Submitted:

14 March 2025

Posted:

17 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

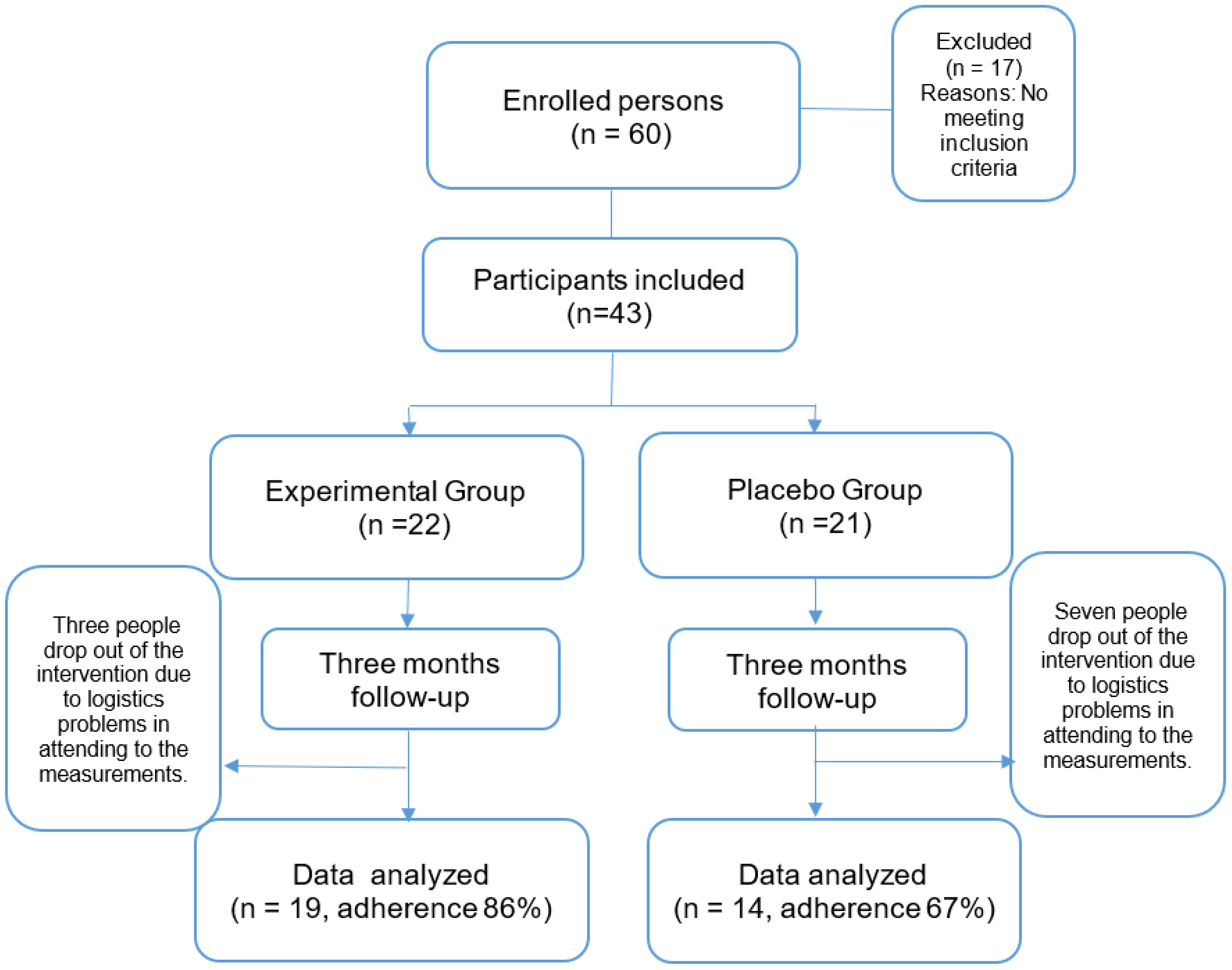

2.1. Experimental Design

2.2. Intervention

2.3. Biochemical Analysis

2.3.1. Samples

2.3.2. Plasma Thiobarbituric Acid Reactive Substances (TBARS)

2.3.3. Proteins Carbonylation

2.3.4. Whole Blood Superoxide Dismutase

2.3.5. Whole blood Glutathione Peroxidase

2.3.6. Catalasa Activity

2.3.7. Plasma Total Antioxidant Status (TAS)

2.3.8. Total oxidant status (TOS)

2.4. Statistical Analysis

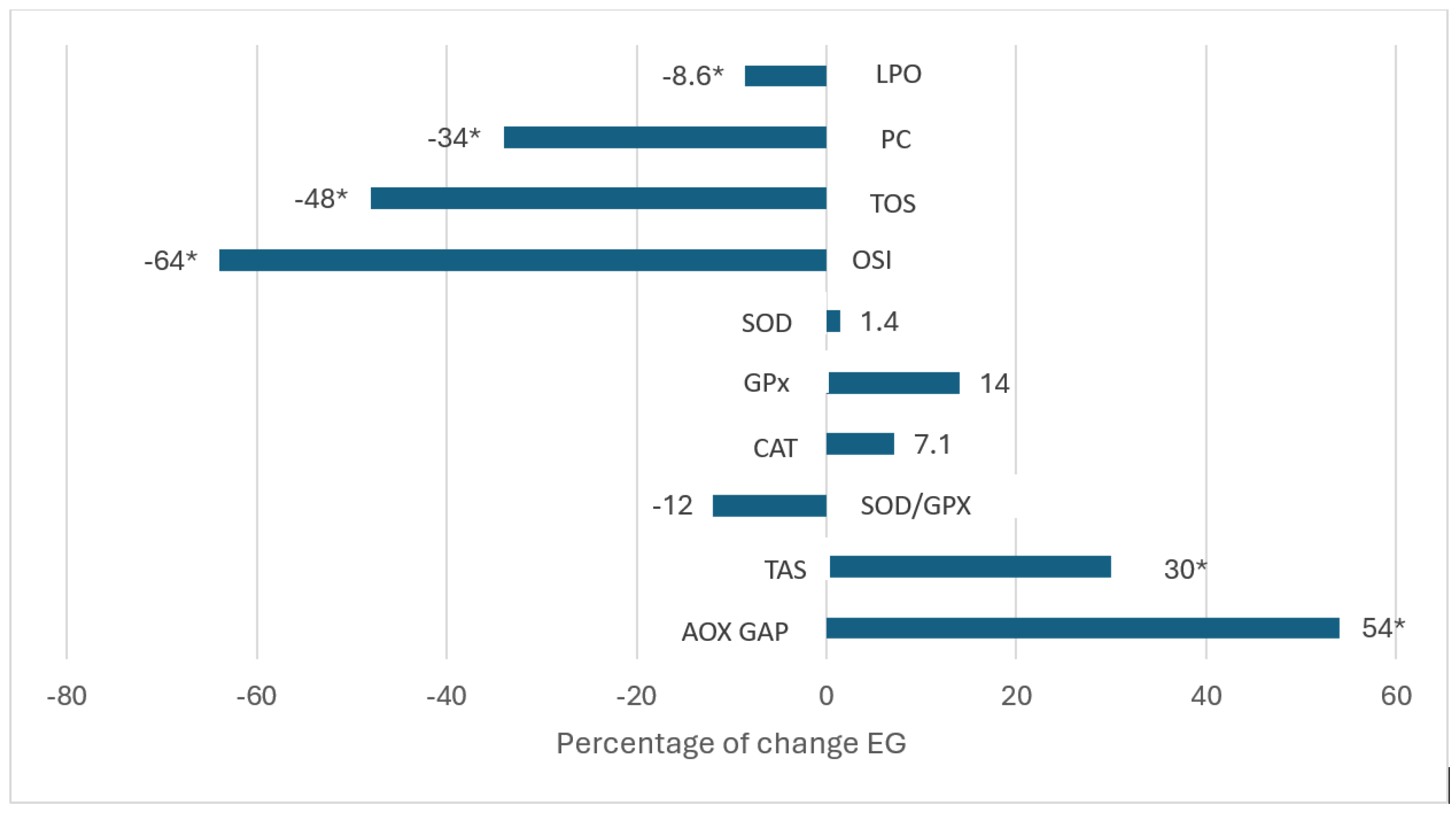

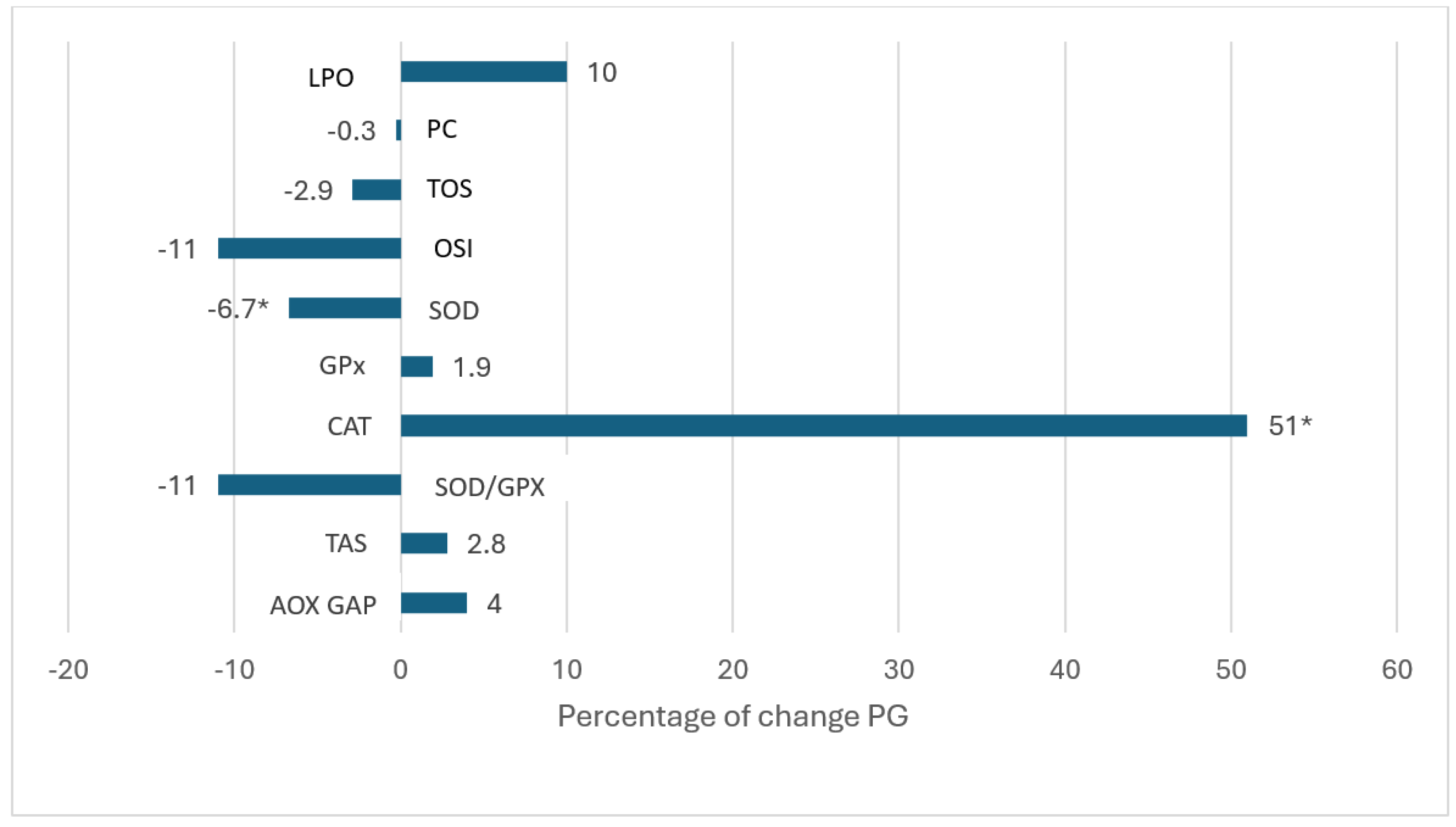

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abel, E.D.; Gloyn AL, Evans-Molina, C.; Joseph, J.J.; Misra, S.; Pajvani, U.V.; Simcox, J.; Susztak, K.; Drucker, D.J. Diabetes mellitus-progress and opportunities in the evolving epidemic. Cell. 2024; 187(15):3789-3820. [CrossRef]

- Surampudi, P.N.; John-Kalarickal, J.; Fonseca, V.A. Emerging concepts in the pathophysiology of type 2 diabetes mellitus. Mt Sinai J Med. 2009; 76(3):216-226. [CrossRef]

- Mahgoub MO, Ali II, Adeghate JO, Tekes K, Kalász H, Adeghate EA. An update on the molecular and cellular basis of pharmacotherapy in type 2 diabetes mellitus. Int J Mol Sci. 2023; 24(11):9328. [CrossRef]

- Mendoza-Núñez, V.M.; Rosado-Pérez, J.; Santiago-Osorio, E.; Ortiz, R.; Sánchez-Rodríguez, M.A.; Galván-Duarte, R.E. Aging linked to type 2 diabetes increases oxidative stress and chronic inflammation. Rejuvenation Res. 2011; 14(1):25-31. [CrossRef]

- GBD 2021 Diabetes Collaborators. Global, regional, and national burden of diabetes from 1990 to 2021, with projections of prevalence to 2050: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2021. Lancet. 2023; 402(10397):203-234. [CrossRef]

- Basto-Abreu, A.; López-Olmedo, N.; Rojas-Martínez, R.; Aguilar-Salinas, C.A.; Moreno-Banda, G.L.; Carnalla, M.; Rivera, J.A.; Romero-Martínez, M.; Barquera, S.; Barrientos-Gutiérrez, T. Prevalencia de prediabetes y diabetes en México: Ensanut 2022. Salud Publica Mex. 2023; 65(supl1):S163-S168. [CrossRef]

- Agbabiaka, T.B.; Wider, B.; Watson, L.K.; Goodman, C. Concurrent use of prescription drugs and herbal medicinal products in older adults: a systematic review. Drugs Aging. 2017; 34(12):891-905.

- Cadena–Iñiguez, J.; Arévalo-Galarza, L.; Avendaño-Arrazate, C.H.; Soto-Hernández, M.; Ruiz-Posadas, L.M.; Santiago-Osorio, E.; Acosta-Ramos, M.; Cisneros-Solano, V.M.; Aguirre-Medina, J.F.; Ochoa-Martínez, D. Production, genetics, postharvest management and pharmacological characteristics of Sechium edule (Jacq.) Sw. Fresh Produce. 2007; 1(1):41–53.

- Aguiñiga-Sánchez, I.; Cadena-Iñiguez, J.; Santiago-Osorio, E.; Gómez-García, G.; Mendoza-Núñez, V.M.; Rosado-Pérez, J.; Ruíz-Ramos, M.; Cisneros-Solano, V.M.; Ledesma-Martínez, E.; Delgado-Bordonave, A.J.; Soto-Hernández, R.M. Chemical analyses and in vitro and in vivo toxicity of fruit methanol extract of Sechium edule var. nigrum spinosum. Pharm Biol. 2017; 55(1):1638-1645.

- Rosado-Pérez, J.; Aguiñiga-Sánchez, I.; Santiago-OsoriO, E.; Mendoza-Núñez, V.M. Effect of Sechium edule var. nigrum spinosum (chayote) on oxidative stress and pro-inflammatory markers in older adults with metabolic syndrome: an exploratory study. Antioxidants (Basel). 2019; 8(5):146.

- Arista-Ugalde, T.L.; Santiago-Osorio, E.; Monroy-García, A.; Rosado-Pérez, J.; Aguiñiga-Sánchez, I.; Cadena-Iñiguez, J.; Gavia-García, G.; Mendoza-Núñez, V.M. Antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effect of the consumption of powdered concentrate of Sechium edule var. nigrum spinosum in Mexican older adults with metabolic syndrome. Antioxidants (Basel). 2022; 11(6):1076. [CrossRef]

- Jentzsch, A.; Bachmann, H.; Fürst, P.; Bielsaski, H.K. Improved analysis of malondialdehyde in human body fluids. Free Radic Biol Med. 1996; 20:251-256.

- Miller, N.J. Nonvitamin plasma antioxidants. In: Amstrong, D. Free radical and antioxidante protocols. New Jersey: Humana Press; 1998. p.285-297.

- Aebi, H. Catalase in vitro. Methods Enzymol. 1984, 105:121–126.

- Lima, J.E.B.F.; Moreira, N.C.S.; Sakamoto-Hojo, E.T. Mechanisms underlying the pathophysiology of type 2 diabetes: From risk factors to oxidative stress, metabolic dysfunction, and hyperglycemia. Mutat Res Genet Toxicol Environ Mutagen. 2022; 874-875:503437. [CrossRef]

- Lotfy, M.; Adeghate, J.; Kalasz, H.; Singh, J.; Adeghate, E. Chronic complications of diabetes mellitus: a mini review. Curr Diabetes Rev. 2017; 13(1):3-10. [CrossRef]

- Gavia-García, G.; Rosado-Pérez, J.; Aguiñiga-Sánchez, I.; Santiago-Osorio, E.; Mendoza-Núñez, V.M. Effect of Sechium edule var. nigrum spinosum (chayote) on telomerase levels and antioxidant capacity in older adults with metabolic syndrome. Antioxidants (Basel). 2020; 18;9(7):634. [CrossRef]

- Gupta, A.; Jamal, A.; Jamil, D.A.; Al-Aubaidy, H.A. A systematic review exploring the mechanisms by which citrus bioflavonoid supplementation benefits blood glucose levels and metabolic complications in type 2 diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Metab Syndr. 2023; 17(11):102884. [CrossRef]

- Naz, R.; Saqib, F.; Awadallah, S.; Wahid, M.; Latif, M.F.; Iqbal, I.; Mubarak, M.S. Food polyphenols and type II diabetes mellitus: pharmacology and mechanisms. Molecules. 2023; 28(10):3996. [CrossRef]

- Vieira, E.F.; Pinho, O.; Ferreira, I.M.P.L.V.O. Chayote (Sechium edule): a review of nutritional composition, bioactivities and potential applications. Food Chem. 2019 Delerue-Matos C. Chayote (Sechium edule): a review of nutritional composition, bioactivities and potential applications. Food Chem. 2019; 1;275:557-568. [CrossRef]

- Rana, A.; Samtiya, M.; Dhewa, T.; Mishra, V.; Aluko, R.E. Health benefits of polyphenols: a concise review. J Food Biochem. 2022; 46(10):e14264. [CrossRef]

- Munir, K.M.; Chandrasekaran, S.; Gao, F.; Quon, M.J. Mechanisms for food polyphenols to ameliorate insulin resistance and endothelial dysfunction: therapeutic implications for diabetes and its cardiovascular complications. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2013; 305(6):E679-E686. [CrossRef]

- Yi, H.; Peng, H.; Wu, X.; Xu, X.; Kuang, T.; Zhang, J.; Du, L.; Fan, G. The therapeutic effects and mechanisms of quercetin on metabolic diseases: pharmacological data and clinical evidence. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2021; 1:6678662. [CrossRef]

- Youl, E.; Bardy, G.; Magous, R.; Cros, G.; Sejalon, F.; Virsolvy, A.; Richard, S.; Quignard, J.F.; Gross, R.; Petit, P.; Bataille, D.; Oiry, C. Quercetin potentiates insulin secretion and protects INS-1 pancreatic β-cells against oxidative damage via the ERK1/2 pathway. Br J Pharmacol. 2010; 161(4):799-814. [CrossRef]

- Bardy, G.; Virsolvy, A.; Quignard, J.F.; Ravier, M.A.; Bertrand, G.; Dalle, S.; Cros, G.; Magous, R.; Richard, S.; Oiry, C. Quercetin induces insulin secretion by direct activation of L-type calcium channels in pancreatic beta cells. Br J Pharmacol. 2013; 169(5):1102-1113. [CrossRef]

- Hii, C.S.; Howell, S.L. Effects of flavonoids on insulin secretion and 45Ca2+ handling in rat islets of Langerhans. J Endocrinol. 1985; 107(1):1-8. PMID: 3900267. [CrossRef]

- Sandep, M.S.; Nandini, C.D. Influence of quercetin, naringenin and berberine on glucose transporters and insulin signalling molecules in brain of streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats. Biomed Pharmacother. 2017; 94:605-611. [CrossRef]

- Eid, H.M.; Nachar, A.; Thong, F.; Sweeney, G.; Haddad, P.S. The molecular basis of the antidiabetic action of quercetin in cultured skeletal muscle cells and hepatocytes. Pharmacogn Mag. 2015; 11(41):74-81. [CrossRef]

- Peng, J.; Li, Q.; Li, K.; Zhu, L.; Lin, X.; Lin, X.; Shen, Q.; Li, G.; Xie, X. Quercetin improves glucose and lipid metabolism of diabetic rats: involvement of Akt signaling and SIRT1. J Diabetes Res. 2017; 2017:3417306. [CrossRef]

- Alam, M.M.; Meerza, D.; Naseem, I. Protective effect of quercetin on hyperglycemia, oxidative stress and DNA damage in alloxan induced type 2 diabetic mice. Life Sci. 2014; 109(1):8-14. [CrossRef]

- Ghorbani, A. Mechanisms of antidiabetic effects of flavonoid rutin. Biomed Pharmacother. 2017; 96:305-312. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Sun, Z.; Dong, R.; Liu, P.; Zhang, X.; Li, Y.; Lai, X.; Cheong, H.F.; Wu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhou, H.; Gui, D.; Xu, Y. Rutin ameliorated lipid metabolism dysfunction of diabetic NAFLD via AMPK/SREBP1 pathway. Phytomedicine. 2024; 126:155437. [CrossRef]

- Niisato, N.; Marunaka, Y. Therapeutic potential of multifunctional myricetin for treatment of type 2 diabetes mellitus. Front Nutr. 2023; 10:1175660. [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zheng, X.; Yi, X.; Liu, C.; Kong, D.; Zhang, J.; Gong, M. Myricetin: a potent approach for the treatment of type 2 diabetes as a natural class B GPCR agonist. FASEB J. 2017; 31(6):2603-2611. [CrossRef]

- Ehrenkranz, J.R.; Lewis, N.G.; Kahn, C.R.; Roth, J. Phlorizin: a review. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2005; 21(1):31-38. [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.H.; Lee, I.S.; Park, J.Y.; Kim, Y.; An, E.J.; Jang, H.J. Cucurbitacin B induces hypoglycemic effect in diabetic mice by regulation of AMP-activated protein kinase alpha and glucagon-like peptide-1 via bitter taste receptor signaling. Front Pharmacol. 2018; 9:1071. [CrossRef]

- Variya, B.C.; Bakrania, A.K.; Patel, S.S. Antidiabetic potential of gallic acid from emblica officinalis: improved glucose transporters and insulin sensitivity through PPAR-γ and Akt signaling. Phytomedicine. 2020; 73:152906. [CrossRef]

- Gandhi, G.R.; Jothi, G.; Antony, P.J.; Balakrishna, K.; Paulraj, M.G.; Ignacimuthu, S.; Stalin, A.; Al-Dhabi, N.A. Gallic acid attenuates high-fat diet fed-streptozotocin-induced insulin resistance via partial agonism of PPARγ in experimental type 2 diabetic rats and enhances glucose uptake through translocation and activation of GLUT4 in PI3K/p-Akt signaling pathway. Eur J Pharmacol. 2014; 745:201-216. [CrossRef]

- Jin, Y.; Arroo, R. The protective effects of flavonoids and carotenoids against diabetic complications- a review of in vivo evidence. Front Nutr. 2023; 10:1020950. [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Pu, Y.; Xu, Y.; He, X.; Cao, J.; Ma, Y.; Jiang, W. Anti-diabetic and anti-obesity: Efficacy evaluation and exploitation of polyphenols in fruits and vegetables. Food Res Int. 2022; 157:111202. [CrossRef]

- Caro-Ordieres, T.; Marín-Royo, G.; Opazo-Ríos, L.; Jiménez-Castilla, L.; Moreno, J.A.; Gómez-Guerrero, C.; Egido, J. The coming age of flavonoids in the treatment of diabetic complications. J Clin Med. 2020; 9(2):346. [CrossRef]

- Kawser, H.M.; Abdal, D.A.; Han, J.; Yin, Y.; Kim, K.; Kumar, S.S.; Yang, G.M.; Choi, H.Y.; Cho, S.G. Molecular mechanisms of the anti-obesity and anti-diabetic properties of flavonoids. Int J Mol Sci. 2016; 17(4):569. [CrossRef]

- Jasmin, J.V. A review on molecular mechanism of flavonoids as antidiabetic agents. Mini Rev Med Chem. 2019; 19(9):762-786. [CrossRef]

- Al-Ishaq, R.K.; Abotaleb, M.; Kubatka, P.; Kajo, K.; Büsselberg, D. Flavonoids and their anti-diabetic effects: cellular mechanisms and effects to improve blood sugar levels. Biomolecules. 2019; 9(9):430. [CrossRef]

- Shen, N.; Wang, T.; Gan, Q.; Liu, S.; Wang, L.; Jin, B. Plant flavonoids: classification, distribution, biosynthesis, and antioxidant activity. Food Chem. 2022; 383:132531. Epub 2022 Feb 23. PMID: 35413752. [CrossRef]

- Chagas, M.D.S.S.; Behrens, M.D.; Moragas-Tellis, C.J.; Penedo, G.X.M.; Silva, A.R.; Gonçalves-de-Albuquerque, C.F. Flavonols and flavones as potential anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, and antibacterial compounds. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2022; 2022:9966750. [CrossRef]

- Pietta, PG. Flavonoids as antioxidants. J Nat Prod. 2000; 63(7):1035-1042. [CrossRef]

- Williams, R,J.; Spencer, J.P.; Rice-Evans, C. Flavonoids: antioxidants or signalling molecules? Free Radic Biol Med. 2004; 36(7):838-849. [CrossRef]

- Rice-Evans, C. Flavonoid antioxidants. Curr Med Chem. 2001; 8(7):797-807. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Wang, J.; Zhao, G.; Lin, M.; Lang, Y.; Zhang, D.; Feng, D.; Tu, C. Apigenin protects human melanocytes against oxidative damage by activation of the Nrf2 pathway. Cell Stress Chaperones. 2020; 25(2):277-285.

- Qiao, Y.Q.; Jiang, P.F.; Gao, Y.Z. Lutein prevents osteoarthritis through Nrf2 activation and downregulation of inflammation. Arch Med Sci. 2018; 14(3):617-624.

- Iskender, H.; Dokumacioglu, E.; Sen, T.M.; Ince, I.; Kanbay, Y.; Saral, S. The effect of hesperidin and quercetin on oxidative stress, NF-κB and SIRT1 levels in a STZ-induced experimental diabetes model. Biomed Pharmacother. 2017; 90:500-508. [CrossRef]

- Gavia-García, G.; Hernández-Álvarez, D.; Arista-Ugalde, T.L.; Aguiñiga-Sánchez, I.; Santiago-Osorio, E.; Mendoza-Núñez V.M.; Rosado-Pérez, J. The supplementation of Sechium edule var. nigrum spinosum (chayote) promotes Nrf2-mediated antioxidant protection in older adults with metabolic syndrome. Nutrients. 2023; 15(19):4106.

- Wahyuningtyas, A.P.; Putri, D.P.; Maharani, N.; Al-Baarri, A.N.M. Flavonoid fraction from chayote (Sechium edule (Jacq.) Sw) leaves reduced malondialdehyde (MDA) and tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) in hyperuricemic rats. Nutr Food Sci. 2022; 52(2):366-378.

- Hecker, M.; Wagner, A.H. Role of protein carbonylation in diabetes. J Inherit Metab Dis. 2018; 41(1):29-38.

- Bollineni, R.C.; Fedorova, M.; Blüher, M.; Hoffmann, R. Carbonylated plasma proteins as potential biomarkers of obesity induced type 2 diabetes mellitus. J Proteome Res. 2014; 13(11):5081-5093.

- Gavia-García, G.; Rosado-Pérez, J.; Arista-Ugalde, T.L.; Aguiñiga-Sánchez, I.; Santiago-Osorio, E.; Mendoza-Núñez, V.M. The consumption of Sechium edule (chayote) has antioxidant effect and prevents telomere attrition in older adults with metabolic syndrome. Redox Rep. 2023; 28(1):2207323. [CrossRef]

- Javadi, B.; Sobhani, Z. Role of apigenin in targeting metabolic syndrome: A systematic review. Iran J Basic Med Sci. 2024; 27(5):524-534.

- Gao, S.; Qin, T.; Liu, Z.; Caceres, M.A.; Ronchi, C.F.; Chen, C.Y.; Yeum, K.J.; Taylor, A.; Blumberg, J.B.; Liu, Y.; Shang, F. Lutein and zeaxanthin supplementation reduces H2O2-induced oxidative damage in human lens epithelial cells. Mol Vis. 2011; 17:3180-90.

- Ordonez, A.A.L.; Gomez, J.D.; Vattuone, M.A. Antioxidant activities of Sechium edule (Jacq.) Swartz extracts. Food Chem. 2006; 97(3):452-458.

- Fidrianny, I.; Ayu, D.; Hartati, R. Antioxidant capacities, phenolic, flavonoid and carotenoid content of various polarities extracts from three organs of Sechium edule (Jacq.) Swartz. J Chem Pharm Res. 2015; 7(5):914-920.

- Loizzo, M.R.; Bonesi, M.; Menichini, F.; Tenuta, M.C.; Leporini, M.; Tundis, R. Antioxidant and carbohydrate-hydrolysing enzymes potential of Sechium edule (Jacq.) Swartz (Cucurbitaceae) peel, leaves and pulp fresh and processed. Plant Foods Hum Nutr. 2016; 71:381–387.

- Shahwan, M.; Alhumaydhi, F.; Ashraf, G.M.; Hasan, P.M.Z.; Shamsi, A. Role of polyphenols in combating Type 2 Diabetes and insulin resistance. Int J Biol Macromol. 2022; 206:567-579. [CrossRef]

- Dragan, S.; Andrica, F.; Serban, M.C.; Timar, R. Polyphenols-rich natural products for treatment of diabetes. Curr Med Chem. 2015; 22(1):14-22. [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Tang, G.; Zhang, C.; Wang, N.; Feng, Y. Gallic acid and diabetes mellitus: its association with oxidative stress. Molecules. 2021; 26(23):7115. [CrossRef]

- Ganguly, R.; Singh, S.V.; Jaiswal, K.; Kumar, R.; Pandey, A.K. Modulatory effect of caffeic acid in alleviating diabetes and associated complications. World J Diabetes. 2023; 14(2):62-75. [CrossRef]

- Naveed, M.; Hejazi, V.; Abbas, M.; Kamboh, A.A.; Khan, G.J.; Shumzaid, M.; Ahmad, F.; Babazadeh, D.; FangFang, X.; Modarresi-Ghazani, F.; Wen, H.L.; Xiao. H. Z. Chlorogenic acid (CGA): A pharmacological review and call for further research. Biomed Pharmacother. 2018; 97:67-74. [CrossRef]

- Thomas, S.D.; Jha, N.K.; Jha, S.K.; Sadek, B.; Ojha, S. Pharmacological and molecular insight on the cardioprotective role of apigenin. Nutrients. 2023; 15(2):385. [CrossRef]

- Shilpa, V.S.; Shams, R.; Dash, K.K.; Pandey, V.K.; Dar, A.H.; Ayaz, M. S.; Harsányi, E.; Kovács, B. Phytochemical properties, extraction, and pharmacological benefits of naringin: a review. Molecules. 2023; 28(15):5623. [CrossRef]

- Dai, S.; Wang, C.; Zhao, X.; Ma, C.; Fu, K.; Liu, Y.; Peng, C.; Li, Y. Cucurbitacin B: A review of its pharmacology, toxicity, and pharmacokinetics. Pharmacol Res. 2023; 187:106587. [CrossRef]

|

Placebo Group (n=14) |

Experimental Group (n=19) |

|

| Glucose (mg/dL) Basal Three-months |

169 ± 79 181 ± 80 |

174 ± 76 160 ± 76 |

| Trigycerides (mg/dL) Basal Three-months |

144 ± 61 184 ± 124 |

148 ± 73 170 ± 94 |

| HDL-C (mg/dL) Basal Three-months |

58 ± 12 60 ± 15 |

55 ± 11 54 ± 14 |

| Urea (mg/dL) Basal Three-months |

39 ± 14 34 ± 15 |

36 ± 18 39 ± 17 |

| Uric acid (mg/dL) Basal Three-months |

3.1 ± 0.9 3.3 ± 1.6 |

3.5 ± 1.4 3.7 ± 1.5 |

| Cholesterol (mg/dL) Basal Three-month |

191 ± 46 210 ± 40 |

186 ± 31 197 ± 52 |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) Basal Three-months |

0.94 ± 0.32 0.90 ± 0.42 |

0.97 ± 0.33 0.90 ± 0.42 |

| Albumin (mg/dL) Basal Three-month |

4.0 ± 0.4 4.2 ± 0.5 |

4.0 ± 0.3 4.1 ± 0.4 |

| HbA1c (%) Basal Three-months |

8.1 ± 2.0 7.8 ± 1.7 |

8.9 ± 2.2 7.8 ± 2.0* |

|

Placebo Group (n=14) |

Experimental Group (n=19) |

|

|

Lipoperoxides (µmol/L) Basal Three-months |

0.338 ± 0.138 0.373 ± 0.145 |

0.243 ± 0.067 0.222 ± 0.050* |

|

Protein carbonylation Basal Three-months |

29.5 ± 10 29.4± 15 |

29.4 ± 10 19.2 ± 6* |

|

TOS Basal Three-months |

5.3 ± 2 5.4± 3 |

6.0 ± 2.6 3.1 ± 1.8* |

|

OSI Basal Three-months |

6.2 ±3 5.5± 4 |

5.7 ±3.1 2.0 ± 1.1* |

|

SOD (U/L) Basal Three-months |

179 ± 8.6 167 ± 12.9 |

177± 12.8 179 ± 16.8* |

|

GPx (U/L) Basal Three-months |

7327 ± 2234 7473 ± 2192 |

5970 ± 2234 6802 ± 1942 |

|

Catalase activity (U/ml) Basal Three-months |

190 ± 70 280 ± 150 |

280± 150 300 ± 130 |

|

SOD/GPx Basal Three-months |

0.027 ± 0.008 0.024 ± 0.008 |

0.033 ± 0.01 0.029± 0.10 |

|

TAS (mmol/L) Basal Three-months |

1.06 ± 0.28 1.09 ± 0.20 |

0.94 ± 0.29 1.22 ± 0.28 * |

|

AOX GAP (µmol/L) Basal Three-months |

473 ± 270 473 ± 208 |

358 ± 283 551 ± 193 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).