1. Introduction

Skin cancer is the most common worldwide cancer. It is divided into melanoma and non-melanoma, with the second being the most common type. There are two types of non-melanoma skin malignancies: squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) and basal cell carcinoma (BCC) [

1]. The worldwide incidence increases each year, having an important impact on the economy, life quality, morbidity and mortality [

2].

Cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma (cSCC) represents 50% of primary skin cancers, and it is caused by an abnormal and uncontrolled proliferation of the keratinocytes [

3]. cSCC is the world's second most common skin cancer [

4]. It is characterized for a high tumor mutational burden and the usual clinical presentations are: patches; plaques; tumors; and erythroderma [

2,

3]. The standard treatment for cSCC is the surgical excursion and nonsurgical therapies if the complete resection is not possible [

5,

6,

7].

Although it is not a current widespread standard of care, immunotherapy has been showing a positive impact in cSCC resection, even more when associated as a neoadjuvant [

9,

10]. An immunotherapy alternative is Cemiplimab (Libtayo®; Regeneron, Tarrytown, New York, United States), which is a PD-1 receptor monoclonal antibody (human IgG4 antibody) that binds to PDL1 receptor [

9]. The overexpression of PDL1 may be a mechanism of resistance in tumor cells, enabling evasion of the immune system through the PD-1/PDL-1 binding [

10]. Moreover, specifically when considering cSCC, one of its immunogenicity patterns is the upregulation of immune checkpoint molecules (PD-1 and PD-L1), which also suggests the efficacy of immunotherapy treatment [

10,

11].

Currently, the use of Cemiplimab is approved by “Food and Drug Administration” (FDA) for the treatment of patients diagnosed with non-small cell lung cancer, for patients with metastatic or locally advanced cSCC, and for BCC patients with locally advanced or metastatic basal cell carcinoma [

12]. In Brazil, the National Health Surveillance Agency” (ANVISA), also recommends the use of this medicine for similar occasions [

13].

Recently, the use of this monoclonal antibody has been explored as a neoadjuvant therapy. Pilot studies have been showing high percentages of complete pathological response after treatment with Cemiplimab as a neoadjuvant. Despite the evidence from the studies mentioned before, the use of Cemiplimab as a neoadjuvant is not widely used in clinical practice. In this context, this review focuses on evaluating the Cemiplimab efficacy in neoadjuvant settings for cSCC, also emphasizing this treatment implications and safety, aiming for better clinical guidance and knowledgement.

2. Materials and Methods

This review was conducted in accordance with PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Item for Systematic Reviews and MetaAnalyses) guidelines. All the reported data were obtained from the available published literature, so institutional review board approval and informed consent were not required. The review protocol was registered on PROSPERO (CRD420250650512).

2.1. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

This systematic review aimed to gather scientific articles on the neoadjuvant use of Cemiplimab in patients with cutaneous SCC.

The literature search strategy used consisted in: population (P), patients diagnosed with cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma; intervention (I), treatment with Cemiplimab in a neoadjuvant setting; comparison (C), none; outcomes (O), the course of the patient after the treatment; study type (S), controlled trials, retrospective cohort studies, systematic reviews, case series. Studies were excluded if (a) they were not available in full-text form, (b) Cemiplimab was not used as a neoadjuvant settings treatment for cSCC, (c) data of patients after the treatment were not extractable, (d) the study reported fewer than five patients, (e) the article type was a conference abstract, case report, or book chapter, or (f) cSCC data presented could not be separated from other tumor types. No restriction on publication date was applied.

2.2. Data Source and Study Search

An electronic search strategy was performed on the following databases: Web of Science, PubMed, and Scopus on December 12, 2024. The search strategy employed was: “Cemiplimab AND (neoadjuvant OR neoadjuvacy) AND (‘basosquamous carcinoma’ OR ‘squamous cell carcinoma’ OR ‘squamous cell cancer" OR “cutaneous squamous cell cancer’).”

2.3. Selection of Studies and Data Extraction

Sources in the form of letters, reports, or formal studies that reported on primary cutaneous SCC treated with Cemiplimab as a neoadjuvant were included. In total, 28 articles were included after a full-text review by two independent reviewers (J.K., M.E.P.) The duplicates were removed using the Systematic Review Management Platform Rayyan. To evaluate eligibility and the articles’ relevance, titles, abstracts, and full text were screened. Discrepancies resolution and verification from the selected articles were executed by the senior author (F.H). Data were archived in an Excel (Microsoft Corp, Seattle, Wash.) spreadsheet. Data collected from the articles included neoadjuvant Cemiplimab response rates; Cemiplimab dosing; efficacy outcomes; study-related adverse effects frequency; Cemiplimab efficacy and safety considerations; and treatment groups limitations. The complete pathologic responses (cPR) - absence of viable tumor (living tumor cells) in the post-treatment surgical specimens - rates data were extracted from the articles, as well as the major pathologic responses (mPR) - ≤ 10% of viable tumor in the post-treatment surgical specimens. For ensuring the scientific rigor development of this systematic review, PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and MetaAnalyses) statement and checklist was used.

2.4. Risk of Bias and Study Quality Assessment

The methodological quality of included studies was assessed independently by two separate authors. Since none of the included Clinical trials were randomized trials, the Methodological Index for Nonrandomized Studies (MINORS) criteria were used to measure study quality.

3. Results

3.1. Electronic Database Search Results

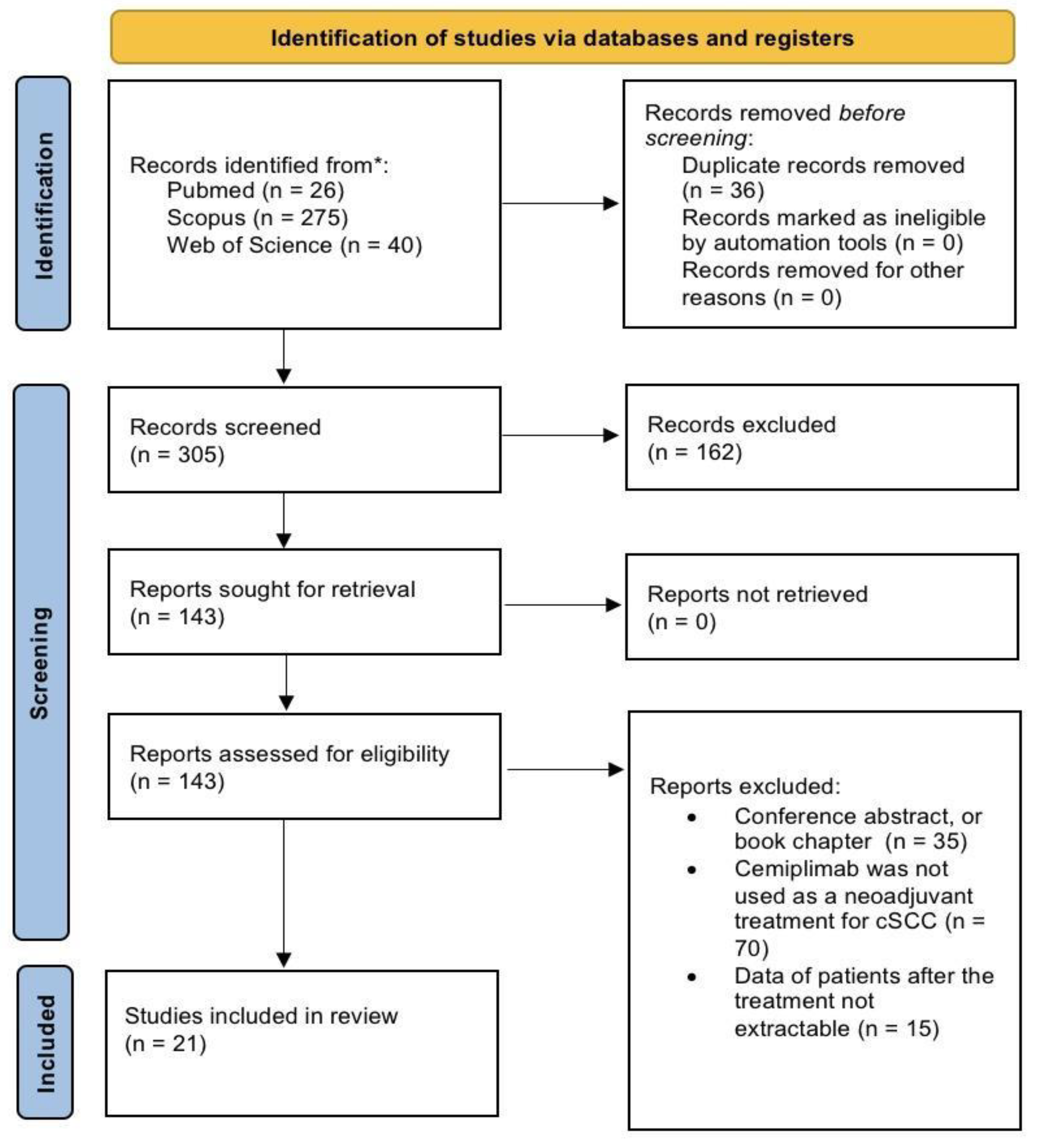

A total of 341 records were identified from the preliminary search. Before screening, 36 duplicates were removed, and after title and abstract screen, 143 articles were sought for retrieval. As a result of the application of the inclusion and exclusion criteria, 21 articles were included in the review [

11,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25,

26,

27,

28,

29,

30,

31,

32,

33]. A flow chart of the study justifying the exclusion reasons and inclusion process is shown in

Figure 1.

3.2. General Features of the Reviewed Clinical Trial

This review discusses the data from six Clinical Trials, two of which are still ongoing. Since this review excluded studies in the format of conference abstracts, the still ongoing Ascierto et al. NEO-CESQ study [

34] and Wong et al. pilot study [

3] couldn't be included in this study. Both data were presented at the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) 2023 annual meeting. Their data will be discussed in this review, despite not being considered included studies. A total of 158 neoadjuvant Cemiplimab treatments were performed for resectable stage II-IV CSCC patients (AJCC-8). The patient’s mean pathologic response rate - that including complete pathologic response (absence of viable tumor in the post-treatment surgical specimens) or major pathological response (≤ 10% viable tumor in the post-treatment surgical specimens) - was 72%. The mean objective response rate was 62%. The patients’ mean treatment-related adverse events (TRAEs) were fatigue, maculopapular rash and diarrhea. The mean rate of patients that presented any TRAE was 66%. The studies’ efficacy data and TRAEs are presented in

Table 1 and

Table 2.

3.3. Risk of Bias Assessment

Out of the 21 included studies, seven were nonrandomized studies. Scores ranged from 8 to 14. The major deficiencies were lack of prospective calculation on study size and exceeding loss of follow-up proportions. All studies adequately reported a clear state aim and an unbiased assessment of the study endpoints. MINORS scores for the included studies are listed in

Appendix A1. (See

Table A1, which displays MINORS scores of the included studies).

3.4. Phase II Trial Data

Six active clinical trials are examining the neoadjuvant treatment of Cemiplimab, which includes two ongoing neoadjuvant trials and two more that explore its use as an adjuvant option. From these studies, Ferraroto et al. [

17] and Gross et al. [

19], showed similar pathological responses of any kind, considering both, complete or major responses (

Table 1). In Ferrarotto et al., 2021 pilot phase II trial , 20 patients with stage II-IVA cSCC received neoadjuvant Cemiplimab [

17]. 11 out of the total had a complete pathologic response (cPR), and 3 of them a major pathologic response (mPR). The 12 months outcomes data showed 95% of disease-specific survival (DSS), 89% of disease-free survival (DFS) and 95% of overall survival [

16]. None of the patients that presented pathological response (cPR + mPR) had recurrence, and there were no treatment-related fatal events (Ferraroto et al., 2021)[

16]. Seven patients experienced treatment-related adverse events (TRAEs), all of which were fully resolved. The most common symptoms reported were pruritus and a maculopapular rash (

Table 2). Another phase 2 nonrandomized study (Gross et al., 2022) [

18] was conducted with stage II-IVA cSCC (AJCC-8) patients who received four 350mg neoadjuvant Cemiplimab IV before resection. Out of the 79 enrolled patients, 70% had some reduction of viable tumor (living tumor cells) in the post-treatment surgical specimens (51% cPR; 13% mPR). Also, from this last mentioned study, none of the responders had recurrence and there was only one patient death suspected to be treatment-related. TRAEs occurred in 57 patients, mainly presenting fatigue, maculopapular rash and diarrhea; 3 of these patients had grade 3 immune-related events (

Table 2). The one and two years of post-surgery follow-up demonstrated favorable outcomes: 89% of 1-year event-free survival (EFS); 85% of 2 years EFS; and 92% of 1-year DFS. In light of the biomarker analyses conducted by D. RISCHIN et al. [

15], an increased clonal abundance and enhanced immunological response throughout T cells was noted in the patients of this study (Gross et al., 2022) [

15,

18]. Both studies concluded that the treatment is a promising option considering the high response rate and outcomes; no new safety signals for Cemiplimab were identified as a neoadjuvant setting.

3.5. High-Risk cSCC Patients Data

Emily Y. Kim et al. [

10], performed a relatively small cohort study that evaluated 27 patients with advanced stage I-IV cSCC (AJCC-8), differently from most clinical trials, 33,3% of the patients in the data presented had a concomitant diagnosis of lymphoma. A third of their treatment group would have been excluded from prior neoadjuvant Cemiplimab clinical trials, possibly leading to differences in the reposted results. The overall pathologic response reported was 47.4% (

Table 1), lower than the rate reported by Ferraroto et al, 2021 [

16,

17], and Gross et al., 2022 trials [

18,

19]. This study's 1-year patient outcomes data was: 83.3% progression-free survival rate; 91.7% of DSS; and the patient’s recurrence-free survival rate was 90.9%. Only one of the responders had recurrence. Overall, Emily Y. Kim et al., 2024 study, supported the previous literature, considering the neoadjuvant Cemiplimab efficacy, but also highlighted the lower responses when considering higher-risk patients [

23]. A case series presented by Goldfarb et al. [

22], also included some high-risk patients. Out of the 6 enrolled patients affected with primary CSCC-HN stage II–IV (AJCC-8), only 4 were able to complete the treatment and undergo periorbital resection. All of them had some pathologic response, 50% had cPR and 50% mPR [

22] (

Table 1).

3.6. Ongoing Clinical Trials

At the 2023 ASCO annual meeting, the data of a NEO-CESQ study was presented [

33]. There were 23 high-risk stage III/IVCSCC-HN (AJCC-8) patients enrolled in this ongoing phase 2 single-arm trial. They received two cycles of neoadjuvant Cemiplimab, and 47% had cPR or mPR pathologic response (

Table 1) and 29 patients had TRAEs (

Table 2). Moreover, activity, data, and results are awaited. Wong et al. also presented at ASCO 2023 the data of another ongoing pilot study [

35]. The recruited patients include I-IV surgically resectable cSCC, and the treatment setting consists of cetuximab loading dose with neoadjuvant Cemiplimab followed by three cycles of chemotherapy (cisplatin or carboplatin + docetaxel) with cetuximab and Cemiplimab prior to definitive surgical. Out of the 10 already enrolled patients, there was 100% of pathologic response, 40% cPR and 60% mPR (

Table 1). To mention the adverse events (

Table 2), the most common were rash, nausea, fatigue and diarrhea; 1 patient experienced severity grade 3, and another one grade 4 (Wong et al., 2023) [

35]. In 2024, 20 new patients were enrolled in this same study, and the data continues to show a high response rate (Dunn et al, 2024) [

36].

4. Discussion

Cutaneous Squamous cell carcinoma (cSCC) is the world's second most common skin cancer. Despite usually having a favorable prognosis, 5% of the patients can develop an advanced cSCC stage [

6]. Patients who present locally advanced forms and metastasis have poor prognosis, with an 89% 5-year mortality due to distant metastasis and a 2 years less expected median survival [

7,

28,

31]. The standard treatment is surgical intervention, but for unresectable situations, irradiation is an option. Systemic therapies can be part of the treatment strategy when surgery or chemotherapy isn’t possible, in situations of advanced or distant metastatic disease [

20]. Commonly, the applied systemic therapies are platinum-based cytotoxic agents and agents targeting the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) [

25]. These traditional methods often lead to disfigurement, functional morbidly, compromised function, limited efficacy, poor tolerability, and potential toxicity. In that way, there is an urgent need for alternative therapeutic strategies to enhance cosmetic results and patient’s quality of life (QoL), providing long live response rates and being safe[

14,

28]. Therefore, different studies have been exploring the use of Cemiplimab in a neoadjuvant setting for cSCC patients.

Cemiplimab neoadjuvant setting is an emergent and promising treatment for cSCC patients, especially when considering recent clinical trials presented data. The traditional methods often lead to physical. The average pathologic response rate data extracted from the evaluated studies was 72%. Gross et al. phase 2 study reported a 70% rate of pathologic response rate (pCR and mPCR) with neoadjuvant anti-PD-1 therapy in solid tumors, which is, until known, really high rates for current neoadjuvant anti-PD-1 therapy results in solid tumors, highlighting Cemiplimab’s efficacy. Also, within the data extracted from 158 trials, there was only one fatal event, possibly treatment-related (Gross et al., 2022)[

18]. Therefore, considering different treatment outcomes from the included literature, neoadjuvant Cemiplimab setting presents high pathologic responses, low treatment-related discontinuation rate, and rare severe study-related adverse effects, thus, supporting its efficacy.

4.1. Immune Implications, Safety and Tolerability

Considering sSCC immunogenicity pattern, and given the high tumor mutational burden, immune checkpoint inhibitors indicate a promising alternative for treating cSCC [

11,

33]. Given this fact, immunotherapy has been explored for sSCC patients and Cemiplimab has already been FDA-approved for locally advanced and metastatic forms [

12]. This drug in adjuvant and neoadjuvant settings has been presenting rapid and durable responses, favorable survival, well toleration, and toxicities occurred in the minority of patients [

27]. In accordance with these considerations, Cemiplimab was referred to by the Italian Association of Medical Oncology as “[…] a curative approach for a disease that lacked a clean standard of care in its advanced stage” [

7]. Another emergent alternative for the current challenging advanced cSCC clinical scenario is neoadjuvant immunotherapy, which already demonstrates favorable pathological responses and positive long-life outcomes. In most included reviews and clinical trials, neoadjuvant Cemiplimab treatment is well tolerated, with no serious adverse events occurring after the treatment [

37]. Resenting a compelling context for neoadjuvant Cemiplimab use for sSCC patients.

Specifically, when exploring the neoadjuvant setting, studies have shown an even higher pathological complete response frequency, cost-effectiveness, and QoL improvement [

14]. Mainly, the included articles showed that the use of Cemiplimab as a neoadjuvant setting allows less invasive surgeries, with better cosmetic and function-preserving outcomes [

16,

17,

23]. Also it is feasible and a success for de-escalation strategies [

14,

18]. Neoadjuvant therapy, when compared to adjuvant therapy alone, allows earlier identification of response and survival biomarkers, and also achieves a broader immune response, as shown by a greater expansion and diversity of anti-tumor T cells [

26]. Immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) adjuvant approaches can cause immunological homeostasis disruption by reactivating cellular immunity, resulting in dysfunctions and other treatment-related adverse events (TRAEs). However, neoadjuvant therapy with ICIs didn’t demonstrate this correlation, indicating a superiority of this setting in safeguarding outcomes [

14]. Other absent phenomenons in adjuvant immunotherapy are the neoadjuvant ICIs' capacity to form effective immune memory to multiple antigens, thereby preventing postoperative immune escape; it also enhances systemic anti-tumor immunity that targets and eliminates distant micrometastases; and increasing of non-hematopoietic cells role [

26,

29]. Furthermore, this treatment approach opens the opportunity for better and earlier analysis of the post-neoadjuvant tumor specimen. This allows for the refinement of long-term clinical outcomes prediction and better guidance of post-surgical therapies to improve patients' pos-treated life quality. In that way, the Cemiplimab as a neoadjuvant setting could contribute to less invasive and disfiguring resections, lower recurrence, better survival and QoL outcomes, also contributing to enhanced tumor-specific immune responses.

ICI treatment can affect the immune system signaling and biomarkers, responses, mechanisms, and molecular pathways in many different ways. Examples of immune modulator effects can be enhanced T cell activation, enhanced T cell tumor infiltration and decreased MDSCs and Tregs within the tumoral microenvironment. A phase 2 clinical trial (Gross et al., 2022 ) [

18] revealed an inflamed tumor immune microenvironment when analyzing pretreatment tumor biological specimens of patients who achieved pathological response after neoadjuvant Cemiplimab therapy for Resectable cSCC [

15,

18]. That suggests that these patients may have memory CD8+ T cells, and also the analyses of CD45RO and EOMES expressions, as drivers of a complete tumor regression [

15,

16,

17]. The 2 years follow-up data from this trial showed increased expression of effector T-cell-related genes and enrichment of T cell activation, interferon-g/a response, and TCR signaling pathways [

15]. Most of this data contrasts with the immune scenario that patients with no pathological response presented. This enhanced systemic activations of tumor-specific and non-specific T cells, is also demonstrated by another pilot phase II study (Ferrarotto et al., 2021)[

16]. A better activation of systemic immune response was observed, since the checkpoint blockade before surgery yields more antigen-specific T cells. Overall, the studies indicate a systemic anti-tumor immunity increase, which positively affects surgical resection, lowers recurrence and increases survival [

14,

29].

4.2. Suitable Treatment Candidates

Immunocompromised patients (human immunodeficiency virus - HIV, hematologic malignancies, advanced solid organ malignancies, solid organ or hematopoietic stem cell transplantations, autoimmune conditions) are considered high risk to develop the advanced form of cSCC. Unfortunately, many of the actual studies do not include immunocompromised patients in their trials due to safety considerations and the high rejection rate [

24]. Recipients of solid organ transplants (SOT) face a risk of developing cSCC that is up to 250 times higher than that of the general population [

31,

32,

33]. It may be challenging for them to be included in trials considering the increased T cell activation after ICI treatment, possibly leading to allograft rejection [

27,

32] . These treatment group exclusion criteria can be considered a barrier to real-world neoadjuvant Cemiplimab efficacy [

40,41]. Another patient group that is also commonly excluded is those diagnosed with hematological malignancies, not only because of rejection rates, but also for presenting lower responses to the treatment [

23]. Overall, about 30 to 40% of all patients have benefited from ICIs [

14], given this information, the identification of suitable candidates is necessary [

37].

4.3. Neoadjuvant Immunotherapy Treatment Considerations

In the context of neoadjuvant immunotherapy treatment (NAIT), it is essential to highlight key information for analyzing the effectiveness of neoadjuvant Cemiplimab. Despite the high responsiveness and the reduced surgical resection, the residual tumor’s boundary and surroundings can be obscured because of the treatment-related associated adhesion, fibrosis, immune cell infiltration and an inflammatory environment [

17,

23]. In addition to the referred obscurement, some of NAIT’s response patterns are responsible for compromising imaging techniques, the predictive biomarkers examination and tumor re-biopsy, then leading to complications at subsequent surgical interventions [

9,

14,

21] .

4.4. Limitations and Future Directions

The main limitations of this study encompass the lack of e patients with severe comorbidities, immunosuppressed, and secondary neoplasia present in the included studies. Given this fact, an analysis of efficacy, safety and tolerability may be limited [

24]. Nevertheless, some real world setting studies and case series are revealing that elderly and immunosuppressed patients may exhibit pathological and clinical responses similar to those seen in patients from clinical trials with specific inclusion criterias [

27,

34]. The real world setting safety, tolerability data aso has been comparable to clinical trials, indicating neoadjuvant Cemipimab a feasible treatment even in immunosuppressed, elderly and multiple comorbidities patients [

37,

38,

40].

The cSCC most applied systemic therapies (platinum base and EGFR)20,38 typically present recurrence, limited responses and ealy progression, in contrast to Cemiplimab where fatal adverse events are rare, showing high response rates being safe and well tolerated. Further studies are needed in order to confirm long-term toxicity profile, efficacy and safety in real-world setting treatment groups [

24,

27,

32].

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, neoadjuvant Cemiplimab therapy for cSCC patients shows high response rates, tolerability and safety, lower recurrence, and improved survival. Fatal adverse events are rare, and TRAEs are immune-mediated, usually well managed. Although future studies are necessary to analyze its feasibility in real-world settings, some case series already indicate comparable results between the current trials and immunosuppressed patients. Finally, the benefits seem to outweigh the risks, and it is considered a promising and efficient treatment.

Author Contributions

Flavio C. Hojaij: conceptualization; writing - review and editing; supervision; project administration. Julia A. Kasmirski: validation; writing - review and editing. Maria E. Palomba: investigation; writing - original draft; visualization. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

his research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| SCC |

Squamous Cell Carcinoma |

| BCC |

Basal Cell Carcinoma |

| cSCC |

CutaneousSquamous Cell Carcinoma |

| CPR |

Complete Pathological Response |

| MPR |

Major Pathological Response |

| PPR |

Partial Pathological Response |

| NR |

No Pathological Response |

| ORR |

Objective Response Rate |

| TRAES |

Treatment related adverse effects |

| DSS |

Disease specific survival |

| DFS |

Disease free survival |

| EFS |

Event free survival |

| QoL |

Quality of Life |

| ICIs |

Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors |

| SOT |

Solid organ transplants |

| NAIT |

Neoadjuvant immunotherapy treatment |

Appendix A

Table A1.

Methodological Index for Nonrandomized Studies (MINORS).

Table A1.

Methodological Index for Nonrandomized Studies (MINORS).

| Authors |

Clearly stated aim |

Inclusion of consecutive patient |

Prospective collection of data |

Endpoints appropriate to the aim of the study |

Unbiased assessment of the study endpoints |

Follow-up appropriate for the aim of the study |

Loss to follow-up |

Prospective calculation of study size |

MINORS score |

| Gross et al.17 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

1 |

0 |

13 |

| Rischin et al. 11 |

2 |

1 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

1 |

1 |

10 |

| Gross et al.16 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

1 |

2 |

2 |

0 |

1 |

11 |

| Ferrarotto et al.15 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

0 |

14 |

| Ferrarotto et al.14 |

2 |

2 |

1 |

1 |

2 |

1 |

2 |

0 |

11 |

| Kim et al.21 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

1 |

2 |

1 |

2 |

0 |

12 |

| Godfarb et al.23 |

2 |

1 |

0 |

1 |

2 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

8 |

References

- CHANG, Michael S.; AZIN, Marjan; DEMEHRI, Shadmehr. Cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma: the frontier of cancer immunoprevention. Annual Review of Pathology: Mechanisms of Disease, v. 17, n. 1, p. 101-119, 2022. [CrossRef]

- CIUCIULETE, Alexandra-Roxana et al. Non-melanoma skin cancer: statistical associations between clinical parameters. Current health sciences journal, v. 48, n. 1, p. 110, 2022. [CrossRef]

- FESTA NETO, C. Cutaneous Dermatosis . In: FUJIYOSHI, S. M. (Ed.). Manuel de Dermatologia . Barueri: Editor Manole Ltda., 2019. p. 322–426.

- QUE, Syril Keena T.; ZWALD, Fiona O.; SCHMULTS, Chrysalyne D. Cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma: Incidence, risk factors, diagnosis, and staging. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology, v. 78, n. 2, p. 237-247, 2018.

- ALAM, Murad et al. Guidelines of care for the management of cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology, v. 78, n. 3, p. 560-578, 2018. [CrossRef]

- SOLEYMANI, Teo et al. Clinical outcomes of high-risk cutaneous squamous cell carcinomas treated with Mohs surgery alone: An analysis of local recurrence, regional nodal metastases, progression-free survival, and disease-specific death. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology, v. 88, n. 1, p. 109-117, 2023. [CrossRef]

- STRATIGOS, Alexander et al. Diagnosis and treatment of invasive squamous cell carcinoma of the skin: European consensus-based interdisciplinary guideline. European journal of cancer, v. 51, n. 14, p. 1989-2007, 2015. [CrossRef]

- EZZIBDEH, Rami; DIOP, Mohamed; DIVI, Vasu. Neoadjuvant Immunotherapy in Non-melanoma Skin Cancers of the Head and Neck. Current Treatment Options in Oncology, v. 25, n. 7, p. 885-896, 2024. [CrossRef]

- DE, S. K. SPEC –Medicines for Cancer: Mechanism of Action and Clinical Pharmacology of Chemo, Hormonal, Targeted, and Immunotherapies, 12-Month Access, eBook. [s.l.] Elsevier, 2023.

- JIANG, Yongshuai et al. PD-1 and PD-L1 in cancer immunotherapy: clinical implications and future considerations. Human vaccines & immunotherapeutics, 2019. [CrossRef]

- LORINI, Luigi; ALBERTI, Andrea; BOSSI, Paolo. Advanced cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma management in immunotherapy era: achievements and new challenges. Dermatology Practical & Conceptual, v. 13, n. 4, 2023. [CrossRef]

- RESEARCH, C. FOR D. E. AND. FDA approves cemiplimab-rwlc for metastatic or locally advanced cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma. FDA, 20 dez. 2019.

- AGÊNCIA NACIONAL DE VIGILÂNCIA SANITÁRIA (ANVISA). Libtayo (cemiplimabe): new indication. Available at <https://www.gov.br/anvisa/pt-br/assuntos/medicamentos/novos-medicamentos-e-indicacoes/libtayo-cemiplimabe-nova-indicacao-2> Accessed in January 12th of 2025.

- CAO, Lei-Ming et al. Less is more: Exploring neoadjuvant immunotherapy as a de-escalation strategy in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma treatment. Cancer Letters, p. 217095, 2024. [CrossRef]

- D. RISCHIN et al. Neoadjuvant cemiplimab for stage II–IV cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma (CSCC): 2-year follow-up and biomarker analyses. Annals of Oncology, v. 35, p. S722–S722, 1 set. 2024. [CrossRef]

- FERRAROTTO, Renata et al. Outcomes of treatment with neoadjuvant cemiplimab for patients with advanced, resectable cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck: secondary analysis of a phase 2 clinical trial. JAMA Otolaryngology–Head & Neck Surgery, v. 149, n. 9, p. 847-849, 2023.

- FERRAROTTO, Renata et al. Pilot Phase II Trial of Neoadjuvant Immunotherapy in Locoregionally Advanced, Resectable Cutaneous Squamous Cell Carcinoma of the Head and Neck. Clinical Cancer Research: An Official Journal of the American Association for Cancer Research, v. 27, n. 16, p. 4557–4565, 15 ago. 2021. .

- GROSS, N. D. et al. Neoadjuvant cemiplimab and surgery for stage II–IV cutaneous squamous-cell carcinoma: follow-up and survival outcomes of a single-arm, multicentre, phase 2 study. The Lancet Oncology, v. 24, n. 11, p. 1196–1205, 1 nov. 2023. .

- GROSS, N. D. et al. Neoadjuvant Cemiplimab for Stage II to IV Cutaneous Squamous-Cell Carcinoma. New England Journal of Medicine, 12 set. 2022. [CrossRef]

- 20. HEPPT, Markus V.; LEITER, Ulrike. Cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma: state of the art, perspectives and unmet needs. JDDG: Journal der Deutschen Dermatologischen Gesellschaft, v. 21, n. 4, p. 421-424, 2023.

- HOOIVELD-NOEKEN, Jahlisa S. et al. Towards less mutilating treatments in patients with advanced non-melanoma skin cancers by earlier use of immune checkpoint inhibitors. Critical Reviews in Oncology/Hematology, v. 180, p. 103855, 2022. [CrossRef]

- JEREMY ALLAN GOLDFARB et al. Immune checkpoint inhibitors for treatment of periorbital squamous cell carcinoma. British journal of ophthalmology, v. 107, n. 3, p. 320–323, 8 out. 2021. [CrossRef]

- KIM, E. Y. et al. Neoadjuvant-Intent Immunotherapy in Advanced, Resectable Cutaneous Squamous Cell Carcinoma. JAMA otolaryngology-- head & neck surgery, 28 mar. 2024. [CrossRef]

- MAGER, Layna et al. Cemiplimab for the treatment of advanced cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma: appropriate patient selection and perspectives. Clinical, Cosmetic and Investigational Dermatology, p. 2135-2142, 2023. [CrossRef]

- MCMULLEN, Caitlin P.; OW, Thomas J. The role of systemic therapy in advanced cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma. Otolaryngologic Clinics of North America, v. 54, n. 2, p. 343-355, 2021. [CrossRef]

- PHAM, James P. et al. An updated review of immune checkpoint inhibitors in cutaneous oncology: Beyond melanoma. European Journal of Cancer, p. 115121, 2024. [CrossRef]

- SHALHOUT, Sophia Z. et al. Immunotherapy for non-melanoma skin cancer. Current Oncology Reports, v. 23, p. 1-10, 2021. [CrossRef]

- TONGDEE, Emily et al. Advanced squamous cell carcinoma: what’s new?. Current Dermatology Reports, v. 8, p. 117-121, 2019.

- TOPALIAN, Suzanne L. et al. Neoadjuvant immune checkpoint blockade: a window of opportunity to advance cancer immunotherapy. Cancer cell, v. 41, n. 9, p. 1551-1566, 2023. [CrossRef]

- VARRA, Vamsi et al. Recent and emerging therapies for cutaneous squamous cell carcinomas of the head and neck. Current Treatment Options in Oncology, v. 21, p. 1-12, 2020. [CrossRef]

- QUEIROLO, P. et al. Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma: a GRADE approach for evidence evaluation and recommendations by the Italian Association of Medical Oncology. ESMO open, v. 9, n. 5, p. 103005, 2024.

- YAN, Flora; SCHMALBACH, Cecelia E. Updates in the Management of Advanced Nonmelanoma Skin Cancer. Surgical Oncology Clinics, v. 33, n. 4, p. 723-733, 2024. ttps://doi.org/10.1016/j.soc.2024.04.006.

- ASCIERTO, P. A. et al. NEO-CESQ study: Neoadjuvant plus adjuvant treatment with cemiplimab in surgically resectable, high risk stage III/IV (M0) cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma. Journal of Clinical Oncology, v. 41, n. 16_suppl, p. 9576–9576, 1 jun. 2023. [CrossRef]

- 34. ASCIERTO, Paolo A.; SCHADENDORF, Dirk. Update in the treatment of non-melanoma skin cancers: the use of PD-1 inhibitors in basal cell carcinoma and cutaneous squamous-cell carcinoma. Journal for Immunotherapy of Cancer, v. 10, n. 12, 2022. [CrossRef]

- WONG, W. et al. Neoadjuvant cemiplimab with platinum-doublet chemotherapy and cetuximab to de-escalate surgery and omit adjuvant radiation in locoregionally advanced head & neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC). Journal of Clinical Oncology, v. 41, n. 16_suppl, p. 6019–6019, 1 jun. 2023.

- DUNN, L. et al. 859P Neoadjuvant cemiplimab with platinum-doublet chemotherapy and cetuximab to de-escalate surgery and omit adjuvant radiation in locoregionally advanced head & neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC). Annals of Oncology, v. 35, p. S619, 2024.

- VERKERK, Karlijn et al. Cemiplimab in locally advanced or metastatic cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma: prospective real-world data from the DRUG Access Protocol. The Lancet Regional Health–Europe, v. 39, 2024. [CrossRef]

- BAGGI, A. et al. Real world data of cemiplimab in locally advanced and metastatic cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma. European Journal of Cancer, v. 157, p. 250–258, nov. 2021.

- BRANCACCIO, Gabriella et al. Challenges and new perspectives in the treatment of advanced cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma. Minerva Medica, v. 111, n. 6, p. 589-600, 2020. [CrossRef]

- M.W. ROHAAN et al. 1062P Real-world data on clinical outcome and tolerability in patients with advanced cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma treated with cemiplimab in the Netherlands. Annals of Oncology, v. 32, p. S884–S885, 1 set. 2021. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).