1. Introduction

Cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma (CSCC) is the second most common skin cancer in the United States, after basal cell carcinoma. The precise incidence of CSCC is not easily determined, as this cancer is not reported via the NCI Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) cancer registry. It has been estimated that there are more than 1,000,000 individuals who develop CSCC every year in the United States [

1]. Most CSCC are small, localized lesions that are easily treated with surgery, radiotherapy or other ablative procedures [

1]. It has more recently become apparent that occasionally patients develop more advanced stage lesions. It is estimated that 3-7% of CSCC patients develop deeply invasive local disease, or even regional and distant metastases [

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7]. For example, in 2012 it was estimated that about 5604-12,572 patients developed metastatic CSCC in the United States, and 3932-8791 died as a consequence [

3].

The population most susceptible to deeply invasive or metastatic CSCC predominantly comprises elderly, fair-skinned Caucasians with a history of extensive sun exposure, particularly involving the head, neck and upper torso regions [

8]. Several tumor-related factors contribute to an increased risk of locally advanced or metastatic CSCC, including primary tumor localization to head and neck sites, indistinct and infiltrative lesion borders, rapid tumor growth, a diameter exceeding 2 cm, and invasion to a depth greater than 2.0 mm [

8,

9,

10]. Furthermore, the presence of perineural extension increases the likelihood of aggressive disease progression [

11]. Host factors, such as immunosuppression following solid organ transplantation, or in patients with co-existing immune defects, such as HIV, chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL), and indolent lymphomas, increase the aggressiveness and metastatic potential of CSCC. Additionally, tumor recurrence following prior surgical excision or radiotherapy increases the risk for deeper invasion or metastasis [

12]. Staging systems, including those from the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC), the Union for International Cancer Control (UICC), and the Brigham and Women’s Hospital classification have been used to identify high-risk patients for more intensive therapy [

13,

14,

15].

There have been recent advances in the medical treatment of locally advanced or metastatic CSCC. Immune checkpoint inhibitors such as the PD-1 antibodies cemiplimab and pembrolizumab have shown significant clinical activity in the treatment of locally advanced or metastatic CSCC [

16,

17]. It should be noted that these studies included patients who had progressed after prior surgery or radiotherapy [

18]. In clinical trials with these agents, rapid and deep objective responses were seen, including many patients with durable responses or remissions.

Despite these promising results, there is limited “real world” data to evaluate the effectiveness of PD-L1 inhibitors, such as cemiplimab, in advanced CSCC patients. We performed a retrospective analysis of the outcome of cemiplimab therapy for patients with advanced CSCC in a large skin cancer-focused community practice. We performed an exploratory analysis of treatment outcomes in several clinically important subsets of patients including those with locally advanced, metastatic, and “too numerous to count” (TNTC) small primary lesions. We also describe a small group of patients treated with cemiplimab in combination with concurrent radiotherapy, who had initially failed to respond to 2-4 cycles of cemiplimab treatment.

2. Materials and Methods

All patients who had been treated with cemiplimab by a single oncologist (WS) were identified via a search of iKnowMed Database [IKM-G2, McKesson, Woodlands TX). Each patient’s medical record was individually accessed, and relevant data was extracted into a password-protected spreadsheet (Microsoft Excel v16.86, Redmond WA). Patients were included in the current analysis if they were diagnosed with cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma (CSCC) and had received more than 1 dose of cemiplimab. Each patient was assigned an arbitrary unique patient number (UPN). Patients with mixed squamous and basal cell carcinoma or who had received cemiplimab treatment for other indications (i.e., basal cell carcinoma or lung cancer) were excluded.

Patient characteristics recorded in the spreadsheet included age at the start of therapy, gender, race, comorbidities, and any cause for immunosuppression. Tumor characteristics, such as the primary tumor site, prior treatments (surgery, radiotherapy, or other therapy) were recorded. Whether patients had been treated for locally advanced tumors, multifocal CSCC or metastatic disease was noted. The sites of metastases were also recorded. Following data collection, the spreadsheet was deidentified. This study design has been reviewed by the chair of the Western IRB and has been deemed exempt from full IRB review.

2.1. Treatment Regimens

All patients were treated with a fixed dose of cemiplimab 350 mg IV every 3 weeks. The date of treatment initiation, duration of treatment, number of doses, and any cemiplimab-related toxicity were recorded. Occasional patients had treatment interruptions (i.e. insurance changes, comorbid illnesses, temporarily lost to follow-up). In these patients, treatment was analyzed from the time of treatment restart.

Patients who received concurrent radiotherapy in conjunction with cemiplimab administration were analyzed separately. All patients were treated using customized planning, with immobilization devices. Three patients were treated using 6 MeV electrons with custom blocking and the use of bolus. Two patients were treated with IMRT techniques using 6 Mev photons with bolus as needed. The latter patients were treated with conventional fractionation with 5 treatments per week. Data collected related to these patients included the dose of radiation (cGy), number of fractions, and elapsed time (days). Interruptions of RT for toxicity were also recorded.

2.2. Response Assessment

Whenever possible, quantitative response assessment was used to evaluate the objective response to cemiplimab treatment. Lesions were measured using computerized tomography (CT) scans, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) or positron emission tomography (PET) CT scans. Response was assessed by RECIST 1.1 criteria [

19]. A complete response (CR) was defined as complete resolution of all lesions. A partial response (PR) was defined as a > 30% reduction in the sum of cross-sectional measurements of index lesions. Progressive disease (PD) was present if there was a greater than 20% increase in the sum of bidimensional tumor measurements or new metastatic lesions developed. Stable disease (SD) was defined as tumor measurements not meeting the criteria for CR, PR or PD.

Some patients with superficial cutaneous lesions were not measurable based on radiographic imaging. These patients were assessed in a semi-quantitative fashion by skin examinations. In these patients, disappearance of raised tumor margins and healing of ulcers indicated a complete response. This was generally confirmed by biopsies of the residual abnormal scar tissue at the prior tumor site. Partial response was indicated by the presence of residual tumor which had decreased in size by >30%. Progressive disease was defined as either growth of the original lesion, or development of new metastatic lesions. Development of new CSCC skin primaries at remote sites was separately noted. This was not characterized as progression except in patients who were being treated for multifocal skin cancers, which were usually too numerous to count (TNTC). Local recurrence, distant metastases sites, and the development of any new malignancies (both skin and non-cutaneous malignancies) were recorded. Data collection ended June 8, 2024.

2.3. Statistical Analysis

Simple descriptive statistics were calculated via the Excel spreadsheet. A Kaplan-Meier analysis was performed to evaluate progression-free survival (PFS) [

20]. PFS was calculated for induction therapy from the beginning of initial CKI treatment until the date of relapse or disease progression.

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of the Study Population

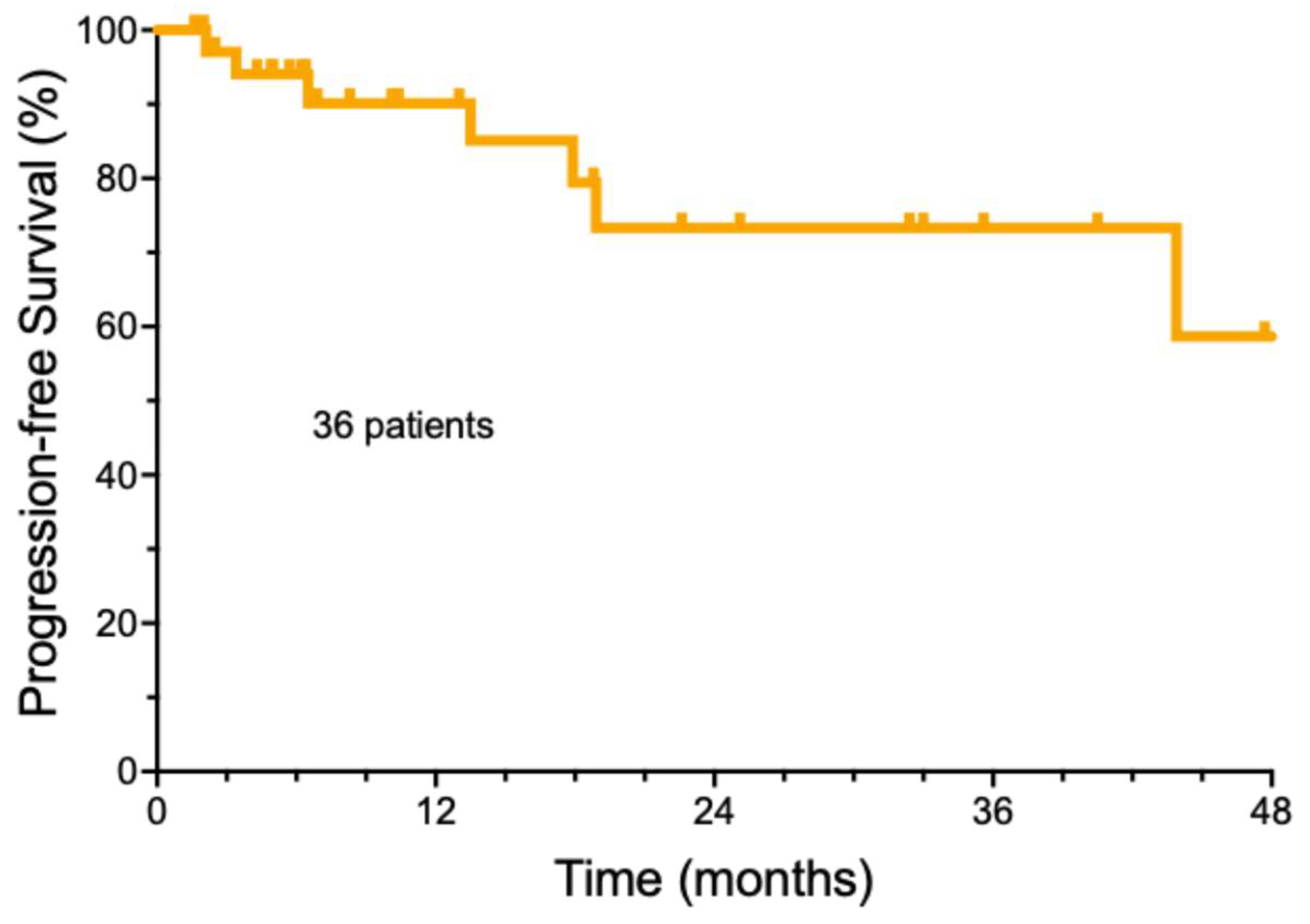

We identified 36 patients who were treated with cemiplimab for locally advanced or metastatic CSCC in our clinic (

Supplemental data Table S1). Our study population (26 men and 10 women) had a median age of 76.9 ± 10.6 years. There were 35 Caucasian patients and 1 Hispanic individual. Immunosuppression was suspected to be a contributory factor for aggressive CSCC tumor growth in 6 patients. Causes of potential immunosuppression included CLL (1), indolent NHL (2), treated chronic hepatitis C (1), HIV (1), and treatment with azathioprine plus ustekinumab for colitis (1).

A total of 29 patients had undergone a previous surgical resection and had progressed, while 7 patients had no prior surgery. The 7 patients with no prior surgery either presented with evidence of metastatic disease or presented with surgically unresectable CSCC. Twenty-six patients had not received prior radiotherapy to the current tumor site. Four patients had received other forms of local therapy.

3.2. Overall Outcome of Cemiplimab Treatment

The follow-up of the entire group of cemiplimab-treated patients was a median of 32.9 months±18.4 , with a range from 3.7- 61.1 months (

Supplemental data Table S2). The median number of cemiplimab doses was 8 (±6.3 doses StDev, range 2-39). The median duration of cemiplimab treatment was only 5.2 months (±5.6 months). A total of 22/36 (61.1%) patients achieved a complete remission, while 10 patients had a partial response (27.8%), 3 patients had stable disease (8.3%), and 1 patient developed progressive disease (2.8%). For the entire group, the estimated median progression free survival was undefined (

Figure 1). A total of 21 patients (58.3%) remained free of recurrence over the entire period of observation. The majority of the patients who achieved a remission (19/21, 90.5%) were able to electively discontinue therapy, based on a previously published strategy [

21]. Another 12 patients (33.3%) were alive with persistent CSCC. Deaths due to progressive CSCC were rare. Only one patient (2.8%) died due to CSCC within the study period. It should be noted that in this elderly population, 2 additional patients (5.6%) died of non-cancer related causes. One patient is currently still undergoing cemiplimab treatment, and 1 patient was lost to follow up.

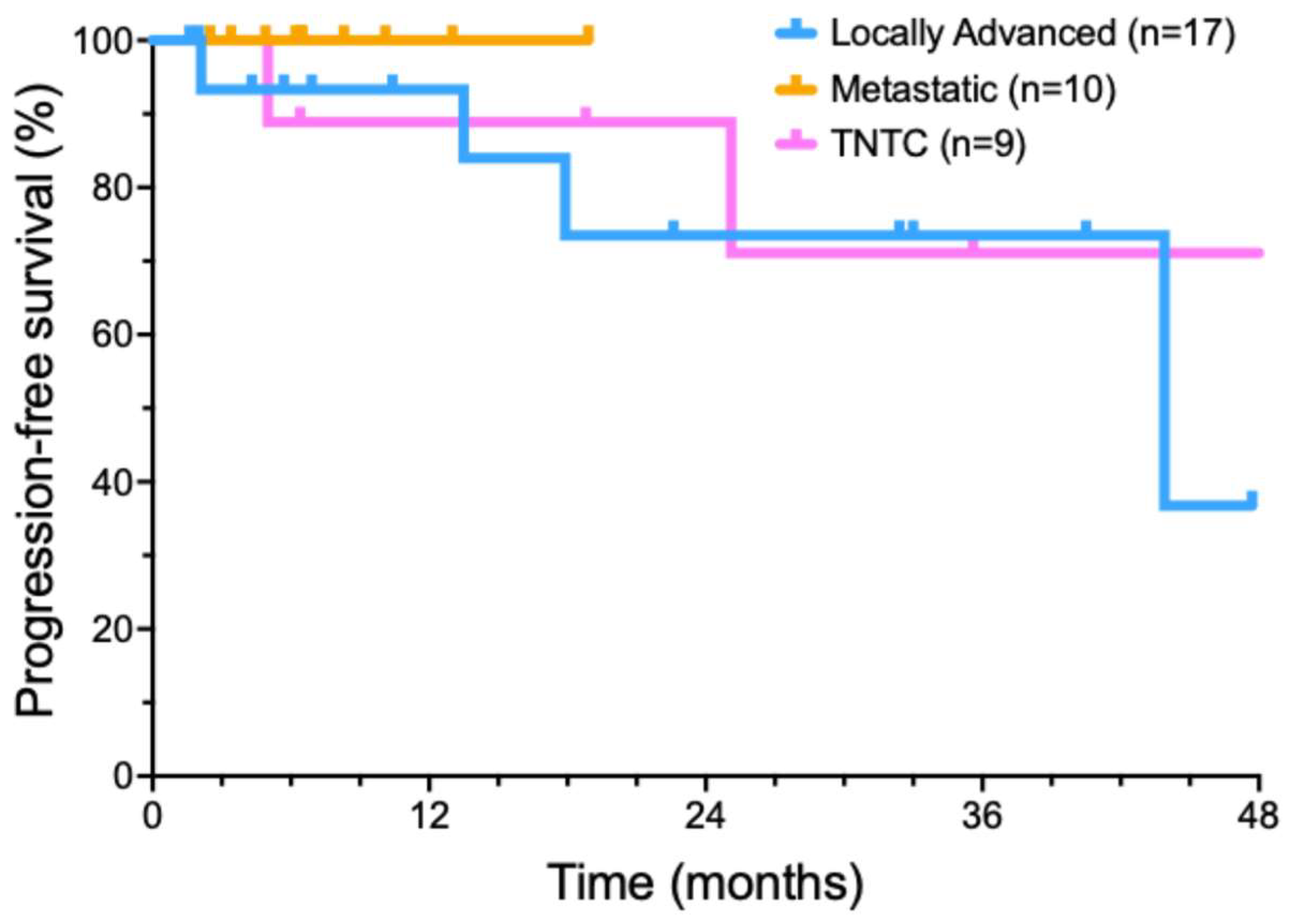

We also performed an exploratory analysis of several important recurring clinical scenarios for CSCC patients (

Figure 2). Nine patients presented with too many lesions to treat surgically (usually dozens or hundreds), that could no longer be managed by standard treatments. Eleven patients presented with metastatic disease at diagnosis, involving a total of 13 metastatic sites. Six of these patients had metastases from a head and neck CSCC primary to intra-parotid lymphoid tissue. In another subgroup of 5 patients, concurrent radiotherapy was added to locoregionally advanced disease after neoadjuvant cemiplimab cytoreductive therapy failed to produce a clinical response.

3.3. Cemiplimab for Treatment of Locally Advanced Tumors

A cohort of 17 patients was treated with cemiplimab for locally advanced CSCC. Potential follow up was a median of 30.5 months, (range 3.7 to 49 months). A total of 12/17 (70.6%) patients achieved a CR, 2 patients had a PR (11.8%), and 2 patients had SD (11.8%). Only one of the patients with a locally advanced tumor developed progressive disease (5.8%). Median progression free survival was 43.9 months (

Figure 2). At the end of data collection, 11/17 (64.7%) of patients remained in an ongoing remission.

3.4. Cemiplimab for Treatment of Metastatic CSCC

Our series included 11 patients who presented with metastatic CSCC. Potential follow up was a median of 32.9±14.8 months, (range 6.6- 53.8 months). Nine of these 11 (82%) patients achieved a CR with cemiplimab treatment, 2 patients had a PR. Median progression-free survival was not reached in this subset (

Figure 2). By the analysis date, all 9 CR patients remained in a long-term complete remission. Both PR patients (18%) developed recurrent disease.

3.5. Cemiplimab Treatment of Innumerable CSCC

Nine patients had TNTC CSCC. Potential follow up of the TNTC subset was a median of 42.8±20.9 months (range 5- 60.9 months. Of these 9 patients, 2 patients achieved an initial CR, 6 patients had a significant reduction in the number of lesions, 1 patient had SD, and 0 patients had PD. The median progression interval (time to new lesions) was 18.9 months (

Figure 2). By the end of the analysis period, only 2 patients (22.2%) with TNTC lesions remained free of new skin cancers, while 77.8% (7) patients had developed new CSCC lesions.

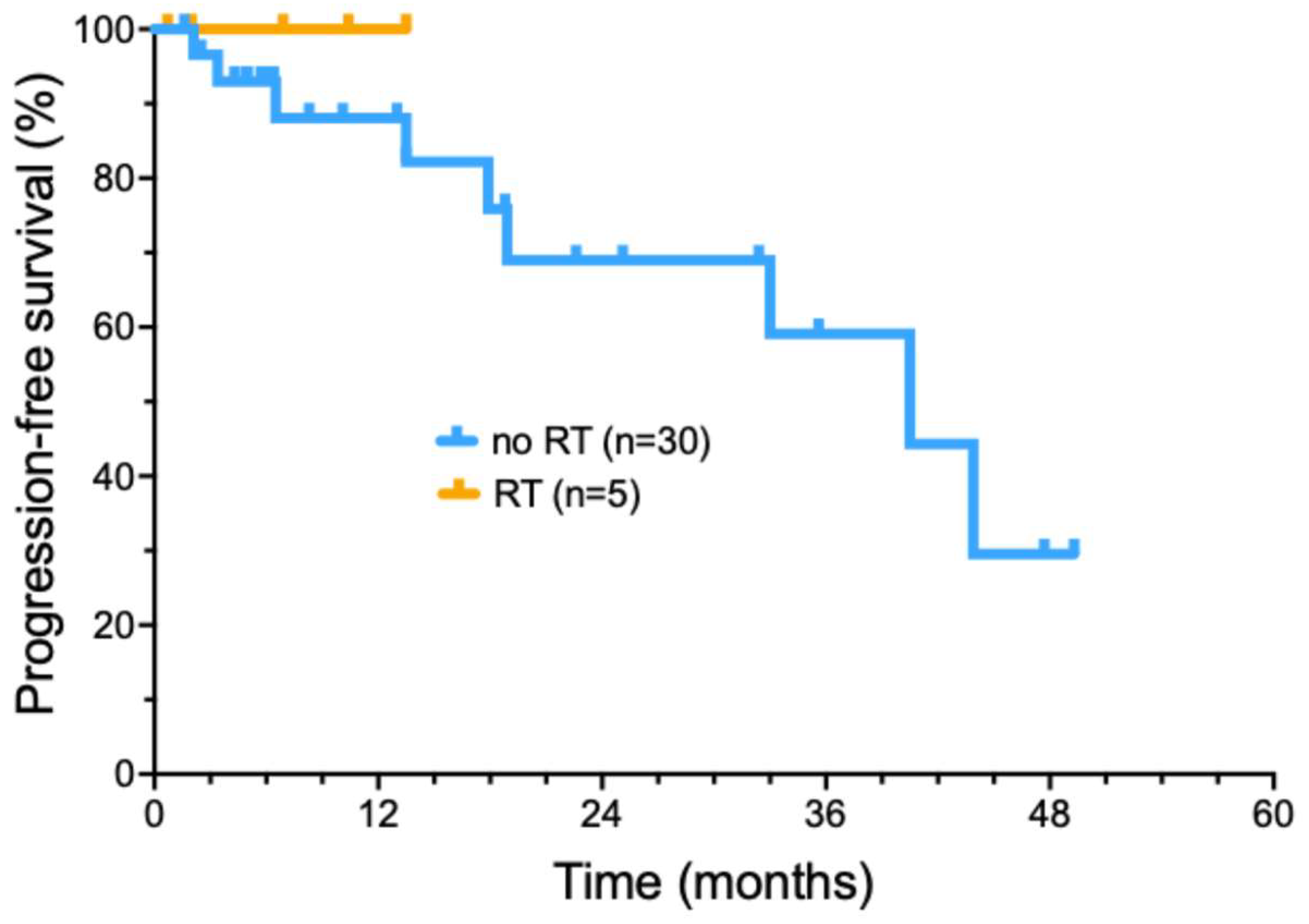

3.6. Cemiplimab Therapy with Concurrent RT

More recently, we have selectively added radiotherapy to cemiplimab treatment, in patients who did not achieve a significant tumor response following induction cemiplimab therapy (4 doses)(

Figure 3). Five patients were treated with the addition of concurrent RT during ongoing cemiplimab treatment (

Supplemental data Table S3). A total of 3/5 patients had locally advanced tumors, while two had regionally advanced metastatic disease. The delivered RT dose ranged from 6000- 7040 cGy (

median of 7000 cGy) delivered in 32-35 fractions (median 32 fractions) delivered over 36-96 days. No patients had interruptions in RT due to toxicity. Cemiplimab with concurrent RT had toxicities that included bullous pemphigoid (1), moderate skin reaction & mucositis (1), radiation dermatitis with pain and swelling of the treated area (1). All 5 patients treated with a combination of immunotherapy with involved field radiotherapy have remained in a complete remission, with a short median duration of follow-up (16.2 months).

4. Discussion

Previously, treatment options for locally advanced or metastatic CSCC were quite limited due to lack of effectiveness and the increased age and frailty of this patient population. Surgery and radiotherapy were standard treatment options [

1]. Chemotherapy and agents targeting the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) demonstrated modest response rates [

22,

23,

24,

25,

26,

27]. Responses to chemotherapy and EGFR targeted agents appeared to be quite transient. Chemotherapy proved to be poorly tolerated due to a significant level of toxicity. We previously showed that combination therapy with cetuximab and concurrent radiotherapy can produce durable responses in selected patients with locally advanced CSCC [

28].

More recently, PD-1 antibody based immunotherapy of CSCC has demonstrated significant antitumor activity. Some tumor-related factors observed in CSCC may contribute to the high response rates seen with immune checkpoint inhibitor (ICI) treatment. These include elevated levels of PD-L1 expression (a binding partner for PD-1) in CSCC [

29]. In addition, a high tumor mutation burden in CSCC is believed to increase the expression of tumor-specific antigens, facilitating immune recognition and cytotoxicity [

29].

Trials with PD-1 inhibitors have demonstrated significant clinical efficacy in patients with unresectable or metastatic CSCC. For example, Maubec et al. performed a phase II study with pembrolizumab that found an overall response rate of 41% among patients, with nearly half of these responses sustained for 6 months or more [

17]. In another phase II study, nivolumab achieved a 58.3% objective response rate, with some responses showing durability over extended follow-up (17.6 months) [

30]. A third PD-1 directed monoclonal antibody, cemiplimab, has also demonstrated significant activity in CSCC patients, including those with locally advanced and metastatic disease [

16]. In this phase II study, a 50% RECIST response rate (based on radiologic assessment or clinical photography) was observed following cemiplimab in patients with locally advanced disease. Similarly, a response rate of 47% was observed in a metastatic-disease cohort. Durable responses were observed, although the published median follow-up of this trial was relatively short (8.7 months) [

16]. In a subsequent confirmatory open-label study of cemiplimab, a significant response percentage was confirmed, with a median progression-free survival of 26 months [

31].

One of the problems of clinical trials, is that these patients are frequently highly selected based on study entry criteria, as well as superior performance status. Thus, clinical trial outcomes may not mirror what is seen in clinical practice. In a real-world evaluation by Kuzmanovski, et al., 25 patients were treated with cemiplimab. These investigators observed an objective response rate of 52% (3 complete and 10 partial responses) [

32]. Toxicity appeared to be significant in this trial, with a 36% rate of serious adverse events. In fact, six patients (24%) were withdrawn from treatment due to toxicity.

Verkerk et al. published data from 151 patients enrolled in a registry trial in the Netherlands [

33]. The physician-assessed objective response rate was 35.1%. With a median follow-up of 15.2 months, median progression-free survival was only 12.2%. However, serious adverse events occurred in 29.8% of their patients.

Our findings confirmed a high level of activity of cemiplimab in locally advanced or metastatic CSCC. The onset of response was generally rapid and could frequently be detected after even one or two doses of cemiplimab. We also described a higher complete response rate than was previously reported (70-80%). In clinical trials, response assessment typically relied on imaging criteria (e.g., iRECIST) or clinical photographs to evaluate tumor shrinkage or stability [

34]. In CSCC immunotherapy trials, residual scar tissue at a treated site may mimic persistent disease. In our experience, it is important to verify the degree of cancer response via a biopsy. This ensures that persistent stable abnormalities on clinical exam or imaging are not misinterpreted as active disease. This may prevent unnecessary treatment continuation or escalation. Alternatively, if persistent tumor is identified, premature treatment discontinuation can be avoided. Most of our complete responses have proven durable, allowing eventual elective treatment discontinuation. We have previously published an effective strategy of treatment discontinuation for patients based on confirmation of a complete remission [

21]. The benefit of continuing cemiplimab therapy beyond a CR may not outweigh the risks of long-term toxicity [

35].

While the initial treatment response in patients with innumerable (TNTC) CSCC primaries was high, most of these patients (77.8%) eventually developed new CSCC lesions. It is not clear whether more prolonged treatment of these patients would be more effective. Thus, additional treatment strategies to prevent the development of new primary CSCC are needed for this patient subset.

We also performed an exploratory analysis of the potential benefit of adding radiotherapy for patients with minimal clinical response to 4 doses of cemiplimab therapy. All 5 patients who received concurrent RT added to ongoing cemiplimab therapy achieved a durable CR. This approach did not lead to any unexpected toxicities. Thus, further prospective evaluation of this promising approach is suggested, to confirm the apparent high level of local control of locally advanced CSCC.

Our data also suggest that CSCC treatment with cemiplimab has manageable immunologic adverse events. Toxicities in our patients were similar to those observed in other trials of PD-1/PD-L1 blocking agents [

36]. Fatigue appeared to be the most common side effect. A small percentage of patients experienced a pruritus, rash, epigastric discomfort, fevers/chills, dizziness, balance issues, mild headache, hives, and significant cough. No patients were hospitalized due to treatment toxicity. Only 1 patient died of progressive CSCC following cemiplimab treatment. Two elderly patients died of non-cancer related causes.

Our study provides real-world data involving diverse populations that may not be adequately represented in clinical trials and provides novel insights into cemiplimab effectiveness in recurring clinical scenarios. The strengths of the current study include consistent treatment by a single physician experienced in managing ICI toxicity. In addition, we report a relatively lengthy follow-up of treated patients.

Limitations of the study included the use of retrospective data acquired over a number of years. Thus, referral bias and other potentially confounding variables are hard to evaluate. Additionally, 5 patients were lost to follow up, and 2 patients died of other age-related causes. Thus, due to the relatively small number of patients, our experimental results should be considered hypothesis generating. Additionally, our study did not specifically address CSCC in additional important clinical subsets of CSCC patients, such as in the setting of lymphoproliferative disease, immunosuppression, or in transplant recipients.

5. Conclusions

We have confirmed a high level of clinical activity of cemiplimab of advanced CSCC patients treated in a community practice. Our study included a significant percentage of patients, who achieved complete remissions and were able to discontinue therapy after radiologic or pathologic confirmation of complete remission. Specific patient subsets with locally advanced or metastatic CSCC had a high durable complete remission rate. We saw enhanced treatment activity following the addition of radiotherapy in patients who were not responding to cemiplimab after the initial 4 doses. While cemiplimab treatment proved active in reducing the number of existing lesions in patients with TNTC CSCC, there is a need for novel approaches to reduce the high risk of subsequent new primary skin cancer development in this patient subset.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: Preprints.org, Table S1: Patient characteristics and treatment; Table S2: Treatment outcome; Table S3: Cemiplimab + RT.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, T.F. and W.S.; methodology, T.F. and W.S.; validation, T.F.,W.S. and R.M.; formal analysis, T.F. and W.S; investigation, T.F.,W.S. and R.M.; resources, W.S.; data curation, T.F. and W.S.; writing—original draft preparation, T.F.; writing—review and editing, T.F., W.S. and R.M.; visualization, W.S.; supervision, W.S.; project administration, W.S.; funding acquisition, W.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript

Funding

This research was funded in part by US National Institutes of Health (NIH) grant 5U10CA035421. The publication fees for this article were supported by the Kirk Kerkorian School of Medicine @ UNLV Open Article Fund.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This retrospective data analysis project was formally re-viewed by the WCG IRB Chair and deemed exempt from full board review.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

De-identified primary data will be made available upon reasonable request to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our appreciation to patients and their families and the clinical staff of Comprehensive Cancer Centers of Nevada. Critical review of the manuscript by Suzanne Samlowski, M.Arch. is also appreciated.

Conflicts of Interest

W.S. is a member of the Regeneron Speakers bureau. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AJCC |

American Joint Committee on Cancer |

| CLL |

Chronic lymphocytic leukemia |

| CR |

Complete response |

| CSCC |

Cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma |

| CT |

Computerized tomography |

| EGFR |

Epidermal growth factor receptor |

| ICI |

Immune checkpoint inhibitor |

| IRB |

Institutional review board |

| MRI |

Magnetic resonance imaging |

| NHL |

Non-Hodgkins lymphoma |

| PD |

Progressive disease |

| PET |

Positron emission tomography |

| PFS |

Progression-free survival |

| PR |

Partial response |

| RT |

Radiotherapy |

| SD |

Stable disease |

| SEER |

Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results |

| StDev |

Standard deviation |

| TNTC |

Too numerous to count |

| UICC |

Union for international cancer control |

| UPN |

Unique patient number |

References

- Nagarajan, P.; Asgari, M.M.; Green, A.C.; et al. Keratinocyte Carcinomas: Current Concepts and Future Research Priorities. Clin Cancer Res 2019, 25, 2379–2391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Que, S.K.T.; Zwald, F.O.; Schmults, C.D. Cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma: Management of advanced and high-stage tumors. J Am Acad Dermatol 2018, 78, 249–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karia, P.S.; Han, J.; Schmults, C.D. Cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma: estimated incidence of disease, nodal metastasis, and deaths from disease in the United States, 2012. J Am Acad Dermatol 2013, 68, 957–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Korhonen, N.; Ylitalo, L.; Luukkaala, T.; et al. Recurrent and Metastatic Cutaneous Squamous Cell Carcinomas in a Cohort of 774 Patients in Finland. Acta Derm Venereol 2020, 100, adv00121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caudill, J.; Thomas, J.E.; Burkhart, C.G. The risk of metastases from squamous cell carcinoma of the skin. Int J Dermatol 2023, 62, 483–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tokez, S.; Wakkee, M.; Kan, W.; et al. Cumulative incidence and disease-specific survival of metastatic cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma: A nationwide cancer registry study. J Am Acad Dermatol 2022, 86, 331–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunner, M.; Veness, M.J.; Ch'ng, S.; et al. Distant metastases from cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma--analysis of AJCC stage IV. Head Neck 2013, 35, 72–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Que, S.K.T.; Zwald, F.O.; Schmults, C.D. Cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma: Incidence, risk factors, diagnosis, and staging. J Am Acad Dermatol 2018, 78, 237–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmults, C.D.; Karia, P.S.; Carter, J.B.; et al. Factors predictive of recurrence and death from cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma: a 10-year, single-institution cohort study. JAMA Dermatol 2013, 149, 541–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, A.K.; Kelley, B.F.; Prokop, L.J.; et al. Risk Factors for Cutaneous Squamous Cell Carcinoma Recurrence, Metastasis, and Disease-Specific Death: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA Dermatol 2016, 152, 419–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zakhem, G.A.; Pulavarty, A.N.; Carucci, J.; et al. Association of Patient Risk Factors, Tumor Characteristics, and Treatment Modality With Poor Outcomes in Primary Cutaneous Squamous Cell Carcinoma: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA Dermatol 2023, 159, 160–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tam, S.; Yao, C.; Amit, M.; et al. Association of Immunosuppression With Outcomes of Patients With Cutaneous Squamous Cell Carcinoma of the Head and Neck. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2020, 146, 128–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keohane, S.G.; Proby, C.M.; Newlands, C.; et al. The new 8th edition of TNM staging and its implications for skin cancer: a review by the British Association of Dermatologists and the Royal College of Pathologists, U. K. Br J Dermatol 2018, 179, 824–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karia, P.S.; Jambusaria-Pahlajani, A.; Harrington, D.P.; et al. Evaluation of American Joint Committee on Cancer, International Union Against Cancer, and Brigham and Women's Hospital tumor staging for cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma. J Clin Oncol 2014, 32, 327–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inda, J.J.; Kabat, B.F.; Larson, M.C.; et al. Comparison of tumor staging systems for cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia. J Am Acad Dermatol 2019, 80, 639–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Migden, M.R.; Rischin, D.; Schmults, C.D.; et al. PD-1 Blockade with Cemiplimab in Advanced Cutaneous Squamous-Cell Carcinoma. N Engl J Med 2018, 379, 341–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maubec, E.; Boubaya, M.; Petrow, P.; et al. Phase II Study of Pembrolizumab As First-Line, Single-Drug Therapy for Patients With Unresectable Cutaneous Squamous Cell Carcinomas. J Clin Oncol 2020, 38, 3051–3061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Migden, M.R.; Khushalani, N.I.; Chang, A.L.S.; et al. Cemiplimab in locally advanced cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma: results from an open-label, phase 2, single-arm trial. Lancet Oncol 2020, 21, 294–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenhauer, E.A.; Therasse, P.; Bogaerts, J.; et al. New response evaluation criteria in solid tumours: revised RECIST guideline (version 1.1). Eur J Cancer 2009, 45, 228–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, E.L.; Meier, P. Nonparametric Estimation from Incomplete Observations. Journal of the American Statistical Association 1958, 53, 457–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez-Flores, R.; Samlowski, W.; Perez, L. Elective Checkpoint Inhibitor Discontinuation in Metastatic Solid Tumor Patients: A Case Series. Ann Case Rep 2022, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez, J.C.; Otley, C.C.; Okuno, S.H.; et al. Chemotherapy in the management of advanced cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma in organ transplant recipients: theoretical and practical considerations. Dermatol Surg 2004, 30, 679–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maubec, E.; Petrow, P.; Duvillard, P.; Certain, A.; Duval, X.; Kerob, D.; et al. Cetuximab as first-line monotherapy in patients with unresectable squamous cell carcinoma of the skin: Preliminary results of a phase II multicenter study. J Clin Oncol 2008, 26, abstr #9042. [Google Scholar]

- Maubec, E.; Petrow, P.; Scheer-Senyarich, I.; et al. Phase II study of cetuximab as first-line single-drug therapy in patients with unresectable squamous cell carcinoma of the skin. J Clin Oncol 2011, 29, 3419–3426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foote, M.C.; McGrath, M.; Guminski, A.; et al. Phase II study of single-agent panitumumab in patients with incurable cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma. Ann Oncol 2014, 25, 2047–2052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Montaudie, H.; Viotti, J.; Combemale, P.; et al. Cetuximab is efficient and safe in patients with advanced cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma: a retrospective, multicentre study. Oncotarget 2020, 11, 378–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preneau, S.; Rio, E.; Brocard, A.; et al. Efficacy of cetuximab in the treatment of squamous cell carcinoma. J Dermatolog Treat 2014, 25, 424–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, M.; Samlowski, W.; Meoz, R. Effectiveness and toxicity of cetuximab with concurrent RT in locally advanced cutaneous squamous cell skin cancer: a case series. Oncotarget 2023, 14, 709–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winge, M.C.G.; Kellman, L.N.; Guo, K.; et al. Advances in cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma. Nat Rev Cancer 2023, 23, 430–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munhoz, R.R.; Nader-Marta, G.; de Camargo, V.P.; et al. A phase 2 study of first-line nivolumab in patients with locally advanced or metastatic cutaneous squamous-cell carcinoma. Cancer 2022, 128, 4223–4231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, B.G.M.; Guminski, A.; Bowyer, S.; et al. A phase 2 open-label study of cemiplimab in patients with advanced cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma (EMPOWER-CSCC-1): Final long-term analysis of Groups 1, 2, and 3, and primary analysis of fixed-dose treatment Group 6. J Am Acad Dermatol 2024. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuzmanovszki, D.; Kiss, N.; Toth, B.; et al. Real-World Experience with Cemiplimab Treatment for Advanced Cutaneous Squamous Cell Carcinoma-A Retrospective Single-Center Study. J Clin Med 2023, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verkerk, K.; Geurts, B.S.; Zeverijn, L.J.; et al. Cemiplimab in locally advanced or metastatic cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma: prospective real-world data from the DRUG Access Protocol. Lancet Reg Health Eur 2024, 39, 100875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seymour, L.; Bogaerts, J.; Perrone, A.; et al. iRECIST: guidelines for response criteria for use in trials testing immunotherapeutics. Lancet Oncol 2017, 18, e143–e152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallardo, D.; Sparano, F.; Vitale, M.G.; et al. Impact of cemiplimab treatment duration on clinical outcomes in advanced cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma. Cancer Immunol Immunother 2024, 73, 160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.Y.; Johnson, D.B.; Davis, E.J. Toxicities Associated With PD-1/PD-L1 Blockade. Cancer J 2018, 24, 36–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).