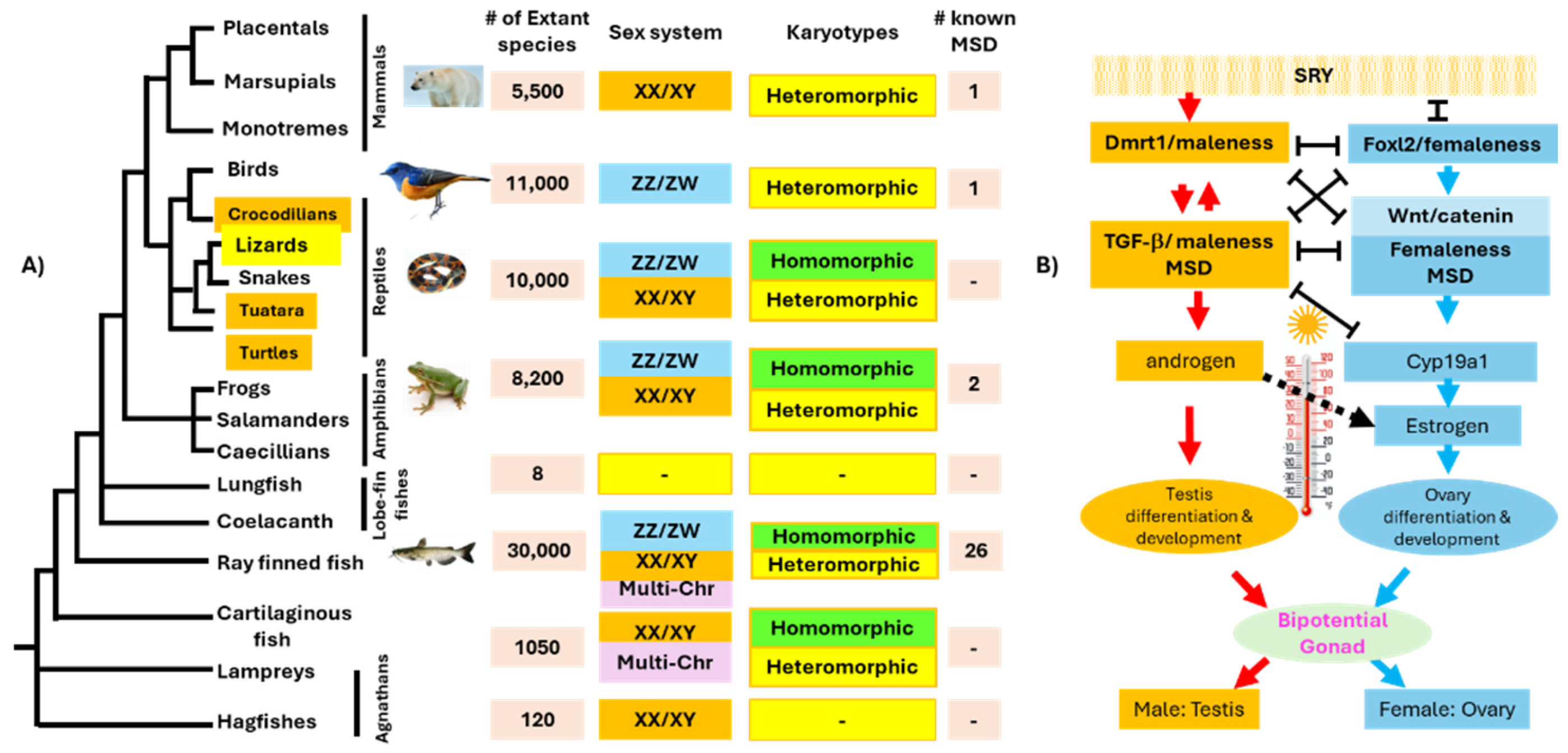

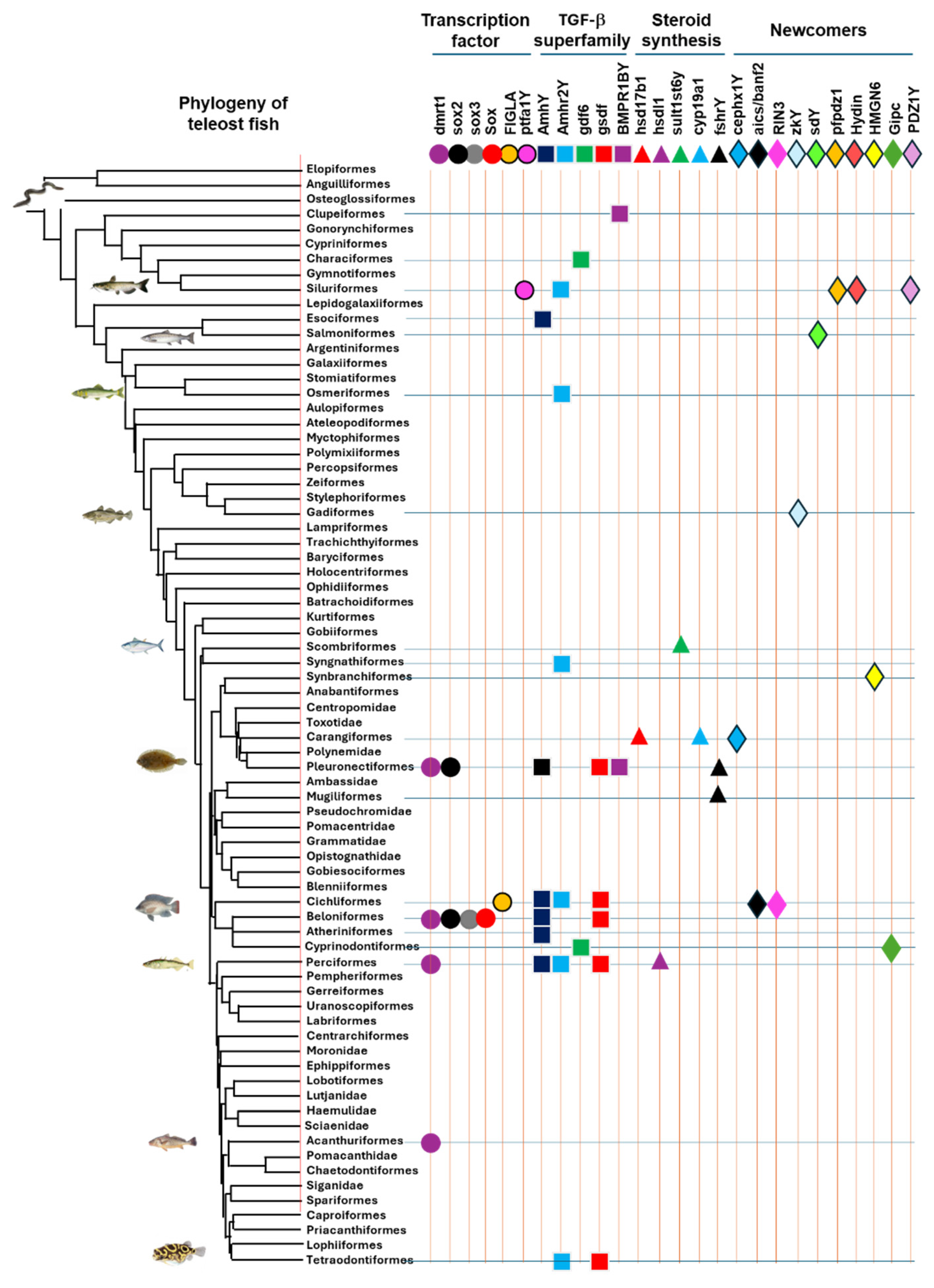

17 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

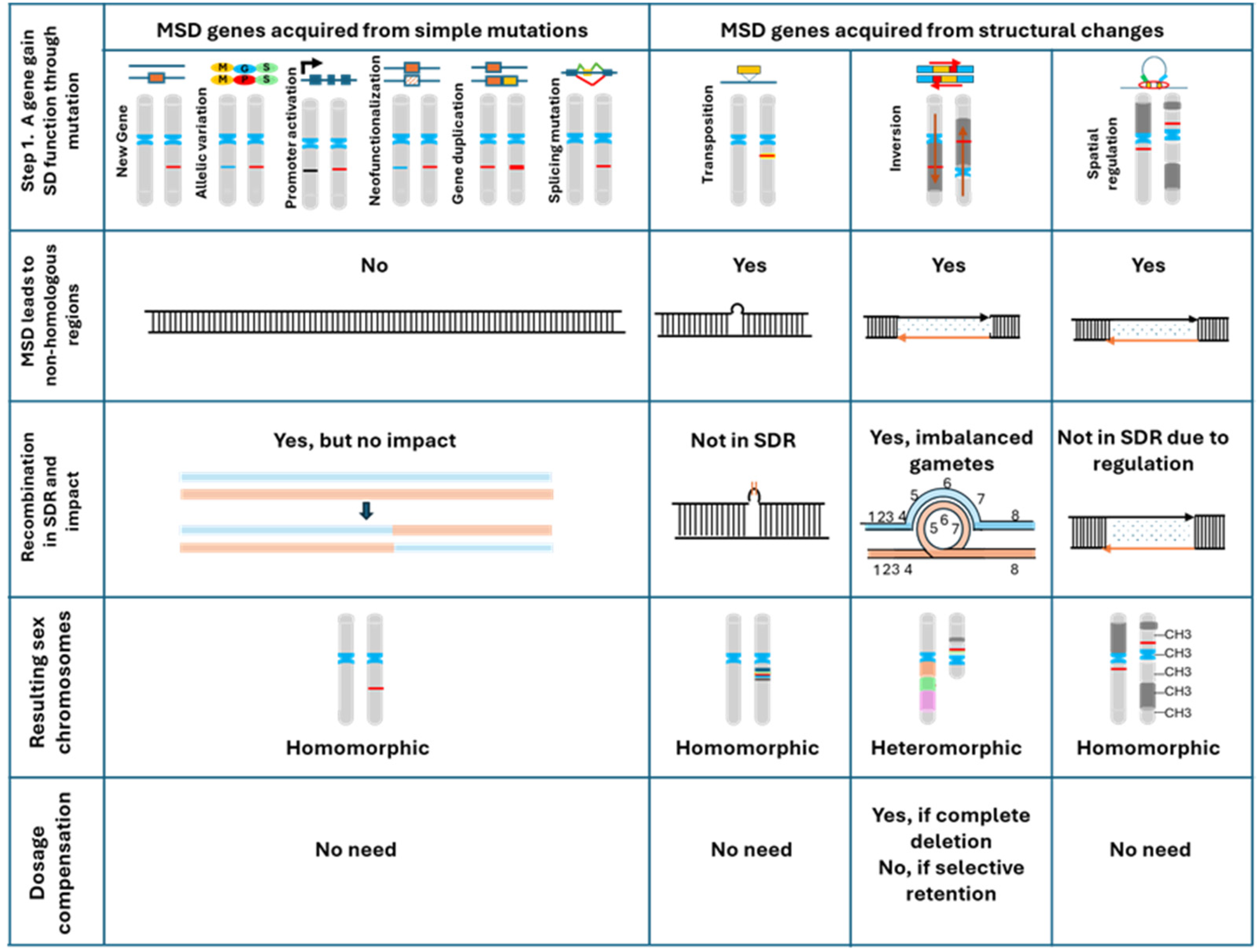

2. Molecular Mechanisms for the Acquisition of MSD Genes

3. The Diversity of Master Sex Determination Genes in Vertebrates

4. Convergent and Divergent Evolution of MSD Genes

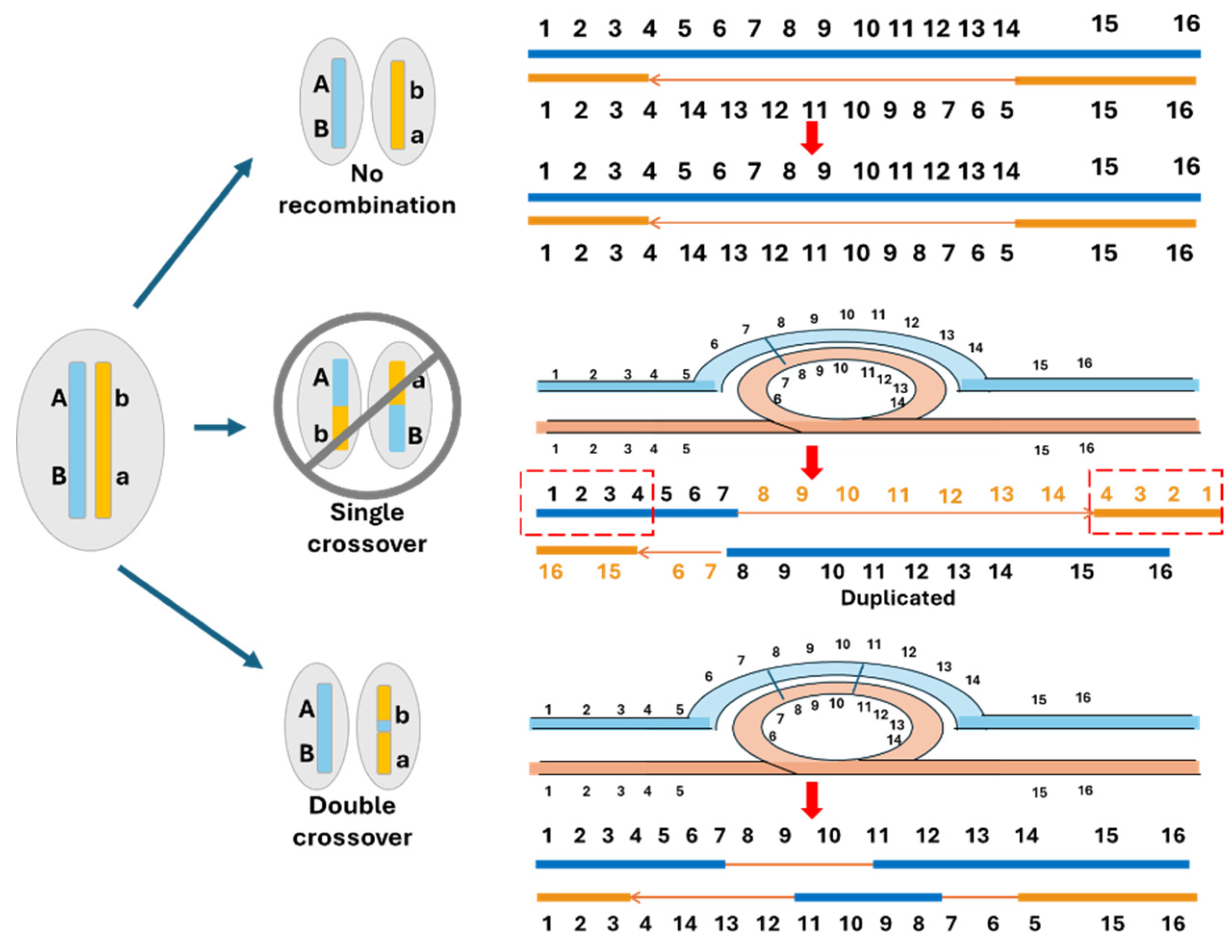

5. The Canonical Model of Sex Chromosome Evolution

6. The Proposed Cause-Effect Model for the Evolution of Sex Chromosomes

6.1. Homomorphic Sex Chromosomes Without Recombination Suppression

6.2. Homomorphic Sex Chromosomes with Limited Region of Recombination Suppression

6.3. Homomorphic Sex Chromosomes with Extended Recombination Suppression

6.4. Heteromorphic Sex Chromosomes

6.5. Multiple and Unequal Sex Chromosome SD Systems

7. Dosage Compensation and Epigenetic Regulation of Sex Chromosome Evolution

8. Conclusions and Perspectives

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Curzon, A.Y.; Shirak, A.; Ron, M.; Seroussi, E. Master-Key Regulators of Sex Determination in Fish and Other Vertebrates—A Review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 2468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kitano, J.; Ansai, S.; Takehana, Y.; Yamamoto, Y. Diversity and Convergence of Sex-Determination Mechanisms in Teleost Fish. Annu. Rev. Anim. Biosci. 2024, 12, 233–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heule, C.; Salzburger, W.; Böhne, A. Genetics of Sexual Development: An Evolutionary Playground for Fish. Genetics 2014, 196, 579–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trukhina, A.V.; Lukina, N.A.; Wackerow-Kouzova, N.D.; Smirnov, A.F. The Variety of Vertebrate Mechanisms of Sex Determination. BioMed Res. Int. 2013, 2013, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adolfi, M.C.; Herpin, A.; Schartl, M. The replaceable master of sex determination: bottom-up hypothesis revisited. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B: Biol. Sci. 2021, 376, 20200090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, G.A. Sexual selection and sexual conflict. In Sexual Selection and Reproductive Competition in Insects; Blum, M.S., Blum, N.A., Eds.; Academic Press: New York, 1979; pp. 123–166. [Google Scholar]

- Charlesworth, D.; Charlesworth, B.; Marais, G. Steps in the evolution of heteromorphic sex chromosomes. Heredity 2005, 95, 118–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, S.H.; Hsiung, K.; Böhne, A. Evaluating the role of sexual antagonism in the evolution of sex chromosomes: new data from fish. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 2023, 81, 102078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z.; Younas, L.; Zhou, Q. Evolution and regulation of animal sex chromosomes. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2024, 26, 59–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinclair, A.H.; Berta, P.; Palmer, M.S.; Hawkins, J.R.; Griffiths, B.L.; Smith, M.J.; Foster, J.W.; Frischauf, A.-M.; Lovell-Badge, R.; Goodfellow, P.N. A gene from the human sex-determining region encodes a protein with homology to a conserved DNA-binding motif. Nature 1990, 346, 240–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, C.A.; Roeszler, K.N.; Ohnesorg, T.; Cummins, D.M.; Farlie, P.G.; Doran, T.J.; Sinclair, A.H. The avian Z-linked gene DMRT1 is required for male sex determination in the chicken. Nature 2009, 461, 267–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gamble, T.; Castoe, T.A.; Nielsen, S.V.; Banks, J.L.; Card, D.C.; Schield, D.R.; Schuett, G.W.; Booth, W. The Discovery of XY Sex Chromosomes in a Boa and Python. Curr. Biol. 2017, 27, 2148–2153.e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuhl, H.; Tan, W.H.; Klopp, C.; Kleiner, W.; Koyun, B.; Ciorpac, M.; Feron, R.; Knytl, M.; Kloas, W.; Schartl, M.; et al. A candidate sex determination locus in amphibians which evolved by structural variation between X- and Y-chromosomes. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 4781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Force, A.; Lynch, M.; Pickett, F.B.; Amores, A.; Yan, Y.-L.; Postlethwait, J. Preservation of Duplicate Genes by Complementary, Degenerative Mutations. Genetics 1999, 151, 1531–1545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevison, L.S.; Hoehn, K.B.; Noor, M.A.F. Effects of Inversions on Within- and Between-Species Recombination and Divergence. Genome Biol. Evol. 2011, 3, 830–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Termolino, P.; Falque, M.; Cigliano, R.A.; Cremona, G.; Paparo, R.; Ederveen, A.; Martin, O.C.; Consiglio, F.M.; Conicella, C. Recombination suppression in heterozygotes for a pericentric inversion induces the interchromosomal effect on crossovers in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 2019, 100, 1163–1175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirkpatrick, M. How and Why Chromosome Inversions Evolve. PLOS Biol. 2010, 8, e1000501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsuda, M.; Nagahama, Y.; Shinomiya, A.; Sato, T.; Matsuda, C.; Kobayashi, T.; Morrey, C.E.; Shibata, N.; Asakawa, S.; Shimizu, N.; et al. DMY is a Y-specific DM-domain gene required for male development in the medaka fish. Nature 2002, 417, 559–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herpin, A.; Schartl, M. Plasticity of gene-regulatory networks controlling sex determination: of masters, slaves, usual suspects, newcomers, and usurpators. Embo Rep. 2015, 16, 1260–1274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Curzon, A.Y.; Shirak, A.; Benet-Perlberg, A.; Naor, A.; Low-Tanne, S.I.; Sharkawi, H.; Ron, M.; Seroussi, E. Absence of Figla-like Gene Is Concordant with Femaleness in Cichlids Harboring the LG1 Sex-Determination System. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 7636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, H.; Ruan, R.; Song, X.; Fan, J.; Du, H.; Shao, J.; Wang, Y.; Yue, H.; Zhang, T.; Li, C. Identification of a candidate sex-determining gene, ptf1aY, in the Chinese longsnout catfish (Leiocassis longirostris) through high-throughput sequencing. Aquac. Rep. 2023, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertho, S.; Herpin, A.; Branthonne, A.; Jouanno, E.; Yano, A.; Nicol, B.; Muller, T.; Pannetier, M.; Pailhoux, E.; Miwa, M.; et al. The unusual rainbow trout sex determination gene hijacked the canonical vertebrate gonadal differentiation pathway. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2018, 115, 12781–12786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Graves, J.A.M.; Peichel, C.L. Are homologies in vertebrate sex determination due to shared ancestry or to limited options? Genome Biol. 2010, 11, 205–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yano, A.; Guyomard, R.; Nicol, B.; Jouanno, E.; Quillet, E.; Klopp, C.; Cabau, C.; Bouchez, O.; Fostier, A.; Guiguen, Y. An Immune-Related Gene Evolved into the Master Sex-Determining Gene in Rainbow Trout, Oncorhynchus mykiss. Curr. Biol. 2012, 22, 1423–1428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yano, A.; Nicol, B.; Jouanno, E.; Quillet, E.; Fostier, A.; Guyomard, R.; Guiguen, Y. The sexually dimorphic on the Y-chromosome gene ( sdY ) is a conserved male-specific Y-chromosome sequence in many salmonids. Evol. Appl. 2013, 6, 486–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashman, T.-L.; Bachtrog, D.; Blackmon, H.; E Goldberg, E.; Hahn, M.W.; Kirkpatrick, M.; Kitano, J.; E Mank, J.; Mayrose, I.; et al.; The Tree of Sex Consortium Tree of Sex: A database of sexual systems. Sci. Data 2014, 1, 140015–140015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furman, B.L.S.; Metzger, D.C.H.; Darolti, I.; Wright, A.E.; Sandkam, B.A.; Almeida, P.; Shu, J.J.; Mank, J.E. Sex Chromosome Evolution: So Many Exceptions to the Rules. Genome Biol. Evol. 2020, 12, 750–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Doorn, G.S.; Kirkpatrick, M. Turnover of sex chromosomes induced by sexual conflict. Nature 2007, 449, 909–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perrin, N. Sex-chromosome evolution in frogs: what role for sex-antagonistic genes? Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B: Biol. Sci. 2021, 376, 20200094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vicoso, B. Molecular and evolutionary dynamics of animal sex-chromosome turnover. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 2019, 3, 1632–1641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Zhang, G.; Shao, C.; Huang, Q.; Liu, G.; Zhang, P.; Song, W.; An, N.; Chalopin, D.; Volff, J.-N.; et al. Whole-genome sequence of a flatfish provides insights into ZW sex chromosome evolution and adaptation to a benthic lifestyle. Nat. Genet. 2014, 46, 253–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peichel, C.L.; McCann, S.R.; Ross, J.A.; Naftaly, A.F.S.; Urton, J.R.; Cech, J.N.; Grimwood, J.; Schmutz, J.; Myers, R.M.; Kingsley, D.M.; et al. Assembly of the threespine stickleback Y chromosome reveals convergent signatures of sex chromosome evolution. Genome Biol. 2020, 21, 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lahn, B.T.; Page, D.C. Four Evolutionary Strata on the Human X Chromosome. Science 1999, 286, 964–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Zhang, J.; Yang, W.; An, N.; Zhang, P.; Zhang, G.; Zhou, Q. Temporal genomic evolution of bird sex chromosomes. BMC Evol. Biol. 2014, 14, 250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glasauer, S.M.K.; Neuhauss, S.C.F. Whole-genome duplication in teleost fishes and its evolutionary consequences. Mol. Genet. Genom. 2014, 289, 1045–1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandve, S.R.; Rohlfs, R.V.; Hvidsten, T.R. Subfunctionalization versus neofunctionalization after whole-genome duplication. Nat. Genet. 2018, 50, 908–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peatman, E.; Bao, B.; Peng, X.; Baoprasertkul, P.; Brady, Y.; Liu, Z. Catfish CC chemokines: genomic clustering, duplications, and expression after bacterial infection with Edwardsiella ictaluri. Mol. Genet. Genom. 2005, 275, 297–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takehana, Y.; Hamaguchi, S.; Sakaizumi, M. Different origins of ZZ/ZW sex chromosomes in closely related medaka fishes, Oryzias javanicus and O. hubbsi. Chromosom. Res. 2008, 16, 801–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, M.; Pan, Q.; Jouanno, E.; Montfort, J.; Zahm, M.; Cabau, C.; Klopp, C.; Iampietro, C.; Roques, C.; Bouchez, O.; et al. An ancient truncated duplication of the anti-Müllerian hormone receptor type 2 gene is a potential conserved master sex determinant in the Pangasiidae catfish family. Mol. Ecol. Resour. 2022, 22, 2411–2428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, S.; Tao, W.; Yang, H.; Kocher, T.D.; Wang, Z.; Peng, Z.; Jin, L.; Pu, D.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, D. Identification of sex chromosome and sex-determining gene of southern catfish (Silurus meridionalis) based on XX, XY and YY genome sequencing. Proceedings Biol. Sci. 2022, 289, 20212645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, S.; Tao, W.; Tao, H.; Yang, H.; Wu, L.; Shao, F.; Wang, Z.; Jin, L.; Peng, Z.; Wang, D.; et al. Characterization of the male-specific region containing the candidate sex-determining gene in Amur catfish (Silurus asotus) using third-generation- and pool-sequencing data. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 248, 125908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Gong, G.; Li, Z.; Niu, J.-S.; Du, W.-X.; Wang, Z.-W.; Wang, Y.; Zhou, L.; Zhang, X.-J.; Lian, Z.-Q.; et al. Genomic Anatomy of Homozygous XX Females and YY Males Reveals Early Evolutionary Trajectory of Sex-determining Gene and Sex Chromosomes inSilurusFishes. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2024, 41, msae169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kappas, I.; Vittas, S.; Pantzartzi, C.N.; Drosopoulou, E.; Scouras, Z.G. A Time-Calibrated Mitogenome Phylogeny of Catfish (Teleostei: Siluriformes). PLOS ONE 2016, 11, e0166988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gong, G.; Xiong, Y.; Xiao, S.; Li, X.-Y.; Huang, P.; Liao, Q.; Han, Q.; Lin, Q.; Dan, C.; Zhou, L.; et al. Origin and chromatin remodeling of young X/Y sex chromosomes in catfish with sexual plasticity. Natl. Sci. Rev. 2022, 10, nwac239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Natri, H.M.; Merilä, J.; Shikano, T. The evolution of sex determination associated with a chromosomal inversion. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Checchi, P.M.; Engebrecht, J. Heteromorphic sex chromosomes: Navigating meiosis without a homologous partner. Mol. Reprod. Dev. 2011, 78, 623–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A Ross, J.; Peichel, C.L. Molecular Cytogenetic Evidence of Rearrangements on the Y Chromosome of the Threespine Stickleback Fish. Genetics 2008, 179, 2173–2182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sember, A.; Nguyen, P.; Perez, M.F.; Altmanová, M.; Ráb, P.; Cioffi, M.d.B. Multiple sex chromosomes in teleost fishes from a cytogenetic perspective: state of the art and future challenges. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B: Biol. Sci. 2021, 376, 20200098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Zhang, R.; Fan, G.; Xu, W.; Zhou, Q.; Wang, L.; Li, W.; Pang, Z.; Yu, M.; Liu, Q.; et al. Reconstruction of the Origin of a Neo-Y Sex Chromosome and Its Evolution in the Spotted Knifejaw,Oplegnathus punctatus. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2021, 38, 2615–2626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Payer, B.; Lee, J.T. X Chromosome Dosage Compensation: How Mammals Keep the Balance. Annu. Rev. Genet. 2008, 42, 733–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brockdorff, N.; Turner, B.M. Dosage Compensation in Mammals. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2015, 7, a019406–a019406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A McQueen, H.; McBride, D.; Miele, G.; Bird, A.P.; Clinton, M. Dosage compensation in birds. Curr. Biol. 2001, 11, 253–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deviatiiarov, R.; Nagai, H.; Ismagulov, G.; Stupina, A.; Wada, K.; Ide, S.; Toji, N.; Zhang, H.; Sukparangsi, W.; Intarapat, S.; et al. Dosage compensation of Z sex chromosome genes in avian fibroblast cells. Genome Biol. 2023, 24, 213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, M.A.; Kitano, J.; Peichel, C.L. Purifying Selection Maintains Dosage-Sensitive Genes during Degeneration of the Threespine Stickleback Y Chromosome. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2015, 32, 1981–1995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darolti, I.; Wright, A.E.; Sandkam, B.A.; Morris, J.; Bloch, N.I.; Farré, M.; Fuller, R.C.; Bourne, G.R.; Larkin, D.M.; Breden, F.; et al. Extreme heterogeneity in sex chromosome differentiation and dosage compensation in livebearers. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2019, 116, 19031–19036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metzger, D.C.H.; A Sandkam, B.; Darolti, I.; E Mank, J. Rapid Evolution of Complete Dosage Compensation in Poecilia. Genome Biol. Evol. 2021, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Z.; Zhou, T.; Gao, D. Genetic and epigenetic regulation of growth, reproduction, disease resistance and stress responses in aquaculture. Front. Genet. 2022, 13, 994471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, L.; Tian, C.; Liu, S.; Zhang, Y.; Elaswad, A.; Yuan, Z.; Khalil, K.; Sun, F.; Yang, Y.; Zhou, T.; et al. The Y chromosome sequence of the channel catfish suggests novel sex determination mechanisms in teleost fish. BMC Biol. 2019, 17, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Zhou, T.; Liu, Y.; Tian, C.; Bao, L.; Wang, W.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, S.; Shi, H.; Tan, S.; et al. Identification of an Epigenetically Marked Locus within the Sex Determination Region of Channel Catfish. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 5471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Wang, W.; Yang, Y.; Yang, Y.; Tan, S.; Tan, S.; Zhou, T.; Zhou, T.; Liu, Y.; Liu, Y.; et al. Genomic imprinting-like monoallelic paternal expression determines sex of channel catfish. Sci. Adv. 2022, 8, adc8786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metzger, D.C.H.; Schulte, P.M. The DNA Methylation Landscape of Stickleback Reveals Patterns of Sex Chromosome Evolution and Effects of Environmental Salinity. Genome Biol. Evol. 2018, 10, 775–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metzger, D.; Mank, J.E. Conserved sex-biased DNA methylation patterns target key developmental genes and non-recombining region of the guppy sex chromosome. BioRxiv 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melamed-Bessudo, C.; Levy, A.A. Deficiency in DNA methylation increases meiotic crossover rates in euchromatic but not in heterochromatic regions in Arabidopsis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2012, 109, E981–E988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yelina, N.E.; Lambing, C.; Hardcastle, T.J.; Zhao, X.; Santos, B.; Henderson, I.R. DNA methylation epigenetically silences crossover hot spots and controls chromosomal domains of meiotic recombination in Arabidopsis. Genes Dev. 2015, 29, 2183–2202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Z.; Gao, D. Hydin as the Candidate Master Sex Determination Gene in Channel Catfish (Ictalurus punctatus) and Its Epigenetic Regulation. Mar. Biotechnol. 2024, 27, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, D.; Yang, H.; Li, M.; Shi, H.; Zhang, X.; Wang, D. gsdf is a downstream gene of dmrt1 that functions in the male sex determination pathway of the Nile tilapia. Mol. Reprod. Dev. 2016, 83, 497–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, M.-H.; Yang, H.-H.; Li, M.-R.; Sun, Y.-L.; Jiang, X.-L.; Xie, Q.-P.; Wang, T.-R.; Shi, H.-J.; Sun, L.-N.; Zhou, L.-Y.; et al. Antagonistic Roles of Dmrt1 and Foxl2 in Sex Differentiation via Estrogen Production in Tilapia as Demonstrated by TALENs. Endocrinology 2013, 154, 4814–4825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Li, M.; Ma, H.; Liu, X.; Shi, H.; Li, M.; Wang, D. Mutation of foxl2 or cyp19a1a results in female to male sex reversal in XX Nile tilapia. Endocrinology 2017, 158, 2634–2647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, L.C.; Ortí, G.; Huang, Y.; Sun, Y.; Baldwin, C.C.; Thompson, A.W.; Arcila, D.; Betancur-R, R.; Li, C.; Becker, L.; et al. Comprehensive phylogeny of ray-finned fishes (Actinopterygii) based on transcriptomic and genomic data. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2018, 115, 6249–6254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nanda, I.; Kondo, M.; Hornung, U.; Asakawa, S.; Winkler, C.; Shimizu, A.; Shan, Z.; Haaf, T.; Shimizu, N.; Shima, A.; et al. A duplicated copy of DMRT1 in the sex-determining region of the Y chromosome of the medaka, Oryzias latipes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2002, 99, 11778–11783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myosho, T.; Takehana, Y.; Hamaguchi, S.; Sakaizumi, M. Turnover of Sex Chromosomes in Celebensis Group Medaka Fishes. G3 Genes|Genomes|Genetics 2015, 5, 2685–2691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mustapha, U.F.; Jiang, D.-N.; Liang, Z.-H.; Gu, H.-T.; Yang, W.; Chen, H.-P.; Deng, S.-P.; Wu, T.-L.; Tian, C.-X.; Zhu, C.-H.; et al. Male-specific Dmrt1 is a candidate sex determination gene in spotted scat (Scatophagus argus). Aquaculture 2018, 495, 351–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, D.-N.; Huang, Y.-Q.; Zhang, J.-M.; Mustapha, U.F.; Peng, Y.-X.; Huang, H.; Li, G.-L. Establishment of the Y-linked Dmrt1Y as the candidate sex determination gene in spotbanded scat (Selenotoca multifasciata). Aquaculture 2020, 23, 101085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Sun, F.; Wan, Z.Y.; Yang, Z.; Tay, Y.X.; Lee, M.; Ye, B.; Wen, Y.; Meng, Z.; Fan, B.; et al. Transposon-induced epigenetic silencing in the X chromosome as a novel form of dmrt1 expression regulation during sex determination in the fighting fish. BMC Biol. 2022, 20, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, S.; Song, C.; Han, F.; He, Q.; Liu, J.; Zhang, S.; Han, W.; Ye, K.; Han, Z.; Wang, Z.; et al. Study on sex-linked region and sex determination candidate gene using a high-quality genome assembly in yellow drum. Aquaculture 2022, 563, 738987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, M.; Zou, Y.; Xiao, S.; Li, W.; Han, Z.; Han, F.; Xiao, J.; Liu, F.; Wang, Z. Chromosome assembly of Collichthys lucidus, a fish of Sciaenidae with a multiple sex chromosome system. Sci. Data 2019, 6, 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Y.; Wang, W.; Ma, L.; Jie, J.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, H.; Li, H. New locus reveals the genetic architecture of sex reversal in the Chinese tongue sole (Cynoglossus semilaevis). Heredity 2018, 121, 319–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, A.; Xiao, S.; Xu, S.; Ye, K.; Lin, X.; Sun, S.; Wang, Z. Identification of a male-specific DNA marker in the large yellow croaker (Larimichthys crocea). Aquaculture 2017, 480, 116–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez, P.; Robledo, D.; Taboada, X.; Blanco, A.; Moser, M.; Maroso, F.; Hermida, M.; Gómez-Tato, A.; Álvarez-Blázquez, B.; Cabaleiro, S.; et al. A genome-wide association study, supported by a new chromosome-level genome assembly, suggests sox2 as a main driver of the undifferentiatiated ZZ/ZW sex determination of turbot (Scophthalmus maximus). Genomics 2021, 113, 1705–1718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takehana, Y.; Matsuda, M.; Myosho, T.; Suster, M.L.; Kawakami, K.; Shin-I, T.; Kohara, Y.; Kuroki, Y.; Toyoda, A.; Fujiyama, A.; et al. Co-option of Sox3 as the male-determining factor on the Y chromosome in the fish Oryzias dancena. Nat. Commun. 2014, 5, 4157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Q.; Feron, R.; Yano, A.; Guyomard, R.; Jouanno, E.; Vigouroux, E.; Wen, M.; Busnel, J.-M.; Bobe, J.; Concordet, J.-P.; et al. Identification of the master sex determining gene in Northern pike (Esox lucius) reveals restricted sex chromosome differentiation. PLOS Genet. 2019, 15, e1008013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hattori, R.S.; Kumazawa, K.; Nakamoto, M.; Nakano, Y.; Yamaguchi, T.; Kitano, T.; Yamamoto, E.; Fuji, K.; Sakamoto, T. Y-specific amh allele, amhy, is the master sex-determining gene in Japanese flounder Paralichthys olivaceus. Front. Genet. 2022, 13, 1007548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hattori, R.S.; Murai, Y.; Oura, M.; Masuda, S.; Majhi, S.K.; Sakamoto, T.; Fernandino, J.I; Somoza, G.M.; Yokota, M.; Strüssmann, C.A. A Y-linked anti-Mullerian hormone duplication takes over a critical role in sex determination. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 109, 2955–2959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hattori, R.S.; Somoza, G.M.; Fernandino, J.I.; Colautti, D.C.; Miyoshi, K.; Gong, Z.; Yamamoto, Y.; Strüssmann, C.A. The Duplicated Y-specific amhy Gene Is Conserved and Linked to Maleness in Silversides of the Genus Odontesthes. Genes 2019, 10, 679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamamoto, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Sarida, M.; Hattori, R.S.; Strüssmann, C.A. Coexistence of Genotypic and Temperature-Dependent Sex Determination in Pejerrey Odontesthes bonariensis. PLOS ONE 2014, 9, e102574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bej, D.K.; Miyoshi, K.; Hattori, R.S.; A Strüssmann, C.; Yamamoto, Y. A Duplicated, Truncated amh Gene Is Involved in Male Sex Determination in an Old World Silverside. G3 Genes|Genomes|Genetics 2017, 7, 2489–2495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curzon, A.Y.; Shirak, A.; Dor, L.; Zak, T.; Perelberg, A.; Seroussi, E.; Ron, M. A duplication of the Anti-Müllerian hormone gene is associated with genetic sex determination of different Oreochromis niloticus strains. Heredity 2020, 125, 317–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M. Li et al., A Tandem Duplicate of Anti-Müllerian Hormone with a Missense SNP on the Y Chromosome Is Essential for Male Sex Determination in Nile Tilapia, Oreochromis niloticus. PLOS Genetics 2015, 11, e1005678. [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Dai, S.; Wu, J.; Wei, X.; Zhou, X.; Chen, M.; Tan, D.; Pu, D.; Li, M.; Wang, D. Roles of anti-Müllerian hormone and its duplicates in sex determination and germ cell proliferation of Nile tilapia. Genetics 2021, 220, iyab237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansai, S.; Montenegro, J.; Masengi, K.W.A.; Nagano, A.J.; Yamahira, K.; Kitano, J. Diversity of sex chromosomes in Sulawesian medaka fishes. J. Evol. Biol. 2022, 35, 1751–1764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, W.; Xie, Y.; Sun, M.; Li, X.; Fitzpatrick, C.K.; Vaux, F.; O'Malley, K.G.; Zhang, Q.; Qi, J.; He, Y. A duplicated amh is the master sex-determining gene for Sebastes rockfish in the Northwest Pacific. Open Biol. 2021, 11, 210063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sardell, J.M.; Josephson, M.P.; Dalziel, A.C.; Peichel, C.L.; Kirkpatrick, M. Heterogeneous Histories of Recombination Suppression on Stickleback Sex Chromosomes. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2021, 38, 4403–4418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeffries, D.L.; Mee, J.A.; Peichel, C.L. Identification of a candidate sex determination gene in Culaea inconstans suggests convergent recruitment of an Amh duplicate in two lineages of stickleback. J. Evol. Biol. 2022, 35, 1683–1695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holborn, M.K.; Einfeldt, A.L.; Kess, T.; Duffy, S.J.; Messmer, A.M.; Langille, B.L.; Brachmann, M.K.; Gauthier, J.; Bentzen, P.; Knutsen, T.M.; et al. Reference genome of lumpfish Cyclopterus lumpus Linnaeus provides evidence of male heterogametic sex determination through the AMH pathway. Mol. Ecol. Resour. 2021, 22, 1427–1439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rondeau, E.B.; Laurie, C.V.; Johnson, S.C.; Koop, B.F. A PCR assay detects a male-specific duplicated copy of Anti-Müllerian hormone (amh) in the lingcod (Ophiodon elongatus). BMC Res. Notes 2016, 9, 230–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakamoto, M.; Uchino, T.; Koshimizu, E.; Kuchiishi, Y.; Sekiguchi, R.; Wang, L.; Sudo, R.; Endo, M.; Guiguen, Y.; Schartl, M.; et al. A Y-linked anti-Müllerian hormone type-II receptor is the sex-determining gene in ayu, Plecoglossus altivelis. PLOS Genet. 2021, 17, e1009705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, M.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Wan, S.; Ravi, V.; Qin, G.; Jiang, H.; Wang, X.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, B.; et al. Seadragon genome analysis provides insights into its phenotype and sex determination locus. Sci. Adv. 2021, 7, abg5196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nacif, C.L.; Kratochwil, C.F.; Kautt, A.F.; Nater, A.; Machado-Schiaffino, G.; Meyer, A.; Henning, F. Molecular parallelism in the evolution of a master sex-determining role for the anti-Mullerian hormone receptor 2 gene (amhr2) in Midas cichlids. Mol. Ecol. 2022, 32, 1398–1410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feron, R.; Zahm, M.; Cabau, C.; Klopp, C.; Roques, C.; Bouchez, O.; Eché, C.; Valière, S.; Donnadieu, C.; Haffray, P.; et al. Characterization of a Y-specific duplication/insertion of the anti-Mullerian hormone type II receptor gene based on a chromosome-scale genome assembly of yellow perch, Perca flavescens. Mol. Ecol. Resour. 2020, 20, 531–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuhl, H.; Euclide, P.T.; Klopp, C.; Cabau, C.; Zahm, M.; Lopez-Roques, C.; Iampietro, C.; Kuchly, C.; Donnadieu, C.; Feron, R.; et al. Multi-genome comparisons reveal gain-and-loss evolution of anti-Mullerian hormone receptor type 2 as a candidate master sex-determining gene in Percidae. BMC Biol. 2024, 22, 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamiya, T.; Kai, W.; Tasumi, S.; Oka, A.; Matsunaga, T.; Mizuno, N.; Fujita, M.; Suetake, H.; Suzuki, S.; Hosoya, S.; et al. A Trans-Species Missense SNP in Amhr2 Is Associated with Sex Determination in the Tiger Pufferfish, Takifugu rubripes (Fugu). PLOS Genet. 2012, 8, e1002798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabir, A.; Ieda, R.; Hosoya, S.; Fujikawa, D.; Atsumi, K.; Tajima, S.; Nozawa, A.; Koyama, T.; Hirase, S.; Nakamura, O.; et al. Repeated translocation of a supergene underlying rapid sex chromosome turnover in Takifugu pufferfish. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2022, 119, e2121469119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Imarazene, B.; Du, K.; Beille, S.; Jouanno, E.; Feron, R.; Pan, Q.; Torres-Paz, J.; Lopez-Roques, C.; Castinel, A.; Gil, L.; et al. A supernumerary “B-sex” chromosome drives male sex determination in the Pachón cavefish, Astyanax mexicanus. Curr. Biol. 2021, 31, 4800–4809.e9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Richter, *!!! REPLACE !!!*; et al. , The TGF-β family member Gdf6Y determines the male sex in Nothobranchius furzeri by suppressing oogenesis-inducing genes. bioRxiv 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myosho, T.; Otake, H.; Masuyama, H.; Matsuda, M.; Kuroki, Y.; Fujiyama, A.; Naruse, K.; Hamaguchi, S.; Sakaizumi, M. Tracing the Emergence of a Novel Sex-Determining Gene in Medaka,Oryzias luzonensis. Genetics 2012, 191, 163–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaneko, H.; Ijiri, S.; Kobayashi, T.; Izumi, H.; Kuramochi, Y.; Wang, D.-S.; Mizuno, S.; Nagahama, Y. Gonadal soma-derived factor (gsdf), a TGF-beta superfamily gene, induces testis differentiation in the teleost fish Oreochromis niloticus. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 2015, 415, 87–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herpin, A.; Schartl, M.; Depincé, A.; Guiguen, Y.; Bobe, J.; Hua-Van, A.; Hayman, E.S.; Octavera, A.; Yoshizaki, G.; Nichols, K.M.; et al. Allelic diversification after transposable element exaptation promotedgsdfas the master sex determining gene of sablefish. Genome Res. 2021, 31, 1366–1380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edvardsen, R.B.; Wallerman, O.; Furmanek, T.; Kleppe, L.; Jern, P.; Wallberg, A.; Kjærner-Semb, E.; Mæhle, S.; Olausson, S.K.; Sundström, E.; et al. Heterochiasmy and the establishment of gsdf as a novel sex determining gene in Atlantic halibut. PLOS Genet. 2022, 18, e1010011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jasonowicz, A.J.; Simeon, A.; Zahm, M.; Cabau, C.; Klopp, C.; Roques, C.; Iampietro, C.; Lluch, J.; Donnadieu, C.; Parrinello, H.; et al. Generation of a chromosome-level genome assembly for Pacific halibut (Hippoglossus stenolepis) and characterization of its sex-determining genomic region. Mol. Ecol. Resour. 2022, 22, 2685–2700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rafati, N.; Chen, J.; Herpin, A.; Pettersson, M.E.; Han, F.; Feng, C.; Wallerman, O.; Rubin, C.-J.; Péron, S.; Cocco, A.; et al. Reconstruction of the birth of a male sex chromosome present in Atlantic herring. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2020, 117, 24359–24368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curzon, A.Y.; Dor, L.; Shirak, A.; Meiri-Ashkenazi, I.; Rosenfeld, H.; Ron, M.; Seroussi, E. A novel c.1759T>G variant in follicle-stimulating hormone-receptor gene is concordant with male determination in the flathead grey mullet (Mugil cephalus). G3 Genes|Genomes|Genetics 2020, 11, jkaa044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de la Herrán, R.; Hermida, M.; Rubiolo, J.A.; Gómez-Garrido, J.; Cruz, F.; Robles, F.; Navajas-Pérez, R.; Blanco, A.; Villamayor, P.R.; Torres, D.; et al. A chromosome-level genome assembly enables the identification of the follicule stimulating hormone receptor as the master sex-determining gene in the flatfish Solea senegalensis. Mol. Ecol. Resour. 2023, 23, 886–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koyama, T.; Nakamoto, M.; Morishima, K.; Yamashita, R.; Yamashita, T.; Sasaki, K.; Kuruma, Y.; Mizuno, N.; Suzuki, M.; Okada, Y.; et al. A SNP in a Steroidogenic Enzyme Is Associated with Phenotypic Sex in Seriola Fishes. Curr. Biol. 2019, 29, 1901–1909.e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purcell, C.M.; Seetharam, A.S.; Snodgrass, O.; Ortega-García, S.; Hyde, J.R.; Severin, A.J. Insights into teleost sex determination from the Seriola dorsalis genome assembly. BMC Genom. 2018, 19, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, B.; Xie, D.; Li, Y.; Wang, X.; Qi, X.; Li, S.; Meng, Z.; Chen, X.; Peng, J.; Yang, Y.; et al. A single intronic single nucleotide polymorphism in splicing site of steroidogenic enzyme hsd17b1 is associated with phenotypic sex in oyster pompano, Trachinotus anak. Proc. R. Soc. B: Biol. Sci. 2021, 288, 20212245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catanach, A.; Ruigrok, M.; Bowatte, D.; Davy, M.; Storey, R.; Valenza-Troubat, N.; López-Girona, E.; Hilario, E.; Wylie, M.J.; Chagné, D.; et al. The genome of New Zealand trevally (Carangidae: Pseudocaranx georgianus) uncovers a XY sex determination locus. BMC Genom. 2021, 22, 785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakamura, Y.; Higuchi, K.; Kumon, K.; Yasuike, M.; Takashi, T.; Gen, K.; Fujiwara, A. Prediction of the Sex-Associated Genomic Region in Tunas (Thunnus Fishes). Int. J. Genom. 2021, 2021, 7226353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, X.; Hu, J.; Yáñez, J.M.; Gomes, G.B.; Poon, Z.W.J.; Foster, D.; Alarcon, J.F.; Shao, L.; Guo, X.; Shao, Y.; et al. Exploring the cobia (Rachycentron canadum) genome: unveiling putative male heterogametic regions and identification of sex-specific markers. GigaScience 2024, 13, giae034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tao, W.; Xu, L.; Zhao, L.; Zhu, Z.; Wu, X.; Min, Q.; Wang, D.; Zhou, Q. High-quality chromosome-level genomes of two tilapia species reveal their evolution of repeat sequences and sex chromosomes. Mol. Ecol. Resour. 2020, 21, 543–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curzon, A.Y.; Shirak, A.; Benet-Perlberg, A.; Naor, A.; Low-Tanne, S.I.; Sharkawi, H.; Ron, M.; Seroussi, E. Gene Variant of Barrier to Autointegration Factor 2 (Banf2w) Is Concordant with Female Determination in Cichlids. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 7073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behrens, K.A.; Koblmüller, S.; Kocher, T.D. Genome assemblies for Chromidotilapia guntheri (Teleostei: Cichlidae) identify a novel candidate gene for vertebrate sex determination, RIN3. Front. Genet. 2024, 15, 1447628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirubakaran, T.G.; Andersen, Ø.; De Rosa, M.C.; Andersstuen, T.; Hallan, K.; Kent, M.P.; Lien, S. Characterization of a male specific region containing a candidate sex determining gene in Atlantic cod. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dan, C.; Lin, Q.; Gong, G.; Yang, T.; Xiong, S.; Xiong, Y.; Huang, P.; Gui, J.-F.; Mei, J. A novel PDZ domain-containing gene is essential for male sex differentiation and maintenance in yellow catfish (Pelteobagrus fulvidraco). Sci. Bull. 2018, 63, 1420–1430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, C.; Liu, H.; Pan, Z.; Cheng, L.; Sun, Y.; Wang, H.; Chang, G.; Wu, N.; Ding, H.; Zhao, H.; et al. Insights into chromosomal evolution and sex determination of Pseudobagrus ussuriensis (Bagridae, Siluriformes) based on a chromosome-level genome. DNA Res. 2022, 29, dsac028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xue, L.; Gao, Y.; Wu, M.; Tian, T.; Fan, H.; Huang, Y.; Huang, Z.; Li, D.; Xu, L. Telomere-to-telomere assembly of a fish Y chromosome reveals the origin of a young sex chromosome pair. Genome Biol. 2021, 22, 203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A Kottler, V.; Feron, R.; Nanda, I.; Klopp, C.; Du, K.; Kneitz, S.; Helmprobst, F.; Lamatsch, D.K.; Lopez-Roques, C.; Lluch, J.; et al. Independent Origin of XY and ZW Sex Determination Mechanisms in Mosquitofish Sister Species. Genetics 2020, 214, 193–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Q.; Feron, R.; Jouanno, E.; Darras, H.; Herpin, A.; Koop, B.; Rondeau, E.; Goetz, F.W.; A Larson, W.; Bernatchez, L.; et al. The rise and fall of the ancient northern pike master sex-determining gene. eLife 2021, 10, e62858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Gao, D.; Su, B.; Dunham, R.; Liu, Z. Transcriptome analyses suggest distinct master sex determination genes in closely related blue catfish and channel catfish. Aquaculture 2025, 603, 742364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

| MSD gene | Order or major groups | Common name | Species | MSD gene acquisition | Karyotype | Functional validation | Sex system | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Teleost fish | ||||||||

| Dmrt1 | Beloniformes | Japanese medaka | Oryzias latipes | Allelic | Ho | Natural mutation | XY | [17] |

| Dmrt1 | Beloniformes | Hainan medaka | Oryzias curvinotus | Allelic | Ho | - | XY |

[70] |

| Dmrt1 | Beloniformes | Northern medaka | Oryzias Sakaizumii | Allelic | Ho | - | XY |

[71] |

| Dmrt1 | Beloniformes | Hubbs's medaka | Oryzias hubbsi | Inversion |

Hetero | - | ZW | [38] |

| Dmrt1 | Beloniformes | Javanese ricefish | Oryzias javanicus | Inversion |

Hetero | - | ZW | [38] |

| Dmrt1 | Perciformes | Spotted scat | Scatophagus argus | Allelic | Ho | - | XY | [72] |

| Dmrt1 | Perciformes | Spotbanded scat |

Selenotoca multifasciata | Allelic | Ho | - | XY | [73] |

| Dmrt1 | Perciformes | Siamese fighting fish |

Betta splendens |

Allelic | Ho | - | XY | [74] |

| Dmrt1 | Perciformes | Yellow drum |

Nibea albiflora | Allelic | Ho 10 Mb SDR |

- | XY | [75] |

| Dmrt1 | Perciformes | Bighead croaker | Collichthys lucidus | Chromosome fusion generated Y (male 2n=47) female 2n=48 | Hetero | - | X1X1X2X2/X1X2Y | [76] |

| Dmrt1 | Pleuronectiformes |

Chinese tongue sole | Cynoglossus semilaevis | *Whole chromosome non-recombining but a small PAR | Hetero W larger |

knockout |

ZW |

[31] |

| Dmrt1 | Pleuronectiformes | Genko tongue sole | Cynoglossus interruptus | Allelic | Ho | - | ZW | [77] |

| Dmrt1 | Acanthuriformes | Yellow croaker | Larimichthys crocea | Allelic | Ho | - | XY | [78] |

| sox2 | Pleuronectiformes | Turbot | Scophthalmus maximus | Allelic | Ho | - | ZW | [79] |

| sox3Y | Beloniformes | Dwarf medaka | Oryzias minutillus | Allelic | Ho | Transgenic, knockout | XY | [80] |

| sox3Y | Beloniformes | Marmorated ricefish | Oryzias marmoratus | Allelic | Ho | Transgenic, knockout | XY | [80] |

| sox3Y | Beloniformes | Yellow finned medaka | Oryzias profundicola | Allelic | Ho | Transgenic, knockout | XY | [80] |

| sox3Y | Beloniformes |

Indian ricefish | Oryzias dancena | Allelic | Ho | Transgenic, knockout | XY | [80] |

| Sox7 | Beloniformes |

Celebes ricefish |

Oryzias celebensis |

Allelic | Ho | - | XY |

[71] |

| Sox7 | Beloniformes | Matano ricefish | Oryzias matanensis | Allelic | Ho | - | XY | [71] |

| Sox7 | Beloniformes | Wolasi ricefish | Oryzias wolasi | Allelic | Ho | - | XY | [71] |

| Sox7 | Beloniformes | Daisy's ricefish | Oryzias woworae | Allelic | Ho | - | XY | [71] |

| FIGLA | Cichliformes | Tilapia | Oreochromis niloticus LG1 | Allelic | Ho | - | XY | [20] |

| ptfa1 | Siluiriformes | Chinese longsnout catfish | Leiocassis longirostris | Allelic | Ho | - | XY | [21] |

| amhby | Esociformes | Norther pike | Esox Lucius | Tandem duplication | Ho | - | XY | [81,127] |

| amhby | Esociformes | Southern pike | E. cisalpinus | Tandem duplication | Ho | - | XY | [81] |

| amhby | Esociformes | Amur Pike | E. reichertii | Tandem duplication | Ho | - | XY | [81] |

| amhby | Esociformes | Muskellunge | E. masquinongy | Tandem duplication | Ho | - | XY | [81] |

| amhby | Esociformes | Chain pickerel | E. niger | Tandem duplication | Ho | - | XY | [81] |

| amhby | Esociformes | Olympic mudminnow | Novumbra hubbsi | Tandem duplication | Ho | - | XY | [81] |

| amhby | Pleuronectiformes | Olive flounder | Paralichthys olivaceus | Duplication and transposition | Ho | - | XY | [82] |

| amhY | Atheriniformes | Patagonian pejerrey | Odontesthes hatcheri | Duplication and transposition | Ho | Knockdown | XY | [83] |

| amhY | Atheriniformes | Silversides | Odontesthes argentinensis | Duplication and transposition | Ho | - | XY | [84] |

| amhY | Atheriniformes | Silversides | Odontesthes nigricans | Duplication and transposition | Ho | - | XY | [84] |

| amhY | Atheriniformes | Silversides | Odontesthes piquava | Duplication and transposition | Ho | - | XY | [84] |

| amhY | Atheriniformes | Silversides | Odontesthes incisa | Duplication and transposition | Ho | - | XY | [84] |

| amhY | Atheriniformes | Silversides | Odontesthes smitti | Duplication and transposition | Ho | - | XY | [84] |

| amhY | Atheriniformes | Silversides | Odontesthes humensis | Duplication and transposition | Ho | - | XY | [84] |

| amhY | Atheriniformes | Silversides | Odontesthes regia | Duplication and transposition | Ho | - | XY | [84] |

| amhY | Atheriniformes | Silversides | Odontesthes mauleanum | Duplication and transposition | Ho | - | XY | [84] |

| amhY | Atheriniformes | Silversides | Odontesthes perugiae | Duplication and transposition | Ho | - | XY | [84] |

| amhY | Atheriniformes | Pejerrey | Odontesthes bonariensis | Duplication and transposition | Ho | XY | [85] | |

| amhY | Atheriniformes | Cobaltcap silverside | Hypoatherina tsurugae | Truncated duplication on Y | Ho | - | XY | [86] |

| amhY | Cichliformes |

Nile tilapia |

Oreochromis niloticus |

Tandem duplication |

Ho | - |

XY Chr23 | [87,88,89] |

| amhY | Beloniformes | Sulawesian meedaka | Oryzias eversi | Allelic | Ho | - | [90] | |

| amhY | Perciformes |

Black rockfish |

Sebastes schlegelii |

Duplication and transposition | Ho |

Overexpression | XY | [91] |

| amhY | Perciformes | Korean rockfish | Sebastes koreanus | Duplication and transposition | Ho | - | XY | [91] |

| amhY | Perciformes | Rockfish | Sebastes pachycephalus | Duplication and transposition | Ho | - | XY | [91] |

| amhY | Perciformes | Threespine stickleback | Gasterosteus aculeatus | Inversion | Hetero | - | XY | [32] |

| amhY | Perciformes | Japan Sea stickleback | Gasterosteus nipponicus | Inversion followed by chromosome fusion | Hetero |

- | X1X2Y | [92] |

| amhY | Perciformes | Blackspotted stickleback | Gasterosteus wheatlandi | Inversion followed by chromosome fusion | Hetero |

- | X1X2Y | [92] |

| amhY | Perciformes | Brook stickleback | Culaea inconstans | Duplication on Y | Ho | - | XY | [93] |

| amhY | Perciformes | Common lumpfish | Cyclopterus lumpus | Duplication on Y | Ho | - | XY | [94] |

| amhY | Perciformes | Lingcod | Ophiodon elongatus | Duplication on Y | Ho | - | XY | [95] |

| amhY | Siluriformes | Southern catfish | Silurus meridionalis | Transposition | Ho 2.38 Mb SDR |

- | XY | [40] |

| Amhr2Y | Siluriformes | Amur catfish | Silurus asotus | Transposition | Ho 400 Kb SDR |

- | XY | [41] |

| amhr2y | Siluriformes | Lanzhou catfish | Silurus lanzhouensis | Transposition | Ho 400 Kb SDR |

- | XY | [42] |

| Amhr2Y | Siluriformes | Pangasiidae catfishes | Pangasianodon hypophthalmus | Transposition | Ho 320 Kb SDR |

- | XY | [39] |

| Amhr2Y | Siluriformes | Pangasiidae catfishes | Pangasius djambal | Transposition | Ho 320 Kb SDR |

- | XY | [39] |

| Amhr2Y | Siluriformes | Pangasiidae catfishes | Pangasianodon gigas | Transposition | Ho 320 Kb SDR |

- | XY | [39] |

| Amhr2Y | Siluriformes | Pangasiidae catfishes | Pangasius bocourti | Transposition | Ho 320 Kb SDR |

- | XY | [39] |

| Amhr2Y | Siluriformes | Pangasiidae catfishes | Pangasius conchophilus | Transposition | Ho 320 Kb SDR |

- | XY | [39] |

| Amhr2Y | Siluriformes | Pangasiidae catfishes | Pangasius elongatus | Transposition | Ho 320 Kb SDR |

- | XY | [39] |

| Amhr2Y | Siluriformes | Pangasiidae catfishes | Pangasius siamensis | Transposition | Ho 320 Kb SDR |

- | XY | [39] |

| Amhr2Y | Siluriformes | Pangasiidae catfishes | Pangasius macronema | Transposition | Ho 320 Kb SDR |

- | XY | [39] |

| Amhr2Y | Siluriformes | Pangasiidae catfishes | Pangasius larnaudii | Transposition | Ho 320 Kb SDR |

- | XY | [39] |

| Amhr2Y | Siluriformes | Pangasiidae catfishes | Pangasius mekongensis | Transposition | Ho 320 Kb SDR |

- | XY | [39] |

| Amhr2Y | Siluriformes | Pangasiidae catfishes | Pangasius krempfi | Transposition | Ho 320 Kb SDR |

- | XY | [39] |

| Amhr2Y | Siluriformes | Pangasiidae catfishes | Pangasius sanitwongsei | Transposition | Ho 320 Kb SDR |

- | XY | [39] |

| amhr2Y | Osmeriformes | Ayu | Plecoglossus altivelis | Duplication and translocation | Ho 2.03 Mb SDR |

Knockout | XY | [96] |

| amhr2Y | Syngnathiformes | Common seadragon | Phyllopteryx taeniolatus | Truncated duplication and transposition | Ho | - | XY | [97] |

| amhr2Y | Syngnathiformes | Alligator pipefish | Syngnathoides biaculeatus | Truncated duplication and transposition | Ho | - | XY | [97] |

| amhr2Y | Cichliformes | Midas Cichlids | Amphilophus amarillo | Duplication and transposition | Ho | - | XY | [98] |

| amhr2Y | Cichliformes | Midas Cichlids | Amphilophus astorquii | Duplication and transposition | Ho | - | XY | [98] |

| amhr2Y | Cichliformes | Midas Cichlids | Amphilophus chancbo | Duplication and transposition | Ho | - | XY | [98] |

| amhr2Y | Cichliformes | Midas Cichlids | Amphilophus citrinellus | Duplication and transposition | Ho | - | XY | [98] |

| amhr2Y | Cichliformes | Midas Cichlids | Amphilophus flaveolus | Duplication and transposition | Ho | - | XY | [98] |

| amhr2Y | Cichliformes | Midas Cichlids | Amphilophus globosus | Duplication and transposition | Ho | - | XY | [98] |

| amhr2Y | Cichliformes | Midas Cichlids | Amphilophus labiatus | Duplication and transposition | Ho | - | XY | [98] |

| amhr2Y | Cichliformes | Midas Cichlids | Amphilophus sagittae | Duplication and transposition | Ho | - | XY | [98] |

| amhr2Y | Cichliformes | Midas Cichlids | Amphilophus tolteca | Duplication and transposition | Ho | - | XY | [98] |

| amhr2Y | Cichliformes | Midas Cichlids | Amphilophus viridis | Duplication and transposition | Ho | - | XY | [98] |

| amhr2Y | Cichliformes | Midas Cichlids | Amphilophus xiloaensis | Duplication and transposition | Ho | - | XY | [98] |

| amhr2Y | Cichliformes | Midas Cichlids | Amphilophus zaliosus | Duplication and transposition | Ho | - | XY | [98] |

| amhr2Y | Perciformes | Yellow perch | Perca flavescens | Allelic | Ho | - | XY | [99] |

| amhr2Y | Perciformes | Balkhash perch | Perca schrenkii | Allelic | Ho | - | XY | [100] |

| amhr2Y | Perciformes | Walleye | Sander vitreus | Allelic | Ho | - | XY | [100] |

| amhr2Y | Tetraodontiformes | Pufferfish | Takifugu rubripes | Allelic | Ho | - | XY | [101] |

| amhr2Y | Tetraodontiformes | Pufferfish | Takifugu obscurus | Allelic | Ho | - | XY | [102] |

| amhr2Y | Tetraodontiformes | Pufferfish | Takifugu ocellatus | Allelic | Ho | - | XY | [102] |

| amhr2Y | Tetraodontiformes | Pufferfish | Takifugu xanthopterus | Allelic | Ho | - | XY | [102] |

| amhr2Y | Tetraodontiformes | Pufferfish | Takifugu stictonotus | Allelic | Ho | - | XY | [102] |

| amhr2Y | Tetraodontiformes | Pufferfish | Takifugu porphyreus | Allelic | Ho | - | XY | [102] |

| amhr2Y | Tetraodontiformes | Pufferfish | Takifugu poecilonotus | Allelic | Ho | - | XY | [102] |

| amhr2Y | Tetraodontiformes | Pufferfish | Takifugu chrysops | Allelic | Ho | - | XY | [102] |

| amhr2Y | Tetraodontiformes | Pufferfish | Takifugu pardalis | Allelic | Ho | - | XY | [102] |

| amhr2Y | Characiformes | blind cave fish | Astyanax mexicanus | B chromosomes | B chr | Knockout | B chr | [103] |

| gdf6bB | Cyprinodontiformes | African killifish | Nothobranchius furzeri | Allelic | - | Knockout | XY | [104] |

| gdf6bY | Beloniformes | Philippine Medaka | Oryzias luzonensis | Allelic | Ho | Transgenic | XY | [105] |

| gsdfY | Cichliformes | Tilapia | Oreochromis niloticus | Allelic | Ho | Transgenic | XY | [106] |

| gsdfY | Perciformes | Sablefish | Anoplopoma fimbria | Allelic | Ho | - | XY | [107] |

| gsdfY | Pleuronectiformes | Atlantic halibut | Hippoglossus hippoglossus | Allelic | Ho 11.6 Mb SDR |

- | XY Chr12 | [108] |

| gsdfY | Tetraodontiformes | Pufferfish | Takifugu niphobles | Transposition | Ho | XY | [102] | |

| gsdfY | Tetraodontiformes | Pufferfish | Takifugu snyderi | Transposition | Ho | XY | [102] | |

| gsdfY | Tetraodontiformes | Pufferfish | Takifugu vermicularis | Transposition | Ho | XY | [102] | |

| bmpr1ba | Pleuronectiformes | Pacific halibut | Hippoglossus stenolepis | Inversion compared to Chr9 of Atlantic halibut | Ho 12 Mb SDR |

- | ZW Chr9 | [109] |

| bmpr1bbY | Clupeiformes | Atlantic herring | Clupea harengus | Allelic | Ho | - | XY Chr8 | [110] |

| fshrY | Mugiliformes | Flathead grey mullet | Mugil cephalus | Allelic | Ho | - | XY | [111] |

| fshrY | Pleuronectiformes | Senegalese sole | Solea senegalensis | Allelic | Ho | - | XY | [112] |

| Hsd17b1 | Carangiformes | Yellowtail amberjack | Seriola lalandi | Allelic | Ho | - | ZW | [113] |

| Hsd17b1 | Carangiformes | Greater amberjack | Seriola dumerili | Allelic | Ho | - | ZW | [113] |

| Hsd17b1 | Carangiformes | Japanese yellowtail | Seriola quinqueradiata | Allelic | Ho | - | ZW | [113] |

| Hsd17b1 | Carangiformes | California yellowtail | Seriola dorsalis | Allelic | Ho | - | ZW | [114] |

| Hsd17b1 | Carangiformes | Oyster pompano | Trachinotus anak | Allelic | Ho | - | ZW | [115] |

| Cyp19a1 | Carangiformes | Silver trevally | Pseudocaranx georgianus | Allelic | Ho | - | XY | [116] |

| Hsdl1 or Tbc1d32 | Perciformes | European perch | Perca fluviatilis | Allelic | Ho | - | XY | [100] |

| sult1st6y | Scombriformes | Southern bluefin tuna | Thunnus maccoyii | Allelic | Ho | - | XY | [117] |

| sult1st6y | Scombriformes | Pacific bluefin tuna | Thunnus orientalis | Allelic | Ho | - | XY | [117] |

| cephx1Y | Carangiformes | Cobia | Rachycentron canadum | Allelic | Ho 4.04 Mb SDR |

- | XY | [118] |

| Paics/ banf2W | Cichliformes | Blue tilapia | Oreochromis aureus LG3 | Duplication | Ho | - | ZW | [119,120] |

| Paics/ banf2W | Cichliformes | Tanganyika tilapia | Oreochromis tanganicae | Duplication | Ho | - | ZW | [119,120] |

| Paics/ banf2W | Cichliformes | Wami tilapia | Oreochromis hornorum | Duplication | Ho | - | ZW | [119,120] |

| Paics/ banf2W | Cichliformes | Spotted tilapia | Pelmatolapia mariae | Duplication | Ho | - | ZW | [119,120] |

| RIN3 | Cichliformes | - | Chromidotilapia guntheri | Allelic coding region | Ho | - | XY | [121] |

| zkY | Gadiformes | Atlantic cod | Gadus morhua | Allelic | Ho | - | XY | [122] |

| zkY | Gadiformes | Arctic cod | Arctogadus glacialis | Allelic | Ho | - | XY | [122] |

| zkY | Gadiformes | Pacific cod | Gadus macrocephalus | Allelic | Ho | - | XY | [122] |

| sdY | Salmoniformes | Salmonids |

13 species Salmonids |

Transposition/ translocation |

- |

Transgenic and knockout | XY | [24,25] |

| pfpdz1 | Siluiriformes | Yellow catfish | Pelteobagrus fulvidraco | Chromatin architecture, epigenetic regulation | Ho | Overexpression Knockout |

XY | [44,123] |

| Hydin | Siluiriformes | Channel catfish | Ictalurus punctatus | Epigenetic regulation | Ho 8.9 Mb SDR |

Methylation blocker | XY | [59,60] |

| ? (new comer) | Siluiriformes | Ussuri catfish | Pseudobagrus ussuriensis |

Epigenetic regulation |

Ho 16.83 Mb SDR |

- |

XY |

[124] |

| HMGN6/ CYCE3 | Synbranchiformes | The zig-zag eel | Mastacembelus armatus | Allelic | Ho 7.0 Mb SDR |

- | XY | [125] |

| Gipc PDZ1Y? | Cyprinodontiformes | Eastern mosquitofish | Gambusia holbrooki | - | Ho | - | XY | [126] |

| ? | Cyprinodontiformes | Western mosquitofish | Gambusia affinis | W chr larger, fusion? | Hetero | - | ZW | [126] |

| Mammals | ||||||||

| Sry | Mammals | All mammals | Inversion* | Hetero | Knockout Over expression |

XY | [10] | |

| Birds | ||||||||

| Dmrt1 | Birds | All birds | Inversion* | Hetero | Allelic knockout | ZW | [11] | |

| Reptiles | ||||||||

| ? | Python and Boa snakes | - | - | Hetero | - | ZW | [131] | |

| ? | Amazonian puffing snakes and viper snakes | - | - | Ho | - | XY | [12] | |

| Amphibians | ||||||||

| DM-W | African clawed frog | Xenopus laevis | Allelic | Ho | Transgenic | ZW | [66] | |

| Bod1l | European green toad | Bufo viridis | Allelic | Ho | XY | [13] | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).