1. Introduction

Since 2010, our research team has developed a solution for the digitization, visualization of and interaction with ancient drawings and paintings addressed to various stakeholders engaged in paintings and ancient drawings’ knowledge, preservation, conservation and communication activities: museum visitors, art historians, restorers, professional operators and other figures. While the initial research was focused on the ancient drawings (mainly by Leonardo da Vinci) resulting in the successful application

ISLe - InSight Leonardo [

1], the approach was later extended to manuscripts as well as ancient paintings with the applications

AnnunciatiOn App [

2] and the recent

GigaGuercino App. These outcomes follow a different trajectory from the usual answer given by the scientific community to the related issues, based on 2D outputs following two paths:

Digital representations based on images with very high density of spatial content (i.e., the so-called gigapixel images). This solution is well illustrated by the Rijksmuseum’s 2019 gigantic Operation Night Watch project, which was able to reproduce Rembrandt’s painting with a resolution of 5 µm using 717 billion pixels [

3].

Images from Dome Photography (DP) that can be used in three ways: (1) visualization of the surface behavior of the artwork by interactive movement of a virtual light source over the enclosing hemisphere, i.e. the Reflectance Transformation Images (RTI) [

4]; (2) 3D reconstruction of the object surface; (3) modelling of the specular highlights from the surface and hence realistic rendering.

These representations of paintings or drawings are generally accurate in resolution but limited to the simple reproduction of the apparent color and able to show the artwork just from a single, predefined point of view, missing the three dimensionality and reflectance properties. Paintings and drawings, instead, represent complex artistic creations, whose faithful knowledge though a copy implies the reproduction of the thickness and reflectance of brushstrokes, pens, and pencils (which provide insights into the techniques employed by painters), the subtle nuances of their surfaces, the presence of

craquelures (valuable for determining the preservation state) and the optical properties of the papers and painting materials [

5].

To meet these requirements, the solution developed by our team is 3D-based and rendered in real-time, allowing:

In practice, the artwork is represented as a 3D model in a virtual space, and the optical behavior of its surface are modeled by tracing it back to phenomena belonging to three different scales: the

microscopic scale, which can be summarized for artworks as their color (diffuse albedo), brilliance, and transparency/translucency; the

mesoscale, which describes the roughness of the surface (what can be called 3D texture or topography); and finally the

macroscopic scale, which can be described as the whole shape of the artefact [

8].

Based on this modelling ranking, some software and techniques have been developed to return each scale correctly:

nLights, a software based on

Photometric Stereo (PS) [

9], handles the

mesostructure components; an analytically approximated

Bidirectional Reflectance Distribution Function (BRDF) derived from the Cook-Torrance physical model and implemented via a shader allows to reproduce the

microstructure [

10,

11]; and the SHAFT (

SAT & HUE Adaptive Fine Tuning) program enable a faithful replica of the color [

12]. Finally,

macrostructure has been obtained from time to time using different techniques. In some cases, it was assimilated to a simple plane [

13]; in others, a PS-based solution was used, exploiting computer graphics techniques to correct outliers [

14]; and for the paintings, photogrammetric techniques were used as an efficient solution, as literature confirms [

15].

Recently, we planned to merge all these solutions to have all-inclusive software, allowing a workflow, simple, accessible and economically viable for institutions of varying sizes and resources, accurate and to be used not only by expert researchers, but also by professionals of the Cultural Heritage (CH) sector for mass digitization operations of artworks [

16]. A main goal of the new hardware/software system, with the aim to minimize the complexity of the process and the negatives effects of prolonged exposure of the artwork to the light, is the removal of double data collection techniques to reproduce surfaces and their optical behavior: photogrammetry techniques for the shape, and PS to extract optical reflectance properties [

17]. Despite the well-known limitations of the PS techniques in shape reproduction, we based the whole process on these methods for their superior ability to accurately reproduce surface reflections. Custom-developed software and independently designed and manufactured repro stands [

18] allows accurate results and a quick process from acquisition to visualization (

Figure 1).

This paper delves into the solution developed for 3D reconstruction using PS techniques only, explaining problems and fixes, mainly focusing on the solution of the critical issues in the quantitative determination of surface normals. The assumption that the whole object is lit from the same illumination angle with the same illumination intensity across the entire field of view and the correct localization of the light sources, is a requirement rarely reached for a mismatch between the lighting model and real-world experimental conditions. When the surface normals are integrated, these inconsistencies result in incorrect surface normal estimations, where the shape of a plane becomes a so-called “potato-chip” shape [

19,

20,

21]. In practice, as literature shows [

22], calibrated PS with

n ≥ 3 images is a well posed problem without resorting to integrability, but an error in the evaluation of the intensity of one light source is enough to cause a bias [

23], and outliers may appear in shadow regions, thus providing normal fields that can be highly nonintegrable. To remove dependence on this far light assumption various techniques were developed but, in our opinion, not accurate enough for the art conservation where an accurate quantitative determination of surface’s normals is crucial.

The proposed solution is based on an accurate localization of the lights position through their measurement, and in some other enhancement to delete the residuals outliers. This solution has its rationale in the design of the hardware/software system that allows a single acquisition condition (artifacts larger than the framed field are reproduced by stitching multiple images), and hardware that keeps geometries and dimensions constant. Determining the mutual position of components can be considered a system calibration operation and can be done only once. In the following, the entire PS process is illustrated, as well as the refinements to eliminate noise due to non-Lambertian surfaces, shadows, approximate evaluation of light intensity, and its attenuation. Mainly the measurement process of the two different repro stands designed for capturing drawings and paintings (positioned horizontally and vertically) is presented.

The paper is organized in five main sections. After the

Introduction,

Section 2 begins with a state-of-the-art review of relevant techniques in PS, followed by the description of the PS software developed. Specifications and features of the developed stands conclude the paragraph. In

Section 3 the metrological context is introduced, and it is illustrated the measurement approach for the ‘as built’ stands.

Section 4 presents the results and

Section 5 sums up the key points and findings of the research and examines possible future works.

5. Conclusions

This paper presents a solution for a PS technique able to overcome difficulties in normal integration, i.e. mainly issues in locating light sources, non-Lambertian surfaces, and shadows, to properly reconstruct in 3D the surfaces of artworks such as paintings and ancient drawings.

The solution, based on two key features (i.e., the use of image processing techniques to minimize residuals, and the measurement of the mutual positions of light sources, camera position and acquisition plane), proved to be successful in managing the mentioned criticalities.

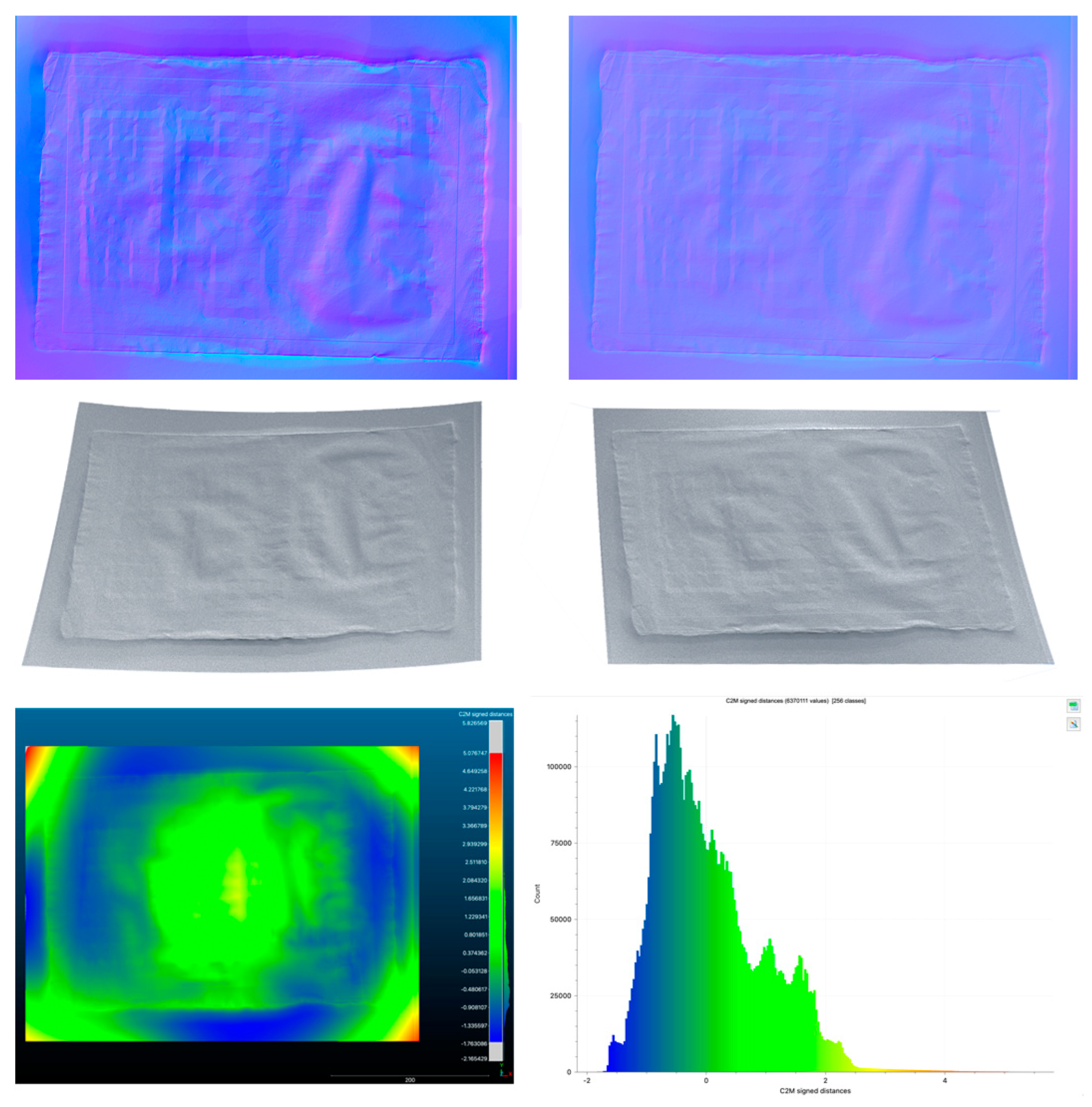

Figure 27.

Results of the developed solution for the drawing of

Figure 1, with and without outliers: normal maps with and without errors (top), meshes with and without outliers (middle), comparison between meshes with and without residuals (bottom).

Figure 27.

Results of the developed solution for the drawing of

Figure 1, with and without outliers: normal maps with and without errors (top), meshes with and without outliers (middle), comparison between meshes with and without residuals (bottom).

In detail, the description of the complete processes of calibration, characterization and measurement of the two stands to find the PoIs, lets us substantiate the procedure and explain its efficiency.

In fact, despite its complexity, since the stands remain unchanged throughout their lifetime and are built with extremely low-deformation materials, once the entire measurement process is completed the end user is exempt from solving its problems by performing complex measurements, which are difficult to understand for most professional users working in the art world, for whom this solution is intended.

Future works may include the simplification of the measurement process to foster higher flexibility, allowing quick but accurate changes of parts in the hardware system (i.e., the lights, the camera and the stand).

Furthermore, more accurate techniques for the elimination of residuals for each specific stand will allow easy use of the whole technical solution for 3D acquisition and visualization of paintings and ancient drawings, which will enable greater involvement of professional operators working in the art reference field.

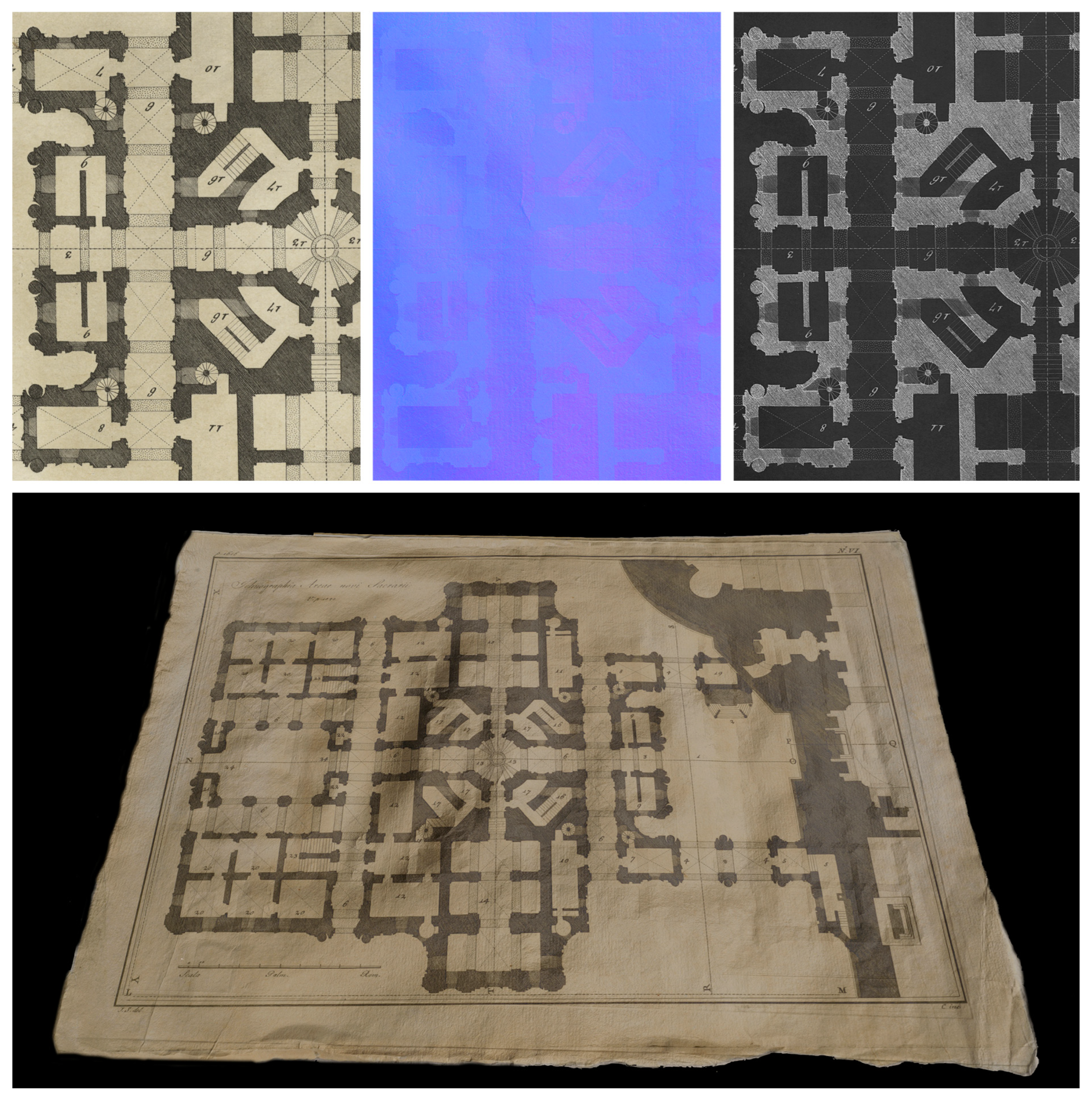

Figure 1.

The maps (albedo, normals, and reflections) reproducing the surface optical reflectance properties of ancient drawings (top) and the resulting real-time rendering visualization (bottom) (St. Peter’s Basilica in Rome plan, ca. 1785, 444 x 294 mm).

Figure 1.

The maps (albedo, normals, and reflections) reproducing the surface optical reflectance properties of ancient drawings (top) and the resulting real-time rendering visualization (bottom) (St. Peter’s Basilica in Rome plan, ca. 1785, 444 x 294 mm).

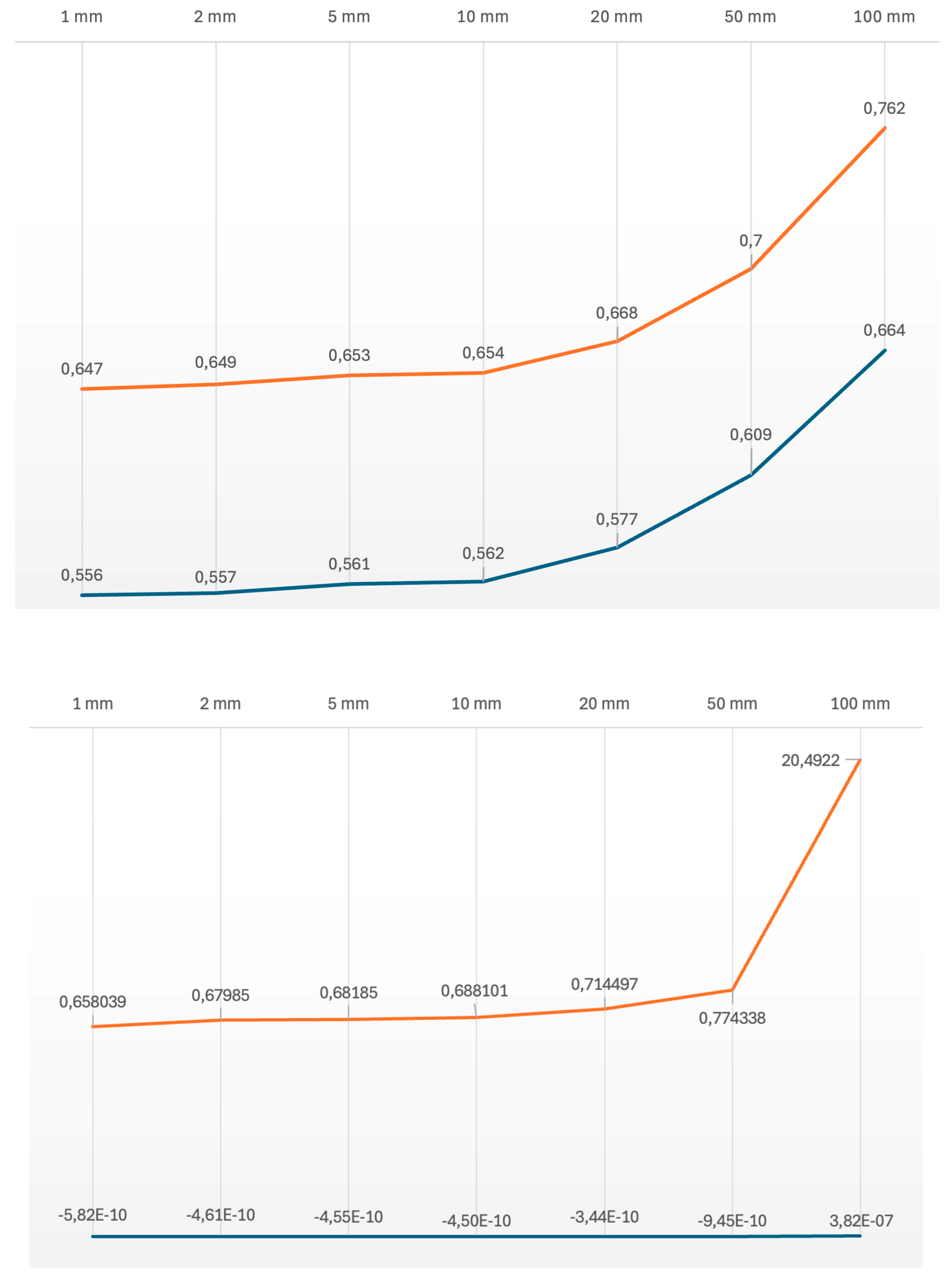

Figure 2.

The mean intensity values (blue) and the standard deviation (red) in the normal map (top) and the mean distances (blue) and the standard deviation (red) of the mesh from a fitting plane (bottom), changing the error in the measurement of the position of the lights along the Z-axis (towards the camera). Both graphs are represented in logarithmic scale.

Figure 2.

The mean intensity values (blue) and the standard deviation (red) in the normal map (top) and the mean distances (blue) and the standard deviation (red) of the mesh from a fitting plane (bottom), changing the error in the measurement of the position of the lights along the Z-axis (towards the camera). Both graphs are represented in logarithmic scale.

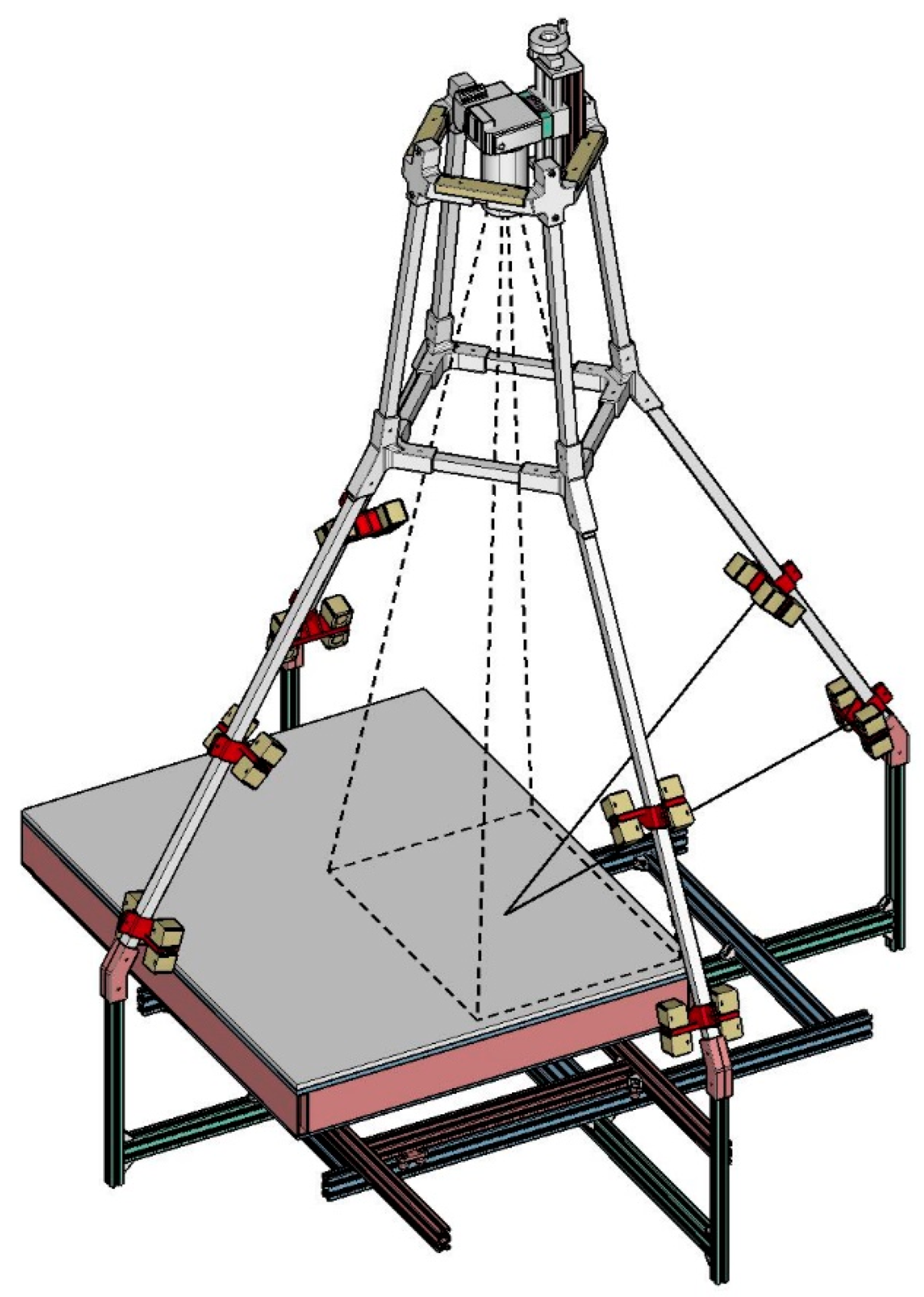

Figure 3.

The horizontal repro stand.

Figure 3.

The horizontal repro stand.

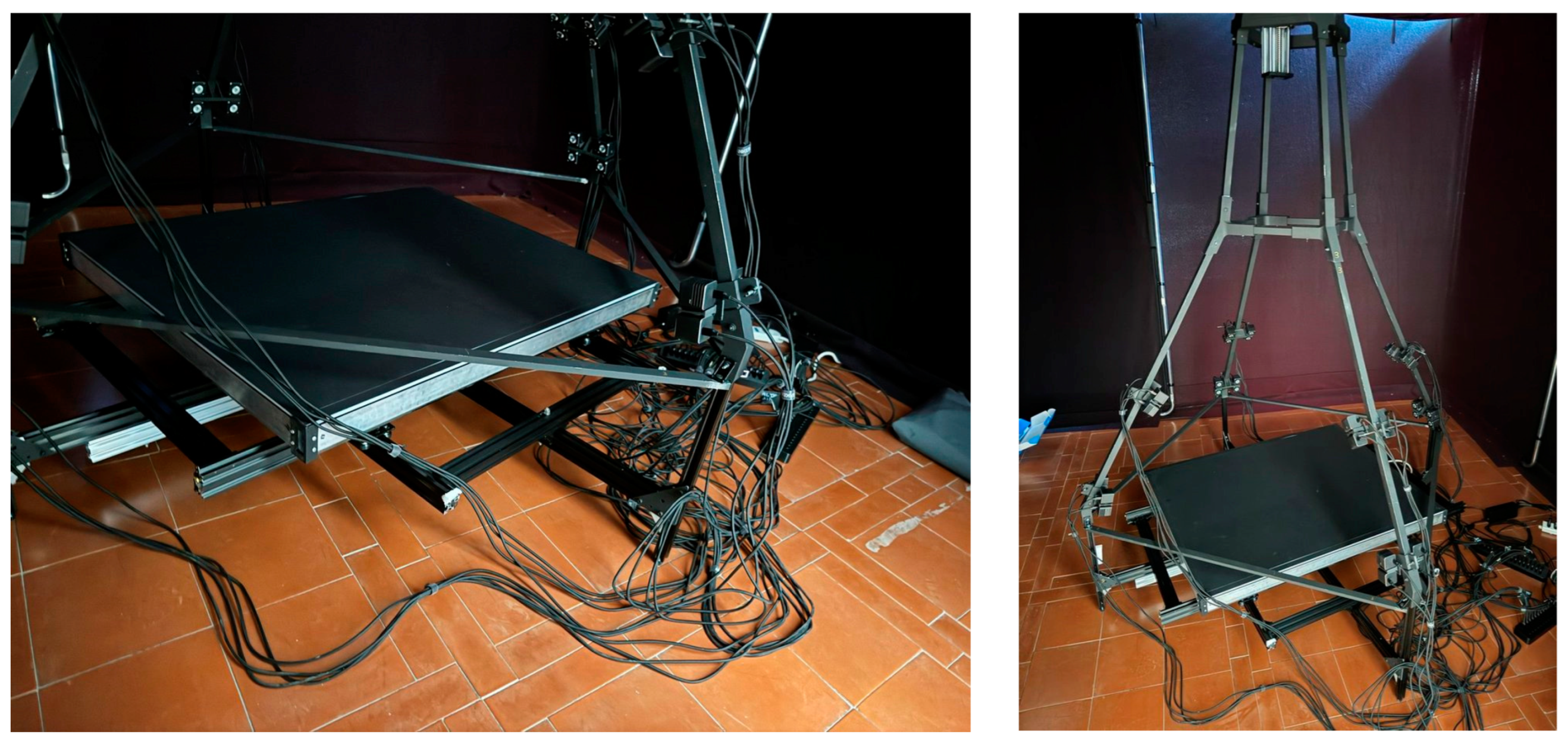

Figure 4.

The elements of the horizontal repro stand: the lower frame (left) and the upper vertical frame (right).

Figure 4.

The elements of the horizontal repro stand: the lower frame (left) and the upper vertical frame (right).

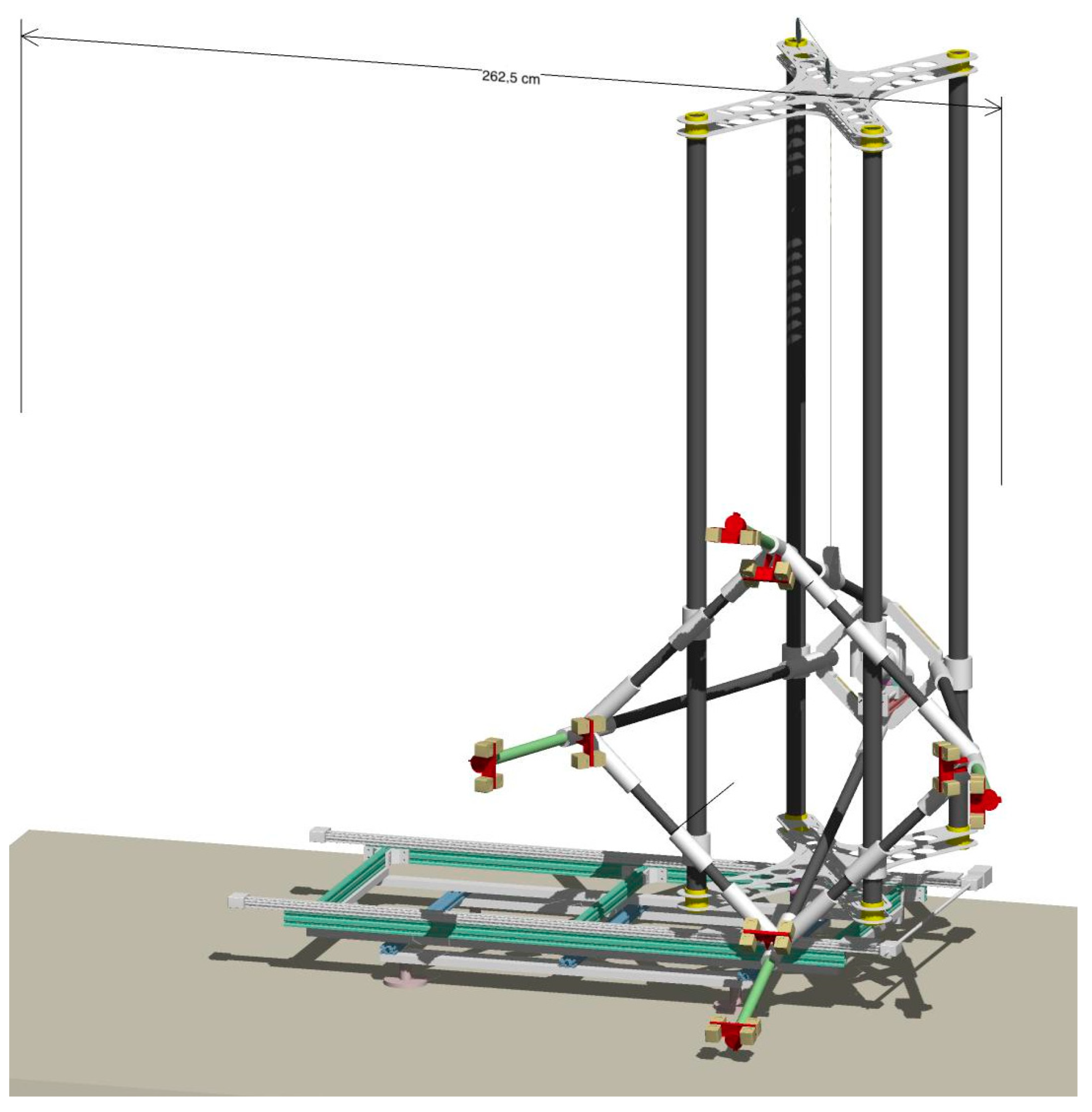

Figure 5.

The robotized vertical repro stand.

Figure 5.

The robotized vertical repro stand.

Figure 6.

The elements of the vertical stand main structure: lower frame (left), vertical frame (middle), trapezoidal frame (right).

Figure 6.

The elements of the vertical stand main structure: lower frame (left), vertical frame (middle), trapezoidal frame (right).

Figure 7.

The darkening occlusion system of the vertical stand.

Figure 7.

The darkening occlusion system of the vertical stand.

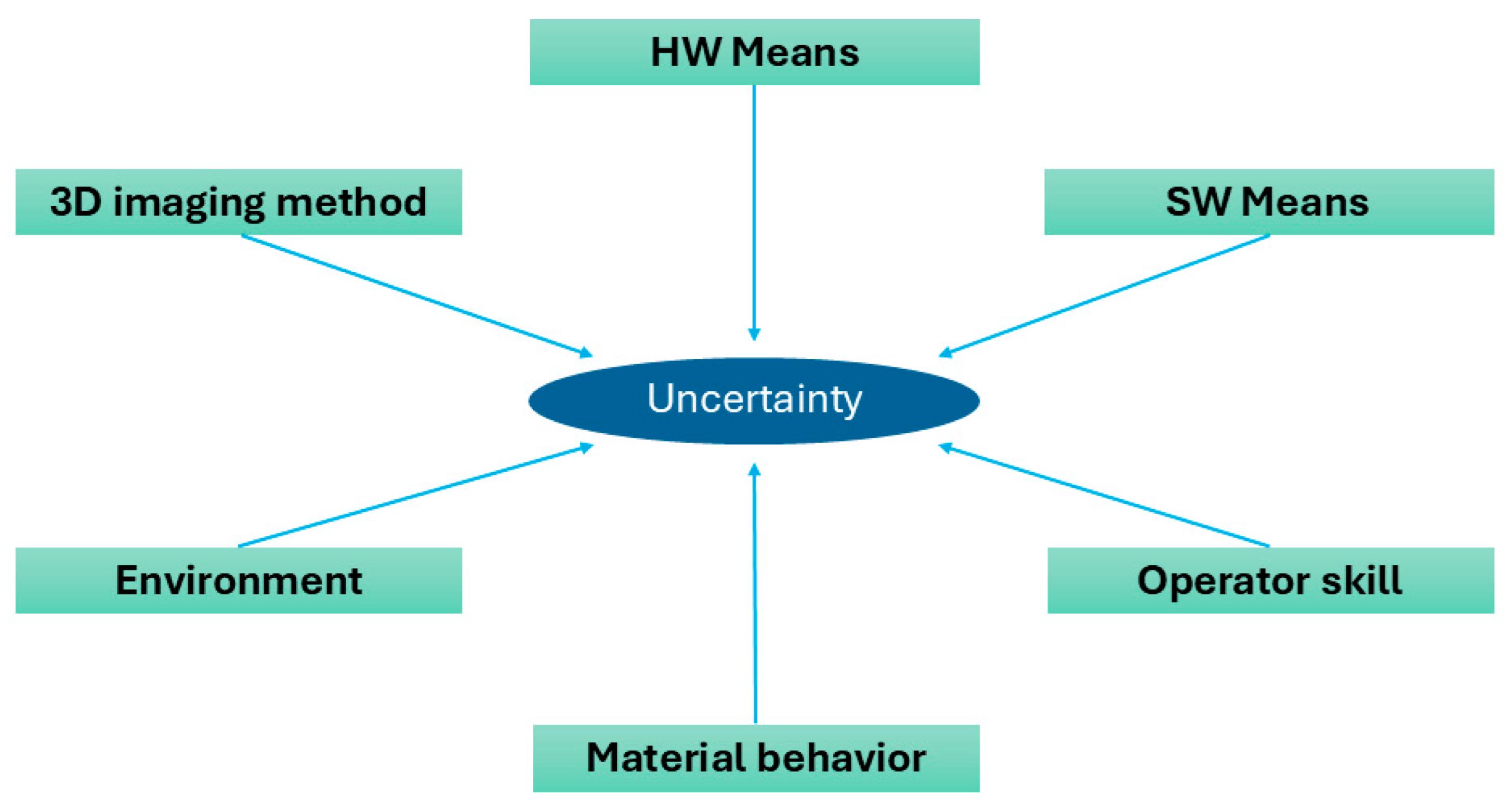

Figure 8.

Origin of typical uncertainties in optical 3D imaging systems.

Figure 8.

Origin of typical uncertainties in optical 3D imaging systems.

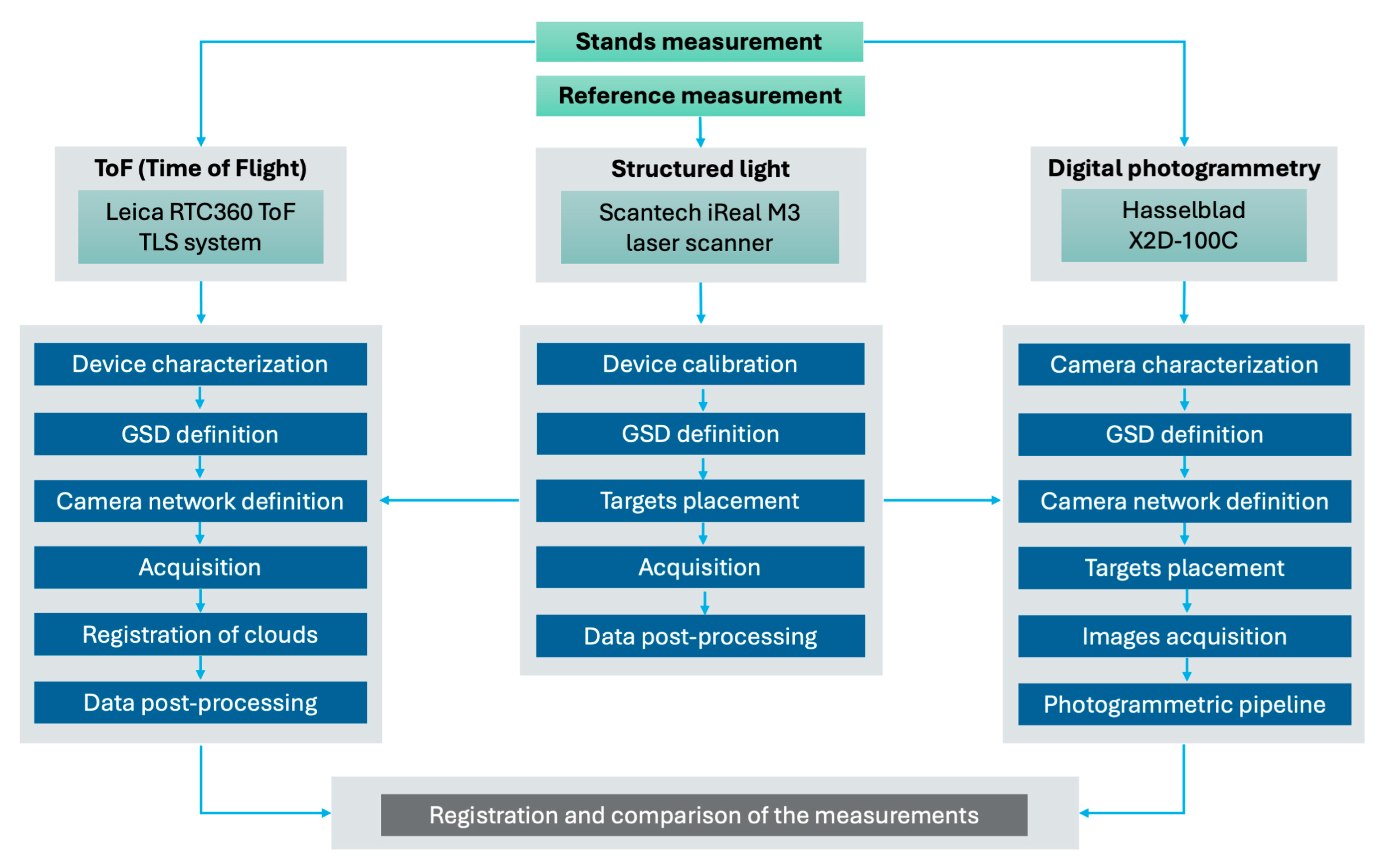

Figure 9.

Workflow of the measurement process.

Figure 9.

Workflow of the measurement process.

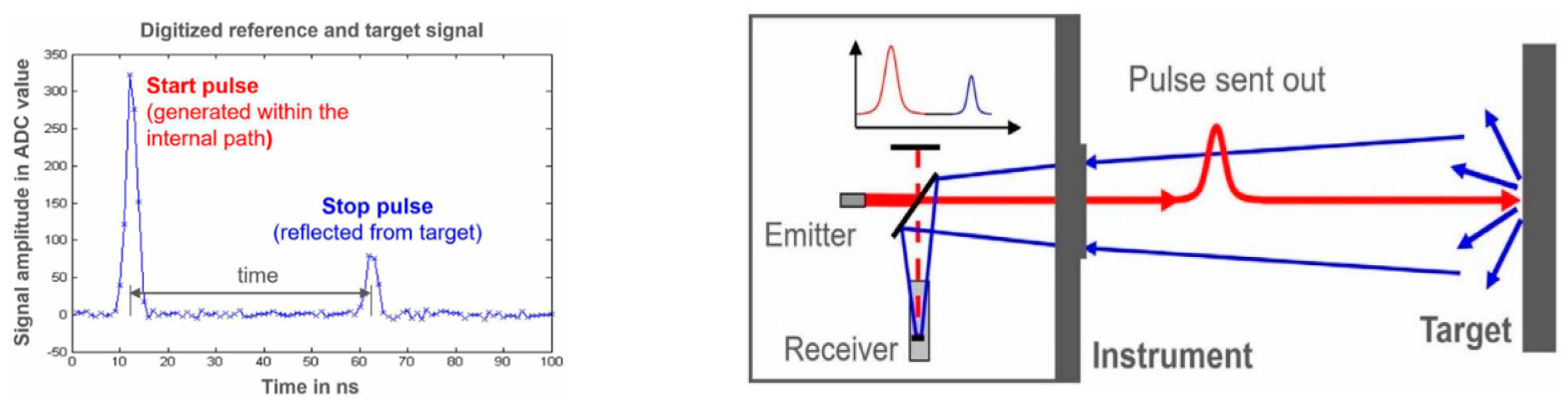

Figure 10.

Schematics for WFD technology [

91].

Figure 10.

Schematics for WFD technology [

91].

Figure 11.

The glass panel used for the laser scanner characterization.

Figure 11.

The glass panel used for the laser scanner characterization.

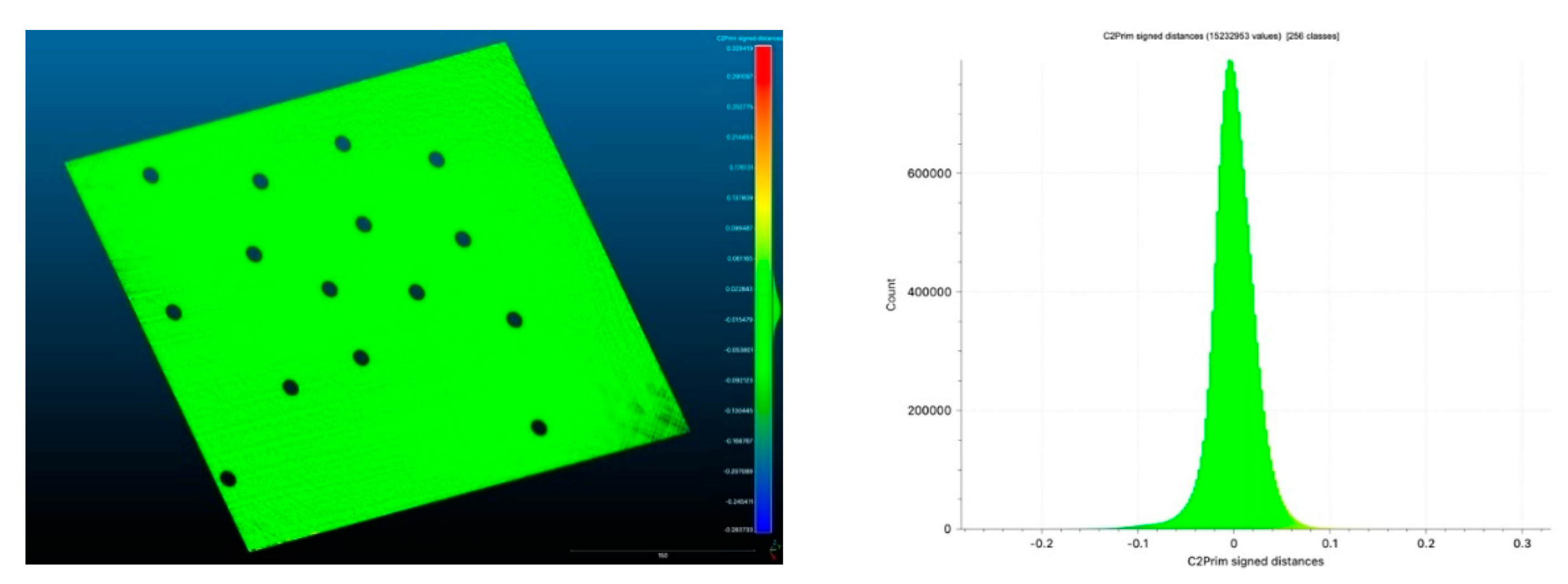

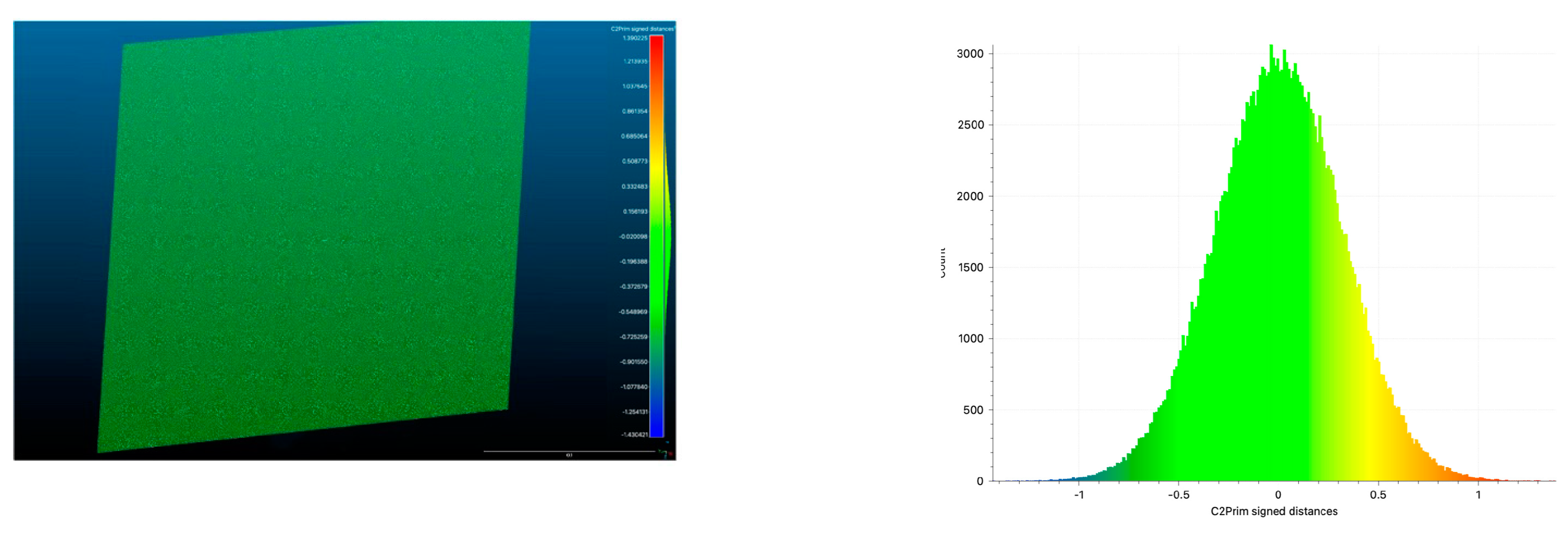

Figure 12.

Point distribution errors of the cloud-to-fitting plane distances of the Scantech iReal M3 (distances are in mm).

Figure 12.

Point distribution errors of the cloud-to-fitting plane distances of the Scantech iReal M3 (distances are in mm).

Figure 13.

Point distribution errors of the cloud-to-fitting plane distances of the Leica RTC360 (distances are in mm).

Figure 13.

Point distribution errors of the cloud-to-fitting plane distances of the Leica RTC360 (distances are in mm).

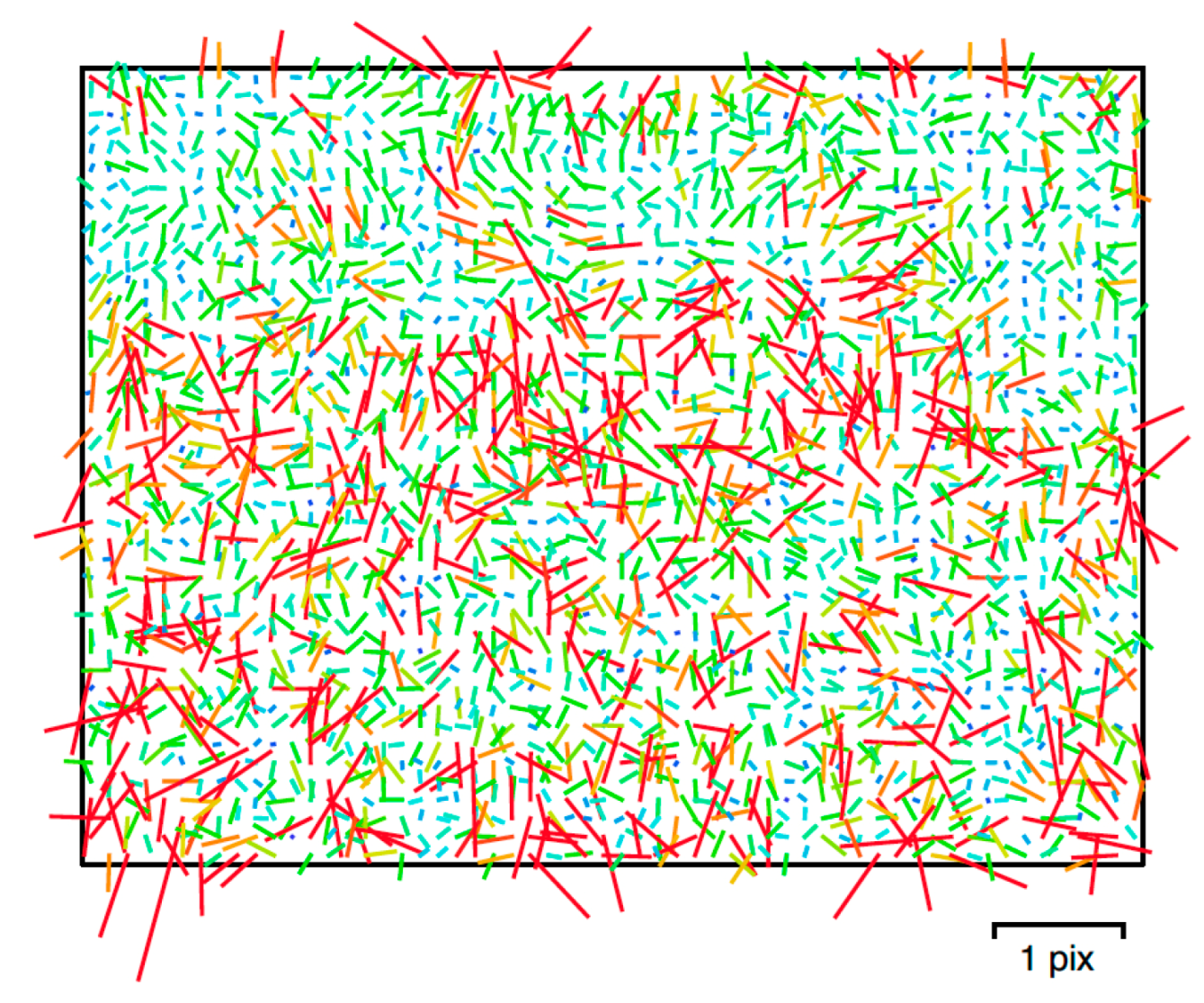

Figure 14.

Image residuals for used Hasselblad X2D-100C camera with XCD 38mm f/2.5 V lens.

Figure 14.

Image residuals for used Hasselblad X2D-100C camera with XCD 38mm f/2.5 V lens.

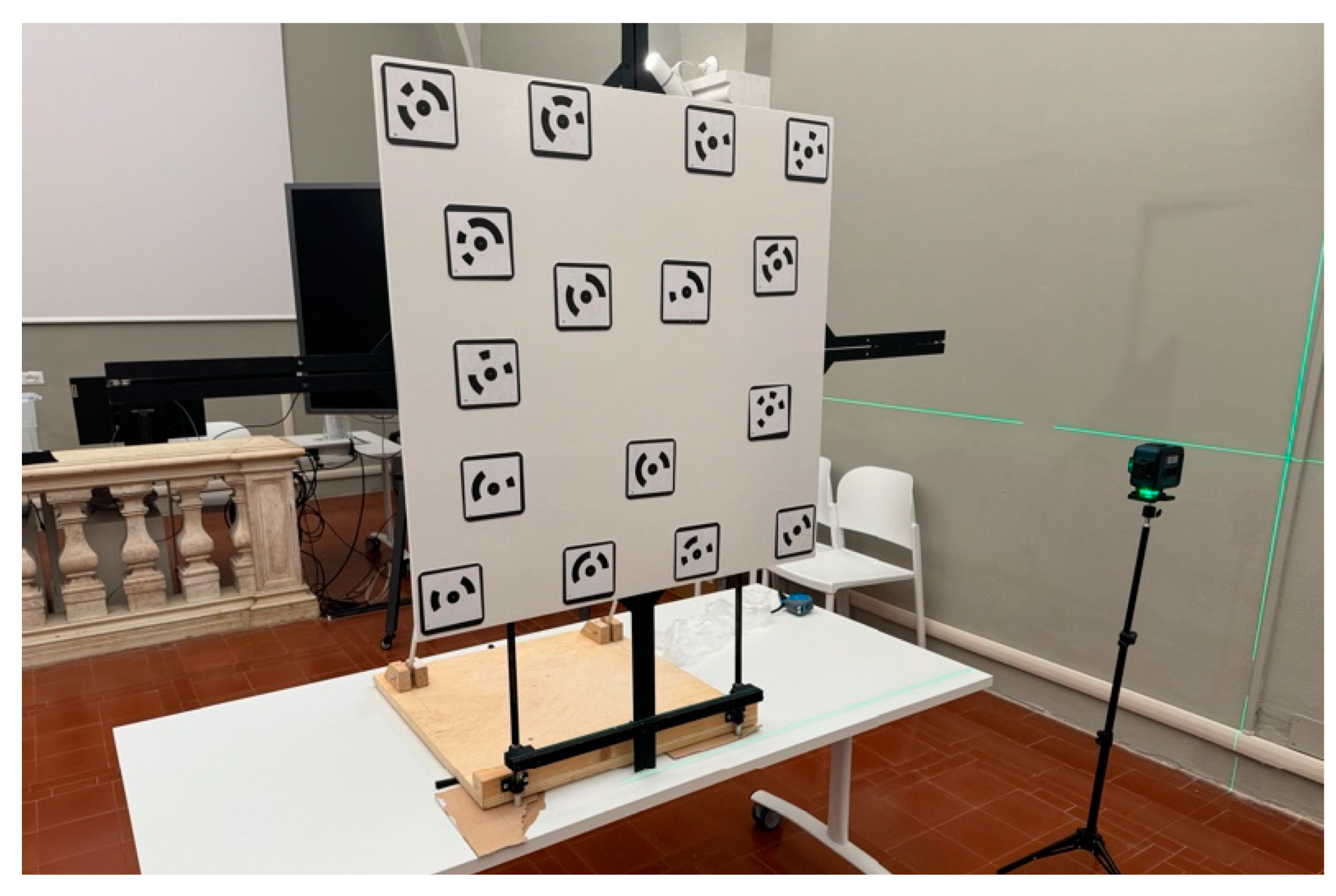

Figure 15.

Vertical plane with the coded RAD targets.

Figure 15.

Vertical plane with the coded RAD targets.

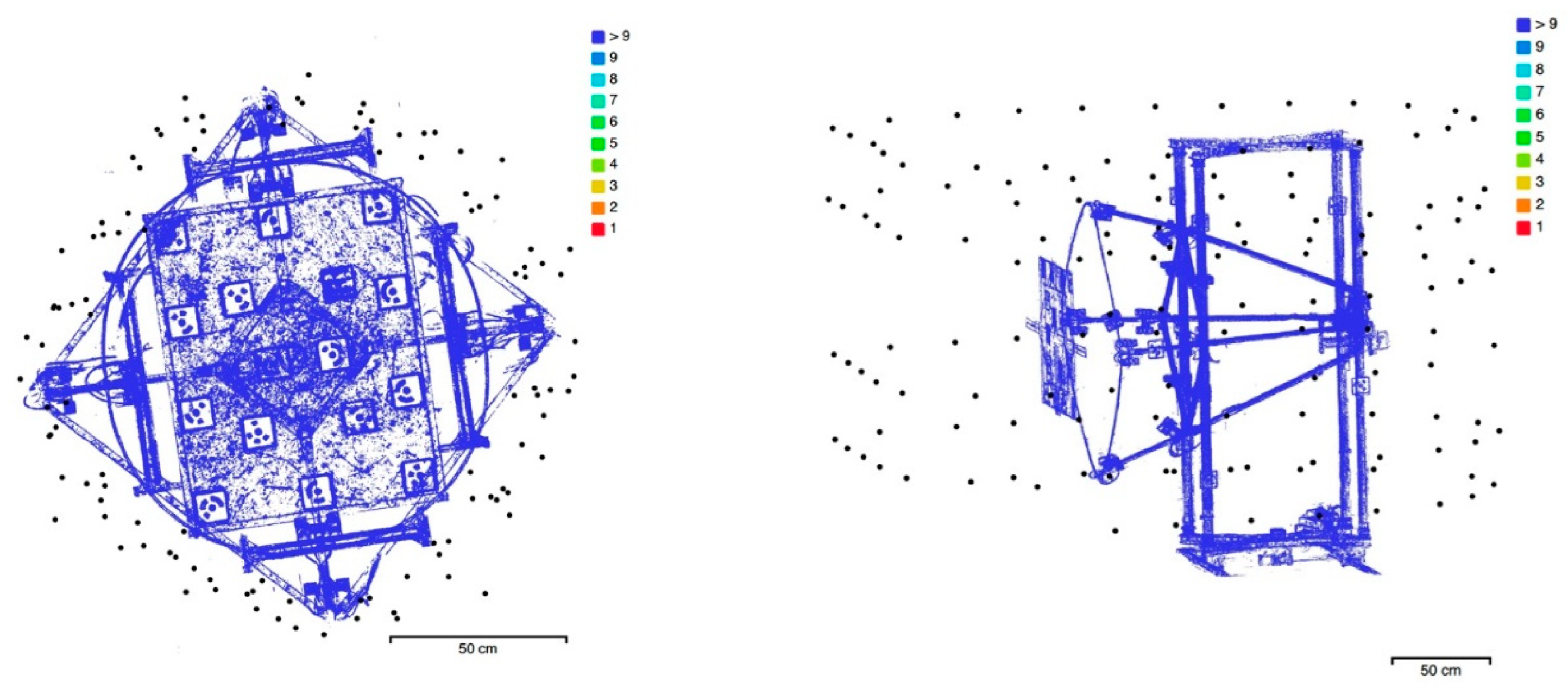

Figure 16.

Radial camera network for the horizontal (left) and vertical (right) repro stands.

Figure 16.

Radial camera network for the horizontal (left) and vertical (right) repro stands.

Figure 17.

Shots coverage for the horizontal (left) and vertical (right) repro stands.

Figure 17.

Shots coverage for the horizontal (left) and vertical (right) repro stands.

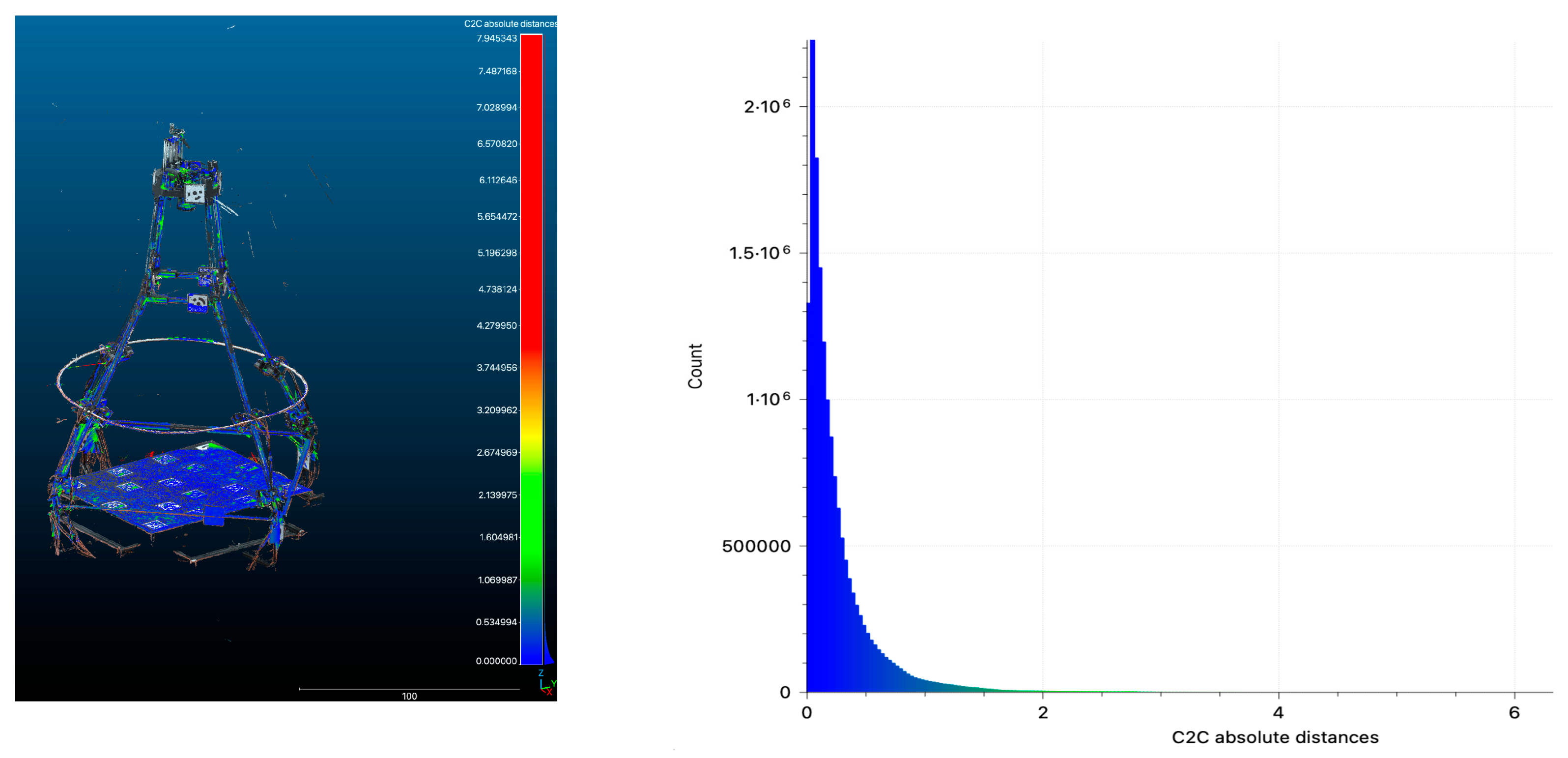

Figure 18.

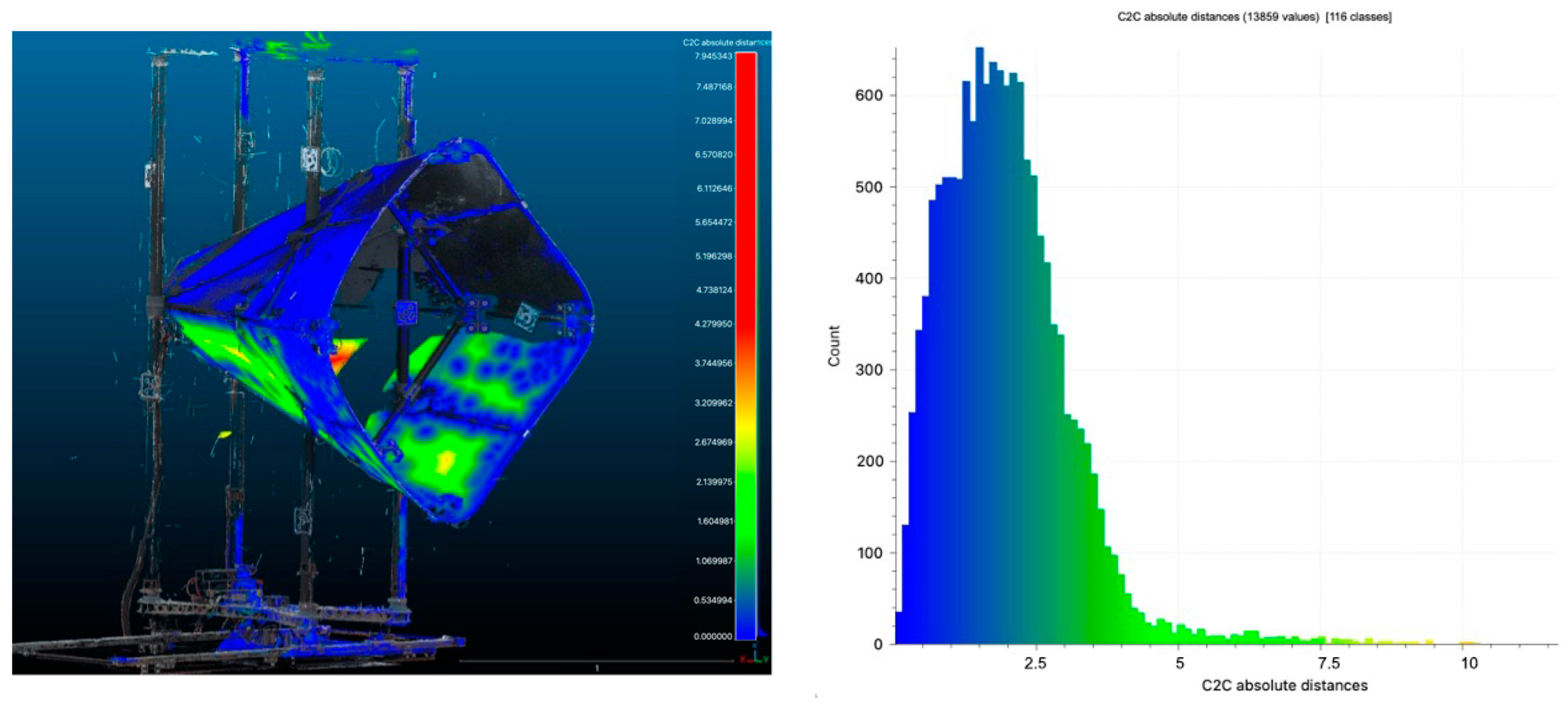

Point distribution errors of the cloud-to-cloud distances between ToF TLS system and photogrammetry (distances are in mm).

Figure 18.

Point distribution errors of the cloud-to-cloud distances between ToF TLS system and photogrammetry (distances are in mm).

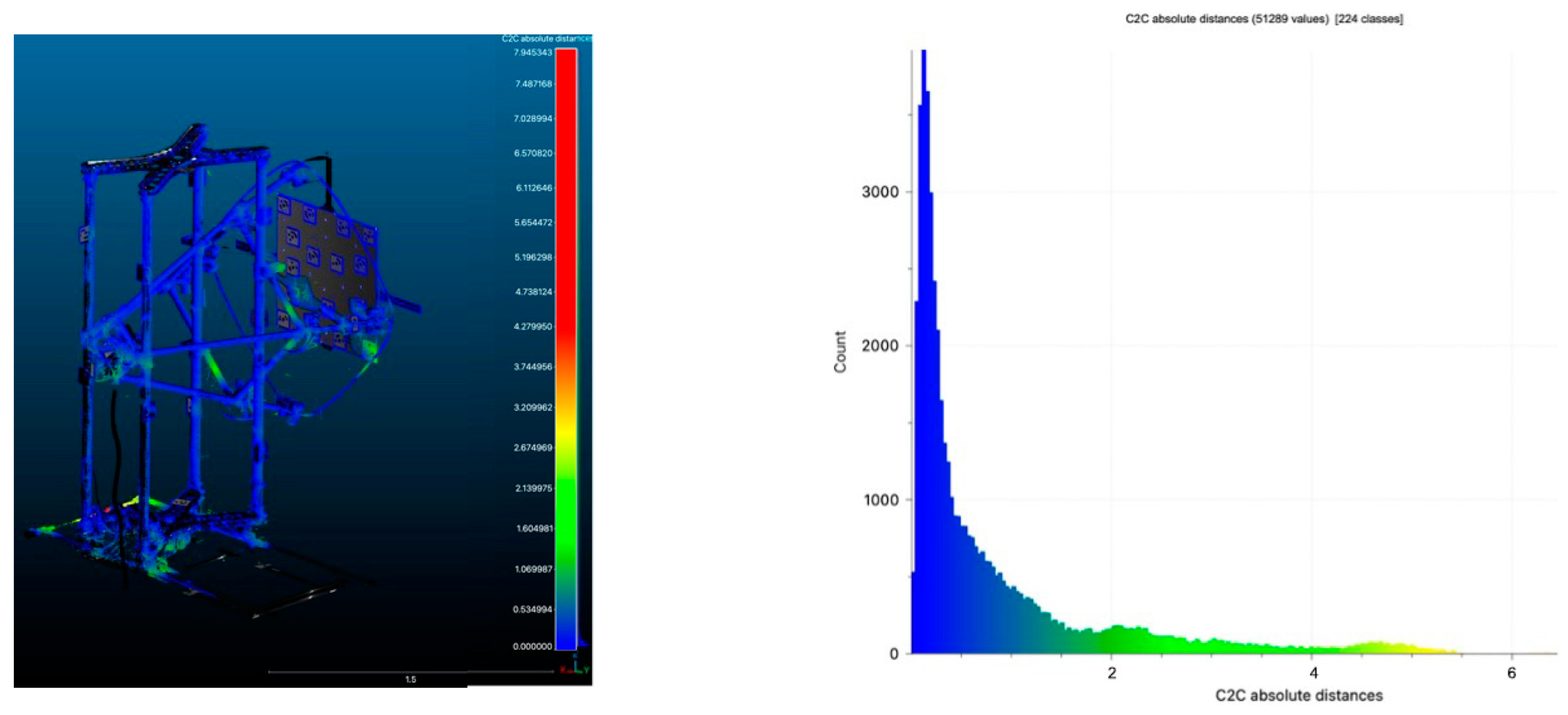

Figure 19.

PoI identification through vector construction on dense cloud points.

Figure 19.

PoI identification through vector construction on dense cloud points.

Figure 20.

Point distribution errors of the cloud-to-cloud distances between the ToF TLS system and photogrammetry (distances are in m).

Figure 20.

Point distribution errors of the cloud-to-cloud distances between the ToF TLS system and photogrammetry (distances are in m).

Figure 21.

Point distribution errors of the cloud-to-cloud distances between ToF TLS system and photogrammetry (distances are in mm).

Figure 21.

Point distribution errors of the cloud-to-cloud distances between ToF TLS system and photogrammetry (distances are in mm).

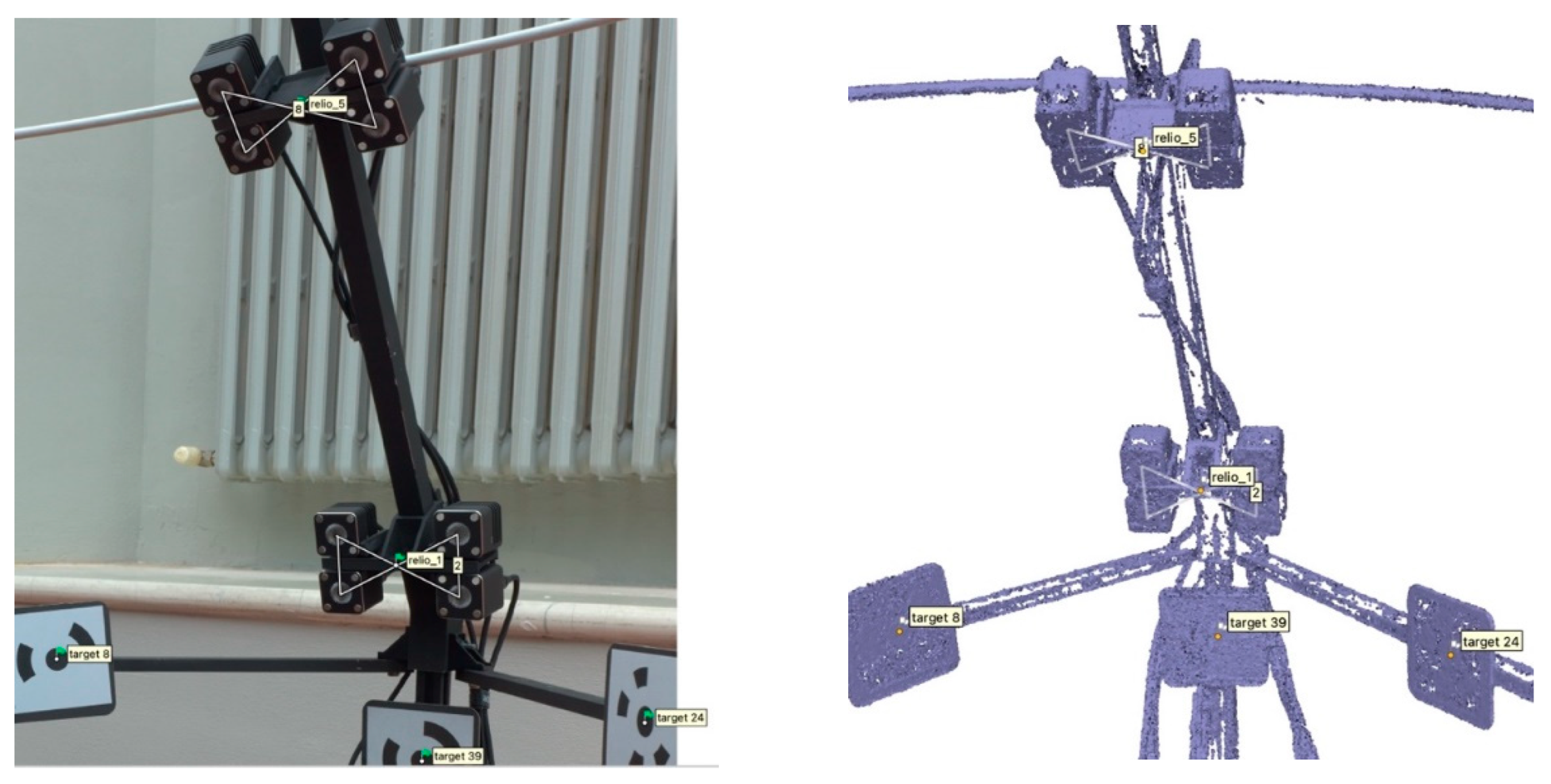

Figure 22.

PoIs identification through vector construction based on dense cloud points.

Figure 22.

PoIs identification through vector construction based on dense cloud points.

Figure 23.

Comparison between a normal map produced with estimated light directions (left) and our measured ones (right). The horizontal repro stand was adopted.

Figure 23.

Comparison between a normal map produced with estimated light directions (left) and our measured ones (right). The horizontal repro stand was adopted.

Figure 24.

Comparison of the 3D meshes improved with measured distances (right) and estimated ones (left); the typical “potato chip” effect is fixed. The vertical repro stand was adopted.

Figure 24.

Comparison of the 3D meshes improved with measured distances (right) and estimated ones (left); the typical “potato chip” effect is fixed. The vertical repro stand was adopted.

Figure 25.

Comparison of the outcomes of the 3D replication of an old engraving as visualized in the

Real-Time Rendering (RTR) engine (Unity, [

107]). Maps and meshes from measured stands improve the appearance of the replica (right) much more than the previous solution (left).

Figure 25.

Comparison of the outcomes of the 3D replication of an old engraving as visualized in the

Real-Time Rendering (RTR) engine (Unity, [

107]). Maps and meshes from measured stands improve the appearance of the replica (right) much more than the previous solution (left).

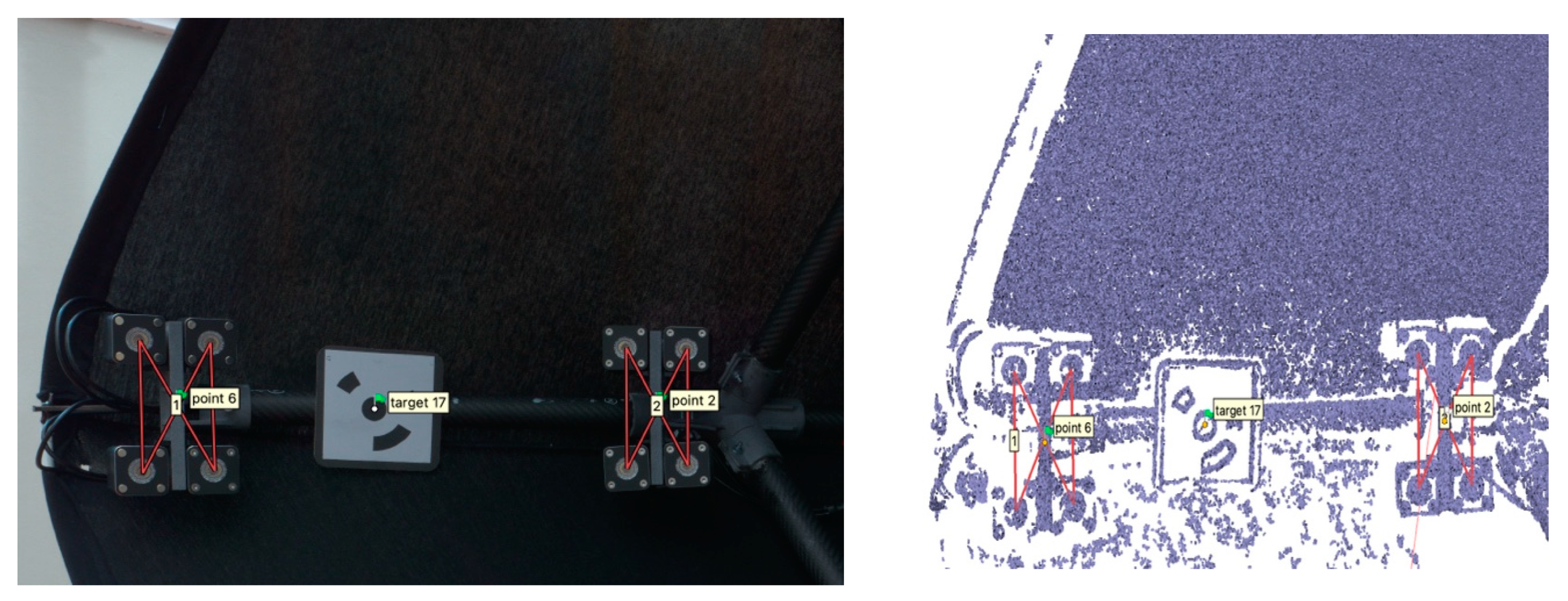

Figure 26.

Comparison of normal maps and 3D meshes of a plane generated for the horizontal stand: without correction (left) and with correction (right). Colors for normal maps are exaggerated for better visibility.

Figure 26.

Comparison of normal maps and 3D meshes of a plane generated for the horizontal stand: without correction (left) and with correction (right). Colors for normal maps are exaggerated for better visibility.

Table 1.

Hasselblad X2D-100C camera.

Table 1.

Hasselblad X2D-100C camera.

| Technology |

Focus |

Resolution |

Sensor size |

ISO Sensibility |

Noise level |

Color depth |

| 100 Megapixel BSI CMOS Sensor |

Phase Detection Autofocus PDAF (97% coverage) |

100 megapixel (pixel pitch 3.78 μm) |

11,656 (W) x 8,742 (H) pixel |

64 - 25600 |

0.4 mm a 10 m |

16 bit |

Table 2.

Hasselblad XCD 3,5/120 Macro lens system.

Table 2.

Hasselblad XCD 3,5/120 Macro lens system.

| Focal length |

Equivalent focal length |

Aperture range |

Angle of view diag/hor/vert |

Minimum distance object to image plane |

| 120.0 mm |

95 mm |

3.5 - 45 |

26°/21°/16° |

430 mm |

Table 3.

Technical specifications of the Scantech iReal M3 laser scanner.

Table 3.

Technical specifications of the Scantech iReal M3 laser scanner.

| Technology |

Framed range |

Accuracy |

Lateral

resolution

|

|

| 7 Parallel infrared laser lines + VCSEL infrared structured light |

580 x 550 mm

(DOF 720 mm with an optimal scanning distance of 400 mm) |

0.1 mm |

0.01 mm |

Table 4.

Technical specifications of Leica RTC360 ToF TLS system.

Table 4.

Technical specifications of Leica RTC360 ToF TLS system.

| Technology |

Framed range |

Accuracy |

Resolution |

Precision |

|

| High dynamic ToF with Wave Form Digitizer Technology (WFD) |

360° (H) – 300° (V) |

1.9 mm at 10 m |

3 mm at 10 m |

0.4 mm at 10 m |

Table 5.

Hasselblad XCD 38mm f/2.5 V lens system.

Table 5.

Hasselblad XCD 38mm f/2.5 V lens system.

| Focal length |

Equivalent focal length |

Aperture range |

Angle of view diag/hor/vert |

Minimum distance object to image plane |

|

| 38.0 mm |

30 mm |

2.5 - 32 |

70°/59°/46° |

300 mm |

Table 6.

Measured precision and accuracy of the Scantech iReal M3.

Table 6.

Measured precision and accuracy of the Scantech iReal M3.

| Captured Area |

295 x 440 mm |

| Sampled points |

6,130,559 |

| Average distance between a fitted plane and point cloud |

0.000441619 mm |

| Standard deviation |

0.0172472 mm |

Table 7.

Measured precision and accuracy of the Leica RTC360.

Table 7.

Measured precision and accuracy of the Leica RTC360.

| Captured Area |

250 x 500 mm |

| Sampled points |

664,675 |

| Average distance between a fitted plane and point cloud |

0.374145 mm |

| Standard deviation |

0.313806 mm |

Table 8.

Calibration coefficients.

Table 8.

Calibration coefficients.

| |

Value |

Error |

f |

Cx |

Cy |

b1 |

b2 |

k1 |

k2 |

k3 |

p1 |

p2 |

| f |

10228.5 |

0.64 |

1.00 |

-0.07 |

0.05 |

-0.90 |

0.04 |

-0.18 |

0.19 |

-0.18 |

-0.11 |

-0.09 |

| Cx |

8.87514 |

0.44 |

- |

1.00 |

-0.07 |

0.10 |

0.14 |

0.01 |

-0.01 |

0.00 |

0.93 |

-0.07 |

| Cy |

-20.5956 |

0.53 |

- |

- |

1.00 |

-0.21 |

0.08 |

0.03 |

-0.03 |

0.03 |

-0.09 |

0.72 |

| b1 |

-10.4546 |

0.59 |

- |

- |

- |

1.00 |

-0.01 |

0.01 |

-0.03 |

0.04 |

0.14 |

0.00 |

| b2 |

-6.16297 |

0.23 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

1.00 |

-0.01 |

0.01 |

-0.00 |

0.05 |

0.04 |

| k1 |

-0.015391 |

0.00023 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

1.00 |

-0.97 |

0.93 |

0.02 |

0.03 |

| k2 |

0.0460376 |

0.0017 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

1.00 |

-0.99 |

-0.02 |

-0.03 |

| k3 |

-0.114143 |

0.0048 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

1.00 |

0.02 |

0.03 |

| p1 |

0.000138551 |

0.000014 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

1.00 |

-0.07 |

| p2 |

0.000219159 |

0.000011 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

1.00 |

Table 9.

Positions of coded targets (origin at the center of the plane, mm).

Table 9.

Positions of coded targets (origin at the center of the plane, mm).

| ID |

X |

Y |

Z |

| 1 |

-112.1833981 |

-265.6449903 |

1.1604001 |

| 2 |

-356.9368841 |

27.3719204 |

1.1928803 |

| 3 |

218.4486223 |

167.6946044 |

0.7668501 |

| 4 |

-83.5303045 |

335.2168791 |

0.8040630 |

| 5 |

-356.2072197 |

-267.7837971 |

1.4174284 |

| 6 |

422.8374003 |

36.3053955 |

0.8180338 |

| 7 |

418.5192553 |

-267.5176537 |

0.7987372 |

| 8 |

172.0460260 |

-268.9918738 |

1.0840074 |

| 9 |

-166.6299110 |

-121.8379844 |

1.2866903 |

| 10 |

20.7659104 |

-72.1971757 |

0.9835656 |

| 11 |

219.4242678 |

-120.2348847 |

0.8334230 |

| 12 |

21.4847097 |

100.0491205 |

0.8094964 |

| 13 |

175.3704988 |

336.8665062 |

0.7985485 |

| 14 |

421.7712423 |

327.9472855 |

1.4888459 |

| 15 |

-357.4699748 |

331.4955047 |

0.9538767 |

| 16 |

-163.2943198 |

169.2829513 |

0.7963140 |

Table 10.

Photogrammetry point cloud outcomes.

Table 10.

Photogrammetry point cloud outcomes.

| |

Agisoft Metashape Professional |

Colmap |

| Number of registered images |

- |

132 |

| Number of tie points |

- |

27,951 |

| Mean observations per image |

- |

859,106 |

| Number of points in the dense cloud |

10,367,336 |

- |

| RMS reprojection error |

- |

0.485 px |

Table 11.

Comparison between ToF TLS and photogrammetry.

Table 11.

Comparison between ToF TLS and photogrammetry.

| Average distance of points |

0.5214 mm |

| Standard deviation |

0.77006 mm |

Table 12.

PoIs extracted and transformed coordinate values (mm).

Table 12.

PoIs extracted and transformed coordinate values (mm).

| PoI |

X |

Y |

Z |

| Origin |

0 |

0 |

0 |

| Relio_1 |

-646.79 |

3.0601 |

171.98 |

| Relio_2 |

-3.6600 |

643.86 |

166.24 |

| Relio_3 |

641.34 |

0.3800 |

163.33 |

| Relio_4 |

-5.1200 |

-645.04 |

165.76 |

| Relio_5 |

-474.21 |

2.6700 |

471.77 |

| Relio_6 |

0.1300 |

476.28 |

459.22 |

| Relio_7 |

466.87 |

0.0700 |

467.11 |

| Relio_8 |

-5.3300 |

-485.74 |

442.38 |

| Camera |

0.0600 |

0.2602 |

1542.48 |

Table 13.

Positions of coded targets (origin at the center of the plane, mm).

Table 13.

Positions of coded targets (origin at the center of the plane, mm).

| ID |

X |

Y |

Z |

| 1 |

-91.7384979 |

-254.3196531 |

0.9266232 |

| 2 |

-318.6724500 |

98.8737499 |

0.9983411 |

| 3 |

161.4589829 |

252.5450786 |

1.0497326 |

| 4 |

319.6547597 |

-319.3383336 |

1.0325548 |

| 5 |

-324.2391213 |

-105.5458775 |

0.8632963 |

| 6 |

102.4372316 |

-79.8087193 |

0.8986234 |

| 7 |

-170.2707334 |

252.3647593 |

1.4474652 |

| 8 |

-319.6547597 |

319.3383336 |

1.3325548 |

| 9 |

95.2218163 |

96.9329011 |

1.1688642 |

| 10 |

146.1604507 |

-261.1907211 |

0.9117996 |

| 11 |

-168.9669076 |

-16.3564388 |

1.2615517 |

| 12 |

322.6046628 |

126.2068312 |

0.9887015 |

| 13 |

-8.7779598 |

248.4658266 |

1.2592235 |

| 14 |

-313.2096315 |

-327.6061740 |

1.1325548 |

| 15 |

319.9531910 |

319.3383336 |

1.1325548 |

| 16 |

317.9581155 |

-126.1577396 |

0.8518509 |

Table 14.

Point cloud outcomes from photogrammetry (with darkening fabric occlusion).

Table 14.

Point cloud outcomes from photogrammetry (with darkening fabric occlusion).

| |

Agisoft Metashape Professional |

Colmap |

| Number of registered images |

|

102 |

| Number of tie points |

|

70.221 |

| Mean observations per image |

- |

1,099.99 |

| Number of points in the dense cloud |

11,373,875 |

- |

| RMS reprojection error |

- |

0.465 px |

Table 15.

Point cloud outcomes from photogrammetry (without darkening fabric occlusion).

Table 15.

Point cloud outcomes from photogrammetry (without darkening fabric occlusion).

| |

Agisoft Metashape Professional |

Colmap |

| Number of registered images |

- |

133 |

| Number of tie points |

118,213 |

- |

| Mean observations per image |

- |

2,990.75 |

| Number of points in the dense cloud |

12,054,708 |

- |

| RMS reprojection error |

- |

0.499 px |

Table 16.

Comparison between ToF TLS and photogrammetry (with darkening fabric occlusion),.

Table 16.

Comparison between ToF TLS and photogrammetry (with darkening fabric occlusion),.

| Average distance of points |

0.5218 mm |

| Standard deviation |

0.79912 mm |

Table 17.

Comparison between ToF TLS and photogrammetry (without darkening fabric occlusion).

Table 17.

Comparison between ToF TLS and photogrammetry (without darkening fabric occlusion).

| Average distance of points |

0.4924 mm |

| Standard deviation |

0.69464 mm |

Table 18.

PoIs extracted and transformed coordinate values (mm - with darkening fabric occlusion).

Table 18.

PoIs extracted and transformed coordinate values (mm - with darkening fabric occlusion).

| PoI |

X |

Y |

Z |

| Origin |

0 |

0 |

0 |

| Relio_1 |

10.7631 |

-225.7121 |

601.7119 |

| Relio_2 |

605.4825 |

-226.7232 |

-4.3642 |

| Relio_3 |

7.4924 |

-239.9226 |

-609.6511 |

| Relio_4 |

-603.3234 |

-230.8313 |

1.2631 |

| Relio_5 |

0.3228 |

-537.4174 |

472.5922 |

| Relio_6 |

461.0301 |

-537.3921 |

8.2132 |

| Relio_7 |

1.5820 |

-541.6323 |

-456.7912 |

| Relio_8 |

-461.62 |

-537.2876 |

8.1521 |

| Camera |

0.0323 |

-1543.8149 |

0.0101 |

Table 19.

PoIs extracted and transformed coordinate values (mm - without darkening fabric occlusion).

Table 19.

PoIs extracted and transformed coordinate values (mm - without darkening fabric occlusion).

| PoI |

X |

Y |

Z |

| Origin |

0 |

0 |

0 |

| Relio_1 |

-1.8714 |

-235.8112 |

611.5131 |

| Relio_2 |

607.6222 |

-225.0312 |

-0.5913 |

| Relio_3 |

11.6712 |

-238.3611 |

-624.8112 |

| Relio_4 |

-589.1021 |

-223.7463 |

-2.9221 |

| Relio_5 |

-2.9265 |

-543.3825 |

469.5811 |

| Relio_6 |

460.6141 |

-538.2921 |

8.1423 |

| Relio_7 |

4.6122 |

-539.5241 |

-463.3921 |

| Relio_8 |

-458.0721 |

-533.0126 |

8.1811 |

| Camera |

0.04 |

-1543.3821 |

0.1712 |

Table 20.

PoI variation (after assembling the darkening fabric occlusion).

Table 20.

PoI variation (after assembling the darkening fabric occlusion).

| PoI |

X |

Y |

Z |

Euclidean distance |

| Origin |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

| Relio_1 |

-12.6345 |

-10.0991 |

9.8012 |

18.9125 |

| Relio_2 |

2.1397 |

1.6920 |

3.7729 |

4.6557 |

| Relio_3 |

4.1788 |

1.5615 |

-15.1601 |

15.8023 |

| Relio_4 |

14.2213 |

7.0850 |

-4.1852 |

16.4304 |

| Relio_5 |

-3.2493 |

-5.9651 |

-3.0111 |

7.4301 |

| Relio_6 |

-0.4160 |

-0.9000 |

-0.0709 |

0.9940 |

| Relio_7 |

3.0302 |

2.1082 |

-6.6009 |

7.5629 |

| Relio_8 |

3.5479 |

4.2750 |

0.0290 |

5.5555 |

| Camera |

0.0077 |

0.4328 |

0.1611 |

0.4618 |