1. Introduction

Cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma (cSCC) is the second most prevalent skin cancer, after basal cell carcinoma, and accounts for one in five skin cancers [

1]. Around 48,000 new diagnoses of cSCC are made each year in England, which results in about 800 deaths annually [

2]. The incidence of cSCC has risen by up to 200% in the past three decades [

3], a trend projected to continue due to ageing populations worldwide and increasing awareness of this disease.

Greater than 95% patients with cSCC have localised disease which is amenable to curative surgery, radiotherapy, or combination therapy. However, for less than 5% of patients, who have either locally advanced or metastatic cSCC, their disease is not amenable to curative treatments and carries a significantly worse prognosis [

4]. Cytotoxic chemotherapeutics and eGFR inhibitors for advanced/metastatic cSCC were limited by significant treatment-related morbidity as well as poor durable response rates [

5]. The treatment of advanced/metastatic cSCC has been transformed by the use of monoclonal antibodies targeting the programmed cell death protein 1 (PD-1) receptor. PD-1 is a cell surface receptor predominantly expressed on T cells, with an important role in the regulation of the immune system. By binding to programmed death ligand 1 (PD-L1) and programmed death ligand 2 (PD-L2) on antigen presenting cells, PD-1 suppresses T cell inflammatory activity. Whilst useful in preventing autoimmunity, this mechanism is also utilised by cancer cells to evade immune surveillance. The PD-1 inhibitor cemiplimab blocks this interaction, enabling T cells to recognise and kill cancer cells.

In 2018, cemiplimab was approved as a first-line treatment for advanced cSCC not amenable for curative surgery or radiotherapy. This approval was based on positive results from multiple clinical trials demonstrating clinically significant and durable response rates, as well as acceptable safety profiles, in patient groups with advanced cSCC treated with cemiplimab [

6,

7,

8]. However, a group of patients derived no meaningful benefit from treatment in these studies, highlighting a need to develop predictors of response and resistance to therapy. In this retrospective multi-institutional study, we aimed to evaluate clinical parameters in a cohort of patients with recurrent, locally advanced, or metastatic cSCC (R/M-cSCC), to identify clinical and pathological associations with response to cemiplimab and duration on therapy, and to compare with previous findings of cemiplimab efficacy and safety.

2. Materials and Methods

Patients and treatment

All patients had a histological or cytological diagnosis of cSCC, with either locally advanced, recurrent, or metastatic disease, and were not candidates for curative surgery and/or curative radiotherapy. Patients were confirmed to be eligible for cemiplimab treatment without any contraindication or symptomatically active brain metastases or leptomeningeal disease. Patients had received no prior anti-PD-1, anti-PD-L1, anti-PD-L2, anti-CD137, or anti-Cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated antigen-4 (CTLA-4) therapies.

A total of 86 patients were treated with cemiplimab at a dose of 350mg every 3 weeks at 3 UK cancer centres. Treatment was continued until disease progression, unacceptable toxicity as per physician assessment, or patient withdrawal, up to a maximum treatment duration of 2 years or 35 three-weekly cycles, whichever occurred first. Dose delays, toxicity management, and re-initiation of cemiplimab was at the discretion of the treating physician and consistent with the Summary of Product Characteristics. All clinical data were anonymised and no patient level identifiable data were collected or included in this analysis; as such, no individual patient consent was required for our analysis.

Clinical characteristics including immunosuppression status, concurrent autoimmune disease, concurrent haematological malignancy, site of disease, and treatment outcomes were recorded for all patients. Immunosuppression was defined as receiving any immunosuppressive medication, including for solid organ transplantation. Overall survival (OS) and physician-assessed progression free survival (PFS) were calculated from the date of the first dose of cemiplimab. Toxicities documented in the medical notes were extracted and defined using the common terminology criteria for adverse events version 5 (CTCAE v5).

Standard of care radiological and clinical assessment, including choice of modality between MRI, CT and medical photography, were performed locally as directed by the treating physician. Response was assessed based on investigator assessment of radiological and clinical findings. Overall response rate (ORR) was defined as the complete response and partial response rates combined. Clinical benefit was defined as any response better than progressive disease and the clinical benefit rate (CBR) was the percentage of patients with clinical benefit.

Statistics

Data analyses were performed using the R programming language for Windows (v.4.4.1) in the RStudio interface (v.2024.04.2+764) [

9]. Univariate Kaplan-Meier survival analysis was performed with the ggsurvfit package; p-values were calculated using the log rank test [

10]. Graphs were built with the ggplot2 package [

11]. Toxicity odds ratios were calculated using Fisher’s exact test due to the small sample sizes. P-values were considered significant if ≤0.05.

3. Results

Data from 86 patients across 3 UK cancer centres were included in the analysis (

Table 1). Of these patients, 72% were male and 28% female and the median age was 71 years with a range of 34 to 93 years. Prior surgery and radiotherapy were performed in 68% and 58% of patients, respectively. The primary site was the skin of the head and neck region in 65% of patients, the remainder consisted of torso (7%), upper limb (7%), lower limb (18%) and unknown primary site (3%). Amongst the study population, local recurrence was present in 59/86 (69%) and metastatic disease in 82/86 (95%) of patients. A prior diagnosis of haematological malignancy was present in 15% of the patients, with chronic lymphocytic lymphoma the most frequent of these (69%). Seven patients (8%) had concurrent immunosuppression.

Of the 86 patients, 74 were evaluable for response. Three patients died from non-cancer related causes prior to assessment of response, and 9 patients did not reach the first assessment scan at the time of censoring. Complete response was observed in 29.7%, and partial response in 31.1% of patients, with an ORR of 60.8% (95% CI 49-71) (

Table 2). CBR was 74.3% (95% CI 63-83).

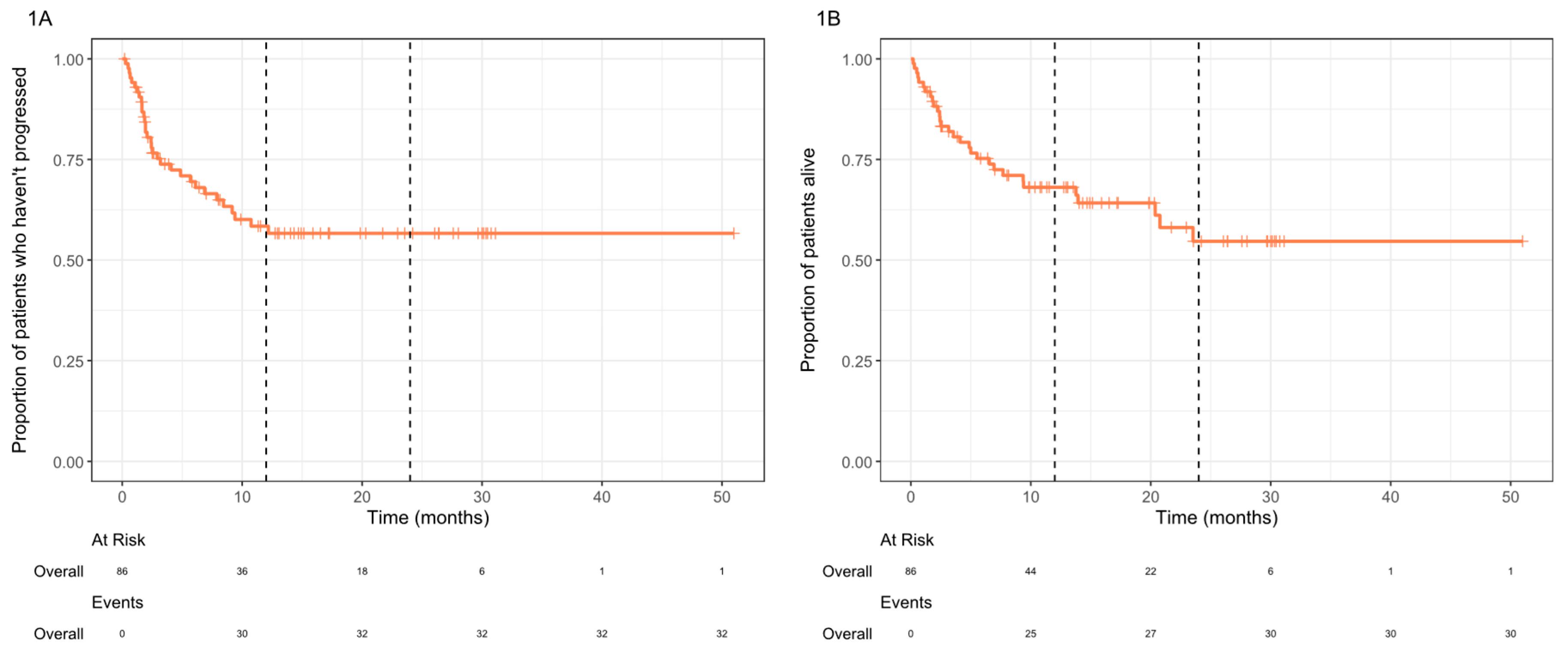

For the entire cohort, both median OS and PFS were not reached, and the 2-year OS rate was 54.7% (

Figure 1). Durable clinical benefit lasting for >12 months was seen in 38% of patients (n=33/86). At the time of analysis, 8 of the complete responders had ongoing cemiplimab treatment, the others were not undergoing treatment due to treatment completion (36.3%), discontinuation secondary to immunotherapy-related toxicities (18.2%), or unrelated mortality (9.1%).

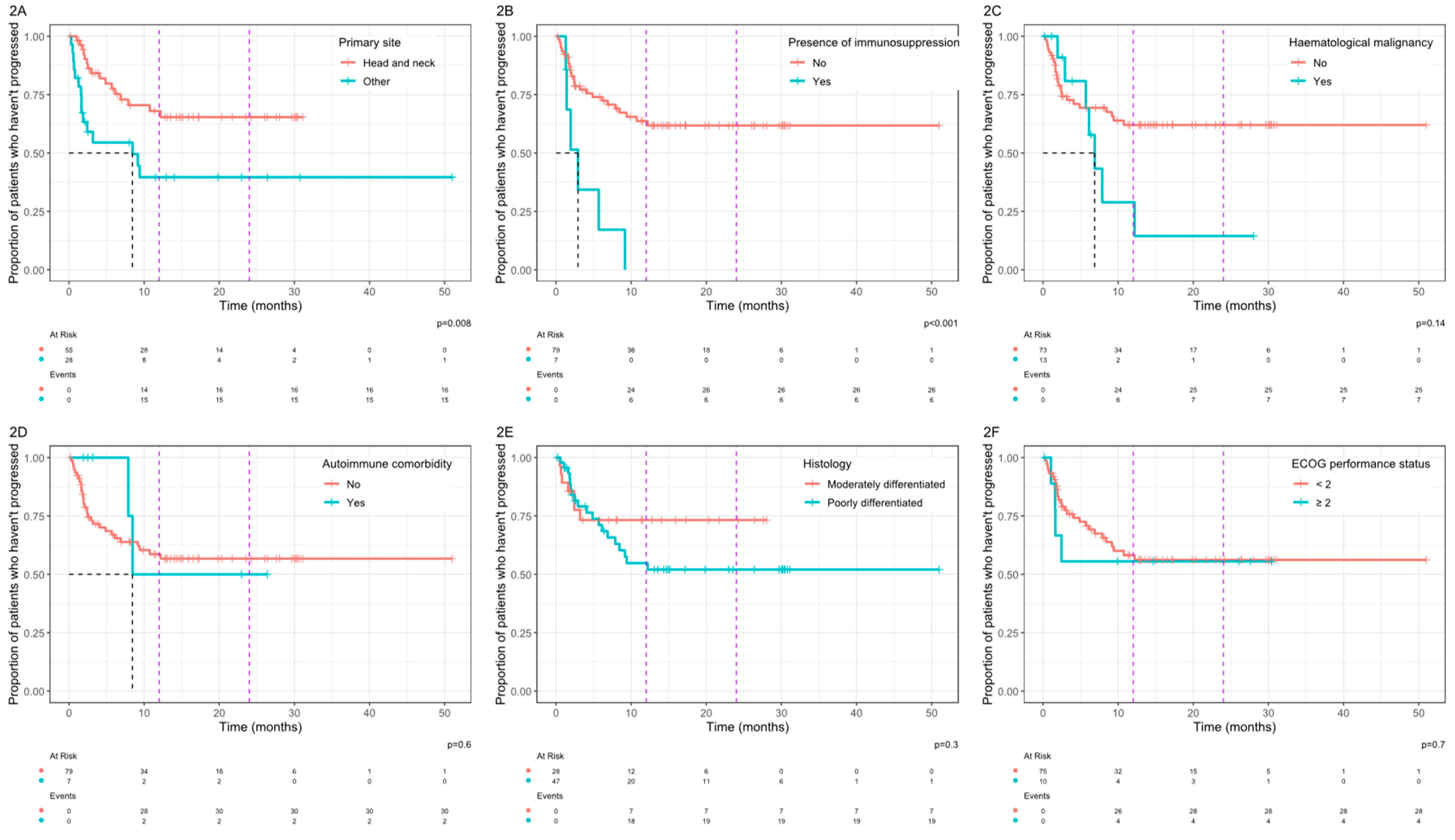

In analysis of associations between clinical variables and PFS, patients with a primary site arising from the skin of the head and neck region had significantly improved PFS compared with other sites combined (

Figure 2A). In addition, the presence of immunosuppression was associated with a significantly worse PFS (

Figure 2B). For HN primary site, the median PFS was not reached versus 8.4 months for other sites (p=0.008). For patients with concurrent immunosuppression, the median PFS was 2.9 months vs not reached in those without immunosuppression (p<0.001). For patients with a co-existing haematological malignancy (

Figure 2C), median PFS was 6.9 months vs not reached for patients without a haematological malignancy, but this did not reach statistical significance. For patients with poorly differentiated disease (

Figure 2E) the 12 month probability of progression was 45% vs 27% for moderately differentiated disease and the 24 month probability of progression was 48% vs 27%, but these differences did not reach statistical significance (p=0.3).

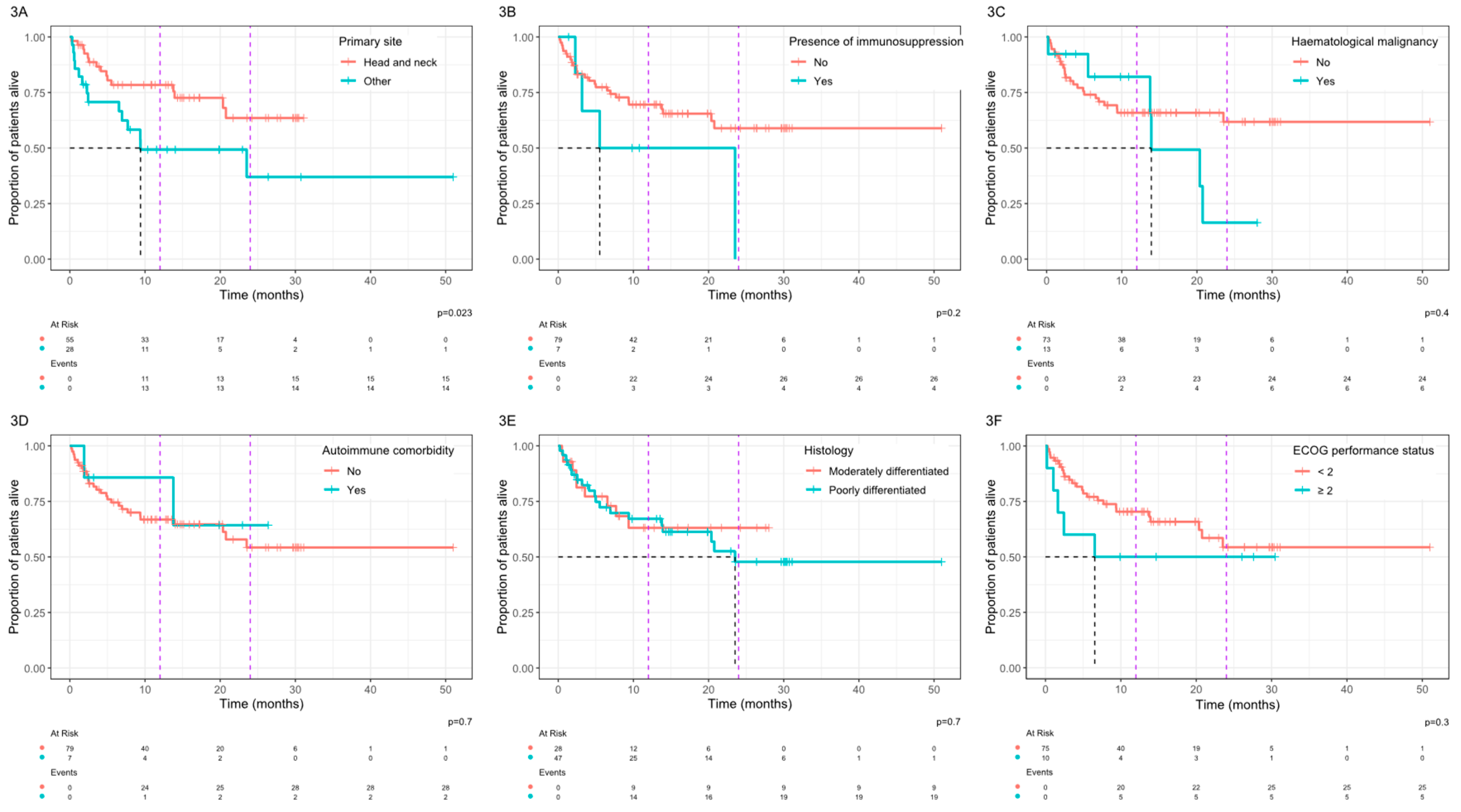

In analysis of associations between clinical variables and OS, a primary site arising from the skin of the head and neck was associated with a significantly improved OS with a median OS that was not reached vs 9.4 months for other primary sites (p=0.023,

Figure 3A). Patients with a history of immunosuppression (

Figure 3B) or haematological malignancy (

Figure 3C) had a shorter OS but this did not reach statistical significance. No statistically significant differences in OS were observed based on other clinical parameters including the presence of an autoimmune comorbidity (

Figure 3D), histological grading (

Figure 3E), or an ECOG performance status ≥2 (

Figure 3F).

Median duration of follow up was 14 months (range 0.2 – 51) and the median number of cycles administered was 8 (range 1 – 36). For the 86 patients included in the study, 47% developed immune-related (IR) toxicities of any CTCAE grade, while 13% developed grade 3 or above. Treatment was stopped in 10 patients (12%) due to immunotherapy-related toxicities. A single patient (1.2%) died due to IR toxicity.

None of the analysed clinical parameters were associated with a significantly increased risk of immunotherapy toxicity using Fisher’s exact test (

Table 3).

4. Discussion

This retrospective study demonstrated the efficacy of cemiplimab for treating patients with R/M-cSCC across three cancer centres in the UK. The 86 patients included in the study had comparable demographics to those in the clinical trial populations [

6,

8], and in a previous retrospective study [

12]. A large proportion of patients were older, male, or with head and neck as their primary site of disease. In contrast, this study included a larger proportion of patients with poorly differentiated disease compared to the clinical trial population (55% vs 28%) [

8], and also patients with co-existing haematological malignancy (15%) as well as those with a performance status of greater than 1 (12%), who were excluded from the Phase II trial.

An ORR of 60.8% as assessed by the treating physician was observed in the current study, including 30% with complete response and 31% with partial response. This is a better response compared to the 44-50% observed by Migden

et al in two clinical trials but may reflect the lack of a central assessment of response in our study [

6,

8]. Patients with cSCC of the skin of the head and neck as the primary disease site responded significantly better than those with other primary sites combined, as reflected in the improved median OS (not reached vs 9.4 months) and median PFS (not reached vs 8.4 months). This result is consistent with previous real-world retrospective studies which found head and neck primary site of disease was associated with a longer PFS compared to the torso and limbs [

12,

13]. The molecular basis underlying this improved response remains unclear. One hypothesis is that disease arising within the skin of the head and neck may be associated with a higher tumour burden as a result of greater sun-exposure compared to other sites, which has previously been linked to improved survival responses to immune checkpoint inhibitor treatments in various cancers [

14]. Further molecular investigations may discover useful predictive biomarkers that can help better direct treatment.

In contrast to a previous study [

12], we did not observe a statistical difference on OS or PFS based on performance status, this may be due to a smaller proportion of patients with lower performance status in our cohort.

The safety profile of cemiplimab in our cohort was comparable to other real-world studies [

12,

13], with 13% of patients experiencing grade 3 or above adverse events, and 12% discontinuing treatment due to adverse events. Due to the retrospective nature of this study, further details into the nature of the adverse events could not be retrieved for some patients due to insufficient toxicity data, which is a limitation of this study. In addition, no clinical parameter was associated with an increased risk of developing toxicity- most notably this included patients with an autoimmune comorbidity who are typically excluded from immunotherapy clinical trials. However, the sample sizes are small which limits the statistical confidence in the analysis.

Immunosuppressed patients were found to have a significantly worse PFS, with no patients remaining progression free at one year after initiation of treatment. Median OS was also less than 12 months. Patients were immunosuppressed for reasons including previous solid organ transplant and suppression of autoimmune disease. However, specific details on the nature of immunosuppressive therapy for these patients could not be retrieved and the sample size was small. This paper suggests that immunotherapy is not effective for immunosuppressed patients, but further research into the association between immunosuppression and response to immunotherapy is warranted.

5. Conclusions

Cemiplimab treatment demonstrated significant clinical benefit in patients with R/M-cSCC with an acceptable side effect profile in the real-world setting, which is comparable to previous studies. Patients with a head and neck primary site have a significantly improved OS and PFS compared with other primary sites when treated with cemiplimab; future work should be undertaken to investigate the biological basis for this to identify useful predictive biomarkers.

Author Contributions

R.M., S.R., R.Y., S.B., O.D., H.W., G.F., S.B., and P.I. designed the work; R.M., S.R., R.Y., S.B., O.D., H.W., G.F., S.B., P.I., and J.E.H. acquired data; J.E.H., S.R., S.R., and R.Y. analysed data; J.E.H., S.R., and R.M. drafted, revised, and approved the manuscript; J.E.H., S.R. and R.M. agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work. J.E.H. and S.R. contributed equally to the work. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Funding support is provided to the head and neck research team by The Christie Charity, Syncona Foundation, and The Infrastructure Industry Foundation. There is no applicable grant number.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The analysis was conducted in accordance with the UK Policy Framework for Health and Social Care Research and the Declaration of Helsinki. Case series review and data analyses were performed on anonymised data without any patient-level identifiable information and did not require ethics approval.

Informed Consent Statement

Patient consent was waived for all subjects included in the study due to the use of anonymised data without any patient-level, identifiable, confidential information.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to the requirement to uphold the data sharing with relevant approved researchers as stipulated in the ethical approval.

Conflicts of Interest

R.M. reports the following: Honoraria: Bristol Myers Squibb (BMS), Merck Sharp and Dohme (MSD), Roche, Bayer, Achilles Therapeutics, Aptus Clinical, PCI Biotech, Ayala Pharmaceuticals, Oxsonics. O.D. reports the following: Honoraria: Sanofi, Regeneron, Achilles Therapeutics; Speaking fees: Sanofi, Regeneron. G.F. reports the following: Consulting or Advisory Role: Bristol Myers Squibb (BMS), Janssen, Novartis, Pfizer, Eisai; Speakers’ Bureau: Roche, Bristol Myers Squibb (BMS), Novartis, Eisai, Pierre Fabre, Merck Serono, Janssen Oncology, MSD Oncology, Sanofi, Astellas Pharma, Pfizer, Bayer; Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: Novartis, Janssen, Bayer, Merck Serono, Recordati. The other authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R.L.; Laversanne, M.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A.; Bray, F. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA: a cancer journal for clinicians 2021, 71, 209–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- New data shows a record 224,000 skin cancers in England in 2019. Available online: https://www.skinhealthinfo.org.uk/new-data-shows-a-record-224000-skin-cancers-in-england-in-2019 (accessed on 12 September 2023).

- Waldman, A.; Schmults, C. Cutaneous Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Hematology/oncology clinics of North America 2019, 33, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmults, C.D.; Karia, P.S.; Carter, J.B.; Han, J.; Qureshi, A.A. Factors predictive of recurrence and death from cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma: a 10-year, single-institution cohort study. JAMA dermatology 2013, 149, 541–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alberti, A.; Bossi, P. Immunotherapy for Cutaneous Squamous Cell Carcinoma: Results and Perspectives. Frontiers in oncology 2021, 11, 727027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Migden, M.R.; Rischin, D.; Schmults, C.D.; Guminski, A.; Hauschild, A.; Lewis, K.D.; Chung, C.H.; Hernandez-Aya, L.; Lim, A.M.; Chang, A.L.S.; et al. PD-1 Blockade with Cemiplimab in Advanced Cutaneous Squamous-Cell Carcinoma. NEJM 2018, 379, 341–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rischin, D.; Khushalani, N.I.; Schmults, C.D.; Guminski, A.; Chang, A.L.S.; Lewis, K.D.; Lim, A.M.; Hernandez-Aya, L.; Hughes, B.G.M.; Schadendorf, D.; et al. Integrated analysis of a phase 2 study of cemiplimab in advanced cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma: extended follow-up of outcomes and quality of life analysis. Journal for immunotherapy of cancer 2021, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Migden, M.R.; Khushalani, N.I.; Chang, A.L.S.; Lewis, K.D.; Schmults, C.D.; Hernandez-Aya, L.; Meier, F.; Schadendorf, D.; Guminski, A.; Hauschild, A.; et al. Cemiplimab in locally advanced cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma: results from an open-label, phase 2, single-arm trial. The Lancet Oncology 2020, 21, 294–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2023; Available online: https://www.R-project.org (accessed on 19 September 2024).

- Sjoberg, D.; Baillie, M.; Fruechtenicht, C.; Haesendonckx, S.; Treis, T.; ggsurvfit: Flexible Time-to-Event Figures. R package Version 1.0.0. 2023. Available online: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=ggsurvfit (accessed on 19 September 2024).

- Wickham, H. ggplot2: Elegant Graphics for Data Analysis; Springer-Verlag: New York, NY, USA, 2016; Available online: https://ggplot2.tidyverse.org (accessed on 19 September 2024)ISBN 978-3-319-24277-4.

- Hober, C.; Fredeau, L.; Pham-Ledard, A.; Boubaya, M.; Herms, F.; Celerier, P.; Aubin, F.; Beneton, N.; Dinulescu, M.; Jannic, A.; et al. Cemiplimab for Locally Advanced and Metastatic Cutaneous Squamous-Cell Carcinomas: Real-Life Experience from the French CAREPI Study Group. Cancers 2021, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baggi, A.; Quaglino, P.; Rubatto, M.; Depenni, R.; Guida, M.; Ascierto, P.A.; Trojaniello, C.; Queirolo, P.; Saponara, M.; Peris, K.; et al. Real world data of cemiplimab in locally advanced and metastatic cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma. European journal of cancer 2021, 157, 250–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Samstein, R.M.; Lee, C.H.; Shoushtari, A.N.; Hellmann, M.D.; Shen, R.; Janjigian, Y.Y.; Barron, D.A.; Zehir, A.; Jordan, E.J.; Omuro, A.; et al. Tumor mutational load predicts survival after immunotherapy across multiple cancer types. Nature genetics 2019, 51, 202–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).